Cascade of testing for chlamydia and gonorrhoea inclusive of an annual health check in an urban Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Service

Condy Canuto A * , Judith A. Dean

A * , Judith A. Dean  B , Joseph Debattista C , Jon Willis D , Federica Barzi B , Jonathan Leitch E and James Ward B

B , Joseph Debattista C , Jon Willis D , Federica Barzi B , Jonathan Leitch E and James Ward B

A

B

C

D

E

Abstract

To gain an understanding of chlamydia (CT) and gonorrhoea (NG) testing conducted within an annual health check (AHC) and in standard clinical consultations for clients aged 15–29 years attending an urban Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Service in the period 2016–2021.

De-identified electronic medical record data were extracted and analysed on CT and NG testing by sex, age, Indigenous status and the context of testing (conducted within an AHC or not). An access, testing, and diagnosis cascade for CT and NG, inclusive of an AHC, was constructed.

Combined testing within an AHC and outside an AHC for CT and NG ranged between 30 and 50%, except for the year 2021. Males were twice as likely to receive a CT and NG test within an AHC consultation as females. Females were almost equally likely to have a CT and NG test, both as part of an AHC consult and during other clinical consultations. Females had the highest CT positivity in 2018 (11%) and 2019 (11%), with a dip in 2020 (5%), whereas NG diagnoses remained stable at 2%.

The study demonstrates the potential of the AHC to facilitate greater coverage of CT and NG testing in an urban Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Service. Screening conducted within an AHC alongside screening in clinical consultations might be enough to reduce CT prevalence over a sustained period.

Keywords: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, Aboriginal medical service, annual health check, cultural determinants, MBS715, sexual health, urban Aboriginal health, urban sexually transmissible infections.

Introduction

Primary healthcare services play a crucial role in the prevention and management of sexually transmitted infections (STI) among young people, especially within Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples communities.1–3 Throughout this paper, the terms ‘Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander’ and ‘Indigenous’ are used interchangeably to specifically refer to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples of Australia, unless otherwise stated. Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services (ACCHS) are important providers of primary health care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, and often are the first point of contact for Indigenous people seeking health care. Therefore, ACCHS play a pivotal role in the control of STIs by offering STI prevention strategies, such as planned and opportunistic sexual health testing among clients. The importance of ACCHS is further highlighted by young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples having reported ACCHS as preferred providers of care, including for STI testing.4,5

The high notification rates of STIs among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people aged 16–29 years in Australia represent a significant public health concern. In 2022, the national notification rate for CT and NG was more than double and five times, respectively, that of their non-Indigenous counterparts.6 The prevalence of CT and NG among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples living in capital cities is a complex issue due to underreporting and lack of data disaggregation. Despite gaps in the reporting of CT and NG notifications by Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander status, diagnosis rates are significantly higher among Indigenous people compared with non-Indigenous Australians in several Australian capital cities where data are available.7 In 2021, the majority of CT (79%) and NG (66%) diagnoses in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples population occurred in the 15–29 years age group.7 In the same age group, males were diagnosed with CT and NG at a rate almost 40% less than females, most likely reflecting greater access to primary health care for young women than men.7

Due to their asymptomatic nature, especially in women, CT and NG infections are often not recognised and, therefore, untreated.8 Untreated infections can result in significant morbidities, such as pelvic inflammatory disease, ectopic pregnancy, disseminated infection, increased risk of infertility and HIV acquisition.9 Early detection of STIs through regular testing is a clinical and public health strategy2 to reduce sequalae and prevent onward transmission.3

An essential component of the ACCHSs healthcare delivery model is the annual health check (AHC).10,11 It was introduced in 200412 under Medicare, Australia’s national health insurance scheme that provides free or subsidised health care for Australians. The conduct of the AHC attracts a rebate for health services under the Medicare Benefits Schedule item number 715, and can be conducted once in a 9-month period. It assesses the health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples12,13 and is seen as a valuable tool for the early detection of chronic diseases by screening for a range of issues, including physical health, mental health, lifestyle factors and social determinants of health.11 The AHC also includes recommendations for sexual health screening, including testing for CT and NG.1

Little is known about STI testing within the context of AHCs, particularly within an urban setting. This study seeks to assess CT and NG screening among clients aged 15–29 years attending an urban ACCHS both within the AHC and during other clinical consultations for the period 2016–2021.

Methods

Study site

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Community Health Service (ATSICHS) Brisbane is a not-for-profit community-controlled health and human services organisation that has been providing holistic care to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples of greater Brisbane since its founding in 1973.14 The service includes a range of preventative, curative and promotive healthcare services, as well as community development programs, provided across five clinical sites. A key component of the service is the provision of AHCs for all eligible clients.

Data collection

An in-depth analysis was conducted of routinely collected EMR data collected between 2016 and 2021. Utilising a retrospective longitudinal and population-based methodology, it focused specifically on individuals aged 15–29 years who attended clinical consultations, including those participating in an AHC during this period.

Data were drawn from the ATLAS network,15 which currently involves 35 ACCHS in urban, regional and remote areas. Utilising data from the ATLAS database, de-identified records of all consults and AHC assessments conducted in clients aged 15–29 years at ATSICHS Brisbane were accessed and analysed. Other data extracted included sex, Indigenous status, consultation date, CT and NG tests, and results. All AHC data were taken from the Progress Note_Reason field and were coded as: 1 = AHC, or 0 = no evidence of AHC. As CT/NG are tested simultaneously within the one assay as a combined test,16 completion of a CT test was used as an indicator of NG testing.

Statistical analysis

From the period 2016 to 2021, the proportion of all clients aged 15–29 years who had an AHC was calculated, and stratified by age, sex and other demographic factors, including Indigenous status. The number and proportion of clients aged 15–29 years who had an AHC and were tested for CT/NG was calculated, as well as positivity of these tests. Data were stratified by demographic factors. The same analysis was then conducted on clients who did not receive an AHC (tested for CT/NG outside of the AHC), with the results of each group then compared. Data were analysed using SPSS 28 statistical software (IBM SPSS Statistics).

Cascades of care are used to demonstrate where strengths and gaps in the system may exist as potential points of intervention.17 Using all analysed data, an access, testing and diagnosis cascade of care for CT/NG, including the AHC-specific to ATSICHS Brisbane, was constructed. The care cascade focused on male and female clients aged 15–29 years. It calculated the number and percentage of individuals who underwent an AHC out of the total number of clients attending the service each year from 2016 to 2021. Among those who had an AHC, we calculated the proportion who had a CT/NG test, and among those tested, the proportion positive for either CT or NG. Time trends of testing rates and positivity rates over the period 2016 to 2021 were explored using mixed effects generalised linear models with a random intercept to allow for correlation of repeat testing and positivity over time, and a continuous variable for year to test linearity of time trends.

Overall ethics was applied for by the ATLAS team, and consent was requested to the ATLAS governance group for this analysis to occur. Ethics was also approved by the University of Queensland Human Research Ethics Committee (#2020/HE002735). Data sovereignty and the protection of Indigenous rights in research were central to this study, ensuring a framework of ethical conduct and respect for Indigenous data governance.18,19

Results

During the 6-year period from 2016 to 2021, 37% of all AHC conducted at the study site (n = 7494) were conducted in the 15–29 years age group. Among the AHC conducted within this age range, 36% (n = 2697) were conducted among clients aged 15–19 years, 32% (n = 2414) among those aged 20–24 years and 32% (n = 2383) were conducted among clients aged 25–29 years. Females represented 57% (n = 4288) of all AHCs in the 15–29 years age group.

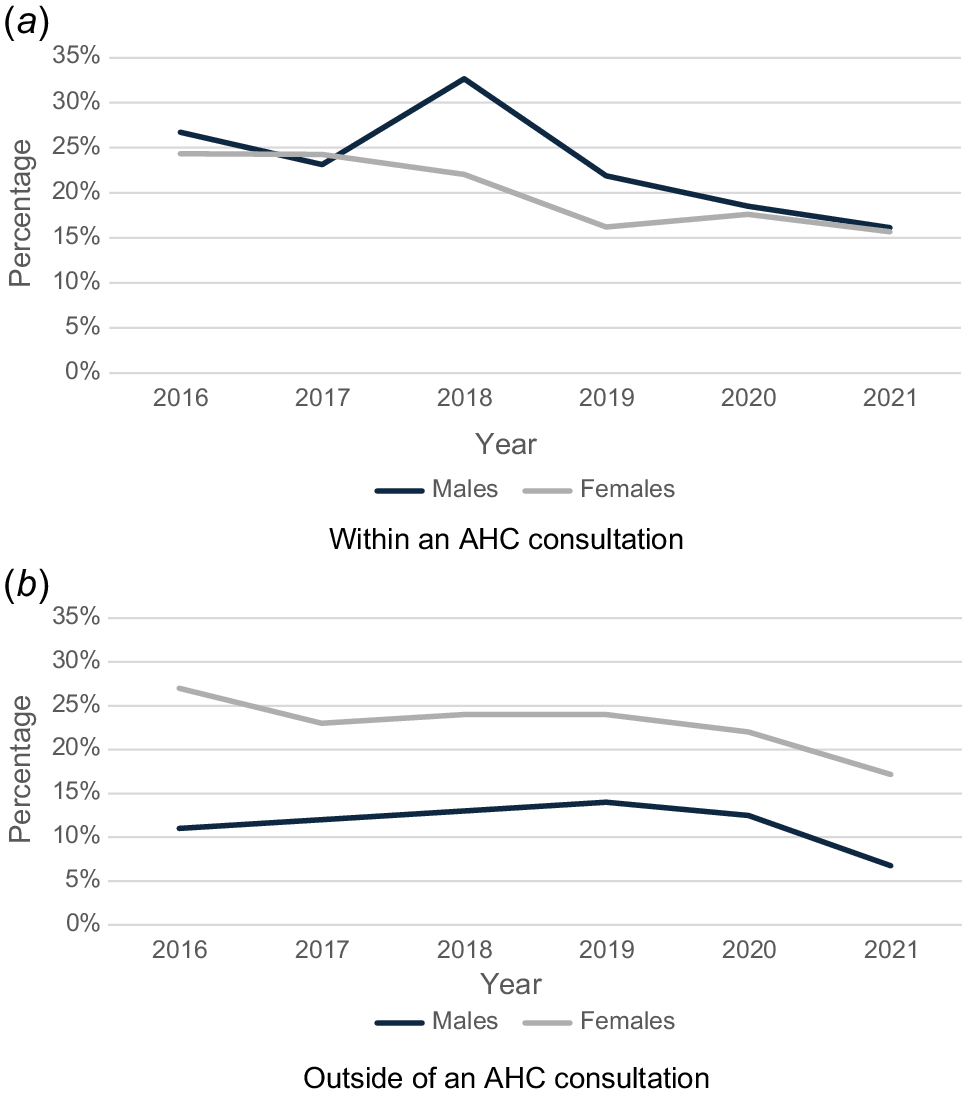

Fig. 1a, b show CT/NG testing among people aged 15–29 years by sex, both within an AHC and outside an AHC consultation. Males were tested for CT/NG at almost twice the rate during an AHC consultation compared with outside of the AHC, with 23 and 12% being tested within and outside of the AHC, respectively. Females had similar testing proportions both within and outside of an AHC, with 20 and 23%, respectively. Overall, there was a decrease in the number of males and females being tested for CT/NG within the AHC over the study period (P < 0.001 for both males and females).

Proportion of eligible clients tested for chlamydia and gonorrhoea within a (a) AHC consultation and (b) outside of an AHC by sex for the 15–29 years age group at ATSICHS Brisbane 2016–2021.

Within the CT/NG testing for the 15–29 years age group conducted outside the AHC, females were tested at almost twice the rate of males. Males who had an AHC were twice as likely to have had a CT/NG test than those who had attended for other clinical care within a regular clinic visit. From 2016 to 2019, the trend remained consistent for females, whereas it showed a significant increase for males (P < 0.001). After 2019, both males and females experienced a decrease.

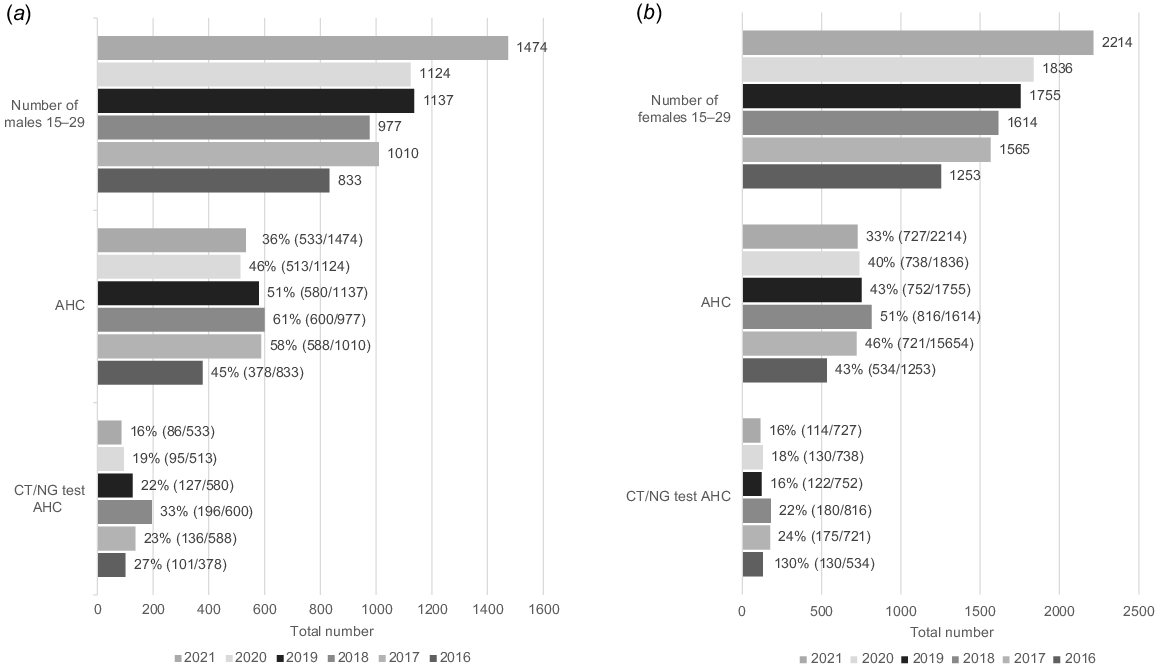

Fig. 2a, b show the CT/NG testing and diagnosis cascade for males and females aged 15–29-years who received an AHC between 2016 and 2021, respectively. The highest percentage of AHCs conducted in males aged 15–29 years was in 2018, at 61% of all attendees compared with 36% in 2021. Females receiving an AHC followed the downward trend with 51% in 2018 and 33% in 2021.

(a) Chlamydia and gonorrhoea testing cascade for males aged 15–29 years within the AHC for ATSICHS Brisbane 2016–2021, (b) chlamydia and gonorrhoea testing cascade for females aged 15–29 years within the AHC for ATSICHS Brisbane 2016–2021.

The results also show within the cascade for both males and females that approximately one-quarter to one-third of eligible males and females had a STI test within an AHC consultation. For males, the highest percentage of CT/NG testing conducted within the AHC was in 2018, with 33% compared with 16% in 2021. For females, the highest percentage of CT/NG testing conducted within the AHC was in 2017, with 24% compared with 16% in 2021 (P < 0.001).

Of the males who had a CT/NG test within the AHC, 12% were diagnosed with CT in 2017, and 6% in 2018. From 2019 to 2021, there was a 9% positivity rate. For females, the highest diagnosed rate was found in both 2018 and 2019 at 11%, and the lowest rate in 2020 at 5%. Between 2016 to 2021, the percentage of females diagnosed with NG remained stable at 2%. However, during that same period, males peaked at 7% in 2016, but then had no recorded cases from 2020 to 2021.

Over the study period, the rate of CT diagnoses outside of the AHC showed a decline (P < 0.029 males, P < 0.013 females). For males, the rate decreased from 17% in 2016 to 5% in 2020, then back up to 7% in 2021. For females, the decrease was from 13% in 2017 to 7% in 2021. Similarly, the rates of NG diagnoses outside of the AHC for males dropped from 5% in 2016 to 1% in 2020, whereas for females, the rates went from 4% in 2016 to 1% in 2018. However, due to the small numbers of positive diagnoses, these differences were not statistically significant (P = 0.275 for males and P = 0.92 for females).

Discussion

This analysis describes the relationship between CT/NG testing and the AHC among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people within an urban ACCHS. The national guidelines advocate for annual CT/NG testing for all individuals aged 15–29 years.20 The cascade of testing showed that of the males and females within the 15–29 years age group who had an AHC, approximately one-quarter underwent STI testing within the AHC. A recent study by McCormack et al.1 examining STI testing within the AHC across the 35 ACCHS in the ATLAS Network showed similar overall testing rates, with a STI test integrated within 23.9% of AHC.21

National data have shown that the uptake of AHC increases with age.11 In 2023, 28% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples (257,000) had an AHC.22 The rates of Indigenous-specific health checks were highest for those aged ≥65 years, for both males and females. The lowest was for those aged 5–14 years for females, and aged 15–24 years and 25–34 years for males. Across age groups, the difference between males and females in the rate of AHC was largest for those aged 25–34 years (28% of Indigenous females, compared with 18% of Indigenous males).22 These lowrates of participation in the AHC by those age groups most affected by CT/NG suggests the need for significant work to promote the AHC as an opportunity for STI testing, both among young people and those healthcare providers delivering the AHC, as well as the need to facilitate other testing opportunities during consultations beyond the AHC.

Significantly, although the rates of STI testing within the AHC of young people ranged between one-fifth and one-quarter of clients, these rates should be viewed in combination with comparative rates of testing outside of the AHC. Cumulative testing rates in most years prior to 2019 reached levels of 40–50% of all young people accessing the health service, attaining rates that modelling has suggested could be effective at reducing overall community prevalence of CT and NG.23

Our results suggest that both the AHC and consultations outside of the AHC should be utilised as complementary pathways for testing, each showing unique sex-based advantages. This was demonstrated by the difference in testing rates by sex over our 6-year study period, with approximately 25% of males compared with 20% of females in the 15–29 years age group undertaking a CT/NG test within their AHC. Interestingly, outside of an AHC consultation, 25% of females had been offered and accepted CT/NG testing between 2016 and 2021, which is almost double the rate for males. This disparity may partway be explained by the range of opportunities for females to be offered testing beyond the AHC, such as part of antenatal care or cervical screening,24 which have both become embedded parts of women’s health.20 Multiple studies have highlighted that females are more likely to engage with healthcare services for reproductive health than their male peers, leading to higher rates of STI testing outside of the AHC.24–26 Additionally, research has found that conversations about contraception further increase the possibility of STI testing and early diagnosis, and that women are more likely than men to proactively seek STI testing.27 These other opportunities for planned and opportunistic testing for women may result in clinicians not repeating STI tests during an AHC to optimise patient comfort and increase the efficient use of healthcare resources.26 Conversely, for males, the AHC may represent the preferred opportunity for engaging individuals who otherwise may be less likely to access other health care, given the relative anonymity of a standard health check. These differing rates within and outside of the AHC demonstrate the need for a combined approach to attain the optimal level of screening to achieve a public health impact.

In our study, apart from a peak in 2018, a gradual decline in testing rates for men throughout the study period was observed. Similarly, the trend for females also displayed a pattern of gradual decline over the same study period. The recent years from 2019 have seen a particularly marked decrease. Global trends throughout 2020 and 2021 demonstrate that the COVID-19 pandemic had a significant impact on routine sexual health screening.28,29 Studies in Australia corroborate this finding, showing a substantial reduction in asymptomatic sexual health screening during similar timeframes associated with the pandemic.28,29 Our study reflects these global and national patterns, with a clear decline in CT/NG testing from 2020 to 2021. However, the COVID-19 pandemic cannot be considered a definitive cause for the observed decline from 2019. Factors internal to the medical service, such as staff, resources and program changes, may also have influenced the delivery of the AHC and CT/NG testing in the period leading up to the 2020 emergence of COVID-19. This uncertainty necessitates further research to fully comprehend the causes of this decrease, and to develop appropriate public health measures to identify and address declining testing rates early.

The cascade of testing reveals that the diagnosis of CT within the AHC has remained largely stable over the study period, with a slight increase among males in 2017, and among females in 2018 and 2019. The percentage of females diagnosed with NG has been steady at 2% between 2016 and 2021. Concurrently, there was a peak in the rate of male diagnoses with 7% in 2016, followed by no recorded cases from 2020 to 2021.

There is growing support for the integration of STI testing into routine care, such as the AHC for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people.1 Recent research has shown that providing STI testing as part of routine health care can help mitigate some of this shame and stigma associated with STIs.1 However, even though the AHC for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples has been welcomed, in terms of preventive healthcare delivery, there have been several barriers identified in providing the AHC. One challenge that clinic staff face when implementing health checks are time constraints for both clients and clinic employees.30 There is also a lack of clarity regarding staff responsibilities for initiating and carrying out the AHC.30 Additionally, staff may have concerns about the content of the AHC, as some assessment questions are seen as sensitive, intrusive, culturally inappropriate and of dubious usefulness.30 Confidentiality and privacy are also challenges.30 Furthermore, clinic staff may be disengaged from preventative health care, have concerns for community health literacy or find clinical systems for conducting health checks unclear. The need for clear service-wide protocols that facilitate health checks to enhance acceptance has been identified.30

A comprehensive approach in promoting STI testing that addresses the decision-making process regarding STI testing for both clients and clinicians is needed.31 Our study suggests that these programs need to consider sex. Additionally, various factors, such as employment status, experiences of intimate partner violence and sexual health knowledge, have been identified as significant influences on engagement with STI testing services,32–34 suggesting it is imperative that the broader social determinants of health factors that influence decisions to engage in and offer STI testing are incorporated.

One of the strengths of this study is that it focused solely on an urban ACCHS. A recent study by McCormack et al.21 examining urban, remote and very remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples populations found significantly lower rates of testing among the urban-/metropolitan-based ACCHS compared with those based in remote and very remote areas. This suggests integration of STI testing has been more effective in regions where the highest STI prevalence rates have historically been recorded.35 The sex disparity suggests the need for strategies to increase testing among young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples living in non-urban settings has been effective for both men and women, potentially offering solutions for urban based ACCHS.

Limitations

The strengths of this study lie in the data extracted, via electronic patient systems (MMEx) through the ATLAS project, which included the total client population over a 6-year period from 2016 to 2021 and included all age groups. However, we must consider some limitations when interpreting our results. One limitation is the absence of data on the presenting consultation for clients who underwent STI testing during other non-AHC clinical attendance. This lack of information makes it difficult to compare the reasons for seeking STI testing between clients who had an AHC and those who did not, particularly the lack of detail regarding the symptomatic status of clients who did not undergo an AHC. It is important to consider whether these individuals were experiencing any symptoms that may have prompted them to seek STI testing, as this could impact their decision-making process. Although the study acknowledges the potential impact of COVID-19 on STI testing during AHC consultations, it does not provide a comprehensive analysis of this relationship, nor account for the decline that predated the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The specific effects or changes in STI testing behaviours within the AHC setting are not fully explored.

Conclusion

Embedding and delivering CT/NG screening within the AHC is an important initiative for increasing testing rates within the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples community. Our study highlights the importance of implementing strategies to optimise testing rates outside of the AHC, especially for young men. Normalising CT/NG testing within a wider array of tests that are included in the AHC and across the healthcare continuum will assist to demystify the stigma that surrounds sexual health and contribute to the long-term sustainability of STI screening through primary care.

Data availability

The data that support this study were obtained from the ATLAS network by permission/licence. Data will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author with permission from both the ACCHS involved and the ATLAS network.

References

1 McCormack H, Guy R, Bourne C, Newman CE. Integrating testing for sexually transmissible infections into routine primary care for Aboriginal young people: a strengths-based qualitative analysis. Aust N Z J Public Health 2022; 46(3): 370-376.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

2 Sonnenberg P, Clifton S, Beddows S, Field N, Soldan K, Tanton C, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and uptake of interventions for sexually transmitted infections in Britain: findings from the national surveys of sexual attitudes and lifestyles (Natsal). Lancet 2013; 382(9907): 1795-1806.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

3 Østergaard L, Andersen B, Møller JK, Olesen F. Home sampling versus conventional swab sampling for screening of Chlamydia trachomatis in women: a cluster-randomized 1-year follow-up study. Clin Infect Dis 2000; 31(4): 951-957.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

4 Ward J, Bryant J, Worth H, Hull P, Solar S, Bailey SL. Use of health services for sexually transmitted and blood-borne viral infections by young Aboriginal people in New South Wales. Aust J Prim Health 2013; 19(1): 81-86.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

5 Graham S, Guy RJ, Wand HC, Kaldor JM, Donovan B, Knox J, et al. A sexual health quality improvement program (SHIMMER) triples chlamydia and gonorrhoea testing rates among young people attending Aboriginal primary health care services in Australia. BMC Infect Dis 2015; 15: 370.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

8 Silver BJ, Knox J, Smith KS, Ward SJ, Boyle J, Guy RJ, et al. Frequent occurrence of undiagnosed pelvic inflammatory disease in remote communities of central Australia. Med J Aust 2012; 197(11–12): 647-651.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

9 Goyal MK, Teach SJ, Badolato GM, Trent M, Chamberlain JM. Universal screening for sexually transmitted infections among asymptomatic adolescents in an urban emergency department: high acceptance but low prevalence of infection. J Pediatr 2016; 171: 128-132.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

10 Butler D, Agostino J, Paige E, Korda RJ, Douglas K, Wade V, et al. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health checks: sociodemographic characteristics and cardiovascular risk factors. Public Health Res Pract 2022; 32(1): e3102103.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

11 Spurling GKP, Hayman NE, Cooney AL. Adult health checks for Indigenous Australians: the first year’s experience from the Inala Indigenous Health Service. Med J Aust 2009; 190(10): 562-564.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

12 Mayers NR, Couzos S. Towards health equity through an adult health check for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people: an important Australian initiative that sets an international precedent. Med J Aust 2004; 181(10): 531-532.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

15 Bradley C, Hengel B, Crawford K, Elliott S, Donovan B, Mak DB, et al. Establishment of a sentinel surveillance network for sexually transmissible infections and blood borne viruses in Aboriginal primary care services across Australia: the ATLAS project. BMC Health Ser Res 2020; 20(1): 769.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

17 Stephens JH, Gray RT, Guy R, Vickers T, Ward J. A HIV diagnosis and treatment cascade for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples of Australia. AIDS Care 2023; 35(1): 83-90.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

18 McGuffog R, Chamberlain C, Hughes J, Kong K, Wenitong M, Bryant J, et al. Murru Minya–informing the development of practical recommendations to support ethical conduct in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health research: a protocol for a national mixed-methods study. BMJ Open 2023; 13(2): e067054.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

19 Lloyd-Johnsen C, Eades S, D’Aprano A, Goldfeld S. What’s data got to do with it? A scoping review of data used as evidence in policies promoting the health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in the Northern Territory, Australia. Health Promot J Austr 2022; 34(2): 443-471.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

21 McCormack H, Wand H, Bourne C, Ward J, Bradley C, Mak D, et al. Integrating testing for sexually transmissible infections into annual health assessments for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people: a cross-sectional analysis. Sex Health 2023; 20(6): 488-496.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

22 Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Indigenous health checks and follow-ups for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. AIHW: Australian Government; 2024. Available at https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/indigenous-australians/indigenous-health-checks-follow-ups/contents/health-checks/national-use-of-health-checks [cited 21 January 2025]

23 Regan DG, Wilson DP, Hocking JS. Coverage is the key for effective screening of Chlamydia trachomatis in Australia. J Infect Dis 2008; 198(3): 349-358.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

24 Nattabi B, Matthews V, Bailie J, Rumbold A, Scrimgeour D, Schierhout G, et al. Wide variation in sexually transmitted infection testing and counselling at Aboriginal primary health care centres in Australia: analysis of longitudinal continuous quality improvement data. BMC Infect Dis 2017; 17(1): 148.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

25 Huff MB, McClanahan KK, Brown HA, Omar HA. It is more than just a reproductive healthcare visit: experiences from an adolescent medicine clinic. Int J Adolesc Med Health 2009; 21(2): 243-248.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

26 Yavorsky RL, Hollman D, Steever J, Soghomonian C, Diaz A, Strickler HD, et al. Prevalence of sexually transmitted infections in at-risk adolescent females at a comprehensive, stand-alone adolescent health center in New York City. Clin Pediatr 2014; 53(9): 890-895.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

27 Batteiger TA, Dixon BE, Wang J, Zhang Z, Tao G, Tong Y, et al. Where do people go for gonorrhea and chlamydia tests: a cross-sectional view of the central Indiana population, 2003–2014. Sex Transm Dis 2019; 46(2): 132-136.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

28 Braunstein SL, Slutsker JS, Lazar R, Shah D, Hennessy RR, Chen SX, et al. Epidemiology of reported HIV and other sexually transmitted infections during the COVID-19 pandemic, New York City. J Infect Dis 2021; 224(5): 798-803.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

29 Berzkalns A, Thibault CS, Barbee LA, Golden MR, Khosropour C, Kerani RP. Decreases in reported sexually transmitted infections during the time of COVID-19 in King County, WA: decreased transmission or screening? Sex Transm Dis 2021; 48(8S): S44-S49.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

30 Jennings W, Spurling GK, Askew DA. Yarning about health checks: barriers and enablers in an urban Aboriginal medical service. Aust J Prim Health 2014; 20(2): 151-157.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

31 Logie CH, Okumu M, Mwima S, Kyambadde P, Hakiza R, Kibathi IP, et al. Sexually transmitted infection testing awareness, uptake and diagnosis among urban refugee and displaced youth living in informal settlements in Kampala, Uganda: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Sex Reprod Health 2020; 46(3): 192-199.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

32 Bell S, Aggleton P, Ward J, Murray W, Silver B, Lockyer A, et al. Young aboriginal people’s engagement with STI testing in the Northern Territory, Australia. BMC Public Health 2020; 20(1): 459.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

33 Sabri B, Wirtz AL, Ssekasanvu J, Nalugoda F, Kagaayi J, Ssekubugu R, et al. Intimate partner violence, HIV and sexually transmitted infections in fishing, trading and agrarian communities in Rakai, Uganda. BMC Public Health 2019; 19(1): 594.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

34 Skaletz-Rorowski A, Potthoff A, Nambiar S, Basilowski M, Wach J, Kayser A, et al. Online HIV/STI risk test (ORT): a prospective cross-sectional study among sexually active individuals in Germany. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2022; 20(3): 306-314.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

35 Hengel B, Guy R, Garton L, Ward J, Rumbold A, Taylor-Thomson D, et al. Barriers and facilitators of sexually transmissible infection testing in remote Australian Aboriginal communities: results from the sexually transmitted infections in remote communities, improved and enhanced primary health care (STRIVE) study. Sex Health 2014; 12(1): 4-12.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |