Effects of AM/PM feeding on behaviour, range use and welfare indicators of free-range laying hens

Afsana A. Jahan A , Hiep Thi Dao A B , Md Sohel Rana A C D , Peta S. Taylor E F , Tamsyn M. Crowley G H and Amy F. Moss

A B , Md Sohel Rana A C D , Peta S. Taylor E F , Tamsyn M. Crowley G H and Amy F. Moss  A *

A *

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

Abstract

AM/PM feeding (also known as ‘split-feeding’) is designed to meet a hens’ nutrient requirement via two diets, namely, high protein and energy in the morning/early afternoon (AM) and high calcium during the mid-afternoon/evening (PM), compared with a single conventional diet over 24 h.

The study aimed to investigate the effects of AM/PM feeding on free-range laying hens, focusing on welfare, behaviour and health. It was hypothesised that AM/PM feeding, aligned with the hen’s diurnal physiology, would improve behaviour, welfare, and health compared with a conventional diet.

The study was conducted at a free-range research facility by using two dietary treatments, namely, conventional layer hen diet (Control) and the AM/PM diet. Diets were fed to nine replicate pens of 20 hens each, giving a total of 360 Hy-Line Brown laying hens (18 pens) when they were between 34 and 53 weeks of age (WOA). The AM diet (2980 kcal/kg apparent metabolisable energy corrected for nitrogen (AMEn), 20.1% crude protein (CP), 2.5% calcium (Ca) was provided from 08:00 hours to 16:00 hours, and the PM diet (2580 kcal/kg AMEn, 17.5% CP, 5.6% Ca) from 16:00 hours to 08:00 hours. In contrast, the conventional diet (2780 kcal/kg AMEn, 18.8% CP, 4.1% Ca) was provided continuously. Hen behaviour was recorded using overhead cameras between 49 and 50 WOA and assessed via behavioural ethogram. Individual hen ranging behaviour was monitored using radio-frequency identification (RFID) from 39 to 48 WOA. Hen fearfulness was evaluated through tonic immobility and novel object test during 51–52 WOA. At 53 WOA, hens were assessed for health, tibia bone quality, and faecal glucocorticoid metabolites.

AM/PM feeding reduced feather pecking (P = 0.01) and increased outdoor range use (2.85 vs 2.47 h/day; P < 0.001). It also showed an effect approaching statistical significance for faster exploration of novel objects (P = 0.08). AM/PM feeding improved tibia ash content (P = 0.03) and breaking strength (P = 0.04).

AM/PM feeding demonstrated potential benefits for laying hen welfare, including reduced feather pecking, increased outdoor activity, and improved bone health, compared with the conventional diet.

AM/PM feeding may enhance the health and welfare of free-range laying hens, although further long-term studies are needed to confirm its potential.

Keywords: calcium, energy, hen behaviour, hen welfare, nutrition, poultry, precision feeding, protein, ranging behaviour, split-feeding.

Introduction

Optimising nutrition and feeding strategies in layer hen farming is paramount to ensure better production, health and welfare (Bryden et al. 2021). In conventional feeding systems, hens are fed on a single but complete diet, with a constant nutrient supply over the day. However, hens may not optimally utilise all the nutrients provided in the diet because of bio-cyclic nature of their reproductive physiology (Molnár et al. 2018a; Moss et al. 2023). For instances, in a selective feeding system, hens exhibit higher protein and energy intake in the morning, with increased calcium (Ca) intake occurring later in the day around the time of eggshell formation (De los Mozos et al. 2012). This indicates that hens can adjust their nutrient intake on the basis of physiological needs (Leeson and Summers 2009).

The AM/PM feeding (also called ‘split feeding’) is a precision feeding strategy where daily nutrient requirements are blended into two different diets, consisting of a diet rich in protein and energy in the morning (AM) and a diet higher in Ca in the afternoon and evening (PM) (Molnár et al. 2018a; Abd El-Razek et al. 2020). The fundamental principle of AM/PM feeding is aligning nutrient availability with the biological clock of the egg-laying cycle, which dictates that hens need accessible amino acids and energy in the morning to deposit the egg albumen around the yolk, and the requirement of Ca is high once the eggshell formation starts before the dark period (Hiramoto et al. 1990; Penz and Jensen 1991). This highlights the potential of AM/PM diets, formulated with precise amounts of protein and essential nutrients, to align more effectively with hens’ circadian rhythms and egg production cycles, optimising dietary efficiency. Previous studies have shown that hens offered AM/PM diets had increased egg mass and feed efficiency compared with those fed conventional diets (Umar Faruk et al. 2010; Abd El-Razek et al. 2020; Jahan et al. 2024), and similar egg production and egg quality to hens offered conventional diets (Lee and Ohh 2002; De los Mozos et al. 2014; Abd El-Razek et al. 2020; Jahan et al. 2024). Furthermore, research by De los Mozos et al. (2014) showed that using a split-feeding approach allows for reducing average nutrient intake below standard recommendations without negatively affecting performance or eggshell quality. This may indicate the opportunity for an AM/PM diet to allow hens to utilise the dietary supply of nutrients more competently and thus reduce feed cost (De los Mozos et al. 2012; Pottgüter 2016; Jahan et al. 2024).

Moreover, chickens may exhibit different activity patterns depending on the feeding schedule, resulting in various effects on behaviour and welfare (Gilmet 2015; Dixon et al. 2022). For example, feather pecking and cannibalism are injurious pecking behaviours in laying hens, and can be caused by nutritional deficiencies (Van Krimpen et al. 2005; Mens et al. 2020). Ensuring timely provision of essential nutrients may help mitigate these undesirable behaviours. Moreover, aligning Ca uptake more closely with the time when it is needed is hypothesised to enhance both production and welfare. This improvement could be achieved by strengthening bones, potentially reducing keel bone fractures, which not only represent a significant welfare concern but also negatively affect egg production (Nasr et al. 2013; Wei et al. 2020). Additionally, the predictability of feeding times and nutrient availability can enhance the overall sense of security among hens, reducing anxiety and promoting a more relaxed environment for expressing natural behaviours (Rodenburg et al. 2010; Shcherbatov et al. 2021). In contrast, each feeding event can be associated with increased competition for resources, particularly if there is limited access to feeders (Sirovnik et al. 2018). Frequent disturbances associated with multiple feeding times can also potentially induce stress responses that may affect overall hen welfare and productivity (Akinyemi and Adewole 2021; Bryden et al. 2021). Although there are some positive indications in the literature on the effects of AM/PM feeding in laying hens (Umar Faruk et al. 2010; Abd El-Razek et al. 2020; Jahan et al. 2024), the impact on hen behaviour and welfare has not yet been examined. So, apart from economic benefit, it is also important to carefully monitor and assess the effects of AM/PM feeding on hen behaviour and welfare.

In many countries, the banning of cages has led to an increase in the utilisation of ‘loose’ housing, including free-range housing systems, for hens. These systems entail welfare risks due to heightened occurrences of collisions, resulting in higher incidences of keel bone fractures (Richards et al. 2012; Heerkens et al. 2016). Moreover, undesirable behaviours such as feather pecking and cannibalism, as well as increased stress levels, are commonly observed in such housing systems (El-Lethey et al. 2000; Schwarzer et al. 2022). More frequent feeding events provide hens with additional incentives to be active and engage in natural behaviours, including ranging and foraging (van Emous and Mens 2021). Therefore, the impact on the behaviour and welfare of laying hens in free-range systems under the AM/PM feeding regime is an important aspect that is yet to be determined. A complementary aspect of a similar study also demonstrated that AM/PM feeding reduced the cost of production without affecting the laying performance and egg quality of free-range hens (Jahan et al. 2024).

The objective of the present study was to test AM/PM feeding as a nutritional strategy to improve hen welfare in Australian free-range conditions. The study hypothesised that, compared with hens offered conventional layer hen diet, hens offered the AM/PM diet would demonstrate improved bone strength, reduced levels of fearfulness, stress, and abnormal behaviours, and increased use of the outdoor range.

Materials and methods

The study design was approved by the University of New England Animal Ethics Committee, Armidale, New South Wales (NSW), Australia (Approval number: ARA21-105). The procedures and protocol met the requirements of the Australian Code of Practice to Care for and Use of Animals for Scientific Purposes (NHMRC 2013).

Birds and animal husbandry

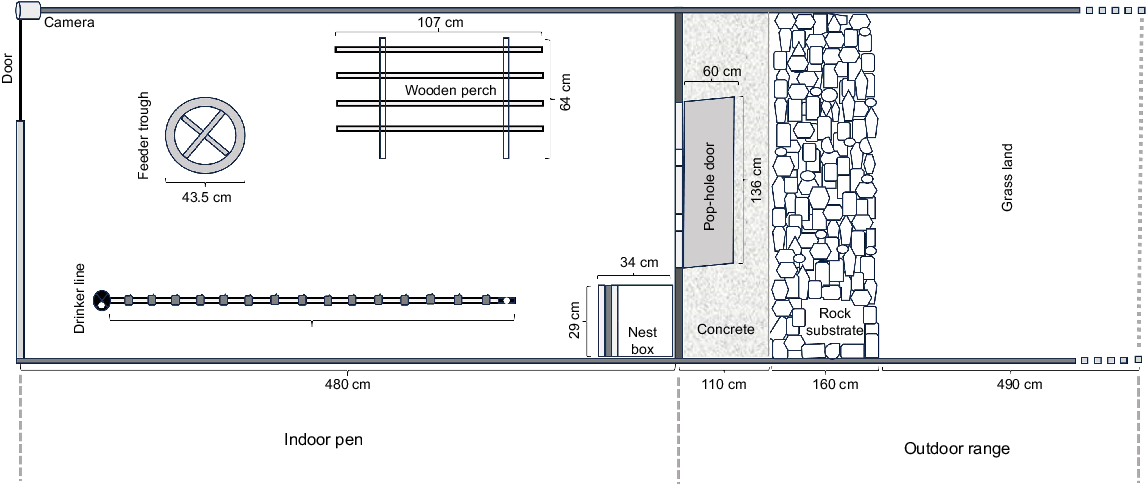

This study was a complementary part of the previous study, and bird care and animal husbandry have been described in Jahan et al. (2024). Hy-line Brown laying hens (n = 360) of 32 weeks of age (WOA) were used for this study and those hens were previously used in a cage housing system to standardise dietary requirements of each nutrient (e.g. protein, energy, and Ca) for the AM/PM diets by using Box–Behnken response surface design, devised by Box and Behnken (1960). For that case study, pullets (reared in a commercial loose housing system that adhered to Australian standard guidelines) at 18 WOA purchased from a local commercial layer farm in Tamworth, NSW, Australia, were brought to the University of New England (UNE) Laureldale indoor experimental research facility for poultry (naturally ventilated curtain-sided shed). Birds were randomly distributed into 180 cages (30 cm width (W) × 50 cm depth (D) × 45 cm height (H)) in pairs and reared with randomly allocated specified treatment diets until 32 WOA. Following the completion of the cage study, the hens were moved to the free-range indoor shed for the current study, but they were not given immediate access to the outdoors. To minimise the possible carryover effects from the earlier study, hens were randomly relocated into 18 floor pens (20 hens/pen) with a stocking density of 2.31 hens/m2. Each pen (480 cm L × 180 cm W) was equipped with a circular feeding trough (39 cm H × 43.5 cm D, with a circumference of 136 cm) with a feeding space of 74.3 cm/hen and an automated nipple drinker system (a set of nipple drinkers connected by a shared water line) suspended at the birds’ eye level (Fig. 1). Additionally, there was a single perch with three rungs (107 cm L × 64 cm W × 80 cm H) and a roll-away nest box (34 cm L × 29 cm W × 24 cm H), all resources were designed to meet the standard specifications outlined in the Australian Model Code of Practice for the Welfare of Animals: Domestic Poultry (Primary Industries Standing Committee 2002). The litter used consisted of fresh wood shavings, with a depth ranging from 5 to 7 cm. Pens were partitioned by wire panelling featuring 90% UV shade cloth (1 m height) to obstruct visual contact between the hens in adjacent pens. The indoor shed temperature was environmentally controlled and relative humidity was adjusted by an automatic ventilation system.

A layout of the indoor pen and outdoor range, showing placement and dimension of the perch, nest box, drinker, feed trough, mounted camera, pop-holes for range access and range substrates.

Each pen was connected to an outdoor area (760 cm L × 180 cm W) enclosed by wire fences, maintaining a stocking density of approximately 1.46 hens/m2 (Fig. 1). Access to the outdoor range was provided through a single pop-hole (136 cm W × 60 cm H). The area adjacent to the pop-holes comprised 110 cm of concrete path, followed by 160 cm of river rock, and the rest of the area was covered by grasses without additional trees or shelter/shade. The quantity of forage on the range varied on the basis of the hens’ utilisation of the range.

On transfer to the new facility at 32 WOA, hens were randomly assigned to new dietary composition (standard layer hen diet), which differed from both their previous diet in the cage facility and the experimental dietary treatments in the current study. A 2-week acclimatisation period was provided to allow the hens to adapt to both the new diet and the facility conditions. At 34 WOA, the hens were weighed and assigned to the experimental dietary treatments, with unrestricted access to feed and water throughout the trial. The starting hen weights did not differ between the dietary treatments (P > 0.05) across the pens. Hens were given access to the outdoor range at 39 WOA through pop-holes that were automatically operated by timers, opening at 09:00 hours and closing at 18:00 hours. However, because of recurring issues with the fencing (e.g. broken fences) on the range, the hens were not provided with any range access from 48 WOA. Lighting within the layer hen shed was provided by poultry-specific white LED bulbs (IP65 Dimmable LED Bulb, B-E27:10W, 5K; Eco Industrial Supplies, Zhenjiang, China), programmed for a 16 h light (04:00 hours to 20:00 hours) and 8 h dark (20:00 hours to 04:00 hours) cycle by using an automatic timer throughout the study. The lighting duration for feeding the hens was balance between the AM and PM diets (8 h). No hen mortality was found during the study.

Experimental design and dietary treatment

Following the principles of the Box–Behnken response surface design, birds were provided with varied diets containing different proportions of individual nutrients to determine the optimal levels of energy, protein and Ca for both AM and PM diets within the 22–32 WOA in the previous study of the same project (Akter et al. 2025). The selected values, based on growth, laying performance, egg quality, and nutrient digestibility during this timeframe, were employed in the current free-range study. In this study, hens were fed in two different groups but three distinct dietary formulations in mash form between 34 and 53 WOA, including (a) conventional layer hen diet as the control group, (b) AM (higher in protein and energy and lower in calcium) and PM (lower in protein and energy and higher Ca) diet (AM/PM) as the treatment group (Table 1). Therefore, hens were divided into two groups (nine replicate pens for each group, designed in an alternative order, with 20 hens/pen). The control group received the conventional diet for all times, whereas the treatment group (AM/PM) received the AM diet in the morning/early afternoon (08:00 hours to 16:00 hours) and the PM diet in the mid-afternoon/evening and early morning (16:00 hours to 08:00 hours). The AM/PM feeds were swapped manually twice daily at 08:00 hours (replacing the PM feed with the AM feed) and 16:00 hours (replacing the AM feed with the PM feed) by the same experimenter to ensure that the birds had equal feeding times for the AM diet (08:00 hours to 16:00 hours, 8 h) and the PM diet (afternoon/evening: 16:00 hours to 20:00 hours, 4 h; early morning: 04:00 hours to 08:00 hours, 4 h). Any leftover feed in the feeder was removed before each feeding change. Although hens had access to the PM diet during the early morning, the term ‘AM/PM’ specifically refers to feeding sessions scheduled to begin in the morning and afternoon. The analysis of the nutritional profiles was previously described in Jahan et al. (2024). All final diets were prepared at the UNE Centre for Animal Research and Teaching Facility and analysed for nutrient composition to confirm the diet composition (Table 2).

| Ingredient (%, otherwise as indicated) A | Control diet | AM diet | PM diet | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soybean meal | 12.710 | 15.600 | 11.860 | |

| Barley | 10.000 | 10.000 | 10.000 | |

| Wheat | 51.860 | 50.200 | 46.710 | |

| Canola meal | 10.000 | 10.000 | 10.000 | |

| Canola oil | 3.710 | 3.600 | 4.000 | |

| Limestone | 10.720 | 7.600 | 11.710 | |

| Salt | 0.160 | 0.330 | 0.190 | |

| Monocalcium phosphate | 0.390 | 0.180 | 0.980 | |

| Sodium bicarbonate | 0.240 | 0.000 | 0.200 | |

| L-lysine HCl | 0.060 | 0.062 | 0.007 | |

| D,L-methionine | 0.137 | 0.173 | 0.092 | |

| L-threonine | 0.010 | 0.019 | 0.000 | |

| Choline chloride 60% | 0.027 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Layer vitamin–mineral premix A | 0.100 | 0.100 | 0.100 | |

| Pigment (Jabiru) red | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.004 | |

| Pigment (Jabiru) yellow | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.003 | |

| Xylanase (Axtra XB) B | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.010 | |

| Phytase (Axtra Phy) C | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.010 | |

| Bentonite | 0.000 | 2.200 | 4.100 | |

| Calculated nutrient composition | ||||

| AMEn (kcal/kg) | 2780 | 2980 | 2580 | |

| CP (%) | 18.800 | 20.100 | 17.500 | |

| Crude fat (%) | 5.300 | 6.700 | 3.600 | |

| Crude fibre (%) | 2.900 | 3.000 | 2.800 | |

| Digestible arginine (%) | 1.013 | 1.097 | 0.926 | |

| Digestible lysine (%) | 0.810 | 0.900 | 0.760 | |

| Digestible methionine (Met) (%) | 0.440 | 0.511 | 0.410 | |

| Digestible cysteine (Cys) (%) | 0.288 | 0.303 | 0.274 | |

| Digestible met + cys (%) | 0.735 | 0.820 | 0.691 | |

| Digestible tryptophan (%) | 0.214 | 0.229 | 0.198 | |

| Digestible isoleucine (%) | 0.670 | 0.720 | 0.619 | |

| Digestible threonine (%) | 0.570 | 0.630 | 0.527 | |

| Digestible valine (%) | 0.774 | 0.826 | 0.720 | |

| Calcium (%) | 4.100 | 2.500 | 5.600 | |

| Available phosphorus (%) | 0.450 | 0.450 | 0.450 | |

| Sodium (%) | 0.170 | 0.170 | 0.170 | |

| Chloride (%) | 0.230 | 0.230 | 0.230 | |

| Choline (mg/kg) | 1400 | 1400 | 1400 | |

| Linoleic acid (%) | 1.670 | 2.050 | 1.250 | |

| Nutrient (%, otherwise as indicated) | Control diet | AM diet | PM diet | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DM | 91.40 | 91.07 | 91.98 | |

| GE (kcal/kg) | 3688 | 3787 | 3500 | |

| CP | 17.46 | 19.04 | 16.09 | |

| Ca | 4.53 | 3.12 | 5.10 | |

| P | 0.52 | 0.52 | 0.58 | |

| K | 0.96 | 1.06 | 1.00 | |

| Mg | 0.36 | 0.34 | 0.33 |

DM, dry matter; GE, gross energy; CP, crude protein; P, phosphorus; K, potassium; Mg, magnesium.

Data collection

Data were collected during 34–53 WOA. Behavioural observation on individual hens was performed at the pen level by using a behavioural ethogram during 49–50 WOA. Hen ranging behaviour was recorded via RFID during 39–48 WOA when hens had access to the outdoor range area. A series of hen welfare assessment tests were performed during 51–52 WOA. A subset of hens (four per pen, 36 per treatment) from each pen was sacrificed at the end of the study for keel bone fracture, bone health quality, and faecal glucocorticoid metabolites measurement. All the procedures are described in detail below.

Climatic variables

Climatic variables including environmental temperature and relative humidity inside the layer hen shed were recorded daily in the morning and evening with a thermometer/hygrometer (Temp Alert, FCC RoHS, 2011/65/EU, FCC: R17HE910, S4GEM35XB, USA) throughout the study duration (Table 3). Outdoor weather conditions were extracted from meteorological historical weather stations for the period of hen-ranging behavioural observation (Australian Government Bureau of Meteorology weather stations located within 0.5 km from the farm, Supplementary Table S1).

Hen behavioural observations

The behavioural time budgets of hens in their home pens were assessed using the scan sampling technique outlined in Rana et al. (2024), during the period from 49 to 50 WOA (Table 4). To minimise human interference in hen behaviour and accommodate camera limitations, 16 of the 18 pens (eight pens per treatment) were recorded over 2 weeks, with four pens per treatment recorded each week by using overhead cameras (SWDVK-446804WL, Swann, Port Melbourne, VIC, Australia) connected to a shared network video-recording system. Video files were extracted and analysed by a trained observer to evaluate the hens’ behavioural repertoire. After addressing recording equipment malfunctions, two continuous, uninterrupted observational days were selected for analysis from the recorded footage. The same observational days across the pens in each week of scanning (e.g. eight pens per week, four pens per treatment) were chosen on the basis of video quality and minimal human interference, ensuring that no additional tests were conducted on those days apart from routine egg collection and feed exchange by the same experimenter. Data interrater reliability was initially verified using two trained observers and a shared behavioural ethogram (intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.826). Scan sampling was performed at the group (pen) level during two periods of the day (morning: 08:00 hours to 10:00 hours; afternoon: 13:00 hours to 15:00 hours) with pop-holes closed. Behaviour was recorded during 30 s scans at 15 min intervals, resulting in eight scans per 2 h sampling period, 32 scans per pen across 2 days, and 256 scans per treatment. For each scan, the first observed behaviour of each hen (20 hens per pen) was recorded, yielding 640 behavioural counts per pen over two days (20 hens × 32 scans) and a total of 10,240 scans across 16 pens. Hens not visible in scanning were recorded as ‘unknown’. Behavioural counts were summed for each pen, resulting in a single value representing the entire 2 h observation period. These values were then converted into proportions of observations per pen for subsequent analysis, providing a standardised measure of time budgets across treatments.

| Behaviour | Definition | |

|---|---|---|

| Perching | Standing or sitting on the perch with both feet touching the perch rungs | |

| Feeding | Pecking or eating at the feed trough | |

| Drinking | Pecking or swallowing water at the nipple drinkers | |

| Standing | In an upright position with both feet on the floor or perch, but with the body not touching the floor or perch and inactive | |

| Preening | Grooming of feathers through beak manipulation by moving their head | |

| Ground pecking | Head below the midpoint when hens are standing, and head moved and an object touched with a beak at the ground substrate | |

| Ground scratching | Moving one or both feet across the ground in a repetitious manner | |

| Environmental pecking | The head moved and an object touched with a beak that is aimed at other resources rather than substrate on the ground | |

| Resting | Seated in a relaxed posture with legs tucked under the body, eyes remain open or closed while maintaining an upright head position that allows for subtle movement | |

| Gentle pecking | Touching a flock mate with its beak in a manner that does not cause the flock mate to startle or did not lead to the displacement of conspecific | |

| Severe feather pecking | Touching a flock mate with a beak in a manner that causes the recipient to retreat, startle or adopt a submissive crouching posture | |

| Dust bathing | Rubbing the head and body on the ground, rolling or shifting within the substrate, spreading wings and shaking, feathers becoming dishevelled, and kicking substrate onto the body | |

| Leg stretching | Resting with the head touching the ground, legs laid out on either side of the body, except during the dustbathing sequence | |

| Lying | Recline on either side of the body, with the head extended or bent over the neck, and both feet stretched out on the same side, except as part of the dustbathing sequence | |

| Body shaking | Abrupt jerking of the entire body including head and tail, except shaking the dust from the body or ruffling of the feathers after dust bathing | |

| Wing flapping | Extending the wings and moving up and down while standing, except immediate action following dust bathing | |

| Wing leg stretching | Hens extend one leg backward and simultaneously spread their wings while standing | |

| Walking | Hens actively moving around the pen but does not exhibit the other specified behaviours | |

| Unknown | Hens were not captured properly in the video recording, so specified behaviours remained unknown |

Individual hen ranging behaviour was monitored by RFID technology during 39–48 WOA. However, because of some technical issues with the recording system (e.g. video unrecorded/corrupt data files), the reliable RFID data were available for statistical analysis consecutively for 14 days for each pen during Weeks 46–47. RFID tags (27 mm × 9.7 mm, ALN 9715 Glint, Alien Technology, San José, CA, USA) were attached to 6 mm wide plastic leg bands (<1 g) and secured wrapping by a small piece of duct tape to prevent detachment. Before use, tags were validated by attaching them to a stick and passing them 10 cm above an RFID antenna (1200 mm L × 180 mm W × 20 mm H) (RL-A1200 12dBi Asset Management UHF RFID Antenna, Reliable RFID, Shenzhen, China) five times. Tags that were successfully read all five passes had their ID recorded and were attached to the right leg of each hen. Antennas were installed inside and outside each pop-hole (one set per pen), approximately 10 cm from the pop-hole. To ensure that hens passed over the antennas, weighted buckets were placed on either side, preventing hens from bypassing the system when they went outside. Data were cleaned by removing outliers by residual plot, including any accidental reads while pop-holes were closed overnight. No unexpected pop-hole closures were observed during the scheduled opening times.

Hen welfare assessment

A total of 54 hens (three per pen, 27 per treatment) underwent individual tonic immobility (TI) testing across a day at 51 WOA, following the protocol described in Rana et al. (2024). Hens were randomly selected, gently picked up in hand by the experimenter within the pen, and brought to a separate testing room adjacent to the home pens, separated by a door. During transport, a small cloth was placed over the hens’ heads to minimise stress. The order of testing pens was balanced across treatment groups. For the test, each hen was placed on its back in a U-shaped cradle, with its head hanging down over the edge. The experimenter restrained the hen by placing one hand on its breast and gently holding its head down with the other hand for 10 s. On release, a timer was started to measure the duration of TI, defined as the time until the hen resumed an upright position, with a maximum observation time of 600 s. If the hen righted itself within 10 s of initiation, TI was reintroduced, up to a maximum of five attempts. Both the number of induction attempts and TI duration were recorded. Hens that remained immobile for the full 600 s were assigned a TI duration of 600 s, while hens requiring five failed induction attempts were assigned a duration of 0 s. A prolonged TI duration is indicative of a heightened fear response, suggesting increased stress sensitivity and reduced coping ability of the bird (Jones 1986). Following the completion of the test, hens were promptly returned to their home pen and marked with a unique identification tag to avoid recapturing.

A novel object test (NOT) was conducted at the pen level when hens were 52 WOA as described in Rana et al. (2024). The test was performed in the same pens as used for home pen behavioural observation (16 pens of 18; 8 pens/treatment) by using four successive individual sessions, with four pens tested simultaneously in each session. Four experimenters were assigned to introduce the test by placing a novel object (rectangular untreated pine block covered with multi-colour adhesive scotch tape; 30 cm L × 7 cm W) at the centre of each pen, and then leaving the pen immediately. The test began once the object was placed on the ground and lasted for 5 min. After each session, the novel objects were removed, and the process was repeated for the remaining pens. The entire duration of the tests was video-recorded through over-head cameras (SWDVK-446804WL, Swann, Port Melbourne, VIC, Australia) linked to a shared network video-recording system. To enhance data accuracy, the test observations were restricted to the first 3 min of the test to avoid challenges associated with counting hens as interaction frequencies increased over time. An experienced observer, blinded to the treatments, recorded the following hen behaviours: latency (s) for the first three hens to approach the object, the number of hens (frequency) approaching the object, latency (s) for the first hen to peck the object, and the number of hens (frequency) of pecking during the 3 min observation period. A circle with a radius of 25 cm around the novel object was delineated on the computer screen, originating from the centre of the object to obtain these data. Inter-observer reliability was verified using two trained observers (intraclass correlation coefficient: 0.894). Approach behaviour was defined as a hen moving within 25 cm of the object, with its head and neck being positioned inside the delineated circle around the centre of the object. If no hens approached within 3 min, the latency was recorded as 3 × 180 s. Multiple approaches by the same hen were counted if the hen withdrew and showed no immediate interest before reapproaching. Pecking behaviour was defined as a hen contacting the object with its beak. If no pecking occurred within the 3-min period, the latency was recorded as 180 s. The frequency of hens pecking the object was tallied without considering individual bird identification for the entire duration of the test. A delayed latency to approach or peck the novel object was interpreted as indicative of heightened fearfulness (Forkman et al. 2007).

At 52 WOA, all hens underwent external health and welfare assessment following the scoring system outlined in Table 5. Feather conditions were evaluated across multiple body regions, including the neck, breast, back, wings, tail, belly, and vent as outlined in the welfare assessment protocol of Welfare Quality® (2019). Damage severity was scored on a scale of 0 to 2, where 0 indicated no damage and 2 represented severe damage, such as bare skin areas of ≥5 cm. The number of comb wounds, whether fresh or healed (wounds were readily apparent under light, irrespective of any differences in comb colour), was tallied. Body condition was assessed through palpation, evaluating keel bone prominence, breast muscle contour, and fat deposition. Scoring ranged from 0 (indicating a fatty condition with rounded breast muscle and keel) to 2 (indicating prominent keel ridges and shiny breast muscle appearance), as described in Welfare Quality® (2019). Each bird was held securely by both legs with one hand while the other hand palpated the keel and adjacent breast muscles to assess muscle development, keel protrusion, and breast contour curvature. Additionally, assessments recorded the presence or absence of damage to beak heads, toenails, and footpads, as well as other indicators of illness or injury. At the end of the study (53 WOA), a subset of hens from each pen (4 hens/pen, n = 72) was humanely killed through electrical stunning followed by decapitation to further assess keel bones and tibia quality. Keel bones were examined after skinning to identify deformities or fractures. Deviations were scored as 0 (no deviation), 1 (mild or hairline fracture), or 2 (moderate to severe fracture), following the definitions described in Welfare Quality® (2019). To ensure consistency, all welfare evaluations were performed by the same experienced observer.

| Health parameter | Indicator | Definitions | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feather condition (neck, breast, back, belly, wings, vent, and tail) | Score 0 | Good plumage coverage with minimal or no worn or deformed feathers | |

| Score 1 | Feathers have been damaged, with moderate or small bare patches (<5 cm) but the skin remains nearly covered by feathers | ||

| Score 2 | Feathers have been extensively damaged, with significant bare patches (≥5 cm) and/or only very small areas covered by feathers | ||

| Body condition | Score 0 | A well-developed smooth to moderate breast muscle contour with keel, which is fatty in condition | |

| Score 1 | A well-developed slightly to moderate prominent keel with flat breast muscle typically exhibiting a flat contour rather than a concave shape, which is in good condition | ||

| Score 2 | A severely prominent keel with reduced overall breast muscle and slight concavity alongside the keel, which is in shiny appearance | ||

| Keel | Score 0 | No obvious deviations, deformities or thickened areas, and the keel bone is entirely straight | |

| Score 1 | Slight deviations (e.g. flattening, s-shape) or minor thickened area, and/or keel bone slightly bended | ||

| Score 2 | Significant deviation and/or deformities of keel bone or presence of large, thickened area |

The same subset of hens (4 hens/pen, n = 72) as used for keel bone examination, were used for bone quality assessment. Tibia bones were excised and manually de-fleshed with a scalpel and scissors immediately after collection, and then transferred to the laboratory in a cool box. The fresh wet bones were weighed using a Discover Precision balance (FX-3000i, A&D Company Ltd, Tokyo, Japan), and placed in a fume hood for air-drying for at least 48 h, followed by re-weighing before being stored at 5°C for further analyses. Later, air-dried tibia samples (n = 71, one bone being excluded owing to being broken) were subjected to morphological measurements (length, diameter, and Seedor index), breaking strength, ash and mineral content. First, tibia length and diameter (middle point of the bone) were measured with a Kincrome 0–150 mm Digital Vernier calipers (Kincrome, Melbourne, VIC, Australia). The tibia Seedor index (mg/mm) was calculated by dividing the weight (mg) by the length of air-dried tibia (mm) as described by Seedor et al. (1991). Then tibia samples were subjected to a breaking strength test using an Instron® electromechanical universal testing machine (Instron® Mechanical Testing Systems, Norwood, MA, USA), ensuring precise and reliable measurement of bone strength. The breaking strength was evaluated using a 3-point flexure testing setup as described in Jahan et al. (2023). Subsequently, tibia samples were dried in a forced-air oven at 105°C for 24 h to determine the dry matter, followed by ashing at 600°C for 13 h in a muffle furnace (Carbolite, Sheffield, UK). The tibia ash content was determined as ash weight (g) divided by the weight of the oven-dried tibia and multiplied by 100. The tibia ash samples were then ground using pastel and mortar and the powdered samples were used to determine the mineral content (e.g. Ca and P) with portable X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (pXRF) as described by Shand and Wendler (2014).

On dissection, an excreta sample from each of the 72 birds culled above for sampling was immediately collected from lower large intestine into 50 mL containers. Containers were then placed on ice and transported to the laboratory and stored at −20°C until further analysis. Later, faecal samples underwent drying at 60°C over 3 days. Each day, a portion of the samples was randomly selected and weighed until the third day, when no additional weight change was observed, indicating that all moisture had been removed. The faecal glucocorticoid metabolites (FCGM) were extracted following the method described by Young and Hallford (2013). In brief, so as to extract FCGM, 50 mg of dried sample was weighed in a glass test tube, and 2 mL of methanol was added then mixed vigorously for 5 min using a vortex, followed by centrifugation at 2300g for 15 min at 4°C, and afterwards the test tube was kept at −80°C for 15 min. Then the methanol supernatant was cautiously transferred to a separate glass tube (12 mm × 75 mm). The solvent was then evaporated at 60°C by using an air stream until completely dry. The desiccated extracts were preserved at −20°C until further analysis. Reconstitution of the dried extracts was performed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, 0.01 M, 1 mL) with 0.1% gelatin, followed by 5 min of vigorous vertexing. The FCGM concentrations were quantified in duplicate by using the Corticosterone Double Antibody RIA Kit (# 0712010-CF, MP Biomedicals Australia, Seven Hills, NSW, Australia) as instructed by Barrett and Blache (2019). All samples underwent simultaneous processing in a single assay, exhibiting a coefficient of variation lower than 7%.

Statistical analyses

Data were analysed using JMP® 17.2.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA), with the significance level set at 0.05, and effects with P-values between 0.05 and 0.10 were interpreted as approaching statistical significance. Data were compiled per individual hen separately for each treatment and observation. The studentised residuals were visually checked to confirm homoscedasticity. At pen-level behavioural observation, the individual pen was considered as the experimental unit and hen behavioural time budgets were calculated as proportions of observed behaviours within each pen. Rarely observed behaviours, including leg stretching, lying, body shaking, wing flapping, and wing leg stretching were combined into a single category ‘other comfort behaviour’ for analysis.

Proportional data were logit-transformed after adding a constant value of ‘0.0001’ to include a considerable number of ‘0’ values in the analysis for some of the behavioural observations. A general linear mixed model (GLMM) was applied for each behaviour, with treatment, time of day, and their interaction as fixed effects and pen ID as a random effect. However, the effect of time of day was presented within each dietary treatment rather than as a main effect across both treatments, providing a clearer interpretation of time-of-day influences under each dietary condition. When significant differences between treatments were identified, a Student’s t-test was applied to the least-squares means, with raw values presented in the tables. Hen range use and time spent on the range data were also analysed using GLMM. For censored data, such as TI duration, latency to approach, and latency to peck the novel object, Kaplan–Meier estimates with a log-rank tests were used to assess treatment differences. Count data, including TI induction attempts, hens approaching the novel object, and hens pecking the novel object, were square-root transformed to approach normality and analysed using GLMM, with hen ID as a random effect and treatment as a fixed effect. Ordinal logistic regressions (chi-squared) were used to analyse external health and welfare scores, including feather coverage (neck, breast, back, wings, tail, and belly), body condition, and keel scores, with treatment as the fixed effect. However, GLMM was applied to the number of comb wounds, with treatment as a fixed effect and hen and pen ID as random effects. No variation was observed in vent feather scores, as all hens exhibited good plumage coverage (score 0), and no obvious injuries or damage to beaks, head, toenail or footpads were observed across dietary treatments; therefore, these results are not presented. Bone parameters, including tibia breaking strength (Kgf) and ash content, and FCGM data were analysed using separate GLMM with treatment as a fixed effect and hen and pen ID as random effects. Student’s t-tests were applied where significant differences were present to identify differences between the treatments, with raw values presented in the tables.

Results

Climatic conditions and analysed nutrient compositions

During the study period, the climate was notably cold owing to the winter season in Armidale (NSW, Australia), characterised by relatively low temperatures and high humidity (Table 3). Moreover, when the hens had access to the outdoor range, the environment became even colder and frostier, occasionally experiencing intermittent showers (Table S1).

In control diet, the analysed CP was lower, whereas the Ca concentration was higher than the calculated values. For the AM/PM diet, the analysed nutrient contents, including CP and Ca for both AM and PM feeds, were lower than the calculated values. Nonetheless, the analysed nutrient concentrations in both the control and AM/PM diets met the formulation objectives and fulfilled the nutritional requirements of Hy-Line Brown laying hens (Table 2).

Home pen behaviour

There were no significant effects of dietary treatments and time of day and their interactions on hen behaviour of standing, ground scratching, environmental pecking, gentle pecking, walking, or comfort behaviours (all P > 0.05; Table 6). The treatments also did not affect hen perching, feeding, drinking, ground pecking, or resting behaviour (all P > 0.05; Table 6), although the time of day influenced these behaviours. Hen perching, ground pecking and resting behaviours increased in the afternoon irrespective of the diets, whereas more feeding behaviours were observed in the morning than in the afternoon (all P ≤ 0.03; Table 6). Additionally, time of day influenced hen drinking behaviour, with more birds in the AM/PM group drinking in the morning (P = 0.01), but no time-of-day effect was observed for the hens fed the control diet (P = 0.90; Table 6). There were interaction effects of feeding and time of day for preening and dust bathing behaviours (P < 0.05; Table 6). Hens fed the control diet exhibited more preening behaviour than did hens fed the AM/PM diet, which predominately occurred in the afternoon across all treatments (P = 0.03). Conversely, hens fed the AM/PM diet performed more dust bathing behaviour than did control hens, which also predominately occurred in the afternoon regardless of the dietary treatments (P = 0.03). There was a significant difference in feather pecking behaviour, indicating that hens fed the AM/PM diet engaged in feather pecking less frequently than did hens fed the control diet (P = 0.01; Table 6), although feather pecking was rarely observed in both groups (<2%), and there was no interaction with time of day (P = 0.26; Table 6). However, a large percentage of hens were not visible (~32%) during home pen-level observation because inadequate capturing of the entire pen in video recording, which is a limitation of the study in observation of pen behaviour.

| Behaviour | Fixed effects | % of hens displaying behaviour (mean ± s.e.m.) | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perching | Treatment | AM/PM | 4.92 ± 0.69 | 0.78 | ||

| Control | 4.37 ± 0.69 | |||||

| Time of day | AM/PM | Morning | 1.37 ± 0.63b | <0.0001 | ||

| Afternoon | 8.47 ± 0.63a | |||||

| Control | Morning | 1.36 ± 0.96b | <0.0001 | |||

| Afternoon | 7.38 ± 0.96a | |||||

| Treatment × Time of day | 0.67 | |||||

| Feeding | Treatment | AM/PM | 24.19 ± 1.04 | 0.79 | ||

| Control | 23.79 ± 1.04 | |||||

| Time of day | AM/PM | Morning | 28.29 ± 1.06a | <0.0001 | ||

| Afternoon | 20.09 ± 1.06b | |||||

| Control | Morning | 26.40 ± 1.30a | <0.001 | |||

| Afternoon | 21.19 ± 1.30b | |||||

| Treatment × Time of day | 0.12 | |||||

| Drinking | Treatment | AM/PM | 5.23 ± 0.48 | 0.38 | ||

| Control | 4.76 ± 0.48 | |||||

| Time of day | AM/PM | Morning | 6.10 ± 0.58a | 0.01 | ||

| Afternoon | 4.37 ± 0.58b | |||||

| Control | Morning | 5.62 ± 0.59 | 0.90 | |||

| Afternoon | 3.93 ± 0.59 | |||||

| Treatment × Time of day | 0.36 | |||||

| Standing | Treatment | AM/PM | 1.06 ± 0.22 | 0.08 | ||

| Control | 1.63 ± 0.22 | |||||

| Time of day | AM/PM | Morning | 1.39 ± 0.24 | 0.09 | ||

| Afternoon | 0.72 ± 0.24 | |||||

| Control | Morning | 2.07 ± 0.37 | 0.09 | |||

| Afternoon | 1.20 ± 0.37 | |||||

| Treatment × Time of day | 0.97 | |||||

| Preening | Treatment | AM/PM | 9.73 ± 1.64 | 0.88 | ||

| Control | 10.42 ± 1.64 | |||||

| Time of day | AM/PM | Morning | 8.55 ± 1.54 | 0.14 | ||

| Afternoon | 10.91 ± 1.54 | |||||

| Control | Morning | 7.32 ± 1.94b | <0.0001 | |||

| Afternoon | 13.52 ± 1.94a | |||||

| Treatment × Time of day | 0.03 | |||||

| Ground pecking | Treatment | AM/PM | 9.93 ± 0.51 | 0.31 | ||

| Control | 8.76 ± 0.51 | |||||

| Time of day | AM/PM | Morning | 7.77 ± 0.75b | <0.01 | ||

| Afternoon | 12.08 ± 0.75a | |||||

| Control | Morning | 7.75 ± 0.65b | 0.03 | |||

| Afternoon | 9.77 ± 0.65a | |||||

| Treatment × Time of day | 0.19 | |||||

| Ground scratching | Treatment | AM/PM | 0.83 ± 0.15 | 0.17 | ||

| Control | 0.97 ± 0.15 | |||||

| Time of day | AM/PM | Morning | 0.37 ± 0.25 | 0.11 | ||

| Afternoon | 1.28 ± 0.25 | |||||

| Control | Morning | 0.57 ± 0.20 | 0.08 | |||

| Afternoon | 1.37 ± 0.20 | |||||

| Treatment × Time of day | 0.97 | |||||

| Environmental pecking | Treatment | AM/PM | 3.15 ± 0.35 | 0.41 | ||

| Control | 2.62 ± 0.35 | |||||

| Time of day | AM/PM | Morning | 2.45 ± 0.53 | 0.64 | ||

| Afternoon | 3.85 ± 0.53 | |||||

| Control | Morning | 2.03 ± 0.33 | 0.09 | |||

| Afternoon | 3.23 ± 0.33 | |||||

| Treatment × Time of day | 0.27 | |||||

| Resting | Treatment | AM/PM | 1.07 ± 0.71 | 0.21 | ||

| Control | 3.06 ± 0.71 | |||||

| Time of day | AM/PM | Morning | 0.57 ± 0.44b | <0.001 | ||

| Afternoon | 1.57 ± 0.44a | |||||

| Control | Morning | 0.97 ± 1.05b | <0.001 | |||

| Afternoon | 5.16 ± 1.05a | |||||

| Treatment × Time of day | 0.50 | |||||

| Gentle pecking | Treatment | AM/PM | 0.60 ± 0.14 | 0.13 | ||

| Control | 0.27 ± 0.14 | |||||

| Time of day | AM/PM | Morning | 0.55 ± 0.21 | 0.95 | ||

| Afternoon | 0.65 ± 0.21 | |||||

| Control | Morning | 0.23 ± 0.15 | 0.45 | |||

| Afternoon | 0.32 ± 0.15 | |||||

| Treatment × Time of day | 0.66 | |||||

| Feather pecking | Treatment | AM/PM | 0.39 ± 0.15b | 0.01 | ||

| Control | 1.15 ± 0.15a | |||||

| Time of day | AM/PM | Morning | 0.52 ± 0.15 | 0.37 | ||

| Afternoon | 0.26 ± 0.15 | |||||

| Control | Morning | 1.08 ± 0.27 | 0.48 | |||

| Afternoon | 1.22 ± 0.27 | |||||

| Treatment × Time of day | 0.26 | |||||

| Dust bathing | Treatment | AM/PM | 2.91 ± 0.48 | 0.67 | ||

| Control | 1.97 ± 0.48 | |||||

| Time of day | AM/PM | Morning | 0.04 ± 0.60b | <0.0001 | ||

| Afternoon | 5.77 ± 0.60a | |||||

| Control | Morning | 0.17 ± 0.60b | <0.0001 | |||

| Afternoon | 3.77 ± 0.60a | |||||

| Treatment × Time of day | 0.03 | |||||

| Walking | Treatment | AM/PM | 2.15 ± 0.41 | 0.39 | ||

| Control | 2.88 ± 0.41 | |||||

| Time of day | AM/PM | Morning | 2.35 ± 0.40 | 0.91 | ||

| Afternoon | 1.98 ± 0.40 | |||||

| Control | Morning | 2.63 ± 0.56 | 0.83 | |||

| Afternoon | 3.13 ± 0.56 | |||||

| Treatment × Time of day | 0.81 | |||||

| Other comfort behaviour A | Treatment | AM/PM | 0.90 ± 0.13 | 0.56 | ||

| Control | 0.95 ± 0.13 | |||||

| Time of day | AM/PM | Morning | 0.96 ± 0.19 | 0.91 | ||

| Afternoon | 0.83 ± 0.19 | |||||

| Control | Morning | 1.02 ± 0.15 | 0.67 | |||

| Afternoon | 0.87 ± 0.15 | |||||

| Treatment × Time of day | 0.70 | |||||

The means ± s.e.m. are presented for each variable. Raw data are presented with analyses conducted on transformed data, with the significance level set at 0.05. Dissimilar letters indicate significant post hoc differences between the treatment groups (at P = 0.05).

Outdoor ranging behaviour

All hens accessed the range every day when the pop-holes were opened, regardless of the treatments. However, a notable distinction in the effects of dietary treatments on hens’ range use was observed over the 2 weeks ranging behaviour from 46 to 47 WOA (P < 0.05). On average, hens fed the AM/PM diet spent longer on the outdoor range than did the control group (2.85 vs 2.47 h/day; P < 0.001). The interaction effects of treatment and day indicated an increase in hens’ ranging behaviour over time, with AM/PM hens consistently spending more time on the range than did the control hens (Fig. 2). A sharp decline in hen range use on Day 8 occurred because of heavy showers from midnight until the morning (Table S1).

Fearfulness

The effects of AM/PM diet on hen fearfulness are shown in Fig. 3 and Table 7. The Kaplan–Meier estimates did not show significant differences between the treatment groups for the duration of TI at 51 WOA (P = 0.97; Fig. 3a) or the latency to approach the novel object at 52 WOA (P = 0.62; Fig. 3b). However, there was an effect approaching statistical significance for hens from the AM/PM group to peck the novel object faster than did control hens at 52 WOA (P = 0.07; Fig. 3c). The number of attempts required to induce TI did not differ significantly between the groups at 51 WOA (P = 0.73; Table 7). Similarly, no significant differences were observed between AM/PM and control hens for the number of hens approaching or pecking at the novel object during NOT at 52 WOA (P = 0.86 and 0.26, respectively; Table 7).

Survival curve of latencies in TI and NOT: (a) the duration to induce TI; (b) the latency to approach the novel object; and (c) the latency to peck the novel object.

| Treatment | TI (mean ± s.e.m.) | NOT (mean ± s.e.m.) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attempts | Number of hens approached | Number of hens peck | ||

| AM/PM | 1.59 ± 0.13 | 25.78 ± 2.44 | 11.11 ± 1.21 | |

| Control | 1.67 ± 0.13 | 25.67 ± 2.44 | 9.00 ± 1.21 | |

| P-value | 0.73 | 0.86 | 0.26 | |

The means ± s.e.m. are presented for each variable. Raw data are presented, with analyses conducted on transformed data, with the significance level set at 0.05.

External health and welfare indicators

The effects of dietary treatments on feather score at 52 WOA are presented in Table 8. There were no effects of the dietary treatments on plumage coverage across various body regions including the neck, breast, back, wing, tail, and belly (all P > 0.05; Table 8). Moreover, there were no discernible differences in keel and body condition scores attributable to the dietary interventions (both P > 0.05; Tables 9, 10). Additionally, the occurrence of comb wounds did not significantly vary between hens offered the AM/PM and control diets (P = 0.16; Table 11).

| Parameter | Treatment | Feather score % (n) | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 – none | 1 – slight/ moderately affected | 2 – severely affected | ||||

| Neck | AM/PM | 87.22(157) | 11.67(21) | 1.11(2) | 0.29 | |

| Control | 92.22(166) | 7.22(13) | 0.56(1) | |||

| Breast | AM/PM | 85(153) | 14.44(26) | 0.56(1) | 0.40 | |

| Control | 87.22(157) | 11.11(20) | 1.67(3) | |||

| Back | AM/PM | 92.22(166) | 6.67(12) | 1.11(2) | 0.65 | |

| Control | 94.44(170) | 4.44(8) | 1.11(2) | |||

| Wings | AM/PM | 98.33(177) | 1.11(2) | 0.56(1) | 0.55 | |

| Control | 98.33(177) | 1.67(3) | 0(0) | |||

| Tail | AM/PM | 92.78(166) | 7.22(13) | 0(0) | 0.84 | |

| Control | 92.22(166) | 7.78(14) | 0(0) | |||

| Belly | AM/PM | 95(171) | 5(9) | 0(0) | 0.37 | |

| Control | 93.89(169) | 5(9) | 1.11(2) | |||

The mean percentage of hens observed in each indicator category is presented for each variable. Raw data are presented with analyses, with significance level set at 0.05.

Number of hens is shown in parentheses in subscript.

| Treatment | Body condition | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 – fatty | 1 – normal/good | 2 – shiny | |||

| AM/PM | 10(18) | 87.22(157) | 2.78(5) | 0.16 | |

| Control | 15.56(28) | 85.28(150) | 1.94(2) | ||

The mean percentage of hens observed in each indicator category is presented for each variable. Raw data are presented with analyses, with significance level set at 0.05.

Number of hens is shown in parentheses in subscript.

| Treatment | Keel | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 – normal | 1 – hairline fracture | 2 – break | |||

| AM/PM | 33.33(12) | 66.67(24) | 0(0) | 0.61 | |

| Control | 27.78(10) | 72.22(26) | 0(0) | ||

The mean percentage of hens observed in each indicator category is presented for each variable. Raw data are presented with analyses, with significance level set at 0.05.

Number of hens is shown in parentheses in subscript.

| Treatment | Comb wound | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| mean ± s.e.m. | |||

| AM/PM | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.16 | |

| Control | 0.03 ± 0.01 |

The mean percentage of hens observed in each indicator category is presented for each variable. Raw data are presented with analyses, with significance level set at 0.05.

Tibia quality

The results of tibia parameters at 53 WOA are presented in Table 12. The length, diameter, and Seedor index of the tibias did not differ significantly between the treatment groups (all P > 0.05). However, the tibia ash content was higher in hens fed the AM/PM diet than in those fed the control diet (P = 0.03; Table 12). Nevertheless, AM/PM feeding did not affect the tibia Ca and P contents (P > 0.05). However, the tibia breaking strength was higher in AM/PM hens than in the control hens (P = 0.04; Table 12).

| Variable | Treatment (mean ± s.e.m.) | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AM/PM | Control | |||

| Length (mm) | 123.62 ± 0.56 | 124.60 ± 0.57 | 0.22 | |

| Diameter (mm) | 8.67 ± 0.07 | 8.82 ± 0.07 | 0.13 | |

| Seedor index (mg/mm) | 0.07 ± 0.0 | 0.07 ± 0.0 | 0.62 | |

| Bone breaking strength (Kgf) | 196.3 ± 9.44a | 168.3 ± 9.58b | 0.04 | |

| Ash (%) | 43.29 ± 0.48a | 41.64 ± 0.49b | 0.03 | |

| Ca (%) | 36.54 ± 12.19 | 36.79 ± 12.35 | 0.16 | |

| P (%) | 11.72 ± 5.38 | 11.65 ± 5.43 | 0.41 | |

Means within a row followed by different letters are significantly different at the 5% level of significance.

Discussion

This study aimed to examine whether the AM/PM feeding strategy would have positive impacts on free-range hen behaviours, including their ranging patterns in the outdoor range, and feather pecking, fearfulness, or stress compared with hens fed a conventional diet. The findings showed some positive impacts for the AM/PM feeding regimen relative to the conventional diet, indicating that AM/PM feeding has the potential to decrease feather pecking behaviours in hens, enhance ranging activity, and improve bone health; however, the effects were small, which may reflect the timing of assessments or stage of life that the birds were fed the diets. Free-range hens typically gain advantages from having access to a variety of nutritional resources outdoors. Supplying a well-balanced diet in accordance with an animal’s natural daily activity patterns and timing of physiological requirements can further support meeting the birds’ nutritional needs and improve behavioural repertoires and welfare (MacLeod 2013; Bryden et al. 2021).

As part of a larger project, the earlier study found that AM/PM feeding improves egg mass, feed efficiency, and yolk colour, while reducing feed costs, making it economically beneficial despite lower digestible energy and nitrogen due to reduce enzymatic activity by excess calcium (Ca) in the PM diet (Jahan et al. 2024). In this study, hens subjected to AM/PM feeding exhibited less feather pecking, indicating that the AM/PM feeding strategy can hold the potential to reduce feather pecking behaviours in laying hens. However, the number of hens that exhibited feather pecking behaviour was very low (<2%), and the study did not observe noteworthy differences in feather coverage or comb injuries regardless of experimental diets, suggesting that severe feather pecking was not an issue in any of the pens. The relationship between feeding time and feather pecking is intricate and multifactorial, often influenced by variables such as the specific dietary composition, environmental conditions, and individual characteristics of the birds (Van Krimpen et al. 2005; Bonnefous et al. 2022).

The timing of the day showed a notable impact on hen behaviours, with increased expression of behavioural repertoires being observed in the afternoon, whereas feeding behaviour was more frequent in the morning in both treatment groups. An escalation in feeding activity in the morning may support their natural diurnal behaviour, seeking food when visibility is optimal. This time allows them to replenish energy reserves after resting overnight, supporting their metabolic needs for activities such as egg-laying (Savory 1980; Choi et al. 2004). The current study highlighted that the interplay between feeding and time of day significantly influenced preening and dust bathing behaviours. Control hens exhibited more preening in the afternoon, whereas hens receiving either diet favoured afternoon dust bathing. van Emous (2023) observed that broiler breeder hens fed a conventional diet tended to engage in longer periods of dust bathing than did the AM/PM fed hens, whereas in their prior experiment, there were no discernible distinctions in dust bathing behaviour between the feeding strategies (van Emous and Mens 2021). Therefore, although both preening and dust bathing are indicative of desirable behaviour (Papageorgiou et al. 2023), the underlying causes of the dietary effects on these behaviours are yet to be examined. Although both behaviours have shown inconsistencies throughout the day in previous studies, they could be influenced by various external factors such as environmental conditions, litter quality, social facilitation, as well as internal factors such as circadian rhythm (Vestergaard 1982; Sandilands 2001; Olsson et al. 2002).

There were some effects of AM/PM feeding on the hens’ range use. This may be aligned with that a balanced diet, rich in protein and energy, can positively affect hens’ range use (Okitoi et al. 2009). Such dietary formulations could be in harmony with the hens’ instinctive foraging behaviours, mitigating monotony and promoting increased and energetic exploration of the outdoor range (Miao et al. 2005). In this study, the AM diet contained sufficient protein and energy levels that may influence the hens’ motivation to explore and engage in natural behaviours outdoors. Future studies on hen behavioural repertoire on the outdoor range may help confirm this. Additionally, hens fed the AM/PM diets may have been looking for specific nutrients in the range area, which can influence their willingness to utilise the outdoor environment (Okitoi et al. 2007). The results of the current study showed that feeding the AM/PM diet increased tibia ash content and breaking strength compared with the control hens. This finding is supported by Molnár et al. (2018b) who reported increased bone ash content in hens offered AM/PM diets, potentially being associated with improved Ca uptake and metabolism through the PM diet compared with conventional feeding systems. A comprehensive study throughout the entire laying cycle may provide more conclusive results and confirm the benefits.

It was predicted that aligning nutritional sufficiency with hens’ physiological needs would create a predictable environment conducive to a sense of security and stability, and could reduce the level of stress and fearfulness in birds (Rodenburg et al. 2010; Shcherbatov et al. 2021). Although the current study did not demonstrate a significant effect during the TI and NOT assessments, there was an intriguing tendency observed among AM/PM hens, as they exhibited a faster pecking response to the novel object during NOT in the home pen, indicating a potential increase in hens’ curiosity and motivation to explore their surroundings as well as range use (Kolakshyapati et al. 2020; Taylor et al. 2023). However, this effect was very small (all hens pecked the novel object but there was a < 20 s lag by the control birds to do so). The novel object was wrapped in multicoloured adhesive scotch tape, so it was uncertain whether some of the colours might not be new to the hens, potentially causing them to approach more quickly. To substantiate these observations, repeated measurements at various age points by using different novel objects are imperative (Hüttner et al. 2023).

The current study showed that the faecal glucocorticoid concentrations, a marker of cumulative physiological stress responses, were not significantly different between the treatment groups, indicating that AM/PM feeding did not potentially mitigate stress responses or influence stress. This finding was reinforced by the comprehensive external health and welfare assessment of the hens, which showed no discernible adverse effects of dietary treatments on overall plumage coverage and health conditions. Nevertheless, an observation emerged regarding the AM/PM hens displaying a drift of shining body condition appearance. This phenomenon may be associated with their higher access to the outdoor range, a factor that may contribute to a reduction in both body fat and muscle (Bari et al. 2020), but warrants further investigation.

The study had some limitations. For example, the hens used in this study were previously involved in determining AM and PM nutrient compositions, so there may have been some carryover effect, although these effects were minimised through random distribution and acclimation. Additionally, the birds were already at an age when their bones were in good condition at the start of the study, which may influence the skeletal health outcomes. Exploratory behaviours were solely assessed within their home pens, with restricted access to outside. A more thorough observation of hen behaviours during outdoor ranging could yield more definitive findings regarding feeding effects. A large percentage of hens were not visible (~32%) during home pen observation because of camera angles. Hen behaviour and welfare assessments were taken once; however, repeated measurement can yield more robust findings. Additionally, ranging behaviours were monitored for only a 2-week period because of technical challenges; continuous observation throughout the ranging period could provide a more accurate assessment. Human interaction during manual swapping of feed and egg collection may have some effect on behavioural observation as well (Hemsworth and Coleman 2010). So, in future studies, an automated mechanism for twice-daily feed changes may be useful.

Conclusions

The AM/PM feeding has shown some positive benefits for free-range laying hens. Although it has no substantial effect on hen behaviours, it shows potential to improve hen range use. Moreover, the compelling evidence of increased tibia ash content and breaking strength with AM/PM feeding underscores its potential to enhance skeletal health. Overall, the study’s comprehensive outcomes underscore the options of AM/PM feeding for practical implications without compromising the welfare of free-range hens through considerate feeding management strategies; however, further investigation is required for the full laying cycle to confirm these benefits.

Data availability

The data cannot be publicly accessed due to privacy considerations. However, upon a reasonable request directed to the corresponding author, the research data supporting this study will be provided.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. The funding entity did not participate in data collection, analysis, or interpretation. Feedback on the trial design and the final draft of the publication was provided by an industry committee arranged by the funding organisation.

Declaration of funding

The funding for this research was supported by Poultry Hub Australia and Australian Eggs Pty Ltd (Grant number: 21-306). A. A. J. received the University of New England International Postgraduate Research Award (UNE IPRA) for her doctoral research in this project.

Author contributions

Conceptualisation, A. F. Moss and P. S. Taylor; methodology, A. F. Moss, T. H. Dao, P. S. Taylor, A. A. Jahan and M. S. Rana; software, A. F. Moss, A. A. Jahan and T. H. Dao; validation, A. F. Moss, T. H. Dao, A. A. Jahan and P. S. Taylor; formal analysis, A. A. Jahan, A. F. Moss; T. H. Dao and M. S. Rana; investigation, A. A. Jahan, A. F. Moss and T. H. Dao; resources, A. F. Moss and T. M. Crowley; data curation, A. A. Jahan, A. F. Moss, T. H. Dao, M. S. Rana; writing – original draft preparation, A. A. Jahan; writing – review and editing, A. F. Moss., A. A. Jahan T. H. Dao, M. S. Rana, P. S. Taylor; and T. M. Crowley; visualisation, A. A. Jahan and M. S. Rana; supervision, T. M. Crowley, A. F. Moss and T. H. Dao; project administration, A. F. Moss, T. M. Crowley and T. H. Dao; funding acquisition, A. F. Moss, P. S. Taylor and T. M. Crowley. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the paper.

Acknowledgements

We express our appreciation to the PhD graduate students, particularly Nasima Akter and Sukirno, as well as Staff at the Centre for Animal Research and Teaching, for their indispensable assistance during the experimental procedure and sample acquisition. We are grateful to UNE technicians Craig Johnson, James Turnell, and Shuyu Song for their assistance with laboratory analyses. We also thank Dominique Blache from the University of Western Australia for their assistance with faecal glucocorticoid metabolite analysis. Furthermore, we acknowledge the guidance and support extended by our industry advisors, including David Cadogan, Nishchal Sharma, Emma Bradbury, and Peter Chrystal, throughout the duration of this project.

References

Abd El-Razek MM, Makled MN, Galal AE, El-kelawy M (2020) Effect of split feeding system on egg production and egg quality of dandarawi layers. Egyptian Poultry Science Journal 40, 359-371.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Akinyemi F, Adewole D (2021) Environmental stress in chickens and the potential effectiveness of dietary vitamin supplementation. Frontiers in Animal Science 2, 775311.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Akter N, Dao TH, Crowley TM, Moss AF (2025) Optimization of split feeding strategy for laying hens through a response surface model. Animals 15(5), 750.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Bari MS, Laurenson YCSM, Cohen-Barnhouse AM, Walkden-Brown SW, Campbell DLM (2020) Effects of outdoor ranging on external and internal health parameters for hens from different rearing enrichments. PeerJ 8, e8720.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Barrett LA, Blache D (2019) Development of a behavioural demand method for use with Pekin ducks. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 214, 42-49.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Bonnefous C, Collin A, Guilloteau LA, Guesdon V, Filliat C, Réhault-Godbert S, Rodenburg TB, Tuyttens FAM, Warin L, Steenfeldt S, Baldinger L, Re M, Ponzio R, Zuliani A, Venezia P, Väre M, Parrott P, Walley K, Niemi JK, Leterrier C (2022) Welfare issues and potential solutions for laying hens in free range and organic production systems: a review based on literature and interviews. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 9, 1148.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Box GEP, Behnken DW (1960) Some new three level designs for the study of quantitative variables. Technometrics 2, 455-475.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Bryden WL, Li X, Ruhnke I, Zhang D, Shini S (2021) Nutrition, feeding and laying hen welfare. Animal Production Science 61, 893-914.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Choi JH, Namkung H, Paik IK (2004) Feed consumption pattern of laying hens in relation to time of oviposition. Asian-Australasian Journal of Animal Sciences 17, 371-373.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

De los Mozos J, Gutierrez del Alamo A, Gerwe Tv, Sacranie A, Perez de Ayala P (2012) Oviposition feeding compared to normal feeding: effect on performance and egg shell quality. In ‘Proceedings of the 23rd Annual Australian Poultry Science Symposium’, 19–22 February 2012, Sydney, NSW, Australia. pp. 180–183. (Poultry Research Foundation)

De los Mozos J, Sacranie A, Van Gerwe T (2014) Performance and eggshell quality in laying hens fed two diets through the day with different levels of calcium or phos-phorous. In ‘Proceedings of the 25th Annual Australian Poultry Science Symposium’, 16–19 February 2014, Sydney, NSW, Australia. pp. 148–151. (Poultry Research Foundation)

Dixon LM, Dunn IC, Brocklehurst S, Baker L, Boswell T, Caughey SD, Reid A, Sandilands V, Wilson PW, D’Eath RB (2022) The effects of feed restriction, time of day, and time since feeding on behavioral and physiological indicators of hunger in broiler breeder hens. Poultry Science 101, 101838.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

El-Lethey H, Aerni V, Jungi TW, Wechsler B (2000) Stress and feather pecking in laying hens in relation to housing conditions. British Poultry Science 41, 22-28.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Forkman B, Boissy A, Meunier-Salaün M-C, Canali E, Jones RB (2007) A critical review of fear tests used on cattle, pigs, sheep, poultry and horses. Physiology & Behavior 92, 340-374.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Heerkens JLT, Delezie E, Rodenburg TB, Kempen I, Zoons J, Ampe B, Tuyttens FAM (2016) Risk factors associated with keel bone and foot pad disorders in laying hens housed in aviary systems. Poultry Science 95, 482-488.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Hemsworth PH, Coleman G (2010) Managing poultry: human–bird interactions and their implications. In ‘The welfare of domestic fowl and other captive birds’. (Eds I Duncan, P Hawkins) pp. 219–235. (Springer) 10.1007/978-90-481-3650-6_9

Hiramoto K, Muramatsu T, Okumura J (1990) Protein synthesis in tissues and in the whole body of laying hens during egg formation. Poultry Science 69, 264-269.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Hüttner J, Clauß A, Klambeck L, Andersson R, Kemper N, Spindler B (2023) Association with different housing and welfare parameters on results of a novel object test in laying hen flocks on farm. Animals 13, 2207.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Jahan AA, Dao TH, Akter N, Swick RA, Morgan NK, Crowley TM, Moss AF (2023) The order of limiting amino acids in a wheat–sorghum-based reduced-protein diet for laying hens. Applied Sciences 13, 12934.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Jahan AA, Dao TH, Morgan NK, Crowley TM, Moss AF (2024) Effects of AM/PM diets on laying performance, egg quality, and nutrient utilisation in free-range laying hens. Applied Sciences 14, 2163.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Jones RB (1986) The tonic immobility reaction of the domestic fowl: a review. World’s Poultry Science Journal 42, 82-96.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Kolakshyapati M, Taylor PS, Hamlin A, Sibanda TZ, Vilela JdS, Ruhnke I (2020) Frequent visits to an outdoor range and lower areas of an aviary system is related to curiosity in commercial free-range laying hens. Animals 10, 1706.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Lee K, Ohh Y (2002) Effects of nutrient levels and feeding regimen of am and pm diets on laying hen performances and feed cost. Korean Journal of Poultry Science 29, 195-204.

| Google Scholar |

MacLeod M (2013) Nutrition-related opportunities and challenges of alternative poultry production systems. Lohmann Information 48, 23-28.

| Google Scholar |

Mens AJW, Van Krimpen MM, Kwakkel RP (2020) Nutritional approaches to reduce or prevent feather pecking in laying hens: any potential to intervene during rearing? World’s Poultry Science Journal 76, 591-610.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Miao ZH, Glatz PC, Ru YJ (2005) Free-range poultry production – a review. Asian-Australasian Journal of Animal Sciences 18, 113-132.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Molnár A, Hamelin C, Delezie E, Nys Y (2018a) Sequential and choice feeding in laying hens: adapting nutrient supply to requirements during the egg formation cycle. World’s Poultry Science Journal 74, 199-210.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Molnár A, Kempen I, Sleeckx N, Zoons J, Maertens L, Ampe B, Buyse J, Delezie E (2018b) Effects of split feeding on performance, egg quality, and bone strength in brown laying hens in aviary system. Journal of Applied Poultry Research 27, 401-415.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Moss AF, Dao TH, Crowley TM, Wilkinson SJ (2023) Interactions of diet and circadian rhythm to achieve precision nutrition of poultry. Animal Production Science 63, 1926-1932.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Nasr MAF, Murrell J, Nicol CJ (2013) The effect of keel fractures on egg production, feed and water consumption in individual laying hens. British Poultry Science 54, 165-170.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Okitoi LO, Kabuage LW, Muinga RW, Badamana MS (2007) The potential of morning and afternoon supplementation of scavenging chickens on diets with varying energy and protein levels. Livestock Research for Rural Development 19, 2-3.

| Google Scholar |

Okitoi LO, Kabuage LW, Muinga RW, Badamana MS (2009) The performance response of scavenging chickens to nutrient intake from scavengeable resources and from supplementation with energy and protein. Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organization 21, 10.

| Google Scholar |

Olsson IAS, Duncan IJH, Keeling LJ, Widowski TM (2002) How important is social facilitation for dustbathing in laying hens? Applied Animal Behaviour Science 79, 285-297.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Papageorgiou M, Goliomytis M, Tzamaloukas O, Miltiadou D, Simitzis P (2023) Positive welfare indicators and their association with sustainable management systems in poultry. Sustainability 15, 10890.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Penz AM, Jr, Jensen LS (1991) Influence of protein concentration, amino acid supplementation, and daily time of access to high- or low-protein diets on egg weight and components in laying hens. Poultry Science 70, 2460-2466.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Pottgüter R (2016) Feeding laying hens to 100 weeks of age. Lohmann Information 50, 18-21.

| Google Scholar |

Rana MS, Lee C, Walkden-Brown SW, Campbell DLM (2024) Effects of ultraviolet light supplementation on hen behaviour and welfare during early lay. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 273, 106235.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Richards GJ, Wilkins LJ, Knowles TG, Booth F, Toscano MJ, Nicol CJ, Brown SN (2012) Pop hole use by hens with different keel fracture status monitored throughout the laying period. Veterinary Record 170, 494.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Rodenburg TB, de Haas EN, Nielsen BL, Buitenhuis AJ(Bart) (2010) Fearfulness and feather damage in laying hens divergently selected for high and low feather pecking. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 128, 91-96.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Savory CJ (1980) Diurnal feeding patterns in domestic fowls: a review. Applied Animal Ethology 6, 71-82.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Schwarzer A, Rauch E, Bergmann S, Kirchner A, Lenz A, Hammes A, Erhard M, Reese S, Louton H (2022) Risk factors for the occurrence of feather pecking in non-beak-trimmed pullets and laying hens on commercial farms. Applied Sciences 12, 9699.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Seedor JG, Quartuccio HA, Thompson DD (1991) The bisphosphonate alendronate (MK-217) inhibits bone loss due to ovariectomy in rats. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research 6, 339-346.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Shand CA, Wendler R (2014) Portable X-ray fluorescence analysis of mineral and organic soils and the influence of organic matter. Journal of Geochemical Exploration 143, 31-42.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Shcherbatov V, Smirnova L, Osepchuk D, Petrenko Y (2021) Influence of circadian rhythms on motor activity of chickens. In ‘Fundamental and applied scientific research in the development of agriculture in the far east (AFE-2021). AFE 2021. Vol. 354. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems’. (Eds A Muratov, S Ignateva) pp. 340–349. (Springer: Cham) 10.1007/978-3-030-91405-9_37

Sirovnik J, Würbel H, Toscano MJ (2018) Feeder space affects access to the feeder, aggression, and feed conversion in laying hens in an aviary system. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 198, 75-82.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Taylor PS, Campbell DLM, Jurecky E, Devine N, Lee C, Hemsworth PH (2023) Novelty during rearing increased inquisitive exploration but was not related to early ranging behavior of laying hens. Frontiers in Animal Science 4, 1128792.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Umar Faruk M, Bouvarel I, Même N, Rideau N, Roffidal L, Tukur HM, Bastianelli D, Nys Y, Lescoat P (2010) Sequential feeding using whole wheat and a separate protein–mineral concentrate improved feed efficiency in laying hens. Poultry Science 89, 785-796.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

van Emous RA (2023) Effects of feeding strategies during lay on broiler breeder production performance, eggshell quality, incubation traits, and behavior. Poultry Science 102, 102630.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

van Emous RA, Mens AJW (2021) Effects of twice a day feeding and split feeding during lay on broiler breeder production performance, eggshell quality, incubation traits, and behavior. Poultry Science 100, 101419.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Van Krimpen MM, Kwakkel RP, Reuvekamp BFJ, Van Der Peet-Schwering CMC, Den Hartog LA, Verstegen MWA (2005) Impact of feeding management on feather pecking in laying hens. World’s Poultry Science Journal 61, 663-686.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Vestergaard K (1982) Dust-bathing in the domestic fowl – diurnal rhythm and dust deprivation. Applied Animal Ethology 8, 487-495.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Wei H, Bi Y, Xin H, Pan L, Liu R, Li X, Li J, Zhang R, Bao J (2020) Keel fracture changed the behavior and reduced the welfare, production performance, and egg quality in laying hens housed individually in furnished cages. Poultry Science 99, 3334-3342.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Young AM, Hallford DM (2013) Validation of a Fecal glucocorticoid metabolite assay to assess stress in the budgerigar (Melopsittacus undulatus). Zoo Biology 32, 112-116.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |