Supporting primary care practitioners to promote dementia risk reduction in Australian general practice: outcomes of a cross-sectional, non-randomised implementation pilot study

Kali Godbee A * , Victoria J. Palmer A B , Jane M. Gunn B C , Nicola T. Lautenschlager B D E and Jill J. Francis F GA

B

C

D

E

F

G

Abstract

Primary care practitioners worldwide are urged to promote dementia risk reduction as part of preventive care. To facilitate this in Australian primary care, we developed the Umbrella intervention, comprising a waiting room survey and patient information cards for use in consultations. Educational and relational strategies were employed to mitigate implementation barriers.

In this cross-sectional, non-randomised implementation study within the South East Melbourne Primary Health Network, we employed mixed-methods outcome evaluation. Antecedent outcomes (acceptability, appropriateness, and feasibility) and actual outcomes (adoption, penetration, and fidelity) were assessed from the perspective of primary care practitioners and patients.

Five practices piloted the intervention and implementation strategies, including 16 primary care practitioners engaging with 159 patients. The Umbrella intervention was deemed acceptable, appropriate, and feasible, but penetration was limited. Approximately half of eligible primary care practitioners used the intervention, with moderate fidelity. Engagement with implementation strategies was similarly limited. While most strategies were well-received, improvements in online peer discussions and staff readiness were desired.

The Umbrella intervention is a viable approach to promoting dementia risk reduction in Australian general practice, supported by educational and relational strategies. Stakeholder-informed refinements to enhance uptake are recommended before advancing to a definitive trial.

Keywords: dementia, general practice, general practice nurses, general practitioners, Implementation Outcomes Framework, implementation science, pilot study, preventive health, primary care, risk reduction.

Background

Dementia is a global health priority, with modifiable risk factors including hypertension, high cholesterol, smoking, obesity, depression, physical inactivity, diabetes, hearing impairment, vision loss, less education, low social contact, excessive alcohol consumption, traumatic brain injury, and air pollution (Livingston et al. 2024). Strategies such as awareness-raising campaigns, free online courses, and environmental manipulation aim to reduce dementia at the population level. At the individual level, primary care practitioners (PCPs) are urged to promote dementia risk reduction (DRR) as part of preventive care. PCPs such as general practitioners (GPs) and general practice nurses can offer tailored education and support to a large proportion of at-risk individuals (Godbee 2024). A recent scoping review outlined key actions for promoting DRR in primary care (Godbee et al. 2022), yet Australian PCPs are not yet consistently practising them (Zheng et al. 2021; Godbee 2024). PCPs may benefit from support to change their clinical practice (Mostofian et al. 2015).

Implementation research is the scientific inquiry into what, why, and how evidence-based practices work in real world settings, as well as improving their systematic uptake. The core components of an implementation process are (1) the intervention (or ‘intended change’), (2) the context, and (3) implementation strategies (Huybrechts et al. 2021). This pilot study aimed to assess the implementation outcomes of an intervention for promoting DRR in the context of Australian general practice that was supported by implementation strategies focussed on education and developing stakeholder inter-relationships.

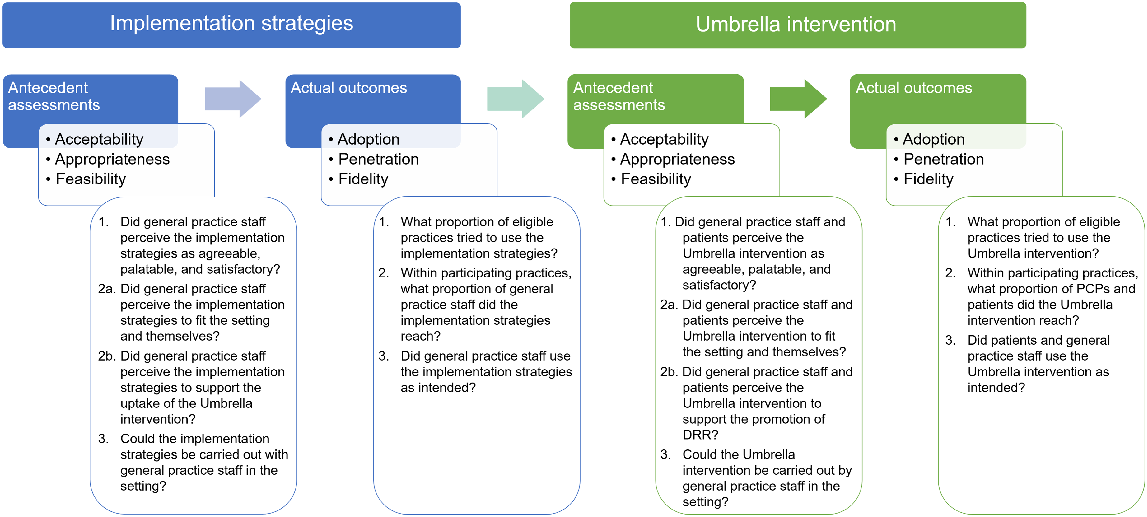

Implementation outcomes are conceptually distinct from patient outcomes and health service outcomes. Implementation outcomes can be classified as either actual implementation outcomes or antecedent assessments (Proctor et al. 2011; Damschroder et al. 2022). Actual outcomes pertain to the current or past success/failure of implementation, assessable only after implementation is attempted. These include the decision to use the innovation (i.e. adoption), use of the intervention as intended (i.e. fidelity, penetration), and sustained delivery over time (i.e. sustainment). In contrast, antecedent assessments can be made before, during, and after implementation to predict or explain actual implementation outcomes. Antecedent outcomes include acceptability, appropriateness, cost, feasibility, and sustainability.

The pilot study aimed to assess actual implementation outcomes and antecedent assessments for a DRR intervention and implementation strategies, as depicted in Fig. 1. Theoretically, each set of outcomes can partially predict or explain the following set of outcomes. For instance, if the implementation strategies are only feasible for certain PCPs, they might have limited penetration, resulting in only some PCPs adopting the intervention. The findings of the pilot study are presented according to the Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies (StaRI) (Pinnock et al. 2017).

Methods

Study design

This was a cross-sectional, non-randomised implementation study in five Australian general practices. The Umbrella intervention and implementation strategies were grounded in theory and evidence with high face validity and minimal risk. The study was conducted within existing practices and workflows, allowing concomitant care and interventions. The evaluation focused on implementation outcomes, not clinical treatment outcomes (Proctor et al. 2011), and therefore was not prospectively registered.

Primary and secondary outcomes

The primary outcomes (rightmost in Fig. 1) comprised adoption, fidelity, and penetration of the Umbrella intervention (Damschroder et al. 2022). The three preceding sets of outcomes were secondary outcomes. Each outcome was linked to research questions, as shown in Fig. 1. We examined the perspective of practice managers (PMs), PCPs, and patients regarding outcomes of the Umbrella intervention, while outcomes of the implementation strategies were focused exclusively on the perspectives of PMs and PCPs.

Participants

General practices were eligible to participate if they were attended by at least 25 patients aged ≥40 years daily, registered for the Practice Incentives Program Quality Improvement (PIP-QI) incentive (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2021), and located within the South East Melbourne Primary Health Network (PHN) catchment. At the time of the study, this catchment encompassed 479 general practices (approximately 252 registered for the PIP-QI incentive), 1938 GPs, and a population of approximately 1.5 million individuals. Three-quarters of adults in the catchment had ≥1 dementia risk factor (current smoker, high-risk alcohol consumption, obesity, and/or insufficient physical activity) (Public Health Information Development Unit 2019).

Within practices, all GPs, general practice nurses, PMs, and reception staff were eligible to participate, along with patients aged between 40 and 64 years. Recruited patients who indicated ≥1 dementia risk factor on the waiting room survey were eligible to participate in a telephone interview.

Recruitment occurred through the South East Melbourne PHN between October and December 2019 using newsletters and network meetings. The implementation facilitator (first author, KG) explained the study to interested PMs and sought consent for the initial educational outreach visit. There was no a priori restriction on the number of practices that could participate in the study.

Practices with three or more participating PCPs received A$500 reimbursement. Participating in the pilot study fulfilled the requirements for sites to receive the PIP-QI incentive. Interviewed patients received a A$20 gift voucher. Individual PCPs were not reimbursed.

The Umbrella intervention

The intervention was named for its central premise: DRR is like putting up an umbrella of healthy behaviours to protect your brain. The intervention was based on guidelines for promoting DRR in primary care, barriers and facilitators to promoting DRR in Australian primary care, existing evidence for supporting preventive care, and stakeholder input (Godbee 2024).

The Umbrella intervention involved a waiting room survey, patient information cards, and suggested PCP actions. The waiting room survey asked about behaviours associated with reduced risk of dementia (e.g. smoking, nutrition, alcohol consumption, physical activity). Patients aged 40–64 years completed the survey, and selected a priority area and rated it in terms of importance and confidence. The PCP then reviewed and discussed the patient’s responses, discussed DRR using relevant patient information cards, provided brief motivational interviewing, made a plan with the patient to address personal risk factors, signposted the patient to additional support, and/or arranged follow-up. The behaviours could be performed across multiple appointments as clinically appropriate.

Implementation strategies

Implementation strategies were targeted at barriers to promoting DRR in general practice in order to support PCPs to use the Umbrella intervention. We blended educational strategies and strategies to develop stakeholder inter-relationships; both types of strategies are important and feasible methods to support practice change (Waltz et al. 2015).

The implementation approach incorporated two consecutive 4-week cycles. A single ‘champion’ PCP used the Umbrella intervention in the first cycle (supported by an implementation facilitator); all participating PCPs joined in the second cycle. Each cycle began with an educational outreach visit from the implementation facilitator (KG) in which educational materials were distributed and explained, followed by a consensus discussion involving the implementation facilitator, PM, and PCPs about whether and how to proceed. Throughout implementation, participating PCPs across practices shared their experiences and suggestions in an online peer discussion. The implementation facilitator moderated the discussion and provided information and resources as requested. PMs, PCPs, and reception staff could access educational materials on a project website. The implementation approach was adaptable based on PCP feedback.

Procedures

The study took place between January and March 2020. Participating sites agreed to use the Umbrella intervention and implementation strategies as described. All study materials are listed in Table 1 and provided in the Supplementary material.

| Umbrella intervention | Implementation strategies | Outcome data collection | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Waiting room survey | Reception notice | Practice assessment tool | |

| Patient information cards | Educational materials for PCPs | Staff survey regarding implementation barriers | |

| Change plan template | Lego® model of a general practice | Patient interview | |

| Group meeting discussion guides A | PM interview | ||

| Champion role-play interview guide A | Facilitator field journal | ||

| Online peer discussion A |

Data on outcomes were gathered through on-site visits, analysis of the content of online peer group discussions, website usage metrics, and telephone and video interviews.

The implementation facilitator visited sites fortnightly to collect outcome data, replenish materials, provide technical and coaching support, and populate a field journal with observations pertinent to study outcomes. Total visits to the project website by PMs, PCPs, and receptionists were counted. To help assess appropriateness of the intervention and implementation strategies, PMs described their practices using the Practice Assessment Tool and staff completed a survey about barriers to promoting DRR that were identified in previous research (Godbee et al. 2019, 2020, 2021; Zheng et al. 2021). Consenting patients were interviewed by telephone in the week following their PCP appointment, and PMs were interviewed by video at the end of the study. These semi-structured interviews sought participants’ perspectives on the acceptability, appropriateness, and feasibility of the Umbrella intervention. The patient interview guide underwent prior review and refinement by a panel of healthcare consumers involved in developing the intervention; the PM interview guide was not reviewed prior to the current pilot study.

Analysis

Actual outcomes (adoption, fidelity, penetration) were quantified using proportions. Descriptive statistics were generated using Microsoft Excel (ver. 2302, Microsoft Corporation, https://office.microsoft.com/excel). Fidelity and penetration proportions were categorised as low (below 50%), moderate (50–80%), or high (above 80%) following precedents in the literature (e.g. Toomey et al. 2017). For adoption, a lower threshold was employed because the Umbrella intervention and implementation strategies were untested innovations. According to Diffusion of Innovation Theory (Rogers 2003), innovations are adopted in the first instance by 2.5% of individuals in a system. These so-called ‘innovators’ are typically venturesome pioneers who are interested in new ideas, willing to take risks, and able to cope with a high degree of uncertainty about an innovation at the time it is adopted (Rogers 2003). Therefore, we expected up to 2.5% of eligible practices to adopt the intervention and implementation strategies in the pilot study. Adoption was classified as low (below 50% of 2.5%), moderate (50–80% of 2.5%), or high (above 80% of 2.5%).

Antecedent assessments (acceptability, appropriateness, feasibility) drew on qualitative data analysed using a directed content analysis method (Hsieh and Shannon 2005). We developed a codebook from the Implementation Outcomes Framework (Proctor et al. 2011) and the research questions (Fig. 1). Field notes, discussion board posts, and transcripts of all group meetings and interviews were imported into Dedoose computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software (ver. 9.0.107, SocioCultural Research Consultants, https://www.dedoose.com/).

Data were coded by the first author according to the outcome, implementation component (intervention or implementation strategies), and stakeholder perspective (general practice staff or patients). Potential codes derived from the data were discussed with coauthors for interpretation and refinement. Examples were added to the codebook to enable coauthor review and ensure consistent application of codes over time. Reflexivity was maintained throughout the coding process by continually reflecting on the researchers’ assumptions, biases, and potential influences on analysis. The analysis was displayed in a matrix, with outcomes from each perspective plotted against implementation components. Coauthors examined the matrix and categorised outcomes as low, moderate, high, or mixed, based on consensus discussions and consideration of the relevant literature.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the University of Melbourne Human Ethics Advisory Group (Ethics ID 1955339). General practice staff provided written informed consent. Opt-out consent was employed for patients completing waiting room surveys. Interviewed patients provided audio-recorded verbal consent.

Results

Recruitment

Staff from 17 eligible practices expressed interest in participating in the study. PMs from eight practices met with the implementation facilitator and five sites consented to take part. Reasons that sites declined to take part included being too busy and lack of interest. Three of the five participating practices were small (fewer than 2500 active patients). Together, participating sites comprised 66 staff (four PMs, 35 PCPs, and 27 reception staff), and approximately 4563 patients aged between 40 and 64 years. Characteristics of participating sites, staff, and patients are described in the Supplementary material.

Actual outcomes

Sixteen PCPs (16/35, 48%) attended the initial outreach visit and consensus discussion. One PCP declined further participation and three additional PCPs agreed to deliver the intervention without attending the initial outreach visit. In total, 18 PCPs (18/35, 51%) delivered the intervention to 159 patients (159/4563, 3%) across five sites.

The calculation of actual outcomes and the rationale for the ratings are summarised in Table 2. For the Umbrella intervention, there was moderate adoption with moderate to high fidelity, but penetration was low. For the implementation strategies, adoption and penetration were moderate, but fidelity was mixed. Additional evidence supporting the ratings is provided in the Supplementary material.

| Outcome | Calculation | Rating | Rationale for rating | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Umbrella intervention | ||||

| Adoption | The number of practices that were willing to participate in the pilot study divided by the total number of practices eligible to participate in the pilot study. | Moderate | 5/252 = 2% | |

| Low: <1.25%. Moderate: 1.25–2%. High: >2% | ||||

| Penetration | 1. Within participating practices, the number of patients who completed the waiting room survey divided by the total number of patients eligible to complete the waiting room survey. | Low | 1. Among patients: 159/4563 = 3.5% (range 1–7%) | |

| 2. Within participating practices, the number of PCPs who agreed to promote DRR as part of the Umbrella intervention divided by the total number of PCPs. | 2. Among PCPs: 18/35 = 51% (range 38–100%) | |||

| 3. Within participating practices, the number of reception staff who promoted DRR as part of the Umbrella intervention divided by the total number of reception staff. | 3. Among reception staff: A 12/27 = 44% (range 10–100%) | |||

| Low: <50%. Moderate: 50–80%. High: >80% | ||||

| Fidelity | 1. The number of waiting room surveys completed correctly divided by the total number of waiting room surveys returned. | Moderate to high | 1. Waiting room surveys: B 123/159 = 77% | |

| 2. The number of dementia patient information cards that were removed from PCPs’ kits divided by the total number of waiting room surveys returned. | 2. Patient information cards: C 117/130 = 90% | |||

| 3. The number of interviewed patients who recalled a discussion about dementia divided by the number of interviewed patients. | 3. Patient recall of the intervention: 11/16 = 67% | |||

| 4. The number of PCPs who actually used the intervention divided by the number of PCPs who agreed to use the intervention. | 4. PCP use of the intervention: 16/18 = 89% | |||

| Low: <50%. Moderate: 50–80%. High: >80% | ||||

| Implementation strategies | ||||

| Adoption | The number of practices that were willing to participate in the pilot study divided by the total number of practices eligible to participate in the pilot study. | Moderate | 5/252 = 2% | |

| Low: <1.25%. Moderate: 1.25–2%. High: >2% | ||||

| Penetration | Within participating practices, the number of Practice Managers and PCPs who engaged in the implementation strategies divided by the total number of PMs and PCPs. | Moderate | 21/40 = 52% (range 31–80%) D | |

| Low: <50%. Moderate: 50–80%. High: >80% | ||||

| Fidelity | 1. The number of group meetings conducted as intended divided by the total number of group meetings. | Mixed | 1. Conduct of group meetings: 10/10 = 100% | |

| 2. The number of PMs and PCPs who attended both group meetings divided by the number of PMs and PCPs who attended the first group meeting. | 2. Staff attendance at both group meetings: 15/20 = 75% | |||

| 3. The number of practices in which PMs and champions attended the second group meeting divided by the total number of practices. | 3. PM and champion attendance at the second group meeting: 2/5 = 40% | |||

| 4. The number of champions who participated in the champion-only role-play interview divided by the total number of champions. | 4. Champion participation in a role-play interview: 5/5 = 100% | |||

| 5. The number of PCPs who contributed to the online peer discussion divided by the number of PCPs who used the Umbrella intervention. | 5. PCP participation in the online peer discussion: E 6/16 = 38% | |||

| Low: <50%. Moderate: 50–80%. High: >80% | ||||

Antecedent assessments

Ratings and rationales for the antecedent assessments are summarised in Table 3. The Umbrella intervention was moderately to highly acceptable, highly appropriate, and moderately feasible. Of the patients interviewed, 14/16 patients (88%) thought the Umbrella intervention should be offered to all patients aged 40–64 in general practice. Of the two dissenting patients, one thought ‘in principle, it would be fantastic’ but it needed funding; the other did not recall dementia being discussed during their recent appointment.

| Antecedent assessment | Rating | Rationale for rating (+ positive, − negative, o mixed) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Umbrella intervention | |||

| Acceptability | Moderate to high | Promotion of dementia risk reduction | |

| + Gentle approach to education and advice | |||

| + Integration with broader risk reduction strategies for non-communicable diseases | |||

| o Change planning (simple, helpful, and evidence-based, but also sometimes unnecessary) | |||

| Waiting room survey | |||

| + Optional | |||

| + Non-confrontational | |||

| + Brief | |||

| + Physical, non-digital format | |||

| + Content of questions | |||

| + Patient-directed focus on a single priority health area | |||

| − No summary score | |||

| − Not introduced clearly (e.g. priming poster) | |||

| Patient information cards | |||

| + Content | |||

| + Physical hand-out | |||

| − No quick response (QR) codes for websites | |||

| Appropriateness | High | Fit with PCP role | |

| + Enough evidence for DRR | |||

| + Value in promoting DRR | |||

| + PCPs responsibility to promote DRR | |||

| + PCPs should be promoting DRR more | |||

| + PCPs seriously considering promoting DRR with more patients | |||

| Fit with clinic needs | |||

| + Raised the relative priority of DRR | |||

| + Filled a gap in patient educational materials | |||

| + Compatible with existing workflows | |||

| Fit with patient needs | |||

| + Optional | |||

| + No mention of dementia until the PCP consultation | |||

| + Education and advice from a trustworthy person | |||

| + Could be offered to all patients aged 40–64 years in general practice | |||

| − Written patient information cards could be forgotten/overlooked | |||

| − Neglected patients aged 65 years and older | |||

| Feasibility | Moderate | + Manageable workload | |

| + Straightforward actions | |||

| + Able to spread the discussion across two appointments, potentially within a Medicare-rebated Heart Health Check | |||

| − Lack of Medicare benefits for nurses’ time and allied health services | |||

| Implementation strategies | |||

| Acceptability | Mixed | + Incremental, gradual approach | |

| + Outreach visits with Lego® model | |||

| + Information about promoting DRR (e.g. suggested Medicare items) | |||

| + Champions | |||

| + Site visits from the implementation facilitator | |||

| − Online peer discussion | |||

| Appropriateness | Mixed | Fit with PCP needs | |

| o Incremental, gradual approach (fit with needs, but difficult to remember tasks) | |||

| + Confidence-building | |||

| + Clarified goals for promoting DRR | |||

| + Filled a gap in education and training about promoting DRR | |||

| + Brief guidance on motivational interviewing was appropriate to existing skills | |||

| + Feedback on progress | |||

| Fit with receptionist needs | |||

| − Reception staff not prepared for the change in practice | |||

| Feasibility | Mixed | + Two 4-week implementation cycles | |

| − Lunchtime in-person meetings | |||

| − Online peer discussion | |||

Antecedent assessments for the implementation strategies were mixed. Most implementation strategies were acceptable, apart from the online peer discussion. Initially, PCPs were excited at the prospect of sharing and learning from other general practices in an online discussion they could participate in flexibly. However, from a feasibility perspective, many PCPs either forgot to contribute, ran out of time, or had limited computer skills. PCPs suggested sharing weekly (instead of twice a week) and using a messaging app on their smartphones (e.g. WhatsApp) instead of a web-based password-protected portal. In terms of appropriateness, the implementation strategies were suitable for PCPs but not reception staff. Few reception staff read the information provided; they learned about the intervention verbally from their PMs or colleagues or from the implementation facilitator during site visits. On the request of PMs and GP champions, a one-page instruction sheet for reception staff was disseminated (see the Supplementary material). Field notes indicated at least some staff found the instructions useful and the supporting website was visited 101 times. Nevertheless, at the end of the study, at least one PM still thought the reception staff needed more guidance. ‘He didn’t really know what to say, even though I told him 20 million times, so he tended not to do it’ (PM, Practice A). Data from surveys and interviews that support these findings are provided in the Supplementary material.

Possible influences on outcomes

The pilot study was not powered to evaluate differences in implementation outcomes between patients, staff, and study sites. Nevertheless, evaluation data suggested that characteristics of patients, staff, and the general practice setting might have influenced outcomes. These characteristics are summarised in Table 4. For some characteristics (e.g. being new to the practice; having a family history of dementia), participants were divided on whether the characteristic was an important influence on outcomes.

| Patient characteristics | Staff characteristics | General practice setting characteristics | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Increasing appropriateness of the intervention: | Increasing appropriateness of the intervention: | Decreasing feasibility of the intervention: | |

| + High health literacy | + Full-time role | − Reception staff too busy | |

| + English-speaking background | + Patient-centred outlook | − Difficulty establishing a routine | |

| + Ability to complete the waiting room survey properly | + Longer appointment times (PCPs) | − Not enough time to become familiar with the materials | |

| + High risk profile | + Financial stake in the practice (PCPs) | − Not integrated with existing practice software | |

| + Interested in changing lifestyle behaviours | + Well-established in the general practice | ||

| + Not yet aware of the potential for DRR or available supports | |||

| + Receptive to information about DRR | |||

| + Not currently ill or preoccupied with other health concerns | |||

| + Not currently pregnant | |||

| + Sufficient means to pay for PCPs’ time and make lifestyle changes |

Possible associations between outcomes

We expected that antecedent assessments would influence actual outcomes. The study design did not allow for definitive assessment of associations between outcomes; however, qualitative data were consistent with our expectations. For example, it was not always feasible for reception staff to distribute waiting room surveys, contributing to low penetration of the Umbrella intervention among patients. Similarly, joining the online peer discussion was not feasible for some PCPs which reduced fidelity to this implementation strategy.

Also as expected, the actual outcomes of the implementation strategies seemed to influence antecedent assessments for the Umbrella intervention. For example, educational meetings and consensus discussions were conducted as intended, helping staff who attended to conclude that the Umbrella intervention was broadly acceptable, appropriate, and feasible. Nearly all PCPs who engaged with the implementation strategies (16/17, 94%) agreed to use the Umbrella intervention.

Interestingly, we also found evidence suggesting that actual incomes could influence antecedent assessments. For example, the low penetration of the intervention among patients meant it was feasible for PCPs to use the Umbrella intervention alongside their existing workload. ‘It would be overwhelming if it was more than 5 each a day’ (PM, Practice E). Similarly, poor fidelity to the online peer discussion made this implementation strategy less acceptable as time went on.

Discussion

Summary

The Umbrella intervention was a new approach to supporting Australian PCPs to promote DRR. It was complemented by educational and relational strategies intended to mitigate barriers to promoting DRR. Piloting of the intervention and implementation strategies in five Australian general practices produced mixed findings. Participants thought the Umbrella intervention was an acceptable, appropriate, and feasible means of supporting practice change. Approximately half of the eligible PCPs within participating practices promoted DRR using the Umbrella intervention at least once, with moderate fidelity. Similarly, approximately half of eligible PCPs engaged with at least one implementation strategy. PCPs found most implementation strategies acceptable, appropriate, and feasible, although they wanted a simpler platform for online peer discussion and strategies to better prepare reception staff for the change in practice.

Implications

Of the 12 outcomes assessed in the pilot study, penetration of the Umbrella intervention was the only reliably low outcome. Penetration was low despite positive antecedent assessments, which seem necessary but not sufficient for intervention uptake (Sekhon et al. 2017). A more robust online peer discussion may have yielded suggestions and momentum to improve penetration. Low penetration of the intervention may have been partly attributable to low attendance at the initial outreach visit, which in turn may have been because lunchtime in-person meetings were not feasible for many PCPs and reception staff. However, even allowing for low penetration among PCPs, the Umbrella intervention reached very few patients. For comparison, a similar waiting room survey (eCHAT) was completed by 211 patients during a 2- to 3-week period in two general practices in New Zealand (Goodyear-Smith et al. 2013). The Umbrella intervention waiting room survey reached fewer patients over a longer period in more practices. There were two critical differences between the studies: a dedicated research assistant invited patients to complete the eCHAT, and it was completed on an iPad. In our study, patients and staff liked the waiting room survey being paper-based, but an electronic survey that bypassed reception staff might reach more patients. It is also possible that eligible patients were missed in our study because they were acutely ill, preoccupied with other health concerns, or did not attend the general practice in the 8-week study period (e.g. postponing non-essential health care due to COVID-19 concerns). Future research should examine these hypotheses about the low penetration of the Umbrella intervention and consider strategies to improve it.

Our study produced similar findings to a pilot evaluation of the dementia awareness component in the National Health Service (NHS) Health Check when it was introduced for adults younger than 65 years (Solutions Strategy Research Facilitation Ltd and Cornish and Grey Ltd 2017). In both evaluations, patients and PCPs liked the idea of promoting DRR, thought it complemented messages about risk reduction for other non-communicable diseases, and found written information helpful. As in the NHS Health Check evaluation, the intervention was seen as manageable, straightforward, and reasonably memorable; it was recalled by 79% of patients in the NHS Health Check evaluation and 69% of patients in the current study. In both cases, PCPs sometimes judged whether it was appropriate to promote DRR based on individual patient characteristics (NHS Health Check 2017). Interestingly, PCPs in the NHS Health Check evaluation lacked confidence in raising the topic of dementia and wanted further training, prompts, and resources. In the current study, PCPs reported that many of the implementation strategies (e.g. information cards, site visits, taking an incremental approach) helped them deliver the intervention.

Strengths and limitations

The pilot study considered 12 implementation outcomes for a new intervention and implementation strategies. The in-depth focus on implementation outcomes was a departure from the efficacy perspective, in which randomised controlled trials are the gold standard but can be problematic in DRR research because they need a large sample and a long follow-up. While not contributing data on the efficacy of promoting DRR, the pilot study generated new knowledge about implementation in the primary care setting that could reduce research waste and decision-maker uncertainty.

It is likely that staff in some eligible practices did not read the recruitment notice in the South East Melbourne PHN newsletter or attend network meetings marketing the pilot study and were therefore unaware of the Umbrella intervention. An alternative recruitment strategy may have led to higher adoption.

The mixed-methods approach to data collection triangulated outcome data from multiple sources without undue burden on participants. Confidential, individual interviews with practice champions and PMs complemented consensus-focused group meetings. However, the same researcher facilitated implementation and collected outcome data, and telephone interviews may have deterred participants not comfortable communicating in English.

This study predated the COVID-19 pandemic, which led to the expansion and increased uptake of telehealth services in general practice (MBS Review Advisory Committee 2024). It is unclear whether the Umbrella intervention (which hinges on patients completing a paper-based survey and receiving physical information cards) is appropriate in this changed context and, if not, how it should be modified.

Future directions

The Umbrella intervention and implementation strategies should be refined based on findings from the pilot study and further stakeholder input. These innovations show promise but there is still work needed to understand and improve adoption and penetration. Additional funding may be needed to support marketing of the innovations, reimbursement of practice staff, and integration of the innovations with existing practice software.

While the pilot study may have successfully reached innovative practices, there remains a question of how to engage the remaining 98% of practices. It is possible that staff in these practices (if they were aware of the study) viewed the Umbrella intervention and implementation strategies as less acceptable, appropriate, and feasible. Patients in these practices could potentially be from more diverse backgrounds and settings and therefore the intervention and implementation strategies may require adaptation. Stakeholders from these practices should be involved in adapting and refining the intervention and implementation strategies. Future research could also evaluate additional outcomes such as cost, sustainment, and patient health outcomes. Showing that the Umbrella intervention benefits patients and is cost-effective could build support for wider use.

Conclusions

The pilot study suggested that the Umbrella intervention is an acceptable, appropriate, and feasible way to support the promotion of DRR in Australian general practice. Nevertheless, penetration (or ‘reach’) of the Umbrella intervention was low. Combining educational and relational strategies seemed to be an acceptable and appropriate approach to support PCPs to use the Umbrella intervention, but it was not sufficient to guarantee use. While the evidence reported here suggests that a definitive randomised controlled trial would be premature, the pilot study generated vital new knowledge about implementing DRR evidence in routine clinical practice.

Data availability

The data that support this study cannot be publicly shared due to ethical or privacy reasons and may be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author if appropriate.

Declaration of funding

KG was supported by a PhD Fellowship attached to the Maintain Your Brain (MYB) Study, funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (GNT1095097). The funding body had no role in the preparation of the data or manuscript or in the decision to submit for publication.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the general practice staff and patients who participated in the study and the South East Melbourne Primary Health Network for assisting with recruitment. This work was part of the Maintain Your Brain (MYB) study. Participants for the MYB study were recruited from the 45 and Up Study (www.saxinstitute.org.au). The 45 and Up Study is managed by the Sax Institute in collaboration with major partner Cancer Council NSW and the following partners: the National Heart Foundation of Australia (NSW Division), NSW Ministry of Health, NSW Government Family and Community Services – Ageing, Carers and the Disability Council NSW, and the Australian Red Cross Blood Service. The authors thank the many thousands of people participating in the 45 and Up Study.

References

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2021) Practice incentives program quality improvement measures: national report on the first year of data 2020-21. (AIHW: Canberra, ACT, Australia) Available at https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/primary-health-care/pipqi-measures-national-report-2020-21 [verified 10 May 2024]

Damschroder LJ, Reardon CM, Opra Widerquist MA, Lowery J (2022) Conceptualizing outcomes for use with the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR): the CFIR Outcomes Addendum. Implementation Science 17(1), 7.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Godbee K, Gunn J, Lautenschlager NT, Curran E, Palmer VJ (2019) Implementing dementia risk reduction in primary care: a preliminary conceptual model based on a scoping review of practitioners’ views. Primary Health Care Research & Development 20, e140.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Godbee K, Gunn J, Lautenschlager NT, Palmer VJ (2020) Refined conceptual model for implementing dementia risk reduction: incorporating perspectives from Australian general practice. Australian Journal of Primary Health 26(3), 247-255.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Godbee K, Farrow M, Bindoff A, Gunn J, Lautenschlager N, Palmer V (2021) Implementing dementia risk reduction in primary care: views of enrollees in the Preventing Dementia Massive Open Online Course. Australian Journal of Primary Health 27(6), 479-484.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Godbee K, Guccione L, Palmer VJ, Gunn J, Lautenschlager N, Francis JJ (2022) Dementia risk reduction in primary care: a scoping review of clinical guidelines using a behavioral specificity framework. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 89(3), 789-802.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Goodyear-Smith F, Warren J, Bojic M, Chong A (2013) eCHAT for lifestyle and mental health screening in primary care. Annals of Family Medicine 11(5), 460-466.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE (2005) Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research 15(9), 1277-1288.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Huybrechts I, Declercq A, Verte E, Raeymaeckers P, Anthierens S (2021) The building blocks of implementation frameworks and models in primary care: a narrative review. Frontiers in Public Health 9, 675171.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Livingston G, Huntley J, Liu KY, Costafreda SG, Selbæk G, Alladi S, Ames D, Banerjee S, Burns A, Brayne C, Fox NC, Ferri CP, Gitlin LN, Howard R, Kales HC, Kivimäki M, Larson EB, Nakasujja N, Rockwood K, Samus Q, Shirai K, Singh-Manoux A, Schneider LS, Walsh S, Yao Y, Sommerlad A, Mukadam N (2024) Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2024 report of the Lancet standing Commission. The Lancet 404(10452), 572-628.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

MBS Review Advisory Committee (2024) Telehealth post-implementation review: final report. (MBS Review Advisory Committee) Available at https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/2024-06/mbs-review-advisory-committee-telehealth-post-implementation-review-final-report.pdf [verified 17 August 2024]

Mostofian F, Ruban C, Simunovic N, Bhandari M (2015) Changing physician behavior: what works? American Journal of Managed Care 21(1), 75-84.

| Google Scholar | PubMed |

NHS Health Check (2017) NHS health check top tips: talking about dementia. Available at https://www.healthcheck.nhs.uk/seecmsfile/?id=247 [verified 10 May 2024]

Pinnock H, Barwick M, Carpenter CR, Eldridge S, Grandes G, Griffiths CJ, Rycroft-Malone J, Meissner P, Murray E, Patel A, Sheikh A, Taylor SJC, Sta RIG (2017) Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies (StaRI): explanation and elaboration document. BMJ Open 7(4), e013318.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A, Griffey R, Hensley M (2011) Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research 38(2), 65-76.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Public Health Information Development Unit (2019) Social health atlas of Australia: population health areas. Available at http://phidu.torrens.edu.au/social-health-atlases/data#social-health-atlas-of-australia-population-health-areas [Verified 10 May 2024]

Sekhon M, Cartwright M, Francis JJ (2017) Acceptability of healthcare interventions: an overview of reviews and development of a theoretical framework. BMC Health Services Research 17(1), 88.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Solutions Strategy Research Facilitation Ltd and Cornish and Grey Ltd (2017) NHS Health Check 40-64 Dementia Pilot: Research Findings. Summary research report. Available at https://www.alzheimersresearchuk.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Solutions-Dementia-Pilot-Summary-Report-Final-24.7.17-1.pdf [verified 10 May 2024]

Toomey E, Matthews J, Hurley DA (2017) Using mixed methods to assess fidelity of delivery and its influencing factors in a complex self-management intervention for people with osteoarthritis and low back pain. BMJ Open 7(8), e015452.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Waltz TJ, Powell BJ, Matthieu MM, Damschroder LJ, Chinman MJ, Smith JL, Proctor EK, Kirchner JAE (2015) Use of concept mapping to characterize relationships among implementation strategies and assess their feasibility and importance: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) study. Implementation Science 10(1), 109.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Zheng L, Godbee K, Steiner GZ, Daylight G, Ee C, Hill TY, Hohenberg MI, Lautenschlager NT, McDonald K, Pond D, Radford K, Anstey KJ, Peters R (2021) Dementia risk reduction in practice: the knowledge, opinions and perspectives of Australian healthcare providers. Australian Journal of Primary Health 27(2), 136-142.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |