Patient-delivered partner therapy for chlamydia: health practitioner views on updated guidance in Victoria, Australia

Chloe Warda A § , Helen Bittleston

A § , Helen Bittleston  A § , Jacqueline Coombe

A § , Jacqueline Coombe  A , Heather O’Donnell B , Jane S. Hocking

A , Heather O’Donnell B , Jane S. Hocking  A and Jane L. Goller

A and Jane L. Goller  A *

A *

A

B

Abstract

Patient-delivered partner therapy (PDPT) involves providing a prescription or medication to a patient diagnosed with chlamydia to pass to their sexual partner/s. Barriers to PDPT include uncertainty about its integration into clinical practice and permissibility. In Victoria, Australia, the Department of Health provides clinical guidance for PDPT (updated in 2022). We explored health practitioner views on the usefulness of the updated guidance for providing PDPT.

We conducted an online survey (12 December 2022 to 2 May 2023) of health practitioners who primarily work in Victoria and can prescribe to treat chlamydia. The survey displayed excerpts from the guidance, and asked closed and free-text questions about its ability to address barriers to PDPT. Quantitative data were descriptively analysed, complemented by conventional content analysis of qualitative data.

Of a total of 49 respondents (66.7% general practitioners), 74.5% were aware of PDPT, and 66.7% had previously offered PDPT. After viewing excerpts of the guidance, >80% agreed it could support them to identify patients eligible/ineligible for PDPT, and 66.7% indicated they would be comfortable to offer PDPT. The guidance was viewed as helpful to address some barriers, including complicated documentation (87.7%) and medico-legal concerns (66.7%). Qualitative data highlighted medico-legal concerns by a minority of respondents. Some raised concerns that the guidance recommended prescribing azithromycin, despite doxycycline being first-line chlamydia treatment.

The guidance was largely viewed as supportive for PDPT decision-making. There is scope for further refinements and clarifications, and wider dissemination of the guidance.

Keywords: accelerated partner therapy, Australia, chlamydia, expedited partner therapy, general practitioner, health practitioner, partner notification, patient-delivered partner therapy, PDPT, primary care, STI management.

Introduction

Patient-delivered partner therapy (PDPT) is a method of treating the sexual partners of a patient with chlamydia whereby the prescribing clinician provides a prescription/s or medication for the index patient to pass to their sexual partner/s when the partner/s are unlikely to present for testing or treatment.1–4 Referred to as expedited partner therapy in the US, PDPT is cost-efficient, safe,1 and has been shown to reduce re-infection and increase the number of partners treated.1 However, clinicians have expressed hesitancy about PDPT, as it involves providing medication without clinical consultation.5–7 In the UK, phone consultations have provided a mechanism to assess sexual partners before provision of chlamydia treatment.5

Formal support appears to facilitate clinicians to offer PDPT. In the US, expedited partner therapy was more likely to be provided in regions providing a favourable legal context.8 For Australian health practitioners, barriers to PDPT include time, practical constraints and medico-legal concerns,6,7 and a need for health authority guidance for PDPT has been identified.6,8 Despite availability of PDPT guidance in three of Australia’s eight states/territories, including Victoria,3 a 2019 survey of general practitioners (GPs) found that medico-legal concerns and a lack of practical resources to help navigate PDPT were persistent issues.3,7 In 2022, the Victorian Department of Health updated its PDPT guidance to reflect updated prescribing regulations9,10 and to provide practical resources for PDPT, including a decision flowchart and prescription template.10 This study explored health practitioner views on the updated guidance, including its ability to help address barriers to providing PDPT.

Methods

We conducted an online (Qualtrics) survey for prescribing clinicians regarding their views on the updated Victorian PDPT guidance.10 The survey drew on our earlier work, and evidence regarding barriers and facilitators to PDPT.3,6,7,11,12 The survey displayed several excerpts from the guidance (decision flowchart, prescription template, compliance information), and asked closed and open-ended questions about participants’ use of PDPT, comfort with PDPT, and whether the guidance might help address barriers to PDPT implementation (Box 1).6,7

Participants and recruitment

The survey was open from 12 December 2022 to 2 May 2023 to Victorian health practitioners authorised to prescribe treatment for chlamydia. Participants were recruited through social media (X, Facebook, LinkedIn), and university, general practice and sexual health networks. Upon survey completion, participants could enter a draw to win one of five A$100 gift vouchers.

Data quality and analysis

On 27 March 2023, a large influx of responses (markedly above the weekly average of 3–4 responses) was observed after survey advertisement on a social media platform. Many of these responses appeared to be fraudulent based on the presence of nonsensical and repeated free-text comments between surveys. To reduce the possibility of including invalid data, three researchers (CW, HB, JG) reviewed all responses on and after this date for their validity by applying multiple criteria that have been used previously (e.g. short survey (<5 min) completion time),13 and reached consensus on responses to exclude. A total of 288 respondents opened the survey and 87% (n = 250) consented, of whom 80.4% (n = 201) were deemed fraudulent (i.e. computer bots) and excluded or did not continue beyond demographic questions, leaving 49 valid responses for analysis.

Quantitative data were analysed descriptively in Stata (version BE17.0). Frequencies and proportions are presented based on agreement with statements about the guidance and barriers to providing PDPT. Free-text responses were analysed using conventional content analysis by one researcher (JC).14 Comments were coded inductively, and codes collapsed and redefined as the coding developed. Three researchers (JG, HB, JC) met to discuss the qualitative analysis as it progressed. Final codes were checked against the data and agreed upon by the team.

The study was approved by the University of Melbourne Human Research Ethics Committee (Ethics ID: 24490).

Results

A total of 49 people (65% women, median age of 38 years (IQR 33–48)) were included in the analysis (Table 1). Two-thirds (66.7%, n = 32) were GPs, 20.8% (n = 10) were sexual health physicians, 12.5% (n = 6) were nurse practitioners and one did not state their role. Most (74.5%, n = 35) were aware of PDPT, and 66.7% (n = 32) had previously offered PDPT, 21.9% (n = 7) of whom offered it often. For those who had offered PDPT, most (71.0%, n = 22) reported that their patients reacted positively to the offer. Half (48.9%, n = 22) were aware of the Victorian PDPT guidance, only seven of its update.

| n | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 49 | ||

| Gender identity (n = 49) | |||

| Male | 17 | 34.7 | |

| Female | 32 | 65.3 | |

| Age in years (n = 49) | |||

| ≤35 | 18 | 36.7 | |

| 36–50 | 20 | 40.8 | |

| ≥50 | 11 | 22.5 | |

| Clinical role (n = 48) | |||

| GPA | 32 | 66.7 | |

| Sexual health physician | 10 | 20.8 | |

| Nurse practitionerA | 6 | 12.5 | |

| Medical degree obtained in Australia (n = 49) | |||

| Yes | 44 | 89.8 | |

| No | 5 | 10.2 | |

| Years in current role (n = 46) | |||

| ≤5 | 24 | 52.2 | |

| 5–10 | 9 | 19.6 | |

| ≥11 | 13 | 28.3 | |

| Region of clinical practice (n = 47) | |||

| Metropolitan | 31 | 66.0 | |

| Regional or rural | 16 | 34.0 | |

| Number of patients with chlamydia per month (n = 47) | |||

| 0 | 5 | 10.6 | |

| 1–5 | 34 | 72.3 | |

| ≥6 | 8 | 17.0 | |

| Aware of PDPT as an option (n = 47) | |||

| Yes | 35 | 74.5 | |

| No | 12 | 25.5 | |

| Ever offered PDPT (n = 48) | |||

| Yes | 32 | 66.7 | |

| No | 16 | 33.3 | |

| Aware of Victorian PDPT guidance (n = 45) | |||

| Not aware of the guidance | 23 | 51.1 | |

| Aware of guidance but not its update | 15 | 33.3 | |

| Aware of guidance and its update | 7 | 15.6 |

Views on the PDPT guidance

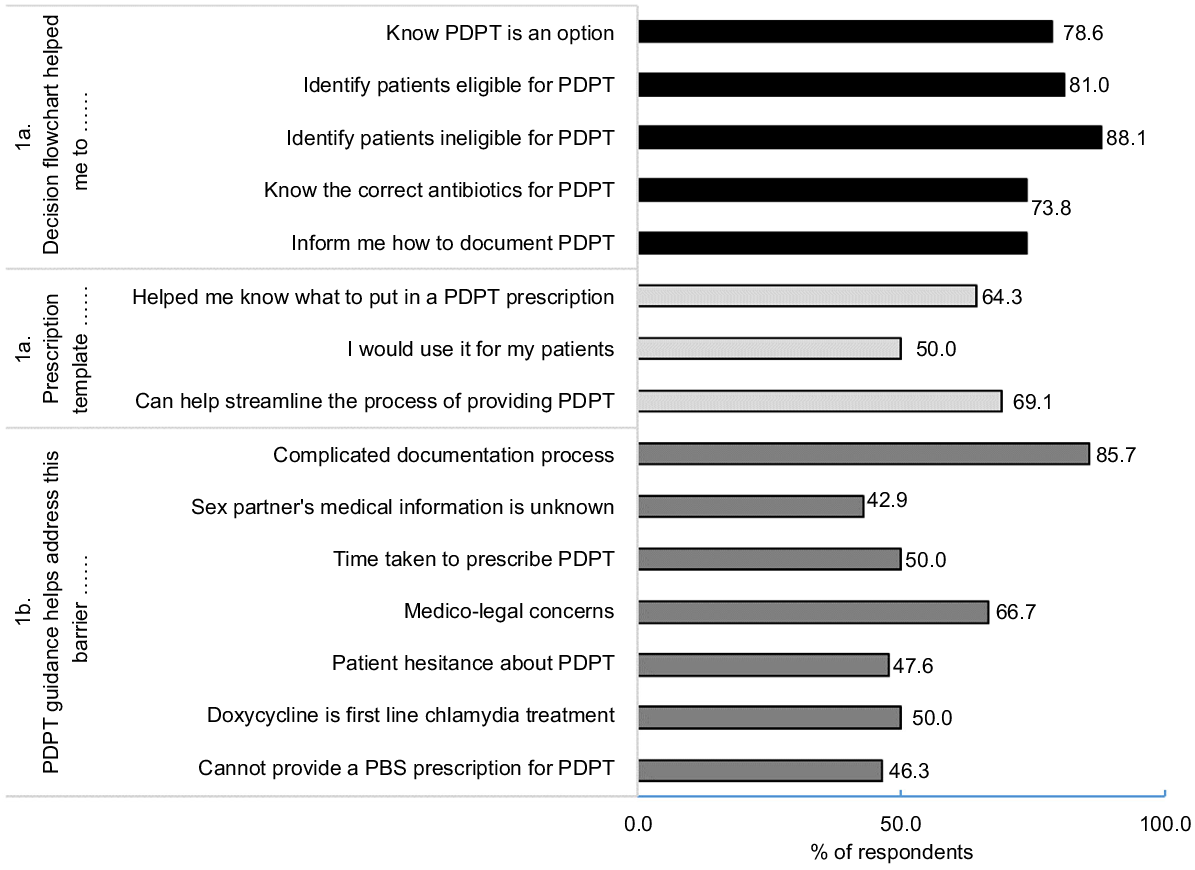

After viewing excerpts from the guidance (Fig. 1a), most respondents (>80%) agreed it could support them to identify patients eligible for PDPT, 64.3% agreed it could help with writing a PDPT prescription and 66.7% (n = 28) indicated they would be comfortable offering PDPT. The guidance was viewed as helpful to address some barriers to PDPT (Fig. 1b), including complicated documentation (85.7%) and medico-legal concerns (66.7%), but less helpful in addressing patient hesitance (47.6%), lack of medical information about sexual partners (42.9%) and that PDPT requires a private prescription (46.3%).

(a) Agreement with statements about the decision flowchart and prescription template, and (b) perceived ability the guidance can help address barriers to PDPT.

Forty-four participants provided a response to free text questions (105 comments in total). Many provided specific situations they might offer PDPT (e.g. ‘I am aware of PDPT in Victoria and would consider it if I felt there was a high likelihood that the partner would not attend a doctor for assessment and treatment.’). However, most noted that PDPT was not their first preference for facilitating the informing and treatment of a patient’s sexual partners (‘I feel that the partner having their own appointment is preferable, but treatment is better than none.’).

General feedback on the updated guidance suggested it is usable and useful (e.g. ‘Very clear and easy to use.’). However, some suggested changes that might improve clarity of specific aspects of the updated guidance, and some raised concerns about medico-legal implications of PDPT, mostly feeling uncomfortable prescribing for patients they have not seen or with an unknown medical history (‘I am uncomfortable prescribing antibiotics without seeing the patient: particularly with potential allergies and interactions with other medications’). A small number noted that the excerpts of the guidance did not necessarily assuage these concerns or provide them with the confidence to offer PDPT to their patients (‘Practitioner won’t feel protected if using this guidance especially [as] it said [it is] not considered legal advice.’). Others pointed to unresolved issues regarding the practicalities of PDPT, including time constraints (‘time consuming to organise treatment for partner in a short appointment and can’t bill for it?’) or it requiring a private prescription. Others raised concerns relating to their patients’ partners missing out on care when receiving PDPT (‘Partner loses opportunity for appropriate testing, education and follow up with own doctor.’) In addition, there was some confusion regarding the use of second-line treatment (azithromycin) for PDPT, (‘Do we prescribe doxy[cycline] as PDPT? Or is azithromycin first line even though doxy[cycline] is more effective’).

Ensuring that the updated guidance is publicised and easily accessible to all GPs was important to some respondents (‘Had not heard of the updated guidance. Maybe needs more implementation work or dissemination to GPs. Not more webinars, but sharing with practices the guidance printed versions sent to practices or emailed.’).

Discussion

This study found that health practitioners largely considered the Victorian PDPT guidance was supportive for PDPT decision-making, helped in determining patient eligibility for PDPT and in addressing some barriers to providing PDPT. Despite many indicating that the guidance helped clarify PDPT permissibility, others noted medico-legal concerns. Several emphasised that it is preferable for partners to access health care directly.

A need for clarity about PDPT permissibility and support to integrate PDPT into clinical practice has been identified by Australian GPs previously.6,7 It is encouraging that many respondents considered the guidance helped with the practicalities of providing PDPT, including its documentation, prescription and decision-making for PDPT eligibility. It is also reassuring that two-thirds of participants reported that the guidance might help address concerns about PDPT permissibility. However, other participants commented that they were not reassured by the excerpt, particularly as the guidance states that it should not be considered as legal advice. Other participants responded that they would need to read the full guidance to be certain about its permissibility. Review of the full guidance shows that it provides more detail about PDPT permissibility. It emphasises the practitioners’ duty of care to partners of patients with an STI, and that practitioners who prescribe or supply azithromycin to provide PDPT for chlamydia (in accordance with the PDPT guidelines) will generally be considered to have taken all reasonable steps to ensure a therapeutic need exists.15 The guidance further emphasises that the Drugs, Poisons and Controlled Substances Regulations 20179 do not prevent the prescribing or supply of PDPT. It is possible with further dissemination of the guidance that such issues might be addressed.

The guidance was considered less helpful in addressing some other barriers,6,7 including patient hesitance and lack of access to sexual partners’ medical information. One strategy that may address these barriers is inclusion of a phone call to sexual partner/s within the consultation, which has been shown to be acceptable to patients and partners in an Australian sexual health clinic.16 Phone consultations as part of accelerated partner therapy have also been used to facilitate clinical assessment of sexual partners in the UK.5 It is also important that support for PDPT as an option comes via other avenues. For example, in the US, expedited partner therapy is supported via a range of professional organisations.17,18 In Australia, support for PDPT is also provided via national STI management and contact tracing guidelines.19 Participants identified some areas for improving the guidance. One being, that treatment for the index patient should be clarified (the clinical flowchart specifies azithromycin for the PDPT prescription, but does not state that first-line treatment (doxycycline) should be provided to the index patient).19 Several respondents were unaware of the updated guidance, and articulated they would like to see it promoted more broadly. As noted above, PDPT is emphasised as an option in Australian STI management19 and contact tracing guidelines.20 Other avenues for its promotion is via professional education, such as through primary health networks.21

The main limitation to our study is the small number of responses, limiting our quantitative analysis to a descriptive one. Furthermore, our convenience sample is unlikely to be representative, and our findings are not generalisable to all Victorian health practitioners. Nonetheless, our content analysis of free-text responses facilitated deeper understandings on views on the guidance, and important insights into the extent the updated guidance is achieving its goal and where further refinement might be indicated. Finally, to minimise the burden on participants, only key excerpts from the guidance were provided within the survey, with a link to the full guidance. It is possible that some of the identified deficits relating to the excerpts may have been adequately addressed in the full guidance. This may be especially applicable to respondents with medico-legal concerns, as the full guidance provides more detail on compliance than given in the survey excerpt.

Conclusion

Availability of clear and practical health authority guidance is essential to provide health practitioners the option of confidently implementing PDPT in their practice. PDPT guidance should ideally be complemented by support from professional organisations and clinical guidelines. Currently, only three Australian jurisdictions provide guidance for PDPT, the Victorian guidance being the most comprehensive and recently updated. Our findings provide important understandings on the guidance’s useability and relevance, and may inform a basis for development or updates to guidance in other jurisdictions. Updated Victorian guidance for PDPT appeared to be largely acceptable and supportive to health practitioners. There is scope for further clarification regarding PDPT permissibility, and the appropriate antibiotics for patients and their sexual partner/s. Further promotion of the guidance is essential to increase awareness among Victorian health practitioners, and to support them to incorporate PDPT into practice.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available due to information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Conflicts of interest

JC is an Associate Editor for Sexual Health. To mitigate this potential conflict of interest they had no editor-level access to this manuscript during peer review.

Declaration of funding

This research did not receive any specific funding. This work was conducted as part of a NHMRC partnership grant in collaboration with the Victorian Department of Health.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the development of the survey. CW, HB, JC and JLG were responsible for administering the survey. CW, HB, JC and JLG conducted the analyses. All authors contributed to interpretation of findings and manuscript writing. All authors approved the final submitted version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the time and valuable contributions of our survey respondents.

References

1 Ferreira A, Young T, Mathews C, Zunza M, Low N. Strategies for partner notification for sexually transmitted infections, including HIV. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 2013(10): Cd002843.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

2 Estcourt CS, Stirrup O, Copas A, Low N, Mapp F, Saunders J, et al. Accelerated partner therapy contact tracing for people with chlamydia (LUSTRUM): a crossover cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet Public Health 2022; 7(10): e853-e65.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

3 Goller JL, Coombe J, Bourne C, Bateson D, Temple-Smith M, Tomnay J, et al. Patient-delivered partner therapy for chlamydia in Australia: can it become part of routine care? Sex Health 2020; 17(4): 321-9.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

4 Coombe J, Goller J, Bittleston H, Bateson D, Bourne C, O’Donnell H, et al. Patient-delivered partner therapy: one option for management of sexual partner(s) of a patient diagnosed with a chlamydia infection. Aust J Gen Pract 2022; 51: 425-9.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

5 Estcourt CS, Sutcliffe LJ, Copas AJ, Mercer CH, Roberts TE, Jacksone L, Symonds M, et al. Developing and testing accelerated partner therapy for partner notification for people with genital Chlamydia trachomatis diagnosed in primary care: a pilot randomised controlled trial. Sex Transm Infect 2015; 91: 548-54.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

6 Pavlin NL, Parker RM, Piggin AK, Hopkins CA, Temple-Smith MJ, Fairley CK, et al. Better than nothing? Patient-delivered partner therapy and partner notification for chlamydia: the views of Australian general practitioners. BMC Infect Dis 2010; 10: 274.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

7 Goller JL, Coombe J, Bittleston H, Bourne C, Bateson D, Vaisey A, et al. Patient delivered partner therapy for chlamydia infection is used by some general practitioners, but more support is needed to increase uptake: findings from a mixed-methods study. Sex Transm Infect 2022; 98(4): 298-301.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

8 Cramer R, Hogben M, Handsfield HH. A historical note on the association between the legal status of expedited partner therapy and physician practice. Sex Transm Dis 2013; 40(5): 349-51.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

9 Drugs, Poisons and Controlled Substances Regulations; 2017. Available at https://www.legislation.vic.gov.au/in-force/statutory-rules/drugs-poisons-and-controlled-substances-regulations-2017/007

10 Department of Health. Patient delivered partner therapy (PDPT) for chlamydia – clinical guidance and FAQs. Melbourne: State Government Victoria, Department of Health; 2022. Available at https://www.health.vic.gov.au/publications/patient-delivered-partner-therapy-pdpt-for-chlamydia

11 Layton E, Goller JL, Coombe J, Temple-Smith M, Tomnay J, Vaisey A, Hocking J. ‘It’s literally giving them a solution in their hands’: the views of young Australians towards patient-delivered partner therapy for treating chlamydia. Sex Transm Infect 2021; 97: 256-260.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

12 Lorch R, Bourne C, Burton L, Lewis L, Brown K, Bateson D, et al. ADOPTing a new method of partner management for genital chlamydia in New South Wales: findings from a pilot implementation program of patient-delivered partner therapy. Sex Health 2019; 16(4): 332-9.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

13 Ballard A, Cardwell T, Young A. Fraud detection protocol for web-based research among men who have sex with men: development and descriptive evaluation. JMIR Public Health Surveill 2019; 5(1): e12344.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

14 Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 2005; 15(9): 1277-1288.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

15 Victoria State Government. All reasonable steps (and other key terms). Information for health practitioners. In: Department of Health, editor. Victoria State Government; 2023. Available at https://www.health.vic.gov.au/publications/all-reasonable-steps-and-other-key-terms-requirements-for-health-practitioners

16 Woodward SC, Tyson HA, Martin S. An observational study of the acceptability of patient-delivered partner therapy for management of chlamydia. Sex Health 2020; 17(4): 381-3.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

17 Burstein GR, Eliscu E, Ford K, Hogben M, Chaffee T, Straub D, et al. Expedited partner therapy for adolescents diagnosed with chlamydia or gonorrhea: a position paper of the society for adolescent medicine. J Adolesc Health 2009; 45(3): 303-309.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

19 Australasian Sexual Health Alliance. Australian STI Management Guidelines, for use in primary care. Australian Society for HIV Medicine; 2024. Available at https://sti.guidelines.org.au/

20 Australasian Society for HIV Viral Hepatitis and Sexual Health Medicine. Australasian Contact Tracing Guidelines. ASHM; 2022. Available at https://contacttracing.ashm.org.au/

21 North Western Melbourne Primary Health Network. Victorian HIV and hepatitis integrated training and learning (VHHITAL). Melbourne: NWMPHN; 2024. Available at https://nwmphn.org.au/about/partnerships-collaborations/vhhital/