Provider views of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for cisgender women – where do women fit in HIV elimination in Australia?

Caroline Lade A , Catherine MacPhail

A , Catherine MacPhail  B * and Alison Rutherford

B * and Alison Rutherford  A

A

A

B

Sexual Health - https://doi.org/10.1071/SH23163

Submitted: 8 February 2023 Accepted: 9 October 2023 Published online: 31 October 2023

Abstract

HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in Australia has largely been targeted at gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men. In the context of HIV elimination, the aim of this qualitative study was to explore PrEP prescribing for Australian cisgender women from the provider’s perspective.

Semi-structured interviews were held with Australian prescribers in 2022. Participants were recruited through relevant clinical services, newsletter distribution and snowball sampling. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed and analysed thematically.

Seventeen prescribers participated, of whom 9 were sexual health physicians and 10 worked in New South Wales. All reported limited clinical experience prescribing PrEP for women. Potential enablers to PrEP prescribing to women included education for women and clinicians, easily identifiable risk factors, individualised risk assessment and expansion of existing services. Barriers were limited PrEP awareness among women and prescribers, difficulties with risk assessment and consult and service limitations. The type of service recommended for PrEP provision varied among participants.

Clinician experience of PrEP prescribing to Australian cisgender women is limited, with substantial barriers to access perceived by prescribers. Targeted education to PrEP prescribers, updated national PrEP guidelines to include women as a distinct group and further research regarding women’s preferred model of PrEP access are required. Clarity of clinical ownership over PrEP implementation for women and, more broadly, women’s sexual health, is essential in order to achieve HIV elimination in Australia.

Keywords: Australia, general practice, HIV, implementation, pre-exposure prophylaxis, PrEP, prescribers, prevention, primary care, qualitative, sexual health, women.

Introduction

HIV continues to cause significant global impact, with an estimated 38 million people living with HIV worldwide.1 Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is an effective method of preventing HIV, involving the use of antiretroviral medications in HIV-negative people.2 There are approximately 29 500 people living with HIV (PLWH) in Australia, the majority of whom are gay, bisexual or other men who have sex with men (GBMSM).3 Widespread PrEP uptake has contributed to significant reductions in HIV notifications among Australian born GBMSM over the past 10 years.3,4

Women and girls are disproportionately affected by HIV globally, accounting for more than 50% of all PLWH, but are not a priority population in most high-income countries.1 Approximately 12% of PLWH in Australia are women.3 Unlike the success of PrEP in GBMSM in Australia, declines in HIV incidence among other populations, including cisgender women, have not been observed.3 Health Equity Matters (formerly known as the Australian Federation of AIDS Organisations) has set out Agenda 25, with the goal of ending HIV transmission in Australia by 2025.3,5 Agenda 25 highlights the importance of reaching all populations at risk of HIV, with specific mention of women.5,6

Although the incidence is low, certain subgroups of Australian women may be at higher risk of HIV. Around half of new diagnoses in heterosexual women occur in those born overseas3,7 and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander woman are disproportionately affected.3 Of new HIV diagnoses among GBMSM, the percentage of men also reporting sex with women has increased over the past 10 years and late diagnosis is more common among men who have both male and female sexual partners, suggesting these women with GBMSM sexual partners may be at risk of HIV.3 A 2018 survey of women connected with the queer community in Sydney demonstrated an increase in the proportion of women who reported often having unprotected sex with a gay or bisexual man.8 Female sex workers and women who inject drugs may also be at risk, though the HIV incidence in these populations in Australia is low.3

Oral co-formulated tenofovir and emtricitabine for the prevention of HIV has been subsidised by the Australian Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) since April 2018.2 Long-acting injectable PrEP is licenced but not government subsidised and use is very limited.9 Early Australian PrEP guidelines classified an individual’s HIV risk as high or low, and eligibility was restricted to patients identified as high risk.2 In an effort to expand PrEP access to all at risk people however, current guidelines outline criteria for suitability rather than eligibility.2 Although there are no specific criteria for women, the criteria for heterosexual people include: condomless anal or vaginal intercourse (CLAVI) with a serodiscordant partner who has a detectable viral load, for conception or if there is undue anxiety; CLAVI with a male bisexual partner of unknown status; plans to travel to high HIV prevalence countries where they anticipate CLAVI; and concerns of deteriorating mental health or substance use with a history of increased HIV acquisition risk in this setting.2

Despite guidelines that affirm PrEP suitability for women, there has been limited uptake in Australia. A review of individuals dispensed PBS-subsidised PrEP between April 2018 and June 2022 found only 2% were female, although this does not differentiate between cisgender women and gender diverse people.10 Estimations of PrEP coverage for women in other non-endemic countries are similarly low; only 10% of US women identified as eligible by prevailing guidelines were prescribed PrEP in 2019.11 Evidence also suggests substantial discontinuation of PrEP for women after initiation, including in the Australian context.12,13

A major barrier to uptake is low PrEP awareness in PrEP-eligible cisgender women.14,15 Other reported barriers for women include a low self-perceived risk of HIV, having other priorities, concerns about potential side effects, adherence difficulties, cost, poor access, negative experiences or a lack of trust with healthcare providers and experiences of stigma.12,16,17 Provider based barriers include clinician difficulties identifying at-risk women,10 lack of knowledge about PrEP, time constraints, concern about efficacy and cost to patients.18,19 Potential PrEP enablers for women include increasing education and expanding public health messaging to services where women access health care.16 Provider perspectives on enablers are limited in available literature19 although some qualitative studies have recommended an increase in training for providers and resources for women.18,20

The aim of this descriptive qualitative study14,15 was to explore PrEP prescribing for Australian cisgender womenA from the provider’s perspective. Through interviews with prescribers, we aimed to determine the barriers to uptake and enablers to facilitate PrEP prescribing, in light of the new opportunities to focus on HIV prevention in sub-populations that have received less attention than GBMSM.

Materials and methods

Participant inclusion criteria were:

Current HIV PrEP prescriber with experience prescribing PrEP for Australian women;

Fluent English language skills; and

Availability to attend a video or teleconference interview in 2022.

Participant recruitment occurred from February 2022 to October 2022. Participants were recruited through direct email contact with Australian wide prescribers and services, including individual prescribers on publicly available online lists, sexual health clinics, general practices, refugee health services, university health services, infectious disease clinics and family planning clinics. Snowball sampling was utilised in addition to direct contact. We aimed to capture a broad range of experiences, with prescribers from a variety of locations, services and professions. Recruitment continued until data saturation occurred.16

A draft interview guide was developed based on a review of the literature and research team discussion. A pilot interview was conducted with an experienced sexual health clinician in February 2022 to refine the guide. Semi-structured interviews were conducted via video or teleconference. The interviews covered participant experience prescribing PrEP for cisgender women, and enablers and barriers for prescribing. Participants completed a short demographic questionnaire and provided written informed consent. Participants were reimbursed for their time with an AUD50 voucher.

All interviews were performed by Principal Investigator (PI) Lade, an Anglo-Australian female Sexual Health Advanced Trainee. Four participants were known to PI Lade on a professional basis. Interviews were recorded and transcribed by an external company and identifying information was removed. A framework analysis was conducted17 with an initial code frame derived from the literature and the topic guide. Initial thematic analysis was performed deductively by PI Lade using NVivo, a qualitative data analysis software.21 In keeping with a descriptive qualitative methodology, the analysis remained grounded in the data, such that data might also be coded inductively22 and codes were regularly discussed with the wider research team. Data was reduced in coding matrices and grouping used to identify the main themes in the data.

This study was approved by the Joint University of Wollongong and Illawarra Shoalhaven Local Health District Health and Medical Human Research Ethics Committee (2021/ETH11873).

Results

Seventeen participants were interviewed for between 15 and 38 min. Nine participants identified as female and eight as male. The majority were sexual health physicians (SHP) (n = 11, 64.7%), with other professional backgrounds also represented (Table 1). Fifteen participants worked primarily in publicly funded sexual health clinics, though four of these participants also worked in another setting – one in a family planning clinic and three in general practice. The majority of participants worked in New South Wales (n = 10, 58.8%). Most participants were experienced PrEP prescribers, with only two self-identifying as new prescribers. Prescribers reported predominantly prescribing PrEP to GBMSM patient cohorts, with some participants also prescribing to trans and gender diverse people. All reported limited experience prescribing PrEP for cisgender women, with less than five cases in the preceding 12 months. Three participants reported only prescribing PrEP to a woman once in their career.

| Participant characteristic | Participants – n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age group | 30–44 years | 9 (52.9) | |

| 45–59 years | 6 (35.3) | ||

| >60 years | 2 (11.8) | ||

| Gender | Female | 9 (52.9) | |

| Male | 8 (47.1) | ||

| ProfessionA | Sexual health physician | 11 (64.7) | |

| General practitioner | 4 (23.5) | ||

| Registrar/resident | 3 (17.6) | ||

| Infectious disease physician | 1 (5.9) | ||

| Nurse practitioner | 1 (5.9) | ||

| Service setting | Sexual health clinic | 15 (88.2) | |

| General practice | 5 (29.4) | ||

| Family planning clinic | 1 (5.9) | ||

| State | NSW | 10 (58.8) | |

| SA | 3 (17.6) | ||

| QLD | 1 (5.9) | ||

| Vic. | 1 (5.9) | ||

| Prefer not to say | 2 (11.8) | ||

| Self-identified experience level | Experienced prescriber | 15 (88.2) | |

| New prescriber | 2 (11.8) |

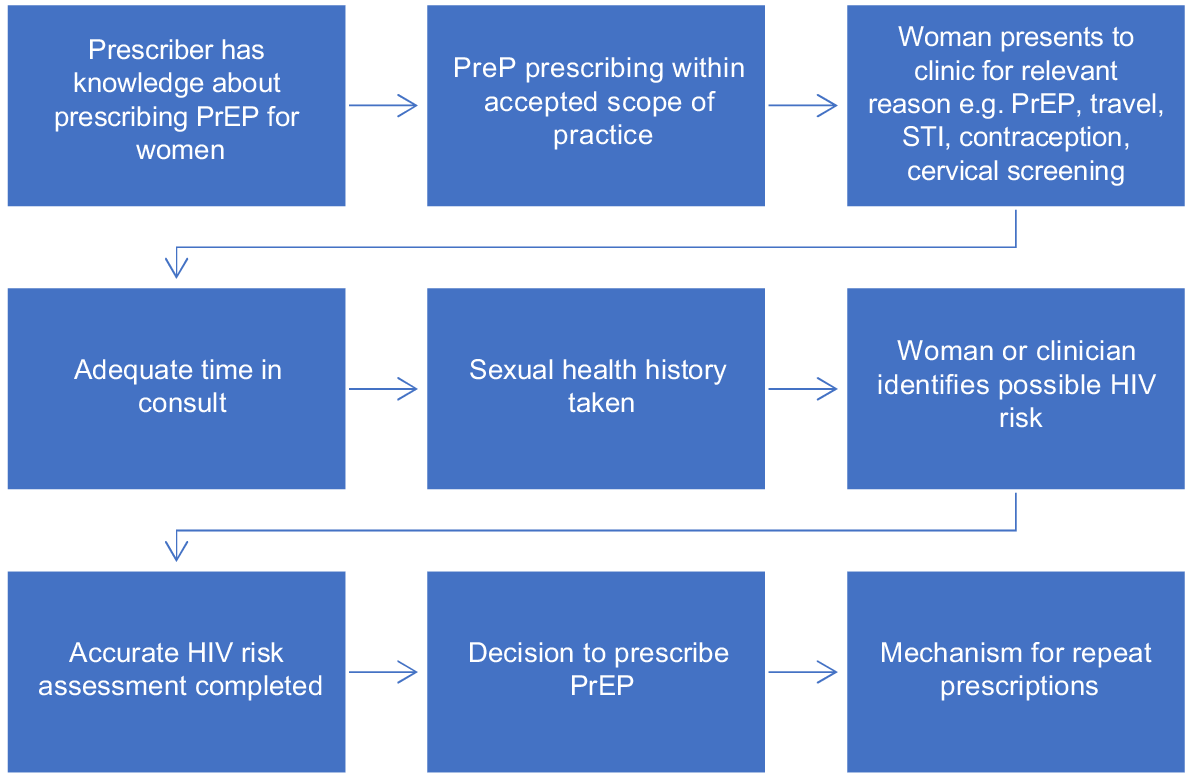

Identified barriers and enablers to PrEP prescribing for women in Australia are in Table 2. The provider pathway for PrEP prescribing to women is outlined in Fig. 1.

| Barriers | Enablers | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Awareness | Women unaware of PrEP availability | Targeted health promotion | |

| Lack of experience/low caseload prescribers | Clinician education | ||

| Lack of targeted education to prescribers | |||

| Women’s risk | PrEP prescribing based on partner risk factors rather than the patient’s own risk factors | Women at risk identified through HIV positive partners (serodiscordant relationship) | |

| Women assumed to be low risk | Risk easily identified (e.g. concurrent STI, condomless anal intercourse) | ||

| Concern about over prescribing to low risk population | Individual risk assessment | ||

| High risk threshold required to prompt consideration of PrEP | |||

| Consult and service issues | Competing priorities in women’s consults | Expansion of existing services | |

| Additional consult time | |||

| No clinical ownership over PrEP implementation | |||

| Barriers at each identified potential service including general practice, sexual health clinics, reproductive health clinics, refugee health service and travel medicine clinics |

The three main themes that emerged were:

Limited awareness among women and prescribers;

Women’s risk not recognised; and

Consult and service issues with providing PrEP to women.

Limited awareness among women and prescribers

Most respondents reported low PrEP awareness among women. As one participant stated, ‘[Women are] astounded when you say that we can prevent HIV infection with a tablet.’ (P07, Registrar/Resident). This presumed lack of awareness resulted in a need for greater time spent on education compared to typical GBMSM PrEP consults.

I suppose I assume for most female patients that there’s either little or no awareness of PrEP, so I feel like I have to explain it in greater detail. (P02, SHP)

Similarly, participants reported a low awareness of PrEP for women among clinicians, particularly within general practice.

I think not all women access their sexual healthcare in a specialist service, so that’s one. So, does the GP know? Does the patient know? Is there information for them? So, I think that’s both health literacy on both parts, and also then if they were to come, would the GP feel equipped to prescribe it, or even start the conversation? (P16, SHP)

Concern with general practitioners’ (GPs) ability to prescribe PrEP for women was also raised by most participating GPs themselves. One stated, ‘There’s a certain way that GPs are taught to prescribe it. They’re taught to look for this particular or certain demographics or certain people to prescribe it to. They’re teaching us usually to pretty much ignore cisgendered women.’ (P08, GP).

A majority of participants felt that public education and health promotion was required to improve PrEP access for women, including sexual health education in schools.

I guess marketing is very targeted to MSM. I mean, that’s a problem for a whole host of reasons… It’s kind of having these little bespoke marketing campaigns that are trying to find a less reachable population within the standard social media things that cis women may not be, probably aren’t, looking at.... (P13, SHP)

Participants felt that health promotion needed to target women directly, although some voiced concerns that this may lead to inappropriate PrEP requests from low-risk women.

So, there is an argument for education, but that might oversell it a bit, as well... I think if we do too much education on it, then we might get people inappropriately requesting it. (P03, Registrar/resident)

Clinician education surrounding PrEP for women, with a particular emphasis on expanding GP education, was recommended by many participants.

I think if more people and more of the GPs were aware of it and comfortable with it, they’d probably be more comfortable offering it to women. (P07, Registrar/resident)

The last time I went to such a PrEP talk... the angle was very much on prescribing for MSM communities. I’ve never been to a session where they talked about the general population. I suppose changing those to include a general population that would be more ideal. (P08, GP)

Women’s risk not recognised

Most participants reported feeling comfortable prescribing PrEP for women in serodiscordant relationships, where the risk of HIV was easily identifiable. This was largely in the context of a partner with a new HIV diagnosis, unsuppressed viral load or for conception planning. Many noted this was less relevant in the context of Undetectable = Untransmissible (U=U), where effective HIV treatment with virological suppression is known to reduce the risk of sexual transmission of HIV to zero.23,24 One participant described a similar low awareness of U=U for women, stating ‘…I think that’s one of the reasons why … women are on PrEP is because U=U is not trickling down, actually, in this population as in the MSM.’ (P12, SHP). Other participants spoke about prescribing for women even in the setting of U=U, citing concerns about partner compliance, patient mistrust of U=U and patient peace of mind.

Her partner was HIV positive, and actually I put her on PrEP... I thought it was prudent that she was on PrEP, because she was indicating she didn’t believe that he could always be taking his medications, and she didn’t have a way of really knowing. (P04, SHP)

Participants also described prescribing PrEP to women in perceived high-risk situations, including having non-monogamous GBMSM or transgender sexual partners, condomless anal intercourse, having a concurrent sexually transmitted infection (STI) and having multiple sexual partners.

Difficulties assessing risk was described by participants as a barrier from both patient and clinician perspectives. They explained that patients may be unaware of or choose not to disclose their risk factors. Given the low HIV prevalence in Australian women, clinicians may also assume women are low risk and not consider discussing PrEP.

…either the clinician or the patient are either misrepresenting the risks, or not considering it, or saying there isn’t a risk sufficient to think about PrEP, and so we’re not using it. (P16, SHP)

This was reflected in the responses surrounding cisgender female sex workers (FSW). Most participants reported not routinely prescribing PrEP in this population, due to the perceived low HIV transmission risk for FSW in Australia. It is worth noting that the following assumption from Participant 3 that cisgender men were less likely to be GBMSM is inaccurate.

If they’re a female sex worker working in a brothel with cis male partners, then it’s less likely that those are MSM, and they’re having oral and vaginal sex only, then I wouldn’t be inclined to prescribe them PrEP. I’d just have that open discussion with them, and say it’s not really part of our guidelines here. (P03, Registrar/resident)

In contrast, some participants described a nuanced approach to FSW, involving assessment of individual risk and capacity to negotiate condom use.

We get also a lot of commercial sex workers at the sexual health clinic, and they are highly inclined to take PrEP, because they say some of their clients, they refuse to use condoms, and sometimes... the condom breaks as well. (P17, Nurse Practitioner)

One recurring perception was that women need to meet multiple risk factors in order to be prescribed PrEP, suggesting women need to cross a higher risk threshold than GBMSM when attempting to access PrEP.

I guess, to me, one factor alone may not be enough for me to offer PrEP proactively, whether that’s right or wrong, but I suppose, in my mind, if two or more of these factors co-exist, then I’m much more likely. If a woman we know is escaping a domestic abuse situation, has very, very limited sexual autonomy, and the community group is from a high prevalence setting... I’m much more likely to offer PrEP. (P02, SHP)

Consult and service issues with providing PrEP to women

Many participants reported competing priorities in women’s consults as a barrier to PrEP prescribing.

There’s all the standard STI considerations, the contraception considerations, and there’s all the sex worker welfare-type considerations, and PrEP kind of just becomes one of many, many different things… With the other priority populations … there are fewer things to juggle, and PrEP can occupy a bigger part of the consultation. (P02, SHP)

Consultations with women were perceived as more time consuming and likely to exceed a standard consult time, therefore limiting both opportunity and inclination to initiate conversations about PrEP. These opinions were shared by participants from a variety of professions and genders.

I hate to say it, but females also have a lot more issues to be bringing up... Again, because of the nature of lots of women’s consults, they do tend to be longer, and so do you want to probe – can you and do you have the patience to prolong that further for something brand new to bring up in a consult? (P10, GP)

Time constraints and service limitations were highlighted as barriers to PrEP for women. A sexual health physician asked ‘So, how do you provide PrEP to heterosexual women? I don’t know. Are we [sexual health clinics] the best place for it? We don’t even see them for their problems.’ (P12, SHP) suggesting that the public model of PrEP provision that has proved so effective for GBMSM is not suitable for women who may need this service. This was echoed by another sexual health physician who noted that there was not an obvious clinical site where women’s access to PrEP could be assured.

Well, publicly funded sexual health clinics are very focused on providing services for men who have sex with men and HIV positive people, a lot of whom are obviously men so obviously [women are] not getting PrEP... Women’s health centres I think would be pretty unlikely to be providing PrEP and I think GPs have a very variable capacity and ability to provide PrEP. (P14, SHP)

Several respondents felt that PrEP access for women could be improved by expanding existing services including general practice, obstetrics and gynaecology, reproductive health services, refugee health and sexual health clinics. Some participants however, raised concerns that women accessing PrEP would place extra strain on their service.

It’s not like we’re advertising that, but there might be a reason we’re not advertising it, because we don’t want additional discussions about that which would take away from clinician time, and clinician time is a precious resource in a clinic like this. (P06, SHP)

All three participants who recommended expanding access in general practice were sexual health physicians and only one of these participants also suggested sexual health services as an avenue for PrEP access.

Discussion

The focus of Australia’s HIV response has been on GBMSM. The significant impact of PrEP on preventing HIV transmission has encouraging potential for eliminating all transmission in Australia,4 warranting a focus on other populations, including women. To date, PrEP prescribing for women in Australia has been very limited,10 as reflected by participant responses. Participants reported most experience prescribing PrEP for women in serodiscordant relationships, as reflected in the literature25 and likely due to serodiscordant status being easily identifiable.13 Other potential PrEP indications may rely on knowledge of partner risk factors (e.g. GBMSM status) and are therefore difficult for clinicians to ascertain.26 Women may underestimate or be unaware of their risk.25,27 Women are also less likely to be asked about PrEP indications than other groups,25 suggesting that women at risk of HIV may not be offered PrEP.13 Experienced PrEP providers were likely trained in the era of ‘eligibility’ for PrEP and may easily have missed the nuances in the updated PrEP guidelines which have pivoted towards making PrEP available to anyone who is suitable or requests it.2 Participants also described the need for women to meet multiple risk factors in order to receive PrEP, which is not in keeping with PrEP suitability criteria in current Australian guidelines.5 These responses highlight that clinician assumptions of HIV risk for women may be inaccurate and hinder PrEP provision.

The research has identified many more barriers than enablers to PrEP prescribing to Australian women (Table 2). A common barrier reported was low awareness of PrEP for women among clinicians and patients, which is consistent with international data.8,25,28–32 There was concern about lack of awareness among GPs, including from participants working within this profession. Primary care providers have previously identified limited knowledge about PrEP and lack of confidence as prescribing barriers.33,34 One US survey found that although 90% of primary care physicians reported some type of PrEP education, only 55% self-assessed as competent to prescribe.34 Australian HIV experts have also expressed concerns that PrEP delivery in primary care relies on an empowered and knowledgeable patient managing an ‘unprepared GP’.35 Our participants consistently recommended public and clinician education, and this has been echoed in the US,25,32 with a call from women for awareness through public health messaging including traditional advertising, social media and communication from health services.30,31

Participants reported that compared to GBMSM patients, PrEP prescribing for women occurred in the context of competing priorities and longer consultations, which was a barrier to prescribing. Australian primary care data demonstrate that GPs manage significantly more problems per consult with female patients.36 Women have also reported that time limitations in consultations prevent rapport building and open discussion of sexual health including PrEP.25,37 This highlights inadequacies in the current model of sexual healthcare provision for Australian women.

Expansion of existing services was a common recommendation, although participants disagreed about where and how. PrEP access in general practice was predominantly suggested by sexual health physicians. This indicates a continuation of the ‘purview paradox’ seen in the early stages of PrEP implementation both in Australia and internationally, whereby neither HIV specialists nor GPs believe they should be responsible for PrEP.38,39 HIV specialists have considered PrEP to be in the realm of general practice, although many were also critical of GP-led PrEP provision.35,38,40,41 GPs however, have described feeling unable to provide PrEP due to time constraints, lack of training and difficulty building expertise due to lack of patient demand.38,40,41 Responses from our participants suggest women are similarly impacted by this gap in PrEP ownership.

The question remains – where is the best place is for at-risk women to access PrEP in Australia? Women have reported a preference for PrEP-initiation where they usually access medical care or through reproductive healthcare services.30,31,37 Data from the US indicate that almost three-quarters of women access PrEP via general practice or women’s health services.42 Our participants also proposed access via refugee and reproductive health services; however, when investigators contacted these services during recruitment, none reported experience prescribing PrEP. Australian research has demonstrated PrEP discontinuation is higher for patients receiving PrEP from low caseload prescribers.12 Consequently, women may be at risk of early cessation when receiving PrEP from inexperienced prescribers, including low caseload GPs and other services suggested by participants.

There are several limitations to this study. Four participants were known to the interviewer on a professional basis, which may have impacted upon responses, although efforts were made to ensure participant comfort with the interview. The data may not represent Australia nationally as more than half of participants were based in NSW, where there are higher rates of PrEP dispensing.43 The majority of participants were sexual health physicians. As high-caseload prescribers are responsible for prescribing to the majority of patients, this may reflect the very limited experience of PrEP provision to women in Australia.43 Travel medicine clinicians were not specifically recruited in this study and may be of interest for future research, in order to capture experience prescribing PrEP to women travelling to high HIV prevalence countries.44

Conclusion and recommendations

This study has demonstrated limited PrEP prescribing for Australian cisgender women, even among PrEP-experienced prescribers. It highlights the substantial barriers to PrEP access for women in high-income countries: limited awareness amongst patients and clinicians, difficulties with risk assessment and a lack of women-focused sexual health services. Despite Agenda 25’s goal to reach all those affected, it is evident we are leaving women behind in the race to achieve HIV elimination in Australia. Women have specific needs for PrEP delivery that are not being met by the current model in Australia. Echoing the calls of our participants, we recommend targeted education on broader PrEP prescribing to both experienced and inexperienced providers. National PrEP guidelines should be updated to specifically discuss PrEP for women rather than subsuming women under ‘heterosexual populations’. Participants disagreed on the most appropriate service to provide PrEP for women and the literature is similarly conflicted. Further research among women regarding preferences and opportunities for PrEP access would help guide our model of delivery. Clear clinical ownership over Australian women’s sexual health issues, including PrEP implementation, is required.

Data availability

The data that support this study will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Declaration of funding

The project was supported by an independent Research Grant Fellowship (#14549) from Gilead Sciences who had no role in design, data collection, analysis or reporting.

References

11 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV surveillance supplemental report. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2021. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance/vol-26-no-2/index.html [cited 19 November 2022]

12 Medland NA, Fraser D, Bavinton BR, Jin F, Grulich AE, Paynter H, et al. Discontinuation of government subsidised HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis in Australia: a whole-of-population analysis of dispensing records. J Int AIDS Soc 2023; 26(1): e26056.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

13 Blackstock OJ, Patel VV, Felsen U, Park C, Jain S. Pre-exposure prophylaxis prescribing and retention in care among heterosexual women at a community-based comprehensive sexual health clinic. AIDS Care 2017; 29(7): 866-9.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

14 Sandelowski M. What’s in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Res Nurs Health 2010; 33(1): 77-84.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

15 Kim H, Sefcik JS, Bradway C. Characteristics of qualitative descriptive studies: a systematic review. Res Nurs Health 2017; 40(1): 23-42.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

17 Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Qualitative research in health care. Analysing qualitative data. BMJ 2000; 320(7227): 114-6.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

18 Wilbourn B, Ogburn DF, Safon CB, Galvao RW, Kershaw TS, Willie TC, et al. Preexposure prophylaxis implementation in a reproductive health setting: perspectives from planned parenthood providers and leaders. Health Promot Pract 2023; 24(4): 764-75.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

19 Bradley E, Forsberg K, Betts JE, DeLuca JB, Kamitani E, Porter SE, et al. Factors affecting pre-exposure prophylaxis implementation for women in the United States: a systematic review. J Womens Health 2019; 28(9): 1272-85.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

20 Johnson AK, Pyra M, Devlin S, Uvin AZ, Irby S, Blum C, et al. Provider perspectives on factors affecting the PrEP care continuum among black cisgender women in the midwest United States: applying the consolidated framework for implementation research. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2022; 90(S1): S141-s8.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

21 QSR International Pty Ltd. NVivo (Version 12) 2020. Available at https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home

22 Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013; 13: 117.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

23 Rodger AJ, Cambiano V, Bruun T, Vernazza P, Collins S, van Lunzen J, et al. Sexual activity without condoms and risk of HIV transmission in serodifferent couples when the HIV-positive partner is using suppressive antiretroviral therapy. JAMA 2016; 316(2): 171-81.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

24 Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med 2011; 365(6): 493-505.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

25 Baldwin A, Light B, Allison WE. Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV infection in cisgender and transgender women in the U.S.: a narrative review of the literature. Arch Sex Behav 2021; 50(4): 1713-28.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

26 Calabrese SK, Willie TC, Galvao RW, Tekeste M, Dovidio JF, Safon CB, et al. Current US guidelines for prescribing HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) disqualify many women who are at risk and motivated to use PrEP. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2019; 81(4): 395-405.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

27 Nakasone SE, Young I, Estcourt CS, Calliste J, Flowers P, Ridgway J, et al. Risk perception, safer sex practices and PrEP enthusiasm: barriers and facilitators to oral HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis in Black African and Black Caribbean women in the UK. Sex Transm Infect 2020; 96(5): 349-54.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

28 Raifman JR, Schwartz SR, Sosnowy CD, Montgomery MC, Almonte A, Bazzi AR, et al. Brief report: pre-exposure prophylaxis awareness and use among cisgender women at a sexually transmitted disease clinic. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2019; 80(1): 36-9.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

29 Patel AS, Goparaju L, Sales JM, Mehta CC, Blackstock OJ, Seidman D, et al. Brief report: PrEP eligibility among at-risk women in the southern United States: associated factors, awareness, and acceptability. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2019; 80(5): 527-32.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

30 Pasipanodya EC, Stockman J, Phuntsog T, Morris S, Psaros C, Landovitz R, et al. “PrEP”ing for a PrEP demonstration project: understanding PrEP knowledge and attitudes among cisgender women. BMC Womens Health 2021; 21(1): 220.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

31 Hirschhorn LR, Brown RN, Friedman EE, Greene GJ, Bender A, Christeller C, et al. Black cisgender women’s PrEP knowledge, attitudes, preferences, and experience in Chicago. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2020; 84(5): 497-507.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

32 Auerbach JD, Kinsky S, Brown G, Charles V. Knowledge, attitudes, and likelihood of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) use among US women at risk of acquiring HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2015; 29(2): 102-10.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

33 Petroll AE, Walsh JL, Owczarzak JL, McAuliffe TL, Bogart LM, Kelly JA. PrEP awareness, familiarity, comfort, and prescribing experience among US primary care providers and HIV specialists. AIDS Behav 2017; 21(5): 1256-67.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

34 Aurora JA, Jr., Ballard SL, Salter CL, Skinker B. Assessing HIV preexposure prophylaxis education in a family medicine residency. Fam Med 2022; 54(3): 216-20.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

35 Smith AKJ, Holt M, Hughes SD, Truong H-HM, Newman CE. Troubling the non-specialist prescription of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP): the views of Australian HIV experts. Health Sociol Rev 2020; 29(1): 62-75.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

37 Goparaju L, Praschan NC, Warren-Jeanpiere L, Experton LS, Young MA, Kassaye S. Stigma, partners, providers and costs: potential barriers to PrEP uptake among US women. J AIDS Clin Res 2017; 8(9): 730.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

38 Krakower D, Ware N, Mitty JA, Maloney K, Mayer KH. HIV providers’ perceived barriers and facilitators to implementing pre-exposure prophylaxis in care settings: a qualitative study. AIDS Behav 2014; 18(9): 1712-21.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

39 Hoffman S, Guidry JA, Collier KL, Mantell JE, Boccher-Lattimore D, Kaighobadi F, et al. A clinical home for preexposure prophylaxis: diverse health care providers’ perspectives on the “Purview Paradox”. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care 2016; 15(1): 59-65.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

40 Karris MY, Beekmann SE, Mehta SR, Anderson CM, Polgreen PM. Are we prepped for preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP)? Provider opinions on the real-world use of PrEP in the United States and Canada. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 58(5): 704-12.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

41 Smith AKJ, Haire B, Newman CE, Holt M. Challenges of providing HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis across Australian clinics: qualitative insights of clinicians. Sex Health 2021; 18(2): 187-94.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

42 Bien CH, Patel VV, Blackstock OJ, Felsen UR. Reaching key populations: PrEP uptake in an urban health care system in the Bronx, New York. AIDS Behav 2017; 21(5): 1309-14.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

44 Cornelisse VJ, Wright EJ, Fairley CK, McGuinness SL. Sexual safety and HIV prevention in travel medicine: practical considerations and new approaches. Travel Med Infect Dis 2019; 28: 68-73.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |