Preferences for the delivery of early abortion services in Australia: a discrete choice experiment

Jody Church A * , Marion Haas A , Deborah J. Street A , Deborah Bateson

A * , Marion Haas A , Deborah J. Street A , Deborah Bateson  B and Danielle Mazza C

B and Danielle Mazza C

A

B

C

Abstract

Abortion is a common procedure in Australia; it is estimated that the rate is between 15 and 17 per 1000 women. Surgical and medical abortion options are available; however, the use of medical abortion is not as common as in other similar countries. The aim of this study is to understand preferences for the provision of early abortion services in Australia.

We conducted a survey of 821 members of an online panel representative of the Australian adult general population. The survey consisted of a discrete choice experiment including 16 choice tasks and a number of follow-up questions. A mixed logit model was used to analyse the responses to the discrete choice experiment.

Respondents preferred services that provided surgical abortion compared with early medical abortion (EMA). They preferred consultations with a specialist gynaecologist compared with a general practitioner (GP); consultations with a GP were preferred to those with a nurse practitioner. Face-to-face consultations were preferred to telehealth. For EMA, respondents preferred to collect medication from the doctor’s surgery rather than from a pharmacy or to receive it by post. Overall, respondents preferred lower-cost services. There were no differences in preferences between respondents with or without experience of abortion or between genders.

Respondents prefer abortion services with low out-of-pocket costs. Their reluctance to use a nurse-led service may reflect the general public’s lack of understanding of and familiarity with the training and expertise of nurse practitioners. Similarly, the safety and benefits of EMA relative to surgery, including EMA delivered by telehealth, need to be emphasised.

Keywords: abortion services, Australia, discrete choice experiment, early medical abortion, nurse-led care, preferences, primary care, telehealth.

Background

Abortion is a relatively common procedure in Australia. One in four women experience an unintended pregnancy during their lifetime; approximately one-third of these pregnancies end in abortion.1 Although there is no national data collection, some recent estimates (2017–2018) indicate that the abortion rate in Australia is between 15 and 17 per 1000 women.2 Most, but not all, abortions in Australia are performed before 20 weeks’ gestation, with ~2% of abortions performed after 20 weeks’ gestation.3

Abortion is legal throughout Australia. Surgical abortions are typically day procedures, performed in a private clinic by a specialist gynaecologist, GP or other doctor trained in conducting the procedure. Early medical abortion (EMA), the combination of mifepristone and misoprostol (MS-2Step), is both safe and effective taken at home or in a clinic under the care of a health professional.4 EMA is supported by the World Health Organization from both a public health and individual health perspective, and is registered in Australia for use up until 9 weeks’ gestation. However, EMA does not appear to be as common in Australia as it is in other similar countries; in most northern European countries, EMA accounts for two-thirds of all abortions.5 Currently in Australia, only 10% of (GPs are registered providers of EMA, with 30% of pharmacies registered to dispense EMA medications.6

The efficacy of both first trimester surgical abortion and EMA is >95%, and complications are rare.7 Access to abortion services can be challenging, particularly for women living in regional or rural areas. It has been suggested that EMA, delivered face-to-face or by telehealth, is one way of overcoming this barrier.8 Cost may also be a barrier for women trying to access early abortion (medical or surgical); currently, out-of-pocket costs range from A$100 to A$800.

The policy of the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology is that access to a range of medical and surgical abortion services should be equitable and not limited by age, socioeconomic disadvantage or geographic location.9 In the primary care setting, GPs are ideally positioned to provide EMA as a core component of sexual and reproductive health services. However, GPs face structural and knowledge barriers in the provision of EMA,7 including legal requirements, stigma and lack of guidelines.10 The provision of publicly funded first trimester surgical abortion is rare, and community awareness and knowledge of EMA is low.

Information from individuals seeking or accessing abortion services indicated high levels of satisfaction with EMA and a preference for self-administration at home,11 but being able to choose the type and place of abortion method remained important.12 However, there is limited understanding of the preferences of the general public for the provision of early abortion services, and no research has addressed this topic in Australia. Discrete choice experiments (DCE) are an ideal means to investigate the factors underlying such preferences. The research question addressed in this study was, ‘What are the preferences of the general public in Australia for the delivery of abortion services?’. Information from this research will allow the identification of the most important characteristics of early abortion services, enabling input from (potential) consumers to inform the design of new and/or modified services. This may further support local health service providers in determining appropriate approaches to best suit their specific communities.

Methods

Study design

DCEs are a popular stated preference tool used in health economics to address policy questions or to establish consumer preferences for health and health care. A DCE is designed as a hypothetical, but realistic, representation of an actual choice, operationalised as a survey. Typically, respondents are presented with a situation in which a choice must be made. They are shown sets of options and asked to choose their preferred option from each set presented to them. The options are described in terms of attributes (features); each attribute is presented at one of a number of possible levels, chosen to vary over a plausible and policy-relevant range. The goal of the experiment is to estimate how the attribute levels affect respondents’ choices, assuming that the choices made reflect underlying preferences.13 The advantage of DCEs over traditional rating or ranking scales is that they force respondents to discriminate, or trade-off, between items.14

DCE development

The factors relevant to the delivery of abortion services were identified through a multi-step process. First, a literature search was conducted to identify previous research which investigated factors that individuals considered when thinking about or making decisions regarding the provision of abortion services. Second, clinical experts in women’s sexual and reproductive health were consulted regarding these factors, determining the final attributes and corresponding levels. Finally, feedback on the vignette, choice set presentation and survey layout was provided by a DCE special interest group at the University of Technology Sydney (Centre for Health Economics Research and Evaluation (see Section 1 of Supplementary material for details).

The attributes and levels focused on the delivery of abortion services; as abortion outcomes (such as rate of incomplete abortion, bleeding or adverse events) are similar for EMA and surgical abortion, these were not included as attributes. The attributes incorporated the following aspects of abortion services: assessment, provision of services, follow-up consultation and costs. The levels chosen for the assessment, service provision and follow-up attributes represent plausible options for abortion services. The levels of cost were also plausible: consumers using services provided in the public sector would face no out-of-pocket (OOP) costs (A$0); the three other levels of total OOP costs (A$350, A$580, A$775) were used to represent the range in possible OOP costs across states and clinics.15 The OOP costs represented costs incurred for an initial consultation, ultrasound tests, abortion procedure or medication and follow-up consultation/s. Table 1 lists the attributes and levels used in the DCE.

| Attributes | Medical abortion | Surgical abortion | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment | |||

| Referral from woman’s GP required | Yes No | Yes No | |

| Healthcare professional who conducts initial consultation | Woman’s GP Specialised GP Nurse practitioner Specialist gynaecologist | Woman’s GP Specialised GP Nurse practitioner Specialist gynaecologist | |

| Consultation type | Telehealth Face-to-face | Telehealth Face-to-face | |

| Tests provided | As part of the consultation At a local pathology/imaging service | As part of the consultation At a local pathology/imaging service | |

| Provision of service | Medication delivered by post Medication collected from pharmacy Medication collected from doctor’s surgery | Day procedure – private clinic Day procedure – public clinic | |

| Follow-up consultation | Telehealth Face-to-face | Telehealth Face-to-face | |

| Out-of-pocket costs to the woman | A$0 A$350 A$580 A$775 | A$0 A$350 A$580 A$775 | |

Note: the design ensured that referral required ‘yes’ never appeared with ‘woman’s GP’, ‘Specialist gynaecologist’ always had referral required ‘yes’, tests provided level ‘as part of the consultation’ could never appear with consultation type ‘telehealth’.

Designed experiment

A generator-developed design was used.16 There were 640 choice sets in total, each with two unlabelled options, and respondents were forced to choose one of the options. These 640 choice sets were divided into 40 versions of 16 choice sets each. To avoid respondents always using one attribute to make the decision, there were two choice sets in each version in which the levels of one of the attributes were the same in both options. As there are 7 attributes, this accounts for 14 choice sets in each version. The final pair of choice sets had different levels in the two options for all of the attributes. We also imposed the following restrictions to ensure plausibility: if consultation type is ‘telehealth’, then tests must be ‘delivered at a local pathology/imaging service’; if healthcare professional is ‘own GP’, then referral must be ‘no referral needed’, and if the abortion type is ‘surgical and is provided in a public clinic’, the OOP cost is ‘A$0’. We ensured that each level of each attribute appeared at least once in each version. Further details are provided in Section 2 of the Supplementary material.

Each respondent was randomly assigned to one of the 40 versions, and the 16 choice tasks within that version were presented in random order.

Survey design

We used an online survey, written using SurveyEngine GmbH software, to collect the data. When respondents opened the survey, they saw an explanation of the research study, followed by definitions and descriptions of EMA and surgical abortion. If the respondent consented to be part of the study, survey questions were presented to them in four sections. Section 1 included sociodemographic questions. Section 2 included questions about respondents’ experience with, and attitudes towards, abortion. This included a screening question which asked participants ‘Is abortion always wrong?’. Those who chose ‘yes’ were screened out, whereas those who chose either ‘no’ or ‘unsure’ were able to continue with the survey. The DCE was presented to respondents in Section 3. A vignette asking respondents to imagine they were helping their local health service plan for the future provision of abortion services served as the introduction to the choice tasks (Box 1). An example of the full survey is provided in Section 10 of the Supplementary material.

| Box 1. Vignette before choice tasks |

| Your task |

| For the purposes of the study, we will ask you to imagine that you are helping your local health service plan the future provision of abortion services that would best meet women’s needs. |

| You will be shown the profiles of two different abortion options and asked to choose the option you think your local health service should provide. |

| The scenarios we describe in Section 3 are hypothetical and do not represent any particular abortion services provided in Australia. |

| You will be asked to do this on 16 different occasions. Please remember there are no right or wrong answers, we are simply interested in your opinions. |

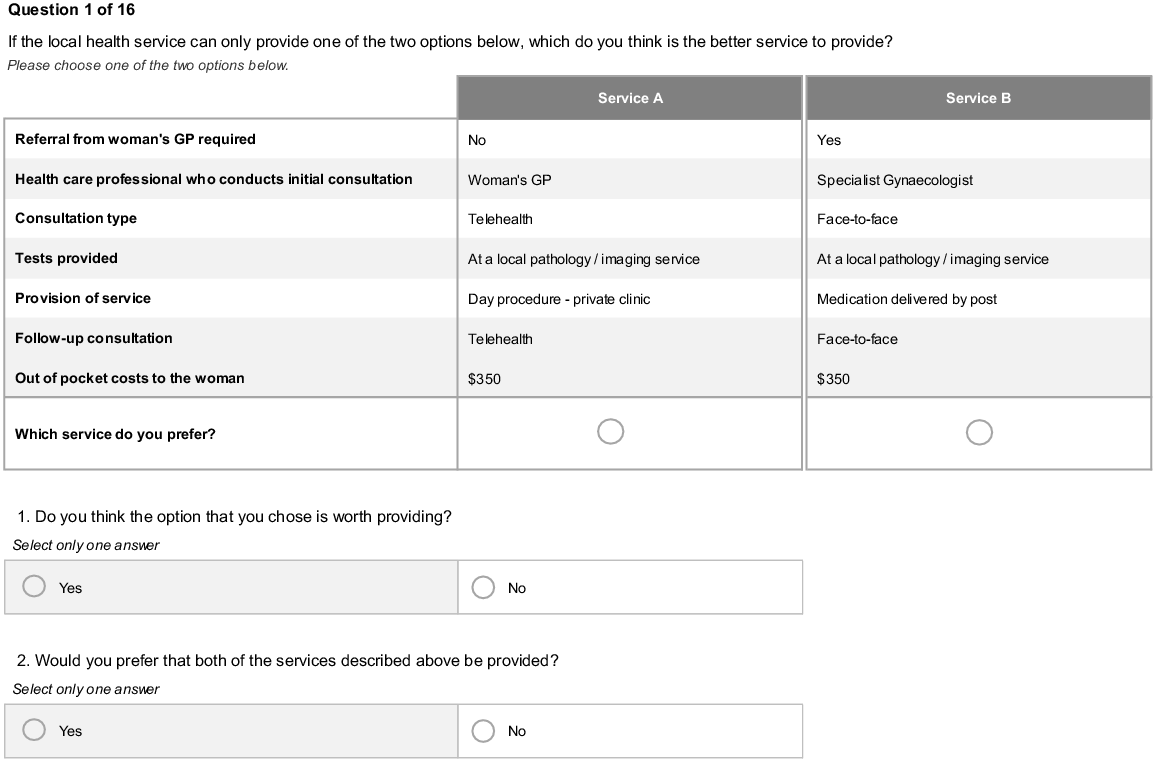

Each respondent was then asked to complete 16 choice tasks. The question respondents were asked was, ‘Which service do you think your local health service should provide? Please choose from one of the two options below.’ After each choice task, the respondents were asked to answer yes or no to the following questions: ‘Do you think the option that you chose is worth providing?’ and ‘Would you prefer that both of the services described above be provided?’. Fig. 1 gives an example of a choice task.

Choice task presented to respondents. Respondents were shown 16 choice tasks and asked to choose between the two options presented along with two follow-up questions about their choice.

The full survey was first piloted using a convenience sample of researchers with a special interest in DCEs. All feedback was incorporated, and once the survey was live, a second pilot of 150 responses from the general public was collected to check for survey flow and logic before the full sample was collected. As no issues were found, the full survey was collected using the same survey.

In the final section of the survey, respondents were asked to rate how difficult they found the choice tasks on a 5-point scale from extremely easy to extremely difficult. To gain additional information about the importance of specific characteristics of abortion services, respondents were also asked: ‘When making your choice, which factor was most important, and which factor was least important to you?’. Respondents saw two drop-down boxes listing all the attributes included in the choice tasks. A final question asked respondents if there were any other features of abortion services that would have influenced their decision that were not included in the choice tasks. Internal validity was tested by reviewing nonsensical answers to open text questions and assessing follow-up questions.

There are various approaches to determining the required sample size for a DCE, as summarised by de Bekker-Grob et al.;17 we chose to collect at least 20 responses per choice set, as this has been shown to give an acceptable estimate of the standard errors.18 Recruitment of participants was undertaken using an online panel provider (Pureprofile), and the sample was chosen to be representative of the Australian general population using quotas based on age and gender. To reflect Australian general population preferences for service delivery, the inclusion criteria were adults aged ≥18 years living in Australia (see Supplementary material Section 3 for further details). Men were included in our sample, as the World Health Organization supports the involvement of partners, friends and family members in reproductive health decisions.4 Respondents were asked to consent to undertaking the survey and could exit at any point. Respondents were compensated for their time by the panel provider once they completed the survey. Data for the final DCE were collected in September 2021. Ethics approval was granted by the University of Technology Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC Reference No. ETH18-2507).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics, including respondents’ socioeconomic and demographic characteristics, and experience with abortion, and all choice models, were analysed using R version 4.1.2.19

Responses to the choice tasks were initially analysed using a multinomial logit (MNL) model, which assumes that all respondents have the same preferences. A MNL model was also fitted to subgroups of the population based on gender, experience with abortion, urban/rural classification and age groups. The models were tested for right or left side bias, but as none was evident, all responses were included in the final model. To further allow for preference heterogeneity, a mixed logit model (MIXL) was used, as it allows for preferences to vary across individuals, and can account for correlation between parameters and between responses from the same individual.20 The final MIXL models included cost as both continuous (Model 1) and categorical (Model 2) variables, using the values presented to respondents, and with each model estimated using 2000 Sobol draws using the ‘logitr’ package.21 Both models used dummy coding, and specified all levels of all attributes as random and independent parameters apart from cost when it was included as a continuous variable. Positive coefficients indicate a preference for that attribute level over the base case level, and negative coefficients indicate attribute levels that are less attractive than the base case level for that attribute. Service delivery, including both medical and surgical abortion, were estimated as one attribute. Predictive analysis was conducted using the results from Model 2 to estimate the predicted probability of each attribute level, with all other attribute levels held constant. Further details about the models are provided in Section 4 of the Supplementary material.

The follow-up questions to the choice tasks that asked respondents whether their preferred choices should be provided were analysed using a probit model. The feedback question that asked respondents to list the most and least important attributes was analysed using a count analysis for each attribute. We collated the open-ended responses to the feedback questions regarding whether any factors were missing from the survey. A checklist for reporting of DCEs in health is reported in the Supplementary material (Section 9, Table S9).

Results

Respondents

A total of 821 respondents with complete responses to the final version of the survey were collected. Responses were analysed to flag non-engaged respondents (e.g. who sped through the survey, only chose the right-hand or left-hand side option from each choice set (straight-line choices) or gave nonsensical responses to open text or feedback questions). Speeders were defined as having a completion time less than one-third of the median completion time (median 9.1 min). There were seven speeders and five respondents who made straight-line choices. As respondents flagged as not being engaged with the survey were not significantly different in terms of their demographic characteristics from engaged respondents, all respondents were included in the final sample. The respondents were representative of the Australian population in terms of age, gender, and proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. However, the sample included more respondents born in Australia, and more with higher education and income levels than the Australian population (see Section 5, Table S4, Supplementary material).

Experience with abortion

Overall, 198 respondents (24%) answered ‘yes’ to the question ‘Have you or any of your sexual partners ever had an abortion?’. A further 30 respondents (3.7%) stated they would ‘prefer not to say’. Of the 198 respondents who had experience with abortion, 112 (57%) were men, 85 (43%) were women and 1 (1%) respondent was ‘other’. The type of abortion experienced by respondents was mostly surgical (72%); 26% reported experience with medical abortion, and 2% preferred not to say. The reason for the abortion/s was mainly unintended pregnancy (86%), followed by foetal abnormality (6%; Table 2).

| Participants with abortion experience (n = 198) | Males (n = 112) | Females A (n = 86) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| What method of abortion was available? n (%) | ||||

| Surgical abortion | 137 (69.2) | 80 (71.4) | 57 (66.3) | |

| Medical abortion | 27 (13.6) | 11 (9.8) | 16 (18.6) | |

| Both | 34 (17.2) | 21 (18.8) | 13 (15.1) | |

| How many abortions have you or your partner had? n (%) | ||||

| One | 146 (73.7) | 77 (68.8) | 69 (80.2) | |

| Two | 33 (16.7) | 22 (19.6) | 11 (12.8) | |

| More than two | 13 (6.6) | 10 (8.9) | 3 (3.5) | |

| Prefer not to say | 6 (3.0) | 3 (2.7) | 3 (3.5) | |

| What type of abortion was performed? Bn (%) | ||||

| Surgical abortion | 143 (72.2) | 86 (76.8) | 57 (66.3) | |

| Medical abortion | 51 (25.8) | 26 (23.2) | 25 (29.1) | |

| Prefer not to say | 4 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (4.7) | |

| What was the reason for the abortion? n (%) | ||||

| Unintended pregnancy | 169 (85.4) | 101 (90.2) | 68 (79.1) | |

| Fetal abnormality | 13 (6.6) | 4 (3.6) | 9 (10.5) | |

| Other | 14 (7.1) | 7 (6.3) | 7 (8.1) | |

| Prefer not to say | 2 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.3) | |

| When was the abortion performed? n (%) | ||||

| Before 13 weeks of pregnancy | 159 (80.3) | 98 (87.5) | 61 (70.9) | |

| At 13 weeks of pregnancy or later | 22 (11.1) | 9 (8.0) | 13 (15.1) | |

| Not sure | 17 (8.6) | 5 (4.5) | 12 (14.0) | |

| Prefer not to say | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Where did you obtain information about the abortion? n (%) | ||||

| Online | 16 (8.1) | 12 (10.7) | 4 (4.7) | |

| Sex education at school | 2 (1.0) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (1.2) | |

| Family member/s or friend/s | 15 (7.6) | 7 (6.3) | 8 (9.3) | |

| Partner | 3 (1.5) | 3 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| GP | 99 (50.0) | 52 (46.4) | 47 (54.7) | |

| Pharmacy | 6 (3.0) | 5 (4.5) | 1 (1.2) | |

| Sexual health/family planning clinic | 37 (18.7) | 18 (16.1) | 19 (22.1) | |

| Telephone service | 14 (7.1) | 11 (9.8) | 3 (3.5) | |

| Other | 6 (3.0) | 3 (2.7) | 3 (3.5) |

Results of the analysis of the choice tasks

The results from the two MIXL models (one specified with cost continuous and one specified with cost categorical) used to analyse the choice tasks are presented in Table 3. Both models showed that respondents had strong preferences for early abortion services in which the initial consultation is delivered by a specialist gynaecologist rather than their regular GP. There were no differences in preferences between a specialised GP and their own GP, but respondents preferred not to have the initial consultation with a nurse practitioner (NP). They also preferred face-to-face rather than telehealth consultations, and for any necessary pre-procedure tests to be conducted at the time of the consultation rather than at a separate appointment with a local pathology/imaging service.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | s.d. | Coefficient | s.d. | ||

| Mean (s.e.) | Mean (s.e.) | Mean (s.e.) | Mean (s.e.) | ||

| Referral from woman’s GP required (base: Yes) | |||||

| No | −0.07 (0.04) | 0.57 (0.05)*** | −0.07 (0.05) | 0.73 (0.06)*** | |

| Health professional who conducts initial consultation (base: woman’s GP) | |||||

| Specialised GP | 0.004 (0.05) | 0.24 (0.14) | 0.02 (0.06) | 0.11 (0.26) | |

| Nurse practitioner | −0.49 (0.06)*** | 0.81 (0.07)*** | −0.57 (0.07)*** | 0.93 (0.09)*** | |

| Specialist gynaecologist | 0.21 (0.05)*** | 0.58 (0.07)*** | 0.37 (0.06)*** | 0.79 (0.09)*** | |

| Consultation type (base: telehealth consultation) | |||||

| Face-to-face consultation | 0.40 (0.04)*** | 0.58 (0.04)*** | 0.47 (0.05)*** | 0.67 (0.05)*** | |

| Tests provided (base: as part of the consultation) | |||||

| At local pathology/imaging service | −0.15 (0.05)** | 0.27 (0.13)* | −0.21 (0.06)*** | 0.44 (0.10)*** | |

| Provision of service (base: day procedure – public clinic) | |||||

| Medication delivered by post | −0.35 (0.06)*** | 0.71 (0.08)*** | −0.53 (0.08)*** | 0.87 (0.10)*** | |

| Medication collected from pharmacy | −0.26 (0.06)*** | 0.47 (0.10)*** | −0.39 (0.07)*** | 0.52 (0.13)*** | |

| Medication collected from doctor’s surgery | −0.01 (0.06) | 0.02 (0.14) | −0.15 (0.07)* | 0.24 (0.15) | |

| Day procedure – private clinic | 0.14 (0.07)* | 0.80 (0.07)*** | 0.07 (0.08) | 0.88 (0.09)*** | |

| Follow-up consultation (base: telehealth) | |||||

| Face-to-face | 0.19 (0.03)*** | 0.61 (0.04)*** | 0.23 (0.04)*** | 0.75 (0.05)*** | |

| OOP costs to the woman (continuous) | 0.003 (0.0001)*** | – | – | – | |

| OOP costs to the woman (base: A$0) | |||||

| A$350 | – | – | −1.03 (0.06)*** | 0.37 (0.13)** | |

| A$580 | – | – | −2.10 (0.09)*** | 1.17 (0.09)*** | |

| A$775 | – | – | −3.40 (0.14)*** | 2.39 (0.14)*** | |

| Log likelihood | −7015 | −6748 | |||

| AIC | 14,075 | 13,551 | |||

s.d. standard deviation; s.e., standard error; AIC, Akaike information criterion; OOP, out-of-pocket; GP, general practitioner. Statistical significance: *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001.

Not surprisingly, respondents favoured lower-cost services. The need for a referral from their GP, if required, was not a significant factor in respondents’ choices. In terms of the provision of EMA, respondents preferred to collect the medication from a doctor’s surgery rather than from a pharmacy or delivered by post. If the only delivery options were pharmacy or post, pharmacy is preferred. The relative attribute importance was also calculated; OOP costs (54%), health professional (15%) and service delivery (14%) were the most important attributes (see Section 7 of Supplementary material for details).

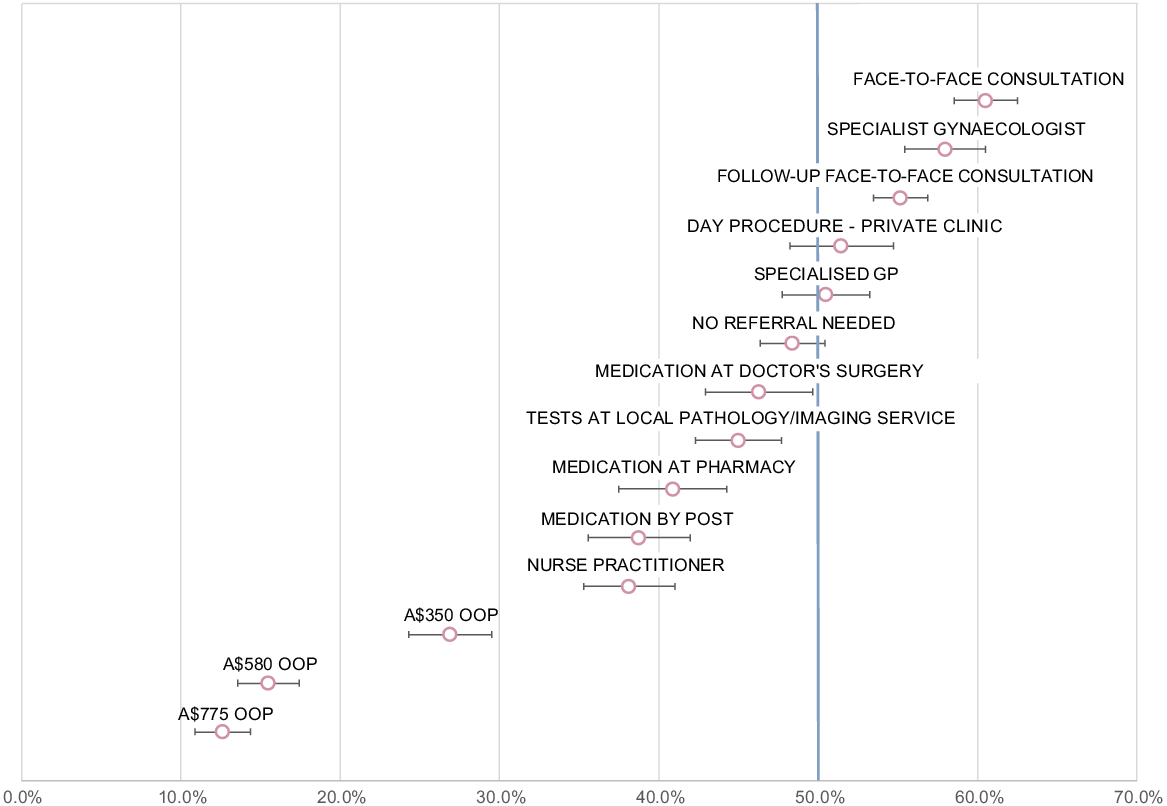

Predicted probabilities

Fig. 2 presents the predicted probabilities for each attribute level using estimates from MIXL Model 2. The figure shows that respondents were more likely to choose an option with face-to-face consultations over telehealth consultations, and options with a specialist gynaecologist over consultations with a GP. Respondents were equally content with an initial consultation provided by either their own GP or a specialised GP, but preferred not to have consultations with a NP. Surgical abortion (either in a public or private clinic) was preferred to EMA. For EMA, medication provided at the doctor’s surgery was preferred to postal delivery or collection at the pharmacy. Scenarios with higher costs were significantly less likely to be chosen as the preferred service.

Predicted probabilities of abortion services. The probabilities are the probability of the service being chosen when it differs from the base service only for the listed level, relative to the service with all levels at the base level. The base levels are: referral from woman’s GP required, consult with woman’s GP, telehealth consultation, test at consultation, day procedure in public clinic, follow-up by telehealth and A$0 out of pocket costs to the woman.

Subgroup analyses

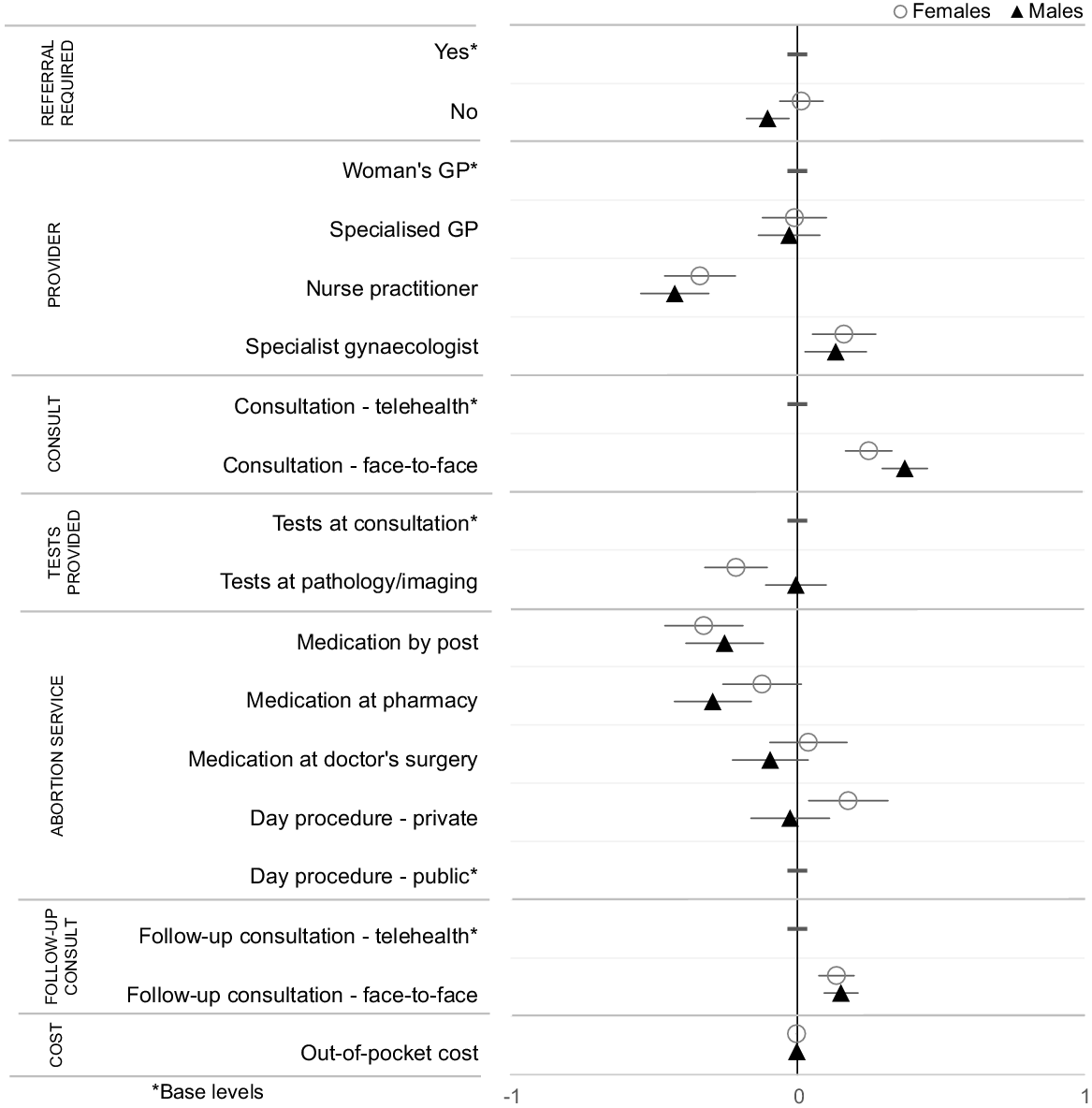

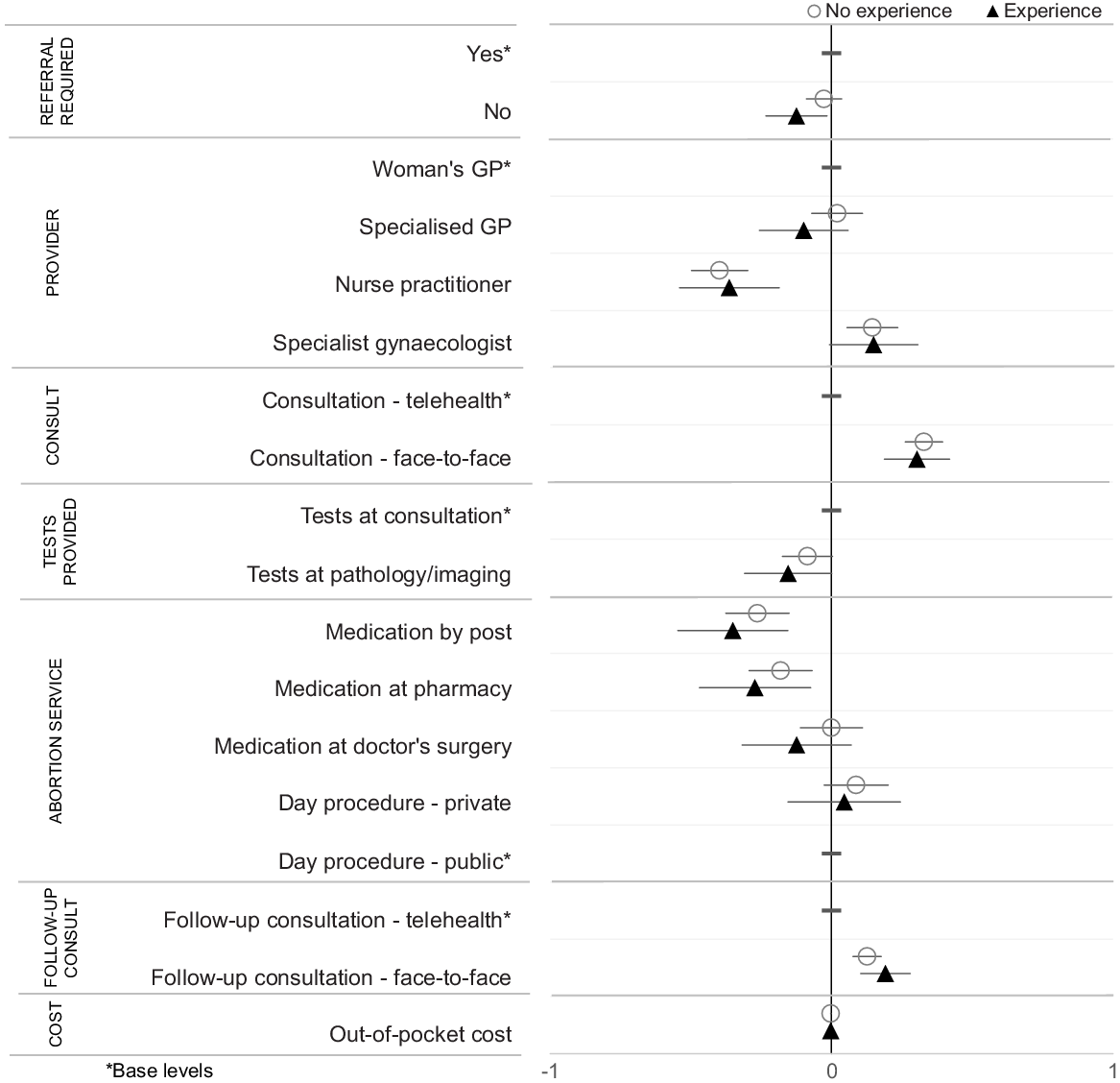

Additional multinomial logit model models were run to test for differences by gender, age, urban/rural location and experience with abortion. Overall, there were few differences between men and women (Fig. 3). There were no notable differences in preferences between those with and without experience of abortion (Fig. 4). The results for the urban/rural classification and age groups are presented in Section 6 of the Supplementary material. Respondents from urban and rural locations had similar preferences, although those in rural locations had stronger preferences for tests to be provided at the doctor’s surgery rather than at a pathology or imaging centre. Preferences for those of reproductive age (<45 years) differed in terms of being more accepting of services where medication is delivered in the post and of telehealth consultations than older respondents (≥45 years).

Preferences for abortion services by gender. Coefficients to the right of the 0 line indicate preferences above the base level for that attribute; coefficients to the left indicate a preference below the base level. Overlapping confidence intervals between the groups indicate preferences that are not statistically significantly different.

Preferences for abortion services by experience with abortion. Coefficients to the right of the 0 line indicate preferences above the base level for that attribute; coefficients to the left indicate a preference below the base level. Overlapping confidence intervals between the groups indicate preferences that are not statistically significantly different.

Follow-up questions after choice tasks

Approximately 64% of respondents (n = 522) answered ‘yes’ to both follow-up questions, indicating that they thought the option they chose was worth providing, and that both services should be provided. In those choice tasks where every respondent indicated that the service was worth providing, the preferred options were either zero or low cost. The results of the probit model mirror those of the choice tasks in the DCE, indicating strong preferences for face-to-face consultations provided by a specialist gynaecologist. There were low levels of support for services where medication was delivered by post, consultations were with a NP and OOP costs were high. A table of these results is presented in the Supplementary material (Section 6, Table S5).

Feedback questions at end of the survey

Responses to the question regarding which factors were most or least important when making choices between the abortion options indicated that cost (36.4%) was the most important factor, followed by type of healthcare provider (16.3%). The type of follow-up consultation and location of tests were not as important to respondents (Table 4). A crosstabulation of all responses can be found in the Supplementary material (Section 8, Table S7).

| Most important attribute (n = 821) | Least important attribute (n = 821) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Referral from GP | 127 (15.5) | 161 (19.6) | |

| Healthcare provider | 134 (16.3) | 57 (6.9) | |

| Consultation type | 123 (15.0) | 87 (10.6) | |

| Where tests are provided | 26 (3.2) | 157 (19.1) | |

| Where service is provided | 92 (11.2) | 68 (8.3) | |

| Type of follow up | 20 (2.4) | 163 (19.9) | |

| Cost | 299 (36.4) | 128 (15.6) |

The final feedback question asked respondents if there were any factors not included in the choice tasks that they considered important in their decision making. Overall, 71% (n = 586) of respondents provided feedback, with 44% (n = 363) stating that all relevant factors were included, 4% (n = 30) were unsure and the remaining 21% (n = 169) offering suggestions for other factors. Respondents’ suggestions included: mental health support/counselling (n = 30); privacy/non-judgemental (n = 14); accessibility/ease/convenience (n = 13); choices/flexible model (n = 12); waiting times/number of visits (n = 11); location of clinic/proximity (n = 8); safety (n = 4) and gender of health professional (n = 3; Supplementary material, Section 8, Table S8).

Discussion

This is the first Australian study to ask the general public about their preferences regarding the organisation and delivery of early abortion services. The results provide new insights into consumers’ views, which can inform clinical and health policy. Experience of EMA is low among Australians; 72% (n = 593) of respondents who reported having experience with abortion were referring to surgical abortion. As those with experience of EMA report high levels of satisfaction with both telehealth and in-clinic services, provider interaction, and would recommend the service to a friend,22 factual information about EMA needs to be available and widely disseminated. Baraitser et al. showed that providing choices in terms of the type of abortion and place of delivery is important.12 Most of our respondents indicated that both options presented to them in each choice task should be provided. As some countries are limiting access to surgical abortion in favour of prescribing EMA, these results point to the importance to Australians of having both medical and surgical abortions available.

Respondents preferred a specialist gynaecologist for the initial consultation. This may be because they are unsure whether GPs are knowledgeable regarding the provision of EMA, or, for reasons of choice, believe that gynaecologists are trained to provide both EMA and surgical abortion. Similar uncertainty may explain the lack of preference for NPs, although information was provided emphasising the expertise of NPs. This indicates the need for community education emphasising the skills and experience of NPs, including in the provision of EMA. Recent changes to the Therapeutic Goods AdministrationA has expanded EMA provision beyond doctors,23 and the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory CommitteeB has endorsed its provision by NPs and eligible midwives. However, state-based legislative changes and MedicareC funding are still required to enable NPs and midwives to provide EMA.24

A desire for convenience and confidentiality is likely to underlie respondents’ preferences for imaging/pathology tests to be undertaken during the initial consultation and for medications to be available from the doctor’s surgery, and doing this would likely improve the uptake of EMA. This also facilitates tests to determine eligibility for EMA given the time-sensitive nature of abortion services. Education for providers is necessary to ensure they follow evidence-based guidelines and avoid unnecessary procedures (e.g. repeat ultrasounds). Rural respondents had a higher preference for receiving tests at the doctor’s surgery, indicating the need to streamline abortion services in this setting. All respondents preferred face-to-face follow up. This may not be easy in a rural setting. A study of home-based EMA follow-up protocols, involving urine tests and telephone follow up, has demonstrated its safety and effectiveness.25 Community education regarding the safety and efficacy of these home-based services could play a pivotal role in boosting the uptake of telehealth services.

It is encouraging that respondents aged <45 years were happy to receive their medication by post and to consult with healthcare professionals using telehealth, and highlights the importance of designing health services with input from those most likely to use the service. Issues relating to privacy, the reliability of the postal service and/or the ongoing stigma of having an abortion are likely to be behind respondents’ preferences to collect medication from a doctor’s surgery. Currently, GPs are unable to stock items on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme, highlighting an access barrier.

Reducing costs will also improve access to abortion services. In terms of relative attribute importance, cost accounted for >50%, and approximately one-third of respondents listed cost as the most important attribute. Lower-cost services to patients can be achieved by providing surgical abortion in a public clinic, and, for both surgical abortion and EMA, using Medicare rebates only. These findings are in line with previous qualitative research showing that cost is an important consideration for women seeking abortion.8,26 Previous research has recommended the use of telehealth services as a means of reducing both the need to travel and costs. Our results, however, indicate that rural women prefer face-to-face consultations, which may stem from a lack of familiarity with telehealth services. This underscores the need for enhanced education, to emphasise that the success rates and safety outcomes of telehealth abortion services are similar to abortion care in clinics.

This study had a number of strengths and novel features. We recruited a large, generally representative, in terms of age and gender, sample of the Australian general population. One-quarter of the sample included people who had previous experience with abortion (n = 198). Testing for engagement and consistency found that >90% of respondents were engaged with the DCE and consistent in their responses. The research also had some limitations. Although both the literature and expert opinion from relevant health professionals were used to inform the development of the attributes and levels, all DCE are limited by the small number of attributes that it is practical to include. Although generally representative of the Australian population, the sample was better educated, and few were from culturally and linguistically diverse communities. Additionally, respondents who had experience with abortion >13 weeks’ gestation may have based their responses on their experiences with surgical abortion.

A large percentage (71%; n = 586) of respondents provided feedback, with 44% (n = 363) stating that all relevant attributes were included. Many respondents reaffirmed the importance of some factors that were already presented in the choice tasks, such as comments relating to cost/affordability/Medicare rebates (n = 39), face-to-face consultations (n = 21), no medication by mail or pharmacy pick-up (n = 6) and consultations only with specialists or GPs (n = 10).

Conclusion

The findings of this study underscore the need for a range of abortion services to be available, and the importance of involving community perspectives in the design of such services. Although EMA and telehealth services represent alternate avenues for abortion care, it is essential to continue to offer face-to-face consultations and surgical abortion. Reducing the cost to consumers of abortion services will increase accessibility, particularly for remote and underserved communities. Overall, there is a pressing need for increased education and awareness among community members regarding the types of abortion available, and the range of healthcare providers capable of delivering safe and effective abortion services.

Data availability

The dataset used and analysed during the current study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declaration of funding

This research was undertaken as part of the SPHERE Centre of Research Excellence in Sexual and Reproductive Health for Women in Primary Care, funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council (Project number APP1153592).

Author contributions

JC, MH, DJS, DB and DM were all involved in the conceptualisation of the research and drafting of the manuscript. JC, DJS and MH conducted the online survey, statistical analysis and interpretation of the results. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the feedback received from the DCE interest group at Centre for Health Economics Research and Evaluation, in particular, Patricia Kenny, for her comments on the statistical analysis.

References

1 Taft AJ, Shankar M, Black KI, Mazza D, Hussainy S, Lucke JC. Unintended and unwanted pregnancy in Australia: a cross-sectional, national random telephone survey of prevalence and outcomes. Med J Aust 2018; 209(9): 407-8.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

2 Keogh LA, Gurrin LC, Moore P. Estimating the abortion rate in Australia from national hospital morbidity and pharmaceutical benefits scheme data. Med J Aust 2021; 215(8): 375-6.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

3 Wright SM, Bateson D, McGeechan K. Induced abortion in Australia: 2000–2020. Ashfield, Australia: Family Planning NSW; 2021. Available at https://www.fpnsw.org.au/sites/default/files/assets/Induced-Abortion-in-Australia_2000-2020.pdf [cited 15 August 2024]

4 WHO. Abortion care guideline. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022. Available at https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240039483 [cited 30 September 2024]

5 Popinchalk A, Sedgh G. Trends in the method and gestational age of abortion in high-income countries. BMJ Sex Reprod Health 2019; 45(2): 95-103.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

6 SPHERE Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health Coalition. Fact Sheets. Melbourne, Australia: SPHERE CRE; 2023. Available at https://www.spherecre.org/resources/fact-sheets [cited 15 October 2024]

7 Mazza D, Burton G, Wilson S, Boulton E, Fairweather J, Black KI. Medical abortion. Aust J Gen Pract 2020; 49(6): 324-30.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

8 Mazza D. Increasing access to women’s sexual and reproductive health services: telehealth is only the start. Med J Aust 2021; 215(8): 352-3.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

9 RANZCOG. Clinical Guideline for Abortion Care: An evidence-based guideline on abortion care in Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand. Melbourne, Australia: Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists; 2023. Available at https://ranzcog.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/Clinical-Guideline-Abortion-Care.pdf [cited 15 August 2024]

10 Haas M, Church J, Street DJ, Bateson D, Mazza D. How can we encourage the provision of early medical abortion in primary care? Results of a best–worst scaling survey. Aust J Prim Health 2023; 29(3): 252-9.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

11 Endler M, Lavelanet A, Cleeve A, Ganatra B, Gomperts R, Gemzell-Danielsson K. Telemedicine for medical abortion: a systematic review. BJOG 2019; 126(9): 1094-102.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

12 Baraitser P, Free C, Norman WV, Lewandowska M, Meiksin R, Palmer MJ, et al. Improving experience of medical abortion at home in a changing therapeutic, technological and regulatory landscape: a realist review. BMJ Open 2022; 12(11): e066650.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

14 Louviere JJ, Flynn TN. Using best-worst scaling choice experiments to measure public perceptions and preferences for healthcare reform in australia. Patient 2010; 3(4): 275-83.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

15 MSI Australia. Safe abortion services in Australia. Melbourne, Australia: MSI Australia; 2024. Available at https://www.msiaustralia.org.au/abortion-services/ [cited 2024 Aug 15]

16 Street DJ, Burgess L. The construction of optimal stated choice experiments: theory and methods. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons; 2007. 10.1002/9780470148563

17 de Bekker-Grob EW, Donkers B, Jonker MF, Stolk EA. Sample size requirements for discrete-choice experiments in healthcare: a practical guide. Patient 2015; 8(5): 373-84.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

18 Burgess L, Street DJ, Wasi N. Comparing designs for choice experiments: a case study. J Stat Theory Pract 2011; 5(1): 25-46.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

19 R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria; 2023. Available at https://www.R-project.org/

20 Train K. Discrete choice methods with simulation. Cambridge University Press; 2009. Available at https://eml.berkeley.edu/books/choice2.html

21 Helveston JP. logitr: fast estimation of multinomial and mixed logit models with preference space and willingness-to-pay space utility parameterizations. J Stat Soft 2023; 105(10): 1-37 Available at https://www.jstatsoft.org/index.php/jss/article/view/v105i10 [cited 15 August 2024].

| Google Scholar |

22 Thompson TA, Seymour JW, Melville C, Khan Z, Mazza D, Grossman D. An observational study of patient experiences with a direct-to-patient telehealth abortion model in Australia. BMJ Sex Reprod Health 2022; 48(2): 103-9.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

23 Therapeutic Goods Administration. Amendments to restrictions on prescribing MS-2 Step (mifepristone and misoprostol). Canberra, Australia: Australian Government, Department of Health and Aged Care; 2023. Available at https://www.tga.gov.au/news/media-releases/amendments-restrictions-prescribing-ms-2-step-mifepristone-and-misoprostol [cited 15 August 2024]

24 The Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. Recommendations made out-of-session by the PBAC between meetings (March 2023 and July 2023). Canberra, Australia: Commonwealth of Australia; 2024. Available at https://www.pbs.gov.au/industry/listing/elements/pbac-meetings/pbac-outcomes/out-of-session/items-recommended-between-meetings-OOS-Mar23-Jul23-v2.pdf [cited 15 August 2024]

25 Melville C, Goldstone P, Moosa N. Telephone follow-up after early medical abortion using Australia’s first low sensitivity urine pregnancy test. Aust NZJ Obstet Gynaecol 2023; 63: 797-802.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

26 Mazza D, Seymour JW, Sandhu MV, Melville C, Brien JOR, Thompson TA. General practitioner knowledge of and engagement with telehealth-at-home medical abortion provision. Aust J Prim Health 2021; 27(6): 456-61.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Footnotes

A The Therapeutic Goods Administration is a regulatory body within the Australian Government Department of Health that is responsible for evaluating therapeutic goods (medical devices, medicines and biologicals) to ensure they are healthy, safe and effective (tga.gov.au).

B The Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee is an independent expert committee that advises the Australian Government on which medicines should be subsidised under the pharmaceutical benefits scheme (pbac.pbs.gov.au).

C Medicare is the publicly funded universal health insurance scheme in Australia (health.gov.au/topics/medicare).