Assessing and projecting the global impacts of female infertility: a 1990–2040 analysis from the Global Burden of Disease study

Hanjin Wang A # and Bengui Jiang A # *

A # *

A

# These authors contributed equally to this paper

Handling Editor: Ian Simms

Abstract

This study aims to assess the global burden of female infertility from 1990 to 2040.

Data on disability-adjusted life years associated with female infertility were sourced from the Global Burden of Disease 2021 study. Generalized additive models were utilized to predict trends for the period spanning from 2022 to 2040.

The global burden of female infertility is expected to increase significantly, with the age-standardized disability-adjusted life year rate projected to reach 19.92 (95% uncertainty interval (UI): 18.52, 21.33) by 2040. The projected estimated annual percentage change (EAPC) for the age-standardized disability-adjusted life year rate from 2022 to 2040 is expected to be 1.42, with a 95% confidence interval (CI) of 1.3951–1.4418. This is in contrast to the EAPC of 0.71 (95% CI: 0.5391–0.8789) observed from 1990 to 2021. Central sub-Saharan Africa is projected to have the highest age-standardized rate at 29.37 (95% UI: 24.58–34.16), whereas Australasia is expected to have the lowest at 0.78 (95% UI: 0.72–0.84). Age-specific projections show a consistent decline in infertility rates across all age groups. Countries such as Kenya, Chad and Peru exhibit EAPCs exceeding 9.00, whereas Mali and South Africa show significant negative EAPCs. Correlation analysis indicates that regions with a higher sociodemographic index generally have lower female infertility burdens, with notable trends observed in Europe and Asia.

The projected global burden of female infertility is expected to increase significantly from 2021 to 2040, with notable regional disparities. Central sub-Saharan Africa and south Asia are anticipated to experience higher burdens, whereas overall rates are projected to decrease across different age groups.

Keywords: age-standardized rates, disability-adjusted life years, estimated annual percentage change, female infertility, global burden of disease, prediction, reproductive health, sociodemographic index (SDI).

Introduction

Female infertility is a significant global health concern affecting numerous women and placing substantial strain on healthcare systems.1 It is defined by the inability to conceive after 12 months of consistent, unprotected intercourse, and can be attributed to various physiological, hormonal and anatomical factors.2 Approximately one in six individuals of reproductive age globally experience infertility in their lifetime.3 Internationally, an estimated 12% of married women encounter female infertility.4 A meta-analysis indicated the overall combined prevalence to be 46.25% and 51.5% for infertility and primary infertility, respectively.5 Beyond its physical implications, female infertility has profound psychological, social and economic effects, impacting not only individuals, but also their families’ overall well-being.6 Presently, there is a marked trend toward sustained low fertility in most regions of the world.7 This trend will be further exacerbated by female infertility. The consequences of lower fertility rates are wide-ranging, encompassing demographic, economic, geopolitical, food security, health and other areas. Clearly, additional research into the factors influencing female infertility and future trends is essential to mitigate the extensive adverse effects of this condition.

The high incidence of female infertility can be attributed to a multitude of risk factors, which include advanced maternal age, obesity, smoking, excessive alcohol consumption, stress and exposure to environmental toxins.8 Furthermore, underlying medical conditions, such as polycystic ovary syndrome, endometriosis and tubal blockages, significantly contribute to infertility. Despite the known risk factors, numerous aspects of female infertility remain unexplored, particularly its prevalence and impact on various sociodemographic groups and geographic regions.9 Presently, there is a paucity of research on the burden of female infertility and future trend projections. Therefore, utilizing up-to-date data to estimate the current status and future trends of female infertility globally would greatly benefit the management of this issue worldwide.

This study utilizes data from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2021 study to provide a detailed analysis of the burden of female infertility from 1990 to 2021, with projections through 2040, and by examining age-standardized rates (ASR) and estimated annual percentage changes (EAPC) for disability-adjusted life years (DALYs). Additionally, the study employs generalized additive models to estimate and predict future trends, and investigates the relationship between the sociodemographic index (SDI) and female infertility burden. This study leverages the most recent data from the GBD to present a comprehensive examination of global trends in female infertility. The objective is to elucidate the patterns and distribution of the global female infertility burden, thereby providing critical insights for the management of female infertility worldwide.

Methods

Data sources

Comprehensive prevalence data on female infertility from 1990 to 2021 were collected from the Global Health Data Exchange platform’s GBD tool, which encompasses 204 countries and territories. The Global Health Data Exchange serves as a vast repository of health-related data, drawing information from surveys, censuses and vital statistics. The 2021 GBD study integrated all available epidemiological data, implemented updated standard operating procedures and conducted a thorough assessment of health loss.10 Analyzing 369 diseases and injuries alongside 87 risk factors across these 204 countries and territories, the study retrieved female infertility data from the GBD online database, stratified by gender (male, female, combined), and adjusted for various age groups through age-standardization.10 Previous research has provided comprehensive insights into the data privacy and ethical considerations outlined in GBD 2021.10 In alignment with the Guidelines for Accurate and Transparent Health Estimates Reporting statement,10 GBD 2021 ensures compliance.

The GBD study used the Cause of Death Ensemble model to estimate mortality rates across various locations and time periods. In cases where data were scarce, the 2021 GBD study also utilized DisMod-MR 2.1, a Bayesian meta-regression tool, to ensure consistency in disease burden estimates.10

The GBD’s SDI is a comprehensive measure that considers per capita income, education level and fertility rate. This index ranges from 0 to 1, with higher scores indicating regions with higher per capita income, more extensive education and lower fertility rates. Countries were categorized into five groups – high, upper-middle, middle, lower-middle and low development levels – based on their SDI scores. As the data used in this study are publicly accessible, ethical approval was deemed unnecessary.

The International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes for female infertility are comprehensive, covering a wide range of conditions. In the ninth revision (ICD-9), codes 628.0–628.9 encompass anovulation (628.0), other specified forms of female infertility (628.8) and unspecified female infertility (628.9).11,12 The 10th revision (ICD-10) further elaborates on this, with codes ranging from N97.0 to N97.9, addressing female infertility associated with anovulation (N97.0), tubal infertility (N97.1), uterine infertility (N97.2), other forms of female infertility (N97.8) and unspecified female infertility (N97.9).11–13 These codes establish a comprehensive classification system for the diagnosis of infertility in females across all age groups.

Statistical analysis

This study analyzed data from the GBD study to examine the burden of female infertility between 1990 and 2021, and projected trends up to 2040. ASR for DALYs were calculated to evaluate the impact across different age groups. The ASR was determined by computing a weighted average of specific rates for each age group, with the standard population serving as the weighting factor. The mathematical expression for ASR can be found in the article by Wang et al:14

where wi represents the standard population weight for each age group, and ri denotes the rate (DALY) for that age group.14

The standard population weights are calculated as:

where Pi is the population of its age group in the standard population.

Generalized additive models were used to examine the nonlinear relationship between time and age-standardized rates of female infertility. This methodology allowed for the exploration of disease trends over time, utilizing adaptable functions to account for fluctuations in predictor variables such as calendar year and median age. The model was illustrated as:15

where y represents the predicted age-standardized rates, β0 is the intercept, sn(xn) is a smooth function representing the nonlinear relationship with predictor variables and denotes the residual term capturing unexplained variation.16

The EAPC was calculated for the periods 1990–2021 and 2022–2040 to assess temporal changes. Intergroup comparisons among the five continents were carried out using the Mann–Whitney U-test to validate the reliability of our results.

The study investigated the relationship between the SDI and the prevalence of female infertility across different regions. By employing linear regression and Pearson correlation analyses, the researchers adjusted for potential confounding variables, such as gender and regional economic status. The SDI, a composite measure that considers per capita income, education level and fertility rate, is on a scale from 0 to 1, with higher scores indicating better sociodemographic conditions. This approach provided valuable insights into the socioeconomic factors influencing female infertility rates, which are crucial for informing public health policies and interventions.

Results

Projected global burden of female infertility, 2022–2040

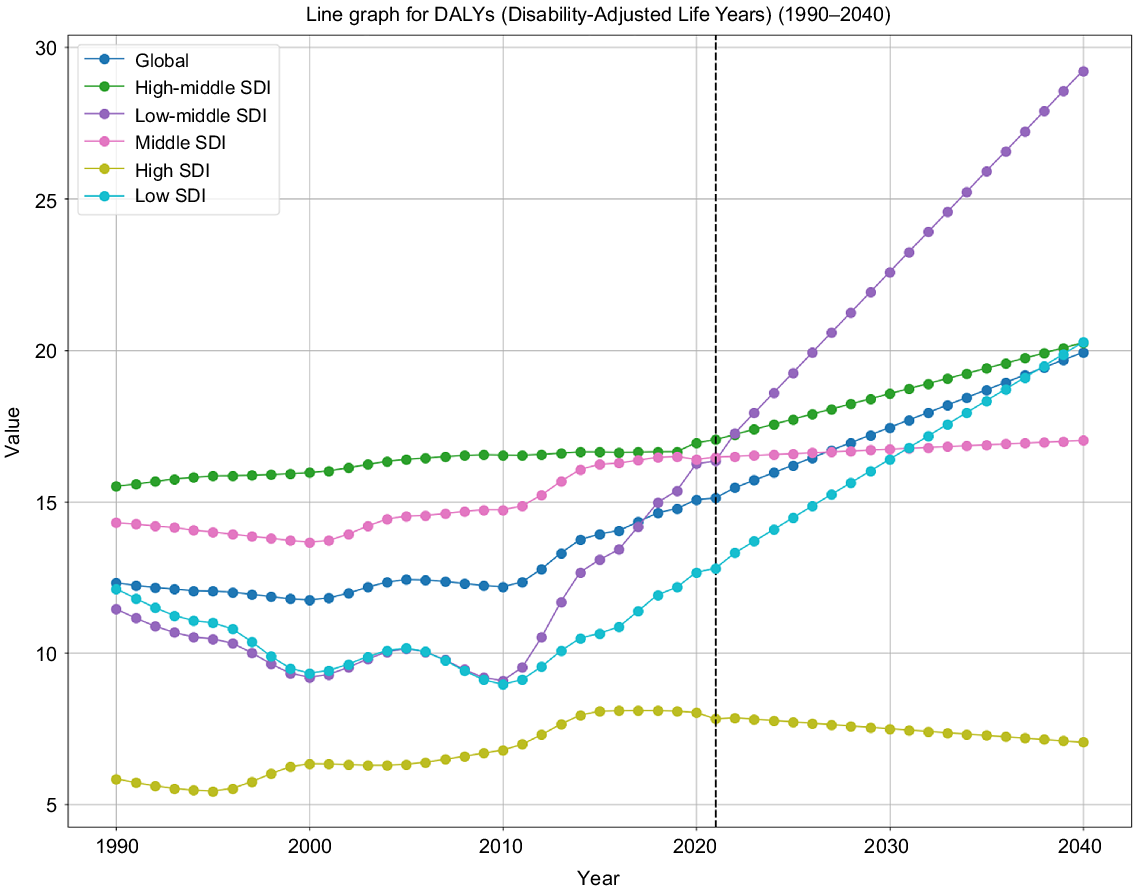

From 2022 to 2040, there is a projected rise in the global burden of female infertility. By the year 2040, the anticipated age-standardized DALY rate for female infertility is projected to be 19.92 (95% uncertainty interval (UI): 18.52–21.33), as illustrated in Table 1, Supplementary material Table S1 and Figs 1–2.

| Location | DALYs | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1990–2021 | 2022–2040 | ||

| Global | 0.71 (0.5391, 0.8789) | 1.42 (1.3951, 1.4418) | |

| High SDI | 1.41 (1.2534, 1.5641) | −0.60 (−0.6049, −0.5965) | |

| High-middle SDI | 0.27 (0.2436, 0.2882) | 0.90 (0.8938, 0.9128) | |

| Middle SDI | 0.62 (0.5032, 0.7377) | 0.17 (0.1741, 0.1748) | |

| Low-middle SDI | 1.19 (0.6479, 1.7252) | 2.94 (2.8437, 3.0461) | |

| Low SDI | 0.11 (−0.2762, 0.4963) | 2.35 (2.2858, 2.4144) | |

| Andean Latin America | 8.11 (6.6248, 9.6210) | 7.79 (7.0547, 8.5242) | |

| Australasia | 0.83 (0.6878, 0.9655) | −1.39 (−1.4088, −1.3642) | |

| Caribbean | −0.13 (−0.2845, 0.0296) | 0.06 (0.0578, 0.0579) | |

| Central Asia | 0.83 (0.5881, 1.0723) | 0.26 (0.2582, 0.2598) | |

| Central Europe | 0.84 (0.7123, 0.9764) | 0.12 (0.1171, 0.1175) | |

| Central Latin America | 1.17 (0.7851, 1.5525) | 0.69 (0.6846, 0.6957) | |

| Central sub-Saharan Africa | −0.13 (−0.7271, 0.4749) | 5.36 (5.0248, 5.7062) | |

| East Asia | 0.02 (−0.0299, 0.0681) | −0.32 (−0.3166, −0.3143) | |

| Eastern Europe | 0.58 (0.4534, 0.7005) | 0.19 (0.1866, 0.1875) | |

| Eastern sub-Saharan Africa | −1.23 (−1.4862, −0.9707) | 4.44 (4.2087, 4.6724) | |

| High-income Asia–Pacific | −0.40 (−0.6454, −0.1467) | 2.80 (2.7093, 2.8922) | |

| High-income North America | 2.91 (1.5086, 4.3276) | −2.66 (−2.7417, −2.5769) | |

| North Africa and Middle East | 1.09 (0.7833, 1.3983) | 4.02 (3.8263, 4.2046) | |

| Oceania | −1.53 (−1.7959, −1.2633) | −2.05 (−2.0941, −1.9967) | |

| South Asia | 1.85 (1.1294, 2.5717) | 1.82 (1.7824, 1.8595) | |

| Southeast Asia | 1.66 (1.3293, 1.9832) | 0.53 (0.5317, 0.5383) | |

| Southern Latin America | −0.26 (−0.3408, −0.1782) | 0.46 (0.4619, 0.4669) | |

| Southern sub-Saharan Africa | −0.80 (−1.5402, −0.0637) | 1.69 (1.6525, 1.7186) | |

| Tropical Latin America | 1.62 (1.0464, 2.2063) | −0.86 (−0.8640, −0.8470) | |

| Western Europe | 1.44 (1.1657, 1.7188) | 0.32 (0.3207, 0.3231) | |

Analyzing data from 2022 to 2040, the EAPC for the age-standardized DALY rate is projected to increase to 1.42 (95% confidence interval (CI): 1.3951–1.4418). This suggests a substantial rise in the disease burden compared with the period from 1990 to 2021, where the EAPC was 0.71 (95% CI: 0.5391–0.8789). These findings indicate a significant growth in the burden of female infertility expected in the next decade (see Table 1, Table S1 and Figs 1–3).

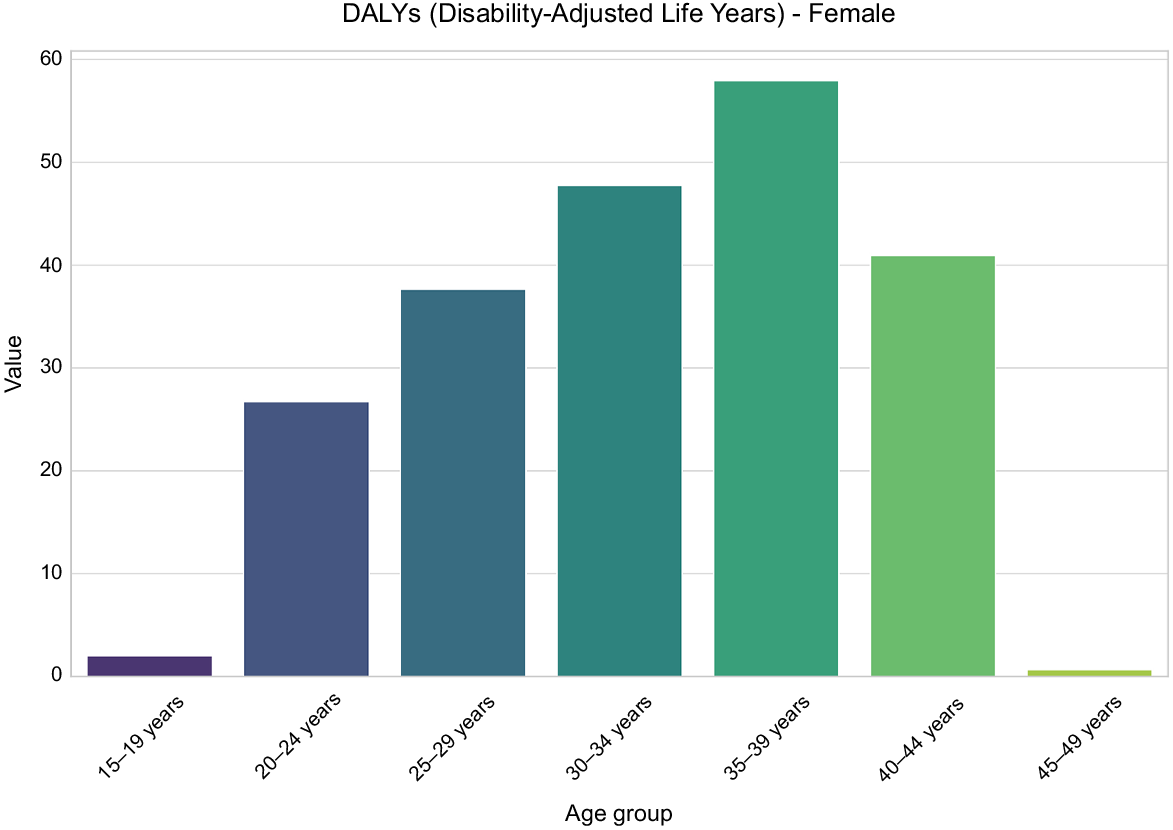

Projected global burden of female infertility by age, 2022–2040

From 2021 to 2040, there is a consistent upward trend in the global burden of female infertility across all age groups, as indicated by the rate per 100,000 population. In 2021, the rate for the 15–19 years age group was 1.80 (95% UI: 0.18–6.16), and it is projected to reach 2.03 (95% UI: 0.10–7.63) by 2040. Likewise, for the 20–24 years age group, the rate was 18.85 (95% UI: 4.55–50.88) in 2021, and it is anticipated to climb to 26.72 (95% UI: 6.64–70.76) by 2040.

Among women aged 25–29 years, the rate of a specific variable was 26.31 (95% UI: 5.15–75.32) in 2021, and it is projected to increase to 37.67 (95% UI: 7.68–106.48) by 2040. In the 30–34 years age group, the rate was 36.78 (95% UI: 7.25–99.81) in 2021, and it is expected to slightly rise to 47.78 (95% UI: 8.84–128.55) by 2040.

Among women aged 35–39 years, the estimated rate in 2021 was 50.00 (95% uncertainty interval [UI]: 12.08–142.55), and it is projected to increase to 57.95 (95% UI: 12.88–167.42) by 2040. In the 40–44 years age group, the rate was 35.95 (95% UI: 7.53–112.33) in 2021, and it is expected to slightly rise to 40.93 (95% UI: 7.94–127.95) by 2040.

For women aged 45–49 years, the rate in 2021 was 0.74 (95% UI: 0.09–4.48), expected to decline to 0.65 (95% UI: 0.09–3.67) by 2040.

The projections indicate a significant increase in rates of female infertility among individuals aged 25–44 years from 2021 to 2040. The predicted global rate of female infertility has notably risen in both young and middle-aged populations, underscoring the importance of improved management of the global burden of female infertility (Table S2 and Fig. 3).

Projection for the distribution of female infertility in different regions, 2022–2040

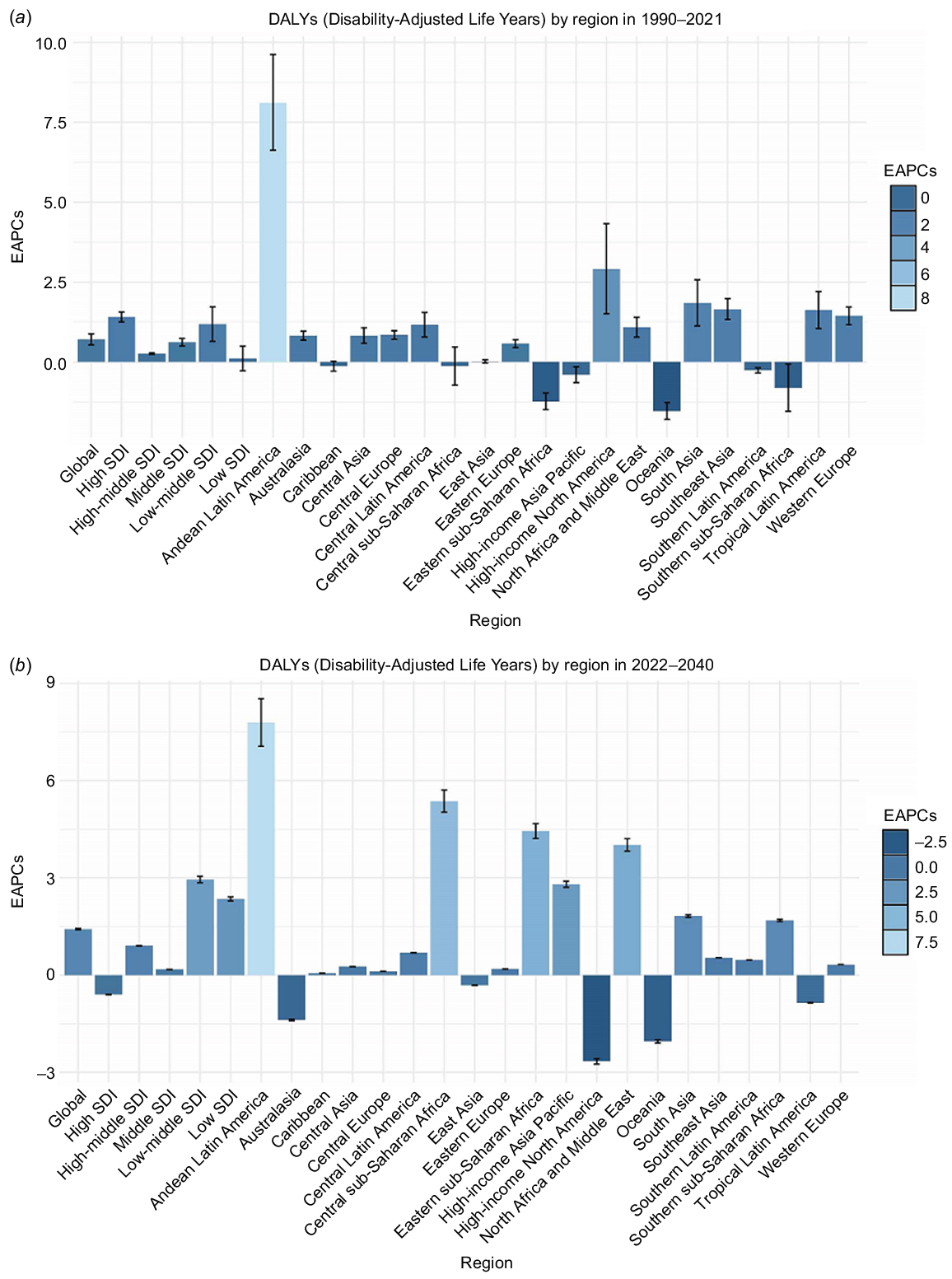

The projected global burden of female infertility from 2022 to 2040 varies significantly across different regions, as indicated by the EAPC and the ASR of DALYs.

Regions with the highest EAPC in DALYs due to female infertility are Andean Latin America, central sub-Saharan Africa and eastern sub-Saharan Africa, with values of 7.79 (95% CI: 7.0547–8.5242), 5.36 (95% CI: 5.0248–5.7062) and 4.44 (95% CI: 4.2087–4.6724), respectively. Following closely are North Africa and the Middle East, with an EAPC of 4.02 (95% CI: 3.8263–4.2046), whereas high-income Asia–Pacific shows an EAPC of 2.80 (95% CI: 2.7093–2.8922). Moreover, south Asia, southern sub-Saharan Africa, central Latin America, southeast Asia and southern Latin America also demonstrate positive EAPCs, suggesting a growing burden of female infertility (see Table 1, Fig. 1 and Table S3).

Projected DALY global burden of female infertility, by locations. (a) From 1990 to 2021. (b) From 2022 to 2040.

Contrastingly, high-income North America, Oceania and Australasia exhibit significant declines in EAPCs. Specifically, high-income North America shows the most substantial decrease, with an EAPC of −2.66 (95% CI: −2.7417, −2.5769), followed by Oceania at −2.05 (95% CI: −2.0941, −1.9967) and Australasia at −1.39 (95% CI: −1.4088, −1.3642). In contrast, various regions display slight negative or positive EAPCs, such as tropical Latin America, east Asia, the Caribbean, central Europe, eastern Europe, central Asia and western Europe (refer to Table 1 and Fig. 1; Table S3).

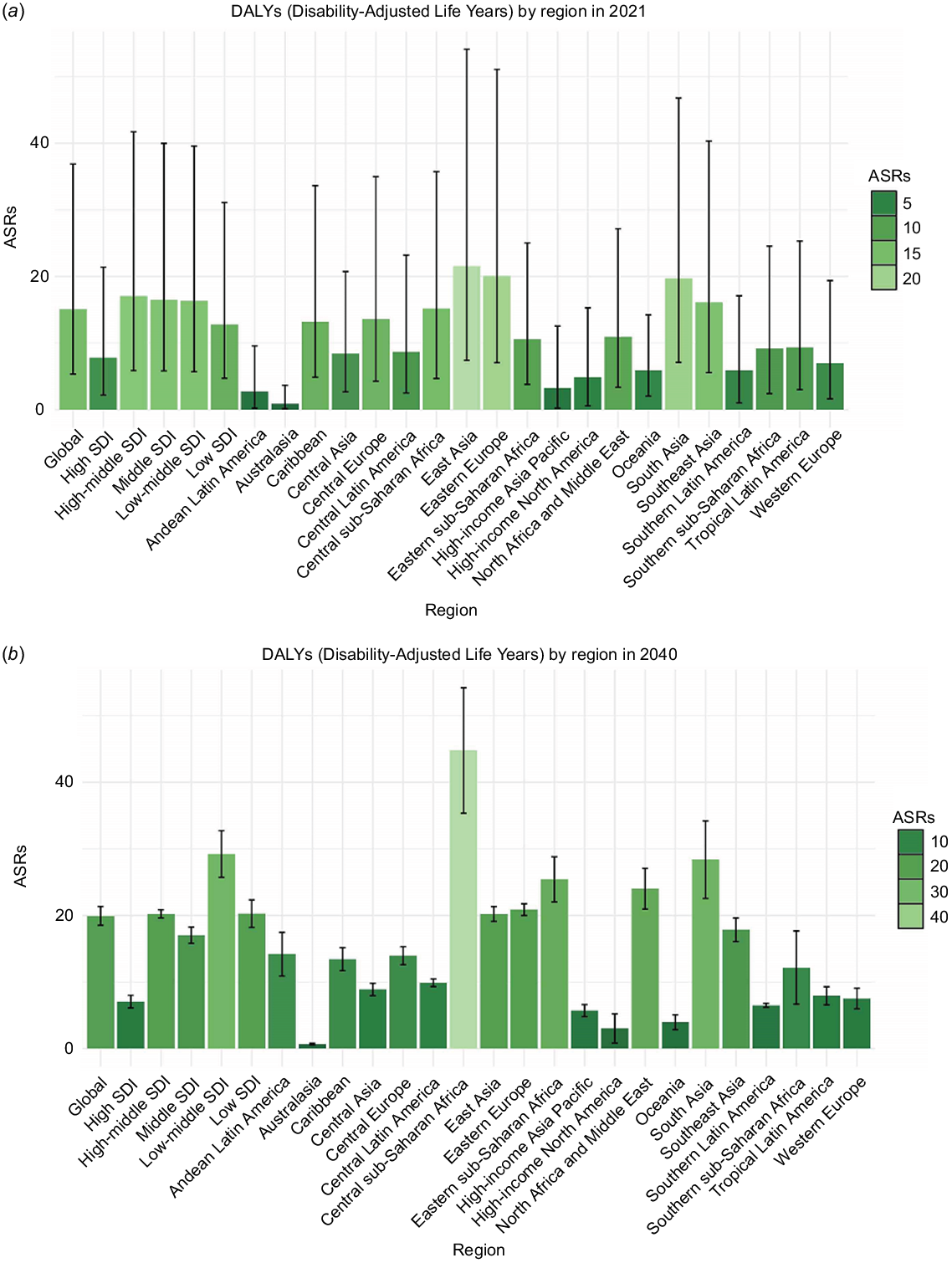

The analysis of DALYs for female infertility in 2040 reveals significant regional variations. Projections indicate that central sub-Saharan Africa is expected to have the highest ASR at 29.37 (95% UI: 24.58–34.16), followed by south Asia at 23.98 (95% UI: 21.03–26.94) and east Asia at 20.86 (95% UI: 20.29–21.43). Eastern Europe presents an ASR of 20.48 (95% UI: 20.04–20.92), with eastern sub-Saharan Africa closely following at 17.66 (95% UI: 15.93–19.38). Additionally, regions such as north Africa and the Middle East, southeast Asia, central Europe, the Caribbean and southern sub-Saharan Africa also exhibit high ASRs, highlighting a substantial burden of female infertility in these areas (Tables S1 and S4; Fig. 2).

Projected global burden of age-standardized DALY rate of female infertility in 2040, by locations and sex. (a) From 1990 to 2021. (b) From 2022 to 2040.

Projected global burden trend of age-standardized DALY rate of female infertility from 2022 to 2040, by SDI regions.

Australasia is projected to have the lowest ASR at 0.78 (95% UI: 0.72–0.84), followed by high-income North America at 4.08 (95% UI: 2.96–5.20) and high-income Asia–Pacific at 4.46 (95% UI: 4.00–4.92). Oceania, southern Latin America, western Europe, Andean Latin America, central Asia, tropical Latin America and central Latin America also exhibit low ASRs, ranging from 4.97 to 9.24 (refer to Tables S1 and S4; see Fig. 2).

Projection for the distribution of female infertility in different countries, 2022–2040

The projected global burden of female infertility from 2021 to 2040 shows significant variations across different regions and countries, as highlighted by the EAPC and the ASR of DALYs (Tables S5 and S6).

From 2022 to 2040, the countries with the highest EAPC in DALYs due to female infertility are Kenya, Chad and Peru, with EAPC values of 9.09 (95% CI: 8.0746–10.1097), 9.03 (95% CI: 8.0322–10.0409) and 9.02 (95% CI: 8.0227–10.0256), respectively. Guatemala closely follows, with an EAPC of 8.63 (95% CI: 7.7231–9.5476), whereas Lesotho shows an EAPC of 8.60 (95% CI: 7.6998–9.5111). Zimbabwe, Rwanda, Zambia, Ghana and Cambodia also have high EAPCs, all exceeding 8.00. Conversely, Mali, South Africa and Nicaragua exhibit significant negative EAPCs. Mali has the lowest EAPC at −13.17 (95% CI: −15.5783, −10.6990), followed by South Africa at −8.89 (95% CI: −9.8725, −7.9038) and Nicaragua at −3.96 (95% CI: −4.1444, −3.7762). Additionally, Ecuador, Papua New Guinea, Morocco, the USA, Benin, New Zealand,and the Syrian Arab Republic also display negative EAPCs, indicating a decreasing trend in the burden of female infertility in these regions (Tables S6 and S7; Supplementary Fig. S1).

The analysis of DALYs related to female infertility in 2040 highlights substantial regional variations. Projections suggest that Lesotho is anticipated to have the highest ASR at 55.86 (95% UI: 43.99–67.74), followed by Kenya at 53.87 (95% UI: 42.94–64.79) and Cambodia at 40.65 (95% UI: 33.16–48.13). Ghana presents an ASR of 36.28 (95% UI: 29.02–43.53), and Zambia’s ASR is 36.18 (95% UI: 29.40–42.96). Other countries with notably high ASRs include Chad, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Central African Republic, Gabon and Pakistan, with values ranging from 29.96 to 33.70. In contrast, Australia is projected to have the lowest ASR at 0.66 (95% UI: 0.61–0.71), followed by Colombia at 1.43 (95% UI: 1.13–1.72) and New Zealand at 1.44 (95% UI: 1.11–1.76). Ecuador’s ASR is noted at 1.51 (95% UI: 1.00–2.02), with Malawi at 1.90 (95% UI: 1.22–2.57). Burundi, Denmark, Brunei Darussalam, Canada and Uganda exhibit lower ASRs, ranging from 2.03 to 2.65 (Tables S5 and S8; Fig. S1).

Projection for the distribution and correlation analysis of female infertility in different levels of SDI and different continents, 2022–2040

The projected global burden of female infertility from 2022 to 2040 shows notable regional differences, as demonstrated by the ASR and the EAPC in DALYs. Projected global burden of DALY rate of female infertility in 2040 by ages is shown in Fig. 4.

By 2021, Africa is projected to have the highest median value for female infertility DALYs with significant variability, as illustrated in Fig. 1a. The P-values for comparisons between Africa and other continents reveal notable differences: Africa versus Europe (P = 0.012), Africa versus America (P = 0.4), Africa versus Asia (P = 0.12) and Africa versus Oceania (P = 0.72). These results emphasize the substantial disparities in female infertility burden across different regions (Fig. S2).

By 2040, a clear decrease in median values is observed across all continents. Africa retains the highest median value, showing less variability. Statistical analyses reveal significant differences, emphasizing the persistent disparities in female infertility prevalence. For example, the P-values for comparisons are as follows: Africa versus Europe (P = 0.00025), Africa versus America (P = 0.067), Africa versus Asia (P = 0.032) and Africa versus Oceania (P = 0.019; Fig. S2).

The correlation analysis between the burden of disease DALYs and the SDI reveals intriguing patterns. In 2021, scatter plots indicate weak negative correlations between DALYs and SDI across most continents. Europe (R2 = 0.07, P = 0.110) and Asia (R2 = 0.025, P = 0.326) exhibit some noticeable, but not statistically significant trends. In contrast, Africa shows an almost negligible correlation (R2 = 0, P = 0.890), implying a minimal relationship between SDI and female infertility burden within the continent (Fig. S3).

By 2040, the correlations reveal more distinct trends. Europe demonstrates a substantial negative correlation with SDI (R2 = 0.044, P = 0.2061), indicating that regions with higher SDI levels tend to have lower female infertility burdens. Similarly, Asia displays a significant trend (R2 = 0.12, P = 0.0268), further emphasizing the link between enhanced socioeconomic conditions and decreased infertility burdens. In contrast, Africa maintains a minimal correlation (R2 = 0.003, P = 0.7265), suggesting persistent challenges regardless of improvements in SDI (Fig. S3).

Discussion

Our study forecasts a substantial increase in the global burden of female infertility from 2021 to 2040, with varying trends observed across different age groups and regions. The age-standardized DALY rate is projected to rise, while rates are consistently decreasing within each age group, indicating improvements in the management of female infertility over time. Disparities persist among regions, with central sub-Saharan Africa and south Asia bearing higher burdens compared with Australasia and high-income North America. Variations in the estimated annual percentage change in DALYs underscore the importance of targeted interventions in regions with both increasing and decreasing trends. Some regions exhibit a weak correlation between the SDI and female infertility burden, whereas others, such as Europe and Asia, show more pronounced trends, suggesting that socioeconomic factors impact the burden differently. The results of this study highlight the imperative for region-tailored strategies and health policies to address the escalating global burden of female infertility.

Our projections suggest a steady increase in the global burden of female infertility from 2021 to 2040, with the expected age-standardized DALY rate notably rising by 2040. This significant uptick in disease burden, as indicated by the anticipated EAPC, highlights the escalating public health challenge posed by female infertility. The upward trend seen in recent decades underscores the necessity for heightened efforts in addressing the root causes and contributing factors. A number of factors could underlie this expected increase. For instance, socioeconomic changes related to the tendency to have children later in life and prioritizing career development could contribute to impaired fertility.17 Lifestyle factors, such as obesity, stress and environmental exposures, are known to negatively impact reproductive health, and may therefore contribute to an increased burden of infertility.3,18 Improved diagnostics and greater awareness might also lead to higher reporting rates, and thus a more accurate picture of the burden. In addition, inequalities in access to treatment for fertility problems and access to health care in general, especially in low- and middle-income countries, may contribute to the global burden.19 The results of this study highlight the urgency for public health interventions, comprehensive reproductive health education and improved accessibility to fertility treatments. An emphasis on preventive strategies and addressing socioeconomic determinants is crucial in combating the rising prevalence of female infertility.

The anticipated trends in female infertility rates from 2021 to 2040 reveal a nuanced landscape, showcasing both rises and falls across different age brackets. This pattern reflects the intricate dynamics of managing reproductive health. Projections indicate a slight decrease in infertility rates among women aged 15–19 and 45–49 years, possibly attributed to enhanced availability of reproductive health services, heightened awareness about fertility concerns and the introduction of early intervention initiatives.20 These enhancements are likely a result of comprehensive public health strategies that prioritize prevention and prompt treatment. Conversely, the rise in rates among individuals aged 20–44 years suggests the influence of other factors. Prior research has established that the likelihood of infertility increases with age in women.21 This decline in fertility is attributed to a gradual depletion of follicles and oocytes – termed ‘ovarian reserve’ – and an age-related decline in gamete quality.22 Furthermore, women in this age bracket may have a history of pregnancies. However, adverse outcomes from these pregnancies – such as miscarriage and preterm birth – could potentially contribute to cervical factor infertility.22 Consequently, it is imperative to assess the fertility status of women within this age bracket who have not conceived within 35 months of unprotected or therapeutic insemination. Timely detection, diagnosis and intervention can mitigate the detrimental effects of female infertility.

The projected distribution of female infertility from 2021 to 2040 reveals significant regional disparities, with certain areas facing higher burdens than others. Regions, such as Andean Latin America, central sub-Saharan Africa and eastern sub-Saharan Africa, are expected to experience the largest increases in DALYs, indicating a growing challenge in these regions. The elevated EAPCs in these regions may be due to various factors, such as limited healthcare access, lower socioeconomic conditions and a higher prevalence of risk factors that impact reproductive health negatively.23 In contrast, regions such as high-income North America, Oceania and Australasia exhibit negative EAPCs, indicating a diminishing burden of female infertility. The pronounced disparities in ASRs further underscore the enduring health inequalities between high-income and low-income regions. Notably, there are marked disparities between high-income and low-middle-income nations regarding the availability, quality and accessibility of infertility care services.19 In numerous low- and middle-income countries, government-subsidized infertility treatments are either scarce or entirely absent, and are not covered by health insurance plans.19 As a result, patients face a significant risk of incurring catastrophic costs during treatment. Moreover, assisted reproductive technology is often associated with high costs, prolonged duration, physical and emotional strain, and uncertain outcomes, all of which may deter patients from seeking treatment. In low- and middle-income countries, there is a pressing need to enhance technical regulatory frameworks. Incorporating infertility treatment as an essential service within universal health coverage could offer significant benefits. Such inclusion might substantially mitigate the burden of female infertility and foster fertility equity across diverse regions.

The analysis of female infertility distribution and correlation from 2021 to 2040 reveals significant regional variations influenced by socioeconomic and demographic factors. Africa exhibits the highest median value for female infertility DALYs, pointing toward challenges, such as inadequate healthcare infrastructure, socioeconomic instability and cultural barriers. The notable P-values in comparisons with other continents indicate persistent disparities in infertility burden. By 2040, median values decrease across all continents, yet Africa continues to bear the highest burden. Weak correlations between DALYs and the SDI in 2021, particularly in Africa, suggest that improvements in socioeconomic conditions alone may not suffice to reduce infertility burden without enhancements in healthcare access and quality.24 In contrast, Europe and Asia demonstrate more pronounced negative correlations between SDI and infertility burden by 2040, implying that higher socioeconomic development in these regions contributes to lower female infertility rates. These findings underscore the necessity for comprehensive strategies that integrate socioeconomic development, increasing healthcare infrastructure with healthcare interventions to effectively address the global burden of female infertility, especially in regions such as Africa, where the correlation between SDI and infertility remains minimal.

In recent years, there has been substantial progress in assisted reproductive technology. The introduction of blastocyst trophoblast cell biopsy and freeze–thaw embryo transfer technology has significantly enhanced the fertility success rate and decreased the complication rate.25 These advancements have offered an effective solution for couples desiring to have children, thereby mitigating the detrimental psychological and physical impacts of fertility anxiety on women. Cell therapy for assisted reproductive technology has been employed in the treatment of conditions such as endometriosis and early-onset ovarian insufficiency. Thus, enhanced access to assisted reproductive technologies could decrease the disease-adjusted life years lost due to future female infertility. Currently, interventions for female infertility primarily emphasize clinical treatments, with a notable deficiency in public health approaches. In many countries, the availability, accessibility and quality of infertility treatments remain significant challenges. The diagnosis and treatment of infertility often do not receive priority in national population and development policies or reproductive health strategies, and public health funding is seldom available.3 Additionally, the scarcity of trained professionals, essential equipment and infrastructure, coupled with the high cost of treatment medications, poses substantial barriers to addressing female infertility.3 The WHO recommends addressing common risk factors for female infertility, encompassing the incorporation of fertility awareness in national education plans; promoting healthy lifestyles to mitigate behavioural risks; preventing and early treating sexually transmitted infections; avoiding unsafe abortions, postpartum sepsis and complications from abdominal/pelvic surgery; and countering environmental toxins linked to infertility.3 In scenarios with limited funding, health education and screenings for women of reproductive age offer cost-effective solutions that can contribute to alleviating the burden of female infertility.

This study provides a comprehensive analysis of female infertility prevalence across different age groups, using data from 1990 to 2021 to predict trends up to 2040. By considering various demographic factors, such as gender, countries, regions and socioeconomic statuses, the research offers a global perspective on female infertility. The robustness of the analysis is enhanced by conducting multiple intergroup tests to ensure the reliability of the findings. However, limitations exist due to uneven data availability in different countries and regions, especially in lower SDI areas lacking comprehensive surveillance systems and population-based registries for female infertility. This may introduce uncertainties in the estimates. Additionally, relying on ICD codes in the GBD study could introduce biases due to variations in case definitions and healthcare access, potentially leading to underreporting of mild or asymptomatic cases. Factors, such as socioeconomic changes and cultural differences not considered by the GBD, could also impact the burden of female infertility, emphasizing the importance of interpreting the results cautiously.13

Conclusion

The projected global burden of female infertility is anticipated to rise substantially between 2021 and 2040, with significant regional variations. Although infertility rates are decreasing overall in various age groups, central sub-Saharan Africa and south Asia are facing higher burdens. The increase in age-standardized DALY rates and diverse EAPCs underscores the need for customized interventions. Addressing socioeconomic factors and improving healthcare infrastructure are crucial in reducing this burden. This study emphasizes the importance of implementing strategies tailored to specific regions to effectively mitigate the global impact of female infertility.

Consent

All of the participants or their legal representatives provided written informed consent during recruitment.

Data availability

The data is publicly available at Global Health Data Exchange (GHDx) [http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool].

Declaration of funding

This study was supported by the research on the mechanism of miR-183-5p promoting the proliferation of cervical cancer cells by targeting SHMT2 (2023KY293).

Author contributions

HW was responsible for data collection, statistical analysis, interpretation of data and writing the article. BJ was responsible for revising the manuscript, the supervision process and obtaining funding. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

1 Collaborators. Infertility. East Afr Med J 1989; 66(7): 425-6.

| Google Scholar |

2 The Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Aging and infertility in women. Fertil Steril 2006; 86(5 Suppl 1): S248-52.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

3 WHO. Infertility; 2024. Available at https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/infertility [cited 23 January 2025]

4 Borumandnia N, Majd HA, Khadembashi N, et al. Assessing the trend of infertility rate in 198 countries and territories in last decades. Iran J Publ Health 2021; 50(8): 1735-7.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

5 Nik Hazlina NH, Norhayati MN, Shaiful Bahari I, et al. Worldwide prevalence, risk factors and psychological impact of infertility among women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2022; 12(3): e057132.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

6 Farquhar CM, Bhattacharya S, Repping S, et al. Female subfertility. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2019; 5(1): 7.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

7 GBD 2021 Fertility and Forecasting Collaborators. Global fertility in 204 countries and territories, 1950–2021, with forecasts to 2100: a comprehensive demographic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2024; 403(10440): 2057-99.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

8 Adachi T. [Female infertility]. Nihon Rinsho 2002; 60(Suppl 4): 591-4.

| Google Scholar |

9 Boivin J, Bunting L, Collins JA, Nygren KG. International estimates of infertility prevalence and treatment-seeking: potential need and demand for infertility medical care. Hum Reprod 2007; 22(6): 1506-12.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

10 GBD 2021 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global burden and strength of evidence for 88 risk factors in 204 countries and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2024; 403(10440): 2162-203.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

11 Chakravarty BN, Dastidar SG. Unexplained infertility. J Indian Med Assoc 2001; 99(8): 414-5, 417.

| Google Scholar | PubMed |

12 Cheung AP. Clinical approach to female reproductive problems. Occup Med 1994; 9(3): 415-22.

| Google Scholar | PubMed |

13 Yu J, Fu Y, Zeng L, et al. Burden of female infertility in China from 1990 to 2019: a temporal trend analysis and forecasting, and comparison with the global level. Sex Health 2023; 20(6): 577-84.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

14 Wang Y, Wang W, Li H, et al. Trends in the burden of female infertility among adults aged 20–49 years during 1990–2019: an analysis of data from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. BMJ Open 2024; 14(7): e084755.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

15 GBD 2015 Eastern Mediterranean Region Diabetes and Chronic Kidney Disease Collaborators. Diabetes mellitus and chronic kidney disease in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: findings from the Global Burden of Disease 2015 study. Int J Public Health 2018; 63(Suppl 1): 177-86.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

16 GBD 2017 Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018; 392(10159): 1736-88.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

17 Yao Y, Qin M, Chen Y, Huang R, Yang Y, Lu N, Wang H. Analysis of risk factors related to female infertility and countermeasures. J Kunm Med Univ 2024; 45(9): 103-09.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

18 Braverman AM, Davoudian T, Levin IK, et al. Depression, anxiety, quality of life, and infertility: a global lens on the last decade of research. Fertil Steril 2024; 121(3): 379-83.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

19 Njagi P, Groot W, Arsenijevic J, et al. Financial costs of assisted reproductive technology for patients in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Hum Reprod Open 2023; 2023(2): hoad007.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

20 Klein Meuleman SJM, Post B, Vissers J, et al. Uterine niches and infertility: challenge for the future. Fertil Steril 2023; 119(5): 893.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

21 Sun H, Gong TT, Jiang YT, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence and disability-adjusted life-years for infertility in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: results from a global burden of disease study, 2017. Aging 2019; 11(23): 10952–91. 10.18632/aging.102497

22 Carson SA, Kallen AN. Diagnosis and management of infertility: a review. JAMA 2021; 326(1): 65-76.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

23 Malíčková K, Ambrusová Z, Belvončíková S, et al. Current possibilities of diagnostics and treatment of immunological causes of female infertility. Cas Lek Cesk 2021; 160(1): 5-13.

| Google Scholar | PubMed |

24 Fidler AT, Bernstein J. Infertility: from a personal to a public health problem. Public Health Rep 1999; 114(6): 494-511.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

25 Shi YW, Wang Q, Qi D. Frontier research hotspot and progress in assisted reproductive technology. J Shandong Univ 2021; 59(9): 97-102.

| Google Scholar |