Determinants of women small ruminant farmers’ perceptions of climate change impact in Northern Benin

Elodie Dimon A * , Youssouf Toukourou A , Janvier Egah B , Alassan Assani Seidou A , Rodrigue Vivien Cao Diogo C and Ibrahim Alkoiret Traore A

A * , Youssouf Toukourou A , Janvier Egah B , Alassan Assani Seidou A , Rodrigue Vivien Cao Diogo C and Ibrahim Alkoiret Traore A

A

B

C

Abstract

The effectiveness of adaptation strategies employed by women small ruminant farmers to combat climate change depends on the accuracy of their perceptions. However, these women’s perceptions are not well understood and are seldom considered in climate change adaptation policies.

The aim of this study is to analyze the perceptions of women herders of small ruminants on the effects of climate change in four communes in northern Benin.

A total of 120 women farmers were purposefully selected and surveyed. Sociodemographic parameters and the perception rates of these farmers were analyzed using a multinomial logit model to understand the determinants of climate change perception.

All surveyed women perceived the effects of climate change, such as delayed rains (73%), early cessation of rains (70%), floods (87.5%), irregular rainfall (62.5%), poor spatial distribution of rains (98%), increased heat (95%), reduced coolness (61.17%), increased strong winds (81%) and wind direction instability (64%) over the past 20 years. Age, education level, farming experience, family size, extension contact, the number of sheep and the number of goats were factors that contributed to evaluating these women’s perceptions of climate change.

In conclusion, climate change is making livestock farming highly vulnerable. It leads to a scarcity of pastoral resources and a deterioration in animal health. This study recommends promoting training actions for women pastoralists, so that they could be better prepared for preventing and coping with climatic disasters.

Future research should compare the differences in adaptation strategies implemented by men and women herders who are better prepared to prevent and cope with climate-related disasters.

Keywords: Benin, climate change perception, small ruminant farmers, women.

Introduction

Climate change is a global phenomenon causing the warming of the Earth’s surfaces and seas, and has become a crisis for humanity (Naqvi and Sejian 2011; Herrero et al. 2013; Feleke et al. 2016). The increasing concentration of greenhouse gases raises the average temperature, alters precipitation and increases the frequency of certain extreme events worldwide (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) 2019). The west African region is threatened by numerous natural disasters. In recent decades, there has been a significant increase in floods, droughts, disruptions of rainy seasons and heatwaves (IPCC 2012). Climate warming is most visibly evident in extreme weather events that directly impact west African populations (Dara 2013). These extreme events threaten food security, and are exacerbated by soil erosion, deforestation and desertification – a slow and potentially irreversible process (Ozer et al. 2010; Stringer et al. 2011).

The United Nations Environment Programme has identified 19 climate change ‘hotspots’ in west Africa, including Benin (UNEP 2011). Negative effects are observed on major cereal production, as well as on livestock and drinking water availability, and the collapse of the fishing sector (Defrance et al. 2017). The impacts of climate change are strongly felt by rural populations, and more specifically, by women (Gemenne et al. 2017). The impacts of climate change are numerous and complex, affecting both usable resources and animals and their management.

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the temperature increase in sub-Saharan Africa, compared with the 20th century average, ranged from 0.3 to 1.5°C in 2017, compared with 1°C globally. On average, between 2001 and 2017, annual precipitation also decreased compared with the 20th century average by 8.5 cm in the Central African Economic and Monetary Community, 4.0 cm in the West African Economic and Monetary Union and 7.1 cm in the rest of sub-Saharan Africa, compared with 2.8 cm for the entire planet. According to Blanfort et al. (2015), livestock systems are major contributors to climate change while simultaneously being a key component of agriculture. Livestock contributes to the livelihoods of nearly 20% of the world’s population, with 800 million impoverished people directly dependent on it (Herrero et al. 2013). Sheep and goats represent approximately 56% of the world’s ruminant population (FAO 2016). Small ruminant production plays a crucial socioeconomic role on various continents, particularly in Benin. Notably, cattle populations are less resilient than small ruminants (Corniaux et al. 2012). Livestock contributes to poverty reduction, food security, and promotes capitalization and socioeconomic integration of households. Women and young people have found small ruminant farming to be the fastest and easiest way to achieve financial autonomy (Diao and Dia 2015). Women play a vital role in livestock farming, contributing to autonomy, technical expertise and animal care (Jélu and Bourgeais 2015). They also appreciate the tangible nature of this work, and the balance it offers between professional and family life. According to COP21 (2016), women are the most affected by the impacts of climate change, because they have little control over resources and are often unemployed. Poor populations are the most vulnerable to the effects of climate change. Women constitute 70% of the 1.2 billion people who earn less than US$1 a day (World Bank 2012). In developing countries, rural women work in agriculture, producing basic foodstuffs. They produce between 60 and 80% of the food in developing countries, yet 60% of the world’s hungry are women, and they earn only 10% of the total agricultural income (Association Adéquations 2009). In Benin, small ruminant farming is an activity that provides income, financial security, and non-monetary services to rural and peri-urban families. It is mainly practiced by women, for whom it represents an important means of survival. Women are more vulnerable to climate change (Leila 2014). The perception of climate change refers to how local populations understand and interpret environmental shifts. How do women small ruminant farmers in northern Benin perceive climate change, and what impacts does it have on their livelihoods?

Materials and methods

Study area

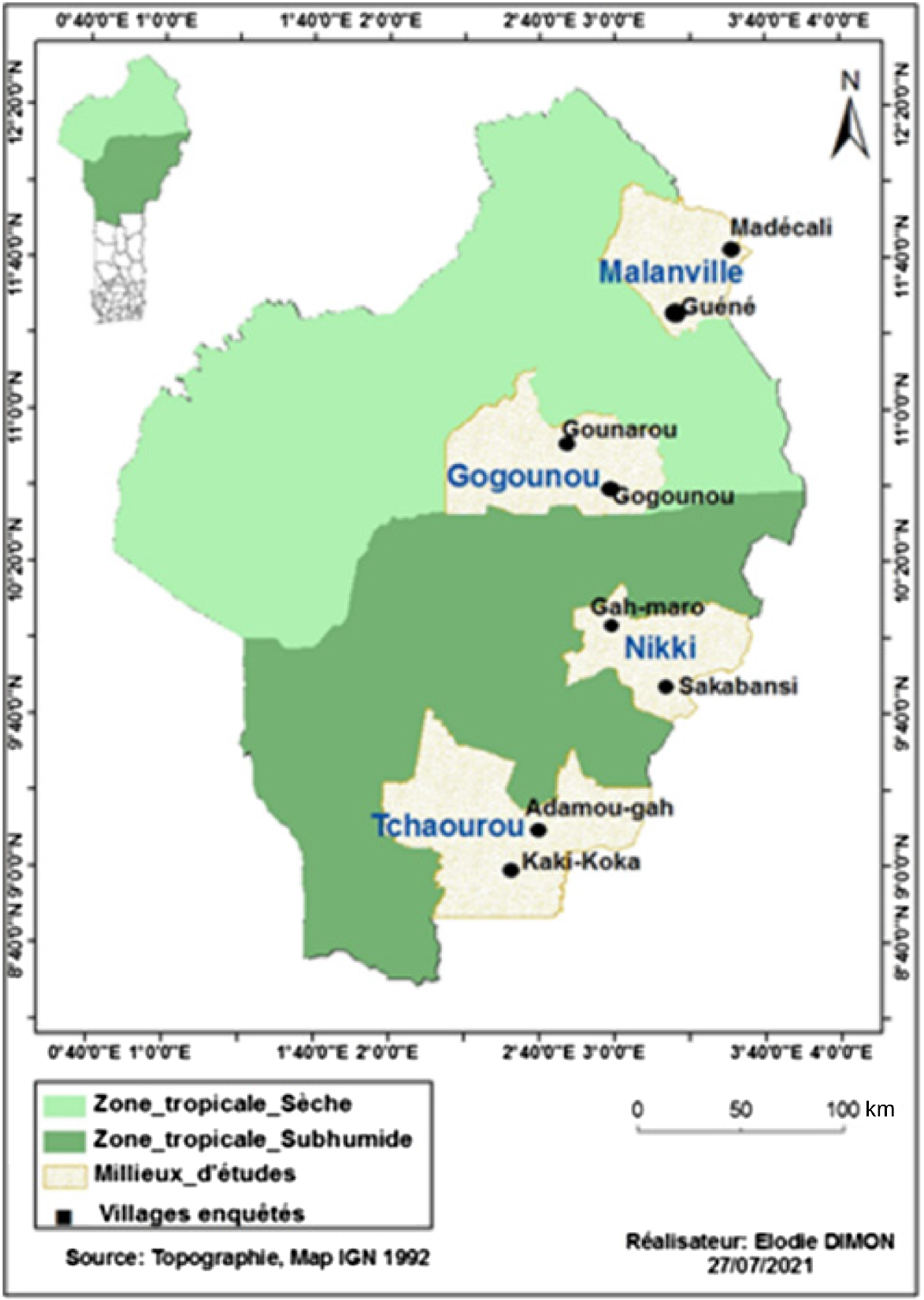

This study was conducted in northern Benin, which faces numerous climatic challenges (Vodounou and Doubogan 2016). Northern Benin has a Sudanian-Sahelian climate, and is an area with significant large and small ruminant farming. The Borgou and Alibori departments are home to approximately 67% of the national cattle herd and 33% of small ruminants (National Association of Professional Organizations of Ruminant Breeders 2014). Small ruminants are concentrated in the northern regions of Benin (Borgou, Alibori, Atacora, Donga; Hounzangbé-Adote et al. 2011). These areas are most vulnerable to rainfall deficits and high insolation (Gnanglè et al. 2011; Mehu 2011). A total of eight villages were selected for this study. They are located in the communes of Tchaourou, Nikki, Gogounou and Malanville in northern Benin. In each municipality, two villages were selected (Fig. 1). The questionnaire was developed to understand the impact of climate change on small ruminant farming systems managed by women. This questionnaire collected various data related to the sociodemographic characteristics of female farmers, the structure of small ruminant farming systems, female farmers’ perceptions of climate change, the effects of perceived climate change on the productivity and health of small ruminants, as well as on the household, and finally, the adaptation strategies implemented (Table 1).

| Communes | Villages | Vegetation | Annual precipitation (mm) | Daily temperature (°C) | Total livestock estimates (n) * (PDC, 2017) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Malanville | Madécali Guéné | ZS | 9049 | 35 | 20,562 sheep 30,138 goats | |

| Gogounou | Gounarou Gogounou center | ZS | 1051 | 28.2 | 29,057 sheep 22,826 goats | |

| Nikki | Gah-Maro Sakabansi | ZSG | 1100–1300 | 28–35 | 24,900 sheep 31,502 goats | |

| Tchaourou | Adamou-gah Kaki-koka | ZSG | 1100–1200 | 23–32 | 11,755 sheep 14,093 goats |

Source: Communal Development Plan, 2017.

The surveys were conducted by the first author and a master’s student. We were proficient in the local language of the study area, so there was no need for an interpreter. The individual interview included a total of 40 questions, comprising multiple-choice questions and forced-choice questions, followed by focus group discussions with female farmers. The responses were then coded into distinct numerical values. The objectives of the individual survey were to gather the necessary information for a thorough analysis of the research questions, whereas those of the focus group were to verify the information obtained from the individual surveys. The same approach was used by Simelton et al. (2013) and Gebreeyesus (2017).

The municipalities were selected based on data from the National Association of Professional Livestock Organizations of Benin. We prioritized municipalities with a significant number of small ruminants in northern Benin. Agricultural development agents helped us identify accessible villages with a large number of female farmers. Thus, the sample size was chosen with the involvement of these agents. A purposive sampling technique was used to collect the data. This method involves interviewing an initial female farmer through agricultural advisors, who then referred us to another female farmer with small ruminants. This technique allowed us to obtain a precise and homogeneous sample of women, and to optimize our time.

Selection of research units and sampling

Women small ruminant farmers have limited access to natural resources and low participation in decision-making processes (Leila 2014). The research units consisted of women small ruminant farmers in the targeted villages. A total of 120 farmers were surveyed, with 15 farmers per village. They were selected using purposive sampling techniques. Only women who owned at least five sheep or goats (Touré and Ouattara 2001) were interviewed. Female small ruminant farmers voluntarily gave their consent, which could be withdrawn at any time. They were previously informed about the research activities and their benefits before participating, to ensure their voluntariness. We provided participants with all the necessary information to make an informed decision about participating in the research, and gave them time and opportunity to absorb the provided information, ask any questions they might have, and discuss and reflect on their participation. Activities only began once participants had given their consent. We used either written and signed consent or oral consent, depending on the participants’ level of education or literacy. Consent was maintained throughout the research. Interviews were anonymous and no unnecessary personal data about the interviewees were collected.

Data collection

Data collection was conducted from March to June 2021. A quantitative approach was employed through individual interviews using a digitized questionnaire on Kobo-Collect. Data on sociodemographic characteristics, such as age, farming experience, ethnic group, household size, number of agricultural workers, education level, contact with agricultural extension services and membership in farmer organizations, were collected. A second set of questions focused on the women farmers’ perceptions of climate change indicators, including causes, observed phenomena, impacts and effects.

Statistical analysis

The survey data were analyzed using descriptive statistics, statistical inference and the logit regression model with SPSS software (ver. 17). Descriptive statistics were used to calculate means and standard deviations of quantitative variables (e.g. age, size). The determinants influencing farmers’ perceptions of climate change were analyzed using binary logistic regression (Uddin et al. 2017; Kabore et al. 2019). The binary model equation is as follows:

where: Yi is the variable that takes the value one if the farmer perceives a change in a climate indicator and zero if she does not; Xi represents the set of explanatory variables indicating the factors influencing farmers’ perceptions of climate change; and εi is the standard error.

Before estimating the logistic regression model, explanatory variables were tested for multicollinearity using the contingency test of coefficients (Uddin et al. 2017). Collinearity was observed between farming experience and age; between the number of agricultural workers and household size; between membership in a farmer organization and contact with extension services; and between being Christian and Muslim. Consequently, age, number of agricultural workers, contact with extension services and Muslim were omitted from the logistic regression model after the multicollinearity test. The variables of farming experience, Christian, education level, membership in a farmer organization, household size and herd size were used in the regression.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of the interviewed women small ruminant farmers

The sociodemographic characteristics of the interviewed farmers are summarized in Table 2. The average age of the surveyed women farmers was 42 years. This activity was their primary source of income. Two ethnic groups were predominant in the study area: Peulh (45.83%) and Bariba (25.83%). Most of the farmers were uneducated (88.33%), and a small proportion (23.33%) were members of organizations. Additionally, more than half of the women were in contact with extension agents (51.67%), including veterinarians, to receive care and services for their animals. Islam was the most practiced religion (91.67%). More than half of the women (51.47%) had 10 years of farming experience. The majority of households (55.83%) consisted of eight people, and they had five agricultural workers. In this area, 62.5% of the women owned at least 11 sheep and six goats. Sheep farming was mainly performed through fattening. This type of farming provided these women with food and financial security. The production system was extensive, with animals roaming in search of food; during the cropping season, they were sometimes tethered or confined. In the dry season, they received a small supplementary feed.

| Variables | Categories | Scoring method | Respondents (%) | Mean | s.d. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qualitatives variables | ||||||

| Ethnicity | Adja | Language spoken | 0.83 | |||

| Bariba | 25.83 | |||||

| Dendi | 13.33 | |||||

| Gando | 5 | |||||

| Haoussa | 5 | |||||

| Mahi | 0.83 | |||||

| Peulh | 45.83 | |||||

| Sèmairè | 1.67 | |||||

| Zèrimen | 1.67 | |||||

| Education level | Schooled | Dummy | 11.67 | |||

| Unschooled | 88.33 | |||||

| Membership in an organization | Yes | Dummy | 23.33 | |||

| No | 76.67 | |||||

| Contact with extension services | Yes | Dummy | 51.67 | |||

| No | 48.33 | |||||

| Religion | Muslim | Dummy | 91.67 | |||

| Christian | 8.33 | |||||

| Quantitatives variables | ||||||

| Age group (years) | 20–35 | Years | 25.83 | 42.650 | 9.571 | |

| 36–50 | 54.98 | |||||

| >50 year | 19.16 | |||||

| No.r of years of experience in livestock farming (years) | Low (up to 9 years) | Years | 40.01 | 10.483 | 6.962 | |

| Medium (10–26 years) | 51.47 | |||||

| >26 years | 7.52 | |||||

| No.of agricultural workers (persons) | 1–5 | Number | 42.5 | 7.425 | 5.691 | |

| 5–10 | 37.5 | |||||

| >10 | 20 | |||||

| Household size (persons) | 0–10 | Number | 55.83 | 12.425 | 8.396 | |

| 10–20 | 34.17 | |||||

| >20 | 10 | |||||

| Size of sheep flock (head) | 0–10 | Number | 62.5 | 11.841 | 12.938 | |

| 10–20 | 18.33 | |||||

| >20 | 19.17 | |||||

| Size of goat flock (head) | 0–10 | Number | 79.17 | 6.766 | 7.983 | |

| 10–20 | 12.5 | |||||

| >20 | 8.33 | |||||

Farmers’ perception of climate change

Table 3 presents the perception rates of small ruminant farmers in northern Benin regarding climate change. The women farmers perceived climate change through the effects of climatic events on resources available for small ruminants and management techniques. They noticed some shifts in the start and end of the rainy season. Specifically, 73% of the women perceived delayed rainfall, and 70.4% noticed an early cessation of rains, whereas 33% reported a scarcity of rainfall. The majority of the women (87.5%) perceived frequent floods as a significant change. During the rainy season, excess water causes houses to collapse. The women also agreed on the irregularity of rainfall (62.5%) and poor spatial distribution of rain (98%). In this area, many women observed a decrease in the intensity of rainfall (52%), and a reduction in drought occurrences (70%). The impact of pockets of drought on small ruminant farming is poorly perceived by the women, given the small size of their herds. The increase in temperature was perceived through a rise in heat (95%) and a decrease in coolness (61.17%). The women farmers in northern Benin also perceived strong winds (82%) and instability in wind direction (64%).

| Parameters | Indicators of change | Increases | Decreases | No change | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rainfall | Late onset of rains | 73 | 23.73 | 3,27 | |

| Early cessation of rains | 70.42 | 20.58 | 9 | ||

| Rain scarcity | 33.33 | 65 | 1.67 | ||

| Floods | 87.5 | 12.5 | 0 | ||

| Rainfall irregularity | 62.5 | 31.5 | 6 | ||

| Poor spatial distribution of rains | 98 | 0.83 | 1.17 | ||

| High rainfall intensity | 44.17 | 52 | 3.83 | ||

| Drought occurrences | 25.83 | 70 | 4.17 | ||

| Temperature | Increase in heat | 95 | 5 | 0 | |

| Decrease in coolness | 61.17 | 30.83 | 8 | ||

| Winds | Strong winds | 82 | 14.17 | 3.83 | |

| Weaker winds | 31.67 | 66 | 2.33 | ||

| Instability of wind direction | 64 | 30.83 | 5.17 |

Determinants of small ruminant farmers’ perception of climate change

The factors influencing women farmers’ perceptions in the context of climate change were analyzed using binary logistic regression (Table 4). The interpretation of the results is based on the regression of the coefficient and probability (P > t). The continuous variables were age, education level, farming experience, household size, contact with extension services, number of sheep and goats, religion, delayed rains, prolonged rains, scarcity of rains, early cessation of rains, floods, irregularity of rains, increase in heat, decrease in coolness, periods drought, strong winds, weaker winds, and instability in wind direction, which were the dependent variables.

| Age | Education level | Farming experience | Household size | Contact with extension service | No. of sheep | No. of goats | Christians | Constant | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rain delay | ||||||||||

| Coef. | −0.046 | 2.383 | 0.042 | 0.084 | −3.607 | 0.055 | −0.012 | −2.066 | 9.26 | |

| T | −1.2 | 2.53 | 0.74 | 2.05 | −5.09 | 1.97 | −0.25 | −1.58 | 5.13 | |

| P > t | 0.234 | 0.013 | 0.458 | 0.042 | 0 | 0.052 | 0.804 | 0.116 | 0 | |

| Extended rains | ||||||||||

| Coef. | −0.044 | −1.143 | 0.142 | 0.045 | −2.378 | −0.038 | 0.026 | −1.014 | 8.821 | |

| T | −0.99 | −1.04 | 2.15 | 0.95 | −2.87 | −1.17 | 0.46 | −0.67 | 4.19 | |

| P > t | 0.323 | 0.3 | 0.033 | 0.345 | 0.005 | 0.245 | 0.643 | 0.507 | 0 | |

| Early cessation of rains | ||||||||||

| Coef. | 0.036 | 0.897 | 0.054 | 0.039 | 0.676 | 0.026 | 0.046 | 1.245 | 1.723 | |

| T | −0.5 | −0.42 | 2.19 | 3.83 | −6.25 | 0.73 | −0.47 | −2.44 | 4.44 | |

| P > t | 0.62 | 0.672 | 0.031 | 0 | 0 | 0.466 | 0.638 | 0.016 | 0 | |

| Rain scarcity | ||||||||||

| Coef. | 0.064 | −0.9 | −0.04 | 0.07 | −3.202 | 0.077 | −0.152 | −0.292 | 2.118 | |

| T | 1.5 | −0.86 | −0.65 | 1.55 | −4.06 | 2.47 | −2.81 | −0.2 | 1.05 | |

| P > t | 0.135 | 0.391 | 0.519 | 0.125 | 0 | 0.015 | 0.006 | 0.841 | 0.294 | |

| Floods | ||||||||||

| Coef. | −0.052 | 0.811 | 0.084 | −0.061 | −2.499 | 0.052 | −0.03 | −2.722 | 1.186 | |

| T | −1.72 | 1.1 | 1.88 | −1.89 | −4.47 | 2.36 | −0.8 | −2.65 | 8.34 | |

| P > t | 0.088 | 0.276 | 0.062 | 0.061 | 0 | 0.02 | 0.426 | 0.009 | 0 | |

| Rainfall irregularity | ||||||||||

| Coef. | 0.02 | −0.605 | 0.241 | 0.059 | −4.166 | 0.005 | −0.037 | −3.948 | 4.846 | |

| T | 0.48 | −0.58 | 3.84 | 1.31 | −5.31 | 0.19 | −0.7 | −2.73 | 2.42 | |

| P > t | 0.635 | 0.562 | 0 | 0.192 | 0 | 0.852 | 0.484 | 0.007 | 0.017 | |

| Increased heat | ||||||||||

| Coef. | −0.003 | 0.074 | 0.003 | 0.001 | −0.118 | −0.002 | 0.002 | −0.203 | 1 108 | |

| T | −1.8 | 1.43 | 1.26 | 0.63 | −3 | −0.16 | 1 | −2.8 | 10.99 | |

| P > t | 0.075 | 0.156 | 0.212 | 0.531 | 0.003 | 0.874 | 0.318 | 0.006 | 0 | |

| Decreased coolness | ||||||||||

| Coef. | 0.071 | 0.926 | −0.126 | 0.113 | −2.631 | 0.024 | 0.046 | −1.559 | 4.667 | |

| T | 1.62 | 0.87 | −1.96 | 2.43 | −3.27 | 0.77 | 0.84 | −1.05 | 2.27 | |

| P > t | 0.108 | 0.388 | 0.053 | 0.017 | 0.001 | 0.445 | 0.401 | 0.295 | 0.025 | |

| Drought occurences | ||||||||||

| Coef. | 0.011 | −0.226 | 0.007 | 0.129 | −1.387 | −0.062 | −0.046 | −1.171 | 1.566 | |

| T | 0.26 | −0.22 | 1.12 | 2.84 | −1.78 | −2.02 | −0.87 | −0.82 | 0.79 | |

| P > t | 0.795 | 0.827 | 0.265 | 0.005 | 0.079 | 0.046 | 0.384 | 0.417 | 0.433 | |

| Strong winds | ||||||||||

| Coef. | 0.013 | 0.642 | 0.024 | −0.089 | −0.736 | 0.069 | −0.096 | −0.166 | 8.998 | |

| T | 0.38 | 0.76 | 0.49 | −2.42 | −1.16 | 2.74 | −2.21 | −0.14 | 5.55 | |

| P > t | 0.702 | 0.449 | 0.626 | 0.017 | 0.25 | 0.007 | 0.029 | 0.887 | 0 | |

| Weaker winds | ||||||||||

| Coef. | 0.073 | −0.832 | −0.084 | 0.141 | −2.515 | −0.009 | 0.03 | −1.813 | 0.509 | |

| T | 1.68 | −0.78 | −1.3 | 3.01 | −3.12 | −0.29 | 0.56 | −1.22 | 0.25 | |

| P > t | 0.097 | 0.438 | 0.195 | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.773 | 0.578 | 0.224 | 0.805 | |

| Instability of wind direction | ||||||||||

| Coef. | 0.032 | −2.008 | 0.045 | 0.052 | −5.269 | 0.105 | −0.001 | −2.749 | 5.86 | |

| T | 0. 87 | −2.19 | 0.82 | 1.29 | −7.63 | 3.85 | −0.04 | −2.16 | 3.33 | |

| P > t | 0.387 | 0.03 | 0.412 | 0.198 | 0 | 0 | 0.968 | 0.033 | 0.001 | |

A positive coefficient implies an influence on the probability of perception for each unit increase in the dependent variable, whereas a negative coefficient describes the inverse relationship.

The age variable negatively influenced the perception of floods and increased heat at the 10% significance level, and positively influenced the perception of weaker winds at the 10% level. Older women farmers were less likely to perceive floods and increased heat, but were more likely to notice weaker winds compared with others.

The education level of farmers positively influenced the perception of delayed rains at the 5% level, and negatively influenced the perception of instability in wind direction at the 5% level. Educated farmers had quicker access to climate information through communication channels.

Farming experience positively influenced the perceptions of prolonged rains and early cessation of precipitation at the 5% level, floods at the 10% level, and rainfall irregularity at the 1% level. It negatively influenced the decrease in coolness at the 10% level. Women with extensive farming experience were more likely to perceive variations in rainfall and temperature.

Household size positively affected the perception of early cessation of rains, drought pockets and weaker winds at the 1% level. It also positively influenced the perception of delayed rains and a decrease in coolness at the 5% level. Additionally, it negatively affected the perception of floods at the 10% level and strong winds at the 5% level. Larger households were more perceptive of climate change, because the women’s farming income was allocated to family needs.

Contact with extension services positively influenced the perception of early cessation of rains at the 1% level and drought pockets at the 10% level. It negatively influenced the perception of delayed rains, prolonged rains, rain scarcity, floods, rainfall irregularity, increased heat, decreased coolness, weaker winds and instability in wind direction at the 1% level. The more the women interacted with extension agents, the less they perceived variations in rainfall, temperature and wind. Agricultural extension agents, research institutions, non-governmental organizations or rural development projects informed and trained village groups, but did not discuss climate change.

The size of sheep herds positively influenced the perception of delayed rains at the 10% level, rain scarcity and floods at the 5% level, and strong winds and wind direction instability at the 1% level. It negatively influenced the perception of drought pockets at the 5% level. Women with more sheep were more likely to perceive climate change.

The size of goat herds negatively influenced the perception of rain scarcity at the 1% level and strong winds at the 5% level. Women with more goats were less likely to perceive climate change.

Christianity positively influenced the perception of early cessation of rains at the 5% level. It negatively influenced the perception of floods, rainfall irregularity, increased heat at the 1% level and instability in wind direction at the 5% level. Christian women were less likely to perceive climate change compared with Muslim women.

Discussion

Sociodemographic characteristics of the female small ruminant farmers surveyed

The vulnerability of women to climate change stems from various social, economic and cultural factors. Women represent a significant percentage of poor communities who rely on natural resources for their livelihoods. In rural areas, they bear the burden of family responsibilities (UN 2018). In Benin, as in most African rural societies, women actively participate in agricultural production activities while also handling domestic tasks essential for family survival (Amadou et al. 2015).

Small ruminant farming is practiced within an extensive system, and serves as the primary source of income for Fulani and Bariba women. According to Djohy and Sounon Bouko (2021), livestock farming is the main activity for the Fulani, and the second for other sociocultural groups. The female farmers were aged between 28 and 62 years. According to Hitayezu et al. (2017), Rankoana (2018) and Amadou et al. (2015), age positively influences the ability to perceive changes.

The educational level of female farmers in northern Benin was low across almost all sociocultural groups. In Benin, women constitute the majority of illiterates (31% of women were reported as illiterate in 2018 by UNESCO). Their participation in organizations is minimal. This is corroborated by the findings of Guillén Velarde and de la Peña Valdivia (2012), which confirm that women rarely have access to information, and their ability to participate in organizations is limited. Additionally, some women cannot leave their homes without a male companion.

Farmers’ perception of climate change

The results of this study revealed a growing awareness among female farmers about climate change. Most of the small ruminant farmers acknowledged that significant changes in the climate have occurred over the past two decades. These findings align with Chingala et al. (2017), who confirmed that small-scale farmers reported climate variations. They perceived climate change through the delay of rains, prolonged rainy seasons, early cessation of rains, scarcity of rainfall, floods, irregular distribution of rainfall, increased heat, drought pockets, decreased coolness, strong winds, weaker winds and instability in wind direction. Our results are similar to those of Abraham et al. (2019) in Chad, Beye (2018) in Senegal and Nnko et al. (2021) in Tanzania, who reported that farmers perceived climate change through decreased rainfall and increased temperatures in all seasons. Similarly, our findings are consistent with Abdou et al. (2020) in Niger, Owusu et al. (2019), Idrissou et al. (2020), Djohy and Sounon Bouko (2021) and Egah et al. (2024) in Benin, who showed that farmers perceive climate change through rising temperatures, prolonged dry seasons, early cessation of the rainy season and reduced rainfall, with an increased frequency of violent winds. According to Diiro et al. (2016), in the Mopti region of Mali, 83% of respondents noticed an increase in strong winds. For Karimi et al. (2017), livestock farmers are highly vulnerable to extreme weather events. However, Guillén Velarde and de la Peña Valdivia (2012) showed that women’s perceptions are more related to water in the planet’s ecosystems and, consequently, to the life and well-being of humanity and nature. This difference is justified by the activities practiced by women. The low availability of fodder during the dry season allows women to perceive rainfall variability, temperature increases and strong winds.

Determinants of female small ruminant farmers’ perception of climate change

The main determinants for female small ruminant farmers were age, livestock experience, education level, household size, contact with extension services, flock size of sheep and goats, and religion. These results align with the work of Yegbemey et al. (2014), Kimaro et al. (2018), Afouda et al. (2020) and Idrissou et al. (2020), which state that socioeconomic and demographic characteristics help determine the effects of climate change. The binary logistic regression results showed that older female farmers are less likely to perceive floods and increased heat, but more likely to perceive weaker winds. Our results align with those of Owusu et al. (2019), who showed that younger people perceive climate change more due to their exposure to mass media and other modern communication technologies. Formally educated female farmers are more likely to perceive climate change. This result is similar to that of Sanogo et al. (2017) and Owusu et al. (2019), who observed that those with higher education levels have higher sensitivity to climate change. Experienced female farmers perceive the prolongation of rains, early cessation of precipitation, floods and irregular rainfall, and less so the decrease in coolness. This result shows that female farmers with more livestock experience are more likely to perceive climate change. According to Juana et al. (2013), Rankoana (2018), the more experienced livestock farmers have reliable memories of observing climatic phenomena and know more about rainfall patterns. Experience in livestock farming allows women to have a better grasp of fodder availability during the rainy season. In the dry season, they are forced to sell many small ruminants, even the breeding stock (Morton 2007; Mapiye et al. 2009). This would reduce the number of marketable livestock in the long term. These results are similar to those of Gbetibouo (2009), Sanogo et al. (2017) and Uddin et al. (2017), who concluded that experience is a potential determinant of the level of perception of climate change. This study shows that women in large households are more likely to perceive climate change. These households depend on natural resources that are under threat. This result is similar to that of Ehiakpor et al. (2016), who showed that large households are better able to perceive climate change. During the dry season, female farmers face deficits in fodder and concentrates to feed their herds and meet their families’ needs (Chingala et al. 2017). These results are consistent with those of Dugué et al. (2012), Kosmowski et al. (2016) and Uddin et al. (2017), who concluded that households whose livelihoods depend on the rainfed agriculture are more likely to detect changes at the start of the season than changes in rainfall distribution and the frequency of droughts. Women in contact with extension agents perceive less climate change. According to Ehiakpor et al. (2016), women in contact with extension agents are not oriented toward the problem of climate variability.

Women who own sheep perceive climate change more than those who own goats. Sheep prefer fodder more than goats (Jemaa et al. 2016). Drought affects forage production and, more broadly, food autonomy, weakening farm productivity (Béral et al. 2018). In the same vein, Dugué et al. (2012) assert that goats can gradually replace sheep, as they are less demanding in terms of fodder quality, make better use of pastures and tolerate heat better. Muslim female farmers perceive climate change more than Christian female farmers. Northern Benin is characterized by the Islamic religion, with 81% practitioners (De Souza 2014).

Conclusions

The small ruminant farmers in northern Benin are aware of the changes in their environment. For these farmers, climate change is manifested through disruptions in the rainy and dry seasons, characterized by a shift in the beginning and end of both seasons, a shortening of the rainy season, and a lengthening of the dry season. They have also noticed an increase in temperature along with instability in wind direction.

The results show that they are threatened by climate disruptions, particularly rainfall deficit, the early end of the rainy season, rising temperatures and violent winds. According to the breeders, phenomena related to rising temperatures are observed during the dry periods. As for violent winds, they believe these occur throughout the year, but are more frequent during the rainy season. These climatic changes make small ruminant farming highly vulnerable, leading to the scarcity of pastoral resources and the degradation of the health of their animals.

Data availability

The data that support this study will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Declaration of funding

This work was funded by the International Foundation For Science (IFS) through grant I-3-S-6471-1 and by the Organization of Women in Science for the Developing World (OWSD) awarded to principal author Dimon Elodie.

References

Abdou H, Adamou Karimou I, Harouna BK, Zataou MT (2020) Breeders’ perception of climate change and strategies for adapting to environmental constraints: the case of the commune of Filingué in Niger. Revue D’élevage et de Médecine Vétérinaire Des Pays Tropicaux 73(2), 81-90.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Abraham A, Mohamed-Brahmi A, Ngoundo M (2019) Resilience of livestock systems in the Sahelian band of Chad (case of the Kanem region): adaptation tools to climate change. Journal of New Sciences, Sustainable Livestock Management 11(1), 222-230.

| Google Scholar |

Afouda AP, Hougni A, Balarabe O, Kindemin OA, Yabi AJ (2020) Déterminants de l’adoption de la pratique d’intégration agriculture-élevage dans la commune de Banikoara (Benin). Agronomie Africaine 32(2), 159-168.

| Google Scholar |

Amadou LM, Villamor GB, Attua ME, Traoré SB (2015) Comparing farmers’ perception of climate change and variability with historical climate data in the Upper East Region of Ghana. Ghana Journal of Geography 7(1), 47-74.

| Google Scholar |

Béral C, Andueza D, Ginane C, Bernard M, Liagre F, Girardin N, Emile JC, Novak S, Grandgirard D, Deiss V, Bizeray-Filoche D, Thiery M, Rocher A (2018) Agroforesterie en système d’élevage ovin: étude de son potentiel dans le cadre de l’adaptation au changement climatique. Available at http://www.parasol.projet-agroforesterie.net/

Beye A (2018) Perception et gestion des risques climatiques en milieu pastoral Sénégalais. In ‘Annales de l’universite de Lome, serie sciences economiques et de gestion’. Vol. XII. pp. 143–171. (University De Lome Togo) Available at https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Assane_Beye/publication/342098017_PERCEPTION_ET_GESTION_DES_RISQUES_CLIMATIQUES_EN_MILIEU_PASTORAL_SENEGALAIS/links/5ee21757299bf1faac4afa64/PERCEPTION-ET-GESTION-DES-RISQUES-CLIMATIQUES-EN-MILIEU-PASTORAL-SENEGALAIS.pdf

Blanfort V, Vigne M, Vayssières J, Lasseur J, Ickowicz A, Lecomte P (2015) Les l’élevage dans la contribution à l’adaptation et l’atténuation du changement climatique au Nord et au Sud. Agronomie, Environnement et Société 5(1), 107-115 Available at https://agritrop.cirad.fr/592032/.

| Google Scholar |

Chingala G, Mapiye C, Raffrenato E, Hoffman L, Dzama K (2017) Determinants of smallholder farmers’ perceptions of impact of climate change on beef production in Malawi. Climatic Change 142, 129-141.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

COP 21 (2016) Traité international juridiquement contraignant sur les changements climatiques. Paris, France, 28p [in French]. Available at https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/french_paris_agreement.pdf

Corniaux C, Lesnoff M, Ickowicz A, Hiernaux P, Diawara MO, Sounon A, Aguilhon M, Dawalak A, Manoli C, Assani B, Jorat T, Chardonnet F (2012) Dynamique des cheptels de ruminants dans les communes de Tessékré (Sénégal), Hombori (Mali), Dantiandou (Niger) et Djougou (Bénin). Contribution de l’élevage à la réduction de la vulnérabilité des ruraux et à leur adaptabilité aux changements climatiques et sociétaux en Afrique de l’Ouest au sud du Sahara. Livrable 3.1., tache elev. p. 43.

Defrance D, Ramstein G, Charbit S, Vrac M, Famien AM, Sultan B, Swingedouw D, Dumas C, Gemenne F, Alvarez-solas J, Vanderlinden J-P (2017) Consequences of rapid ice sheet melting on the Sahelian population vulnerability. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114(25), 6533-6538.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Diiro G, Petri M, Zemadim B, Sinare B, Dicko M, Traore D, Tabo R (2016) Gendered analysis of stakeholder perceptions of climate change, and the barriers to its adaptation in mopti region in Mali. Research report no. 68. Patancheru 502 324. International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics, Telangana, India. p. 52.

Djohy GL, Sounon Bouko B (2021) Vulnerability and adaptive dynamics of agropastoralists to climate change in the commune of Tchaourou in Benin. Journal of Livestock and Veterinary Medicine of Tropical Countries 74(1), 27-35.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Egah J, Dimon E, Odou JM, Houngue E, Baco MN (2024) Analyse genrée de la vulnérabilité et du mécanisme d’adaptation au changement climatique au Nord-Bénin. VertigO – la revue électronique en sciences de l’environnement [En ligne]

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ehiakpor DS, Danso-abbeam G, Baah JE (2016) Cocoa farmer’s perception on climate variability and its effects on adaptation strategies in the Suaman district of western region, Ghana. Cogent Food & Agriculture 2(1), 1210557.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

FAO (2016) ‘Climate change and food security: risks and responses.’ (FAO) Available at http://www.fao.org/3/a-i5188e.pdf

Feleke FB, Berhe M, Gebru G, Hoag D (2016) Determinants of adaptation choices to climate change by sheep and goat farmers in Northern Ethiopia: the case of Southern and Central Tigray, Ethiopia. SpringerPlus 5, 1692.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Gbetibouo GA (2009) Understanding farmers perceptions and adaptations to climate change and variability: the case of the limpopo basin farmers South Africa. International Food Policy Research Institute, Center for Environmental Economics and Policy in Africa. p. 2. Available at www.ifpri.org

Gemenne F, Blocher J, De Longueville F, Vigil Diaz Telenti S, Zickgraf C, Gharbaoui D, Ozer P (2017) Changement climatique, catastrophes naturelles et déplacements de populations en Afrique de l’Ouest. Geo-Eco-Trop 41(3), 317-337 Available at https://www.geoecotrop.be/uploads/publications/pub_413_02.pdf.

| Google Scholar |

Gnanglè CP, Glèlè-Kakaï R, Assogbadjo AE, Vodounnon S, Yabi AJ, Sokpon eN (2011) Tendances climatiques passées, modélisation, perceptions et adaptations locales au Bénin. Climatologie 8, 27-40.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Guillén Velarde R, de la Peña Valdivia M (2012) Recherche sur les conséquences du changement sur les femmes et les processus migratoires: le cas de la haute région andine péruvienne. Recherche & Plaidoyer, Le Monde selon les femmes: Dépôt légal: D/2012-7926-03. Available at https://genderclimatetracker.org/sites/default/files/Resources/Puno_Peru.pdf

Herrero M, Grace D, Njuki J, Johnson N, Enahoro D, Silvestri S, Rufino MC (2013) The roles of livestock in developing countries. Animal 7(S1), 3-18.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hitayezu P, Wale E, Ortmann G (2017) Assessing farmers’ perceptions about climate change: a double-hurdle approach. Climate Risk Management 17, 123-138.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hounzangbé-Adote MS, Azando E, Awohouedji Y (2011) Biodiversité dans les zones d’élevage des petits ruminants Mammifères domestiques Bénin. In ‘Atlas de la biodiversité en Afrique de l’Ouest’. (Eds B Sinsin, D Kampmann) pp. 505–518. Available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/262564761

Idrissou Y, Assani SA, Baco MN, Alkoiret TI (2020) Determinants of cattle farmers’ perception of climate change in the dry and sub-humid tropical zones of Benin (West Africa). In ‘African handbook of climate change adaptation’. (Eds W Leal Filho, N Ogugu, L Adelake, D Ayal, I da Silva) pp. 1–16. (Springer Nature: Cham) 10.1007/978-3-030-42091-8_16-1

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (2019) Climate change and land: an IPCC special report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems. IPCC. p. 43. Available at https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2019/08/4.-SPM_Approved_Microsite_FINAL.pdf

Jélu M, Bourgeais SV (2015) La place des femmes en élevage. In ‘4èmes Rencontres nationales travail en élevage, Atelier 12’. (Ed. K Brulat) pp. 110–117. (Institut de l’élevage) Available at https://idele.fr/fileadmin/medias/Documents/Atelier_12_def.pdf

Jemaa T, Huguenin J, Moulin C-H, Najar eT (2016) Les systèmes d’élevage de petits ruminants en Tunisie Centrale: stratégies différenciées et adaptations aux transformations du territoire. Cahiers Agricultures 25(4), 45005.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Juana JS, Kahaka Z, Okurut FN (2013) Farmers’ perceptions and adaptations to climate change in sub-Sahara Africa: a synthesis of empirical studies and implications for public policy in African Agriculture. Journal of Agricultural Science 5(4), 121-135.

| Google Scholar |

Kabore PN, Barbier B, Ouoba P, Kiema A, Some L, Ouedraogo A (2019) Perceptions du changement climatique, impacts environnementaux et stratégies endogènes d’adaptation par les producteurs du Centre-nord du Burkina Faso. VertigO 19(1), 27 Available at https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1065432ar.

| Google Scholar |

Karimi V, Karami E, Keshavarz M (2017) Vulnerability and adaptation of livestock producers to climate variability and change. Rangeland Ecology & Management 71(2), 175-184.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Kimaro EG, Mor SM, Toribio J-ALML (2018) Climate change perception and impacts on cattle production in pastoral communities of northern Tanzania. Pastoralism 8, 19.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Kosmowski F, Leblois A, Sultan B (2016) Perceptions of recent rainfall changes in Niger: a comparison between climate-sensitive and non-climate sensitive households. Climatic Change 135(2), 227-241.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Leila R (2014) Le genre et le changement climatique, réalités sur le lien, projet GEPE, 54-58. Available at http://uest.ntua.gr/adapttoclimate/proceedings/full_paper/Rajhi.pdf

Mapiye C, Chimonyo M, Dzama K (2009) Seasonal dynamics, production potential and efficiency of cattle in the sweet and sour communal rangelands in South Africa. Journal of Arid Environments 73(4–5), 529-536.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Mehu (2011) ‘Deuxième communication nationale de la république du Bénin sur les changements climatiques.’ (Eds SG Akindele, E Ahlonsou, N Aho) p. 168. (Ministère de l’Environnement, de l’Habitat et de l’Urbanisme: Cotonou). Available at https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/natc/bennc2f.pdf

Morton JF (2007) The impact of climate change on smallholder and subsistence agriculture. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 104(50), 19680-19685.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Naqvi SMK, Sejian V (2011) Global climate change: role of livestock. Asian Journal of Agricultural Science 3(1), 19-25.

| Google Scholar |

National Association of Professional Organizations of Ruminant Breeders (2014) La situation actuelle de l’élevage et des éleveurs de ruminants au Bénin. Annexe du document d’orientation stratégique de l’Anoper, 68 p [in French]. Available at https://www.inter-reseaux.org/wp-content/uploads/DOS_ANOPER-1.pdf

Nnko HJ, Gwakisa PS, Ngonyoka A, Estes A (2021) Climate change and variability perceptions and adaptations of pastoralists’ communities in the Maasai Steppe, Tanzania. Journal of Arid Environments 185, 104337.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Owusu M, Nursey-Bray M, Rudd D (2019) Gendered perception and vulnerability to climate change in urban slum communities in Accra, Ghana. Regional Environmental Change 19, 13-25.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ozer P, Hountondji Y-C, Niang AJ, Karimoune S, Laminou Manzo O, Salmon M (2010) Désertification au Sahel: historique et perspectives. Bulletin de la Société Géographique de Liège 54, 69-84.

| Google Scholar |

Rankoana SA (2018) Human perception of climate change. Weather 73(11), 367-370.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Sanogo K, Binam J, Bayala J, Villamor BG, Kalinganire A, Dodiomon S (2017) Farmers’ perceptions of climate change impacts on ecosystem services delivery of parklands in southern Mali. Agroforestry Systems 91(2), 345-361.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Simelton E, Quinn CH, Batisani N, Dougill AJ, Dyer JC, Fraser EDG, Mkwambisi D, Sallu S, Stringer LC (2013) Is rainfall really changing? Farmers’ perceptions, meteorological data, and policy implications. Climate and Development 5(2), 123-138.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Stringer LC, Akhtar-Scuster M, Marques MJ, Amiraslani F, Quatrini S, Abraham EM (2011) Combating land degradation and desertification and enhancing food security: towards integrated solutions. Annals of Arid Zone 50(3&4), 243-256.

| Google Scholar |

Touré G, Ouattara Z (2001) Elevage urbain des ovins par les femmes à Bouaké, Côte d’Ivoire. Cahiers Agricultures 10(1), 45-49 Available at https://revues.cirad.fr/index.php/cahiers-agricultures/article/view/30278.

| Google Scholar |

Uddin MN, Bokelmann W, Dunn ES (2017) Determinants of farmers’ perception of climate change: a case study from the coastal region of Bangladesh. American Journal of Climate Change 6, 151-165.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

UN (2018) The Sustainable Development Goals Report, 40p: António Guterres, Secretary-General of the United Nations, New York. Available at https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/files/report/2018/thesustainabledevelopmentgoalsreport2018-en.pdf

Vodounou JBK, Doubogan eYO (2016) Agriculture paysanne et stratégies d’adaptation au changement climatique au Nord-Bénin. European Journal of Geography 18, 27836.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

World Bank (2012) Rapport sur le développement dans le monde: L’égalité des sexes et le développement. World Bank. ©World Bank. Available at https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/4391

Yegbemey RN, Yabi JA, Aïhounton GB, Paraïso A (2014) Modélisation simultanée de la perception et de l’adaptation au changement climatique: cas des producteurs de maïs du Nord Bénin (Afrique de l’Ouest). Cahiers Agricultures 23(3), 177-187.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |