Yarning up with Doc Reynolds: an interview about Country from an Indigenous perspective

Doc Reynolds A and Liz Cameron B *

B *

A

B

Abstract

This article uses Yarning with Country as a methodological approach where Country plays a pivotal role as an active participant. Our focus is on examining how we learn from and establish respectful, reciprocal, and accountable relationships with Country, as told through the eyes and experiences of knowledge holders, in this case, Doc Reynolds. The knowledge shared about the importance and meaning of Country contributes to advancing ecological-research methodologies to better acknowledge and learn from Indigenous knowledge systems, offering insights into sustainable practices and community engagement within landscapes. This body of knowledge serves as an invitation for Australians to reconceptualise Country, envisioning it both as a noun and a verb. As a noun, Country represents the physical landscape and environment, imbued with cultural significance and history. As a verb, it highlights the dynamic and interactive relationships that exist between people and their environment. This dual understanding encourages a deeper engagement with Country, that it is not merely a backdrop for human activity but a living entity that requires care, respect, and ongoing dialogue.

Keywords: biodiversity, Caring for Country, culture, Indigenous, Yarning.

Introduction

Positioning

Doc Reynolds is a Wudjari Nyungar, Mirning, Ngudju man, Elder and Director, Senior Cultural Advisor for the Esperance Tjaltjraak Native Title Aboriginal Corporation. He has led numerous research projects, contributing to project design, field data collection and cultural mentorship.

Liz Cameron is a Dharug academic and researcher at the School of Architecture and the Built Environment at Newcastle University. Her work involves embedding Indigenous knowledge into the curriculum, placing the Country at the centre of all learning, and engaging creative practices alongside Western scientific research.

Research through Yarning

Aboriginal conversations usually occur around a fire where we sit on Country, immerse ourselves through talk and connect with the spiritual, human, non-human and biophysical aspects of our Country (Cameron 2020). The act of Yarning serves as a medium to establish and build respectful relationships, exchange stories and traditions and preserve and pass on cultural knowledge (Hughes and Barlo 2021). This interview with Doc Reynolds (Fig. 1) began like all other initial Yarning conversations on who we are and where we belong (see Cooke et al. 2022). The practice of Yarning embodies a reciprocal form of communication utilised by Aboriginal communities to share lived experiences (Geia et al. 2013). Rooted in Aboriginal ways of knowing, being, and doing, Yarning integrates history, culture, language, and identity, transmitting ancestral wisdom and fostering group belonging (Eades 2013). Yarning involves storytelling that conveys profound meanings, transcending mere exchange to facilitate sharing, exploration, and learning across generations (Yunkaporta 2019). As a potent methodology, Yarning situates the researcher within a network of relationships encompassing research participants, ancestral knowledge, Country, and the narratives of past and future. Guided by principles and protocols, Yarning creates a safeguarded space to respect these relationships with accountability, and integrity, thereby enriching research outcomes that authentically respond to lived realities.

Doc Reynolds, Senior Australian of the Year, Western Australia, 2024. Source: https://australianoftheyear.org.au/recipients/ronald-reynolds.

Yarn context: Doc Reynolds

The body of this Yarn up centres around Kepa Kurl, the Noongar name for Esperance, which translates to ‘where the waters lie like a boomerang’. In 2019, this region was proposed for listing and inclusion under Australia’s network of marine protected areas, specifically the South Coast Marine Park. Esperance is located on Western Australia’s south-eastern coast, about 714 km from Perth, covering >53,000 km2.

The Esperance Nyungars of south-western Australia adhere to a six-family governance system, established during the Native Title claim process and maintained through the establishment of the (ETNTAC) in 2014. ‘Tjaltjraak’ originates from the Wudjari term for the Mallee, which marks the boundary of their Country. ETNTAC was established as the Native Title Body Corporate for the Kepa Kurl Wudjari people by the Federal Court of Australia on 6 September 2016. The ancestral lands of the Kepa Kurl Wudjari people encompass over 30,000 km2 in the southern area of Western Australia. The Dutch explored the coastline in 1627, followed by the French in 1792, who bestowed names on numerous coastal and island landmarks. Esperance Bay was named by French navigator Antoine Raymond Joseph de Bruni d’Entrecasteaux, during a storm where his ships Le Esperance and Le Recherche sought shelter near Observatory Island in 1792. European settlement began in the 1870s, and from there, farming activities dominated the area, although significant portions have been designated as national parks.

We acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the land on which we live and work, Kepa Kurl Wudjari people of the Nyungar Nation, and we pay our respects to their Elders past, present and emerging.

Doc (Ronald) Reynolds intertwines traditional culture with scientific inquiry, community development, and tourism initiatives in Esperance. A Wudjari Nyungar Mirning Ngudju man and custodial knowledge holder, Doc, has pioneered various efforts to bridge Indigenous heritage with contemporary practices. Through his visionary leadership, Doc spearheaded the Bay of Isles Aboriginal Community Inc., after it was established by his late mum, sister and cousin and later instigated the Gabbie Kylie Foundation in 2007 to conserve and interpret the Indigenous heritage values of Western Australia’s (WA) southern coast region and to enable Traditional Owners to re-establish their connections with Country. The Foundation’s core program provided a holistic approach to Caring for Country that integrates diverse groups and agencies involved in land and heritage management. The Foundation has documented a number of unrecorded rock art motifs and stone arrangements, developed the first model of marine transgression and island formation off Archipelago; identified numerous archaeological sites and conducted a number of environmental conservation projects. The Foundation was a category finalist in the 2010 Banksia Environmental Awards.

Within the Esperance Tjaltjraak Native Title Aboriginal Corporation, Doc is an Elder, Senior Cultural Advisor, and Director. Doc has led numerous research projects, contributing to project design, field data collection and cultural mentorship. Doc also operates the award-winning Kepa Kurl Enterprises, which runs cultural tours of Esperance as well as heritage surveys. In 2022, Doc was awarded the states tourism honour, the Sir David Brand Medal for Contribution to Tourism in Western Australia, and is an Inaugural Inductee to the Hall of Fame in the WA Landcare Awards 2023.

Yarn-up session

Liz: it was good meeting you again, Doc. We first met in Melbourne attending the Biodiversity Council back in 2022 as lead Indigenous counsellors. As we both work with Country, what significant activities have you been involved in?

Doc: tomorrow, we celebrate our 10th anniversary on Native Title. It was 30 years ago we started our claim. The Federal Court of Australia registered Esperance Tjaltjraak Native Title Aboriginal Corporation (ETNTAC) as the Native Title Body Corporate for the Kepa Kurl Wudjari people on 6 September 2016. This now means we are the first point of contact for the government and other groups who want to conduct business with Traditional Owners in Esperance.

Liz: that’s an incredible achievement, as I have witnessed many mob still undergo the long process of Native Title claims. Proving your ongoing connection to the Country is often challenging for some, especially where there has been widespread urbanisation or agricultural development, both of which extinguish Native Title. What does Country mean to you?

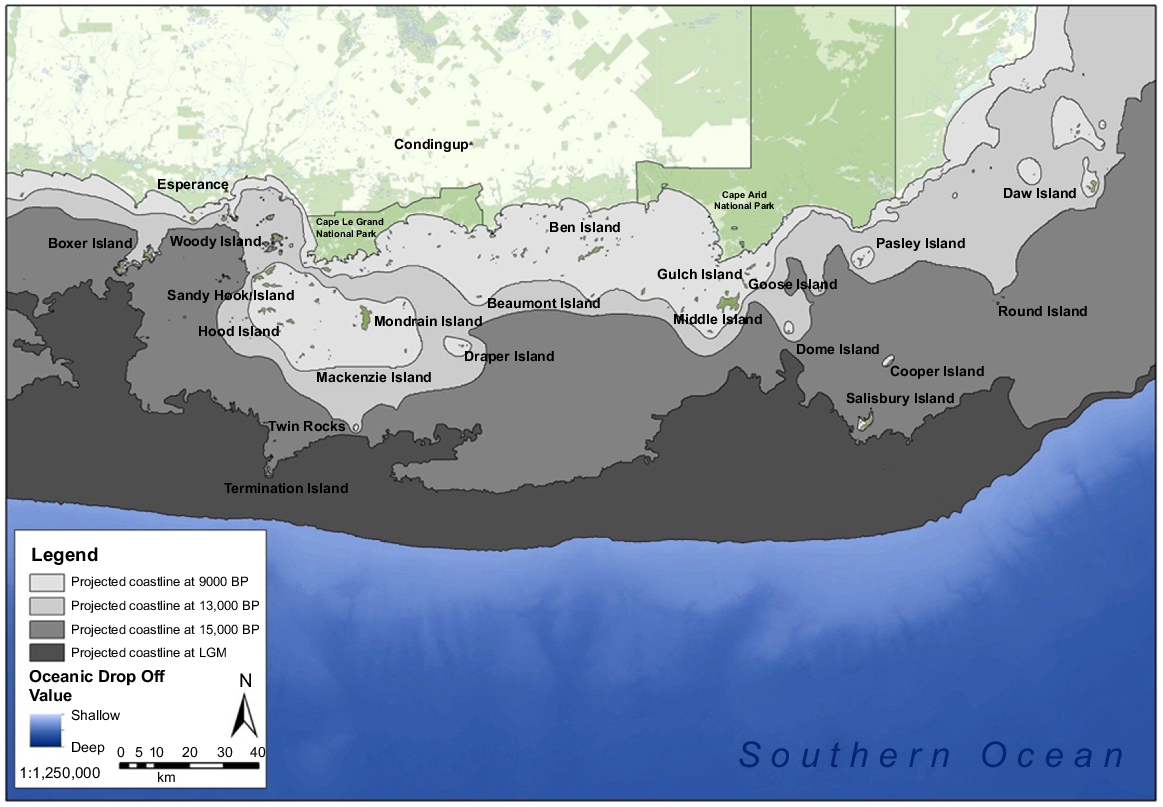

Doc: Country, to me, it means us. Its where we come from. Country is Mother Earth, and all living thing comes from Mother Earth in its entirety. So, if you talk about wildlife, then you classify us as we are a part of it. We are its original inhabitants, and we have a responsibility to look after Country and care for it. By protecting and respecting the spiritual foundations of Country we can restore our animals, plants, and people, heal our families and Law, and our cultural places. Our Elders set the benchmarks on Country. By that, I mean that if we think about what state we would like our shared world to be in, we should look to the world our Elders, the Old People, left for us. It is our cultural responsibility to help restore those benchmarks in a challenging and evolving environment (Fig. 2).

Map of Country, sources from Esperance Tjaltjraak Native Title Aboriginal Corporation. Source: https://www.facebook.com/etntac/.

Liz: what parts of Country inspire you?

Doc: our ocean work – the marine work we do. We have over 100 islands off Esperance, also known as the Recherche Archipelago. It comprises a total area of 9720 ha. Many of the islands are unique. The archipelago is all granite with Middle and Salisbury Island, a landmass of limestone and granite. The waters surrounding Salisbury Island are a haven for white sharks because of the distinctive biodiversity out there. There is also New Zealand fur seals, black flanked wallabies, shearwaters and the threatened Australian sea lion. Woody Island is a haven for birdlife such as brown quail (Synoicus ypsilophorus), rock parrot (Neophema petrophila), spotted pardalote (Pardalotus punctatus) and the Australian raven (Corvus coronoides). We’ve found evidence of original occupation on all the islands, too.

Based on that work, we’ve been successful in getting a multimillion-dollar grant to do ancient seafloor mapping. This involves studying the oceanic floor and its features using various geological and geophysical techniques as a way to reconstruct the topography, composition, and other characteristics of our ancient coastlines (back during the last glacial maximum). This information is crucial for understanding our shared geological history and the evolution of oceanic environments. Of course, this also involves connecting, reconnecting, and expanding what we call our cultural corridors.

Liz: can you talk about cultural corridors, their relationship with Country, and their long-term impact on maintaining and restoring effective ecological connectivity?

Doc: cultural corridors is a term we sometimes use to describe landscapes in a way that reflects their cultural patterns. They include the movement of species, river systems, and other conservation areas. When we talk about cultural corridors, it’s important to understand that they are plural. Each Aboriginal nation holds their own beliefs and practices and their own corridors. These corridors represent connections between different places, landmarks, and resources that are integral to our cultural identity and heritage. For Wudjari people, we know that the cultural corridors started with our river systems. This is because rivers are the natural corridors and arteries of Country – they are integral connectors that provide multiple ecosystem benefits. We depend on them. The Ancient Corridors project we are running recognises that cultural systems in the past were interwoven with the landscape and its ecosystems. This project uses cultural knowledge to explore the human–environment dynamics and includes cultural stories and songlines that extend from the mainland and across the Archipelago.

Liz: how are the Tjaltjraak Rangers involved in Caring for Country?

Doc: the Rangers are a critical part of our community and carry out important works in line with their obligations to care for Country. The rangers are involved in works to protect and rehabilitate Country, manage invasive species, monitoring and surveying for endangered species, sharing knowledge and influencing environmentally sustainable practices through community education events. They also work to protect sites of enormous cultural and historical significance. The team actively manages the entire region and engages in a variety of activities, including mapping, Landcare initiatives, dune stabilisation, erosion control, and visitor management, in partnership with state and local government agencies.

Liz: compared to Western understandings of the coastal and offshore zones, Indigenous ways of knowing and managing Sea Country are more Country-centred – they emphasise the interconnectedness of all things, including the tangible and intangible elements within. How do songlines inform your practice?

Doc: for us, everything on Country is both tangible and intangible. For instance, the tangible elements of Country extend beyond specific flora and fauna. They include ecological and cultural processes, changes over time, smells, sites, etc. The intangible includes songlines at the campground, it’s the hunting areas, ceremonial areas, and significant sacred areas. In this, our songlines serve as oral maps that encode cultural and geographic information, enabling us to navigate vast landscapes, pass on knowledge, and maintain connections between communities. Recognising and protecting Aboriginal cultural heritage (including songlines and cultural landscapes) is crucial to acknowledging our history and connection to our lands, seas and skies. This heritage includes our sense of interconnectedness between people, land, and tradition. Interconnectedness between humans and nature guides our practices of stewardship and respect. For instance, we harvested resources sustainably, ensuring the balance of ecosystems and utilising every part of the animal with respect. Thus, we maintained a reciprocal relationship that promotes sustainability – a space where humans and nature thrive together.

Liz: when we consider sustainable practices through a holistic, place-based knowledge framework, we distinctly differ from Western knowledge traditions. Our holistic worldviews focus on the importance of connections and relationships where Caring for Country – it is more than just an activity but has meaning in terms of the transference of knowledge. What approaches do you use in your Caring for Country projects, and are there any additional training opportunities that complement this work?

Doc: we use a multi-disciplinary approach. And that means we holistically look at things. We don’t just tunnel vision. The ranger program employs Aboriginal people to undertake land and sea management activities such as biodiversity monitoring and research, fire management, cultural site management, and feral animal and weed management. Our work is informed by traditional cultural knowledge but also by research undertaken by other experts and allies, including anthropologists, archaeologists, biologists, sociologists, and others from around the world. We are now a driving force behind innovative and impactful ecological, archaeological, social, and political research in the region, which we are proud of.

Our rangers also undertake training to equip them for their work and to further their career opportunities. On-the-job training, accredited courses, and non-accredited training such as first aid, cultural heritage, fauna handling, four-wheel drive, and digital media offer mob with new ways of doing. The Rangers recently completed marine mammal observation (MMO) training conducted by Blue Planet Marine in Perth. This is the first Cultural Ranger group on the southern coast/southwest of Western Australia to undergo the intensive two-day training course. The team learnt vital skills in understanding potential impacts on marine life that strengthened the team’s expertise. The Rangers also undertook a week of workshops and fieldwork recently on Woody Island from Parks Australia, the Australian Hydrographic Office, and UWA Marine Ecology. They are probably now some of the most well-trained and most multi-disciplinary Rangers on the planet!

Liz: restoring Country within the built environment is an essential aspect of my work, focusing on integrating Indigenous Knowledge Systems to create sustainable, resilient and protected significant spaces. Like any environmental initiative, this approach considers the impact of human activities on Country and seeks restorative practices to heal and respect Country from a multi-species perspective. In the recent New South Wales (NSW) Biodiversity Outlook Report 2024 (NSW Government 2024), it highlights alarming trends in biodiversity decline due to habitat loss, climate change, and invasive species. The report reveals that only 50% of threatened species are expected to survive the next 100 years, and the capacity of habitats to support native species has plummeted to just 29% (NSW Environment and Heritage). These findings underscore the urgent need for a paradigm shift in how we design and interact with our environments; however, little attention focuses on the built environment. Responding to the built environment, we need to start viewing urban planning that aligns with Country rather than against it. My work concerns educating students to create architectural designs that support biodiversity (Nelson and Shilling 2018), promote ecological health and sustainability (Macdonald and Johnson 2019), by considering all living and non-living things in Country. I base my foundational knowledge on the principle of ‘Healthy Country, Healthy People’, a holistic view that advocates for environmental stewardship by prioritising the protection of water, promoting biodiversity, creating spaces that harmonise with natural surroundings and caring for localised flora and fauna. Considering multi-species in the built environment involves shifting from a human-centric to a more inclusive approach that embraces ecological interconnectedness, we need to start recognising that built spaces are not just for humans but are shared habitats where various species coexist. Can you yarn with me about what animals you come across on your Country? What changes do you note, and what concerns you on their health?

Doc: the Tjaltjraak Rangers encounter a diverse array of animals on our Country, each playing a vital role in our ecosystem. Over time, we’ve observed changes in their behaviour, habitats, and populations, which raise concerns about their health and wellbeing. For instance, we have studied the critically endangered western ground parrot and working to help protect their habitats. We are also working with other experts with the threatened mallee fowl and Barnaby’s black cockatoo. Some of the other animals we commonly encounter include kangaroos, emus, echidnas, wallabies, dingoes, and reptiles, as well as various bird species such as eagles and parrots. We’ve noticed shifts in their distribution patterns, possibly due to factors like habitat loss, climate change, and human activities. For example, changes in vegetation cover may impact the availability of food and shelter for these animals, leading to disruptions in their natural behaviours and migration patterns. Additionally, disturbances such as wildfires, pollution, and invasive species pose significant threats to their habitats and health.

We have an ornithologist (a bird expert) working with us. In 2023, we received a grant to focus on the region’s seabirds, many of which breed nearby. The project involved a seabird survey as dozens of dead shearwaters were found washed up on local beaches, which caused deep concern with the community. The grant will be used for Bird Research and Conservation by the Tjaltjraak Rangers to conduct a workshop where they will come together with experts, special interest groups, and the local community to share knowledge on designing a long-term beached-bird monitoring program.

We also have many marine animals like shearwaters, seals, penguins and sharks. They tell us if the oceans are healthy or are not. The Great Southern Reef, kelp and seagrass habitats of Archipelago support a high diversity of species, including many varieties of fish, leafy sea dragons, blue morwong (blue Grouper), abalone, sharks, southern rock lobster, etc. The islands also provide resting areas and breeding sites for shearwaters (Ardenna pacifica), endangered Western Cape Barren geese (Cereopsis novaehollandiae grisea), penguins (Eudyptula novaehollandiae), endangered Australian sea lions (Neophoca cinerea) and New Zealand fur seals (Arctocephalus forsteri).

When we see the cultural relevance of marine life, we start seeing the marine biodiversity, we start seeing the animals. And when we start travelling out there, we start looking at the habitats out there, we notice that the marine habitats are changing. We are also looking at the rise of sea levels and trying to retrace those tracks because we have simulations where you can see how the sea levels rose with from the last Ice Age. On Middle Island, 120 kilometres south-east of Esperance, the rangers are working to preserve one of the world’s rarest marsupials, the Gilbert’s potoroo. It is a relative of the kangaroo and is critically endangered, with only about 100 left in existence. The most significant threats to the survival of the Gilbert’s potoroo have been summarised as altered fire regimes, introduced predators, including foxes and cats, and native vegetation decline. Every 3–6 months, Rangers from the Esperance Tjaltjraak Native Title Aboriginal Corporation travel to the island to download footage from three motion sensor cameras set-up.

Liz: cultural burning, or traditional fire management practices plays a crucial role in NSW, in maintaining and restoring ecological balance. Research shows that these controlled burns can enhance habitat quality for native species, as they are reliant on specific stages of habitat succession (Gammage 2011), and significantly reduce the severity and extent of wildfires, contributing to healthier landscapes (Bowman et al. 2011). As part of Caring for Country, what role does cultural burning play?

Doc: in the marine space, we see cultural burning as helping to protect seabird breeding sites on the islands. The shearwaters return to the same place each year to breed, but it’s difficult for the species to create burrows when fire has burnt away the vegetation that holds the ground together. Cultural burns are necessary to prevent out-of-control wildfires, which make these impacts. Cultural burns are low-intensity, mosaic burns which reduce fuel loads that have few impacts on species. Cultural burning is a method of enhancing biodiversity. So, cultural burns also safeguard seabird colonies.

Doc: cultural burning on Country helps keep it healthy. It is proven that cultural burning also helps with ecological rejuvenation. In 2020, a bushfire happened on Eight Island, resulting in the mortality of thousands of short-tailed shearwaters (Ardenna tenuirostris) that breed on the island – few have returned to the island due to damage to the burrows caused by the fire. We want to reinstate cultural burning regimes across our lands and restore traditional practices that have been disrupted by colonial government policies. We are investigating whether traditional fire regimes can reduce the impact and intensity of bushfires, and that can play a role in protecting breeding populations (Fig. 3).

The Healthy Country Plan is defined by agreed cultural and biodiversity values and provides a 10-year road map for Tjaltjraak’s Land Management Program. Source: https://etntac.com.au/services/healthy-country-plan-and-rangers.

Liz: Australia has lost far more mammals to extinction than any other country. Mammal species are threatened by feral predators, changed fire regimes, pathogens, vegetation fragmentation and climate change. Feral animals often outcompete our native species and disrupt our ecological balance. But we also see the word ‘feral’ or ‘pest’ used to describe some of our native species. Considering kangaroos as pests rather than an iconic Australian animal that play vital roles in ecosystem balance is a contentious issue, with opinions varying depending on perspectives and contexts. What are your thoughts regarding feral animals?

Doc: we have a feral cat (Felis catus) problem, which has had devastating effects on native wildlife. The western ground parrot (Pezoporus wallicus flaviventris) numbers have reduced due to cats being efficient hunters – they stalk through dense bush as well as along cleared tracks. They come after the chicks and eggs because the parrot nests on the ground under the bush. The European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) has also become widespread, causing extensive damage to vegetation through grazing and burrowing activities. Rabbits have had a significant impact on native animals and ecosystems since their introduction. Rabbits are prolific grazers and can rapidly strip vegetation, leading to habitat degradation. This affects native animals that are dependent on that vegetation for food and shelter. Rabbits can outcompete native herbivores and small mammals for resources, altering the balance of predator–prey relationships. The red fox (Vulpes vulpes) also preys on our native mammals and birds. They are efficient predators and prey on the eggs of ground-nesting birds, such as ground-nesting seabirds and native game birds.

The perception of kangaroos, dingoes, and emus as pests in Australia is complex and can stem from various factors, such as conflict with agriculture, where kangaroos are grazing on crops, leading to economic losses for farmers. Dingoes, in particular, are sometimes perceived as a threat to human safety, especially in areas where interactions with humans are common. We are trying to turn that image around.

Liz: as we conclude our Yarn about wildlife and biodiversity, in Caring for Country, it’s evident that these topics are deeply intertwined in how we care for Country. The health of our lands, seas and skies is reliant on our health and well-being. Balancing conservation efforts with human needs necessitates an interplay between Indigenous knowledge and scientific understanding, a synergy where each complement and enriches the other. By integrating Indigenous knowledge with scientific research, governments and conservation agencies can develop holistic management strategies that actively engage with Indigenous communities as equal partners in decision-making processes. This means co-designing policies and management plans that incorporate Indigenous perspectives, priorities, and aspirations for Country.

Thoughts and reflections

Indigenous Country management presents intricate challenges that demand a fundamental shift in our thinking. Historically, prioritising human-centric needs and pursuing short-term gains and economic development have come at the cost of ecological and cultural integrity, leading to the rapid decline in the health of many Indigenous Countries. To address this, we must embrace paradigms that centre on the needs of the land, waters, and all living and non-living beings that are interconnected within it. This shift involves recognising Indigenous Knowledge Systems, which have long guided practices of stewardship and conservation. It is essential to understand that the health of Country is inseparable from the well-being of its people, and decision-making must be grounded in principles of reciprocity, respect, and long-term sustainability. By adopting practices informed by the values and principles of Country, we can actively work to restore ecological balance and foster a more ethical and sustainable relationship with our environment.

We conclude our discussion with an invitation for Australians to reconceptualise Country both as a noun and a verb. As a noun, Country represents a specific geographic area imbued with its unique cultural, ecological, and historical essence. As a verb, Country signifies an active, relational approach to engagement and stewardship. This dual perspective challenges us to transcend conventional boundaries, fostering a deeper connection with Country and recognise its intrinsic value beyond mere resource or territory. By embracing this worldview, Caring for Country becomes a reflection of our own humanity, ethical responsibility and commitment to a more harmonious and sustainable existence.

Declaration of funding

No sources of funding for the research and preparation of the article did not receive any specific funding.

References

Bowman DMJS, Balch JK, Artaxo P, Bond WJ, Cochrane MA, D’Antonio CM, DeFries R, Johnston FH, et al. (2011) The human dimension of fire regimes on earth. Journal of Biogeography 38(12), 2223-2236.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Cameron L (2020) ‘Healthy Country, Healthy People’: Aboriginal Embodied Knowledge Systems in Human/Nature Interrelationships. The International Journal of Ecopsychology 1(1), 3.

| Google Scholar |

Cooke P, Fahey M, Ens EJ, Raven M, Clarke PA, Rossetto M, Turpin G (2022) Applying biocultural research protocols in ecology: insider and outsider experiences from Australia. Ecological Management & Restoration 23(S1), 64-74.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Geia LK, Hayes B, Usher K (2013) Yarning/Aboriginal storytelling: towards an understanding of an Indigenous perspective and its implications for research practice. Contemporary Nurse 46(1), 13-17.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Hughes M, Barlo S (2021) Yarning with country: an indigenist research methodology. Qualitative Inquiry 27(3–4), 353-363.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |