The absurdity of nature love through aviary bird-keeping

Minh-Hoang Nguyen A * and Quan-Hoang Vuong A B

A * and Quan-Hoang Vuong A B

A

B

Abstract

As mounting evidence highlights the human-driven extinction of avian species, reconnecting people with nature – particularly where birds are concerned – has become essential for engaging the public in conservation and the preservation of avian biodiversity. Paradoxically, heightened awareness of the benefits birds bring has fueled the rise of aviary bird-keeping for entertainment in Vietnam. This paper seeks to unravel the absurdity of bird keepers who claim to love nature and support conservation while engaging in practices that exploit and commodify birds for human interests. Through contrasting the values generated by birds in aviaries with those in natural habitats, the role of an eco-deficit culture – or, more fundamentally, humanity’s insatiable greed – in fostering this absurd form of ‘nature love’ is highlighted.

Keywords: avian biodiversity loss, aviary bird-keeping, biodiversity conservation, bird lovers, natural absurdity, nature love.

Are humans in a toxic, abusive relationship with nature? Love is strange. (In ‘Glands of Love’; Meandering Sobriety (Vuong 2023)

Bird extinction crisis and the emergence of aviary bird-keeping for entertainment

Consistent evidence shows the tremendous impacts of humans on the extinction of multiple avian species. The study of Cooke et al. (2023), based on recorded extinctions and the completeness of fossil records, estimates that at least 1300–1500 bird species have become extinct since the Late Pleistocene, representing over 12% of all known bird species on Earth. Most of these extinctions were driven by human expansion from Africa and across the planet. Since 1500, 129 bird species have been officially listed as globally extinct (Butchart et al. 2004). In North America alone, bird populations have declined by nearly three billion individuals since 1970 (Rosenberg et al. 2019). With the alarming impact of human activities on Earth’s ecosystems, reconnecting people with nature, specifically these feathered species, has become critical. Such a connection could foster greater public engagement in conservation efforts and the protection of avian biodiversity (Nguyen et al. 2023a, 2023b).

Birds, with vibrant colors, lively movements and melodious songs, play a unique role in bridging human mental realms and nature, especially by positively influencing human well-being. Hammoud et al. (2022) suggest that everyday encounters with birds can enhance mental health for both healthy individuals and those diagnosed with depression. Remarkably, only 30 min of birdwatching can boost happiness and reduce stress even more effectively than walking in nature (Peterson et al. 2024). Additionally, soundscapes created by birds help mitigate the negative effects of urban traffic noise, improve well-being and restore individual attention (Zhang et al. 2017; Ferraro et al. 2020; Uebel et al. 2021). Through visual and auditory appeal, birds also serve as a wellspring of inspiration and creativity for art, literature and music (Head 1997; Reason and Gillespie 2023; Vuong and Nguyen 2023a; Vuong 2024). Recognizing the vital role birds play in human lives helps cultivate people’s connection with nature and inspire meaningful efforts to protect them and preserve the ecosystems that sustain them.

However, also due to these benefits that birds bring to humans, bird-keeping for entertainment has become a culturally ingrained activity in countries with large populations and high bird diversity, such as Brazil, Indonesia and Vietnam (Jepson and Ladle 2009; Alves et al. 2010; Mirin and Klinck 2021; Nguyen 2021).

In Vietnam, keeping birds for entertainment is a long-standing tradition closely tied to social status. Oral history suggests that the upper-class feudal elite favored more exotic species, shaping early ideals of affluence. This is reflected in the saying: ‘Giàu chơi cá, khá chơi chim’ that literally means, ‘The rich entertain with fish, the middle-class has bird play’ (Nguyen 2021). The revival of interest in traditional pastimes, rising income and increased market availability have led to a resurgence in bird-keeping in recent years, particularly among urban middle-class men (Le and Craik 2016; Eaton et al. 2017; Nguyen 2021).

Although direct knowledge of which bird species are most commonly kept is challenging to obtain, indirect knowledge may be obtained through the availability of birds in bird shops and from vendors. One of the largest studies conducted regarding bird market inventories in Vietnam is the 2016 survey by TRAFFIC that yielded a count of 8047 birds of 115 species in 52 bird shops and vendors in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh (Eaton et al. 2017). Among the species tallied, the most commonly traded species were Scarly-breasted Munia (Lonchura punctulate), Red-whiskered Bulbul (Pycnonotus jocosus), Japanese White-eye (Zosterops japonicus), Red-breasted Parakeet (Psittacula alexandri), Chinese Hwamei (Garrulax canorus), Pied Bush Chat (Saxicola caprata), Spotted Dove (Streptopelia chinensis), White-rumped Shama (Copsychus malabaricus), Eurasian Tree Sparrow (Passer montanus) and Oriental Magpie-Robin (Copsychus saularis). Since 2016, the most common demand has seemed to remain reasonably stable. In the survey conducted from July 2023 to April 2024 in 35 bird shops and markets in five Central Coast provinces, including Thua Thien Hue, Da Nang, Quang Nam, Binh Dinh and Khanh Hoa, Swinhoe’s White-eye (Zosterops simplex), Red-whiskered Bulbul and Oriental Magpie Robin were the three most numerous trading birds among 1601 individuals of 53 species counted (Thang et al. 2024).

The birds are traditionally kept in small cages that are ornamental rather than secure. Our rapid survey of cage types sold on Lazada, one of the largest e-commerce platforms in Vietnam, showed that among 26 cage products sold more than 100 times, most were square cages (73.07%). This aligns with Nguyen (2021)’s ethnographical study finding that a square cage, with a center bridge for perching and two small teacups often clipped on the opposite sides of the door for food and water, is preferred as this is parallel to prevalent Feng Shui ideas regarding prosperity. These cages are often made from locally available, durable wood and can cost approximately three-quarters of an average bird’s price. Cage appearance and size vary according to the bird keepers’ aesthetic requirements and financial means (Nguyen 2021) (see Fig. 1).

Photograph of a square cage sold more than 1500 times by 11th March 2025 (accessed on 10 March 2025).

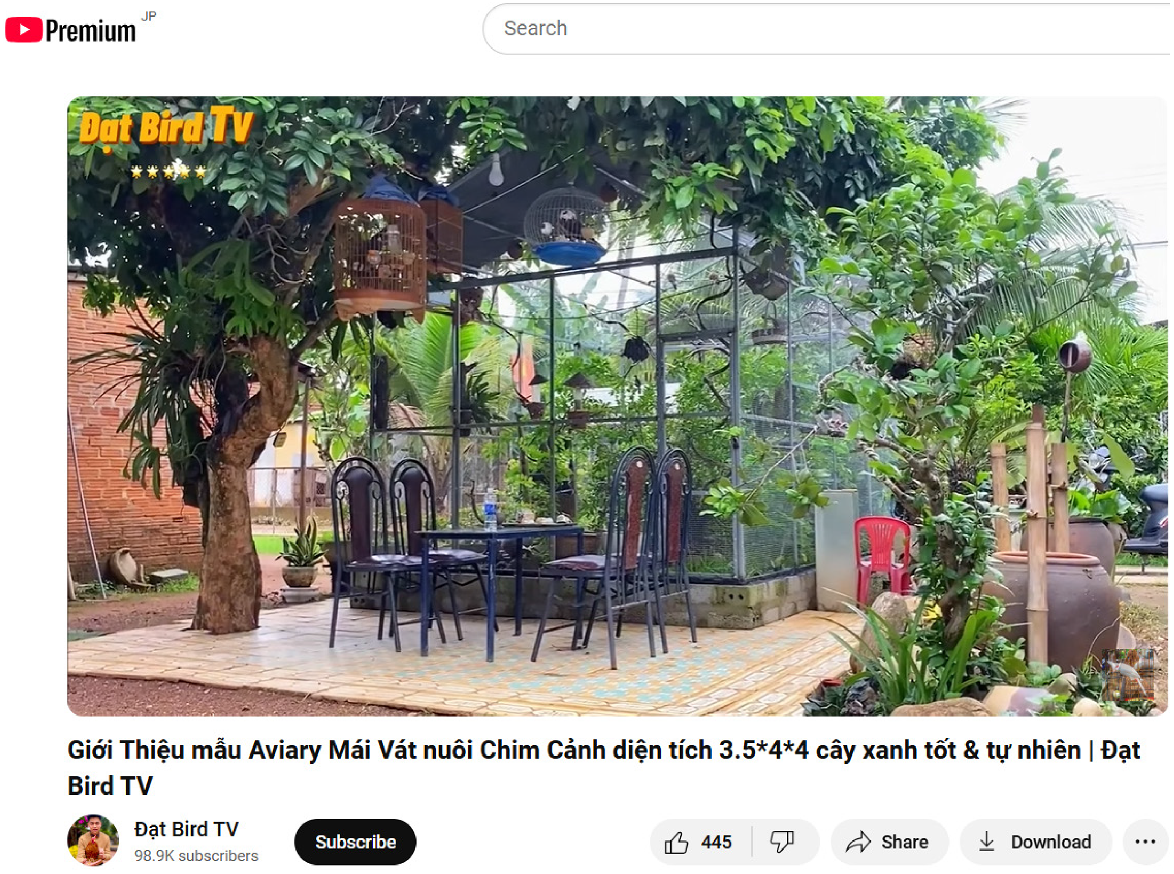

Formerly, there was hope that as societies advanced, greater awareness of conservation issues and the urgency of biodiversity loss would lead people to appreciate the intrinsic and ecological value of birds. This, in turn, would inspire efforts to protect avian habitats and mitigate human impacts on these ecosystems. Ironically, however, this increasing awareness has fueled a new form of entertainment in Vietnam: aviary bird-keeping. Traditionally, small cages housed only one or two birds but these are currently being replaced by larger, intricately designed aviaries capable of accommodating multiple birds to create a space filled with melodious birdsong, immersing people in a sense of the wild (see Fig. 2). Bird-keeping has evolved beyond mere entertainment and socialization (Nguyen 2021) – enthusiasts are increasingly conscious of the importance of bird conservation. This shift in perspective is evident in the words of a seasoned aviary bird-keeper in Ho Chi Minh, who shared the deeper motivation for keeping birds with a reporter (Phương 2012):

More importantly, keeping an aviary is not just about enjoying birdsong—it’s also an opportunity to observe how they behave in a natural environment. Through this, we cultivate a love for nature, an appreciation for wildlife, and a willingness to protect them.

The video introduces an approximately 16 m2 bird-keeping aviary. This was recommended by Google when searching for the term ‘nuôi chim aviary’ (‘aviary bird-keeping’) (accessed on 11 March 2025).

Given the rapid expansion of aviary bird-keeping as a form of entertainment in Vietnam, we seek to expose the absurdity of bird keepers claiming to love nature and contribute to conservation while engaging in practices that exploit and commodify birds for human interests. Furthermore, we highlight the role of an eco-deficit culture – or more profoundly, human insatiable greed in giving rise to such an absurd form of ‘nature love.’

The absurdity of human love

The primary motivation driving aviary bird-keeping enthusiasts is often claimed to be a ‘love for nature’ (Phương 2012). Many aviary bird-keepers argue that the ability to enjoy the beauty and sounds of birds all day without traveling to natural areas fosters a love for nature, a fondness for wildlife and a willingness to protect these (Phương 2012; Bảo 2024). However, these bird keepers intentionally or unintentionally overlook the fact that the demand for birds to fill these aviaries exacerbates the illegal hunting and trade of wild birds – key drivers of biodiversity loss and the expansion of ‘silent forests.’

A rapid survey conducted across 36 bird shops in Ho Chi Minh City, Da Lat, Di Linh (Lam Dong), Pleiku (Gia Lai) and Kon Tum by Wildtour and Birdlife International in October 2024 found a total of 5584 individuals from 82 bird species being sold (Bảo 2024). Beyond physical stores, research by the Monitor Conservation Research Society has also highlighted the rapid growth of the online bird trade through social media platforms (Leupen et al. 2022). Rare bird species have also been recorded at bird shops, driven by enthusiasts willing to spend increasingly large sums of money to acquire these. These include species listed as Critically Endangered (e.g. Yellow-breasted Bunting – Emberiza aureola), Endangered (e.g. Sun Conure – Aratinga solstitialis) and Vulnerable (e.g. Java Sparrow – Lonchura oryzivora, Chattering Lory – Lorius garrulus flavopalliatus) on the IUCN Red List, and species protected under Vietnamese law, specifically Decree 32/2006/ND-CP and later Decree No. 84/2021/ND-CP (e.g. Silver Pheasant – Lophura nycthemera annamensis, Alexandrine Parakeet – Psittacula eupatria, Blossom-headed Parakeet – Psittacula roseate, Red-breasted Parakeet – Psittacula alexandri, White-rumped Shama – Copsychus malabaricus, Red-billed Leiothrix – Leiothrix lutea and Orange-breasted Laughingthrush – Garrulax annamensis) (Eaton et al. 2017; Thang et al. 2024).

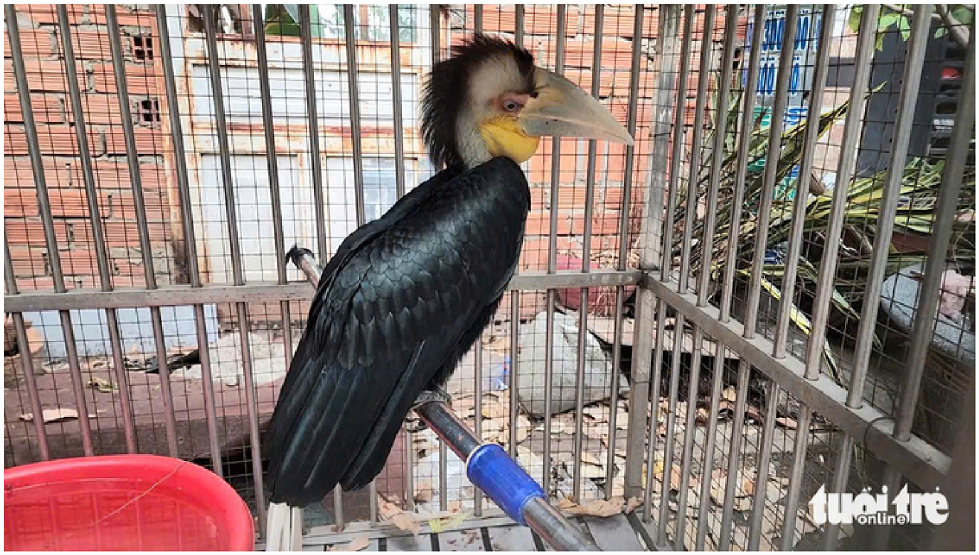

Despite claiming that the passion for aviary bird-keeping arises from a love for birds and nature, many enthusiasts persist in keeping birds despite knowingly lacking the necessary knowledge or suitable conditions to ensure the birds’ survival (Bảo 2024). Even if the birds survive in captivity, the continued well-being and survival largely depend on the owner’s emotional and financial commitment. Once that passion wanes or finances run low, the birds are frequently discarded to reduce costs. In the best-case scenario, birds are passed on or gifted to another keeper. In the worst-case scenario, birds are released into the wild without consideration of the ability to adapt to new environments (see Fig. 3).

A Wreathed Hornbill (Rhyticeros undulatus) captured by local residents in Ho Chi Minh City that may have either escaped from captivity or been released into the wild by bird keepers (Khải and Vi 2024).

The pursuit of aviary bird-keeping to satisfy personal desires under the guise of ‘loving birds’ and ‘loving nature’ starkly illustrates the absurdity of self-proclaimed bird lovers (Nguyen 2024). This practice not only contradicts genuine conservation efforts but also reflects a misguided and abusive relationship with the natural world.

Is aviary bird-keeping beneficial for conservation?

Despite the negative consequences of aviary bird-keeping, many enthusiasts continue to believe that actions undertaken support conservation, reasoning that adequate food and shelter are provided for the birds. Even if we were to assume that this claim was true (though this is not), considering the comparative value of this form of conservation versus preserving birds in natural habitats is essential. Clarifying that this comparison specifically addresses aviary bird-keeping for entertainment rather than legitimate conservation breeding programs is important. The latter aims to breed endangered species in captivity with the ultimate goal of preventing extinction and ideally, reintroducing animals into the wild. There have been several significant efforts in which aviculture has genuinely contributed to conservation efforts, including breeding programs for the Vietnamese Pheasant (Lophura edwardsi) (Collar 2020).

The value of a species lies in interactions with the surrounding environment and other species with which there is interaction (Vuong and Nguyen 2024a, 2024b). When birds are confined in aviaries, the value generated is primarily for human interest. Directly, bird-keeping offers a convenient way to relieve stress, enhance well-being and provide inspiration through the birds’ aesthetic and auditory appeal. Indirectly, birds help people display social status, power, knowledge or even economic benefits. In the Vietnamese context, where Confucian values are deeply ingrained and face-saving plays a crucial socio-psychological role, the benefits of displaying social status, power and knowledge are even more significant (Nguyen and Jones 2022). These displays not only help individuals gain attention and admiration (‘make face’) but also allow the covering of weaknesses through passive impression management (‘keep face’) (Hwang and Han 2010). Bird contests, for example, serve as a popular avenue through which enthusiasts achieve these social rewards through bird-keeping.

In a series of semi-structured interviews with Red-whiskered Bulbul keepers, Nguyen (2021) highlighted the inherently exploitative nature of the human-bird relationship, revealing how humans exert dominance over the very creatures claimed to be ‘loved’ while failing to regard these as true companions. Nguyen (2021) describes this bond as an ‘obligate companionship,’ in which birds undergo a forced socialization process, becoming entirely dependent on keepers for basic sustenance. Within this dynamic, the birds are treated as commodities – objects that fulfill the owners’ desires for entertainment, social prestige and a symbolic connection to nature.

Bird keepers maintain Bulbuls in a state of categorical liminality: neither fully wild nor integrated into the household as a pet. Unlike domestic animals, these birds are rarely given individual names that reflect a unique personality, nor consistently cared for until death or mourned upon passing. When a Bulbul does receive a name, this is usually derived from physical traits that mark the past victories in contests. However, this naming is not an acknowledgement of the bird’s individuality but rather a means of distinction from other captives while showcasing the keeper’s expertise – the bird’s worth is primarily a reflection of the trainer’s skill. In many ways, these birds function as investments, requiring time, money and effort, yet primarily serving as a medium for keepers to engage with a like-minded community, reinforcing social cohesion and ‘face’ values. Once a Bulbul is deemed too old to fight or the song too hoarse to be prized, the bird is often relegated to the status of living ornament. As keepers’ enthusiasm wanes, some birds are left to live out days in ornate cages, serving as status symbols much like trophies, while others are simply released back into the wild (Nguyen 2021).

In contrast, when birds are preserved in natural habitats, the value created directly contributes to the ecosystem. For example, sunbirds, often used in bird contests, play vital roles in South-east Asia’s ecosystems by dispersing seeds and controlling insect populations (see Fig. 4). These ecological functions provide indirect benefits to humans by ensuring environmental sustainability and maintaining biodiversity (Rogers 2019). In other areas where sunbirds serve as pollinators, the contribution to the ecosystem and human survival needs is even more significant. In particular, in African ecosystems, sunbirds pollinate 44% of plant species utilized by humans for medicine, food, building materials and other purposes (Newmark et al. 2020). Some bird species also hold scientific significance, serving as ecological indicators, such as kingfishers (Vuong and Nguyen 2023a).

Sunbird, a species that is frequently used in bird contests due to the natural beauty (Bảo 2024).

Apart from all these benefits, people can still enjoy the beauty and songs of birds in the wild, where bird calls, interwoven with those of other species, create a rich and harmonious landscape and soundscape (Reason and Gillespie 2023). While encountering such moments in nature often depends on good fortune, this unpredictability enhances the value of nature. A fundamental principle of economics indicates that scarcity creates value. The rarity of hearing birdsong or witnessing natural bird behaviour in the wild makes these experiences far more meaningful than observing birds confined to aviaries, where the species are always available on demand.

The persistence of eco-deficit culture and a call for further research

The comparison above highlights eco-deficit cultural values among the Vietnamese people and possibly among people in similar circumstances elsewhere (i.e. the abusive relationship with the birds). The concept of eco-deficit culture describes a paradigm in which the unsustainable exploitation of nature for socio-cultural, political and economic gains is normalized and systematically embedded within economic, political and socio-cultural structures (Vuong and Nguyen 2024a; Vuong et al. 2024). People driven by these cultural values tend to prioritize personal interests over environmental sustainability, thereby fostering cultural forms that harm the environment (i.e. aviary bird-keeping for entertainment and social cohesion). This cultural system reinforces human greed, not only in exploiting nature for survival needs but also, even when survival pressures are alleviated (as bird keepers are typically wealthier individuals), people continue to dominate nature for selfish pleasures, neglecting the burdens nature has to bear (Vuong and Nguyen 2024a). In the context of worsening climate change and biodiversity loss, these cultural values become even more dangerous by pushing humanity closer to demise by destroying the ecosystem that provides sustenance (Diamond 2011).

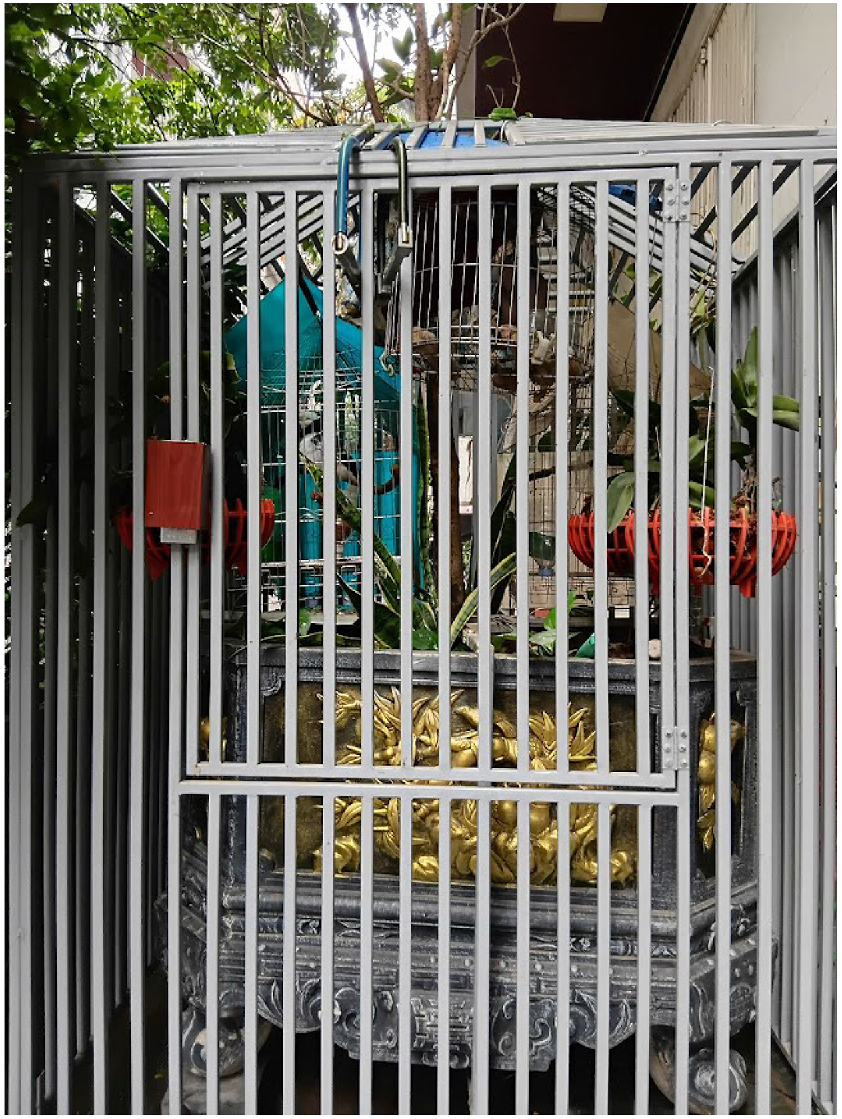

To shift away from this eco-deficit cultural system, more efforts are needed to lead people to realize that love for nature should benefit both nature and humans, not only humans. In a relationship, love that only satisfies the needs of one party may be considered abusive (see Fig. 5). Clearly, an abusive relationship cannot be sustainable!

The birdcages are secured within a steel enclosure and carefully locked to protect the birds from theft. The author titles this photo as ‘Prison of Love’ (taken by Q.-H.V.).

An essential step toward changing the absurd nature love among aviary bird-keepers is to conduct more conservation research on this issue. Research in the humanities and social sciences is crucial as this supports policymakers and conservationists in navigating human interaction with nature, enabling people to love nature conscientiously. Thinking and acting conscientiously, based on reliable scientific information and guidance, is a vital foundation for creating an eco-surplus culture – one that prioritizes the sustainability of nature over selfish human needs (Vuong and Nguyen 2024c). This culture should be the cultural system upheld by sincere nature lovers.

While research takes time, immediate measures can be implemented to prevent the negative impacts of the eco-deficit culture on populations and diversity of bird species, and facilitate the shift from an eco-deficit culture to an eco-surplus culture. One of the most critical areas for intervention is policy and governance, where stronger regulations are needed to curb the exploitation of wild birds, particularly endangered species. The widespread lack of awareness among shop owners and vendors regarding government decrees and directives, along with the continued presence of critically endangered species such as the Yellow-breasted Bunting (Emberiza aureola) in bird markets, highlights significant gaps in law enforcement and regulatory oversight (Thang et al. 2024). Improving wildlife trade law enforcement is crucial to preventing illegal bird capture and trade while closing loopholes that enable harmful practices to persist. Strengthening enforcement through enhanced surveillance technological applications, stricter monitoring of online marketplaces and harsher penalties for violations can serve as strong deterrents against illegal activities. Indeed, a national survey conducted in 2016–2017, covering 140,723 birds from 346 species across 73 markets in 22 Chinese provinces, revealed a significant decline in the trade volume of bird species protected under China’s Wildlife Protection Law following the implementation of the National Special Enforcement Action (Liang et al. 2024). This decline coincided with intensified inspections at key locations, including wildlife markets, transport routes and restaurants where wild birds were commonly traded.

Additionally, regulations should aim to phase out private ownership of wild birds by implementing financial penalties and restricting aviary bird-keeping to legitimise conservation and rehabilitation initiatives (Nguyen and Jones 2022). To support a transition from exploitative practices to sustainable bird appreciation, policymakers can invest in expanding green spaces with high avian biodiversity and provide financial incentives for conservation-friendly alternatives such as eco-tourism, allowing people to experience birds in natural habitats while actively contributing to biodiversity protection (Nguyen et al. 2011; Oropeza-Sánchez et al. 2025).

Public awareness and education also play a pivotal role in fostering an eco-surplus mindset and reshaping societal attitudes toward birds and nature. Outreach campaigns targeted bird keepers and the relevant social network should directly challenge misconceptions about aviary bird-keeping, exposing the role in biodiversity loss and ecosystem disruption (Jacobson et al. 2015; Doley and Barman 2025; Marshall et al. 2025). Integrating avian conservation into school curricula can cultivate environmental responsibility from an early age, fostering birds and the associated ecosystems as ‘objects of care’ (Şekercioğlu 2012; Nguyen et al. 2024). Educational programs should teach students bird ecology, and about ethical wildlife interactions and the broader significance of biodiversity conservation. Additionally, cultural industries should be encouraged to promote ethical storytelling in media, literature and the arts by portraying birds with intrinsic value in natural habitats rather than as commodities. Such narratives can reshape public perceptions, reinforce the intrinsic value of wildlife, and position environmental conservation and restoration as essential humanistic values of our time (Vuong and Nguyen 2023a, 2023b; Marshall et al. 2025).

Another vital strategy is community-based conservation that empowers local populations to take an active role in protecting birds and the associated habitats. Supporting bird-friendly ecotourism initiatives can provide sustainable economic benefits to communities while promoting conservation (Liu et al. 2021). Citizen science programs and local engagement initiatives can empower individuals to monitor and report illegal bird hunting and trade, extending their role beyond simply recording avian biodiversity data (Sullivan et al. 2014). Through fostering grassroots conservation networks, these efforts enhance community involvement in wildlife protection and strengthen enforcement against illegal activities. Moreover, for the reason that many individuals depend on the bird trade as livelihoods, providing alternative career pathways through training and financial support can facilitate a transition to sustainable professions such as ecotourism guiding, conservation work or biodiversity education.

Through these strategies, the theoretical discourse of a shift from an eco-deficit culture to an eco-surplus culture can be translated into meaningful actions. When guided by reliable scientific insights and carefully executed, these actions will foster more sustainable and ethical human relationships with birds – and nature overall – ensuring long-term ecological well-being.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable as no new data were generated or analysed during this study.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, M.-H.N. and Q.-H.V.; formal analysis, M.-H.N.; investigation, M.-H.N.; resources, M.-H.N.; writing – original draft preparation, M.-H.N.; writing – review and editing, M.-H.N. and Q.-H.V.; supervision, Q.-H.V.; and project administration, Q.-H.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

References

Alves RRdN, Nogueira EEG, Araujo HFP, Brooks SE (2010) Bird-keeping in the Caatinga, NE Brazil. Human Ecology 38, 147-156.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Bảo NH (2024) Trào lưu nuôi chim aviary: Chính quyền ở đâu? Available at https://tuoitre.vn/trao-luu-nuoi-chim-aviary-chinh-quyen-o-dau-20241224095934965.htm

Butchart SHM, Stattersfield AJ, Bennun LA, Shutes SM, Akçakaya HR, Baillie JEM, Stuart SN, Hilton-Taylor C, Mace GM (2004) Measuring global trends in the status of biodiversity: Red List indices for birds. PLoS Biology 2, e383.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Collar NJ (2020) Preparing captive-bred birds for reintroduction: the case of the Vietnam pheasant lophura edwardsi. Bird Conservation International 30, 559-574.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Cooke R, Sayol F, Andermann T, Blackburn TM, Steinbauer MJ, Antonelli A, Faurby S (2023) Undiscovered bird extinctions obscure the true magnitude of human-driven extinction waves. Nature Communications 14, 8116.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Doley DM, Barman P (2025) The role of biodiversity communication in mobilizing public participation in conservation: a case study on the greater adjutant stork conservation campaign in Assam, Northeast India. Journal for Nature Conservation 84, 126847.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ferraro DM, Miller ZD, Ferguson LA, Taff BD, Barber JR, Newman P, Francis CD (2020) The phantom chorus: birdsong boosts human well-being in protected areas. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 287, 20201811.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hammoud R, Tognin S, Burgess L, Bergou N, Smythe M, Gibbons J, Davidson N, Afifi A, Bakolis I, Mechelli A (2022) Smartphone-based ecological momentary assessment reveals mental health benefits of birdlife. Scientific Reports 12, 17589.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Head M (1997) Birdsong and the origins of music. Journal of the Royal Musical Association 122, 1-23.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Jepson P, Ladle RJ (2009) Governing bird-keeping in Java and Bali: evidence from a household survey. Oryx 43, 364-374.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Khải N, Vi A (2024) Người dân muốn nuôi chim aviary làm cảnh, kiểm lâm và luật sư khuyến cáo gì? Available at https://tuoitre.vn/nguoi-dan-muon-nuoi-chim-aviary-lam-canh-kiem-lam-va-luat-su-khuyen-cao-gi-20241231110212441.htm

Le MH, Craik RC (2016) Notes on the trading of some threatened and endemic species from Vietnam. BirdingASIA 26, 17-21.

| Google Scholar |

Leupen BTC, Gomez L, Nguyen MDT, Shepherd L, Shepherd CR (2022) A brief overview of the online bird trade in Vietnam. Asian Journal of Conservation Biology 11, 176-188.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Liang Z, Hu S, Zhong J, Wei Q, Ruan X, Zhang L, Lee TM, Liu Y (2024) Nationwide law enforcement impact on the pet bird trade in China. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 121, e2321479121.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Liu T, Ma L, Cheng L, Hou Y, Wen Y (2021) Is ecological birdwatching tourism a more effective way to transform the value of ecosystem services?—a case study of birdwatching destinations in Mingxi County, China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, 12424.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Marshall H, Collar NJ, Lees AC, Moss A, Yuda P, Marsden SJ (2025) Messaging with appeal to intrinsic or relational values shows potential to shift demand for wildlife as pets. People and Nature 7, 4-14.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Mirin BH, Klinck H (2021) Bird singing contests: looking back on thirty years of research on a global conservation concern. Global Ecology and Conservation 30, e01812.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Newmark WD, Mkongewa VJ, Amundsen DL, Welch C (2020) African sunbirds predominantly pollinate plants useful to humans. The Condor 122, duz070.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Nguyen NH (2021) Bird play: raising red-whiskered bulbuls and (re) inventing urban ‘nature’in contemporary Vietnam. Contemporary Social Science 16, 57-70.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Nguyen M-H (2024) How can satirical fables offer us a vision for sustainability? Visions for Sustainability 23, 11267 1-6.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Nguyen M-H, Jones TE (2022) Predictors of support for biodiversity loss countermeasure and bushmeat consumption among Vietnamese urban residents. Conservation Science and Practice 4, e12822.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Nguyen LHS, Le Trung D, Nguyen TV (2011) Developing bird watching ecotourism combined with education and natural conservation. VNU Journal of Science: Earth and Environmental Sciences 27, 89-97.

| Google Scholar |

Nguyen M-H, Le T-T, Vuong Q-H (2023a) Ecomindsponge: a novel perspective on human psychology and behavior in the ecosystem. Urban Science 7, 31.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Nguyen M-H, Nguyen M-HT, Jin R, Nguyen Q-L, La V-P, Le T-T, Vuong Q-H (2023b) Preventing the separation of urban humans from nature: the impact of pet and plant diversity on biodiversity loss belief. Urban Science 7, 46.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Nguyen M-H, Duong M-PT, Nguyen Q-L, La V-P, Hoang V-Q (2024) In search of value: the intricate impacts of benefit perception, knowledge, and emotion about climate change on marine protection support. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences 15, 124-142.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Oropeza-Sánchez MT, Solano-Zavaleta I, Cuandón-Hernández WL, Martínez-Villegas JA, Palomera-Hernández V, Zúñiga-Vega JJ (2025) Urban green spaces with high connectivity and complex vegetation promote occupancy and richness of birds in a tropical megacity. Urban Ecosystems 28, 50.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Peterson MN, Larson LR, Hipp A, Beall JM, Lerose C, Desrochers H, Lauder S, Torres S, Tarr NA, Stukes K, Stevenson K, Martin KL (2024) Birdwatching linked to increased psychological well-being on college campuses: a pilot-scale experimental study. Journal of Environmental Psychology 96, 102306.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Phương H (2012) Vườn chim trong nhà phố. Available at https://plo.vn/vuon-chim-trong-nha-pho-post57220.html

Reason P, Gillespie S (2023) The teachings of mistle thrush and kingfisher. Australian Journal of Environmental Education 39, 293-306.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Rogers L (2019) Anthreptes malacensis: Brown-throated sunbird. Available at https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Anthreptes_malacensis/

Rosenberg KV, Dokter AM, Blancher PJ, Sauer JR, Smith AC, Smith PA, Stanton JC, Panjabi A, Helft L, Parr M, Marra PP (2019) Decline of the North American avifauna. Science 366, 120-124.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Şekercioğlu ÇH (2012) Promoting community-based bird monitoring in the tropics: Conservation, research, environmental education, capacity-building, and local incomes. Biological Conservation 151, 69-73.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Sullivan BL, Aycrigg JL, Barry JH, Bonney RE, Bruns N, Cooper CB, Damoulas T, Dhondt AA, Dietterich T, Farnsworth A, Fink D, Fitzpatrick JW, Fredericks T, Gerbracht J, Gomes C, Hochachka WM, Iliff MJ, Lagoze C, La Sorte FA, Merrifield M, Morris W, Phillips TB, Reynolds M, Rodewald AD, Rosenberg KV, Trautmann NM, Wiggins A, Winkler DW, Wong W-K, Wood CL, Yu J, Kelling S (2014) The ebird enterprise: an integrated approach to development and application of citizen science. Biological Conservation 169, 31-40.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Thang H, Trung LNT, Hung LM, Hoa NN, Thach ND, Giang HTC (2024) Wild birds traded in the central coastal provinces, vietnam. Hue University Journal of Science: Agriculture and Rural Development 133, 49-64.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Uebel K, Marselle M, Dean AJ, Rhodes JR, Bonn A (2021) Urban green space soundscapes and their perceived restorativeness. People and Nature 3, 756-769.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Vuong Q-H, Nguyen M-H (2023a) Kingfisher: contemplating the connection between nature and humans through science, art, literature, and lived experiences. Pacific Conservation Biology 30, PC23044.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Vuong Q-H, Nguyen M-H (2023b) How an age-old photo of little chicks can awaken our conscience for biodiversity conservation and nature protection. Visions for Sustainability 253-264.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Vuong Q-H, Nguyen M-H (2024b) Further on informational quanta, interactions, and entropy under the granular view of value formation. The VMOST Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Vuong Q-H, Nguyen M-H (2024c) Call Vietnam mouse-deer ‘cheo cheo’ and let empathy save them from extinction: a conservation review and call for name change. Pacific Conservation Biology 30, PC23058.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Vuong Q-H, La V-P, Nguyen M-H (2024) Weaponization of climate and environment crises: risks, realities, and consequences. Environmental Science & Policy 162, 103928.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Zhang Y, Kang J, Kang J (2017) Effects of soundscape on the environmental restoration in urban natural environments. Noise and Health 19, 65-72.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |