Prescribing pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention: a cross-sectional survey of general practitioners in Australia

Jason Wu A B * , Christopher K. Fairley

A B * , Christopher K. Fairley  B C , Daniel Grace

B C , Daniel Grace  D , Benjamin R. Bavinton

D , Benjamin R. Bavinton  E , Doug Fraser E , Curtis Chan

E , Doug Fraser E , Curtis Chan  E , Eric P. F. Chow

E , Eric P. F. Chow  B C F § and Jason J. Ong

B C F § and Jason J. Ong  B C F G §

B C F G §

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

Abstract

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is a safe and effective medication for preventing HIV acquisition. We examined Australian general practitioners’ (GP) knowledge of PrEP efficacy, characteristics associated with ever prescribing PrEP and barriers to prescribing.

We conducted an online cross-sectional survey of GPs working in Australia between April and October 2022. We performed univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses to identify factors associated with: (1) the belief that PrEP was at least 80% efficacious; and (2) ever prescribed PrEP. We asked participants to rate the extent to which barriers affected their prescribing of PrEP.

A total of 407 participants with a median age of 38 years (interquartile range 33–44) were included in the study. Half of the participants (50%, 205/407) identified how to correctly take PrEP, 63% (258/407) had ever prescribed PrEP and 45% (184/407) felt confident with prescribing PrEP. Ever prescribing PrEP was associated with younger age (AOR 0.97, 95% CI: 0.94–0.99), extra training in sexual health (AOR 2.57, 95% CI: 1.54–4.29) and being a S100 Prescriber (OR 2.95, 95% CI: 1.47–5.90). The main barriers to prescribing PrEP included: ‘Difficulty identifying clients who require PrEP/relying on clients to ask for PrEP’ (76%, 310/407), ‘Lack of knowledge about PrEP’ (70%, 286/407) and ‘Lack of time’ (69%, 281/407).

Less than half of our GP respondents were confident in prescribing PrEP, and most had difficulty identifying who would require PrEP. Specific training on PrEP, which focuses on PrEP knowledge, identifying suitable clients and making it time efficient, is recommended, with GPs being remunerated for their time.

Keywords: Australasia, barriers, general practice, health promotion, HIV/AIDS, PrEP, prevention, primary care.

Introduction

Studies have shown that pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is up to 99% effective at reducing HIV infection by sexual transmission and is safe.1,2 The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS has set a declaration to end the AIDS epidemic by 2030, and one of the targets to accomplish this goal is to ensure the availability of PrEP for 10 million people at substantial risk of HIV by 2025.3

Most GPs in Australia have no or limited experience in HIV treatment and prevention. There were 39,736 GPs working in Australia in 2022/2023,4 and as of January 2024, there were only 265 HIV S100 prescribers (able to prescribe HIV treatment), with only a proportion of these being GPs.5 There are only 114 sexual health physicians working in Australia, with the majority working in major cities.6 Any doctor or nurse practitioner in Australia can prescribe PrEP, which has been on the Australian government’s Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) since April 2018. The PBS subsidises the cost of certain medications, so that PrEP costs A$30 for 30 pills or A$7.30 for people with a concession card. There have been 18,217 individual prescribers who have prescribed PrEP in Australia.7

Past studies have identified several barriers to PrEP prescribing among GPs. Barriers include lack of knowledge regarding PrEP, inability to identify clients at risk of HIV and concern that PrEP use may increase the incidence of other STIs.8–12 An Australian GP questionnaire found the main barriers to PrEP prescribing were lack of experience with antiretrovirals and lack of guidelines for prescription.13 Another Australian study involving interviews with 51 healthcare professionals identified barriers, such as attributing PrEP to ‘promiscuity’ and a belief that condom use was satisfactory HIV prevention.14

These studies on PrEP perspectives among health professionals were either qualitative or were conducted before PrEP was available on the PBS for GPs to prescribe. We sought to conduct a quantitative study examining GP knowledge of PrEP, confidence with prescribing and the barriers to prescribing.

Methods

Study population and recruitment

We distributed this anonymous online survey to GPs, GP registrars and trainees in Australia between 14 April and 13 October 2022. Participants were eligible if they lived in Australia. Other exclusion criteria included having answers that were unusual for the question, and if <90% of the questions were answered. The survey link was disseminated via a Facebook group for Australian GPs, the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners, Melbourne Sexual Health Centre and Public Health Networks. This was a voluntary survey, and completion of the survey implied consent. Participants could opt-in to win one of five A$300 vouchers.

Survey instrument

Respondents accessed the survey through an online link (hosted by Qualtrics). We utilised a knowledge, attitudes and practices survey model to structure our questions.15 The survey collected data on sociodemographic characteristics and assessed their knowledge of PrEP. Respondents were given five options for each question, with the complete questions and options listed in Supplementary material file S1.

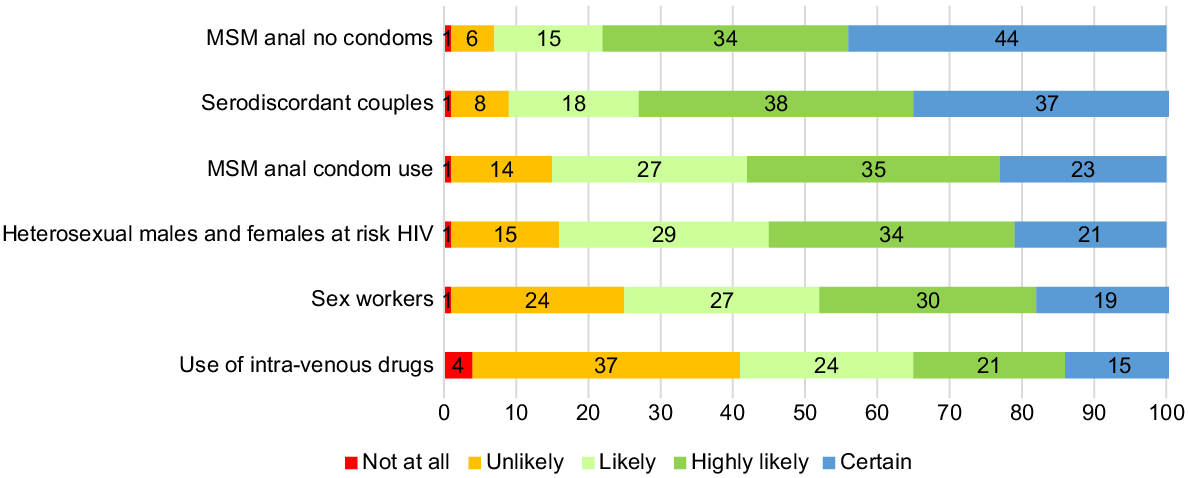

Respondents were asked how likely they were to prescribe PrEP to hypothetical clients from certain groups, with responses as a Likert scale (not at all, unlikely, likely, highly likely, certain). The groups included: ‘Sexually active males who have anal sex with males without condoms’, ‘Sexually active males who have anal sex with males and report condom use’, ‘Sexually active heterosexual males and females at increased risk of HIV transmission’, ‘People who inject drugs’, ‘Serodiscordant couples (i.e. one partner HIV-positive and the other HIV-negative)’ and ‘Sex workers’. These questions were adapted from an Australian study.13

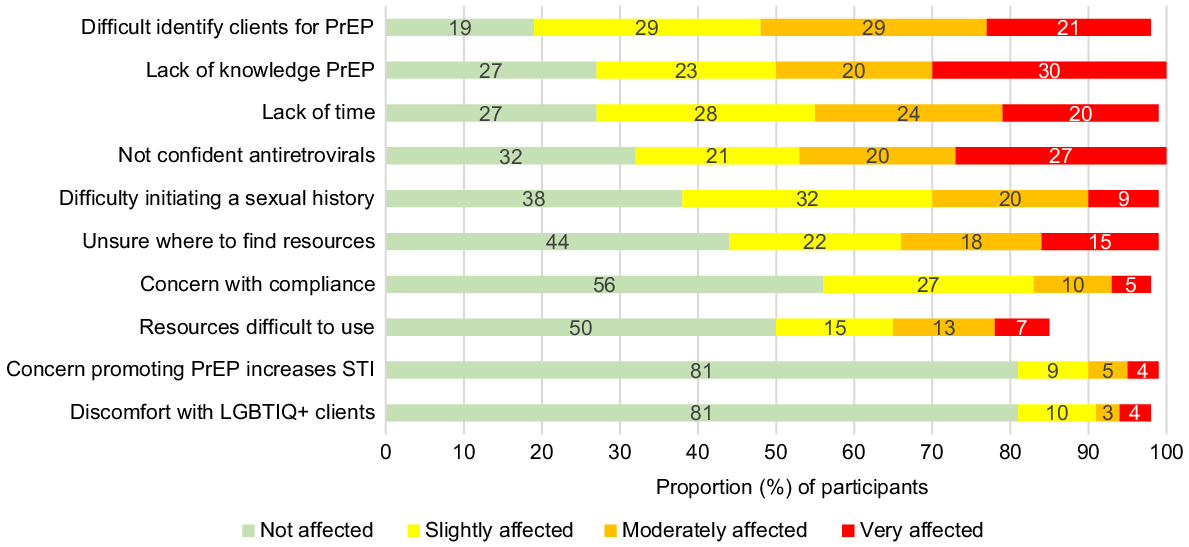

They were also asked how much certain barriers affect their ability to prescribe PrEP, with responses as a Likert scale (not affected, slightly affected, moderately affected, very affected, unsure). The barriers included ‘Lack of knowledge about PrEP’, ‘Lack of time to adequately counsel about PrEP’, ‘Unsure where to look for resources on PrEP’, ‘Resources on PrEP difficult to use/interpret’, ‘Difficulty identifying which clients would require PrEP/relying on clients to ask for PrEP’, ‘Lack of experience or hesitation in prescribing antivirals’, ‘Difficulty in finding an entry point to asking clients about their risk of HIV/sexual history’, ‘Concern that promoting PrEP may increase risk of other STIs’, ‘Concern that the client may not take PrEP properly/be non-compliant’ and ‘Discomfort with managing people who identify as LGBTIQ’. Respondents were also allowed to list other barriers via free text entry.

There were additional questions about how often GPs prescribed PrEP, how confident they felt when prescribing and how often they took clients’ sexual history, with full details in Supplementary material file S1.

Statistical analysis

We used descriptive statistics to summarise the characteristics of the study participants. Logistic regression analyses were used to identify factors associated with two outcomes: (1) belief that PrEP was at least 80% efficacious; and (2) ever prescribed PrEP. Variables were initially included in the multivariable model if the P-value was <0.20 in the univariable analysis. Using complete case analysis, we used a backward elimination approach to derive the final multivariable model. We reported both the crude and adjusted odds ratio, and the 95% confidence interval. Statistical significance was defined as having a P-value of <0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata (version 17, StataCorp).

Results

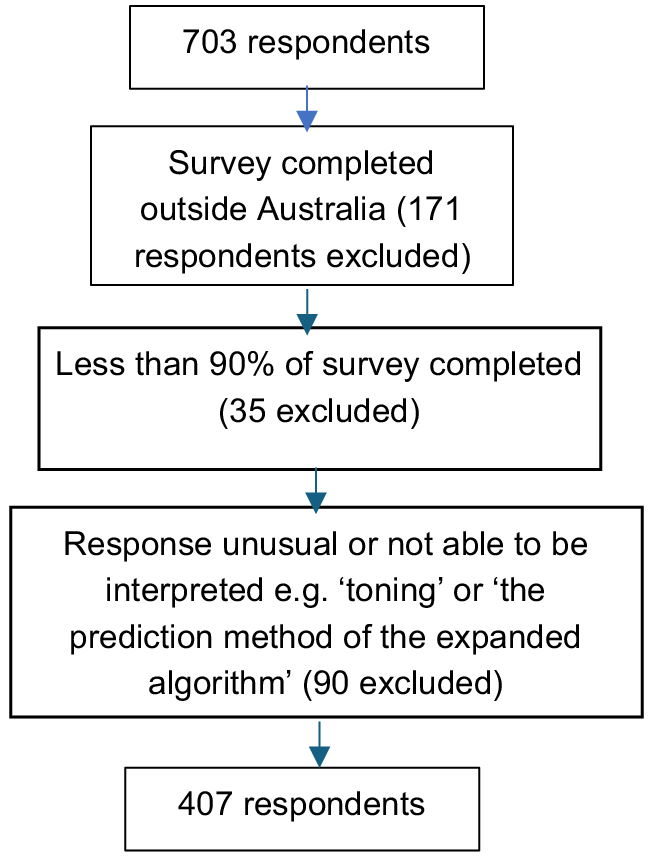

We received 703 survey respondents, but 90 were excluded, as they had answers that were unusual; for example, a question asking about barriers to PrEP prescribing yielded an answer of ‘The prediction method of the expanded algorithm’ (Fig. 1). A further 171 were excluded, as they were completed in countries outside Australia, and 35 were excluded, because the number of questions answered was <90%. The sociodemographic characteristics of the 407 participants are detailed in our other study.16 Briefly, the median age of the participants was 38 years, with an interquartile range of 33–44 years. The median duration of practising as a GP was 6 years, with an interquartile range of 4–12 years.

Test of knowledge

Only 50.4% (205/407) of participants could identify how to correctly take PrEP, which was selecting the response: ‘taking a pill daily for 7 days before an HIV exposure and then ongoing for at least 28 days’. A total of 24.8% (101/407) of respondents were unsure of how effective PrEP was at preventing HIV, whereas 68.8% (280/407) correctly identified that PrEP is >80% effective at preventing HIV.

Prescribing practices

Approximately two-thirds (63.4%, 258/407) of GPs had ever prescribed PrEP. Only 45.2% (184/407) felt confident with prescribing PrEP. When asked how often they prescribed PrEP, 44.7% (182/407) selected ‘less than once a year’, 13% (53/407) selected ‘at least once a year’, 18.2% (74/407) selected ‘at least once every three months’, 8.8% (36/407) selected ‘at least once a month’ and 9.2% (37/407) selected ‘at least once a week’. A total of 67% (273/407) of participants have had a client ask them for PrEP before. Table 1 outlines when participants last took a sexual history.

| Factors | n/N (%) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P-value | AOR (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.97 (0.95–1.00) | 0.02 | 0.97 (0.94–0.99) | 0.009 | ||

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 183/272 (67) | 1 | ||||

| Male | 75/99 (76) | 1.52 (0.90–2.57) | 0.11 | |||

| Location | ||||||

| Metropolitan or suburban | 112/174 (64) | 1 | ||||

| Inner city | 59/74 (80) | 2.18 (1.14–4.15) | 0.02 | |||

| Regional | 55/77 (71) | 1.38 (0.77–2.48) | 0.28 | |||

| Rural | 32/46 (70) | 1.27 (0.63–2.55) | 0.51 | |||

| State/territory of practice | ||||||

| Victoria | 105/146 (72) | 1 | ||||

| New South Wales | 56/78 (72) | 0.99 (0.54–1.83) | 0.98 | |||

| Queensland | 37/59 (63) | 0.66 (0.35–1.24) | 0.19 | |||

| Western Australia | 22/34 (65) | 0.72 (0.32–1.58) | 0.40 | |||

| South Australia | 25/36 (69) | 0.89 (0.40–1.97) | 0.76 | |||

| Northern Territory | 4/5 (80) | 1.56 (0.17–14.39) | 0.69 | |||

| Tasmania | 9/13 (69) | 0.88 (0.26–3.01) | 0.83 | |||

| Duration of practice (years) | 0.97 (0.95–1.00) | 0.05 | ||||

| Extra training in sexual health | ||||||

| No | 145/229 (63) | 1 | 1 | |||

| Yes | 113/142 (80) | 2.26 (1.38–3.68) | <0.01 | 1.83 (1.09–3.06) | 0.02 | |

| S100 prescriber A | ||||||

| No | 205/311 (66) | 1 | 1 | |||

| Yes | 53/60 (88) | 3.91 (1.72–8.91) | <0.01 | 3.38 (1.44–8.00) | 0.01 | |

| Last sexual history taken from a client: | ||||||

| Less than a week ago | 192/258 (74) | 1 | 1 | |||

| Less than a month ago | 46/73 (63) | 0.59 (0.34–1.02) | 0.05 | 0.66 (0.37–1.17) | 0.15 | |

| More than a month ago | 20/40 (50) | 0.34 (0.17–0.68) | <0.01 | 0.35 (0.17–0.71) | <0.01 |

Variables with P-value <0.05 are in bold. N = 371, because the multivariable regression analysis was a complete case analysis (i.e. only included respondents who answered all questions). AOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval. Utilised backward elimination approach to derive the final multivariable model.

Prescribing to certain groups

Fig. 2 details the proportion of respondents who stated they would be likely, highly likely or certain to prescribe to certain groups. Some notable results include sexually active men who have anal sex with men without condoms (92.6%, 377/407) and sex workers in Australia (74.9%, 305/407).

Factors associated with stated efficacy of PrEP >80% and ever prescribing PrEP

Table 1 demonstrates that the efficacy of PrEP >80% was associated with younger age (adjusted odds ratio (AOR) 0.97 per additional year of age, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.94–0.99), and negatively associated with taking last sexual history ‘more than a month ago’ (AOR 0.35, 95% CI: 0.17–0.71) compared with ‘less than a week ago’, and positively associated with extra training in sexual health (AOR 1.83, 95% CI: 1.09–3.06) and S100 prescriber status (AOR 3.38, 95% CI: 1.44–8.00).

Table 2 demonstrates that ever prescribing PrEP was negatively associated with increasing age (AOR 0.96, 95% CI: 0.93–0.98), and positively associated with working in the inner city compared with metropolitan or suburban area (AOR 3.40, 95% CI: 1.65–7.03) and extra training in sexual health (AOR 2.57, 95% CI: 1.54–4.29), and negatively associated with being a GP in Western Australia (AOR 0.22, 95% CI: 0.09–0.52) compared with Victoria. Most (77.6%, 316/407) participants reported PrEP education should be an essential part of HIV education at GP visits.

| Factors | n/N | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P-value | AOR (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.97 (0.94–0.99) | 0.01 | 0.96 (0.93–0.98) | <0.01 | ||

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 159/272 (58) | 1 | 1 | |||

| Male | 77/99 (78) | 2.49 (1.46–4.23) | <0.01 | 2.67 (1.49–4.80) | <0.01 | |

| Location | ||||||

| Metropolitan or suburban | 101/174 (58) | 1 | 1 | |||

| Inner city | 62/74 (84) | 3.73 (1.88–7.43) | <0.01 | 3.40 (1.65–7.03) | <0.01 | |

| Regional | 48/77 (62) | 1.20 (0.69– 2.07) | 0.52 | 1.14 (0.62–2.09) | 0.68 | |

| Rural | 25/46 (54) | 0.86 (0.45–1.65) | 0.66 | 0.79 (0.38–1.65) | 0.54 | |

| State | ||||||

| Victoria | 106/146 (73) | 1 | 1 | |||

| New South Wales | 51/78 (65) | 0.71 (0.39–1.29) | 0.26 | 0.74 (0.38–1.41) | 0.35 | |

| Queensland | 34/59 (58) | 0.51 (0.27–0.97) | 0.03 | 0.80 (0.40–1.60) | 0.52 | |

| Western Australia | 14/34 (41) | 0.26 (0.12–0.57) | <0.01 | 0.22 (0.09–0.52) | <0.01 | |

| South Australia | 20/36 (56) | 0.47 (0.22–1.00) | 0.05 | 0.47 (0.21–1.08) | 0.07 | |

| Northern Territory | 3/5 (60) | 0.57 (0.09–3.51) | 0.54 | 0.71 (0.10–4.93) | 0.72 | |

| Tasmania | 8/13 (62) | 0.60 (0.19–1.96) | 0.40 | 0.54 (0.15–1.92) | 0.34 | |

| Duration of practice (years) | 0.98 (0.96–1.01) | 0.19 | ||||

| Extra training in sexual health | ||||||

| No | 131/229 (57) | 1 | 1 | |||

| Yes | 105/142 (74) | 2.12 (1.34–3.35) | <0.01 | 2.57 (1.54–4.29) | <0.01 | |

| S100 prescriber A | ||||||

| No | 187/311 (60) | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 49/60 (82) | 2.95 (1.47–5.90) | <0.01 | |||

| Last sexual history taken from a client: | ||||||

| Less than a week ago | 172/258 (67) | 1 | ||||

| Less than a month ago | 43/73 (59) | 0.72 (0.42–1.22) | 0.22 | |||

| More than a month ago | 21/40 (53) | 0.55 (0.28–1.08) | 0.08 |

Variables with P-value <0.05 are in bold. N = 371, because the multivariable regression analysis was a complete case analysis (i.e. only included respondents who answered all questions). AOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval. Utilised backward elimination approach to derive the final multivariable model.

Barriers

Fig. 3 details the level of impact of barriers to prescribing PrEP, with the top three barriers being: difficulty identifying clients who require PrEP/relying on clients to ask for PrEP (76.2%, 310/407), lack of knowledge about PrEP (70.3%, 286/407) and lack of time to adequately counsel regarding PrEP (69%, 281/407).

Level of impact of barriers on GPs and their PrEP prescribing (%). Note that lines do not total to 100%, because there was a fifth option for participants: ‘Unsure’. PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

Participants were allowed to write down other barriers that affected their prescribing of PrEP or that they could see affecting the prescribing of other doctors. The most common written response was problems with knowledge (30.7%, 51/166), followed by lack of clients (21.1%, 35/166) and lack of experience (15.1%, 25/166). For details on the other responses, refer to Supplementary material Fig. S1.

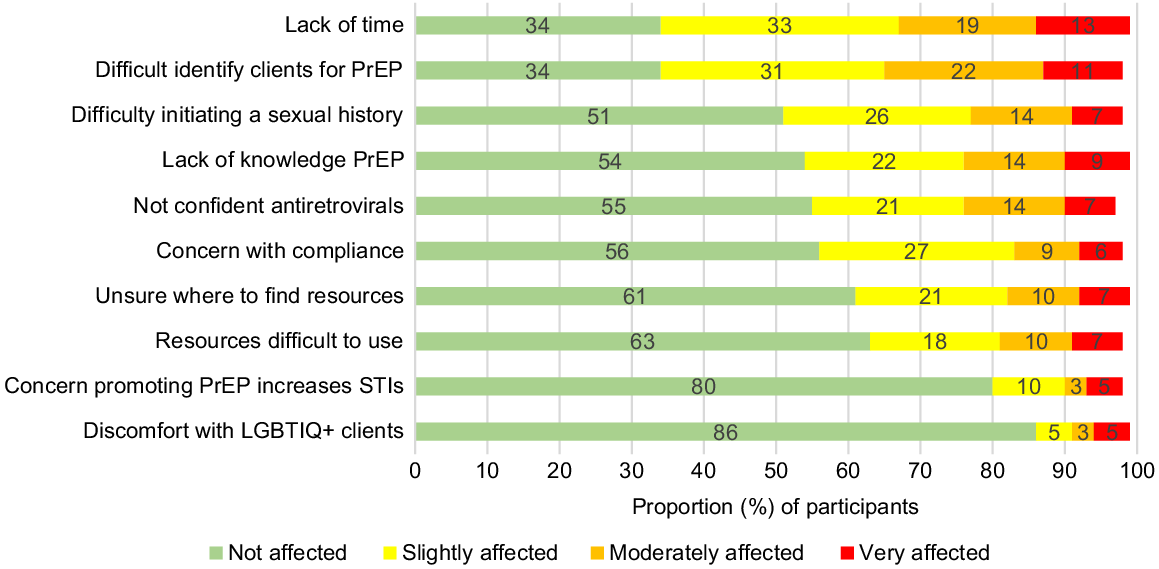

Barriers by the frequency of prescribing

Fig. 4 details the impact of barriers specifically on respondents who prescribed PrEP ‘more often’ (more frequent than every 3 months, including 3 months).

Level of impact of barriers on GPs who prescribe PrEP more often (more frequent than every 3 months, including 3 months; %). Note that lines do not total to 100%, because there was a fifth option for participants: ‘Unsure’. PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

Those who prescribed PrEP ‘more often’ are less likely to be affected by barriers than those who prescribe ‘not often’ (less frequent than every 3 months). Those who prescribed ‘more often’ were most affected by the barriers of lack of time to adequately counsel about PrEP (64.6%, 95/147), difficulty identifying which patients would require PrEP/relying on the patient to ask for PrEP (64.6%, 95/147) and difficulty in finding an entry point to asking patients about their risk of HIV/sexual history’ (47.6%, 70/147). Those who prescribe ‘not often’ were most affected by the following barriers: lack of knowledge about PrEP (86.8%, 204/235), difficulty identifying which patients would require PrEP/relying on patients to ask for PrEP (84.7%, 199/235) and lack of experience or hesitation in prescribing antiretrovirals (80.4%, 189/235). Further detailed analysis is supplied in Supplementary material Table S1.

Discussion

Our survey of Australian GPs contributes to the literature by demonstrating a significant knowledge gap about PrEP, with only half correctly identifying how to take PrEP. One-quarter of participants were unsure of how effective PrEP was at preventing HIV. In another Australian study from 2017, only 24% of respondents were able to identify how to take PrEP correctly, and 62% were unsure of how effective PrEP was at preventing HIV.13 Our study highlights other areas where GP knowledge of PrEP may be lacking. Three-quarters of participants would likely prescribe PrEP to sex workers; however, Australian PrEP guidelines do not identify sex workers as indicated for PrEP.17 Female sex workers have some of the lowest HIV rates of any population in Australia, with an incidence rate of <0.1 per 100 person-years.18

Our study found only 45% of participants felt confident about prescribing PrEP, with 35% stating they had never prescribed PrEP before. In contrast, a study of 45 GPs in Australia found that 71% of participants did not feel confident prescribing PrEP, and 93% had never consulted a client about PrEP before.13 However, this study was conducted in 2017, before PrEP was on the PBS.

The top three barriers that impacted our Australian GP participants’ prescribing of PrEP were difficulty identifying clients who would benefit from PrEP, lack of knowledge regarding PrEP and lack of time to adequately counsel regarding PrEP. These results are comparable with the literature, with the main barriers identified in studies as lack of knowledge regarding PrEP and difficulty identifying clients at risk of HIV.8–12 Difficulty identifying clients who would benefit from PrEP could be addressed by having GP clinics collect certain demographics as part of client registration. Many GP clinics do not have the sexuality of their clients recorded.19 We recommend GP clinics should have questions about clients’ sexual identity and the genders of sexual partners in client registration forms. Some potential negative consequences include clients being uncomfortable having this information on their medical file, reception staff being aware or if partners found out. It is important that the forms have the option of ‘choose not to disclose’. There is a PrEP website, pan.org.au, where GPs could have their clinics listed to show potential clients they are comfortable with prescribing PrEP.

Even those who prescribed ‘more often’ were still affected by barriers to prescribing, with the top three barriers being ‘lack of time’, ‘difficulty identifying patients who would benefit from PrEP’ and ‘difficulty finding an entry point to ask about HIV/sexual health’. The ‘lack of time’ as a barrier affects all GPs regardless of their knowledge level. It is difficult to identify clients who are men who have sex with men, as the LGBTQIA+ community still experience significant stigma from healthcare settings, and are less likely to visit GPs and be comfortable revealing their sexual orientation.20 Doctors often find it uncomfortable to take a sexual history, and it can be lacking even in specialties where sexual history taking should be routine; for example, a study found 37% of gynaecologists did not routinely assess clients’ sexual activities.21 Most of the other barriers are more knowledge-based, and those who prescribe more PrEP would be more likely to be knowledgeable and/or comfortable with sexual health. However, overall, they were affected significantly less by the barriers compared with those who prescribed less often.

The other major barrier is lack of time. Assessment and counselling for PrEP can quickly exceed the standard 10–15-min GP consult. An effective way of increasing the uptake of an intervention in GP practice could be creating a specific time-based Medicare item number,22 the main remuneration method for GPs in Australia, with this item being a higher remuneration rate compared with the current item for consults >20 min. However, creating a specific Medicare item can be difficult. A more acceptable solution could be short-term practice incentive payments; for example, an additional A$10 for every prescription of PrEP, running for 12 months. This can encourage GPs to invest time into learning about PrEP. A UK systematic literature review of 35 articles found payment for performance schemes increased services available and effectively motivated GPs.23 There is a limitation of whether Medicare can identify private scripts of PrEP to award a practice incentive payment, as overseas born men who have sex with men are the highest-risk group for HIV.18 Most medical software can generate data on scripts, so this could be a way to capture the private PrEP scripts, with the data being sent to Medicare.

Factors associated with prescribing PrEP were extra training in sexual health or being an S100 prescriber, working in an inner city setting and younger age. The reason why there is more prescribing in inner-city settings could be due to more sexual health clinics and high-caseload GPs being located in these settings. The association with younger age is likely due to going through GP training more recently and being more likely to accept more progressive ideas. There is a great need for more comprehensive training for GPs regarding PrEP, assuming no prior knowledge and, in particular, looking at better ways of identifying clients who would benefit from PrEP. This training should be constructed specifically for the GP context, taking into account the standard GP consultation time of 10–15 min, and GPs should be remunerated for the training with a recommended rate of at least A$200 per hour of training.

PrEP uptake could be increased by having a higher remuneration rate for the existing telehealth blood-borne item number 92734/92737, to allow more Australians, including in regional and remote areas, to access PrEP from GPs more confident with PrEP prescribing, and to encourage more GPs to learn about PrEP. Currently, these item numbers are at the same remuneration rate as standard telehealth items for general health issues: A$41.40 for consultation over 6 min.

The strength of this study was that it included GPs working in a range of settings and locations within Australia. Our study should be read in light of some limitations. First, the sample may not represent all GPs in Australia, as it is prone to sampling bias and it is likely that participants who had some interest in sexual health were more likely to participate. For instance, when compared with the Australian GP population, we had a greater proportion of female GPs (70.5% vs 49%), a younger cohort (most being aged 0–39 years (57%) vs most being aged 40–54 years (37%)) and most in Victoria (39.3%) versus most in NSW (24%).4 Another limitation is our use of multiple choice questions, whereas qualitative responses may have provided a more accurate assessment. Our question asking for participants to identify how to take PrEP could have been worded more clearly, as the answer ‘taking a pill before and after an HIV exposure, but only around the time of the exposure’ could be interpreted as PrEP on demand; however, it is technically not correct, as it should specify taking two pills before an HIV exposure. We adapted our knowledge questions from an Australian study13 that utilises a TGA-approved definition for how to take PrEP, whereas PrEP on demand is a well accepted method of taking PrEP that is not TGA approved. We did not ask about PrEP on demand. This could have affected the accuracy of our assessment of GP knowledge.

Conclusion

Most of our GP participants were not confident in prescribing PrEP and had difficulty identifying who would require PrEP. More GP-specific training on PrEP is needed, focusing on PrEP knowledge, identifying suitable clients and making it time efficient. The GPs should be paid for the time to undertake this training. Further training is in itself insufficient, as the wider issues facing general practice need to be addressed, such as chronic underfunding and no remuneration for training. Having questions about sexuality and the genders of sexual partners collected in registration forms could help GPs identify people who would benefit from PrEP. GPs are well placed to dramatically increase the number and geographical coverage of PrEP prescribing, but they need further support.

Data availability

JO, EC and JW had full access to all of the data in the study. De-identified data is available on reasonable request to the corresponding author. A preprint version of this article is available at https://www.medrxiv.org/node/757037.full.

Conflicts of interest

BRB, JJO and EPFC are Associate Editors of Sexual Health. To mitigate this potential conflict of interest they had no editor-level access to this manuscript during peer review. The authors have no further conflicts of interest to declare.

Declaration of funding

DG is supported by a Canada Research Chair in Sexual and Gender Minority Health. EPFC and JJO are each supported by an NHMRC Emerging Leadership Investigator Grant (GNT1172873 and GNT1193955, respectively). CKF is supported by an Australian NHMRC Leadership Investigator Grant (GNT1172900).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the following organisations for help with distributing our survey: GPs Down Under (GPDU) Facebook Group, North Western Melbourne Primary Health Network, Brisbane North Primary Health Network, Victorian primary care practice-based Research and Education Network (VicREN), the University of Melbourne, Dr Richard Teague and Murray City Country Coast GP Training. We also thank the researchers, William Lane, Clare Heal and Jennifer Banks, for allowing us to utilise their questionnaire from their study.13

References

2 Anderson PL, Glidden DV, Liu A, Buchbinder S, Lama JR, Guanira JV, et al. Emtricitabine-tenofovir concentrations and pre-exposure prophylaxis efficacy in men who have sex with men. Sci Transl Med 2012; 4(151): 151ra25.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

3 UNAIDS. Ending inequalities and getting on track to end AIDS by 2030; 2021. Available at https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2021-political-declaration_summary-10-targets_en.pdf#:~:text=Ensure%20availability%20of%20PrEP%20for%20%2810%20million%29%20people,appropriate%2C%20prioritized%2C%20people-centred%20and%20effective%20combination%20prevention%20options

5 ASHM. ASHM Prescriber Map 2024. Available at https://www.ashm.org.au/prescriber-maps/

6 Department of Health, Australian Government. Sexual health Medicine - 2016 factsheet 2016. Available at https://hwd.health.gov.au/resources/publications/factsheet-mdcl-sexual-health-2016.pdf

8 Smith AKJ, Haire B, Newman CE, Holt M. Challenges of providing HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis across Australian clinics: qualitative insights of clinicians. Sex Health 2021; 18(2): 187-94.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

9 Vanhamel J, Reyniers T, Wouters E, van Olmen J, Vanbaelen T, Nöstlinger C, et al. How do family physicians perceive their role in providing pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention?–an online qualitative study in Flanders, Belgium. Front Med 2022; 9: 828695.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

10 Villeneuve F, Cabot JM, Eymard-Duvernay S, Visier L, Tribout V, Perollaz C, et al. Evaluating family physicians’ willingness to prescribe PrEP. Med Mal Infect 2020; 50(7): 606-10.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

12 Chiarabini T, Lacombe K, Valin N. HIV pre-exposure chemoprophylaxis “PrEP” in general practice: are there significant barriers? [Prophylaxie préexposition au VIH (PrEP) en médecine générale: existe-t-il des freins?]. Sante Publique 2021; 33(1): 101-112.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

13 Lane W, Heal C, Banks J. HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis: knowledge and attitudes among general practitioners. Aust J Gen Pract 2019; 48(10): 722-27.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

14 Lazarou M, Fitzgerald L, Warner M, Downing S, Williams OD, Gilks CF, et al. Australian interdisciplinary healthcare providers’ perspectives on the effects of broader pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) access on uptake and service delivery: a qualitative study. Sex Health 2020; 17(6): 485-92.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

15 Médicins du Monde. The KAP survey model (knowledge, attitudes, and practices); 2011. Available at https://www.spring-nutrition.org/publications/tool-summaries/kap-survey-model-knowledge-attitudes-and-practices

16 Wu J, Fairley CK, Grace D, Chow EPF, Ong JJ. Agreement of and discussion with clients about undetectable equals untransmissible among general practitioners in Australia: a cross-sectional survey. Sex Health 2023; 20(3):242–49. 10.1071/SH23051

17 ASHM. 2021 National PrEP guidelines; 2021. Available at https://prepguidelines.com.au

19 Payne H. The new RACGP gender and sex standards, explained. 2021. Available at https://www.medicalrepublic.com.au/the-new-racgp-gender-and-sex-standards-explained/57824

20 Saxby K, de New SC, Petrie D. Structural stigma and sexual orientation disparities in healthcare use: evidence from Australian Census-linked-administrative data. Soc Sci Med 2020; 255: 113027.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

21 Sobecki JN, Curlin FA, Rasinski KA, Lindau ST. What we don’t talk about when we don’t talk about sex: results of a national survey of U.S. obstetrician/gynecologists. J Sex Med 2012; 9(5): 1285-94.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

22 Holden L, Williams ID, Patterson E, Smith JW, Scuffham PA, Cheung L, et al. Uptake of Medicare chronic disease management incentives – a study into service providers’ perspectives. Aust Fam Physician 2012; 41(12): 973-7.

| Google Scholar | PubMed |

23 Ahmed K, Hashim S, Khankhara M, et al. What drives general practitioners in the UK to improve the quality of care? A systematic literature review. BMJ Open Qual 2021; 10(1): e001127.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |