Hostile environments, terminal habitat, and tomb trees: the impact of systemic failures to survey for mature-forest dependent species in the State forests of New South Wales

Grant W. Wardell-Johnson A * and Todd P. Robinson

A * and Todd P. Robinson  B

B

A

B

Abstract

The Coastal Integrated Forestry Approval (CIFOA) areas of New South Wales (NSW), Australia include most populations of at least two threatened species of glider Petaurus australis australis (Yellow-bellied Glider [south-eastern]) and Petauroides volans (Greater Glider [Southern and Central]). The NSW Environmental Protection Authority (EPA) administers protocols to conserve gliders within forest compartments intensively managed for timber production by Forests Corporation NSW (FCNSW). These protocols include pre-logging surveys and retention of hollow-bearing trees (HBTs), den trees, and associated buffers. Citizen scientists have ground-truthed these protocols in some compartments.

We assessed the effectiveness of surveys by FCNSW and associated outcomes in the context of planned logging operations.

We used the publicly available EPA Native Forestry map viewer data for this analysis.

Although gliders have been detected and abundant HBTs retained in 10 State forests, no den trees were identified by FCNSW in any ‘active’ compartment (as at December 2023). Thus, isolated HBTs or tomb trees were retained without associated buffers. Several phases of EPA protocols have not improved the outcomes for glider conservation within logged compartments, even when complied with by FCNSW.

Based on the FCNSW data and on citizen science, surveys implemented by FCNSW under CIFOA protocols result in poor outcomes for gliders and other mature forest dependent species. Wholesale changes in process are likely required for effective conservation.

New approaches in monitoring and research commitment, administration, and oversight are likely required to halt the increasingly rapid decline of threatened gliders, as well as local forest communities in the State forests of NSW.

Keywords: Coastal Integrated Forestry Approval, den trees, hollow-bearing trees, industrial-scale logging, mature-forest dependent species, pre-logging surveys, reliability, validity.

Introduction

Despite the global importance of the sclerophyll forests of Australia (Lindenmayer and Franklin 2002; Tozer et al. 2017; Wardell-Johnson et al. 2017; Lindenmayer 2024), exploitation increased in intensity (i.e. whereby intensive logging is from less than 60% basal area retention to clearfelling within operational areas; see Environment East Gippsland Inc v VicForest (No 4) 2022 VSC668; Wardell-Johnson and Robinson 2023; Wardell-Johnson et al. 2024), and extent (i.e. over a wide area) in the decades following the commencement of woodchipping in Australia in 1968 (see Routley and Routley 1974; Resource Assessment Commission 1991; Dargavel 1995; Lindenmayer et al. 2022a). As a result, those forests available for logging have now been altered in structure, composition, and function by the large scale (i.e. industrial scale) of this logging activity (Resource Assessment Commission 1991; Dargavel 1995; Wardell-Johnson et al. 2019, 2024; Wardell-Johnson and Robinson 2023). Notwithstanding cessation of logging in these forests in Victoria and Western Australia (though see Wardell-Johnson et al. 2024), much of the remainder of available mature eucalypt forest is foreshadowed to be logged by 2030 (e.g. Forestry Corporation NSW 2005–2019).

Mature-forest dependent species (MFDS) are among the taxa most threatened by industrial-scale logging recurring within the immature phase of stand development (see Kavanagh et al. 2004; Wardell-Johnson and Robinson 2023; Lindenmayer 2024). These include several species of marsupial glider listed as Threatened Fauna under the Federal Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act (1999) (EPBC Act). Thus, most of the populations in the State of at least two species of threatened glider (Petauroides volans [Family Pseudocheiridae] – Greater Glider [Southern and Central] GGSC); and Petaurus australis australis [Family Petauridae] – Yellow-bellied Glider [south-eastern], YBGSE) occur within the forested east of New South Wales (NSW). The GGSC (Box 1) is listed as Endangered (effective from 5 July 2022) due to a high rate of population decline (>50% over 21 years) and habitat destruction (DCCEEW 2022), while the YBGSE (Box 2) is listed as Vulnerable (effective from 2 March 2022) based on population reduction, habitat destruction and continuing population decline (Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment 2022). The synergistic effects of frequent and intense bushfires, inappropriate prescribed burning, climate change, land clearing, fragmentation, and logging are implicated in the status of these two gliders as Threatened Fauna (McLean et al. 2018; Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment 2022; DCCEEW 2022).

| Box 1.Summary ecology and behaviour of the Greater Glider [Southern and Central] (GGSC), Petauroides volans, Family Pseudocheiridae. |

| The GGSC is the largest Australian gliding mammal and is a nocturnal and solitary herbivore subsisting almost entirely on young eucalypt leaves and flower buds (Kavanagh and Lambert 1990; Comport et al. 1996). They live for up to 15 years (Jones et al. 2009) and den in hollowed trees, each animal inhabiting up to 20 dens (Lindenmayer et al. 1990, 2004; Smith et al. 2007) within its home range of about 1.3–4 ha (Henry 1984; Kavanagh and Wheeler 2004). Their movements are primarily restricted to gliding between tree canopies. Males have larger home ranges than females in the same region (Kavanagh and Wheeler 2004), and male home ranges tend not to overlap (Henry 1984; Kavanagh and Wheeler 2004). |

| The GGSC ranges from the montane to lowland forests (elevation range 0–1200 m) from the Victorian Central Highlands to the Burdekin Gap in Queensland. However, the two taxa currently recognised within this species have a point of contact in the vicinity of Coffs Harbour, New South Wales. They are typically found in highest abundance in taller, montane, moist eucalypt forests on fertile soils, with relatively old trees and abundant hollows (Lindenmayer et al. 1990; Andrews et al. 1994; Smith et al. 1994; Kavanagh 2000; van der Ree et al. 2004). |

| Box 2.Summary ecology and behaviour of the Yellow-bellied Glider [south-eastern] (YBGSE), Petaurus australis australis, Family Petauridae. |

| The arboreal and nocturnal YBGSE is the largest of Petaurid gliders and the second largest of all gliding marsupials, display complex social behaviour, and are highly vocal (Kavanagh and Rohan-Jones 1982; Goldingay 1994; Goldingay et al. 2016). They live and move in family groups of two to six individuals, with each group using several large tree hollows (dens) within an exclusive home range of 50–65 ha (Goldingay 1992; Goldingay and Kavanagh 1993). Their large home ranges encompass dispersed and seasonally variable food resources (Goldingay and Kavanagh 1991). The YBGSE favours large patches of mature old growth forest that provide suitable trees for foraging and shelter (Milledge et al. 1991; Eyre and Goldingay 2003). They also prefer forests with a high proportion of winter-flowering and smooth-barked eucalypts (Kavanagh 1987; Eyre 2004; Irish and Kavanagh 2011). Large areas (i.e. 180–350 km2) are required to support viable sub-populations (Goldingay and Possingham 1995; Eyre 2002; Kambouris et al. 2013). |

| The YBGSE is patchily distributed in wet and dry sclerophyll forest from about Mackay, Queensland, south to near Melbourne with isolated populations in the Otway Range and far south-western Victoria (Kavanagh et al. 1995; Rees et al. 2007). They occur at altitudes ranging from sea level to 1400 m above sea level. In New South Wales, they predominantly occur in forests along the eastern coast, but their distribution also extends inland to the western slopes of the Great Dividing Range (van der Ree et al. 2004). Across its range, the subspecies’ distribution is highly disjunct due to a combination of their specific habitat requirements (Eyre 2004), biogeographic processes and land clearing (Carthew 2004; van der Ree et al. 2004; Rees et al. 2007). Small social groups occupy large and exclusive home ranges and occur at low densities (0.03–0.14 individuals per ha, Goldingay and Kavanagh 1993; Goldingay and Jackson 2004; Woinarski et al. 2014). |

The rapid conversion of mature forest to regrowth in the State forests of Australia has led to specific requirements within logged compartments (or coupes) in some regions (e.g. Environment East Gippsland Inc v VicForest (No 4) 2022 VSC668). These requirements differ from State to State for the same or related species. For example, requirements have been mandated to conserve the YBGSE and GGSC in the context of industrial-scale logging in the Central Highlands and East Gippsland Forest Management Units of the State of Victoria. Thus, on 11 November 2022, Justice Richards issued final orders, which included:

setting out restrictions affecting timber harvesting operations in any coupe in the Central Highlands or East Gippsland in which Southern Greater Gliders and Yellow-bellied Gliders have been detected. Specifically; Southern Greater Gliders’ located home ranges must be excluded from timber harvesting operations; Riparian strips at least 100 metres wide located along all waterways in the coupe must be excluded from timber harvesting operations, with an exclusion area at least 50 metres wide on each side of those waterways; and at least 60% of the basal area of eucalypts in the harvested area of the coupe must be retained (Kinglake Friends of the Forest Inc v VicForests Orders 2022, p. 3).

Thus, the whereabouts of gliders were to be ascertained by the most appropriate means (including spotlighting and playback) within coupes prior to logging activities being carried out in two Forest Management Units in Victoria (see Chick et al. 2020; Wardell-Johnson and Robinson 2023). This enabled adjustment of operational measures to enable long-term sustainability of glider populations in these forests.

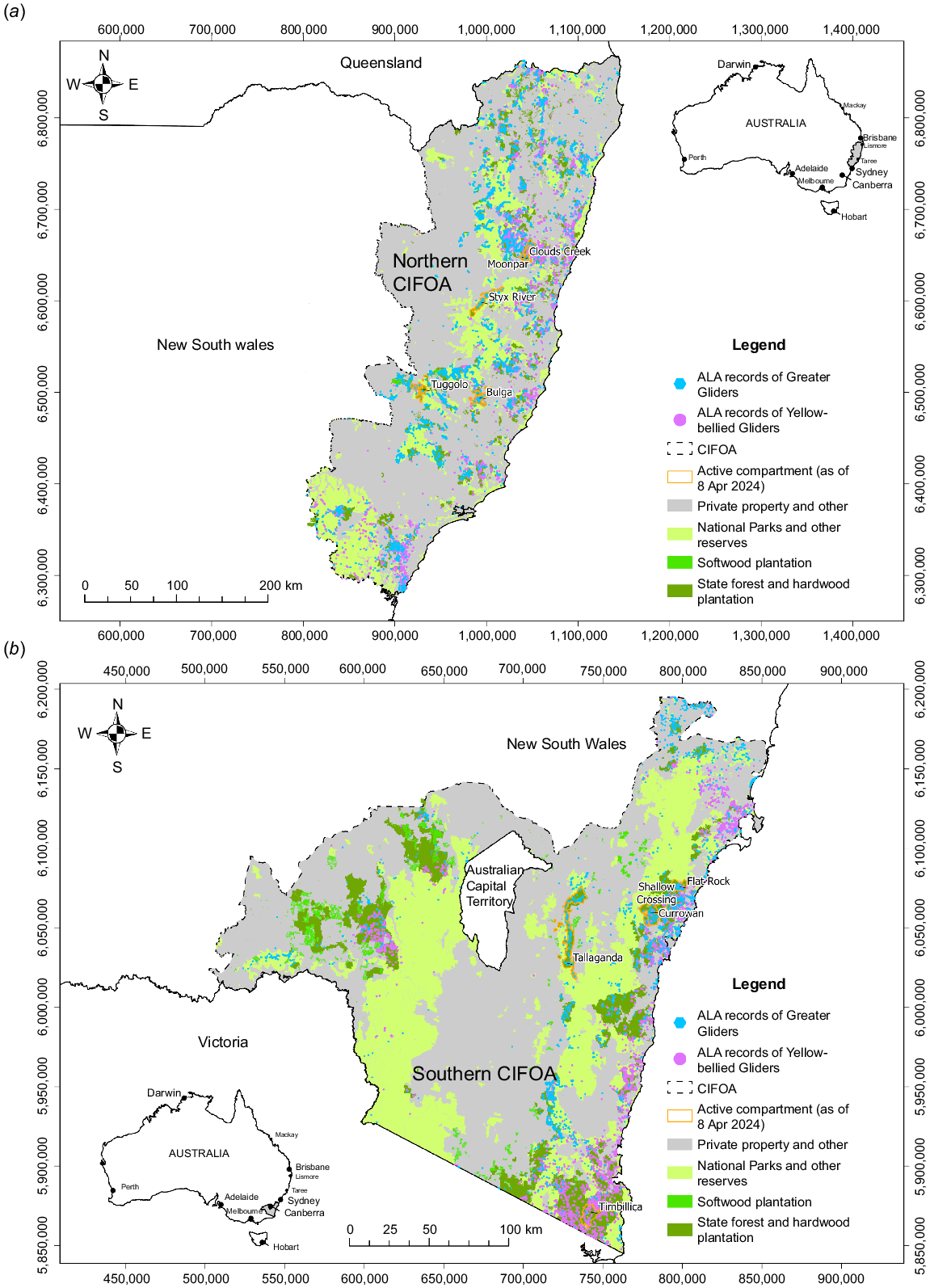

Forestry operations in the State forests of NSW are subject to the Forestry Act 2012 (NSW) (the Act), whereby Forestry Corporation of NSW (FCNSW) is the entity responsible. In 2018, the Minister for the Environment and the Minister for Lands and Forestry developed an integrated forestry approval (IFOA) for the Coastal Region (the CIFOA) of the State (Fig. 1). There, specific operational activities fall under the direction of the NSW Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) – the primary agency responsible for monitoring and compliance. Like in Victoria, the importance of State forests for the conservation of gliders is recognised, but under NSW legislation and regulations, the whereabouts of glider den trees is prioritised (see below), rather than identifying the gliders themselves. Given the requirement for glider conservation in the State forests of NSW, we consider the effectiveness of approaches used to detect and therefore to conserve gliders (and their den trees) in these forests. Assuming the presence of gliders in compartments foreshadowed to be intensively logged, we ask:

Do the CIFOA survey protocols as instigated by the EPA and implemented by FCNSW enable conservation of gliders in compartments subject to intensive logging?

What is the likely outcome for gliders in intensively logged compartments that have not been adequately surveyed, and therefore that lack the protocols for their conservation?

In the context of intensive logging, are there alternative approaches to survey and management that would enable the conservation of gliders in these compartments?

(a) Northern and (b) Southern Coastal Integrated Forestry Approval (CIFOA) areas of New South Wales (NSW), showing Atlas of Living Australia (ALA) records of Greater Gliders and Yellow-bellied Gliders, tenure, and active compartments mentioned in text.

To answer these questions, we first outline the threats to gliders from industrial-scale logging and associated interacting disturbances; and introduce the relevant NSW forestry operations and survey protocols for gliders. In this section, we also outline the data used in this paper, as retrieved from the EPA Native Forestry map viewer. This includes surveys of compartments by FCNSW designated as ‘active’ in 10 State forests throughout the CIFOA of NSW that include substantial numbers of hollow-bearing trees (HBTs) and from where YBGSE or GGSCs have recently been detected. We then examine the effectiveness of survey protocols (including more recent protocols introduced by the EPA and implemented by FCNSW) and the likely outcomes for glider conservation in these forests. Finally, we outline alternative approaches to survey and management in the high conservation State Forests of NSW.

Materials and methods

Species distributions and threats posed by intensive logging in NSW

Both the GGCS (Box 1) and YBGSE (Box 2) may occur wherever there are suitable habitat components (i.e. stands including HBTs) in the two CIFOAs under consideration in this paper. Thus, we show the distribution of these two species in relation to CIFOA boundaries and tenure based on over 30,000 Atlas of Living Australia (ALA) records for the GG and 25,000 records for the YBG (Fig. 1a, b). The extensive gap in the distribution of both species throughout the alpine region covered by the southern CIFOA largely coincides with a lack of, or limited tree cover, and with areas gazetted as National Park.

Logging is a key threat to arboreal marsupials (Eyre and Smith 1997; Lindenmayer et al. 2020) through depletion of large mature trees (McLean et al. 2015), and loss of canopy connectivity and denning/food resources that these provide (Kavanagh 1987; Kavanagh and Lambert 1990). Like the GGCS, the YBGSE prefers old growth forest containing a high abundance of HBTs, in comparison to regrowth forest or forest subject to selective logging rotations (Lindenmayer et al. 1999; Incoll et al. 2001). The YBGSE can persist in areas impacted by logging, provided that old trees are preserved within riparian zones and unlogged forest patches and corridors are retained adjacent to logged land (Goldingay and Kavanagh 1991, 1993; Kavanagh and Bamkin 1995; Eyre and Smith 1997; Kavanagh and Webb 1998), but occurrence decreases with increased logging intensity (Smith et al. 1994; Wormington et al. 2002; Eyre 2007).

Logging interacts with fire to compound the impact of bushfires on HBTs (Lindenmayer et al. 2012; McLean 2012). Thus, intensive logging of eucalypt forests makes them more likely to experience crown fire; and changes microclimates, stand structure and species composition (Lindenmayer et al. 2009; 2022a, 2022b; Price and Bradstock 2012; Taylor et al. 2014; Lindenmayer and Zylstra 2024). Such changes make these forests more prone to ignition and increased fire severity (Lindenmayer et al. 2009; Attiwill et al. 2014; Taylor et al. 2014; Wilson et al. 2018; Lindenmayer and Taylor 2020; Bowman et al. 2021; Furlaud et al. 2021; Lindenmayer et al. 2021; Zylstra et al. 2021; Lindenmayer and Zylstra 2024). HBTs are also threatened by post-fire salvage logging (Noss and Lindenmayer 2006; Lindenmayer et al. 2008; Wardell-Johnson et al. 2024). The threats posed to these once common, but now threatened species (see Lindenmayer et al. 2011a) are increasing. Therefore, their survival under climate disruption caused by global warming depends on effective and reliable survey linked to meaningful management outcomes. The CIFOA protocols appear to reflect this imperative.

Forestry operations and associated survey and conservation protocols for gliders

As at December 2023, CIFOA survey methodology and effort required that FCNSW detect all den trees in the operational area (and potentially within 100 m around it). The CIFOA provided (in conjunction with the definition of ‘den’), among other things, that a 50-m radius exclusion zone (i.e. 0.78 ha) was to be retained around any den tree identified in the broad area habitat search, or previously mapped or recorded. Thus, surveyors must look for, identify and record (among other things) ‘nest, roost or den trees’. A den (specifically in relation to Petaurus australis, Petaurus norfolcensis (Squirrel Glider), and Petauroides volans (collectively, gliders)) includes but is not limited to a tree-hollow, crevice, or fissure in a tree where a glider is seen entering or leaving.

According to the definition, entry or exit of a glider is an indicator of a den. However, it is not the only indicator and the definition does not restrict or qualify the indications that can be relied upon by a surveyor to reach a conclusion that it is likely that a given hollow, crevice, or fissure in a tree is used as a den site. The area within 100 m of the base net area of the area where a forestry operation will occur or is occurring, must be surveyed for den trees where it ‘is known or likely’ that they will exist there. Thus, forestry operations must not be conducted unless an effective den tree survey (among other surveys) is conducted within the whole of the operational area.

Den trees are a subset of the HBTs in a site. HBTs are defined by the EPA (Environment Protection Authority 2014) as dominant or co-dominant living trees with visible hollows, holes, or cavities or are likely to have them. Hollows are not always visible from the ground but may be apparent from the presence of rounded knotty growths, protuberances, or broken limbs, or where the top of the tree has broken off. While HBTs are any trees with hollows (including those suitable as nesting sites for small hollow requiring species (see Gibbons and Lindenmayer 2002), not all such trees are suitable as den sites for the GGCS and YBGSE. These species require large hollows that usually take at least 150 years to form (Box 1, 2).

In addition to safeguarding den trees and associated buffers, FCNSW was required (up until February 2024) to retain eight HBTs per ha, though can log up to the base of these trees. Under changes to EPA protocols (from 9 February 2024, as reviewed by Lindenmayer and Ashman (2024)), the 50-m exclusion zone around known recorded locations of glider dens remained but surveys were no longer required. Instead, loggers were then compelled to protect 14 HBTs per ha in high density glider areas and 12 per ha in low-density areas, as well as future HBTs. These requirements were again changed from 16 February 2024, under GGCS site specific biodiversity conditions (SSBCs) whereby FCNSW were then required to undertake nocturnal surveys for GGCS dens (in addition to previous requirements). On 27 May, the EPA amended the conditions to ensure FCNSWs search and surveys were conducted at night, with the first transect commencing within 30 min of sunset. They were then also required to implement a 25-m logging exclusion zone (approximately 0.2 ha) around any tree where a GGCS is sighted during search and survey.

However, it should be noted that SSBC requirements were only for glider records detected by FCNSW and does not extend to community or citizen science records. Further, the minimum requirements for FCNSW to conduct ‘pre-harvest’ GGCS surveys enabled FCNSW to search for GGCSs across less than 10% of the available operational logging area. The EPA also explained that the February SSBCs did not reflect the shared understanding of the EPA and FCNSW that only the first part of the search and survey had to commence within the first hour of sunset.

We initially consider survey effectiveness based on protocols instigated by the EPA up until 9 February 2024. However, we consider in discussion the implications of these additional protocols for survey success and glider conservation.

EPA Native Forestry map viewer data

Pre-logging surveys carried out by FCNSW include considerable documentation on what was done, when, and by whom. Thus, excerpts from the EPA Native Forestry map viewer show FCNSW operational maps and publicly available planning documents, the history of forestry activity and severity of the 2019/2020 Black Summer bushfires, the status and the location of the State Forest and compartment, location and immediate surroundings of the relevant compartment, assessed patch boundaries and assessed bird nest, roost or den and associated exclusion zone layers. They also show records of retained trees in the compartment and its surrounds, and colour coded attributes of retained trees (and second-tier attributes).

Maps are also provided of survey tracklogs by FCNSW staff in the compartment and its surrounds and GGSC and YBG detections, overlaid on the FCNSW Operational map for the relevant compartment or compartments (with label coloured yellow for detections 2020 or later). Further, maps which zoom in on the relevant detections show the location ID for each detection; and data tabulated to show observation date for each of the detections in the preceding maps, together with the underlying data extracted from NSW Bionet. Maps of individual assessed patches in the vicinity of glider detections recorded in the preceding maps include tracklogs by FCNSW staff in the patch and associated data relating to the patch and retained trees. This is accompanied by a table showing the date, start and end time, and distance of each tracklog by FCNSW staff carrying out the surveys.

We interrogated these data and included active compartments known to include recent detections of GGCSs or YBGSEs within 10 State forests for evaluation (Table 1). These data were downloaded from the EPA Native Forestry map viewer during April 2024 and are a subset of the data available from this map viewer. We used these data to compile a summary of the characteristics of these compartments, survey efforts by FCNSW staff, and the resultant decisions concerning protection efforts for gliders in the context of planned logging operations (Table 1) . A point-based shapefile of all assessed and retained trees in both the southern and northern CIFOA was acquired from the FCNSW Open Data Site. HBTs were extracted using SQL (where TreeType = 3 orTreeType2 = 3 or TreeType3 = 3) within ArcGIS PRO 3.0 (ESRI 2020). A raster grid with a 100-m resolution (i.e. 1 ha) was overlaid onto the point-based data and the number of points that fell within each totalled, providing a surface of HBTs per ha. Locations that had not been assessed were set to null to avoid artificial deflation of the summary statistics (mean and s.d.) extracted and included in Table 1.

| State forest | Compart no. | Area (ha) | HBT per ha | Assess HBTs | No. of Yellow-bellied Gliders (since 2020) | No. of Greater Gliders (since 2020) | No. of den trees detected | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | s.d. | ||||||||

| (a) Compartments located in the Southern CIFOA | |||||||||

| Currowan | 485A 486A | 307 173 | 6.7 7.8 | 4.2 5.6 | Day | 5 (1) | 0 | ||

| Flat Rock | 34A | 162 | 6.2 | 4.3 | Day | 2 | 4 (3) | 0 | |

| Shallow Crossing | 208A 209A 210A | 267 209 349 | 6.2 6.8 6.5 | 3.4 3.9 3.8 | Day | 7 (1) | 6 (3) | 0 | |

| Tallaganda | 2208A 2209A | 244 247 | 6.9 5.9 | 3.8 3.2 | Day | (4) | 0 | ||

| Tallaganda | 2447A 2448A 2449A 2450A | 341 325 175 230 | 5.4 4.6 4.9 5.8 | 3.1 2.1 2.7 3.2 | Day | 91 (19) | 0 | ||

| Timbillica | 228A 232A 233A | 230 261 289 | 5.2 6.1 5.6 | 3.3 3.8 3.2 | Day | 10 (2) | (3) | 0 | |

| (b) Compartments located in the Northern CIFOA | |||||||||

| Bulga | 041 | 176 | 5.4 | 3.8 | Day | 50 (39) | 0 | ||

| Clouds Creek | 034 035 036 037 039 | 237 244 167 283 202 | 4.8 3.7 2.6 4.1 3.2 | 3.3 2.6 2.2 3.1 2.3 | Day | 16 | (4) | 0 | |

| Moonpar | 13 | 112 | 4.0 | 3.4 | Day | 9 (3) | 10 (8) | 0 | |

| Styx River | 41 | 204 | 5.1 | 3.1 | Day | 47 (12) | 0 | ||

| Tuggolo | 21 | 347 | 3.7 | 2.7 | Day | 5 (3) | (11) | 0 | |

Results

CIFOA protocols and conservation of gliders in intensively logged compartments

All listed compartments within the 10 areas of State forests have records of either YBGSEs and/or GGSCs, including very recent records (Table 1). This is despite no apparent attempt to identify any species of glider during surveys (all surveys were conducted in daylight hours). These compartments also have abundant records of HBTs, as demonstrated by some retention, although usually at lower levels than designated (Table 1). Note that some or many of these designated HBTs may be relatively small or contain only very small hollows, unsuitable as den trees for these gliders.

Surveys for HBTs were conducted in each of the compartments in each of the 10 areas of State forests assessed. However, it was not possible to say from the records whether one or other of the retained (or logged) HBTs is or is not a glider den tree. It should be noted that Bionet records show some to many YBGSEs or GGSCs in (or in very close proximity to) each of these compartments (Table 1). Therefore, it is virtually certain that numerous glider den trees occur (or occurred) in each of the compartments in these 10 State forests (Table 1). Nevertheless, no den trees for either species were reported and no den tree and associated 50 m buffer was foreshadowed to be retained during and after logging of these compartments.

More recent protocols instigated by the EPA

Effort by FCNSW to survey for den trees throughout the operation of the CIFOA to February 2024 was carried out in daylight hours, preventing identification of glider den trees. While protocols instigated by the EPA on 9 February 2024 removed the need for survey, these were reintroduced soon after (16 February 2024), along with the requirement to survey within 1 h following sunset (27 May 2024). While no difference in conservation outcome could be expected by the implementation of EPA requirements introduced in early February 2024 (although retention of 14 HBTs per ha is a considerable increase in retained HBTs and in basal area over the prior rate) subsequent amendments recognised that gliders tend to leave their dens to forage within about an hour of sunset. Thus, more recent requirements to commence survey at dusk provides an improved opportunity to detect gliders and their dens.

Discussion

CIFOA protocols and conservation of gliders in intensively logged compartments

The data (April 2024) suggests that no serious attempt was made to detect glider den trees in the compartments in the 10 State forests assessed to that time. Further, we have not seen any evidence of follow-up surveys used to relate glider sightings with HBTs, or evidence of spotlight (with or without playback) survey data, radio tracking data, or drone survey data in these compartments that could have provided evidence of glider den trees. Thus, surveys appeared not to be compliant with any methodology, survey protocols, or minimum survey effort requirement in relation to detecting glider dens. In other words, surveys for glider dens appear to have been ineffective, invalid, and unreliable scientifically (see Green 1979; Shrader-Frechette and McCoy 1993; Peters 1995). It is therefore reasonable to assume that by April 2024, glider den surveys were not actually carried out or not reported if they were.

Therefore, it could be concluded that the requirement in Condition 57.2 (c) of the CIFOA ‘that a broad area search be conducted that will, among other things, identify glider den trees’ was not complied with. While many HBTs were identified, FCNSW recognised the inadequacy of their survey efforts concerning locations of glider dens (see FCNSW 2023). However, recent efforts by FCNSW reported in ‘The National Tribune’ (see below) also appear inadequate.

If glider conservation is to be a consideration in forest management, then follow-up field work is required to ascertain whether these HBTs are (or are not) glider dens. It would therefore be appropriate to carry out surveys at night using spotlight protocols (see Chick et al. 2020; Cripps et al. 2021; Wardell-Johnson and Robinson 2023), radio tracking, or appropriate drone surveys (with appropriately developed protocols – see below).

Indeed, more recent work carried out by FCNSW and by Forest Alliance NSW (2024) in four of these State forests (i.e. Tallaganda, Tuggolo, Bulga, and Styx River; see Fig. 1) demonstrates an apparent inability for FCNSW to detect gliders or den trees that are readily detected by citizen scientists. Thus, community surveys (see Forest Alliance NSW 2024) detected 170 den trees, while FCNSW detected just 15 in compartments in these State forests. Further, community surveys detected 825 GGSCs, while FCNSW found 229. Thus, Forest Alliance NSW (2024) concluded that less than 1% of den trees are found by FCNSW using most recent requirements of the SSBC. Forest Alliance NSW (2024) concluded that the number of records of GGSCs is positively correlated with the number of surveys conducted, and that FCNSW apparently recognises that it is not in their interest to find GGSC or their den trees. This is because each record reduces the immediate logged area. Regardless, the failure to detect gliders or den trees when they are present has profound conservation implications.

Outcomes for gliders in intensively logged compartments not surveyed for den trees and therefore without appropriate measures to safeguard them

Recent detections of gliders (GGSC or YBGSE) in each of these compartments by parties independent of FCNSW (both to December 2023, and more recent detailed surveys) occurred despite FCNSW’s failure to detect den trees or gliders. The likely outcome of the failure to ‘conduct broad area searches that will, among other things, identify glider den trees’ is to permanently reduce these glider populations. Initially, the logging operation as planned would kill all or most of the GGSC in the compartment, either during the logging operation or soon thereafter (from predation, starvation, or exposure (see Tyndale-Biscoe and Smith 1969). The logging operation then renders the environment hostile to this species and unsuitable for other MFDS for upwards of 50 years (see Wardell-Johnson and Robinson 2023). However, by this time, most areas are scheduled to be relogged (Fig. 2a). Therefore, these environments are designated to remain permanently hostile to gliders.

Hostile environments, terminal habitat, and tomb trees in the State forests of NSW. Memorial trees in an area twice intensively logged within 60 years in (a) Nullica State Forest, (b) isolated hollow-bearing and habitat trees killed by high-intensity fire in Yambulla State Forest, (c) hostile environments for gliders (areas logged less than 50 years previously) burnt in the 2019/2020 wildfires, Nullica State Forest, and (d) tomb tree Tallaganda State Forest. All photos: Grant Wardell-Johnson.

GGSCs using den trees that have not been detected and that will be felled will most likely die directly because of the logging operation, either at the time of the operation or soon thereafter. Thus, the fate of individuals of this species following intensive logging has been well-known for over 50 years (i.e. since the pioneering work of Tyndale-Biscoe and Smith 1969). In the meantime, both the GGSC and YBGSE have shown dramatic declines in abundance associated with intensive logging carried out extensively, exacerbated by recent (2019/2020) large-scale fire events (see review by Driscoll et al. 2024).

Individual gliders using den trees that are retained as HBTs, but without the requisite buffer, are likely to be very similar to those whose den trees are removed. Thus, they are severely exposed to predators and a lack of food after the logging and burning operation. Therefore, it is likely that den trees that were not protected by a buffer of 50 m would no longer serve as den trees following the intensive logging operations. Further, recently exposed individual trees are much more prone to windthrow (see Sinton et al. 2000) or being impacted by wildfire events (e.g. Fig. 2a, b) than trees within a retained buffer (Lindenmayer and Taylor 2020). This has important implications concerning eventual recovery of stand structure.

Thus, retained HBTs (and any associated glider) without a buffer face an extreme form of edge effect (Nelson et al. 1996; Youngentob et al. 2012). These isolated retained HBTs (some of which may have been den trees) will therefore effectively serve as tomb trees (Fig. 2d) to any glider present at the time of the logging operation. While tomb trees serve as crucial components in the redevelopment of stand structure (e.g. Manning et al. 2006; Fischer et al. 2010), they also denote the loss (potentially permanently) of gliders through intensive logging in that compartment.

Unfortunately, based on operational activities elsewhere in NSW, logging return times are foreshadowed to be less than 60 years (see Wardell-Johnson and Robinson 2023). Therefore, these sites are effectively rendered permanently hostile to gliders. The evidence suggests that this constitutes serious and irreversible damage to these gliders and their environment (see Wardell-Johnson and Robinson 2023; Wardell-Johnson et al. 2024). It should be noted that many areas are now being (or have recently been) intensively logged for the second time since the commencement of woodchipping in NSW in 1968 (e.g. Fig. 2a). Initially, clearfelling without HBT retention was the usual practice (see Routley and Routley 1974). On the second rotation, isolated HBTs have been retained (despite no gliders now being present). Therefore, these HBTs serve as memorials (e.g. Fig. 2a) to populations of gliders that previously occupied the area (i.e. secondary tomb trees).

GGCS occupy home ranges of between 1.3 and 4 ha, with home ranges being larger in poorer quality habitat. Unfortunately, a 25-m logging exclusion zone (approximately 0.2 ha) around any tree where a GGSC is sighted during search and survey provides only a small area of suitable habitat within their home range, surrounded by hostile environments. This situation continues for at least 50 years (or permanently as a consequence of further logging rotations). This situation therefore condemns individual gliders to terminal habitat, as they will most likely be predated at the edges of this zone. Considering their high sensitivity to edge effect, nothing less than protection of the home range of GGCS is likely to provide opportunity for their conservation (see Environment East Gippsland Inc v VicForest (No 4) 2022 VSC668). The islands of terminal habitats for gliders formed by intensive logging are not akin to ecological (Mason et al. 2018) traps since individuals are not induced to them. Rather, they become trapped in them when the habitat around them is transformed or destroyed (as in landscape traps – Lindenmayer et al. 2011b, 2022a).

Thus, the evidence suggests that there is a real threat of serious or irreversible damage to the environment from industrial-scale logging without a prior understanding of the locations of either glider home ranges or of glider den trees. This understanding can only be achieved by effective survey (see for example Environment East Gippsland Inc v VicForest (No 4) 2022 VSC668). The methodology of this survey should be both reliable (i.e. be able to do the job asked of it) and be valid scientifically (i.e. be able to be repeated by other observers elsewhere given the same wherewithal). The approach to February 2024 was ineffective as it was apparently neither valid nor reliable. Further, survey efforts based on recently introduced protocols have apparently provided little improvement to the situation.

Alternative approaches of survey to conserving gliders

Knowing the whereabouts of individuals of species or of vital habitat features known to be impacted by logging operations is essential for wildlife conservation (Gibbons and Lindenmayer 2002; Crane et al. 2008, 2010). It is even more important where the conservation of these species at the compartment (and thus landscape and region) level is dependent on their retention during intensive logging operations (or other forms of disturbance). Given the requirement to conserve populations of threatened fauna in the context of intensive logging, one might enquire as to how this might best be done. Two approaches may be used: one that is directed towards the target animal; and the other directed towards target resources. In Victoria, the target animal approach was found to be efficacious. However, decades of research have provided ample knowledge of both the species and their requirements to allow either approach to be viable with current knowledge. Thus, in the context of resource extraction, the commitment (or otherwise) of agencies to constructively engage in surveys to enable appropriate adjustment of operational plans effectively determines the long-term sustainability of glider populations.

The target animal approach initially involves a thorough search of the compartment and its surrounds at night for the target animal (in this case GGCSs and YBGSEs). This has been through active spotlighting or spotlighting with playback (as discussed by Chick et al. (2020), Cripps et al. (2021) and Wardell-Johnson and Robinson (2023). This can also be linked with radio-tracking. Technological developments have enabled radio tracking to become highly advanced and these species have both been successfully radio-tracked (e.g. GGCS, Smith et al. 2007; McGregor et al. 2023; YBGSE, Goldingay et al. 2018). Radio-tracking provides excellent information on individual gliders, including identification of their den sites; and provides the certainty of matching species and individual to den, but requires capture and release.

In Victoria, it was recognised that spotlighting (and spotlighting with playback) is achievable (with associated protocols – see Chick et al. 2020 and adoption for use within planned compartments; Wardell-Johnson and Robinson 2023). Such an approach enabled logging to proceed once the home range of the target animal was determined and set asides that included the home ranges of individual GGCS and appropriate unlogged buffers and intensity of logging within the coupe or compartment (to cater for the YBGSE) implemented. Were a determination of the locations of den trees also to be considered necessary this could be achieved without the constraints of timelines dictated by timber supply commitments.

More recently, thermal cameras attached to drones have been used to locate gliders when they are not in their dens (e.g. Vinson et al. 2020). While the use of drone technology in association with heat detection can be used for glider surveys (when they are not in their dens) extensive analysis demonstrates that the same protocols developed for specialist survey (e.g. Chick et al. 2020; Wardell-Johnson and Robinson 2023) and other species (for example, see DSEWPC 2010, 2011a, 2011b) are also required for the use of drones and their associated camera equipment. Thus, drone surveys are an important direction in wildlife survey, but that scientific validity and reliability tests (Buters et al. 2019) to ascertain species presence as well as population levels are required when using this technology.

Bearing these considerations in mind, Vinson et al. (2020) developed and tested the efficacy of a real time thermography technique to improve survey methods for Australian arboreal mammal species, based on the Southern Greater Glider (SGG) at Seven Mile Beach National Park, NSW. A protocol for the use of thermography to survey SGGs was developed. The efficacy of the thermography protocol was then experimentally tested in comparison to traditional spotlighting. Thus, Vinson et al. (2020) demonstrated that thermography is a viable approach for undertaking arboreal mammal surveys.

A second approach directly targets the dens (a resource target) themselves. Here, the intention is not to identify the home range of gliders prior to logging operations, but rather to directly target a limiting habitat component (i.e. the den). One advantage of this approach is that a relatively rapid assessment can be made of the HBTs within a compartment. This can be useful for comparative and predictive purposes, for developing an understanding of the broader values within the compartment, and for understanding the old-growth characteristics for flagging the presence of den trees. Thus, it is well known that tree hollows are an important landscape resource used by fauna for shelter, nesting, and predator avoidance (Gibbons and Lindenmayer 2002).

Thus, the identification of all HBTs is part of the process, but it is not the critical part in the context of foreshadowed intensive logging operations. This process initially involves survey for HBTs to ensure thorough coverage of the compartment and surrounds. The second stage involves determining HBTs that are glider den trees, again requiring full coverage of the compartment and its immediate surrounds. This is most appropriately carried out by spotlight (with and without playback) within 2 h of sunset (i.e. as the gliders are leaving their dens). This would need to be conducted over several nights to achieve reasonable coverage, even of the dens currently being used. Both species, but especially the YBGSE, may use a different suite of dens at different times of the year (Goldingay et al. 2018).

Given that a key component of the target resource approach is to accurately allocate HBT to den site, and to geolocate and mark on the ground, spotlighting is an essential part of the process. Thus, spotlighting should be conducted when individual gliders are most likely to be emerging from their dens (i.e. within 2 h after sunset). However, given the level of uncertainty in detecting gliders and a further level of uncertainty as to whether they might be seen emerging from their dens, it is necessary for at least three passes of the same site within 2 h of sunset, preferably on different days. As has been determined in Victoria (where gliders rather than dens were the consideration), these spotlight surveys (for the GGCS) should not be more than 50 m from one another (whether by transect or other approach). In other words, multiple passes and full coverage of the area likely to be affected by the logging operation is required. Note that under current guidelines, conservation of the habitat of gliders does not depend on identification of all den trees in the compartment. This is because identification of a den tree mandates retention of a 50-m radius buffer. Therefore, identification of den trees within 100 m of one another ensures the retention of all habitat across the gliders home range.

Given that one or more species of glider is likely to occur (or be resident in) in State forest that includes mature eucalypt trees, it is necessary to conduct appropriate surveys for glider den trees in all areas of State forest within the Northern and Southern CIFOA areas prior to logging. FCNSW is aware of the need to locate glider dens. Thus (as reported in The National Tribune, 20 December 2023), the General Manager Hardwood Forests, Daniel Tuan, reported that since the EPA raised concerns in Tallaganda State Forest in August 2023, FCNSW had been working with the EPA to understand the new desired survey requirements for dens and trialling new methods to achieve this.

In the past we used spotlight transect sample surveys to search for Greater Gliders themselves to understand the density of glider populations in forests. These were conducted in the hours after sunset along tracks and trails to ensure it was safe for the people walking in the bush after dark and dens were seldom sighted (my italics). It was thought that thermal UAVs might offer a better alternative to finding dens so we have been trialling different technologies and methods in these two forests. (The National Tribune, 20 December 2023)

Across Tallaganda and Flat Rock State Forests, 8 nights of targeted GGCS surveys were undertaken involving over 30 UAV flights.

In Tallaganda we already knew Greater Gliders were present as we have been undertaking a monitoring program there for several years which has detected hundreds of records. In these latest trials with UAVs we found over 80 individual Greater Gliders but the technology did not allow us to identify any dens. In Flat Rock, which is a coastal forest less suitable for Greater Gliders, we found 2 individual Greater Gliders but again no dens. (The National Tribune, 20 December 2023)

In other words, the use of thermal cameras and drones was not sufficient to identify glider dens without greater development of methodology, protocols, commitment, and approach. Further, ecological experience and commitment is necessary for den surveys to be effective and to be scientifically valid and reliable. Thus, Hofman et al. (2023) provided an overview of the dimensions and characteristics of the den trees and hollows used by an endangered population of GGs by spotlighting and stag-watching. However, even with spotlight survey over several nights, it remained uncertain as to whether all den trees were detected. This is because gliders change den tree use from day to day, and use of den trees changes with seasons (especially for YBGSEs). Therefore, detection of den trees that are used is likely to only become certain once the home range of the glider or colony of gliders is known. In other words, detection of all den trees used by an individual glider (even during one season) requires a significant commitment of resources (personnel, time, equipment). Therefore, glider conservation is best achieved based on the detection of the gliders themselves and protecting their generalised home range rather than their dens and associated buffers.

Compromises to enable logging and the conservation of endangered gliders

Without effective survey, strategic planning and specific management prescriptions, there is potential for native forests to no longer support MFDS such as endangered gliders at the compartment scale, and therefore to compromise conservation at the block or landscape scale (Lindenmayer et al. 2020; Smith 2020; Wardell-Johnson and Robinson 2023), thereby further reducing the function and values of forests. As a result, recent court cases (e.g. Environment East Gippsland Inc v VicForests (No 4) (2022) VSC 668) have argued that the scale and nature of the industrial-scale logging activity carried out in two Forest Management Units in the State of Victoria has led to serious and irreversible environmental damage to gliders and other MFDS. That is why retention of the home ranges of GGs, stream zones (100 m total width on all streams) and 60% basal area in logged areas were all considered necessary to provide opportunity for conservation of gliders there. This situation also applies in NSW.

Thus, it has been recognised in law in one Australian State that if MFDS are to be provided with opportunity to persist, serious strategic planning and conservation attention is required in the context of timber production. Thus, in coups foreshadowed to be logged in two Forest Management Units in Victoria, the whereabouts of high conservation values must be known (and located by the most appropriate means) so that their habitat can be protected. Further, within areas logged, a substantial reduction in the intensity of the logging operation is required.

As recognised in Victoria, it is easier to locate gliders than to locate their den trees. Thus, the targeting of species rather than their resources is more viable when the aim is to conserve populations of threatened species in the context of efficacy and reliability in survey. Regardless, where there is an apparent lack of will to achieve conservation outcomes within the agency (e.g. in Victoria, Environment East Gippsland Inc v VicForests (No 4) (2022) VSC 668), such outcomes require effective legislation and monitoring for compliance following intervention through the court process.

Thus, when ‘resource’ supply commitments lead to known (even if contested) irreversible environmental damage, there are more important considerations for conservation in the application of survey protocols than determining whether survey focus should be on the resource or the species. Regardless of a resource-led or species-led focus, it is difficult to imagine a process to ensure conservation within an organisation that places immediate resource supply ahead of sustainability (see Ludwig et al. 1993; Hilborn et al. 1995). To date, the evidence suggests that the numerous additional protocols provided by the EPA to FCNSW during 2024 have not improved outcomes for glider conservation.

Doubt concerning a commitment to conservation by FCNSW is highlighted by a recent judgement in the NSW Land and Environment Court (Cox 2024) brought by the NSW EPA. In this case, Justice Pepper fined FCNSW A$360,000 for offences related to illegally logging 53 trees in an environmentally significant forest near Eden (in the state’s south), after the 2019/2020 bushfires. Here, the court accepted an EPA submission that the agency had ‘a pattern of environmental offending, has not provided any compelling evidence of measures taken by it to prevent its reoffending, and does not accept the true extent of harm that it has caused by its offending’. Thus, Justice Pepper agreed that any penalty imposed on FCNSW ‘must serve to deter it from future criminality’. The court found an affidavit filed by FCNSW chief executive, Anshul Chaudhary, ‘constitutes no more than a bare expression of contrition and remorse’ and that FCNSW had not taken steps to remediate the harm it had caused.

Given the generality and magnitude of the impact of repeated industrial-scale logging on gliders, a case involving 53 trees near Eden, NSW is reminiscent of Inspector Clouseau and the blind beggar (Edwards 1975). Nevertheless, it does suggest a broader pattern of behaviour and seems commonplace in forestry, both nationally (e.g. Environment East Gippsland Inc v VicForest (No 4) 2022 VSC668) and internationally (e.g. Bosselmann 2010: Dancer 2021; Meriläinen and Lehtinen 2022; Nunes et al. 2024; Rohmy et al. 2024). Thus, it is necessary for oversight to be more generally mandated in the community and this oversight to be enforceable in law should conservation be considered a priority for society in the context of resource extraction. Where government agencies are responsible for oversight (even where separate or answerable to different Ministers), political capture, resource constraints, and conflicts of interest are inevitable. Thus, conflict of interest becomes a particular concern when the agencies responsible for resource extraction are also responsible for the research and monitoring of that activity, especially when not answerable to a wider body.

Scientific suppression in Government departments whereby staff are ‘rewarded or penalized on the basis of complying with opinions of senior staff regardless of evidence’ has been demonstrated (Driscoll et al. 2021). These rewards and punishments are highly consequential, defining the success or failure of individual careers subject to Government funding (Martin 1999, Driscoll et al. 2021; Zylstra and Wardell-Johnson 2024). This situation demonstrates the difficulty of enforcing conservation in an agency responsible for short-term supply commitments, even when these commitments lead to irreversible environmental harm.

Perhaps more consequential than ‘rewards and penalties’, Weberian understanding (see Bullock and Trombley 1999) suggests that people become rule-bound and uncreative in organisations and bureaucracies as they pursue narrow, specialised tasks, preventing effective oversight. Thus, extensive documentation of inconsequential activity is encouraged, driving decision making to the detriment of broader societal interest. Max Weber introduced the concept of the ‘iron cage’ to describe the increased rationalisation inherent in social life, particularly in Western capitalist societies (Baehr 2001). This ‘iron cage’ traps individuals in systems based purely on teleological efficiency, rational calculation and control at the expense of contemporary social values (Wardell-Johnson et al. 2019). Thus, Weber’s ‘polar night of icy darkness’ (Lassman 1994) becomes a rationalisation of bureaucratic processes rather than for species conservation.

Until the influence of bureaucracy and the culture of scientific suppression and Government influence on research and monitoring can be addressed, mandated requirements via third parties effectively supported in law remains the only viable oversight to enable effective conservation outcomes. Thus, even if the best possible protocols were in place, independence in the survey process itself is the most essential characteristic of the survey.

Conclusion

Unfortunately, rather than recognising the shortcomings of FCNSW’s survey effort in terms of commitment, effectiveness, reliability and validity, the NSW EPA has regularly updated protocols to increase levels of compliance based on a Weberian vision. Regardless, even with the strictest protocols, it is always possible for agencies to avoid protocols that impact on supply commitments. Thus, neither the target species nor the target resource approach has been effectively operational within organisations with a charter for resource supply. Only effective regulation, monitoring, and compliance (ultimately through intervention by third parties via the legal process) is likely to ensure effective conservation outcomes in organisations tied to resource supply commitments on publicly managed lands. Regardless, hostile environments, terminal habitats, and tomb trees are the legacy of the recent six decades of industrial-scale forestry in the State forests of NSW. In this light, the apparent systemic failure to survey for MFDS has had irreversible consequences for biodiversity. This failure to conserve biodiversity has also placed forest communities at risk from increasingly consequential interactions associated with climate disruption on these transformed forests.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable as no new data were generated or analysed during this study.

Declaration of funding

This research did not receive any specific funding, but the paper was based on an Expert Report prepared as a Brief for XD Law and Advocacy Pty Ltd acting on behalf of South East Forest Rescue Inc to provide expert advice in relation to survey methodology by the Forestry Corporation of NSW for den trees of gliders in the context of proposed ‘timber harvesting operations’ in the State forests of New South Wales.

Acknowledgements

We thank Jonathan Korman and Natalija Nikolic for enabling this research; Angela Wardell-Johnson for sociological insight into environmental governance processes, and for helpful discussion and advice; Associate Editor of Pacific Conservation Biology, Ross Goldingay, for helpful comments; and an anonymous referee on earlier versions of this paper.

References

Attiwill PM, Ryan MF, Burrows N, Cheney NP, McCaw L, Neyland M, Read S (2014) Timber harvesting does not increase fire risk and severity in wet eucalypt forests of Southern Australia. Conservation Letters 7(4), 341-354.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Baehr P (2001) The “Iron Cage” and the “Shell as Hard as Steel”: Parsons, Weber, and the Stahlhartes Gehäuse metaphor in the protestant ethic and the spirit of capitalism. History and Theory 40(2), 153-169.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Bosselmann K (2010) Losing the forest for the trees: environmental reductionism in the law. Sustainability 2(8), 2424-2448.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Bowman DMJS, Williamson GJ, Gibson RK, Bradstock RA, Keenan RJ (2021) The severity and extent of the Australia 2019–20, Eucalyptus forest fires are not the legacy of forest management. Nature Ecology and Evolution 5, 1003-1010.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Buters TM, Bateman PW, Robinson T, Belton D, Dixon KW, Cross AT (2019) Methodological ambiguity and inconsistency constrain unmanned aerial vehicles as a silver bullet for monitoring ecological restoration. Remote Sensing 11(10), 1180.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Comport SS, Ward SJ, Foley WJ (1996) Home ranges, time budgets and food-tree use in a high-density tropical population of greater gliders, Petauroides volans minor (Pseudocheiridae: Marsupialia). Wildlife Research 23(4), 401-419.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Crane MJ, Montague-Drake RM, Cunningham RB, Lindenmayer DB (2008) The characteristics of den trees used by the squirrel glider (Petaurus norfolcensis) in temperate Australian woodlands. Wildlife Research 35(7), 663-675.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Crane MJ, Lindenmayer DB, Cunningham RB (2010) The use of den trees by the squirrel glider (Petaurus norfolcensis) in temperate Australian woodlands. Australian Journal of Zoology 58(1), 39-49.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Cripps JK, Nelson JL, Scroggie MP, Durkin LK, Ramsey DSL, Lumsden LF (2021) Double-Observer distance sampling improves the accuracy of density estimates for a threatened arboreal mammal. Wildlife Research 48(8), 756-768.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Dancer H (2021) People and forests at the legal frontier: introduction. The Journal of Legal Pluralism and Unofficial Law 53(1), 11-20.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Driscoll DA, Garrard GE, Kusmanoff AM, Dovers S, Maron M, Preece N, Pressey RL, Ritchie EG (2021) Consequences of information suppression in ecological and conservation sciences. Conservation Letters 14, e12757.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Driscoll DA, Macdonald KJ, Gibson RK, Doherty TS, Nimmo DG, et al. (2024) Biodiversity impacts of the 2019–2020 Australian megafires. Nature 635, 898-905.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Edwards B (1975) The Return of the Pink Panther. ITC Entertainment. Available at https://youtube/-iYbBrTwXmw?si=3vtf2OiMXl6ZRVen

Eyre TJ (2007) Regional habitat selection of large gliding possums at forest stand and landscape scales in southern Queensland, Australia: II yellow-bellied glider (Petaurus australis). Forest Ecology and Management 239, 136-149.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Eyre TJ, Goldingay RL (2003) Use of sap trees by the yellow-bellied glider near Maryborough in south-east Queensland. Wildlife Research 30, 229-236.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Eyre TJ, Smith AP (1997) Floristic and structural habitat preferences of yellow-bellied gliders (Petaurus australis) and selective logging impacts in southeast Queensland, Australia. Forest Ecology and Management 98, 281-295.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Fischer J, Stott J, Law BS (2010) The disproportionate value of scattered trees. Biological Conservation 143(6), 1564-1567.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Forest Alliance NSW (2024) Nature Negative. How governments are pushing greater gliders towards extinction in NSW. Available at https://apac01.safelinks.protection.outlook.com/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fassets.nationbuilder.com%2Fnatureorg%2Fpages%2F2722%2Fattachments%2Foriginal%2F1728957958%2FNATURE_NEGATIVE_FANSW_Report_CP.pdf%3F1728957958&data=05%7C02%7C%7C7655222f28b346f4028d08dd1418ab72%7C84df9e7fe9f640afb435aaaaaaaaaaaa%7C1%7C0%7C638688818390726206%7CUnknown%7CTWFpbGZsb3d8eyJFbXB0eU1hcGkiOnRydWUsIlYiOiIwLjAuMDAwMCIsIlAiOiJXaW4zMiIsIkFOIjoiTWFpbCIsIldUIjoyfQ%3D%3D%7C0%7C%7C%7C&sdata=UGQDwW0E%2BVWeaOAlvI7epkAnF7b32LaqO9KycKOXM5E%3D&reserved=0

Furlaud JM, Prior LD, Williamson GJ, Bowman DMJS (2021) Fire risk and severity decline with stand development in Tasmanian giant Eucalyptus forest. Forest Ecology and Management 502, 119724.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Goldingay RL (1992) Socioecology of the yellow-bellied glider (Petaurus-Australis) in a coastal forest. Australian Journal of Zoology 40, 267-278.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Goldingay RL (1994) Loud Calls of the yellow-Bellied glider, Petaurus australis-Territorial Behavior by an Arboreal Marsupial. Australian Journal of Zoology 42, 279-293.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Goldingay RL, Kavanagh RP (1993) Home-range estimates and habitat of the yellow-bellied glider (Petaurus australis) at Waratah Creek, New South Wales. Wildlife Research 20, 387-403.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Goldingay R, Possingham H (1995) Area requirements for viable populations of the Australian gliding marsupial Petaurus australis. Biological Conservation 73, 161-167.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Goldingay RL, McHugh D, Parkyn JL (2016) Population monitoring of a threatened gliding mammal in subtropical Australia. Australian Journal of Zoology 64, 413-420.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Goldingay RL, Carthew SM, Daniel M (2018) Characteristics of the den trees of the yellow-bellied glider in western Victoria. Australian Journal of Zoology 66, 179-184.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hilborn R, Walters CJ, Ludwig D (1995) Sustainable exploitation of renewable resources. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 26, 45-67.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hofman M, Gracanin A, Mikac KM (2023) Greater glider (Petauroides volans) den tree and hollow characteristics. Australian Mammalogy 45(2), 127-137.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Incoll RD, Loyn RH, Ward SJ, Cunningham RB, Donnelly CF (2001) The occurrence of gliding possums in old-growth forest patches of mountain ash (Eucalyptus regnans) in the Central Highlands of Victoria. Biological Conservation 98, 77-88.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Irish P, Kavanagh R (2011) Distribution, habitat preference and conservation status of the yellow-bellied glider (Petaurus australis) in The Hills Shire, northwestern Sydney. Australian Zoologist 35, 941-952.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Jones KE, Bielby J, Cardillo M, Fritz SA, O’Dell J, Orme CDL, Safi K, Sechrest W, Boakes EH, Carbone C, Connolly C, Cutts MJ, Foster JK, Grenyer R, Habib M, Plaster CA, Price SA, Rigby EA, Rist J, Teacher A, Bininda-Emonds ORP, Gittleman JL, Mace GM, Purvis A (2009) PanTHERIA: a species-level database of life history, ecology, and geography of extant and recently extinct mammals. Ecology 90, 2648.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Kambouris PJ, Kavanagh RP, Rowley KA (2013) Distribution, habitat preferences and management of the yellow-bellied glider, Petaurus australis, on the Bago Plateau, New South Wales: a reassessment of the population and its status. Wildlife Research 40, 599-614.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Kavanagh RP (1987) Forest phenology and its effect on foraging behavior and selection of habitat by the yellow-Bellied glider, Petaurus-Australis Shaw. Wildlife Research 14, 371-384.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Kavanagh RP (2000) Effects of variable-intensity logging and the influence of habitat variables on the distribution of the greater glider Petauroides volans in montane forest, southeastern New South Wales. Pacific Conservation Biology 6, 18-30.

| Google Scholar |

Kavanagh RP, Bamkin KL (1995) Distribution of nocturnal forest birds and mammals in relation to the logging mosaic in south-eastern New South Wales, Australia. Biological Conservation 71, 41-53.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Kavanagh RP, Lambert MJ (1990) Food selection by the Greater Glider, Petauroides-volans- is foliar nitrogen a determinant of habitat quality? Australian Wildlife Research 17(3), 285-299.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Kavanagh RP, Rohan-Jones WG (1982) Calling behaviour of the yellow-bellied glider, Petaurus australis Shaw (Marsupialia: Petauridae). Australian Mammalogy 5, 95-111.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Kavanagh RP, Webb GA (1998) Effects of variable-intensity logging on mammals, reptiles and amphibians at Waratah Creek, southeastern New South Wales. Pacific Conservation Biology 4, 326-347.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Kavanagh RP, Debus S, Tweedie T, Webster R (1995) Distribution of nocturnal forest birds and mammals in north-eastern New South Wales. Relationships with environmental variables and management history. Wildlife Research 22, 359-377.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Lindenmayer D, Taylor C (2020) Extensive recent wildfires demand more stringent protection of critical old growth forest. Pacific Conservation Biology 26, 384-394.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Lindenmayer D, Zylstra P (2024) Identifying and managing disturbance-stimulated flammability in woody ecosystems. Biological Reviews 99, 699-714.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Lindenmayer DB, Cunningham RB, Tanton MT, Smith AP, Nix HA (1990) Habitat requirements of the mountain brushtail possum and the greater glider in the montane ash-type eucalypt forests of the central highlands of Victoria. Australian Wildlife Research 17, 467-478.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Lindenmayer DB, Cunningham RB, McCarthy MA (1999) The conservation of arboreal marsupials in the montane ash forests of the central highlands of Victoria, south-eastern Australia. VIII. Landscape analysis of the occurrence of arboreal marsupials. Biological Conservation 89, 83-92.

| Google Scholar |

Lindenmayer DB, Pope ML, Cunningham RB (2004) Patch use by the greater glider (Petauroides volans) in a fragmented forest ecosystem. II. Characteristics of den trees and preliminary data on den-use patterns. Wildlife Research 31, 569-577.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Lindenmayer DB, Hunter ML, Burton PJ, Gibbons P (2009) Effects of logging on fire regimes in moist forests. Conservation Letters 2, 271-277.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Lindenmayer DB, Wood JT, McBurney L, MacGregor C, Youngentob K, Banks SC (2011a) How to make a common species rare: a case against conservation complacency. Biological Conservation 144(5), 1663-1672.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Lindenmayer DB, Hobbs RJ, Likens GE, Krebs CJ, Banks SC (2011b) Newly discovered landscape traps produce regime shifts in wet forests. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108, 15887-15891.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Lindenmayer DB, Blanchard W, McBurney L, Blair D, Banks S, Likens GE, Franklin JF, Laurance WF, Stein JAR, Gibbons P (2012) Interacting factors driving a major loss of large trees with cavities in a forest ecosystem. PLoS ONE 7, e41864.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Lindenmayer DB, Blanchard W, Blair D, McBurney L, Taylor C, Scheele BC, Westgate MJ, Robinson N, Foster C (2020) The response of arboreal marsupials to long-term changes in forest disturbance. Animal Conservation 24, 246-258.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Lindenmayer D, Taylor C, Blanchard W (2021) Empirical analyses of the factors influencing fire severity in southeastern Australia. Ecosphere 12(8), e03721.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Lindenmayer DB, Bowd EJ, Taylor C, Likens GE (2022a) The interactions among fire, logging, and climate change have sprung a landscape trap in Victoria’s montane ash forests. Plant Ecology 223, 733-749.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Lindenmayer D, Blanchard W, McBurney L, Bowd E, Youngentob K, Marsh K, Taylor C (2022b) Stand age related differences in forest microclimate. Forest Ecology and Management 510, 120101.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ludwig D, Hilborn R, Walters C (1993) Uncertainty, resource exploitation and conservation: lessons from history. Science 260, 17-36.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Manning AD, Fischer J, Lindenmayer DB (2006) Scattered trees are keystone structures–implications for conservation. Biological Conservation 132(3), 311-321.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Martin B (1999) Suppression of dissent in science. Research in Social Problems and Public Policy 7, 105-135 Available at https://www.bmartin.cc/pubs/99rsppp.html.

| Google Scholar |

Mason LD, Bateman PW, Wardell-Johnson GW (2018) The pitfalls of short-range endemism: high vulnerability to ecological and landscape traps. PeerJ 6, e4715.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

McGregor D, Nordberg E, Yoon H-J, Youngentob K, Schwarzkopf L, Krockenberger A (2023) Comparison of home range size, habitat use and the influence of resource variations between two species of greater gliders (Petauroides minor and Petauroides volans). PLoS ONE 18, e0286813.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

McLean CM (2012) The effects of fire regimes and logging on forest stand structure, tree hollows and arboreal marsupials in sclerophyll forests. Unpublished Doctoral thesis. Available at https://ro.uow.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=4850&context=theses [Viewed 22 September 2020]

McLean CM, Bradstock R, Price O, Kavanagh RP (2015) Tree hollows and forest stand structure in Australian warm temperate Eucalyptus forests are adversely affected by logging more than wildfire. Forest Ecology and Management 341, 37-44.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

McLean CM, Kavanagh RP, Penman T, Bradstock R (2018) The threatened status of the hollow dependent arboreal marsupial, the Greater Glider (Petauroides volans), can be explained by impacts from wildfire and selective logging. Forest Ecology and Management 415–416, 19-25.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Meriläinen E, Lehtinen AA (2022) Re-articulating forest politics through “rights to forest” and “rights of forest”. Geoforum 133, 89-100.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Milledge DR, Palmer CL, Nelson JL (1991) Barometers of change: the distribution of large owls and gliders in Mountain Ash forests of the Victorian Central Highlands and their potential as management indicators. In ‘Conservation of Australia’s forest fauna’. (Ed. D Lunney) pp. 55–65. (Royal Zoological Society of New South Wales: Sydney)

Nelson JL, Cherry KA, Porter KW (1996) The effect of edges on the distribution of arboreal marsupials in the ash forests of the Victorian Central Highlands. Australian Forestry 59(4), 189-198.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Noss RF, Lindenmayer DB (2006) Special Section: the ecological effects of salvage logging after natural disturbance. Conservation Biology 20, 946-948.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Nunes FSM, Soares-Filho BS, Oliveira AR, Veloso LVS, Schmitt J, et al. (2024) Lessons from the historical dynamics of environmental law enforcement in the Brazilian Amazon. Scientific Reports 14, 1828.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Price OF, Bradstock RA (2012) The efficacy of fuel treatment in mitigating property loss during wildfires: insights from analysis of the severity of the catastrophic fires in 2009 in Victoria, Australia. Journal of Environmental Management 113, 146-157.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Rees M, Paull DJ, Carthew SM (2007) Factors influencing the distribution of the yellow-bellied glider (Petaurus australis australis) in Victoria, Australia. Wildlife Research 34, 228-233.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Rohmy AM, Hartiwiningsih , Handayani IGAKR (2024) Judicial Mafia and ecological in-justice: obstacles to policy enforcement in Indonesian forest management and protection. Trees, Forests and People 17, 100613.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Sinton DS, Jones JA, Ohmann JL, Swanson FJ (2000) Windthrow disturbance, forest composition, and structure in the Bull Run Basin, Oregon. Ecology 81(9), 2539-2556.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Smith GC, Mathieson M, Hogan L (2007) Home range and habitat use of a low-density population of greater gliders, Petauroides volans (Pseudocheiridae: Marsupialia), in a hollow-limiting environment. Wildlife Research 34, 472-483.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Taylor C, McCarthy MA, Lindenmayer DB (2014) Nonlinear effects of stand age on fire severity. Conservation Letters 7, 355-370.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Tyndale-Biscoe CH, Smith RFC (1969) Studies on the marsupial glider, Schoinobates volans (Kerr): III. Response to habitat destruction. Journal of Animal Ecology 38, 651-659.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Vinson SG, Johnson AP, Mikac KM (2020) Thermal cameras as a survey method for Australian arboreal mammals: a focus on the greater glider. Australian Mammalogy 42, 367-374.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Wardell-Johnson GW, Robinson TP (2023) Considerations in the protection of marsupial gliders and other mature-forest dependent fauna in areas of intensive logging in the tall forests of Victoria, Australia. Pacific Conservation Biology 29, 369-386.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Wardell-Johnson G, Wardell-Johnson A, Schultz B, Dortch J, Robinson T, Collard L, Calver M (2019) The contest for the tall forests of south-western Australia and the discourses of advocates. Pacific Conservation Biology 25, 50-71.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Wardell-Johnson GW, Schultz B, Robinson TP (2024) Framing ecological forestry: applying principles for the restoration of post-production forests. Pacific Conservation Biology 30, PC24033.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Wilson N, Cary GJ, Gibbons P (2018) Relationships between mature trees and fire fuel hazard in Australian forest. International Journal of Wildland Fire 27(5), 353-362.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Wormington KR, Lamb D, McCallum HI, Moloney DJ (2002) Habitat requirements for the conservation of arboreal marsupials in dry sclerophyll forests of southeast Queensland, Australia. Forest Science 48, 217-227.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Youngentob KN, Yoon H-J, Coggan N, Lindenmayer DB (2012) Edge effects influence competition dynamics: a case study of four sympatric arboreal marsupials. Biological Conservation 155, 68-76.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Zylstra P, Wardell-Johnson G (2024) Reply to: Mechanisms by which growth and succession limit the impact of fire in a south-western Australian forested ecosystem – a comment on Zylstra et al.’s model. Functional Ecology 38, 2323-2328.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |