Interventions supporting engagement with sexual healthcare among people of Black ethnicity: a systematic review of behaviour change techniques

Rebecca Clarke A , Gemma Heath B * , Jonathan Ross C and Claire Farrow B

B * , Jonathan Ross C and Claire Farrow B

A

B

C

Abstract

Black ethnic groups are disproportionately affected by sexually transmitted infections (STIs). This review aimed to identify interventions designed to increase engagement with sexual healthcare among people of Black ethnicity as determined by rates of STI testing, adherence to sexual health treatment, and attendance at sexual healthcare consultations. The behaviour change techniques (BCTs) used within identified interventions were evaluated.

Four electronic databases (Web of science; ProQuest; Scopus; PubMed) were systematically searched to identify eligible articles published between 2000 and 2022. Studies were critically appraised using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool. Findings were narratively synthesised.

Twenty one studies across two countries were included. Studies included randomised controlled trials and non-randomised designs. Behavioural interventions had the potential to increase STI/HIV testing, sexual healthcare consultation attendance and adherence to sexual health treatment. Behavioural theory underpinned 16 interventions which addressed barriers to engaging with sexual healthcare. Intervention facilitators’ demographics and lived experience were frequently matched to those of recipients. The most frequently identified novel BCTs in effective interventions included information about health consequences, instruction on how to perform behaviour, information about social and environmental consequences, framing/reframing, problem solving, and review behavioural goal(s).

Our findings highlight the importance of considering sociocultural, structural and socio-economic barriers to increasing engagement with sexual healthcare. Matching the intervention facilitators’ demographics and lived experience to intervention recipients may further increase engagement. Examination of different BCT combinations would benefit future sexual health interventions in Black ethnic groups.

Keywords: behaviour change, Black minority ethnic groups, intervention, public health, sexual health, sexually transmitted infection, STI testing, systematic review.

Introduction

People from Black ethnic backgrounds are disproportionately affected by sexually transmitted infections (STIs). While there is variation across Black ethnic groups, individuals of Black ethnicity in the UK had the highest STI diagnosis rates in 2022, with those from Black Caribbean backgrounds having the highest diagnosis rates of chlamydia, gonorrhoea, infectious syphilis, trichomoniasis and genital herpes compared to White British individuals.1 Similarly, Black and African Americans in the United States report higher rates of chlamydia, gonorrhoea and infectious syphilis than White individuals.2 Thus, reducing sexual health disparities in high-risk populations has been identified as a priority.3

Literature suggests that no unique clinical, attitudinal or behavioural factors can explain the higher rates of STI diagnosis in Black ethnic groups.4 Therefore, the sexual health disparity between individuals of Black ethnicity and other groups, may be driven by differences in sociocultural, structural and socio-economic factors. For example, sexual networks and increased concurrent sexual partners can influence the speed in which STIs can spread within a population.5 Research indicates the complexity of, and reasons for, concurrent sexual relationships include notions of masculinity, peer pressure and the influence of social media.5 Moreover, individuals of Black ethnicity report experiences of negative racialised stereotypes, not feeling listened to and feeling less comfortable discussing sexual and reproductive health with health care professionals.6,7 Such experiences can create mistrust in sexual health services leading to reduced clinic attendance.8 Furthermore, associations are reported between differences in residential areas and job opportunities, deprivation and poorer sexual health outcomes.9,10 Barriers to accessing sexual healthcare, such as the out-of-pocket costs, are likely to perpetuate disparities in sexual health prevention, diagnosis and treatment.9,10

While existing systematic reviews have examined approaches to reducing sexual health risk behaviours in individuals of Black ethnicity,11 there is a gap in our understanding of how best to support engagement with sexual healthcare among individuals of Black ethnicity who have identified a need to access services or treatment. This review had two aims: (1) collate and assess interventions designed to increase STI testing, STI diagnosis, or STI treatment among individuals of Black ethnicity; and (2) to identify novel behaviour change techniques used within these interventions and their association with effectiveness.

Materials and methods

This review is reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement.12 The review protocol was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (#CRD42021290594).

Eligibility criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they:

Reported an evaluation, and outcome measure for an intervention designed to increase engagement with sexual healthcare, defined by increased rates of STI testing (including home testing kits), diagnosis or treatment, increased attendance at sexual health consultations or clinic visits.

Used a sample of participants aged ≥13 years of age and of any Black ethnic group.

Used any study design (including randomised controlled trials (RCTs), non-randomised controlled groups, single-arm designs, retrospective or prospective cohort studies).

Studies were excluded if they were published before 2000, not fully available in English or did not report outcomes of participants of Black ethnicity separately to those of other ethnicities. Studies conducted in non-WEIRD (western, educated, industrialised, rich, democratic) countries were also excluded. This was because heterogeneity in access to health care and populations was considered to reduce meaningful interpretation of the data.

Information sources and search strategy

Four databases (Web of Science; ProQuest; PubMed, and Scopus) were systematically searched from 1 January 2000 to 10 February 2022. Reference chaining and citation checking via Google Scholar were used to identify additional studies. The search strategy was developed in line with the Population Intervention Comparator Outcome Study design framework.13 Boolean operators were used to adapt the search for each database (see Supplementary File 1).

Study selection and data extraction

One reviewer (RC) screened titles and abstracts. Three researchers (RC, GH and CF) independently screened the full text of relevant articles against the eligibility criteria. Data were extracted from included articles on key study characteristics; e.g. country, study design and setting, recruitment information, sample and intervention content, including use of theory, mode of delivery and behaviour change techniques (BCTs). Use of theory, mode of delivery and BCTs were independently coded by three researchers (RC, GH and CF) and differences were resolved through discussion. Only outcome data relating to this review’s objectives were extracted (i.e. measures for preventative behaviours, such as condom use, were not extracted).

Use of theory

Descriptions of the use of behavioural theory were identified and noted to assess the extent to which theory had been applied within interventions. This included instances where theory had been mentioned in the study, used to select participants, or where theoretical constructs/predictors were linked to intervention techniques.

Mode of delivery

Intervention mode of delivery was subdivided and assessed by an approach outlined by Webb and Sheeran:14 (1) intervention format (e.g. group sessions, text message); and (2) intervention facilitator (e.g. health care professional, digital).

Behaviour change techniques

Intervention content was coded using the Behaviour Change Technique Taxonomy (v1).15 This taxonomy contains 93 BCTs, clustered into 16 groups: Goals and Planning, Feedback and Monitoring, Social Support, Shaping Knowledge, Natural Consequences, Comparison of Behaviour, Associations, Repetition and Substitution, Comparison of Outcomes, Reward and Threat, Regulation, Antecedents, Identify, Scheduled Consequences, Self-Belief, and Covert Learning.

Critical appraisal

Three researchers (RC, GH, CF) independently appraised the methodological quality of included studies using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool.16 An overall quality score was calculated after responding ‘yes’, ‘no’ and ‘can’t tell’ to five questions relevant to the study design. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion.

Data analysis

Due to heterogeneity of the included interventions, a narrative approach was used to synthesise intervention characteristics and outcomes, theoretical application, mode of delivery and BCTs. Interventions were considered effective if the relevant outcome measure was reported to have significantly increased (P < 0.05) in the intervention group and, where available, was significantly greater than in the control group. To ensure that the reported effectiveness of BCTs only reflected active elements in the intervention group, BCTs present in both the intervention group and control groups were not included in analysis. Increase in STI/HIV testing and access to treatment were reported separately to adherence to HIV treatment and appointment attendance.

Results

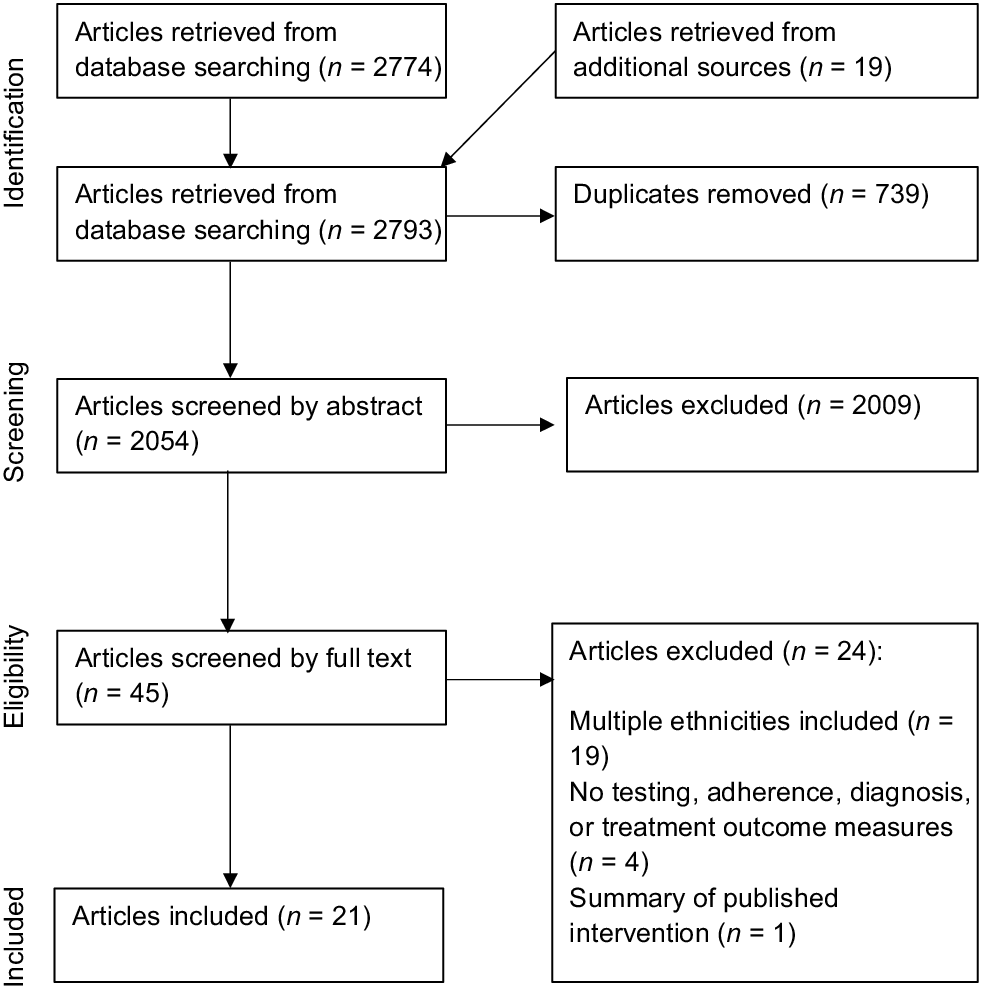

A total of 2793 articles were retrieved. Twenty one articles met the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). Of the 21 included articles, 13 reported RCTs and 8 used non-randomised study designs. Twenty studies were conducted in America and one in the United Kingdom. Studies reported a variety of outcome measures, including HIV testing (n = 11), STI testing (n = 5), treatment for STIs (n = 2), HIV treatment adherence (n = 5) and appointment attendance (n = 2). The follow-up period for measuring outcomes ranged from 2 weeks to 12 months. Further details on the intervention characteristics are in Supplementary Files 2 and 3.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram of the systematic search and selection of articles.

Quality assessment

Methodological quality ranged from low to high, with 9 studies rated as low, 10 rated as moderate and 2 as high (Tables 1 and 2). Intervention fidelity was often unclear.17–24 In some cases, studies reported that participants did not receive all intervention content25–31 or that the delivery protocol was not adhered to.32 Sufficient data were not always provided to compare participant demographics between an intervention and control group18,33 and it was unclear whether participants were representative of the target population.29

| Category of design | Methodological quality criteria | Berkley- Patton et al. 17 | Chittamuru 18 | Diallo et al. 36 | Dolcini et al. 34 | Frye et al. 19 | Frye et al. 20 | Harawa et al. 21 | Jones et al. 22 | Kenya et al. 33 | Sánchez et al. 35 | Seguin et al. 32 | Washington et al. 31 | Wilton et al. 23 | Wingood et al. 24 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2. Quantitative randomised controlled trials | 2.1. Is randomisation appropriately performed? |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | ||||

| 2.2. Are the groups comparable at baseline? |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | |||||

| 2.3. Are there complete outcome data? |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | |||||

| 2.4. Are outcome assessors blinded to the intervention provided? |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | |||||

| 2.5 Did the participants adhere to the assigned intervention? |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | |||||

| 3. Quantitative non-randomised | 3.1. Are the participants representative of the target population? |  |  |  | ||||||||||||

| 3.2. Are measurements appropriate regarding both the outcome and intervention (or exposure)? |  |  |  | |||||||||||||

| 3.3. Are there complete outcome data? |  |  |  | |||||||||||||

| 3.4. Are the confounders accounted for in the design and analysis? |  |  |  | |||||||||||||

| 3.5. During the study period, is the intervention administered (or exposure occurred) as intended? |  |  |  | |||||||||||||

| MMAT score | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

Green ticked boxes, ‘Yes’; orange blank boxes, ‘Can’t tell’; red cross, ‘No’.

0–2, low; 3–4, moderate; 5, high. MMAT, Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool.

| Category of design | Methodological quality criteria | Bogart et al. 25 | Bouris et al. 26 | Guy et al. 27 | Jones 28 | Ma et al. 29 | Magidson et al. 30 | Pagan-Ortiz et al. 37 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2. Quantitative randomised controlled trials | 2.1. Is randomisation appropriately performed? |  |  |  | |||||

| 2.2. Are the groups comparable at baseline? |  |  |  | ||||||

| 2.3. Are there complete outcome data? |  |  |  | ||||||

| 2.4. Are outcome assessors blinded to the intervention provided? |  |  |  | ||||||

| 2.5 Did the participants adhere to the assigned intervention? |  |  |  | ||||||

| 3. Quantitative non-randomised | 3.1. Are the participants representative of the target population? |  |  |  | |||||

| 3.2. Are measurements appropriate regarding both the outcome and intervention (or exposure)? |  |  |  | ||||||

| 3.3. Are there complete outcome data? |  |  |  | ||||||

| 3.4. Are the confounders accounted for in the design and analysis? |  |  |  | ||||||

| 3.5. During the study period, is the intervention administered (or exposure occurred) as intended? |  |  |  | ||||||

| 5. Mixed methods | 5.1. Is there an adequate rationale for using a mixed methods design to address the research question? |  | |||||||

| 5.2. Are the different components of the study effectively integrated to answer the research question? |  | ||||||||

| 5.3. Are the outputs of the integration of qualitative and quantitative components adequately interpreted? |  | ||||||||

| 5.4. Are divergences and inconsistencies between quantitative and qualitative results adequately addressed? |  | ||||||||

| 5.5. Do the different components of the study adhere to the quality criteria of each tradition of the methods involved? |  | ||||||||

| MMAT score | 3 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 5 |

Green ticked boxes, ‘Yes’; orange blank boxes, ‘Can’t tell’; red cross, ‘No’.

0–2, low; 3–4, moderate; 5, high. MMAT, Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool.

Intervention effectiveness

Five interventions aimed to increase STI testing.21,23,24,34,35 Harawa et al.21 used personalised wellness plans, peer mentors, and group educational and social sessions. There was a significant increase in STI screening in the intervention group (pre, 32%; post, 88%) and the control group (pre, 23%; post, 70%). However, no significant between-group changes occurred. Sánchez et al.35 found no differences in ethnic groups syphilis testing rates at a health event promoting syphilis testing in minorities (Black participants, 33.5%; Hispanic participants, 42.6%; other participants, 48.3%; P = 0.055). Dolcini et al.34 reported a psycho-educational friendship group-based intervention did not significantly increase STI testing compared to a control (37% vs 42.4%). Similarly, Wilton et al.23 also found no significant increase in STI testing between a psycho-educational group-based intervention and a wait-list control group at 3-month follow-up (42.5 vs 35.5%, OR = 1.47; 95% CI = 0.86–2.51) and 6-month follow-up (33.9% vs 32.3%, OR = 1.17; 95% CI = 0.69–1.98).

Two studies aimed to increase engagement with STI treatment.22,24 Jones et al.22 reported findings from a contact tracing intervention for chlamydia that was adapted to address barriers to engagement, such as staff availability, method of contact and chlamydia education. After the adaption, participants were significantly more likely to make a treatment plan (RR, 1.14; 95% [CI], 1.01–1.27; P = 0.03) and complete treatment compared with the original intervention (RR, 1.45; 95% [CI], 1.20–1.75; P = 0.0001). Partners of participants were also significantly more likely to complete treatment than those in the original intervention (RR, 3.02; 95% [CI], 1.81–5.05; P = 0.0001).22 Wingood et al.24 reported participants in a psycho-educational intervention for women were more likely to communicate STI results to concurrent male sexual partners (OR = 1.52; 95% CI = 1.11–2.06), and their partners were more likely to complete treatment for STIs (OR = 1.41; 95% CI = 1.05–1.90) than those in the control group.

Eleven further studies aimed to increase testing for HIV.18–22,24,32–35,37 Two of these studies delivered HIV information and content related to HIV-related behaviours/attitudes through video interventions. Washington et al.31 found participants who received the video intervention via social media were seven times more likely to have tested for HIV at 6-week follow-up than those in a control group (OR = 7.00, 95% CI [1.72, 28.33], P=0.006). However, Chittamuru18 reported that a 13-episode drama video did not significantly increase HIV testing compared with the control group at 3-month follow-up.

Four studies used group-based interventions to increase HIV testing. Diallo et al.36 reported a single-session HIV prevention workshop significantly increased HIV testing and receipt of test results compared with the control group at 6 months (AOR = 2.30; 95% CI = 1.10, 4.81). Dolcini et al.34 found 14–15-year-olds in a friendship group-based intervention for young people were more likely to have tested for HIV than those in a control group (OR = 7.43, P = 0.05, 95% CI = 0.95–58.33). Dolcini et al.34 suggested different ages may respond differently to intervention content and future interventions should be refined specifically for developmental groups. Frye et al.19 reported no significant increase in HIV testing at 3 months following a psycho-educational group session (baseline: 62.9%, 3-months: 71.4%; P = 0.63). Similarly, Wilton et al.23 found no significant group differences in self-reported HIV testing at 3 months for a group-based weekend retreat intervention. However, intervention participants had 81% greater odds of HIV testing at 6 months than comparison participants (OR = 1.81, 95% CI = 1.08–3.01, P = 0.023).

Three studies used community-engagement approaches. Berkley-Patton et al.17 delivered intervention content through multi-level church outlets, finding that HIV testing increased significantly in both the intervention (23–47%, P = 0.01) and comparison group (19–28%, P = 0.012) at 6 months. However, the intervention group who received culturally tailored content were 2.2 times more likely to have tested for HIV (OR 2.2, 95% CI [0.97–5.10], P = 0.06). Kenya et al.33 found testing with a community health worker significantly increased home-based rapid HIV testing compared with control participants testing alone (P ≤ 0.05) and significantly increased access to HIV care if positive (100% vs 83%, χ2 [1, N = 60] = 5.46, P ≤ 0.02). Seguin et al.32 reported the HIV self-sampling return rate was 55.5% (66/119, 95% CI 46.1%−64.6%) when practice nurses and community workers opportunistically distributed testing kits using a HIV rationale script.

Two studies used peer-mentoring interventions. Harawa et al.21 found no significant increase in HIV testing in participants assigned trained peer mentors. However, Frye et al.20 found that friendship pairs who did HIV self-testing together had twice the odds of reporting HIV testing in the past 3 months (OR = 2.29; 95% CI 1.15, 4.58) and almost twice the odds at 6-month follow-up (OR = 1.94; 95% CI 1.00, 3.75). Self-testing was significant at 3-month follow-up (P < 0.02) and marginally significant at 6 months (P ≤ 0.05).

Eight interventions aimed to increase adherence to antiretroviral treatment (ART).21,25–30,37 Bouris et al.26 used an intervention group to enhance social support. Intervention participants were 2.91 times more likely to have ≥90% medication adherence (95% CI: 1.10–7.71; P = 0.031) than control participants. Ma et al.29 reported that while at baseline, no participants met the 80% ART adherence criterion, after using an outreach worker to observe participants’ ART intake, 75% met the 80% adherence criterion at 3 months, and 67% met the 80% adherence criterion at 6 months. Pagan-Ortiz et al.37 found SMS adherence reminders with HIV information increased adherence after 8 weeks (baseline, 38%; 8 weeks, 86%). Guy et al.27 found no significant increase in ART adherence in a group-based intervention.

Three studies reported the use of counselling-based interventions to increase ART adherence. Bogart et al.25 found client-centred counselling increased ART adherence compared with the control group (OR = 1.30 per month, 95% CI = 1.12–1.51, P < 0.001), representing a large cumulative effect after 6 months (OR = 4.76, Cohen’s d = 0.86). Jones28 reported ART adherence increased with individual counselling, group sessions and supportive phone calls (baseline, 76%; 1 month, 100%; 3 months, 99.17%). However, the increase was not significant. Magidson et al.30 reported an increase in ART use in the intervention group (baseline, 46.9%; 12-month follow-up, 85.7%) and time-matched control group (baseline, 65.5%; 12-month follow-up, 86.7%). Across both groups, there was a significant increase in the likelihood of being on ART over time (logs odds = 0.71, P = 0.001).

Two interventions aimed to increase sexual health appointment attendance.26,27 Bouris et al.26 found the intervention group 3.01 times more likely to have had ≥three HIV primary care visits in the past 12 months (95% CI, 1.05–8.69; P = 0.04) than the control group. However, Guy et al.27 reported medical appointment attendance to decrease from pre- to post-intervention by 12.5% (P = 0.39).

Use of theory

A theoretical basis was reported for 10 interventions that aimed to increase STI/HIV testing and access to STI treatment. Six interventions which used theory were found to be effective.17,21,23,24,31,36 Berkley-Patton et al.17 reported applying the Theory of Planned Behaviour38 to increase behavioural beliefs about the importance of HIV testing, change normative beliefs, reduce stigma, and enhance perceived behavioural control. The intervention’s mode of delivery was guided by Social-Ecological Theory.39 Diallo et al.36 reported that their intervention was guided by the Health Belief Model,40 Transtheoretical Model41 and Social Cognitive Theory.42 However, how the theories were applied was not specified. Harawa et al.21 described group intervention activities as being based on Social Cognitive Theory,43 and the intervention’s peer mentors stemming from Social Impact Theory44 and Social Comparison Theory.45 Washington et al.31 reported their intervention to be informed by the Integrative Model of Behaviour Change,46,47 targeting HIV knowledge, behavioural beliefs, self-regulation skills and ability, social support, and engagement in self-management behaviour. A combination of Social Cognitive Theory,43 Behavioural Skills Acquisition Model,48 Transtheoretical Model of Behaviour Change41 and the Decisional Balance Model49 guided the development of Wilton et al.’s23 intervention. However, how the theories were implemented was not specified. Similarly, Social Cognitive Theory43 was reported to inform Wingood et al.’s24 intervention content, alongside The Theory of Gender and Power.50 Theoretically informed content sought to enhance participants’ attitudes and skills to avoid untreated STIs and educate on gender power imbalances and gender-related HIV prevention strategies.

Four ineffective interventions which aimed to increase STI/HIV testing and access to STI treatment reported behavioural theory. Chittamuru18 reported Social Cognitive Theory43 to inform intervention content. Similarly, Frye et al.19 used Social Cognitive Theory43 as a theoretical framework alongside Empowerment Theory,51 Social Identity Theory52 and Rational Choice Theory.53 The AIDS Risk Reduction Model54 was reported to guide Dolcini et al.’s34 interventions development. Seguin et al.32 reported that the Capability, Opportunity, Motivation, Behaviour Model55 was applied to identify barriers and facilitators to behaviour change.

Five studies reported a theoretical basis to interventions aiming to increase HIV treatment adherence and appointment attendance. Bogart et al.25 reported application of Social-Ecological Theory56 to address disparities at multiple levels, and Information-Motivational-Behavioural skills model57 to build treatment knowledge and adherence skills, self-efficacy, and motivation. Theories addressing multiple levels were also used by Guy et al.27 who applied Intersectionality, Social-Ecological Model56 and Social Cognitive Theory43 to target individual, interpersonal, community and structural factors to health disparities. Bouris et al.26 reported that their intervention was grounded in the Information-Motivation-Behavioural Skills model57,58 and an adapted Transtheoretical Model41 to target motivation and social factors by addressing attitudes and beliefs about stigma and HIV-specific support. The PEN-3 model (Persons, Extended family, and Neighbours; Perceptions, Enablers and Nurturers; and Positive, Existential, and Negative behaviours)59 was used by Jones28 to place culture at the centre of intervention development. Pagan-Ortiz et al.37 reported the Health Belief Model60 and Social Cognitive Theory43 as a theoretical basis to address participants’ perceived susceptibility to illness, positive beliefs and adherence, and self-efficacy.

Mode of delivery

Ten intervention formats and 10 facilitators were identified in interventions aiming to increase STI/HIV testing and access to STI treatment (Table 3). The most commonly used intervention formats in effective interventions were face-to-face group sessions (n = 5) and individual face-to-face sessions (n = 4). Other effective interventions utilised telephone (n = 3), videos (n = 2), SMS messages (n = 1), resource material (n = 1), posters (n = 1), church bulletins (n = 1), and letters (n = 1).

| Intervention format | Intervention facilitator | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Berkley-Patton et al.17 A | Face-to-face sessions (individual and group), posters, church bulletins, telephone, SMS messages, videos | Church pastor, digital | |

| Chittamuru et al.18 | Video | Digital | |

| Diallo et al.36 B | Face-to-face sessions (group) | Trained facilitator (Black ethnicity, female) | |

| Dolcini et al.34 | Face-to-face sessions (group) | Health educator (African American, female) | |

| Frye et al.19 | Face-to-face sessions (group) | Trained facilitators (African American, male) | |

| Frye et al.20 B | Face-to-face sessions (individual) | Peer educators | |

| Harawa et al.21 A | Face-to-face sessions (individual and group) | Peer mentors (Black, MSM) | |

| Jones et al.22 B | Telephone, letters | Screening and treatment program staff, digital, printed material | |

| Kenya et al.33 B | Face-to-face sessions (individual), telephone | Community health worker, digital | |

| Sánchez et al.35 | Resource material, emails, face-to-face sessions (group and individual) | Venue staff, venue promoters, outreach staff, printed material, digital | |

| Seguin et al.32 | Face-to-face sessions (individual), SMS message | Practice nurses, community workers, digital | |

| Washington et al.31 B | Videos | Digital, actors (Black, MSM) | |

| Wilton et al.23 B | Face-to-face sessions (group) | Trained peers (Black, MSM) | |

| Wingood et al.24 B | Face-to-face sessions (group) | Health educators (African American, female) |

The most frequently used intervention facilitators in effective interventions were digital (n = 4), peers (n = 3) and printed material (n = 2). The following facilitators were used once: trained facilitators, health educators, church pastors, church health liaisons, screening and treatment program staff, community health worker, community workers and actors.

Six intervention formats and eight facilitators were identified for interventions aiming to increase HIV treatment adherence and appointment attendance (Table 4). The most reported intervention formats in effective interventions were individual face-to-face sessions (n = 3), group face-to-face sessions (n = 2) and booklets (n = 1).

| Intervention format | Intervention facilitator | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Bogart et al.25 A | Face-to-face sessions (individual and group) | Counsellors (Black ethnicity) | |

| Bouris et al.26 A | Face-to-face sessions (individual and group) | Social worker interventionist | |

| Guy et al.27 | Face-to-face sessions (group) | Intervention facilitators (African American, living with HIV and serious mental illness) | |

| Jones28 | Face-to-face sessions (individual and group), telephone, treatment manuals | Clinician facilitators, digital, printed material | |

| Ma et al.29 | Face-to-face sessions (individual), telephone | Outreach worker (African American, female, from local community), digital | |

| Magidson et al.30 B | Face-to-face sessions (individual), booklets | Trained therapists, printed material | |

| Pagan-Ortiz et al.37 | SMS messages | Digital |

Intervention facilitators used in effective interventions included counsellors (n = 1), social worker interventionist (n = 1), trained therapist (n = 1) and printed material (n = 1).

Behaviour change techniques

A total of 26 novel BCTs were identified (Table 5). The number of BCTs within each intervention ranged from two to 13 (mean, 6.6). The most commonly observed BCTs across all interventions aiming to increase STI/HIV testing and access to STI treatment were information about health consequences (n = 13), instruction on how to perform behaviour (n = 9), framing/reframing (n = 7) and demonstration of the behaviour (n = 7).

| Group | BCT identified | Berkley- Patton et al.17 A | Chittamuru18 | Diallo et al.36 B | Dolcini et al.34 | Frye et al.19 | Frye et al.20 B | Harawa et al.21 A | Jones et al.22 B | Kenya et al.33 B | Sánchez et al.35 | Seguin et al.32 | Washington et al.31 B | Wilton et al.23 B | Wingood et al.24 B | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1: Goals and planning | 1.1 Goal setting (behaviour) | |||||||||||||||

| 1.2 Problem solving | ||||||||||||||||

| 1.4 Action planning | ||||||||||||||||

| 1.5 Review behaviour goal(s) | ||||||||||||||||

| 1.9 Commitment | ||||||||||||||||

| Group 2: Feedback and monitoring | 2.2 Feedback on behaviour | |||||||||||||||

| Group 3: Social support | 3.1 Social support (unspecified) | |||||||||||||||

| Group 4: Shaping knowledge | 4.1 Instruction on how to perform behaviour | |||||||||||||||

| 4.2 Information about antecedents | ||||||||||||||||

| Group 5: Natural consequences | 5.1 Information about health consequences | |||||||||||||||

| 5.3 Information about social and environmental consequences | ||||||||||||||||

| Group 6: Comparison of behaviour | 6.1 Demonstration of the behaviour | |||||||||||||||

| 6.2 Social comparison | ||||||||||||||||

| 6.3 Information about others’ approval | ||||||||||||||||

| Group 7: Associations | 7.1 Prompts/cues | |||||||||||||||

| Group 8: Repetition and substitution | 8.1 Behavioural practice/rehearsal | |||||||||||||||

| Group 9: Comparison of outcomes | 9.1 Credible source | |||||||||||||||

| 9.2 Pros and cons | ||||||||||||||||

| Group 10: Reward and threat | 10.1 Material incentive (behaviour) | |||||||||||||||

| 10.2 Material reward (behaviour) | ||||||||||||||||

| 10.6 Non-specific incentive | ||||||||||||||||

| Group 11: Regulation | 11.2 Reduce negative emotions | |||||||||||||||

| Group 12: Antecedents | 12.1 Restructuring the physical environment | |||||||||||||||

| 12.2 Restructuring the social environment | ||||||||||||||||

| Group 13: Identity | 13.2 Framing/reframing | |||||||||||||||

| Group 15: Self-belief | 15.1 Verbal persuasion about capability | |||||||||||||||

| Total BCTs used | 6 | 5 | 8 | 10 | 10 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 9 | 6 | 13 | 5 |

Within the nine interventions found to significantly increase STI/HIV testing and access to STI treatment within the intervention group, observed BCTs ranged from 2 to 13 (mean, 6). Commonly observed BCTs included information about health consequences (n = 8), instruction on how to perform behaviour (n = 6), information about social and environmental consequences (n = 4), and framing/reframing (n = 4). The following BCTs were solely used in effective interventions: goal setting (behaviour); review behaviour goal(s); information about social and environmental consequences; social comparison, reduce negative emotions; and restructuring the social environment.

Five interventions did not report a significant increase in their intervention group. The BCTs reported within these interventions ranged from 5 to 10 (mean, 7.8). The most observed BCTs were information about health consequences (n = 5) and demonstration of the behaviour (n = 4). Asking individuals to commit to behaviour change was the only BCT used solely in an intervention that did not report a significant increase in their intervention group.

A total of 31 novel BCTs were observed (Table 6). The number of BCTs reported ranged from 4 to 14 (mean, 9.6). The most commonly reported BCTs across all interventions aiming to increase HIV treatment adherence and appointment attendance were problem solving (n = 6), information about health consequences (n = 6), restructuring the social environment (n = 4), information about social and environmental consequences (n = 4), and review behavioural goal(s) (n = 4).

| Group | BCT identified | Bogart et al.25 A | Bouris et al.26 A | Guy et al.27 | Jones28 | Ma et al.29 | Magidson et al.30 B | Pagan-Ortiz et al.37 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1: Goals and planning | 1.1 Goal setting (behaviour) | ||||||||

| 1.2 Problem solving | |||||||||

| 1.4 Action planning | |||||||||

| 1.5 Review behaviour goal(s) | |||||||||

| 1.6 Discrepancy between current behaviour and goal | |||||||||

| 1.7 Review outcome goal(s) | |||||||||

| 1.8 Behavioural contract | |||||||||

| Group 2: Feedback and monitoring | 2.1 Monitoring of behaviour by others without feedback | ||||||||

| 2.3 Self-monitoring of the behaviour | |||||||||

| 2.5 Monitoring of outcome(s) of behaviour without behaviour | |||||||||

| 2.7 Feedback on outcome(s) of behaviour | |||||||||

| Group 3: Social support | 3.1 Social support (unspecified) | ||||||||

| 3.2 Social support (practical) | |||||||||

| Group 4: Shaping knowledge | 4.2 Information about antecedents | ||||||||

| Group 5: Natural consequences | 5.1 Information about health consequences | ||||||||

| 5.3 Information about social and environmental consequences | |||||||||

| Group 6: Comparison of behaviour | 6.1 Demonstration of behaviour | ||||||||

| 6.2 Social comparison | |||||||||

| Group 7: Associations | 7.1 Prompts/cues | ||||||||

| Group 8: Repetition and substitution | 8.1 Behavioural practice/rehearsal | ||||||||

| 8.3 Habit formation | |||||||||

| Group 9: Comparison of outcomes | 9.2 Pros and cons | ||||||||

| Group 10: Reward and threat | 10.3 Non-specific reward | ||||||||

| Group 11: Regulation | 11.1 Pharmacological support | ||||||||

| 11.2 Reduce negative emotions | |||||||||

| Group 12: Antecedents | 12.1 Restructuring the physical environment | ||||||||

| 12.2 Restructuring the social environment | |||||||||

| Group 13: Identity | 13.2 Framing/reframing | ||||||||

| 13.4 Valued self-identity | |||||||||

| Group 15: Self-belief | 15.1 Verbal persuasion about capability | ||||||||

| 15.3 Focus on past success | |||||||||

| Total BCTs used | 14 | 8 | 14 | 13 | 6 | 8 | 4 |

Within three intervention groups found to significantly increase adherence to HIV treatment and appointment attendance, observed BCTs ranged from 8 to 14 (mean, 10). The most frequently used BCT in the effective intervention groups was information about health consequences (n = 3), problem solving (n = 2), information about social and environmental consequences (n = 2), and review behavioural goal(s) (n = 2). The following BCTs were only used once and within effective interventions: discrepancy between current behaviour and goal; review outcome goal(s); behavioural contract; self-monitoring of the behaviour; feedback on outcome(s) of behaviour; habit formation; pros and cons; and non-specific reward.

Four interventions were reported not to be effective, in which the BCTs identified ranged from 4 to 14 (mean, 9.25). The most commonly identified BCTs within these interventions were problem solving (n = 4), information about health consequences (n = 3), goal setting (behaviour) (n = 3), and restructuring the social environment (n = 3). The following BCTs were only used once and within interventions not found to be effective: monitoring of behaviour by others without feedback; monitoring of outcome(s) of behaviour without behaviour; social support (unspecified); social support (practical); demonstration of behaviour, social comparison; pharmacological support; and focus on past success.

Discussion

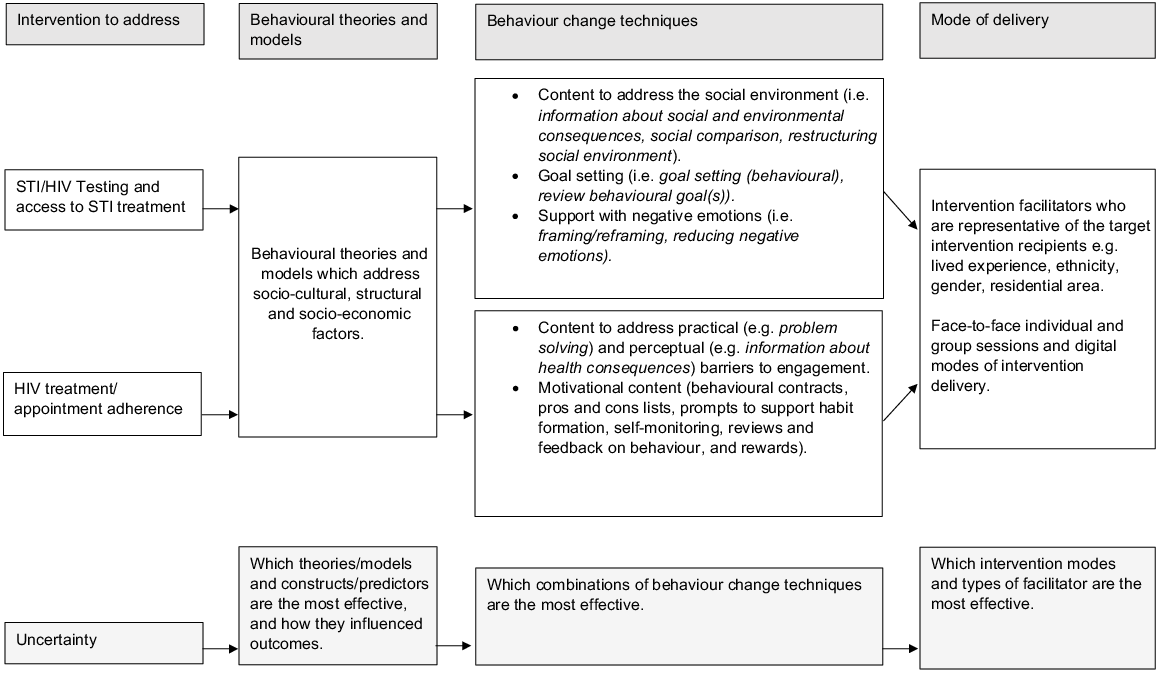

This review identified 21 interventions designed to increase engagement with sexual healthcare in Black ethnic groups. Some behavioural interventions were found to increase STI/HIV testing, access to STI treatment, ART adherence and attendance at sexual healthcare appointments. Fifteen interventions were underpinned by behavioural theory, with 39 BCTs identified across the included interventions. Social Cognitive Theory43 and the Transtheoretical Model of Behaviour Change41 were the most frequently used behavioural theories. Interventions were delivered in 12 different intervention formats. Intervention facilitators were frequently reported to be being of Black ethnicity or to have similar life experiences as intervention recipients. The most frequently utilised novel BCTs in interventions found to significantly increase STI/HIV testing and access to STI treatment were information about health consequences, instruction on how to perform behaviour, information about social and environmental consequences and framing/reframing. In the interventions found to significantly increase adherence to HIV treatment and appointment attendance, the most commonly identified novel BCTs were information about health consequences, problem solving, information about social and environmental consequences and review behavioural goal(s). A summary of components identified in effective interventions and where uncertainty remains has been included in Fig. 2.

Fifteen of the included interventions reported behavioural theory. This finding contrasts with previous suggestions that there is limited theoretical underpinning for sexual health clinic attendance interventions.61 However, studies in the present review were often unclear on how theory had informed intervention design, content or delivery. Thus, identifying patterns in how theory may influence intervention outcomes remains challenging. Nevertheless, the use of theory supports suggestions that sexual health disparities for Black individuals are driven by differences in sociocultural, structural and socio-economic factors.5,6,9 For example, restructuring environments to include pastors’ modelling HIV testing,17 client-centred counselling to address medical mistrust,25 and education on partner selection and the economic impact of pregnancy.24 This approach follows Medical Research Council guidance62 to consider how theory interacts with contextual factors within intervention development. More detailed reporting of intervention design, implementation and theory evaluation in future interventions will help to develop understanding of how theory can guide behaviour change in the context of sexual health.

While the present review demonstrates that a variety of intervention delivery modes can be used, interventions frequently matched the demographics and lived experience of the intervention facilitator with that of the intervention recipients. Matching the ethnicity or gender of intervention facilitators has previously increased effectiveness and improved patient experience within health care services.63,64 Moreover, existing literature indicates that interventions with facilitators who are representative of the recipients have good acceptability and fidelity.65 Peer delivery of sexual health interventions have previously been more effective than expert delivery.63 In addition, an African American sample have reported shared life experiences and sufficient trust can make discussing sexual health easier.56 Thus, future intervention facilitators must represent intervention recipients and deliver trustworthy messages.66 When identifying, engaging and collaborating with such stakeholders, it is essential to acknowledge stakeholders’ expertise, clarify roles and responsibilities, ensure visible representation among the team, and to establish trust.4 Creating partnerships with local organisations, demonstrating a commitment to benefit local communities, and involving local community members in designing and delivering sexual health promotion and interventions are encouraged.4,65,66 Collaborative intervention design may improve future intervention fidelity, reduce prejudices and bias, and ensure that interventions are delivered using culturally appropriate venues and modes.10 In line with the findings of this research, digital modes of intervention delivery and social media have previously been recommended due to their influence.10

The most commonly reported novel BCTs in interventions found to increase STI/HIV testing and access to STI treatment were information about health consequences, instruction on how to perform the behaviour, framing/reframing and information about social and environmental consequences. Providing information about health consequences is frequently used in sexual health interventions62 but we found that its use was not strongly associated with effectiveness. Moreover, instruction on how to perform the behaviour and framing/reframing were also identified in ineffective interventions, suggesting that different BCT combinations may have mediated outcomes. In particular, the seven BCTs solely used in effective interventions may have influenced outcomes. Addressing the social environment, setting and reviewing goals, rewarding achievements and managing negative emotions may have helped enable personalised support for individual participant barriers20,21 and challenged community narratives about sexual health and relationship dynamics.17,19,21,27,32 Consequently, this may have enabled person- and community-centred support for sexual healthcare barriers.11 Nevertheless, ongoing engagement with Black communities is of utmost importance to ensure tailored sexual health interventions are culturally relevant, acceptable and engaging.10,66

Frequently identified novel BCTs in interventions found to increase HIV treatment adherence and appointment attendance were problem solving, information about health consequences, information about social and environmental consequences and reviewing behavioural goals. These BCTs reflect theories indicating a need to address both practical (e.g. problem solving) and perceptual barriers (e.g. information about health consequences) to treatment and appointment attendance.67 Nevertheless, as these frequently identified BCTs were in both effective and ineffective interventions further consideration must be given to the other BCTs used alongside them. Eight further BCTs solely used in effective interventions targeted individuals’ motivation for behaviour change55 with behavioural contracts, pros and cons lists, prompts to support habit formation, self-monitoring, reviews and feedback on behaviour, and rewards. Thus, interventions to increase ART adherence and HIV appointment attendance in those with Black ethnicity, may benefit from frameworks that address an individual’s capability (e.g. information about health consequences), opportunity (e.g. problem solving) and motivation (e.g. rewards, feedback, prompts supporting habit formation).55 Moreover, it has been recommended that sexual health promotion for individuals from a Black ethnic background needs to be informative (capability), address sexual health myths (opportunity) and use incentives (motivation).10,66 Nevertheless, testing the effectiveness of specific frameworks and BCT combinations should be a priority for future research.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first systematic review of interventions which aim to support engagement with sexual health services and treatment in Black ethnic groups. The review thus provides valuable insight into how future interventions can be optimised to improve sexual health outcomes in individuals of Black ethnicity and reduce health inequalities. Nevertheless, this review was limited by heterogeneity in the identified intervention aims, outcome measures, inclusion criteria, sample sizes and follow-up durations. Such variation renders it impossible to conduct more complex analyses and creates challenges in comparing studies. Second, not all studies included a comparison group or pre-test data and, in some cases, BCTs were also identified in comparison groups.22,33 Consequently, caution is required when interpreting the effectiveness of some interventions and BCTs. Third, additional intervention studies that aimed to increase engagement with sexual healthcare in Black participants were excluded because data were not reported separately for individual ethnic groups or because of uncertainty about included participant ethnicities (e.g. ‘Other’ ethnicities). Finally, identifying and understanding the application of behavioural theory and BCTs was challenged by sub-optimal reporting of intervention characteristics. Theory and BCTs were only coded when they could be explicitly identified. Although available intervention protocols were reviewed, it is possible that additional intervention characteristics may not have been reported. The use of reporting guidelines, such as the GUIDED checklist,68 or the availability of more open-access intervention protocols, will help aid the future assessment of intervention components and their effectiveness. Reporting interventions using standardised terminology will support identification of intervention components and facilitate comparison across interventions. The release of the Behaviour Change Technique Taxonomy 2 with additional techniques and further distinction between techniques may help identification and comparison of intervention components.69

Conclusion

This review provides additional insight into how behavioural interventions can increase engagement with sexual healthcare among individuals of Black ethnicity. Findings highlight the importance of considering sociocultural, structural and socio-economic barriers to engaging with sexual healthcare when providing content to modify health-seeking behaviours. Educational interventions can be optimised by including components to strengthen individuals’ opportunities and motivation to engage in behaviour change. Intervention facilitators should represent the target community, and steps should be taken to enhance recipients’ trust in intervention providers. Future sexual health intervention research in this area would benefit from examining the effectiveness of various BCT combinations.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of interest

Jonathan Ross reports personal fees from GSK Pharma and Bayer Consumer Care; ownership of shares in GSK Pharma and AstraZeneca Pharma; lead author of the UK and European Guidelines on Pelvic Inflammatory Disease; Member of the European Sexually Transmitted Infections Guidelines Editorial Board; NIHR Journals Editor and associate editor of Sexually Transmitted Infections journal; treasurer for the International Union against Sexually Transmitted Infections and chair of charity trustees for the Sexually Transmitted Infections Research Foundation. The other authors report no conflicts of interest.

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust.

References

1 Public Health England. Sexually transmitted infections and screening for chlamydia in England: 2022 report; 2022. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/sexually-transmitted-infections-stis-annual-data-tables/sexually-transmitted-infections-and-screening-for-chlamydia-in-england-2022-report [accessed 31 July 2022]

2 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health disparities in HIV, Viral Hepatitis, STDs and TB; 2020. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/healthdisparities/africanamericans.html [accessed 31 July 2023]

3 Public Health England. Health promotion for sexual and reproductive health and HIV; 2015. Available at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/488090/SRHandHIVStrategicPlan_211215.pdf [accessed 2 June 2022]

4 Woode Owusu M, Estupiñán Fdez. de Mesa M, Mohammed H, Gerressu M, Hughes G, Mercer CH. Race to address sexual health inequalities among people of Black Caribbean heritage: could co-production lead to more culturally appropriate guidance and practice? Sex Transm Infect 2023; 99(5): 293-295.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

5 Wayal S, Gerressu M, Weatherburn P, Gilbart V, Hughes G, Mercer CH. A qualitative study of attitudes towards, typologies, and drivers of concurrent partnerships among people of black Caribbean ethnicity in England and their implications for STI prevention. BMC Public Health 2020; 20(1): 188.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

6 Briscoe-Palmer S. Are you listening? Black voices on contraception choice and access to services; 2022. Available at https://www.fsrh.org/blogs/are-you-listening-black-voices-on-contraception-choice/ [accessed 5 April 2022]

7 Cohn T, Harrison CV. A systematic review exploring racial disparities, social determinants of health, and sexually transmitted infections in Black women. Nurs Womens Health 2022; 26(2): 128-142.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

8 Eaton LA, Driffin DD, Kegler C, Smith H, Conway-Washington C, White D, Cherry C. The role of stigma and medical mistrust in the routine health care engagement of Black men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health 2015; 105(2): e75-e82.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

9 The State of the Nation. Sexually transmitted infections in England; 2020. Available at https://www.tht.org.uk/sites/default/files/2020-02/State%20of%20the%20nation%20report%20v2.pdf [accessed 1 August 2022]

10 Boutrin M-C, Williams DR. What racism has to do with it: understanding and reducing sexually transmitted diseases in youth of color. Healthcare 2021; 9: 673.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

11 Evans R, Widman L, Stokes MN, Javidi H, Hope EC, Brasileiro J. Association of sexual health interventions with sexual health outcomes in black adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr 2020; 174(7): 676-689.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

12 Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021; 372: n71.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

13 Methley AM, Campbell S, Chew-Graham C, McNally R, Cheraghi-Sohi S. PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: a comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv Res 2014; 14: 579.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

14 Webb TL, Sheeran P. Does changing behavioral intentions engender behavior change? A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence. Psychol Bull 2006; 132(2): 249-268.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

15 Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, Abraham C, Francis J, Hardeman W, Eccles MP, Cane J, Wood CE. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med 2013; 46(1): 81-95.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

16 Pluye P, Gagnon M-P, Griffiths F, Johnson-Lafleur J. A scoring system for appraising mixed methods research, and concomitantly appraising qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods primary studies in Mixed Studies Reviews. Int J Nurs Stud 2009; 46: 529-546.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

17 Berkley-Patton J, Thompson CB, Moore E, Hawes S, Simon S, Goggin K, Martinez D, Berman M, Booker A. An HIV testing intervention in African American churches: pilot study findings. Ann Behav Med 2016; 50(3): 480-485.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

19 Frye V, Henny K, Bonner S, Williams K, Bond KT, Hoover DR, Lucy D, Greene E, Koblin BA, for the Straight Talk Study Team. “Straight Talk” for African-American heterosexual men: results of a single-arm behavioral intervention trial. AIDS Care 2013; 25(5): 627-631.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

20 Frye V, Nandi V, Paige MQ, McCrossin J, Lucy D, Gwadz M, Sullivan PS, Hoover DR, Wilton L, for the Trust Study Team. Trust: assessing the efficacy of an intervention to increase HIV self-testing among young Black men who have sex with men (MSM) and transwomen. AIDS Behav 2021; 25(4): 1219-1235.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

21 Harawa NT, Schrode KM, McWells C, Weiss RE, Hilliard CL, Bluthenthal RN. Small randomized controlled trial of the new passport to wellness HIV prevention intervention for black men who have sex with men (BMSM). AIDS Educ Prev 2020; 32(4): 311-324.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

22 Jones AT, Craig-Kuhn MC, Schmidt N, Gomes G, Scott G, Watson S, Hines P, Davis J, Lederer AM, Martin DH, Kissinger PJ. Adapting index/partner services for the treatment of chlamydia among young African American men in a community screening program. Sex Transm Dis 2021; 48(5): 323-328.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

23 Wilton L, Herbst JH, Coury-Doniger P, Painter TM, English G, Alvarez ME, Scahill M, Roberson MA, Lucas B, Johnson WD, Carey JW. Efficacy of an HIV/STI prevention intervention for Black men who have sex with men: findings from the Many Men, Many Voices (3MV) Project. AIDS Behav 2009; 13(3): 532-544.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

24 Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ, Robinson-Simpson L, Lang DL, Caliendo A, Hardin JW. Efficacy of an HIV intervention in reducing high-risk human papillomavirus, nonviral sexually transmitted infections, and concurrency among African American women: a randomized-controlled trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2013; 63: S36-S43.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

25 Bogart LM, Mutchler MG, McDavitt B, Klein DJ, Cunningham WE, Goggin KJ, Ghosh-Dastidar B, Rachal N, Nogg KA, Wagner GJ. A randomized controlled trial of rise, a community-based culturally congruent adherence intervention for Black Americans living with HIV. Ann Behav Med 2017; 51(6): 868-878.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

26 Bouris A, Jaffe K, Eavou R, Liao C, Kuhns L, Voisin D, Schneider JA. Project nGage: results of a randomized controlled trial of a dyadic network support intervention to retain young Black men who have sex with men in HIV care. AIDS Behav 2017; 21(12): 3618-3629.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

27 Guy AA, Du Bois SN, Thomas N, Noble S, Lewis R, Toles J, Spivey CL, Yoder W, Ramos SD, Woodward H. Engaging African Americans living with HIV and serious mental illness: piloting Prepare2Thrive – a peer-led intervention. Prog Community Health Partnersh 2020; 14: 413-429.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

29 Ma M, Brown BR, Coleman M, Kibler JL, Loewenthal H, Mitty JA. The feasibility of modified directly observed therapy for HIV-Seropositive African American substance users. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2008; 22(2): 139-146.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

30 Magidson JF, Belus JM, Seitz-Brown CJ, Tralka H, Safren SA, Daughters SB. Act Healthy: a randomized clinical trial evaluating a behavioral activation intervention to address substance use and medication adherence among low-income, Black/African American individuals living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Behav 2022; 26(1): 102-115.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

31 Washington TA, Applewhite S, Glenn W. Using Facebook as a platform to direct young Black men who have sex with men to a video-based HIV testing intervention: a feasibility study. Urban Soc Work 2017; 1(1): 36-52.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

32 Seguin M, Dodds C, Mugweni E, McDaid L, Flowers P, Wayal S, Zomer E, Weatherburn P, Fakoya I, Hartney T, McDonagh L, Hunter R, Young I, Khan S, Freemantle N, Chwaula J, Sachikonye M, Anderson J, Singh S, Nastouli E, Rait G, Burns F. Self-sampling kits to increase HIV testing among Black Africans in the UK: the HAUS mixed-methods study. Health Technol Assess 2018; 22(22): 1-158.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

33 Kenya S, Okoro IS, Wallace K, Ricciardi M, Carrasquillo O, Prado G. Can home-based HIV rapid testing reduce HIV disparities among African Americans in Miami? Home Promot Pract 2016; 17(5): 722-730.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

34 Dolcini MM, Harper GW, Boyer CB, Pollack LM. Project ÒRÊ: a friendship-based intervention to prevent HIV/STI in urban African American adolescent females. Health Educ Behav 2010; 37(1): 115-132.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

35 Sánchez JP, Lowe C, Freeman M, Burton W, Sánchez NF, Beil R. A syphilis control intervention targeting Black and Hispanic men who have sex with men. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2009; 20: 194-209.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

36 Diallo DD, More TW, Ngalame PM, White LD, Herbst JH, Painter TM. Efficacy of a single-sessino HIV prevention intervention for black women: a group randomized controlled trial. AIDs Behav 2010; 14: 518-529.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

37 Pagan-Ortiz ME, Goulet P, Kogelman L, Levkoff SE, Weitzman PF. Feasibility of a texting intervention to improve medication adherence among older HIV+ African Americans: a mixed-method pilot study. Gerontol Geriatr Med 2019; 5: 2333721419855662.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

38 Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Human Decis Process 1991; 50(2): 179-211.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

40 Becker MH. The health belief model and sick role behavior. Health Educ Behav 1974; 2(4): 409-419.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

41 Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Health Promot 1997; 12(1): 38-48.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

42 Bandura A. Social cognitive theory in cultural context. Appl Psychol 2002; 51: 269-290.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

44 Nowak A, Szamrej J, Latané B. From private attitude to public opinion: a dynamic theory of social impact. Psychol Rev 1990; 97(3): 362-376.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

45 Festinger L. A theory of social comparison processes. Hum Relat 1954; 7: 117-140.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

47 Fishbein M, Hennessy M, Kamb M, et al. Using intervention theory to model factors influencing behavior change. Eval Health Prof 2001; 24(4): 363-384.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

50 Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. Application of the theory of gender and power to examine HIV-related exposures, risk factors, and effective interventions for women. Health Educ Behav 2000; 27(5): 539-565.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

51 Zimmerman MA. Psychological empowerment: issues and illustration. Am J Community Psychol 1995; 23: 581-599.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

53 Hechter M, Kanazawa S. Sociological rational choice theory. Ann Rev Sociol 1997; 23: 191-214.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

54 Catania JA, Kegeles SM, Coates TJ. Towards an understanding of risk behaviour: an AIDS risk reduction model (ARRM). Heath Educ Q 1990; 17(1): 53-72.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

55 Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci 2011; 6: 42.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

56 Kaufman MR, Cornish F, Zimmerman RS, Johnson BT. Health behavior change models for HIV prevention and AIDS care: practical recommendations for a multi-level approach. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2014; 66: S250-S258.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

57 Starace F, Massa A, Amico KR, Fisher JD. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy: an empirical test of the information-motivation-behavioral skills model. Health Psychol 2006; 25(2): 153-162.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

58 Fisher JD, Fisher WA, Amico KR, Harman JJ. An information-motivation-behavioral skills model of adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Health Psychol 2006; 25(4): 462-473.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

59 Airhihenbuwa CO. Health education for African Americans: a neglected task. Health Educ 1989; 20: 9-14.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

60 Rosenstock IM. Historical origins of the health belief model. Health Educ Monogr 1974; 2: 328-335.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

61 Clarke R, Heath G, Ross JDC, Farrow C. Increasing attendance at pre-booked sexual health consultations: a systematic review. Sex Health 2022; 19: 236-247.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

62 Skivington K, Matthews L, Simpson SA, Craig P, Baird J, Blazeby JM, Boyd KA, Craig N, French DP, McIntosh E, Petticrew M, Rycroft-Malone J, White M, Moore L. A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: update of Medical Research Council Guidance. BMJ 2021; 374: n2061.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

63 Covey J, Rosenthal-Stott HES, Howell SJ. A synthesis of meta-analytic evidence of behavioral interventions to reduce HIV/STIs. J Behav Med 2016; 39: 371-385.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

64 Takeshita J, Wang S, Loren AW, Mitra N, Shults J, Shin DB, Sawinski DL. Association of racial/ethnic and gender concordance between patients and physicians with patient experience rating. JAMA Netw Open 2020; 3(11): e2024583.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

65 Mitchell KR, Purcell C, Forsyth R, Barry S, Hunter R, Simpson SA, McDaid L, Elliot L, McCann M, Wetherall K, Broccatelli C, Bailey JV, Moore L. A peer-led intervention to promote sexual health in secondary schools: the STASH feasibility study. Public Health Res 2020; 8(15):.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

66 Public Health England. Sexually transmitted infections: promoting the sexual health and wellbeing of people from a Black Caribbean background; 2021. Available at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1021488/HPRU1_BC_PHE_UCL_Report.pdf [accessed 10 August 2022]

68 Duncan E, O’Cathain A, Rousseau N, Croot L, Sworn K, Turner KM, Yardley L, Hoddinott P. Guidance for reporting intervention development studies in health research (GUIDED): an evidence-based consensus study. BMJ Open 2020; 10: e033516.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

69 Wood CE, Richardson M, Johnston M, Abraham C, Francis J, Hardeman W, Michie S. Applying the behaviour change technique (BCT) taxonomy v1: a study of coder training. Transl Behav Med 2015; 5(2): 134-148.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |