Exploring a new Biocultural Credit Assessment Framework: case study for Indigenous-led fauna management from the Laynhapuy Indigenous Protected Area, Australia

Daniel G. Smuskowitz A * , Emilie J. Ens A , Bridget Campbell

A * , Emilie J. Ens A , Bridget Campbell  A , Bobby M. Wunuŋmurra B , Bandipandi Wunuŋmurra B , Luḻparr George Waṉambi B , Brendan Banygada Wunuŋmurra B , Butjiaŋanybuy Thomas Marrkula B , Darren G. Waṉambi B and

A , Bobby M. Wunuŋmurra B , Bandipandi Wunuŋmurra B , Luḻparr George Waṉambi B , Brendan Banygada Wunuŋmurra B , Butjiaŋanybuy Thomas Marrkula B , Darren G. Waṉambi B and A

B

C

Abstract

This article contains names and/or images of deceased Aboriginal Peoples.

The global biological-diversity crisis has resulted in a widespread uptake of market mechanisms to promote conservation. Despite widespread recognition of Indigenous-led contribution to biodiveristy conservation, market mechanisms are often derived from Western scientific approaches that do not appropriately incorporate Indigenous cultural values and objectives.

This research sought to produce a proof-of-concept case study for a novel ‘Biocultural Credit Assessment Framework’ (BCAF) to facilitate design of an Indigenous-led biocultural conservation project in response to ongoing decline of culturally significant fauna in north-eastern Arnhem Land, Australia. The BCAF is underpinned by Indigenous identification of project dimensions, combining biological and cultural values and aspirations, which could form assessable foundations of a potential Indigenous-led biocultural credit project.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with nine Yolŋu Elders over 2 days. A three-stage thematic analysis using pre-defined coding categories and both latent and semantic level analysis were used to elucidate key components of a biocultural project from Elder responses, including biocultural concerns, actions, targets and indicators.

Yolŋu Elders expressed six key concerns about local fauna, including the following: that some animals were no longer seen; youth were not learning cultural knowledge; invasive-species impacts; reliance on shop food; and Western influences. These concerns were linked to three key targets, including improved cultural transmission, access and use of more bush foods, and seeing ‘species of decline’ again. Ten key indicator groups assessed by a mix of Indigenous and Western methodologies were identified and revolved around biophysical and cultural learning parameters to measure the impact of actions to progress targets. In total, six actions were identified, including spending more time on Country, science-based environmental management strategies and knowledge sharing.

The BCAF elucidated key components of an Indigenous-led biocultural conservation project as identified by Elders. A mix of biophysical and cultural learning indicators assessed both qualitatively and quantitatively could be used to feed into a potential biocultural credit market to enhance project delivery.

Further research is required to progress this conceptual framework with Cultural Advisors and real financial partners to further elucidate challenges, opportunities, and next steps towards an inclusive biocultural market.

Keywords: biocultural credits, biocultural indicators, community-led conservation, conservation finance mechanisms, cross-cultural ecology, cultural ecosystem services, ecosystem accounting, Indigenous-led conservation.

Introduction

Global declines in biodiversity and Indigenous cultures

Rates of vertebrate extinction over the past century, even under the most conservative of estimates, are 100 times greater than those modelled on ‘historical’ conditions (Ceballos et al. 2015; McCallum 2015). This unprecedented decline in biodiversity has been described as ‘biological annihilation’ (Ceballos et al. 2017) and significantly undermines the stability of life on Earth as we know it (McCallum 2015; Woinarski et al. 2015).

This dramatic decline in biodiversity is also evident in Australia, where 11% of the continent’s 273 endemic land mammals have become extinct, with a further 36% being threatened (Woinarski et al. 2015). This loss accounts for 35% of the world’s modern mammal extinctions, making Australia a global exinction hotspot (Woinarski et al. 2015; Garnett et al. 2022). The majority of this loss has occurred over the past 200 years as a result of European colonisation, that continues to reverberate into ‘modern-day Australia’ (Palmer 2010; Grewcock 2018).

The violence embedded in Australia’s colonial history was particularly damaging to Aboriginal Peoples, who endured an often organised, strategic and systematic approach by British colonists to massacre, dilute and assimilate Aboriginal Peoples, practices, worldviews, and languages (Evans 2004; Barney and Mackinlay 2010; Ryan et al. 2022). Despite significant loss and damage to millenia-old cultural knowledge systems, many of Australia’s Aboriginal groups remain dedicated to ensuring these knowledge systems remain alive (Rose 1996; Barney and Mackinlay 2010; Grewcock 2018). Similar colonial impacts on Indigeous Peoples, knowledge and Country have occurred worldwide (Rozzi 2018; Ens et al. 2021). Nevertheless, research has shown that Indigenous Peoples continue to contribute a disproprotional amount to conservation. Although, globally, Indigenous Peoples constitute only 5% of Earth’s population, they are responsible for managing and protecting approximately 40% of the world’s terrestrial protected areas (Garnett et al. 2018). As such, it is becoming increasingly recognised on a global level that it is impossible to protect biodiversity without recognising the importance of Indigenous Peoples and Indigenous knowledge systems in that process (United Nations General Assembly 2007; Bridgewater and Rotherham 2019).

Integrated biocultural approaches to conservation have been touted as the philosophical shift that is needed to include pluralistic cultural values and approaches (Sterling et al. 2017a; Austin et al. 2018; Dacks et al. 2019). Conservation initiatives that ensure that cultural knowledge holders are collaborators from the start, such that indicators, targets and actions are Indigenous-led, meaningful, and accentuate complex biocultural interactions are more likely to support biocultural landscapes and have positive impacts for biocultural conservation (Moorcroft et al. 2012; Ens et al. 2016a; Sterling et al. 2017a, 2017b; DeRoy et al. 2019; Campbell et al. 2022).

Biodiversity credit schemes

The estimated financing gap to reverse biodiversity decline by 2030 is estimated to be between US$598 and US$824 billion per year (Deutz et al. 2020). Biodiversity credit schemes have emerged globally as a market-driven instrument to accelerate the flow of finance towards biodiversity conservation (Biodiversity Credit Alliance 2023a, 2023b; Maron et al. 2024; Wunder et al. 2024). Global biodiversity credit schemes largely fall into two categories, namely, compliance offset schemes and voluntary credit schemes.

Compliance offset schemes, like the one used in the NSW Biodiversity Credit Market, have been used to offset environmental damage by compensating an ecological loss with an ecological gain (BBOP 2018). This mechanism aims to achieve targets of ‘no net loss’ and preferably a ‘net gain’ for biodiversity through legislative requirements, often related to land development, to offset environmental damage (ten Kate and Crowe 2014). Although uptake of biodiversity offset schemes globally has been widespread (OECD 2016), there is still much debate regarding the effectiveness of such schemes and concerns surrounding perverse impacts through accounting mechanisms that fail to tangibly reduce declines of biodiversity, deforestation, loss of critical habitats and extinctions (Bull et al. 2013; Gordon et al. 2015; Maron et al. 2015, 2016; Moreno-Mateos et al. 2015; zu Ermgassen et al. 2019).

Voluntary credit schemes are a newer market tool designed to achieve a positive impact on nature and biodiversity (Biodiversity Credit Alliance 2023a; NatureFinance and Carbone4 2023; Wunder et al. 2024), where a credit represents a measured and evidence-based unit of a positive biodiversity outcome (Biodiversity Credit Alliance 2024). Credits of this nature differ from offsets in that they do not explicitly compensate for an ecological loss, and actively try to differentiate from offsetting practices by incorporating key principles of the mitigation hierarchy to uplift, maintain, and avoid loss of biodiversity (Biodiversity Credit Alliance 2024; Maron et al. 2024). Investment such as this would be driven by investors who purchase credits to progress corporate social responsibility, largely in part as a result of growing stakeholder, shareholder and consumer awareness of biodiversity decline (ICMM and IUCN 2013; ten Kate and Crowe 2014; OECD 2016; Biodiversity Credit Alliance 2023a). Although such voluntary credit schemes attempt to separate from offsetting, an increasing trend of nature-related risk and impact disclosure, such as that outlined in the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures Framework (TNFD 2023), will likely continue to drive demand for nature-positive investment to counterbalance negative impact. As such, investment related to offsetting negative impact within voluntary credit scheme markets remains a risk.

As biodiversity credit markets and their respective accounting standards continue to evolve, discussions on how these mechanisms can deliver practical financial support towards Indigenous land stewards for the significant contribution they make towards biodiversity conservation globally have been of particular importance (Biodiversity Credit Alliance 2023b; World Economic Forum and Deloitte 2023). In Australia, considering that Indigenous Protected Areas (IPAs) comprise over 50% of the National Reserve System (NRS) and are the single largest contributor to Australia’s NRS, followed by National Parks and Nature Reserves (DCCEEW 2022; NIAA 2023), market mechanisms may represent a significant opportunity for IPAs to increase and diversify revenue while progressing biodiversity and cultural conservation (Altman et al. 2007; Hill et al. 2007; Corey et al. 2020).

Despite significant global progress on ecosystem accounting methods (Edens et al. 2022), inclusion of cultural values and Indigenous perspectives into ecosystem accounting frameworks remains elusive (Stoeckl et al. 2021; Normyle et al. 2022a, 2022b, 2023). For example, the establishment of the northern Australia savanna burning carbon-offset methodology has been widely successful in delivering an array of social and economic benefits through the abatement of late dry-season fires and associated carbon emissions (Russell-Smith et al. 2013). Although savanna burning benefits are significant (SVA 2016), this carbon-abatement methodology largely relies on biophysical indicators as the primary mechanism to measure success (Perry et al. 2018). Although the purchase of carbon credits from IPAs (often at a premium) helps progress/support cultural maintenance and/or revitalisation through the funding of programs within the organisation (Hill et al. 2012; Austin et al. 2018; Perry et al. 2018), this remains ad hoc and unrecognised in the accounting mechanism’s identification of value. As such, exploring how Aboriginal cultural values can continue to be included in ecosystem accounting framework design could expand existing accounting mechanisms to better integrate concerns and aspirations of Aboriginal Peoples and possibly lay foundations for new credit mechanisms and expansion of revenue streams for IPAs (Altman et al. 2007; Fitzsimons et al. 2012; Dawson et al. 2021).

Australian IPAs and the potential for biocultural credits

Australia is a world leader in the IPA model that employs biocultural approaches to conservation and management of cultural and biological diversity (Gilligan 2006; Hill 2011; Hill et al. 2011; Moorcroft et al. 2012). Such approaches are underpinned by the recognition of unique place-based interactions between people and the natural environment that create a biocultural landscape where biodiversity and human cultural diversity are inextricably intertwined (Ens et al. 2015, 2016a; Rotherham 2015; Bridgewater and Rotherham 2019). Although IPAs deliver a considerable social return on investment, they are largely dependent on government funding to maintain their commitment to biological and cultural resource management, with little guarantees to ensure long-term financial solvency (ANAO 2011; SVA 2016). Whereas government funding will continue to contribute significantly to the national IPA funding base, increasing access to biodiversity markets could diversify revenue streams and reduce the risk exposure associated with high dependence on government funding (Gilligan 2006; Altman et al. 2007; ANAO 2011).

The application of biocultural conservation in IPAs offers the opportunity to explore a biocultural credit market that recognises the value derived from actions to protect, maintain, and restore biocultural landscapes for the conservation of biological diversity, human cultural diversity, and the inextricable links between them (Bridgewater and Rotherham 2019). The success of northern Australia’s savanna-burning carbon-offset scheme is largely derived from a methodology that effectively measures the abatement of carbon emissions achieved through a reduction in late dry-season wildfires, which is then able to be sold as credits (Russell-Smith et al. 2013). By the same logic, if practitioners can develop a methodology to accurately capture the value created through conservation of biocultural landscapes, a credit underpinned by that value may then become a desired product.

Whilst current demand for credit mechanisms largely orients around carbon abatement driven by both mandatory and voluntary emission reduction targets (akin to offseting), credits that focus on positive-impact investments may suggest an opportunity for an Indigenous-led voluntary biocultural credit market, where government agencies and corporate/philanthropic investors can purchase ‘value-verified’ biocultural credits to progress corporate social responsibility or policy objectives.

Proposed ‘Biocultural Credit Assessment Framework’

A core responsibility of IPA managers is expanding revenue streams to facilitate ongoing operations within the scope of ranger groups to implement management priorities within designated areas. A decade-long collaborative partnership between the Yolŋu Indigenous Yirralka Rangers and Macquarie University researchers prompted conversations about the potential to explore emerging environmental accounting methodologies as an opportunity that may help progress key strategic objectives as outlined by Traditional Owner priorities. This research collaboration therefore aimed to explore how such financial mechanisms, and their respective methodologies, could be implemented in a culturally appropriate way within the IPA.

Materials and methods

Study area

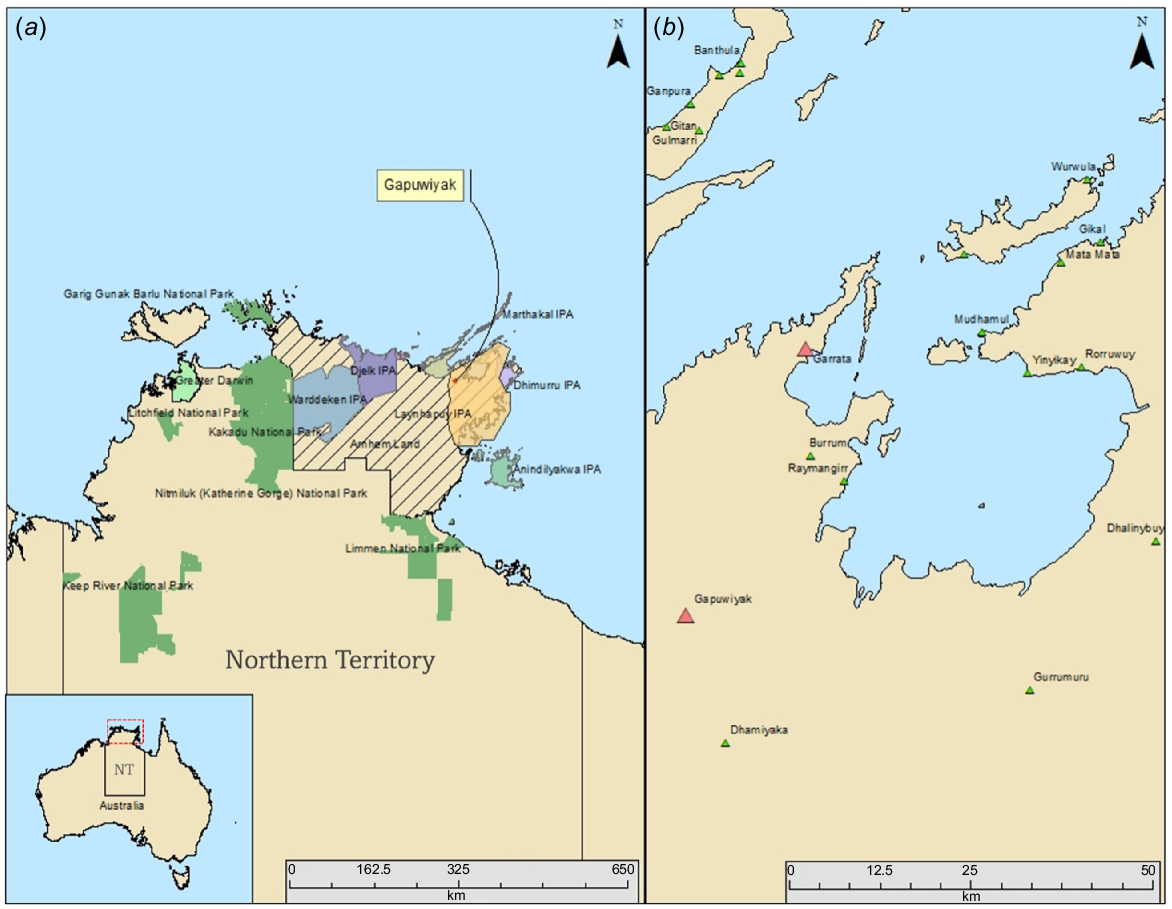

The Laynhapuy IPA covers an area of 17,320 km2 of culturally and biologically important land and sea Country (Fig. 1a). This area is the ancestral estate of the Yolŋu Peoples whose strong, living culture is among some of the oldest on Earth, dating back at least 40,000 years (Wettenhall 2014; LHAC 2017). Within the IPA, there are 32 clans, all of which are connected through complex gurrutu (kinship) relationalities that link individuals, groups, and places to one-another (Wettenhall 2014; LHAC 2017). The Yolŋu matha (language) speaking area of north-eastern Arnhem Land, comprising many dialects, is a stronghold of Australian Indigenous traditional languages (Morphy 2008; AIATSIS 2020). The two primary locations of this investigation were Gapuwiyak and Garrata (Fig. 1b). Gapuwiyak Community is located within the Laynhapuy IPA boundary and is where many study participants and co-authors reside. Garrata is located slightly outside the official IPA boundary, but is a culturally significant site for many co-authors.

(a) Map of the northern end of Northern Territory (Australian Top End), showing location of Laynhapuy Indigenous Protected Area in Arnhem Land (lined region), and other IPAs and National Parks (NPs; green) (b) Distribution of Laynhapuy Homelands within the IPA are indicated by triangles. Red triangles indicate Gapuwiyak (study base) and Garrata (location of fauna survey, located slightly outside of the Laynhapuy IPA boundary).

Collaborative development of the Biocultural Credit Assessment Framework concept

On the basis of earlier expressions of interest in exploring alternative funding streams, Macquarie University researchers engaged in formal, informal, planned and opportunistic discussions with Senior Traditional Owners, Cultural Advisors, rangers and Indigenous community members to explore whether research into financial mechanisms to progress cultural and biological priorities within the IPA was of interest. These discussions are aligned to the Yarning methodologies central to Indigenous research approaches (Hughes and Barlo 2021). Yarning occurred with Senior Traditional Owners at leadership meetings on Country, through informal discussions with rangers at several ranger bases, and opportunistic conversations with Traditional Owners on Country and in community. Traditional Owners often expressed their desire for increasing funding (revenue flow) on Country to help progress Yolŋu biological and cultural conservation priorities, purchase new equipment (often related to vehicles) and increase local employment.

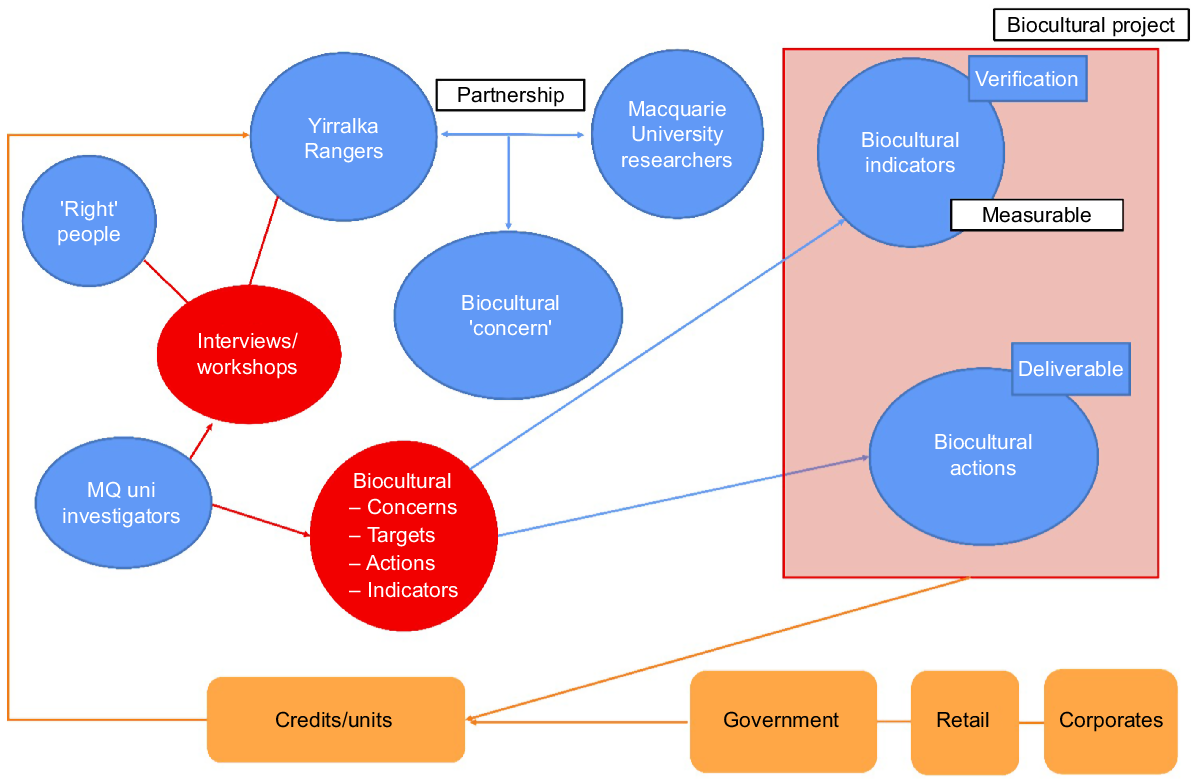

Initial conversations about the present study by the authors centred around how projects could attract funding from external corporations. Noted through these discussions was that investors would likely want to hear dhäwu (stories) about the projects and their impact to justify any investment. Through Yarning, the idea for a Biocultural Credit Assessment Framework (BCAF) evolved (Fig. 2) and key components of a potential framework were suggested by the lead author to be as follows: biocultural concerns, indicators, actions and targets. A research project to explore these components with Yolŋu Elders was developed by the lead author and approved formally by Laynhapuy Indigenous Protected Area managers and by Indigenous Cultural Advisors at key Leadership meetings. The broad research questions and approach (detailed more below) were approved by the Macquarie University Human Research Ethics Committee (project Reference number 5201800178). Free Prior Informed Consent documents were also approved.

The Biocultural Credit Assessment Framework (BCAF)

The concept of the ‘Biocultural Credit Assessment Framework’ (BCAF) (Fig. 2) was collaboratively developed through Yarning between authors. The framework proposes a methodology to elucidate biocultural concerns, actions, targets, and indicators (Table 1) to inform design of Indigenous-led biocultural projects. These measurable dimensions of projects could be used to feed into a biocultural credit market to support financial sustainability of projects. Investors may include governments, retail investors and corporates. Place-based elicitation of the details of these components could occur through semi-structured interviews with local knowledge holders and leaders, in this case Yolŋu ŋalapal (Elders).

| Term | Definition | |

|---|---|---|

| Biocultural project | Refers to a project embedded in a biocultural system that engages with biocultural dimensions (Rotherham 2015; Bridgewater and Rotherham 2019). Project design requires basic elements including concerns, targets, actions and indicators. | |

| Biocultural concern | Participant concern relating to deterioration of a biocultural system or any dimensions that contribute to healthy ecosystem functioning, biodiversity, cultural dimensions, or any combination of these factors (Ens et al. 2016b; Sterling et al. 2017b; Dacks et al. 2019; DeRoy et al. 2019). In this paper, this use of this term relates to concerns in environmental conservation. | |

| Biocultural targets | Desired outcomes or values of importance for participants. Biocultural targets are local, place-based objectives that strengthen or maintain dimensions of biocultural systems (Sterling et al. 2017b; Dacks et al. 2019). Biocultural targets can focus on any dimension of biocultural systems and are likely to have complex and indirect relationships with other variables. | |

| Biocultural actions | Activities or interactions that contribute, either directly or indirectly, to the strengthening of dimensions within biocultural systems. Biocultural actions can be associated with one or more biocultural concerns or targets. | |

| Biocultural indicators | Biocultural indicators are components of biocultural systems, biophysical or cultural, that could be used to measure progress of biocultural actions in progressing biocultural targets. Biocultural indicators should be inclusive of different knowledge systems, aiming to measure the progress of inter-related dimensions that contribute towards a biocultural landscape (Ens et al. 2012; Sterling et al. 2017b; Dacks et al. 2019; DeRoy et al. 2019; Russell et al. 2020). Biocultural indicators promote the use of data that are under-represented in most Western-based environmental management frameworks and may be oral, spiritual, or expressed through lived practice (Ens et al. 2016a; Sterling et al. 2017a; Russell et al. 2020). |

Testing the BCAF: data collection

An existing cross-cultural fauna research project in the Laynhapuy IPA (Campbell et al. 2024) provided the opportunity to explore the efficacy of the BCAF. A 5-day cross-cultural Garrata fauna survey (9–12 May 2022) was run by the Yirralka Rangers and Macquarie University researchers with local ŋalapal and djamarrkuḻi (youth) from the Gapuwiyak School Learning on Country program (see Campbell et al. 2024). Semi-structured interviews (Clarke 2005) were conducted over 2 days (17–19 May 2022) after the Garrata cross-cultural fauna survey with ŋalapal. The interview questions (outlined below) were designed to elucidate local priorities, aspirations, and ideas about biocultural conservation concerns, targets, indicators, and actions. Questioning after an actual field survey for animals was deliberately conducted to capture ŋalapal responses about fauna conservation following direct observation and experiences (or indirect explanation of findings by survey participants) that highlighted the state of local fauna populations at a specific location. Prior to the survey, ŋalapal participants identified fauna species of importance they hoped to see. These data were also used to ascertain Yolŋu priority animals, which is captured in Campbell et al. (2024).

Interview participants were identified using a snowball method (Lewis-Beck et al. 2004; Russell et al. 2020), whereby ŋalapal and the Gapuwiyak-based Yirralka Rangers were consulted to identify the ‘right’ people with cultural authority to speak for that area (as part of the larger cross-cultural fauna research project, (see Campbell et al. 2024). Prior to interviews, participants were introduced to Macquarie University researchers by the Yirralka Rangers, who explained the research project. Ample time was designated to ensuring that participants were aware of the research intent and what their answers were being used for. All participants signed the prior informed consent form before the interviews, were paid for their time (AUD$100/h), and were informed that they could withdraw their responses at any time.

Interview locations were mostly at interviewee’s houses at Gapuwiyak (Fig. 3b); however, some took place at the Gapuwiyak Yirralka Ranger Station (Fig. 3a). The interview process, including translations, took 1 week to complete. The interviews were conducted by the Gapuwiyak-based Yirralka Rangers and Macquarie University researchers who are all authors of this paper (Fig. 3a, b). The interview participants sometimes had family members and children sitting with them (Fig. 3b). A Yirralka Ranger led the interview, first asking the question in English and then translating into Yolŋu matha. Participants mostly answered in Yolŋu matha and this was translated verbally in situ into English by rangers, sometimes with an added conceptual explanation. Interview recordings were transcribed by lead researcher (D. Smuskowitz) and several Yirralka Rangers (co-authors) who added extended explanations and translations of responses as required to facilitate cross-cultural understanding. The rangers were essential facilitators of the transcription process. All interviewees consented to audio recording, and most consented to video. The Gapuwiyak-based Yirralka Rangers were active partners in the interview process, and often were responsible for filming the interviews, which ranged in duration between 56 and 84 min. Notes were taken during the interviews.

(a) Interview with Margaret Waṉambi (second from left) with Bobby Wunuŋmurra (left), Bridget Campbell and Daniel Smuskowitz (right). Photo credit: Brendan Banygada Wunuŋmurra. (b) Interview with Clancy Marrkula (centre), Linda Bandawuŋu, family members, rangers and researchers. Photo credit: Brendan Banygada Wunuŋmurra.

Interview questions

The primary focus of this study was to develop a proof-of-concept for a novel BCAF to facilitate investment in an Indigenous-led biocultural species management project. The semi-structured interview questions were open-ended and used flexibly to allow respondents to recall information they deemed important to the conversation (Taylor and Ussher 2001; Normyle et al. 2022a). Interview questions were designed with analysis and broad application of the model in mind, and to elucidate answers that could inform a Yolŋu Priority Animal list (Campbell et al. 2024) or become assessable dimensions of an Indigenous-led biocultural species management project (Fig. 1, Table 1).

Informed by principles outlined in Braun and Clarke (2006) and Maguire and Delahunt (2017), questions were designed such that responses could be categorised into themes and coded either manually or by using software such as NVivo, while remaining open-ended so that participants could still lead the conversation. Questions were designed knowing that the analysis of participant responses would incorporate a latent level approach where language is understood to convey underlying ideas, assumptions, conceptualisations, and ideologies through recurring patterns of meaning (Braun and Clarke 2006). As such, questions were designed to prompt conversation specifically around how Yolŋu ŋalapal would design a conservation project in response to biocultural concerns. The interview questions were co-designed by researchers and the Yirralka Rangers to achieve this effect and are presented below. Although questions were designed to be translated into Yolŋu matha, they were also designed within a cross-cultural environment to better engage ŋalapal, Indigenous ways of seeing, and cultural dimensions (Rose 1996; Morphy 2008; Hughes and Barlo 2021).

Semi-structured interview questions

Here are photos of the animals we found at Garrata. What do you think/how do you feel about this?

We didn’t find other animals at Garrata, like: wan’kurra (northern brown bandicoot, Isoodon macrourus), djanda (yellow-spotted monitor, Varanus panoptes), biyay (sand ridge goanna, Varanus gouldii) and barkuma (northern quoll, Dasyurus hallucatus). What do you think/how do you feel about this?

Why do you think we didn’t see these animals?

What’s the best way to keep the knowledge about these animals alive?

Why is it important that we see these animals again, or keep seeing these animals?

Do the djamarrkuḻi know this knowledge?

How can we help djamarrkuḻi to learn about animals; for example, what resources would you need to achieve your vision?

What are some activities you want to see on the next survey?

Data management and analysis

Transcripts were read and re-read multiple times by the lead researcher to allow familiarisation, after which deductive (top-down) thematic analysis was used to identify and code participant answers into a coding frame (a priori categories) (Braun and Clarke 2006; Maguire and Delahunt 2017) that identified four main categories that could be fed into a BCAF, namely, biocultural concerns, targets, actions, and indicators. NVivo (ver. 12.3.0; https://lumivero.com/products/nvivo/, Lumivero; Denver, CO, USA) software was used to conduct a thematic analysis of interview transcripts according to the a priori themes, to identify patterns and dominant responses. Responses coded into the a priori thematic coding frame were not necessarily entire responses to a question, but rather key words, sentences, or phrases that aligned with definitions provided in Table 1. Coding of responses was not mutually exclusive, and responses could be assigned to multiple categories.

Within each category, responses were then coded again to identify themes that emerged through recurring patterns and stories by utilising a data-driven open coding or an inductive/bottom-up approach (Braun and Clarke 2006; Althor et al. 2018). Themes identified here are at the semantic level, whereby responses were coded into distinctive dimensions of categories at face value (or surface-level meaning) and did not require analysis into the underlying meaning behind responses beyond what participants explicitly stated (Boyatzis 1998; Braun and Clarke 2006). Responses within these themes were then coded again to identify subthemes at the latent level, where responses were interpreted and theorised to elicit the underlying assumptions, values and conceptualisations that underpin and give meaning to participant responses (Braun and Clarke 2006). All coded responses were checked with the rangers to ensure that proper meanings were elicited from responses and to ensure that Traditional Owners’ perspectives were maintained and recorded appropriately.

Results

Interviewees: ŋalapal (Elders, Indigenous knowledge holders)

Interviews with ŋalapal were conducted in five groups, including a total of four miyalk (women) and five dirramu (men) (Table 2). Interviewees represented the two cultural moieties of the region (Yirritja and Dhuwa) from eight different Homelands and five clan groups (Table 2). A total of six rangers contributed to the interview process on a rotating basis.

| Name (yäku) | Moiety | Homeland (Yirralka) | Clan group (Bäpurru) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mr T Biḏiŋal | Y | Gale | Ritharrŋu | |

| Munuŋgu Dick Ŋurruwuthun | Y | Rurraŋala | Dhä-wupa Gumatj | |

| Guthitjipuy Clancy Marrkula | Y | Gapuwiyak | Gupapuyŋu | |

| Linda Bandawuŋu | Dh | Bunhaŋura | Djambarrpuyu | |

| Jimmy Marrkula | Y | Gapuwiyak | Gupapuyŋu | |

| Helen Djaypila Guyula | Dh | Gurthaŋur | Djambarrpuyŋu | |

| Marrarrawuy Margaret Waṉambi | Dh | Raymaŋgirr | Marraŋu | |

| Muwarra Davis Marrawuŋu | Dh | Dhuwalkitj | Djambarrpuyŋu | |

| Julie Yunupiŋu | Y | Gumatj Homeland | Dhä-wupa Gumatj |

Y, Yirritja; Dh, Dhuwa.

Interview response themes

Through deductive thematic analysis, at least one response from every participant contributed to each a priori coding-frame category (Table 3). One new category emerged from the responses, namely, ‘place-based barriers’. This category included all responses that did not fit into an existing category but had a common theme. Technical difficulties resulted in one interviewee’s (Margaret Waṉambi) audio not being recorded, which may have resulted in fewer responses and coded data points (Table 3). In total, 236 responses were coded. ‘Biocultural actions’ was the most frequently mentioned category, followed by concerns, targets, indicators, and place-based barriers. In total, 15 themes were identified within the coding-frame (and added) categories, with seven subthemes identified from further analysis (Table 4).

| Participant group | Biocultural category | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concerns | Indicators | Targets | Actions | Place-based barriers | |||

| G. C. Marrkula L. Bandawuŋu | 17 | 14 | 4 | 16 | 1 | 52 | |

| J. Marrkula H. D. Guyula | 12 | 8 | 8 | 19 | 1 | 48 | |

| J. Yunupiŋu M. D. Marrawauŋu | 18 | 8 | 18 | 33 | 5 | 82 | |

| M. Waṉambi A | 2 | 1 | 4 | 7 | 1 | 15 | |

| T. Biḏiŋal M. D. Ŋurruwuthun | 6 | 10 | 10 | 11 | 2 | 39 | |

| Total | 55 | 41 | 44 | 86 | 10 | 236 | |

| Category | Theme | Subtheme | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biocultural concern | C1 | Changing landscapes | |||

| C2 | Children not learning (cultural) knowledge | ||||

| C3 | Invasive species | ||||

| C4 | Not seeing certain animals | ||||

| C5 | Reliance on shop food | ||||

| C6 | Western influences | ||||

| Biocultural target | T1 | More bush-food consumption | |||

| T2 | See species of decline again | ||||

| T3 | Cultural transmission | T3.1 | Children equipped with (cultural) knowledge | ||

| T3.2 | Children to experience what elders experienced | ||||

| T3.3 | Children using knowledge | ||||

| T3.4 | Intergenerational transfer of knowledge | ||||

| Biocultural action | A1 | Management | |||

| A2 | Right knowledge for right time | ||||

| A3 | Dhäwu (stories) and manikay (songlines) | ||||

| A4 | More time on Country | A4.1 | Hunting, bush foods and naming | ||

| A4.2 | Walking | ||||

| A4.3 | Camping | ||||

| Biocultural indicator | B1 | Biophysical | B1.1 | Presence of hollow logs | |

| B1.2 | Presence of priority species | ||||

| B1.3 | Lifecycle stages of priority species (fauna and flora) | ||||

| B1.4 | Presence of feral species | ||||

| B1.5 | Historical landscape structure and ecosystem health | ||||

| C1 | Cultural learning | C1.1 | Seeing animals of decline again | ||

| C1.2 | Learning | ||||

| C1.3 | Knowledge use | ||||

| C1.4 | Time spent on Country | ||||

| C1.5 | Cultural knowledge | ||||

Biocultural concerns

Six key biocultural concerns arose in the interviews (Table 4). The most common concern was that certain animals were no longer being seen or were being seen less. Several comments referred to the importance of animals as a food source, maintaining connections between culture and their ancestors, and integral to identity and sense of their wellbeing. As Guthitjipuy Clancy Marrkula and Linda Bandawuŋu stated:

Seeing those animals helps us do that [teach our children], makes us proud, animals still there, good to look at those animals, makes us happy and proud. Those animals are part of our identity. Our old people want to see that again, what they were looking at before. Helps to remember all those manikay [songlines]. We see the animals and help us to remember olden days and those old people.

Several participants mentioned that they were not seeing goannas as frequently. Goannas were mentioned most frequently as animals of concern (n = 21), followed by kangaroos (n = 5), bandicoots (n = 3) and there were single mentions about freshwater turtle, quoll, emu, marbled velvet gecko, possums, wallabies, snakes, and the blue tongue lizard.

We aren’t seeing those animals, so we aren’t happy, it’s sad, makes us want to cry. We cry for those animals. We feel bad that we can’t find that animal anymore. If we see animals that we haven’t seen in a long time, we might cry for them, to see them again makes us happy. (Linda Bandawuŋu)

Invasive species were also raised as a key concern, especially the impact on fauna and degradation of landscapes. Cane toads (Rhinella marina) were mentioned most frequently (n = 7), followed by swamp buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) (n = 4), pigs (Sus scrofa) (n = 4), and cats (Felis catus) (n = 1). Several participants raised concerns about changing landscapes, including the impacts of climate change and Western influences that have (indirectly) encouraged Yolŋu movement away from outstations into townships, which subsequently had a biophysical impact on the environment.

We used to walk in that area, and used to see lots of those animals there, wan’kurra [northern brown bandicoot, Isoodon macrourus]. Maybe 40 or 50 years ago... wan’kurra, barkuma [northern quoll, Dasyurus hallucatus], djanda [goannas]. Until the cane toads arrived. (Dick Ŋurruwuthun)

Long time ago, people used to go camp to camp, for different seasons, the land was kept healthy, strong, but now it’s changed. (Clancy Marrkula)

Participants all expressed concern that djamarrkuḻi were not learning cultural knowledge and were being neglected of the (cultural) experiences afforded to their generation, largely as a result of the decline of significant species, and Western influences such as sedentary lives in town and too much time on mobile phones. They stated that this was also resulting in a disconnect between emerging generations. Participants suggested that Western influences affected transmission of cultural knowledge, due to increased use of motor vehicles, as walking historically was an integral dimension of seeing and learning about animals. As Julie Yunupiŋu and Davis Marrawuŋu stated:

The children aren’t seeing the things that we saw long time, and that worries me. This is what we experienced, walking, story for goanna, seeing goanna walking, camping, what food they used to eat, where they used to stop and camp the names of the crossings, the creeks. (Julie Yunupiŋu)

Country isn’t changing, but the children are changing, and the technology is changing and things are becoming modern, out of balance. (Muwarra Davis Marrawuŋu)

Three of five respondents raised concerns about the excessive consumption of sugar and reliance on the local grocery store for food. Respondents noted that hunting and collecting bush foods composed a much larger proportion of the average day, prior to the establishment of shops, and the importance of bush foods for a healthy diet. Helen Djaypila Guyula stated: ‘This is the right season [for certain bush foods], but now Yolŋu people are just sitting here watching the shop waiting for it to open.’

Biocultural targets

Thematic analysis identified three key biocultural targets, namely, cultural transmission, more consumption of bush foods, and seeing ‘species of decline’ again. Cultural transmission had the highest number of participant response codings (n = 31), followed by seeing ‘species of decline’ again (n = 9), and more reliance on bush foods (n = 4). Several participants highlighted the importance of bush foods in diets for health reasons, suggesting that there was too much reliance on food sourced from the local shop and this should be supplemented with more bush foods.

Eating own tucker [food] is good for your diet, and eating more sugar is not good. (Julie Yunupiŋu)

It would be good if these animals could come back again, so we could get the kids to come back again. (T Biḏiŋal)

Participants continued to highlight their desire to see ‘animals of decline’ again, citing key dimensions of their Indigenous knowledge system that were dependent on the presence of these animals. Responses categorised under biocultural concerns were commonly coded biocultural targets.

We like seeing the pictures, but we want to see those animals coming back properly. We want to see them again, for eating, for cultural reasons its important. (T Biḏiŋal)

We see the animals and help us to remember olden days and those old people. (Jimmy Marrkula)

The cultural transmission target included the following four foci: desire for djamarrkuḻi to be equipped with cultural knowledge; djamarrkuḻi to have the opportunity for similar experiences participants had; djamarrkuḻi using knowledge; and intergenerational transfer of knowledge (Table 4).

Although djamarrkuḻi being equipped with cultural knowledge was similar to djamarrkuḻi using knowledge, most participants made comments suggesting that teaching the djamarrkuḻi was the main priority and did not extend to directly mention the use of that knowledge by them. However, some responses did explicitly state a desire that djamarrkuḻi would then begin to ‘use’ this knowledge in their lives. For this reason, a distinction was made among these targets.

Several participants alluded to a desire for djamarrkuḻi to be afforded the opportunity to experience what they experienced when they were growing up, such as more time in the bush. Other comments explicitly mentioned a desire to continue traditions and the sharing of knowledge for the next generation.

We want to pass the knowledge on to the kids. Seeing the flowers... then we know it’s the right time to get the catfish. Yolŋu way of seeing things. We know the right time... need to show them this. (Dick Ŋurruwuthun)

Yolŋu has been living and teaching his grandchildren on and on, and maybe his grandchildren grow up and they keep teaching. That’s why it is important to see these animals, keep living through that. That’s why we keep teaching all the kids for wayin [meats], manikay [storyline], buŋgul [ceremony], how to make a canoe. (Jimmy Marrkula)

Biocultural actions

The majority of coded participant responses were included under the biocultural-actions category (Table 4), with another four subthemes that emerged from deeper analysis.

The most common action identified was spending time on Country (Action no. 4), which was subdivided into three subthemes, including the following: hunting, bush foods and naming; walking; and camping. Four of five participants mentioned the significance of walking in engaging with Country, either through their past experiences or the need for more walking activities today. Several participants mentioned that walking would be a good way to teach djamarrkuḻi. Camping was also mentioned in several responses, highlighting the importance camping played prior to modern influences for keeping Country healthy, and also as an immersion activity that would be a good way to teach djamarrkuḻi important knowledge.

Yolŋu used to keep the Country healthy. They used to stay there for a week and move to other place, and then keep on continuing. (Guthitjipuy Clancy Marrkula)

Suggestions for spending more time on Country were mostly related to important concepts that djamarrkuḻi should be learning. These included methods of hunting, collecting bush foods, the right naming and moieties (Dhuwa/Yirritja) for plants and animals, showing kids how to cook and eat certain animals, the names for certain parts of the animals, how to find those animals, gendered cultural roles for dirramu (men) and miyalk (women), tracking animals, and general learning about Country.

We need to show the djamarrkuḻi how to eat those animals because today children are growing up they can’t see those animals like possum, bandicoot, echidna, blue tongue lizard, goanna. (Guthitjipuy Clancy Marrkula)

I say to my grandson, watch what your grandfather does, watch the right way to cut that animal up. (Linda Bandawuŋu)

Some participants made specific mention of actions that involved an environmental management activity to intervene in a changing landscape. Several respondents mentioned breeding animals as a potential management strategy, to help bring those animals back to Country. Cultural burning as a form of environmental management was a strong recurring theme, an important action needed to ensure appropriate fire regimes and contribute towards healthy landscape structure. Responses from Julie and Davis included suggestions for ecosystem ‘cleaning’ or engineering to keep a backfilled water hole open as a water source for both people and animals. These participant groups mentioned desires to continue doing fauna surveys to learn more about the distribution of animals on Country and taking steps towards protecting them.

If we find a male and female animal, maybe we can grab them and put them somewhere to breed and send those little ones back to Country. (Mawarra Davis Marrawuŋu)

All participants made specific mention of knowledge-sharing activities and actions that involved the right knowledge for the right season. Knowledge holders made clear that they knew what knowledge should be shared at specific seasonal times of the year. Comments often included biocultural indicators such as the flowering of certain trees or the start of the rainy season. For example, Margaret Waṉambi stated:

Next time we should go when the grass is burnt, we can track them better, for bandicoot, snake. This is right time.

All participants specifically mentioned the importance of sharing dhäwu (stories), manikay (songlines) and buŋgul (dances) with younger generations and were usually related to animals that they were interested in seeing again.

Biocultural indicators

In total, 10 indicator groups were identified and categorised as either biophysical (n = 5) or related to cultural learning (n = 5), and sometimes included several individual indicators for each group (Table 4). Responses were coded into the cultural learning theme much more (n = 24) than they were into the biophysical theme (n = 13); however, the responses were not mutually exclusive among groups. Biophysical characteristics of the environment that were noted as important for cultural knowledge included hollow logs, animal tracks, presence of animals, presence of burrows, and flowering of plants. Biophysical indicators that were deemed negative related to the presence of damage from buffalo and pigs, overgrowth of grass, dense trees, missing water sources, and bad soil.

Cultural-learning indicators mentioned by the knowledge holders included the following: djamarrkuḻi knowing the right names for things; when to go out and collect certain bush foods; when the right time for certain hunting is; the names of animal parts; how to cook animals; dances; stories; and songlines.

Place-based barriers

Many participants noted challenges and inadequate resourcing to go on Country. One of the participants had health problems, and as such mentioned that it was a challenge to get out. Resources noted as essential for accessing Country included funding, cars, and boats. Participants expressed the importance of facilitating nalapal to go on Country, which would require amenities and provisions for shade, power (generators), a shower, toilet, and adequate roads. Many participants mentioned that they did not have a working vehicle, which was a barrier to accessing remote Country.

Mapping biocultural concerns against targets, indicators, and actions to guide management

By organising actions, indicators and targets that address dimensions of each biocultural concern, a matrix was produced that could inform a potential biocultural conservation project within the Laynhapuy IPA that meaningfully engages with local Indigenous priorities. In Table 5, we present a breakdown of targets, indicators, and actions that addressed each biocultural concern, that with further research could be greatly expanded on. Table 6 depicts indicators sorted by category and includes an assessment method for each indicator to contribute towards assessments and reporting of proposed actions.

| Biocultural concern | Biocultural indicator | Biocultural target | Biocultural action | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Changing landscapes | B1.1-B1.5 | T2, T3.2 | A1 | |

| Children not learning (cultural) knowledge | C1.1-C1.5 | T3.1–3.4 | A2, A3, A4.1–4.3 | |

| Invasive species | B1.1, B1.4 | T2, T3.2 | A1 | |

| Not seeing certain animals | B1.2, C1.1, C1.3 | T2, T3.2 | A1, A4.1–4.3 | |

| Over-reliance on shop food | C1.2-C1.4 | T1, T3.1–T3.4 | A2, A4.1–4.3 | |

| Western influences | C1.2-C1.5 | T1, T3.1–3.4 | A3, A4.1–4.3 |

| Type | ID | Indicator | Assessment | Positive/Negative | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biophysical | B1.1 | Hollow logs | Surveys | Positive | |

| B1.2 | Presence of priority species, including signs of inhabitation (burrows etc.) | Surveys, camera traps | Positive | ||

| B1.3 | Lifecyle stages of priority species (eggs, flowering of planets etc.) | Surveys | Positive | ||

| B1.4 | Presence of feral animals, including indicators of presence, i.e. tracks | Surveys, visual assessment | Negative | ||

| B1.5 | Historical landscape structure and ecosystem health – Inappropriate fire regimes – Grass growth too high – Too many trees – Presence of freshwater springs | Visual assessment (Elders) | Negative | ||

| Cultural learning | C1.1 | Seeing animals of decline – Specific animals relating to cultural values (totems etc.) | Surveys, camera traps | Positive | |

| C1.2 | Learning – Eating bush tucker (food) – Teaching kids to eat right way – Traditional hunting methods – Eating right food for right season | On Country camps, interviews with Elders, Elder facilitated assessment of children’s learning | Positive | ||

| C1.3 | Knowledge use – Hunting for bush food – Collecting right food for right season – Traditional cooking methods revitalised or learnt – Children know how to do by themselves | On Country camps, interviews with Elders, Elder facilitated assessment of children’s learning | Positive | ||

| C1.4 | Time spent on Country (specific areas) | Interviews with Elders, quantitative assessment | Positive | ||

| C1.5 | Cultural knowledge – Indigenous ecological knowledge (i.e. naming of plants, animals, wind direction etc.) – Dances, songlines, stories, art – Cultural law – Burning of Country – Naming of places | On Country camps, interviews with Elders, Elder facilitated assessment of children’s learning | Positive |

Proposed assessments included qualitative and quantitative methods and integrated both Western and Indigenous knowledge systems that could be reported using a traffic-light system 'scorecard’. Ŋalapal strongly asserted that they are capable of assessing cultural learning indicators. On-Country camps with ŋalapal and youth are both an action to address biocultural concerns (can be reported quantitatively as a biocultural indicator) and provide a medium to assess a number of indicators and, as such, are included in ‘assessment methodology’. Table 6 supplements Table 5, providing greater depth of indicator groups and includes elements Elders noted as important. Indicators here do not extend towards Western data-driven measurements of ecosystem health, but rather biocultural indicators that measure success of actions from the perspective of ŋalapal. Further exploration of this method could produce a standard methodology for summarising indicators to give an overall scorecard.

Discussion

The present paper has highlighted that through the use of simple semi-structured interviews, Indigenous knowledge holders elucidated cultural and biophysical concerns that translated to clearly identifiable targets, measurable indicators, and practical actions. Although only nine ŋalapal were interviewed, there was a high degree of congruence across responses. Responses were highly relational and often centred around interactions between biological values and cultural values, and the importance of maintaining these interactions across generations to ensure that Indigenous cultural knowledges, practices, and languages remain strong.

This practical proof-of-concept case study advances the literature and methodology on development of a transparent and robust framework that helps clearly communicate Traditional Owner priorities and concerns to a broader audience (ten Kate and Crowe 2014; Austin et al. 2018; Dacks et al. 2019; Deroy et al. 2019; Stoeckl et al. 2021; Normyle et al. 2022b, 2023). While demonstrating the ability to address placed-based criteria, the framework structures the dimensions of proposed projects into measurable targets, actions, and indicators, which could offer a practical tool for IPA managers and ranger programs to monitor success internally, guide their own adaptive management, and report back to their community and Elders. The framework delivers a transferable, measurable, and repeatable methodology that could be used to lay the foundations for Yolŋu decision makers to further explore the potential of a measurable biocultural credit market that has largely been conceptual and theoretical (Fitzsimons et al. 2012; Stoeckl et al. 2021; Normyle et al. 2023).

The Biocultural Credit Accounting Framework (BCAF)

The proposed BCAF is founded on simple identification of community-based ‘bottom-up’ priorities that can inform broader top-down assessments. The a priori ‘coding-frame’ categories would be fixed across projects and offer a structured methodology (top-down) that has the benefit of being transferable and repeatable across a wide range of contexts, while still including a ‘bottom-up’ community-driven analysis that can allow contextualisation and place-based themes, perspectives and values to emerge as the core content (Braun and Clarke 2006; Hill et al. 2012; DeRoy et al. 2019). This simple, workable, repeatable model could be adopted by other organisations or groups, preferably Indigenous-led, to develop (or complement existing) locally meaningful biocultural conservation projects without compromising the importance of place-based values and design (Hill 2011; Hill et al. 2012; Ens et al. 2016a; Dacks et al. 2019; Woodward et al. 2020).

Furthermore, the inductive and deductive approaches characteristic of this model were complementary, allowing enough structure to organise responses, so that locally meaningful themes and subthemes could emerge. Following the emergence of a new category, ‘place-based barriers’, to address context-specific challenges such as access to cars and boats, the BCAF was reconfigured to add an extra dimension that could act as an intermediary to manage resources. The creation of the ‘place-based barriers’ category further highlights the potential for this methodology to incorporate context-specific components and ensure that local place-based dimensions are a key component of the project.

Biocultural conservation projects

The bottom-up approach utilised here elucidated project dimensions that reflected local biocultural value systems and identified practical actions that could be followed up to protect biophysical and cultural areas of concern. In this study, the desires of ŋalapal often related to the transfer of knowledge to djamarrkuḻi, a process requiring the ‘right people’, at the ‘right place’ and at the ‘right time’ to achieve ‘right way’ project design (Woodward et al. 2020) that meaningfully contributes towards local cultural values. Participant responses also highlighted an eagerness to work collaboratively with external institutions and scientists to amplify impacts, adding expertise that could be used to complement Yolŋu knowledge systems and local priorities. Projects could be paired with fauna/environmental research and a management plan that includes Western scientific knowledge to maximise opportunity for synergies and impact to produce outputs that could be valued by both Indigenous and Western systems (Hill 2011; Hill et al. 2012; Moorcroft et al. 2012; DeRoy et al. 2019; Sloane et al. 2019; Russell et al. 2020; Dawson et al. 2021; Campbell et al. 2024).

Biocultural projects aim to conserve the strength and diversity of interactions between human cultural components and biological diversity, thereby conserving the ecological richness that biocultural landscapes support (Ens et al. 2012; Bridgewater and Rotherham 2019; Dacks et al. 2019). The conservation of unique interactions between Yolŋu and their Country were identified in this study as key priorities of ŋalapal, necessitating the need for biocultural project designs that aim to strengthen as many dimensions of biocultural landscapes as possible, given resourcing constraints. The actions, targets, and indicators identified through thematic analysis could inform project design, as illustrated in Table 5. If locally desired, projects could be expanded to include other targets, actions, and indicators as identified by Western scientific practitioners, to synergise different knowledge systems and deliver greater benefits for biocultural landscapes.

Biocultural indicators, measuring cultural learning

The Yolŋu indicators fell into two categories, namely, biophysical and cultural learning. Biophysical indicators were identified as culturally important components of the ecosystem such as hollow logs and animal tracks. One participant mentioned the excessive growth of grass, which was likely to be due to altered fire regimes, akin to the fuel-load measurements of the savanna-burning carbon-market methodology (Russell-Smith et al. 2013). Respondents identified that the presence or tracks of invasive species such as buffalo and pig could also be used as a biophysical indicator, as has been noted and used in other studies of the study region (Ens et al. 2016b; Sloane et al. 2019).

Respondents discussed a wide array of cultural learning indicators as dimensions of locally important biocultural systems that would indicate progress towards biocultural targets. Whereas Western systems of environmental management orient around the explicit use of quantitative indicators for monitoring and evaluation, Indigenous knowledge systems are often oral, non-linear, and expressed through lived practice (Rose 1996; Ens et al. 2016a; Sterling et al. 2017b; Russell et al. 2020). If Western frameworks are to better engage with Indigenous knowledge systems, narrow views of data that exclude different knowledge systems need to be reconsidered, such that project designs can adequately meet the needs of stakeholders while ensuring that biocultural systems are not dismantled (Hill et al. 2011; Ens et al. 2016a; Sterling et al. 2017a; Austin et al. 2018; Campbell et al. 2022). As such, the use of qualitative indicators has been suggested as a culturally appropriate mechanism for including cultural knowledge into a monitoring system (NIAA 2015a, 2015b; Sterling et al. 2017a, 2017b; Dacks et al. 2019). Other frameworks such as the ‘Most Significant Change Technique’ offer the possibility to use stories of significant change to qualitatively monitor and evaluate project performance (Serrat 2017).

Normyle et al. (2022a) suggested the use of opening and closing stock for biocultural landscapes, measuring net change in qualitative terms through the use of a traffic-light reporting system. Qualitative monitoring approaches may be more meaningful when working in cross-cultural systems, such as between investors and Indigenous communities, to bridge different knowledge systems rather than attempting to homogenise ‘ways of doing’ into numerical indices (Sterling et al. 2017a, 2017b; DeRoy et al. 2019; Normyle et al. 2022b). A mix of storytelling reporting, and the use of biophysical indicators, which may also include Western scientific metrics, may adequately support reporting requirements for biocultural projects. Table 6 outlines a potential mixed-methods approach to assessing impact via biocultural indicators as identified by ŋalapal. The indicator groups use a mix of Western scientific approaches and qualitative assessment approaches that could be facilitated by Indigenous Elders and on-Country camps with youth, to produce a traffic-light scorecard. Further research exploring how data-driven assessment methods could be integrated into monitoring and reporting of environmental impact could maximise synergies between Western and Indigenous knowledge systems and perspectives.

Biocultural credit market

Biocultural projects offer an opportunity to capitalise on existing market-derived frameworks to close funding gaps and promote financial sustainability for Indigenous-led place-based projects. The value created could be fed into a biocultural accounting credit scheme, wherein investors are able to purchase credits (and the rights to claim that they have supported the value generated) through these projects, backed by qualitative and quantitative indicators of impact. Credits could be issued on a yearly basis, such that purchase of credits could contribute to private investor corporate social-responsibility objectives or government agencies exploring different mechanisms to fund conservation (OECD 2016; Deutz et al. 2020; Biodiversity Credit Alliance 2023a; NatureFinance and Carbone4 2023; Wunder et al. 2024). Recent reports have highlighted that voluntary carbon offsetting is growing at a substantial rate and exhibit an appetite for schemes that can promote environmental objectives (Ecosystem Marketplace 2013; Ecosystem Marketplace 2019; Biodiversity Credit Alliance 2023a). The framework represents a clear standardised process for transparent, data-informed and verified evaluation of projects and could be enough to satisfy investor sentiment of value delivered (NatureFinance and Carbone4 2023; Biodiversity Credit Alliance 2023b; Wunder et al. 2024)

Although there exists potential for development of a biocultural credit market to support Indigenous-led biocultural projects in Australia and globally, more work is needed to identify and explore the risks associated with such a market. This exploration requires extensive consultations with Indigenous counterparts. There is currently a wide range of views held in many communities, globally, on the desirability of the commodification of nature, and especially culturally significant values, and the risks this might entail in the context of the approach being explored (Bull et al. 2013; Gordon et al. 2015; Maron et al. 2015, 2016; Moreno-Mateos et al. 2015; Perry et al. 2018; zu Ermgassen et al. 2019; Govind et al. 2024).

One area of concern is around the potential use of any credit mechanism to counterbalance negative impact elsewhere, and whether this would be (culturally) acceptable to Traditional Owners. Furthermore, more work needs to be undertaken to explore whether Traditional Owners are aware of, and would be comfortable with, investors who would want to make claims about the benefits, potentially including claims that the benefits counterbalance negative impacts elsewhere, and that once sold, the right to claim those benefits moves to the buyer.

Conversations around full potential implications of market involvement were not discussed in detail with interviewees at this stage, given the scope of the project and uncertainty involved in what a potential biocultural market in Australia would look like. It is likely that to fully explore this area, conversations would be multi-staged, such that there is sufficient conceptual development of the framework to ensure it meets minimum cultural and ethical values as identified by Indigenous counterparts through an incremental co-design process (Quigley et al. 2021; Butler et al. 2022). As such, this study, and the conversations, consultations, and consent components of it, are the first small step in what is likely a much longer journey should Yolŋu decision makers wish to pursue marketing and selling biocultural credits.

Data sovereignty and Indigenous cultural and intellectual property

Data sovereignty and Indigenous cultural and intellectual property (ICIP) are critical to the development of any framework, especially when working with Indigenous knowledge systems (Kukutai and Taylor 2016; Gualinga et al. 2023). Decolonising data-collection systems requires cross-cultural collaborations beyond ‘surface-level’ engagement to enhance self-determination in decision-making, participation, and capacity building (United Nations General Assembly 2007; Davis 2016; Smith 2016; National Environmental Science Program 2018). Core to this is ensuring that Indigenous stakeholders maintain full ownership and authority over the collection, storage, analysis, use, and re-use of data such that cultural knowledge is accessible at all times within their respective Indigenous organisations (Davis 2016; Carroll et al. 2019; Hudson et al. 2023). The collective benefit, authority to control, responsibility, and ethics (CARE) principles, developed in collaboration with several Indigenous groups in relation to culturally informed Indigenous data governance (Carroll et al. 2019, 2020, 2021), demonstrate the importance of ensuring equity within Indigenous data-collection and -use paradigms.

Building respectful research partnerships and outcomes

As with many Indigenous community-based research projects, in-person and place-based collaboration that facilitates formation of trusting relationships is highly desired by local communities (Ens et al. 2012; Dacks et al. 2019; DeRoy et al. 2019; Woodward et al. 2020). Although we noted in the Materials and methods section the time taken to conduct the interviews, prior engagement, planning, and development of trusting relationships (which can vary significantly depending on the group) were not captured explicitly in the timeframe reported. Respectful community engagement and research requires active effort to co-design and co-deliver research, disseminate updates, and provide opportunity for feedback (Hill 2011; Hill et al. 2012; Woodward et al. 2020; Cooke et al. 2022). The lead researcher lived in the community for 3 months, where data sharing was undertaken opportunistically and in person. By immersing research and researchers in communities, trust, relationship building, and cross-cultural learning can be significantly enhanced, leading to more meaningful and equitable outcomes (Sloane et al. 2019; Hughes and Barlo 2021). External researchers can deepen relationships with community members by attending ceremonies, hunting, and helping the community and individuals with tasks when required. Such reciprocity can provide opportunities to further explain conceptual details of the research, disseminate results, and allow for casual feedback to inform the research process. In this study, results were shared with Traditional Owners at all stages of the interview process. Answers were checked by rangers to ensure that correct transcription took place, and that proper meanings of answers were embodied in the transcription. These interactions can be the most rewarding part of the research process.

Limitations and future directions

First, it must be recognised that pursuit of any biocultural credit project depends on the Yirralka Rangers and the Yolŋu Traditional Owners of the Laynhapuy IPA. This was a pilot study to explore the possibility of such a scheme, where the intent was to help explore an area of interest to the Yirralka Rangers and IPA managers. Although this study presents a possible new opportunity to enhance financing opportunities for remote Indigenous land and sea management, it is recognised that there is need for further consultation with Indigenous counterparts to explain and discuss the framework presented here to identify whether they are interested in continuing this research. Pursuit of the concept by the Yirralka Rangers will require conversations within established Yolŋu governance structures, exploring key aspirations, expectations, questions, and concerns of interested community members, rangers and ŋalapal. Although there are many reasonable concerns surrounding unitised cultural-biodiversity credits (Perry et al. 2018; Govind et al. 2024), it is possible to view such mechanisms, at least on a small scale, as funding for Indigenous-led projects that are packaged in a way that also is attractive and understandable to Western mechanisms.

Although this study demonstrated promising potential, there was a limited number of survey participants over 2 days of interviews and a focus on a single geographical area. Therefore, the results cannot be reliably extrapolated to a larger scale; more interviews are required. However, this investigation did successfully demonstrate a proof-of-concept that the proposed novel ‘BCAF’ can elucidate key practical components of a biocultural project that could feed into a biocultural credit market. Furthermore, the model reaffirmed that ŋalapal and Indigenous Rangers are interested in designing their own biocultural conservation projects, such that targets, actions, and indicators are place-based and locally meaningful.

It is important to recognise that this investigation had an element of author bias. The three-tiered thematic analysis helped maximise participant perspectives; however, the author was required to decipher the themes, stories, and meaning in the responses. We suggest that this may be an essential part of the process, as these concepts exist at an existential frontier and cannot be discussed without some form of human interpretation, thus reinforcing the need for collaboration at every step of the process to ensure Indigenous perspectives are being accurately included and portrayed.

Although the design of questions were developed so as to best translate linguistically, they were also designed to engage and interact more meaningfully with Indigenous ways of seeing in a cross-cultural setting (Rose 1996; Morphy 2008; Hughes and Barlo 2021). As such, it is possible that this may have had some leading effect on interview responses. Recognising that there always exists some level of misrepresentation or misinterpretation risk stemming from bias relating to the framing of Western conceptualisations in cross-cultural settings, and the inherent power relationalities conducting research in English and from a Western perspective (Kanngieser et al. 2024), a practical step to ensure this is mitigated (or managed), at least to some extent, is ensuring active and continuous engagement and consultation to ensure that research and results reflect the true ambitions and priorities of Traditional Owners.

If Yolŋu decision makers decide that they wish to pursue exploration of a potential biocultural market, the next step in implementation of the BCAF would be to secure funding to explore application and refinement of the framework through a biocultural conservation project. The implementation phase would likely also benefit from research into investor interest in the framework. Whether the value created through a biocultural project could be verified and sold on market still requires further research. Although developing such schemes incorporates the very real risk of cost shifting (Gordon et al. 2015), it is likely that the need for government funding will continue. Government funding of Indigenous land and sea management is likely to continue, given government policy shifts towards increasing protected areas, with a specific current focus on Indigenous Protected Areas (Plibersek and Burney 2024).

Key considerations and attributes needing further attention should this initiative proceed include core pillars relating to transparency, rights and shared benefits, auditability, and measurability of positive impact. Ensuring quality core-baseline data for measuring impact with integrity while maintaining cultural knowledge and values is important and may be challenging. Defendable and culturally appropriate baseline data are required to ensure the credibility and effectiveness of a potential biocultural credit market. Ensuring that future initiatives have enough quality baseline data to track condition and state of biocultural targets and actions will be vital to ensure quality, accuracy, and integrity across all projects.

Conclusions

This study proposes a ‘Biocultural Credit Accounting Framework’ within the scope of nature-positive investment to help deliver biocultural conservation within remote Indigenous Protected Areas. Progression of research into a potential biocultural credit market ultimately remains at the discretion of Yolŋu decision makers. Regardless of any future credit markets or interests of external stakeholders, the development of the framework is of high value in of itself as a tool that protected-area managers and rangers could use to transparently monitor success internally, guide adaptive management, and report back to communities and Elders.

Data availability

All data, for participants who consented, will be stored on the Aboriginal Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders Studies (AIATSIS) library. https://aiatsis.gov.au/collection/donate-collection.

Conflicts of interest

Emilie Ens is a Guest Editor of the ‘Indigenous and cross-cultural wildlife research in Australia’ special issue of Wildlife Research. To mitigate this potential conflict of interest they had no editor-level access to this manuscript during peer review. The author(s) have no further conflicts of interest to declare.

Declaration of funding

This project was funded through an Australian Research Council Linkage Project (200301589) with support from industry partners The Nature Conservancy and Laynhapuy Homelands Aboriginal Corporation.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the Yolŋu Traditional Owners, past, present, and future, of Garrata and Gapuwiyak and the Dharug Traditional Owners of Macquarie University where the research was conducted. We thank funding bodies: the Australian Research Council (LP200301589) and industry partners The Nature Conservancy and Laynhapuy Homelands Aboriginal Corporation. Thanks go to Chris Spurr (Gapuwiyak Learning on Country Coordinator) who assisted with field work and local contacts and to Daniel Sloane, Shaina Russell and Jonathan Smuskowitz for discussions around the BCAF idea. Extended thanks go to editorial staff and peer reviewers who contributed to framing of discussions.

References

AIATSIS (2020) National Indigenous Languages Report. Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications, Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Straight Islander Studies, Australian National Univeristy, Australian Government, Canberra, ACT, Australia. Available at https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/items/387c885a-7fc4-4904-9694-25488d6e2ebe

Althor G, Mahood S, Witt B, Colvin RM, Watson JEM (2018) Large-scale environmental degradation results in inequitable impacts to already impoverished communities: a case study from the floating villages of Cambodia. Ambio 47, 747-759.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Altman JC, Buchanan GJ, Larsen L (2007) The environmental significance of the Indigenous estate: natural resource management as economic development in remote Australia. Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research, Canberra, ACT, Australia. Available at http://hdl.handle.net/1885/145629

ANAO (2011) The auditorgeneral audit report no. 14 2011/12 performance audit: Indigenous protected areas. Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities. Australian National Audit Office, Canberra, ACT, Australia. Available at https://www.anao.gov.au/sites/default/files/201112%20Audit%20Report%20No%2014.pdf

Austin BJ, Robinson CJ, Fitzsimons JA, Sandford M, Ens EJ, Macdonald JM, Hockings M, Hinchley DG, McDonald FB, Corrigan C, Kennett R, Hunter-Xenie H, Garnett ST (2018) Integrated measures of Indigenous land and sea management effectiveness: challenges and opportunities for improved conservation partnerships in Australia. Conservation and Society 16, 372-384.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Barney K, Mackinlay E (2010) ‘Singing trauma trails’: songs of the stolen generations in Indigenous Australia. Music and Politics IV, 1-25.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

BBOP (2018) Glossary. Business and Biodiversity Offset Programme. 3rd edn. BBOP, Washington, DC, USA. Available at https://www.forest-trends.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/BBOP_Updated_Glossary-01-11-18.pdf [accessed 12 December 2023]

Biodiversity Credit Alliance (2023a) Demand-side sources and motivation for biodiversity credits. Issue paper no 1. Biodiversity Credit Alliance. Available at https://www.biodiversitycreditalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/BCAIssuePaper_DemandOverview06122023-final.pdf

Biodiversity Credit Alliance (2023b) Communities and nature markets: building just partnerships in biodiversity credits. Discussion paper. Biodiversity Credit Alliance. Available at https://www.biodiversitycreditalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/BCA-Discussion-Paper_Building-just-partnerships-in-Biodiversity-Credits.pdf

Biodiversity Credit Alliance (2024) Definition of a biodiversity credit. Issue paper no. 3. Biodiversity Credit Alliance. Available at https://www.biodiversitycreditalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Definition-of-a-Biodiversity-Credit-Rev-220524.pdf

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3, 77-101.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Bridgewater P, Rotherham ID (2019) A critical perspective on the concept of biocultural diversity and its emerging role in nature and heritage conservation. People and Nature 1, 291-304.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Bull JW, Suttle KB, Gordon A, Singh NJ, Milner-Gulland EJ (2013) Biodiversity offsets in theory and practice. Oryx 47, 369-380.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Butler T, Gall A, Garvey G, Ngampromwongse K, Hector D, Turnbull S, Lucas K, Nehill C, Boltong A, Keefe D, Anderson K (2022) A comprehensive review of optimal approaches to co-design in health with first nations australians. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, 16166.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Campbell BL, Yirralka Rangers, Yolŋu Knowledge Custodians, Gallagher RV, Ens EJ (2022) Expanding the biocultural benefits of species distribution modelling with Indigenous collaborators: case study from northern Australia. Biological Conservation 274, 109656.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Campbell B, Russell S, Brennan G, Yirralka Rangers, Condon B, Gumana Y, Morphy F, Ens E (2024) Prioritising animals for Yirralka Ranger management and research collaborations in the Laynhapuy Indigenous Protected Area, northern Australia. Wildlife Research 51, WR24071.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Carroll SR, Rodriguez-Lonebear D, Martinez A (2019) Indigenous data governance: strategies from United States Native nations. Data Science Journal 18, 31.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Carroll SR, Garba I, Figueroa-Rodríguez OL, Holbrook J, Lovett R, Materechera S, Parsons M, Raseroka K, Rodriguez-Lonebear D, Rowe R, Sara R, Walker JD, Anderson J, Hudson M (2020) The CARE principles for indigenous data governance. Data Science Journal 19, 43.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Carroll SR, Herczog E, Hudson M, Russell K, Stall S (2021) Operationalizing the CARE and FAIR principles for indigenous data futures. Scientific Data 8, 108.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |