Animal husbandry and animal production activities in village institutes, an important educational institution for social and economic development in Türkiye

Sefa Yıldırım A * and Berfin Melikoğlu Gölcü

A * and Berfin Melikoğlu Gölcü  B

B

A

B

Abstract

After the foundation of the Republic of Türkiye, the most important problems of the country were education and economic problems. The fact that most of the uneducated population lived in villages and that agriculture and animal husbandry, the main elements of the country’s economy, were mainly conducted in rural areas created an opportunity for village institutes. The village institutes aimed to train prospective teachers as educators and well-rounded individuals who would set an example for the village community. For this reason, in addition to theoretical knowledge, students were given practical training in agriculture, animal husbandry, construction, health knowledge, carpentry, etc., based on scientific knowledge. Animal husbandry and animal food-production activities, part of this comprehensive education, were widely practiced in village institutes. In this way, both the students received a modern agricultural education, and the food resources of the institutes were provided. In this study, animal husbandry and animal food production activities in the village institutes, which were established in various regions of Türkiye and harboured an education system far beyond its period, were analysed and the aim was to provide information on this subject.

Keywords: animal husbandry, animal production, applied agriculture, applied education, education, food production, sustainable agriculture, village institutes.

Introduction

One of the primary objectives of the Republic of Türkiye, established as a country of agriculture and animal husbandry, was the development of agricultural and animal production, which had declined during the war years. In addition to agricultural regulations, essential steps were taken, especially in higher education, to protect animal existence and expand and improve animal breeding. In 1933, this process, which started with the Higher Agricultural Institute, the only institution to train veterinarians, was continued in higher education and at all levels of education (Erk 1961; Şimşek and Mercanoğlu 2018). However, one of the most critical problems encountered on this path was the low literacy rate. Despite all the efforts made in education and training, only 21% of the population was literate in 1935, far below the targeted level of education and training (Şeren 2008). In addition, during the Ottoman period and in the early years of the Republic, people were divided into peasants and urbanites, constituting two different masses that were wholly independent and disconnected from each other (Esen and Akandere 2021). Although most of Türkiye’s population lives in villages, the feudal structure and traditional loyalties in rural areas have prevented the Republican revolutions from reaching the grassroots, and the desired modern development in villages achieved. For this purpose, various institutions were established, and an educational mobilisation was launched to educate the people and develop the country, in metropolitan cities and in rural areas (Güvercin et al. 2004; Özkan 2021).

Practical solutions resorted to teaching the villagers literacy and meeting the need for ‘village teachers’. In 1936, ‘village instructor courses’ were started to be opened, and it was decided that the instructor candidates who studied in these courses would be sent to the villages to teach reading and writing after completing their 6–8 months of training (Özkan 2016; Sarı and Uz 2017). The Village Instructor Courses led to the conclusion that it would be more appropriate to provide education and training activities within a specific order and in a formal educational institution. Accordingly, ‘village teacher training schools’ were opened in 1937, and village teachers began to be trained in these schools, which operated simultaneously (Berktaş 2019).

The positive results obtained from the village instructor courses and village teacher training schools were decisive for a more comprehensive method to be followed in the education system, and formed the origin of the idea of ‘village institutes’ proposed by İsmail Hakkı Tonguç, the General Director of Primary Education of the period. This proposal, which was also supported by Hasan Âli Yücel, the Minister of Education at the time, aimed not only to teach the villagers to read and write but also to train teachers who understood the people living in village conditions and their needs, to integrate modern agriculture and animal husbandry practices into villages, and to strengthen the village society by using its resources (Güvercin et al. 2004; Aysal 2005; Akandere 2019). To achieve this goal, boys and girls between the ages of 13 and 15 who would be enrolled in village institutes were required to have completed primary school, to be children of farmers, to have land and animal husbandry in the villages of their families, and to be in good health (Arslan 2012).

On 22 April 1940, the enactment of the ‘Law on Village Institutes’ (Official Gazette 1940) paved the way for the establishment of institutes in or near villages with large areas of land suitable for agriculture and animal husbandry (Özkan 2016). The Law defined these institutes as ‘institutions opened by the Ministry of National Education to train village teachers and other professionals useful for the village’ (Official Gazette 1940, p. 2). Originally planned to open 20 village institutes, each covering three to four provinces, 21, in total, were opened until 1948 (Table 1; Fig. 1). In addition to their duties related to schools and courses, the teachers who graduated from these schools were also assigned to train the villagers in various needed subjects (Official Gazette 1942; Kartal 2008).

| Order of establishment | Name of institution | Date of establishment | Today’s locations (Province, District) | Prominent animal husbandry and production activities | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Çifteler Village Institute | 17 April 1940 | Eskişehir, Mahmudiye | Horse breeding, sheep and goat breeding, cattle breeding, poultry farming, beekeeping; milk, yogurt, cheese production | |

| 2 | Gölköy Village Institute | 17 April 1940 | Kastamonu, Merkez | Sericulture, beekeeping, poultry farming, cattle breeding; milk, cheese production | |

| 3 | Kepirtepe Village Institute | 17 April 1940 | Kırklareli, Lüleburgaz | Beekeeping, poultry farming | |

| 4 | Kızılçullu Village Institute | 17 April 1940 | İzmir, Buca | Sericulture, cattle breeding, sheep and goat breeding, poultry farming, beekeeping; oil, milk, cheese production | |

| 5 | Akçadağ Village Institute | 7 July 1940 | Malatya, Akçadağ | Sheep and goat breeding, cattle breeding, horse breeding, poultry farming, yogurt production | |

| 6 | Akpınar Village Institute | 11 June 1940 | Samsun, Ladik | Beekeeping, cattle breeding, horse breeding, poultry farming, milk production, fishery | |

| 7 | Aksu Village Institute | 6 June 1940 | Antalya, Aksu | Sheep and goat breeding, cattle breeding, poultry farming, beekeeping, horse breeding, milk and dairy production, yarn making | |

| 8 | Arifiye Village Institute | June 1940 | Sakarya, Arifiye | Fishery, fish canning/brine production, cattle breeding, sheep and goat breeding, poultry farming, beekeeping, sericulture | |

| 9 | Beşikdüzü Village Institute | 25 June 1940 | Trabzon, Beşikdüzü | Fishery, fish canning/brine production, sericulture, beekeeping | |

| 10 | Cılavuz Village Institute | July 1940 | Kars, Susuz | Cattle breeding, sheep and goat breeding, horse breeding, beekeeping, poultry farming; milk, cheese, yogurt and oil production | |

| 11 | Düziçi Village Institute | 25 July 1940 | Osmaniye, Düziçi | Horse breeding, cattle breeding, sheep and goat breeding, poultry farming, beekeeping, sericulture | |

| 12 | Gönen Village Institute | 5 July 1940 | Isparta, Gönen | Wool spinning and yarn production, cattle breeding, sheep and goat breeding, milk production, poultry farming, beekeeping, yogurt and cheese production | |

| 13 | Pazarören Village Institute | 26 August 1940 | Kayseri, Pınarbaşı | Horse breeding, cattle breeding, sheep and goat breeding, poultry farming, beekeeping; milk, yogurt, cheese and oil production | |

| 14 | Savaştepe Village Institute | 20 June 1940 | Balıkesir, Savaştepe | Horse breeding, cattle breeding, sheep and goat breeding, poultry farming, beekeeping, milk production | |

| 15 | Hasanoğlan Village Institute | 10 April 1941 | Ankara, Elmadağ | Sheep and goat breeding (especially Angora goat), cattle breeding, horse breeding, beekeeping, poultry farming | |

| 16 | İvriz Village Institute | 11 November 1941 | Konya, Ereğli | Beekeeping, sheep and goat breeding, poultry farming | |

| 17 | Pamukpınar Village Institute | 13 May 1942 | Sivas, Yıldızeli | Cattle breeding, poultry farming and milk, yogurt, cheese production | |

| 18 | Pulur Village Institute | 13 August 1942 | Erzurum, Aziziye | Milk, cheese and yogurt production | |

| 19 | Dicle Village Institute | 1 June 1944 | Diyarbakır, Ergani | Cattle breeding, sheep and goat breeding | |

| 20 | Ortaklar Village Institute | 18 August 1944 | Aydın, Germencik | Milk production, poultry farming | |

| 21 | Ernis Village Institute | 1948 | Van, Muradiye | – |

Many articles, theses, books, albums, etc., have been published on the establishment and functioning of village institutes, which have an essential place in the education system of the Republic of Türkiye. Among these publications, there are also studies (Özel 1997; Türkoğlu 1997; Güneri 2004; Turan 2009; Yiğit and Menteş Gürler 2016; Gümüşoğlu 2017; Akandere 2019) based on oral-history sources that provide information about the education and training program on agriculture and animal husbandry, which constitutes one of the cornerstones of the village institutes. This review aims to focus on the education and training activities on agriculture and animal husbandry in the village institutes operating between 1940 and 1954, as well as the activities of the institutes where animal husbandry and animal production were intensively conducted and to present this information with photographs.

Teaching programs in village institutes

Although the village institutes started their education activities in 1940, a joint education program was not implemented until 1943. The institutes operating in this process implemented the programs they prepared at the beginning of each academic year after receiving approval from the Ministry of Education (Şeren 2008; Toprak 2008).

The institutes followed a standard curriculum program for the first time in 1943, and, within their 5-year education period, courses were taught in the following three main subjects: cultural courses, agricultural courses and studies, and technical courses and studies (Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Maarif Vekilliği 1943). In addition to standard courses, the institutes also offered training in different fields. Established in different regions of the country, the village institutes were based on the same ideological foundations in terms of their founding objectives, methods, and functioning, whereas region-specific practices formed the flexible structure of the educational model (Şimşek and Mercanoğlu 2018; Savaş 2021).

In the curriculum for 1943, the subjects to be taught in agriculture courses and studies were reported as field agriculture, horticulture, arboriculture, orcharding, viticulture and vegetable gardening knowledge, agriculture of industrial plants, zootechnics, poultry knowledge, apiculture, sericulture, fisheries and aquaculture knowledge, and agricultural arts (Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Maarif Vekilliği 1943). These courses aim to teach the cultivation and care of plants and animals by applying them daily (Akandere 2019). Which of these courses would be taught was decided according to the geographical location and conditions of the institutes.

Following the resignation of Hasan Âli Yücel as Minister of Education and the dismissal of İsmail Hakkı Tonguç, the curriculum was reorganised in 1947, and the number and hours of theoretical courses was increased (Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Maarif Vekilliği 1943; T. C. Milli Eğitim Bakanlığı 1947). Akandere (2019) stated that the 1947 program moved away from the understanding of flexibility in teaching activities granted to teachers in the first program. In this context, the main difference distinguishing the new program from the 1943 program was that the hours of agricultural and technical courses were reduced by almost half (Tınal and Bozdağ 2017). In the new program, agricultural courses to be given to students for 5 years were as follows: general and special orcharding, viticulture, vegetable growing, floriculture-arboriculture, general and special field agriculture, general and special zootechnics, apiculture, sericulture, poultry farming, animal diseases, animal and plant materials technologies, agricultural business economics, practical work in various branches of agriculture (T. C. Milli Eğitim Bakanlığı 1947).

Animal husbandry in village institutes

In the village institutes, the principle of learning by living and practicing was taken as the basis of education, and the work undertaken in the activities of the institutes was accepted as both a tool, a goal, and a method. With this approach, in which the collective production model was adopted, the products of the activities of the institute contributed to the cost of education, and they tried to create a civilised educational environment (Türkoğlu 1997; Şimşek and Mercanoğlu 2018). In this context, the activities related to the subject of each course were performed by the students, who were divided into groups and activities were performed in rotation.

According to the 1943 curriculum, it was observed that activities related to animal husbandry in village institutes were taught in agricultural courses and studies (for everyone), whereas activities related to animal production were taught in both agricultural courses and studies (for everyone) and technical courses and studies (only for girls) (Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Maarif Vekilliği 1943). In the 1947 curriculum, it was determined that animal husbandry and animal production activities were covered in agricultural courses and practices (T. C. Milli Eğitim Bakanlığı 1947). In these courses, agriculture and animal husbandry activities, the main elements of village life, were integrated with new information and put into practice. In animal husbandry courses, students were taught how to graze animals, give water, tie animals to plows and carts, and were trained on animal diseases. In addition, students were taught how to produce, store, dry, etc., the products obtained from the animals in the institute (Table 1) (Türkoğlu 1997; Yiğit and Menteş Gürler 2016; Gökdemir 2019). The subjects taught in these courses related to animal husbandry were described in detail in the 1943 and 1947 curricula (Tables 2, 3). Each village institute was given a farm established and operated by the state with a revolving fund. While these enterprises provided students with a field of practice, they also served as a source for the materials (food, yarn, leather, etc.) needed by the institute.

| 1943 Curriculum of the village institutes | ||

|---|---|---|

| Course name | Course content | |

| Zootechnics | The importance of animal husbandry, animal biology, nutrients and preparation for animals, animal care, animal disease management, animal anatomy, ways of utilising fattening animals, nutrients obtained from meat and milk, wool and leather processing, animal breeding, heredity, animal nutrition, animal health, examination of animal drugs, protection measures from pests, animal sales; horse, cattle, sheep, goat and pig breeding | |

| Poultry | Poultry coops, care of poultry, protection from pests in poultry, ways of utilising poultry | |

| Beekeeping and sericulture | Beekeeping: the current situation of beekeeping in the country, the hive type suitable for the characteristics of the country and attempts for the beekeeping system, transfer of bees to the scientific hive, bee breeding in the scientific hive, swarming, change drone, making wax from honeycomb and honeycomb making, honey utilisation methods, honey and nectar yield of plants with high recognition and their production, to recognise and make the scientific hive Sericulture: history of sericulture, its role in our country in terms of production, the place and anatomy of the silkworm in animal classification, silkworm diseases, seed breeding in sericulture, life cycles of silkworms, cocoon and silk production, mulberry cultivation for cocooning | |

| Fisheries and aquaculture | Türkiye’s aquaculture; fishes, their reproduction, hunting; fish preservation methods, fishery industry, aquaculture products | |

| 1947 Curriculum of the village institutes | ||

|---|---|---|

| Course name | Course content | |

| General zootechnics | Economic dimension of animal husbandry and its situation in Türkiye; domestication of animals; species and hybridisation; animal breeds; effects of environment on animals; reproduction in animals; animal breeding; selection; animal feeding; animal care; animal barns; animal husbandry organisations | |

| Special zootechnics | Horse breeding: status and importance in Türkiye, domestic and foreign horse breeds, selection of breeding horses, age determination, horse walking, horse breeding, mule and donkey breeding Cattle breeding: status and importance in Türkiye; domestic and foreign cattle breeds; age determination; selection of breeding cattle; cattle breeding Sheep breeding: status in Türkiye, sheep breeds, examination and selection of sheep, age determination, sheep breeding, information about fleece Goat breeding: status in Türkiye, goat breeds, selection of breeding goats, goat breeding, information about mohair | |

| Aquaculture and fisheries | The importance of fisheries and fisheries in the country’s economy, studies on fisheries in foreign countries, our waters, fish species in our country, fish migrations and their causes, migrating fish and local fish, hunting, domestic and foreign fishing equipment, utilisation of caught fish | |

| Beekeeping | Importance and benefits of beekeeping, bee colony, hives, combs, setting up the apiary, care and feeding of bees, bee production, honey and wax, purchase and transportation of bees, irregularities in a bee colony, bee diseases, bee pests, general health measures in hives | |

| Sericulture | History, importance and place of sericulture in the national economy; silkworm production, silkworm houses and general conditions, care of silkworms, obtaining cocoons, the reason for killing pupae in cocoons, shapes, various cocoons, faulty cocoons, silkworm diseases, obtaining eggs and selection of breeders | |

| Poultry | Importance of poultry, eggs, poultry coops, feeding, production, diseases and pests of poultry, bad habits of poultry, ways to protect poultry, turkey breeding, goose breeding, duck breeding, utilisation of poultry products | |

| Animal diseases | Birth diseases, wounds, fractures, dislocations and foot diseases, pains and bad habits, infectious diseases, parasites, poisoning, measures to be taken against epidemics in infectious diseases | |

| Agricultural technology | Definition and importance of agricultural technology, dairying, yogurt making, butter making, cheese making, leather craft | |

| Agricultural business economics | Capital management in enterprises, capital management in animal husbandry, hunting and fishing | |

The work plan of the village institutes was organised according to the characteristics of each institute, the work, the harmony and number of students, the competence of the teachers, the work tools, the work areas, and the type and number of animals (Türkoğlu 1997). In this context, in the annual agricultural work plan prepared by the Ministry of Education in 1943, the workflow to be performed by students each month was explained in detail, and all activities related to animal husbandry and animal production were included in this plan (Table 4) (Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Maarif Vekilliği 1943).

| Month | Annual agriculture work plan | |

|---|---|---|

| March | 1. Washing the barns and pens with a 2% solution of creolin, scraping the floors of the barns, pouring powdered lime and pouring 5 cm thick clean garden soil. 2. Incubation. 3. Switching bees from barrel hives to scientific hives. 4. Spring feeding and spring inspection of bees (one-third of aqueous syrup and roasted rye flour will be given). 5. Applying tar and creolin incense to sheep against pinworms. | |

| April | 1. Careful care of pregnant mares, cows, and sheep. 2. Anthrax vaccination of sheep, cows, and horses against anthrax. Examination of horses with mallein test against glanders. 3. Sterilisation of stallions, bulls, and male lambs and selection of breeders. 4. Examination of beehives once a week. Pouring comb and preparing frames, replacing combs that are over four years old. 5. Mothballing of hives, to be used against honeycomb moth. | |

| May | 1. Preparation of swarming in hives. 2. Milking one meal of milk from sheep; making yogurt, cheese, cream, and oil. 3. Taking horses to pasture for 15 days. 4. Bringing mares to the stallion. 5. Wax production from old honeycombs and honeycomb pouring. | |

| June | 1. Weaning of lambs. Milking and shearing. 2. Injection of sheep and cattle against piroplasmosis. 3. Preparation of animal manure. 4. Artificial swarming from hives, drone replacement. 5. Washing poultry coops, barns, and pens with 2% creolin solution. | |

| July | 1. Washing of sheep and lambs, washing and shearing of fattening sheep. 2. Egg brine production. | |

| August | 1. Last summer examination of bees. 2. Laying eggs in brine. | |

| September | 1. Feeding sheep green meadow, pasture grass, and plenty of salt so that they can mate at the desired time. 2. Taking measures to ensure the winter needs of the institute and animals. 3. Making the last examinations of the bees. 4. Putting the bees in winter condition and feeding them. 5. Putting the barns, pens, and poultry coops in winter condition. The floors are limed and tightened with clean soil. Washing the ceilings and walls with 2% creolin solution. | |

| October | 1. Winterisation of hives. 2. Breeding separation and releasing rams to the herd. | |

| November | – | |

| December | 1. Building a scientific beehive. 2. Making sheep swallow ‘Distofajin’ drug against butterfly disease. | |

| January | 1. Making beehives, producing beeswax from old honeycombs. 2. Tick examination in young sheep. | |

| February | 1. Taking protection measures against ticks in barns. 2. Applying creolin or juniper tar incense to sheep and goats at least five times every 10 days against pinworm disease. Giving plenty of food and salt. 3. Paying attention to the care and feeding of pregnant sheep and goats. 4. White washing, cleaning, and disinfection of poultry coops and dovecotes; hatching preparation; preparation of chickens for sand and ash baths. 5. Spring examinations of hives if the weather is favourable. |

Among the administrative and teaching staff of the institutes, agricultural heads, fishery heads, and master instructors were among the personnel responsible for animal husbandry activities. Heads of agriculture were assigned to perform the farming and animal husbandry-related work of the institutes. The responsibilities of the heads of agriculture included determining the educational practices and work plans together with the teaching staff, keeping all records related to animal care and the tools and materials required for these works, taking measures to protect animals from infectious diseases together with students and teachers, and trying to eliminate situations that cause the death or injury of animals. Heads of fisheries were tasked with preparing a daily, weekly, monthly, or seasonal work plan and working according to this plan. Their responsibilities included researching ways and means of arousing curiosity and love for fishing among students and teachers, preventing fishing that would harm the fish population, procuring the tools and materials needed for fishing promptly, and keeping relevant records. In contrast, master instructors ensured that students are interested in the field in which they are skilled, are well-trained, and learned by doing (Eser 2011; Altunya 2014).

The agricultural and animal husbandry activities performed in the institutes were shaped according to the climatic conditions of the region, the structure of the land, and the needs of the region, and each institute implemented different strategies within the same ideology in line with its means. It was reported that the main areas of agriculture and animal husbandry in the institutes were generally determined by the teachers in charge of agriculture courses, whereas the tasks assigned to the students were selected by both the head of agriculture and the agriculture teachers (Akandere 2019; Esen and Akandere 2021). However, it is also known that İsmail Hakkı Tonguç, the Director General of Primary Education, was personally involved in the functioning of the institutes, their fields of activity, and the methods to be used, and that the support of the Ministries of Agriculture and Education was received for regular observation of the institutes and the elimination of deficiencies (Kirby 1962; Karadeniz 2019; Esen and Akandere 2021; Özkan 2021). As a matter of fact, during the establishment phase of Beşikdüzü Village Institute, which had a limited and rugged terrain, Tonguç’s statement to Institute Director Hürrem Arman about the production to be undertaken in the Institute, namely, ‘Your field will be the Black Sea,’ led to the main field of activity of the Institute being based on fishing (Ayaz 2019; Karadeniz 2019). Similarly, while Tonguç was visiting Arifiye Village Institute, he was curious about the fishing activities in Lake Sapanca, which is close to the Institute, and the lake was investigated. As a result of the research, the lake was found to be suitable for fishing, which prompted the Institute to take action on fishing (Balkır 1974; Savaş 2021). Again, the fact that the land allocated to Cılavuz Village Institute was suitable for animal husbandry enabled the activities of the Institute to focus on cattle breeding, and approximately 1000 animals were bred (Türkoğlu 1997). In some institutes, the income generated by animal production activities was higher than the state allocation to the institute (Turan 2009). However, since the founding studies, students have operated in solidarity and cooperation, and many products produced in the institutes have been sent to other institutes (TMMOB Ziraat Mühendisleri Odası İzmir Şubesi 1995; Karadeniz 2019).

In the agriculture courses taken by male and female students together, care was taken to select subjects appropriately to the characteristics of the students and to have the work undertaken accordingly. Whereas male students were mainly responsible for caring for the animals in the institute and cultivating the soil in agriculture courses, female students were assigned to produce and preserve food products such as cheese, yogurt, and oil. In addition, when determining the subjects of these courses, the age of the students, as well as gender, was a determining factor. Whereas field agriculture and horticulture courses were at the forefront in the first years of the curriculum, more specific courses such as beekeeping, sericulture, fisheries, and aquaculture were included in the curriculum in the last 2 years (Esen and Akandere 2021).

In lectures and studies on animal care, emphasis was placed on informing the villagers and introducing new methods. These studies were conducted by expert and master instructors from outside the institute. The expertise support needed for animal care and breeding was provided by veterinarians assigned to the districts by the agreement between the Ministries of Education and Agriculture. These veterinarians participated in courses and practices on the subject and contributed to training the institute’s students (Türkoğlu 1997; Aktaş 2006). In addition, in the early years of Hasanoğlan Higher Village Institute, faculty support was received from the Higher Agricultural Institute (which was considered a turning point in agriculture and animal husbandry education and was structured as one of the first university-qualified higher education institutions) for the teaching of animal and animal husbandry-related courses (Dönmez 1945).

Cattle and sheep were generally fed in the institutes. Horses were used as work animals (TMMOB Ziraat Mühendisleri Odası İzmir Şubesi 1995). At least 5–10 pack animals were kept in each institute to carry loads, pull cars, and ride. Horses used as riding animals were mainly used by the agricultural head and the students appointed as the agricultural president, who travelled around the farming areas located far away from each other daily. In addition, mounts were allocated by the institutes to healthcare workers to travel around the villages (Türkoğlu 1997). Türkoğlu (1997) reported that there were more horses in Çifteler and Hasanoğlan Village Institutes and that these horses were bred for the use of teachers who graduated from the institute. During their establishment, they aimed to raise at least as many poultry and half as many cattle as the school population in each institute (Maarif Vekaleti 1941). All kinds of work related to the care of the animals was undertaken by the students together with the caregiver workers (TMMOB Ziraat Mühendisleri Odası İzmir Şubesi 1995; Türkoğlu 1997).

For the ‘poultry farming’ course in the first- and second-year programs, each institute had organised the ‘poultry farming’ studies, which were conducted in a suitable place on the farm, according to its environment and needs. It has been reported that although poultry farming was a course for small classes in the program, students from all classes were allowed to participate in course studies. Caring for chickens, feeding them, incubating them, and delivering their eggs to the institute kitchen or the cooperative were among the tasks covered in the course (Türkoğlu 1997). In the beekeeping field, productive work has been undertaken by combining traditional log and hive beekeeping with the opportunities offered by new techniques. It has been reported that beekeeping teachers, master instructors, and beekeeper students work together (Aktaş 2006). Gölköy, Kepirtepe, and Hasanoğlan Village Institutes were among the institutes where beekeeping was popular (Şimşek and Mercanoğlu 2018).

Fishing activities specific to the region were performed in Arifiye and Beşikdüzü Village Institutes with excellent results. Beşikdüzü and Arifiye Village Institutes went down in history as among the first schools in the history of Turkish education to provide professional training in fisheries (Aça 2019).

In addition to agricultural courses, products obtained from agriculture and animal husbandry were also evaluated in the ‘agricultural arts’ course, which was included in technical courses and studies. These activities, defined as ‘village household and handicrafts’, aimed to educate predominantly female students. The subjects taught in agricultural arts courses were kept flexible within the curriculum. These topics, which generally came to the fore according to the characteristics of the regions, include making yogurt and cheese from the milk of the animals in the institute, methods of extracting fat and storing them, pickling and canning, preparing winter foods from meat and grain, canning and ways to preserve them were included. These field studies were conducted on the basis of the environmental characteristics, the needs of the institution, food affairs, and preparations for the following year. For this reason, it has been reported that the institutes did not suffer from food and clothing shortages, unlike many establishments during the Second World War (Türkoğlu 1997).

Prominent village institutes in animal husbandry activities

Çifteler Village Institute

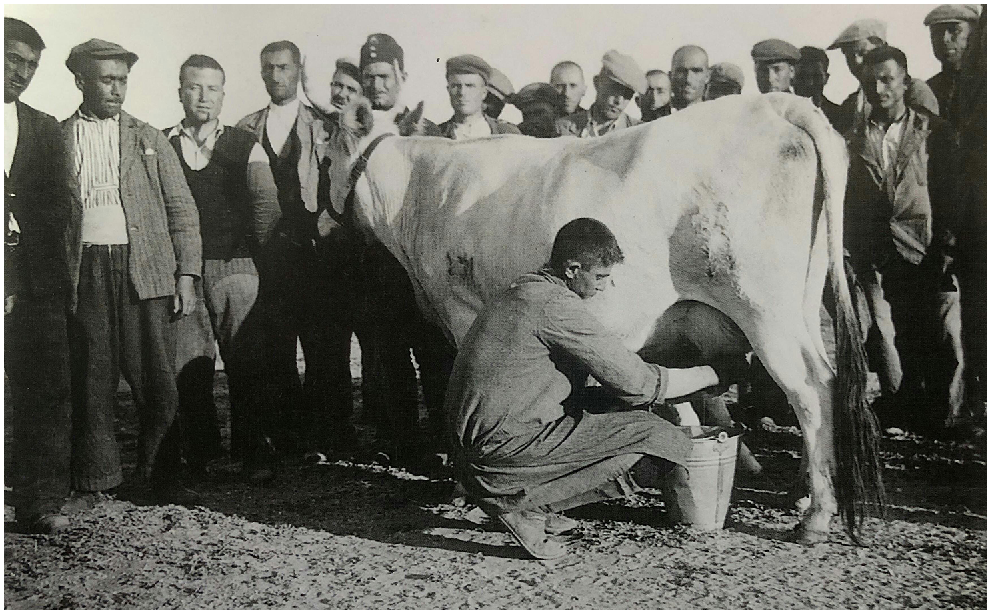

It has been recorded that horse breeding, sheep breeding, cattle breeding, poultry breeding, and beekeeping were practiced at Çifteler Village Institute (Şimşek and Mercanoğlu 2018). According to İnan (1944), the Director of the Institute at the time, the Institute had poultry such as chickens, roosters, geese, ducks, and turkeys, herds of cattle, sheep, and goats, and 110 horses, to be distributed to graduating students. However, it was reported that animal production activities were also performed at the Institute. In addition to milk production, and yogurt, and cheese making, the Institute also produced honey (İnan 1944; Burgaç 2004) (Fig. 2).

A student milking a cow at Çifteler Village Institute (photograph from İsmail Hakkı Tonguç Archives Foundation, photographer unknown, dated between 1940 and 1954).

After the 1944–1945 academic year, it was reported that the Institute had 47 horses, three male foals, four female foals, 250 sheep, 11 cows, 50 chickens, 50 geese, 10 ducks, and six hives of bees. In the same year, with the income obtained by selling 130 sheep and old cows, 10 grey cows and one bull were purchased from the studfarm, and it was recorded that one cow among them gave 4–5 kg of milk per day (Anonim 1946a). Regarding animal production, it was recorded that 627.5 L of milk and 126.5 kg of yogurt were obtained in November 1947, and 5465 kg of milk, 564.25 kg of yogurt, and 33.5 kg of honey were obtained in 1948 (Burgaç 2004).

It was reported that health checks and vaccinations of the animals in the Institute were performed, barns and poultry houses were regularly disinfected, bees and hives were checked at certain times, and horseshoes were applied for horses and oxen in the farm workshop (Burgaç 2004).

Gölköy Village Institute

Kastamonu Gölköy Village Institute was first opened in 1938, providing a village instructor course, and in 1940, it took its place among the first village institutes established in Türkiye (Şensoy 2015). Beekeeping has been among the leading activities of the Institution since the early days of the instructor course. Eser (2012) suggested that beekeeping can be a suitable and popular activity owing to the green and flowery nature of the Ilgaz Mountains and the favourable climatic conditions of this region. For this reason, beekeeping courses were emphasised, and it was aimed that beekeeping would become a source of income in the region and to find a correct and effective application area (Eser 2011, 2012).

It was reported that beekeeping activities (Tables 2, 3), included in the curricula in detail since the village instructor course, could not be implemented sufficiently in 1943 owing to the lack of technical staff, and the course was interrupted. The reports submitted by Gölköy Village Institute to the Ministry of Education stated that beekeeping was a separate specialty from agricultural work and that two students of the Institute were requested to receive training from other institutes to learn practical beekeeping. As a result of this, two students were sent to Kepirtepe Village Institute to specialise in beekeeping (Fig. 3). These students, who returned to Gölköy Village Institute, trained other students in beekeeping and contributed to revitalising the village economy in the following years (Eser 2011). In Gölköy Village Institute, activities related to animal husbandry were reported as sericulture, poultry farming, cattle fattening, and beekeeping, whereas animal production activities were milk production and cheese making (Şimşek and Mercanoğlu 2018) (Fig. 4).

Kızılçullu Village Institute

As one of the first village institutes, Kızılçullu Village Institute had suitable buildings and outbuildings, so that students had the opportunity to start their education and practice activities directly. In 1940, Kızılçullu Village Institute was reported to be an educational complex with hundreds of acres of land, classrooms, workshops, and stables. The program implemented at the Institute, which was prepared by taking into account the needs of the village, was created by taking into account the characteristics of the environment and climate in which the Institute was located, and half of the weekly working time was devoted to agricultural and technical education courses (Tınal 2008; Tınal and Bozdağ 2017). Sericulture and beekeeping practices, which were included in agriculture courses, stand out among animal husbandry activities (Bozdağ 2019).

According to the first education-training program implemented at the Institute, while the students were in an auxiliary position in agricultural courses and practices until the end of the second year, their participation in these practices was ensured from the third year onward, and the courses on sericulture, beekeeping, animal husbandry, and poultry farming gained weight. The following subjects were covered in these courses (Bozdağ 2019):

Sericulture: the benefits of raising insects, insectary equipment, silkworm eggs, insect feeding, bedding, cocoon wrapping, butterfly hatching and egg retrieval, and disease control

Beekeeping: beekeeping knowledge, examination of old hives, transfer from old hive to new hive, queen, drone and worker bees, beekeeping tools, bee care, swarming, honey production, pest control and spraying, opening hives and combing

Animal husbandry: animal husbandry knowledge, barn work, animal milking, feed work, maintenance work, poultry work, hatching, chick care and feeding, poultry garden construction and egg production

Poultry: the value and importance of poultry, poultry house facility, poultry houses, pigeon houses, breeding production, production techniques, egg knowledge, packaging and storage techniques, breeding techniques, feeds and feed arrangements, chicken breeds and breeding, goose, duck, turkey, chicken, pigeon breeding and production, poultry anatomy and physiology, poultry in villages (Fig. 5).

A student is breeding turkeys at the Kızılçullu Village Institute (photograph from İsmail Hakkı Tonguç Archives Foundation, photographer unknown, dated between 1940 and 1954).

Yogurt, buttermilk, cheese, silk, and honey were produced as animal products at the Institute farm (Bozdağ 2019). For the students to continue these activities in the villages where they worked after graduating from the Institute, the tools and equipment made by the students in the workshops were given to the graduates. For this purpose, it was recorded that beehives were given to male students, whereas beehives, weaving looms, spinning wheels, and carpet looms were given to female students (Tınal and Bozdağ 2017).

Akçadağ Village Institute

In Akçadağ Village Institute, sheep and goat breeding, cattle breeding, and poultry farming were practiced. During the establishment phase of the Institute, which started its activities in 1940 with 12 horses and three pairs of oxen (Tekben 1944), it was recorded that there were 61 cattle, 12 horses, six mules, 264 sheep of Karaman breed, 179 lambs and 130 chickens in 1946. It was reported that 60–150 kg of yogurt was obtained every 2 days from the Institute’s sheep on the plateau. It was reported that the veterinarians and animal health officers of Sultansuyu Studfarm assisted in caring for the animals in the Institute (Cengiz 1946).

Akpınar Village Institute

Turan (2009), in her study on Akpınar Village Institute, included the testimonies of the Institute graduates about animal husbandry activities. According to the statements here, it was reported that there were animals such as cows, horses, chickens, and bees in the Institute; 20–25 cows in the barn were of culture breed, and the students took care of these cows by the techniques they learned in the courses, such as milking methods and milk yield. Şimşek and Mercanoğlu (2018) reported that beekeeping activities were prominent at Akpınar Village Institute. Students were trained and modern beehives were made with support from other developed institutes in the field of beekeeping (Anonim 1946c).

In July 1942, fishing activities were started at the Institute. For this purpose, Lâdik Lake, which was 12 km away from the Institute and where fish such as pike, flatfish, and rudd were found, was utilised. A small fishing building was built at the head of Lâdik Lake. Students were sent to the lake in groups of 10 to fish and use boats. It was also reported that the Institute had a fish house in the Derbent neighbourhood of Bafra, where students fished, and some of the fish was sent to the school, whereas the rest was sold to contribute to the school budget (Biriz 1944; Turan 2009).

Aksu Village Institute

It was reported that sheep and goat breeding, cattle breeding, poultry farming, and beekeeping activities were practiced at Aksu Village Institute (Şimşek and Mercanoğlu 2018). It was reported that the Institute has 72 hair goats, five sheep, five horses, two cows, one young bull, and two calves; animal production activities related to dairy and dairy products were performed (Can 2017). According to the studies of Çetin and Kahya (2017), there was a backyard with a capacity of 15–20 horses, a barn with a capacity of 20–30 cattle, and three poultry houses with a capacity of 100 chickens in the Institute area. Among the activities of the Institute, knitting was also practiced, and the hair of the goats in the Institute was utilised. It was also recorded that veterinarians from the city centre checked and treated the animals in the Institute (Anonim 1945).

Arifiye Village Institute

The main activity of Arifiye Village Institute, where cattle breeding, sheep and goat breeding, and beekeeping were practiced, was the fishing activities in the nearby Sapanca Lake (Savaş 2021). When the investigations conducted on Sapanca Lake, which had been used for swimming courses and lifeguard training during the establishment years of the Institute, with the suggestion of İsmail Hakkı Tonguç, and the initiative of the Institute Director S. Edip Balkır yielded positive results, fishing activities began at full speed in August 1941 (Balkır 1974; Savaş 2021). For this purpose, İsmail Özkul, a Ministry staff member who specialised in fisheries and had previously been sent to Beşikdüzü Village Institute, was assigned to Arifiye and gave lectures to teachers and students on the subject. In this way, students were allowed to learn fishing with technical and scientific knowledge (Aça 2019). Fish species in the lake were reported as carp, catfish, pike, blackfish, roach, rudd, shad, trout, lake mackerel, perch, bream, rockfish, eel, and crayfish (İzmirligil 1947).

Balkır’s report to the ministry dated 2 September 1941, records 938 kg of fish caught; the report dated 11 October 1941, records 3000 kg, and the report dated about a year later records 12 Mg of fish caught. There was a need for a closed structure to be built to store fish after fishing activities, for students to rest after the hunt, and to shelter in the rain. On this, the fish-house building on the edge of Sapanca Lake (Fig. 6), which had a salting capacity of 20 Mg of fish, was put into operation in May 1942. Thus, some fish caught were used for student food, some were sold in Adapazarı and Sapanca, and the rest were salted in the fish house and sent to other institutes (Kirby 1962; Balkır 1974; TMMOB Ziraat Mühendisleri Odası İzmir Şubesi 1995).

The fish house of Arifiye Village Institute (original photograph from Karabey Aydoğan archive, digital photograph taken from Savaş 2021, photographer unknown, dated between 1942 and 1954).

The students of the Institute, who specialised in fisheries, started to work on marine fisheries in the İzmit Gulf in the following periods (Balkır 1974). In addition, the local people, inspired by the fishing activities of the Institute, have provided themselves with a new source of livelihood (Kirby 1962).

In addition to fishing, animal husbandry activities were performed on the Institute land. For this purpose, because there was not enough land during the establishment years of the Institute, a 3,000,000 m2 land area was purchased across Sapanca Lake for poultry farming, sericulture, viticulture, grain and animal feed agriculture, and a farm was established here (Balkır 1974; Türkoğlu 1997). It was reported that the Institute had 12 cattle and 30 poultry in 1940, 38 cattle and 80 poultry in 1941, and 11 cattle and 190 poultry in 1942 (Balkır 1944). In addition, it was understood that the Institute also took initiatives related to beekeeping activities. Ms Sıdıka, who used to be a beekeeper in Bulgaria, was assigned as a master instructor to provide advanced beekeeping knowledge to the students of the Institute, and the beehives she brought from Bulgaria were purchased and used at the Institute (Balkır 1974).

Beşikdüzü Village Institute

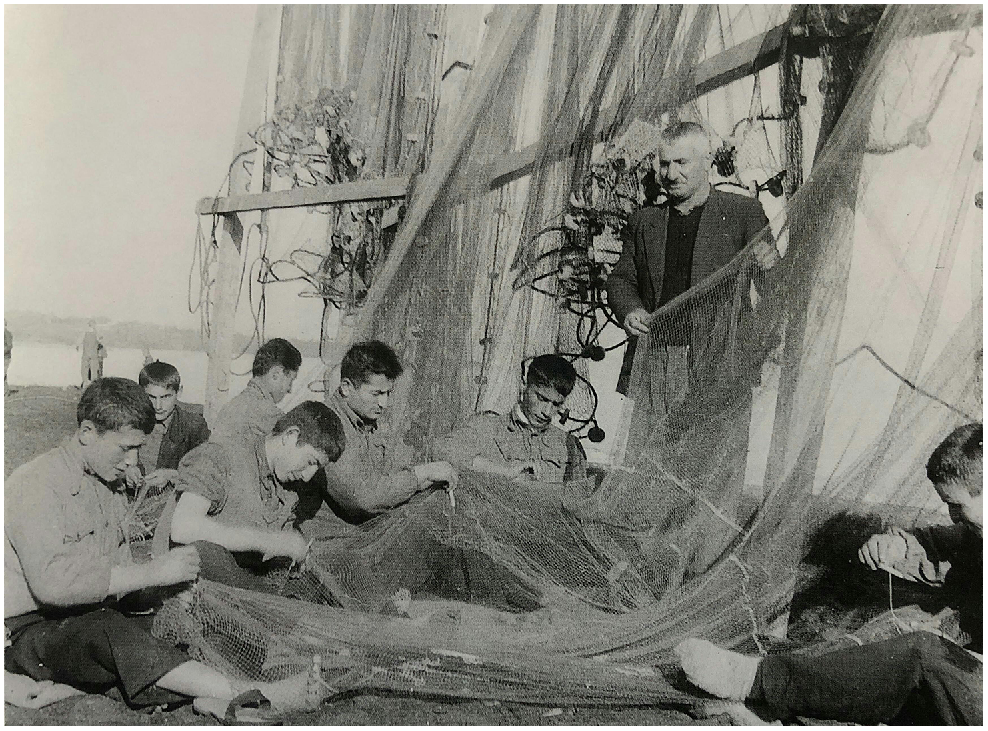

The ‘fisheries and aquaculture’ courses and activities in the curriculum were very well implemented at Beşikdüzü Village Institute. Under Tonguç’s guidance, Hürrem Arman, the Director of the Beşikdüzü Village Institute, began preliminary studies on the subject, initially involving volunteer teachers and students and conducting research on technical and economic problems related to fishing. İsmail Özkul, a fisheries specialist from the Ministry of Agriculture, was sent to the Institute, and books on the subject were brought to the Institute (Türkoğlu 1997). After these pioneering attempts at fisheries education, a professional master instructor was needed to improve efficiency. For this purpose, Fehmi Reis (Fehmi Savaşer), a family member who had been fishing for generations, was contracted, and applied fishing-training was started with the purchase of the first fishing boat (Aça 2019) (Fig. 7). The students of the Institute who were fishing went on fishing expeditions lasting 2–3 months, taking their books and instruments with them. When they returned, they tried to catch up on the subjects they missed by attending cultural classes (Karadeniz 2019).

Fehmi Reis, the master instructor of Beşikdüzü Village Institute, repairs seine nets with students (photograph from İsmail Hakkı Tonguç Archives Foundation, photographer unknown, dated between 1940 and 1954; Aça 2019).

It was recorded that fishing was performed within the Institute from Hopa to Samsun. The amount of fish obtained in 1943 alone reached 45 Mg (Arman 1944). In the following years, other boats and engines were purchased to strengthen the fishing fleet. By 1945, the Institute had the largest fishing fleet in the Black Sea, with two motor boats, one motorised transport boat, 18 boats, two anchovy seines, one bonito seine, three beach seines, three small seines (barabat), three small-fish seines (molozma) and 30 turbot seines (Aça 2019). After a short time, when the Institute produced more fish than needed, a fish house was established, and salting and pickling were started. Thus, surplus fish were sent to other institutes. In addition, fish was sold to the region’s people at affordable prices (Türkoğlu 1997). A revolving fund was established to collect revenues from these sales and other branches. In this way, the first activities to encourage fisheries cooperatives within the scope of regional fisheries were also realised (Aça 2019). According to the recorded information, 500 Mg of anchovy, 60,000 pairs of bonito, and 45 Mg of other fish products were obtained in 1945 (Karadeniz 2019).

It can be said that the realisation of fishing activities at the Institute offered a new occupational field to the local people. As a matter of fact, until this period, as a result of transportation and cost problems in the high settlements of the eastern Black Sea region, transhumance was generally practiced in animal husbandry, and limited fishing was reported to cause significant disabilities because of the bombing method. Institute Director Hürrem Arman, and his fisheries team, prepared a ‘Report on the Outlines of the Fisheries Work’. They put forward quite comprehensive findings and suggestions for the fisheries of the region. In the report, the positive effects of the fish industry to be established in Beşikdüzü were stated as follows: (1) the fish caught that cannot be consumed locally and sold in the markets will not be wasted; (2) the salting and canning of the famous shad fish of the Harşıt and Melet rivers in this region and the caviar production of sturgeon (black caviar) will be developed; and (3) the poor people of this region will take pride in working the country’s resources alongside the Institute and serving as its assistants (Aça 2019).

At Beşikdüzü Village Institute, it was reported that sericulture and beekeeping were also practiced in addition to fishing activities (Karadeniz 2019).

Cılavuz Village Institute

The fact that the north-eastern Anatolia Region has large and fertile pastures for grazing animals has led to animal husbandry being one of the prominent activities at Cılavuz Village Institute. It was reported that approximately 1000 animals were bred in the Institute (Türkoğlu 1997; Boy 2016). The Institute, which started education with limited opportunities initially, has improved physical conditions and increased the number of students in the following years (Arslan 2012; Boy 2016). It is accepted that this development was made possible by the diligent work of teachers and students, and the guidance of the Director of the Institute, Halit Ağanoğlu, who knew the region’s conditions well (Boy 2016).

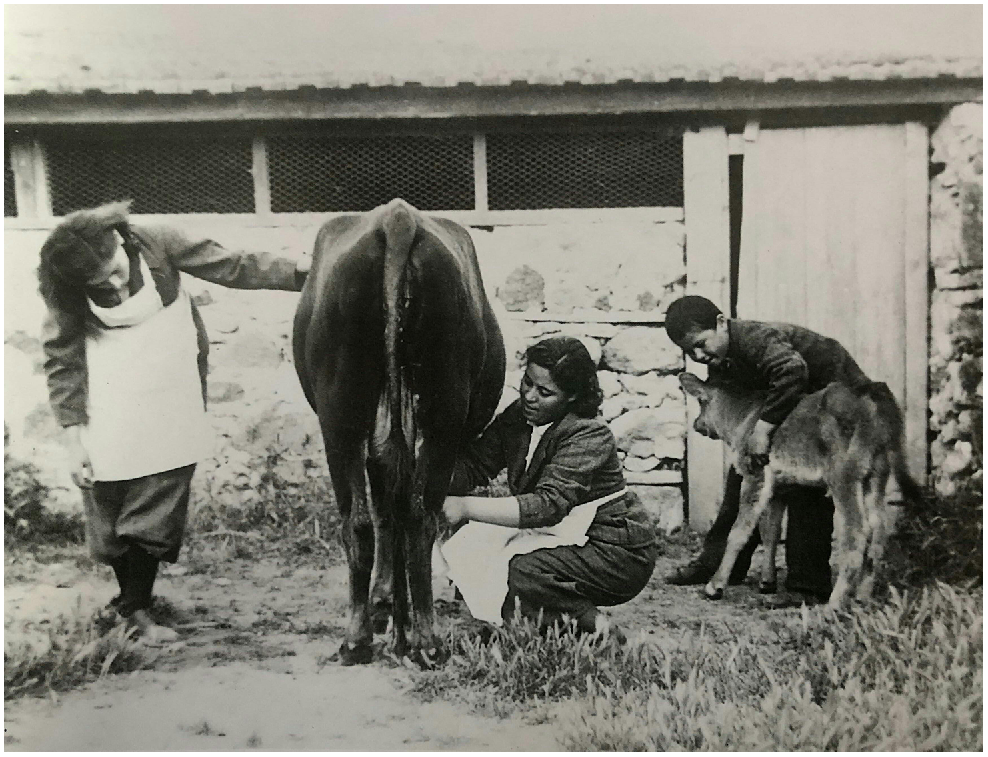

The number of animals used by the Institute for practical training has increased over the years. In the year of its foundation, 15 cows and one bull were purchased, and the number of cows was increased to 24 1 year later, with the calves obtained from these animals, and 44 cows and calves and 11 calves were produced from these animals in 1944. In 1944, to set an example for other institutes, it was announced that 15 calves were obtained from 40 cows and 16 lambs from 60 sheep (Ağanoğlu 1944; Gümüşoğlu 2017). In addition, it was ensured that the animals needed in the village schools where the graduates of Kars Cılavuz Village Institute worked were met, and in cases where the need could not be met through breeding activities, these animals were purchased from external sources (Türkoğlu 1997; Keser 2013). It was reported that 420 cows and 250 oxen were purchased for this purpose in 1945 (Directorate of State Archives 1945; Keser 2013) (Fig. 8).

In a village institute, students are milking cow (photograph from İsmail Hakkı Tonguç Archives Foundation, photographer and location unknown, dated between 1940 and 1954).

In addition to training teachers to conduct animal husbandry with scientific knowledge, the Institute also aimed to set an example for the villagers. To achieve this goal, support was received from district veterinarians according to the agreement between the Ministries, and master instructors were employed on the subject (Türkoğlu 1997; Aktaş 2006). Berktaş (2019) stated that practices related to animal health in this period were performed with traditional beliefs around Kars, resulting in yield loss and animal deaths. In this regard, it was recorded that animal health and care information was handled from a scientific point of view at the Institute, curricula were organised, and successful results were obtained, especially on sheep pox in sheep and digestive diseases in calves. These practices, which stopped animal deaths in the Institute, were reflected in the surrounding villages in time and helped protect animal health in the region (Berktaş 2019).

It was reported that the Institute had high-yielding geese, chickens, sheep, and cows and that the animals in Cılavuz were not only seen as production tools, but all kinds of care and feeding were performed with love and care. All students took animal husbandry courses at the Institute, and female students were specially assigned to produce animal-based foodstuffs. These students were taught milking, cheese, butter, and yogurt making in the dairy within the Institute, and these products and the eggs obtained from poultry met the needs of the Institute (Gümüşoğlu 2017).

The Institute also gave importance to beekeeping activities. Araslı stated that although the region was suitable for beekeeping before the Institute, insufficient honey was produced. With the establishment of the Institute, this gap has been gradually filled over time, and beekeeping activities, which began with two hives in 1940, have reached hundreds of hives over the years. Under the supervision of Zakir Güven, the head of agriculture specialised in beekeeping, students learned about beekeeping in theoretical courses and produced honey in hives in practice. Excess honey production was sent to other institutes (TMMOB Ziraat Mühendisleri Odası İzmir Şubesi 1995; Gümüşoğlu 2017).

Hasanoğlan Village Institute and Higher Village Institute

Hasanoğlan Village in Ankara and its surroundings were suitable for raising sheep and goats (Engin 1944). In the report prepared by the survey team to determine the locations for the establishment of village institutes, it was stated that a village institute could be opened in Hasanoğlan Village, considering the agricultural characteristics of the village, its pastures, and plateaux for animal care and breeding, and the proximity of the sample corral established by the Turkish Mohair Society near the Lalahan Train Station (Dönmez 1945; Gökdemir 2019). This situation caused the animal husbandry activities performed within the Institute to start with small ruminant breeding. Significant attempts were made in the production of mohair yarn by conducting improvement studies in the sample farm of the Turkish Mohair Society, which operated under the supervision of veterinarians during this period, and it was ensured that mohair goat breeding was undertaken with scientific methods (Menteş Gürler 2006).

Hasanoğlan Village Institute has included animal husbandry since the second year of its establishment (Dönmez 1945). The 145 lambs born at the Institute were raised with good care and feeding and joined the sheep flock without any loss. The fact that the lambs raised at the Institute were larger and more developed than were the lambs of the villagers, owing to the difference in care attracted attention quickly (Engin 1944). In the second year of the Institute, 275 sheep, 120 chickens and roosters, five horses, four oxen, six cows, six calves, two donkeys, and one goat were obtained through animal husbandry activities. From animal products, 150 kg of yogurt, 450 kg of cow milk, 435 kg of sheep milk, and plenty of eggs were obtained (Güneri 2004). According to the information provided by Dönmez (1945), one of the students of Hasanoğlan Higher Village Institute, in the January 1945 issue of the Journal of Village Institutes (Köy Enstitüleri Dergisi), the number of animals available at the Institute was as follows: four cows, seven calves, three calves, four oxen, eight horses, 134 sheep, 128 sheep, 99 goats, five donkeys, 68 lambs, 24 kids, 113 chickens, 28 roosters, three ducks, and 18 hives of bees.

In addition to sheep and goat breeding, beekeeping was also one of the leading animal activities in Hasanoğlan Village Institute (Şimşek and Mercanoğlu 2018). In addition, Hasanoğlan Village Institute was an institution that has played a significant role in developing and expanding the beekeeping sector in Ankara (Aysal 2017).

However, as the number of village institutes increased, it became difficult to find teachers to teach at the institutes. To solve this problem, the Hasanoğlan Higher Village Institute was established in 1943 within the Hasanoğlan Village Institute campus. Operating until 1947, this institution provided teacher candidates with higher education in various fields for 3 years (Dönmez 1945; Toprak 2008; Akandere 2019; Özkan 2021).

Unlike other village institutes, Hasanoğlan Higher Village Institute was established to train teachers for institutes rather than teachers for villages, and students were divided into eight different branches according to their abilities. These branches were fine arts (for girls and boys), construction (for boys), mining (for boys), animal care (for boys), poultry farming (for girls), field and garden agriculture (for boys), village home and handicrafts (for girls) and agricultural business economics (for girls and boys). Each student could choose the branch they wanted in line with their skills and switch to another branch if desired. Among these branches, the animal-care branch offered courses in zootechnics, biology, heredity and health knowledge, animal feed knowledge, meadow and pasture knowledge, and the poultry branch offered courses such as poultry care and nutrient chemistry (Gökdemir 2019). The lecturer’s support for these courses was provided by the Higher Agricultural Institute in Ankara (Dönmez 1945). Veterinary zootechnician Professor Dr Selahattin Batu and zootechnician OrdinariusA Professor Dr Hüseyin Kadri Bilgemre were assigned to teach animal breeding, care and nutrition, whereas veterinary internist Professor Dr Selahattin Nejat Yalkı was assigned to teach animal diseases and health knowledge (Dönmez 1945; Türkoğlu 1997; Gökdemir 2019).

It was reported that Hasanoğlan Higher Village Institute had many indoor and outdoor production areas besides education. These production spaces also contributed to developing a form of social organisation such as cooperatives; students who took part in the management of cooperatives such as poultry farming and beekeeping established within the school also learned about cooperatives (Şimşek et al. 2023).

Closure of village institutes

Negative opinions about the village institutes became more tangible and accusatory after a while. These negative criticisms, which arose for different reasons, can be listed as follows: the belief that enrolling only village children in the institutes would create a peasant–urban divide, that students taking part in school affairs resembled a communist regime, and moral concerns due to the co-education of girls and boys as boarders. In addition, the fact that teachers who graduated from these institutions were highly respected in the villages they went to and that villagers consulted teachers in all their affairs was not tolerated by some landlords, who reacted by putting pressure on politicians (Esen 2013).

With the end of the Second World War, the political change that began in many countries also affected Türkiye. Following the first multi-party elections, Hasan Ali Yücel was forced to resign, and İsmail Hakkı Tonguç was dismissed from his position. It was reported that the purpose of these developments was to wear down the village institutes. Then, with the program change made in 1947, the institutes were gradually transformed into classical teacher-training schools and started to move away from the on-the-job education approach. In 1954, the Democrat Party came to government, and with Law No. 6234, village institutes and primary teacher schools were merged, and village institutes were officially closed down (Kalyoncuoğlu 2010; Kapluhan 2012).

Conclusions

Following the establishment of the Republic of Türkiye, village institutes were established to educate the rural society and, not limiting this education to literacy but providing a multifaceted education by the requirements of rural life. Animal husbandry and animal production activities were widely practiced in these institutions.

Animal husbandry, which constitutes both the source of food and the villagers’ economy, was supported through village institutes (Berktaş 2019). The then Minister of Education Hasan Âli Yücel stated that the total number of animals in the village institutes was 9000 in 1944 (Yücel 1944). The fact that this was achieved in a short period of 4 years shows how much importance was attached to animal husbandry activities in the village institutes. Students received theoretical and practical training in animal husbandry at the village institutes. After graduation, they transferred these gains to the people in the villages where they worked and helped improve the animal husbandry activities of the villages.

As a result, the village institutes have had an essential position in the history of Türkiye as a different educational institution that provided social and economic developments in rural areas with practices that had not been undertaken before, offered village children and adults the opportunity to study together, made a political impact in its period and is still frequently mentioned today.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable as no new data were generated or analysed during this study.

Author contributions

Sefa Yıldırım: ideation, literature search, data collection, data processing, writing. Berfin Melikoğlu Gölcü: design and editing, literature review, data collection, data processing, writing.

References

Akandere O (2019) Türkiye’de Uygulamalı Tarım Eğitimine Bir Model: Köy Enstitülerinde Okutulan Ziraat Dersleri ve Uygulamaları. In ‘Türkiye’de Tarım Politikaları ve Ülke Ekonomisine Katkıları Uluslararası Sempozyumu (12-14 Nisan 2018-Şanlıurfa) Bildirileri Kitabı’. (Eds A Güvenç Saygın, M Saygın) pp. 409–432. (Atatürk Araştırma Merkezi Yayınları: Ankara, Türkiye)

Altunya N (2014) Köy Enstitüleri Sisteminde Yönetim. MSGSÜ Sosyal Bilimler 10, 28-49.

| Google Scholar |

Anonim (1945) Antalya – Aksu Köy Enstitüsü Haberleri. Köy Enstitüleri Dergisi 1(1), 169.

| Google Scholar |

Anonim (1946a) Çifteler Köy Enstitüsü Haberleri. Köy Enstitüleri Dergisi 1(4), 619-621.

| Google Scholar |

Anonim (1946c) Ladik-Akpınar Köy Enstitüsü Haberleri. Köy Enstitüleri Dergisi 1(5–6), 190-191.

| Google Scholar |

Anonim (1946d) Savaştepe Köy Enstitüsü. Köy Enstitüleri Dergisi 1(5–6), 186-188.

| Google Scholar |

Arslan N (2012) Türk Eğitim Sisteminde Köy Enstitülerine Bir Örnek: Kars Cılavuz Köy Enstitüsü. History Studies 4, 1.

| Google Scholar |

Aysal N (2005) Anadolu da Aydınlanma Hareketinin Doğuşu: Köy Enstitüleri. Atatürk Yolu Dergisi 9, 267-282.

| Google Scholar |

Aysal N (2017) Türkiye’nin Sosyal Tarihinden Bir Yaprak: XX. Yüzyılda Ankara’da Arıcılık. In ‘Türkiye Cumhuriyeti’nin Ekonomik ve Sosyal Tarihi Uluslararası Sempozyumu: Bildiriler; 26-28 Kasım 2015 Cilt II’. (Ed. E Ünlen) pp. 983–1027. (Atatürk Kültür, Dil ve Tarih Yüksek Kurumu Atatürk Araştırma Merkezi Yayınları: Ankara, Türkiye)

Cengiz M (1946) Hayvanlarımız. Akçadağ Köy Enstitüsü 1(7), 281-282.

| Google Scholar |

Çetin S, Kahya A (2017) Kırda bir modernleşme projesi olarak köy enstitüleri: Aksu ve Gönen örnekleri üzerinden yeni bir anlamlandırma denemesi. METU Journal of the Faculty of Architecture 34, 133-162.

| Google Scholar |

Dönmez R (1945) Hasanoğlan Köy Enstitüsünün Kısa Tarihçesi. Köy Enstitüleri Dergisi 1(1), 1-177.

| Google Scholar |

Erk N (1961) Ankara Yüksek Ziraat Enstitüsünün Kuruluşu ve Veteriner Hekimlik Öğretiminin Bu Kurumdaki On Beş Yıllık Tarihi. Ankara Üniversitesi Veteriner Fakültesi Dergisi 8, 76-104.

| Google Scholar |

Esen S, Akandere O (2021) Köy Enstitülerinde Kız Öğrenciler (Alınma Süreçleri, Eğitimleri ve Meslek Hayatları). Çağdaş Türkiye Tarihi Araştırmaları Dergisi 21, 807-847.

| Google Scholar |

Eser G (2012) Kastamonu-Göl Eğitmen Kursu’nun 1940 Yılı Faaliyetleri. Yakın Dönem Türkiye Araştırmaları 11, 91-117.

| Google Scholar |

Güvercin CH, Aksu M, Arda B (2004) Köy Enstitüleri ve Sağlık Eğitimi. Ankara Üniversitesi Tıp Fakültesi Mecmuası 57(2), 97-103.

| Google Scholar |

İzmirligil E (1947) Sapanca Gölünün Balık Türleri. Köy Enstitüleri Dergisi 1(7–8), pp 203-204.

| Google Scholar |

Kalyoncuoğlu Z (2010) Köy Enstitüleri’nde Hasan Ali Yücel’in Yeri. folklor/edebiyat 16, 237-244.

| Google Scholar |

Kapluhan E (2012) Atatürk Dönemi Eğitim Seferberliği ve Köy Enstitüleri. Marmara Coğrafya Dergisi 26, 172-194.

| Google Scholar |

Kartal S (2008) Toplum kalkınmasında farklı bir eğitim kurumu: Köy Enstitüleri. Mersin Üniversitesi Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi 4, 23-36.

| Google Scholar |

Kızıltepe A, Melikoğlu B “ORDINARIUS PROFESSORS” IN TURKISH VETERINARY MEDICAL EDUCATION. Proceedings of Proceedings of the XXXVII International Congress of the World Association for the History of Veterinary Medicine & XII Spanish National Congress on the Veterinary History: September 21–24, 2006, León (Spain), 2006. pp. 347–352. (MIC)

Kınacı A (2016) KÖY ENSTİTÜLERİ 17 NİSAN 1940-27 OCAK 1954. Köy Enstitüleri 51, 4-5.

| Google Scholar |

Maden F (2009) Kepirtepe Köy Enstitüsü (1937-1954). Atatürk Araştırma Merkezi Dergisi 25, 495-522.

| Google Scholar |

Menteş Gürler A (2006) Türkiye Tiftik Cemiyetinin Tarihçesi. Lalahan Hayvancılık Araştırma Enstitüsü Dergisi 46, 39-46.

| Google Scholar |

Özkan İ (2016) Türk Eğitiminde Öğretmen Okulları ve Öğretmen Yeterliliklerine Dair Düşünceler. 21. Yüzyılda Eğitim Ve Toplum Eğitim Bilimleri Ve Sosyal Araştırmalar Dergisi 5, 1-28.

| Google Scholar |

Payaslı V (2015) Belleklerde Bir Çınar: Düziçi Köy Enstitüsü. Tarih Okulu Dergisi 8, 319-356.

| Google Scholar |

Sarı M, Uz E (2017) Cumhuriyet Döneminde Köy Eğitmen Kursları. Turkish History Education Journal 6, 29-55.

| Google Scholar |

Şeren M (2008) Köye öğretmen yetiştirme yönüyle Köy Enstitüleri. Gazi Üniversitesi Gazi Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi 28, 203-226.

| Google Scholar |

Şimşek G, Mercanoğlu C (2018) Bir ‘Planlama Örneği’ Olarak Köy Enstitüleri Deneyimi. Planlama 28, 261-281.

| Google Scholar |

Şimşek G, Mercanoğlu C, Küçükoğlu H (2023) Hasanoğlan Yüksek Köy Enstitüsü’nün Kuruluşundan Günümüze Yerleşke Bazında Mekânsal Analizi. Planlama 33(2), 266-287.

| Google Scholar |

Tınal M (2008) Kızılçullu Köy Enstitüsü: Kuruluşundan İlk Mezunlarına. Muğla Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi 21, 181-198.

| Google Scholar |

Tınal M, Bozdağ H (2017) Köy Enstitüleri Tarihinden Bir Kesit: Kızılçullu Köy Enstitüsü Tarihçesi. Turkish Studies 12, 179-202.

| Google Scholar |

Yiğit A, Menteş Gürler A (2016) Stock Raising Education in Turkey from Village Institutes Till Date. The Anthropologist 23, 606-611.

| Google Scholar |

Footnotes

A Ordinarius Professor: Academic title representing the highest authority. It was given in Türkiye between 1933 and 1960 (Kızıltepe and Melikoğlu 2006).