Choice of companion legume influences lamb liveweight output and grain yields in a dual use perennial wheat/legume intercrop system

Matthew T. Newell A * , Richard C. Hayes B , Gordon Refshauge A C , Benjamin W. B. Holman

A * , Richard C. Hayes B , Gordon Refshauge A C , Benjamin W. B. Holman  B C , Neil Munday D , David L. Hopkins C and Li Guangdi B

B C , Neil Munday D , David L. Hopkins C and Li Guangdi B

A

B

C

D

Abstract

Perennial cereals are being developed for dual roles of forage and grain production. Like other cereals, perennial wheat (PW) forage requires mineral supplementation if grazed by ruminants.

To investigate the effect on liveweight gain in lambs grazing PW/legume intercrops in comparison to grazing PW with a mineral supplement. Effects of intercropping and impact of grazing on PW grain yield were also investigated.

Lambs (14-week-old, n = 144) grazed one of four treatments, namely PW with a mineral supplement (PW + Min) or PW intercropped with either lucerne (Medicago sativa) (PW + L), subterranean clover (Trifolium subterraneum) (PW + C), or French serradella (Ornithopus sativus) (PW + S) for 12 weeks. Treatments were arranged in a randomised block design with six replicates. Following grazing, grain yield from each treatment was compared with an ungrazed control upon maturity.

Intercropping with either subterranean clover or French serradella increased carrying capacity and total liveweight grain, similar to the PW + Min treatment and supported a higher stocking rate compared with the PW + L treatment. Sodium concentration was approximately 10-fold higher in the herbage of subterranean clover and serradella compared with PW, and 5-fold higher than lucerne. Grain yields from intercropping were lower compared with PW + Min due to the reduction in perennial wheat density. However, proportionally, PW grain yield was improved in the PW + S and PW + L treatments with a Net Effect Ratio (NER) > 1.

Increased feed availability from the provision of forages, such as subterranean clover and French serradella, enabled greater liveweight output through greater carrying capacity of grazing lambs when compared with a PW + L diet. However these were not different to PW + Min. Improved sodium intake is also implicated in this result, however not confirmed by this study. Grain yields were not affected by grazing, although they were reduced by intercropping. However, the comparative improvement in PW grain yield (NER) in combination with a compatible legume, along with increased grazing days, highlight the potential of intercropping where more than one product is produced in a multi-functional, dual-purpose perennial grain system.

The comparative improvement in grain yield from intercropping, coupled with increased liveweight change, supports the use of compatible legume intercrops in dual-purpose perennial grain systems.

Keywords: alfalfa, forage minerals, Land Equivalent Ratio, Net Effect Ratio, perennial cereals, perennial crops, serradella, subterranean clover.

Introduction

Dual-purpose crops providing forage for grazing livestock and subsequent grain yield are commonly utilised in the cooler, higher elevations of the high rainfall zone of southern Australia (Dove and Kirkegaard 2014; Dove et al. 2015; Sprague et al. 2018). Historically, agricultural production in these regions was predominately based on permanent pastures for grazing. The addition of a fast-growing, dual-purpose winter crop helps to fill a winter feed-gap when pasture growth is low, allowing an increase in stocking rates (Bell et al. 2014; Dove et al. 2015). Higher growth rates in young livestock can be achieved from grazing cereals, particularly if mineral deficiencies in the forage are remedied and supplementation is provided with magnesium (Mg) and sodium (Na) (Dove and McMullen 2009; Dove et al. 2016). The opportunity for high grain yields through cropping in a milder climate with a longer growing season, coupled with the ability to diversify production, has increased interest in further expanding cropping practices in these regions.

However, there are inherent environmental risks caused by the replacement of perennial-based permanent pastures with an annual cropping system, including increased risk of soil erosion, altered soil hydrology, and reduced soil organic matter (Lefroy and Stirzaker 1999; Bell et al. 2014; Crews et al. 2016). In contrast, growing perennial cereals has potential to reduce the environmental impact compared with annual winter cereals due to a lower frequency of disturbance (Crews et al. 2018). Furthermore, the longer maturity and higher forage production of perennial cereals has potential to increase flexibility of management decisions, allowing producers to switch between grain and forage production as seasonal conditions permit (Bell 2013; Newell and Hayes 2017).

Intercropping involves growing multiple species, usually from different functional groups, to increase the resource use efficiency, resulting in fewer external inputs (Betencourt et al. 2012; Fletcher et al. 2016). Intercropping annual cereals with legumes has been extensively studied, with proven benefits for the supply and utilisation of fixed atmospheric nitrogen (N) from legumes by cereals (Walker et al. 2009; Chapagain and Riseman 2014; Atabo and Umaru 2015; Daryanto et al. 2020). In perennial cereals, the benefit of intercropping may be greater due to the longer growing season compared with annual cereals (Tautges et al. 2018; Crews et al. 2022). Similar to annual winter cereals, ruminants grazing perennial cereals require supplementation of calcium (Ca), Mg and Na to minimise the risk of metabolic disorders, which may be reduced when intercropped with legumes (Newell et al. 2020a; Refshauge et al. 2022).

Forage legumes typically accumulate more Ca and Mg than grasses (Juknevičius and Sabienė 2007; Lee 2018), acknowledging substantial variation between species in the accumulation of minerals in herbage, particularly Na. Smith et al. (1978) showed that legumes such as subterranean clover (Trifolium subterraneum L.), white clover (Trifolium repens L.) and greater lotus (Lotus pedunculatus Cav.) could accumulate eight times the concentration of Na in their leaves compared with lucerne (alfalfa, Medicago sativa L.). Field studies in Australia showed that Na accumulation in lucerne herbage was an order of magnitude lower than in the forage grass phalaris (Phalaris aquatica L.) (Hayes et al. 2008), but an order of magnitude higher compared with forage from wheat and perennial wheat (Newell and Hayes 2017). A recent study, in which 10-month-old lambs were fed either perennial wheat (PW) or annual wheat in combination with lucerne, demonstrated that Ca supplementation was no longer required in the biculture diet. However, due to the low Na concentration of all the forages in that study, supplementation of Mg and Na was still necessary (Newell et al. 2020a). Providing external mineral supplements is imprecise and inefficient, adding material costs to production (Masters 2018; Darch et al. 2020). Given the range of forage legumes available, with varying mineral profiles (Wheeler and Dodd 1995), it seems feasible to design perennial wheat/legume intercropping combinations that would allow grazing animals to select their own diet to better meet their mineral nutrition requirements (Provenza et al. 2003), perhaps without the need for further supplementation.

Although previous research has established that PW is suitable as an alternative forage source for lambs, there are still questions over which forage legume can best meet the nutritional demands of these livestock and which are complementary to grain production of perennial wheat. Furthermore, few studies have examined the effects of grazing winter biomass on grain yields in intercropped perennial cereal crops. There is a plethora of metrics used to assess intercropping performance in comparison to monocultures of component species, with the Land Equivalent Ratio (LER) extensively used (Khanal et al. 2021; Li et al. 2023). LER equates the land area required by the monoculture crop to produce the yield of the same component species in an intercrop. Although LER is a measure of land area, it can be misinterpreted as a measure of relative yield of the intercrop over the monoculture. Therefore, it is unable to reflect absolute yields. Both Harris et al. (1987) and Li et al. (2020) promote the Net Effect Ratio (NER) as a more appropriate metric to measure the performance of intercrop components in relation to their respective monocultures. In this metric, the monoculture crop yield is multiplied by the proportion it occupies in the intercrop. This provides the expected productivity if the same area had been sown with monoculture in the same proportions as the intercrop.

In this study, we examined the establishment year of a dual-purpose PW system when intercropped with one of three forage legumes: French serradella (Ornithopus sativus Brot.), subterranean clover, or lucerne. We hypothesised that intercropping would lead to higher liveweight change compared with a monoculture of PW with a mineral supplement, due to the contrasting mineral profile of the legume forage. We also examined the effect of grazing and intercropping on the grain yield of PW under these treatments.

Materials and methods

Site description and use of animal subjects

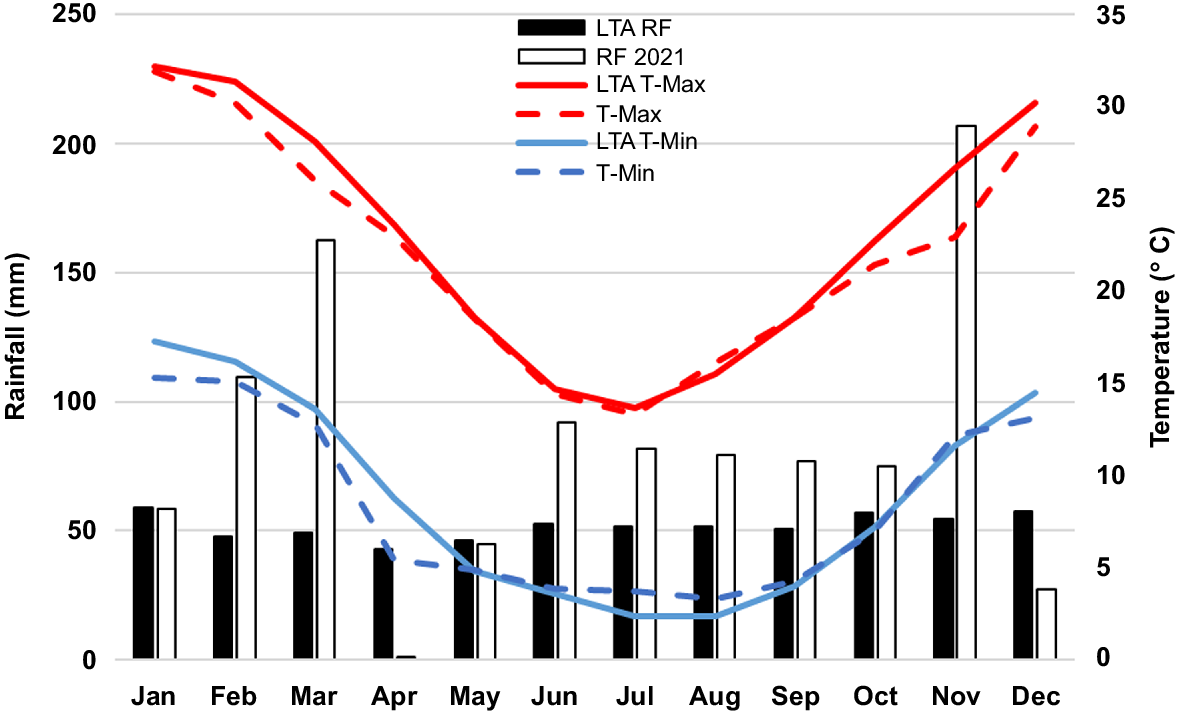

The experiment was conducted at the New South Wales Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development (NSW DPIRD) Cowra Agricultural Research and Advisory Station (S33°48.211′, E148°42.236′, 385 m altitude). The soil was a Red Chromosol (Isbell 1996) with a pH of 5.9 (CaCl2) at the 0.0–0.1 m depth (Table 1). The average annual rainfall recorded at this site since 1905 was 620 mm (Fig. 1). In 2021 (the year the study was conducted), the rainfall received was 1015 mm, the 7th wettest year on record for this site. Mean yearly maximum and minimum temperatures were lower than average, ranking 2021 among the 5th and 10th coolest years, respectively.

| Soil parameter | ||

|---|---|---|

| pHCa | 5.9 | |

| Colwell P (mg/kg) | 47 | |

| Total N (mg/kg) | 26 | |

| Colwell K (mg/kg) | 328 | |

| Organic carbon (%) | 0.75 | |

| EC (dS/m) | 0.09 |

Monthly 2021 and long-term average (LTA) rainfall (RF), along with 2021 mean monthly maximum temperature (T-Max), mean monthly minimum temperature (T-Min) and LTA temperature recorded at Cowra Agricultural Research and Advisory Station.

Authority to conduct this experiment was provided by NSW DPIRD Animal Ethics Committee, Orange (ORA: 20/23/029). All procedures were compliant with the Animal Research Act 1985 (NSW), Animal Research Regulation 2010 (NSW) and the Australian Code of Practice for the Care and Use of Animals for Scientific Purposes (8th Edition 2013).

Experiment design

The study consisted of four forage types (treatments), replicated six times (blocks), in a randomised row column design as described by Coombes (2020). There were 48 plots in total with plot size 90.0 m × 8.4 m, occupying a land area of 5 ha (inclusive of internal laneways) divided by four contour banks. The treatments were perennial wheat with mineral supplement (PW + Min), perennial wheat with either lucerne cv. Titan 9 (PW + L), subterranean clover cv. Leura (PW + C), or French serradella cv. Margurita (PW + S). The perennial wheat breeding line, 11955, was a 2n = 56 partial amphiploid that was derived from a cross between Triticum aestivum × Thinopyrum ponticum (Hayes et al. 2012; also described as PI 550713 in Cox et al. (2002)) and was previously observed to exhibit favourable grain attributes and persist well in the Cowra environment (Larkin et al. 2014; Hayes et al. 2018). The three companion legume species were chosen to provide a contrast in the mineral profile of the forage on offer. In the PW + Min treatment, a mineral supplement was provided ad libitum, which contained a 1:1:1 (w/w) ratio of lime (CaCO3): Causmag (MgO): salt (NaCl). The mineral supplement was mixed thoroughly and supplied in a metal trough with a roof, located within the plot and was exchanged weekly. The uneaten supplement was removed, dried and weighed at the end of each week to determine average daily intake by each animal and replaced with fresh supplement.

Each block of forage contained two plots of a given forage type to accommodate a two-plot (plots ‘A’ and ‘B’) rotational, 28-day grazing system, which included a cycle of 14 days of grazing followed by 14 days of recovery for each plot. Each plot housed up to six lambs, equivalent to 79.4 lambs/ha. Each plot was individually fenced and included access to water. Fenced laneways allowed lambs to move between plots and back to a central yard for weighing. The grazing experiment ran for 89 days.

Forage production

The experimental area was chemically fallowed (2 L/ha glyphosate 450 g/L + 1 L/ha 2,4-D amine Advance 700 g/L) approximately 5 months prior to sowing the forage treatments. The site was cultivated in the week prior to sowing. The four forage treatments were sown on 16 May 2021 using a John Shearer seeder fitted with narrow sowing points and press wheels set at 18 cm row spacing. The PW + Min treatment was sown at 70 kg/ha through the main seeding box on the seeder, utilising every drill row. The three companion legume treatments were sown at high seeding rates (24 kg/ha for lucerne, 35 kg/ha for subterranean clover and 32 kg/ha for French serradella). While the legumes were sown through the small seeds box of the seeder in every drill row, the PW was sown in alternate rows in the intercrop treatments by blocking off every second seeding tube. This effectively halved the sowing rate of perennial wheat on an area basis, but maintained the same number of PW seeds per linear sowing row. This enabled the legume composition of the swards to be maximised (Hayes et al. 2024).

At sowing, the whole area received 100 kg/ha diammonium phosphate to provide 20 kg/ha phosphorous, 18 kg/ha nitrogen and 1.6 kg/ha sulfur (S). An additional 100 kg urea (46 kg/ha nitrogen) was applied to all treatments 5 weeks prior to grazing. All plots received 25 g of flumetsulam 800 g/kg + 300 mL of chlorpyrifos 500 g/L for broadleaf weed and insect control 4 weeks after sowing.

Grazing management

White Suffolk × Merino ewe lambs (n = 72) and wether lambs (n = 72) at 14 weeks of age were selected from the same flock, immediately after weaning. Ewe lambs were grazed on the perennial wheat surrounding the experimental plots for 1 week as an introduction to the forage. Wether lambs arrived at the experiment site 1 day prior to commencement, however had been grazing winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) beforehand.

The experiment began on 23 June 2021 (day 0) with all lambs weighed individually and sorted by weight. Each lamb was allocated to a forage treatment on the basis of stratified liveweight, sorted in ascending order in a revolving pattern to minimise variability between replicates in initial liveweight. Lambs were divided into 24 groups, three ewe lambs and three wether lambs in each, and allocated to plots at random. The mean liveweight was 33.1 ± 1.9 kg for ewe lambs and 31.8 ± 1.4 kg for the wether lambs. Each lamb received a radio frequency identification tag and a visual ear tag identifying the plot number and treatment to which it was allocated. Tags were used in opposing ears to identify the sex of the animal.

Adjustments to stocking rate were made during the experiment, based upon feed availability in each treatment. This was done so that feed on offer was maintained above a threshold of 1600 kg/ha, in order to maintain a high forage quality and maximise feed intake (Oddy and Allan 2001). Animals that left the experiment during this period were not reintroduced. Forage growth was highest in block 1 and consequently, this maintained a higher stocking rate for the majority of the experiment compared with the remaining blocks. In week 5, the wethers were removed from the PW + L treatment in blocks 2–6. In week 8, the stocking rate was reduced to three ewe lambs in the PW + Min and PW + S treatments in blocks 2–6. In week 9, the same reduction in stocking rate occurred for the PW + C for blocks 2–6. The remaining wethers in all treatments of block 1 were removed in week 10 (day 71) as all ewe lambs moved to the ‘B’ rotation plots. The ewe lambs spent five extra days in the B rotation plots in the final days of the experiment (equivalent to 39.7 lambs/ha) and were removed and weighed on day 89 of the experiment.

Forage intake and quality analysis

In order to estimate forage intake, grazing exclusion cages were used to measure forage disappearance (‘t Mannetje 1978). Two cages, 1.0 m × 1.0 m × 0.5 m high, constructed of galvanised steel mesh, were placed at representative locations at opposite ends of each plot and fixed to the ground with two steel pins. Paired samples of forage were taken at weekly (7-day) intervals of grazing from inside and outside of each of the cages by cutting herbage in a 0.5 m × 0.5 m quadrat to a height of ~10 mm. The quadrats were placed at 45° to the drill rows to avoid biasing samples in the intercrop treatments that were sown in an alternate row configuration. The quadrat outside the exclusion cage was placed some distance away (~2–5 m) from the cage to reduce any localised effects of trampling or preferential grazing caused by the presence of the exclusion cage, or edge effects on the quadrat placed within the exclusion cage. Herbage was sorted into three components: perennial wheat, sown legume, and unsown ‘weeds’. Each component was dried separately at 60°C for 48 h to determine dry matter (kg DM/ha). The difference between forage inside and outside the cage was used to estimate the pasture growth rates and average daily dry matter intake (DMI) of each forage type by the lambs.

Grab samples of each forage type within a treatment were collected separately on a weekly basis, only from the plots being grazed in that week, by sampling at 10 equally spaced points on a diagonal transect through the plot. Total grab sample was approximately 500 g of fresh forage and taken from the top 0.1 m of plant growth. Samples were dried at 60°C for 48 h and ground using a laboratory mill (Christy and Norris Ltd. Chelmsford) fitted with a 1 mm screen. Each totalled ~150 g of dry plant material. A subsample of the ground material was used to determine neutral detergent fibre (NDF), crude protein (CP), DM digestibility (DMD), digestibility of organic matter in the DM (DOMD) and water soluble carbohydrate (WSC) via near infrared (NIR) spectroscopy (AFIA 2014) at the Feed Chemistry Laboratory (ISO 17025 (NATA), Wagga Wagga, Australia). A subset of random samples was selected (representing 10% of the total samples) and analysed using conventional wet chemistry methods to confirm the estimated values from the NIR calibration (AFIA 2014). Metabolisable energy (ME) was calculated according to method 2.2R (AFIA 2014) from DOMD using the equation ME = 0.203 × DOMD − 3.001.

A second subsample of ground material was analysed by the AgEnviro Laboratory (ISO 14173 (NATA), Wollongbar, Australia) to determine Ca, Mg, P, K, Na and S contents, through closed vessel microwave nitric acid and hydrogen peroxide digestion (SPAC 1998) and processed using ICP-OES (Agilent 5110, ICP_OES). Chloride concentration was determined using an additional extraction in 1:125 water solution using the ferricyanide method (SPAC 1998) on a flow injection analyser (QuikChem 8000, Lachat).

Mineral indices were determined using the molecular weight of the respective mineral as follows: The K:(Na + Mg) ratio was calculated from the concentration of each mineral using the formula (K/0.039)/((Na/0.023) + (Mg/0.012)) (Dove et al. 2016). The tetany index was calculated as (K/0.039)/((Mg/0.012) + (Ca/0.02)) (Kemp and ‘t Hart 1957) and the dietary cation–anion difference (DCAD; mEq/100 g) was calculated using the formula (Na/0.023 + K/0.039) − (Cl/0.0355 + S/0.016) (Takagi and Block 1991). The Ca:P ratio was calculated from the concentration of each mineral in a forage type.

Liveweight gain

On day 0, each lamb was weighed (to 0.2 kg) using a weigh crate (MP600 load bars, Tru-Test™) and a Tru-Test XR5000 indicator (Datamars Ltd., Auckland). The lambs were immediately transported to their respective plot on a trailer following weighing. Liveweight was recorded at the beginning of each week during the experiment. On the last day (day 89) of grazing, all ewe lambs were weighed upon removal from the plots. All wether lambs, which were removed as part of the grazing management, had their final weight recorded immediately as they exited the experiment. No curfew was initiated prior to weighing a lamb as it entered or exited the experiment. Liveweight gain was calculated as the entry weight of the animal subtracted from the exit weight. The total liveweight gain was then calculated across all six animals in a treatment regardless of when it left the experiment.

Anthesis dry matter and grain yield components

In three out of six replicates in the B rotation plots (12 plots in total), an area inside each plot, measuring 6 m × 4 m, was fenced to permanently exclude animals, so that the effect of grazing on grain yield could be determined. At the time of anthesis in the perennial wheat, two 0.25 m × 0.25 m quadrats were placed randomly in separate locations and herbage cut to a height of 10 mm. Corresponding samples were taken from the grazed area using the same quadrats placed a short distance from the exclusion area to avoid any influence of the fencing. Herbage was sorted into crop, sown legume, and weed components and dried as described previously.

Grain yield was determined (on 22 December 2021) at physiological maturity by taking two additional quadrat cuts, both inside and outside the permanent exclusion area, as described previously and with care to avoid the areas sampled at anthesis. From each sample, 20 representative tillers were weighed and used to calculate total tiller production. Seed heads were removed and threshed in a stationary thresher (Wintersteigar LD 350, Austria) to determine total grain weight, grain size (thousand kernel weight; TKW), and harvest index (HI). The remaining area of all A and B plots was harvested separately for grain yield with a commercial harvester (International 1420, USA) on the 27 January 2022.

The effect of intercropping on grain yield in each treatment was further examined by calculating the Net Effect Ratio (NER). This reflects the weighted grain yield given its proportion in the intercropped treatment, compared with the yield in the monoculture treatment. This was applied to all plots in the study using the PW + Min grain yield compared with the corresponding legume treatments in each replicate using the following equation (Li et al. 2023):

The PW + Min grain yield was halved as it occupied 50% of the total sown area in the intercropped treatments. Therefore, grain yield was compared over the same proportion of sown area.

Statistical methods

Analysis of the components of forage quality, mineral content, and associated indices was performed in Genstat (20th Edition, VSN International Ltd., www.vsni.co.uk) using a linear mixed model fitted with ‘Treatment’, with the addition of ‘forage component’ (cereal or legume) as fixed effects, and block as the random effect. Statistical difference was accepted at the 95% significance level (P < 0.05).

The forage intake, as calculated by disappearance in sward components (cereal and legume) between weekly measures, was fitted with a spline using a linear mixed model in ASReml-R (Butler 2020). Each component was analysed separately, with fixed terms used in the model for treatment, time (measurement date) and their interactions. Random terms included block and the spline component of time and their interaction. Terms excluded from the final model had failed to achieve statistical significance. Testing fixed effects used the Wald statistical test, whereas random effects were tested using the residual maximum likelihood ratio test.

Liveweight output was the sum of liveweight gain for each plot and adjusted to a hectare scale (kg/ha). Data were analysed in Genstat using analysis of variance (ANOVA) models fitted with forage treatment as the fixed effect and block as the random effect.

Anthesis dry matter, grain yield, tiller number, HI and TKW data were analysed using Genstat. Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted using ‘Treatment’ and ‘Rotation’ (‘A’ or ‘B’ plots) and their interactions as fixed effects, and block as the random effect. Least significant difference was calculated at the 5% level.

Results

Forage mineral concentration

Mineral concentrations were averaged across measurement dates to provide a representative concentration over the grazing period. This value was used for comparisons between the supply of minerals from forages of PW (cereal) and the legume component of each treatment, with the published requirements (NRC 2007) for a 50 kg lamb growing at 250 g/day (Table 2a). In the separation of species for analysis, unsown weeds were found to be a very minor component of the available forage. Hence their presence is not referred to in the accompanying results. All forages provided the minimum concentration of Ca, Mg, P, S, and Cl. The PW forage was deficient in Na across all intercrops, whereas K ranged from 3.4 to 3.65% of DM and was in excess of requirements. Concentration of Na was more than adequate for lamb requirements in both clover and serradella, but not in lucerne.

| (a) | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca (%) | Mg (%) | P (%) | K (%) | Na (%) | S (%) | Cl (%) | |||||||||

| Lamb required level | > 0.28 A | > 0.09 A | > 0.24 A | < 3 B | > 0.06 B | > 0.18 B | > 0.04 A | ||||||||

| Cereal | Legume | Cereal | Legume | Cereal | Legume | Cereal | Legume | Cereal | Legume | Cereal | Legume | Cereal | Legume | ||

| PW + Min | 0.39 | 0.13 | 0.42 | 3.50 | 0.01 | 0.40 | 0.40 | ||||||||

| PW + C | 0.42 | 1.15 | 0.15 | 0.24 | 0.44 | 0.39 | 3.49 | 2.79 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.43 | 0.29 | 0.43 | 0.29 | |

| PW + L | 0.38 | 1.41 | 0.13 | 0.20 | 0.41 | 0.45 | 3.40 | 2.80 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.39 | 0.33 | 0.39 | 0.33 | |

| PW + S | 0.40 | 0.99 | 0.15 | 0.25 | 0.43 | 0.46 | 3.65 | 2.73 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.45 | 0.26 | 0.45 | 0.26 | |

| s.e. | 0.022 | 0.003 | 0.008 | 0.044 | 0.003 | 0.007 | 0.007 | ||||||||

| P-value F | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| (b) | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca:P | DCAD (mEq/100 g) | Tetany Index | K:Na + Mg | WSC (%) | NDF (%) | CP (%) | ME (MJ/kg DM) | ||||||||||

| Lamb required level | 1.2 A | < 12 C | < 2.2 D | < 6 E | 40 | 9.4 A | 12 A | ||||||||||

| Cereal | Legume | Cereal | Legume | Cereal | Legume | Cereal | Legume | Cereal | Legume | Cereal | Legume | Cereal | Legume | Cereal | Legume | ||

| PW + Min | 0.9 | 51.9 | 4.4 | 8.1 | 9.8 | 42.0 | 24.6 | 11.7 | |||||||||

| PW + C | 1.0 | 3.0 | 51.0 | 51.7 | 4.1 | 1.2 | 6.9 | 3.0 | 8.5 | 9.0 | 39.8 | 26.8 | 29.0 | 29.7 | 12.0 | 12.3 | |

| PW + L | 0.9 | 3.2 | 51.6 | 45.2 | 4.3 | 1.0 | 7.6 | 4.1 | 9.3 | 5.3 | 40.9 | 27.4 | 25.9 | 30.9 | 11.8 | 11.9 | |

| PW + S | 0.9 | 2.2 | 53.0 | 49.4 | 4.4 | 1.4 | 7.4 | 2.9 | 8.4 | 8.0 | 39.8 | 28.3 | 29.1 | 23.4 | 12.0 | 11.6 | |

| s.e. | 0.06 | 1.02 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.29 | 0.58 | 0.50 | 0.09 | |||||||||

| P-value F | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||||||||

The K:(Na + Mg) ratio of the PW forage was high across treatments (range 6.9–8.1), and the tetany index was double the maximum thresholds recommended for sheep (Table 2b). In comparison, these ratios in the legume species was well below maximum thresholds. The average DCAD for all treatments was four-fold higher than the published maximum threshold (12 mEq/100 g) across all forage components.

The average energy content of forages over the experimental period varied between individual components. The PW + C treatment exceeded the nominal ME for maximum feed efficiency in lamb growth in both the cereal and legume forage components on offer (> 12 MJ/kg DM, NRC 2007), whereas the cereal component of the PW + Min and PW + L treatments were similar to each other and below estimated requirements. Both these forages were lower than the corresponding PW component of the PW + C and PW + S (P < 0.001). Similarly, the energy content of the serradella was 2.5% and 6% lower (P < 0.001) than lucerne and subterranean clover, respectively. All treatments had adequate CP for lamb growth, however there were differences (P < 0.001) between treatments. The cereal components of the PW + C and PW + S were higher in CP, when compared with the PW + Min and PW + L treatments, respectively. The CP of serradella herbage was lower (P < 0.001) than both subterranean clover and lucerne.

Forage on offer and intake by lambs

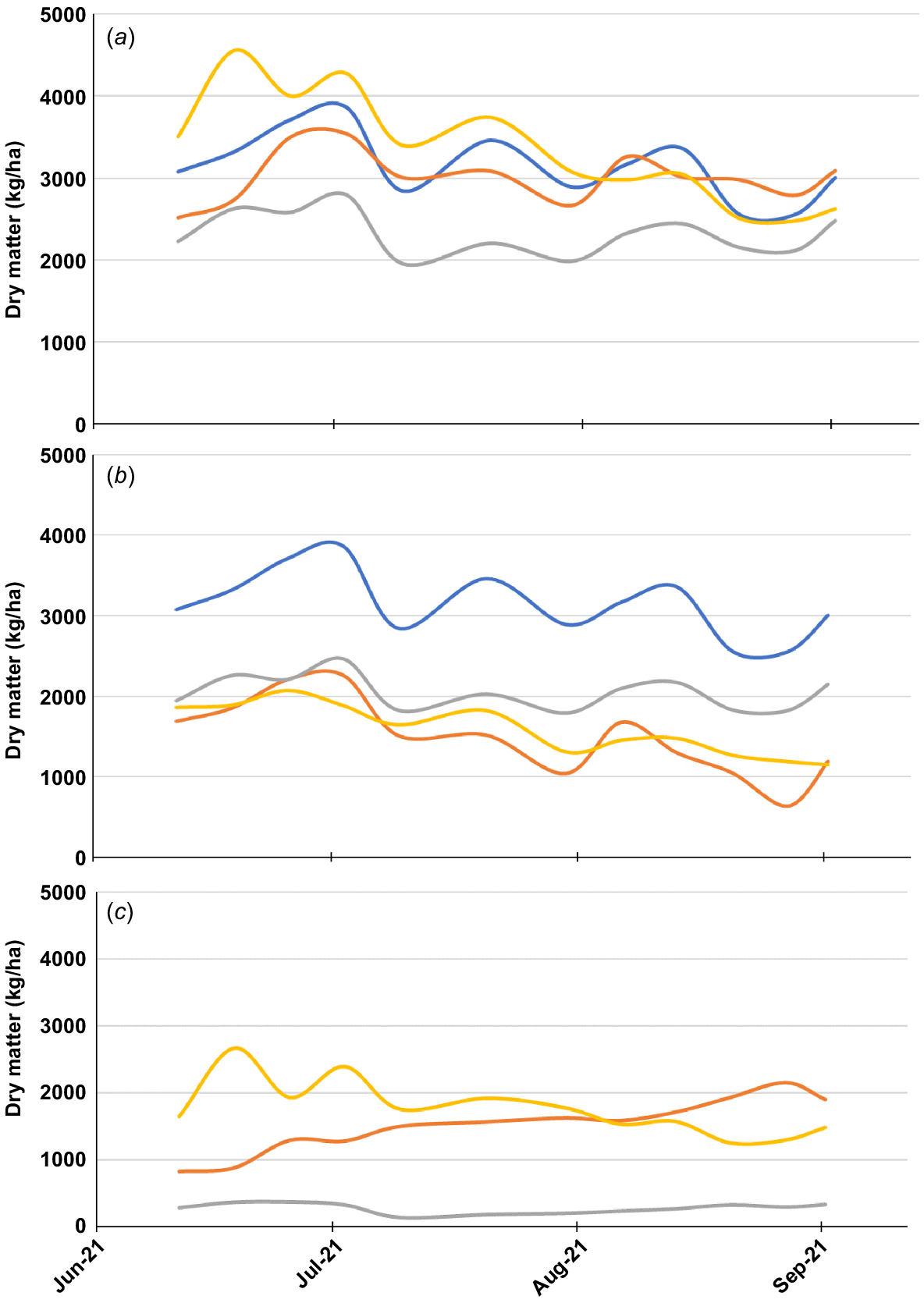

Total forage dry matter available throughout the grazing period was similar between the PW + Min, PW + C and PW + S treatments, averaging 3173 kg/ha over 89 days (Fig. 2a). This was greater than the PW + L treatment (2325 kg/ha; P < 0.001). This was largely driven by the low production of lucerne (277 kg/ha) over the course of the study, compared with subterranean clover (1523 kg/ha) or serradella (1768 kg/ha; Fig. 2c). However, no diet posed a restriction to intake, as total food on offer was above 2000 kg/ha for the duration of the experiment for all forage treatments (Oddy and Allan 2001).

Mean quantity of forage available expressed as (a) total cereal + legume, along with forage components of, (b) cereal and (c) legume for lambs grazing perennial wheat (PW + Min ), perennial wheat + subterranean clover (PW + C

), perennial wheat + subterranean clover (PW + C ), perennial wheat + lucerne (PW + L

), perennial wheat + lucerne (PW + L ) and perennial wheat + serradella (PW + S

) and perennial wheat + serradella (PW + S ).

).

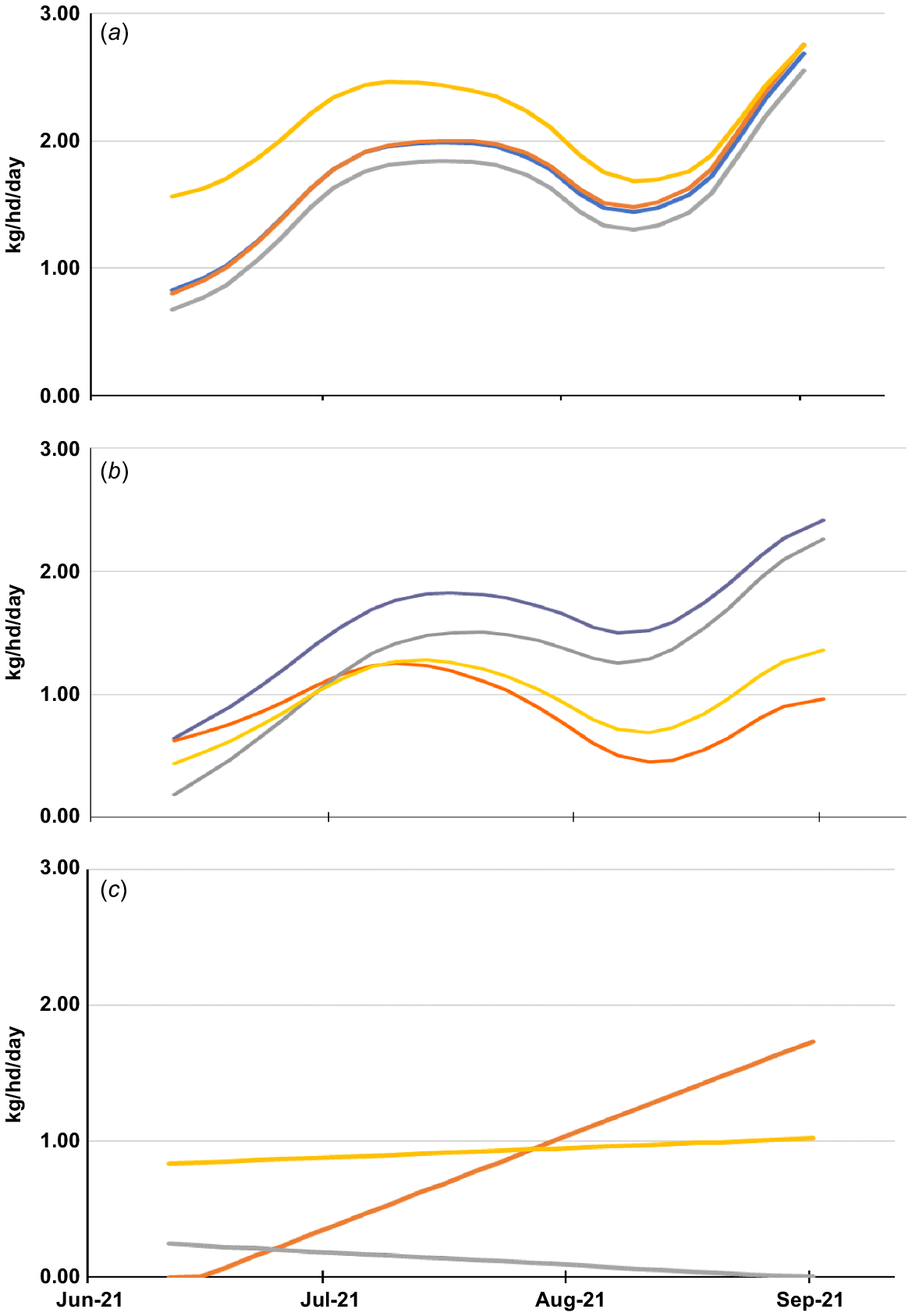

Total dry mater intake was similar between treatments (Fig. 3a) with upward trend in DM intake as the experiment progressed (average intake ranged from 0.85 kg/hd/day at the start to 2.67 kg/hd/day at the end of grazing). However, there were differences in PW dry matter intake between treatments over the course of the experiment (P < 0.05, Table 3 and Fig. 3b). Intake of PW progressively increased over the first 5 weeks of grazing, with each lamb consuming, on average, 50% more PW forage in the PW + Min treatment compared with the PW + C, PW + L and PW + S treatments (Fig. 3b). From the end of July (around day 39) until the end of the experiment, the consumption of PW in the PW + L treatment was 79% higher per lamb (P < 0.05) compared with the PW + C and PW + S treatments. This aligned with a concurrent decrease in the intake of lucerne from 0.24 to 0.14 kg DM/hd/day (Fig. 3c). Serradella consumption was relatively constant, averaging 0.93 kg/hd/day, whereas subterranean clover intake progressively increased over the duration of grazing (range 0–1.73 kg DM/hd/day). Overall, legume intake of each lamb in the PW + C and PW + S was higher (P < 0.001, average 0.875 kg/hd/day) compared with lucerne consumption (average 0.12 kg/hd/day) over the duration of grazing. The higher legume intake in the PW + C and PW + S treatments was associated with a subsequent decrease in the proportion of PW consumed in those treatments (Fig. 3b).

Estimated daily DM intake (kg/hd/day) for (a) total cereal + legume, (b) cereal and (c) legume for lambs grazing perennial wheat (PW + Min ), perennial wheat + subterranean clover (PW + C

), perennial wheat + subterranean clover (PW + C ), perennial wheat + lucerne (PW + L

), perennial wheat + lucerne (PW + L ) and perennial wheat + serradella (PW + S

) and perennial wheat + serradella (PW + S ).

).

| Strata/description | Effect A | NDF B | DDF B | F-value | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total forage intake | ||||||

| Treatment | F | 3 | 271.7 | 1.93 | 0.125 | |

| Measurement date | F | 1 | 271.7 | 14.55 | < 0.001 | |

| Treatment × measurement date | F | 3 | 271.7 | 0.52 | 0.672 | |

| Residual | R | |||||

| Perennial wheat intake | ||||||

| Treatment | F | 3 | 267.6 | 5.23 | < 0.05 | |

| Measurement date | F | 1 | 267.6 | 11.81 | < 0.001 | |

| Treatment × measurement date | F | 3 | 267.6 | 3.07 | < 0.05 | |

| Residual | R | |||||

| Legume intake | ||||||

| Treatment | F | 2 | 210 | 11.22 | < 0.001 | |

| Measurement date | F | 1 | 210 | 6.31 | < 0.05 | |

| Treatment × measurement date | F | 2 | 210 | 7.32 | < 0.001 | |

| Residual | R | |||||

These values should be viewed in conjunction with Fig. 3.

Mineral supplement intake averaged 12.3 g/day/animal (range 1.3–39.3 g) over the duration of the grazing period. Assuming equal parts of lime, Causmag and salt were consumed by each lamb, this equated to the consumption of 1.6 g Ca, 2.5 g Mg and 1.6 g Na per day.

Liveweight gain

Lamb liveweight increased in each treatment over the course of the experiment (Table 4). The final liveweight of ewe lambs that remained for the full grazing period averaged 52.4 kg (range 45.4–59.4 kg). Of the three intercrop treatments, the total liveweight gain, which was the sum of individual lamb liveweight gain in a plot, was higher (P = 0.001) in lambs grazing the PW + C forage, with 29% heavier lambs compared to those grazing in the PW + L treatment, which had the lowest average liveweight gain of all treatments. The total liveweight gain was not statistically different from lambs in the PW + Min, PW + C or PW + S treatments. No clinical signs of metabolic disorders were observed among the lambs during grazing. The mean grazing days per treatment ranged from 372 days for the PW + L treatment, which was lower (P < 0.001) than the highest number of grazing days in the PW + C treatment (463 grazing days, Table 4). The mean number of grazing days was similar between PW + C, PW + S and PW + Min. The calculation of liveweight output revealed an average advantage when PW was intercropped with either subterranean clover or serradella in total liveweight output (range 110–160 kg/ha), compared with when PW was intercropped with lucerne. This was associated with higher liveweight output from the PW + C and PW + S treatments, which were similar to when mineral supplements were provided while grazing PW.

| Grain yield (kg/ha) | HI A | Tillers/m2 | TKW(g) B | Total liveweight gain C (kg) | Grazing days per treatment | Liveweight output D (kg/ha) | Legume DM at anthesis (kg/ha) | NER E | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PW + Min | 1695c | 0.20a | 377.5c | 31.48 | 103.5b | 446b | 684.5b | 0a | ||

| PW + C | 719a | 0.24c | 186.1a | 31.03 | 107.5b | 463c | 710.9b | 1182c | 0.88a | |

| PW + L | 1382b | 0.22b | 250.2b | 32.63 | 83.4a | 372a | 551.5a | 305b | 1.66c | |

| PW + S | 1272b | 0.22b | 223.0b | 32.13 | 99.9b | 446b | 660.9b | 1316c | 1.31b | |

| P-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.001 | > 0.05 | 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.001 | < 0.01 | < 0.001 | |

| l.s.d. (5%) | 193 | 0.01 | 39.3 | n.s. | 10.5 | 15 | 69.7 | 7472 | 0.34 |

Including grain yield and components, along with total liveweight gain from grazing lambs per forage type (kg) or per hectare (kg/ha). Grain yield data determined through whole plot mechanical harvest. Values followed by the same (a, b and c) letter are not significantly different (P > 0.05).

Anthesis dry matter and grain yield components

The effect of grazing on anthesis DM and grain yield is presented in Table 5. Anthesis in the PW on the ungrazed treatment occurred on 22 October 2021 and was delayed in the grazed treatments by 12 days. Anthesis occurred at the same time in the A and B rotation plots. Anthesis DM ranged from 12,702 kg/ha in the ungrazed area of selected plots to 6051 kg in the corresponding plots that had been grazed. Legume DM, measured at PW anthesis, was 64% lower in the grazed compared with the ungrazed areas. Higher amounts of lodging were observed in the ungrazed areas, but there was no difference in grain yield between the grazed and ungrazed areas (P > 0.05). Harvest index and kernel size were higher in the grazed plots (P < 0.01) by 5% and 8% (P < 0.01), respectively, whereas tiller number was unaffected by grazing.

| Anthesis dry matter | Harvest grain parameters | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cereal (kg/ha) | Legume (kg/ha) | Grain yield (kg/ha) | HI A | Tillers/m2 | TKW B | ||

| Rotation A C | 6474a | 752a | 2108 | 0.23b | 218.2 | 33.67b | |

| Rotation B C | 6051a | 227a | 1787 | 0.22b | 240.7 | 32.36b | |

| Ungrazed | 12702a | 1374b | 1962 | 0.15a | 249.1 | 30.58a | |

| P-value D | < 0.001 | < 0.01 | > 0.05 | < 0.001 | > 0.05 | < 0.001 | |

| l.s.d (5%) | 1279.80 | 647.10 | n.s. | 0.02 | n.s. | 1.37 | |

Grain yield from header harvest was lower (P < 0.001) in the PW + C treatment, producing approximately half the amount of grain, with a HI that was 16% higher than the average of the other three treatments (range 0.20–0.22, Table 4). The legume intercrop treatments also had lower tiller/m2 compared with the PW monoculture, due to the reduced number of cereal rows, although the kernel size was similar between all four treatments. All intercrops reduced grain yield by an average of 34% on a per unit area basis (range 719–1382 kg/ha) compared with the PW + Min treatment. The PW + L and PW + S intercrop treatments had 66% and 31% higher grain yield when considered in terms of the PW land share in these treatments, compared with the monoculture PW + Min sward (NER 1.66 and 1.31, respectively).

Discussion

Forage quality and mineral concentration

Synchrony of crop growth and animal requirements for high energy and protein, at a time when other pasture growth is low, has long been an attractive option for the use of early stage vegetative growth in grazing cereals for livestock production (Dove et al. 2002; Dove and Kirkegaard 2014; Masters and Thompson 2016). In the current study, the PW component of all diets on offer proved to be of high quality. Although there was variation in the CP and ME across the diets provided, both CP (which exceeded 20%) and ME (average 11.9 MJ/kg ME) would not have restricted intake or growth of the grazing lambs. Dove et al. (2016) found Ca and Mg concentrations in a significant number of cereal forage samples to be below animal requirements. In contrast, we found the average Ca and Mg concentrations in PW, over the duration of grazing, was adequate for requirements of young, fast-growing lambs (National Research Council 2007). Forage K concentration in PW was above nominal maximum thresholds, coupled with very low Na, similar to the values previously reported by Dove et al. (2016; < 0.016% Na in wheat), which were well below critical requirements for grazing lambs (NRC 2007). The resulting high Tetany Index values and K:Na + Mg ratios of PW suggests the absorption of both Ca and Mg would be impaired in ruminants grazing this forage alone (Refshauge et al. 2022). The addition of legumes to the intercropped treatments provided access to forages that contained concentrations of Ca and Mg that were much higher than requirements, combined with much lower K compared with the pure cereal diet. The Na concentration was above requirements for intake in both subterranean clover and French serradella forages; however, it was lacking in lucerne. Previous investigations have indicated very low levels of Na in PW forage (< 0.005%: (Newell and Hayes 2017; Newell et al. 2020a) which reflect sampling at earlier stages of development compared with the current study.

The interaction between inflows of anions and cations (DCAD) into the rumen can cause shifts in the systemic acid–base equilibrium and have been shown to reduce the ability of sheep to mobilise Ca reserves and retain Ca in the body (Takagi and Block 1991). Low DCAD diets have been shown to aid the homeostatic control of Ca and increase intestinal absorption to maintain plasma Ca in some animals (Block 1984). The relevance of this metric to sheep in an extensive grazing system is still to be resolved (Masters et al. 2019). In the current study, DCAD ratios far exceeded the published threshold in all diets (by a factor of four), indicating that legumes were of little value in lowering DCAD values compared with a pure cereal diet due to their lower S and Cl concentrations. Further investigation is required to assess the metabolic health of the animals in this study, to determine any subclinical mineral deficiencies and whether this was being mediated by the intake of specific legumes compared with the provision of supplements. It is noted that none of the grazing lambs in the current study displayed clinical signs of metabolic disorders.

Animal performance

Although liveweight gains increased for all lambs in the experiment, lambs grazing the PW + L had lower final liveweights compared with all other treatments. This led to much lower total liveweight output in the PW + L treatment compared with PW intercropped with clover or serradella or when mineral supplements where provided. This was due, in part, to the lowering of the stocking rate in this treatment to help maintain feed availability. This reduced the number of grazing days compared with other treatments, which ultimately led to a lower liveweight output. Consequently, total forage intake was similar between all forage treatments across the length of the grazing period (Fig. 3a). Although total forage production was significantly lower in the PW + L treatment, the feed on offer was above 2000 kg/ha across the duration of the experiment, thus providing ample forage for grazing (McGrath et al. 2021a). Lucerne growth was unable to meet the intake requirements of the grazing lambs, which meant by the mid-point of the study, the intake of lucerne was restricted in lambs grazing this treatment. Therefore, lambs in the PW + L treatment were essentially grazing a pure PW diet without any mineral supplement during the latter half of the study. Further investigation of the mineral status of these lambs is required to confirm mineral deficiency of their diet.

Previous studies have shown that liveweight gains were impaired in lambs grazing PW without supplementation and that the addition of lucerne, itself a forage comparatively low in Na, was unable to adequately compensate for the low Na content of PW (Newell et al. 2020a). This has been supported by other experiments in which the provision of Na supplementation of lambs grazing lucerne based diets improved forage intake and increased liveweight (Champness et al. 2021). Furthermore, Newell et al. (2020b) found the supplementation of Na to a PW diet increased dietary intake in late-gestation ewes. As may be expected, the provision of supplements in the PW + Min treatment in the current study increased the intake of PW as a component of the diet compared with the PW + L diet (Fig. 3b), with improved liveweight change compared with the PW + L treatment. The provision of supplemental Na (1.6 g/day) exceeded the daily requirements for the lambs in this study (NRC 2007). Correcting the Na deficiency in cereal forages have also shown an improvement in liveweight gain in other grazing studies (Dove and McMullen 2009), without an improvement in intake. Ultimately, the higher carrying capacity achieved in the PW + Min, PW + C and PW + S is more likely to have been responsible for higher liveweight gains compared with the PW + L treatment, although cannot be decoupled from the Na intake from the different forages.

Grazing is an important driver of N cycling in grassland systems. Up to 60% of the plant N can be recovered through ruminant digestion and returned to the soil in plant-available forms via urine (Floate 1981). This is an important pathway for atmospheric N captured by legumes to be made available to grasses. In the current study the higher amounts of legume biomass consumed in the PW + C and PW + S forages may have led to increased N cycling, perhaps explaining the increased CP content of the PW forage in those treatments. Alternatively, the greater competitive ability of the cereal to acquire soil N compared with the legumes may have allowed greater access to the soil mineral N pool in the intercrops compared to in the higher plant density monoculture (Naudin et al. 2010). However, this would not explain the significantly lower CP of the PW component in the PW + L treatments, where there was less legume biomass, and presumably the PW would be accessing the same soil mineral N pool as in the other intercrop treatments. All forages more than satisfied the CP threshold required by grazing lambs and thus may have had little impact on the difference in changes in liveweight between treatments.

Crop performance

Few studies have examined the effect of grazing on grain yield in PW. In legume intercrops with the perennial grain ‘Kernza’ (Thinopyrum intermedium (Host) Barkworth and Dewey), Dick et al. (2018) found that grazing in the autumn in the year following establishment, led to higher grain yields and HI compared with residue removal or mechanical chopping. This concurs with a similar study by Hunter et al. (2020) where Kernza grain yields and HI were shown to be enhanced by mechanical defoliation and removal compared with non-defoliation. Utilising the greater DM production is an important consideration in the management of PW compared with other annual grazing cereals (Newell and Hayes 2017) and may also assist to stabilise grain yields across growing seasons. It is worth noting that most previous studies evaluating PW grain yields were not grazed or defoliated, except at harvest (Hayes et al. 2012; Larkin et al. 2014; Hayes et al. 2018).

In the current study, grazing of PW had little impact on year 1 grain yields, with similar yields observed in the ungrazed and rotationally grazed treatments. However, grazing delayed anthesis by 12 days. Grazing cereals require the removal of livestock before Zadoks stage Z31 (Zadoks et al. 1974), as grazing at a later stage of development has the potential to remove the growing point, resulting in loss of tillers and yield potential (Harrison et al. 2011a). The later maturity of the PW accession in the current study allowed extended grazing well into spring, before the critical Z31 stage was reached. Delays in anthesis have been reported in other grazing cereal studies (Virgona et al. 2006; Harrison et al. 2011b) and considered to generally have a negative impact in grain only crops, due to grain filling occurring when moisture stress is more likely (Cann et al. 2023). In the current study, HI increased by 50% and grain size (TKW) by 8% in the grazed versus ungrazed treatments. This would indicate a greater capacity to translate accumulated biomass into grain yield in grazed PW crops, a condition aided by the wetter than average spring. Harrison et al. (2011c) found that grazing increased partitioning of accumulated resources to developing wheat spikes under drying soil conditions. The Harrison et al. (2011c) study found that the delay in ontology and water use caused by grazing prolonged the incidence of green leaf area after anthesis, allowing greater photosynthetic activity during kernel development and thereby negating any grain yield decline from grazing.

A major impact on grain yield was the change in row configuration from the PW + Min treatment, with cereal in every drill row, to the alternate drill row configuration which spatially separated PW and legume components. On average, this reduced grain yield by 34% compared with the monoculture PW + Min treatment. This is largely due to the reduction in density of the dominant PW species in the intercrop treatments (Hayes et al. 2024). Mixed row intercropping tends to favour the dominant crop species, whereas separating species into distinct sowing rows favours the subordinate crop species (Chalmers 2014), which can be challenging where grain yield of both species is the imperative function. However, for the current study, separating the PW into alternate drill rows ensured greater DM production from the forage legume (Hayes et al. 2017) to meet the intake requirement of grazing animals. Production from the legumes would likely have been limited in a mixed row configuration, due to fierce interspecific competition by PW, as has been demonstrated in other crops (Hayes et al. 2022; Stott et al. 2023).

The legume produced in the intercrops offers potential for biological N fixation, potentially reducing fertiliser requirements. Peoples et al. (2012) report that on average, ~35 kg N/ha may be fixed for every tonne of legume DM produced, averaged across a large range of species and environments and accounting for N in both roots and shoots. Based on that assumption, the inputs of N from residual legume biomass after grazing would equate to approximately 41, 10 and 46 kg/ha of N for the PW + C, PW + L and PW + S treatments, respectively. Grazing the PW + L treatment early in the establishment year may have compromised lucerne growth in the current study. Given a longer timeframe, the PW + L treatment may have seen higher legume biomass, allowing greater inputs of atmospheric N (Crews et al. 2022), as seedling lucerne is typically less productive than self-regenerating annual legumes. However, in a water limited environment, the spring/summer growth pattern of lucerne may be too competitive with PW compared with a self-regenerating annual legume that avoids competition at that critical time of year (Hayes et al. 2021). The increased dominance of lucerne within a sward over time has also been described by others (Dick et al. 2018).

System output

Most intercropping research has focused on grain production; however, few studies have incorporated both grain and animal production from intercrops. Previous research has shown an advantage with intercrops over a monoculture, where there are multiple products produced from the same area of land, rather than a focus on a single product (Ryan et al. 2018; Li et al. 2023). In the current study, the components of production varied with choice of legume partner in the intercrop. For the current study, it is possible to calculate the grain yield NER by comparing the PW yield with the grain produced from the three legume intercrop treatments, where PW occupies 50% of the sown intercrop area. Here we find NER values of 0.84, 1.63 and 1.50 for the PW + C, PW + L and PW + S treatments, based on their average PW grain yield (Table 4). The values > 1 indicate a grain yield advantage from the intercrop compared with the monoculture. This concurs with a global meta-analysis of grain yield from intercrops, which showed 1.5 t/ha yield advantage on average with intercrops compared with monoculture crop yields (Li et al. 2020). The decrease in grain yield of PW when intercropped with subterranean clover is interesting, as this legume had similar amounts of DM production as serradella when measured at PW anthesis. This may reflect greater complementarity between PW and serradella, compared with subterranean clover. In part, this may be explained by the legume cultivars used. French serradella cv. Margurita is categorised as a medium maturity cultivar (R. Simpson, unpubl. data) that flowers several weeks earlier than the late-maturing Leura subterranean clover. It is possible that the later maturing legume exhibited a higher level of competition for resources later in spring at the time of grain fill of the PW, compared with the French serradella cultivar that had senesced several weeks earlier. This is further supported by the lower tiller number of PW when intercropped with clover.

While the comparative grain yield was higher in the PW + L and PW + S treatments (NER > 1 compared to PW monoculture), total liveweight output was generally higher in the PW + C treatment and similar to the results for the PW + Min and PW + S treatments. The PW + C and PW + S treatments had higher contributions of legume biomass than the other treatments, which would equate to more biological N fixation. The benefit of this would need to be monitored over a longer period than in the current study to ascertain the productivity benefit.

By accounting for grazing days, the total lamb production across intercropped treatments (range 551.53–710.9 kg/ha) was in line with similar studies where lambs grazed wheat with provision of supplement (104–566 kg/ha) (McGrath et al. 2021b). McGrath et al. (2021b) concluded that finishing weaned lambs on grazing crops was profitable and mitigated production risk. The current study indicates that lamb production from grazing perennial grain polycultures is feasible and supports moderate grain yields, in a perennial dual-purpose cropping system.

Conclusion

This study is one of the first to demonstrate the grazing potential of an intercropped perennial wheat system. Intercropping with legume species, such as subterranean clover and French serradella, enabled higher grazing days and greater liveweight change in grazing lambs, compared with where PW was grown in the absence of a productive legume. Lower liveweight gain occurred in lambs grazing the PW + L treatment, where lucerne biomass was low, limiting grazing potential. Potentially, there was some response in liveweight gain from the improved mineral nutrition in the PW + Min, PW + C and PW + S treatments compared with PW + L, where both species are deficient in Na; however, this requires further investigation.

Grain yields were not affected by grazing, although were reduced by intercropping. If high grain yield was favoured in the production system, then a perennial wheat monoculture with the provision of supplements would meet producer requirements. However, the comparative improvement in PW grain yield (NER) from intercropping with compatible legume species, along with increased stocking rates, meat production and resource provision from legume biomass, adds productive components to a multifunctional, dual-purpose perennial grain system.

Declaration of funding

Funding was provided from the Livestock Productivity Partnership – a collaboration between NSW Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development (NSW DPIRD) and Meat and Livestock Australia Donor Company (Project P. PSH.1036. Novel Dual Purpose Perennial Cereals for Grazing).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the following NSW DPIRD staff for their contributions to this experiment: Lance Troy, Susan Langfield, Kylie Cooley, Rhianna Mactaggart, Andrew Price, Matthew Kerr, Jackie Chapman, George Carney, Phil Goodacre, and Tracy Lamb.

References

Atabo JA, Umaru TM (2015) Assessing the land equivalent ratio (LER) and stability of yield of two cultivars of sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L. Moench)-Soyabean (Glycine max L. Merr) to row intercropping system. Journal of Biology, Agriculture and Healthcare 5(18), 144-149.

| Google Scholar |

Bell LW (2013) Economics and system applications for perennial grain crops in dryland farming systems in Australia. In ‘Perennial crops for food sedurity. Proceedings of FAO expert workshop’, 28–30 August, Rome. (Eds C Batello, L Wade, S Cox, N Pogna, A Bozzini, J Choptiany) pp. 169–186. (FAO: Rome)

Bell LW, Moore AD, Kirkegaard JA (2014) Evolution in crop–livestock integration systems that improve farm productivity and environmental performance in Australia. European Journal of Agronomy 57, 10-20.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Betencourt E, Duputel M, Colomb B, Desclaux D, Hinsinger P (2012) Intercropping promotes the ability of durum wheat and chickpea to increase rhizosphere phosphorus availability in a low P soil. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 46, 181-190.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Block E (1984) Manipulating dietary anions and cations for prepartum dairy cows to reduce incidence of milk fever. Journal of Dairy Science 67(12), 2939-2948.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Cann DJ, Hunt JR, Porker KD, Harris FAJ, Rattey A, Hyles J (2023) The role of phenology in environmental adaptation of winter wheat. European Journal of Agronomy 143, 126686.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Champness MR, McCormick JI, Bhanugopan MS, McGrath SR (2021) Sodium deficiency in lucerne (Medicago sativa) forage in southern Australia and the effect of sodium and barley supplementation on the growth rate of lambs grazing lucerne. Animal Production Science 61(11), 1170-1180.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Chapagain T, Riseman A (2014) Barley–pea intercropping: effects on land productivity, carbon and nitrogen transformations. Field Crops Research 166, 18-25.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Coombes N (2020) DiGGer: DiGGer design generator under correlation and blocking. R Package Version 1.0.5. Available at http://nswdpibiom.org/austatgen/software

Cox CM, Murray TD, Jones SS (2002) Perennial wheat germ plasm lines resistant to eyespot, Cephalosporium stripe, and wheat streak mosaic. Plant Disease 86(9), 1043-1048.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Crews TE, Blesh J, Culman SW, Hayes RC, Jensen ES, Mack MC, Peoples MB, Schipanski ME (2016) Going where no grains have gone before: from early to mid-succession. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 223, 223-238.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Crews TE, Carton W, Olsson L (2018) Is the future of agriculture perennial? Imperatives and opportunities to reinvent agriculture by shifting from annual monocultures to perennial polycultures. Global Sustainability 1, e11.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Crews TE, Kemp L, Bowden JH, Murrell EG (2022) How the nitrogen economy of a perennial cereal-legume intercrop affects productivity: can synchrony be achieved? Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 6, 755548.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Darch T, McGrath SP, Lee MRF, Beaumont DA, Blackwell MSA, Horrocks CA, Evans J, Storkey J (2020) The mineral composition of wild-type and cultivated varieties of pasture species. Agronomy 10(10), 1463.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Daryanto S, Fu B, Zhao W, Wang S, Jacinthe P-A, Wang L (2020) Ecosystem service provision of grain legume and cereal intercropping in Africa. Agricultural Systems 178, 102761.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Dick C, Cattani D, Entz MH (2018) Kernza intermediate wheatgrass (Thinopyrum intermedium) grain production as influenced by legume intercropping and residue management. Canadian Journal of Plant Science 98(6), 1376-1379.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Dove H, Kirkegaard J (2014) Using dual-purpose crops in sheep-grazing systems. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 94(7), 1276-1283.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Dove H, McMullen KG (2009) Diet selection, herbage intake and liveweight gain in young sheep grazing dual-purpose wheats and sheep responses to mineral supplements. Animal Production Science 49(10), 749-758.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Dove H, Holst P, Stanley D, Flint P (2002) Grazing value of dual-purpose winter wheats for young sheep. Proceedings of the Australian Society of Animal Production 24, 53-56.

| Google Scholar |

Dove H, Kirkegaard JA, Kelman WM, Sprague SJ, McDonald SE, Graham JM (2015) Integrating dual-purpose wheat and canola into high-rainfall livestock systems in south-eastern Australia. 2. Pasture and livestock production. Crop & Pasture Science 66(4), 377-389.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Dove H, Masters DG, Thompson AN (2016) New perspectives on the mineral nutrition of livestock grazing cereal and canola crops. Animal Production Science 56(8), 1350-1360.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Fletcher AL, Kirkegaard JA, Peoples MB, Robertson MJ, Whish J, Swan AD (2016) Prospects to utilise intercrops and crop variety mixtures in mechanised, rain-fed, temperate cropping systems. Crop & Pasture Science 67(12), 1252-1267.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Floate MJS (1981) Effects of grazing by large herbivores on nitrogen cycling in agricultural ecosystems. Ecological Bulletins 33, 585-601.

| Google Scholar |

Harris D, Natarajan M, Willey RW (1987) Physiological basis for yield advantage in a sorghum/groundnut intercrop exposed to drought. 1. Dry-matter production, yield, and light interception. Field Crops Research 17(3–4), 259-272.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Harrison MT, Evans JR, Dove H, Moore AD (2011a) Dual-purpose cereals: can the relative influences of management and environment on crop recovery and grain yield be dissected? Crop & Pasture Science 62(11), 930-946.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Harrison MT, Evans JR, Dove H, Moore AD (2011b) Recovery dynamics of rainfed winter wheat after livestock grazing 1. Growth rates, grain yields, soil water use and water-use efficiency. Crop & Pasture Science 62(11), 947-959.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Harrison MT, Evans JR, Dove H, Moore AD (2011c) Recovery dynamics of rainfed winter wheat after livestock grazing 2. Light interception, radiation-use efficiency and dry-matter partitioning. Crop & Pasture Science 62(11), 960-971.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hayes RC, Dear BS, Orchard BA, Peoples M, Eberbach PL (2008) Response of subterranean clover, balansa clover, and gland clover to lime when grown in mixtures on an acid soil. Australian Journal of Agricultural Research 59(9), 824-835.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hayes RC, Newell MT, DeHaan LR, Murphy KM, Crane S, Norton MR, Wade LJ, Newberry M, Fahim M, Jones SS, Cox TS, Larkin PJ (2012) Perennial cereal crops: an initial evaluation of wheat derivatives. Field Crops Research 133, 68-89.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hayes RC, Newell MT, Crews TE, Peoples MB (2017) Perennial cereal crops: an initial evaluation of wheat derivatives grown in mixtures with a regenerating annual legume. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems 32(3), 276-290.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hayes RC, Wang S, Newell MT, Turner K, Larsen J, Gazza L, Anderson JA, Bell LW, Cattani DJ, Frels K, Galassi E, Morgounov AI, Revell CK, Thapa DB, Sacks EJ, Sameri M, Wade LJ, Westerbergh A, Shamanin V, Amanov A, Li GD (2018) The performance of early-generation perennial winter cereals at 21 sites across four continents. Sustainability 10(4), 1124.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hayes RC, Newell MT, Pembleton KG, Peoples MB, Li GD (2021) Sowing configuration affects competition and persistence of lucerne (Medicago sativa) in mixed pasture swards. Crop & Pasture Science 72, 707-722.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hayes RC, Newell MT, Swan AD, Peoples MB, Pembleton KG, Li GD (2022) Consequences of changing spatial configuration at sowing in the transitions between crop and pasture phases. Journal of Agronomy and Crop Science 208(3), 394-412.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hayes RC, Li GD, Smith RW, Peoples MB, Rawnsley RP, Newell MT, Pembleton KG (2024) Prospects for improving productivity and composition of mixed swards in semi-arid environments by separating species in drill rows – a review. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 373, 109131.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hunter MC, Sheaffer CC, Culman SW, Jungers JM (2020) Effects of defoliation and row spacing on intermediate wheatgrass I: Grain production. Agronomy Journal 112(3), 1748-1763.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Juknevičius S, Sabienė N (2007) The content of mineral elements in some grasses and legumes. Ekologija 53(1), 44-52.

| Google Scholar |

Kemp A, ‘t Hart ML (1957) Grass tetany in grazing milking cows. Netherlands Journal of Agricultural Science 5(1), 4-17.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Khanal U, Stott KJ, Armstrong R, Nuttall JG, Henry F, Christy BP, Mitchell M, Riffkin PA, Wallace AJ, McCaskill M, Thayalakumaran T, O’Leary GJ (2021) Intercropping – evaluating the advantages to broadacre systems. Agriculture 11(5), 453.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Larkin PJ, Newell MT, Hayes RC, Aktar J, Norton MR, Moroni SJ, Wade LJ (2014) Progress in developing perennial wheats for grain and grazing. Crop & Pasture Science 65(11), 1147-1164.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Lee MA (2018) A global comparison of the nutritive values of forage plants grown in contrasting environments. Journal of Plant Research 131, 641-654.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Lefroy EC, Stirzaker RJ (1999) Agroforestry for water management in the cropping zone of southern Australia. Agroforestry Systems 45, 277-302.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Li C, Hoffland E, Kuyper TW, Yu Y, Zhang C, Li H, Zhang F, van der Werf W (2020) Syndromes of production in intercropping impact yield gains. Nature Plants 6, 653-660.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Li C, Stomph T-J, Makowski D, Li H, Zhang C, Zhang F, van der Werf W (2023) The productive performance of intercropping. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 120(2), e2201886120.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Masters DG (2018) Practical implications of mineral and vitamin imbalance in grazing sheep. Animal Production Science 58(8), 1438-1450.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Masters DG, Thompson AN (2016) Grazing crops: implications for reproducing sheep. Animal Production Science 56(4), 655-668.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Masters DG, Hancock S, Refshauge G, Robertson SM, McGrath S, Bhanugopan M, Friend MA, Thompson AN (2019) Mineral supplements improve the calcium status of pregnant ewes grazing vegetative cereals. Animal Production Science 59(7), 1299-1309.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

McGrath SR, Pinares-Patiño CS, McDonald SE, Kirkegaard JA, Simpson RJ, Moore AD (2021a) Utilising dual-purpose crops in an Australian high-rainfall livestock production system to increase meat and wool production. 1. Forage production and crop yields. Animal Production Science 61, 1062-1073.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

McGrath SR, Behrendt R, Friend MA, Moore AD (2021b) Utilising dual-purpose crops effectively to increase profit and manage risk in meat production systems. Animal Production Science 61(11), 1049-1061.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Naudin C, Corre-Hellou G, Pineau S, Crozat Y, Jeuffroy M-H (2010) The effect of various dynamics of N availability on winter pea–wheat intercrops: crop growth, N partitioning and symbiotic N2 fixation. Field Crops Research 119(1), 2-11.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Newell MT, Hayes RC (2017) An initial investigation of forage production and feed quality of perennial wheat derivatives. Crop & Pasture Science 68(12), 1141-1148.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Newell MT, Holman BWB, Refshauge G, Shanley AR, Hopkins DL, Hayes RC (2020a) The effect of a perennial wheat and lucerne biculture diet on feed intake, growth rate and carcass characteristics of Australian lambs. Small Ruminant Research 192, 106235.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Peoples MB, Brockwell J, Hunt JR, Swan AD, Watson L, Hayes RC, Li GD, Hackney B, Nuttall JG, Davies SL, Fillery IRP (2012) Factors affecting the potential contributions of N2 fixation by legumes in Australian pasture systems. Crop and Pasture Science 63, 759-786.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Provenza FD, Villalba JJ, Dziba LE, Atwood SB, Banner RE (2003) Linking herbivore experience, varied diets, and plant biochemical diversity. Small Ruminant Research 49(3), 257-274.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Refshauge G, Newell MT, Hopkins DL, Holman BWB, Morris S, Hayes RC (2022) The plasma and urine mineral status of lambs offered diets of perennial wheat or annual wheat, with or without lucerne. Small Ruminant Research 209, 106639.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ryan MR, Crews TE, Culman SW, DeHaan LR, Hayes RC, Jungers JM, Bakker MG (2018) Managing for multifunctionality in perennial grain crops. BioScience 68(4), 294-304.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Smith GS, Middleton KR, Edmonds AS (1978) A classification of pasture and fodder plants according to their ability to translocate sodium from their roots into aerial parts. New Zealand Journal of Experimental Agriculture 6(3), 183-188.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Sprague SJ, Kirkegaard JA, Bell LW, Seymour M, Graham J, Ryan M (2018) Dual-purpose cereals offer increased productivity across diverse regions of Australia’s high rainfall zone. Field Crops Research 227, 119-131.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Stott KJ, Wallace AJ, Khanal U, Christy BP, Mitchell ML, Riffkin PA, McCaskill MR, Henry FJ, May MD, Nuttall JG, O’Leary GJ (2023) Intercropping-towards an understanding of the productivity and profitability of dryland crop mixtures in Southern Australia. Agronomy 13(10), 2510.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Takagi H, Block E (1991) Effects of various dietary cation-anion balances on response to experimentally induced hypocalcemia in sheep. Journal of Dairy Science 74(12), 4215-4224.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Tautges NE, Jungers JM, DeHaan LR, Wyse DL, Sheaffer CC (2018) Maintaining grain yields of the perennial cereal intermediate wheatgrass in monoculture v. bi-culture with alfalfa in the Upper Midwestern USA. The Journal of Agricultural Science 156(6), 758-773.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Virgona JM, Gummer FAJ, Angus JF (2006) Effects of grazing on wheat growth, yield, development, water use, and nitrogen use. Australian Journal of Agricultural Research 57(12), 1307-1319.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Wheeler DM, Dodd MB (1995) Effect of aluminium on yield and plant chemical concentrations of some temperate legumes. Plant and Soil 173, 133-145.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Zadoks JC, Chang TT, Konzak CF (1974) A decimal code for the growth stages of cereals. Weed Research 14(6), 415-421.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |