Prioritising animals for Yirralka Ranger management and research collaborations in the Laynhapuy Indigenous Protected Area, northern Australia

Bridget Campbell A * , Shaina Russell A , Gabrielle Brennan A ,

A * , Shaina Russell A , Gabrielle Brennan A , A

B

C

Abstract

Amidst growing international calls for inclusive conservation and a backdrop of declining species and cultural diversity, Indigenous-led approaches that offer opportunities for biocultural benefits are of growing interest. Species prioritisation is one area that can be decolonised, shifting from quantitative, large-scale threatened species metrics to pluralistic, place-based approaches that include culturally significant species.

This study aimed to establish a list of priority animals of concern to Ŋaḻapaḻmi (senior knowledge holders) in the Laynhapuy Indigenous Protected Area, north-eastern Arnhem Land, Australia. This list could focus the research and management efforts of the Yirralka Rangers and collaborators.

Adhering to local governance structures, through six group-elicitation sessions, Ŋaḻapaḻmi were asked to identify animals of concern and describe reasons for concern. Existing occurrence records and threat status of these species were compiled to assess baseline data and guide next steps.

The Ŋaḻapaḻmi-defined Laynhapuy Priority Animal List contained 30 animals (species/groups), with the highest-ranked animals including Marrtjinyami wäyin (walking animals), Rupu (possums), and Djanda (goannas), all mammals and varanid lizards. The list of 30 animals included 43 species from a Western-science perspective, of which 12 were also listed as threatened through Western conservation frameworks. Some animals were considered high priority locally, such as the waṉ’kurra (northern brown bandicoot, Isoodon macrourus), although not a concern from a Western-science perspective, demonstrating mismatch between local and larger-scale approaches. To help disentangle whether this mismatch is due to cultural significance and/or localised decline not captured at larger-scale assessments, we provide the animal’s publicly known Yolŋu clan connections and reasons for concern alongside existing baseline occurrence data. Recent collaborative surveys have substantially increased data for Laynhapuy Priority Animals, demonstrating the benefits of community engaged wildlife research.

Multidisciplinary research collaborations can produce Indigenous-led ‘working’ lists of priority animals to guide culturally attuned on-ground action. Approaches that draw on different cultural knowledge systems require interrogation of how knowledge is created and conveyed to ensure mutual comprehension and practical use.

Indigenous-led approaches offer possibilities for enhanced management of species by local groups, with anticipated co-benefits to species and cultural knowledge.

Keywords: Arnhem Land, biocultural conservation, cross-cultural ecology, culturally significant species, Indigenous-led conservation, right-way science, species prioritisation, Yolŋu.

Introduction

This research followed the directive of many Yolŋu Yirralka Senior Rangers, including Banul Munyarryun who stated that we need to ‘start to bring the two sciences together, Western science and Yolŋu science, so we can have better understanding. Bring both together, have the full story: what’s there; how many [animals]; if they’re healthy, safe, right; or maybe we’re worried about some, maybe expected to see them there but couldn’t find them, or maybe they’re there.’

Given the global extent of Indigenous-owned and -managed lands and importance for biodiversity conservation (Garnett et al. 2018), broader recognition of Indigenous peoples, practices, knowledge and values is needed to balance the dominance of Western science in conservation decision-making. Recognition of Indigenous peoples’ rights to and customary responsibilities for managing their ancestral estates has contributed to a rise in convergent environmental and cultural, or biocultural, conservation policies at the global scale (e.g. UNDRIP, IPBES, CBD). However, typically, the criteria used to prioritise and monitor conservation outcomes adopt ecological metrics, rather than tangible and intangible cultural values (Austin et al. 2018; Zurba et al. 2019; Ens et al. 2023). In the case of species conservation, culturally significant species (CSS) and places important to Indigenous peoples could be assessed, not just those of importance to Western conservation prioritisation frameworks (Maffi 2001; Garibaldi and Turner 2004; Goolmeer et al. 2022a).

CSS have been defined as ‘species of exceptional significance to a culture or a people, and can be identified by their prevalence in language, cultural practices (e.g. ceremonies), traditions, diet, medicines, material items, and histories of a community’ (Gore-Birch et al. 2020, p. 2). Globally, CSS, especially fauna, are not well documented and are likely to be considered ‘Data Deficient’ by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) (Reyes-García et al. 2023). Indigenous leaders and researchers argue that assessments of CSS should follow a place-based approach, led by Indigenous knowledge holders, following local values and cultural governance structures (Coe and Gaoue 2020; Freitas et al. 2020; Goolmeer et al. 2022a, 2024). Similarly, the biocultural conservation concept emerged in recognition of the convergence of biological and human cultural values that can be simultaneously addressed through inclusive conservation actions, offering a more ethical approach to conservation (Maffi 2001; Sterling et al. 2017). This cultural reframing challenges Western species prioritisation approaches to decolonise and acknowledge cultural governance of wildlife management and Indigenous-led fauna science (Goolmeer and van Leeuwen 2023) and, hence, pluralistic values of species, conservation and management (Howitt and Suchet-Pearson 2006). With regard to conservation decision-making, Law et al. (2018) argued that ‘multiple equity objectives’ from non-Western ontologies are rarely considered. The present paper aims to address these discrepancies by exploring which animals Ŋaḻapaḻmi (senior Indigenous rights and knowledge holders) of the Laynhapuy Indigenous Protected Area (IPA) would prioritise for management and research, and why, and how these correspond with external Western conservation frameworks.

Western science places value on the application of unified terminology as a means of producing knowledge that can be globally shared and understood (e.g. binomial taxonomic ‘scientific’ names). However, Western scientific terminology is not universal. Naming systems can have diverse functions and meanings across cultures. For the Yolŋu Indigenous people of north east Arnhem Land, naming is imbued with relation to Country (Williams 1986; White 2003; Boll 2006). Totemic places, animals and plants have multiple names, and may have ceremonial significance, being sung in manikay (ceremonial song cycles) (Morphy 1991; Toner 2001; Boll 2006). Animals may also be referred to and understood as kin by Indigenous peoples through complex kinship systems that connect the human and more than human world (Boll 2006; Fijn 2014; Goolmeer et al. 2024). Likewise, researchers should not assume that Indigenous observations of Country or changes to Country always correspond with the Western scientific worldview (e.g. understandings of biodiversity decline and climate change) (Petheram et al. 2010). Rather, a range of reasons for observed changes to Country have been recorded by Indigenous peoples, from the impacts of planetary climate change and globalisation to localised spiritual agency (Petheram et al. 2010). Documented strategies of Indigenous people to address contemporary changes often reflect both traditional Indigenous ontology and Western science (see Seton and Bradley 2004; Boll 2006).

Species prioritisation in biodiversity conservation

The prioritisation of species is considered a central pillar of modern conservation decision-making (Game et al. 2013) and was introduced to maximise the ecological benefits of conservation actions, given limited project funding and timelines (Wilson et al. 2009). In typical Western conservation approaches, species prioritisation has largely been based on species most at risk from extinction. Globally accepted metrics of extinction risk are found in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (Rodrigues et al. 2006; Keith et al. 2015). A species conservation status is typically determined by Western scientific criteria, including the known distribution, reduction in population size and distribution, and sensitivity to threats (Rodrigues et al. 2006; Threatened Species Scientific Committee 2015). Evidence for these criteria depends on available data, site access and expert scientific opinion (Rodrigues et al. 2006). There have been calls to integrate Indigenous knowledge into the IUCN Red List (Wong 2016; Cross et al. 2017) because Indigenous knowledge has been shown to expand species knowledge and inform recovery strategies, especially when quantitative data are limited (Wong 2016). For example, in collaboration with local Indigenous knowledge holders, Russell et al. (2023) increased the distribution and abundance data for freshwater turtle species of the South East Arnhem Land IPA in Australia’s national biodiversity database, the Atlas of Living Australia, from 12 to 753 records. Knowledge on threats, habitat and cultural values were also recorded. Without such data, this region may be considered data deficient, impeding potential Western management decisions.

Progress towards CSS prioritisation in Australia

Despite being considered a ‘megadiverse’ continent, Australia holds one of the worst extinction records globally (McDonald et al. 2015; Ward et al. 2019). Given the extent of Australia’s Indigenous estate (~57% of the land surface) and IPAs (~49% of the National Reserve System), the potential benefits of applying the CSS concept to encourage Indigenous-led fauna management and research are substantial (Goolmeer et al. 2024). Australian conservation efforts are broadly guided by the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act), and conservation funding is often preferentially given to species considered by Western frameworks as endangered or part of certain taxonomic groups (e.g. birds, mammals and amphibians) (Possingham et al. 2002; Watson et al. 2010). Recently, the EPBC Act and state-level threatened species legislation have been scrutinised as being ineffective, limited in the representativeness of threatened biodiversity and unable to halt or prevent further biodiversity declines (Watson et al. 2010; McDonald et al. 2015; Ward et al. 2019).

An independent review of the EPBC Act by Samuel (2021) argued that the Act failed to meet international directives for Indigenous inclusion and leadership in conservation decision-making. However, there is growing recognition of the importance of engaging with Australian Indigenous peoples to co-develop solutions to protect threatened and culturally valued species and places (Baker et al. 1992; Ens et al. 2015; Paltridge and Skroblin 2018; Goolmeer et al. 2022a). At a national level, the federal government recently developed ‘First Nation’ targets within the Threatened Species Action Plan (2022–2023) that prioritises working with the right people to include their ‘knowledges in conservation assessments, processes and planning to guide recovery actions, research and monitoring activities’ (Target 15; DCCEEW 2022). As part of the Threatened Species Action Plan (2022–2023), a list of 110 priority species was determined. This list did include an ‘importance to people’ principle to help prioritise CSS; however, the list was based on species considered important for other factors, such as extinction risk (DCCEEW 2022). We suggest there is greater potential for the co-production of species knowledge and priority setting, especially within the IPA program, where Indigenous rangers are the primary decision-makers and responsible for implementation of such decisions.

In Australia, there are some examples of CSS prioritisation in fauna management and monitoring (Cochrane et al. 2009; Fitzsimons et al. 2012; McKemey et al. 2019; Campbell et al. 2022; Skroblin et al. 2022). In Kakadu National Park, consultations with Bininj/Mungguy peoples were undertaken to develop a threatened species priority list aligned with local priorities (Winderlich and O’Dea 2014). Species were ranked according to the level of concern by Bininj/Mungguy, alongside reasons (e.g. inappropriate fire regime, effects of invasive pest species) and observed changes. In the Western Desert, two-way monitoring of Mankarr (greater bilby, Macrotis lagotis), a threatened and culturally significant species for the Martu people, was co-developed in response to concern around ongoing decline (Skroblin et al. 2022). These examples demonstrate recent concerted efforts to decolonise the prioritisation and monitoring of CSS; however, we acknowledge that such approaches are not widespread and further work is required to empower Indigenous knowledge holders and decision-makers.

Building on emerging CSS discourse in Australia, the present research aimed to better understand the animals that Ŋaḻapaḻmi (Yolŋu knowledge holders) of the Laynhapuy IPA would identify as priority for on-ground management and research collaborations by the Yolŋu Yirralka Rangers. The research was a collaboration between the Yirralka Rangers and university researchers and was conducted in association with the Laynhapuy IPA Ward Mala (homeland leaders) and Yolŋu Ŋaḻapaḻmi. Yolŋu Ŋaḻapaḻmi are senior knowledge holders, among the Wäŋa Waṯaŋu (‘place-holders’ or Traditional Owners; members of a patrilineal clan) and Djuŋgayi (caretakers; children of the women of a clan who have responsibility to care for their mother’s Country). This initiative followed five years of cross-cultural fauna research (2018–2022) by these groups, including 14 collaborative fauna surveys with over 100 participants (Ens, Yirralka Rangers, Kitchener, Campbell and Russell, unpubl. data), and Yolŋu knowledge mapping of six culturally significant species (Campbell 2020; Campbell et al. 2022). Throughout this work, Yolŋu Ŋaḻapaḻmi expressed concerns for culturally important and threatened fauna and questioned what strategies could be applied to support their persistence for future generations.

The research approach included the following:

consultations with Yolŋu Ŋaḻapaḻmi to develop a list of Laynhapuy priority animals for the Laynhapuy IPA;

recording Yolŋu reasons for animal prioritisation; and from (1) and (2)

investigating the similarities and differences between Yolŋu and Western species priority lists, including underlying values and concerns; and

collating existing baseline data for the priority animals to direct future monitoring and management decisions.

The outcomes of this research were intended to inform the Yirralka Rangers’ management efforts and research collaborations across the Laynhapuy IPA. The scope of this project centred around vertebrate terrestrial animals. Future efforts could expand this work to better capture other animals, such as birds, invertebrates, marine animals and plants.

Materials and methods

Study region: Laynhapuy Indigenous Protected Area

Located in north-eastern Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory of Australia, the Laynhapuy IPA is a region of immense local, national and international conservation value (Yirralka Rangers 2017). The IPA provides habitat for 47 species of vertebrate fauna and internationally significant critical habitat for migratory birds (Yirralka Rangers 2017). As part of the Australian monsoonal tropics, the Laynhapuy IPA makes up one of the largest intact savanna systems on Earth (Woinarski et al. 2007), and spans an area internationally recognised as one of the last remaining regions free from large-scale anthropogenic change (Watson 2016). However, factors continue to threaten ecosystem health and biodiversity values, namely the impacts of accelerating sea level rise, and introduced species such as water buffalo (Bubalus bubalis), feral pigs (Sus scofra), feral cats (Felis catus) and cane toads (Rhinella marina) (Yirralka Rangers 2017). Alongside the recognised biodiversity value of this region, north east Arnhem Land is also considered a significant stronghold of Indigenous Australian traditional cultures and languages (Marmion et al. 2014) and a hotspot of Indigenous biocultural knowledge documentation (Ens et al. 2015).

North east Arnhem Land is Aboriginal Land (under the Commonwealth’s Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976) and has been stewarded by the Yolŋu Indigenous peoples since time immemorial. The Yolŋu form a well-defined cultural bloc, differing from surrounding groups both in terms of language and social organisation. The Yolŋu universe is divided into two moieties (halves) named Dhuwa and Yirritja. Not only people but fauna, flora, land and sea Country, and weather phenomena such as winds and clouds have a moiety identity. Rom, often translated as Law, but covering a wider field than the English translation implies, is the foundation of the Yolŋu world. Rom sets out the right way to live and entrusts the land, sea, and everything in them to the care of Yolŋu, who are, through the performance of manikay (song cycles) in ceremony, rirrakay wäŋawu (‘voice of place’). The Yolŋu social universe is organised around gurruṯu (relations between kin). Like moiety, kinship is a universal organising principle. In relation to Country, the most significant people are first the Wäŋa Waṯaŋu (‘place-holders’ or ‘Traditional Owners’). The Country-holding unit is a named group of people, often called a ‘clan’ who trace their descent patrilineally to an apical ancestor several generations back. Also significant are the children of the women of the clan who are known collectively as Djuŋgayi. Yolŋu translate this role as ‘caretaker’ or sometimes ‘manager’; it is their responsibility to assist their mother’s clan to look after their Country well, and the Wäŋa Waṯaŋu will always consult senior Djuŋgayi on matters relating to Country.

In the 1970s, Yolŋu leaders began the ‘Homelands Movement’ that saw many Yolŋu move from mission towns to live on their traditional clan estates. Motivations for this movement were founded in Rom and the responsibilities of Wäŋa Waṯaŋu and Djuŋgayi to look after Country. The Laynhapuy Homelands Association (later the Laynhapuy Homelands Aboriginal Corporation, LHAC) was established in 1982 to support these homeland communities (LHAC 2017). The old people’s vision for the LHAC was ‘To determine our own future, to manage our own affairs, to become self-sufficient so that the homeland mala (clans) can continue to live in peace and harmony’ (LHAC 2017). The Yolŋu leaders gave the LHAC responsibility to implement this vision.

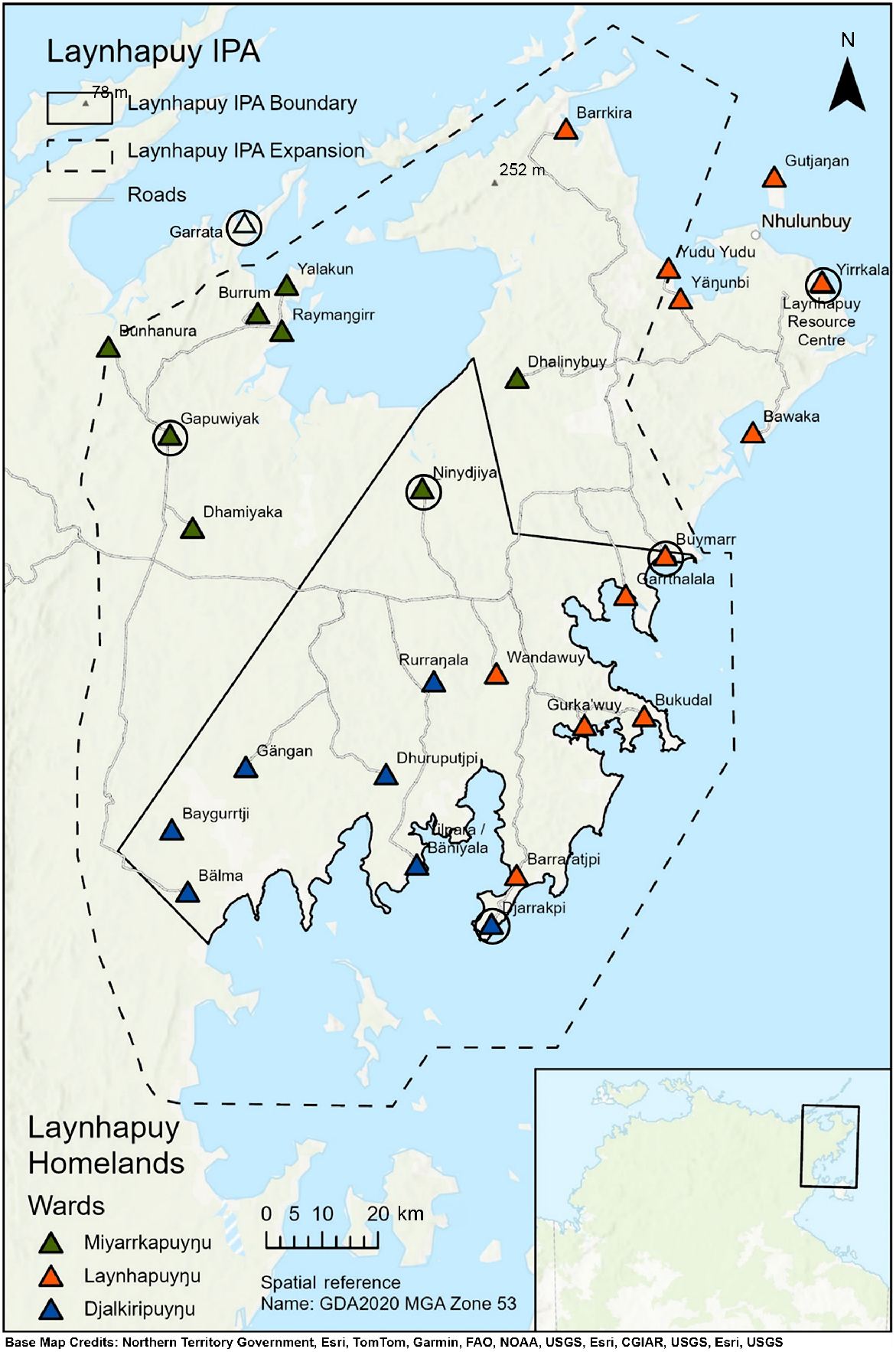

In 2003, the LHAC established the Yirralka Ranger land and sea resource management program in response to Wäŋa Waṯaŋu desire to manage their Country and deal with threats to cultural and environmental values. The Laynhapuy IPA was declared in 2006, with an expansion being imminent, and now covers 14,728 km2 (Fig. 1). Currently, there are Yirralka Rangers working out of 14 of the Laynhapuy homelands.

Laynhapuy IPA governance system

In determining policy and priorities, the Yirralka Rangers recognise a higher responsibility to the Wäŋa Waṯaŋu and Djuŋgayi. A new Yolŋu governance structure was introduced to the IPA in 2021 with the goal of empowering the Yolŋu leadership to make management and operational decisions on Country. The Ward Mala governing body for the Djalkiripuyŋu (Blue Mud Bay), Miyarrkapuyŋu (Arnhem Bay) and Laynhapuyŋu (Gulf Coast) were formed through discussions with over 45 Ŋaḻapaḻmi from across the Laynhapuy homelands (Fig. 1). The LHAC endorses the decisions of the Ward Mala and ensures organisational matters are properly considered. LHAC Board and Ward Mala membership is overlapping. Supporting the LHAC operations, the Yirralka Rangers deliver collaborative governance of the IPA. The Laynhapuy IPA Advisory Committee supports Yirralka’s operations by providing advice and technical support.

The Yirralka Rangers have consulted with Ŋaḻapaḻmi from all the Yolŋu clan groups to develop the next Laynhapuy IPA Plan of Management. The IPA Plan has strong focus on prioritising Yolŋu Rom and Yolŋu ways of caring for their Country. The Rangers also look to co-design partnerships that promote Yolŋu rights and interests, ensuring reciprocity. To support these partnerships, the Yirralka Rangers have produced a ‘research protocol’ to ensure the right people and processes are followed and that Yolŋu are leading with their partners by their side.

Prioritising animals for conservation

Consultations to identify Laynhapuy priority animals were made in accordance with Yolŋu Yirralka Ranger governance and decision-making structures. During initial consultations, university researchers attended Head Ranger and Ward Mala meetings where Ŋaḻapaḻmi nominated priority animals (Table 1, Fig. 2a). Specifically, after discussing the project, Ŋaḻapaḻmi were asked which animals they were worried about and why (Table 2). Any Yolŋu-recognised animal classifications and/or species mentioned during the elicitation sessions were recorded by researchers. During these sessions Ŋaḻapaḻmi were also asked to identify locations where they were interested in looking for these animals, to direct collaborative camera-trapping and fauna survey research.

| Item | Knowledge-elicitation event | Location | Number of Ŋaḻapaḻmi | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Governance meetings | Yirralka Rangers head ranger meeting (April 2022) | Bäniyala | 12 | |

| Laynhapuyŋu Ward Mala meeting (May 2022) | Birany Birany | 11 | ||

| Miyarkapuŋu Ward Mala meeting (June 2022) | Dhälinybuy | 8 | ||

| Survey interviews | Garrata cross-cultural fauna survey (May 2022) | Garrata | 8 | |

| Buymarr cross-cultural fauna survey (June 2022) | Buymarr | 7 | ||

| Djarrakpi cross-cultural fauna survey (October 2022) | Djarrakpi | 6 | ||

| Total | 6 | 52 A |

Recording the Laynhapuy priority animals at (a) the initial Head Ranger meeting (4 April 2022), and during an (b) interview with Gapuwiyak Ŋaḻapaḻmi led by the Yirralka Rangers and university researchers (credit: Emilie Ens).

| Yolŋu Matha | English | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nhäku wäyingu nhe yukurra warwuyundja? Ga nhäku warray? | What animals are you worried about? Why? | |

| 2 | Nhä wäyin important ga nhäku warray? | Which animals are important? Why? | |

| 2a | Nhä wäyin ŋunhiyi manikaymirri, dhäwumirri, ga rommirri? Ga yolku bäpurruwu? | Which of these animals are in stories, songs and ceremony? Which clans? | |

| 2b | Nhä wäyin ḻukanhamirrinydja? | Which of these animals do you eat? |

Translations were made by Nyemburr Munuŋgurr and Yananymul Munuŋgurr, with assistance from Frances Morphy.

Survey interviews

Prior to three on-Country fauna surveys, elicitation sessions were conducted with Ŋaḻapaḻmi from each survey location (Fig. 2b). Ŋaḻapaḻmi were asked to nominate priority animals by discussing which animals they were worried about and why (Table 2). Written prior informed consent was sought for interviews in accordance with Macquarie University Human Research Ethics committee approval (Ref: 5201800178). The Yirralka Rangers nominated Ŋaḻapaḻmi for interviews by peer selection and ensured that local Yolŋu cultural protocols were followed throughout the interview process. Interviews were conducted at the interviewee’s place of residence or on-Country and ran for 35–75 min. Interviews were often led by the Yirralka Rangers, and were conducted in Yolŋu Matha and English, with the Yirralka Rangers translating in situ. The interviews were recorded either by audio or video (depending on permissions), and the researchers compiled a list of animals mentioned during the interviews. For the full methods and interview questions for this project see Campbell, Yirralka Rangers, Morphy and Ens (unpubl. data). At the end of each interview, researchers and rangers transcribed the recorded interviews. The Indigenous knowledge featured in this paper is the property of Yolŋu Ŋaḻapaḻmi who gave written and/or oral prior informed consent for knowledge to be recorded and published.

During interviews, discussion of terminology was necessary to clarify the meaning of certain key concepts. Namely, clarification of ‘animal’ was needed, because the concepts in Yolŋu Matha that most closely translate as ‘animal’ (‘wäyin’ and ‘warrakan’) traditionally refer only to animals that are eaten, and/or the meat of these animals. This was navigated by listing a range of different animal groups (e.g. garkman (frogs)) or specific animals that are included in the Western scientific understanding of the term ‘animal.’ This excluded invertebrate fauna, because the project scope focused on vertebrates. Discussion of the concept of an animal was not always necessary and some Ŋaḻapaḻmi were familiar with the concept, namely those with Western land management experience. As there was no direct translation for the words ‘culturally significant’ or ‘important’, it was recommended to leave the English word ‘important’ in the Yolŋu Matha interview questions (Table 2, Question 2). However, we did introduce two follow-up questions to elaborate on the meaning of this, specifically asking about the clan connections and ceremonial and nutritional value of the animals (Table 2, Questions 2a, 2b).

Ranking of Laynhapuy priority animals

Priority animals recorded during elicitation sessions were given a score of 1 for each session they were mentioned in (including if they were mentioned several times during a session). The priority animal scores were tallied to generate an importance rank (Tables 3, 4, 5 and 6). Because Western scientific species and Yolŋu animal classifications are not always commensurable, some scores could not be calculated at the species level. For example, small native rodents are categorised (and discussed) by Ŋaḻapaḻmi as nyiknyik, and all sea turtle species, although separately named, all fall under the group name of miyapunu. If the animal group name rather than unique species name was nominated by Ŋaḻapaḻmi, all species within the animal group were given a score of 1. Both Western scientific and Yolŋu ‘animal group’ classifications are provided in the tables. Yolŋu animal classifications identified in the sessions were highlighted orange in the table and are what we referred to as Laynhapuy priority animals in the results. Yolŋu animal groups are from data supplied by the Yirralka Rangers and Macquarie University (unpubl. data) and Rudder (1977, 1999). The Yirralka Rangers were consulted to verify correct terminology and content of the priority animal list.

| Western classification group | Yolŋu classification groups | Yolŋu Yäku (name) | Common name | Scientific name | Moiety | Associated bäpurru | Rank | Conservation status | CWR | 110 NPS | Reasons for worry | Eaten? | ALA records | YR-MQ project | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mammals | Marrtjinyami wäyin (walking animals) | Waṉ’kurra | Northern brown bandicoot | Isoodon macrourus | Y | Guma, Gupa, Maḏa, Maŋg, Rith | 6 | LC (IUCN) | ✓ | NSA | ✓ | 6 | 24 | ||

| Barkuma’ | Northern quoll | Dasyurus hallucatus | Y | Maŋg, Rith, Maḏa, Dhaḻ, Wang | 2 | CE (NT) | ✓ | ✓ | NSA | 3 | 1 | ||||

| Djirrmaŋa’ | Short-beaked echidna | Tachyglossus aculeatus | Y | Ŋaym, Ḏäṯi | 2 | LC (IUCN) | ✓ | NSA | ✓ | 4 | 30 | ||||

| Nyiknyik (native rodents and dasyurids) | Dhurruyamba | Water rat | Hydromys chrysogaster | Y | Wang, Gupa, Maŋg, Rith | 1 | LC (IUCN) | ✓ | NSA | 1 | 8 | ||||

| Manbul | Black-footed tree-rat | Mesembriomys gouldii gouldii | Y | Wang, Gupa, Maŋg, Rith | 1 | E (NAT/NT) | ✓ | NSA | 3 | 10 | |||||

| Nyiknyik | Common planigale | Planigale maculata | Y | Wang, Maḏa | 1 | LC (IUCN) | NSA | 0 | 4 | ||||||

| Common rock rat | Zyzomys argurus | Y | Wang, Maḏa | LC (IUCN) | ✓ | NSA | 2 | 9 | |||||||

| Delicate mouse | Pseudomys delicatulus | Y | Wang, Maḏa | LC (IUCN) | NSA | 3 | 11 | ||||||||

| Dusky rat | Rattus colletti | Y | Wang, Maḏa | LC (IUCN) | ✓ | NSA | 2 | 3 | |||||||

| Grassland melomys | Melomys burtoni | Y | Wang, Maḏa | LC (IUCN) | ✓ | NSA | 23 | 56 | |||||||

| Red-cheeked dunnart | Sminthopsis virginiae | Y | Wang, Maḏa | LC (IUCN) | ✓ | NSA | 6 | 4 | |||||||

| Pale field-rat | Rattus tunneyi | Y | Wang, Maḏa | V (NT) | ✓ | NSA | 0 | 8 | |||||||

| Sandstone pseudantechinus | Pseudantechinus bilarni | Y | Wang, Maḏa | V (NAT) | NSA | 0 | 1 | ||||||||

| Brush-tailed rabbit rat | Conilurus penicillatus | Y | Wang, Maḏa | V (NAT/NT) | ✓ | NSA | 6 | 0 | |||||||

| Rupu (possums) | Rupu/Marrŋu | Northern brushtail possum | Trichosurus vulpecula arnhemensis | Y | Maŋg, Rith, Maḏa, Dhaḻ, Wang | 4 | E (NT) | ✓ | ✓ | NSA, IBF | ✓ | 2 | 8 | ||

| Wäraŋ | Savanna glider | Petaurus ariel | D | Djap, Dhuḏ | 3 | NL | ✓ | NSA | 3 | 5 | |||||

| Weṯi ga dhum’thum (kangaroos and wallabies) | Gataḻa | Eastern short-eared rock wallaby | Petrogale wilkinsi | D | Gupa, Dhaḻ | 1 | LC (IUCN) | ✓ | NSA | ✓ | 3 | 6 | |||

| Garrtjambal | Antilopine wallaroo | Osphranter antilopinus | Y, D | Guma, Dhaḻ, Gupa, Rith | 1 | LC (IUCN) | NRR | ✓ | 6 | 12 | |||||

| Mammals total | 73 | 200 |

Yolŋu animal classification nominated by Ŋaḻapaḻmi during elicitation sessions as being of concern or priority are highlighted in orange. Other classifications were added subsequently and checked by the Yirralka Rangers. Animals were ranked from one to six, based onthe number of elicitation sessions they were identified in.

Yolŋu moiety (Y, Yirritja; D, Dhuwa; U, unknown); Yolŋu bäpurru associated with animals (Birr, Birrkili; Ḏäṯi, Ḏäṯiwuy; Dhaḻ, Dhaḻwaŋu; Dhuḏ, Dhuḏi Djapu; Djam, Djambarrpuyŋu (represents a set of clans indlucing Dhurili, Guyula, Wutjara), Djap, Djapu; Djar, Djarrwark; Gälp, Gälpu; Golu, Golumala; Guma, Gumatj; Gupa, Gupapuyŋu (represents a set of clans indlucing Birrkili, Daygurrgurr, Guyamirrilili, Wubulkarra), Guya, Guyamirrilil; Maḏa, Maḏarrpa; Maŋg, Maŋgalili; Marr, Marraŋu; Marra, Marrakulu; Ŋaym, Ŋaymil; Rirr, Rirratjiŋu; Rith, Ritharrŋu; Wang, Wangurri; Warr, Warramirri; Yarr, Yarrwiḏi), bolded bäpurru represent Waŋarr; Ŋaapami priority ranking across six elicitation sessions (2022–2023); Western conservation status (NL, not listed; LC, Least Concern; NT, Near Threatened; V, Vulnerable; E, Endangered; CE, Critically Endangered) across various listing levels (NT, Northern Territory; NAT, National; IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature); critical weight-range (CWR) mammal status; 110 National Priority Species (NPS) status; Ŋaapami reasons for worry (NSA, not seen anymore; NRR, no reason recorded; CTHM, changes to hunting method; DIH, decline in harvest; IBF, affected by fire); nutritional-value status; ALA fauna records (1935–2023) and fauna records (2018–2023) of the collaborative project between the Yirralka Rangers (YR) and Macquarie University (MQ) researchers (YR-MQ).

| Western classification group | Yolŋu classification groups | Yolŋu yäku (name) | Common name | Scientific name | Moiety | Associated bäpurru | Rank | Conservation status | 110 NPS | Reasons for worry | Eaten? | ALA records | YR-MQ project | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reptiles | Djanda (goannas) | Djanda | Yellow-spotted monitor | Varanus panoptes | D | Rirr | 4 | V (NT) | NSA, DIH | ✓ | 0 | 2 | ||

| Biyay’ | Sand goanna | Varanus gouldii | Y | Rith, Dhaḻ, Maḏa, Guma, Wang | 4 | LC (IUCN) | NSA | ✓ | 0 | 2 | ||||

| Min’tjirrtjirr | Mangrove monitor | Varanus indicus | D | Ŋaym, Ḏäṯi | 3 | LC (IUCN) | NSA, DIH | ✓ | 0 | 2 | ||||

| Wan’kawu | Water goanna | Varanus mertensi | D | Marra, Marr, Golu, Rirr, Djam | 3 | V (NT) | NSA, DIH | ✓ | 1 | 5 | ||||

| Bäpi (snakes) | Ḏärrpa | Northern brown snake | Pseudonaja nuchalis | D | Djam, Rirr | 1 | NL | NRR | 0 | 3 | ||||

| Garanaŋga’ | Common (green) tree snake | Dendrelaphis punctulatus | U | None listed | 1 | LC (IUCN) | NRR | 4 | 3 | |||||

| Gunuŋu’ | Black-headed python | Aspidites melanocephalus | Y | None listed | 1 | LC (IUCN) | NRR | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Djaykuŋ’ | Arafura file snake | Acrochordus arafurae | D | Gälp, Djar | 1 | LC (IUCN) | NRR | ✓ | 1 | 0 | ||||

| Gal’yunami wäyin (crawling animals; lizards) | Dhamiiŋu’ | Northern blue-tongued lizard | Tiliqua scincoides intermedia | D | Gälp | 1 | CE (NAT) | NSA | ✓ | 0 | 9 | |||

| Munhaŋaniŋ’ | Marbled velvet gecko | Oedura marmorata | U | None listed | 1 | LC (IUCN) | NSA | ✓ | 2 | 1 | ||||

| Miyapunu (sea turtles) | Dhalwaṯpu | Green turtle | Chelonia mydas | D | Djam, Djap, Dhuḏ, Rirr | 2 | NT (NT) | ✓ | CTHM | ✓ | 99 | 2 | ||

| Guwarrtji | Hawksbill turtle | Eretmochelys imbricata | Y | Warr, Yarr, Guma, Birr, Gupa | V (NT) | CTHM | ✓ | 454 | 0 | |||||

| Muḏuthu | Olive Ridley turtle | Lepidochelys olivacea | Y | None listed | V (NT) | ✓ | CTHM | ✓ | 12 | 0 | ||||

| Garriwa | Flatback turtle | Natator depressus | D | None listed | V (NAT) | CTHM | ✓ | 56 | 0 | |||||

| Minhala (long-necked turtles) | Minhala | Northern snake-necked turtle | Chelodina rugosa | Y | Dhal, Wang | 2 | NT (IUCN) | NSA, DIH | ✓ | 1 | 0 | |||

| Ŋukawu (short-necked turtles) | Gurrupiḻ (big), Maḏaltj (small) | Yellow bellied snapping turtle | Elseya flaviventralis | D | None listed | 1 | NL | NSA, DIH | ✓ | 1 | 0 | |||

| Northern yellow-faced turtle | Emydura tanybaraga | D | None listed | NL | ✓ | 0 | 0 | |||||||

| Reptiles Total | 632 | 30 |

Yolŋu animal classification nominated by Ŋaḻapaḻmi during elicitation sessions as being of concern or priority are highlighted in orange. Other classifications were added subsequently and checked by the Yirralka Rangers. Animals were ranked from one to six, based on the number of elicitation sessions they were identified in.

Yolŋu moiety (Y, Yirritja; D, Dhuwa; U, unknown); Yolŋu bäpurru associated with animals (Birr, Birrkili; Ḏäṯi, Ḏäṯiwuy; Dhaḻ, Dhaḻwaŋu; Dhuḏ, Dhuḏi Djapu; Djam, Djambarrpuyŋu (represents a set of clans indlucing Dhurili, Guyula, Wutjara); Djap, Djapu; Djar, Djarrwark; Gälp, Gälpu; Golu, Golumala; Guma, Gumatj; Gupa, Gupapuyŋu (represents a set of clans indlucing Birrkili, Daygurrgurr, Guyamirrilili, Wubulkarra); Guya, Guyamirrilil; Maḏa, Maḏarrpa; Maŋg, Maŋgalili; Marr, Marraŋu; Marra, Marrakulu; Ŋaym, Ŋaymil; Rirr, Rirratjiŋu; Rith, Ritharrŋu; Wang, Wangurri; Warr, Warramirri; Yarr, Yarrwiḏi), bolded bäpurru represent Waŋarr; Ŋaapami priority ranking across six elicitation sessions (2022–2023); Western conservation status (NL, not listed; LC, Least Concern; NT, Near Threatened; V, Vulnerable; E, Endangered; CE, Critically Endangered) across various listing levels (NT, Northern Territory; NAT, National; IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature); 110 National Priority Species (NPS) status; Ŋaapami reasons for worry (NSA, not seen anymore; NRR, no reason recorded; CTHM, changes to hunting method; DIH, decline in harvest; IBF, affected by fire); nutritional-value status; ALA fauna records (1935–2023) and YR-MQ project fauna records (2018–2023).

| Western classification group | Yolŋu classification group | Yolŋu yäku (name) | Common name | Scientific name | Moiety | Associated bäpurru | Rank | Conservation status | 110 NPS | Reasons for worry | Eaten? | ALA records | YR-MQ project | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birds | Butṯhunami wäyin (flying animals; birds) | Djirikitj | Brown quail | Coturnix ypsilophora | Y | Maḏa, Guma, Gupa | 2 | LC (IUCN) | IBF | 0 | 2 | |||

| Red-backed button quail | Turnix maculosus | Y | Maḏa, Guma, Gupa | LC (IUCN) | IBF | 0 | 1 | |||||||

| Buwaṯa | Australian bustard | Ardeotis australis | D | Rirr, Djam, Ḏäṯi, Ŋaym | 1 | LC (IUCN) | ✓ | 15 | 0 | |||||

| Biḏiwiḏi | Magpie lark | Grallina cyanoleuca | Y | Guma, Wang, Dhaḻ, Maḏa, Rith | 1 | LC (IUCN) | NRR | 33 | 2 | |||||

| Muḻunda | White-breasted woodswallow | Artamus leucorynchus | U | None listed | 1 | LC (IUCN) | NRR | 29 | 0 | |||||

| Buṯthunamiriw wäyin (non-flying birds) | Maḻwiya | Emu | Dromaius novaehollandiae | Y | Gupa, Maŋg, Rith, Dhaḻ, Maḏa, Guma | 1 | NT (NT) | NSA | ✓ | 8 | 2 | |||

| Birds Total | 85 | 7 |

Yolŋu animal classification nominated by Ŋaḻapaḻmi during elicitation sessions as being of concern or priority are highlighted in orange. Other classifications were added subsequently and checked by the Yirralka Rangers. Animals were ranked from one to six, based on the number of elicitation sessions they were identified in.

Yolŋu moiety (Y, Yirritja; D, Dhuwa; U, unknown); Yolŋu bäpurru associated with animals (Birr, Birrkili; Ḏäṯi, Ḏäṯiwuy; Dhaḻ, Dhaḻwaŋu; Dhuḏ, Dhuḏi Djapu; Djam, Djambarrpuyŋu (represents a set of clans indlucing Dhurili, Guyula, Wutjara); Djap, Djapu; Djar, Djarrwark; Gälp, Gälpu; Golu, Golumala; Guma, Gumatj; Gupa, Gupapuyŋu (represents a set of clans indlucing Birrkili, Daygurrgurr, Guyamirrilili, Wubulkarra); Guya, Guyamirrilil; Maḏa, Maḏarrpa; Maŋg, Maŋgalili; Marr, Marraŋu; Marra, Marrakulu; Ŋaym, Ŋaymil; Rirr, Rirratjiŋu; Rith, Ritharrŋu; Wang, Wangurri; Warr, Warramirri; Yarr, Yarrwiḏi), bolded bäpurru represent Waŋarr; Ŋaapaḻmi priority ranking across six elicitation sessions (2022–2023); Western conservation status (NL, not listed; LC, Least Concern; NT, Near Threatened; V, Vulnerable; E, Endangered; CE, Critically Endangered) across various listing levels (NT, Northern Territory; NAT, National; IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature); 110 National Priority Species (NPS) status; Ŋaapami reasons for worry (NSA, not seen anymore; NRR, no reason recorded; CTHM, changes to hunting method; DIH, decline in harvest; IBF, affected by fire); nutritional-value status; ALA fauna records (1935–2023) and YR-MQ project fauna records (2018–2023).

| Western classification group | Yolŋu classification groups | Yolŋu yäku (name) | Common name | Scientific name | Moiety | Associated bäpurru | Rank | Conservation status | 110 NPS | Reasons for worry | Eaten? | ALA records | YR-MQ project | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fish | Guya (Fishes) | Ŋuykal’ | Giant trevally | Caranx ignobilis | Y | Maŋg, Wang, Maḏa, Gupa | 1 | LC (IUCN) | CTHM | ✓ | 0 | 0 | ||

| Yambirrku’ | Blue tuskfish | Choerodon cyanodus | Y | None listed | 1 | LC (IUCN) | CTHM | ✓ | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Fish total | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| PS total | 791 | 238 |

Yolŋu animal classification nominated by Ŋaḻapaḻmi during elicitation sessions as being of concern or priority are highlighted in orange. Other classifications were added subsequently and checked by the Yirralka Rangers. Animals were ranked from one to six, based on the number of elicitation sessions they were identified in.

Yolŋu moiety (Y, Yirritja; D, Dhuwa; U, unknown); Yolŋu bäpurru associated with animals (Birr, Birrkili; Ḏäṯi, Ḏäṯiwuy; Dhaḻ, Dhaḻwaŋu; Dhuḏ, Dhuḏi Djapu; Djam, Djambarrpuyŋu (represents a set of clans indlucing Dhurili, Guyula, Wutjara); Djap, Djapu; Djar, Djarrwark; Gälp, Gälpu; Golu, Golumala; Guma, Gumatj; Gupa, Gupapuyŋu (represents a set of clans indlucing Birrkili, Daygurrgurr, Guyamirrilili, Wubulkarra); Guya, Guyamirrilil; Maḏa, Maḏarrpa; Maŋg, Maŋgalili; Marr, Marraŋu; Marra, Marrakulu; Ŋaym, Ŋaymil; Rirr, Rirratjiŋu; Rith, Ritharrŋu; Wang, Wangurri; Warr, Warramirri; Yarr, Yarrwiḏi), bolded bäpurru represent Waŋarr; Ŋaapami priority ranking across six elicitation sessions (2022–2023); Western conservation status (NL, not listed; LC, Least Concern; NT, Near Threatened; V, Vulnerable; E, Endangered; CE, Critically Endangered) across various listing levels (NT, Northern Territory; NAT, National; IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature); 110 National Priority Species (NPS) status; Ŋaapami reasons for worry (NSA, not seen anymore; NRR, no reason recorded; CTHM, changes to hunting method; DIH, decline in harvest; IBF, affected by fire); nutritional-value status; ALA fauna records (1935–2023) and YR-MQ project fauna records (2018–2023).

The ranked priority animals were visually displayed on a poster (Supplementary Fig. S1), which also included the current conservation status for species from the Northern Territory Territory Parks and Wildlife Act 1976 or EPBC Act 1999. The poster was presented at the Head Yirralka Ranger meeting, April 2023. During this meeting, the process of collating the list and calculating ranks was explained and discussed. Following time to consider this list after the meeting, the Yirralka Rangers endorsed the list, confirming that it represented priority animals for Yolŋu that could be targeted in a Laynhapuy IPA fauna strategy.

Laynhapuy priority animals: baseline data

The following two sets of baseline data were collated for the Laynhapuy priority animals from: (1) the Atlas of Living Australia (www.ala.org.au) (1935–2023); and (2) the eight-year collaboration between the Yirralka Rangers (YR) and Macquarie University (MQ) researchers. The Atlas of Living Australia data were checked and cleaned to remove duplicate entries (same latitude, longitude, date and time). Old data, that pre-dated electronic, satellite-enabled GPS devices, and were hence displayed in the ocean, were included in mainland estimates. Points located on islands were excluded because islands across northern Australia often constitute a refuge for many species (e.g. Woinarski et al. 2011) and reflect different conservation efforts, such as translocations and intensive monitoring.

The fauna data of the YR-MQ research team came from collaborative fauna surveys (2018–2023) and a camera trap monitoring program (2022–2023). The fourteen fauna surveys involved live-fauna trapping (Elliott, cage and pitfall traps), spotlighting and opportunistic sightings across three habitat sites. Camera-trap monitoring involved a five-camera array (50 m apart) across 86 sites and cameras were left out for five weeks. For the present analysis, species records for the camera monitoring were noted as presence/absence per site.

Results

Laynhapuy priority animals

Through the six elicitation sessions, Yolŋu Ŋaḻapaḻmi identified 30 Laynhapuy priority animals, including 26 animals representing nominal species and four animals that encompass multiple species according to Western classifications (Tables 3, 4, 5 and 6). These animals extend across 13 broader Yolŋu animal groups and span 43 nominal species in total (Tables 3, 4, 5 and 6). The highest-ranked animals (of a total rank of six, representing the six elicitation sessions) were found across the Yolŋu animal groups of Marrtjinyami wäyin (walking animals), Rupu (possums), and Djanda (goannas). These animals included waṉ’kurra (northern brown bandicoot, rank = 6), rupu/marrŋu (northern brushtail possum, rank = 4), djanda (yellow spotted monitor, rank = 4) and biyay’ (sand goanna, rank = 4). Animals that were mentioned across half of the elicitation sessions (rank = 3) included wäraŋ (savanna glider), min’tjirrtjirr (mangrove monitor) and wan’kawu (water goanna). All other animals were ranked one to two, including animals from Yolŋu animal groups Nyiknyik (native rodents and dasyurids), Weṯi ga dhum’thum (kangaroos and wallabies), Bäpi (snakes), Gal’yunami wäyin (crawling animals; lizards (excluding goannas)), Miyapunu (sea turtles), Minhala (long-necked turtles) and Ŋukawu (short-necked turtles) (Tables 3, 4, 5 and 6).

Laynhapuy priority animals: Yolŋu values

Across all Laynhapuy priority animals, 15 were Yirritja, 10 were Dhuwa, three had unknown moiety designations and two had both (Tables 3, 4, 5 and 6). Twenty-four animals were identified with bäpurru (clan) associations (including Waŋarr ancestor beings, or totemic species), with a total of 20 bäpurru (both Dhuwa and Yirritja clans) nominated from across the Laynhapuy IPA. The highest-ranked animals (ranked 4–6) all have known moiety designations and clan connections and are considered of nutritional value to Yolŋu.

Ŋaḻapaḻmi drew on traditional Yolŋu ontology/epistemology and contemporary understandings of Western biodiversity conservation and global change to discuss reasons for concern about animals and why they were not seeing them as often/anymore. It is important to note that in traditional Yolŋu ontology, in Waŋarr (totemic creation times), animals were shape-shifters, who could move between human and animal form, and given the size of the marks their actions left in the landscape they were powerful, gigantic beings. People are thought to embody the Waŋarr of their clan. In the example below, a landmark considered to be the wiṯitj (olive python) is referred to as Marcus Maymuru’s mother because his mother is from the clan for which wiṯitj is a major Waŋarr:

That dream, that hill. That’s wiṯitj. Nhuŋu ŋäṉḏi [your mother]. (Translated by Yalapuru Gumana for Nanikiya Marcus Maymuru.)

All animals still potentially have a Waŋarr aspect today and can intervene in human lives. Certain birds, for example, are harbingers of death or illness. Animals are considered to play a necessary role in ‘managing’ the land (in their own way), as Yolŋu do. In Yolŋu ontology animals therefore have consciousness and agency. They are considered to be aware of what they are doing and how they are affecting Country.

As Gathapura Munuŋgurr elaborated:

And plus the land himself, it’s important for the land to [have] animals. Because the animals are connected to the land. Because the land gives the natural resource to help them keep alive, so they can manage their land themselves and for the Yolŋu too. Because animals are also maintaining like Yolŋu.

Yet animals are also food, and much of the huge store of knowledge that Yolŋu hold about flora and fauna is directly related to their successful hunting and gathering economy. But although observed shifts in biodiversity trends (e.g. abundance, distribution) are often the basis for concern about animals, these are not understood simply in terms of presence, absence and observable, quantifiable threats as in western conservation frameworks.

When asked why the priority animals were important, Ŋaḻapaḻmi provided an array of responses. The majority of responses fell into one or both of the following categories: (1) they had an ancestral and ceremonial connection with them; (2) they were of nutritional value. Almost all priority animals (n = 24) share an ancestral and ceremonial connection with Yolŋu expressed through manikay (songlines) and buŋgul (dance/ceremony). Certain manikay and buŋgulmi animals can also be considered Waŋarr (totemic beings) and dhuyu (connected to sacred ceremony).

As Munurruŋ Bobby Wunuŋmurra translated for Marrarrawuy Margaret Waṉambi:

She wants to see it [waṉ’kurra] again because of the ceremonial connection with it. So, it’s important, she wish she could see it again and [know] how to look after it…It would be good to, you know, the next time you see that, you sing.

Priority animals valued by Yolŋu as food (n = 19) and/or for their medicinal properties, included many of the marrtjina wäyin (walking animals/mammals), weṯi ga dhum’thum (kangaroos and wallabies), maḻwiya (emu), djanda (goannas), miyapunu (marine turtles), minhala (freshwater turtles) and guya (fish).

As Muwarra Davis Marrawuŋgu and Julie Yunupiŋu discussed:

We are looking for this [Djanda (goannas)] now to eat. We’ve got none here. Bäyŋu [none].

And Butjiyaŋanybuy Thomas Marrkula discussed with his father Guthitjipuy Clancy Marrkula, after Clancy described gaṯala (eastern short-eared rock wallaby):

Ga [and] gaṯala rumbalku [really] old man?...That gataḻa, little kangaroo, I never seen it. Yo, because maybe long time they used to be seen or eaten mak [maybe].

Most Ŋaḻapaḻmi were ‘worried’ about more than one animal. Although reasons for worry were not recorded for all Laynhapuy priority animals, the reasons fell into the following four main categories: ‘not seen anymore’, ‘affected by fire’, ‘decline in harvest’ and ‘changes to traditional hunting method’ (Tables 3, 4, 5 and 6). The most prevalent reason for concern (n = 18) was that animals were ‘not seen anymore’ on Country, followed by those that were not seen when specifically hunting, resulting in a ‘decline in harvest’ (n = 6 animals).

As Butjiyaŋanybuy Thomas Marrkula translated for Jimmy Marrkula:

Barkuma’, waṉ’kurra and what else, biyay’, djanda they [are] all gone. Yo [yes]. Worrying about them because they haven’t seen them that’s why.

Yolŋu cited invasive species as the main reason for not seeing some animals much anymore, especially cane toads, which poisoned animals such as djanda (goannas), waṉ’kurra (northern brown bandicoot), barkuma’ (northern quoll) and nyiknyik (native rodents and small marsupials).

As Banul Munyarryun translated for Mr T Bidiŋal:

We want to see all that, those mammals, and reptiles, we want to see them back on the land…once that cane toad come in, you can’t see that [anymore].

Damage to habitats caused by feral gatapaŋa (water buffalo) and bikipiki (pigs) (specifically near wetlands) was also suggested by Yolŋu as a reason for not seeing some animals. And, in some instances, Yolŋu indicated that gatapaŋa and bikipiki were species they were ‘worried about’ because of the damage they cause (because of this status as a threat, they were not included in the priority list). Other threats included hot fires and ‘affected by fire’ was listed as a reason for worry for two animals (rupu (possums) and djirikitj (quails)) and climate change, including increasing temperatures and saltwater intrusion caused by sea-level rise (affecting freshwater ecosystems).

As Ganbilpil PJ White said:

Minhala [longneck freshwater turtles] are starting to die out. In guḻun [billabongs] there used to be räkay [water chestnut], wakwak [waterlilies] in clean, fresh water in billabongs. Now it’s gone. The saltwater table is rising, the habitat is changing, with global warming.

Some Ŋaḻapaḻmi indicated that they were worried about certain animals because of disrespect for and ‘change to [traditional] hunting methods’, namely for miyapunu (marine turtles), and guya (fish) (n = 3 animals).

As Gathapura Munuŋgurr described:

We are worrying about also turtle. People are taking lots of turtle, big numbers, and they are not hunting by boat, just going on Toyota Landcruiser and taking [them off the beach].

Laynhapuy priority animals: Western values and baseline data

Of all Laynhapuy priority animals (43 species), 10 are listed as ‘Threatened’ species at state, national or international levels, two are listed as ‘Critically Endangered’, two as ‘Endangered’, and four as ‘Vulnerable’ (spanning nine western recognised species in total) (Tables 3, 4, 5 and 6). Eighteen animals were considered of Least Concern (including 24 species) and three Near Threatened. Three Laynhapuy priority animals are not currently listed in conservation legislation, and include wäraŋ (savanna glider), därrpa (northern brown snake), ŋukawu (yellow bellied snapping turtle and northern yellow-faced turtle). The Laynhapuy Priority Animal list also contains three (4%) of the 69 terrestrial fauna of the national 110 Priority Species. Notably, barkuma’ (northern quoll), rupu (northern brushtail possum), and miyapunu (marine turtles) (specifically: dhalwaṯpu (green turtle) and birrŋarr (olive ridley turtle)) feature in the Laynhapuy, threatened-species, and 110 priority-species lists. The majority of mammals (nine animals, ~14 species) identified by Yolŋu as priority, are also critical weight-range (CWR) species.

In total, 1029 baseline data records were collated for the 43 Laynhapuy priority animals across the Laynhapuy IPA (including Stage 2) (Tables 3, 4, 5 and 6), with at least one record for each priority animal (except ŋuykal’, giant trevally). For the period 1935–2023, 791 records were found in the Atlas of Living Australia (accessed 28 February 2024). The YR-MQ collaborative fauna research made 238 new records from 2018 to 2023, substantially increasing the number of occurrence records for Laynhapuy priority species. Specifically, the YR-MQ project doubled the number of records for Nyiknyik (native rodents and marsupials), Rupu (possums) and Weṯi ga dhum’thum (wallabies and kangaroos) groups, and quadrupled records for the Marrtjinyami wäyin (walking animals; here ‘mammals’) group. The YR-MQ project detected all terrestrial reptile priority animals, increasing records for the Gal’yunami wäyin (crawling animals) group seven-fold, and for Djanda (goannas) 10-fold. Occurrence points were recorded at the species, rather than Yolŋu-identified animal level. There was strong bias in records of some species. For example, there was a large number of miyapunu (marine turtles) records and very few records minhala and ŋukawu (freshwater longneck and shortneck turtles), despite their being similarly ranked. Occurrence data exist for all species except the northern snapping turtle, and giant trevally.

Discussion

I think there is a question for all of us. I think we can’t manage the environment, because of climate change.... We can’t solve all of nature. Researchers are here to help us, and we can help them too. (Yinimala Gumana, Yirralka Rangers Co-Manager, 4 April 2023)

The Laynhapuy Priority Animal List (Supplementary File S1) represents a ‘working’ group of important animals that can inform locally meaningful management and research collaborations in the Laynhapuy IPA. Production and promotion of this Ŋaḻapaḻmi priority animal list addresses growing bottom-up and top-down calls for practical and meaningful inclusion of Indigenous values and interests in conservation decision-making, policies and programs (IPBES 2019; Wintle et al. 2019; Samuel 2021; Goolmeer et al. 2022b).

Capturing pluralistic worldviews

The Laynhapuy Priority Animal List (Tables 3, 4, 5 and 6) explored alignment of Yolŋu and Western values, necessitating attention to often divergent Yolŋu and Western scientific taxonomic terminologies. Pluralistic worldviews, epistemologies and ontologies demand that equitable cross-cultural approaches adopt a multiple evidence-based approach and avoid subsuming one into another (Tengö et al. 2014; Law et al. 2018; Ens et al. 2023). To promote Yolŋu values, the Priority List included the Yolŋu kinship (gurruṯu), moiety and bäpurru (clans) associated with each animal. Clans that sing or dance these animals were often discussed when Ŋaḻapaḻmi were asked why they were important. Publication of clan–animal connections directs future projects to acquire appropriate permissions for work, especially for major Waŋarr (totemic) animals. We also noted which species were nutritionally valuable (eaten) as a key aspiration for Ŋaḻapaḻmi was to not only see but to hunt and pass on knowledge of how to hunt and eat these animals.

The ranking system indicated a general consensus across participating Ŋaḻapaḻmi. We acknowledge that not all Ŋaḻapaḻmi across the Laynhapuy IPA were consulted to produce this published list; however, we followed Yolŋu governance structures and consulted Ŋaḻapaḻmi of the three Wards (Figs 1 and 2) as recommended by Yirralka Ranger co-researchers. Further, this list is not intended to be a static entity. Rather, the Laynhapuy Priority Animal List is a resource that the Yirralka Rangers can adapt over time, as recommended by Coe and Gaoue (2020) and Bundjalung leaders in Goolmeer et al. (2024). Experimentation with other ranking methods could be explored in the future to incorporate the nuances of Yolŋu priorities.

In response to the directive of the Yirralka Head Rangers, captured by the words of Senior Yirralka Ranger Banul Munyarrun presented at the front of this paper, the Laynhapuy Priority List also includes animal’s Western conservation status. Unlike previous attempts to bring Western scientific threatened species and Indigenous values together (e.g. DCCEEW 2022), we began by privileging Yolŋu priorities, and then added Western science metrics to broaden the knowledge base. Additionally, we indicated which species were on the national ‘110 Priority Species’ list (DCCEEW 2022) and were CWR mammals (35 g−5.5 kg), highlighting those most at risk from extinction (Woinarski 2015). Notably, higher ranking from Yolŋu Ŋaḻapaḻmi did not always correspond with Western threatened-species status. For example, the waṉ’kurra (northern brown bandicoot) was the highest-ranked Laynhapuy priority animal and is considered of Least Concern by Western science. This could reflect the cultural significance of the waṉ’kurra as an important Waŋarr (totemic being) and food source and/or that local knowledge of declines are not captured by Western conservation metrics (Campbell et al. 2022). This shows the benefit of including local or regional knowledge to identify local or regionally important species.

The importance of scale

Scale is considered an important point of difference between Indigenous and Western knowledge systems (Wohling 2009). A global list of CSS identified 48 species in the Oceania region, including Australia (Reyes-García et al. 2022). None of the Laynhapuy priority animals was listed for the Oceania region, and only two were listed as ‘global’ CSS (wurrumbili, leatherback turtle; gärun, loggerhead turtle) (Reyes-García et al. 2022). The discrepancy between the global and local CSS here is stark and highlights the disconnect between large- and small-scale assessments and importance of on-ground Indigenous-led nomination of priority animals (Coe and Gaoue 2020; Goolmeer et al. 2024). Furthermore, respecting Indigenous people’s agency to decide which animals are a priority to them, rather than the use of a ‘yes/no’ metric of cultural significance can open up space for ontological pluralism and opportunity to empower local decision-making and livelihoods (Naughton-Treves et al. 2005; Hill et al. 2020), congruous with international directives for inclusive conservation (IPBES 2019; CBD 2021).

Baseline data on Laynhapuy priority animals

Assessment of the Laynhapuy priority-animal baseline data highlighted the paucity of animal research in this region compared with other parts of northern Australia such as Kakadu National Park (Woinarski et al. 2007, 2011). The lack of Western data does not correlate with absence but highlights an opportunity for further research by the Yirralka Rangers through collaborative surveys. The YR-MQ animal research over five years significantly increased the recorded distribution and presence of highly ranked priority animals, especially the mammals and varanid lizards. Increasing the species occurrence records for this region not only directs local management efforts but can attract competitive conservation funding that often targets threatened species and relies on observation records.

Interestingly, the ALA data were collected over 88 years, whereas the collaborative YR-MQ surveys were conducted over five years. The comparative records in Tables 3, 4, 5 and 6 illustrate that through culturally meaningful and inclusive approaches, data gaps can be addressed on remote Aboriginal-owned and -managed lands, building on evidence from other studies, such as Ens et al. (2016). Furthermore, by focussing on culturally significant species, research and management not only addresses Western species conservation pursuits (quantification and distribution mapping) but also invests in cultural knowledge maintenance and empowerment in the conservation space. Identification of known locations, or lack thereof, of highly ranked Laynhapuy priority animals, such as wan’kurra, provides practical direction for further research and management action.

The YR-MQ research focussed on terrestrial surveys and mainly targeted mammals and reptiles on the basis of initial concern for these groups. The bird, turtle and fish records were opportunistic and/or collected during hunting activities as part of the cross-cultural survey method. Further ethnographic research to record Ŋaḻapaḻmi ‘memory knowledge’ of past observations, similar to Russell et al. (2023) and Campbell et al. (2022), could add records for ‘Data Deficient’ Laynhapuy priority animals to detect whether in fact they were always in low numbers, declining in this region, or are still present and just have not been recorded yet.

Lost in translation?

For many of the priority animals, Ŋaḻapaḻmi stated that they were ‘bäyŋu nhäma’ (not seeing) the animals anymore, or not as much as people once did. However, this question was ambiguous for some people and required qualification. For example, some Yolŋu were ‘worried’ about certain animals as cultural obligations were not being followed, such as correct hunting methods, or they were worried as a particular animal was invasive, or because an animal was poisonous or venomous. Similarly, when asking which species were ‘important’, some Ŋaḻapaḻmi asked what this meant, as there is no direct translation of the word important in Yolŋu Matha. There is also no direct translation for ‘animal,’ and the words ‘warrakan’ and ‘wäyin’ which were used as translations refers to edible animals only (Boll 2006) and so Ŋaḻapaḻmi and the research team often had to negotiate meanings of terms during interviews to reach a mutual understanding. It is important to note that the discussion about what organisms qualified as animals may have been influenced by the interests of the YR-MQ research group in vertebrate terrestrial fauna. Hence, no invertebrate fauna were mentioned and only 8 of 30 aquatic or marine species were nominated as a concern by Ŋaḻapaḻmi. These difficult translations and potential bias warrant caution for future research to ensure sound knowledge of local language, communication style and terms. Secondary qualifying statements are often essential when working in cross-cultural bilingual contexts to check understandings, and collaboration with expert linguists is strongly advised.

Further, ontological and epistemological differences between cultures can result in communication disconnect and gaps in understanding. In this study, it is likely that Yolŋu spiritual dimensions of understanding and concern for Country and animals were not fully captured. For example, when the Laynhapuy Priority Animal List poster was fed back to the Head Yirralka Rangers by the researchers, they spoke about the animals being ‘clever’ and hiding from the research team and hypothesised that failure to observe animals could be connected to fulfilment (or not) of ceremonial obligations. Such comments imply that the animals may actually be abundant and they were exhibiting a kind of ‘cultural’ agency that would not be attributed to them within a Western framework. This reinforces the need for continued discussion and refinement of the list and questions to ensure that they are accurate, relevant and appropriate.

Taxonomic differences

Differences in Yolŋu and Western priority-animal classifications also created challenges in synthesis of the priority animal list. Yolŋu sometimes have no name for what Western science designates as a species; conversely, in some cases there are multiple names for different members of what would be considered a single species under Western frameworks (Dickson 2015; Si 2020). Examples where Yolŋu differentiate males from females but there is no overarching Yolŋu name include the antilopine wallaroo and northern brushtail possum. Freshwater turtles are named differentially according to their size or life-stage (whether or not they are aestivating). Some priority animals were identified using an animal-group term that does not correspond to Western notions of species, but to a group of species, such as the Miyapunu and Nyiknyik groups. The term Miyapunu encompasses several turtle species (and sometimes also dugong), all of which also have Yolŋu names. Miyapunu anatomy is also named in detail and there are laws about how to cut and eat them according to Rom. Nyiknyik is a general term often used for several species of rodents and dasyurids, some of which do have specific Yolŋu names; however, increasingly, people do not know these and use the more well-known group name. In this study, Yolŋu did not know unique names for the small nyiknyik that Western science splits into species.

The Yolŋu group names for morphologically similar taxa, such as nyiknyik or djanda (large goannas), did at times add uncertainty to discussions. Ŋaḻapaḻmi expressed concern that the younger generations were learning only the general names for some animal groups, for example, referring to all large goannas as djanda, or all rodents and dasyurids as nyiknyik. The loss or shift in salience of traditional animal names has also been noted for other language groups in Arnhem Land (e.g. Dickson 2015), even where intergenerational language transmission is strong (e.g. Si 2020). Changes to lifestyles and hunting practices, as well as species decline, were implicated in the loss of specialised taxonomic terminology (Si 2020), whereas totemism, songlines and social practice (‘related to abundance and physical proximity of species’) were considered factors associated with maintained salience of taxonomic names (Dickson 2015).

As mentioned in the introduction, certain animals may also have ceremonial names that are taught only to the right people according to Yolŋu Rom (Morphy 1991; Boll 2006). The Yolŋu animal names featured in the Laynhapuy Priority Animal List are public knowledge names only. In the wake of changing lifestyles and species decline, manikay (songlines) may serve as a means of maintaining specialised terminology relating to animals (alongside other phenomena). However, the information in manikay becomes increasingly abstract and esoteric unless it is reinforced by experience in place that supports intergenerational transmission, as described by Dhaḻwaŋu Ŋaḻapaḻmi in Boll (2006). Such nuances of Indigenous language are at risk of being lost due to the forces of globalisation and technological expansion (Maffi 2001). Deliberate actions to maintain cultural diversity are essential, especially in propitious niches such as the thriving Indigenous Ranger and Caring for Country programs (Moorcroft 2016) and biocultural conservation initiatives more generally (Maffi and Woodley 2012; Sterling et al. 2017; Reyes-García et al. 2022, 2023).

Continued application of the Ŋaḻapaḻmi prioritisation approach by the Yirralka Rangers may assist the maintenance of Yolŋu taxonomic terminology and CSS salience in younger generations, enabling active biocultural conservation. As in other Indigenous societies, Yolŋu knowledge is embodied and performed, and terminology is passed on through experience rather than classroom instruction (Morphy 1991; Christie 2007). As Yolŋu Ŋaḻapaḻmi in this project discussed, this knowledge has been largely passed on through hunting (discussed also by Dhawaŋu Ŋaḻapaḻmi in Boll (2006)). Similarly, support for ‘on-Country community gatherings linked to cultural practice’ was identified by the Bundjalung people to positively benefit conservation of CSS (Goolmeer et al. 2024) and by Yolŋu for adaptations to climate-driven environmental and social changes Petheram et al. (2010).

Conclusions

Localised species prioritisation efforts can guide on-ground animal management and cross-cultural research collaborations. Prioritisation allows for more effective use of resources, especially in remote sparsely populated areas such as the location of this case study. This case study followed local Yolŋu governance structures and cultural protocol to generate a Ŋaḻapaḻmi-led animal priority list, complemented with Western science values. The ‘working’ list concept supports an adaptive management approach, which aligns with Indigenous stewardship of Country (Berkes et al. 2000) and can continue to provide IPA decision-makers with a better understanding of what assets Ŋaḻapaḻmi want to protect.

As Goolmeer et al. (2024, 1628) argued, ‘Indigenous peoples are ready to sit at decision-making tables’ to inform management of Country. This case study has demonstrated that local Indigenous governance structures and organisations such as ranger groups are capable of asserting their own priorities, (rather than having them defined by a third party) and can also be interested in engaging with Western science metrics and methods in collaborative research. As the number of Australian Indigenous Protected Areas continues to increase, respectful, collaborative work that builds bridges between Indigenous and Western priorities is needed to inform equitable and locally relevant Australian biodiversity conservation. As Yirralka Rangers Co-Manager Yinimala Gumana expressed at the Head Ranger meeting (4 April 2022):

We need to work together, learn together and walk together.

Data availability

Data may be provided upon request depending on permissions from the research team and Yolŋu Ŋaḻapaḻmi.

Conflicts of interest

Emilie Ens is a Guest Editor of the ‘Indigenous and cross-cultural wildlife research in Australia’ special issue of Wildlife Research. To mitigate this potential conflict of interest they were blinded from the review process.

Declaration of funding

Funding for this research was provided by the Australian Research Council Linkage Grant with industry partners the Laynhapuy Homelands Aboriginal Corporation and The Nature Conservancy (LP200301589). Funding was also provided by the Australian Academy of Sciences’ Max Day Environmental Science Fellowship (2022) and the Margaret Middleton Fund for Endangered Australian Native Vertebrate Animals (2023). This research was also supported by the Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) Scholarship and Macquarie University Higher Degree Research student fund.

Acknowledgements

We first and foremost thank Yolŋu Ŋaḻapaḻmi of the Laynhapuy IPA, without whom this research could not have been possible and pay our respects to Yolŋu Ŋaḻapaḻmi past and present. Thanks go to all Yirralka Ranger staff, with specific thanks to the Yirralka Rangers who co-created and translated the interview questions: Munurruŋ Bobby Wunuŋmurra, Banygada Brendan Wunuŋmurra, Nyemburr Munuŋgurr and LHAC Board Member Yananymul Munuŋgurr. Specific thanks also go to the Yirralka Rangers who co-led or assisted with interviews: Butjiyaŋanybuy Thomas Marrkula, Munurruŋ Bobby Wunuŋmurra, Bandibandi Wunuŋmurra, Banygada Brendan Wunuŋmurra, Garrwatj Darren Waṉambi, Banul Munyarryun, Ḻuḻparr George Waṉambi, Nyemburr Munuŋgurr, Ganbilpil PJ White and Yalapuru Gumana. Thanks go to volunteers who assisted with the interviews: Daniel Smuskowitz, Tristan Guillemin and Stephen Gurruwiwi.

References

Austin BJ, Robinson CJ, Fitzsimons JA, Sandford M, Ens EJ, Macdonald JM, Hockings M, Hinchley DG, McDonald FB, Corrigan C, Kennett R, Hunter-Xenie H, Garnett ST (2018) Integrated measures of indigenous land and sea management effectiveness, challenges and opportunities for improved conservation partnerships in Australia. Conservation and Society 16, 372-384.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Baker L, Woenne-Green S, Mutitjulu Community (1992) The role of Aboriginal ecological knowledge in ecosystem management. In ‘Aboriginal involvement in parks and protected areas’. (Eds J Birckhead, T De Lacy, L Smith) pp. 65–74. (Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies: Canberra, ACT Australia)

Berkes F, Colding J, Folke C (2000) Rediscovery of traditional ecological knowledge as adaptive management. Ecological Applications 10, 1251-1262.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Boll V (2006) Following Garkman, the frog, in north eastern Arnhem Land (Australia). Australian Zoologist 33, 436-445.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Campbell BL, Yirralka Rangers, Yolŋu Knowledge Custodians, Gallagher RV, Ens EJ (2022) Expanding the biocultural benefits of species distribution modelling with Indigenous collaborators: case study from northern Australia. Biological Conservation 274, 109656.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Coe MA, Gaoue OG (2020) Cultural keystone species revisited: are we asking the right questions? Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 16, 70.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Dickson GF (2015) Marra and Kriol: the loss and maintenance of knowledge across a language shift boundary. PhD thesis, The Australian National University, Canberra, ACT, Australia. Available at https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/items/0d2443ab-ebe4-47e3-a08b-b3ee86df98b8

Ens EJ, Pert P, Clarke PA, Budden M, Clubb L, Doran B, Douras C, Gaikwad J, Gott B, Leonard S, Locke J, Packer J, Turpin G, Wason S (2015) Indigenous biocultural knowledge in ecosystem science and management: review and insight from Australia. Biological Conservation 181, 133-149.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ens E, Scott ML, Yugul Mangi Rangers, Moritz C, Pirzl R (2016) Putting indigenous conservation policy into practice delivers biodiversity and cultural benefits. Biodiversity and Conservation 25, 2889-2906.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ens EJ, Rossetto M, Costello O (2023) Recognising Indigenous plant-use histories for inclusive biocultural restoration. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 38(10), 896-898.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Fijn N (2014) Sugarbag dreaming: the significance of bees to Yolngu in Arnhem Land, Australia. Humanimalia 6, 41-61.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Fitzsimons J, Russell-Smith J, James G, Vigilante T, Lipsett-Moore G, Morrison J, Looker M (2012) Insights into the biodiversity and social benchmarking components of the northern Australian fire management and carbon abatement programmes. Ecological Management & Restoration 13, 51-57.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Freitas CT, Lopes PFM, Campos-Silva JV, Noble MM, Dyball R, Peres CA (2020) Co-management of culturally important species: a tool to promote biodiversity conservation and human well-being. People and Nature 2, 61-81.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Game ET, Kareiva P, Possingham HP (2013) Six common mistakes in conservation priority setting. Conservation Biology 27, 480-485.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Garibaldi A, Turner N (2004) Cultural keystone species: implications for ecological conservation and restoration. Ecology and Society 9(3), 1.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Garnett ST, Burgess ND, Fa JE, Fernández-Llamazares Á, Molnár Z, Robinson CJ, Watson JEM, Zander KK, Austin B, Brondizio ES, Collier NF, Duncan T, Ellis E, Geyle H, Jackson MV, Jonas H, Malmer P, McGowan B, Sivongxay A, Leiper I (2018) A spatial overview of the global importance of Indigenous lands for conservation. Nature Sustainability 1, 369-374.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Goolmeer T, van Leeuwen S (2023) Indigenous knowledge is saving our iconic species. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 38, 591-594.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Goolmeer T, Skroblin A, Grant C, van Leeuwen S, Archer R, Gore-Birch C, Wintle BA (2022a) Recognizing culturally significant species and Indigenous-led management is key to meeting international biodiversity obligations. Conservation Letters 15, e12899.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Goolmeer T, Skroblin A, Wintle BA (2022b) Getting our Act together to improve Indigenous leadership and recognition in biodiversity management. Ecological Management & Restoration 23, 33-42.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Goolmeer T, Costello O, Culturally Significant Entities workshop participants, Skroblin A, Rumpff L, Wintle BA (2024) Indigenous-led designation and management of Culturally Significant Species. Nature Ecology & Evolution 8, 1623-1631.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Gore-Birch C, Costello O, Goolmeer T, Moggridge BJ, van Leeuwen S (2020) A submission from the Indigenous reference group of the national environmental science program’s threatened species recovery hub for the independent review of the Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999: a case for culturally significant species. (Indigenous Working Group of the Threatened Species Recovery Hub and the Threatened Species Recovery Hub)

Hill R, Walsh FJ, Davies J, Sparrow A, Mooney M, Wise RM, Tengö M (2020) Knowledge co-production for Indigenous adaptation pathways: transform post-colonial articulation complexes to empower local decision-making. Global Environmental Change 65, 102161.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Howitt R, Suchet-Pearson S (2006) Rethinking the building blocks: ontological pluralism and the idea of ‘management’. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 88, 323-335.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Keith DA, Rodríguez JP, Brooks TM, Burgman MA, Barrow EG, Bland L, Comer PJ, Franklin J, Link J, McCarthy MA, Miller RM, Murray NJ, Nel J, Nicholson E, Oliveira-Miranda MA, Regan TJ, Rodríguez-Clark KM, Rouget M, Spalding MD (2015) The IUCN red list of ecosystems: motivations, challenges, and applications. Conservation Letters 8, 214-226.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Law EA, Bennett NJ, Ives CD, Friedman R, Davis KJ, Archibald C, Wilson KA (2018) Equity trade-offs in conservation decision making. Conservation Biology 32, 294-303.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

LHAC (2017) Laynhapuy Homelands Aboriginal Corporation (LHAC). Available at https://www.laynhapuy.com.au [accessed 1 February 2024]

McDonald JA, Carwardine J, Joseph LN, Klein CJ, Rout TM, Watson JEM, Garnett ST, McCarthy MA, Possingham HP (2015) Improving policy efficiency and effectiveness to save more species: a case study of the megadiverse country Australia. Biological Conservation 182, 102-108.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

McKemey MB, Patterson M, Banbai Rangers, Ens EJ, Reid NCH, Hunter JT, Costello O, Ridges M, Miller C (2019) Cross-cultural monitoring of a cultural keystone species informs revival of indigenous burning of country in South-Eastern Australia. Human Ecology 47, 893-904.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Moorcroft H (2016) Paradigms, paradoxes and a propitious niche: conservation and Indigenous social justice policy in Australia. Local Environment 21, 591-614.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Naughton-Treves L, Holland MB, Brandon K (2005) The role of protected areas in conserving biodiversity and sustaining local livelihoods. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 30, 219-252.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |