Factors informing funding of health services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children: perspectives of decision-makers

Shingisai Chando A B * , Martin Howell A C , Michelle Dickson A B , Allison Jaure A D , Jonathan C. Craig E , Sandra J. Eades F and Kirsten Howard A C

A B * , Martin Howell A C , Michelle Dickson A B , Allison Jaure A D , Jonathan C. Craig E , Sandra J. Eades F and Kirsten Howard A C

A

B

C

D

E

F

Abstract

The factors informing decisions to fund health services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children are unclear. This study’s objective aimed to describe decision-makers’ perspectives on factors informing decisions to fund health services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children.

We conducted semi-structured interviews with 13 participants experienced in making funding decisions at organisational, state, territory and national levels. Decision-makers were from New South Wales, Northern Territory, Queensland, Victoria and Western Australia. Transcripts were analysed thematically following the principles of grounded theory.

We identified five themes, each with subthemes. First, prioritising engagement for authentic partnerships (opportunities to build relationships and mutual understanding, co-design and co-evaluation for implementation). Second, valuing participant experiences to secure receptiveness (cultivating culturally safe environments to facilitate acceptability, empowering for self-determination and sustainability, strengthening connectedness and collaboration for holistic care, restoring confidence and generational trust through long-term commitments). Third, comprehensive approaches to promote health and wellbeing (linking impacts to developmental milestones, maintaining access to health care, broadening conceptualisations of child health). Fourth, threats to optimal service delivery (fractured and outdated technology systems amplify data access difficulties, failure to ‘truly listen’ fuelling redundant policy, rigid funding models undermining innovation). Fifth, navigating political and ideological hurdles to advance community priorities (negotiating politicians’ willingness to support community-driven objectives, pressure to satisfy economic and policy considerations, countering entrenched hesitancy to community-controlled governance).

Decision-makers viewed participation, engagement, trust, empowerment and community acceptance as important indicators of service performance. This study highlights factors that influence decisions to fund health services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children.

Keywords: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, child health services, evaluation reporting, health services, health services funding, health services policy, Indigenous health services, primary health care.

Introduction

Funding decisions are complex processes requiring evidence from multiple stakeholders about what works (Luke et al. 2020). Typically, program evaluations are the most common formal method of reporting on the effectiveness of programs and the value of services to participants (Productivity Commission Report 2020). In Australia, the use of evaluations to inform decisions affecting health services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people varies, largely because the data are scarce and not always considered relevant for funding decisions (Campbell et al. 2009; Hudson 2016; Kelaher et al. 2018; Cargo et al. 2019). Reporting on the factors that decision-makers find helpful when determining how best to allocate resources could have significant implications for the future of some health services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children.

Health services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children are often delivered in primary care settings. Producing reports on how effective these services are, that extend beyond clinical data and are useful for processes, such as funding decisions, is constrained. This is because, overall, few health services, especially those relating to health promotion, have been evaluated (Campbell et al. 2009; Hudson 2016). The Australian Government has in recent years increased investment to expand monitoring and evaluation (Hudson et al. 2017) of all health services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples; however, there remains no centralised and publicly accessible data repository to store reports (Kelaher et al. 2018; Luke et al. 2020). As such, access to evaluation findings is limited for decision-makers (Luke et al. 2020), communities and evaluators interested in understanding the pertinent outcomes to assess and report in their evaluations (Kelaher et al. 2018; Luke et al. 2020).

Of the evaluations that are available, few have used methods that demonstrate service effectiveness, as required for funding and policy decisions (Hudson 2016; Kelaher et al. 2018). More recently, some evaluations have adopted culturally appropriate frameworks and produced evidence that is useful at an organisation level (Hudson et al. 2017; Kelaher et al. 2018; Williams 2018; Productivity Commission Report 2020). Although these data are important and helpful to providers of health services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, their use for funding decisions, particularly for child health services, is unclear.

Without sufficient evidence, evaluators can struggle to align community priorities with the practical needs of decision-makers (Kelaher et al. 2018; Cargo et al. 2019; Finlay et al. 2021). Evidence on the factors and outcomes from health services that are important to decision-makers can guide evaluation commissioning, and help evaluators consider outcomes relevant to funders alongside community priorities. Such data could be particularly useful when evaluating health services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children to ensure that the full value of services is always captured and reported, providing funders with sufficient data to make well informed decisions about the future of valuable child health services. The aim of this study was to describe the perspectives of decision-makers on the important outcomes from health services developed for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children that are useful for funding decisions, and identify any other factors that influence those decisions.

Methods

Study design

Grounded theory guided by principles of decolonisation were used to inform data collection through semi-structured interviews and data analysis (Birks and Mills 2015). We used the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative health research to report results (Tong et al. 2007), and ethical approval was obtained from the Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council (1345/1) and The University of Sydney (2018/103).

Positionality

The investigator team consisted of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and non-Indigenous clinicians and academics. The first author (SC) is non-Indigenous, and from a culturally and linguistically diverse background with 15 years of professional experience in health research, and over 10 years working in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and qualitative research. Two authors (MD and SE) are Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander academics with extensive qualitative research and clinical experience in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander child health services. In addition to providing guidance on the application of decolonising methods, they provided cultural guidance during study design, data analysis and reporting.

Participants and setting

We used purposive sampling and snowballing to recruit decision-makers across Australia (Parker et al. 2019; Campbell et al. 2020). Decision-makers were individuals who had experience making high-level decisions to fund health services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children offered through Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations (ACCHOs) or mainstream health services. Decision-makers were eligible to participate if they had experience directly contributing towards funding decisions at government (national, state or territory) and/or organisational levels, e.g. chief operating officers of health services. Email invitations were sent to the Australian Government Department of Health, state health departments, several peak bodies in health services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, and to investigator networks which included ACCHOs. As interviews progressed, greater emphasis was placed on recruiting from national, state and territory health departments, because data from the first few interviews indicated that they played a greater role in resource allocation across the healthcare system. Written informed consent was provided by all participants.

Data collection

The first author (SC) conducted all the semi-structured interviews using the interview guide provided in Supplementary File S1. One study participant was known to the interviewer. Decision-makers were asked about their views on the factors and outcomes from child health programs that are important and influence funding decisions. Interviews were conducted over the phone between September 2018 and May 2021 until data saturation was reached and no new themes were emerging. The audio recordings were transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis

SC, along with two authors MD and AJ, reviewed and discussed emerging themes after the first few interviews, developing initial codes. At the completion of all the interviews, SC reread transcripts, and using thematic analysis compared with initial codes, then coded the transcripts using NVivo (ver. 12.0; QSR International, https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home). Following the principles of grounded theory (Glaser and Strauss 2017), concepts were identified inductively capturing the factors and outcomes that decision-makers viewed as important and influenced their funding decisions. Similar concepts were grouped into themes and subthemes to develop a comprehensive list of preliminary themes and subthemes. All the authors reviewed the concepts and preliminary themes and subthemes alongside the transcript data to ensure that the full range of data was reflected in the final themes presented in the findings. Following an iterative process, the final themes and subthemes were selected by the author group.

Results

Thirteen decision-makers participated in semi-structured interviews (Table 1), with each lasting an average of 35 min. Four identified as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, and nine were non-Indigenous. All participants had been directly involved in decisions to fund health services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children. Most participants had participated in resource allocation decisions for child health programs in New South Wales (54%). Participants had been involved in decision-making at organisational (62%), state/territory (46%) and national (31%) levels. Only one decision-maker had organisational-level decision-making experience only. All decision-makers with experience at national levels had also held leadership positions at an organisational level at services providing primary care to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children. Three decision-makers, two with state-level experience and one with territory level experience, reported participating in decision-making at the organisational level with services providing primary care.

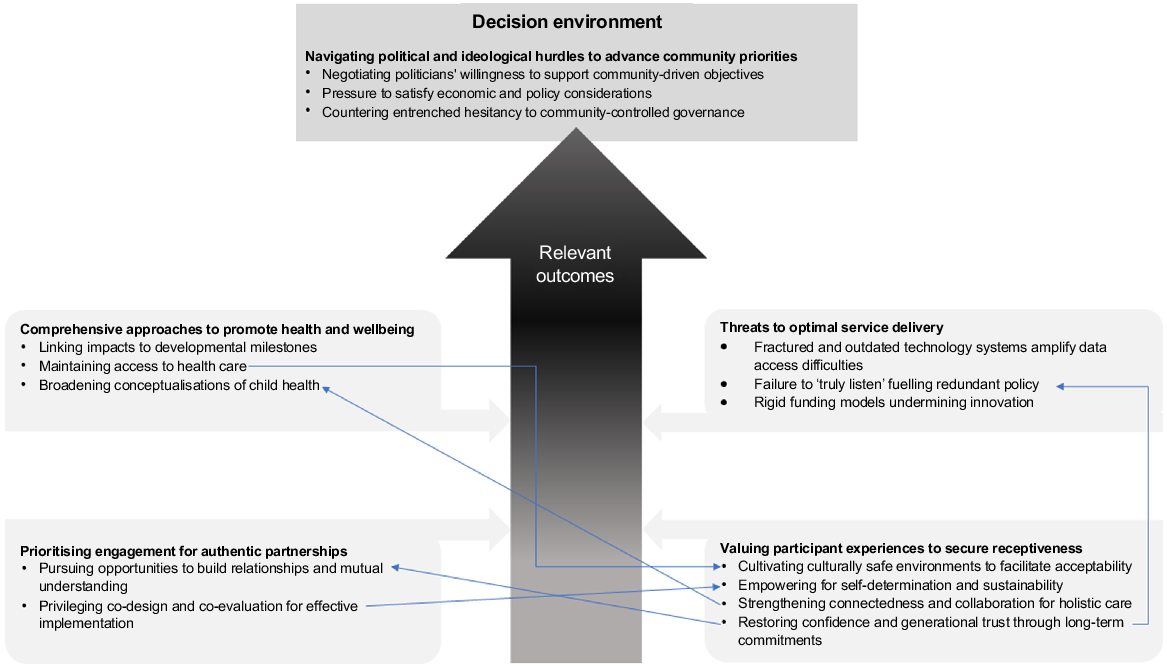

We identified five themes: prioritising engagement for authentic partnerships, valuing participant experiences to secure receptiveness, comprehensive approaches to promote health and wellbeing, threats to optimal service delivery, and navigating political and ideological hurdles to advance community priorities. The first three themes related to decision-makers’ perceptions of service delivery factors. The theme ‘threats to optimal service delivery’ related to the broader constraints on funding decision-making processes that are internal and external to health services. Whereas the final theme identifies contextual factors within the decision environment that impact on decision-making.

The themes and subthemes are described below, and some illustrative quotes to support each theme are provided in Table 2. A thematic schema is presented in Fig. 1 to show the conceptual links between the themes.

| Theme and subthemes | Illustrative quotes | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Prioritising engagement for authentic partnerships | ||

| Pursuing opportunities to build relationships and mutual understanding | ‘Then there’s “oh people don’t engage” and it’s not [that] they don’t engage, it’s that you’re not engaging with them … when I look at projects that are unsuccessful. I go straight to the methodology and look at why, regardless what they report on, because if there’s no community engagement, or community participation well then that’s your biggest mistake.’ (Respondent 04) | |

| ‘They [health services staff] go to a lot of community events where they might link in the child with the family health services. So they have a presence in the community.’ (Respondent 02) | ||

| ‘Engage with the local community so that they see that they have a role in decision-making and that what you’re doing is supportive of their own aspirations.’ (Respondent 09) | ||

| Privileging co-design and co-evaluation for effective implementation | ‘Co-design needs to be embedded front and centre in every part of the process from the design through implementation through evaluation. I think really it’s only when we get to that point, that we’ll start really uncovering this richness of, input and information around how people are experiencing impacts of policy and programs, and we can start factoring them into design.’ (Respondent 11) | |

| ‘To make a project successful is just going to be consumer engagement, and consumer involvement, and ensuring that your consumers are fully aware of what is going on.’ (Respondent 04) | ||

| ‘So often consultation, not co-design, but consultation can be very tokenistic in that respect. Yes. It’s something that we do because it’s a ticking the box because there’s the government process for stakeholder consultation. So we need to demonstrate that we’ve done our due diligence.’ (Respondent 11) | ||

| 2. Valuing participant experiences to secure receptiveness | ||

| Cultivating culturally safe environments to facilitate acceptability | ‘There was no sense of really understanding that you can’t fund a non-Indigenous non-government organisation … to go into an Aboriginal community. Cause they just don’t have the nuance in the community. They don’t necessarily have the right staff. So they may look good on paper and present a good argument and, you know, have a really good return on investment for everything else they run. But there needs to be an appreciation of the expertise that comes with being Indigenous and having worked in a community, and understanding those kinds of embedded protocols that you just can’t write down on paper and say that you can do that.’ (Respondent 12) | |

| ‘I have a strong view that if there’s cultural safety in the delivery of services, then you’ll get a better health outcome.’ (Respondent 09) | ||

| Empowering for self-determination and sustainability | ‘The impact of success and community ownership. We see other community members reinforcing that [behaviour change]. So if someone walks up with a coke, they’ll be like, “Hey, this is [program name]. You shouldn’t be drinking that”. And if someone’s smoking, they’ll be like… “put that out”, self-policing.’ (Respondent 12) | |

| ‘A number of communities have undertaken community-wide education programs around prevention of rheumatic heart disease. They necessarily involve, and I’m not confined to just children, but those education programs require the whole family and the whole community to buy in to get the best outcome … that means that the community has got to own the outcome and own the problem.’ (Respondent 09) | ||

| Strengthening connectedness and collaboration for holistic care | ‘Understanding the needs of the community, in a holistic way, and having a strong link with the other services working with the community so that there’s no duplications. There are many issues that all services are needing to address within the family and good communication between all the services that are working with the family and with the community, would give you better outcomes.’ (Respondent 12) | |

| Restoring confidence and generational trust through long-term commitments | ‘Unless you can get their trust, they won’t turn up for care. And it’s often multi-generational. I mean, we, we changed the names of all these organisations and we go from public to NGOs [non-governmental organisations], whatever, but these families only talk about one thing and that’s the welfare in inverted commas. And you can see that it’s, multi-generational distrust of institutions and often really impairs people getting to care.’ (Respondent 10) | |

| ‘I think the best programs provide ongoing models of care and ongoing funding … I don’t think we need more studies and I don’t think we need 12 months or two year programs. I think they are a really very bad model for Indigenous communities, because as you know, these things are ongoing and they need ongoing commitment.’ (Respondent 10) | ||

| 3. Comprehensive approaches to promote health and wellbeing | ||

| Linking impacts to developmental milestones | ‘I think that’s where a lot of the improvements can come from. The preschool through the early primary school period, if we can address the health and education issues, we’ll make a big difference in the longer term.’ (Respondent 10) | |

| ‘I’ve got a very strong view about the linear progression between child maternal health and early childhood health and early childhood education. If it [the program] works properly, will mean that by the time the child leaves preschool and was going to school they are healthy and well. A lot of this information will require longitudinal studies. Can’t be evaluated based on, investing a million dollars this year and getting an outcome next year because the outcome might not be foreseeable for some years.’ (Respondent 09) | ||

| Maintaining access to health care | ‘Most people travel particularly to, you know, leave their country and go travel long distances to strange places, and get very often culturally inappropriate management. Just breeds distrust, breeds short-termism because the programs don’t continue because the community aren’t enthusiastic.’ (Respondent 10) | |

| Broadening conceptualisations of child health | ‘So programs around nutrition, which are targeted at the community actually have the greatest impact on children. The incidence of childhood diabetes, which relates largely to the impact of the local environment, and require, families to understand how to eat healthily and provide exercise. All of these in my view are programs which ultimately have a child health outcome, but they’re not perceived as child health programs.’ (Respondent 09) | |

| 4. Navigating political and ideological hurdles to advance community priorities | ||

| Negotiating politicians’ willingness to support community-driven objectives | ‘So I have to be cognisant about what is politically acceptable in terms of the government’s agenda. But then I also have to negotiate with the very people around me around what their belief systems are, what is palatable to them as well as what is not palatable to them to be able to know what I should be fighting for.’ (Respondent 13) | |

| ‘I think, for the subject matter experts to be able to advocate for yes, but this will provide more value for money because here’s a particular, um, you know, getting back to that value equation, the outcome in relation to costs. But I think at the end of the day, the decision on what gets funded and what doesn’t is a political decision, and it’s usually up to ministers to make that determination.’ (Respondent 11) | ||

| Pressure to satisfy economic and policy considerations | ‘You kind of understand what needs to be ticked … tick box for that … is it evidence-based, do you have the funding envelope for it? … But from my experience, it’s about, building the capacity of community control health services and whether that’s actually been co-designed or informed by community need and what the need is and where the need is.’ (Respondent 12) | |

| ‘So there are quite a lot of things that would be taken into consideration. You might do it by putting out an expression of interest across the state to local health districts for a business case that they would have to submit to you, justify why and where they would put a service and what resources the service might need. So we’d be very conscious obviously of what else is on the ground and where the needs are and what the outcomes are like there as well.’ (Respondent 02) | ||

| ‘When you’re making a decision, you want your decisions to be around facts and you try and incorporate as much evidence as you can really. I think as a decision-maker you basically look at what’s going to be beneficial and cost-effective, cause it was always comes back down to the money and then it could be culturally appropriate if it’s Aboriginal Torres Islander projects. You don’t want to be making a decision that’s not going to be relevant to the population that you’re actually targeting.’ (Respondent 04) | ||

| Countering entrenched hesitancy to community-led governance | ‘There was always that hesitation from the department around enabling community to take control of services, to take the lead, on innovative programs. And there were always the uncomfortable silence around, whether they had the right governance structure and accountability to see this program or this project to the end and actually achieve what was going to be achieved. So there was a lot of reluctance around giving and investing a large quantity of money.’ (Respondent 12) | |

| ‘I think you’d be wanting to look at the capacity of the people who are administering the program and where they sit within an Aboriginal community controlled organisation. You’d need to be looking at their capacity to have ongoing evaluation and assessment of the program. Uh, and you’d want to be thinking about their capacity to administer such a program.’ (Respondent 09) | ||

| 5. Threats to optimal service delivery | ||

| Fractured and outdated technology systems amplify data access difficulties | ‘… Something happens that prevents them from connecting with that service, some other complexity in their lives or within the community … many layers aren’t well captured in that outcome, which is what needs to be captured in an outcome, or at least accounted for … all we can record is things like … a child did, or didn’t attend an appointment or a child was referred … all of those things, that’s the bit that’s recorded in the system, as opposed to, the circumstances that kind of conspire against why this thing isn’t seamless.’ (Respondent 08) | |

| ‘Once you get beyond the hospital, it becomes harder to collect. So for child and family health we do have community data collection systems that have been developed over a number of years. We are still having problems because we have local health districts that might tweak for their own purposes. The data collection, the way it is collected and pulling information out of that, is becoming problematic.’ (Respondent 02) | ||

| Failure to ‘truly listen’ fuelling redundant policy | ‘If you look to community members to ask them how many consultations they have gone through over the years, how many times they have said the same things and they will tell you, and you’ll sit there and you have to shake your head. You’ll start to disbelieve what they’re saying, because it is so unbelievable that some had to say the same things over so many years and generations again and again still we’re still not listening.’ (Respondent 13) | |

| Rigid funding models undermining innovation | ‘We have to knit behind the scenes a number of different funding programs … The red tape around what you can and can’t use different funding buckets for, it’s just insane … those policy funding models … create a barrier to program innovation and flexibility.’ (Respondent 12) | |

| ‘I certainly think short-term evaluations are of little value in the Indigenous community … for example, one thing that I was involved with some years ago was trying to keep Indigenous kids in families, those who had drug and alcohol problems. But the time frames for those sorts of things are often decades and it’s hard to show short-term improvements. And so funding often gets lost after a couple of years and that’s where, doing evaluations can be a bit misleading.’ (Respondent 10) | ||

| ‘The pressure around the ideal program design and the pragmatism around funding cycles, I think they are the challenges.’ (Respondent 08) | ||

Thematic Schema: Participants believed that successful child health services included: ownership of the responsibility for engagement, authentic relationships with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, processes that value participant experiences allowing their input to shape and drive organisational culture, and comprehensive approaches to addressing child health that promote health and wellbeing to achieve holistic outcomes. System level technological failures and deficient funding models were thought to adversely impact optimal service delivery, and ideological, political and economic environments formed the backdrop against which funding decisions were made.

Prioritising engagement for authentic partnerships

Decision-makers felt that services had a responsibility to seek occasions to interact with communities to build lasting connections and learn how to support the community’s aspirations. Sincere interest in the community’s activities and consistent participation were perceived to facilitate genuine communication between staff and the community.

Decision-makers felt health services should routinely incorporate feedback from consumers, such as parents/caregivers and their children, particularly adolescents, rather than relying solely on community consultations to inform service delivery. Such data were perceived to provide strong evidence for program development and evaluation, and facilitate partnership with parents/caregivers to support the child’s growth.

Valuing participant experiences to secure receptiveness

Decision-makers viewed cultural safety as critically important for gaining acceptance by communities. Having Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander staff was seen as vital to achieving culturally safe health care. Decision-makers perceived that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander staff provide appropriate and nuanced care in ways that non-Indigenous staff struggle to replicate.

Decision-makers felt that employing and training community members equipped Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to participate in their community’s development. Attaining and developing new skills within the community was viewed as important for sustaining progress in delivering on community priorities for existing and future programs. Empowerment was also interpreted as staff being well resourced and community ownership of identified issues and solutions.

Decision-makers felt that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander parents/caregivers engaged well with health services, which helped to connect them to their community and family, and contributed towards creating a cohesive community. Such services also encouraged a collaborative organisational culture, working well with other organisations to coordinate the healthcare needs of children.

Securing the community’s trust was viewed as vital for program success. Decision-makers indicated that abruptly ending services that families relied on contributed to ‘multi-generational distrust’ (Respondent 12) of the intentions of health institutions, making it difficult to manage existing programs or introduce new ones across age groups. Decision-makers perceived that having ongoing funding was critical for programs to continue and community trust to be retained.

Comprehensive approaches to promote health and wellbeing

Decision-makers felt services should demonstrate how the outcomes from their programs contribute to the child’s developmental trajectory. For instance decision-makers wanted to know how some health outcomes contributed to improved education outcomes. By doing so, decision-makers indicated that services improved their understanding of how proposed services advanced overall efforts to improve the health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children.

Decision-makers felt strongly that ensuring easy access to services must be prioritised. In their view, if it is too hard for families to attend services, due to financial circumstances, distance or inconvenience, then participation would eventually wane with ramifications for the child’s future engagement. Failure to provide care in community was perceived to contribute to missed opportunities to prevent illness.

Decision-makers felt services should adopt broader definitions of child health to encompass the broad range of programs that contribute to the health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children; for example, nutritional programs targeted towards parents, but have implications for child health outcomes. They perceived that narrow definitions of child health limit the scope of services provided, negating any positive impacts on other important child health indicators.

Threats to optimal service delivery

Variations to data collection practices and failed migrations of old systems to new systems were perceived to complicate the process of linking and pooling data. Decision-makers felt that the data collection systems available to them were designed to capture ‘output’ and ‘activities’ data, and not the contextual outcomes data they needed to inform localised service delivery. Failing to capture the complexity around outcomes, best described by participant stories and experiences, meant health providers missed critical and timely information explaining positive or poor service performance.

Some decision-makers reported that their ideas to improve policy based on their experiences with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities were not always considered by other decision-makers involved in the decision-making process. They felt this refusal to value community voices and Indigenous knowledge led to the ‘rehashing’ of policy and contributed to communities dismissing proposals, because, despite multiple consultations, previous efforts had not produced the benefit they were looking for.

Decision-makers felt that funding bodies continue to favour paternalistic models. The bureaucracy around funding was perceived to diminish creativity and limit the capacity of health services to pursue flexibility as they respond to dynamic needs of their community. The short funding cycles for services operating in ‘really complex socio-cultural structures’ were thought to be making it difficult for services to take all the ‘right steps’ to include co-design and evaluation of their program design.

Navigating political and ideological hurdles to advance community priorities

Decision-makers felt that their capacity to apply their personal or professional experience and knowledge to advocate for action on priorities important to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities was limited to what was ‘palatable’ in the prevailing political environment. They felt they often have to choose the priorities to champion. Political will was perceived to influence decisions around resource allocation.

Decision-makers felt they had to balance the communities need for funding against the available financial resources. The extent to which applicants could align their proposed use of funds to the health policy agenda often influenced decisions on how decision-makers allocated the resources, despite their acknowledgement of the needs of the health service.

Some decision-makers reported how they experienced push-back in their support of programs led by the community. They felt that people who have not worked closely with ACCHOs struggled to understand these organisations well and were often not enthusiastic about supporting them. However, decision-makers felt that to be successful, initiatives had to be delivered by well-structured ACCHOs with clear objectives and a transparent governance structure.

Discussion

Decision-makers highlighted the factors and outcomes from health services designed for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children that should be considered in reports used to assist with funding decisions. They prioritised factors relating to community responses to the services offered to them, and perceived that successful child health services are characterised by: ownership of the responsibility for engagement, authentic relationships with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, processes that value participant experiences allowing their input to shape and drive organisational culture, and comprehensive approaches to addressing child health that promote health and wellbeing, and achieve holistic outcomes. System-level technological failures, deficient funding models, and ideological, political and economic environments formed the backdrop against which funding decision were made (Fig. 1).

Decision-makers in this study percieved that experience outcomes, such as engagement, participation, empowerment, trust and cultural safety, extend beyond a child’s biomedical needs and are important to successfully deliver health services. These views are consistent with findings from previous research that has characterised effective health services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples (Harfield et al. 2018; National Health and Medical Research Council 2018; Luke et al. 2020). Although there has been some progress in collecting data on experiential outcomes (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2020), this evidence is not routinely reported in measures of program effectiveness (Chando et al. 2021), and there are no known measures to track changes in trust of a health service in children to identify problems with multi-generational distrust. Monitoring and tracking such data can help ensure that the health service is responsive to community needs and maintaining the level of trust required, so that caregivers and their children feel safe to continue using their services.

Efforts to improve participation and engagement can burden Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander parents/caregivers who are balancing competing priorities. Our findings suggest that health services should recognise that the onus of initiating and sustaining relationships with parents/caregivers and children rests with the service. This requires a reflexive and critical assessment, at the organisational level, of the approaches and processes that services employ to connect with the people who use their services (Wilson et al. 2020). Health services should continually audit processes and review how their activities demonstrate vigilance in their commitments to engaging with service users.

This study corroborates previous research supporting holistic approaches to health services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children (Harfield et al. 2018; Chando et al. 2022). Projects through the First 2000 days policy framework are making progressive improvements in access and early detection of ill health among children (NSW Ministry of Health 2019). Our findings underscore the need for approaches that address social determinants of health holistically to ensure that all aspects of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children’s development are supported.

Our findings also suggest that the persistent health system failures in technology limits the capacity of health services to systematically report on experiential outcomes. Targeted investment to improve the technology infrastructure necessary to collect and store relevant data can prevent the loss of useful information. Better mapping of gaps in technology support for health services at the local level, particularly for child health services, is needed to identify and resolve inefficiencies.

An important threat to optimal service delivery identified in this study and previous research is the adverse impact of existing inflexible funding models on innovation (Murphy and Reath 2014). In general, more financial resources are required to meet and close the funding gaps in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health (National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation 2022). However, short funding cycles are particularly disruptive to the delivery of health services to children, which require ongoing and long-term financial commitments to achieve outcomes. A premature end to programs can exacerbate the multigenerational mistrust reported in this study, creating barriers to implementation for future programs. Stronger leadership at state, territory and national levels is required to change the inefficient short-term funding models in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health (Harfield et al. 2018).

This study highlights the tension decision-makers experience between ideological, political and economic factors impacting decision environments and their attempts to privilege community priorities. Our results underscore the need for spaces where Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people can speak without fear during shared decision-making (Australian Government 2021). Spaces where the contributions of Aboriginal and Torres Strait knowledges are valued and afforded the same attention and consideration as Western knowledge (Parter et al. 2024).

Health services can contribute towards improving the quality of information available to decision-makers by reporting on the policy relevance of their operations in evaluations to avoid having their research dismissed by policymakers, as funding decisions will remain the responsibility of government into the future (Campbell et al. 2009; Australian Government 2021). However, to avoid burdening health services, funding bodies could provide clearer and more accessible guidance about what is required for funding decisions. Greater accountability around decisions for funding is needed to ensure that political and ideological pressures are not responsible for the early abandonment of valuable programs.

Although our study contributes towards an area of research with insufficient evidence, there were some limitations. We interviewed decision-makers who had participated in decisions affecting health services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children residing in four states and one territory. The majority of participants were from New South Wales, thus, the transferability of the findings beyond these settings is uncertain. However, our respondents had contributed towards decisions for health services located in rural, remote and urban regions within large and small Aboriginal and Torres Islander communities, thus, they could provide perspectives across a diverse range of communities. Some changes to policies in the delivery of health services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children had occurred by the time this study was completed. The National Agreement came into effect in 2020 outlining refreshed targets for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander child health and new approaches to achieve them. Despite these policy changes, our findings remain relevant and coincide with ongoing enhancements to health services delivery for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children.

Conclusion

The study highlighted the types of information about health services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children that are useful in processes to make funding decisions. Specifically, the importance of experience outcomes, and internal and external organisational factors affecting their achievement. Other important considerations identified in this study were constraints on the reporting of relevant experience and child health outcomes, and factors within the decision environment. Findings from this study clarify the types of measures that health services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children can collect and report to equip decision-makers with information they find useful when making funding decisions.

Data availability

The data that support this study will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Declaration of funding

SC was a recipient of a National Health and Medical Research Council Postgraduate Scholarship award and was supported by SEARCH (The Study of Environment on Aboriginal Resilience and Child Health), which was funded by grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council (1023998, 1035378, 1124822 and 1135271), the NSW Ministry of Health and the Commonwealth Department of Health. The funders were not involved in the preparation of the data and manuscript or decision to submit for publication.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the Traditional Custodians of the Country on which this research was conducted, and pay our respects to Elders past, present and emerging.

References

Australian Government (2021) National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2021–2031. (Commonwealth of Australia Canberra, ACT). Available at https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2021/12/national-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-health-plan-2021-2031_2.pdf [accessed 5 January 2022]

Campbell DM, Redman S, Jorm L, Cooke M, Zwi AB, Rychetnik L (2009) Increasing the use of evidence in health policy: practice and views of policy makers and researchers. Australia and New Zealand Health Policy 6, 21.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Campbell S, Greenwood M, Prior S, Shearer T, Walkem K, Young S, Bywaters D, Walker K (2020) Purposive sampling: complex or simple? Research case examples. Journal of Research in Nursing 25, 652-661.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Cargo M, Potaka-Osborne G, Cvitanovic L, Warner L, Clarke S, Judd J, Chakraborty A, Boulton A (2019) Strategies to support culturally safe health and wellbeing evaluations in Indigenous settings in Australia and New Zealand: a concept mapping study. International Journal for Equity in Health 18, 194.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Chando S, Tong A, Howell M, Dickson M, Craig JC, DeLacy J, Eades SJ, Howard K (2021) Stakeholder perspectives on the implementation and impact of Indigenous health interventions: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Health Expectations 24, 731-743.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Chando S, Dickson M, Howell M, Tong A, Craig JC, Slater K, Smith N, Nixon J, Eades SJ, Howard K (2022) Delivering health programs for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children: carer and staff views on what’s important. Health Promotion Journal of Australia 33, 222-234.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Finlay SM, Cargo M, Smith JA, Judd J, Boulton A, Foley D, Roe Y, Fredericks B (2021) The dichotomy of commissioning Indigenous health and wellbeing program evaluations: what the funder wants vs what the community needs. Health Promotion Journal of Australia 32, 149-151.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Harfield SG, Davy C, McArthur A, Munn Z, Brown A, Brown N (2018) Characteristics of Indigenous primary health care service delivery models: a systematic scoping review. Globalization and Health 14, 12.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Luke JN, Ferdinand AS, Paradies Y, Chamravi D, Kelaher M (2020) Walking the talk: evaluating the alignment between Australian governments’ stated principles for working in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health contexts and health evaluation practice. BMC Public Health 20, 1856.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Murphy B, Reath JS (2014) The imperative for investment in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health. Medical Journal of Australia 200, 615-616.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

National Health and Medical Research Council (2018) Ethical conduct in research with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples and communities: guidelines for researchers and stakeholders. (Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, ACT). Available at https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/resources/ethical-conduct-research-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-peoples-and-communities [accessed 31 December 2021]

Parter C, Murray D, Mokak R, Briscoe K, Weston R, Mohamed J (2024) Implementing the cultural determinants of health: our knowledges and cultures in a health system that is not free of racism. Medical Journal of Australia 221, 5-7.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J (2007) Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 19, 349-357.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Williams M (2018) Ngaa-bi-nya Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander program evaluation framework. Evaluation Journal of Australasia 18, 6-20.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Wilson AM, Kelly J, Jones M, O’Donnell K, Wilson S, Tonkin E, Magarey A (2020) Working together in Aboriginal health: a framework to guide health professional practice. BMC Health Services Research 20, 601.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |