A typology of HIV self-testing support systems: a scoping review

Arron Tran A B , Nghiep Tran A , James Tapa B , Warittha Tieosapjaroen

A B , Nghiep Tran A , James Tapa B , Warittha Tieosapjaroen  B C , Christopher K. Fairley

B C , Christopher K. Fairley  B C , Eric P. F. Chow

B C , Eric P. F. Chow  B C D , Lei Zhang

B C D , Lei Zhang  B C , Rachel C. Baggaley E , Cheryl C. Johnson E , Muhammad S. Jamil F and Jason J. Ong

B C , Rachel C. Baggaley E , Cheryl C. Johnson E , Muhammad S. Jamil F and Jason J. Ong  B C F *

B C F *

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

Abstract

To maximise the benefits of HIV self-testing (HIVST), it is critical to support self-testers in the testing process and ensure that they access appropriate prevention and care. To summarise systems and tools supporting HIVST (hereafter, ‘support systems’) and categorise them for future analysis, we synthesised the global data on HIVST support systems and proposed a typology. We searched five databases for articles reporting on one or more HIVST support systems and included 314 publications from 224 studies. Across 189 studies, there were 539 reports of systems supporting HIVST use; while across 115 studies, there were 171 reports of systems supporting result interpretation. Most commonly, these were pictorial instructions, followed by in-person demonstrations and in-person assistance while self-testing or reading self-test results. Less commonly, virtual interventions were also identified, including online video conferencing and smartphone apps. Smartphone-based automated result readers have been used in the USA, China, and South Africa. Across 173 studies, there were 987 reports of systems supporting post-test linkage to care; most commonly, these were in-person referrals/counselling, written referrals, and phone helplines. In the USA, Bluetooth beacons have been trialled to monitor self-test use and facilitate follow-up. We found that, globally, HIVST support systems use a range of methods, including static media, virtual tools, and in-person engagement. In-person and printed approaches were more common than virtual tools. Other considerations, such as linguistic and cultural appropriateness, may also be important in the development of effective HIVST programs.

Keywords: HIV screening, HIV/AIDS, linkage to care, result interpretation, self-testing, support system, typology, virtual.

Introduction

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) has set a 2025 target for 95% of all people with HIV to be diagnosed, with 95% of these people on treatment and 95% of these having suppressed viral loads.1 Although laboratory and rapid tests are effective and widely accepted HIV testing approaches, opportunities to further decentralise HIV testing can help accelerate efforts to reach this target, especially among priority populations such as men who have sex with men (MSM) and adolescent girls and young women (AGYW). HIV self-testing (HIVST) involves an individual performing and interpreting their own HIV rapid test with an oral fluid or fingerprick sample in a location of their choosing (e.g. at home), with the aims of increasing self-awareness of HIV status and subsequently linking to services such as HIV care and prevention. HIVST is a highly accurate screening tool when correctly performed, however any reactive results must still be confirmed by a trained tester using a validated testing algorithm to confirm a diagnosis of HIV.2 Nonetheless, it is a testing modality that can overcome barriers to facility-based HIV testing, such as those related to privacy and accessibility.3

HIVST can improve the uptake of confirmatory HIV testing and initiation of antiretroviral treatment (ART) for those testing positive,2,4 as well as support initiation and continuation of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for those with a non-reactive result.5 In 2016, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended HIVST to complement existing HIV testing services.2 Since then, there has been a substantial scale-up of HIVST, with more than 100 countries reporting relevant policies and implementation.6

While HIVST is accurate and acceptable,7 successful implementation requires appropriate systems (hereafter, ‘support systems’) to support self-testers. Support systems can include assistance performing a self-test (e.g. video instructions), interpreting the result (e.g. technology-assisted interpretation), and linking to the appropriate post-test services (e.g. counselling via live video conferencing). A 2018 systematic review found that laypeople can conduct their own self-tests with similar accuracy to healthcare workers; however, user error was still found.4 Therefore, there may exist a sub-population of HIVST users that would benefit from additional support, especially in settings where HIVST is new or where people have not used self-test kits before. Furthermore, HIVST changes how individuals and providers receive and deliver referrals, post-test support and linkage to appropriate HIV treatment and prevention services, which has raised concern for policymakers and self-testers about how HIVST users will be linked to sexual health services.8,9 Because self-testing increases privacy and confidentiality, individuals are not required to share their results or experience, making ongoing monitoring challenging for programs. Being able to link with individuals to collect data can help inform national and regional surveillance, but this must be balanced with the strength of HIVST in its privacy and confidentiality. Therefore, effective post-test support systems should support those with a reactive result to be linked to timely confirmatory testing and treatment services, with appropriate psychosocial support where needed.2 Those with non-reactive results should understand the importance of re-testing if at ongoing HIV risk and be supported to link to prevention services, such as PrEP, where appropriate.2

There are some systematic reviews related to support systems for HIVST. One examined methods to verify if HIVST users were linked to care,10 while another systematic review summarised the evidence relating to digital HIV self-testing supports.11 Another systematic review classified HIVST support tools related to instructions, demonstrations, observations, and supervision.12 However, to our knowledge, no attempts have been made to specifically examine HIVST support systems across all modalities and categorise them. The lack of a categorisation framework limits the possibility of a comprehensive systematic review. Therefore, the proposal of a categorisation system could enable analysis of the effectiveness of support systems in terms of accuracy of use and linkage to care, thereby allowing programs to select and develop support systems that best suit their local population and regional context. To this end, we sought to describe and understand the current landscape of HIVST support systems. Here, we conducted a global review to develop a typology for HIVST support systems assisting people to navigate the self-testing process.

Materials and methods

We conducted a global review following the framework of Arksey and O’Malley,13 and reported them according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR).14 The process involved comprehensively searching and screening the current literature, extracting data from primary studies, synthesising the results and summarising the evidence.

Search strategy and study selection

Our search strategy used terms related to the two overarching themes of HIV and self-testing, which were adapted for each database. We searched the following databases from January 2000 to March 2022: CINAHL Allied Health; Embase; MEDLINE; Scopus; and Web of Science. For a detailed search strategy, see Supplementary material file S1. We included primary studies that described and implemented one or more support systems for users of HIVST kits to use the test, interpret the results, or be linked to relevant services after performing the test. We excluded studies not available in English, those that did not conduct HIVST, or those where a support system was described but not implemented.

During the screening phase, duplicate studies were removed using Covidence and EndNote, and each abstract was assessed for eligibility by two independent reviewers (of AT, NT, or JT). Any discrepancies were assessed by a third reviewer (JO). Two reviewers (of AT, NT, or JT) completed data extraction independently, with a third reviewer (JO) checking for accuracy and resolving any conflicts.

Data synthesis

The following data were extracted: authors’ names; year of publication; article title; study site; study setting; study type; study population; support systems for test usage; result interpretation; and post-test linkage. We defined a ‘support system’ as any system or tool that assists an HIVST user in performing the self-test, interpreting the result, or being linked to follow-up services such as treatment and PrEP. While all HIVST kits include manufacturer instructions for use (IFU), we only reported support systems that were explicitly described. Study authors were contacted by email where information about support systems was unclear.

Measures of frequency (count, percentages) were used to summarise the characteristics of the included articles. To develop our typology, we used an inductive thematic analysis to identify categories of support systems for each stage of the self-testing process. After extracting qualitative data on support systems, we identified both broad categories and more specific sub-categories de novo, which were inductively refined as each support system was coded. These nested categories were then reviewed against their relevance to the support of HIVST, and any support systems or categories deemed irrelevant were removed.

Where possible when quantitatively reporting frequency, we first linked articles reporting on the same study, program, or trial (hereafter, ‘studies’). Our data focuses on studies rather than articles to minimise the impact on our results of multiple articles reporting on the same study and support systems.

Results

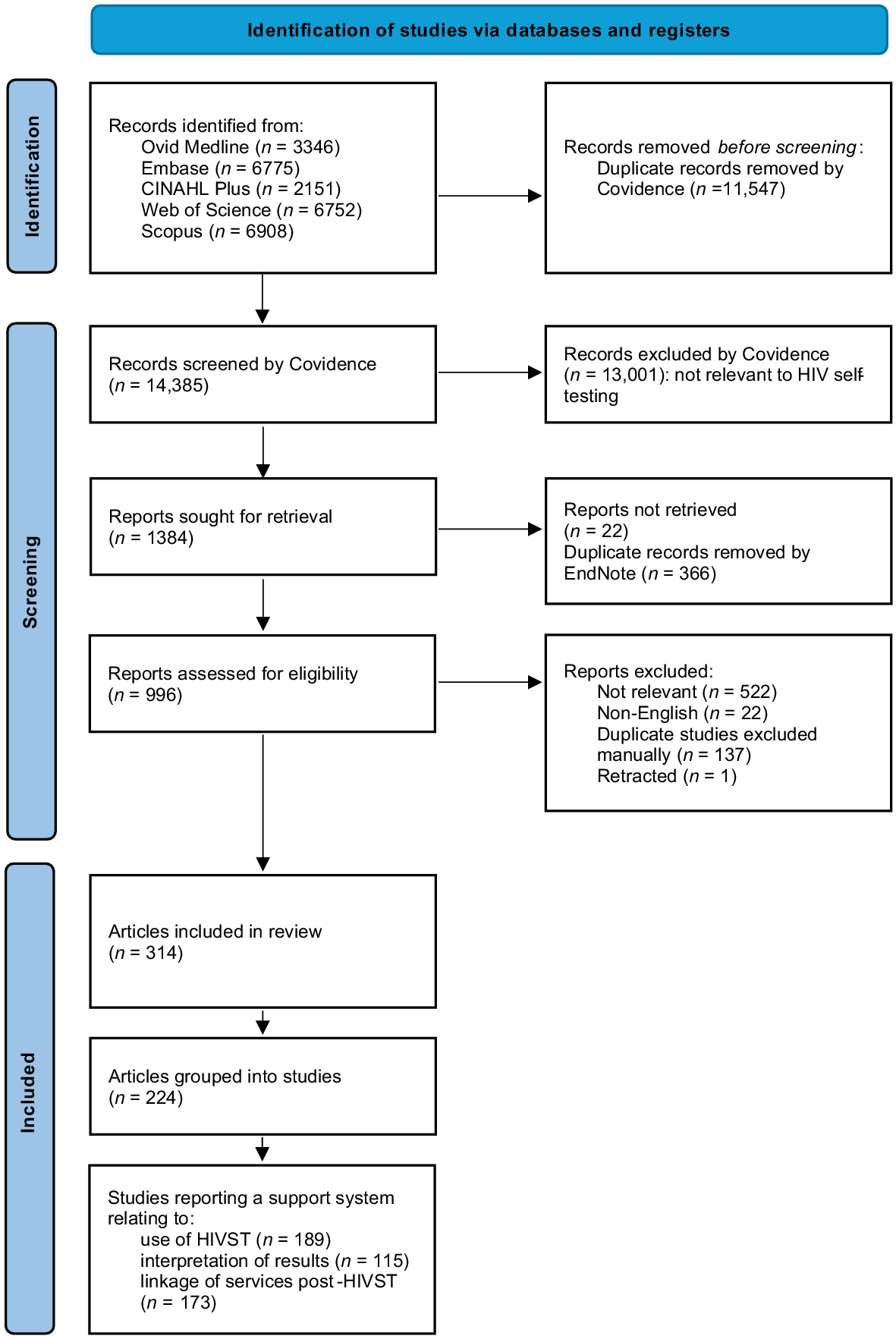

We screened 14,385 abstracts and assessed 996 full-text articles; 314 articles (representing 224 studies) were included in this review (Fig. 1). While studies from eastern and southern Africa were the most common (n = 101, 45.1%), studies were evenly distributed across country income level (Table 1). The latest publication date of the majority of studies (n = 203, 90.6%) was after the 2016 WHO guidelines on HIVST were published;2 35 (15.6%) studies used an experimental or comparative study design; and 84 studies included MSM (37.5%) (Table 1). A list of included studies and their characteristics is in Supplementary material file S2.

| Articles | Studies | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Region of the world | |||||

| Eastern and southern Africa | 157 | 50.0 | 101 | 45.1 | |

| Western and central Europe and North America | 83 | 26.4 | 62 | 27.7 | |

| Asia-Pacific | 47 | 15.0 | 42 | 18.8 | |

| Western and central Africa | 18 | 5.7 | 15 | 6.7 | |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | 13 | 4.1 | 6 | 2.7 | |

| Eastern Europe and central Asia | 1 | 0.3 | 1 | 0.4 | |

| Middle-East and north Africa | 1 | 0.3 | 1 | 0.4 | |

| Country income level | |||||

| High | 91 | 29.0 | 69 | 30.8 | |

| Upper-middle | 80 | 25.5 | 62 | 27.7 | |

| Lower-middle | 72 | 22.9 | 54 | 24.1 | |

| Low | 80 | 25.5 | 47 | 21.0 | |

| Latest year of publication | |||||

| 2021–March 2022 | 105 | 33.4 | 87 | 38.8 | |

| 2016–2020 | 182 | 58.0 | 116 | 51.8 | |

| 2011–2015 | 26 | 8.3 | 20 | 8.9 | |

| 2000–2010 | 1 | 0.3 | 1 | 0.4 | |

| Study type | |||||

| Experimental | 113 | 36.0 | 35 | 15.6 | |

| Non-experimental | 203 | 64.6 | 191 | 85.3 | |

| Study population | |||||

| MSM | 113 | 36.0 | 84 | 37.5 | |

| General population | 70 | 22.3 | 50 | 22.3 | |

| FSW | 35 | 11.1 | 24 | 10.7 | |

| Pregnant/postpartum | 21 | 6.7 | 16 | 7.1 | |

| Young people | 16 | 5.1 | 15 | 6.7 | |

| AGYW | 8 | 2.5 | 7 | 3.1 | |

| PWUD | 7 | 2.2 | 7 | 3.1 | |

| OtherA | 86 | 27.4 | 74 | 33.0 | |

Regions of the world are according to the UNAIDS classification.

‘Articles’ refer to individual papers; ‘studies’ refer to the number of unique studies, programs, or trials (which can include multiple articles).

MSM, men who have sex with men; FSW, female sex worker; AGYW, adolescent girls and young women; PWUD, people who use drugs.

Seventy (31.2%) studies reported a support system in a language other than English. These included both official languages,15 as well as local or regional languages.16 Choice of language was sometimes possible; for example, a study in the Democratic Republic of Congo provided a leaflet adapted and translated from the manufacturer IFU to be easy to read in French, Lingala and Swahili,17 and a South African phone helpline provided support in all 11 official languages.18 Some support systems were also specifically adapted to be relevant to local and specific contexts: a Tanzanian randomised controlled trial (RCT) in young people used a young female Tanzanian actor who provided instructions in Swahili,19 and a Swazi implementation study filmed video instructions in English and siSwati, with male and female versions.20

Support systems for the use of HIVST kits

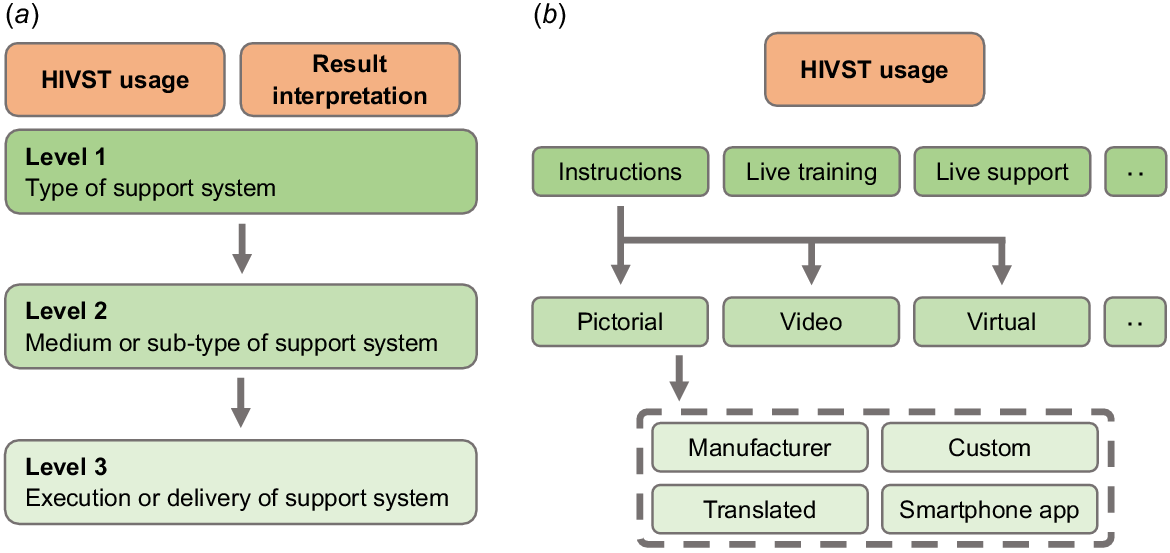

A three-level classification was developed (Fig. 2). The levels descend in hierarchy, and relate to the type of support system, its medium, and execution or delivery, respectively. For example, instructions (Level 1) may have been pictorial or a video (Level 2), which may have been produced by the manufacturer or custom-made for the program (Level 3). Across 189 studies, systems supporting HIVST use were reported 539 times (Table 2). These systems are in Table 3.

Typology structure for support systems for HIVST usage and result interpretation. (a) Visual representation of the typology hierarchy. (b) Example of the typology for HIVST usage.

| Support system | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Instructions | 243 | 45.1 | |

| Pictorial | 126 | 51.9 A | |

| Manufacturer | 49 | 38.9 B | |

| Custom | 30 | 23.8 | |

| Smartphone app | 7 | 5.6 | |

| Translated into a different language | 4 | 3.2 | |

| Online | 2 | 1.6 | |

| Unspecified | 34 | 27.0 | |

| Video | 68 | 28.0 | |

| Online URL | 28 | 31.2 | |

| Video shown at the time | 22 | 32.4 | |

| Smartphone app | 12 | 17.6 | |

| Available on-site | 2 | 2.9 | |

| USB | 1 | 1.5 | |

| Unspecified | 3 | 4.4 | |

| Virtual | 2 | 0.8 | |

| Smartphone app | 1 | 50.0 | |

| Chatbot | 1 | 50.0 | |

| Unspecified | 47 | 19.3 | |

| In-person live training | 97 | 18.0 | |

| Demonstration/instructions only | 80 | 82.5 | |

| Trained professional | 53 | 66.3 | |

| Trained peer | 14 | 17.5 | |

| Trained layperson | 7 | 8.8 | |

| Unspecified | 6 | 7.5 | |

| Interactive training | 11 | 11.3 | |

| Trained professional | 4 | 33.3 | |

| Trained peer | 4 | 33.3 | |

| Trained layperson | 2 | 16.7 | |

| Unspecified | 1 | 8.3 | |

| Other | 4 | 4.1 | |

| Instructions re-read in the local language | 1 | 25.0 | |

| Using a visual model | 1 | 25.0 | |

| Assistance with setting up the app | 1 | 25.0 | |

| Self-tester able to ask questions | 1 | 25.0 | |

| Unspecified | 2 | 2.0 | |

| Live support | 150 | 27.8 | |

| In-person support | 71 | 47.3 | |

| Trained professional | 48 | 67.6 | |

| Trained peer | 17 | 23.9 | |

| Trained layperson | 4 | 5.6 | |

| Untrained peer | 1 | 1.4 | |

| Unspecified | 1 | 1.4 | |

| Phone support | 61 | 40.7 | |

| Trained professional | 39 | 63.9 | |

| Trained peer | 3 | 4.9 | |

| Manufacturer helpline | 3 | 4.9 | |

| Trained layperson | 1 | 1.6 | |

| Unspecified | 15 | 24.6 | |

| Live chat | 10 | 6.7 | |

| Trained professional | 9 | 90.0 | |

| Unspecified | 1 | 10.0 | |

| Online live video support | 6 | 4.0 | |

| Trained professional | 5 | 83.3 | |

| Trained peer | 1 | 16.7 | |

| Unspecified | 2 | 1.3 | |

| Social network | 42 | 7.8 | |

| Partners | 29 | 69.0 | |

| Trained to test | 14 | 48.3 | |

| Trained to test and distribute | 12 | 41.4 | |

| Trained to distribute | 2 | 6.9 | |

| No training specified | 1 | 3.4 | |

| Peers | 9 | 21.4 | |

| No training specified | 4 | 44.4 | |

| Trained to test | 3 | 33.3 | |

| Trained to test and distribute | 1 | 11.1 | |

| Trained to distribute | 1 | 11.1 | |

| Household members | 2 | 4.8 | |

| Trained to test | 1 | 50.0 | |

| No training specified | 1 | 50.0 | |

| Other social networks | 2 | 4.8 | |

| Trained to test and distribute | 2 | 100 | |

| Other | 7 | 1.3 | |

| Other tools | 6 | 85.7 | |

| Timer/clock provided | 5 | 83.3 | |

| Earbuds | 1 | 16.7 | |

| Reimbursement/incentive | 1 | 14.3 | |

| Internet data access voucher | 1 | 100 |

Three levels are represented, with indents denoting a sub-level in the typology. Percentage frequencies are based on the count of the associated parent level. Grand total n = 539 reports of support systems.

| Support system | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| Instructions | Instructions which did not involve interaction with a person. | |

| Pictorial | Pictorial instructions using printed or digital media. Manufacturer IFUs were classified as pictorial by default. Custom instructions were those developed specifically for the study, such as those using simplified language. Also includes instructions described as ‘written’. | |

| Video | Video instructions may have been from the manufacturer or developed specifically for the study. | |

| Written | Instructions described as ‘written’ with or without any further information were classified here. Other descriptions as per Pictorial instructions. | |

| Virtual | Instructions provided through a smartphone app or a chatbot. | |

| In-person live training | Training by a trained professional, peer, or layperson on the use of HIVST before the person used the kit. | |

| Demonstration/instructions only | Didactic training in a one-on-one or group setting. | |

| Interactive training | Training which allowed the person to ask questions or be asked to demonstrate their understanding. | |

| Other | As listed in Table 2. | |

| Live support | Support available from trained professionals, peers, and laypeople while the person was conducting the self-test. | |

| In-person support | Conducted HIVST in the presence of a person available to observe and/or assist. | |

| Phone support | Provided with phone numbers of helplines or dedicated staff who can provide advice on HIVST usage. | |

| Live chat | Trained professionals available through an online live chat. | |

| Online live video support | Live video conferencing. | |

| Social network | HIVST kits were provided by social networks such as partners, peers, and household members. These social networks may have been trained on how to use HIVST, how to provide the kit to others, or both. | |

| Other | Equipment was provided, such as timers or clocks, and earbuds to watch videos. Data vouchers were also provided allow self-testers to view instructions and videos on their mobile device. |

Indented support systems denote a sub-level.

A total of 243 (243/539, 45%) published instructions were reported, such as pictorial instructions (126/243, 52%) and videos (68/243, 28%).21 Pictorial instructions included manufacturer information for use,22 as well as those translated into different languages and versions that were rewritten using simpler language.17,23 HIVST instructions were also tailored to the local context: a Tanzanian RCT in youth of low socio-economic status developed pictorial instructions that were accessible to those without internet access and did not require an understanding of written language.19 This study also developed a video featuring a young female Tanzanian actor explaining the use of these instructions in the local language.19 Videos produced by the HIVST kit manufacturer were also sometimes provided.24 The development of instructions was also feedback-driven: a South African diagnostic evaluation study provided instructions in six official languages; the instructions were then modified based on common errors.25 Other than videos, instructions were also made available through online platforms,26 and smartphone applications (apps).27 A South African study developed the Aspect™ HIVST app, which guided users through the HIVST process, including step-by-step, pictorial guidance based on the manufacturer IFU.27

A total of 97 support systems (97/539, 18%) involved in-person live training in one-on-one or group settings before a person conducts HIVST. Most live training supports utilised a didactic approach (‘demonstration/instruction only’, 80/97, 82%), which included explanations,28 or re-reading of instructions in the local language.29 A minority of studies used an interactive training approach (11/97, 11%), which included trainers asking participants to re-perform a demonstration they had just watched,30 competency testing (quizzing of participants on the HIVST process),31 and allowing participants an opportunity to ask questions.32

There were 150 reports (150/539, 28%) of live support available while a participant performed a self-test. These supports were run by trained professionals (e.g. counsellors),15 trained peers,33 and manufacturer staff.34 Most commonly, this was in-person assistance (71/150, 47%): a Kenyan RCT offered participants the choice to use an HIVST kit in a private room with an HIV testing counsellor, who could answer questions and offer corrections on using the kit if needed.35 Remote support was also available through phone helplines (61/150, 41%),15 instant messaging (10/150, 7%),36 and online video conferencing (6/150, 4%).37 Avenues for phone support included manufacturer 24-hour hotlines,38 non-government organisations,39 government-funded helplines,40 healthcare professionals,15 and trained laypeople.41 In two Nigerian studies, due to mental health concerns relating to HIVST, phone helplines staffed by trained counsellors or peers were set up to provide support on HIVST kit use and other support services such as counselling and referrals to HIV care.41 Support through instant messaging services was available through commonplace channels such as social media (e.g. WhatsApp),42 as well as functionalities such as app-integrated chat.36 Support through online video conferencing was least common (6/150, 4%). In an RCT in the USA, transgender youth were randomised to a remote video counselling intervention: HIVST kits were delivered to self-testers’ homes and a video conference call was scheduled, where the counsellor would conduct the appropriate pre-test counselling and then guide the person through the use of the self-test.43

There were 42 reports (42/539, 8%) of support through social networks (secondary distributors), such as sexual partners and peers (e.g. other female sex workers),44,45 to act as support systems for self-tests. In a Kenyan pilot study, female sex workers and women seeking antenatal care were trained to perform a self-test, and then supported to act as test promoters to train their partners.30 They also received support for minimising inter-personal violence risk when distributing HIVST kits, helpline numbers, and details of local inter-personal violence services.30

Support systems for interpretation of results

Across 115 studies, systems supporting the interpretation of results were reported 171 times (Table 4). Similar to HIVST usage, a three-level hierarchy was used (Fig. 2). These were categorised in the same way as HIVST use, with any additional categories described in Table 5. There were 88 reports (88/171, 51%) for instructions, similar to those for test usage, using media such as pictorial (62/88, 70%),46 video (13/88, 15%),20 and smartphone/digital (5/88, 6%).47 Furthermore, there were 20 reports of in-person training in didactic (18/20, 90%),48 and interactive forms (1/20, 5%).19

| Support system | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Instructions | 88 | 51.5 | |

| Pictorial | 62 | 70.5 A | |

| Manufacturer | 32 | 53.3 B | |

| Adapted | 11 | 18.3 | |

| Custom | 4 | 6.7 | |

| Translated | 2 | 3.3 | |

| Unspecified | 13 | 21.7 | |

| Video | 13 | 14.8 | |

| Manufacturer | 5 | 38.5 | |

| Smartphone app | 2 | 15.4 | |

| Custom | 1 | 7.7 | |

| Translated | 1 | 7.7 | |

| Unspecified | 4 | 30.8 | |

| Digital | 5 | 5.7 | |

| Smartphone app | 5 | 100 | |

| Unspecified | 8 | 9.1 | |

| Assisted interpretation | 45 | 26.3 | |

| In-person support | 21 | 46.7 | |

| Trained professional | 12 | 57.1 | |

| Trained layperson | 5 | 23.8 | |

| Untrained peer | 2 | 9.5 | |

| Trained peer | 1 | 4.8 | |

| Unspecified | 1 | 4.8 | |

| Phone support | 9 | 20.0 | |

| Trained professional | 6 | 66.7 | |

| Unspecified | 3 | 33.3 | |

| Virtual | 8 | 17.8 | |

| Smartphone app scanner | 3 | 37.5 | |

| Select a corresponding image | 3 | 37.5 | |

| Remote interpretation support | 2 | 25.0 | |

| Live video | 3 | 6.7 | |

| Trained professional | 3 | 100 | |

| Instant messaging | 2 | 4.4 | |

| Trained professional | 2 | 100 | |

| Phone call | 1 | 2.2 | |

| Trained professional | 1 | 100 | |

| Online | 1 | 2.1 | |

| Trained professional | 1 | 100 | |

| In-person live training | 20 | 11.7 | |

| Demonstration/instructions only | 18 | 90.0 | |

| Trained professional | 10 | 55.6 | |

| Trained layperson | 4 | 22.2 | |

| Trained peer | 4 | 22.2 | |

| Interactive training | 1 | 5.0 | |

| Trained professional | 1 | 100 | |

| Unspecified | 1 | 5.0 | |

| Trained professional | 1 | 100 | |

| Results verification | 13 | 7.6 | |

| In-person | 6 | 46.2 | |

| Trained professional | 5 | 83.3 | |

| Trained layperson | 1 | 16.7 | |

| Online | 4 | 30.8 | |

| Trained professional | 4 | 100.0 | |

| Live video | 3 | 23.1 | |

| Trained professional | 3 | 100.0 | |

| Social network | 5 | 2.9 | |

| Partners | 4 | 80.0 | |

| Trained to interpret | 3 | 75.0 | |

| Trained to support interpretation | 1 | 25.0 | |

| Household members | 1 | 20.0 | |

| Trained to support interpretation | 1 | 100 |

Three levels are represented, with indents denoting a sub-level in the typology. Percentage frequencies are based on the count of the associated parent level. Grand total n = 171 reports of support systems.

| Support system | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| Assisted interpretation | Assistance to interpret the result obtained, either by a person or using technology. | |

| In-person support | A person was available to assist. | |

| Phone support | Provided with phone numbers of helplines or dedicated staff who can provide assistance with result interpretation. | |

| Virtual | Smartphone apps which could scan results and provide assisted or automated interpretation of results. Photos of results sent to a remote centre to be interpreted by a person. | |

| Phone call | Self-testers received an inbound phone call. | |

| Result verification | Results sent to another person (trained professional or layperson) who verifies the self-test result. | |

| Social network | HIVST kits were provided by social networks such as partners, peers, and household members. These social networks may have been trained on how to use HIVST, how to provide the kit to others, or both. | |

| Other | Equipment was provided, such as timers or clocks, and earbuds to watch videos. Data vouchers were also provided allow self-testers to view instructions and videos on their mobile device. |

Indented support systems denote a sub-level. Descriptions are only provided for those not described in Table 3.

There were 45 reports (45/171, 26%) of support systems that can actively assist self-testers in interpreting their result. These included in-person assistance (21/45, 45%),49 virtual tools (8/45, 18%),50 phone support (9/45, 20%),15 live video conferencing (3/45, 7%),51 and instant messaging (2/45, 4%).42 In the USA, the SMARTtest user-designed mobile app was trialled with cisgender men and transgender women who have sex with men. This app featured a scanning feature where the self-tester could take a photo of their test, and the app would provide a written interpretation of the result.50 Sample images for each result type were also available as a backup if the scanning feature did not work.50 The iTest app was piloted by Nigerian youth; this app prompted users to take a photo of their self-test result, which would then be placed side-by-side with an interpretation guide.52 There were 13 reports of support systems where results were verified after independent interpretation by the self-tester. These were performed in-person (6/13, 46%),53 through live video conferencing (3/13, 23%),54 or by uploading a photo to an online system (4/13, 31%).55 In a cluster-randomised trial in Lesotho, village health workers left HIVST kits for young people declining home-based HIV testing; they would later return to re-read results and provide appropriate follow-up support.53

Support systems for linkage to services after performing HIVST

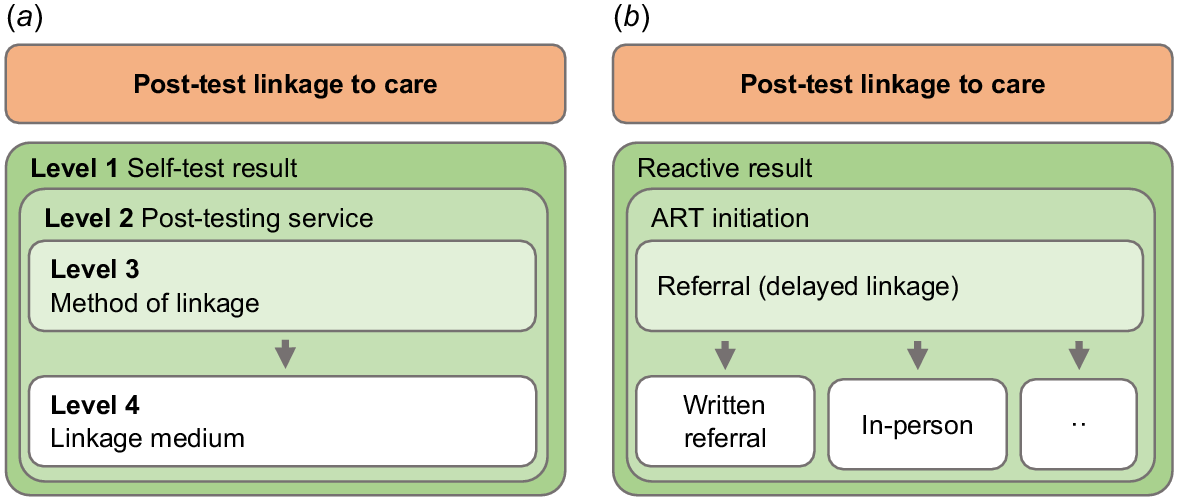

A four-level classification was developed (Fig. 3), of which three levels are in Table 6. The highest level (Level 1) defines the self-test result (reactive, non-reactive, or indeterminate) under which a support system is offered, while the remaining three sub-levels (Levels 2–4) descend in hierarchy to describe the service offered (e.g. ART initiation), the method of linkage (e.g. referral), and medium (e.g. written referral), respectively. Across 173 studies, systems supporting self-testers’ linkage to appropriate post-test services were reported 987 times (Table 6). Descriptions for the services offered and methods for linkage are in Tables 7 and 8, respectively.

Typology structure for support systems for post-test linkage to services. (a) Visual representation of the typology hierarchy. (b) Example of the typology.

| Confirmatory testing (N = 246) | ART initiation (N = 185) | Prevention services (N = 174) | Counselling (N = 170) | Further testing (N = 59) | Adjunct support services (N = 34) | Unspecified (N = 107) | Total | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | ||

| Immediate services | 43 | 17.5 A | 10 | 5.4 | 45 | 25.9 | 57 | 33.5 | 6 | 10.2 | 2 | 5.9 | 2 | 1.9 | 165 | |

| Research setting | 30 | 69.8 B | 5 | 50.0 | 16 | 35.6 | 17 | 29.8 | 4 | 66.7 | – | – | – | – | 72 | |

| Field setting | 7 | 16.3 | 1 | 10.0 | 24 | 53.3 | 25 | 43.9 | 2 | 33.3 | 1 | 50.0 | 2 | 100.0 | 62 | |

| Healthcare setting | 6 | 14.0 | 4 | 40.0 | 4 | 8.9 | 14 | 24.6 | – | – | 1 | 50.0 | – | – | 29 | |

| Unspecified | – | – | – | – | 1 | 2.2 | 1 | 1.8 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 2 | |

| Referral (delayed linkage) | 111 | 45.1 | 96 | 52.2 | 48 | 27.6 | 15 | 8.8 | 30 | 50.8 | 5 | 14.7 | 25 | 23.4 | 332 | |

| In-person | 40 | 36.0 | 40 | 41.7 | 15 | 31.3 | 5 | 33.3 | 15 | 50.0 | 1 | 20.0 | 9 | 36.0 | 126 | |

| Written referrals | 20 | 18.0 | 16 | 16.7 | 8 | 16.7 | 3 | 20.0 | 5 | 16.7 | 2 | 40.0 | 7 | 28.0 | 61 | |

| Phone call | 5 | 4.5 | 4 | 4.2 | 2 | 4.2 | – | – | 1 | 3.3 | – | – | – | – | 32 | |

| Phone number | 12 | 10.8 | 8 | 8.3 | 1 | 2.1 | – | – | 1 | 3.3 | – | – | 2 | 8.0 | 24 | |

| Live video | 6 | 5.4 | 4 | 4.2 | 9 | 18.8 | – | – | 1 | 3.3 | 1 | 20.0 | 1 | 4.0 | 22 | |

| Home re/visit | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 12 | |

| Instant messaging | 4 | 3.6 | 2 | 2.1 | 2 | 4.2 | – | – | 2 | 6.7 | – | – | 1 | 4.0 | 11 | |

| Smartphone app | – | – | 3 | 3.1 | – | – | 2 | 13.3 | 1 | 3.3 | – | – | – | – | 6 | |

| Online | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | 6.7 | – | – | – | – | 1 | 4.0 | 2 | |

| Unspecified | 15 | 13.5 | 10 | 10.4 | 5 | 10.4 | 2 | 13.3 | 2 | 6.7 | – | – | 1 | 4.0 | 35 | |

| Instructions or information | 27 | 11.0 | 23 | 12.5 | 32 | 18.4 | 13 | 7.6 | 10 | 16.9 | 8 | 23.5 | 22 | 20.6 | 135 | |

| Written | 10 | 37.0 | 9 | 39.1 | 12 | 37.5 | 7 | 53.8 | 2 | 20.0 | 4 | 50.0 | 17 | 77.3 | 61 | |

| In-person | 6 | 22.2 | 5 | 21.7 | 6 | 18.8 | 1 | 7.7 | 4 | 40.0 | 2 | 25.0 | 3 | 13.6 | 27 | |

| Smartphone app | 1 | 3.7 | 3 | 13.0 | 3 | 9.4 | 3 | 23.1 | 2 | 20.0 | – | – | 1 | 4.5 | 13 | |

| Instant messaging | 1 | 3.7 | 1 | 4.3 | 3 | 9.4 | 1 | 7.7 | 1 | 10.0 | – | – | – | – | 7 | |

| Online | 3 | 11.1 | – | – | 3 | 9.4 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 6 | |

| Video | 1 | 3.7 | 1 | 4.3 | 2 | 6.3 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | 4.5 | 5 | |

| Phone number | 1 | 3.7 | – | – | 2 | 6.3 | – | – | – | – | 1 | 12.5 | – | – | 4 | |

| Phone call | 1 | 3.7 | 1 | 4.3 | – | – | – | – | 1 | 10.0 | – | – | – | – | 3 | |

| 1 | 3.7 | 1 | 4.3 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 2 | ||

| Unspecified | 2 | 7.4 | 2 | 8.7 | 1 | 3.1 | 1 | 7.7 | – | – | 1 | 12.5 | – | – | 7 | |

| Home visit or follow-up meeting | 6 | 2.4 | 2 | 1.1 | 1 | 0.6 | 5 | 2.9 | 2 | 3.4 | – | – | 1 | 0.9 | 20 | |

| Trained professional | 7 | 77.8 | 2 | 100.0 | – | – | 1 | 20.0 | 2 | 100.0 | – | – | – | – | 12 | |

| Trained layperson | 1 | 11.1 | – | – | 1 | 100.0 | 4 | 80.0 | – | – | – | – | 1 | 100.0 | 7 | |

| Trained peer | 1 | 11.1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | |

| Online | 6 | 2.4 | 2 | 1.1 | 17 | 9.8 | 7 | 4.1 | 1 | 1.7 | 2 | 5.9 | – | – | 35 | |

| Live video | 1 | 16.7 | – | – | 12 | 70.6 | 2 | 28.6 | 1 | 100.0 | 1 | 50.0 | – | – | 17 | |

| Smartphone app | 1 | 16.7 | 1 | 50.0 | 2 | 11.8 | 4 | 57.1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 8 | |

| Website | 4 | 66.7 | – | – | 3 | 17.6 | – | – | – | – | 1 | 50.0 | – | – | 8 | |

| Unspecified | – | – | 1 | 50.0 | – | – | 1 | 14.3 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 2 | |

| Phone support | 8 | 3.3 | 8 | 4.3 | 3 | 1.7 | 31 | 18.2 | 2 | 3.4 | 15 | 44.1 | 35 | 32.7 | 102 | |

| Trained professional | 4 | 50.0 | 4 | 50.0 | 2 | 66.7 | 21 | 67.7 | – | – | 13 | 86.7 | 23 | 65.7 | 67 | |

| Trained layperson | 2 | 25.0 | 2 | 25.0 | 1 | 33.3 | 1 | 3.2 | 1 | 50.0 | – | – | – | – | 7 | |

| Trained peer | 1 | 12.5 | – | – | – | – | 1 | 3.2 | – | – | – | – | 1 | 2.9 | 3 | |

| Unspecified | 1 | 12.5 | 2 | 25.0 | – | – | 8 | 25.8 | 1 | 50.0 | 2 | 13.3 | 11 | 31.4 | 25 | |

| Phone call | 8 | 3.3 | 8 | 4.3 | 5 | 2.9 | 18 | 10.6 | 3 | 5.1 | – | – | 6 | 5.6 | 50 | |

| Trained professional | 7 | 87.5 | 7 | 87.5 | 5 | 100.0 | 15 | 83.3 | 2 | 66.7 | – | – | 5 | 83.3 | 43 | |

| Trained layperson | 1 | 12.5 | 1 | 12.5 | – | – | 1 | 5.6 | 1 | 33.3 | – | – | – | – | 4 | |

| Trained peer | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | 5.6 | – | – | – | – | 1 | 16.7 | 2 | |

| Unspecified | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | 5.6 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | |

| Instant messaging | 2 | 0.8 | 4 | 2.2 | – | – | 8 | 4.7 | – | – | 1 | 2.9 | 6 | 5.6 | 21 | |

| Trained professional | – | – | 3 | 75.0 | – | – | 6 | 75.0 | – | – | 1 | 100.0 | 5 | 83.3 | 15 | |

| Trained peer | 1 | 50.0 | – | – | – | – | 1 | 12.5 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 2 | |

| Automated | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | 12.5 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | |

| Unspecified | 1 | 50.0 | 1 | 25.0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | 16.7 | 3 | |

| Offer to accompany | 10 | 4.1 | 7 | 3.8 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 17 | |

| Trained professional | 5 | 50.0 | 3 | 42.9 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 8 | |

| Trained peer | 4 | 40.0 | 3 | 42.9 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 7 | |

| Trained layperson | 1 | 10.0 | 1 | 14.3 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 2 | |

| Notification beacon | – | – | – | – | 1 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.6 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 2 | |

| Phone call | – | – | – | – | 1 | 100.0 | 1 | 100.0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 2 | |

| Reimbursement or incentive | 10 | 4.1 | 7 | 3.8 | 6 | 3.4 | 3 | 1.8 | 1 | 1.7 | – | – | – | – | 32 | |

| Transport | 5 | 50.0 | 4 | 57.1 | 3 | 50.0 | 1 | 33.3 | 1 | 100.0 | – | – | – | – | 14 | |

| Money | 3 | 30.0 | 1 | 14.3 | 1 | 16.7 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 5 | |

| Deposit refund | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | 33.3 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 5 | |

| Lottery ticket | 1 | 10.0 | 1 | 14.3 | 1 | 16.7 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 3 | |

| Subsidised | 1 | 10.0 | 1 | 14.3 | 1 | 16.7 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 3 | |

| Kit cost reimbursed | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | 33.3 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | |

| Social network | 8 | 3.3 | 3 | 1.6 | 6 | 3.4 | 2 | 1.2 | – | – | – | – | 3 | 2.8 | 22 | |

| Partners | 7 | 87.5 | 2 | 66.7 | 6 | 100.0 | 2 | 100.0 | – | – | – | – | 3 | 100.0 | 20 | |

| Peers | 1 | 12.5 | 1 | 33.3 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 2 | |

| Other | – | – | – | – | 2 | 1.1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 2 | |

| Sent by mail | – | – | – | – | 2 | 100.0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 2 | |

| Unspecified | 7 | 2.8 | 14 | 7.6 | 8 | 4.6 | 7 | 4.1 | 4 | 6.8 | 1 | 2.9 | 7 | 6.5 | 50 | |

Three levels are represented: columns represent the service offered, while rows represent the support system type (with indents denoting a sub-level in the typology). Services and support systems not included in the table: Other (N = 7, reimbursement, n = 5 (71%); equipment provided, n = 2 (29%)); and Follow-up (N = 6, referral/counselling, n = 2 (33%), phone call, n = 2 (33%), unspecified, n = 2 (33%)). Grand total n = 987 reports of support systems.

| Service | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| Confirmatory testing | Clinic-based HIV testing, including adjuncts such as disease staging, CD4 counts, and viral load | |

| ART initiation | Initiation and retention of HIV treatment | |

| Prevention services | PrEP and PEP services, voluntary male medical circumcision, safer sex supplies (e.g. condoms), HIV prevention counselling, drug and alcohol counselling | |

| Counselling | Post-test counselling, results counselling | |

| Further testing | HIV clinic-based testing, STI testing (and treatment), further HIVST testing | |

| Adjunct support services | Psychosocial supports e.g. mental health, violence support, family planning, people living with HIV groups |

| Support system | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| Immediate linkage | Service was provided at the same time that the HIVST result was obtained | |

| Referral (delayed linkage) | Referral or counselling to be linked to a particular service | |

| Instructions or information | Instructions on next steps after HIVST Information on different post-testing services | |

| Home visit or follow-up meeting | A trained person (1) visited or returned to the self-testers home to offer or provide the service, or (2) scheduled a follow-up meeting at an agreed location | |

| Online | Online-based support services or systems | |

| Phone support | Provided with phone numbers of helplines or dedicated staff who can provide advice on HIVST usage | |

| Phone call | Self-testers received an inbound phone call | |

| Instant messaging | Instant messaging services including SMS, social media, and WhatsApp | |

| Offer to accompany | A trained person offering to accompany the self-tester to attend a service | |

| Notification beacon | Bluetooth beacons that would notify counsellors when a HIVST kit has been opened 56 |

The most common services offered were confirmatory testing (246/987, 25%), ART initiation (184/987, 19%), and prevention services such as PrEP (174/987, 18%). Further testing options (59/987, 6%) included regular facility-based HIV re-testing,47 the provision of more HIVST kits,57 and testing for other STIs;58 while adjunct support systems (34/987, 3%) included psychological support,26 peer support,46 violence support,18 and legal advice.18 The South Africa National AIDS Helpline provides an integrative multi-lingual service that allows self-testers to receive post-test counselling and referrals to confirmatory testing and care.18 The counsellors are also trained to provide basic emotional support, and can also refer to organisations and hotlines relating to violence, family matters, legal advice, and suicide.18

Many services were offered specifically for those with reactive (438/987, 44%), non-reactive (128/987, 13%), or indeterminate results (20/987, 2%). For support systems relating to reactive results (N = 438), the most common services linked were ART initiation (183/438, 42%) and confirmatory testing (135/438, 31%); while for non-reactive results (N = 128), the most common services were prevention services (e.g. PrEP, risk reduction counselling; 74/128, 58%), and further testing (25/128, 20%).

The most common support systems offered were referrals (332/987, 34%), immediate services (165/987, 17%), and phone helplines (102/987, 10%). Referrals (N = 332) were available in forms such as in-person interactions (126/332, 38%),59 written referrals (61/332, 18%),16 and inbound phone calls (32/332, 10%).60 In a Canadian cohort study, self-testers would receive a follow-up call after reporting their self-test result online; those with reactive results received support and referral to seek confirmatory test, while those with non-reactive results received counselling on window periods, re-testing, and PrEP.60 Of the services (e.g. confirmatory testing, ART) offered immediately (N = 165), these were mostly studies being conducted in research or simulated settings (72/165, 44%).25 However, many HIVST kits were also distributed in the field and mobile outreach sites (62/165, 38%),61 as well as healthcare settings (e.g. clinics; 29/165, 18%),62 where users were given an opportunity to perform the self-test in a private location on-site.

Other support systems include home visits or follow-up meetings (20/987, 2%),63 offers to accompany people to facility services (17/987, 2%),55 and notification beacons (n = 2/987, <1%).64 In a Zambian cluster-randomised trial of door-to-door HIVST distribution, community providers returned for a follow-up visit.63 Trained peers have also been used in a Chinese cross-sectional study, where peer navigators would accompany those with a reactive result to confirmatory testing, treatment, and care services.55 To further extend the reach of support services, an RCT in the USA used the eTEST kit, an HIVST kit with an in-built Bluetooth beacon. This beacon would send a signal to counsellors (via a paired app pre-downloaded on the user’s phone) once the kit had been opened, allowing counsellors to follow up with a phone call within 24 h to check whether the kit had been used and to offer appropriate counselling and referrals.64

Discussion

We developed a typology to categorise the range of support systems for the HIV self-testing process: from using the self-test kit, to interpreting the result, to linking to relevant post-test services. To our knowledge, this is the first attempt to define and classify such support systems across a breadth of modalities. Our typology aligns approximately with the brief HIVST support tools classification described by Jamil and colleagues relating to instructions, demonstration, and supervision.12 Previous systematic reviews have described and summarised HIVST result verification to support linkage to care and digital support systems.10,11 Our typology reveals a wide spectrum of available support systems, which could be delivered together to address different issues across populations. In addition to established systems that utilise print and in-person services, we found technology integration could be potentially promising in improving accessibility and accuracy. The vast majority of support systems were implemented or studied after the WHO recommendations in 2016, which drove significant growth in studies on HIV self-testing, as well as in development of a wider range of support systems. Prior to this, most support systems reported were more rudimentary in nature, such as pictorial instructions and counselling.

The typology proposed here provides a framework for future analysis and comparison of the acceptability, uptake, and effectiveness of different support systems. While Figueroa and colleagues found that HIVST could be accurately performed by laypeople, errors were still reported,4 suggesting that there is an unmet need in assisting people to perform HIVST. Our typology provides a high level summary of support systems which can be considered and compared to allow users in a given socio-cultural and economic context to use HIVST kits and interpret their result most effectively. Similarly, it is important to examine how support systems can help link HIVST users to sexual health services, such as HIV treatment. Support systems in our typology can be compared in how they help to achieve outcome measures such as linkage to HIV care, commencement of treatment, and viral suppression. Implementation measures such as cost effectiveness of support systems can also be examined. Furthermore, the target population of a HIVST intervention may also be an important consideration. Only 37.5% of our included studies focused on MSM, despite their increasing importance as a key population for new HIV infections in the past decade.65 However, we also note that the vast majority of our included studies originated from sub-Saharan Africa, where HIV transmission is most predominant in women, especially AGYW.66 Finally, for healthcare and public health practitioners, our typology can also act as a catalogue of possible support systems that can be implemented, however feasibility must be considered in each context.

We found diverse support approaches, including print, in-person, and virtual. These were used both as singular approaches and in combination to improve the understanding of instructions and information by self-testers.19 While many HIVST kit manufacturers already include videos and toll-free hotlines as part of their kits,34,67 in-person and live support systems may help new self-test users understand instructions and perform self-tests. However, the financial cost of training and sustaining personnel for these support systems can be significant when scaling up HIVST programs.68 Offering multiple options allows individuals to select instructions according to personal preferences and circumstances.69 The breadth of the options provided should consider accessibility and understandability. For example, health literacy and educational level have been highlighted as barriers for some people to understand self-testing instructions.22,70 Also, virtual options may not be suitable for those without reliable internet access or limited digital literacy.71 Similarly, it is important to consider how linguistic and cultural contexts can influence a user’s engagement with instructions. Instructions should be available in local languages and be developed and reviewed by communities and end-users.23 Furthermore, the contextual meaning of symbols and diagrams can be confusing for some in different cultural contexts. For example, Simwinga and colleagues found that some individuals in Malawi and Zambia did not easily associate a knife and fork symbol with eating.22 Understandability of instructions has also been reported as an issue with manufacturer instructions for COVID-19 self-tests.72 Finally, developing culturally appropriate support systems can help emphasise linkage to care messaging. Using local influencers in instructional videos and associating linkage to care with community roles may be helpful in this respect.19 Having a range of support systems available across different modalities can help HIVST users navigate the self-testing process. There must also be consideration of linguistic and cultural appropriateness, with community input.

Technology can bridge the gaps in accessibility and usability at all stages of HIVST. Using video instructions alongside pictorial instructions may improve some users’ ability to accurately perform the test and interpret the results compared to pictorial instructions alone.21 Mobile applications with scanning software that can accurately interpret the test result, such that it reads test results and converts to a textual output for the tester,50 may support users in reducing errors in result interpretation. Additional linkage to care pathways can be provided through which the individual can forward the scanned results to healthcare providers for a follow-up of reactive results for confirmation testing, ART, and psychosocial support and counselling.73 Virtual counselling, such as online video-based or text message-based chat conducted by professional counsellors,54 or peers,33 can be used to increase HIVST support by providing testing guidance and support during pre-testing and testing, and by providing referral and linkage to care support in post-testing. The use of machine learning-based chatbots in healthcare, which has been demonstrated to provide medical support empathically and accurately, may also be a future option to explore.74 However, while technology-based support systems are an area for innovation in the development of effective HIVST programs, they come with their own challenges. Healthcare providers must be aware of and address data security concerns relating to the confidentiality of sensitive data, particularly when sharing reactive test results.73 Implementation cost is also important and should be considered in the context of local resourcing and program needs.75 Overall, the application of technology in HIVST programs can be beneficial, however, it may not be suitable in all situations.

In this global review, we searched and examined articles without limitation on population, study type or geographical region. However, we have identified some limitations of our work. First, some articles were unclear on the reporting of their support systems, such as the exact nature of a support system or distinguishing between HIVST use and results interpretation. Where needed, we contacted corresponding authors for clarification (nine emails with six responses, 66% response rate). To facilitate future research on support systems, we recommend that support systems be reported in sufficient detail to allow broad replicability. Second, as there is no previously established terminology or typology relating to HIVST support systems, our search may have missed some relevant papers; however, due to the breadth of the search, we believe that we were able to capture the different types of support systems used. Finally, our review did not examine the acceptability, uptake, or effectiveness of support systems, which we recommend for future research. Our typology may act as a framework for future research into these measures. Gathering evidence for effective support systems can facilitate the development, implementation, and scale-up of global HIVST programs to reach the UNAIDS 2025 target and also provide important knowledge for other self-testing approaches across diseases.

Conclusion

Our typologies can facilitate future analysis and development of HIVST support systems. Systems that support HIV self-testing globally utilise diverse methods, including static media, digital tools, and in-person interactions. In-person and print-based methods are more prevalent, but newer virtual solutions can address accessibility and accuracy challenges. Creating synergies and ensuring linguistic and cultural appropriateness of support systems can improve the effectiveness of HIV self-testing, thereby contributing to ending HIV as a public health threat (UN Sustainable Development Goal, Target 3.3).76 Finally, while our work was specific for HIVST, our typology and analysis can be generalisable as a framework for developing self-testing programs across a range of infectious diseases (e.g. COVID-19, viral hepatitis, syphilis).

Data availability

The data that support this study will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of interest

CCJ, MSJ and RCB are current World Health Organization staff members. The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this publication, and they do not necessarily represent the views, decisions, or policies of the institutions with which they are affiliated. EPFC has received research funding to their institution from Merck and Seqirus, outside of the submitted work. MSJ has received research funding to their institution from BMGF and received funding to WHO from USAID, outside of the submitted work. JJO, LZ, and EPFC are Editors of Sexual Health. To mitigate this potential conflict of interest they had no editor-level access to this manuscript during peer review.

Declaration of funding

JJO and EPFC are each supported by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Emerging Leadership Investigator Grant [GNT1193955 for JJO; GNT1172873 for EPFC]. CKF is supported by an Australian NHMRC Leadership Investigator Grant [GNT1172900]. CCJ is supported by funding under the Unitaid-WHO HIV and Co-Infections/Co-Morbidities Enabler Grant (HIV&COIMS). The funders had no role in the analysis or interpretation of the research or the decision to submit it for publication.

Author contributions

JJO conceived the idea. AT, NT and JT did the screening, data extraction and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to interpreting the results and subsequent edits of the manuscript and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

References

3 Figueroa C, Johnson C, Verster A, Baggaley R. Attitudes and acceptability on HIV self-testing among key populations: a literature review. AIDS Behav 2015; 19(11): 1949-65.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

4 Figueroa C, Johnson C, Ford N, Sands A, Dalal S, Meurant R, et al. Reliability of HIV rapid diagnostic tests for self-testing compared with testing by health-care workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet HIV 2018; 5(6): e277-e90.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

6 Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Laws and policies analytics. Geneva: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Available at https://lawsandpolicies.unaids.org/. [cited 21 August 2023]

7 Stevens DR, Vrana CJ, Dlin RE, Korte JE. A global review of HIV self-testing: themes and implications. AIDS Behav 2018; 22(2): 497-512.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

9 Gohil J, Baja ES, Sy TR, Guevara EG, Hemingway C, Medina PMB, et al. Is the Philippines ready for HIV self-testing? BMC Public Health 2020; 20(1): 34.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

10 Tahlil KM, Ong JJ, Rosenberg NE, Tang W, Conserve DF, Nkengasong S, et al. Verification of HIV self-testing use and results: a global systematic review. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2020; 34(4): 147-56.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

11 McGuire M, de Waal A, Karellis A, Janssen R, Engel N, Sampath R, et al. HIV self-testing with digital supports as the new paradigm: a systematic review of global evidence (2010–2021). eClinicalMedicine 2021; 39: 101059.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

12 Jamil MS, Eshun-Wilson I, Witzel TC, Siegfried N, Figueroa C, Chitembo L, et al. Examining the effects of HIV self-testing compared to standard HIV testing services in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. eClinicalMedicine 2021; 38: 100991.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

13 Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005; 8(1): 19-32.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

14 PRISMA. PRISMA for scoping reviews. Available at https://www.prisma-statement.org/scoping [22 January 2022]

15 Horvath KJ, Bwanika JM, Lammert S, Banonya J, Atuhaire J, Banturaki G, et al. HiSTEP: a single-arm pilot study of a technology-assisted HIV self-testing intervention in Kampala, Uganda. AIDS Behav 2022; 26(3): 935-46.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

16 Choko AT, Nanfuka M, Birungi J, Taasi G, Kisembo P, Helleringer S. A pilot trial of the peer-based distribution of HIV self-test kits among fishermen in Bulisa, Uganda. PLoS ONE 2018; 13(11): e0208191.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

17 Tonen-Wolyec S, Batina-Agasa S, Muwonga J, Mboumba Bouassa R-S, Kayembe Tshilumba C, Bélec L. Acceptability, feasibility, and individual preferences of blood-based HIV self-testing in a population-based sample of adolescents in Kisangani, Democratic Republic of the Congo. PLoS ONE 2019; 14(7): e0218795.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

18 Arullapan N, Chersich MF, Mashabane N, Richter M, Geffen N, Veary J, et al. Quality of counselling and support provided by the South African national AIDS helpline: content analysis of mystery client interviews. S Afr Med J 2018; 108(7): 596-602.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

19 Catania JA, Huun C, Dolcini MM, Urban AJ, Fleury N, Ndyetabula C, et al. Overcoming cultural barriers to implementing oral HIV self-testing with high fidelity among Tanzanian youth. Transl Behav Med 2021; 11(1): 87-95.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

20 Pasipamire L, Nesbitt RC, Dube L, Mabena E, Nzima M, Dlamini M, et al. Implementation of community and facility-based HIV self-testing under routine conditions in southern Eswatini. Trop Med Int Health 2020; 25(6): 723-31.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

21 Tonen-Wolyec S, Djang’eing’a RM, Batina-Agasa S, Kayembe Tshilumba C, Muwonga Masidi J, Hayette M-P, et al. Self-testing for HIV, HBV, and HCV using finger-stick whole-blood multiplex immunochromatographic rapid test: a pilot feasibility study in sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS ONE 2021; 16(4): e0249701.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

22 Simwinga M, Kumwenda MK, Dacombe RJ, Kayira L, Muzumara A, Johnson CC, et al. Ability to understand and correctly follow HIV self-test kit instructions for use: applying the cognitive interview technique in Malawi and Zambia. J Int AIDS Soc 2019; 22(S1): e25253.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

23 Grésenguet G, Longo JdD, Tonen-Wolyec S, Bouassa R-SM, Belec L. Acceptability and usability evaluation of finger-stick whole blood HIV self-test as an HIV screening tool adapted to the general public in the central African Republic. Open AIDS J 2017; 11: 101-18.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

24 Chen Y-H, Gilmore HJ, Maleke K, Lane T, Zuma N, Radebe O, et al. Increases in HIV status disclosure and sexual communication between South African men who have sex with men and their partners following use of HIV self-testing kits. AIDS Care 2021; 33(10): 1262-9.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

25 Devillé W, Tempelman H. Feasibility and robustness of an oral HIV self-test in a rural community in South-Africa: an observational diagnostic study. PLoS ONE 2019; 14(4): e0215353.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

26 De Boni RB, Veloso VG, Fernandes NM, Lessa F, Correa RG, Lima RS, et al. An internet-based HIV self-testing program to increase HIV testing uptake among men who have sex with men in Brazil: descriptive cross-sectional analysis. J Med Internet Res 2019; 21(8): e14145.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

27 Gous N, Fischer AE, Rhagnath N, Phatsoane M, Majam M, Lalla-Edward ST. Evaluation of a mobile application to support HIV self-testing in Johannesburg, South Africa. South Afr J HIV Med 2020; 21(1): a1088.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

28 Hacking D, Cassidy T, Ellman T, Steele SJ, Moore HA, Bermudez-Aza E, et al. HIV self-testing among previously diagnosed HIV-positive people in Khayelitsha, South Africa: no evidence of harm but may facilitate re-engagement in ART care. AIDS Behav 2022; 26: 2891-6.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

29 Asiimwe S, Oloya J, Song X, Whalen CC. Accuracy of un-supervised versus provider-supervised self-administered HIV testing in Uganda: a randomized implementation trial. AIDS Behav 2014; 18(12): 2477-84.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

30 Agot K, Masters SH, Wango G-N, Thirumurthy H. Can women safely distribute HIV oral self-test kits to their sexual partners? Results from a pilot study in Kenya. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2018; 78(5): e39-e41.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

31 Kumwenda MK, Corbett EL, Choko AT, Chikovore J, Kaswaswa K, Mwapasa M, et al. Post-test adverse psychological effects and coping mechanisms amongst HIV self-tested individuals living in couples in urban Blantyre, Malawi. PLoS ONE 2019; 14(6): e0217534.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

32 Pintye J, Drake AL, Begnel E, Kinuthia J, Abuna F, Lagat H, et al. Acceptability and outcomes of distributing HIV self-tests for male partner testing in Kenyan maternal and child health and family planning clinics. AIDS 2019; 33(8): 1369-78.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

33 Maksut JL, Eaton LA, Siembida EJ, Driffin DD, Baldwin R. A test of concept study of at-home, self-administered HIV testing with web-based peer counseling via video chat for men who have sex with men. JMIR Public Health Surveill 2016; 2(2): e170.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

34 Wray TB, Chan PA, Simpanen E, Operario D. A pilot, randomized controlled trial of HIV self-testing and real-time post-test counseling/referral on screening and preventative care among men who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2018; 32(9): 360-7.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

35 Kelvin EA, George G, Mwai E, Kinyanjui S, Romo ML, Odhiambo JO, et al. A randomized controlled trial to increase HIV testing demand among female sex workers in kenya through announcing the availability of HIV self-testing via text message. AIDS Behav 2019; 23(1): 116-25.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

36 Fischer AE, Phatsoane M, Majam M, Shankland L, Abrahams M, Rhagnath N, et al. Uptake of the Ithaka mobile application in Johannesburg, South Africa, for human immunodeficiency virus self-testing result reporting. South Afr J HIV Med 2021; 22(1): a1197.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

37 Anand T, Nitpolprasert C, Kerr S, Apornpong T, Ananworanich J, Phanuphak P, et al. Factors influencing and associated with the decision to join in Thailand’s first online supervised HIV self-testing and counselling initiative. J Int AIDS Soc 2016; 19(Supplement 7): 21487.

| Google Scholar |

38 Edelstein ZR, Wahnich A, Purpura LJ, Salcuni PM, Tsoi BW, Kobrak PH, et al. Five waves of an online HIV self-test giveaway in New York City, 2015 to 2018. Sex Transm Dis 2020; 47(5S): S41-S7.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

39 Ankiersztejn-Bartczak M, Kowalska J. Self-testing for HIV among partners of newly diagnosed HIV persons - the pilot program of Test and Keep in Care (TAK) project. Prz Epidemiol 2021; 75(3): 347-54.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

40 Bulterys MA, Mujugira A, Nakyanzi A, Nampala M, Taasi G, Celum C, et al. Costs of providing HIV self-test kits to pregnant women living with HIV for secondary distribution to male partners in Uganda. Diagnostics 2020; 10(5): 318.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

41 Sekoni A, Tun W, Dirisu O, Ladi-Akinyemi T, Shoyemi E, Adebajo S, et al. Operationalizing the distribution of oral HIV self-testing kits to men who have sex with men (MSM) in a highly homophobic environment: the Nigerian experience. BMC Public Health 2022; 22(1): 33.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

42 Zhang C, Koniak-Griffin D, Qian H-Z, Goldsamt LA, Wang H, Brecht M-L, et al. Impact of providing free HIV self-testing kits on frequency of testing among men who have sex with men and their sexual partners in China: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med 2020; 17(10): e1003365.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

43 Stephenson R, Todd K, Kahle E, Sullivan SP, Miller-Perusse M, Sharma A, et al. Project moxie: results of a feasibility study of a telehealth intervention to increase HIV testing among binary and nonbinary transgender youth. AIDS Behav 2020; 24(5): 1517-30.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

44 Choko AT, Fielding K, Johnson CC, Kumwenda MK, Chilongosi R, Baggaley RC, et al. Partner-delivered HIV self-test kits with and without financial incentives in antenatal care and index patients with HIV in Malawi: a three-arm, cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet Global Health 2021; 9(7): e977-e88.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

45 Kumwenda MK, Mavhu W, Lora WS, Chilongosi R, Sikwese S, Taegtmeyer M, et al. Feasibility and acceptability of a peer-led HIV self-testing model among female sex workers in Malawi: a qualitative study. BMJ Open 2021; 11(12): e049248.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

46 Bell SFE, Lemoire J, Debattista J, Redmond AM, Driver G, Durkin I, et al. Online HIV self-testing (HIVST) dissemination by an Australian community peer HIV organisation: a scalable way to increase access to testing, particularly for suboptimal testers. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18(21): 11252.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

47 Pant Pai N, Smallwood M, Desjardins L, Goyette A, Birkas KG, Vassal A-F, et al. An unsupervised smart app-optimized HIV self-testing program in Montreal, Canada: cross-sectional study. J Med Internet Res 2018; 20(11): e10258.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

48 Koris AL, Stewart KA, Ritchwood TD, Mususa D, Ncube G, Ferrand RA, et al. Youth-friendly HIV self-testing: acceptability of campus-based oral HIV self-testing among young adult students in Zimbabwe. PLoS ONE 2021; 16(6): e0253745.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

49 Indravudh PP, Fielding K, Kumwenda MK, Nzawa R, Chilongosi R, Desmond N, et al. Effect of community-led delivery of HIV self-testing on HIV testing and antiretroviral therapy initiation in Malawi: a cluster-randomised trial. PLoS Med 2021; 18(5): e1003608.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

50 Balan IC, Rios JL, Lentz C, Arumugam S, Dolezal C, Kutner B, et al. Acceptability and use of a dual HIV/syphilis rapid test and accompanying smartphone app to facilitate self- and partner-testing among cisgender men and transgender women who have sex with men. AIDS Behav 2022; 26(1): 35-46.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

51 Stephenson R, Metheny N, Sharma A, Sullivan S, Riley E. Providing home-based HIV testing and counseling for transgender youth (Project Moxie): protocol for a pilot randomized controlled trial. JMIR Res Protoc 2017; 6(11): e237.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

52 Oladele D, Iwelunmor J, Gbajabiamila T, Obiezu-Umeh C, Okwuzu JO, Nwaozuru U, et al. The 4 Youth By Youth mHealth photo verification App for HIV Self-testing in Nigeria: qualitative analysis of user experiences. JMIR Form Res 2021; 5(11): e25824.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

53 Amstutz A, Kopo M, Lejone TI, Khesa L, Kao M, Muhairwe J, et al. “If it is left, it becomes easy for me to get tested”: use of oral self-tests and community health workers to maximize the potential of home-based HIV testing among adolescents in Lesotho. J Int AIDS Soc 2020; 23(S5): e25563.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

54 Stephenson R, Sullivan SP, Mitchell JW, Johnson BA, Sullvian PS. Efficacy of a telehealth delivered couples’ HIV counseling and testing (CHTC) intervention to improve formation and adherence to safer sexual agreements among male couples in the US: results from a randomized control trial. AIDS Behav 2022; 26: 2813-24.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

55 Jin X, Xu J, Smith MK, Xiao D, Rapheal ER, Xiu X, et al. An internet-based self-testing model (Easy Test): cross-sectional survey targeting men who have sex with men who never tested for HIV in 14 provinces of China. J Med Internet Res 2019; 21(5): e11854.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

56 Wray T, Chan PA, Simpanen E, Operario D. eTEST: developing a smart home HIV testing kit that enables active, real-time follow-up and referral after testing. JMIR mHealth Uhealth 2017; 5(5): e62.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

57 Shava E, Bogart LM, Manyake K, Mdluli C, Maribe K, Monnapula N, et al. Feasibility of oral HIV self-testing in female sex workers in Gaborone, Botswana. PLoS ONE 2021; 16(11): e0259508.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

58 Phanuphak N, Jantarapakde J, Himmad L, Sungsing T, Meksena R, Phomthong S, et al. Linkages to HIV confirmatory testing and antiretroviral therapy after online, supervised, HIV self-testing among Thai men who have sex with men and transgender women. J Int AIDS Soc 2020; 23(1): e25448.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

59 Nguyen TTV, Phan HTT, Kato M, Nguyen QT, Le Ai KA, Vo SH, et al. Community-led HIV testing services including HIV self-testing and assisted partner notification services in Vietnam: lessons from a pilot study in a concentrated epidemic setting. J Int AIDS Soc 2019; 22(S3): e25301.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

60 O’Byrne P, Musten A, Orser L, Inamdar G, Grayson M-O, Jones C, et al. At-home HIV self-testing during COVID: implementing the GetaKit project in Ottawa. Can J Public Health 2021; 112(4): 587-94.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

61 d’Elbee M, Makhetha MC, Jubilee M, Taole M, Nkomo C, Machinda A, et al. Using HIV self-testing to increase the affordability of community-based HIV testing services. AIDS 2020; 34(14): 2115-23.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

62 Dovel K, Shaba F, Offorjebe OA, Balakasi K, Nyirenda M, Phiri K, et al. Effect of facility-based HIV self-testing on uptake of testing among outpatients in Malawi: a cluster-randomised trial. Lancet Global Health 2020; 8(2): e276-e87.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

63 Mulubwa C, Hensen B, Phiri MM, Shanaube K, Schaap AJ, Floyd S, et al. Community based distribution of oral HIV self-testing kits in Zambia: a cluster-randomised trial nested in four HPTN 071 (PopART) intervention communities. Lancet HIV 2019; 6(2): e81-e92.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

64 Wray TB, Chan PA, Simpanen EM. Longitudinal effects of home-based HIV self-testing on well-being and health empowerment among men who have sex with men (MSM) in the United States. AIDS Care 2020; 32(2): 148-54.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

66 Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Women and girls carry the heaviest HIV burden in sub-Saharan Africa. Geneva: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; 2022. Available at https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/presscentre/featurestories/2022/march/20220307_women-girls-carry-heaviest-hiv-burden-sub-saharan-africa

67 OraSure Technologies. OraQuick HIV self-test. Available at https://www.orasure.com/products-infectious/OraQuick-Self-Test.html.

68 d’Elbee M, Traore MM, Badiane K, Vautier A, Simo Fotso A, Kabemba OK, et al. Costs and scale-up costs of integrating HIV self-testing into civil society organisation-led programmes for key populations in Côte d’Ivoire, Senegal, and Mali. Front Public Health 2021; 9: 653612.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

69 Matovu JKB, Bogart LM, Nakabugo J, Kagaayi J, Serwadda D, Wanyenze RK, et al. Feasibility and acceptability of a pilot, peer-led HIV self-testing intervention in a hyperendemic fishing community in rural Uganda. PLoS ONE 2020; 15(8): e0236141.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

70 Tonen-Wolyec S, Batina-Agasa S, Muwonga J, Fwamba N’kulu F, Mboumba Bouassa R-S, Belec L. Evaluation of the practicability and virological performance of finger-stick whole-blood HIV self-testing in French-speaking sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS ONE 2018; 13(1): e0189475.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

71 Zhou Y, Lu Y, Ni Y, Wu D, He X, Ong JJ, et al. Monetary incentives and peer referral in promoting secondary distribution of HIV self-testing among men who have sex with men in China: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med 2022; 19(2): e1003928.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

72 Jing M, Bond R, Robertson LJ, Moore J, Kowalczyk A, Price R, et al. User experience of home-based AbC-19 SARS-CoV-2 antibody rapid lateral flow immunoassay test. Sci Rep 2022; 12(1): 1173.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

73 Kutner BA, Pho AT, López-Rios J, Lentz C, Dolezal C, Bálan IC. Attitudes and perceptions about disclosing HIV and syphilis results using Smarttest, a smartphone app dedicated to self- and partner testing. AIDS Educ Prev 2021; 33(3): 234-48.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

74 Ayers JW, Poliak A, Dredze M, Leas E, Zhu Z, Kelley J, et al. Comparing physician and artificial intelligence chatbot responses to patient questions posted to a public social media forum. JAMA Int Med 2023; 183: 589-96.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

76 Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Goal 3| Department of Economic and Social Affairs. New York: United Nations; 2023. Available at https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal3. [cited 31 July 2023]