Primary healthcare providers’ knowledge, practices and beliefs relating to preventive sexual and reproductive health care for women from refugee and asylum-seeking backgrounds in Australia: a national cross-sectional survey

Natasha Davidson A * , Karin Hammarberg A and Jane Fisher AA

Abstract

Many refugee women and women seeking asylum arrive in high-income countries with unmet preventive sexual and reproductive health (SRH) care needs. Primary healthcare providers (HCPs) are usually refugee and asylum seekers’ first point of care. This study aimed to identify HCP characteristics associated with initiating conversations and discussing SRH opportunistically during other health interactions.

An anonymous online survey was distributed nationally to representatives of health professional organisations and Primary Health Networks. Hierarchical logistic regression analysed factors including HCP demographics, knowledge and awareness, perceived need for training and professional experience with refugee women were included in the models.

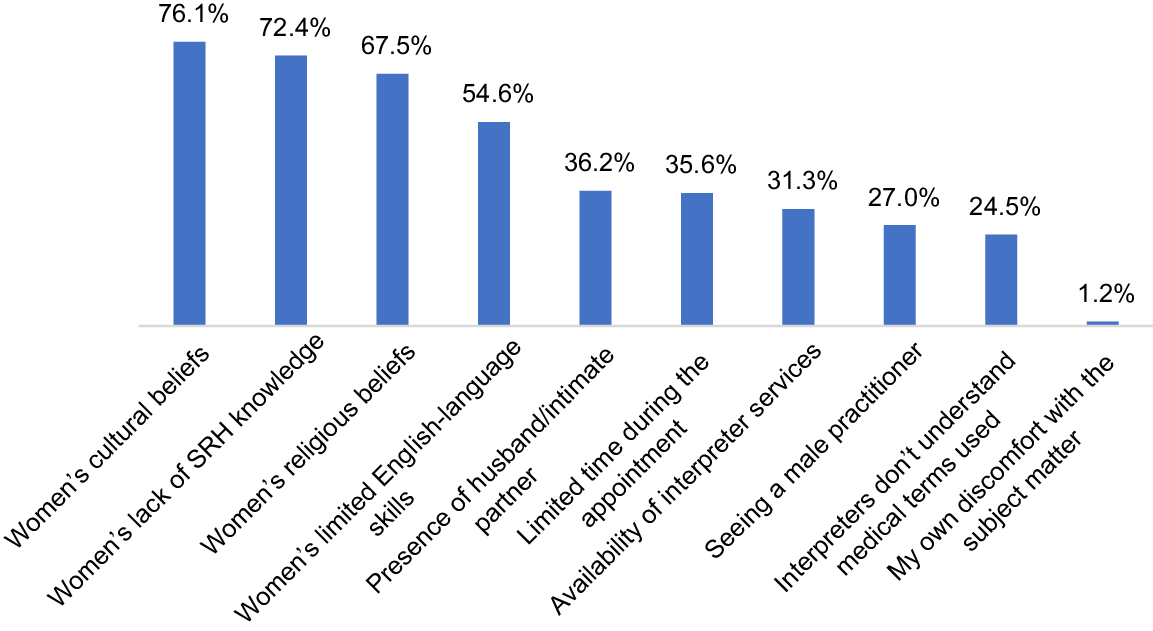

Among 163 HCPs, those initiating conversations ranged from 27.3% (contraceptive care) to 35.2% (cervical screening). Opportunistic discussions ranged from 26.9% (breast screening) to 40.3% (contraceptive care). Positively associated factors included offering care to refugee women or women seeking asylum at least once every 2 months 7.64 (95% CI 2.41;24.22, P < 0.001); 2.82 (95% CI 1.07;740, P < 0.05), working part-time 8.01 (95% CI 2.34;27.86, P < 0.001); 2.43 (95% CI 1.02;5.76, P < 0.05) and having over 10 years of practice in Australia 2.20 (95% CI 0.71;6.87, P < 0.001); 0.40 (95% CI 1.66;0.95, P < 0.05). Barriers identified by HCPs included women’s cultural beliefs (76%), lack of SRH knowledge (72.4%), religious beliefs (67.5%) and limited English-language skills (54.6%).

Direct professional experience, frequency of service provision, years of practice, and part time work positively influence HCPs’ SRH care practices. Enhancing bilingual health worker programs, outreach, education, and support for SRH and cultural competency training are essential to improving the preventive SRH care of refugee women and women seeking asylum.

Keywords: asylum seeker, Australia, health promotion, preventive health services, primary health care, refugee, reproductive health services, women’s health services.

Introduction

Forcibly displaced people are those who have crossed an international border to escape war, violence, conflict or persecution. Globally, it was estimated at the end of 2022 that 108.4 million people had been displaced over the past 15 years (UNHCR 2022). A person with a refugee background is someone who has fled their home country and is unable or unwilling to return to their country of origin owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted (UNHCR 1951). Refugees are people who have been granted protection whereas asylum seekers have sought international protection but their claims for refugee status are yet to be determined (UNHCR 2022). Resettlement in high-income countries offers safety, security, health and other human rights for refugees and asylum seekers. Refugees and asylum seekers arriving in high-income resettlement countries have complex physical, social and psychological health needs (Brandenberger et al. 2019). Provider–patient communication including initiating and maintaining a positive relationship during healthcare interactions, continuity of care and confidence in establishing a trustful relationship have been identified as crucial to meeting refugee and asylum seekers’ needs (Brandenberger et al. 2019).

Women and girls make up approximately 50% of refugee populations (UNHCR 2022) and face particular challenges accessing and utilising health care, including in relation to preventive sexual and reproductive health (SRH) care. For women, country of origin and in-transit experiences following displacement often lead to the loss of access to familiar health services, to social and family support and increased risk of sexual and gender-based violence (Patel et al. 2022). Upon arrival in a new country, these experiences can contribute to missed opportunities for vaccination and cancer screening and lack of access to contraceptive care.

Globally, healthcare provider (HCP) engagement with refugees and asylum seekers is increasing due to the growing numbers of people arriving through resettlement programs (UNHCR 2022). Primary healthcare services are usually the first point of care in resettlement countries for people who are refugees or asylum seekers (Cheng et al. 2015). They play an integral role in optimising health and wellbeing, offering health promotion and disease- prevention information (Timlin et al. 2020), assessing priority health needs and facilitating referrals to appropriate specialists (Lindenmeyer et al. 2016).

Australia has resettled over 950,000 refugees and asylum seekers since 1945 (Phillips 2015), accepting approximately 14,000 humanitarian entrants annually (Australian Government 2023a). Australia has a two-tiered healthcare system, with public and private sectors. The national Medicare system is a publicly funded universal healthcare program that provides Australian citizens and permanent residents with access to a range of medical services at little to no cost. In the public sector, Medicare provides universal access to primary healthcare services (Duckett 2015). Bulk billing is the practice where general practitioners (GPs) and nurse practitioners (NPs) bill the government directly for their services, without requiring a co-payment from patients; thereby making the consultation fee-free for the patient is a significant component of Medicare (Duckett 2015). Bulk billing contributes to preventive health care, as it encourages people to seek timely medical attention, leading to early diagnosis and intervention. Bulk billing is generally offered to refugees and eligible asylum seekers (Australian Government 2014). Where people seeking asylum are not covered by Medicare, in select services, costs are waived and they receive fee-free health care (Victorian Government and Department of Health 2023). People seeking asylum receive limited access to healthcare services through specific programs or community health services established by the government or non-governmental organisations. Australia’s private healthcare system is funded through private health insurance schemes, where insurance policies can be purchased to cover a portion of medical expenses related to hospitalisation, specialist care when in hospital, and ancillary services (Duckett 2015). Private health insurance does not cover primary health care or community healthcare services, which are provided in the public sector.

Provision of effective primary health care relies on it being delivered in a culturally competent and culturally safe way. Cultural competence refers to effectively interacting and working with individuals from diverse cultural backgrounds by understanding, respecting and adapting to cultural differences (Di Stefano et al. 2019). Cultural safety extends beyond cultural competence, addressing power disparities and societal factors, such as race and gender, and focuses on ensuring people from cultural minority groups feel safe, respected and in control when accessing healthcare services (Curtis et al. 2019).

People who are refugees or asylum seekers face several barriers to healthcare access. Unfamiliarity with the health system, language and communication challenges, low literacy and health literacy, lack of comfort and trust with HCPs (Brandenberger et al. 2019) and health information not being delivered in culturally and linguistically appropriate ways all limit access to care (Lindenmeyer et al. 2016).

Healthcare providers including GPs, NPs and practice nurses’ experiences of caring for people who are refugees or asylum seekers have also been explored. A qualitative synthesis of the challenges and facilitators for HCPs providing care to refugees found these related to the healthcare encounter (communication, cultural understanding), the local healthcare system (connecting with other services, resourcing) and the resettlement process (Robertshaw et al. 2017). Furthermore, HCPs may hold preconceived notions or biases towards certain religious or ethnic groups, leading to stereotyping or generalisations about the healthcare needs or preferences of refugee women belonging to those groups (Hall et al. 2015). Such biases might inadvertently influence the quality of care provided, as providers may not fully address the specific health concerns of refugee women and women seeking asylum from different religious or cultural backgrounds (Davidson et al. 2022). Although this research provides insights into the challenges HCPs experience in the different healthcare settings, it does not focus on HCPs’ specific experiences of providing preventive SRH care to refugee women and women seeking asylum in primary healthcare settings.

Most studies examining HCPs’ perspectives of caring for migrant and refugee women do not disaggregate data by immigrant and refugee groups (Mengesha et al. 2018b; Davidson et al. 2022). Evidence suggests that refugee women and women seeking asylum have worse preventive SRH outcomes compared to other immigrant women due to limited access to health care in their country of origin, previous traumatic experiences, cultural factors and their migration journey (Davidson et al. 2022).

Sexual and reproductive health care encompasses services, information and support related to family planning, antenatal and postnatal care, preventive health care (including sexually transmitted infections and other genital infection prevention), gynaecological and obstetric care, sexual education, awareness and consent, abortion services, reproductive disorder management, counselling and support (Scully et al. 2020). In this study, ‘preventive’ SRH care focuses on proactive measures to maintain and safeguard women’s SRH and includes contraceptive care, cervical screening, human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination, breast awareness and breast screening.

Limited evidence exists on the provision of SRH care from HCPs’ perspectives in high-income resettlement countries. One systematic qualitative review on the delivery of SRH care focused on HCP experiences regarding maternity and obstetric care and family planning for refugee women (Kasper et al. 2022). In Australia, to date, HCP perspectives of the barriers to the delivery of SRH care for refugee women have focused on the challenges of working with interpreters (Mengesha et al. 2018b) and provision of contraception (Mengesha et al. 2017). Less is known about primary HCPs’ experiences of providing preventive SRH care and health information about cervical screening tests, HPV vaccination, and breast health and breast screening.

Moreover, the research conducted in this field in Australia has predominantly relied on qualitative methodologies (Riggs et al. 2012; Mengesha et al. 2017). To our knowledge, no quantitative studies have been undertaken to investigate HCPs’ perceptions of the factors influencing their care of refugee women and women seeking asylum (Davidson et al. 2022). Consequently, there is a notable gap in the existing literature that directly examines the factors associated with enhancing the delivery of preventive SRH care to refugee women and women seeking asylum in Australia from the perspective of HCPs.

The aims of this study were to describe the HCP characteristics associated with: (1) initiating conversations on preventive SRH; and (2) discussing SRH opportunistically when women present for other health concerns.

Conversations between women and HCPs about SRH can occur in both planned and opportunistic contexts. In this study, preventive SRH conversations has been considered in two contexts: (1) initiating conversations by intentionally starting a dialogue within a dedicated SRH consultation, where the primary focus is on addressing SRH issues; and (2) opportunistically discussing SRH, where SRH topics are brought up during consultations for unrelated health issues.

Enhanced understanding of the HCP characteristics associated with initiating conversations on preventive SRH in clinical practice and discussing SRH opportunistically has the potential to improve patient-centred care, access to preventive SRH practices for women, support HCP to optimise opportunistic SRH discussions, and inform training and continuing education programs.

Methods

Setting

The survey was conducted across all states and territories of Australia through an accessible online survey tool (Qualtrics, ver. 22, https://www.qualtrics.com). The survey was open between November 2022 and March 2023.

Participants and recruitment procedure

In this exploratory study, the authors aimed to investigate a phenomenon and gather preliminary data to better understand a topic about which little is known. Approximately 96,000 primary healthcare nurses and 26,600 GPs provide primary care in the community (Australian Government 2024). However, we acknowledge that the exact number of providers offering care to people with refugee and asylum-seeking backgrounds is not known. Despite this, the authors sought a nationally representative sample of primary HCPs and obtained as large a sample size as possible to maximise the chances of capturing meaningful insights and understanding the phenomenon under investigation.

Inclusion criteria were to be either a GP or a registered nurse (RN) (including NPs) practising in a primary care setting in Australia. General practitioners or RNs providing care to the general population and/or to women of reproductive age who are refugees or seeking asylum in Australia as part of their primary healthcare practice/service delivery were included. Representatives of 19 national- and state-based health professional organisations and 25 Primary Health Networks (PHNs) were contacted and asked to disseminate survey information. Australia’s PHNs are regional organisations designed to improve coordination, accessibility and effectiveness of primary health services in specific geographic areas (Australian Government 2023b). Communications representatives at each PHN nationally were contacted to disseminate information about the survey to their members through e-newsletters and social media. A diversity of viewpoints was sought by targeted sampling methods including contacting general practices, refugee health networks, SRH service organisations, family planning and women’s health organisations.

Detailed information about the study purpose, eligibility criteria and what participation involved was provided via an electronic link included in an introductory email sent to contacts in professional organisations and PHNs. One to two follow-up emails and/or phone calls were undertaken by the first author (ND) to encourage organisations to distribute the survey. Follow-up emails were sent to health professional organisation contacts to confirm if and when surveys were distributed.

Potential participants received the introductory email with the survey link from participating organisations. As participants clicked on the link, they were presented with the landing page of the survey. Potential participants were then presented with an explanatory statement outlining what the research involved, why they were invited to participate, procedure for consenting to participate in the project and withdrawing from the research, possible benefits and risks to participants and procedure for maintaining confidentiality.

Eligibility was based on answering ‘Yes’ to the question ‘Do you provide clinical care to women from refugee-like backgrounds in the practice you work in?’. After reading the participant information, those who were willing and eligible to participate could proceed by clicking on a web link or scanning a QR code to complete the survey.

The survey was hosted by Qualtrics (Provo, UT, USA). Respondents were informed that by completing the survey, they provided implied consent to participate. In respectful recognition of their time, participants could enter a draw for one AUD$50 gift card.

Data source

A study-specific survey was developed based on a systematic review of access to preventive SRH care for women who have been displaced, who are refugees or women seeking asylum (Davidson et al. 2022) and other studies of SRH needs of women in these groups. Other studies included those that did not meet the inclusion criteria for the systematic review (Mengesha et al. 2017) or were published after the review was completed (Davidson et al. 2024). The researchers’ refugee health experience also informed the development of the survey. Studies by Davidson et al. (2022), (2024) identified several factors impacting preventive SRH care access for refugee women and women seeking asylum. The barriers to healthcare access identified in these studies enabled the researchers to tailor survey questions to address the specific challenges faced by healthcare providers. Supplementary File S1 outlines how evidence informed the development of survey items.

The first author has a clinical nursing background and experience providing primary health care to refugee women and children in humanitarian aid settings. This first-hand experience offers valuable insights into the specific health needs, challenges and cultural considerations of refugee women. This ensured the survey content was relevant, addressing the unique aspects of providing care for this group of women. She was attuned to cultural nuances, preferences and potential sensitivities of caring for refugee women. This was essential in formulating survey questions and response options appropriate for HCPs. Her clinical background ensured the survey was feasible and practical for implementation in real-world, time-limited primary healthcare settings.

The survey explored primary HCPs’ knowledge, practices and beliefs of preventive SRH care needs of refugee women and women seeking asylum. It also assessed HCPs’ views about barriers to providing preventive SRH care to these groups of women. Data on five topics: contraceptive care, cervical screening, breast awareness, breast screening and HPV vaccination were collected. The outcomes of interest were: (1) who initiates SRH conversations (‘In most cases I do’, ‘In most cases women do’, ‘It’s rarely discussed’, or ‘It’s never discussed’); and (2) whether HCP discuss SRH opportunistically when women present for other health concerns (‘Yes’, ‘Sometimes’, ‘No’ or ‘Don’t know or unsure’). Potential explanatory factors included: (1) demographic characteristics; (2) HCPs’ self-reported knowledge (e.g. ‘Please rate your level of knowledge in relation to: (a) contraceptive care, (b) cervical screening, (c) breast awareness, (d) breast screening, and (e) HPV vaccination’); (3) HCPs’ awareness of women’s understanding of their preventive SRH care needs; (4) HCPs’ perceived need for training; and (5) characteristics of direct professional experience (e.g. frequency of consultation with refugee women and women seeking asylum).

The survey questions, response options and their corresponding dichotomised categories are listed in Supplementary File S2. Demographic characteristics sought are shown in Table 1.

| Characteristic | Number (n) | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (n = 161) | |||

| Male | 30 | 18.6 | |

| Female | 131 | 81.4 | |

| Age group (n = 163) | |||

| ≤45 years | 92 | 56.4 | |

| >45 years | 71 | 43.6 | |

| Professional group (n = 158) | |||

| RNs | 91 | 57.6 | |

| GPs | 67 | 42.4 | |

| Languages spoken (n = 163) | |||

| English only | 102 | 62.6 | |

| English and other language | 61 | 37.4 | |

| Country of birth (n = 162) | |||

| Australia | 117 | 72.2 | |

| Other country | 45 | 27.8 | |

| Country of qualification (n = 161) | |||

| Australia | 130 | 80.7 | |

| Outside of Australia | 31 | 19.3 | |

| Years practising in Australia (n = 160) | |||

| ≤10 | 66 | 41.3 | |

| >10 | 94 | 58.8 | |

| Geographic location (n = 160) | |||

| Regional/rural/remote | 63 | 39.4 | |

| Metropolitan | 97 | 60.6 | |

| Type of organisation (n = 159) | |||

| GP practice | 26 | 16.4 | |

| Other health service | 133 | 83.6 | |

| Hours worked per week (n = 159) | |||

| Part time ≤32 | 69 | 43.4 | |

| Full time >32 | 90 | 56.6 | |

| Frequency of consultation with refugee women and women seeking asylum (n = 168) | |||

| Not often (≤ every 2 months) | 74 | 39.8 | |

| Often (> every 2 months) | 112 | 60.2 | |

| Fee for service billing arrangements (n = 134) | |||

| Patient co-payment | 24 | 17.9 | |

| No patient co-payment | 110 | 82.1 | |

| Offer fee-free health care to asylum seekers (n = 156) | |||

| No | 20 | 12.8 | |

| Yes | 136 | 87.2 | |

| Offer female interpreter (n = 163) | |||

| No | 47 | 28.8 | |

| Yes | 116 | 71.2 | |

| Offer female provider (n = 165) | |||

| No | 33 | 20.0 | |

| Yes | 132 | 80.0 | |

The survey was pilot tested by 10 experienced HCPs to determine if questions were valid, clear and understandable. Seven RNs and three GPs with extensive experience of providing SRH care to refugee women and women seeking asylum participated in the piloting of the survey. Following feedback, some response options were changed. The final survey is available in Supplementary File S3. Pilot data were not included in the results.

Data management and analysis

Data were imported from Qualtrics to SPSS (ver. 25.0, IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA) for cleaning, checking and analysis. Not all respondents provided a response to all questions. Missing data were identified by running frequency tables for each variable to check for missing values. For missing data analysis, Little’s test was used to test the assumption that data were missing completely at random (MCAR) (Little 1988). This yielded a P-value of >0.05, indicating that there were no existing patterns in the missing data. No imputation of missing values was undertaken. Cases with >60% of missing values were excluded from analysis. The number of responses included in the analysis varied between questions. Frequencies and distributions of variables were analysed by descriptive statistics. Professional and demographic categorical variables were dichotomised. The two primary outcomes, ‘HCPs initiating conversations on SRH’ or ‘HCPs discussing SRH opportunistically’ were also dichotomised. Categorical variables were divided into two categories, dichotomised, based on a clinically meaningful and practical cut-off point. Each variable had four categories. Those categories with <10 data points in each were grouped together. Supplementary File S2 provides a description of the individual categorisation of each variable. This ensured there were enough data points in each of the resulting dichotomised groups to make certain that statistical analyses could be conducted effectively allowing for comparisons between two groups. Chi-square tests are generally used in data analysis to determine if there is a significant difference between two categorical variables (Sullivan 2012). As data management of primary outcome variables in this study involved grouping observations into categories, Chi-square tests were used to assess associations between the two outcomes of interest and professional and demographic variables.

Provider responses to questions that assessed HCPs knowledge and awareness of women’s perception of their preventive SRH care needs, perceived need for training, self-reported ability to provide culturally safe or competent care, and characteristics of direct professional experience with women are shown in Table 2. Mean scores for responses to questions related to HCPs views of refugee women’s preventive SRH were calculated across the five topics: contraceptive care, cervical screening, breast awareness, breast screening and HPV vaccination. The possible range for the resultant mean score was 0–3, with 0 indicating a low mean score or more negative responses across topics and 3 indicating a high mean score or more positive responses across topics (Table 2). Independent sample t-tests compare the means of two independent groups in order to determine if there is a significant difference between population means (Sullivan 2012). Using mean scores, independent t-tests were conducted to assess the associations between the two primary outcomes and the continuous variables related to HCPs knowledge, practices and beliefs.

| Responses to statements posed to healthcare providers | Mean | s.d. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | |||

| Refugee women and women seeking asylum request information about preventive SRH (Never = 0 to All the time = 3) | 1.02 | 0.703 | |

| Healthcare providers’ self-rated level of knowledge in relation to preventive SRH (None = 0 to Very good = 3) | 2.46 | 0.564 | |

| Self-rated comfort in providing culturally competent care to refugee women and women seeking asylum when discussing preventive SRH (Not comfortable = 0 to Very comfortable = 3) | 2.28 | 0.688 | |

| Beliefs | |||

| Women see out-of-pocket financial cost as a barrier to preventive SRH (None = 0 to All = 3) | 1.60 | 0.906 | |

| Perception of women’s awareness of preventive SRH (Not at all aware = 0 to Very aware = 3) | 1.27 | 0.846 | |

| Women’s religious beliefs reduce their uptake of health care with regard to preventive SRH (Does not = 0 to All the time = 3) | 1.56 | 0.860 | |

| Women face coercion from their husband/intimate partner that limits their autonomy or ability to make decisions about preventive SRH (Never = 0 to Always = 3) | 1.52 | 0.795 | |

| Being unmarried reduces a woman’s ability to make decisions about preventive SRH (Does not = 0 to All the time = 3) | 1.63 | 0.868 | |

Preventive SRH includes contraceptive care, cervical screening, breast awareness, breast screening and HPV vaccination.

Following bivariate analyses, covariates significantly associated with the primary outcomes or identified as relevant from previous research, were entered into two hierarchical logistic regression models (one for each of the two primary outcomes – HCPs initiating conversations on SRH and HCPs discussing SRH opportunistically). Hierarchical logistic regression analysis considers the variability of each potential explanatory factor, and thus allows for the cluster effects at different levels to be analysed within each model (Stryhn and Christensen 2014). Hierarchical logistic regression was used in this study to simultaneously account for potential influence of group effects and the effects of group-level predictors. The regression models included all relevant variables to control for confounding. Variables included professional group, language spoken, country of qualification, geographic location, HCPs’ knowledge and beliefs, HCPs’ perceived need for training, frequency of consultation, years practising in Australia, hours worked per week and being offered a female provider (Tables 3 and 4). The models were used to examine associations between the primary outcomes and covariates to establish separate and combined contributions to the variance. Covariates were categorised into five groups: (1) demographic characteristics; (2) HCP knowledge and awareness; (3) HCPs’ perceived need for training; (4) HCPs provision of culturally safe care; and (5) direct professional experience with refugee women or women seeking asylum. Change in pseudo R Square of each model as each group of covariates was added, was used to explain the contribution of the covariates to the two primary outcomes. The level of statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

| Covariates | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic variables | B (B coefficient) (95% CI) | B (95% CI) | B (95% CI) | B (95% CI) | |

| Professional group | Reference 2.08 (0.95;4.54) | Reference 1.49 (0.62;3.57) | Reference 1.54 (0.63;3.75) | Reference 1.60 (0.56;4.55) | |

| GPs | |||||

| RNs | |||||

| Language spoken | Reference 5.01 (2.16;11.6)*** | Reference 5.27 (2.00;13.86)*** | Reference 4.77 (1.80;12.84)** | Reference 2.78 (0.76;9.85) | |

| English and other language | |||||

| English only | |||||

| Country of qualification | Reference 1.26 (0.46;3.44) | Reference 1.24 (0.40;3.80) | Reference 1.24 (.41;3.97) | Reference 1.77 (0.46;6.83) | |

| Outside Australia | |||||

| Australia | |||||

| Geographic location | Reference 4.21 (1.83;9.69)*** | Reference 3.23 (1.32;7.84)** | Reference 2.86 (1.51;7.12)* | Reference 2.55 (0.85;7.65) | |

| Regional/rural/remote | |||||

| Metropolitan | |||||

| HCP knowledge and beliefs | |||||

| Self-rated SRH knowledge (mean score) | 1.73 (0.66;4.49) | 1.42 (0.52;3.87) | 2.18 (0.55;8.64) | ||

| Self-rated cultural competency (mean score) | 2.58 (1.19;5.56)* | 2.59 (1.14;5.88)* | 1.91 (0.74;4.92) | ||

| Perceptions of women’s SRH awareness (mean score) | 0.55 (0.32;0.94)* | 0.61 (0.34;1.07) | 0.70 (0.37;1.35) | ||

| HCPs’ perceived need for training | |||||

| HCPs’ request for SRH training (mean score) | 0.71 (0.17;3.01) | 2.31 (0.30;17.98) | |||

| HCPs’ request cultural awareness training | Reference 1.56 (0.29;8.37) | Reference 2.29 (0.29;18.06) | |||

| Yes | |||||

| No | |||||

| Direct professional experience with refugee women and women seeking asylum | |||||

| Frequency of consultation with refugee women and women seeking asylum | Reference 7.64 (2.41;24.22)*** | ||||

| Not often (≤ every 2 months) | |||||

| Often (> every 2 months) | |||||

| Years practising in Australia | Reference 2.20 (0.71;6.87)*** | ||||

| ≤10 | |||||

| >10 | |||||

| Hours worked per week | Reference 8.01 (2.34;27.86)*** | ||||

| Full time >32 | |||||

| Part time ≤32 | |||||

| Offer female provider | Reference 3.63 (0.70;18.61) | ||||

| No | |||||

| Yes | |||||

| Nagelkerke R2 | 0.23 | 0.39 | 0.40 | 0.59 | |

| Cox and Snell R2 | 0.17 | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.44 | |

*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

| Covariates | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic variables | B (B coefficient) (95% CI) | B (95% CI) | B (95% CI) | B (95% CI) | |

| Professional group | Reference 3.19 (1.52;6.70)** | Reference 2.91 (1.37;6.22)** | Reference 2.93 (1.37;6.27)** | Reference 2.61 (1.12;6.08)** | |

| GPs | |||||

| RNs | |||||

| Language spoken | Reference 1.17 (0.56;2.44) | Reference 1.15 (0.52;2.53) | Reference 1.11 (0.49;2.52) | Reference 0.68 (0.24;1.96) | |

| English and other language | |||||

| English only | |||||

| Country of qualification | Reference 1.31 (0.52;3.29) | Reference 1.33 (0.52;3.44) | Reference 1.33 (0.52;3.42) | Reference 1.36 (0.50;3.73) | |

| Outside Australia | |||||

| Australia | |||||

| Geographic location | Reference 1.30 (0.62;2.73) | Reference 1.18 (0.55;2.56) | Reference 1.15 (0.52;2.54) | Reference 1.01 (0.42;2.40) | |

| Regional/rural/remote | |||||

| Metropolitan | |||||

| HCP knowledge and beliefs | |||||

| Self-rated SRH knowledge (mean score) | 0.96 (0.41;2.24) | 0.93 (0.40;2.22) | 1.14 (0.44;2.97) | ||

| Self-rated cultural competency (mean score) | 1.42 (0.70;2.89) | 1.40 (0.69;2.86) | 1.44 (0.67;3.01) | ||

| Perceptions of women’s SRH awareness (mean score) | 0.87 (0.56;1.38) | 0.89 (0.56;1.41) | 0.85 (0.51;1.42) | ||

| HCPs’ perceived need for training | |||||

| HCPs’ request for SRH training (mean score) | 0.90 (0.27;3.01) | 1.55 (0.38;6.37) | |||

| HCPs’ request cultural awareness training | Reference 1.08 (0.28;4.17) | Reference 1.62 (0.37;7.13) | |||

| Yes | |||||

| No | |||||

| Direct professional experience with refugee women and women seeking asylum | |||||

| Frequency of consultation with refugee women and women seeking asylum | Reference 2.82 (1.07;7.40)* | ||||

| Not often (≤ every 2 months) | |||||

| Often (> every 2 months) | |||||

| Years practising in Australia | Reference 0.40 (1.66;0.95)* | ||||

| ≤10 | |||||

| >10 | |||||

| Hours worked per week | Reference 2.43 (1.02;5.76)* | ||||

| Full time >32 | |||||

| Part time ≤32 | |||||

| Offer female provider | Reference 1.72 (0.53;5.63) | ||||

| No | |||||

| Yes | |||||

| Nagelkerke R2 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.29 | |

| Cox and Snell R2 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.21 | |

*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Results

In total, 256 respondents clicked on the survey link. Of these, 61 stopped after the participant information, which stated only HCPs who provided care to refugee women or women seeking asylum were eligible to participate. Of the remaining 195 respondents, 27 completed <60% of questions and were excluded from analyses. A total of 168 completed most questions in each section and were included in the analyses.

Professional and demographic characteristics

Respondents’ professional and demographic characteristics are shown in Table 1. Most respondents were females working in community health 10.9% (n = 28), general practice 10.2% (n = 26), SRH 8.6%, (n = 22), refugee health 7.8% (n = 20), regional/remote health service 4.7% (n = 12) and family planning 3.1% (n = 8). Approximately 57.6% (n = 91) were employed as RNs, of which 8.2% (n = 21) were NPs. The majority were born 72.2% (n = 117) and trained 80.7% (n = 130) in Australia. Over half of the respondents were aged <45 years 56.4% (n = 92) and had been practising in Australia for >10 years 58.8% (n = 94). Most reported providing services to refugee women or women seeking asylum more often than every 2 months, 60.2% (n = 112), with 82.1% (n = 110) offering fee-free services to these groups of women. The sample was drawn from all Australian States and Territories, with 60.6% (n = 97) from metropolitan locations and 39.4% (n = 63) from regional, rural and remote locations.

Description of healthcare providers’ practices, knowledge and beliefs

The majority of respondents stated that they offered women a female interpreter 71.2% (n = 116) and choice about seeing a female provider 80.0% (n = 132) (Table 1).

Between 64.8% (n = 78) and 72.7% (n = 98) of respondents reported initiating conversations about preventive SRH (Table 5). In most cases, women rarely or never discussed contraceptive care 72.7% (n = 98), cervical screening 64.8% (n = 78), breast awareness 71.5% (n = 95), breast screening 67.6% (n = 85) or HPV vaccination 69.9% (n = 91). In contrast, in most cases, HCPs initiated conversations on contraceptive care 27.3% (n = 70) of the time, cervical screening 35.2% (n = 90) of the time, on breast awareness 28.5% (n = 73) of the time, breast screening 32.4 (n = 83) of the time and HPV vaccination 30.1% (n = 77) of the time.

| Who initiates conversations on preventive SRH with refugee women and women seeking asylum on preventive SRH? | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| In most cases women do/rarely or never discussed | In most cases I do | ||

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Contraceptive care (n = 168) | 98 (72.7) | 70 (27.3) | |

| Cervical screening (n = 168) | 78 (64.8) | 90 (35.2) | |

| Breast awareness (n = 168) | 95 (71.5) | 73 (28.5) | |

| Breast screening (n = 168) | 85 (67.6) | 83 (32.4) | |

| HPV vaccination (n = 168) | 91 (69.9) | 77 (30.1) | |

| Do you bring up preventive SRH opportunistically when refugee women and women seeking asylum present with other health concerns? | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No or sometimes | Yes | ||

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Contraceptive care (n = 164) | 62 (59.7) | 102 (40.3) | |

| Cervical screening (n = 165) | 77 (65.4) | 88 (34.6) | |

| Breast awareness (n = 164) | 76 (67.7) | 86 (34.3) | |

| Breast screening (n = 164) | 96 (73.1) | 68 (26.9) | |

| HPV vaccination (n = 163) | 77 (67.9) | 86 (34.1) | |

Between 26.9% (n = 68) and 40.3% (n = 102) of respondents reported bringing up preventive SRH opportunistically when women presented for other health concerns. Providers brought up preventive SRH opportunistically 40.3% (n = 102) of the time for contraceptive care, 34.6% (n = 88) of the time for cervical screening, 34.3% of the time (n = 86) for breast awareness, 26.9% of the time (n = 68) for breast screening and 34.1% of the time (n = 86) for HPV vaccination (Table 5).

Responses relating to HCPs’ knowledge and beliefs regarding SRH are shown in Table 2. Mean score for self-rated knowledge of preventive SRH suggests most (2.46, s.d. = 0.546) had a ‘moderate’ or ‘very good’ level of knowledge and were ‘moderately’ or ‘very comfortable’ providing culturally safe care (2.28, s.d. = 0.688). Mean scores suggest respondents believed women were ‘somewhat aware’ or ‘moderately aware’ of preventive SRH (1.27, s.d. = 0.846), but only ‘sometimes’ ask for information (1.02, s.d. = 0.703). Mean scores also indicated respondents believed women saw cost as a barrier to care ‘sometimes’ or ‘most of the time’ (1.60, s.d. = 0.906); women’s religious beliefs (1.56, s.d. = 0.860) and being unmarried ‘sometimes’ or ‘often reduced uptake’ of SRH (1.63, s.d. = 0.868) and that women face coercion from their husband or partner ‘sometimes’ or ‘most of the time’ (1.52, s.d. = 0.795).

Approximately two-thirds of respondents wanted further training on preventive SRH for refugee women or women seeking asylum. Respondents reported the need for further training on contraceptive care (71.5%), cervical screening (63.6%), breast awareness (67.3%), breast screening (64.8%) and HPV vaccination (66.1%). The majority of respondents (85.4%) also wanted further cultural awareness training.

Healthcare providers’ perceived barriers to providing preventive SRH to women

Fig. 1 displays the HCPs’ perceived barriers to providing preventive SRH care to refugee women and women seeking asylum. The most commonly cited barriers were women’s cultural beliefs, lack of SRH knowledge and religious beliefs. Over half (54.6%) perceived limited English-language skill as a barrier to care. Fewer believed the presence of a husband or intimate partner (36.2%), unavailability of interpreter services (31.3%), having a consultation with a male provider (27.0%) or interpreters not understanding medical terms (24.5%) were barriers to providing care.

Factors associated with initiating SRH conversations and discussing SRH opportunistically

Factors associated with initiating SRH conversations were: seeing refugee women or women seeking asylum more often than every 2 months, not charging patient co-payment for consultations, being a female provider, providers not speaking a language other than English, working in a practice where patients were offered the option of seeing a female provider, working in a metropolitan location, working in a general practice and working part-time (Table 6).

| Variables | Initiates conversations about SRH | P-values | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | |||

| Gender (n = 161) | |||

| Male | 4/30 (13) | <0.001 | |

| Female | 73/131 (56) | ||

| Professional group (n = 158) | |||

| RNs | 47/91 (52) | <0.001 | |

| GPs | 27/67 (40) | ||

| Languages spoken (n = 163) | |||

| English only | 59/102 (58) | <0.001 | |

| English and other language | 18/61 (30) | ||

| Years practising in Australia (n = 160) | |||

| ≤10 | 25/66 (38) | 0.056 | |

| >10 | 50/94 (53) | ||

| Geographic location of work setting (n = 160) | |||

| Regional/rural/remote | 22/63 (35) | 0.015 | |

| Metropolitan | 53/97 (55) | ||

| Hours worked per week (n = 159) | |||

| Part time (≤32 h) | 47/69 (68) | <0.001 | |

| Full time (>32 h) | 28/90 (31) | ||

| Frequency of consultation with refugee women and women seeking asylum (n = 168) | |||

| Not often (≤ every 2 months) | 16/70 (23) | <0.001 | |

| Often (> every 2 months) | 64/98 (65) | ||

| Offer fee-for-service billing arrangements (n = 125) | |||

| Patient co-payment | 4/24 (17) | 0.028 | |

| No patient co-payment | 41/101 (41) | ||

| Offer female interpreter (n = 163) | |||

| No | 19/47 (40) | 0.267 | |

| Yes | 58/116 (50) | ||

| Offer a female provider (n = 165) | |||

| No | 8/33 (24) | 0.003 | |

| Yes | 70/132 (53) | ||

| Request further cultural awareness training in relation to refugee women and women seeking asylum? (n = 151) | |||

| No | 17/22 (73) | <0.001 | |

| Yes | 50/129 (39) | ||

Factors associated with discussion about SRH opportunistically when refugee women and women seeking asylum presented for other health concerns were: not charging a patient a co-payment for consultations, being a female provider, being an RN, having practised for <10 years and working part-time (Table 7).

| Variables | Opportunistic SRH discussion | P-values | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | |||

| Gender (n = 161) | |||

| Male | 5/30 (17) | 0.003 | |

| Female | 60/131 (46) | ||

| Professional group (n = 158) | |||

| RNs | 46/91 (51) | 0.003 | |

| GPs | 18/67 (27) | ||

| Years practising in Australia (n = 160) | |||

| ≤10 | 35/66 (53) | 0.007 | |

| >10 | 30/94 (32) | ||

| Hours worked per week (n = 159) | |||

| Part time (≤32 h) | 38/69 (55) | 0.001 | |

| Full time (>32 h) | 27/90 (30) | ||

| Frequency of consultation with refugee women and women seeking asylum (n = 167) | |||

| Not often (≤ every 2 months) | 22/70 (31) | 0.050 | |

| Often (> every 2 months) | 45/97 (97) | ||

| Offer fee-for-service billing arrangements (n = 124) | |||

| Patient co-payment | 4/24 (17) | 0.039 | |

| No patient co-payment | 39/100 (39) | ||

| Offer female provider (n = 165) | |||

| No | 10/33 (30) | 0.204 | |

| Yes | 56/132 (42) | ||

Hierarchical logistic regression analysis for factors associated with initiating conversations about SRH

The first hierarchical logistical regression analysis is presented in Table 3. Providers not speaking a language other than English was significant in model one, Beta coefficient (Odds Ratio for each predictor variable) 5.01, (95% CI [2.16, 11.6], P < 0.001) and model two 5.27, (95% CI [2.00, 13.86], P < 0.001). Model one includes demographic variables: professional group, language spoken, country of qualification and geographic location. Working in a metropolitan location was also significant in models one 4.21, (95% CI [1.83, 9.69], P < 0.001) and two 3.23, (95% CI [1.32, 7.84], P < 0.01) and three 2.86, (95% CI [1.51, 7.12], P < 0.05). Model two includes HCP knowledge and beliefs; self-rated SRH knowledge, self-rated culturally competency and understanding of women’s SRH awareness. Providers who were ‘moderately comfortable’ or ‘very comfortable’ providing culturally safe care to women were significant in models two 2.58, (95% CI [1.19, 5.56], P < 0.05) and three 2.59, (95% CI [1.14, 5.88], P < 0.05). Providers who viewed women as being ‘somewhat aware’ or ‘moderately aware’ of preventive SRH were significant in model two 0.55, (95% CI [0.32, 0.94], P < 0.05); however, these effects disappeared when factors related to direct professional experience including greater frequency of providing services to refugee women 7.64, (95% CI [2.41, 24.22] P < 0.001), more years practising as a HCP in Australia 2.20, (95% CI [0.71, 6.87], P < 0.001) and <32 h worked per week 3.63, (95% CI [0.70, 18.61], P < 0.001) were entered into model four. Model four includes variables associated with HCPs’ direct professional experience with refugee women or women seeking asylum; frequency of consultation with refugee women or women seeking asylum, years practising in Australia, hours worked per week and offering a female provider. The variables in each model are outlined in Tables 3 and 4. Together, the following three factors explained 59.5% of the variance in initiating conversations about SRH; providing services to refugee women or women seeking asylum more often than every 2 months, working part time, and having practised in Australia for >10 years. Variance provides an indication of the amount of variation in the outcome variable explained by complete hierarchical logistic regression analysis. These results demonstrate that three significant factors together explained 59.5% of the differences observed between those who did and those who did not initiate conversations about SRH. These factors, therefore, play a substantial role in shaping the behaviour of initiating SRH conversations within the context of refugee and asylum seeking healthcare provision.

Hierarchical logistic regression analysis for factors associated with discussing SRH opportunistically when women present for other health concerns

The second hierarchical logistical regression analysis is presented in Table 4. In all four models, significant differences between RNs and GPs were found when discussing SRH opportunistically. Being an RN was significant in models one 3.19, (95% CI [1.52, 6.70], P < 0.01), two 2.91, (95% CI [1.37, 6.22], P < 0.01) and three 2.93, (95% CI [1.37, 6.27], P < 0.01). This effect was maintained but was reduced 2.61, (95% CI [1.12, 6.08], P < 0.01) when variables related to direct professional experience were entered into model four. Factors related to direct professional experience, which were significant in model four, included greater frequency of providing services to refugee women or women seeking asylum 2.82, (95% CI [1.07, 7.40] P < 0.05), more years practising as a HCP in Australia 0.40, (95% CI [1.66, 0.95], P < 0.05) and <32 h worked per week 2.43, (95% CI [1.02, 5.76], P < 0.05). The variables in each model are outlined in Table 4. Together, the following four factors explained 28.5% of the variance in discussing SRH opportunistically; being a RN, providing services to refugee women or women seeking asylum more often than every 2 months and working part time and having practised in Australia for <10 years. These factors, therefore, play a substantial role in shaping the behaviour of opportunistic SRH discussions.

Discussion

This is the first study to explore the preventive SRH practices of HCPs who provide care for refugee women or women seeking asylum in Australia. Findings indicate direct professional experience including greater frequency of providing services to refugee women or women seeking asylum, more years practising as a HCP in Australia, less hours worked per week and offering a female provider positively influence HCPs’ knowledge and beliefs regarding women’s SRH. Perceived barriers to preventive SRH care included women’s cultural and religious beliefs, limited SRH knowledge and English-language skills among women, the presence of a husband/intimate partner, and time constraints during appointments.

Less than one-third of respondents reported initiating SRH conversations or discussing preventive SRH opportunistically. This finding aligns with previous studies on HCPs’ perspectives on refugee and migrant women’s engagement with SRH care in Australia and the USA (Mengesha et al. 2017; Vu et al. 2022). Mengesha et al. (2017) described how HCPs reported a lack of funding and human resources to offer comprehensive SRH services in Australia. Culturally and linguistically concordant patient navigators were successful in helping refugee women navigate the healthcare system and addressing language barriers (Vu et al. 2022). Our study’s results are also corroborated by Mengesha et al. (2017) who found that the perception of gender roles was integral to SRH decision-making, with the need to involve male partners having an impact on the provision of care for women. General practitioners’ engagement in sexual health with migrant and refugee young people has been impacted by negative experiences with GPs for sexual health matters, including not being listened to or being rushed through the appointment (Botfield et al. 2018).

The key finding that HCPs perceived women’s cultural and religious beliefs as a barrier to preventive SRH care is novel in the context of Australia, though it has been supported in research conducted elsewhere. Findings from a systematic review by Soin et al. (2022) indicated that HCPs perceived that certain beliefs held by women dictate specific practices or restrictions related to preventive SRH. For example, religious and cultural acceptability of natural family planning in Nigeria played a role in health workers recommending methods of family planning to women who did not want to use forms of contraception (Ujuju et al. 2011).

Providers who interacted more frequently with refugee women or women seeking asylum were more likely to initiate SRH conversations and discuss SRH opportunistically. This finding may reflect that regular interactions help HCPs develop a level of familiarity and comfort in discussing sensitive topics such as SRH care with refugee women or women seeking asylum. Additionally, increased familiarity and comfort with discussing SRH topics such as contraception, abortion, screening and treatment of sexually transmitted infections, antenatal care, delivery and postnatal care enable HCPs to engage in more comprehensive discussions about SRH with women from refugee-like backgrounds (Mengesha et al. 2018a). Most respondents reported a relatively high level of self-rated comfort with providing culturally safe care. This may, in part, be the result of frequent consultations with refugee women or women seeking asylum (Lau and Rodgers 2021) or HCPs practising in specialist refugee health settings that primarily cater to refugees’ health needs (Patel et al. 2022).

Registered nurses were more likely to discuss SRH opportunistically compared to GPs. This may, in part, be explained by RNs’ key role in SRH promotion and education. Primary care nurses proactively initiate discussions related to health education and disease prevention as part of their role in patient education (Keleher and Parker 2013). Moreover, RNs in our sample included a proportion of SRH nurses and refugee health nurses with further specialist training and expertise in preventive SRH. Previous studies have shown that increased HCPs expertise in SRH leads to more awareness of women’s preventive SRH needs (Mengesha et al. 2018a).

Another important finding was that HCPs practising for >10 years were more likely to initiate SRH conversations but less likely to discuss SRH opportunistically than those with shorter professional experience. One possible reason may be more experienced HCPs have developed established routines or patterns of care and may place less emphasis on discussing preventive SRH opportunistically. Malta et al. (2018) observed that although the majority of GPs acknowledged the importance of discussing sexual health with patients, they did not consistently incorporate such discussions into their routine practice. The authors found in practice that almost all GPs left discussing sexual health primarily to the patient, as most preferred a patient-directed consultation (Malta et al. 2018). Almost all GPs in the study had been practising for >10 years. Conversely, HCPs practising for <10 years were more likely to discuss SRH opportunistically than their more experienced counterparts. One potential explanation may be that in recent years, qualified HCPs have received training emphasising the importance of addressing preventive SRH care routinely and opportunistically (Bateson et al. 2019). Furthermore, culturally safe training has recently become part of HCPs’ curricula in Australia (The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners 2022).

Strengthens and limitations

The study’s strength lies in the broad survey distribution across diverse organisations, professional groups, facilitating potential participation across primary HCPs and it was short and convenient. However, some limitations are acknowledged. As this was an opt-in, anonymous online survey, a response rate could not be calculated. Also, there is no way of knowing how many HCPs see refugee women or women seeking asylum in their practice or what their characteristics are. It is therefore not possible to ascertain the representativeness of those who completed the survey. Furthermore, level of SRH knowledge and provision of culturally safe care were self-reported and may therefore be affected by social desirability bias. Nevertheless, previous studies have established strong concordance between HCPs’ self-reported knowledge and objectively assessed knowledge levels, hence this concern may be mitigated (Snibsoer et al. 2018).

The inclusion only of GPs and RNs in this study might limit the generalisability of the findings to other primary HCPs, such as midwives and other allied health professionals. Because the study focuses solely on GPs and RNs, it may not capture the unique perspectives, practices and challenges faced by other HCPs in the context of primary health care. The number of missing responses was another limitation of the survey. This has the potential for non-response bias and reduced generalisability of findings. Potential for bias may be mitigated given that cases with >60% of missing values were excluded from the analysis. Additionally, dichotomising variables can lead to loss of information and may not fully capture the nuances of the original variable categories (Altman and Royston 2006).

Implications for training, policy and research

The findings in this study have implications for training, policy and research. Training and education for all HCPs about how to provide culturally safe care might improve their capacity to engage positively with people who are refugees or seeking asylum (Migrant and Refugee Women’s Health Partnership 2017). The findings suggest that HCPs who expressed a desire for additional training in preventive SRH for refugee women and women seeking asylum are already comfortable with their current level of knowledge and confidence. Therefore, the training needs that could be better met by these findings include: (1) tailoring training content to focus on advanced or specialised topics within preventive SRH for refugee women and women seeking asylum, building upon the existing foundation of knowledge and confidence among HCPs; (2) designing training programs that emphasise practical skills development and application, allowing HCPs to enhance their competency in delivering culturally sensitive and effective preventive SRH services to refugee women and women seeking asylum; and (3) incorporating opportunities for ongoing professional development and support, such as mentorship programs or access to updated resources and guidelines, to sustain and reinforce the knowledge and skills gained through training. This has clear implications for both pre-service curricula and professional development training. This aligns with recent proposals to integrate refugee health into primary care by expanding specialist services into general primary care practices (Patel et al. 2022), particularly in practices where HCPs provide services to refugee women and women seeking asylum less frequently.

At the policy level, efforts might focus on recognising and addressing cultural barriers hindering discussions on preventive SRH identified in this study. For example, advocating for the full scope of practice for specialised SRH and refugee health nurses might be one approach to address the short consultation times respondents identified as a barrier to initiating preventive SRH conversations. In Australia’s Medicare system, HCPs are required to obtain a provider number to bill Medicare for their services. Currently, in Australia, only NPs and GPs can obtain a Medicare provider number and bill Medicare directly for services they provide.

If specialised SRH and refugee health nurses were granted an expanded scope of practice, including the ability to bill Medicare for their services, this could enable the scheduling of longer appointments when required, hence facilitating increased access to more comprehensive SRH care, interpreter services and information provision for refugee women and women seeking asylum. It might also assist in recognising the role that primary care nurses play in delivering SRH care to these groups of women. Incentivising nurses’ involvement in preventive SRH care through the addition of Medicare provider numbers for RNs and introducing a Medicare item that reflects the time involved for GPs to provide SRH care may make HCPs more likely to initiate SRH conversations and discuss SRH opportunistically. Historically, for example, RNs had access to a Medicare item number to undertake cervical screening, but since 2006, this specific item number is no longer available. In the absence of this, policymakers may consider revising the current Medicare Practice Stream funding (Australian Government 2023c). This funding, which provides financial incentives to cover the costs of engaging RNs and other practitioners, could be increased to support RNs in conducting preventive SRH screening. This adjustment would enable GPs to focus on more complex cases. Additionally, the finding that more frequent professional engagement with refugee women and women seeking asylum leads to improved initiation of SRH conversations suggests a need for continuity of care between HCPs and refugees with dependable services that go beyond one-time interventions.

Future research might examine reasons why two-thirds of HCPs were not routinely initiating preventive SRH conversations or discussing SRH opportunistically, as only about one-third of opportunistic SRH discussions were explained by variables in our analysis. This might involve exploring how the different organisational contexts such as community health, SRH and refugee health influence practice in relation to initiating and discussing preventive SRH care. Future research might explore HCPs’ perspectives and attitudes and organisational factors that might promote or hinder discussions to improve understanding of why preventive SRH is not always routinely addressed in primary care. This would help inform interventions and strategies to promote preventive SRH for refugee women and women seeking asylum in primary health care.

New knowledge to emerge from this study suggests that HCPs with more direct professional experience and frequent interactions with refugee women demonstrate higher knowledge and better attitudes toward preventive SRH; significant barriers to care include cultural and religious beliefs, limited English proficiency, and time constraints; fewer than one-third of HCPs routinely initiate SRH discussions; and RNs may be more proactive than GPs in discussing SRH opportunistically. These findings underscore the need for targeted training and support to improve HCPs’ comfort and competence in delivering culturally sensitive SRH care, highlighting the importance of addressing systemic barriers to enhance preventive SRH services for refugee populations.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study addressed a knowledge gap by exploring HCPs’ perspectives on preventive SRH for refugee women and women seeking asylum. Overall, the study suggests HCPs are aware of the preventive SRH care needs of these women, but have limited capacity to address them. Health policy reform and HCP training are needed to improve HCPs’ ability to incorporate preventive SRH in a culturally safe way in consultations with refugee women and women seeking asylum. Engaging HCPs in an ongoing process of building cultural safety is central to improving access to preventive SRH care. This is important, as missed opportunities to discuss preventive SRH may have serious implications for the health and wellbeing of refugee women or women seeking asylum.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author contributions

Conception and design of the study was undertaken by ND, KH and JF. The first draft of the manuscript and data analysis involved ND, with KH and JF bringing a wider perspecive to the analysis. Critical review and editing was conducted by KH and JF. All authors contributed to the development of the manuscript and approved the final version.

Acknowledgements

We thank all of the organisations who facilitated the distribution of the survey and respondents who took the time to complete the survey. We also thank Tim Powers, School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine’s statistical adviser for his guidance and helpful discussions about approaches to data analysis and interpretation of results. JF is supported by the Finkel Professorial Fellowship, which receives funding from the Finkel Family Foundation. ND holds an Australian Government Research Training Scholarship. The AUD$50 gift card was internally funded.

References

Altman DG, Royston P (2006) The cost of dichotomising continuous variables. BMJ 332(7549), 1080.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Australian Government (2023b) Primary health networks. Australian Government. Available at https://www.health.gov.au/our-work/phn [Accessed 14 September]

Australian Government (2023c) Workforce incentive program – practice stream. Department of Heath and Aged Care. Available at https://www.health.gov.au/our-work/workforce-incentive-program/practice-stream [Accessed 20 May]

Australian Government (2024) Summary statistics, medical profession. Australian Government. Available at https://hwd.health.gov.au/resources/data/summary-mdcl.html [Accessed 26 July]

Bateson DJ, Black KI, Sawleshwarkar S (2019) The Guttmacher–Lancet Commission on sexual and reproductive health and rights: how does Australia measure up? Medical Journal of Australia 210(6), 250-252.e1.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Botfield JR, Newman NE, Kang M, Zwi AB (2018) Talking to migrant and refugee young people about sexual health in general practice. Australian Journal of General Practice 47(8), 564-569.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Brandenberger J, Tylleskar T, Sontag K, Peterhans B, Ritz N (2019) A systematic literature review of reported challenges in health care delivery to migrants and refugees in high-income countries – the 3C model. BMC Public Health 19(1), 755.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Cheng I-H, Drillich A, Schattner P (2015) Refugee experiences of general practice in countries of resettlement: a literature review. British Journal of General Practice 65(632), e171-e176.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Curtis E, Jones R, Tipene-Leach D, Walker C, Loring B, Paine S-J, Reid P (2019) Why cultural safety rather than cultural competency is required to achieve health equity: a literature review and recommended definition. International Journal for Equity in Health 18(1), 174.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Davidson N, Hammarberg K, Romero L, Fisher J (2022) Access to preventive sexual and reproductive health care for women from refugee-like backgrounds: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 22(1), 403.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Davidson N, Hammarberg K, Fisher J (2024) ‘If I’m not sick, I’m not going to see the doctor’: Access to preventive sexual and reproductive health care for Karen women from refugee backgrounds living in Melbourne, Australia – a qualitative study. Health Promotion Journal of Australia 2024, 1-13.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Di Stefano G, Cataldo E, Laghetti C (2019) The client-oriented model of cultural competence in healthcare organizations. International Journal of Healthcare Management 12(3), 189-196.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hall WJ, Chapman MV, Lee KM, Merino YM, Thomas TW, Payne BK, Eng E, Day SH, Coyne-Beasley T (2015) Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: a systematic review. American Journal of Public Health 105(12), e60-e76.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Kasper A, Mohwinkel L-M, Nowak AC, Kolip P (2022) Maternal health care for refugee women – a qualitative review. Midwifery 104, 103157.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Keleher H, Parker R (2013) Health promotion by primary care nurses in Australian general practice. Collegian 20(4), 215-221.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Lau LS, Rodgers G (2021) Cultural competence in refugee service settings: a scoping review. Health Equity 5(1), 124-134.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Lindenmeyer A, Redwood S, Griffith L, Teladia Z, Phillimore J (2016) Experiences of primary care professionals providing healthcare to recently arrived migrants: a qualitative study. BMJ Open 6(9), e012561.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Little RJA (1988) A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. Journal of the American Statistical Association 83(404), 1198-1202.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Malta S, Hocking J, Lyne J, McGavin D, Hunter J, Bickerstaffe A, Temple-Smith M (2018) Do you talk to your older patients about sexual health? Health practitioners’ knowledge of, and attitudes towards, management of sexual health among older Australians. Australian Journal of General Practice 47(11), 807-811.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Mengesha Z, Perz J, Dune T, Ussher J (2017) Refugee and migrant women’s engagement with sexual and reproductive health care in Australia: a socio-ecological analysis of health care professional perspectives. PLoS ONE 12(7), e0181421.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Mengesha ZB, Perz J, Dune T, Ussher J (2018a) Preparedness of health care professionals for delivering sexual and reproductive health care to refugee and migrant women: a mixed methods study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15(1), 174.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Mengesha ZB, Perz J, Dune T, Ussher J (2018b) Talking about sexual and reproductive health through interpreters: the experiences of health care professionals consulting refugee and migrant women. Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare 16, 199-205.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Patel P, Muscat DM, Bernays S, Zachariah D, Trevena EL (2022) Approaches to delivering appropriate care to engage and meet the complex needs of refugee and asylum seekers in Australian primary healthcare: a qualitative study. Health & Social Care in the Community 30(6), e6276-e6285.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Phillips J (2015) ‘Asylum seekers and refugees: what are the facts?’ (Department of Parliamentary Services: Canberra) Available at https://www.aph.gov.au/about_parliament/parliamentary_departments/parliamentary_library/pubs/rp/rp1415/asylumfacts.

Riggs E, Davis E, Gibbs L, Block K, Szwarc J, Casey S, Duell-Piening P, Waters E (2012) Accessing maternal and child health services in Melbourne, Australia: reflections from refugee families and service providers. BMC Health Services Research 12, 117.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Robertshaw L, Dhesi S, Jones LL (2017) Challenges and facilitators for health professionals providing primary healthcare for refugees and asylum seekers in high-income countries: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative research. BMJ Open 7(8), e015981.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Scully EA, Biddlecom A, Darroch JE, Riley T, Ashford LS, Lince-Dreroche N, Firestein L, Murro R (2020) Adding it up: investing in sexual and reproductive health report –2019 Methodology Report. Guttmacher Institute, New York, USA. Available at www.guttmacher.org/report/adding-it-up-investing-in-sexual-reproductive-health-2019

Snibsoer AK, Ciliska D, Yost J, Graverholt B, Nortvedt MW, Riise T, Espehaug B (2018) Self-reported and objectively assessed knowledge of evidence-based practice terminology among healthcare students: a cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 13(7), e0200313.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Soin KS, Yeh PT, Gaffield ME, Ge C, Kennedy CE (2022) Health workers’ values and preferences regarding contraceptive methods globally: a systematic review. Contraception (Stoneham) 111, 61-70.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Stryhn H, Christensen J (2014) The analysis--hierarchical models: past, present and future. Preventive Veterinary Medicine 113(3), 304-312.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (2022) 2022 RACGP curriculum and syllabus for Australian general practice. RACGP, Melbourne. Available at https://www.racgp.org.au/education/professional-development/cpd/continuing-professional-development-cpd-program/2022-racgp-curriculum-and-syllabus-for-general-pra#:~:text=There%20are%20seven%20core%20units,a%20useful%20resource%20for%20providers

Timlin M, Russo A, McBride J (2020) Building capacity in primary health care to respond to the needs of asylum seekers and refugees in Melbourne, Australia: the ‘GP Engagement’. Australian Journal of Primary Health 26, 10-16.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ujuju C, Anyanti J, Adebayo SB, Muhammad F, Oluigbo O, Gofwan A (2011) Religion, culture and male involvement in the use of the Standard Days Method: evidence from Enugu and Katsina states of Nigeria. International Nursing Review 58(4), 484-490.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

UNHCR (1951) Convention and protocol relating to the status of refugees. (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees: Geneva, Switzerland) Available at https://www.unhcr.org/en-au/protection/basic/3b66c2aa10/convention-protocol-relating-status-refugees.html

UNHCR (2022) Global trends forced displacement 2022. (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees: Geneva, Switzerland) Available at https://www.unhcr.org/global-trends-report-2022

Vu M, Besera G, Ta D, Escoffery C, Kandula NR, Srivanjarean Y, Burks AJ, Dimacali D, Rizal P, Alay P, Htun C, Hall KS (2022) System-level factors influencing refugee women’s access and utilization of sexual and reproductive health services: a qualitative study of providers’ perspectives. Frontiers in Global Women’s Health 3, 1048700.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |