The impact of Chatbot-Assisted Self Assessment (CASA) on intentions for sexual health screening in people from minoritised ethnic groups at risk of sexually transmitted infections

Tom Nadarzynski A # * , Nicky Knights A # , Deborah Husbands A , Cynthia A. Graham B , Carrie D. Llewellyn C , Tom Buchanan A , Ian Montgomery D , Nuha Khlafa A , Jana Tichackova A , Riliwan Odeyemi A , Samantha Johnson A , Neomi Jesuthas A , Syeda Tahia

A # * , Nicky Knights A # , Deborah Husbands A , Cynthia A. Graham B , Carrie D. Llewellyn C , Tom Buchanan A , Ian Montgomery D , Nuha Khlafa A , Jana Tichackova A , Riliwan Odeyemi A , Samantha Johnson A , Neomi Jesuthas A , Syeda Tahia  A and Damien Ridge

A and Damien Ridge  A

A

A

B

C

D

Handling Editor: Dan Wu

Abstract

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) present a significant global public health issue, with disparities in STI rates often observed across ethnic groups. The study investigates the impact of Chatbot-Assisted Self Assessment (CASA) on the intentions for sexual health screening within minoritised ethnic groups (MEGs) at risk of STIs as well as the subsequent use of a chatbot for booking STI screening.

A simulation within-subject design was utilised to evaluate the effect of CASA on intentions for STI/HIV screening, concern about STIs, and attitudes towards STI screening. Screening intentions served as the dependent variable, while demographic and behavioural factors related to STI/HIV risk were the independent variables. ANCOVA tests were conducted to measure the impact of CASA on these perceptions.

Involving 548 participants (54% women, 66% black, average age = 30 years), the study found that CASA positively influenced screening intentions t(547) = −10.3, P < 0.001], concerns about STIs t(544) = −4.96, P < 0.001, and attitudes towards sexual health screening [t(543) = −4.36, P < 0.001. Positive attitudes towards CASA were observed (mean, 13.30; s.d., 6.73; range, −17 to 21). About 72% of users who booked STI screening appointments via chatbot were from MEGs.

CASA increased motivations for STI screening intentions among ethnically diverse communities. The intervention’s non-judgemental nature and the chatbot’s ability to emulate sexual history-taking were critical in fostering an environment conducive to behavioural intention change. The study’s high acceptability indicates the potential for broader application in digital health interventions. However, the limitation of not tracking actual post-intervention behaviour warrants further investigation into CASA’s real-world efficacy.

Keywords: AI, artificial intelligence, behaviour change, chatbot, natural language processing, risk assessment, self-assessment, sexual health, sexually transmitted disease, sexually transmitted infections, virtual assistant.

Introduction

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are a major global health issue, with the World Health Organization estimating that one million new infections occur each day worldwide.1 Although age-standardised rates of STI incidence have decreased in most countries from 1990 to 2019, the actual number of new cases has increased.2 This highlights the ongoing challenge that STIs pose to public health, particularly in regions such as sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America. Although STIs potentially affect all people, there are significant ethnic disparities reported in some Western countries, such as the United States and the United Kingdom.3,4 STIs disproportionately affect people from minoritised ethnic groups (MEGs), with people of black heritage or mixed race being significantly more likely to be diagnosed with STIs such as chlamydia, gonorrhoea, and syphilis compared to their white counterparts.5 Addressing the disparities in STI prevalence and advancing sexual health equity requires an understanding of the complex relationships between ethnic groups, disease prevalence, and social structures.

Poorer STI outcomes for ethnic minorities are commonly caused by systemic issues such as limited access to quality health care, social stigma, and economic inequalities rather than differences in behaviour.6 Unfortunately, cultural stereotypes and biases in health care, including assumptions about sexual promiscuity and racism, can discourage MEGs from seeking care. Moreover, economic disparities, unemployment, insecure work and migration status may further exacerbate these issues, making it difficult for people to access sexual health services.7 Additionally, these disparities are not only health-related but are also evident in research and policy.

People from MEGs are notably under-represented in sexual health research. For instance, in the IMPACT trial, which explored the feasibility of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), only 1.5% of participants identified as black African.8 Therefore, addressing the epidemiology of STIs requires an understanding of the complex interplay of social determinants of health, such as socio-economic deprivation, and social stigma, as well as access and utilisation of quality sexual health services, especially in the era of digitalisation and automation.9,10

Digital sexual health services are becoming increasingly important in addressing ethnic disparities in STIs. These services offer remote consultations, online testing kits, and digital resources for education and support, which can overcome barriers to access, such as location and stigma associated with in-person visits.11 Digital sexual health interventions have the potential to address these disparities by providing targeted and accessible resources to underserved populations.12 It is necessary for these interventions to be culturally sensitive, inclusive, and tailored to the specific needs of the target population in order to effectively address disparities, improve engagement and outcomes. However, the effectiveness of these services depends on their design and implementation. To ensure that they address both medical and socio-cultural factors that contribute to health disparities, digital services should be co-developed with stakeholders from these communities.13 If implemented thoughtfully and inclusively, digital sexual health services hold tremendous promise for reducing health inequalities.

Advances in health care, especially in the field of automation and artificial intelligence (AI), show great promise for improving sexual health outcomes.14,15 AI has been rapidly integrated into sexual health, covering areas such as health promotion, identification of individuals in need of PrEP and STI/HIV screening, as well as education on sex, sexuality, and risky sexual practices.16,17 AI’s capabilities extend to improving disease surveillance, detecting anomalies in screening tests, and offering personalised health advice based on individual risk and behavioural patterns. Among conversational AI systems, chatbots, also known as virtual agents or artificial human avatars, have proven to be moderately acceptable for sexual health education and promotion among people from MEG.18 Unlike static websites, chatbots engage in message exchanges, using natural language processing to understand questions and respond with clinically validated answers. They also employ behavioural algorithms for decision-making, symptom checking, or online triage, enhancing health literacy and support for treatment, screening, counselling, and behaviour change.19 Such tailoring of information can increase chatbots’ cultural competence, making them more relevant and accessible to people from ethnically, culturally, and linguistically diverse communities.

Chatbot-Assisted Self Assessment (CASA)

Stigma and discrimination can create barriers to accessing necessary healthcare services, which is where conversational AI can be particularly useful. Chatbots can make it easier for people to assess their sexual health needs and encourage more open conversations around sensitive topics, such as STIs.20 This could lead to a higher frequency of clinical consultations and uptake of STI screening, compared to traditional face-to-face settings. Chatbots can also facilitate numerous behaviour change techniques to promote healthy habits, while presenting content in multiple translations, thus overcoming language barriers.21 Chatbots can help with goal setting, self-monitoring and provide personalised feedback, empowering users to better understand and manage their health. By offering emotionally intelligent support and tailored messaging, chatbots can help overcome barriers to STI screening that are experienced by ethnic minorities such as stigma, fear of discrimination and challenges related to language and culture.22 Additionally, disclosing information to chatbots can motivate some individuals from linguistically diverse groups to access appropriate healthcare services in their language. Meta-analyses indicate a ‘question-behaviour effect’, where personal and health-related enquiries from chatbots significantly impact behaviour change.23,24 This suggests that AI systems incorporating conversational techniques could lead to better user reflections and positive health outcomes.

Our previous mixed-methods research identified design principles for a chatbot-based intervention aimed at behaviour change in ethnically diverse communities.18 The current study aimed to apply CASA principles in the context of ethnic disparities in sexual health outcomes. Our objective was to examine the impact of chatbot conversation on motivation for STI screening as well as understand the attitudes and level of information disclosure to the chatbot.

Materials and methods

Design

A within-subject design was used to assess the impact of CASA on intentions for STIs/HIV screening, concern about STIs and a general attitude towards STI screening. While the dependent variable was screening intentions, the independent variables were demographic and behavioural factors related to STI/HIV susceptibility. The study was approved by the University of Westminster Research Ethics Committee [ref: ETH2223-0608].

Participants and recruitment

The study focused on ethnically diverse populations that are likely to be at an increased risk of STIs. Eligible participants were above the age of 18 years, residing in the UK and able to provide informed consent. Those who indicated their residence outside the UK were excluded from the analysis to make the study relevant to the UK healthcare context.

Between December 2022 and July 2023, we used social media platforms, including Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and Reddit, and employed various handles and hashtags relevant to our study aims, such as ‘#BlackSexualHealth’. We also advertised our study on Prolific, a platform specifically designed for research participation and data collection. We reached out to student organisations and unions in UK-based universities to circulate our study advert. We distributed paper leaflets and posters across multiple university campuses and halls of residence in London and used an in-person leafleting strategy in public spaces across London with a high representation of people from ethnically diverse communities. We also engaged with third sector organisations such as HIV and sexual health charities to circulate our study advert within their networks. Due to the multi-channel approach to recruitment, we could not record participation rates via each recruitment strategy.

Procedure and measurement

Potential participants could access the study, hosted on Qualtrics, via a URL or QR code. The information page outlined the study aims, including the CASA simulation for sexual health, eligibility criteria and information about optional entry to a prize draw worth GBP100 for those who completed it. Consent was gathered by ticking a button indicating that participants had understood the nature of the study and their rights. The survey began with demographic questions, i.e. country of residence, age, ethnicity, gender identity and relationship status. Next, participants were asked to indicate their agreement to three statements related to sexual health screening: (1) their intentions to undergo a sexual health check-up in the next 3 weeks; (2) their concern about STIs; and (3) their attitude towards regular sexual health screening. For all survey attitudinal items, seven optional responses ranged from ‘−3 Strongly disagree’ to ‘0 Neither agree nor disagree’ and ‘+3 Strongly agree’, with higher scores indicating stronger intentions, more concern and positive attitudes.

Participants were then asked for a nickname combining four letters and two numbers to link their responses with chatbot conversations. They were given information about CASA and its purpose, including a confidentiality statement. Participants were asked to exit the Qualtrics survey using a link to a platform where the CASA was hosted. There, the chatbot introduced itself and asked users to insert their nickname. Using a conversational approach, it asked users about their age, gender identity, racial identity, ethnic origin and the language they speak at home. Next, it asked behavioural questions such as the last time they had sexual contact (if ever), any current STI symptoms, past STI diagnosis, the gender of their sexual partners, the consistency of condom use, the last time they tested for STIs, and the number of sexual partners since the last STI test. Afterwards, the chatbot informed the users about their eligibility for a free sexual health check-up and asked if they wished to learn more. The last question of the CASA asked whether users wanted to order an STI screening kit, book a check-up appointment, talk to a human operator or visit the Positive East website for more information. Throughout the conversation, the chatbot language used empathic language and explained the purpose of asking these specific questions to promote self-reflection about personal susceptibility to STIs. Users were also given a ‘prefer not to say’ option to indicate non-disclosure of information.

The chatbot then asked users to complete the Qualtrics survey, which again asked about intentions, STI concerns, and attitudes towards sexual health screening. There were also seven attitudinal questions about CASA related to the ease of use, satisfaction, perceived relevance and usefulness. The participants were then presented with a link to another chatbot called Pat, hosted by leading HIV charity – Positive East (www.chattopat.com).25 This chatbot, which used natural language processing was able to understand user questions and offer further information concerning sexual health and HIV as well as it allowed users to book an STI/HIV check-up appointment directly. Users were able to follow pre-selected questions such as ‘Where should I test for HIV or STI?’ or type their questions using a free text box.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were first conducted to identify trends in data and check for assumptions. Paired-sample t-tests were conducted to determine the impact of the CASA on intentions and attitudes towards STI screening and STI concerns. ANCOVA tests were then conducted, with baseline STI screening intentions as a covariate and post-CASA STI screening intentions as the dependent variable. Each demographic and behavioural variable was entered as an independent variable to determine its association with STI screening intentions. Afterwards, the attitude variable ‘chatbot is a bad idea’ was reversed and seven attitudes towards CASA variables were summed, ranging from −21 to 21. ANOVA tests were performed to identify demographic and behavioural variables associated with positive attitudes towards the CASA. Finally, a phrase count analysis of the Pat chatbot script was used to explore the type and frequency of information about sexual health and HIV that was requested from users and the number of subsequent STI/HIV screening appointments booked.

Public and patient involvement

Throughout the research process, a Public and Patient Involvement (PPI) group played an integral role, being involved at key stages, from the study’s co-design to data collection to finalising the research outputs.26 This engagement ensured that the study reflected real-world perspectives and addressed relevant concerns. The PPI group comprised eight public members from MEGs, representing a diverse cohort. They actively reviewed and validated the study’s findings, providing valuable insights into the application of the CASA for sexual health services.

Results

Sample characteristics

A total of 548 participants took part in the study (Table 1). The majority were women, native English speakers, identified as Black, with an average age of 30 years. There were equal proportions of those who were single and in a monogamous relationship. While 10% reported not having had sexual intercourse before, 79% of those sexually active reported having sexual partners of the opposite sex, 45% had sex within the past 2 weeks, 41% had one sexual partner since their last STI check-up, 16% had a previous STI diagnosis, and 32% did not use condoms consistently. Just under half (47%) had never been tested for STIs. In response to using CASA, just over half (54%) wanted to learn more about STI testing, 44% reported the willingness to order an STI testing kit and 9% to book a sexual health screening appointment. In general, the non-disclosure of information to the chatbot was low across all variables, ranging between 0.5% and 3%, with one exception for the question about condom use (9%).

| Variable | N (%) | Variable | N (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relationship status | Last intercourse | |||

| Single | 251 (46) | Never had sex | 59 (11) | |

| Monogamous relationship | 258 (47) | In past 2 weeks | 248 (45) | |

| Open relationship | 33 (6) | Over 2 weeks ago | 223 (41) | |

| English language | Prefer not to say | 17 (3) | ||

| Native English | 473 (86) | STI symptoms | ||

| Non-native | 74 (14) | Yes | 42 (8) | |

| Age range (years) | No | 465 (85) | ||

| 18–24 | 181 (33) | Not sure | 34 (6) | |

| 25–30 | 168 (31) | Prefer not to say | 6 (1) | |

| 31–35 | 99 (18) | Ever had STI | ||

| 36–40 | 60 (11) | Yes | 88 (16) | |

| 41+ | 39 (7) | No | 403 (74) | |

| Sex | Not sure | 51 (9) | ||

| Female | 294 (54) | Prefer not to say | 5 (1) | |

| Male | 243 (44) | Gender of sexual partners | ||

| Non-binary | 5 (1) | Opposite sex | 435 (79) | |

| Other | 5 (1) | Same sex women | 12 (2) | |

| Racial identity | Same sex men | 10 (2) | ||

| Asian/Pacific Island | 65 (12) | Both men and women | 20 (4) | |

| Black | 361 (66) | Gender diverse | 2 (0.5) | |

| Latin/Hispanic | 21 (4) | Prefer not to say | 4 (1) | |

| Middle Eastern/Arab | 7 (1) | Condom use | ||

| Mixed/Multiple | 37 (7) | Do not use condoms | 173 (32) | |

| White | 49 (9) | Less than half time | 45 (8) | |

| Other | 4 (0.5) | Half time | 53 (10) | |

| Prefer not to say | 3 (0.5) | More than half time | 96 (18) | |

| Ethnic identity | All of time | 132 (24) | ||

| West Asia/Middle East | 9 (2) | Prefer not to say | 48 (9) | |

| South/south-eastern Asia | 60 (11) | Last STI test | ||

| East/central Asia | 4 (0.5) | Less than 3 months | 60 (11) | |

| Central America/Caribbean | 81 (15) | 3–6 months | 41 (8) | |

| South America | 18 (3) | 6–12 months | 50 (9) | |

| North Africa | 16 (3) | Over a year | 131 (24) | |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 224 (41) | Never | 256 (47) | |

| Eastern Europe | 10 (2) | Prefer not to say | 9 (2) | |

| Mixed | 32 (6) | Number of sexual partners | ||

| Western Europe | 63 (12) | None | 139 (25) | |

| Other | 23 (4) | 1 | 225 (41) | |

| Prefer not to say | 7 (1) | 2–3 | 118 (22) | |

| 4–5 | 29 (5) | |||

| 6+ | 19 (4) | |||

| Prefer not to say | 17 (3) |

Impact of CASA on screening motivations

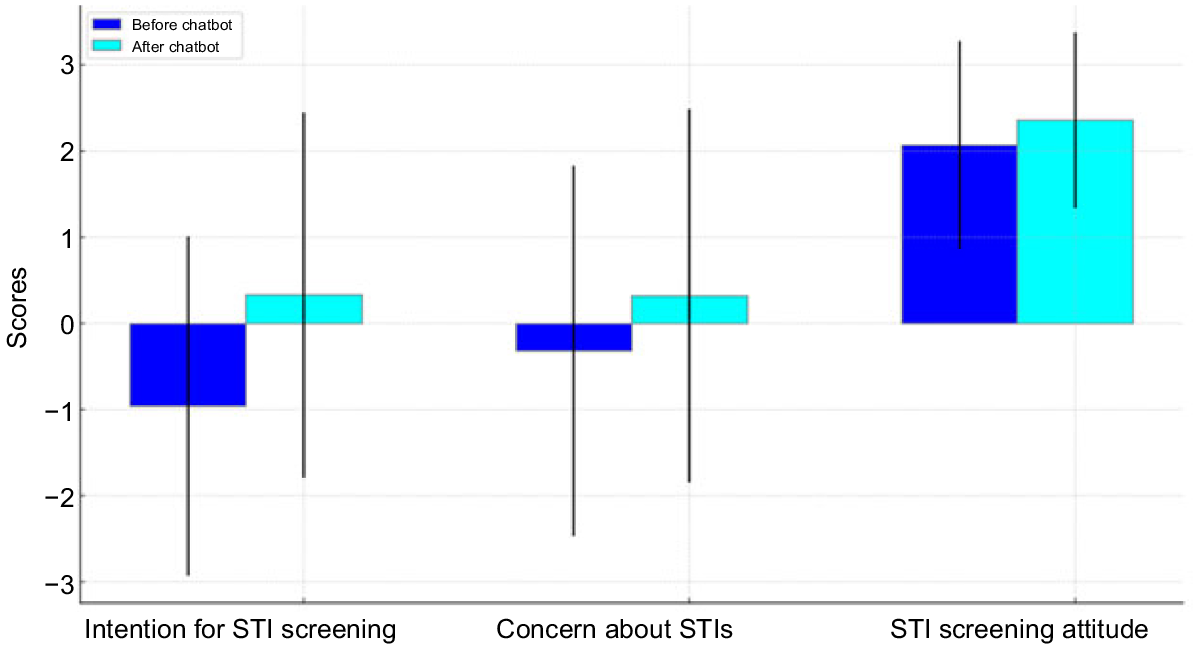

Before the CASA, most participants had not had strong intentions to screen for STIs (mean, −0.96; s.d., 1.97), had low concerns about STIs (mean, −0.32; s.d., 2.15) and had positive attitudes towards regular sexual health screening (mean, 2.07; s.d., 1.21). After the CASA, there was a significant positive increase in intentions towards STI screening (mean, 0.33; s.d., 2.12) [t(547), −10.3; P < 0.001; Cohen’s d, 0.63], a significant increase in concerns about STIs (mean, 0.32; s.d., 2.17) [t(544), −4.96; P < 0.001; Cohen’s d, 0.30], and a significant increase in positive attitudes towards sexual health screening (mean, 2.36; s.d., 1.02) [t(543), −4.36; P < 0.001; Cohen’s d, 0.26] (Fig. 1).

Changes in attitudes and intentions for STI screening, and concern about STIs after chatbot conversation.

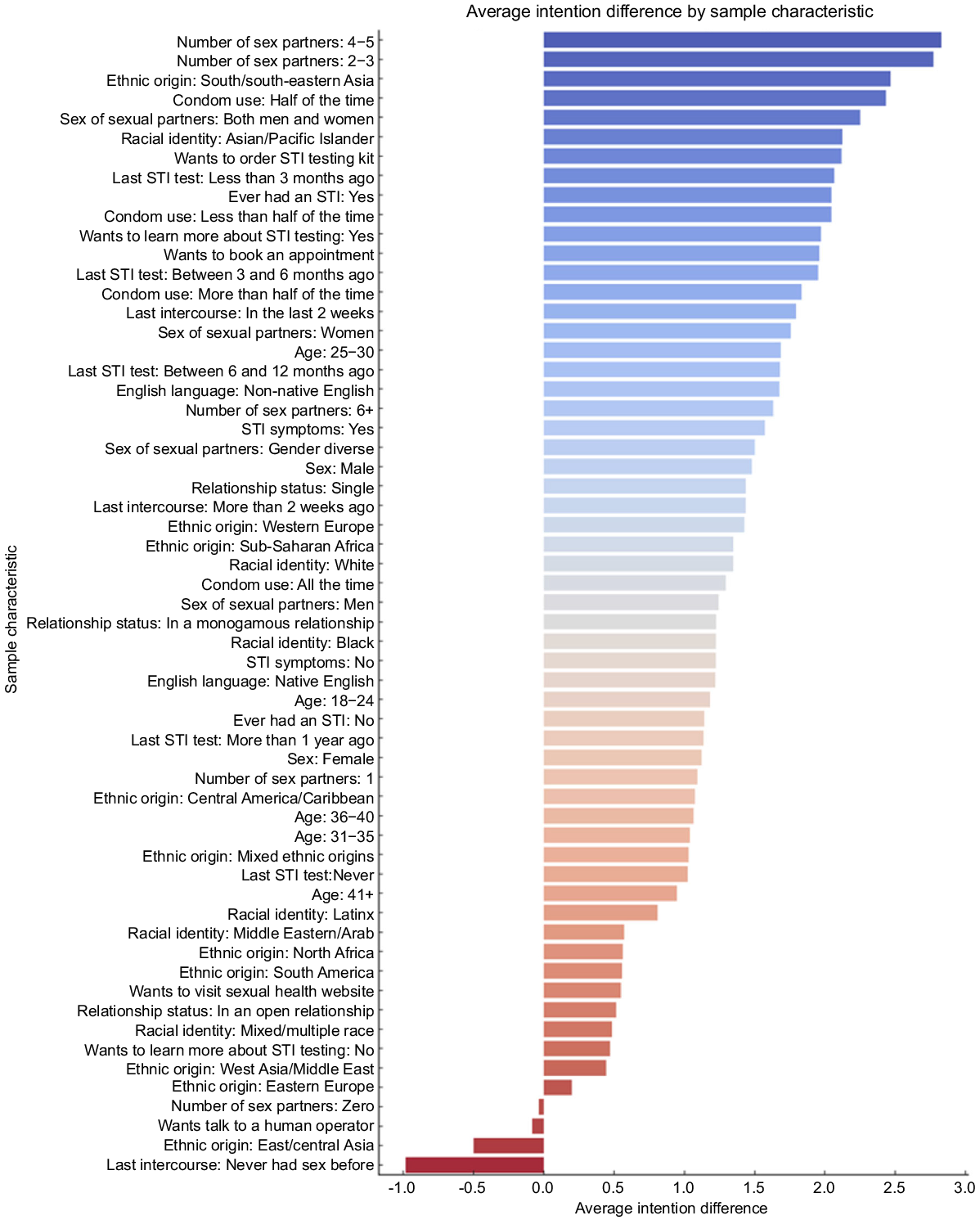

The analysis revealed statistically significant differences in intentions to screen for STI (Table 2). These increases in intentions were most pronounced amongst those who identified as Asian/Pacific Islander from south/south-eastern Asia, had sex in the past 2 weeks, reported having an STI symptom or being unsure, had a history of STI diagnosis, had sex with both men and women, had an STI test within 3 months, had four to five sexual partners since the last STI screening, and/or were a non-native English speaker. There were no differences in intentions by age, gender identity and relationship status (Fig. 2).

| N | % | Intention for STI screening (before chatbot) | Intention for STI screening (after chatbot) | Difference in intentions for STI screening | F statistic | P-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic and behavioural factor | % | Mean | s.d. | Mean | s.d. | |||||

| Relationship status | ||||||||||

| Single | 250 | 45.6 | −1.01 | 1.98 | 0.42 | 2.13 | 1.44 | F(3, 543) = 2.47 | P = 0.06 | |

| In a monogamous relationship | 258 | 47.1 | −1.09 | 1.95 | 0.14 | 2.10 | 1.22 | |||

| In an open relationship | 33 | 6 | 0.33 | 1.76 | 0.85 | 2.08 | 0.52 | |||

| English language | ||||||||||

| Native English | 473 | 86.3 | −0.98 | 1.99 | 0.24 | 2.11 | 1.22 | F(2, 544) = 3.06 | P = 0.02 | |

| Non-native English | 74 | 13.5 | −0.81 | 1.94 | 0.86 | 2.10 | 1.68 | |||

| Age (years) | ||||||||||

| 18–24 | 181 | 33 | −0.77 | 1.99 | 0.41 | 2.14 | 1.18 | F(5, 541) = 1.94 | P = 0.08 | |

| 25–30 | 168 | 30.7 | −1.08 | 2.00 | 0.61 | 2.17 | 1.68 | |||

| 31–35 | 99 | 18.1 | −0.94 | 1.91 | 0.10 | 1.96 | 1.04 | |||

| 36–40 | 60 | 10.9 | −1.18 | 1.88 | −0.12 | 2.03 | 1.07 | |||

| 41+ | 39 | 7.1 | −0.97 | 2.18 | −0.03 | 2.25 | 0.95 | |||

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Female | 294 | 53.6 | −0.95 | 1.94 | 0.17 | 2.16 | 1.12 | F(4, 542) = 1.61 | P = 0.17 | |

| Male | 243 | 44.3 | −1.00 | 2.02 | 0.48 | 2.05 | 1.48 | |||

| Racial identity | ||||||||||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 65 | 11.9 | −0.88 | 1.83 | 1.25 | 2.02 | 2.12 | F(8,538) = 3.108 | P = 0.001 | |

| Black | 361 | 65.9 | −1.00 | 1.98 | 0.22 | 2.05 | 1.22 | |||

| Latinx | 21 | 3.8 | −1.43 | 1.75 | −0.62 | 2.06 | 0.81 | |||

| Middle Eastern/Arab | 7 | 1.3 | 0.00 | 1.53 | 0.57 | 2.37 | 0.57 | |||

| Mixed/multiple race | 37 | 6.8 | −0.68 | 2.08 | −0.19 | 2.32 | 0.49 | |||

| White | 49 | 8.9 | −0.73 | 2.19 | 0.61 | 2.33 | 1.35 | |||

| Ethnic origin | ||||||||||

| West Asia/Middle East | 9 | 1.6 | −0.11 | 1.83 | 0.33 | 1.94 | 0.44 | F(12,534) = 1.864 | P = 0.03 | |

| South/south-eastern Asia | 60 | 10.9 | −1.13 | 1.69 | 1.33 | 1.96 | 2.47 | |||

| East/central Asia | 4 | 0.7 | 1.00 | 1.63 | 0.50 | 1.91 | −0.50 | |||

| Central America/Caribbean | 81 | 14.8 | −0.80 | 2.01 | 0.27 | 2.20 | 1.07 | |||

| South America | 18 | 3.3 | −1.11 | 1.88 | −0.56 | 2.04 | 0.56 | |||

| North Africa | 16 | 2.9 | −0.69 | 2.02 | −0.13 | 2.00 | 0.56 | |||

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 224 | 40.9 | −1.06 | 1.98 | 0.29 | 1.99 | 1.35 | |||

| Eastern Europe | 10 | 1.8 | −0.70 | 2.00 | −0.50 | 2.37 | 0.20 | |||

| Mixed ethnic origins | 32 | 5.8 | −0.94 | 2.27 | 0.09 | 2.28 | 1.03 | |||

| Western Europe | 63 | 11.5 | −1.08 | 2.10 | 0.35 | 2.36 | 1.43 | |||

| Last intercourse | ||||||||||

| Never had sex before | 59 | 10.8 | −0.41 | 2.03 | −1.39 | 2.01 | −0.98 | F(4,542) = 15.778 | P = 0.0001 | |

| In the past 2 weeks | 248 | 45.3 | −0.97 | 1.95 | 0.83 | 2.02 | 1.79 | |||

| More than 2 weeks ago | 223 | 40.7 | −1.14 | 1.96 | 0.29 | 2.02 | 1.43 | |||

| STI symptoms | ||||||||||

| Yes/not sure | 82 | 15 | −0.74 | 2.07 | 0.83 | 2.11 | 1.57 | F(2,546) = 6.73 | P = 0.01 | |

| No | 465 | 85 | −1.00 | 1.97 | 0.23 | 2.16 | 1.22 | |||

| Ever had an STI | ||||||||||

| Yes | 88 | 16.1 | −1.11 | 1.93 | 0.93 | 2.05 | 2.05 | F(2, 542) = 11.96 | P = 0.001 | |

| No | 403 | 73.5 | −1.00 | 1.98 | 0.14 | 2.16 | 1.14 | |||

| Sex of sexual partners | ||||||||||

| Women | 224 | 40.9 | −1.10 | 2.03 | 0.66 | 1.91 | 1.75 | F(6,540) = 7.844 | P = 0.001 | |

| Men | 238 | 43.4 | −0.96 | 1.89 | 0.29 | 2.13 | 1.24 | |||

| Both men and women | 20 | 3.6 | −0.75 | 2.15 | 1.50 | 2.06 | 2.25 | |||

| Gender diverse | 2 | 0.4 | −1.00 | 1.41 | 0.50 | 3.54 | 1.50 | |||

| Condom use | ||||||||||

| Less than half of the time | 45 | 8.2 | −1.16 | 1.99 | 0.89 | 1.94 | 2.04 | F(6,540) = 11.415 | P = 0.001 | |

| Half of the time | 53 | 9.7 | −0.85 | 2.08 | 1.58 | 1.43 | 2.43 | |||

| More than half of the time | 96 | 17.5 | −0.81 | 2.07 | 1.02 | 1.89 | 1.83 | |||

| All the time | 132 | 24.1 | −0.97 | 1.92 | 0.33 | 1.95 | 1.30 | |||

| Last STI test | ||||||||||

| Less than 3 months ago | 60 | 10.9 | −0.78 | 2.18 | 1.28 | 1.84 | 2.07 | F(6,540) = 4.344 | P = 0.001 | |

| Between 3 and 6 months ago | 41 | 7.5 | −1.15 | 1.90 | 0.80 | 1.94 | 1.95 | |||

| Between 6 and 12 months ago | 50 | 9.1 | −0.92 | 1.76 | 0.76 | 1.60 | 1.68 | |||

| More than 1 year ago | 131 | 23.9 | −1.09 | 1.96 | 0.05 | 2.17 | 1.14 | |||

| Never | 256 | 46.7 | −0.90 | 2.00 | 0.12 | 2.20 | 1.02 | |||

| Number of sex partners | ||||||||||

| Zero | 139 | 25.4 | −0.54 | 2.03 | −0.58 | 2.05 | −0.04 | F(6,540) = 14.384 | P = 0.001 | |

| One | 225 | 41.1 | −0.99 | 1.97 | 0.10 | 2.15 | 1.09 | |||

| Two to three | 118 | 21.5 | −1.33 | 1.90 | 1.44 | 1.63 | 2.77 | |||

| Four to five | 29 | 5.3 | −1.07 | 1.87 | 1.76 | 1.55 | 2.83 | |||

| Six or more | 19 | 3.5 | −1.11 | 1.97 | 0.53 | 1.95 | 1.63 | |||

| Want to learn more about STI testing | ||||||||||

| Yes | 295 | 53.8 | −1.05 | 1.92 | 0.92 | 1.83 | 1.97 | F(2,544) = 28.590 | P = 0.001 | |

| No | 252 | 46 | −0.85 | 2.04 | −0.37 | 2.23 | 0.47 | |||

| Anticipated action following conversation | ||||||||||

| Wants to visit sexual health website | 104 | 19 | −0.90 | 2.00 | −0.36 | 2.00 | 0.55 | F(5,541) = 17.189 | P = 0.001 | |

| Wants talk to a human operator | 12 | 2.2 | −0.17 | 2.41 | −0.25 | 2.14 | −0.08 | |||

| Wants to order STI testing kit | 240 | 43.8 | −1.05 | 1.94 | 1.06 | 1.97 | 2.12 | |||

| Wants to book an appointment | 49 | 8.9 | −0.94 | 1.99 | 1.02 | 1.68 | 1.96 | |||

Attitudes towards CASA

There were positive attitudes towards the CASA intervention (mean, 13.30; s.d., 6.73; range, −17 to 21; Table 3). Most thought that the chatbot helped them to understand their STI risk and decide whether they needed to undergo STI screening. The majority thought it was easy to use, were satisfied with the intervention and would recommend the chatbot to others like them. Attitudes differed by ethnic identity [F(6, 537), 2.78; P = 0.01]; post hoc comparisons found that those who identified as Asian had significantly more positive attitude scores than black participants. Attitudes did not differ by age group [F(4,542), 2.01; P = 0.09], gender [F(3,543), 1.64; P = 0.179], or relationship status [F(2,538), 1.66; P = 0.190]. Non-native English speakers had significantly more positive attitudes than native English speakers [t(545), −3.08; P = 0.001]. Attitudes differed significantly by current STI symptoms [F(2,479), 3.13; P = 0.04], those who were ‘not sure’ had more positive attitudes than those who had no symptoms. Attitude did not differ by previous STI test [F(3,475), 0.617; P = 0.604], but differed by condom use [F(3,484), 13.66, P = <0.001], with those who used condoms some of the time having a more positive attitude than those who never used condoms and those who preferred not to say. Those who reported having had two to three partners had more positive attitudes than those who had no partners or one sexual partner.

| Variable | Mean, s.d. | |

|---|---|---|

| Race** | ||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 15.89, 4.54 | |

| Black | 13.26, 6.36 | |

| Latino/a/x/Hispanic | 12.52, 8.21 | |

| Middle Eastern/Arab | 14.43, 4.79 | |

| Mixed/multiple | 11.10, 9.02 | |

| White | 13.04, 7.58 | |

| Other | 8.75, 4.99 | |

| Age group (years) | ||

| 18–24 | 14.09, 5.86 | |

| 25–30 | 13.44, 6.55 | |

| 31–35 | 12.75, 6.62 | |

| 36–40 | 12.53, 8.10 | |

| 41+ | 11.15, 8.68 | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 13.96, 6.66 | |

| Female | 12.74, 6.67 | |

| Non-binary | 12.80, 4.65 | |

| Other | 11.20, 12.61 | |

| Relationship status | ||

| Single | 13.35, 6.29 | |

| Monogamous relationship | 12.91, 7.22 | |

| Open relationship | 15.15, 5.73 | |

| Language** | ||

| Native English | 12.92, 6.91 | |

| Non-native English | 15.50, 4.94 | |

| STI symptoms* | ||

| Yes | 15.03, 5.43 | |

| No | 13.25, 7.02 | |

| Not sure | 15.9, 3.7 | |

| Previous STI* | ||

| Yes | 14.58, 6.55 | |

| No | 13.16, 6.97 | |

| Not sure | 15.13, 4.87 | |

| Previous STI test | ||

| Less than 3 months ago | 12.53, 7.78 | |

| 3–12 months | 13.42, 6.67 | |

| Over a year | 13.73, 6.4 | |

| Never | 13.85, 6.79 | |

| Condom use** | ||

| Never | 11.57, 8.04 | |

| Some | 15.46, 4.97 | |

| All | 13.85, 5.86 | |

| Prefer not to say | 9.34, 9.59 | |

| Sexual partners (past 12 months)** | ||

| None | 12.78, 6.87 | |

| 1 | 12.33, 7.16 | |

| 2–3 | 16.15, 4.96 | |

| 4+ | 14.17, 7.29 | |

*P < 0.01; **P < 0.001.

Chatbot script

The analysis of the Pat chatbot showed that out of 1066 HIV/STI test appointments booked with Positive East, 11% (N = 124) were made directly via the chatbot, with 72% of users identifying with MEGs. Overall, 42% of chatbot users searched for information about STI/HIV testing, 15% wanted to understand ‘when to test for STI/HIV’, 12% suspected having an STI and needed more information, and less than 5% searched for information about Mpox, contraception, HIV pre-and post-exposure prophylaxis, specific STI symptoms, test results, STI treatment and condoms, respectively.

Discussion

Findings indicate that chatbot-assisted self-assessment had a positive impact on the motivation to screen for STIs in ethnically diverse communities. Chatbot that imitates sexual history-taking and explains the purpose of each question can increase concerns about STIs, create positive attitudes and encourage intentions for sexual health screening in those more susceptible to STIs/HIV. The intervention was also well-received, indicating high acceptability. Additionally, data from the Pat chatbot showed that booking screening appointments through this technology is an acceptable way of accessing relevant healthcare services such as sexual health education and screening. Our simulation study provides evidence on the feasibility and effectiveness of conversational AI technology for sexual health and its potential to reduce health inequalities among ethnic minority populations.

There are several explanations for these observations. The CASA provides a non-judgemental and anonymous space for individuals from MEGs to share relevant information about personal sexual behaviour without fear of judgement, which may be present in face-to-face interactions.17 Similarly, the intervention ensures consistency in the way information is presented, regardless of the user’s ethnicity or background. This standardisation can help avoid unintentional biases or cultural insensitivities that might occur in human interactions. The CASA was designed to adapt its language, tone, and content in an inclusive way reflective of various cultural backgrounds, which was incorporated in our two-question approach about ethnic identity and origin, making the interaction more relatable.18 Participants who were not native English speakers showed a higher intention to get screened for STIs, compared to those who were native English speakers, suggesting that CASA might be helpful for individuals who experience language barriers when accessing healthcare services.27 By creating a private and confidential environment to discuss STIs and sexual health, chatbots could potentially reduce the stigma associated with these health topics.28 This could help individuals feel more comfortable seeking screening services. Additionally, CASA was designed to provide instant feedback and information based on the responses given by the user. This immediacy could encourage self-reflection and help educate individuals about their risks and the importance of STI screening right when they might be most receptive.29,30 The CASA intervention, in combination with a chatbot for sexual health information and booking STI screening, could allow users to reduce indecisions about STI testing and nudge them to seek appropriate services.

The largest increase in the intention for STI screenings was observed in those who had been previously diagnosed with an STI, had a higher number of sexual partners, reported inconsistent condom use as well as those who had sex with both men and women. Conversely, the STI screening intentions were the lowest among participants who had never had sex before or reported ‘zero’ sexual partners since the last STI check-up. The results indicate that automated history-taking via chatbot can reduce indecision for STI screening in those at higher risk of STIs, while this effect does not seem to occur for people who are at lower risk of STIs. This supports previous research showing that computer-assisted self-interview sexual history improved detection of STIs.31 Also, this may be due to the ‘question-behaviour effect’ in which the act of questioning users about their sexual health per se could be a cue to action for seeing STI screening.24 Also, the sex-positive and encouraging language of the chatbot could remind users about their eligibility for STI screening, instead of focusing on their risk of STIs and associated stigma.32 By asking demographic and behavioural questions, chatbots can subtly educate users about risk factors and the importance of screening, leading to increased awareness and motivation to get screened. Many people from MEGs are still unaware of different ways they can test for STIs/HIV, including remote STI testing kits and community-based testing as part of a charity outreach.33 Additionally, repeated interaction with e-health interventions such as chatbots about sexual health could normalise the topic, reducing associated fears and stigmas.34 Positive reinforcement and affirmations from chatbots can bolster an individual’s self-worth and confidence, making them more likely to take positive health actions.35 Therefore, the chatbot might have raised their awareness about various services available to them, which was reflected in their willingness to learn more about sexual health.

The large majority of the participants were willing to disclose demographic and sensitive information to the chatbot. confirming our expectations.18 There was a relatively higher rate of non-disclosure to the question related to condom use. This could be due to the ambiguity surrounding the appropriate response for individuals who are not sexually active or are in a monogamous relationship. Therefore, this question requires further development to eliminate any potential uncertainty. Nevertheless, such high levels of disclosure to chatbots have been reported in previous studies, suggesting that by interacting with a chatbot, the pressure to conform to social norms or to give answers deemed ‘acceptable’ might be reduced. Chatbots’ lack of emotions or anticipated biases may lead to more candid responses.36

Limitations and further implications

The CASA intervention was created with input from diverse groups, which may explain why it was well received in this study and has the potential for broader use. One of the study’s strengths was the application of two chatbot services: the anonymous CASA and the confidential Pat, which was able to answer additional questions about STI testing and book appointments automatically, making sexual health services more accessible. Our previous research indicated that users were more willing to discuss their sexual behaviours if chatbots were anonymous. As a result, we implemented a two-chatbot design; however, due to technical and ethical issues, it was not feasible to trace an individual user’s journey from the automated sexual history taking to the STI screening test results. Thus, we were unable to report the impact of chatbots on appointment booking and uptake of sexual health screening, that goes beyond motivations and intentions. Nevertheless, our simulation study provides insights into the ecological validity of this intervention. Users from a wide spectrum of STI susceptibility can discuss their sexual health with chatbots, making the findings more generalisable in a wider context. Future randomised controlled trials are needed to understand the impact of the CASA on uptake of screening and overall STI/HIV rates in MEGs.

We used a within-subject design to examine the effect of CASA on individuals’ motivation to undergo STI screening. However, carryover effects may confound the results, as participants’ responses may be influenced by their previous experiences of the three measurements.35 Despite this, the results showed that those who were not sexually active reported reduced STI screening intentions, indicating minimal impact of such effects. Although a wide range of recruitment methods, e.g. online and community-based, were used in the study to reach ‘seldom heard’ populations suspectable to STIs and HV, the recruitment process raises concerns about potential selection bias as the participants were mainly sourced from social media channels and locations, which may not represent the broader UK population. However, the rate of those who had never tested for STIs in our sample is comparable to rates seen in the UK, indicating the potential representativeness of the findings.37 Also, using chatbot interventions may make it difficult to reach the most underserved groups that lack access to technology or the Internet. Future research should address this digital divide to ensure all populations can access AI-powered interventions. Additionally, self-reported data may be subject to social desirability bias, which may affect the accuracy of the results.38 Nevertheless, this bias may be less relevant in digital interventions where concerns about human judgement are eliminated. Further, the study was not designed to track actual behaviour post-intervention, which limits the ability to draw causal inferences regarding the impact of CASA. Therefore, future research should focus on providing evidence of the impact of CASA on individual motivation, behaviour, and STI screening uptake.

The evidence that CASA can enhance motivation for STI screening highlights the importance of leveraging technological advancements to address health inequalities. The chatbot’s ability to mimic sexual history-taking and articulate the rationale behind each query appears to have the effect of increasing concern about STIs and fostering positive attitudes, which are essential precursors to action in health-seeking behaviours. Notably, the increased intention to engage in sexual health screening among those susceptible to STIs/HIV suggests that such digital interventions could be particularly effective in targeting at-risk populations. The study’s finding of high acceptability and the preference for booking appointments through conversational AI suggests that such technologies can play a crucial role in facilitating easier access to healthcare services. This aligns with the wider digital transformation of health care and points towards a future where AI augments provision of health care to meet diverse patient needs.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Dr Tom Nadarzynski, upon reasonable request. Due to privacy and ethical restrictions, the dataset cannot be made publicly available. Interested researchers may contact t.nadarzynski@westminster.ac.uk with requests for data access, which will be considered in line with the study’s ethical approval stipulations and in compliance with applicable data protection regulations.

Declaration of funding

This report is independent research funded by NHS AI Lab and The Health Foundation and it is managed by the National Institute for Health Research (AI_HI200028). The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS AI Lab, The Health Foundation, National Institute for Health Research, or the Department of Health and Social Care.

References

1 World Health Organization. Global health sector strategy on sexually transmitted infections 2016–2021. 2016. Available at https://www.paho.org/en/documents/global-health-sector-strategy-sexually-transmitted-infections-2016-2021-towards-ending#:~:text=The%20present%20global%20health%20sector,goals%2C%20targets%2C%20guiding%20principles%20and [Retrieved 1 November 2023]

2 Fu L, Sun Y, Han M, Wang B, Xiao F, Zhou Y, Gao Y, Fitzpatrick T, Yuan T, Li P, Zhan Y, Lu Y, Luo G, Duan J, Hong Z, Fairley CK, Zhang T, Zhao J, Zou H. Incidence trends of five common sexually transmitted infections excluding HIV from 1990 to 2019 at the global, regional, and national levels: results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Front Med 2022; 9: 851635.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

3 Lieberman JA, Cannon CA, Bourassa LA. Laboratory perspective on racial disparities in sexually transmitted infections. J Appl Lab Med 2021; 6(1): 264-273.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

4 Public Health England. Public Health England COVID-19: impact on STIs, HIV and viral hepatitis. 2020. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-impact-on-stis-hiv-and-viral-hepatitis [Retrieved 1 November 2023]

5 Wayal S, Hughes G, Sonnenberg P, Mohammed H, Copas AJ, Gerressu M, Tanton C, Furegato M, Mercer CH. Ethnic variations in sexual behaviours and sexual health markers: findings from the third British National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal-3). Lancet Public Health 2017; 2(10): e458-e472.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

6 FitzGerald C, Hurst S. Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: a systematic review. BMC Med Ethics 2017; 18(1): 1-18.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

7 Hunt D-W, Dhairyawan R, Sowemimo A, Nadarzynski T, Nwaosu U, Briscoe-Palmer S, Heskin J, Lander F, Rashid T. Sexual health in the UK: the experience of racially minoritised communities and the need for stakeholder input. Sex Transm Infect 2023; 99(3): 211-212.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

8 Whelan I, Strachan S, Apea V, Orkin C, Paparini S. Barriers and facilitators to HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis for cisgender and transgender women in the UK. Lancet HIV 2023; 10: e472-e481.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

9 Nwaosu U, Raymond-Williams R, Meyrick J. Are psychosocial interventions effective at increasing condom use among Black men? A systematic review. Int J STD AIDS 2021; 32(12): 1088-1105.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

10 Sumray K, Lloyd KC, Estcourt CS, Burns F, Gibbs J. Access to, usage and clinical outcomes of, online postal sexually transmitted infection services: a scoping review. Sex Transm Infect 2022; 98(7): 528-535.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

11 Brayboy LM, McCoy K, Thamotharan S, Zhu E, Gil G, Houck C. The use of technology in the sexual health education especially among minority adolescent girls in the United States. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2018; 30(5): 305-309.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

12 Teadt S, Burns JC, Montgomery TM, Darbes L. African American adolescents and young adults, new media, and sexual health: scoping review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2020; 8(10): e19459.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

13 Owusu MW, De Mesa MEF, Mohammed H, Gerressu M, Hughes G, Mercer CH. Race to address sexual health inequalities among people of Black Caribbean heritage: could co-production lead to more culturally appropriate guidance and practice? Sex Transm Infect 2023; 99: 293-295.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

14 Balaji D, He L, Giani S, Bosse T, Wiers R, de Bruijn G-J. Effectiveness and acceptability of conversational agents for sexual health promotion: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex Health 2022; 19(5): 391-405.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

15 Young SD, Crowley JS, Vermund SH. Artificial intelligence and sexual health in the USA. Lancet Digit Health 2021; 3(8): e467-e468.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

16 Nadarzynski T, Lunt A, Knights N, Bayley J, Llewellyn C. “But can chatbots understand sex?” Attitudes towards artificial intelligence chatbots amongst sexual and reproductive health professionals: an exploratory mixed-methods study. Int J STD AIDS 2023; 19: 391-405.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

17 Mills R, Mangone ER, Lesh N, Mohan D, Baraitser P. Chatbots to improve sexual and reproductive health: realist synthesis. J Med Internet Res 2023; 25: e46761.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

18 Nadarzynski T, Knights N, Husbands D, Graham CG, Llewellyn CD, Buchanan T, Montgomery I, Rodriguez AS, Ogueri C, Singh N, Oyebode O, et al. Chatbot-assisted self-assessment (CASA): designing a novel AI-enabled sexual health intervention for racially minoritised communities. BMJ STI 2023; 99(1): A60-A61.

| Google Scholar |

19 Milne-Ives M, de Cock C, Lim E, Shehadeh MH, de Pennington N, Mole G, Normando E, Meinert E. The effectiveness of artificial intelligence conversational agents in health care: systematic review. J Med Internet Res 2020; 22(10): e20346.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

20 Ho A, Hancock J, Miner AS. Psychological, relational, and emotional effects of self-disclosure after conversations with a chatbot. J Commun 2018; 68(4): 712-733.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

21 Aggarwal A, Tam CC, Wu D, Li X, Qiao S. Artificial intelligence–based chatbots for promoting health behavioral changes: systematic review. J Med Internet Res 2023; 25: e40789.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

22 van Wezel MM, Croes EA, Antheunis ML. “I’m here for you”: can social chatbots truly support their users? A literature review. In ‘Chatbot Research and Design: 4th International Workshop, CONVERSATIONS 2020, Virtual Event, November 23–24, 2020, Revised Selected Papers 4’. Springer International Publishing; 2021. pp. 96–113.

23 Wilding S, Conner M, Sandberg T, Prestwich A, Lawton R, Wood C, Miles E, Godin G, Sheeran P. The question-behaviour effect: a theoretical and methodological review and meta-analysis. Eur Rev Soc Psychol 2016; 27(1): 196-230.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

24 Rodrigues AM, O’Brien N, French DP, Glidewell L, Sniehotta FF. The question–behavior effect: genuine effect or spurious phenomenon? A systematic review of randomized controlled trials with meta-analyses. Health Psychol 2015; 34(1): 61.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

25 Nadarzynski T, Puentes V, Pawlak I, Mendes T, Montgomery I, Bayley J, Ridge D, Newman C. Barriers and facilitators to engagement with artificial intelligence (AI)-based chatbots for sexual and reproductive health advice: a qualitative analysis. Sex Health 2021; 18(5): 385-393.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

26 Abelson J, Wagner F, DeJean D, Boesveld S, Gauvin F-P, Bean S, Axler R, Petersen S, Baidoobonso S, Pron G, Giacomini M, Lavis J. Public and patient involvement in health technology assessment: a framework for action. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2016; 32(4): 256-264.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

27 Sallam M. ChatGPT utility in healthcare education, research, and practice: systematic review on the promising perspectives and valid concerns. Healthcare 2023; 11(6): 887 10.3390/healthcare11060887.

| Google Scholar |

28 Branley-Bell D, Brown R, Coventry L, Sillence E. Chatbots for embarrassing and stigmatizing conditions: could chatbots encourage users to seek medical advice? Front Commun 2023; 8: 1275127.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

29 Yam EA, Namukonda E, McClair T, Souidi S, Chelwa N, Muntalima N, Mbizvo M, Bellows B. Developing and testing a chatbot to integrate HIV education into family planning clinic waiting areas in Lusaka, Zambia. Glob Health Sci Pract 2022; 10(5): e2100721.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

30 O’Byrne P, Musten A, Orser L, Buckingham S. Automated STI/HIV risk assessments: testing an online clinical algorithm in Ottawa, Canada. Int J STD AIDS 2021; 32(14): 1365-1373.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

31 Chapman KS, Gadkowski LB, Janelle J, Koehler-Sides G, Nelson JA. Automated sexual history and self-collection of extragenital chlamydia and gonorrhea improve detection of bacterial sexually transmitted infections in people with HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2022; 36(S2): 104-110.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

32 Brickman J, Willoughby JF. ‘You shouldn’t be making people feel bad about having sex’: exploring young adults’ perceptions of a sex-positive sexual health text message intervention. Sex Educ 2017; 17(6): 621-634.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

33 Gasmelsid N, Moran BCB, Nadarzynski T, Patel R, Foley E. Does online sexually transmitted infection screening compromise care? A service evaluation comparing the management of chlamydial infection diagnosed online and in clinic. Int J STD AIDS 2021; 32(6): 528-532.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

34 Zhang L, Ni Z, Liu Y, Chen H. The effectiveness of e-health on reducing stigma, improving social support and quality of life among people living with HIV: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Nurs Stud 2023; 148: 104606.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

35 Luk TT, Lui JHT, Wang MP. Efficacy, usability, and acceptability of a chatbot for promoting COVID-19 vaccination in unvaccinated or booster-hesitant young adults: pre-post pilot study. J Med Internet Res 2022; 24(10): e39063.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

36 Zhai C, Wibowo S. A systematic review on cross-culture, humor and empathy dimensions in conversational chatbots: the case of second language acquisition. Heliyon 2022; 8: e12056.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

37 UK Health Security Agency. A look at the sexual health of young Londoners. 2016. Available at https://ukhsa.blog.gov.uk/2016/09/22/a-look-at-the-sexual-health-of-young-londoners/ [accessed 1 November 2023]

38 Reddy H, Joshi S, Joshi A, Wagh V. A critical review of global digital divide and the role of technology in healthcare. Cureus 2022; 14(9): e29739.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |