A survey of stockperson attitudes and youngstock management practices on Australian dairy farms

Laura Field A * , Megan Verdon

A * , Megan Verdon  B , Ellen Jongman

B , Ellen Jongman  A and Lauren Hemsworth

A and Lauren Hemsworth  A

A

A

B

Abstract

The attitudes of stockpeople towards their animals directly affects the human–animal relationship, in turn affecting stockperson behaviour and animal welfare and productivity. Little is known about the attitudes of Australian stockpeople towards dairy youngstock under their care.

We aimed to explore Australian stockperson attitudes and management practices associated with calf management and reported replacement heifer outcomes.

A convenience sample surveying 91 Australian dairy stockpeople was used to explore common calf-rearing practices, as well as attitudes of stockpeople towards youngstock and current issues in youngstock welfare and management on Australian dairy farms.

Management of both replacement and non-replacement calves varied considerably by farm, and reported practices did not correlate with herd management or demographic data. Factor analysis identified nine principal components related to attitudes towards primiparous heifer and calf welfare and management practices. Variables calculated from these components rarely correlated with demographic factors; however, female respondents were more likely to have positive attitudes towards current issues in calf management (P = 0.013). Several correlations were found between the component variables. Participants who believed it was difficult to use higher-welfare practices to manage the herd were less likely to believe their trusted advisors valued these practices (P < 0.001), or believe these practices were important themselves (P < 0.001). These participants were more likely to believe that early lactation heifers were difficult to handle (P < 0.001), and less likely to believe that it was important to separate cows and calves for calf health (P = 0.006). Respondents who believed that heifers were difficult to handle in early lactation were more likely to believe heifers on their farm were underperforming (P < 0.001).

Factors external to farm demographics appear to shape the attitudes of Australian stockpeople and on-farm dairy youngstock management decisions. Attitudes towards youngstock appear to be linked to on-farm cultures, particularly the perceived difficulty of performing tasks linked to good welfare outcomes, and the perceived value placed on these practices by trusted advisors.

The results indicate that further research using a more representative sample is needed to better understand those responsible for Australian dairy youngstock management and the key drivers behind their management choices, to best tailor approaches to encouraging implementation of best practice on-farm.

Keywords: calf management, calf welfare, convenience sampling, cow-calf separation, dairy calves, stockperson attitudes, surplus calf pathways, youngstock.

Introduction

Limited Australian literature is published about the management and welfare of pre-weaned dairy calves, and even less about the post-weaning management of replacement heifers prior to their entry into the milking herd (Verdon 2023). Less still is known about the attitudes and behaviours of the farmers and stockpeople responsible for the care of these juvenile animals. Health management during the early-life period has been relatively well covered; colostrum management and passive immunity transfer have been investigated in both replacement and non-replacement calves, with peripheral data collected on morbidity and mortality, housing, feeding and other interventions generally for replacement heifers only (e.g. Vogels et al. 2013; Abuelo et al. 2019; Roadknight et al. 2022). The post-weaning period tends to be less thoroughly explored. The systems generally described in the research are more typical of American and European dairy farming, wherein animals are managed in indoor, year-round calving systems and calves are managed individually or in pairs. Conversely, Australian dairy systems tend to be pasture-based, and calves are typically reared indoors in groups and transferred to low-intensity pasture grazing systems until close to primiparturition at about 23 months of age (Verdon 2021, 2023). This post-weaning period during which heifers are managed away from prime grazing land, usually on dryland run-off blocks or on agistment, may mean that for this phase of life, heifers are monitored and observed less often than are their pre-weaned or post-parturient counterparts, who are handled frequently and managed more intensively (Verdon 2023).

Considerable research has shown that the welfare of livestock relies on the attitudes and behaviour of the humans who care for them, monitor them, and make decisions regarding their lifetime management (e.g. Hemsworth and Coleman 2011). Dairy cattle interact particularly closely and frequently with humans from birth, through artificial rearing, artificial insemination, regular milking and other husbandry procedures, and these interactions increase significantly after the heifer’s first calving (Sutherland and Huddart 2012). The attitudes of stockpeople working closely with cattle influence the way that they handle animals, both during their early life and throughout their productive years. The sequential nature of the relationship among dairy stockpersons’ attitude towards their animals, their subsequent behaviour, and the effects of this behaviour on animal welfare, handling ease, and productivity, and stockperson job satisfaction, has been well documented (e.g., Breuer et al. 2000; Seabrook and Wilkinson 2000; Hemsworth et al. 2002; and reviewed by Waiblinger et al. 2006 and Napolitano et al. 2020). Farmers have previously self-identified their perceived ethical obligations, pride and responsibility of care as personal motivators to maintain high standards of on-farm animal welfare (for instance, Croyle et al. 2019). Such positive attitudes towards cattle and their care positively influence stockperson behaviour and the human–animal relationship (Napolitano et al. 2020).

Given the close relationship between humans and animals on dairy farms, it is important to consider the effects of stockperson attitudes on both calf management choices and the heifer’s experience transitioning into the milking herd. Both positive stockperson attitudes, and associated handling and choices made about the management of juvenile replacement heifers, could play a part in the long-term development and adaptability of these animals (e.g. Hemsworth et al. 2000; Rousing et al. 2004; Bertenshaw et al. 2008). Indeed, the attitudes of on-farm decision makers towards cattle may dictate management practices directly affecting the individual animal, and thus on-farm culture and expectations. These, in turn, influence the ability of individual stockpeople to control welfare-related components of animal care. One framework for exploring the attitudes and factors which may inform stockperson behavioural intentions is the human–animal relationship (HAR) model, which has been developed to explore stockperson attitudes and behaviour specifically by Hemsworth and Coleman (2011), with reference to Ajzen’s theory of planned behaviour (Ajzen 1991). The HAR model forms the theoretical framework upon which this study has been developed, and contends that stockperson behavioural intentions are shaped by their own personal beliefs or attitudes, normative beliefs held by influential people around them and their perceived sense of control over performing that behaviour (Hemsworth and Coleman 2011). Stockperson-reported measures, such as normative and control factors, may describe the culture of human–animal relationships fostered in their specific workplace and should therefore also be considered important factors in determining the likelihood of certain welfare outcomes for dairy heifers.

Some dairy calf management practices which affect calf welfare do not align with public expectations and so pose a risk to the social licence of the industry (e.g. Bolton and von Keyserlingk 2021). Surveys of the general public indicate, for instance, that practices such as cow–calf separation or the early life slaughter of non-replacement calves are incongruous with public values and expectations, with these complex issues characterised as ‘wicked problems’ (e.g. Ventura et al. 2013, 2016; Cardoso et al. 2017; Bolton and von Keyserlingk 2021; Ritter et al. 2022). For the latter, a non-replacement dairy calf includes any calf produced in excess of those required to replace cows leaving the milking herd, including those sold to live export. In Australia, these animals are typically transported to slaughter as bobby calves, i.e. a calf <30 days of age not accompanied by its mother, a process with potential negative implications for both the juvenile animal’s welfare and the industry’s social licence (Roadknight et al. 2021). Alternatives to the slaughter of non-replacement dairy calves include the euthanasia of healthy calves at birth, an additional social licence issue that puts producers under significant moral stress, or developing opportunities for the non-replacement animal to be reared for the red meat market as dairy beef (Vicic et al. 2022). This is an ongoing development within the industry which requires evolution of established industry and market practices. The complexity of these issues means that finding workable solutions requires the assessment and consideration of all stakeholder perspectives. Farmer attitudes are one element in a range of wider complex issues, but they are integral to enacting change in areas of social concern. Understanding producer attitudes will allow the industry to ensure that as management evolves, practices align with both public and farmer values.

This study aimed to investigate how calves, particularly replacement heifers, are reared across Australia’s dairy operations, to identify Australian stockperson attitudes towards dairy herd welfare, calves and current issues in calf management, and to explore correlations between demographic data and these attitudes. We hypothesised that there would be correlations between calf management protocol, positive attitudes towards high-welfare herd management, positive attitudes towards current calf-welfare challenges, and positive attitudes towards and outcomes for dairy heifers in early lactation.

Materials and methods

Human ethics approval for this project was obtained from The University of Melbourne’s Human Ethics Advisory Group (1953903.2). Participation in this study was voluntary and no incentives were provided for participation.

Development

The questionnaire used in this study was developed with reference to previous questionnaires produced by Alvåsen et al. (2014), Fukasawa et al. (2017), Kauppinen et al. (2013), Kolstrup (2012), Maller et al. (2005) and Panamá Arias and Spinka (2005). The draft questionnaire was then reviewed by one veterinarian, two animal behaviour scientists and three dairy farmers external to the research team from Australia and New Zealand, and amended where necessary following their consultation.

The questionnaire was anonymous and comprised 38 questions across eight sections (Supplementary Table S1). These blocks followed the following themes: participant and farm demographics, calf management, cow behaviour, heifer behaviour, attitudes towards seven aspects of dairy farming asked according to the TPB (Ajzen 1991), attitudes towards calves and calf-rearing, and a final section on the participant’s experience as a dairy stockperson in their workplace, including their relationships with the cattle under their care.

Distribution

The final version of the questionnaire was delivered via the Qualtrics survey platform (Qualtrics, Provo, UT, USA) and could be accessed via direct link. Where possible, the order of potential answers presented to participants was randomised. The questionnaire was distributed through a link to an online survey between June 2020 and November 2020, and survey distribution was targeted towards dairy stockpeople, particularly those with an interest in heifer management. The online link was available for respondents and industry members to share, and snowball recruitment occurred in this manner. The survey link was also published across social media accounts of industry bodies, including the Animal Welfare Science Centre, DairyTas, the Tasmanian Institute of Agriculture and the New South Wales Department of Primary Industries, as well as in the Tasmanian Institute of Agriculture’s monthly newsletter.

No quotas for demographic requirements were set during the survey. The survey received a convenience sample of 98 responses, after screening for completeness (a minimum of 90% of questions answered), seven of these responses were discarded, leaving 91 responses containing the required data.

All data analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, ver. 29 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive data were first generated and used to screen variables prior to detailed analysis. Demographic data are reported according to this initial descriptive output; farm and respondent demographic data are presented in Supplementary Table S2, while descriptive cow and calf management data are presented in Supplementary Table S3.

Principal-component analysis (PCA) followed by a direct Oblimin rotation was conducted on participant responses to questions describing their attitudes to animal management and working with cattle, as well as their experiences managing and handling first-lactation heifers. Further, questions exploring participant attitudes to specific animal management practices were asked in three different ways to ascertain each participant’s behavioural beliefs (or individual attitudes), normative beliefs and control beliefs, according to the HAR model (Hemsworth and Coleman 2011). These three ways of presenting question accounted for the following three drivers of stockperson behaviour identified in the HAR model: (1) control beliefs, pertaining to the individual’s perception of the difficulty of a task or behaviour, (2) behavioural beliefs, pertaining to the individual’s own beliefs about the importance or outcome of a specific task or behaviour and, (3) normative beliefs, pertaining to an individual’s beliefs about how their ‘trusted advisors,’ or people whose opinions are important to the individual, may feel about a specific task or behaviour. The selected practices about which these questions were asked have been linked to increased empathy towards dairy animals and indicators of improved on-farm welfare in previous studies (e.g. Kielland et al. 2010; Wikman et al. 2013; Palczynski et al. 2022).

Suitability of data for PCA was determined using criteria described by Pallant (2013), wherein the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy exceeded 0.6 and Bartlett’s tests of sphericity reached statistical significance (P < 0.05). A variable was included on a component only if its loading exceeded 0.33. If a variable loaded on multiple components, with the largest loading exceeding 0.6 and the additional loadings being <0.4, then that variable was included only in its largest loading component. Composite scores for each component were then computed by averaging the scores of items established as belonging to each underlying common component. Scale reliabilities were measured using Cronbach’s α coefficients. The criteria for reliability were determined at α > 0.7; however, where face validity of the component was sound and loadings were high (α > 0.5), the component was determined as acceptable for further exploration. Any components that could not meet these criteria (n = 6) were removed from further analysis. Data pertaining to general attitudes about working with cattle and towards calves and calf-rearing were deemed unsuitable for component analysis and were not included. Nine components were identified using this methodology, outlined in Table 1, along with Cronbach’s alpha and loading values for each component. Each component is assigned a label that summarises the single construct encapsulated by the data, to ease interpretation.

| Topic | Assigned component label | %Variance | α A | Questionnaire item | Loading | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Management of and handling of early lactation heifersB | 1. Heifers difficult | 58.9 | 0.738 | Difficulty performing standard management tasks (e.g. hoof care, teat sealing) with first-lactation heifers | 0.846 | |

| Difficulty moving first-lactation heifers in and out of milking shed | 0.831 | |||||

| Difficulty training first-lactation heifers to the milking shed and routine | 0.704 | |||||

| Noticeable difference between ease of handling cows and heifers in the first week of lactation | 0.675 | |||||

| Motivations for cow–calf separationC | 2. Farm management/profit | 28.8 | 0.694 | To prevent losing profit from milk going to calves instead of sale | 0.774 | |

| To get calves used to being around humans | 0.716 | |||||

| To make managing calves easier | 0.708 | |||||

| To increase calf concentrate intake | 0.680 | |||||

| To make managing milking cows easier | 0.458 | |||||

| 3. Calf health | 20.1 | 0.465 | To reduce the risk of calf illness | 0.826 | ||

| To ensure calves receive quality colostrum | 0.777 | |||||

| To reduce the spread of Johne’s disease | 0.541 | |||||

| Attitudes to current issues in calf managementB | 4. Concern for calf welfare | 38.3 | 0.549 | Rearing calves with foster cows would work on a commercial dairy farm. | 0.749 | |

| It is beneficial for calves to have contact with older animals. | 0.742 | |||||

| Rearing dairy beef is a viable management choice for my farm. | 0.628 | |||||

| Sale as bobby calves is an acceptable alternative to rearing non-replacement calves. | −0.464 | |||||

| Euthanasia at birth is an acceptable alternative to rearing non-replacement calves. | −0.440 | |||||

| Normative beliefs: welfare indicatorsB | 5. Normative welfare promotion | 38.7 | 0.625 | Advisor believes it is important for me to receive ongoing training | 0.814 | |

| Advisor believes it is important to maintain herd health and productivity records | 0.712 | |||||

| Advisor believes calf-rearing is an important task | 0.585 | |||||

| Advisor believes it is important to use pain relief at dehorning | 0.567 | |||||

| Behavioural beliefs: welfare indicatorsB | 6. Health promotion | 33.3 | 0.714 | I believe checking the general health of the herd daily is important | 0.850 | |

| I believe the task of calf-rearing is important | 0.815 | |||||

| I believe it is important to maintain herd health and productivity records | 0.664 | |||||

| Control beliefs: welfare indicatorsB | 7. Difficulty of high-welfare practices | 38.5 | 0.722 | Checking the health of cows daily is difficult | 0.746 | |

| Calf-rearing is difficult | 0.732 | |||||

| Receiving ongoing training is difficult | 0.648 | |||||

| Keeping health and productivity records is difficult | 0.593 | |||||

| Patting and speaking to your cows during handling is difficult | 0.541 | |||||

| Completing milking quickly is difficult | 0.534 | |||||

| Using pain relief at dehorning is difficult | 0.500 | |||||

| Heifer life stages for specialised careB | 8. All life stages | 74.2 | 0.959 | Leadup to entering breeding program | 0.918 | |

| During calving | 0.912 | |||||

| On entry to the milking herd | 0.900 | |||||

| At and immediately post-weaning | 0.898 | |||||

| First week of life | 0.896 | |||||

| During milk feeding | 0.893 | |||||

| Growing out (3–12 months) | 0.857 | |||||

| During pregnancy | 0.836 | |||||

| Throughout first lactation | 0.768 | |||||

| During lead feeding | 0.714 | |||||

| Heifer performanceD | 9. Heifers not under-performing | 49.2 | 0.749 | Ability to maintain a pregnancy | 0.832 | |

| Health and ability to fight disease | 0.827 | |||||

| Body condition | 0.689 | |||||

| Ability to get in calf | 0.674 | |||||

| Ability to feed competitively | 0.573 | |||||

| In terms of production | 0.562 |

Correlations were calculated using a Spearman rank correlation; a non-parametric test was used to encompass both normally and non-normally distributed data. Correlations were deemed significant if P < 0.05 and the correlation coefficient was >0.3 but <0.9.

The nine components identified by PCA were explored for correlations with each other, and with selected demographic data, including participant age, gender, years working in dairy and position on their farm of employment, and farm data including region, feeding system and herd size.

Results

Demographics: participants and farms

The survey received responses from 91 participants, including 26 males, 63 females and 2 participants who did not identify as male or female, or preferred not to disclose their gender. Participant age ranged from 18–24 to 65+, with the highest proportion of participants aged 25–34 (33%). Participants had multiple and varied on-farm responsibilities, although 97.8% reported having some responsibility for calf-rearing on their farm. Table 2 compares demographic data from the present study with the most recent industry data (Dairy Australia 2015, 2019, 2022). Raw farm and respondent demographic data are available in Supplementary Table S2.

| (a) Participant herd size A, B | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum herd size for 3+ months | Participants (%) | 2019 national herd data (%) | |

| Less than 150 | 13.2 | 21 | |

| 150–300 | 26.4 | 41 | |

| 301–500 | 30.8 | 24 | |

| 501–750 | 19.8 | 7 | |

| 751+ | 8.8 | 7 | |

| (b) Participant feed system C | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Feed system | Participants (%) | 2015 national herd data (%) | |

| 1 | 33 | 23 | |

| 2 | 45.1 | 64 | |

| 3 | 9.9 | 7 | |

| 4 | 6.6 | 5 | |

| 5 | 4.4 | 1 | |

| (c) Participant dairying region A, D | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Region | Participants (%) | 2019 national herd data (%) | |

| Western Dairy | 5.5 | 2.7 | |

| Dairy SA | 3.3 | 4.4 | |

| Murray Dairy | 22 | 24.2 | |

| WestVicDairy | 19.8 | 22.1 | |

| GippsDairy | 19.8 | 23.6 | |

| Subtropical Dairy | 5.5 | 9.2 | |

| Dairy NSW | 12.1 | 11.0 | |

| DairyTas | 12.1 | 6.2 | |

| (d) Calving system E | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| System | Participants (%) | 2022 national herd data (%) | |

| Seasonal | 36.3 | 37 | |

| Split | 40.7 | 38 | |

| Year-round | 22 | 25 | |

Tables 1a–d compare participant demographics with the demographics of the wider Australian dairy industry as collected through industry-funded surveys.

Participants had worked within the dairy industry from between less than a year (2%) to more than 50 years (1%), with the highest proportion of participants having been involved in the industry for 6–10 years (24%). Time working on the current farm of employment ranged from less than 3 months (2%) to between 41 and 50 years (4%), with the highest proportion of participants having worked on their current farm of employment for 1–5 years (42%). Of all participants, 24% had not completed any industry training.

The greatest percentage of farms (45.1%) operating under Feed System 2, defined as a moderate–high bail system, in which cattle graze pasture and other forages and are fed more than 1 tonne of grain or concentrates in the bail (Dairy Australia 2015). Conversely, cattle had no access to pasture on 4.4% of farms (Table 2b). Most farms milked their cows twice daily (92%), and rotary (37%) or swing-over herringbone (38%) parlours were the most reported. Milking was reported to take from less than an hour (2%) to more than 5 h (1%), although the most predominant milking duration reported was between 2 and 3 h (45.2%). Seventy nine per cent of participants reported that their farm of employment was family-owned and -run.

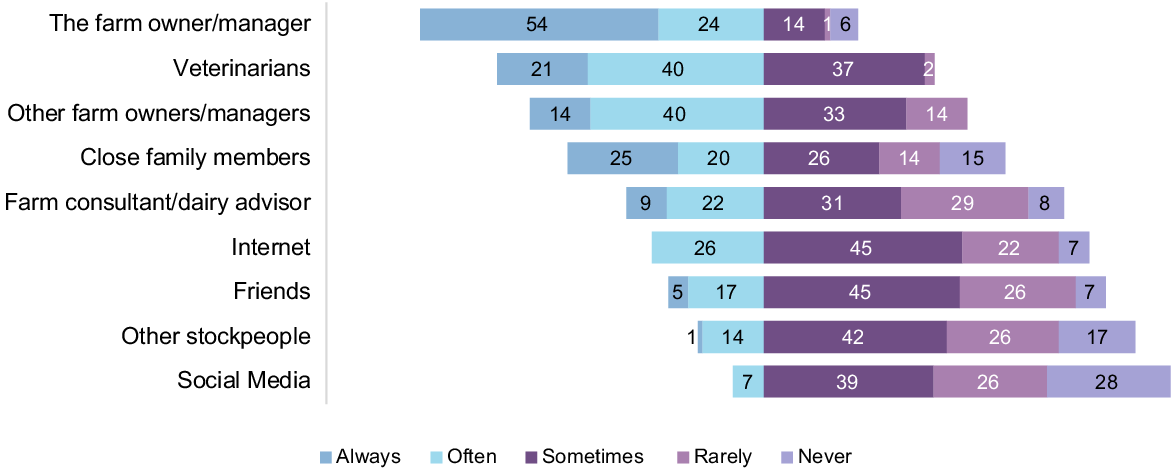

Participants were asked to indicate how likely they would be to ask the advice of ‘advisors’ from a predetermined list. Of these, the owner or manager of the farm was the most trusted advisor, followed by veterinarians, other dairy farmers or managers or the participant’s closest family. Participants were less likely to consult social media, stockpeople on their farm or their friends for advice about their farm (Fig. 1).

Australian calf management

Calving patterns reported in the present study were comparable to those reported in current industry data from the 2022 Dairy Australia Animal Husbandry and Genetics Survey (Dairy Australia 2022); 36% of farms followed a seasonal pattern, whereas 41% followed split calving and 22% calved year-round (Table 2). A dedicated employee primarily employed to rear calves was reported by 78% of participants.

Most farms in the present study housed their replacement heifers indoors in groups (54%), while only 10% of farms housed calves individually. Milk feeding practices varied, with sale milk and waste milk being the most used options for calf feeding. Of all participants, 72% reported feeding some form of fresh whole milk to calves, excluding 14% who reported fortification of whole milk with milk replacer on their farm. The use of some form of waste milk to feed calves was reported by 56% of respondents. Neither type of calf housing nor milk feeding management choices was correlated with herd size or feeding system, calving pattern or milking frequency or duration.

Management of Australian replacement heifers

Participants were asked to consider the importance of providing replacement heifers with specialised management at particular life stages, from birth until their first lactation (Supplementary Fig. S1). Participants predominantly ranked all listed stages as somewhat to very important; however, the first week of life and during calving were reported as the most important times for heifers to receive specialised care and focused management. Less than 5% of participants considered that providing specialised management at any particular life stage was unimportant. Of all life stages, lead feed (a practice undertaken during the transition period, which is the period immediately prior to and following calving, during which a cow’s diet is changed to prepare her body for parturition and lactation) and throughout the first lactation were considered as needing the least specialised management (Proudfoot and Huzzey 2022). When identifying areas in which heifers were underperforming on farm, maintaining body condition and feeding successfully and competitively in mixed-age herds attracted the most concern, by 24% and 21% of participants respectively (Supplementary Fig. S2). Health and maintaining pregnancy were the areas of least concern, with only 5% of participants identifying these as areas in which their heifers were underperforming. PCA was able to group these variables into Components 8 and 9.

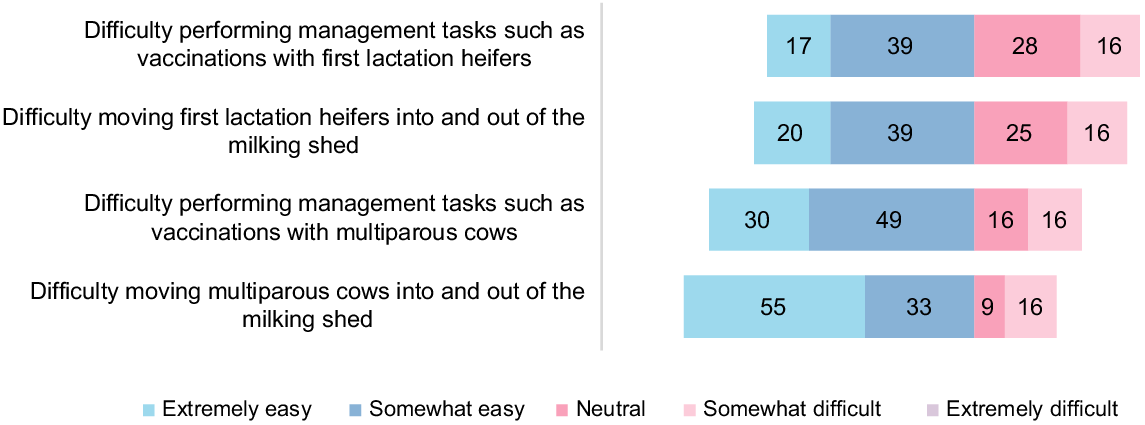

Twelve per cent of respondents reported greater difficulty performing standard management tasks (such as drenching or vaccinations) with first-lactation heifers than with multiparous cows (Fig. 2). Similarly, 16% of participants reported a greater difficulty moving heifers into and out of the milking shed than moving multiparous cows. A moderate to great difference in difficulty milking fresh heifers compared with fresh multiparous cows in the first week after calving was reported by 35% of respondents when asked to rate these differences. Nevertheless, only 17% of respondents reported moderate to great difficulty training heifers to the milking parlour and routine. PCA was able to group these variables into Component 1.

Reported difficulty of managing and handling heifers and multiparous cows on respondent farms (% of respondents).

Most heifers were reported to first mix and be managed with older cows during lead feeding (37.4%), although 27.5% of participants reported that heifers on their farm mixed with older cows prior to this point and 22% of heifers first mixed with older cows when they entered the milking herd after their first calving (Supplementary Table S3). Only 23% of participants reported splitting their herd; of these, 33.3% (n = 7) stated that this was to house heifers separately from older milkers, 14% (n = 3) did so to allow more time to milk their heifers and 62% (n = 13) did so to manage the feed intake and nutritional needs of different groups (Supplementary Table S3).

Current issues in calf management

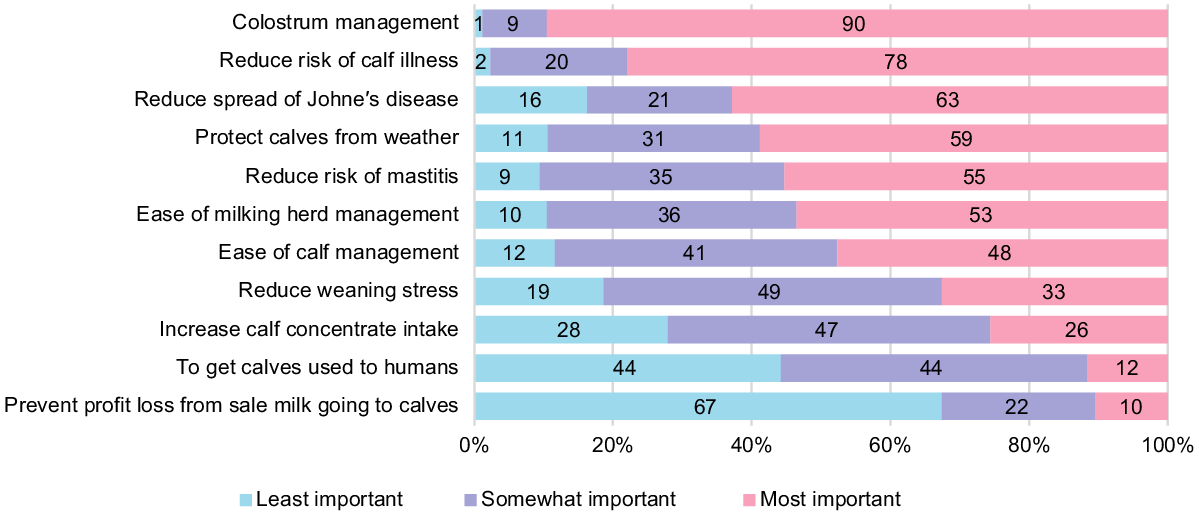

The most commonly reported motivations for separating cows and calves after calving were colostrum management, reducing calf illness and reducing the spread of Johne’s disease, whereas the loss of profit from sale milk being suckled by calves and the desire to socialise calves with humans were the least commonly reported motivations (Fig. 3). PCA was able to group these variables into Components 2 and 3.

Reported outcomes for non-replacement calves born on participant farms were varied. Sixty-five per cent of participants reported that non-replacement calves born on their farm may be sold as bobby calves, while 29% reported rearing some calves as dairy beef and 7.5% reported euthanising some non-replacement calves at birth. No distinction was made regarding whether calves euthanised at birth were healthy or not.

In addition to providing categorical responses on non-replacement calf management, respondents were given an option to provide a text response elaborating on their management practices, and were particularly encouraged to do so if they managed non-replacement calves according to more than one practice. Of the 91 respondents, 21 (23%) chose to provide further detail in this text box; text responses were loosely categorised and are presented in Supplementary Table S4. Several respondents identified choosing management practices for individual non-replacement calves dependent on factors such as milk price, health and size of the non-replacement calf and the beef market during the calving season; seven respondents reported calf-based factors and three respondents reported market-based factors. For instance, euthanasia or sale as bobby calves was identified by eight participants as an end point for calves only when the market was poor, when they were unlikely to thrive, or when they were born at the tail end of the calving period and would therefore involve more work and an extended calf-rearing season. Six respondents reported that the bobby truck was one of several pathways for non-replacement calves.

Thirteen respondents sold calves on, eight when calves were young, four when calves were older, and one reporting both of these options. Only one respondent reported rearing calves as beef for their own consumption. Five respondents used beef genetics in their dairy herd to breed non-replacement beef-cross calves. Six participants reported that their farm actively sought private buyers to rehome or rear bull calves where possible, while one participant reported bull calves being reared as stud bulls and another sold non-replacement heifers on as replacements for other farms. These respondents worked with herds ranging from fewer than 150 animals to herds of 501–750 animals.

The only correlation between calf and farm management practices was between the herd’s calving pattern and feeding system, wherein herds that calved more than once per year (i.e. in split or year-round calving systems) were more likely to feed their milking herd higher proportions of concentrate as part of their diet (ρ = 0.431, P < 0.001, Supplementary Table S5).

Stockperson attitudes towards calves and calf welfare

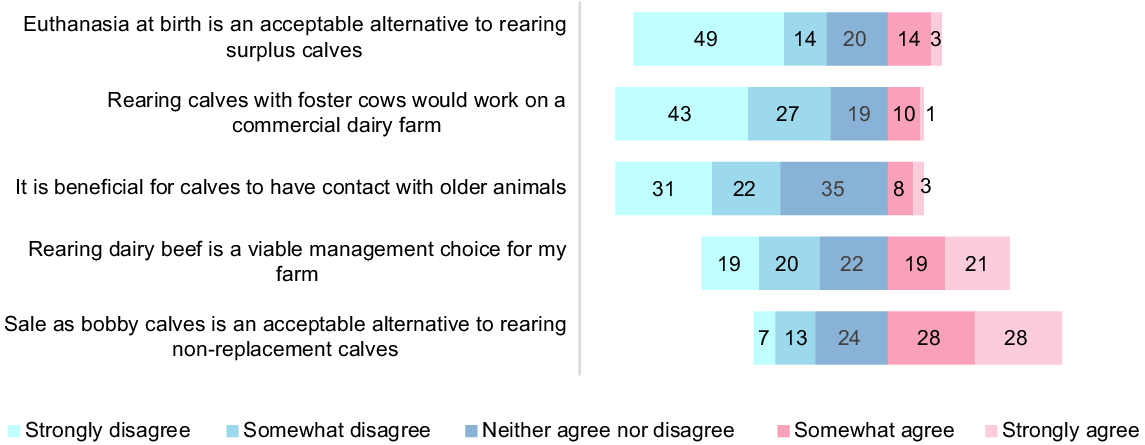

Only 12% of participants agreed with the statement ‘Calves are annoying,’ while 82% disagreed with the statement ‘Rearing calves is a less important job than other tasks on the farm’ (Supplementary Fig. S3). Few participants believed that it is beneficial for calves to have contact with older animals or that a foster-cow rearing system would work on a commercial dairy farm (Fig. 4). Fifty-six per cent of respondents believed that sale as bobby calves is an acceptable alternative to rearing non-replacement calves; conversely, only 17% believed the same of euthanasia at birth. Thirty-nine per cent of respondents did not believe that rearing calves for dairy beef was a viable management choice for their farm. PCA was able to group these variables into Component 4.

Component variable correlations

Table 3 reports correlations between composite variables and demographic data; few correlations were found and those that were significant tended to be of low strength. Component 4, which pertained to respondent attitudes towards current issues in calf welfare, was correlated with respondent gender, wherein respondents identifying as female were more likely to hold positive attitudes towards calf welfare, including the use of foster cows, and the unacceptability of euthanasia at birth (Table 3, ρ = 0.334, P = 0.013). Component 5, ‘Normative welfare promotion,’ was negatively correlated with whether the farm split their milking herd for management purposes, wherein respondents on those farms that did not split their herds were less likely to believe their trusted advisor valued practices associated with maintaining the welfare of their herd (ρ = −0.315, P = 0.003). Component 9 was negatively correlated with the respondent’s position of employment on the farm, wherein respondents likely to be less invested in the farm, such as casual or seasonal workers, were more likely to view heifers as underperforming (ρ = −0.346, P = 0.001).

| Demographic variable | Component number | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 A | ||

| Herd size (max. over 3 months) | 0.060 | 0.192 | −0.250* | −0.025 | 0.116 | −0.018 | 0.087 | 0.125 | −0.035 | |

| Milking duration (h) | 0.024 | 0.102 | −0.159 | −0.116 | .127 | 0.041 | 0.100 | 0.097 | −0.081 | |

| Feeding system B | −0.100 | −0.201 | −0.110 | −0.092 | 0.091 | 0.210 | 0.015 | 0.027 | −0.002 | |

| Split milking herd? C | −0.032 | −0.014 | 0.125 | 0.176 | −0.315** | −0.121 | −0.039 | −0.183 | −0.021 | |

| Calving pattern D | −0.090 | −0.235* | −0.048 | −0.082 | 0.120 | 0.212 | −0.110 | −0.171 | 0.126 | |

| Dedicated calf-rearer E | 0.196 | −0.098 | 0.067 | −0.038 | −0.269* | −0.115 | 0.216 | −0.182 | 0.056 | |

| Age | −0.062 | −0.086 | 0.079 | −0.118 | 0.126 | −0.105 | 0.044 | 0.236* | 0.113 | |

| Gender F | −0.230* | −0.102 | −0.032 | 0.334* | 0.059 | 0.115 | −0.224* | −0.004 | 0.021 | |

| Years in dairy | −0.095 | −0.051 | 0.108 | −0.150 | 0.073 | −0.036 | 0.096 | 0.072 | 0.062 | |

| Years on current farm | −0.057 | −0.082 | 0.120 | −0.106 | −0.005 | −0.077 | 0.226* | 0.053 | 0.078 | |

| Position on current farm G | 0.239* | 0.109 | −0.216* | −0.072 | 0.001 | 0.045 | −0.092 | 0.033 | −0.346** | |

Correlation coefficients for Spearman’s rho tests are presented. Items in bold signify statistical significance and a correlation coefficient within thresholds for reliability. Italicised items signify statistical significance but a correlation coefficient outside thresholds for reliability.

*Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

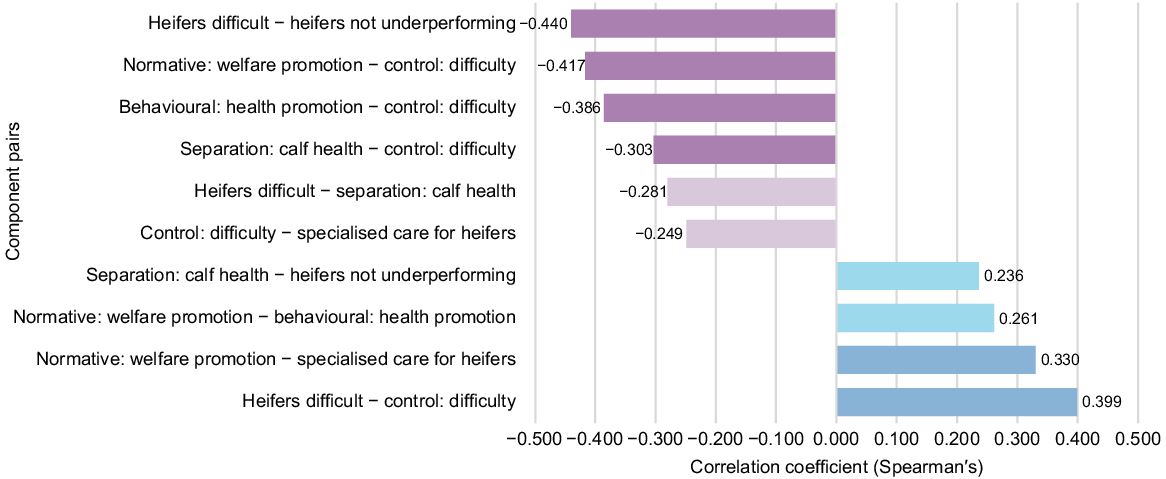

Fig. 5 outlines correlations between the composite variables where Spearman’s rank coefficient is >0.1; a full table of correlation coefficients is presented in Supplementary Table S6. Component 7, ‘difficulty of high-welfare practices’ was correlated with Component 1, ‘heifers difficult,’ indicating that believing that managing the herd according to higher-welfare practices was difficult was correlated with believing that heifers were difficult to handle in early lactation (P < 0.001). Furthermore, Component 7 was negatively correlated with Component 3 (‘cow–calf separation for calf health’; P = 0.006), Component 5 (‘normative welfare promotion;’ P < 0.001), and Component 6 (behavioural health promotion; P < 0.001). These correlations indicate that respondents who found managing the herd according to higher-welfare practices was difficult were less likely to believe that their trusted advisors valued these same practices or to believe that these practices were important themselves, and less likely to believe it was important to separate cows and calves for calf-health purposes.

Correlations between composite variables (Spearman’s rank coefficient of >0.1; P < 0.05; coefficients >0.3 indicate a statistical correlation).

Component 1, ‘heifers difficult,’ was negatively correlated with Component 9, ‘heifers not underperforming; P < 0.001), wherein respondents who believed heifers were difficult to handle in early lactation were more likely to believe that heifers on their farm were underperforming. Component 5, ‘normative welfare promotion’ was correlated with Component 8 ‘specialised care: all life stages’ (P = 0.003), wherein participants who perceived that their trusted advisors valued management practices associated with herd welfare were more likely to believe that it was important to provide tailored and specialised care to replacement heifers at all life stages.

Discussion

Demographics

Previous research has indicated that responses from 110 to 200 dairy producers is desirable to suitably capture the management practices of the industry (Abuelo et al. 2019). Random recruitment can, however, be time-consuming and costly. The present study used convenience sampling to survey 91 respondents. The questionnaire was distributed during the first 8 months of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020; sampling methodology was constrained by the ability of industry partners to assist while supporting producers through regulatory changes and unprecedented challenges, and the availability of producers to participate in research during this time. Although convenience sampling, particularly through social media, improves questionnaire accessibility and is particularly cost- and time-efficient compared with random recruitment, a potential limitation is a sample less representative of the wider population. As such, the results of the present study should not be considered as representative of the Australian dairy industry as a whole.

To help place the present sample in the context of the wider industry, comparisons were made between demographic data and recently reported industry data (Dairy Australia 2015, 2019, 2022). Reported calving patterns, for instance, reflect the general trends in the Australian dairy industry as reported in national data published by the industry body, Dairy Australia (2022). Victorian dairy regions were slightly under-represented, while proportions of Tasmanian and Western Australian respondents were almost double the relative proportion of farms in these regions (Dairy Australia 2019). The lower proportion of Victorian respondents may reflect a lack of a specific Victorian survey distributor from industry. Tasmanian dairy farms tend towards larger herd sizes than do those in other dairying regions, and this may be reflected in a higher representation from farms with herd sizes greater than the industry average of 279 cows than are proportionally present within the national industry (Dairy Australia 2020a).

From the 91 completed survey responses, 69% of respondents identified as female. A 2020 survey of 400 Australian dairy farmers reported that 25% of respondents were female, indicating that the present study’s sample has a higher proportion of responses from females than are active in the industry at large (Dairy Australia 2020b). Traditionally, the task of calf-rearing has been considered ‘women’s work’ both in Australia and internationally, with calf-rearing and animal-care tasks often undertaken by the ‘farmer’s wife,’ whether in a paid or unpaid capacity (e.g. Alston et al. 2017, 2018; Enticott et al. 2022; Palczynski et al. 2022). Indeed, both male and female participants surveyed by Sachs and colleagues in their 2014 study believed women were more suited to animal-care tasks due to their ‘nurturing’ capabilities (Sachs et al. 2014). The skew towards female participants, 97.8% of whom reported having on-farm calf-rearing responsibilities, is likely to be influenced by the subject matter. This suggests that the sampling bias towards female stockpeople, while not reflective of the Australian dairy industry at large, may suitably represent those in the industry primarily responsible for and interested in calf-rearing and replacement heifer management, and motivated to assist in research. Women have also previously been shown to be more likely to participate in surveys, and obtaining suitable male sample sizes has historically proven difficult (e.g. Green 1996).

Australian calf management

Most participants in this study indicated that their farm did employ a dedicated calf-rearer, while approximately a fifth did not. International research by Palczynski and colleagues (2022), undertaken on herds primarily calving year-round, reported that farmers associate employing a dedicated calf-rearer who feels responsibility for their animals with positive outcomes and optimal calf management, and improved attitudes towards calves and calf-rearing (Palczynski et al. 2022). This finding in the present study further suggests that convenience sampling may have resulted in over-representation of respondents proactive and interested in improving calf outcomes, compared with the industry at large.

In the present study, calf management choices were not correlated with milking-herd management choices. Farms that practiced more frequent calving periods (i.e. year-round or batch calving) were more likely to incorporate higher proportions of grain into the milking herd’s diet, which may reflect more intensive farming practices in general, rather than differences in calf management. Choices made regarding calf-rearing practices may be individualised to the farm, rather than dictated by particular farming systems.

Most respondents in the present study group-housed their replacement heifers, aligning with results from a 2022 industry survey of 400 farms, which indicated that, nationally, 90% of Australian dairy calves are housed in groups at some point during the rearing phase (Dairy Australia 2022). Interestingly, 14% of farms surveyed by Dairy Australia housed calves individually at some stage during the rearing phase, indicating that calves on some farms experience both forms of housing prior to weaning (Dairy Australia 2022). Recent research suggests that individually housing calves can negatively affect their behavioural development, social competence and cognition, while group-housing reduces stereotypies, improves feed intake and appears to have a positive influence on weight gain and affective state (Jensen et al. 1997; De Paula Vieira et al. 2010; Duve et al. 2012; see review by Cantor et al. 2019). Both industry data and data collected in the present study indicated that the majority of Australian dairy calves are afforded the benefit of social complexity through pair- or group-housing during early life, which may benefit their welfare compared with calves housed individually.

Very little research is published on the management and subsequent welfare of weaned replacement dairy heifers in pasture-based systems, either during the period from weaning to first lactation, or throughout the first lactation itself (reviewed by Verdon 2023). The post-weaning, pre-calving period in particular often sees Australian heifers housed extensively outdoors, with few opportunities for individual management or monitoring (Verdon 2023).

Participants tended to report being proactive in their approaches to heifer management, with most believing it is important to provide heifers with care tailored to their stage of life from birth through to the end of their first lactation. Respondents, for the most part, reported no difference in primiparous heifer performance during first lactation when compared with multiparous cows. This perception is inconsistent with most current research, which indicates that primiparous heifers have a lower milk yield and pasture intake than do multiparous cows (Peyraud et al. 1996) and a greater delay to resumed ovarian activity after calving (Zhang et al. 2010). There were some indications that these issues were also present on Australian farms in the present study, however; around a quarter of participants did indicate that heifers on their farms did not perform as well as multiparous cows in terms of maintaining body condition and feeding competitively; these may be particular areas in which heifers could be better supported, a finding supported by literature reviewed by Sowell et al. (2000) and Verdon (2023).

While it was reported that heifers on respondent farms performed suitably, the potential role of farm blindness in respondent perceptions should also be considered. The persistence of suboptimal farming strategies and animal performance, even in the face of scientific and industry advice, may be attributed to what has been defined by Mee (2020) as ‘farm blindness,’ wherein farmers fail to recognise problems in their own farming practices, or recognise problems but are blind to them, perhaps viewing them as ‘normal.’ In calf-rearing, such practices may include poor colostrum management, restrictive feeding regimes or blanket use of antimicrobials in instances of calf illness (reviewed by Verdon 2021). Furthermore, morbidity and mortality of dairy calves tends to be underestimated globally, and health and productivity records for youngstock are rarely as detailed as for the milking herd (Palczynski et al. 2022).

In the present study, less than 15% of participants reported splitting the herd to manage heifers separately for milking or to manage the nutritional needs of different groups. This did not explicitly account for electronic feeding systems wherein cows are fed individual concentrate rations. Combined, these results indicated that once heifers have calved and are integrated into the milking herd, they tend to regularly be managed identically to older, multiparous milking cows in the herd. Ensuring that heifers are supported during integration into the larger herd of experienced multiparous animals, and are given suitable access to adequate nutrition, will support them reaching their genetic potential and may improve first-lactation yields where performance is a concern (e.g. Bach 2011; Van De Stroet et al. 2016; reviewed by Verdon 2023).

Current issues in dairy calf management

Adult contact during early life, particularly with the dam, has been shown in recent literature to reduce fearfulness and neophobia, increase social motivation and skill, and improve the cognitive abilities of cattle (e.g. Le Neindre 1989; Duve et al. 2012; Wagner et al. 2013; Meagher et al. 2015; Field et al. 2023; reviewed by Cantor et al. 2019). Furthermore, the practice of cow–calf separation is not supported by participants in a range of public opinion studies across Europe and the Americas, indicating that the practice is increasingly incongruous with public values (Ventura et al. 2013, 2016; Busch et al. 2017; Cardoso et al. 2017; Hötzel et al. 2017).

Despite the benefits of early life dam contact, 84% of Australian dairy calves are removed from their dams within 48 h of birth, aligning with the recommendations of industry body Dairy Australia, which have been developed on the understanding that the promoted practices reduce disease transmission, promoting health and productivity outcomes (Dairy Australia 2022). Corresponding with Dairy Australia’s primary drivers for early life cow–calf separation, in the present study, the primary reasons for Australian dairy farmers separating cows and calves were to ensure adequate colostrum management, to prevent disease transmission and to improve ease of managing cows and calves (Dairy Australia 2022). Of these, colostrum management was of the highest importance to 90% of participants. A recent review of the literature indicated, however, that the risk of prolonged cow–calf contact to cow or calf health has been demonstrated as negligible in well managed systems (Meagher et al. 2019).

The motivations for cow–calf separation identified by respondents in the present study also align with producer concerns identified in international studies (e.g. Neave et al. 2022). The reticence of primarily pasture-based New Zealand dairy farmers towards cow–calf systems, for instance, was reported to be motivated by concerns around animal management including separation stress, milk intake and colostrum management, costs of appropriate infrastructure including shelter and fencing for calves, and increased labour linked to separation, grazing, calf, and reproduction management (Neave et al. 2022).

Given these motivations for cow–calf separation on farm, there appears to be unsurprisingly little enthusiasm within the Australian dairy industry for implementing cow–calf contact systems. Only 10% of participants agreed that it was beneficial for calves to have contact with older animals during early life, and only 10% of respondents believed that a foster-rearing system would work on a commercial dairy farm. These results indicated that any ongoing development of commercially viable cow–calf contact systems should consider how colostrum intake, disease risk including of Johne’s and mastitis, and animal husbandry can be best managed to ensure that risks to welfare and farmer concerns are pre-emptively addressed.

Both beef and dairy bulls are used to sire calves reared as Australian dairy beef; recent industry data indicate that in 2021–2022, 26% of calves born on Australian dairy farms were reared for dairy beef (Dairy Australia 2022). Furthermore, 16% of Australian farmers reported using beef genetics to increase the percentage of calves reared for dairy beef (Dairy Australia 2022). One participant in the present study reported specifically using beef sires over terminal or poor-producing cows to value-add on calves from cattle with less desirable genetics, indicating how such breeding programs may be used strategically within the industry. Despite this shift, industry data suggest that while 1% of calves born on Australian dairy farms in 2022 were euthanised at birth, only 29% of farms nationally did not send any calves to slaughter as bobby calves (Dairy Australia 2022). Fifty-six per cent of participants in the present study either agreed or strongly agreed that the sending calves to be slaughtered as bobby calves at a young age was an acceptable alternative to rearing non-replacement calves in the present study. Other respondents, however, voiced their preference for finding alternative homes for non-replacement calves, because ‘this is a better way of dealing with ‘unwanted’ or non-replacement calves than just getting rid of, or killing them ASAP because they’re of no value for the farm’ (Supplementary Table S4).

In an interesting contrast, 83% of participants did not believe that euthanasia at birth was an acceptable alternative to rearing non-replacement calves. International dairy research has similarly reported that farmers would prefer to rear calves on and give them a good life for a few weeks than practice early life euthanasia (Palczynski et al. 2022). While the reasons for these differing attitudes towards the varied pathways available to non-replacement calves cannot be extrapolated from the present data, one possible explanation may be that direct responsibility for the early life slaughter of calves on farm is associated with poor emotional outcomes for the individual involved, while slaughter external to the farm removes this personal responsibility (Vicic et al. 2022).

Approaches to non-replacement calf management reported in the present study were individualised not only to the farm, but often to the calf itself. The size, growth potential and likelihood of the animal to thrive was often noted, for instance. One participant reported that all bull calves were reared for dairy beef on farm ‘except male calves which are sired by Jerseys and are very fine-boned,’ another that ‘it may be euthanasia if very small and poor doing [sic],’ while another stated that ‘small bull calves are euthanised on farm.’ The market at the time of calving and the time of calving within the season itself also played a role; one participant sold bull calves ‘young, when [the] market is available,’ another stated that ‘if no market’ bull calves were euthanised, while yet another stated that ‘late calves are sold as bobbys [sic]’ (Supplementary Table S4).

Principal components

Many aspects of replacement-heifer welfare may be dictated by the quality of the human–animal relationships on-farm, from day-to-day interactions to choices made regarding ongoing management. Literature across a range of livestock species has demonstrated significant sequential relationships between farmer attitudes and behaviour, and animal welfare and productivity, including in dairy (e.g. Breuer et al. 2000; Seabrook and Wilkinson 2000; Hemsworth et al. 2002; Munoz et al. 2019, and reviewed by Waiblinger et al. 2006 and Napolitano et al. 2020). Both farmer self-reported behaviour, and farmer attitudes, have been correlated with on-farm outcomes, with farmer attitudes generally being a better predictor (Jansen et al. 2009). While the present study did not measure welfare outcomes on-farm, respondent attitudes towards certain behaviours or management practices may indicate to some extent the experiences of the animals they manage or handle on-farm.

Few correlations were found between the composite variables and herd or respondent demographics; this may indicate that sample size was not suitable to capture trends in variability across demographic categories. ‘Concern for calf welfare’ was correlated with the respondent being female. Female respondents were more likely to agree that rearing calves on foster cows could work on a commercial dairy farm, and that it is beneficial for calves to have adult contact. Further, they were more likely to believe that rearing non-replacement calves for dairy beef was a viable management choice for their farm of employment, and were less likely to support euthanasia at birth or sale of bobby calves as alternatives to rearing non-replacement calves. The disproportionate number of female respondents, potentially influenced by the traditional role of women as calf-rearers (69% of the total sample), may have further contributed to this finding; however, this result also aligns with current research. While Enticott et al. (2022) explored on-farm social structures and cultural norms that endure to primarily place women in animal-care roles, they also reported first-hand narratives wherein respondents identified nurturing instincts and a care for animals as drivers to their roles as calf-rearers. Female respondents have previously been shown to have greater concern for animal welfare in livestock production systems than have men, whether as stakeholders, including producers, animal scientists or veterinarians, or as members of the general public (e.g. Knight et al. 2004; Taylor and Signal 2005; Heleski et al. 2015; Doughty et al. 2017; reviewed by Herzog 2007).

The composite variable ‘normative welfare promotion’ comprised positive loadings for the trusted advisor believing practices such as ongoing training, maintaining herd health and productivity records, calf-rearing and the use of pain relief at dehorning were important. This composite variable was correlated with whether the farm split their milking herd for management purposes, wherein respondents on those farms that did split their herds were more likely to believe their trusted advisor valued such practices, associated with maintaining the welfare of their herd. In the present study, respondents were most likely to consider their farm owner, manager or veterinarian, or owners and managers of other farms as trusted advisors in regard to general on-farm issues. This finding indicates that these identified trusted advisors are central to promoting animal welfare within farm culture, and may be best placed to communicate when certain management choices, such as splitting the herd, may mitigate risks to animal health and welfare.

Lastly, respondents in higher positions of authority, such as farm owners or managers, were less likely to believe their heifers were underperforming than were casual or seasonal staff. The causal relationship of the correlation between respondent position on farm (i.e. casual vs. manager) and view of heifer performance cannot be determined from the available data alone. It can be hypothesised, however, that casual workers such as milkers may have more hands-on experience with first-lactation heifers during daily management, and may therefore form their attitudes towards heifer performance through their relationships with these animals, while farm managers may have access to a wider pool of data, including daily yield, herd testing data and how the animal performs within the farm’s greater strategy (i.e. meeting targets for in-calf rates). Exploring differences between worker position and the human–animal relationship on-farm may elucidate this hypothesis further.

Respondents who believed that managing the herd according to higher-welfare practices (such as using pain relief at disbudding, or maintaining herd health records) was difficult were less likely to believe that their trusted advisors valued these same practices or to believe that these practices were important themselves. These participants were also more likely to believe that heifers were difficult to handle in early lactation, and less likely to believe that it was important to separate cows and calves for calf health purposes. Additionally, respondents who believed that heifers were difficult to handle in early lactation were more likely to believe that heifers on their farm were underperforming. Positive behavioural and control beliefs towards animal-welfare factors have previously been linked to improved indicators of animal welfare (Jansen et al. 2009; Kauppinen et al. 2013). The present results indicate a similar but inverse relationship, wherein negative control and behavioural beliefs may indicate poor human–animal relationships, seen, for instance, in perceived difficulty of handling first-heifers. These correlations indicate that where respondents found undertaking these practices more difficult, there is evidence of greater systemic issues within farm management, wherein these respondents held more negative views both towards practices associated with upholding calf and herd health and towards first-lactation heifers under their care, did not believe that their trusted advisor valued these practices and did not value these practices themselves. Whether these correlations have any kind of causal relationship, and the causal direction of any such relationship, cannot be concluded using the current data.

Furthermore, participants who perceived that their trusted advisors, including their farm’s veterinarian, or owners and managers of other farms, valued management practices associated with herd welfare, including investment in the professional development of staff, were more likely to believe it was important to provide tailored and specialised care to replacement heifers at all life stages. External input into farm management choices ensures that normative beliefs and the on-farm culture of practice are balanced and can be challenged by differing opinions (Mee 2020; Palczynski et al. 2022). Palczynski and colleagues (2022) identified a reticence to rely on veterinarians specifically for calf-related advice in their interviews. Indeed, in cases of calf scours, only 17.9% of Australian respondents to Abuelo et al. (2019) used visits by veterinarians for diagnosis. Conversely, in other studies veterinarians have been reported as the most important source of advice by farmers (Kauppinen et al. 2013). Croyle et al. (2019) found that Canadian farmers trusted familiar consultants with whom they and their farm had a trusting relationship, and particularly veterinarians, to provide on-farm advice related to animal care, above other external stakeholders. While turning to vets for general advice was common in the present study, the influence and uptake of veterinary advice in correlation with calf management specifically was not explored.

The farm owner and/or manager was also often rated highly as a trusted advisor. Good leadership, personal development, a safe and healthy place of work, and feedback from supervisors have been identified by dairy workers as key attractants to workplaces, signifying the importance of supportive management not only for animal welfare but also staff motivation and retention (Kolstrup 2012). Ninety per cent of 400 respondents to an Australian industry survey agreed that investing in their own skills and knowledge was important, while 86% of respondents agreed that investing in staff skills and knowledge was important (Dairy Australia 2020b). While previous research has suggested that normative beliefs alone may not modify the relationship between individual attitudes and behavioural outcomes, adjusting the specific attitudes of individuals towards high-welfare management practices is crucial to successfully adjusting farm cultures and associated behaviours (Waiblinger et al. 2002; Coleman et al. 2003; Jansen et al. 2009; Hemsworth and Coleman 2011). In the case of the present data, for instance, positive normative beliefs pertaining to higher-welfare management practices were linked to both positive attitudes to heifer management, and to the individual feeling they had more control over achieving these practices.

Implications and future research

The results of the present study support the assertions of the HAR model (Hemsworth and Coleman 2011), in which normative, behavioural and control beliefs all play vital roles in determining stockperson behaviour in regard to youngstock on-farm. Firstly, providing education to ‘trusted advisors’ may shift farm cultures and attitudes towards youngstock management and the importance of the early life period. Communication with advisors has been identified by stockpeople across a range of studies as influencing perceptions of farm animal welfare (reviewed by Balzani and Hanlon 2020). Methods of utilising this influence may include providing education and extension to veterinarians and other non-farming industry professionals who actively and regularly engage with stockpeople responsible for youngstock care at all levels, and providing targeted education to farm managers and individuals making herd-level management decisions. This strategy may also mitigate the risk of farm blindness on health, welfare and developmental outcomes of dairy youngstock. Second, addressing the behavioural beliefs of all individuals responsible for youngstock care may support uptake of changes implemented or recommended by trusted advisors. This may be achieved, for instance, through research and extension available both on- and off-farm, and nurturing the leadership potential of individuals who value high-welfare calf and heifer management. Last, perceiving management tasks as difficult means stockpeople are less likely to undertake these tasks (e.g. Munoz et al. 2019). There is value in ensuring all stockpeople involved with youngstock management tasks crucial to ongoing animal welfare feel educated, empowered and supported to provide best care to the animals in their charge.

To determine the extent to which farm blindness affects replacement-heifer welfare and management, future research may choose to compare reported outcomes for heifers with on-farm measures including, for instance, milk yield and composition, body condition scores and heifer survivability. Related to this, of interest for future research may be exploring the extent of providing specialised care to heifers in early lactation and beyond the transition period, and the efficacy of certain management practices specialised towards heifers during this period, which best support their transition into the milking herd, such as training in the parlour prior to the commencement of lactation.

Finally, future research exploring wider industry attitudes and behaviour regarding calf-rearing and management should be conducted using random recruitment so as to obtain a more accurate understanding of whole-of-industry attitudes and behaviours. The present survey may best be described as primarily illustrating the attitudes and practices of the reported participants, with the potential to reflect the attitudes of Australian stockpeople involved with dairy youngstock, rather than those of the industry as a whole. A larger, more industry-representative survey should include those working with youngstock as well as those making whole-farm management decisions, to ensure that data do not solely capture those who prioritise youngstock and their management. Furthermore, accurate data on the type of employees responsible for calf-rearing on Australian farms should collected. Future research may also choose to explore gender differences in both labour roles related to calf-rearing and human–animal relationships with artificially reared calves, which may elucidate further contributing factors to these differences.

Conclusions

The main results of this study indicated that the management of calves born on Australian dairy farms, whether as replacement heifers or surplus to herd replacement requirements, varies considerably by farm. Contrary to our hypotheses, there were no apparent herd management, demographic or attitudinal factors that determined which calf management practices respondent farms may choose to undertake. The results did however indicate relationships among stockperson control, normative and behavioural beliefs pertaining to higher-welfare herd management practices such as using pain relief at dehorning or maintaining herd health records. Furthermore, our results indicated that stockpeople who perceive that these practices are more difficult tended to have more negative attitudes towards the calves and cows under their care. Future research should aim to explore causal relationships between the attitudinal relationships found in this study, and on-farm welfare outcomes.

Data availability

The data that support this study are available in the article and accompanying online supplementary material, or will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Declaration of funding

This work was conducted with the support of an Australian Government Research Training Program stipend, and a small grant provided by Dairy Australia. No input was given into this project by these bodies beyond the provision of funds.

Author contributions

Conceptualisation: L. F., L. H., E. J. and M. V.; methodology: L. F., L. H., E. J. and M. V.; funding acquisition: E. J.; investigation: L. F.; project administration: L. F.; validation: L. F.; data curation: L. F.; formal analysis: L. F. and L. H.; visualisation: L. F.; writing – original draft: L. F.; writing – review and editing: L. F., M. V., L. H. and E. J; supervision: M. V., L. H. and E. J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of this paper.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge that Aboriginal Australian peoples have been custodians of the lands, seas, and waterways of Australia, on which this research was conducted, for thousands of years, and that every part of Australia is, always was and always will be, Aboriginal land. We pay our respects to their Elders, past, present, and emerging. The authors further thank DairyTas, the NSW Department of Primary Industries, the Tasmanian Institute of Agriculture, and the Animal Welfare Science Centre for their assistance in distributing the questionnaire, and Dr Carmen Glanville from the Animal Welfare Science Centre for her statistical support during analysis.

References

Abuelo A, Havrlant P, Wood N, Hernandez-Jover M (2019) An investigation of dairy calf management practices, colostrum quality, failure of transfer of passive immunity, and occurrence of enteropathogens among Australian dairy farms. Journal of Dairy Science 102, 8352-8366.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Ajzen I (1991) The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 50, 179-211.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Alston M, Clarke J, Whittenbury K (2017) Gender relations, livelihood strategies, water policies and structural adjustment in the Australian dairy industry. Sociologia Ruralis 57, 752-768.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Alston M, Clarke J, Whittenbury K (2018) Contemporary feminist analysis of Australian farm women in the context of climate changes. Social Sciences 7(2), 16.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Alvåsen K, Roth A, Jansson Mörk M, Hallén Sandgren C, Thomsen PT, Emanuelson U (2014) Farm characteristics related to on-farm cow mortality in dairy herds: a questionnaire study. Animal 8, 1735-1742.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Bach A (2011) Associations between several aspects of heifer development and dairy cow survivability to second lactation. Journal of Dairy Science 94, 1052-1057.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Balzani A, Hanlon A (2020) Factors that influence farmers’ views on farm animal welfare: a semi-systematic review and thematic analysis. Animals 10, 1524.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Bertenshaw C, Rowlinson P, Edge H, Douglas S, Shiel R (2008) The effect of different degrees of ‘positive’ human–animal interaction during rearing on the welfare and subsequent production of commercial dairy heifers. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 114, 65-75.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Bolton SE, von Keyserlingk MAG (2021) The dispensable surplus dairy calf: is this issue a ‘Wicked Problem’ and where do we go from here? Frontiers in Veterinary Science 8, 660934.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Breuer K, Hemsworth PH, Barnett JL, Matthews LR, Coleman GJ (2000) Behavioural response to humans and the productivity of commercial dairy cows. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 66, 273-288.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Busch G, Weary DM, Spiller A, von Keyserlingk MAG (2017) American and German attitudes towards cow–calf separation on dairy farms. PLoS ONE 12, e0174013.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Cantor MC, Neave HW, Costa JHC (2019) Current perspectives on the short- and long-term effects of conventional dairy calf raising systems: a comparison with the natural environment. Translational Animal Science 3, 549-563.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Cardoso CS, von Keyserlingk MAG, Hötzel MJ (2017) Brazilian citizens: expectations regarding dairy cattle welfare and awareness of contentious practices. Animals 7, 89.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Coleman GJ, McGregor M, Hemsworth PH, Boyce J, Dowling S (2003) The relationship between beliefs, attitudes and observed behaviours of abattoir personnel in the pig industry. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 82, 189-200.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Croyle SL, Belage E, Khosa DK, LeBlanc SJ, Haley DB, Kelton DF (2019) Dairy farmers’ expectations and receptivity regarding animal welfare advice: a focus group study. Journal of Dairy Science 102, 7385-7397.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

De Paula Vieira A, von Keyserlingk MAG, Weary DM (2010) Effects of pair versus single housing on performance and behavior of dairy calves before and after weaning from milk. Journal of Dairy Science 93, 3079-3085.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Doughty AK, Coleman GJ, Hinch GN, Doyle RE (2017) Stakeholder perceptions of welfare issues and indicators for extensively managed sheep in Australia. Animals 7, 28.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Duve LR, Weary DM, Halekoh U, Jensen MB (2012) The effects of social contact and milk allowance on responses to handling, play, and social behavior in young dairy calves. Journal of Dairy Science 95, 6571-6581.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Enticott G, O’Mahony K, Shortall O, Sutherland L-A (2022) ‘Natural born carers’? Reconstituting gender identity in the labour of calf care. Journal of Rural Studies 95, 362-372.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Field LA, Hemsworth LM, Jongman E, Patrick C, Verdon M (2023) Contact with mature cows and access to pasture during early life shape dairy heifer behaviour at integration into the milking herd. Animals 13, 2049.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Fukasawa M, Kawahata M, Higashiyama Y, Komatsu T (2017) Relationship between the stockperson’s attitudes and dairy productivity in Japan. Animal Science Journal 88, 394-400.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Green KE (1996) Sociodemographic factors and mail survey response. Psychology & Marketing 13, 171-184.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Heleski CR, Mertig AG, Zanella AJ (2015) Stakeholder attitudes toward farm animal welfare. Anthrozoös 19, 290-307.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hemsworth PH, Coleman GJ, Barnett JL, Borg S (2000) Relationships between human-animal interactions and productivity of commercial dairy cows. Journal of Animal Science 78, 2821-2831.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Hemsworth PH, Coleman GJ, Barnett JL, Borg S, Dowling S (2002) The effects of cognitive behavioral intervention on the attitude and behavior of stockpersons and the behavior and productivity of commercial dairy cows. Journal of Animal Science 80, 68-78.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Herzog HA (2007) Gender differences in human–animal interactions: a review. Anthrozoös 20, 7-21.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hötzel MJ, Cardoso CS, Roslindo A, von Keyserlingk MAG (2017) Citizens’ views on the practices of zero-grazing and cow-calf separation in the dairy industry: does providing information increase acceptability? Journal of Dairy Science 100, 4150-4160.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Jansen J, van den Borne BHP, Renes RJ, van Schaik G, Lam TJGM, Leeuwis C (2009) Explaining mastitis incidence in Dutch dairy farming: the influence of farmers’ attitudes and behaviour. Preventive Veterinary Medicine 92, 210-223.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Jensen MB, Vestergaard KS, Krohn CC, Munksgaard L (1997) Effect of single versus group housing and space allowance on responses of calves during open-field tests. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 54, 109-121.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Kauppinen T, Valros A, Vesala KM (2013) Attitudes of dairy farmers toward cow welfare in relation to housing, management and productivity. Anthrozoos 26, 405-420.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Kielland C, Skjerve E, Østerås O, Zanella AJ (2010) Dairy farmer attitudes and empathy toward animals are associated with animal welfare indicators. Journal of Dairy Science 93(7), 2998-3006.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Knight S, Vrij A, Cherryman J, Nunkoosing K (2004) Attitudes towards animal use and belief in animal mind. Anthrozoös 17, 43-62.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Kolstrup CL (2012) What factors attract and motivate dairy farm employees in their daily work? Work 41, 5311-5316.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Le Neindre P (1989) Influence of rearing conditions and breed on social behaviour and activity of cattle in novel environments. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 23, 129-140.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Maller CJ, Hemsworth PH, Ng KT, Jongman EJ, Coleman GJ, Arnold NA (2005) The relationships between characteristics of milking sheds and the attitudes to dairy cows, working conditions, and quality of life of dairy farmers. Australian Journal of Agricultural Research 56, 363-372.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Meagher RK, Daros RR, Costa JHC, Von Keyserlingk MAG, Hötzel MJ, Weary DM (2015) Effects of degree and timing of social housing on reversal learning and response to novel objects in dairy calves. PLoS ONE 10, e0132828.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Meagher RK, Beaver A, Weary DM, von Keyserlingk MAG (2019) Invited review: a systematic review of the effects of prolonged cow–calf contact on behavior, welfare, and productivity. Journal of Dairy Science 102, 5765-5783.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Mee JF (2020) Denormalizing poor dairy youngstock management: dealing with ‘farm-blindness’. Journal of Animal Science 98, S140-S149.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Munoz CA, Coleman GJ, Hemsworth PH, Campbell AJD, Doyle RE (2019) Positive attitudes, positive outcomes: the relationship between farmer attitudes, management behaviour and sheep welfare. PLoS ONE 14, e0220455.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Napolitano F, Bragaglio A, Sabia E, Serrapica F, Braghieri A, De Rosa G (2020) The human−animal relationship in dairy animals. Journal of Dairy Research 87, 47-52.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Neave HW, Sumner CL, Henwood RJT, Zobel G, Saunders K, Thoday H, Watson T, Webster JR (2022) Dairy farmers’ perspectives on providing cow–calf contact in the pasture-based systems of New Zealand. Journal of Dairy Science 105, 453-467.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Palczynski LJ, Bleach ECL, Brennan ML, Robinson PA (2022) Youngstock management as ‘the key for everything’? Perceived value of calves and the role of calf performance monitoring and advice on dairy farms. Frontiers in Animal Science 3, 835317.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Panamá Arias JL, Spinka M (2005) Associations of stockpersons’ personalities and attitudes with performance of dairy cattle herds. Czech Journal of Animal Science 50, 226-234.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Peyraud JL, Comeron EA, Wade MH, Lemaire G (1996) The effect of daily herbage allowance, herbage mass and animal factors upon herbage intake by grazing dairy cows. Annales de Zootechnie 45, 201-217.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Proudfoot KL, Huzzey JM (2022) A first time for everything: the influence of parity on the behavior of transition dairy cows. JDS Communications 3, 467-471.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ritter C, Hötzel MJ, von Keyserlingk MAG (2022) Public attitudes toward different management scenarios for “surplus” dairy calves. Journal of Dairy Science 105, 5909-5925.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |