Sexual dissatisfaction and its association with health status among older adults in China: a nationwide study

Yiwen Diao A , Yan Sun B , Joseph D. Tucker

A , Yan Sun B , Joseph D. Tucker  C and Fan Yang A *

C and Fan Yang A *

A

B

C

Abstract

Most population-based sexual health research in China excludes older adults. To fill the gap, this study aims to characterise sexual dissatisfaction among people aged 50 years or older from a nationwide, population-representative sample and to explore its association with physical, mental, and self-reported overall health indicators.

Data were collected as part of the China Family Panel Studies in 2020, led by the Institute of Social Science Survey of Peking University. Multivariable logistic regressions with robust estimators were used to investigate the association between sexual dissatisfaction and health indicators and potential demographic confounders.

Among the 8222 partnered Chinese adults aged 50 years or older (median age: 59, IQR: 54–66, 47% identified as women), 78% (6380/8222) reported being satisfied or very satisfied in their sex life. After adjusting for demographic variables, poor self-rated health status (aOR: 1.59, 95% CI: 1.42–1.77), experiencing depression symptoms (aOR: 2.02, 95% CI: 1.80–2.26), and having chronic diseases (aOR: 1.20, 95% CI: 1.07–1.36) were positively associated with sexual dissatisfaction in multivariable analyses. Among sociodemographic factors, younger age, female gender, and education level at senior high school or above were more likely to experience sexual dissatisfaction (all P < 0.05).

Based on our sample, more than one in five Chinese adults aged 50 years or older might face sexual dissatisfaction. Comorbidities common in older age likely exacerbate sexual dissatisfaction. Greater attention to sexual satisfaction research and sexual health programs among older adults is needed with respect to gender differences and chronic disease comorbidities.

Keywords: China, chronic disease, comorbidity, depression, middle aged and older adults, sexual health, sexual satisfaction, subjective health.

Introduction

In recent years, research has increasingly focused on sexual health of older adults. Studies from several settings, including China, the United Kingdom (UK), and the United States (US), found that many older people maintain their sex life throughout their lives.1–3 Sexual health underscores the importance of both the absence of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and the possibility of ‘having pleasurable and safe sexual experiences’.4 On the one hand, STIs among older adults have substantially increased in recent years. Data from the US Center for Disease Control and Prevention indicated that the prevalence of HIV among those aged 55 years or older in the US has increased from 207.9 cases per 100,000 people in 2010 to 420.7 per 100,000 in 2020 and that chlamydia and gonorrhoea follow similar trends.5 Similarly in China, the number of newly reported HIV cases among individuals aged 50 years has also shown an increasing trend annually, rising from 32,850 cases in 2015 to 51,856 cases in 2022.6 These pieces of evidence, together with a systematic review covering 1,149,767 elderly people living with HIV worldwide, suggest that older people’s sexual health is at increasing risk and warrants scholarly attention.7–9 Studies on STI epidemiology have provided evidence for disease control and improving related healthcare services; on the other hand, in terms of pleasurable sex, less studies have focused on one integral part of sexual health: sexual satisfaction among older adults.

The construct of sexual satisfaction can be operationally defined as ‘an effective response arising from one’s subjective evaluation of the positive and negative dimensions associated with one’s sexual relationship’.10 Previous studies from high-income settings suggested sexual dissatisfaction is common among an older population. One study from UK reported that, among the participants aged 55–74 years, more than half were dissatisfied with their sex life,2 which was similar to the situation in Korean older adults.11 Various factors were found to be associated with sexual dissatisfaction, such as age,12 gender,11 self-rated health,13 and specific health conditions, including diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, certain cancers, and depression.14–16 A study based in the UK confirmed that, among sexually active older adults, a number of common chronic health conditions and poorer self-rated general health are associated with decreased sexual satisfaction, with these associations varying by gender.16

Despite scholarly attention to sexual well-being in high-income countries, discussions on sexual satisfaction remains taboo in many low- and middle-income countries, including China. One of the two population-based epidemiological studies that we found on sexuality among older adults in China estimated that about half of them engage in varying forms of sexual activities and most remain interested in sex.3 The other study published in 2023, drawing on a population-based survey specifically designed to explore older adults’ sexual health, concluded that sexual satisfaction was associated with the general health situation, based on urban metropolitan samples from five cities in China.17 Those studies not only highlighted the scarcity of evidence available but also pointed to the necessity of continuing research on sexual dissatisfaction and its associated factors, including common diseases in older age, comorbidities, mental health, as well as self-rated health among the older population in China.

To further build evidence, this study used a national population-representative database to explore the association between the various dimensions of health status of Chinese adults aged 50 years or older and their sexual dissatisfaction. We focused on people aged 50 years or older because first they are oftentimes overlooked in sexual and reproductive health research in China, where the reproductive age is defined as 15–49 years and excludes adults who are 50 years old or older; second, adults who are 50 years old or older represent a growing age group both among the general Chinese population and among those living with HIV/AIDS in China.9,18 The purpose of this study is to describe sexual dissatisfaction prevalence among this specific sub-population and to explore its association with physical, mental, and self-reported overall health indicators, as well as patterns of comorbidities.

Methods

Study dataset

We used the wave in 2020 of the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) survey for this analysis. The CFPS is a nationally representative and longitudinal survey on Chinese society conducted biennially since 2010 by the Institute of Social Science Survey at Peking University. Survey sites were chosen from 25 provinces or their administrative equivalents (municipalities and autonomous regions) in China.19 This multidisciplinary survey covered various domains of questions, including economic activities, education, family relations and dynamics, population migration, and health. The questionnaire used in 2020 for the first time asked about participants’ sexual satisfaction in the survey’s Marriage Module (presented to married or partnered individuals). These data provided a unique opportunity to explore the sexual satisfaction at a population level. The participants were selected using a probability proportional to size sampling method with implicit stratification to achieve nationwide representativeness. All subsamples were obtained through three stages: 1) the primary sampling unit, which was either an administrative district (in urban areas) or a county (in rural areas); the second-stage sampling unit, which was either a neighbourhood community (in urban areas) or an administrative village (in rural areas); and 3) the third-stage final sampling unit, which was the household. It is important to note that the CFPS database integrated both rural and urban populations in sampling.19

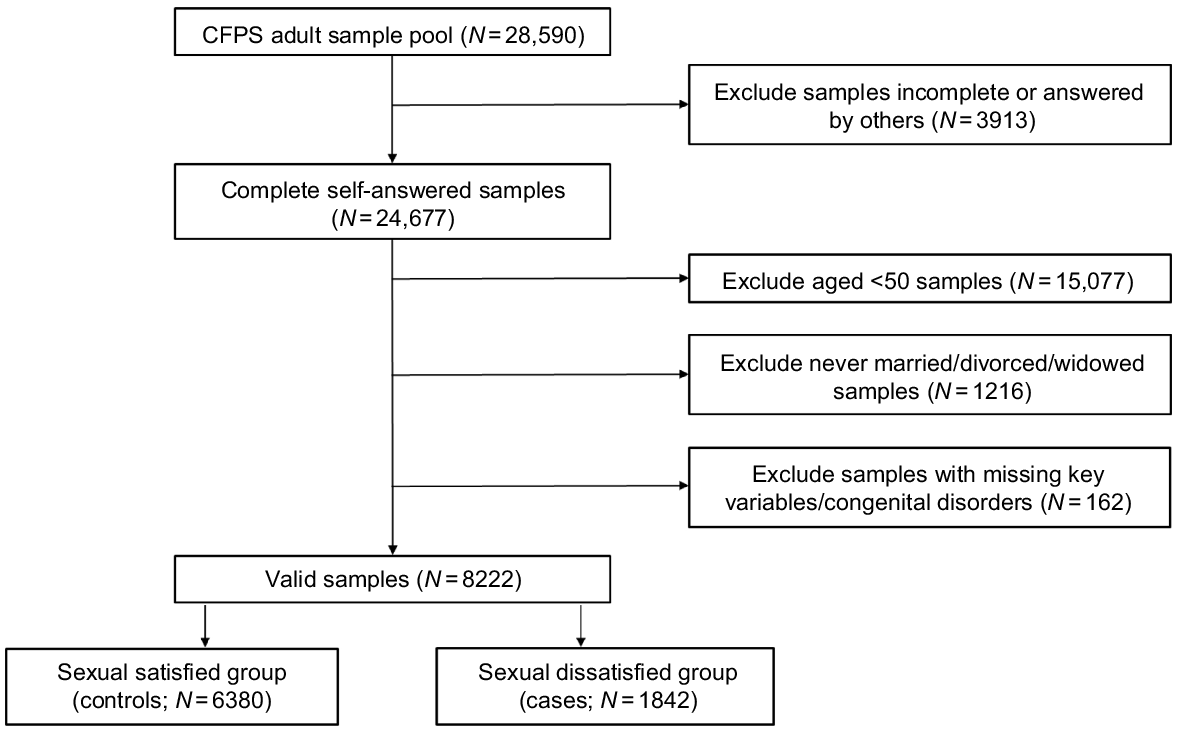

In this study, we defined participant eligibility according to five factors: 1) participants were included in the Individual Adult database 2020 dataset, 2) they were aged 50 years or older, 3) they were in a partnership (married or cohabitating with a partner), and 4) they had valid self-reported responses for sexual satisfaction. Additionally, participants with congenital anomalies and those unable to consent to answer survey questions were excluded from the analysis (n = 5). Ultimately, a total of 8222 valid responses were included, which were then categorised into the sexual dissatisfied group (cases) and the sexual satisfied group (controls) based on their responses to the survey. A detailed illustration of the sample selection process can be found in Fig. 1.

Measures

Individuals’ sexual satisfaction was often assessed using self-report questionnaires.20 In previous studies, several sexual satisfaction questionnaires used multiple items,15,21 but previous research in China indicated that a single-item measure is sufficient.22 Therefore, sexual satisfaction was measured by the question: ‘How satisfied are you with the sex life of your current marriage/cohabitation?’ with response options ranging from 1 to 5 (1 for very dissatisfied and 5 for very satisfied). To account for potential bias in self-reporting, as older individuals in China might embellish or defend themselves when evaluating aspects of life that influence their self-esteem significantly,23 we classified individuals who rated 1, 2, or 3 as cases with sexual dissatisfaction and those who rated 4 or 5 as controls with sexual satisfaction, which is consistent with previous research.17,24

The health status of older adults were assessed across three dimensions: 1) subjective health, 2) physical health, and 3) mental health. Subjective health was evaluated through self-rating, wherein individuals who self-rated as ‘totally healthy/very healthy/healthy’ were categorised as ‘healthy’, whereas those who self-rated as ‘somewhat unhealthy/unhealthy’ were classified as ‘unhealthy’. Physical health status primarily relied on the reported diagnosis of chronic diseases, which was determined by the question: ‘In the last 6 months, have you been diagnosed with a chronic disease by a doctor?’, with a binary response (1 for ‘yes’ and 0 for ‘no’). In the survey, participants were asked to specify two major types of chronic diseases (see Table 1 for examples) diagnosed by their doctors. We draw on the typology of International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision (ICD-11) Mortality and Morbidity Statistics to group self-reported diseases in CFPS into disease clusters used in this study.25 For clarity of expression, we defined ‘A × B’ as ‘suffering A and B at the same time’. Psychological health was assessed through the presence of symptoms suggestive of depression, using the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; 8 items) questionnaire. Positive indicators of depression were reversely coded, and the depression scale options in the database were as follows: ‘0. hardly ever (less than 1 day), 1. some of the time (1–2 days), 2. often (3–4 days), 3. most of the time (5–7 days)’, with a maximum score of 24. According to the international criterion,26,27 depression was indicated at and above a score of 8, corresponding to the 20th percentile for the CFPS adults. CES-D has been tested in a previous study and has been demonstrated as suitable for use among the Chinese older population.28

Furthermore, control variables were selected, including age, sex, urban–rural distribution and education attainment (no formal education/elementary school/junior high school/senior high school, technical secondary school, or above). Among them, sex was referred to the biological sex at birth but did not capture the diversity of sex, including intersex. Due to this limitation in data, in our analysis, sex is included as a binary variable. The questionnaires used for this study can be found on the CFPS official website.29

Statistical analysis

Participant characteristics were summarised using the mean, median, standard deviation (s.d.) and interquartile range for continuous variables, and frequency with proportions for categorical variables to explore the distribution of sexual dissatisfaction and other key variables. Bivariate analyses were conducted, and subsequently, multivariable logistic regressions with robust variance estimators were used to investigate the association of sexual dissatisfaction with subjective health, physical health, and psychological health, while adjusting for control variables, including age, sex, urban or rural residence, and education level. Marital status was not included in the model, as we defined eligibility as married or partnered individuals and the number of unmarried but partnered participants in the sample was few. The results were reported in terms of adjusted odds ratios (aORs) along with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Furthermore, sub-group analyses were conducted to examine differences between generation cohorts (50–59 years old/60–69 years old/≥70 years old) and sex (male/female). Also, we analysed the associations between comorbidities and sexual dissatisfaction among the sub-group who had diseases in the circulatory system, with the most common disease cluster reported in the data. Missingness in data is less than 2%, so we employed complete case analysis.

All statistical analyses were performed using Stata statistical software, ver. 14.0.30

Results

Table 1 presents the distribution of sexual dissatisfaction, health status, and demographic characteristics among married or partnered adults aged 50 years or older and the results from bivariate logistic regression analyses. The analytical sample included 3893 females (47.3%) and 4329 males (52.7%), demonstrating a relatively even distribution, which was also seen between urban (48.5%) and rural (51.5%) areas. The median age of participants was 59 years (interquartile range: 54–66 years), with 84.2% of the samples aged below 70 years. The vast majority (99.5%) of partnered participants aged 50 years or older were married. Concerning education, participants with no formal education, elementary school, junior high school, and senior high school (or technical secondary school) or above accounted for 30.0%, 24.6%, 27.9%, and 17.5% respectively.

| Independ variables | Overall (N = 8222) | Sexual dissatisfied (N = 1842) | Control (N = 6380) | OR (95%CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| Age (years)A | 0.98 (0.98–0.99) | |||||||

| 50–59 | 4170 | 50.7 | 1022 | 24.5 | 3148 | 75.5 | ||

| 60–69 | 2749 | 33.4 | 599 | 21.8 | 2150 | 78.2 | ||

| ≥70 | 1303 | 15.8 | 221 | 17.0 | 1082 | 83.0 | ||

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 3893 | 47.3 | 1066 | 27.4 | 2827 | 72.6 | 1.00 | |

| Male | 4329 | 52.7 | 776 | 17.9 | 3553 | 82.1 | 0.58 (0.52–0.64) | |

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Married | 8185 | 99.5 | 1828 | 22.3 | 6357 | 77.7 | ||

| Cohabited | 37 | 0.5 | 14 | 37.8 | 23 | 62.2 | ||

| Urban/rural | (n/8166)B | |||||||

| Rural | 4208 | 51.5 | 905 | 21.5 | 3303 | 78.5 | 1.00 | |

| Urban | 3958 | 48.5 | 923 | 23.3 | 3035 | 76.7 | 1.11 (1.00–1.23) | |

| Education completed | ||||||||

| No formal education | 2463 | 30.0 | 549 | 22.3 | 1914 | 77.7 | 1.00 | |

| Elementary school | 2026 | 24.6 | 422 | 20.8 | 1604 | 79.2 | 0.92 (0.79–1.06) | |

| Junior high school | 2292 | 27.9 | 516 | 22.5 | 1776 | 77.5 | 1.01 (0.88–1.16) | |

| Senior high school, technical secondary school, or above | 1441 | 17.5 | 355 | 24.6 | 1086 | 75.4 | 1.14 (0.98–1.33) | |

| Self-rated health status | (n/8221)C | |||||||

| Healthy | 5192 | 63.2 | 1010 | 19.5 | 4182 | 80.5 | 1.00 | |

| Unhealthy | 3029 | 36.8 | 832 | 27.5 | 2197 | 72.5 | 1.57 (1.41–1.74) | |

| Depression symptomsD | (n/8139)E | |||||||

| Non-depression | 5772 | 70.9 | 1072 | 18.6 | 4700 | 81.4 | 1.00 | |

| Depression | 2367 | 29.1 | 751 | 31.7 | 1616 | 68.3 | 2.04 (1.83–2.27) | |

| Chronic disease | (n/8217)E | |||||||

| No chronic disease | 6248 | 76.0 | 1351 | 21.6 | 4897 | 78.4 | 1.00 | |

| Chronic disease | 1969 | 24.0 | 488 | 24.8 | 1481 | 75.2 | 1.19 (1.06–1.34) | |

| Neoplasms | 39 | 0.5 | 15 | 38.5 | 24 | 61.5 | ||

| Neoplasms of haematopoietic or lymphoid tissues | 11 | 0.1 | 3 | 27.3 | 8 | 72.7 | ||

| Malignant neoplasms, except primary neoplasms of lymphoid, haematopoietic, central nervous system or related tissues | 20 | 0.2 | 10 | 50.0 | 10 | 50.0 | ||

| In situ neoplasms, benign neoplasms, neoplasms of uncertain behaviour or neoplasms of unknown behaviour | 10 | 0.1 | 4 | 40.0 | 6 | 60.0 | ||

| Endocrine, nutritional or metabolic diseases, or diseases of the immune system | 353 | 4.3 | 80 | 22.7 | 273 | 77.3 | 1.02 (0.79–1.31) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 305 | 3.7 | 65 | 21.3 | 240 | 78.7 | ||

| Diseases of blood or blood-forming organs | 17 | 0.2 | 3 | 17.6 | 14 | 82.4 | ||

| Mental, behavioural or neurodevelopmental disorders | 17 | 0.2 | 6 | 35.3 | 11 | 64.7 | ||

| Diseases of nervous system | 43 | 0.5 | 15 | 34.9 | 28 | 65.1 | ||

| Diseases of visual system | 21 | 0.3 | 1 | 4.8 | 20 | 95.2 | ||

| Diseases of ear or mastoid process | 10 | 0.1 | 4 | 40.0 | 6 | 60.0 | ||

| Diseases of circulatory system | 1130 | 13.8 | 269 | 23.8 | 861 | 76.2 | 1.10 (0.95–1.27) | |

| Diseases of respiratory system | 144 | 1.8 | 34 | 23.6 | 110 | 76.4 | 1.07 (0.73–1.58) | |

| Diseases of digestive system | 293 | 3.6 | 74 | 25.3 | 219 | 74.7 | 1.18 (0.90–1.54) | |

| Diseases of genitourinary system | 87 | 1.1 | 31 | 35.6 | 56 | 64.4 | 1.94 (1.24–3.01) | |

| Diseases of female genital system | 16 | 0.2 | 6 | 37.5 | 10 | 62.5 | ||

| Diseases of male genital system | 19 | 0.2 | 7 | 36.8 | 12 | 63.2 | ||

| Diseases of urinary system | 52 | 0.6 | 18 | 34.6 | 34 | 65.4 | ||

| Diseases of skin | 20 | 0.2 | 7 | 35.0 | 13 | 65.0 | ||

| Diseases of musculoskeletal system or connective tissue | 384 | 4.7 | 107 | 27.9 | 277 | 72.1 | 1.36 (1.08–1.71) | |

| Other diseases or conditions | 75 | 0.9 | 18 | 24.0 | 57 | 76.0 | ||

| Comorbidity | 982 | 12.0 | 251 | 25.6 | 731 | 74.4 | 1.22 (1.05–1.42) | |

The overall prevalence of sexual dissatisfaction in the full sample was 22.4%. Females reported a higher percentage of experiencing dissatisfaction (27.4%) compared to males (17.9%). Additionally, the proportion of sexually dissatisfied individuals was lower among those aged ≥70 years (17.0%) compared with those aged 50–59 years (24.5%) and 60–69 years (21.8%).

Approximately 36.8% of participants self-rated their health as unhealthy, 24.0% reported having been diagnosed with chronic diseases, and 29.1% reported experiencing symptoms suggestive of depression. Among the chronic disease clusters reported, diseases of the circulatory system were the most common (13.8%), followed by diseases of the musculoskeletal system or connective tissue (4.7%); endocrine, nutritional or metabolic diseases, or diseases of the immune system (4.3%); diseases of the digestive system (3.6%); diseases of the respiratory system (1.8%); and diseases of the genitourinary system (1.1%). The prevalence of each remaining cluster of chronic diseases was less than 1% (See Table 1). Comorbidity was observed in more than one-tenth of the participants (12.0%). Table 2 illustrated that, apart from having two different types of circulatory diseases simultaneously (22.4% in sample with comorbidities), the most common combinations were endocrine, nutritional or metabolic diseases, or diseases of the immune system × diseases of the circulatory system (18.1% in sample with comorbidities) and diseases of the musculoskeletal system or connective tissue × diseases of the circulatory system (12.8% in sample with comorbidities).

| Comorbidity | Endocrine, nutritional or metabolic diseases, or diseases of immune system | Diseases of circulatory system | Diseases of respiratory system | Diseases of digestive system | Diseases of genitourinary system | Diseases of musculoskeletal system or connective tissue | OthersA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endocrine, nutritional or metabolic diseases, or diseases of immune system | 8 (0.8%) | |||||||

| Diseases of circulatory system | 178 (18.1%) | 220 (22.4%) | ||||||

| Diseases of respiratory system | 7 (0.7%) | 28 (2.9%) | 15 (1.5%) | |||||

| Diseases of digestive system | 14 (1.4%) | 58 (5.9%) | 10 (1.0%) | 26 (2.6%) | ||||

| Diseases of genitourinary system | 6 (0.6%) | 25 (2.5%) | 4 (0.4%) | 10 (1.0%) | 2 (0.2%) | |||

| Diseases of musculoskeletal system or connective tissue | 12 (1.2%) | 126 (12.8%) | 11 (1.1%) | 40 (4.1%) | 9 (0.9%) | 41 (4.2%) | ||

| Others | 12 (1.2%) | 57 (5.8%) | 5 (0.5%) | 20 (2.0%) | 10 (1.0%) | 18 (1.8%) | 10 (1.0%) |

Table 3 presents the results from multivariable logistic regression analyses on sexual dissatisfaction. The multivariable logistic regression models revealed significant negative associations between sexual dissatisfaction and age (aOR range: 0.98–0.99) and being male (aOR range: 0.57–0.60). Having attained senior high school, technical secondary school, or above education was positively associated with sexual dissatisfaction (aOR range: 1.26–1.40, compared to no formal education), although this association was not significant in previous bivariate analyses.

| Variables | Model1 | Model2 | Model3 | Model4 | Model5 | Model6 | Model7 | Model8 | Model9 | Model10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | ||

| Self-rated unhealthy (ref: healthy) | 1.59** | ||||||||||

| (1.42–1.77) | |||||||||||

| Depression (ref: non-depression) | 2.02** | ||||||||||

| (1.80–2.26) | |||||||||||

| Chronic disease (ref: no chronic disease) | 1.20** | ||||||||||

| (1.07–1.36) | |||||||||||

| Endocrine, nutritional or metabolic diseases, or diseases of immune system (ref: a.t.) | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| (0.78–1.29) | |||||||||||

| Diseases of circulatory system (ref: a.t.) | 1.11 | ||||||||||

| (0.96–1.29) | |||||||||||

| Diseases of respiratory system (ref: a.t.) | 1.17 | ||||||||||

| (0.79–1.74) | |||||||||||

| Diseases of digestive system (ref: a.t.) | 1.16 | ||||||||||

| (0.89–1.52) | |||||||||||

| Diseases of genitourinary system (ref: a.t.) | 1.99** | ||||||||||

| (1.28–3.09) | |||||||||||

| Diseases of musculoskeletal system or connective tissue (ref: a.t.) | 1.33* | ||||||||||

| (1.05–1.69) | |||||||||||

| Comorbidity (ref: a.t.) | 1.19* | ||||||||||

| (1.02–1.40) | |||||||||||

| Age (years) | 0.98** | 0.99** | 0.99** | 0.99** | 0.99** | 0.99** | 0.99** | 0.99** | 0.99** | 0.99** | |

| (0.98–0.99) | (0.98–1.00) | (0.98–0.99) | (0.98–0.99) | (0.98–0.99) | (0.98–0.99) | (0.98–0.99) | (0.98–0.99) | (0.98–0.99) | (0.98–0.99) | ||

| Male (ref: female) | 0.59** | 0.60** | 0.58** | 0.57** | 0.57** | 0.57** | 0.57** | 0.57** | 0.58** | 0.58** | |

| (0.53–0.66) | (0.54–0.67) | (0.52–0.64) | (0.51–0.64) | (0.51–0.64) | (0.51–0.64) | (0.51–0.64) | (0.51–0.64) | (0.52–0.64) | (0.52–0.65) | ||

| Urban (ref: rural) | 1.06 | 1.12* | 1.06 | 1.06 | 1.06 | 1.06 | 1.06 | 1.06 | 1.06 | 1.06 | |

| (0.95–1.19) | (1.00–1.25) | (0.95–1.18) | (0.95–1.18) | (0.95–1.18) | (0.95–1.18) | (0.95–1.18) | (0.95–1.18) | (0.95–1.18) | (0.95–1.18) | ||

| Elementary school (ref: no formal education) | 1.03 | 1.04 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.01 | 1.01 | |

| (0.89–1.20) | (0.89–1.21) | (0.87–1.17) | (0.87–1.17) | (0.87–1.17) | (0.87–1.17) | (0.87–1.17) | (0.87–1.17) | (0.87–1.17) | (0.87–1.17) | ||

| Junior high school (ref: no formal education) | 1.17* | 1.22** | 1.12 | 1.11 | 1.11 | 1.11 | 1.12 | 1.11 | 1.12 | 1.11 | |

| (1.01–1.36) | (1.05–1.42) | (0.96–1.29) | (0.96–1.29) | (0.96–1.29) | (0.96–1.29) | (0.96–1.29) | (0.96–1.29) | (0.97–1.30) | (0.96–1.29) | ||

| Senior high school, technical secondary school, or above (ref: no formal education) | 1.37** | 1.40** | 1.26** | 1.26** | 1.26** | 1.26** | 1.26** | 1.26** | 1.27** | 1.26** | |

| (1.15–1.62) | (1.18–1.66) | (1.07–1.49) | (1.07–1.49) | (1.07–1.49) | (1.07–1.49) | (1.07–1.49) | (1.07–1.49) | (1.08–1.50) | (1.07–1.49) |

a.t., absence thereof.

**P < 0.01, *P < 0.05.

Regarding health characteristics, after adjusting for demographic variables, poor self-rated health status (aOR: 1.59, 95% CI: 1.42–1.77), experiencing symptoms suggestive of depression (aOR: 2.02, 95% CI: 1.80–2.26), and having chronic diseases (aOR: 1.20, 95% CI: 1.07–1.36) were positively associated with sexual dissatisfaction in both bivariate and multivariable analyses. Among the top six common chronic disease clusters, only diseases of the genitourinary system (aOR: 1.99, 95% CI: 1.28–3.09) and diseases of the musculoskeletal system or connective tissue (aOR: 1.33, 95% CI: 1.05–1.69) exhibited significant associations with sexual dissatisfaction compared to their respective reference groups not reporting such diseases. Moreover, the presence of comorbidities of any chronic diseases was an independent risk factor for sexual dissatisfaction (aOR: 1.19, 95% CI: 1.02–1.40). Furthermore, among those with diseases of the circulatory system, the presence of diseases of the genitourinary system (aOR: 2.61, 95% CI: 1.18–5.77) or diseases of the musculoskeletal system or connective tissue (aOR: 1.57, 95% CI: 1.04–2.39) were associated with increased likelihood of sexual dissatisfaction (see Table 4).

| Comorbidity (diseases of circulatory system×) | Model1 | Model2 | Model3 | Model4 | Model5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endocrine, nutritional or metabolic diseases, or diseases of immune system | Diseases of respiratory system | Diseases of digestive system | Diseases of genitourinary system | Diseases of musculoskeletal system or connective tissue | ||

| aOR | 0.73 | 0.42 | 1.40 | 2.61* | 1.57* | |

| (0.49–1.09) | (0.12–1.44) | (0.78–2.53) | (1.18–5.77) | (1.04–2.39) | ||

| aOR (male) | 0.42* | 0.69 | 0.71 | 0.99 | 2.60** | |

| (0.19–0.94) | (0.16–3.01) | (0.24–2.16) | (0.21–4.66) | (1.35–5.00) | ||

| aOR (female) | 0.93 | 0.22 | 2.14 | 4.52** | 1.16 | |

| (0.57–1.53) | (0.03–1.77) | (1.00–4.60) | (1.47–13.89) | (0.69–1.96) |

**P < 0.01, *P < 0.05.

Tables 5–9 presented subgroup analysis results of multivariable logistic regression analyses stratified by sex (Tables 5 and 6) and by age strata (Tables 7, 8 and 9), respectively. Specifically, for males, sexual dissatisfaction was positively associated with diseases of the musculoskeletal system or connective tissue (aOR: 1.84, 95% CI: 1.27–2.67). In contrast, no significant association was observed between sexual dissatisfaction and comorbidity, age, and education level in the male group. For females, diseases of the digestive system (aOR: 1.42, 95% CI: 1.01–1.99), diseases of the genitourinary system (aOR: 2.18, 95% CI: 1.21–3.94), and comorbidity (aOR: 1.23, 95%CI: 1.01–1.49) were positively associated with sexual dissatisfaction. We further found differences by sex in the association between sexual dissatisfaction and comorbidities among those who had diseases of the circulatory system (see Table 4). Specifically, we found that for males, compared to having only diseases of the circulatory system, their combination with the cluster ‘endocrine, nutritional or metabolic diseases, or diseases of the immune system’ (aOR: 0.42, 95% CI: 0.19–0.94) and their combination with disease cluster of the musculoskeletal system or connective tissue (aOR: 2.60, 95% CI: 1.35–5.00) were associated with sexual dissatisfaction, whereas for females, the combination of diseases of the circulatory system × diseases of the genitourinary system (aOR: 4.52, 95% CI: 1.47–13.89) were identified as independent risks of sexual dissatisfaction.

| Variables | Model1 | Model2 | Model3 | Model4 | Model5 | Model6 | Model7 | Model8 | Model9 | Model10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | ||

| Self-rated unhealthy (ref: healthy) | 1.66** | ||||||||||

| (1.44–1.92) | |||||||||||

| Depression (ref: non-depression) | 2.10** | ||||||||||

| (1.81–2.44) | |||||||||||

| Chronic disease (ref: no chronic disease) | 1.17* | ||||||||||

| (1.00–1.38) | |||||||||||

| Endocrine, nutritional or metabolic diseases, or diseases of immune system (ref: a.t.) | 1.08 | ||||||||||

| (0.78–1.51) | |||||||||||

| Diseases of circulatory system (ref: a.t.) | 1.12 | ||||||||||

| (0.92–1.36) | |||||||||||

| Diseases of respiratory system (ref: a.t.) | 1.20 | ||||||||||

| (0.67–2.15) | |||||||||||

| Diseases of digestive system (ref: a.t.) | 1.42* | ||||||||||

| (1.01–1.99) | |||||||||||

| Diseases of genitourinary system (ref: a.t.) | 2.18** | ||||||||||

| (1.21–3.94) | |||||||||||

| Diseases of musculoskeletal system or connective tissue (ref: a.t.) | 1.11 | ||||||||||

| (0.83–1.49) | |||||||||||

| Comorbidity (ref: a.t.) | 1.23* | ||||||||||

| (1.01–1.49) | |||||||||||

| Age (years) | 0.98** | 0.99** | 0.98** | 0.98** | 0.98** | 0.98** | 0.98** | 0.98** | 0.98** | 0.98** | |

| (0.97–0.99) | (0.98–0.99) | (0.97–0.99) | (0.97–0.99) | (0.97–0.99) | (0.97–0.99) | (0.97–0.99) | (0.97–0.99) | (0.97–0.99) | (0.97–0.99) | ||

| Urban (ref: rural) | 1.05 | 1.10 | 1.05 | 1.05 | 1.05 | 1.05 | 1.05 | 1.05 | 1.05 | 1.05 | |

| (0.90–1.22) | (0.94–1.28) | (0.90–1.23) | (0.90–1.22) | (0.90–1.23) | (0.91–1.23) | (0.91–1.23) | (0.90–1.22) | (0.91–1.23) | (0.90–1.23) | ||

| Elementary school (ref: no formal education) | 1.04 | 1.03 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.01 | |

| (0.86–1.26) | (0.85–1.25) | (0.84–1.23) | (0.84–1.22) | (0.84–1.23) | (0.84–1.23) | (0.83–1.22) | (0.83–1.22) | (0.84–1.23) | (0.84–1.23) | ||

| Junior high school (ref: no formal education) | 1.17 | 1.20 | 1.11 | 1.10 | 1.11 | 1.10 | 1.11 | 1.10 | 1.11 | 1.11 | |

| (0.96–1.43) | (0.98–1.47) | (0.91–1.35) | (0.91–1.35) | (0.91–1.35) | (0.91–1.34) | (0.91–1.35) | (0.91–1.34) | (0.91–1.35) | (0.91–1.35) | ||

| Senior high school, technical secondary school, or above (ref: no formal education) | 1.58** | 1.63** | 1.45** | 1.44** | 1.44** | 1.45** | 1.45** | 1.45** | 1.45** | 1.45** | |

| (1.25–1.99) | (1.30–2.06) | (1.15–1.82) | (1.15–1.81) | (1.15–1.82) | (1.15–1.82) | (1.15–1.82) | (1.15–1.82) | (1.15–1.82) | (1.15–1.82) |

a.t., absence thereof.

**P < 0.01, *P < 0.05.

| Variables | Model1 | Model2 | Model3 | Model4 | Model5 | Model6 | Model7 | Model8 | Model9 | Model10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | ||

| Self-rated unhealthy (ref: healthy) | 1.49** | ||||||||||

| (1.26–1.76) | |||||||||||

| Depression (ref: non-depression) | 1.92** | ||||||||||

| (1.62–2.29) | |||||||||||

| Chronic disease (ref: no chronic disease) | 1.24* | ||||||||||

| (1.03–1.49) | |||||||||||

| Endocrine, nutritional or metabolic diseases, or diseases of immune system (ref: a.t.) | 0.89 | ||||||||||

| (0.59–1.34) | |||||||||||

| Diseases of circulatory system (ref: a.t.) | 1.11 | ||||||||||

| (0.87–1.40) | |||||||||||

| Diseases of respiratory system (ref: a.t.) | 1.13 | ||||||||||

| (0.66–1.94) | |||||||||||

| Diseases of digestive system (ref: a.t.) | 0.81 | ||||||||||

| (0.50–1.32) | |||||||||||

| Diseases of genitourinary system (ref: a.t.) | 1.73 | ||||||||||

| (0.87–3.44) | |||||||||||

| Diseases of musculoskeletal system or connective tissue (ref: a.t.) | 1.84** | ||||||||||

| (1.27–2.67) | |||||||||||

| Comorbidity (ref: a.t.) | 1.14 | ||||||||||

| (0.88–1.49) | |||||||||||

| Age (years) | 0.99* | 0.99 | 0.99* | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | |

| (0.98–1.00) | (0.98–1.00) | (0.98–1.00) | (0.98–1.00) | (0.98–1.00) | (0.98–1.00) | (0.98–1.00) | (0.98–1.00) | (0.98–1.00) | (0.98–1.00) | ||

| Urban (ref: rural) | 1.08 | 1.14 | 1.06 | 1.07 | 1.06 | 1.06 | 1.06 | 1.06 | 1.07 | 1.06 | |

| (0.92–1.26) | (0.97–1.34) | (0.91–1.25) | (0.91–1.25) | (0.91–1.25) | (0.91–1.25) | (0.91–1.25) | (0.91–1.25) | (0.91–1.26) | (0.91–1.25) | ||

| Elementary school (ref: no formal education) | 0.98 | 1.01 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | |

| (0.77–1.24) | (0.79–1.30) | (0.75–1.22) | (0.75–1.22) | (0.75–1.21) | (0.75–1.22) | (0.75–1.21) | (0.75–1.22) | (0.76–1.23) | (0.75–1.22) | ||

| Junior high school (ref: no formal education) | 1.13 | 1.20 | 1.07 | 1.08 | 1.07 | 1.08 | 1.07 | 1.08 | 1.09 | 1.07 | |

| (0.89–1.42) | (0.95–1.51) | (0.85–1.35) | (0.86–1.35) | (0.85–1.35) | (0.86–1.35) | (0.85–1.35) | (0.86–1.36) | (0.86–1.37) | (0.85–1.35) | ||

| Senior high school, technical secondary school, or above (ref: no formal education) | 1.17 | 1.21 | 1.09 | 1.09 | 1.09 | 1.09 | 1.09 | 1.09 | 1.11 | 1.09 | |

| (0.90–1.50) | (0.93–1.56) | (0.85–1.40) | (0.85–1.41) | (0.85–1.40) | (0.85–1.40) | (0.85–1.40) | (0.85–1.40) | (0.86–1.43) | (0.85–1.40) |

a.t., absence thereof.

**P < 0.01, *P < 0.05.

| Variables | Model1 | Model2 | Model3 | Model4 | Model5 | Model6 | Model7 | Model8 | Model9 | Model10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | ||

| Self-rated unhealthy (ref: healthy) | 1.70** | ||||||||||

| (1.46–1.97) | |||||||||||

| Depression (ref: non-depression) | 2.05** | ||||||||||

| (1.76–2.39) | |||||||||||

| Chronic disease (ref: no chronic disease) | 1.30** | ||||||||||

| (1.10–1.55) | |||||||||||

| Endocrine, nutritional or metabolic diseases, or diseases of immune system (ref: a.t.) | 1.26 | ||||||||||

| (0.87–1.83) | |||||||||||

| Diseases of circulatory system (ref: a.t.) | 1.13 | ||||||||||

| (0.89–1.44) | |||||||||||

| Diseases of respiratory system (ref: a.t.) | 0.90 | ||||||||||

| (0.48–1.70) | |||||||||||

| Diseases of digestive system (ref: a.t.) | 1.21 | ||||||||||

| (0.83–1.77) | |||||||||||

| Diseases of genitourinary system (ref: a.t.) | 2.53* | ||||||||||

| (1.22–5.23) | |||||||||||

| Diseases of musculoskeletal system or connective tissue (ref: a.t.) | 1.48* | ||||||||||

| (1.06–2.06) | |||||||||||

| Comorbidity (ref: a.t.) | 1.44** | ||||||||||

| (1.14–1.83) | |||||||||||

| Age (years) | 1.01 | 1.02 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.02 | 1.01 | 1.02 | 1.01 | 1.01 | |

| (0.99–1.04) | (0.99–1.04) | (0.99–1.04) | (0.99–1.04) | (0.99–1.04) | (0.99–1.04) | (0.99–1.04) | (0.99–1.04) | (0.99–1.04) | (0.99–1.04) | ||

| Male (ref: female) | 0.58** | 0.59** | 0.56** | 0.55** | 0.56** | 0.55** | 0.55** | 0.56** | 0.56** | 0.57** | |

| (0.50–0.67) | (0.50–0.68) | (0.48–0.65) | (0.48–0.64) | (0.48–0.64) | (0.48–0.64) | (0.48–0.64) | (0.48–0.65) | (0.48–0.65) | (0.49–0.66) | ||

| Urban (ref: rural) | 1.09 | 1.15 | 1.09 | 1.08 | 1.09 | 1.09 | 1.09 | 1.09 | 1.09 | 1.09 | |

| (0.94–1.27) | (0.98–1.34) | (0.94–1.27) | (0.93–1.26) | (0.93–1.27) | (0.93–1.27) | (0.93–1.27) | (0.93–1.27) | (0.94–1.27) | (0.93–1.27) | ||

| Elementary school (ref: No formal education) | 1.02 | 1.02 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 1.01 | |

| (0.82–1.26) | (0.83–1.27) | (0.81–1.24) | (0.81–1.23) | (0.81–1.23) | (0.81–1.23) | (0.81–1.23) | (0.81–1.23) | (0.81–1.24) | (0.81–1.24) | ||

| Junior high school (ref: No formal education) | 1.09 | 1.14 | 1.05 | 1.04 | 1.04 | 1.04 | 1.04 | 1.04 | 1.05 | 1.05 | |

| (0.89–1.35) | (0.93–1.40) | (0.85–1.29) | (0.85–1.28) | (0.85–1.28) | (0.85–1.28) | (0.85–1.28) | (0.85–1.28) | (0.86–1.29) | (0.85–1.29) | ||

| Senior high school, technical secondary school, or above (ref: No formal education) | 1.39** | 1.39** | 1.27* | 1.26 | 1.27 | 1.27 | 1.27* | 1.27* | 1.28* | 1.27* | |

| (1.09–1.77) | (1.09–1.76) | (1.00–1.62) | (1.00–1.60) | (1.00–1.61) | (1.00–1.61) | (1.00–1.61) | (1.00–1.61) | (1.01–1.63) | (1.00–1.61) |

a.t., absence thereof.

**P < 0.01, *P < 0.05.

| Variables | Model1 | Model2 | Model3 | Model4 | Model5 | Model6 | Model7 | Model8 | Model9 | Model10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | ||

| Self-rated unhealthy (ref: healthy) | 1.65** | ||||||||||

| (1.37–1.99) | |||||||||||

| Depression (ref: non-depression) | 2.10** | ||||||||||

| (1.73–2.56) | |||||||||||

| Chronic disease (ref: no chronic disease) | 1.05 | ||||||||||

| (0.86–1.29) | |||||||||||

| Endocrine, nutritional or metabolic diseases, or diseases of immune system (ref: a.t.) | 0.86 | ||||||||||

| (0.56–1.35) | |||||||||||

| Diseases of circulatory system (ref: a.t.) | 1.03 | ||||||||||

| (0.81–1.31) | |||||||||||

| Diseases of respiratory system (ref: a.t.) | 1.18 | ||||||||||

| (0.62–2.26) | |||||||||||

| Diseases of digestive system (ref: a.t.) | 1.17 | ||||||||||

| (0.76–1.80) | |||||||||||

| Diseases of genitourinary system (ref: a.t.) | 1.08 | ||||||||||

| (0.49–2.41) | |||||||||||

| Diseases of musculoskeletal system or connective tissue (ref: a.t.) | 1.25 | ||||||||||

| (0.84–1.87) | |||||||||||

| Comorbidity (ref: a.t.) | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| (0.77–1.29) | |||||||||||

| Age (years) | 1.00 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.01 | |

| (0.97–1.04) | (0.98–1.05) | (0.97–1.04) | (0.97–1.04) | (0.97–1.04) | (0.97–1.04) | (0.97–1.04) | (0.97–1.04) | (0.97–1.04) | (0.97–1.04) | ||

| Male (ref: female) | 0.62** | 0.64** | 0.60** | 0.60** | 0.60** | 0.60** | 0.60** | 0.60** | 0.60** | 0.60** | |

| (0.51–0.76) | (0.52–0.77) | (0.49–0.73) | (0.49–0.72) | (0.49–0.73) | (0.49–0.73) | (0.49–0.73) | (0.49–0.73) | (0.49–0.73) | (0.49–0.73) | ||

| Urban (ref: rural) | 1.07 | 1.13 | 1.06 | 1.06 | 1.06 | 1.06 | 1.06 | 1.06 | 1.06 | 1.06 | |

| (0.89–1.29) | (0.94–1.37) | (0.88–1.28) | (0.88–1.28) | (0.88–1.28) | (0.88–1.28) | (0.88–1.28) | (0.88–1.28) | (0.88–1.28) | (0.88–1.28) | ||

| Elementary school (ref: no formal education) | 1.14 | 1.14 | 1.12 | 1.12 | 1.12 | 1.12 | 1.12 | 1.12 | 1.12 | 1.12 | |

| (0.88–1.49) | (0.87–1.49) | (0.86–1.46) | (0.86–1.46) | (0.86–1.46) | (0.86–1.46) | (0.86–1.46) | (0.86–1.46) | (0.86–1.46) | (0.86–1.46) | ||

| Junior high school (ref: no formal education) | 1.32* | 1.37* | 1.24 | 1.24 | 1.24 | 1.24 | 1.24 | 1.24 | 1.24 | 1.24 | |

| (1.02–1.70) | (1.06–1.77) | (0.97–1.59) | (0.97–1.60) | (0.97–1.59) | (0.97–1.60) | (0.97–1.60) | (0.96–1.59) | (0.97–1.60) | (0.96–1.59) | ||

| Senior high school, technical secondary school, or above (ref: no formal education) | 1.16 | 1.23 | 1.08 | 1.08 | 1.08 | 1.08 | 1.08 | 1.08 | 1.08 | 1.08 | |

| (0.87–1.54) | (0.92–1.64) | (0.81–1.43) | (0.81–1.43) | (0.81–1.43) | (0.81–1.43) | (0.81–1.43) | (0.81–1.43) | (0.82–1.44) | (0.81–1.43) |

a.t., absence thereof.

**P < 0.01, *P < 0.05.

| Variables | Model1 | Model2 | Model3 | Model4 | Model5 | Model6 | Model7 | Model8 | Model9 | Model10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | aOR | ||

| Self-rated unhealthy (ref: healthy) | 1.10 | ||||||||||

| (0.82–1.49) | |||||||||||

| Depression (ref: non-depression) | 1.65** | ||||||||||

| (1.19–2.29) | |||||||||||

| Chronic disease (ref: no chronic disease) | 1.27 | ||||||||||

| (0.94–1.72) | |||||||||||

| Endocrine, nutritional or metabolic diseases, or diseases of immune system (ref: a.t.) | 0.82 | ||||||||||

| (0.45–1.48) | |||||||||||

| Diseases of the circulatory system (ref: a.t.) | 1.26 | ||||||||||

| (0.90–1.76) | |||||||||||

| Diseases of respiratory system (ref: a.t.) | 1.88 | ||||||||||

| (0.86–4.11) | |||||||||||

| Diseases of digestive system (ref: a.t.) | 0.90 | ||||||||||

| (0.39–2.04) | |||||||||||

| Diseases of genitourinary system (ref: a.t.) | 2.96** | ||||||||||

| (1.34–6.55) | |||||||||||

| Diseases of musculoskeletal system or connective tissue (ref: a.t.) | 1.02 | ||||||||||

| (0.54–1.94) | |||||||||||

| Comorbidity (ref: a.t.) | 1.10 | ||||||||||

| (0.77–1.57) | |||||||||||

| Age (years) | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.01 | |

| (0.97–1.05) | (0.97–1.05) | (0.97–1.05) | (0.97–1.05) | (0.97–1.05) | (0.97–1.05) | (0.97–1.05) | (0.97–1.05) | (0.97–1.05) | (0.97–1.05) | ||

| Male (ref: female) | 0.62** | 0.62** | 0.63** | 0.62** | 0.63** | 0.61** | 0.62** | 0.62** | 0.62** | 0.63** | |

| (0.45–0.85) | (0.45–0.85) | (0.46–0.86) | (0.45–0.85) | (0.46–0.86) | (0.44–0.83) | (0.46–0.85) | (0.45–0.84) | (0.46–0.85) | (0.46–0.86) | ||

| Urban (ref: rural) | 0.96 | 1.00 | 0.96 | 0.98 | 0.96 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.97 | |

| (0.71–1.31) | (0.74–1.37) | (0.71–1.31) | (0.72–1.33) | (0.71–1.31) | (0.72–1.33) | (0.71–1.32) | (0.71–1.32) | (0.71–1.32) | (0.71–1.31) | ||

| Elementary school (ref: no formal education) | 0.84 | 0.86 | 0.81 | 0.82 | 0.81 | 0.82 | 0.81 | 0.82 | 0.81 | 0.81 | |

| (0.57–1.22) | (0.59–1.26) | (0.56–1.19) | (0.56–1.19) | (0.56–1.18) | (0.56–1.19) | (0.56–1.18) | (0.56–1.20) | (0.56–1.18) | (0.56–1.18) | ||

| Junior high school (ref: no formal education) | 1.03 | 1.09 | 1.00 | 1.02 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.02 | 1.02 | 1.01 | 1.01 | |

| (0.67–1.61) | (0.70–1.70) | (0.65–1.56) | (0.66–1.59) | (0.65–1.57) | (0.65–1.57) | (0.65–1.58) | (0.65–1.59) | (0.65–1.58) | (0.65–1.57) | ||

| Senior high school, technical secondary school, or above (ref: no formal education) | 1.85* | 1.97** | 1.77* | 1.81* | 1.78* | 1.79* | 1.80* | 1.71* | 1.80* | 1.79* | |

| (1.14–2.98) | (1.22–3.19) | (1.10–2.85) | (1.13–2.92) | (1.11–2.85) | (1.11–2.88) | (1.12–2.90) | (1.06–2.74) | (1.12–2.90) | (1.11–2.87) |

a.t., absence thereof.

**P < 0.01, *P < 0.05.

In all age groups, experiencing symptoms suggestive of depression was consistently associated with sexual dissatisfaction (see Tables 7–9). However, among those aged 60–69 years, no significant association was found between sexual dissatisfaction and chronic diseases, comorbidity, or education level. For those aged ≥70 years, besides experiencing symptoms suggestive of depression, sexual dissatisfaction was only associated with diseases of the genitourinary system (aOR: 2.96, 95% CI: 1.34–6.55) among all health-related variables.

Discussion

To shed light on how to improve the quality of life for older people, this study attempted to provide information on sexual dissatisfaction and its association with various health measures of Chinese adults aged 50 years or older. The significance of this study compared to existing studies is threefold. First, the study utilised data from population-proportional sampling, which complements previous studies conducted among certain patient groups, within certain geographic regions, or via convenience sampling. Second, our focus shifted from STI clinical outcomes to persons and their well-being, and this patient-centred approach to define our outcome variable, sexual satisfaction, is meaningful to help understand important aspects of sexual health in older age. Third, the study population extends research from solely focusing on population of reproductive age to include those aged 50 years or older and to include diverse populations, such as rural participants.

Our findings suggest that sexual dissatisfaction is common among Chinese adults aged 50 years or older, especially among women. Compared with a recent study using data from five cities in China,17 the prevalence of sexual dissatisfaction found in our study is similar, and together with the lack of association between urban/rural residence and sexual dissatisfaction, we conclude that sexual dissatisfaction occurs similarly to urban and rural adults in China. Our finding, however, drew attention to the sex differences in sexual dissatisfaction among people aged 50 years or older, namely, more women experiencing sexual dissatisfaction than men. The sex differences in sexual dissatisfaction are also found in a study in the US, whereby women appear to be slightly less satisfied with their sex life at all age groups compared to male counterparts but more so in older ages.31 One possible explanation for the widening satisfaction gap among the elderly is that, during the aging process women may experience more biological changes brought on by menopause, such as vaginal dryness and dyspareunia.32 More importantly, the influence of sociocultural and sociodemographic factors on the gender differences in sexual dissatisfaction should be emphasised. One of the sociocultural and demographic factors is that women’s sexual prospects are restricted by the belief in inherent gender differences regarding women and men’s sexual roles.33 It is believed that older women’s sexuality is culturally devalued, which may affect their sexual self-image and lower their satisfaction with sex.34 Besides, a study has shown that for most middle-aged and older people in China, the marriage pattern where husbands are older than their wives is dominant.35 This age-disparate marriage pattern means that the partners of women are likely older and at risk of being in worse physical condition than women themselves, which can negatively affect women’s sexual satisfaction.36 Furthermore, a large amount of societal resources have been devoted to the industry of intervening at erectile dysfunction to support men’s sexual satisfaction, but less medical, psychological, or social support enhances women’s sexual satisfaction.37

Age also played a vital role in varying sexual dissatisfaction in our results. We found that sexual dissatisfaction was lower among participants older than 70 years of age compared with those aged 50–59 years in China. This may be due to lowered expectations about sex in older age.38 In the results reported in an earlier study,39 sexual desire declines with age among both men and women. Likewise, a survey among US population found that interest in sex dropped off significantly in the middle of the 60s.40 These together may explain why older age groups tend to have less sexual dissatisfaction due to their declined desire and realistic expectations. Additionally, a marriage and partnership associated with an overly dissatisfied sex life may lead to relationship dissolution over time, and those parted individuals will exit from the partnered subsample of CFPS, resulting in a higher percentage of participants being sexually satisfied in older age sub-groups.

Regarding chronic health status, we further proved that older adults with poor health status were more likely to report sexual dissatisfaction after adjusting for demographic variables. Specifically, we found that sexual dissatisfaction was positively associated with diseases of the musculoskeletal system or connective tissue for men. One possible explanation may be that the diseases of the musculoskeletal system or connective tissue can affect mobility, reducing sexual desire and limiting sexual activity.41 For women, diseases of the digestive system and diseases of the genitourinary system were positively associated with sexual dissatisfaction. Specifically, the link to genitourinary system diseases can be explained by the strong relationship between diseases of the genitourinary system and female sexual dysfunction, evident in previous literature,42 but the relationship between diseases of the digestive system and female sexual health has yet to be supplemented by future studies. Although literature suggests that diseases of the circulatory system as well as endocrine disorders are also associated with sexual functioning,43,44 in our study, associations between these diseases and sexual satisfaction were not observed.

An intriguing result is that although the associations between sexual dissatisfaction and poor self-rated health status and having chronic diseases are significant among the whole sample, the associations within different age groups were more complex. Among those aged 60–69 years, no significant correlation was found between sexual dissatisfaction and chronic disease. For those aged ≥70 years, poor self-rated health status and chronic diseases did not show significant associations with sexual dissatisfaction. One possible explanation for this finding is selection bias that the participants in our study may be generally physically and mentally healthy, and the substantially less healthy may have been lost to death, illness, or attrition during the longitudinal follow-up.45

Depression symptoms were also positively associated with sexual dissatisfaction among Chinese adults aged 50 years or older. Depression is common in China,46 especially among older adults.47 Our data suggest that depression symptoms were consistently associated with sexual dissatisfaction in all age groups and sex groups. Several pieces of evidence may elucidate these associations of depression to sexual dysfunction, such as the fact that depression may lead to insufficient lubrication, orgasmic dysfunction and erectile problems.48–50 One study concluded that stress, a major contributor to anxiety and depression, may be a primary cause of reduced sexual functioning among older people.51 Another cause for concern is that older individuals with symptoms suggestive of depression may be prescribed antidepressants, which can also induce adverse changes in sexual function.52

Limitation

One limitation of this study is that this research is cross-sectional in design so that causation in the relationships cannot be determined. Also, in the survey, gender was measured as a binary variable and therefore did not capture population diversity in terms of gender and sexuality. In addition, survey questions on sexual partnerships did not explicitly distinguish between same-sex or opposite-sex categories. In consultation with the implementers of the survey, we presumed that reported partnerships were exclusively heterosexual partnerships. Our key outcome variable, sexual dissatisfaction, was embedded in the Marriage Module (including cohabitating partnerships) of the survey, and we only questioned married or partnered individuals at the time of the survey. As a result, our findings may not be generalisable to individuals who reported being single but still sexually active. Our study, when measuring chronic diseases, replied on self-reported diseases without cross-validating them against medical records. Consequently, perception bias and recall bias may have led to morbidity misclassification. Additionally, the data collection in 2020 may have been influenced by the COVID-19 pandemic, potentially affecting the generalisability of the results. Further research is needed to validate the findings. Yet even with these limitations, we consider that this study fills a critical gap in Chinese evidence on sexual satisfaction in older age.

Conclusion

In conclusion, sexual dissatisfaction was linked to poor health status of Chinese people aged 50 years or older. Sexual health, especially sexual satisfaction, among older adults needs more research, especially among women. Healthcare practitioners and researchers may consider broadening their practice to include discussion and intervention on sexual dissatisfaction among older adults. For instance, commonly occurring chronic disorders can be used as an entry point for raising sexual health-related questions during clinical consultation.

Conflicts of interest

Joseph D. Tucker is a co-Editor-in-Chief of Sexual Health. To mitigate this potential conflict of interest they had no editor-level access to this manuscript during peer review. The authors have no further conflicts of interest to declare.

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 82304210).

Author contributions

Conceptualisation, YD and FY; study design, YD and FY; formal analysis, YD; data acquisition, YS; writing, YD (with inputs from FY, JDT and YS). All authors reviewed and revised the article. All authors read the final manuscript and approved submission.

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge all study participants who generously took the time to participate in the study. We also thank the Institute of Social Science Survey (ISSS) of Peking University for the approval to use the 2020 CFPS data. We thank Lijun Pei for her constructive feedback at early stage on study design.

References

1 Lindau ST, Schumm LP, Laumann EO, Levinson W, O’Muircheartaigh CA, Waite LJ. A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. N Engl J Med 2007; 357(8): 762-74.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

2 Erens B, Mitchell KR, Gibson L, Datta J, Lewis R, Field N, et al. Health status, sexual activity and satisfaction among older people in Britain: a mixed methods study. PLoS ONE 2019; 14(3): e0213835.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

3 Yang S, Yan E. Demographic and psychosocial correlates of sexual activity in older Chinese people. J Clin Nurs 2016; 25(5–6): 672-81.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

4 Ghebreyesus TA, Kanem N. Defining sexual and reproductive health and rights for all. Lancet 2018; 391(10140): 2583-5.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

5 CDC. National center for HIV, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB prevention. CDC; 2024. Available at https://gis.cdc.gov/grasp/nchhstpatlas/tables.html [cited 16 August 2023]

6 Tang H, Jin Y, Lyu F. HIV/AIDS epidemic in the elderly and prevention and control challenges in China. Chin J Epidemiol 2023; 44(11): 1669-72.

| Google Scholar |

7 Bhatta M, Nandi S, Dutta N, Dutta S, Saha MK. HIV care among elderly population: systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2020; 36(6): 475-89.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

8 Mpondo BCT. HIV infection in the elderly: arising challenges. J Aging Res 2016; 2016: 1-10.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

9 He N. Research progress in the epidemiology of HIV/AIDS in China. China CDC Wkly 2021; 3(48): 1022-30.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

10 Lawrance K-A, Byers ES. Sexual satisfaction in long-term heterosexual relationships: the interpersonal exchange model of sexual satisfaction. Pers Relatsh 1995; 2(4): 267-85.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

11 Kim O, Jeon HO. Gender differences in factors influencing sexual satisfaction in Korean older adults. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2013; 56(2): 321-6.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

12 Trompeter SE, Bettencourt R, Barrett-Connor E. Sexual activity and satisfaction in healthy community-dwelling older women. Am J Med 2012; 125(1): 37-43.e1.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

13 Stentagg M, Skär L, Berglund JS, Lindberg T. Cross-sectional study of sexual activity and satisfaction among older adult’s ≥60 years of age. Sex Med 2021; 9(2): 100316.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

14 García-Gómez B, García-Cruz E, Bozzini G, Justo-Quintas J, García-Rojo E, Alonso-Isa M, et al. Sexual satisfaction: an opportunity to explore overall health in men. Urology 2017; 107: 149-54.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

15 Heyne S, Taubenheim S, Dietz A, Lordick F, Götze H, Mehnert-Theuerkauf A. Physical and psychosocial factors associated with sexual satisfaction in long-term cancer survivors 5 and 10 years after diagnosis. Sci Rep 2023; 13(1): 2011.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

16 Lee DM, Nazroo J, O’Connor DB, Blake M, Pendleton N. Sexual health and well-being among older men and women in England: findings from the English longitudinal study of ageing. Arch Sex Behav 2016; 45(1): 133-44.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

17 Wang B, Peng X, Liang B, Fu L, Lu Z, Li X, et al. Sexual activity, sexual satisfaction and their correlates among older adults in China: findings from the sexual well-being (SWELL) study. Lancet Reg Health West Pac 2023; 39: 100825.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

18 Wei Y, Duan Z, Mei L, Jiang Q, Yuan X, Wang L, et al. Eye on China’s population development in the new era from the data of China’s seventh population census. J Xi’an Univ Financ Econ 2021; 34(5): 107-21.

| Google Scholar |

19 Xie Y, Hu J. An introduction to the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS). Chin Sociol Rev 2014; 47(1): 3-29.

| Google Scholar |

20 Luo Q, Wang H, Peng T. Review on influencing factors for sexual satisfaction. Chin J Human Sexuality 2013; 22(7): 106-11.

| Google Scholar |

21 Bazzichi L, Rossi A, Giacomelli C, Scarpellini P, Conversano C, Sernissi F, et al. The influence of psychiatric comorbidity on sexual satisfaction in fibromyalgia patients. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2013; 31: S81-5.

| Google Scholar | PubMed |

22 Tao P, Brody S. Sexual behavior predictors of satisfaction in a Chinese sample. J Sex Med 2011; 8(2): 455-60.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

23 Liu C, Xiao J, Geng X. Positive skewness of old people’s subjective well-being scores and its related factors. Chin J Gerontol 2003; 23(4): 204-6 [in Chinese with English title and abstract] Available at https://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/periodical/zglnxzz200304004.

| Google Scholar |

24 Blondeel K, Mirandola M, Gios L, Folch C, Noestlinger C, Cordioli M, et al. Sexual satisfaction, an indicator of sexual health and well-being? Insights from STI/HIV prevention research in European men who have sex with men. BMJ Glob Health 2024; 9(5): e013285.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

25 ICD. ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics. ICD; 2024. Available at https://icd.who.int/browse11/-m/enl [cited 23 December 2023]

26 Radloff LS. The use of the center for epidemiologic studies depression scale in adolescents and young adults. J Youth Adolesc 1991; 20(2): 149-66.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

27 Zhou Q, Fan L, Yin Z. Association between family socioeconomic status and depressive symptoms among Chinese adolescents: evidence from a national household survey. Psychiatry Res 2018; 259: 81-8.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

28 Boey KW. Cross-validation of a short form of the CES-D in Chinese elderly. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1999; 14(8): 608-17.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

29 CFPS. China Family Panel Studies. CFPS; 2024. Available at https://www.isss.pku.edu.cn/cfps/ [cited 22 January 2024]

32 Wong ELY, Huang F, Cheung AWL, Wong CKM. The impact of menopause on the sexual health of Chinese Cantonese women: a mixed methods study. J Adv Nurs 2018; 74: 1672-84.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

33 Carpenter LM, Nathanson CA, Kim YJ. Sex after 40?: gender, ageism, and sexual partnering in midlife. J Aging Stud 2006; 20(2): 93-106.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

34 Koch PB, Mansfield PK, Thurau D, Carey M. “Feeling frumpy”: the relationships between body image and sexual response changes in midlife women. J Sex Res 2005; 42(3): 215-23.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

35 Chen Y, Qin X. The effects of age gap on marital quality and stability: based on the 2013 CHARLS data. Stud Lab Econ 2019; 7(4): 53-79.

| Google Scholar |

37 Zhang EY. Switching between traditional chinese medicine and viagra: cosmopolitanism and medical pluralism today. Med Anthropol 2007; 26(1): 53-96.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

38 Huang AJ, Subak LL, Thom DH, Van Den Eeden SK, Ragins AI, Kuppermann M, et al. Sexual function and aging in racially and ethnically diverse women: sexual function and aging in diverse women. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009; 57(8): 1362-8.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

39 Kontula O, Haavio-Mannila E. The impact of aging on human sexual activity and sexual desire. J Sex Res 2009; 46(1): 46-56.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

40 Lindau ST, Gavrilova N. Sex, health, and years of sexually active life gained due to good health: evidence from two US population based cross sectional surveys of ageing. BMJ 2010; 340(mar09 2): c810.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

41 Rheaume C, Mitty E. Sexuality and intimacy in older adults. Geriatr Nurs 2008; 29(5): 342-9.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

42 McCabe MP, Sharlip ID, Lewis R, Atalla E, Balon R, Fisher AD, et al. Risk factors for sexual dysfunction among women and men: a consensus statement from the fourth international consultation on sexual medicine 2015. J Sex Med 2016; 13(2): 153-67.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

43 Dilixiati D, Cao R, Mao Y, Li Y, Dilimulati D, Azhati B, et al. Association between cardiovascular disease and risk of female sexual dysfunction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2024; 31(7): 782-800.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

44 Maggi M, Buvat J, Corona G, Guay A, Torres LO. Hormonal causes of male sexual dysfunctions and their management (Hyperprolactinemia, Thyroid Disorders, GH Disorders, and DHEA). J Sex Med 2013; 10(3): 661-77.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

45 DeLamater J, Hyde JS, Fong M-C. Sexual satisfaction in the seventh decade of life. J Sex Marital Ther 2008; 34(5): 439-54.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

46 Lu J, Xu X, Huang Y, Li T, Ma C, Xu G, et al. Prevalence of depressive disorders and treatment in China: a cross-sectional epidemiological study. Lancet Psychiatry 2021; 8(11): 981-90.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

47 Huang Y, Wang Y, Wang H, Liu Z, Yu X, Yan J, et al. Prevalence of mental disorders in China: a cross-sectional epidemiological study. Lancet Psychiatry 2019; 6(3): 211-24.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

48 Moreira Junior ED, Glasser D, Santos DBd, Gingell C. Prevalence of sexual problems and related help-seeking behaviors among mature adults in Brazil: data from the global study of sexual attitudes and behaviors. Sao Paulo Med J 2005; 123: 234-41.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

49 Johnson SD, Phelps DL, Cottler LB. The association of sexual dysfunction and substance use among a community epidemiological sample. Arch Sex Behav 2004; 33(1): 55-63.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

50 Dunn KM, Croft PR, Hackett GI. Association of sexual problems with social, psychological, and physical problems in men and women: a cross sectional population survey. J Epidemiol Community Health 1999; 53(3): 144-8.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

51 Laumann EO, Waite LJ. Sexual dysfunction among older adults: prevalence and risk factors from a nationally representative U.S. probability sample of men and women 57–85 years of age. J Sex Med 2008; 5(10): 2300-11.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

52 Clayton AH, Pradko JF, Croft HA, Montano CB, Leadbetter RA, Bolden-Watson C, et al. Prevalence of sexual dysfunction among newer antidepressants. J Clin Psychiatry 2002; 63(4): 357-66.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |