Oil and gas—winners and losers of the credit crunch

Kevin SmoutKPMG 152-158 St Georges Terrace Perth WA 6000

The APPEA Journal 49(2) 584-584 https://doi.org/10.1071/AJ08057

Published: 2009

Abstract

Since mid 2007, we have seen one of the biggest crises ever to hit the financial markets—the so-called credit crisis. Initially banks bore the brunt of the credit crisis, but the ramifications were far deeper, affecting consumer households as well as debt and equity reliant organisations. This presentation will discuss the specific impacts of the crisis for the oil and gas industry, including: the fact that it is not just a credit crunch, but also an equity crunch; the fact that the issues in raising debt capital—the cost is now well beyond the global earnings yield; the fact that investors are now seeking alternate, less risky and less complicated investment options; and the fact that investment funds are shifting from private equity funds to oil-financed sovereign wealth funds.

The crisis has had varying impacts on the oil and gas industry. Organisations reliant on debt and equity funding and those operating in new or start-up ventures are under increased pressure and scrutiny. On the other hand, well positioned oil and gas organisations can take advantage of current and emerging opportunities, particularly in relation to alternate energy sources.

In the future, financial prosperity will be with organisations that operate in countries with guaranteed supplies of oil and gas (e.g. Australia, Brazil, Russia, India and China).

A future focus for the oil and gas industry will be for organisations to maintain very disciplined and robust financial-risk management systems in order to manage their liquidity and financial risks in this changed environment.

keywords: Back to basics, credit crunch, high gearing, liquidity shortage, investment, cash is king, hedging, cash flow forecast

Introduction

During July and August of 2007 we saw the start of arguably the biggest crisis ever to hit the financial markets since the Great Depression. The so-called credit crunch began primarily after many years of incredible growth in the US, where individuals—regardless of their financial capabilities—were able to and encouraged by government policy to take up debt to finance homes or investments.

At the same time, there was a global power shift with the economies of China and India emerging and Middle Eastern countries benefiting from higher oil prices.

The flow on impact of the decline in US property prices was the collapse and inability and unwillingness of banks to lend to each other. The result was the beginning of the de-leveraging of our financial markets resulting in a scarcity of funds which has significantly driven up the cost of borrowing and limited the availability of equity as stock markets around the world have plummetted.

The speed with which change has happened in Australia has been astounding. In an extremely short space of time we have gone from a long-term positive outlook for most industries, including oil and gas, to a position where the World Bank recently announced that it predicts the global economy will contract during 2009 and has talked of a ‘great recession’.

After looking at the factors that impact the financial environment for those in the oil and gas sector, this extended abstract presents at the key issues that have and will continue to determine the winners and losers of the credit crunch and it is not complicated—quite simply you need to focus on the basics.

Credit and Equity

The winners and losers of the credit crunch have been determined by the old adage that cash is king. When looking at a sample of listed oil and gas players two years ago compared to today, it is clear that the higher the level of gearing in 2008 the higher the penalty applied by the market when assessing the company (Table 1).

The same fate applies to those that have not had a longer-term capital management plan and have found themselves in the present environment with a liquidity problem and unable to obtain further debt or equity.

The credit facilities for oil and gas companies are usually structured around the value of the entity’s oil and gas reserves. This value is based on forecasts that the lender applies to the company’s reserves. If the commodity price drops or exchange rates strengthen when the facility is due for review, the estimated value attached to the reserves decreases and its line of credit will be tightened.

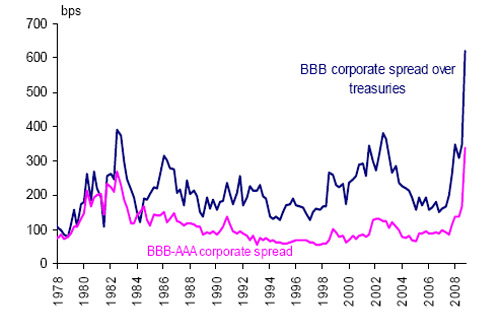

Lending institutions are also increasing margins to reflect increased risk of default, and lending requirements have become significantly more stringent despite the decrease in the Reserve Bank of Australia’s (RBA) cash rates. Even where good projects can attract the finance, it is at a high cost of debt as can be seen from the change in corporate spreads reflected below in Figure 1, which shows the increase above the cash rates that corporates, of different credit ratings can borrow.

|

The implications of the credit crunch and decline in equity prices mean it is very difficult for companies to raise debt or capital. Potential investor concerns about declining market capitalisations, a global recession together with a lack of liquidity caused by credit crunch have all but stemmed the ability of public and private companies to raise capital.

On a positive note there are always exceptions and some companies are very good counter-cyclical investors and will invest in new capital projects even in a severe downturn. Exxon purchased Mobil in 1998 during a downturn and it turned out to be a very astute investment. We have also recently seen Shell announce an increase in its planned capital expenditure this year. These companies are able to do so because they have built up cash reserves while oil prices were at record highs.

In addition, fund managers moved investments into the oil and gas sector. The expectations of some fund managers ranked the oil and gas industry in second place (16%) behind blue chips (30%) to perform the best in 2009.1

Government

In today’s world, governments are desperately trying to stem the contraction in national economies and to restore confidence in financial markets. Their aim is to improve interbank lending and the provision of credit to the corporate world. An extensive armoury has been used by the Australian Government to achieve this outcome, for example:

a substantial increase in infrastructure spending to minimise the increasing unemployment rate as the economy slows;

monetary policy where the RBA has reduced the official interest rate significantly;

fiscal (economic) policy with actions from tax bonuses and first home-owners grants to rebates for a fridge replacement scheme;

interbank credit stimulus such as government repurchase agreements; and,

the controversial guaranteeing of bank held deposits.

There are other ways in which governments can stimulate new investment even in a severe financial downturn such as through the administration of their oil and gas tenements. In Australia, there are a large number of retention leases requiring renewal or extension in the short-term, with Government giving a clear message that it wants these resources developed.

In considering government’s role in economic management, reference also needs to be made to the increasingly important role being played by sovereign wealth funds (SWF). These state owned entities have grown significantly over the past decade with an estimated assets holding of over $3 trillion in 2008 with a large portion invested in the oil and gas sector.

SWF’s who make strategic purchases at the bottom of the market will be the winners providing they can operate efficiently. Australia’s major SWF, the Future Fund has assets of approximately $60 billion dollars held in, or ready for, investment. Where fund managers choose to direct these funds in the future is yet to be seen.

Oil and Gas Sector

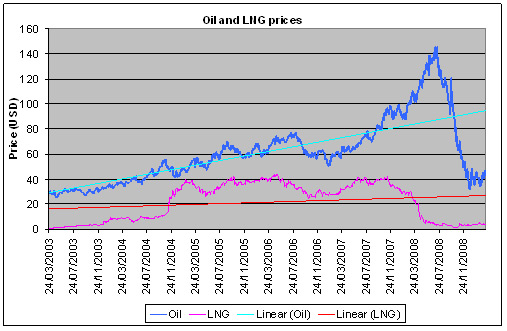

Although the global economic downturn is likely to lead to a further slow down in oil and gas activity in the next 12 months, the longer-term fundamentals for the oil and gas sector remain positive. Most economists and other pundits are forecasting that demand for oil and gas will remain at a high level for the foreseeable future. The following graph (Fig. 2) reflects the past five years volatility in oil and LNG prices. This volatility is something which we will most certainly see on an ongoing basis.

|

Of real interest to in the oil and gas sector is the extent to which funds have moved away from the financial markets sector to the oil and gas sector in the final three quarters of 2008. There is still strong backing for most parts of this sector as an area to invest in.

With cash being the single most important differentiator in this market, some smaller players with cash are buying into larger players that are looking for working capital. There is a reasonable amount of consolidation in the up-stream sector including the coal seam gas sector.

Winners and Losers

Regardless of whether or not we have seen the bottom of the cycle, we are all operating in a tough environment and even from the most bullish commentators it appears we have at least 12 months before we are likely to see any real up turn.

As an accountant, in my view, it is back to basics in these challenging times. The winners are those who have not lost sight of the basics and the losers, those who have. The era of high commodity prices has covered up many management sins and the tide has now gone out and these companies have been exposed.

In this environment, it is critical for management to be providing a simple monitoring system from the Board level down that reports against the basics of business and recognises that cash is king. Little harm will come from questioning whether you really have processes in place to address the following issues:

understand that sufficient cash flow should be a key consideration at the heart of all strategic decisions and is a whole-of-business issue. Each business process or independent operation has the effect of increasing business complexity and the potential for tying up cash. Each business area should understand and be accountable to the extent of the impact it has on cash. Basics such as discretionary operating expenditure, debtor days and managing capital expenditure are essential areas to monitor;

cash flow forecasting and subsequent capital management, including loan covenant management, in addition to having long-term open relationships with financiers are also critical;

challenging assumptions and discount rates used in forecasts and understanding the cash impacts of tax are all essential in ensuring cash flow models are robust;

having a close watch on your key suppliers and contractors and understanding the extent to which the current economic environment is impacting them and their ability to service you will be an important differentiator. This should include managing customer and supplier terms;

hedging has been seen, for a while, as a particularly evil pastime—this should not be the case! Hedging by definition means you are reducing your exposure to a particular existing risk and is an important cash management tool; and,

to the extent possible, focus on the medium term. Where cost cutting is necessary make sure you have considered alternatives and the longer-term impacts for when the market turns. To be a winner you need to have retained your key skill base during the difficult times to retain your ability and credibility for the next upturn.

Kevin Smout is a partner in KPMG’s audit and risk advisory practice and is the Western Australian leader of KPMG’s financial services group. He has 14 years experience in professional services and commerce in Australia and South Africa. Kevin is a market leader in treasury, risk, derivates and hedging. He has worked with many of Western Australia’s largest financial services and resources organizations, delivering advice to understand financial risk and quantify derivatives to mitigate these risks. He is a regular presenter at FINSIA and AICD seminars, and also presents on treasury related topics for hedging and risk management forums for resource companies. ksmout@kpmg.com.au |