Comparing the impact of sexualised drug use with and without chemsex on sexual behaviours among men who have sex with men in China: a national multi-site cross-sectional study

Jiajun Sun A B , Bingyang She C , Phyu M. Latt A B , Jason J. Ong

A B , Bingyang She C , Phyu M. Latt A B , Jason J. Ong  A B , Xianglong Xu A B D , Yining Bao A B C , Christopher K. Fairley

A B , Xianglong Xu A B D , Yining Bao A B C , Christopher K. Fairley  A B , Lin Zhang E F , Weiming Tang

A B , Lin Zhang E F , Weiming Tang  G H * and Lei Zhang

G H * and Lei Zhang  A B C *

A B C *

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

Abstract

Sexualised drug use (SDU) is common in men who have sex with men (MSM). Chemsex, a form of psychoactive SDU, is a strong risk factor for sexually transmitted infections (STIs). We investigated the associations of SDU and chemsex with the sexual behaviours in Chinese MSM.

From 23 March 2022 to 22 April 2022, we recruited participants (male, >18 years old) via WeChat across five Chinese cities to an online cross-sectional survey on sexual behaviour preferences, pre-exposure prophylaxis, SDU, and chemsex. One-way ANOVA and chi-squared tests were used to compare sexual behaviour patterns across the groups.

We included the responses from 796 eligible participants, who were aged 18–70 years, and mostly single. Three groups of participants were identified, the largest was the ‘non-SDU group’ (71.7%), followed by the ‘SDU without chemsex’ group (19.7%), and the ‘chemsex’ group (8.5%). Poppers (8.4%) were the most used drugs in the ‘chemsex’ group. The ‘chemsex’ group also had the highest number of sexual partners, and reported the highest frequency of self-masturbation (38.2%). The ‘chemsex’ group also exhibited the highest Shannon diversity index value of 2.32 (P = 0.03), indicating a greater diversity of sexual acts. For sequential sex act pairs, the ‘chemsex’ group was more likely to self-masturbate than perform receptive oral sex, perform receptive oral sex than self-masturbate, being masturbated or perform receptive oral sex than being rimmed by another man.

Our findings identify the urgent need for targeted HIV/STI interventions for MSM who practice chemsex.

Keywords: chemsex, cross-sectional study, men who have sex with men, sequential sexual acts, sexual behaviours, sexual diversity, sexual transmitted infection, sexualised drug use.

Introduction

Sexualised drug use (SDU) refers to the use of illicit substances in the context of sexual intercourse.1 SDU often involves the use of substances such as methamphetamine, GHB/GBL (gamma-hydroxybutyrate/gamma-butyrolactone), and cocaine, which are used to enhance sexual experiences, prolong sexual activity, or reduce inhibitions.1 Previous research2–4 indicates that lifetime SDU, particularly when initiated at a younger age or sustained over a prolonged period, can have lasting impacts on behaviour patterns, including those related to sexual activity. These patterns may persist due to the long-term psychological and behavioural correlations of SDU, such as increased risk-taking and altered decision making in sexual contexts.5 We hypothesise that individuals with a history of SDU may exhibit different sexual behaviours compared to those without such a history, even if the SDU occurred earlier in their lives.

In contrast, chemsex is a subcategory of SDU with a specific choice of substances that aims to prolong sexual arousal.6 The choice of chemsex drug is typically methamphetamine but can include other drugs such as mephedrone, GHB/GBL, ketamine, or alkyl nitrates.7 Chemsex is commonly practised in men who have sex with men (MSM), as well as bisexual and transgender individuals, where it is often associated with group sex and other high-risk sexual behaviours.8

Research indicates that chemsex is more prevalent among MSM compared to their heterosexual counterparts.9–11 A study in Norway indicated that the percentage of MSM who have participated in chemsex in the past year was 17%, considerably higher than their heterosexual counterparts (12%).12 Additionally, research on chemsex prevalence among MSM has shown significant variability, with estimates ranging from 3% to 29%, which is likely to be because of differences in sampling, measurements, and recruitment methods.10 In a cross-sectional study in China in 2018, 82 (14.1%) and 37 (6.4%) of gay, bisexual, and other MSM reported engaging in SDU and chemsex, respectively, in the past year.13 Additionally, a study from Hong Kong found that the proportion of MSM participants involved in chemsex during the past 6 months increased from 7.3% in 2018 to 8.6% in 2020,14 highlighting a rising trend in chemsex participation in China.

The practice of chemsex poses public health concerns due to its association with an increased risk of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including HIV.15,16 The combination of euphoria-heightened sexual arousal and increased physical stamina that chemsex offers often leads to prolonged sexual encounters with multiple partners, during which protective measures such as condom use may be neglected.10,11 Studies have shown that individuals engaging in chemsex are more likely to participate in high-risk sexual practices, such as condomless anal intercourse, fisting, and group sex, compared to those who do not use drugs in sexual contexts.10 Sustained use can lead to diminished responsiveness and risk judgment capabilities.17 Chemsex not only elevates the risk of STIs but also has broader socio-psychological implications, including diminished decision making capabilities and impaired judgement, which can further perpetuate the cycle of risky sexual behaviour.18

Considering these concerns, our study investigates the impact of SDU, particularly chemsex, on sexual behaviour, HIV/STI infection risk, and the use of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among MSM communities across China. We conducted a cross-sectional survey, stratifying participants into three groups based on their SDU status. By examining these factors, our research aimed to provide a clearer understanding of how SDU influences sexual health outcomes within this population and to inform targeted interventions.

Materials and methods

Study population

We conducted an anonymous cross-sectional survey through community organisations and social groups in China from 23 March 2022 to 22 April 2022. National participant recruitment was promoted through multiple platforms across China. Recruitment advertisements were listed on six gay service groups in WeChat public platforms that targets geographically disparate regions in China. These six service groups included Zhuhai Xutong Volunteer Service Centre, Qingdao Qingtong Anti-AIDS Volunteer Service Centre, Nanjing Xingyou Volunteer Service Centre, Jinan Rainbow, Beijing LGBT+, and Positive Peers Group. These groups were dedicated to promoting mass education on HIV/STIs and providing free HIV/STIs counselling and testing services for the gay community. The advertisements provide a general description of the project and include the addresses of health service stations and local Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that provide HIV services.

Participants were eligible for the study if they were 18 years or older, were born male, and had ever had sex with another man in their lifetime. Participants were also required to be able to fill out the questionnaire carefully and truthfully. All participants provided informed consent and voluntarily participated in the study. All research was performed following relevant guidelines and regulations. All eligible participants received a cash reward of RMB20 on completion of the baseline questionnaire and an additional RMB20 on completion of a follow-up questionnaire conducted 1 month after the baseline survey. Furthermore, if a secondary referral successfully completed the questionnaire, both the referring participant and the referred individual each received RMB20.

This study used a consecutive sampling approach where all individuals who met the eligibility criteria during the study period were invited to participate. This approach was chosen to maximise recruitment across our multi-site study locations while minimising selection bias. This study collected specific information on sexual behaviour patterns, SDU, sequential sexual acts in the most recent sexual encounter with another man, and willingness to use PrEP.

Measures of SDU and chemsex

Chemsex was defined as the lifetime use of drugs for sexual purposes, including poppers,9,19,20 crystal meth (also known as ‘Ice’),19,21 ketamine,19,22 ecstasy (MDMA),19,22 or GHB/GBL19,22 in conjunction with sexual activities, categorising participants into the ‘chemsex’ group (see Supplementary material Table S1). Participants who reported a lifetime use of alcohol,1,19,23 erectile dysfunction medication (e.g. Viagra),1,24 marijuana,1,24 or heroin1,24 during sexual activity but did not use chemsex drugs were categorised as the ‘SDU without chemsex’ group (Table S1). Conversely, individuals who did not report SDU were categorised as the ‘non-SDU’ group.

Measures of risk of HIV/STIs

To analyse the association between SDU and the risk of HIV/STIs infection, we used the MySTIRisk tool25 to calculate the HIV/STIs risk score for each participant. MySTIRisk was a prediction tool trained based on the data from the Melbourne Sexual Health Centre (MSHC) in Australia. The tool employed machine learning techniques to generate reliable estimates of the probability of four types of infections, including syphilis, gonorrhoea (NG), chlamydia (CT), and HIV.

The MySTIRisk assessment tool was incorporated into our questionnaire designed for Chinese MSM. The majority of the MySTIRisk questions were directly compatible with our study questionnaire. The MySTIRisk tool calculates the risk scores based on the users’ responses to a series of risk-assessment questions. The model outputs percentage scores ranged from 0 to 1. A higher percentage indicates a greater risk.

Measures of sexual behaviour

We estimated the frequency of sexual acts over the past 12 months for each participant. Participants were asked to recall their most recent sexual encounters and report on 10 specific types of sexual acts they engaged in with male partners. The 10 sexual acts were: (1) French kissing; (2) self-masturbating; (3) masturbating another man; (4) masturbated by a man; (5) receptive oral sex; (6) insertive oral sex; (7) receptive rimming; (8) insertive rimming; (9) receptive anal sex; and (10) insertive anal sex. We assumed that the frequency of these acts remained consistent for each participant, and we calculated the occurrence of each sexual behaviour over the past 12 months.

We also analysed the diversity of sexual behavioural patterns during the most recent sexual encounters using the Shannon diversity index, a metric commonly used in microbiome analysis.26,27 This index helped us characterise the richness and variability of sexual behaviours among participants. We then compared the diversity of sexual behaviours across the ‘chemsex’ group, the ‘SDU’ group, and the ‘non-SDU’ group.

The questionnaire included a question to ask participants the order when the sexual acts occurred in the most recent sexual encounter. Participants were asked to list up to 10 sexual acts in the order they occurred. We defined sexual act pairs as two consecutive sexual acts within this sequence, enabling us to study the patterns of sexual behaviour during a single encounter. By analysing these sexual act pairs, we compared the correlations of chemsex or SDU on sexual behaviour patterns.

To investigate whether SDU affects sexual activity, we calculated the frequency of different sexual behaviours during the last sexual encounter for both the ‘SDU’ and ‘non-SDU’ groups. We then used χ2 analysis to determine whether SDU significantly influences the patterns of sexual behaviour. To control for potential confounding factors, we applied the multivariable logistic regression models that included all socio-demographic variables alongside the independent variables. To evaluate model fit and examine the impact of potential confounders, we compared the univariable and multivariable models using the Akaike Information Criterion,28 Bayesian Information Criterion,29 and χ2 difference tests. For each model comparison, we computed χ2 statistics and corresponding P-values.

Measures of PrEP use

PrEP-naïve participants were those who responded ‘No’ to the question, ‘Have you ever taken PrEP?’. Initiated PrEP participants were those who responded ‘Yes’ to the question, ‘Have you ever taken PrEP?’. For those that initiated PrEP, we further divided the responses into two groups: (1) ‘currently using PrEP’; and (2) ‘stopped using PrEP’. The ‘currently using PrEP’ group answered ‘Yes’ to ‘Are you taking PrEP right now?’. PrEP-naïve participants were further divided into those ‘Interested in PrEP’ and those ‘Not interested in PrEP’.

Statistical analysis

A single-factor ANOVA was used to analyse the risk prediction outcomes, assessing the magnitude of STI risk variables associated with different patterns of SDU. The ANOVA results were evaluated for statistical significance across all groups, ensuring that the analysis captures any differences. Non-parametric tests were used when data violated the homogeneity of variance assumption or did not conform to a normal distribution during the ANOVA process.30 The chi-squared test was employed to perform intergroup statistical comparisons for categorical data. A P-value of 0.05 or less was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using Prism 10, SPSS 26, and Python 3.9.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of study participants

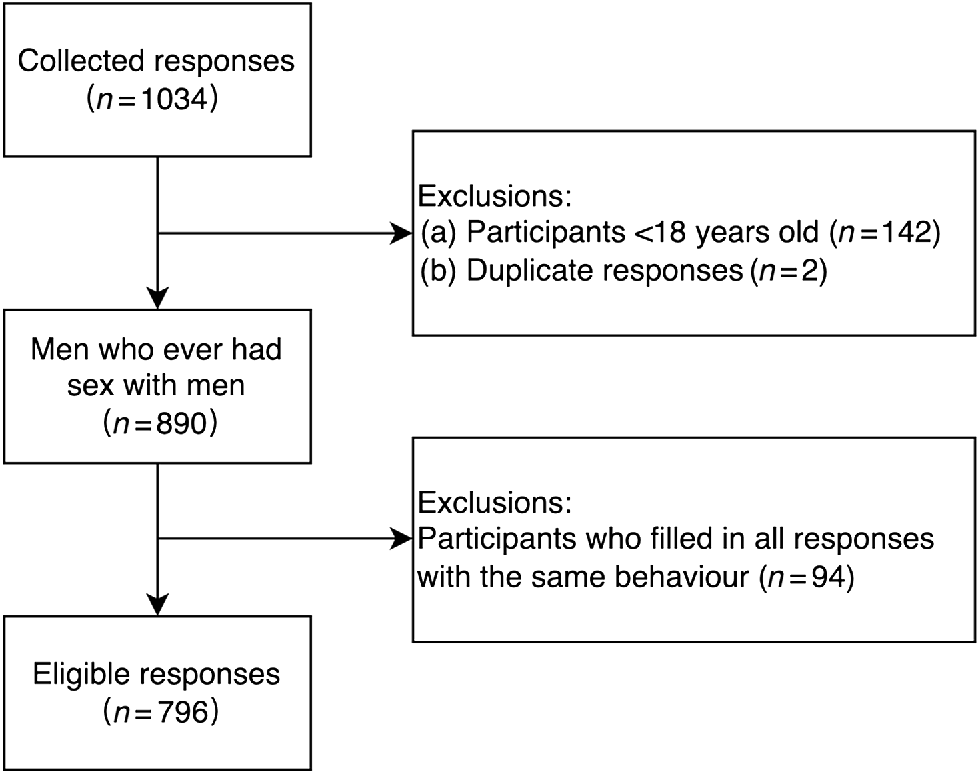

In total, 1034 MSM completed the questionnaires. We excluded 142 because the participants were less than 18 years of age, two questionnaires were duplicates, and 94 had no data reported on sexual behaviour. Thus, we included 796 MSM in our final analysis (Fig. 1).

The demographic characteristics of participants are in Table 1. Of these, 571 participants were classified as non-SDU, while the remaining 225 belonged to the ‘SDU’ groups. Subsequently, 68 participants were categorised into the ‘chemsex’ group, while 157 were classified as SDU without chemsex drugs. Within the ‘chemsex’ group, poppers (n = 67, 8.4%) were the most used drug, followed by ketamine (n = 1, 0.1%) (Table S1). For the ‘SDU without chemsex’ group, most used alcohol (n = 132, 16.6%), followed by erectile dysfunction medication (n = 30, 3.8%), and marijuana (n = 1, 0.1%). Among all participants who use erectile dysfunction medication, 60% were young individuals aged 30 years and under.

| Characteristics | Total (n = 796) | Neither group (non-SDU) (n = 571) | SDU with chemsex (n = 68) | SDU without chemsex (n = 157) | P-value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| Demographic characteristics | ||||||||||

| Age (years) | ||||||||||

| 18–29 | 529 | 66.5 | 379 | 66.4 | 50 | 73.5 | 100 | 63.7 | 0.47 | |

| 30–39 | 201 | 25.3 | 143 | 25.0 | 12 | 17.6 | 46 | 29.3 | ||

| 40–49 | 48 | 6.0 | 34 | 6.0 | 4 | 5.9 | 10 | 6.4 | ||

| 50 and above | 18 | 2.3 | 15 | 2.6 | 2 | 2.9 | 1 | 0.6 | ||

| Education | ||||||||||

| High school or below | 103 | 12.9 | 73 | 12.8 | 6 | 8.8 | 24 | 15.3 | 0.66 | |

| College/Bachelor’s degree | 587 | 73.7 | 425 | 74.4 | 52 | 76.5 | 110 | 70.1 | ||

| Master’s degree or above | 106 | 13.3 | 73 | 12.8 | 10 | 14.7 | 23 | 14.6 | ||

| Income | ||||||||||

| <RMB1500 | 88 | 11.1 | 61 | 10.7 | 7 | 10.3 | 20 | 12.7 | 0.91 | |

| RMB1500–3000 | 100 | 12.6 | 67 | 11.7 | 8 | 11.8 | 25 | 15.9 | ||

| RMB3001–5000 | 200 | 25.1 | 147 | 25.7 | 17 | 25.0 | 36 | 22.9 | ||

| RMB5001–8000 | 213 | 26.8 | 152 | 26.6 | 20 | 29.4 | 41 | 26.1 | ||

| >RMB8001 | 195 | 24.5 | 144 | 25.2 | 16 | 23.5 | 35 | 22.3 | ||

| Marriage | ||||||||||

| Single | 712 | 89.4 | 506 | 88.6 | 64 | 94.1 | 142 | 90.4 | 0.48 | |

| Engaged or married | 50 | 6.3 | 37 | 6.5 | 2 | 2.9 | 11 | 7.0 | ||

| Separated or divorced or widowed | 34 | 4.3 | 28 | 4.9 | 2 | 2.9 | 4 | 2.5 | ||

| Sexual orientation | ||||||||||

| Gay or homosexual | 612 | 76.9 | 440 | 77.1 | 52 | 76.5 | 120 | 76.4 | 0.007 | |

| Bisexual | 156 | 19.6 | 116 | 20.3 | 12 | 17.6 | 28 | 17.8 | ||

| Heterosexual | 3 | 0.4 | 1 | 0.2 | 2 | 2.9 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Unsure/other | 25 | 3.1 | 14 | 2.5 | 2 | 2.9 | 9 | 5.7 | ||

| Disclosure of sexual orientation | ||||||||||

| Yes | 623 | 78.3 | 452 | 79.2 | 56 | 82.4 | 115 | 73.2 | 0.20 | |

| No | 173 | 21.7 | 119 | 20.8 | 12 | 17.6 | 42 | 26.8 | ||

| Residence | ||||||||||

| Guangdong | 356 | 44.7 | 271 | 47.5 | 24 | 35.3 | 61 | 38.9 | 0.13 | |

| Shandong | 128 | 16.1 | 87 | 15.2 | 16 | 23.5 | 25 | 15.9 | ||

| Beijing | 45 | 5.7 | 33 | 5.8 | 2 | 2.9 | 10 | 6.4 | ||

| Hunan | 37 | 4.6 | 21 | 3.7 | 2 | 2.9 | 14 | 8.9 | ||

| Liaoning | 37 | 4.6 | 23 | 4.0 | 5 | 7.4 | 9 | 5.7 | ||

| Jiangsu | 35 | 4.4 | 25 | 4.4 | 4 | 5.9 | 6 | 3.8 | ||

| Other provinces | 158 | 19.8 | 111 | 19.4 | 15 | 22.1 | 32 | 20.4 | ||

| PrEP | ||||||||||

| Initiated PrEP | 144 | 18.1 | 108 | 18.9 | 14 | 20.6 | 22 | 14.0 | 0.29 | |

| Currently using PrEP | 72 | 9.0 | 58 | 10.2 | 5 | 7.4 | 9 | 5.7 | ||

| Stop using PrEP | 72 | 9.0 | 50 | 8.8 | 9 | 13.2 | 13 | 8.3 | ||

| PrEP-naïve | 630 | 79.1 | 447 | 78.3 | 51 | 75.0 | 132 | 84.1 | 0.62 | |

| Interested in PrEP | 355 | 44.6 | 250 | 43.8 | 32 | 47.1 | 73 | 46.5 | ||

| Not interested in PrEP | 275 | 34.5 | 197 | 34.5 | 19 | 27.9 | 59 | 37.6 | ||

| Rejected answer | 22 | 2.8 | 16 | 2.8 | 3 | 4.4 | 3 | 1.9 | ||

Age of the participants ranged from 18 years to 60 years, with a mean of 28.2 years (s.d. = 7.43). No significant differences in age distribution were observed between groups (P = 0.467). Participants mostly identified as single or unmarried (n = 712, 89.4%) and as gay or homosexual (n = 612, 76.9%). The ‘chemsex’ group reported a higher frequency (2.9%) of heterosexual orientation compared to other groups (P = 0.010). Notably, 78% of participants voluntarily disclosed their sexual orientation (n = 623). Educational attainment was predominantly undergraduate and above (n = 587, 73.7%). The largest proportion of participants reported a monthly income ranging from RMB5001 to RMB8000 (n = 213, 26.8%).

SDU and HIV/STIs risk scores

A scatter boxplot of the HIV/STIs risk scores among the ‘SDU’ and ‘non-SDU’ groups shows that the median risk scores were similar among the three groups, with the quartiles of the risk score for SDU with chemsex drugs being higher (Fig. S1). Fewer individuals with high-risk scores were in the ‘SDU without chemsex’ group. We did not identify statistically significant differences among the three groups regarding their HIV/STIs risk scores (Kruskal–Wallis test, P = 0.308).

SDU and number of sexual partners

Fig. S2 shows the number of sexual partners in the past 6 months among participants, categorised by their drug use. The distribution of sexual partners across different groups did not follow a normal distribution, as indicated by the P-value from the normality test (P < 0.0001). Therefore, the Kruskal–Wallis test was conducted and showed the group differences (P = 0.004). MSM with SDU without chemsex had a statistically significant difference in the number of sexual partners compared to MSM with SDU with chemsex (P = 0.004). The number of sexual partners in the ‘chemsex’ group increased and was concentrated at a higher level. In contrast, the number of sexual partners in the ‘SDU without chemsex’ group was generally lower, and the extreme values of sexual partners were even rarer. The number of people in different groups with five or more sexual partners was compared in Table 2, and the χ2-test results indicate statistical differences among the groups (P = 0.039). The ‘chemsex’ group (n = 29, 42.7%) had the highest proportion of participants with five or more sexual partners.

| Overall (n = 796) | Neither group (non-SDU) (n = 571) | SDU with chemsex (n = 68) | SDU without chemsex (n = 157) | X2 | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sexual partners | |||||||

| Equal or above five | 265 (33.29%) | 195 (34.15%) | 29 (42.65%) | 41 (26.11%) | 6.511 | 0.039* | |

| Sexual acts | |||||||

| Self-masturbated | 183 (22.99%) | 130 (22.8%) | 26 (38.2%) | 27 (17.2%) | 11.918 | 0.003* | |

| Masturbated for a man | 287 (36.06%) | 220 (38.5%) | 26 (38.2%) | 41 (26.1%) | 8.385 | 0.015* | |

| Sexual act pairs | |||||||

| Self-masturbated ~ Receptive anal sex | 12 (1.51%) | 9 (1.58%) | 3 (4.41%) | 0 (0.0%) | 6.284 | 0.043* | |

| Masturbated by a man (receptive rimming) | 9 (1.13%) | 5 (0.88%) | 3 (4.41%) | 1 (0.64%) | 7.223 | 0.027* | |

| Receptive oral sex (self-masturbated) | 16 (2.01%) | 11 (1.93%) | 4 (5.88%) | 1 (0.64%) | 6.7 | 0.035* | |

| Receptive oral sex (receptive rimming) | 99 (12.44%) | 64 (11.21%) | 15 (22.06%) | 20 (12.74%) | 6.585 | 0.037* | |

| Receptive oral sex (insertive anal sex) | 121 (15.20%) | 80 (14.01%) | 5 (7.35%) | 36 (22.93%) | 11.153 | 0.004* | |

| Insertive oral sex (receptive oral sex) | 92 (11.56%) | 75 (13.13%) | 1 (1.47%) | 16 (10.19%) | 8.445 | 0.015* | |

| PrEP preference | |||||||

| Current using PrEP | 72 (9.05%) | 58 (10.16%) | 5 (7.35%) | 9 (5.73%) | 3.190 | 0.20 | |

| Stop using PrEP | 72 (9.05%) | 50 (8.76%) | 9 (13.24%) | 13 (8.28%) | 1.621 | 0.44 | |

| Interested in PrEP | 355 (44.60%) | 250 (43.78%) | 32 (47.06%) | 73 (46.50%) | 0.549 | 0.76 | |

| Not interested in PrEP | 275 (34.55%) | 197 (34.50%) | 19 (27.94%) | 59 (37.58%) | 1.951 | 0.38 | |

*P < 0.05.

SDU and sexual behaviour patterns

We conducted a multivariable logistic regression analysis that adjusted for potential confounders (age, level of education, monthly income, etc.) and compared it with univariable logistic regression models. None of the P-values across group comparisons reached statistical significance (P > 0.05) (Tables S2 and S3). This indicates that potential confounders did not have a significant effect on the comparisons of sexual acts between groups, validating the robustness of our univariable analysis results.

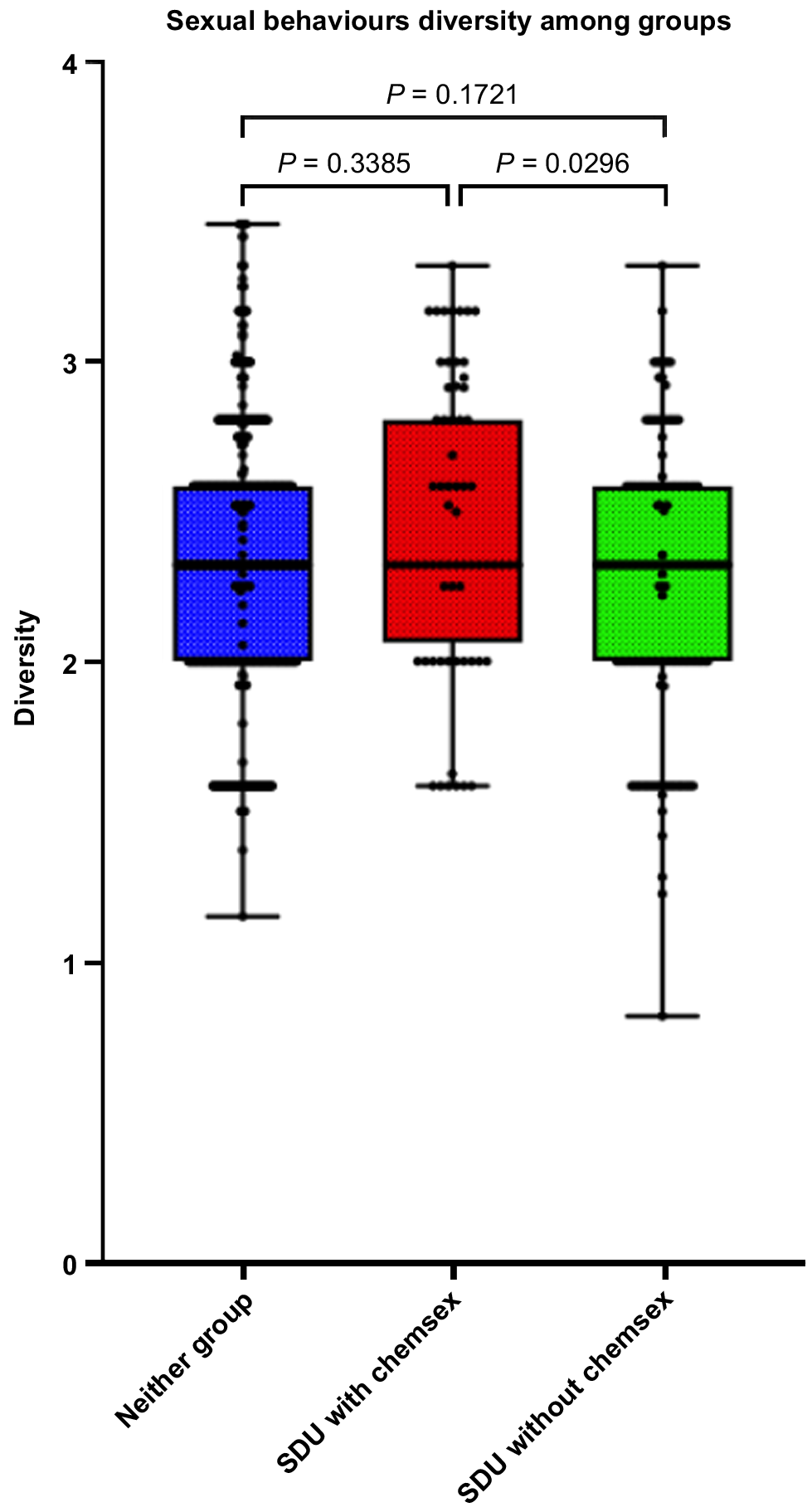

Table 2 shows that the difference in self-masturbation (P = 0.003) and being masturbated by a man (P = 0.015) among the three groups were statistically significantly different. The Shannon diversity index was used to calculate the richness of participants’ most recent sexual activity. The non-parametric statistical test results of the Shannon diversity index under different group conditions (Fig. 2). There was a statistically significant difference between the SDU with chemsex drugs and the ‘SDU without chemsex’ groups (P = 0.030). The one-way ANOVA test indicated a statistically significant difference between the diversity of sexual activity and SDU (P = 0.031).

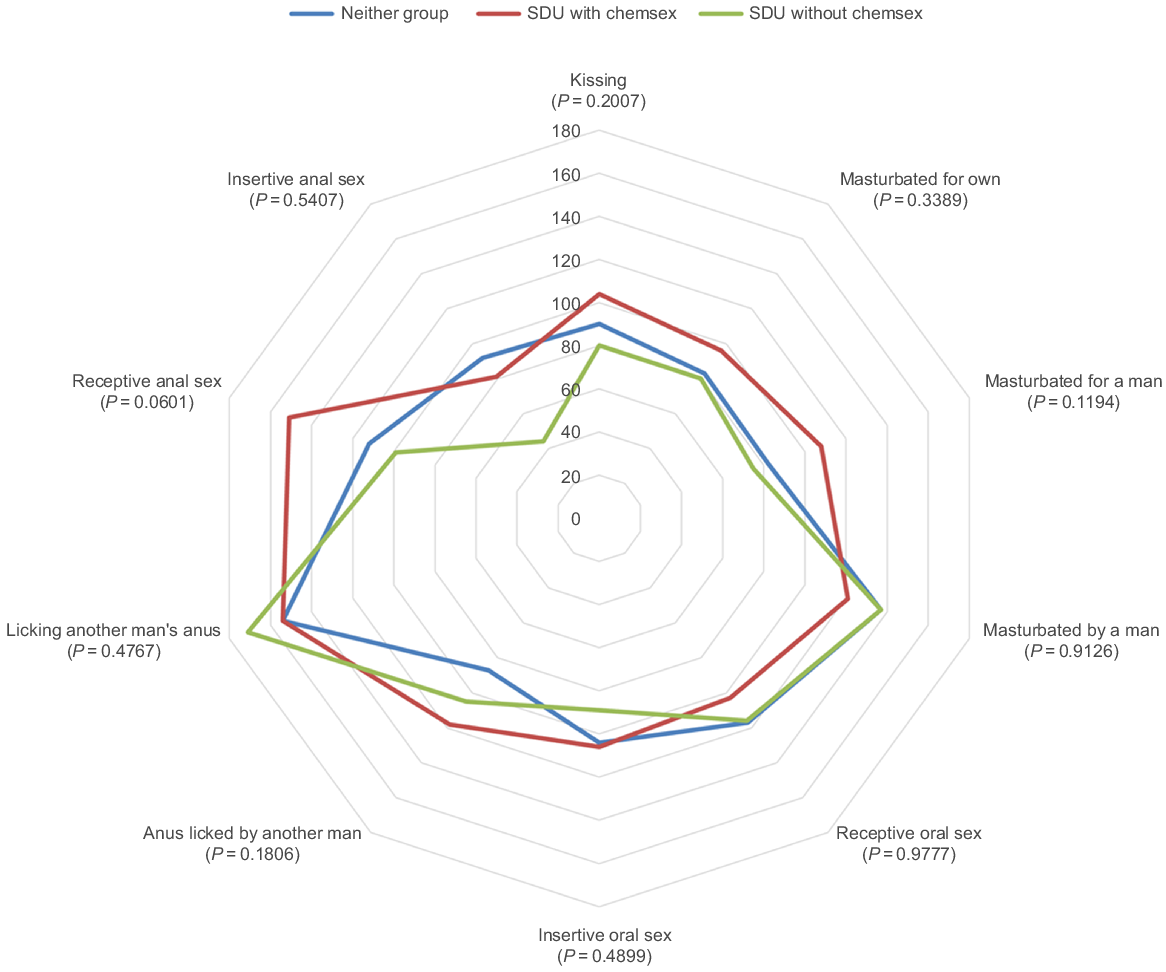

Fig. 3 is a radar plot that compared the number of sexual activities in the past 12 months among groups. Kruskal–Wallis test results showed that there were group differences in masturbating another man (P = 0.050). In general, the ‘SDU with chemsex’ group engaged in most types of sexual behaviours more frequently, followed by the ‘SDU without chemsex’ group. For the ‘non-SDU’ group, self-masturbation was most frequent, and they engaged in other sexual behaviours less frequently than the other two groups.

We further compared the differences in sexual behaviour pairs among different groups. The ‘chemsex’ group were more likely to be involved in sexual activity pairs with receptive or insertive anal sex. Individuals in the ‘chemsex’ group had a major proportion of those who engaged in being masturbated by a man first followed by receptive rimming compared to the other two groups (4.4%, P = 0.027) (Table 2). Participants in the ‘chemsex’ group had a lower proportion who engaged in insertive oral sex followed by receptive oral sex (1.5%, P = 0.050). Individuals in the ‘SDU without chemsex’ group had the highest proportion of insertive oral sex followed by receptive oral sex (10.2%, P = 0.015). After engaging in receptive oral sex, the ‘chemsex’ group was more likely to continue with self-masturbation (n = 4, 5.9%) or receptive rimming (n = 15, 22.1%) but showed a lower likelihood of engaging in insertive anal sex (n = 5, 7.4%). For statistical results for all sexual activities and sexual activity pairs, see Table S4.

We compared the correlation of SDU on different sexual behaviours and counted the number of occurrences of specific sexual behaviours separately according to whether they use other drugs for sexual purposes or not (Table S4). Kissing, as typical sexual behaviour, occurred more frequently in the ‘non-SDU’ group than in the other groups. Most (82.7%) of the ‘non-SDU’ group had kissed during their last sexual encounter. In addition to kissing, the three most common sexual behaviours in the ‘chemsex’ group were receptive oral sex (n = 51, 75.0%), insertive oral sex (n = 37, 54.4%), and receptive anal sex (n = 36, 52.9%).

SDU and PrEP use

To investigate the influence of SDU on PrEP use, the variations among groups were counted based on the distinct participant attitudes regarding PrEP across the four groups (Table 2). The data show that men who did not use drugs for sexual purposes had a higher percentage of PrEP use (n = 58, 10.2%), while men who used SDU without chemsex drugs were more likely to have no interest in PrEP (n = 59, 37.6%). More people in the ‘SDU with chemsex’ group chose either to stop using PrEP (n = 9, 13.2%) or expressed interest in PrEP (n = 32, 47.1%). However, the differences in participant numbers among these three groups did not reach statistical significance (P > 0.05).

Discussion

We found that MSM who engaged in chemsex reported a higher number of sexual partners and had more frequent engagement in masturbation and sequential sexual activities, particularly those involving masturbation and receptive oral sex. This contrast was evident when compared to MSM not involved in chemsex, highlighting a unique behavioural profile within this subgroup. Interestingly, the ‘SDU without chemsex’ group exhibited similar patterns of sexual acts and number of sexual partners as the ‘non-SDU’ group. This similarity suggests that the specific use of chemsex drugs, rather than SDU in general, is a key differentiator of sexual behaviour among MSM. This insight is valuable for healthcare providers working with the MSM community. It highlights the need for targeted harm reduction strategies and support for those engaged in chemsex. By understanding these distinct behavioural patterns, healthcare professionals can offer more effective interventions focused on promoting safer sexual practices.

Our study revealed associations between chemsex drug use and various sexual behaviours among MSM. Individuals in the ‘chemsex’ group reported a higher number of sexual partners (≥5), compared to other groups, suggesting a potential link between chemsex drug use and increased sexual activity. This may be attributed to the disinhibitory correlations of chemsex drugs on sexual decision making,31 leading to an increased likelihood of sexual encounters with multiple partners. Our study has identified a concerning trend in the sexual behaviours of the ‘chemsex’ group among the MSM community, notably a higher frequency of engagement in anal sex. This finding aligns with previous research,17,32 which can be attributed to the association between chemsex and impulsive behaviours,33 as well as its impact on individuals’ self-regulatory capacity.34 Anal sex is recognised for elevating the risk of transmitting HIV/STIs,35 particularly when condoms are not consistently used. Regarding sexual act pairs, our analysis revealed distinct patterns: participants in the ‘chemsex’ group were more likely to engage in receptive rimming (22.06%) following receptive oral sex, while the ‘SDU without chemsex’ group showed a higher proportion of insertive anal sex (22.93%). These differences reflect varying sexual behavioural preferences among different groups. Understanding these sexual act pairs, particularly those involving anal sex, is crucial for identifying high-risk patterns and implementing targeted risk reduction strategies. To our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to examine the impact of SDU on sexual act pairs. Moreover, the ‘chemsex’ group shows a concerning trend in PrEP usage, with 13.2% having ever used PrEP but not continuing, compared to 8.8% in the ‘non-SDU’ group and 8.3% in the ‘SDU without chemsex’ group. Although no statistically significant differences were observed among groups, the combination of increased high-risk sexual activity and higher rates of PrEP discontinuation highlights the pressing need for specifically designed public health interventions. These findings shows the diverse sexual behaviours and preferences within the MSM community. To develop effective public health strategies, further research is necessary to understand the underlying factors driving these behavioural differences and their implications for health and safety.

Our research reports that 8.5% of participants reported chemsex, among which 99% used poppers. The rare incidence of other chemsex drug use may be attributed to the strict legal environment of China,36 limiting access to drugs commonly associated with chemsex. It is worth noting that a substantial number of young individuals using erectile dysfunction medications, which suggests an alternative avenue for sexual enhancement. This trend could be influenced by factors such as social stigma surrounding chemsex or the difficulty in accessing specific illicit drugs. The implications of these drug use patterns underscore the importance of considering regional legal frameworks and societal attitudes in tailoring interventions aimed at harm reduction and education within the Chinese MSM community.

Another observation worth noting is that 60% of participants using erectile dysfunction medications (e.g. Viagra) were younger individuals aged 30 years or below who reported no lifetime use of chemsex drugs. This finding is particularly striking given that large-scale multinational studies estimate the prevalence of erectile dysfunction in young males to be around 30%.37 Some chemsex participants might be using erectile dysfunction medications to counteract the sexual dysfunction caused by chemsex drug use.38,39 In this context, the concealment of chemsex drug use by participants becomes a relevant factor to consider in our study. Therefore, the actual prevalence of chemsex practices might be higher than what is currently reported, suggesting potential underreporting among young MSM. These insights highlight the need for nuanced and comprehensive assessments in SDU research, especially among younger demographics.

Our study has several limitations. First, the assessment of HIV/STI risk may not be precise. We did not provide testing for HIV/STIs to participants, relying instead on the MySTIRisk for assessing their risk of HIV/STIs infection. However, it should be noted that the MySTIRisk is based on behavioural data from the Australian population, and there is currently no comparable tool for the Chinese population. Consequently, estimations of HIV/STIs risk may be subject to bias. We emphasise that MySTIRisk was the only tool that is tailored for our study. Further, this study employed a mobile platform for data collection, and compared to the general MSM population, application users may display greater enthusiasm towards online technologies, more active sexual lifestyles, and heightened health consciousness.40 Hence, individuals participating in this study are likely to have better socio-economic status compared to the general population of MSM. Further clarification is also needed concerning the criteria used for grouping. Currently, the distinction between SDU and chemsex remains somewhat vague, and there are variations in the regulation of drugs across different countries and regions. In our study, we followed established conventions for classification. Unless individuals were using chemsex drugs, those who consumed alcohol for sexual purposes were considered to be in the ‘SDU’ group.

While our findings suggest that MSM with a history of chemsex exhibit greater diversity in sexual practices, it is important to interpret these results with caution. The observed differences, particularly those related to the use of poppers, may reflect broader behavioural trends rather than direct health risks. Moreover, the potential gap between lifetime SDU and recent sexual behaviour introduces an element of uncertainty, necessitating a more nuanced and conservative interpretation of the data. Future research should aim to examine these behaviours within a more consistent timeframe to better understand their health implications.

In conclusion, the findings in our study provide valuable insights into the landscape of HIV/STI risks among MSM in China. Future research should address these limitations by employing more accurate risk assessment tools tailored to the Chinese population, ensuring diverse geographic representation, and adopting comprehensive criteria for classifying SDU and chemsex. This will facilitate a deeper understanding of the challenges faced by MSM communities and support the development of targeted interventions to mitigate HIV/STI transmission risks within this population.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Data availability

The data that support this study cannot be publicly shared due to ethical or privacy reasons and may be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author if appropriate.

Conflicts of interest

Jason Ong is the co-Editor-in-Chief of Sexual Health, and Weiming Tang and Lei Zhang are Associate Editors of Sexual Health. To mitigate this potential conflict of interest they had no editor-level access to this manuscript during peer review. The authors have no further conflicts of interest to declare.

Declaration of funding

JJS is supported by the Central Clinical School International Tuition Scholarship (APP 5228547). JJO is supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Emerging Leadership Fellowship (Grant number: 1193955). LZ is supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China (2022YFC2304900, 2022YFC2505100), the National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFC2505100, 2022YFC2505103); Outstanding Young Scholars Support Program (Grant number: 3111500001); Epidemiology modelling and risk assessment (Grant number: 20200344) and Xi’an Jiaotong University Young Scholar Support Grant (Grant number: YX6J004).

References

1 Íncera-Fernández D, Román FJ, Moreno-Guillén S, Gámez-Guadix M. Understanding sexualized drug use: substances, reasons, consequences, and self-perceptions among men who have sex with other men in Spain. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023; 20: 2751.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

3 Norman SB, Harrop E, Wilkins KC, Pedersen ER, Myers US, Chabot A, Rodgers C. Development of sexual relationships and substance use. The Oxford Handbook of Adolescent Substance Abuse, Oxford Library of Psychology (2019; online edn, Oxford Academic, 10 Dec. 2015). Available at https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199735662.013.020 [accessed 3 Dec 2024]

4 Weibell MA, Hegelstad WtV, Auestad B, Bramness J, Evensen J, Haahr U, Joa I, Johannessen JO, Larsen TK, Melle I, Opjordsmoen S, Rund BR, Simonsen E, Vaglum P, McGlashan T, McGorry P, Friis S. The effect of substance use on 10-year outcome in first-episode psychosis. Schizophr Bull 2017; 43: 843-851.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

6 Hegazi A, Lee MJ, Whittaker W, Green S, Simms R, Cutts R, Nagington M, Nathan B, Pakianathan MR. Chemsex and the city: sexualised substance use in gay bisexual and other men who have sex with men attending sexual health clinics. Int J STD AIDS 2017; 28: 362-366.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

7 Edmundson C, Heinsbroek E, Glass R, Hope V, Mohammed H, White M, Desai M. Sexualised drug use in the United Kingdom (UK): a review of the literature. Int J Drug Policy 2018; 55: 131-148.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

8 European Chemsex Forum report Paris. Chemsex Forum Organisation Committee. 2019. Available at https://idpc.net/publications/2020/04/european-chemsex-forum-report

9 Irfan SD, Sarwar G, Emran J, Khan SI. An uncharted territory of sexualized drug use: exploring the dynamics of chemsex among young and adolescent MSM including self-identified gay men in urban Dhaka, Bangladesh. Front Psychol 2023; 14: 1124971.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

10 Maxwell S, Shahmanesh M, Gafos M. Chemsex behaviours among men who have sex with men: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Drug Policy 2019; 63: 74-89.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

11 Wang H, Jonas KJ, Guadamuz TE. Chemsex and chemsex associated substance use among men who have sex with men in Asia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend 2023; 243: 109741.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

12 Berg RC, Amundsen E, Haugstvedt A. Links between chemsex and reduced mental health among Norwegian MSM and other men: results from a cross-sectional clinic survey. BMC Public Health 2020; 20: 1785.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

13 Wang Z, Mo PKH, Ip M, Fang Y, Lau JTF. Uptake and willingness to use PrEP among Chinese gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men with experience of sexualized drug use in the past year. BMC Infect Dis 2020; 20: 299.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

14 Tam G, Lee SS. Acceptance of opt-out HIV testing in out-patient clinics in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J 2022; 28: 86-87.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

15 del Pozo-Herce P, Baca-García E, Martínez-Sabater A, Chover-Sierra E, Gea-Caballero V, Curto-Ramos J, Czapla M, Karniej P, Martínez-Tofe J, Sánchez-Barba M, et al. Descriptive study on substance uses and risk of sexually transmitted infections in the practice of Chemsex in Spain. Front Public Health 2024; 12: 1391390.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

16 Olete RA, Strong C, Leyritana K, Bourne A, Ko N-YM. ChemsexPH: the association between chemsex, HIV status and adherence to antiretroviral therapy among men who have sex with men in the Philippines. J Int AIDS Soc 2024; 27: e26323.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

17 Glynn RW, Byrne N, O’Dea S, Shanley A, Codd M, Keenan E, Ward M, Igoe D, Clarke S. Chemsex, risk behaviours and sexually transmitted infections among men who have sex with men in Dublin, Ireland. Int J Drug Policy 2018; 52: 9-15.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

18 Tomkins A, George R, Kliner M. Sexualised drug taking among men who have sex with men: a systematic review. Perspect Public Health 2019; 139: 23-33.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

19 Malandain L, Thibaut F. Chemsex: review of the current literature and treatment guidelines. Curr Addict Rep 2023; 10: 563-571.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

20 Yu VG, Lasco G. Neither legal nor illegal: poppers as ‘acceptable’ chemsex drugs among men who have sex with men in the Philippines. Int J Drug Policy 2023; 104004.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

21 Coronado-Muñoz M, García-Cabrera E, Quintero-Flórez A, Román E, Vilches-Arenas Á. Sexualized drug use and chemsex among men who have sex with men in Europe: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Med 2024; 13: 1812.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

22 Ma R, Perera S. Safer ‘chemsex’: GPs’ role in harm reduction for emerging forms of recreational drug use. Br J Gen Pract 2016; 66: 4-5.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

23 Calsyn DA, Cousins SJ, Hatch-Maillette MA, Forcehimes A, Mandler R, Doyle SR, Woody G. Sex under the influence of drugs or alcohol: common for men in substance abuse treatment and associated with high-risk sexual behavior. Am J Addict 2010; 19: 119-127.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

25 Xu X, Ge Z, Chow EPF, Yu Z, Lee D, Wu J, Ong JJ, Fairley CK, Zhang L. A machine-learning-based risk-prediction tool for HIV and sexually transmitted infections acquisition over the next 12 months. J Clin Med 2022; 11: 1818.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

26 Konopiński MK. Shannon diversity index: a call to replace the original Shannon’s formula with unbiased estimator in the population genetics studies. PeerJ 2020; 8: e9391.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

27 Ma ZS. Measuring microbiome diversity and similarity with hill numbers. In: Nagarajan M, editor. Metagenomics. Academic Press; 2018. pp. 157–178. 10.1016/B978-0-08-102268-9.00008-2

29 Neath AA, Cavanaugh JE. The Bayesian information criterion: background, derivation, and applications. WIREs Comp Stat 2012; 4: 199-203.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

30 Lee S, Lee DK. What is the proper way to apply the multiple comparison test? Korean J Anesthesiol 2018; 71: 353-360.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

31 Ivey K, Bernstein KT, Kirkcaldy RD, Kissinger P, Edwards OW, Sanchez T, Abara WE. Chemsex drug use among a national sample of sexually active men who have sex with men – American Men’s Internet Survey, 2017–2020. Subst Use Misuse 2023; 58: 728-734.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

32 Song D, Zhang H, Wang J, Han D, Dai L, Liu Q, Yu F, Operario D, She M, Zaller N. Sexual risk behaviours and their correlates among gay and non-gay identified men who have sex with men and women in Chengdu and Guangzhou, China. Int J STD AIDS 2013; 24: 780-790.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

33 Esteban L, Bellido I, Arcos-Romero AI. The “Chemsex” phenomenon and its relationship with psychological variables in men who have sex with men. Arch Sex Behav 2024; 53: 3515-3525.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

34 Perry JL, Carroll ME. The role of impulsive behavior in drug abuse. Psychopharmacology 2008; 200: 1-26.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

35 Lyons A, Pitts M, Grierson J, Smith A, McNally S, Couch M. Age at first anal sex and HIV/STI vulnerability among gay men in Australia. Sex Transm Infect 2012; 88: 252-257.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

36 Florêncio J. Chemsex cultures: subcultural reproduction and queer survival. Sexualities 2023; 26: 556-573.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

37 Nguyen HMT, Gabrielson AT, Hellstrom WJG. Erectile dysfunction in young men – a review of the prevalence and risk factors. Sex Med Rev 2017; 5: 508-520.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

38 Deimel D, Stöver H, Hößelbarth S, Dichtl A, Graf N, Gebhardt V. Drug use and health behaviour among German men who have sex with men: results of a qualitative, multi-centre study. Harm Reduct J 2016; 13: 36.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

39 Íncera-Fernández D, Gámez-Guadix M, Moreno-Guillén S. mental health symptoms associated with sexualized drug use (Chemsex) among Men who have sex with men: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18: 13299.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

40 Kwan TH, Lee SS. Bridging awareness and acceptance of pre-exposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men and the need for targeting chemsex and HIV testing: cross-sectional survey. JMIR Public Health Surveill 2019; 5: e13083.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |