Partnering and engaging with Traditional Owners in conservation translocations

Dorian Moro A , Rebecca West

A , Rebecca West  B * , Cheryl Lohr

B * , Cheryl Lohr  C , Ruth Wongawol A and Valdera Morgan A

C , Ruth Wongawol A and Valdera Morgan A

A

B

C

Abstract

Conservation translocations are increasing in number and so too is the interest and expectation from Traditional Owners (TOs) that they will be involved in management occurring on their Country.

Our objectives were to identify the levels of past TO engagement as experienced through the western and TO lenses, examine the key steps, challenges and opportunities that emerged from survey responses, and also to provide a case study of a conservation translocation that describes Indigenous involvement to support a reintroduction of golden bandicoots (Isoodon auratus) in Australia from Martu Country (Western Australia) to Wongkumara and Maljangapa Country (New South Wales).

The key questions the surveys sought to address to western practitioners were as follows: (1) what types of TO involvement were observed; (2) if TOs were not involved in the translocation, was there a reason; and (3) for each translocation project where TOs were involved, (a) why was this engagement sought by their agency; (b) what worked well in terms of involvement and partnerships; and (c) how could these partnerships be improved? From a TO lens, perspectives were sought with a survey addressing the following questions: (1) how were you involved in the translocation; (2) why was it important to you and your community; and (3) ow would you like to be involved in the future?

Of 208 Australian translocations, 27% involved TOs. The following four themes emerged from the survey responses: the need to recognise and adopt the cultural dimension of conservation translocations on Indigenous Country, maintain on-Country relationships between western practitioners and TOs, enable co-ownership of projects, and maintain community links between western and TO practitioners. The golden bandicoot translocation partnership provided a foundation for TO engagement across generations, setting the scene for long-term and future translocation collaboration opportunities.

The perspectives of all participants involved in conservation translocations highlighted a common theme: the need to support TOs to be engaged fairly, to be culturally safe during their engagement, and to enable them to be part of a wider project and community team. The case study highlighted a sequential approach for engaging the TO organisation and supporting TOs to work alongside western practitioners to capture, record and transport animals from their Country to a new (reintroduction) site.

We provide suggestions for non-Indigenous managers and practitioners to consider a cultural dimension to conservation translocations when engaging TOs.

Keywords: Aboriginal, conservation translocation, Indigenous, Martu, Matuwa, partnership, reintroduction, traditional ecological knowledge, Traditional Owner.

Introduction

Conservation translocations, that is, the intentional movement of flora or fauna from one area to another to conserve species and restore ecosystems, remain an important conservation tool to support species recovery, particularly in Australia (Armstrong et al. 2015). With these translocations comes important partnerships between organisations involved in aspects of the project. Notwithstanding these partnerships, there is a growing awareness of the value brought to a conservation project through the engagement of Traditional Owners (TOs), and an increased willingness for conservation organisations to facilitate such engagements, as occurs in other parts of the world (Schley et al. 2022). This interest is especially timely given the expansion of land that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and associated organisations in Australia now legally hold, the broad cultural desire for reconciliation, and the reconnection of people with the natural world (Parker 2008).

Traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) is commonly defined as ‘a cumulative body of knowledge, practice and belief, evolving by adaptive processes and handed down through generations by cultural transmission, about the relationship of living beings with one another and with their environment’ (Berkes 2012, p. 3). Globally, western researchers within the fields of natural resource management started incorporating TEK into studies in the 1990s, drawing on methodologies commonly used in social science (Ramos 2018). Although many definitions and uses of TEK exist, it has been suggested that TEK should be broadly understood as a collaborative concept that brings different people working for different institutions closer to a degree of mutual respect for one another’s sources of knowledge to create long-term processes to better steward and manage the environment and natural resources (Whyte 2013). Incorporating TEK into translocation projects can increase the chances of success (Woodward et al. 2020), and fulfil significant cultural aspirations (e.g. for the black-footed rock-wallaby, Petrogale lateralis, Muhic et al. 2012).

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are important landowners and managers of land and Sea Country in Australia. We refer to Country as a term used to describe the land, waterways and sky to which TOs are connected through the complexities of laws, lore, customs, language, cultural practices, spiritual beliefs, ancestral connections, family, identity and custodianship of the surrounding environment (www.aiatsis.gov.au). We recognise TOs as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples who have an ongoing relationship with Country, and as custodians of lands and waters regardless of legal tenure. TO Country extends beyond the boundaries of modern tenure and may overlap public, private, natural, agricultural and industrial land.

Partnering with the TOs of these lands becomes an integral component of establishing important relationships that can positively influence the success of conservation initiatives (Berkes et al. 2000; Hill et al. 2015). However, these partnerships require people to develop respectful relationships and alternative working relationships that may be outside the standard western lens of work engagements that many scientists and managers have been exposed to. Building relationships with TOs and their organisations, although desirable if not expected, remains an unclear and unsteady path for many western scientists who have limited to no experience in working in partnership with TOs (e.g. McLeod et al. 2018).

In New Zealand, the inclusion of Indigenous people in land management programs is required by both law and policy (Conservation Act 1987; Resource Management Act 2002). However, many approaches to management have been challenged to meaningfully incorporate this inclusion (Kitson et al. 2018). Similarly, although not a legally binding objective, the Australian National Threatened Species Strategy emphasises the increasing potential for Indigenous people to be formally involved in threatened species management (Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water 2022). Unfortunately, involvement may not necessarily reflect co-contributions; a study of a Northern Tanami Indigenous Protected Area shows that ‘breakdowns in communication, planning and programme implementation [occurred] because of underdeveloped partnerships’ (Walker 2010, p. 309), resulting in significant differences between Indigenous and western perspectives. Here, priorities remained unbalanced, and management outcomes became constrained (Walker 2010). Similar experiences where environmental partnerships have been negatively affected by a disconnect between management approaches and cultural perspectives are reported (Muller 2012).

Leiper et al. (2018) assessed the level of involvement of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples within the context of conservation programs from databases; they found that almost 60% of threatened species were present on Native Title lands. The importance of Indigenous land management was further highlighted by Renwick et al. (2017); 75% of the projected distributions of threatened terrestrial and freshwater species overlap Indigenous lands, suggesting that successful conservation requires some level of Indigenous involvement. However, there are no assessments gained directly from western or TO practitioners to understand the level of engagement and contribution of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to conservation translocations in Australia. Direct information from the people who work on these conservation projects provides us with an appreciation of the realised v. actual extent of perspectives and partnerships with and from TOs, and the subsequent opportunities to improve conservation efforts on Indigenous lands. Perspectives from both a western lens and a TO lens (including those gained from TEK) are useful indicators of desirable conservation goals; they influence our expectations and the development of key performance indicators, including the success of management actions and conservation outcomes (Abecasis et al. 2013; Bennett and Dearden 2014; Jefferson et al. 2014; Beyerl et al. 2016; Bennett et al. 2019).

In this paper, we survey the perspectives of Australian non-Indigenous and TO practitioners who have been involved in conservation translocations. Our objectives were to identify the perspectives and levels of past TO engagement as experienced through the western and TO lenses, with a view to strengthening future partnerships in translocation projects across Australia. Perspectives, we hypothesised, inform and reflect a practitioner’s hopes and desires but also their doubts, anxieties, and historical wounds (akin to expectations, Fabre et al. 2021). We extend the survey to describe one case study that involved a partnership between western scientists and TO (Martu in Western Australia, WA, and Wongkumara and Maljangapa in New South Wales, NSW) organisations to reintroduce golden bandicoots (Isoodon auratus) from one Indigenous Country (lands of the Tarlka Matuwa Piarku peoples) to another Country (lands of the Wadigali peoples). The key steps, challenges and opportunities that emerged from this case study will be related back to the survey findings and recommendations. This partnership provided a foundation for TO engagement across generations, setting the scene for long-term and future conservation translocation collaborations for the organisations. Finally, we provide suggestions for non-Indigenous managers and practitioners to consider when engaging TOs in future conservation translocations.

Methods

Survey methodology

We solicited the perspectives and expectations of practitioners involved in wildlife translocations by written surveys and verbal communication; perspectives were sought from a western-practitioner lens and a TO lens. We targeted practitioners with field experience in conservation translocations as we focused on the experiences and learnings from people at the operational end of the project rather than policy or senior management people who may not have had direct experience with translocations or with TOs. From the survey responses received, information was collated to identify the current state and motivations for engaging TOs in translocation projects. The intent was to focus on the type of work that TOs were engaged in, but also the level of engagement, and the opportunities for future improvements.

Western-practitioner surveys were emailed to participants involved in wildlife-translocation projects across Australia from October to December 2023, and were available at a translocation conference workshop held in Perth in November 2023. The following questions were asked: (1) what type of TO involvement was observed; (2) if TOs were not involved in the translocation, was there a reason; (3) for each translocation project where TOs were involved, (a) why was this engagement sought; (b) what worked well in terms of involvement and partnerships; and (c) how could these partnerships be improved?

To gain a TO perspective, and to ensure that the survey was culturally respectful, western practitioners who worked with TOs were requested to speak or ‘yarn’ with them face-to-face in a non-interrogative environment by using basic survey questions. This ‘yarning’ (sensu Bessarab and Ng’andu 2010) enables a person to develop and build a relationship with a TO that reflects an informal and relaxed discussion with a familiar person and in a familiar environment. The approach meant that TOs could be asked a series of open-ended questions by the people they held relationships with (such as ranger coordinators). Participants were asked to talk about (1) how they were involved in a translocation, (2) why they considered [the translocation] was important to them or their community and (3) how would they like to be involved in the future.

Results were collated from the survey responses received. Surveys were not mutually exclusive to a particular translocation program; i.e. separate western participants involved in the same translocation project provided their individual (independent) perspectives on their engagement with TOs. Likewise, TOs involved in the same translocation project provided their perspectives, although these may have been conducted either at a group (‘mob’) or individual level for each community, with the responses reflecting the output of their ‘yarning’. Regardless, for the purpose of this study, each TO survey response received was considered a unique response and perspective for the TOs involved in that community.

The translocation was conducted according to the guidelines of the Western Australian Animal Welfare Act 2002 (as approved by the Department of Biodiversity Conservation and Attractions Animal Ethics Committee, permit 2021-56C, with authorisation to take or disturb threatened species permit TFA 2019-0133), and fauna taking (scientific or other purposes) license FO25000190. Survey questions aligned with human research ethics guidelines to ensure the survey intent was understood by all participants; that informed consent was provided by all participants, and confidentiality and data protection of respondents was maintained when storing and presenting results.

Results

Western-practitioner perspectives

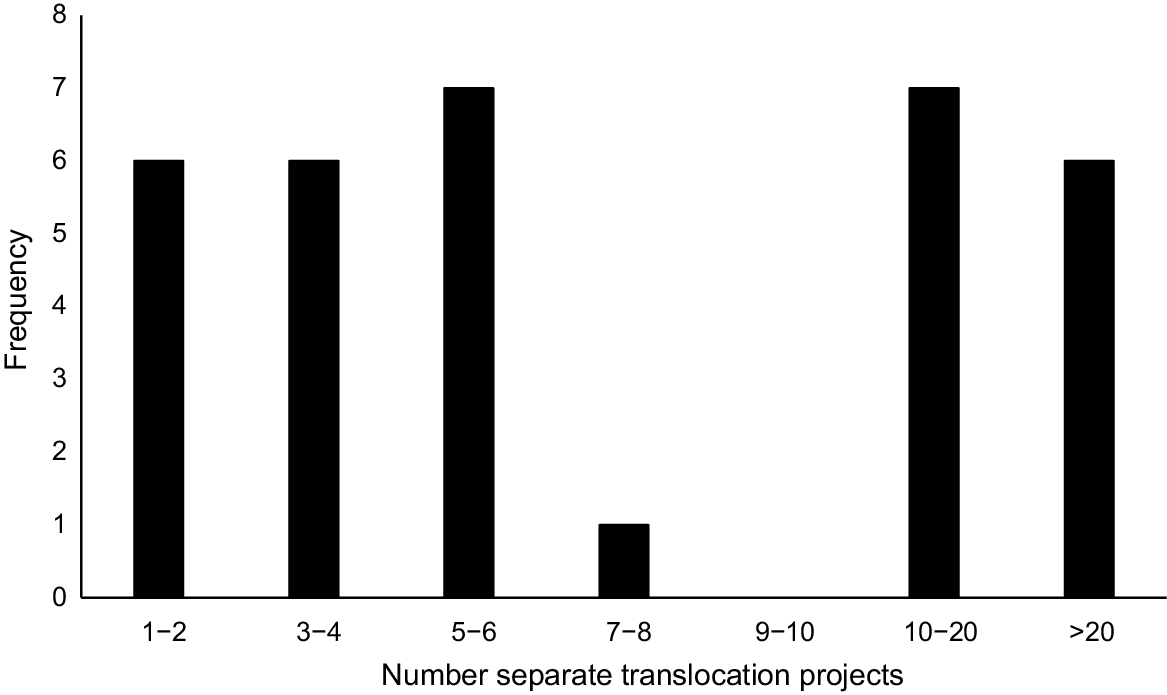

Thirty-three survey responses were received from western practitioners. Of these, most practitioners were involved in 1–6 translocations (>58% of responses) or >10 separate translocations (39%, Fig. 1).

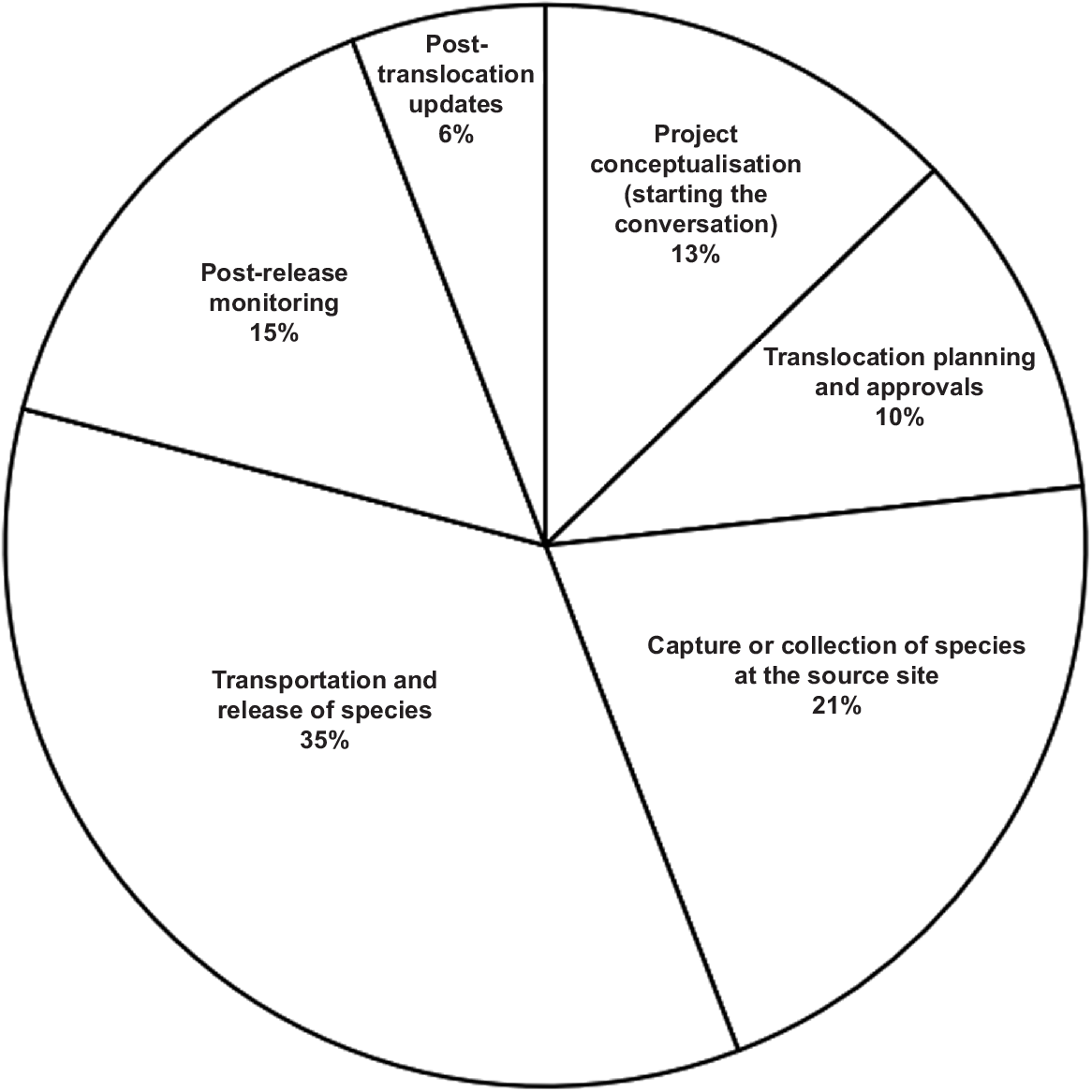

Frequency distribution illustrating the number of conservation translocations that western-practitioner respondents were involved with in Australia.

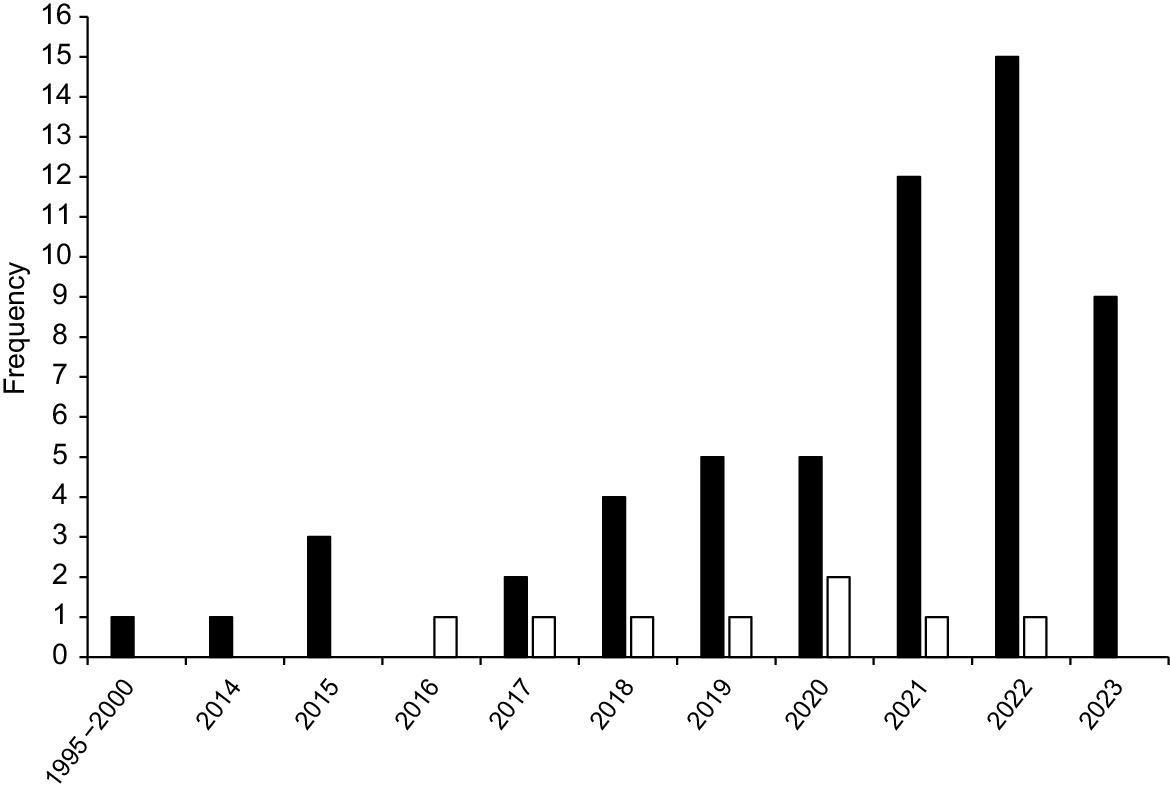

Responses reflected practitioner involvement in a total of 208 fauna and 8 flora conservation translocations (1995–2023). Of the fauna translocations, 27% had TO involvement, with the majority (>64%) conducted since 2001 (Fig. 2). Fewer flora conservation translocations were reported from survey responses, these were likely to be a reflection of a lower response rate to surveys than the actual number of translocations conducted. Nonetheless, only 12% of flora translocations had some level of TO involvement.

Number of flora (open bars) or fauna (closed bars) translocations in Australia from 1995 to 2023 (n = 65) where some level of Traditional Owner involvement was identified by western practitioners.

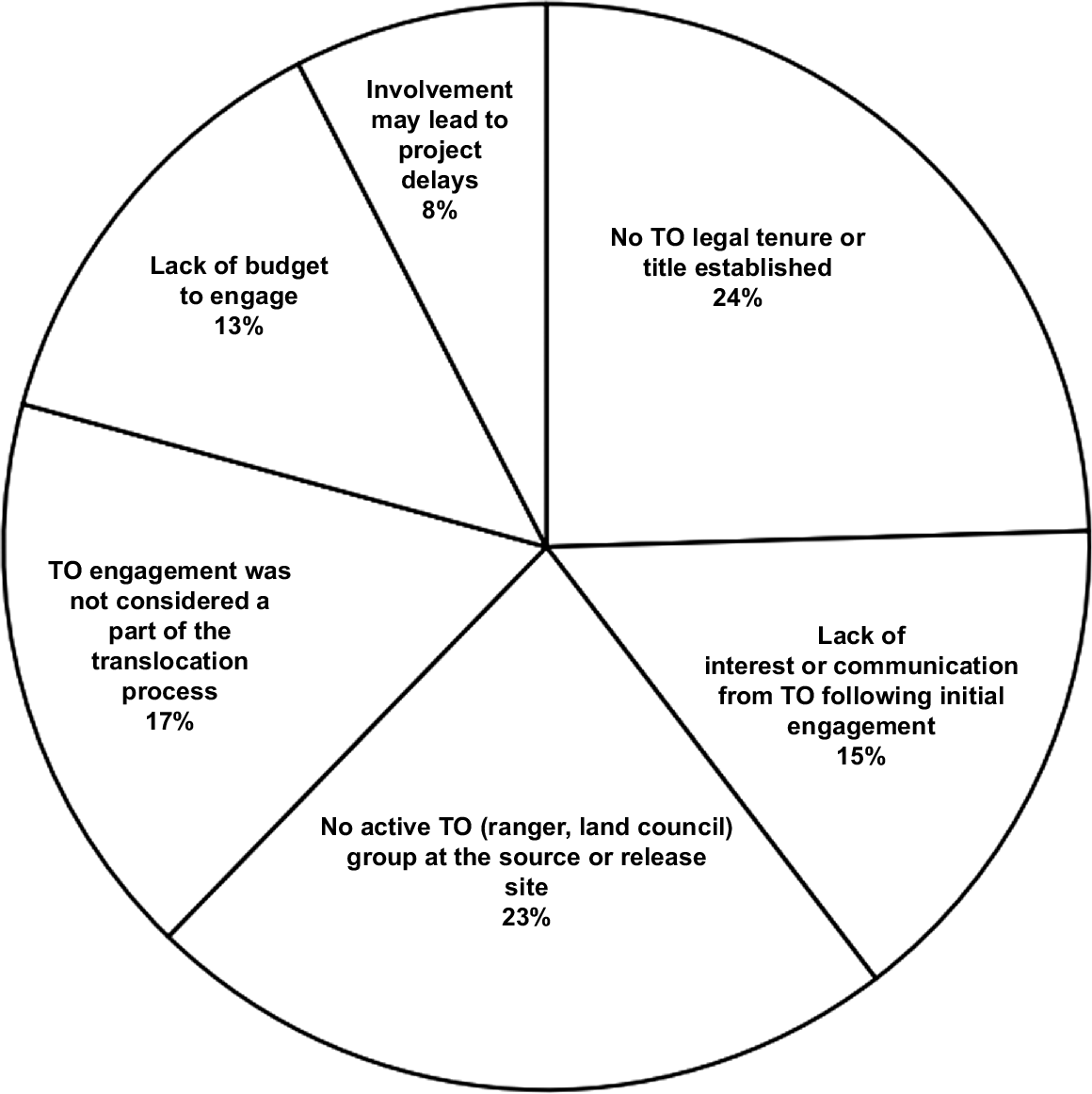

There was a diversity of reasons that western practitioners reflected on why TOs had not been engaged in past conservation translocations (Fig. 3); most perspectives related to an absence of western colonial structures (e.g. Native Title) for agencies and practitioners to engage with at source and release sites, or an absence of active TO groups (rangers, Land Council) to participate in the work conducted. Other reasons included lack of suitable budget to pay wages for TOs, lack of communications or (perceived) interest from TO organisations following initial contact, and the perceived delay that TO involvement could create to project schedules. Additional reasons (not illustrated) that precluded or limited TO involvement in conservation translocations included the following: translocation releases were considered experimental, releases were opportunistic and a requirement of imminent land clearing, or the harvest sites of animals were planned from locations that were culturally sensitive for TOs and so access was denied to western people and no further work was conducted in that area.

Frequency distribution comparing the reasons why Traditional Owners (TOs) were not considered to have been involved in past translocations (1995–2023).

Where TOs were involved in a conservation translocation, they were involved in some way with animal handling, transport or release (Fig. 4), such as removing animals from soft-release enclosures, transporting animals on their journey to release sites, releasing animals from their boxes or traps, pre- or post-harvest monitoring of animals at their source site, or post-release monitoring of animals at new sites. Various other levels of involvement of TOs were identified, including assistance with threat management (i.e. feral animal control), hosting ‘Welcome to Country’ for animals and people involved in the translocation, acting as on-site cultural advisors to translocation practitioners to ensure that significant sites were not disturbed during the monitoring phase of the work, media communications to express their views on the values of the translocation, and visitor awareness by conducting spotlight tours of released animals. Co-leading a translocation as part of an Indigenous Steering Committee, translocation planning and approvals discussions, and meeting attendances, were other ways TOs were engaged (Fig. 4).

What worked well?

From a western-practitioner perspective, there were six themes that reflected how TOs were actively engaged (Table 1).

Western-practitioner lens | What worked well |

| |

Challenges |

| ||

Areas for improvement |

| ||

Traditional-Owner lens | Why is the conservation translocation important? |

| |

How were you or your mob involved? |

| ||

How would you like to be involved next time? |

|

Hands-on tasks, such as trapping animals, releasing animals and operational tasks such as constructing fenced enclosures, were all considered to provide memorable group-bonding experiences forTOs and western practitioners.

Communication that reflected short video footage, photos of people working on Country, and face-to-face meeting updates including video-conferencing, were all considered to be well received by TOs.

Translocations that embedded cultural respect were considered valuable for TO involvement by western practitioners; exchanges of custodianship (Welcome to Country) between a TO at source and release sites supported Indigenous people to complete tasks that fulfilled and engaged their beliefs. For example, speaking to, and welcoming, animals in language, being able to share stories through dance and song. Interestingly, some respondents expressed concern about this theme, related to the tokenistic involvement of TOs either as individuals or as unskilled labour hire (see below).

Early Indigenous engagement and representation during the project development phase was considered the respectful level of inclusion with TO groups. Early representation was reflected as membership on Recovery Teams, authorship on documents or other project outputs such as Translocation Proposals or conferences, inclusion at project scoping meetings when deciding on objectives, and substantial face-to-face time on Country to discuss ideas with no formal agenda in place. Building respect and trust through relationships (below) was considered essential for successful Indigenous engagement. One practitioner stated ‘When TO have been engaged, no matter in what capacity, the outcomes have always been positive for both the project and the TO involved’.

Building long-term relationships, and using established relationships, as a platform for two-way (western and Indigenous knowledge) education to open communication barriers were viewed as valuable to a project’s engagement strategy. Some practitioners felt that regular updates of the science outputs with TO organisations through Indigenous rangers or their coordinators, led to bipartisan communication that reflected positively on the overall relationship between organisations. Many practitioners recognised that the value of a cultural ‘broker’, an intermediary person with an established relationship with the TO organisation and its Indigenous representatives, was a vital bridge to connect teams for meetings and to continue these relationships. In one example, this ‘broker’ was identified not as a person, but as a committee represented by the Joint Management Body of a National Park in WA. Allowing time to plan and execute a project, with realistic schedules at a pace that supports TOs to consider ideas, was also deemed important for building strong relationships.

Practitioners recognised the value of establishing learned cultural practices when they included TOs in their field work. Listening to TO perspectives of Country, including the cultural importance of some species, helped to shape the outcome of the conservation translocation for many scientists beyond species conservation, and to include the importance of healing Country from an Indigenous context. Working alongside scientists offered some TOs a wage, and therefore jobs and skills in animal capture and handling. The involvement of Indigenous youth from local schools, where this was achieved, supported the younger generations in communities to also gain educational ‘two-way science’ benefits from the translocation projects.

Challenges

Seven themes emerged that challenged the degree of engagement that respondents thought existed between western and TO individuals or organisations (Table 1).

Although good communication was identified by some responses to be of high value in translocation projects, it was also a common area where frustrations occurred. Requests by scientists to connect and meet with TO organisations were reported as unidirectional. Some practitioners suggested that these requests were more a requirement for a pre-defined action than an open request to meet (e.g. to conduct a smoking ceremony or a Welcome to Country at a release site), with a view that these actions were likely to represent the desires of the western community rather than a desire of the Indigenous land holders.

Likewise, time to build relationships, although noted as a strength for some translocations, was also a common theme to hinder TO engagement. Field logistics, including long hours of field work with western time-sensitive schedules, did not align to TO timeframes and work ethics, nor to funding and regulatory approval schedules. Some feedback recognised that even though time was spent to establish trust and build good working relationships, the translocations were rushed to involve TOs on the basis of western schedules.

Many practitioners regarded the involvement of TOs as cursory, involving TOs with no or limited skill training, and providing them with minor tasks in the field. In one example, TO involvement was identified in a project’s strategic plan; however, this equated to establishing an Indigenous trainee position only. Similarly, another project developed translocation proposals but no evidence was demonstrated that TOs were consulted in the process. Another project referred to TO involvement, but this translated only as their verbal consent for conducting the translocation of a species.

Many participants suggested their project planning required wider engagement among TO communities. Consultation that was limited to one individual spokesperson rather than a wider representation of TOs in community often led to disagreements about community representation, family-group tensions (who received work), and which ‘community or skin group’ would like to represent Country. Disputes over areas of release by some groups often stopped further TO involvement with the project.

Some respondents found that translocations that occurred within areas of Native Title determination, and with established Aboriginal ranger groups, had commenced with no formal strategy to engage TOs. As a result, engagement was viewed as ad hoc. One respondent suggested that a lack of an engagement strategy meant that the ‘buy-in’ from the local community was not as substantial as it could have been. Collectively, these minor engagements were described by some respondents as ‘missed opportunities’.

The inclusion of TO organisations in government contracts or proposals was identified by some respondents as cumbersome because of the expectations set by the process. One example was cited where animal-welfare legislation and fauna-research licences in Australia require names of all personnel who participate in translocation projects, including their skill levels when animal handling is proposed. TO individuals involved in these projects may know they will be permitted to be engaged, or be available, in the field work only just prior to the proposed field trip rather than weeks beforehand, as required by the permits and approvals process.

Respondents reported that some TO teams receive many requests to participate in science projects, field co-management, mining surveys, or other work on Country involving western people and agencies (e.g. heritage surveys for mining companies or pastoralists) with an interest to partner with TOs. This load amplifies the time commitments by TO organisations to handle, manage and operate TO teams, including TO ranger-led teams, because they do not have the resources to support and manage all of these on western time-sensitive schedules. Participants experienced a high turnover in personnel within TO groups; re-engaging conversations with different individuals at meetings about conservation translocations objectives, and their conservation and (if acknowledged) cultural outcomes, added to the time-pressure of project schedules. One respondent recognised that ‘High turnover suppresses skill development in individual TO, reduces built relationships between scientists and TOs, and therefore the team’s ability to communicate.’ A lack of consistent TO staff involved in translocation projects created difficulties around the ability to gain consistent engagement of individuals to allow suitable upskilling to the level required to permit them to undertake a greater role and responsibility in fauna work (constrained by Animal welfare and ethics, and scientific requirements): ‘If individual rangers engaged in fauna programs are constantly changing, no one gets enough time [or training] to increase their capacity’.

What could be improved?

Respondents identified six areas where TO engagement could be improved (Table 1).

Common feedback from respondents was that their organisation could have made more effort to involve TOs during the various stages of the translocation project, including project-planning and objective-setting. Expanding conversations from individual TO spokespeople to other members of the wider TO community would enhance the support for, and participation of, a planned project.

Most respondents recognised that there was limited funding available for translocation projects, and minimal to no funding to pay TO wages. Availability of funds to include TO wages would support wider engagement and job opportunities that are fair and equitable across members of the Indigenous project team.

How western practitioners or their agency representatives on working groups communicated with TOs was a common area for improvement. Talking or ‘yarning’ with the group face-to-face about conservation in general, learning and talking about the cultural importance of species, and the general nature of western interests to reduce the risks of species from extinction, would support TOs to learn about western interests, but also to empower them about the values of conducting conservation translocations. Practitioners recognised that many western scientists needed a better understanding of the connection of Indigenous people with plants and animals on Country that is best described as family, or as an extension of themselves as land custodians. In some instances, the species being translocated may be recognised culturally as a totem for a family or a broader skin group.

Establishing relationships, and taking the time to have conversations with Elders (community individuals, often elderly, recognised as the peak knowledge holders) was also an area considered to require more effort. Many respondents identified that Elders did not wish to immediately discuss the ‘mechanics’ of conducting a species translocation; instead, the positives and negatives of a project, including the context of their relationship with the animal, were viewed as more engaging initial discussion points. Questions such as: what does this species mean to them? Do they have any stories of this species occurring more widely? How would they feel if this species could be reintroduced to places where it used to live but now does not? Are there places that you would not move this species to? Would you like to be involved? Would you like to see your young fellas involved? How would you like to be involved? Some practitioners felt the project team needed to be personally directed by Elders in community as to whether (and how) community TOs should be involved in conversations related to translocations, and their subsequent work on Country.

Including TOs within the work staff development plan provides valuable opportunities to train them in project-specific skills such as animal-trapping, animal-handling and record-keeping. An appropriate level of basic training skills allows certain individuals with an interest and aptitude in fauna or flora work to have more regular involvement and the ability to take on a greater role in executing and planning fauna activities with western people. They could bring this knowledge and skill back into the TO community, and be able to assist in the training and capacity-building of other TOs over time. This skill-development mindset may help improve the retention of TO skills among an Indigenous workforce, and therefore support their future involvement in translocations.

Maintaining relationships between western and Indigenous teams was considered essential to improve the early dialogue for co-planned projects. Investing in a cultural broker to bridge the gaps between TOs and western practitioners, including navigating the bureaucracy of permit and approval needs, was identified as useful for supporting relationships given the often-tight timeframes to execute a project. Joint management bodies (for example, those established in Western Australia between TO organisations and the Western Australian Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions) offer one avenue for maintaining long-term relationships. By providing more opportunities for TOs as paid staff to be involved in the management of conservation estates, these co-managed relationships support ranger teams to build their capacity, and to remain employed in conservation and land-management projects.

Traditional-Owner surveys

I didn’t know why they [golden bandicoots] so special. But when we went to release them the Old Lady she was so happy to see this animal on her Country. [Wiluna Martu Ranger]

We received nine survey responses that reflected TO perspectives of fauna-related translocations. Surveys represented four separate Indigenous communities (three from WA, one from South Australia). TO respondents were involved in one, and up to three, separate fauna-translocation events.

When asked why the translocation was important to their community, the cultural significance of the species was a recognised aspect of returning them to their Country: ‘My mob haven’t seen bettongs in southern Yorke Peninsula in over 100 years’. One respondent initially queried ‘Why do they want to take our animals away?’ However, on being explained the importance of their (healthy) Country for the animals, they understood why other TOs want these animals on their Country too. The value of reintroducing animals for restoring healthy Country was a common theme in the feedback received; in relation to Matuwa Kurrara Kurrara Indigenous Protected Area, one respondent said: ‘I didn’t know why, then saw the importance of animals and how rare they are, how interesting. Good to know Matuwa is strong Country for them. Good to bring back to other Country’. Others saw the value of returning animals to Country for the next generation: ‘Moving them elsewhere … is good for Country and our children to help them see animals on Country’ and ‘I want us to have younger people involved in this work’. Collectively, participants all identified the importance of going out bush, and reconnecting with Country: ‘We go out bush. It takes all the negative things away. Gets us away from the worries of town. It is healing’. All TOs enjoyed their involvement in translocations and connections back to Country, including catching animals they have never seen before.

When asked about their type of involvement in translocations, many participated in the field program (trapping, monitoring) and with the collection of data. Some TOs were involved in the transport of animals from their Country to foreign Country well beyond their home: ‘Talking about [the translocation] early, working … recording information with science people, moving [animals] to other Country, releasing them’.

When asked how they would like to be involved in future conservation translocations, some TOs requested to improve their knowledge about the animals being translocated: ‘Have more hands-on learning about the animals’. One respondent wanted to be involved more in the ongoing monitoring of the released animals. Wages were mentioned albeit briefly; one TO recognised they were not paid to help release animals but ‘white people’ were paid a salary.

Case study: translocation of golden bandicoots from Matuwa Kurrara Kurrara Indigenous Protected Area (now also a National Park, WA) to Sturt National Park, NSW

We describe a case study to demonstrate a working relationship that was built between an Indigenous organisation (Tarlka Matuwa Piarku Aboriginal Corporation, TMPAC), a conservation-research body (Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions, DBCA) in WA, and an ecosystem restoration project (Wild Deserts, a collaboration between University of New South Wales, Ecological Horizons and the NSW Government Feral Predator Free Partnership Program) in NSW to undertake a translocation of a threatened marsupial (golden bandicoot, Isoodon auratus) from WA to NSW.

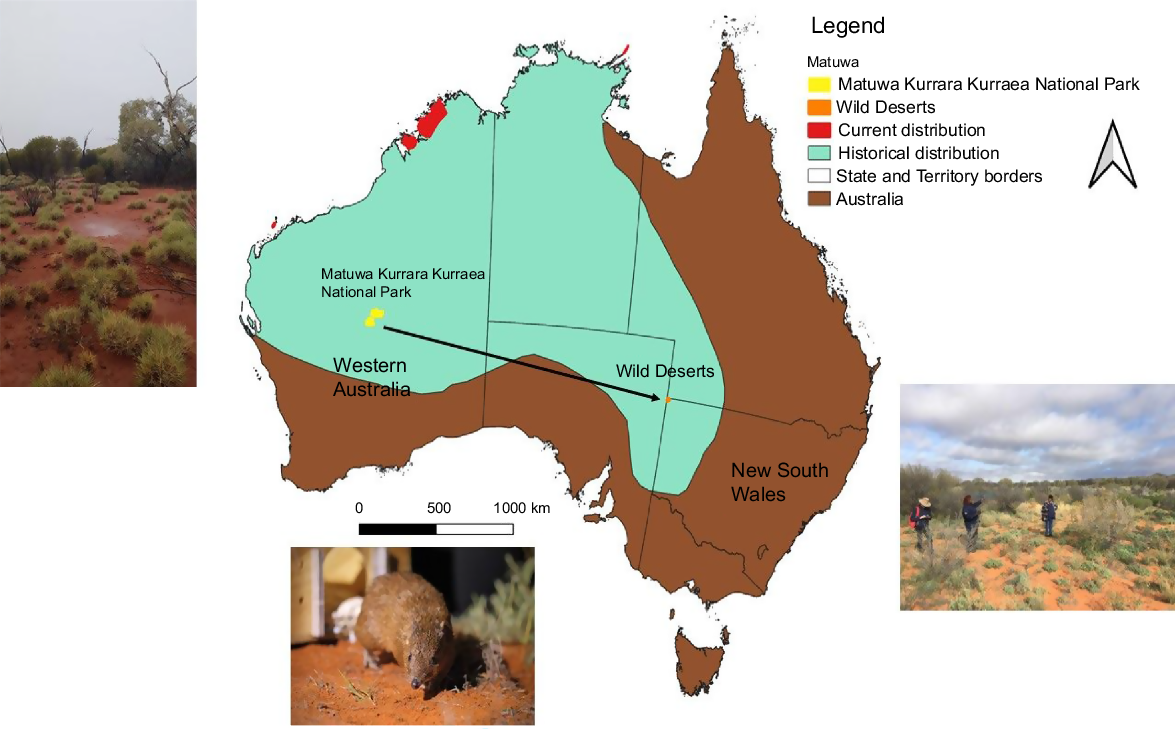

Golden bandicoots were once widespread across western, central and northern mainland Australia, but became extinct across >95% of their former range, primarily because of introduced predators, but likely also because of changes in vegetation structure related to extreme fire events and grazing livestock (Fig. 5). They remained extant on the mainland in the north-western Kimberley of WA and on offshore islands off the coast of WA. To assist the conservation of this species, translocations to offshore islands and fenced mainland reserves in WA were used to expand the distribution of the species (Ottewell et al. 2014). The first individuals were translocated back to the mainland in 2010, to an 11 km2 introduced predator-free fenced reserve on the Matuwa Kurrara Kurrara National Park (henceforth Matuwa) in the WA central desert. Matuwa is on Martu Country. Matuwa was identified as the top-ranking source population for the first translocation of golden bandicoots to NSW, to the Wild Deserts project in Sturt National Park (Pedler et al. 2018). The Wild Deserts project is on Wadigali land. Wongkumara and Maljangapa TOs, who hold Native Title in areas bordering the project area, have been involved with the project since its inception (Pedler et al. 2018). Despite Matuwa being 2000 km from the Wild Deserts release site, the Matuwa population was selected as the best source population for the golden bandicoot translocation to Wild Deserts because of the large population size (estimated 120 individuals in 2022, Lohr et al. 2021), high genetic diversity (Rick et al. 2023), and similar aridity to the Wild Deserts release site, which can assist diet and habitat selection following translocation.

Golden bandicoots (bottom image) were translocated from mixed spinifex (Triodia sp.) grasslands and mulga (Acacia aneura) shrublands on the Matuwa Kurrara Kurrara Indigenous Protected Area (more recently, National Park, WA) in Tarlka Matuwa Piarku Country to Sturt National Park in Wadigali Country (NSW). Historical distribution has been derived from Rick et al. (2023) and Warburton and Travouillon (2016) with permission. Current distribution for golden bandicoots is from IUCN Red List.

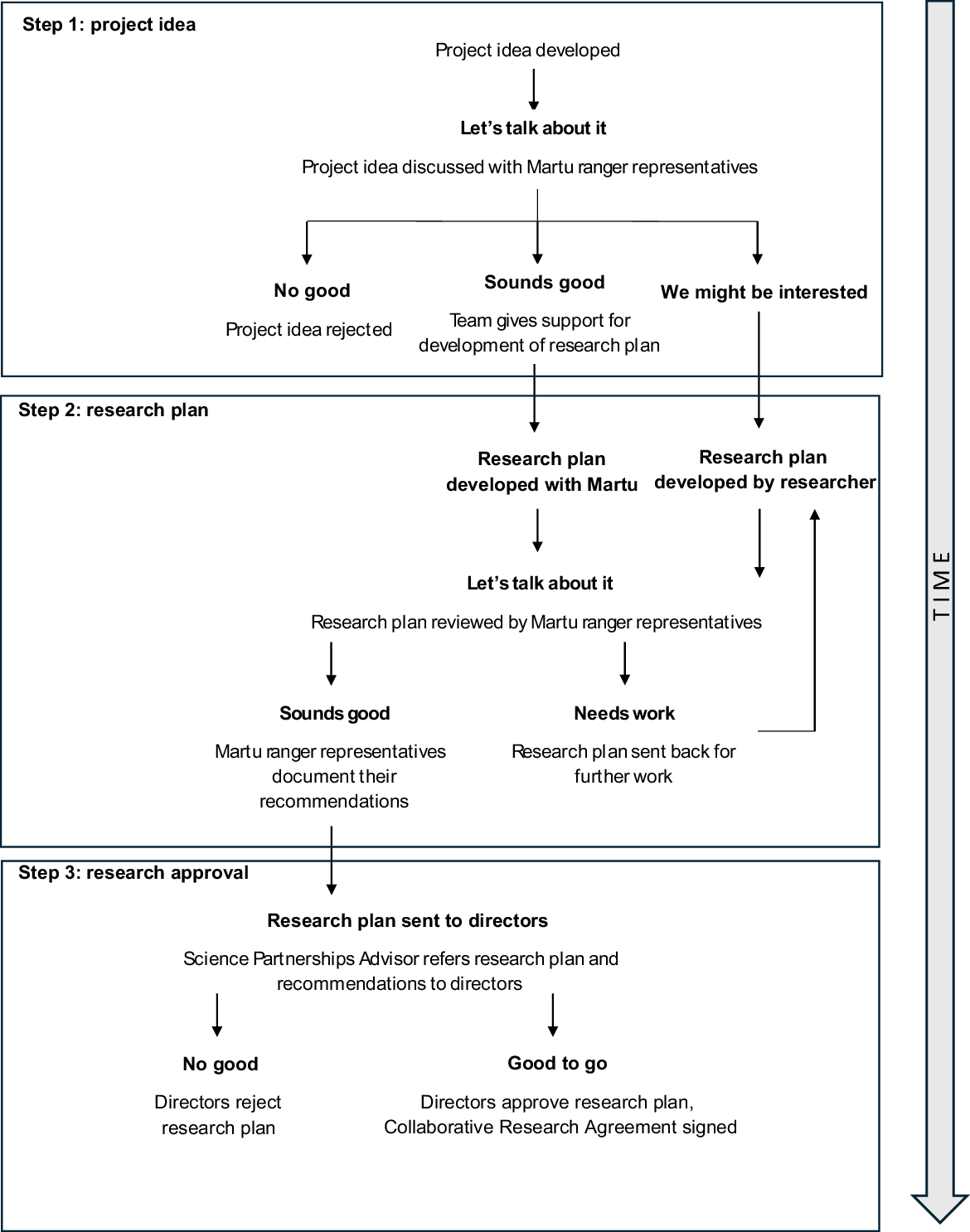

Guided by DBCA, Wild Deserts contacted TMPAC 8 months ahead of the proposed translocation date to initiate a Research Project Approval Process outlined in TMPAC’s Science Plan 2018–2023 (Tarlka Matuwa Piarku Aboriginal Corporation 2018, Fig. 6). TMPAC maintained an Indigenous Board of Directors to oversee conservation planning on Country within its Native Title determination. This Board was supported by an advisory group referred to as the IPA Management Team, which met quarterly to discuss land-management projects, including science-based projects. A TMPAC-employed facilitator who had established relationships with TO individuals, and the wider community, provided support for discussions between the IPA Management Team and external parties. On request of TMPAC, Wild Deserts submitted a synopsis of their research project with the full translocation proposal for consideration by the IPA Management Team. The IPA Management Team had no contemporary cultural connection to golden bandicoots but recognised their significance as part of a holistic healthy Country, which Matuwa represented. They had a desire to be involved, and respected the early request for their input as land custodians. The IPA Management Team conditionally approved the project, with the agreement that two of their Indigenous rangers would be involved with the translocation work at Matuwa, paid for their time and accompany the bandicoots to their release site at Wild Deserts. Additionally, the IPA Management Team requested that one Elder and one younger ranger must be involved to ensure that knowledge transfer was part of the Indigenous experience. A video-meeting was scheduled between the Martu rangers and Wild Deserts principal ecologist to discuss the translocation plans and provide an opportunity for the rangers to ask questions ahead of the trip. Wongkumara and Maljangapa representatives agreed that they would meet the Martu rangers at the Wild Deserts site to welcome them and the golden bandicoots as they arrived on their Country (Fig. 6).

Research project approval process that TMPAC used to assess proposals by scientists with project ideas on Matuwa Kurrara Kurrara Indigenous Protected Area.

The trapping event took place at Matuwa from 25 to 27 May 2022. Four Martu rangers were involved in the trapping, working with DBCA scientists. In total, 27 captured golden bandicoots were suitable for translocation. Martu rangers flew with the bandicoots to Wild Deserts, along with the Wild Deserts project coordinator. The golden bandicoots were successfully released to the Wild Deserts site after dark on 30 May 2022. Unfortunately, owing to an extreme rain event that made unsealed airstrips inaccessible and delayed the translocation by a few days, Wongkumara and Maljangapa representatives could not attend the bandicoot release. The Martu rangers released the bandicoots and then assisted in radio-tracking the bandicoots for the first day post-release, before returning home to WA. Post-release communication occurred through email and presentation updates from Wild Deserts ecologists to the Martu ranger team.

The key challenges overcome in this case study were maintaining open communications with a cultural facilitator that worked closely with the TO rangers, and whose role was to support the TOs in the field during the translocation event, early (8 month) lead-in time to plan and discuss this project with the cultural facilitator, flexibility in the program logisitcs to accommodate extreme weather events, and TOs accompanying animals to their release site.

Translocations are inherently expensive; the approximate costs associated with the golden bandicoot translocation to Wild Deserts was A$185,500 (Table 2). DBCA provided in-kind funds for the capture of golden bandicoots on Matuwa (A$45,000) by incorporating the translocation into their biannual threatened species monitoring program at the site. The charter flights to collect golden bandicoots from Matuwa and transfer them to Wild Deserts were A$22,000. Costs of the post-release monitoring (equipment, including radio-collars, camera-traps, cage traps, genetic analyses) was A$71,000, and A$15,000 was assigned for stakeholders to attend the release event (travel, accommodation and catering). In addition to this, five UNSW staff were involved in conducting the translocation, hosting the release event and the post-release monitoring, valued at ~A$12,000 salary. The cost of including Martu TOs in this translocation was A$18,000 (wages, return flights to Wiluna, accommodation). TMPAC supported with in-kind costs of A$2500. Therefore, ~11% of the total translocation budget reflected the inclusion of Martu rangers.

| Organisation | UNSW | DBCA | TMPAC | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-kind funding (A$) | 45,000 | 2500 | 47,500 | ||

| Direct financial funds (A$) | 138,000 | 138,000 | |||

| Total (A$) | 185,500 |

This case study has demonstrated one approach for engagement of TOs that worked well for all partners involved, leading to positive benefits for the conservation of the species, and the building of positive relationships between TOs and western scientists. All this work, with support from the TO organisation as a broker to Indigenous rangers, took just 8 months from the initial project request to animal release.

Discussion

We present the first review of TO engagement in conservation translocations in Australia, combining perspectives of both western practitioners and TOs. Currently, TOs are involved in approximately one-quarter of conservation translocations in Australia. Both TOs and western practitioners reported aspirations to increase these partnerships. The results showed a clear pattern of increasing engagement with TOs since 2001, suggesting encouraging trends of co-management in conservation projects. The national awareness across Australia of Indigenous people and their increased active participation in land-management roles and in politics across society may be one of several contributing factors to explain this improved participation. These conservation translocations remain an important mechanism for TOs to manage Country in partnership with government and other interested parties.

Fostering collaborations between TOs and western practitioners who have different values in conservation translocations remains challenging. Whereas western practitioners involved with wildlife conservation remain concerned for threatened species, these species may not necessarily be of value or concern for TOs where a species is very rare or of no spiritual significance to them (Garnett and Woinarski 2007). For example, golden bandicoots are of no cultural importance to the Wiluna Martu (and their local knowledge has been lost between Indigenous generations); however, their presence as part of healthy Country resonated more closely to the TOs than the level of threat that was of significance to western scientists. These cultural values, additional to the legal conservation values that western national policies adhere to, are worthy of including within the context of national assessments of biodiversity and ecosystem services (e.g. Brondizio et al. 2019).

Working cross-culturally in conservation requires a broad set of skills by western practitioners not just in the wildlife sciences, but in the social sciences. We identify the following three areas that western conservation managers should be cognisant of to reconcile western and Indigenous perspectives: strengths and values of working together, concerns and hope.

Strengths and values of working together

Themes that resonated from the surveys and our case study related to western practitioners respecting TOs for their participation in conservation translocations, sharing advice in terms of traditional ecological knowledge, and engaging key team members in the project design to build long-term relationships. When TOs came out to help with a translocation, sharing resources, sitting and sharing oral histories with Elders, and learning from their experiences were all local strengths that elsewhere have been founded on respect for cultural differences and values (Austin et al. 2017). Arguably, in practical terms, the most important cultural considerations needed are respect for the knowledge and practices of a culture, and the willingness to work within its context. Indigenous and non-Indigenous people have different, yet often complimentary knowledge and skills. Where both western and Indigenous organisations collaborated in the delivery of the translocation, this was acknowledged as a strength by both practitioners. We refer to this as the cultural dimension to conservation translocations where TOs are involved.

One of the strongest themes to emerge from the surveys was the value that western and Indigenous practitioners gained from the act of being on Country and spending time ‘out bush’ with each other. Mutual benefits included acquiring further knowledge and understanding skills relating to contemporary translocation techniques. This connection with Country has a strong emotional reference for TO. Working on Country allows time for teaching through sitting and yarning (Bessarab and Ng’andu 2010). Maintaining connections by visiting Country nurtures and sustains the cultural, social, emotional and mental wellbeing of TOs. These connections have been linked to improvements in the health of remote communities (Bessarab et al. 2018), and enduring partnerships with communities involved in conservation projects (Bryant and Copley 2018). Going out on Country remains integral to strengthening relationships between western practitioners and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, and generating two-way respect and education between western and Indigenous generations (Muller 2012).

Concerns

The surveys identified some concerns about the type of partnership and level of engagement with TOs. Some TO engagement was experienced as rushed or satisfying ‘tick-box’ requirements. A restricted level of integration of Indigenous conservation across a wider western management team was noted. Although a willingness to improve the engagement with TOs was expressed, the mechanism remained unclear. Attention to early engagement to foster and develop relationships with the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara TOs, and adopting TEK to understand the cultural connections of Anangu communities to black-footed rock-wallabies, was a key strategy for western scientists to develop their partnership with the TOs (Muhic et al. 2012). This early engagement offers one practical option for the practitioner to adopt.

TOs represent their families and community groups; so, involving individuals, while strengthening individual relations, becomes problematic when other family members feel that they are left out of conversations. Rayne et al. (2020) recognised the inclusion of family perspectives in New Zealand Maori are critical to community decision-making. This communal mindset reinforces the TO values of family and community decisions. Western practitioners should build relationships with TOs that encourages a more holistic mindset to include family groups and not just the individual. Ball et al. (2018) argued for a more holistic approach to conservation initiatives that integrate communities with their cultures, while recognising the commercial benefits of the program; we suggest the cultural dimension of conservation translocations is as valuable as commercial gain within the context of custodianship support in these conservation initiatives.

A concern raised by some TO participants in our survey was the issue of employment; a lack of local financial (TO wages) support was noted through both western and Indigenous lenses. Financial commitments to drive the involvement of Indigenous groups to share TEK, and to participate in conservation projects, is an issue that has been similarly reported in New Zealand (McLean et al. 2023). Employment of Indigenous people in conservation projects is known to reduce welfare dependency in Indigenous communities (Barber and Jackson 2017). Whereas minimal or no funding for TO support was identified by survey respondents, this stemmed more from a lack of budget planned a priori in projects rather than lack of desire to fund. As the most likely project instigators of conservation translocations, and usually those with the institutional funding for the project, the onus lies largely with research institutes and natural-resource management agencies to budget for the relevant TOs during the early stages of planning. In our case study, Indigenous involvement only made up a small percentage (11%) of the overall translocation budget. The lack of TO ownership of discussions and, on occasions, an incidental involvement of TOs as well as limited access to meaningful and reliable discussions may be managed through a reliable income stream built into budgets by both proponents and funding agencies.

In a related way, the itinerant nature of some TO members to participate across the duration of a project was noted as challenging by western practitioners, reflected typically by a casual ranger pool of people. A similar observation was noted by scientists in South Australia during black-footed rock-wallaby translocations (Muhic et al. 2012); Warru rangers would change between trips because the opportunity for casual employment competed with many other commitments and cultural responsibilities. Similarly, the remoteness of the field site meant that many potential female rangers were not able to work because of a lack of childcare facilities, resulting in a male-biased Warru ranger team. The mitigation adopted by project managers was to include flexibility in the employment of Warru rangers, with both permanent rangers and a large pool of casual rangers being supported to work (Muhic et al. 2012).

Hopes

Both western and TO practitioners expressed a keen desire to continue to work collaboratively, demonstrated both from survey feedback but also the case study (Wild Deserts contacted TMPAC well ahead of their planned translocation in the field). Western respondents wanted to build longer-lasting partnerships with TOs that reflected true collaborations. This was interpreted by many as improving the quality of translocation projects, and therefore the social dimension to the western people involved. As one respondent commented: ‘White people in attendance were able to see the importance and the impact that the rewilding and healing Country had on the Indigenous community in the area’. Similar social and wellbeing outcomes were identified in land-restoration programs in Zealandia in New Zealand where TOs (mana whenua) were provided with caretaker roles in the project (Michel et al. 2019).

TOs want to be included in all planning and decisions relating to their cultural, social and, when planning lengthy field work in remote areas, emotional wellbeing, and the development and co-design of programs involving culturally important fauna or flora. All aspirations that address the social and emotional wellbeing of TO communities must encompass practical short-term strategies as well as broader services delivered within the context of the translocation project.

As described in our case study, we reinforce that strong partnerships with TOs are essential if there are to be long-lasting relationships developed from projects on Native Title and jointly-managed tenures in Australia. In New Zealand, it is a legal requirement to involve local Maori with authority over land or territory to make decisions about treasured species, and their management (Michel et al. 2019). However, the full benefits of such a partnership are often overlooked, and the protocols applied have often failed to incorporate Maori culture in the creation of knowledge and in maintaining the relationship (Cisternas et al. 2019). In Australia, partnerships with TOs are delivering monetary benefits (Garnett et al. 2016). Our findings indicated that many of the concerns and types of engagement with TOs within the context of conservation translocations across Australia are inter-related. We suggest that strategies to address these issues must be multifaceted; building relationships takes time, and funding to pay Elders and other TOs for their time to discuss ideas and co-design projects needs to be budgeted for during the planned funding cycles of conservation translocations. Relationships become skewed when communications are broken, non-existent or staggered, and when expectations of government bureaucracy do not align with TO values or skill sets (Walker 2010). Partnerships that are supported by cultural relationships, that respect local TO culture, and that connect people on Country, have the potential to lead to longer-term and stronger relationships, positive cultural, social and emotional wellbeing outcomes, and positive conservation benefits (Muhic et al. 2012; McLeod et al. 2018). Our experience has shown that two-way land management can be greatly enhanced by the individuals and organisations who act in the capacity of cultural brokers between organisations (Baumann and Smyth 2007). According to Berkes (2009), facilitating the bridge between non-Indigenous and Indigenous organisations is a key factor in the success of community-based conservation. These cultural brokers remain an unassumed, yet vital, link to support enduring relationships between western and Indigenous agencies.

The ‘pillars of co-management’ may be viewed from an Indigenous lens to include learning-by-doing, the building of respect and rapport among groups, sorting out clear responsibilities, practical engagement in the absence of a time-bound schedule and capacity-building (Zurba et al. 2012). However, the activities relating to the conservation of threatened species should consider not only the Indigenous ecological knowledge of those species, but active relationships and engagements that build on co-management partnerships (Daniel et al. 2012; Leiper et al. 2018).

Recommendations for successful pathways to engage TOs in conservation translocations

Western practitioners expressed a willingness to improve their engagement with TO, but likewise expressed a lack of experience in how to initiate and continue these engagements. Similar sentiments have been expressed with Indigenous organisations that struggle to resource their engagement in bespoke initiatives by practitioners such as scientists (Hedge and Bessen 2019). It requires those working at the cultural interface to be respectful of cultural differences, cautious of their inherent assumptions and to question what and whose environmental philosophies, values and priorities are being considered at all stages.

We suggest that future practitioners who plan conservation translocations, and who seek to engage Indigenous people, e.g. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples particularly in Australia, should consider the following recommendations in co-management planning and discussions. Western practitioners should

encourage ‘on-Country planning’ and ‘participatory planning workshops’ because this encourages an understanding of the collective conservation goals for Country and conservation translocations;

include face-to-face collaboration to share experiences, skills and knowledge;

adopt flexible employment (casual and part-time) options for TOs to support their lifestyle requirements (attending funerals, cultural ceremonies, family commitments); and

combine their knowledge and skills with a two-way exchange of TOs cultural learning to enhance conservation translocation planning and outcomes.

Conclusions

Our recommendations lend some direction to a better integration of Indigenous practitioners into conservation translocations that western agencies support. The pathway for effective conservation partnerships with TO is to collaboratively develop practices respectfully co-developed with early Indigenous input. We refer to this practice as the ‘cultural dimension’ to conservation translocations and it should be considered an important ‘two-way interaction’ between western and Indigenous people on Country (Bradley 2001).

Engaging with TO groups, including Indigenous rangers, is an evolving process to respectfully integrate the western lens with the Indigenous lens, and where time and place become a separate dimension to an otherwise western mindset of schedules, budgets and milestones. Successful conservation translocations on Indigenous lands require support from the wider Indigenous community. We recommend that the western conservation manager’s portfolio should include a cultural toolkit that considers existing cultural protocols, such as early planning, early support, early discussions reflecting a willingness to include traditional ecological knowledge and oral histories in co-designing projects, and time to build relationships preferably through a TO ‘cultural broker’ who has previously built these relationships. Projects co-designed with local community members who remain engaged will see the best long-term relationships and lasting outcomes.

Declaration of funding

The Wild Deserts project is funded by the New South Wales Government Feral Predator Free Partnership Program, which covered Dr West’s role and all project expenses for this translocation. The monitoring event at Matuwa was supported by the Chevron Gorgon Barrow Island Threatened and Priority Species Translocation Program through the Western Australian Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions. The funders had no involvement in the preparation of the data or paper or the decision to submit for publication. TMPAC’s contribution was supported by the NIAA-funded Indigenous Protected Area Program for Matuwa Kurrara Kurrara.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge and respect the Wiluna Martu represented by the Tarlka Matuwa Piarku Aboriginal Corporation in Western Australia, the Wongkumara and Maljangapa in New South Wales, and other Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, as Traditional Owners of their lands, and thank them for their stewardship of Country. We pay our respect to their culture, and their Elders past, present and emerging. The authors thank the partnerships developed between the Wiluna Martu Rangers of the Wiluna determination (WA), Wild Deserts, and DBCA (Biodiversity Conservation Science). We thank Katherine Moseby and Katherine Tuft for early discussions to scope the survey questions, and we thank survey participants (western and TOs) for their honest feedback and perspectives, and support for future projects that improve partnerships with TOs. Additionally, the integrity of TOs was recognised by having Ranger Coordinators with close working relationships to TOs respectfully and verbally explain the purpose of the survey and acknowledge informed consent if given.

References

Abecasis RC, Schmidt L, Longnecker N, Clifton J (2013) Implications of community and stakeholder perceptions of the marine environment and its conservation for MPA management in a small Azorean island. Ocean & Coastal Management 84, 208-219.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Armstrong DP, Moro D, Hayward MW, Seddon PJ (2015) Introduction: the development of reintroduction biology in New Zealand and Australia. In ‘Advances in reintroduction biology of Australian and New Zealand Fauna’. (Eds DP Armstrong, MW Hayward, D Moro, PJ Seddon) pp. 1–6. (CSIRO Publishing: Melbourne, Vic., Australia)

Austin BJ, Vigilante T, Cowell S, Dutton IM, Djanghara D, Mangolomara S, Puermora B, Bundamurra A, Clement Z (2017) The Uunguu monitoring and evaluation committee: intercultural governance of a land and sea management programme in the Kimberley, Australia. Ecological Management & Restoration 18, 124-133.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Barber M, Jackson S (2017) Identifying and categorizing cobenefits in state-supported Australian indigenous environmental management programs: international research implications. Ecology and Society 22, 11.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Bennett NJ, Dearden P (2014) Why local people do not support conservation: community perceptions of marine protected area livelihood impacts, governance and management in Thailand. Marine Policy 44, 107-116.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Bennett NJ, Di Franco A, Calo A, Nethery E, Niccolini F, Milazzo M, Guidetti P (2019) Local support for conservation is associated with perceptions of good governance, social impacts, and ecological effectiveness. Conservation Letters 12, e12640.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Berkes F (2009) Evolution of co-management: role of knowledge generation, bridging organizations and social learning. Journal of Environmental Management 90, 1692-1702.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Berkes F, Colding J, Folke C (2000) Rediscovery of traditional ecological knowledge as adaptive management. Ecological Applications 10, 1251-1262.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Bessarab D, Ng’andu B (2010) Yarning about yarning as a legitimate method in indigenous research. International Journal of Critical Indigenous Studies 3, 37-50.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Beyerl K, Putz O, Breckwoldt A (2016) The role of perceptions for community-based marine resource management. Frontiers in Marine Science 3, 238.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Bradley J (2001) Landscapes of the mind, landscapes of the spirit: negotiating a sentient landscape. In ‘Working on country: contemporary indigenous management of Australia’s Lands and Coastal Regions’. (Eds R Baker, J Davies, E Young) pp. 295–308. (Oxford University Press: Melbourne, Vic., Australia)

Brondizio ES, Settele J, Díaz S, Ngo HT (Eds) (2019) ‘Global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science–Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services.’ (IPBES Secretariat: Bonn, Germany) doi:10.5281/zenodo.3831673

Cisternas J, Wehi PM, Haupokia N, Hughes F, Hughes M, Germano JM, Longnecker N, Bishop PJ (2019) ‘Get together, work together, write together’: a novel framework for conservation of New Zealand frogs. New Zealand Journal of Ecology 43, 3392.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Daniel TC, Muhar A, Arnberger A, Aznar O, Boyd JW, Chan KMA, Costanza R, Elmqvist T, Flint CG, Gobster PH, Grêt-Regamey A, Lave R, Muhar S, Penker M, Ribe RG, Schauppenlehner T, Sikor T, Soloviy I, Spierenburg M, Taczanowska K, Tam J, von der Dunk A (2012) Contributions of cultural services to the ecosystem services agenda. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 109, 8812-8819.

| Google Scholar |

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (2022) Threatened species strategy action plan 2022–2032. (DCCEEW: Canberra, ACT, Australia) Available at https://www.dcceew.gov.au/environment/biodiversity/threatened/action-plan [Verified March 2023]

Fabre P, Bambridge T, Claudet J, Sterling E, Mawyer A (2021) Contemporary Rāhui: placing Indigenous, conservation, and sustainability sciences in community-led conservation. Pacific Conservation Biology 27, 451-463.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hedge P, Bessen B (Eds) (2019) AMSA Indigenous Workshop: summary report – promoting collaborative partnerships for sea country research and monitoring in Western Australia. Report from Workshop Organising Committee to the Australian Marine Sciences Association and the National Environmental Science Program. Marine Biodiversity Hub, AMSA Indigenous Workshop Organising Committee.

Hill R, Davies J, Bohnet IC, Robinson CJ, Maclean K, Pert PL (2015) Collaboration mobilises institutions with scale-dependent comparative advantage in landscape-scale biodiversity conservation. Environmental Science & Policy 51, 267-277.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Jefferson RL, Bailey I, Laffoley DA, Richards JP, Attrill MJ (2014) Public perceptions of the UK marine environment. Marine Policy 43, 327-337.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Kitson JC, Cain AM, Johnstone MNTH, Anglem R, Davis J, Grey M, Kaio A, Blair S-R, Whaanga D (2018) Nurihiku cultural water classification system: enduring partnerships between people, disciplines and knowledge systems. New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research 52, 511-525.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Leiper I, Zander KK, Robinson CJ, Carwadine J, Moggridge BJ, Garnett ST (2018) Quantifying current and potential contributions of Australian indigenous peoples to threatened species management. Conservation Biology 32, 1038-1047.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Lohr CA, Nilsson K, Sims C, Dunlop J, Lohr MT (2021) Habitat selection by vulnerable golden bandicoots in the arid zone. Ecology and Evolution 11, 10644-10658.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

McLean M, Warner B, Markham R, Fischer M, Walker J, Klein C, Hoeberechts M, Dunn DC (2023) Connecting conservation & culture: the importance of Indigenous Knowledge in conservation decision-making and resource management of migratory marine species. Marine Policy 155, 105582.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

McLeod I, Schmider J, Creighton C, Gillies C (2018) Seven pearls of wisdom: advice from Traditional Owners to improve engagement of local Indigenous people in shellfish ecosystem restoration. Ecological Management & Restoration 19, 98-101.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Michel P, Dobson-Waitere A, Hohaia H, McEwan A, Shanahan DF (2019) The reconnection between mana whenua and urban freshwaters to restore the mouri/life force of the Kaiwharawhara. New Zealand Journal of Ecology 43, 3390.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Muhic J, Abbott E, Ward MJ (2012) The warru (Petrogale lateralis MacDonnell Ranges Race) reintroduction project on the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Lands, South Australia. Ecological Management & Restoration 13, 89-92.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ottewell K, Dunlop J, Thomas N, Morris K, Coates D, Byrne M (2014) Evaluating success of translocations in maintaining genetic diversity in a threatened mammal. Biological Conservation 171, 209-219.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Parker KA (2008) Translocations: providing outcomes for wildlife, resource managers, scientists, and the human community. Restoration Ecology 16, 204-209.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Pedler RD, West RS, Read JL, Moseby KE, Letnic M, Keith DA, Ryall SR, Kingsford RT (2018) Conservation challenges and benefits of multispecies reintroductions to a national park–a case study from New South Wales, Australia. Pacific Conservation Biology 24, 397-408.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ramos SC (2018) Considerations for culturally sensitive traditional ecological knowledge research in wildlife conservation. Wildlife Society Bulletin 42, 358-365.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Rayne A, Byrnes G, Collier-Robinson LNT, Hollows J, McIntosh A, Ramsden M, Rupene M, Tamati-Elliffe P, Thoms C, Steeves T (2020) Centring Indigenous knowledge systems to re-imagine conservation translocations. People and Nature 2, 512-526.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Renwick AR, Robinson CJ, Garnett ST, Leiper I, Possingham HP, Carwardine J (2017) Mapping Indigenous land management for threatened species conservation: an Australian case-study. PLoS ONE 12, e0173876.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Rick K, Byrne M, Cameron S, Cooper SJB, Dunlop J, Hill B, Lohr C, Mitchell NJ, Moritz C, Travouillon KJ, von Takach B, Ottewell K (2023) Population genomic diversity and structure in the golden bandicoot: a history of isolation, extirpation, and conservation. Heredity 131, 374-386.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Schley HL, West IF, Williams CK (2022) Advancing wildlife policy of eastern timber wolves and lake sturgeon through traditional ecological knowledge. Sustainability 14, 3859.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Warburton NM, Travouillon KJ (2016) The biology and palaeontology of the Peramelemorphia: a review of current knowledge and future research directions. Australian Journal of Zoology 64, 151-181.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Whyte KP (2013) On the role of traditional ecological knowledge as a collaborative concept: a philosophical study. Ecological Processes 2, 7.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Woodward E, Hill R, Harkness P, Archer R (Eds) (2020) ‘Our knowledge our way in caring for country: Indigenous-led approaches to strengthening and sharing our knowledge for land and sea management. Best practice guidelines from Australian experiences.’ (NAILSMA and CSIRO: Cairns, Qld, Australia) doi:10.25607/OBP-1565

Zurba M, Ross H, Izurieta A, Rist P, Bock E, Berkes F (2012) Building co-management as a process: problem solving through partnerships in Aboriginal country, Australia. Environmental Management 49, 1130-1142.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |