U=U: the life force given by the mother’s breast

Rhonda Marama Tamati A *

A *

A Ngaatiawa ki Kapiti taku Tai, Independent Consultant.

Sexual Health - https://doi.org/10.1071/SH23061

Submitted: 31 March 2023 Accepted: 5 May 2023 Published online: 3 July 2023

© 2023 The Author(s) (or their employer(s)). Published by CSIRO Publishing. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND)

Abstract

The background of this paper starts with the history and significance of the author’s relationship to the Campaign, U=U; Undetectable equals Untransmissable as an Indigenous woman and well-known advocate living with HIV. The methods used in this paper explored an adaptation of a thriving indigenous Health Framework implemented in New Zealand for over 40 years. We anticipate the methods used in this paper along with the U=U Campaign will make the U=U relevant to other Indigenous Peoples. The common threads of the cultures are our creation stories and our rendition of the Health Circle or the Four Pillars. We interviewed and surveyed key community members, family, people living with HIV, and social workers that work in those communities over a period of 6 months; 36 people participated. We shared personal stories anecdotally of her experiences. The results were a health model comparison of U=U from a Māori worldview. Each aspect of the Four Pillars or cornerstones of the model is explained from a personal experience perspective, which is inclusive and reflects a process familiar to Indigenous Peoples and worldviews. We are using stories to relay that information from that particular worldview. In conclusion, after much deliberation, discussions with key people, and personal experiences, we can tie the concept of U=U to an intrinsic framework that other Indigenous Peoples and communities can easily interpret.

Keywords: awareness, HIV/AIDS, HIV prevention, human rights, Indigenous Peoples, living with HIV, Red Ribbon Awardee, reproductive rights.

Introduction

Kā tuku ngā mihi mīharo ki ā koutou kātoa (I acknowledge the wonder of you all)

My name is Mārama, and I am a descendant of the Ngaatiawa1 ki Kapiti people – Indigenous of Āotearoa, New Zealand. A rough translation of my people’s name is the People of the River. Translated, my name Mārama2 is the moon, month, white light or lamp and enlightenment. I am a child of 183 years of colonisation of the Māori people and subsequent activism in Āotearoa. My people have strived and maintained their knowledge and practices within a Western world paradigm.

My ancestors were warriors, pacifists, large landowners, farmers, agriculturalists, matriarchs and scholars. My great, great grandfather, Pirikāwau,3 was educated at Kings College in London, England. He became the scribe and translator to Governor Grey,4 Queen Victoria’s Royal Emissary, and Prime Minister to New Zealand. He was also a part of introducing the Māori King concept. He recorded many stories of early New Zealand colonisation and historical narratives of each region. His story is still untold.5

Ko wai koe? Ko au (Who are you? I am)

I was the first Māori woman6 to be open and public in Āotearoa about my HIV status. I was infected and diagnosed in 1993. This court case was highly publicised in 1993 as the first New Zealand criminal case of HIV transmission7 in which I was the complainant. I have a bachelor’s degree in Māori Laws and Philosophy, a bachelor’s degree in Administration and Māori, Bachelor’s degree in Public Health, Advanced Diploma in Business Systems, and a Diploma in Te Reo Māori.

I founded INA8 (Māori and Indigenous) HIV and AIDS Foundation in 2003 and received the Red Ribbon Award in 2016.9 I was the Chair of the International Indigenous Working Group on HIV10 from 2010 to 2020, the International Indigenous HIV and AIDS Community11 from 2016 to 2019, the Chair of the International Council of AIDS organisations from 2016 to2019, and the Chair of the International Community of Women living with HIV and AIDS from 2017 to 2019.12 I also received the Queen’s Order of Merit medal in 2017 for services to people living with HIV.

I worked globally with Indigenous Peoples and HIV and AIDS. I was a member of the Community Board of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria. I have served to represent Indigenous Peoples at many International AIDS Conferences and have been on numerous planning committees since 2010. I influenced changes to key populations to allow Indigenous Peoples as their Key Population. I served as the United Nations General Assembly Co-chair on HIV in 2016. My work influenced global policy changes to include Indigenous Peoples as a marginalised community in the HIV sector.

My driving goal has always been to translate and interpret Indigenous worldviews with Western worldviews about HIV and AIDS, which is sharing knowledge and advocating these worldviews. I have been published in medical journals and research studies several times, with numerous media articles under Marama Pala and Marama Mullen and published internationally.

A minority within a minority within a minority: a woman living with HIV, an Indigenous woman living with HIV, and a mother living with HIV

Through childbirth, I had my first journey of what today is called ‘Undetectable = Untransmittable’ (U=U). The father of my children and I were at an AIDS Ambassadors training seminar in Fiji in 2006. Both of us were living with HIV. I asked the group about having a child. One of the doctors at the seminar said that with both of us being undetectable and on the same medication. Therefore, conceiving a child without transmitting HIV before medication, the possibility of transmission was a one-in-four chance (25%); this was significantly reduced to less than 1%. An example of U=U, although not yet named or campaigned as such, U=U entirely aided me in deciding to have two children HIV free. This new knowledge also invoked my passion for educating communities so that people living with HIV can still have children.

My next barrier was facing the stigma and discrimination within my community and my Māori whānau and Hāpū (family and extended community). I became a strong advocate to debunk the belief that people with HIV cannot have children and that because of U=U, two parents living with HIV can still produce HIV-negative children. This also allowed me to become one of the international advocates for people living with HIV, tackling stigma and discrimination globally.

Comparison of U=U with an Indigenous Framework

This article will explore an adaption of one Māori Health Framework, examine the fundamentals of an Indigenous Framework related to U=U and how that can transpose internationally with Indigenous Peoples. We must examine the philosophy, history, and impact of colonisation. The collating of information is done by reviewing publications, speaking with community social workers and my personal experiences. This article will concentrate on the most straightforward and successful framework. That concept is universal among Indigenous cultures and can be easily transposed to U=U.

To have a culturally safe foundation and relevant adaption of U=U, one must acknowledge the current state of health of Indigenous Peoples and consider ways to enhance our social determinants of health. In New Zealand, we can access well-documented data that first show the long-standing inequalities in a range of outcomes between Māori and Non-Māori.13 The data show an over-representation of Māori results for poverty, gender-based violence, racism, incarceration, homelessness, education, drugs and alcohol, and health morbidities, including HIV rates. This over-representation is a direct result of colonisation. Māori life expectancy after colonisation fell from 30 to 23 years in the 1890s. The decline of the population after colonisation was so significant compared to the rise in immigrants from the United Kingdom.

The impact of infectious diseases – smallpox, influenza, and sexually transmitted infections, almost annihilated the entire population. At the turn of the 19th century, a population of 250 000 Māori had reduced to 40 000 at the start of the 20th century. The introduction of diseases was thought to be the main reason for the population decline.14 Survival became the main driving force of Māori for future generations. The Māori community focused on maintaining life and traditions while living in a hostile environment of oppression. Māori held traditional ritual funerals15 and built ‘nests’ for the language to survive.16

To view U=U through a Māori lens

The start for Indigenous conceptualising U=U. First has to come from the paradigm of the community17 before the individual. The sociology of Indigenous Peoples is not self-focused but community-focused, a break from the traditional non-Indigenous nuclear family – or self-serving individualism. We are raised to care and think of the whole community instead of the individual. We look at U=U to determine how this can be implemented through a community lens.18

Individual focus is centred on the benefits of the individual who can achieve U=U.

Here is an example of an education seminar held on a Marae (reservation) with 80 people in attendance 2019; this is a method of story telling to engage the community.

I could tell my uncle all the medical and statistical reasons how U=U works. But he will see that I, the person, still have this foreign virus in my blood that is dangerous and still present – uncured in his worldview. The word ‘Blood’ has ancient dialogues throughout all Indigenous Peoples’ cultures, and for Māori, it is very sacred and is directly linked to our earth and waterways.

If I say to uncle there is a contagion in the river, it’s small, it can’t hurt you, so you can still drink, swim and wash in that river, the eels and fish are acceptable, it’s of no consequence because it’s small. But regardless, it’s still there. And should the number increase, the river may need some treatment to make it small again. My Uncle would understand that concept easier.

The Community can relate and create a visual sense of what I’m relaying.

I have found through my own experience that when I speak to my community about HIV, I say that people living with HIV are ‘functionally cured19’ but still living with the virus. The words ‘functionally’ and ‘cured’ reduce the levels of the perception of danger. However, the remaining stigma and discrimination depends on the individual’s view. Not all community members will have the same mindset or understanding of how remarkable people living with HIV are. Regrettably, some will still stick to their beliefs about stigma and discrimination.

In 2008, I provided an information session at Auckland University explaining the virus and U=U, or the equivalent at the time. Shortly after finishing, we broke for a meal, and an Elder approached me and said, ‘In the old days, we would have put you all on an island and left you there’. At first, I was taken aback, but it is not the first time this opinion has been said to me. In the same year, Professor Sitaleki Finau called to have people living with HIV in the Pacific isolated from the rest of society.20 This outraged many and caused many issues and controversy involving stigma, discrimination, perceived authorities, faith-based organisations, socio-legal ramifications, human rights violations, radio personalities, politicians and media from one man’s uninformed opinion.

Yet, intrinsically, when a culture tries to survive annihilation, this concept is typical and not far-fetched for some. In 1906–1925, on Quail Island in New Zealand,21 settlers set up a post-colonisation leprosy colony, which showed us the fear of epidemic impacts on all races and nationalities. In contrast, although the epidemics were rife in New Zealand, Rua Kenana of the Tuhoe Nation in 1916, took his people up in the Urewera mountains to protect them from smallpox, influenza and conscription. He was named a Prophet for intercepting the onslaught of illness and war and taking his people to safety.22 Sadly, he was arrested for serving his people.

The word danger for Indigenous Peoples has many different intrinsic connotations based on generational trauma23 and resilience.24 For example, if you see a danger sign on the road, you take a detour to avoid the danger; however, from an Indigenous lens, both roads could present danger regardless of a sign saying it is safe. An Indigenous worldview will analyse every possible outcome. Because history has taught us no road is safe, we cannot trust the people that put the detour sign in place. Therefore, the detour sign in this paradigm is ‘Hey, this person is undetectable and untransmittable’; U=U. Road one is dangerous, but road two is slightly less risky. Society’s world views also differ within cultures or communities. A community of Indigenous Peoples could view U=U as a miracle and a sadness because the person still depends on medications to live, which could impact their quality of life, and that in turn could impact the community. The community could interpret this as, ‘Yes, she is living longer, but she is still controlled and dependent on medications’. She is not free; she is still dependent on the system that pays for and produces the medication that keeps her alive. From a Māori lens, this is seen as a prisoner to the system that is keeping her alive, similar to heart disease, cancer and diabetes. Western medicine becomes imperative to survive, but it comes with a sense of being ‘handcuffed’ to healthcare providers.

I cannot go and live on an island as my ancestors did throughout the Pacific Ocean or navigate the Pacific Ocean with contemporary Waka (canoes) that still traverse the Ocean.25 Personally, I experienced this after being offered a space on a traditional sea-bearing Waka, and I could not get a doctor’s approval because I am dependent on taking medication to live; the maximum amount of medication dispensed at any one time is 3 months. I have to have blood tests every 6 months. I cannot buy a boat and disappear into the Pacific for long periods or ‘go bush’, camp, hunt and forage for food. Māori traditional practices included teaching generations how to survive together with the land and the sea.

Community and U=U

From personal experience, I have dealt with health issues, genetic and chemical side-effects, fatigue and long-term toxicity. I could not participate in community activities like my peers if I did not live with HIV. The community will still have the virus in the forefront of their minds and would not feel they can rely or depend on that person like they would have in times before. Therefore a sense of isolation and being treated differently occurs to people living with HIV in the community. Many live in fear of their ‘secret’ being exposed, even when they would rather die than disclose or take medications (not all, but some face this reality among Māori living with HIV). The fear of losing their inherited position in the community will cost them their life.

There are no disclosure laws in New Zealand. There have been cases prosecuted under the New Zealand Crimes Act without specific HIV legislation. The legal precedence set by my court case involved intentional neglect under the Crimes Act. In New Zealand, if you conduct safe sexual practices, there is no need to disclose your HIV status. Because of U=U, this has changed the socio-legal aspect of transmission and disclosure.26

However, as mentioned earlier, the approach still lacks protection for Māori women, transgender Māori and Māori men. Gender-based violence in Māori households27 is overrepresented. Those statistics do not include cases of Māori and Pasifika women, transwomen, and men that do not disclose their status to their partners or family members for fear of violence, rejection and death. In many cases, they do not take medication to achieve U=U. They risk death, transmission to their partners, criminal charges from fear of disclosure, violence, rejection and stigma. This can happen regardless of the information they have regarding U=U. They are not ignorant or impaired in any way, but they are women and men desperately trying to survive at an elementary level. They make this very conscious choice. The psycho-social impact on women and men in these situations is immeasurable. There is still an extreme level of morbidity for this group of people. U=U is not practised. Adopting a culturally safe model of U=U will be difficult in these situations.

Circle or four cornerstones framework: example of a model28

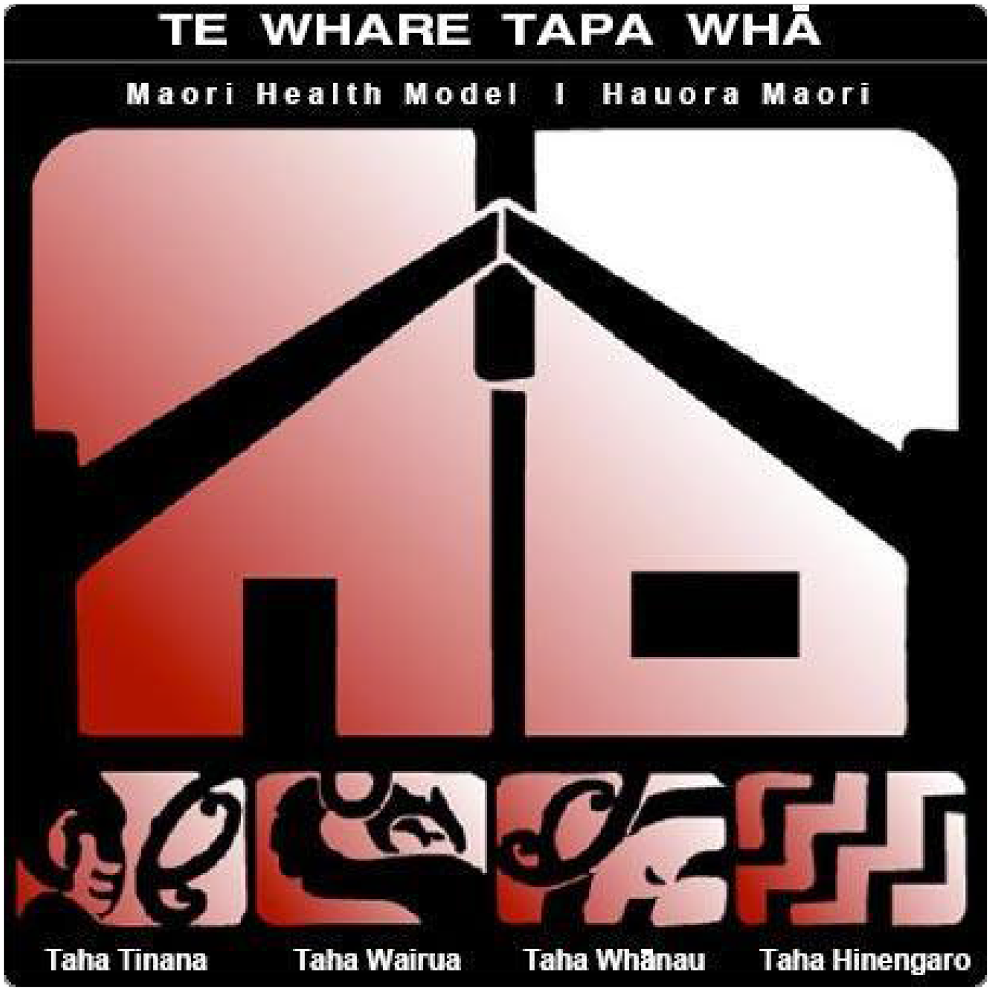

The following health model insert was developed by Dr Mason Durie.29 Māori widely use this model as a culturally safe and relevant model. It is similar to the Circle of Healing and is the Māori concept of Te Whare Tapa Whā (the Four Cornerstones or Pillars) (Fig. 1, Box 1). But there are many other models, and the link in Fig. 1 better provides a quick summary.30 Along with understanding Māori health in the past, present and future,31 and in order to highlight the constitutional rights of Indigenous Māori, all of the research, models and practices were further enhanced by Te Tiriti o Waitangi (the Treaty of Waitangi), a constitutional document between Māori and the Westminster Crown.32 This allows us to determine our wealth and health as Indigenous Māori.

Maori Health Model. This model was developed by Mason Durie (more information is available at https://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/populations/maori-health/maori-health-models/maori-health-models-te-whare-tapa-wha).

| Box 1. Te Whare Tapa Wha – Māori Health Model. |

| ‘With its strong foundations and four equal sides, the symbol of the four corners illustrates the four dimensions of Māori well-being. |

| Should one of the four dimensions be missing or somehow damaged, a person or a collective may become ‘unbalanced’ and subsequently unwell. |

| For many Māori, modern health services lack recognition of the spiritual dimension. In a traditional Māori approach, the inclusion of the spirit, the role of the family and the balance of the mind are as important as the physical manifestations of illness.’ |

| Physical Health |

| The capacity for physical growth and development. Good physical health is required for optimal development. Our physical ‘being’ supports our essence and shelters us from the external environment. For Māori, the physical dimension is just one aspect of health and wellbeing and cannot be separated from the aspect of mind, spirit and family. |

| Spiritual Health |

| The capacity for faith and wider communication. Health is related to unseen and unspoken energies. The spiritual essence of a person is their life force. This determines us as individuals and as a collective, who and what we are, where we have come from and where we are going. A traditional Māori analysis of physical manifestations of illness will focus on the spirit, to determine whether damage here could be a contributing factor. |

| Family Health |

| The capacity to belong, to care and to share where individuals are part of wider social systems, provides us with the strength to be who we are. This is the link to our ancestors, our ties with the past, the present and the future. Understanding the importance of family and how family can contribute to illness and assist in curing illness is fundamental to understanding Māori health issues. |

| Mental Health |

| The capacity to communicate, to think and to feel mind and body are inseparable. Thoughts, feelings and emotions are integral components of the body and soul. This is about how we see ourselves in this universe, our interaction with that which is uniquely Māori and the perception that others have of us.’ |

Results

Model comparison to U=U from a Māori worldview

I maintain physical health by taking life-saving medications. My virus is undetectable. This allows me to conceive, give birth and breastfeed.

As a Māori woman, procreation is essential to continue the generations; to protect the children of future generations (Whakapapa). I can have sexual partners and not transmit the virus. It gives me the freedom to be myself physically without judgment and fear. It allows me to live longer than my life expectancy before the medication. I acknowledge that I can continue a part of my role in my community as a woman and pass this skill set on to my future children. I still have physical worth to my community. Women living with HIV can still be repositories of knowledge like our ancestors; practising Indigenous knowledge of well-being through rituals and knowledge of flora and fauna.

Here is an example of traditional practices of medicine that work alongside western medicine. When first diagnosed, the first place I went to was a Tōhunga (traditional practitioner) Te Awhina Riwaka33 who practised these rituals and had knowledge of the medicinal properties of flora and fauna. She had worked with other people living with HIV, and worked in collaboration with Dr Hettie Rodenburg,34 general practitioner, until 1998. Together I received care from Te Awhina Riwaka for my physical and spiritual well-being and Dr Rodenburg, who endorsed Te Awhina and her practice while maintaining my health with western treatment. Both complimented one another. I felt these two remarkable women cared for all the realms of my well-being.

I am connected to my spiritual beliefs and ancestors and have a relationship with my life force and those important to me.

In the throes of survival as a people, religion has been a tool of colonisation for Māori. However, our spiritual beliefs are based on Women in Cosmogony; the creation story that each nation has a version of. Through strength-based approaches, we can connect to the Cosmogony of our Ancestors.35 My spiritual journey has been one of investigation and research of many religions and cultures. HIV never impacted my spiritual health. I firmly believed that I would not die from AIDS. It was only confirmation of my purpose in the world because Māori cosmogony transcends consciousness and generations. I am past, I am present, and I am the future. I never stand alone. This encompassing process also perceived that not only do I live with HIV, but so do my extended family and my community. We are all impacted by this foreign-introduced disease. Spirituality and knowledge are our only defence and reprieve.

My family are my security, safety and protection.

The impact of my status and public court case had long-reaching consequences and affected my immediate family, extended family and the community. It brought attention to where my people dwelled, my home and why I ended up in the situation that, leading to my HIV infection from a visitor to our lands. My family was there when I met this person on my Marae36 (Reserve). The ramifications included that my actions also stigmatised my entire family and community and led to rejection, banishment and ostracising of me and my immediate family from my traditional community. I had no privacy or recourse to keep my HIV status a secret.

In the early years of infection, people reacted in fear and would not allow me to practice the traditional roles I had learned.

I had been cursed, a member of my community stated. Paying for the sins of my mother and forefathers. The belief in superstition or supernatural influences was the real cause of my sickness.

My mother suffered more discrimination than I did. It was far easier for people to speak to my mother than approach me with their beliefs. When my community found out I was pregnant with my first child, a family member told my mother, ‘She’s being selfish; she’s going to die and lump you with her child.’

My immediate family were my stability. We faced this adversity together. It took time for my extended family and community to drop their prejudices against me. Regardless of my rejection, I claimed my space and a role in the community. I slowly showed them that I was safe to be around and that through my advocacy work, I could live by example and educate the community that I was Undetectable and Untransmittable. The televised birth of my child had been nationwide, and people started to break down their beliefs.

Instead of seeing death or surviving, they saw us thriving. I was as able to use media to educate others. Today, I feel supported by my family, extended family and community. U=U in practice opened their minds. This is my own experience. There are still people out there who will continue to judge and discriminate. But, overall, the health of my family is thriving. U=U freed us from persecution. In a sense, it created a new paradigm to accept me in inherited roles; if not in the traditional sense, in the contemporary sense.

Taking medication helps me live; I can talk openly and disclose my status without fear. My mental health is stronger, and with feelings and emotions, I can live with my status and function well in my community.

Mental health is circular and dependent again on the balance of all the above pillars. It’s never-ending, and in my journey, I have sought help many times throughout the past 30 years. Mentally and intellectually, U=U allows us to function the same as any other person in society. The lifting of the imminent death and contagious messages tuned out by the media in the 1990s is now differential with new diagnoses. It does not imply the negativity there was before medication and the result of U=U. Health providers can support their patients with the assurance that they will not die, and with medication, they will live long and productive lives. The bonus of not being contagious is empowering.

Self-stigma is more dangerous to mental well-being. Lack of knowledge and ignorance within your community supports that self-punishment. In my work, I have met countless people who fear what other people are thinking about them. Constantly believing any negative reaction is because ‘they know I have HIV’. U=U can support our mental well-being, but further work will always be needed to achieve that peace.

Conclusion

The goal of the Ū=Ū: Te Reo Māori (The life force given by the Mother’s breast) model is to balance all Four Pillars. The overarching goal is to improve the person’s health within the model. You cannot have any of these pillars without one leading to another. They are interdependent and equally interchangeable. U=U is about balance, which the balance of the Four Pillars can enhance. In particular, the balance of:

Physical health: Physically taking medication to suppress the virus, staying healthy, having access to health professionals, and looking after your body.

Spiritual health: Spiritually understanding that by doing this, you prolong your life, you deserve to be here, and you have an inherited right from your ancestors to live as a spiritual being. HIV does not define you or alter your spirituality. You are never alone.

Family health: Having the family support system, your partner or partner’s support and extended family support to participate as an integral part of your community. Just by taking medication, there is no limit to your family’s health and future.

Mental health: Knowing you no longer have to be concerned about transmitting the virus to your children or partner if you regularly present with undetectable viral loads. Mental health professionals can support you. You have the right to live, not only to survive, but thrive. Your mental health is the foundation for all the pillars, and it is reciprocal and essential.

All of these factors are an added dimension to a personal psyche. People not living with HIV still struggle to find this balance of the Four Pillars. As people living with HIV, there are no barriers to our well-being once we begin to see HIV not as a deficit but as a conduit to access all the support present and future. It is a unique process that is not always obvious in everyday situations. Ū=Ū: Te Reo Māori is not a framework for U=U and Indigenous Peoples. This model complements the U=U philosophy. They are intertwined.

Nāku it nei nā (humbly yours),

Marama Tamati

Acknowledgements (Ngā Mihi)

I acknowledge ngā Ātua (dieties) my ancestors, family members, extended family and community. My mother, Apihaka Mack, and my children, Kepas and Maiinga, my immeasurable support. To my mentors and care givers, Te Awhina Riwaka and Dr Hettie Rodenburg, thank you for believing in me when I did no’t. I would like to acknowledge Christian Hui for supporting me to be involved with this process, and advising me. Ngā mihi nui ki ā koe! ki ā koutou kātoa!

References

1 Department of Justice NZ. Ngātiawa/Te Āti Awa oral & traditional history report. 2018. Available at forms.justice.govt.nz/search/Documents/WT/wt_DOC_134104127/Wai%202200%2C%20A195.pdf [accessed 16 March 2023].

2 Te Aka. Māori dictionary. 2003. Available at maoridictionary.co.nz [accessed 17 March 2023].

3 Rahui P, Paul M. Te Ara – the encyclopedia of New Zealand. 2012. Available at http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/kingitanga-the-maori-king-movement/page-1 [accessed 19 March 2023].

4 Muncy DL. George Grey. 2021. Available at https://nzhistory.govt.nz/media/photo/george-grey-painting [accessed 20 March 2023].

6 Connor H, Bruning J, Napan K. Positive women: a community development response to supporting women and families living with HIV/AIDS in Aotearoa New Zealand. Unitec; 2016. Available at https://www.unitec.ac.nz/whanake/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Positive-Women.pdf [accessed 19 March 2023].

7 Crime.co.nz. Peter Mwai. 1993. Available at http://www.crime.co.nz/c-files.aspx?ID=36 [accessed 17 March 2023].

8 Pala M. Stigma and discrimination kills. 1993. Available at https://info.scoop.co.nz/INA_HIV-AIDS_Foundation [accessed 19 March 2023].

9 Reid A. Red Ribbon. UNAIDS; 2016. Available at www.unaids.org/en/resources/presscentre/pressreleaseandstatementarchive/2016/july/20160719_RedRibbonAward2016 [accessed 19 March 2023].

10 Canadian Aboriginal AIDS Network. International Indigenous Working Group on HIV & AIDS. Canadian Aboriginal AIDS Network; 2006. Available at https://Caan.Ca/Projects/Iiwgha/, caan.ca/projects/iiwgha [accessed 21 March 2023].

11 Canadian Aboriginal AIDS Network. International indigenous HIV and AIDS community. 2017. Available at https://iihac.org/ [accessed 21 March 2023].

12 International Council of AIDS Organisations. Marama Pala. 2017. Available at https://icaso.org/tag/marama-pala/ [accessed 19 March 2023].

13 Harris RB, Cormack DM, Stanley J. The relationship between socially-assigned ethnicity, health and experience of racial discrimination for Māori: analysis of the 2006/07 New Zealand Health Survey. BMC Public Health 2013; 13: 844.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

14 Pool I. Story: death rates and life expectancy. 2006. Available at https://teara.govt.nz/en/death-rates-and-life-expectancy/page-4 [accessed 17 March 2023].

15 Higgins R. Tangihanga – death customs. 2011. Available at https://teara.govt.nz/en/tangihanga-death-customs [accessed 19 March 2023].

16 Thomson R. Celebrating New Zealand’s first Kohanga Reo – 150 years of news. 2015. Available at www.stuff.co.nz/dominion-post/news/hutt-valley/73945639/celebrating-new-zealands-first-kohanga-reo---150-years-of-news#:~:text=Jean%20Puketapu%20and%20Dame%20Iritana,total%20Maori%2Dlanguage%20immersion%20setting [accessed 19 March 2023].

17 Cull I, Hancock RLA, McKeown S, Pidgeon M, Vedan A. A guide for front-line staff, student services, and advisors. 2009. Available at https://www.review.mai.ac.nz/mrindex/MR/article/download/243/243-1710-1-PB.pdf [accessed 19 March 2023].

18 Mane J. Kaupapa Māori: a community approach. MAI Rev 2009; 3: 1-9 Available at https://www.review.mai.ac.nz/mrindex/MR/article/download/243/243-1710-1-PB.pdf.

| Google Scholar |

19 Jones B, Ingham TR, Cram F, Dean S, Davies C. An indigenous approach to explore health-related experiences among Māori parents: the Pukapuka Hauora asthma study. BMC Public Health 2013; 13: 228.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

20 Otago Times. Massey distances itself from AIDs comments. 2008. Available at www.odt.co.nz/news/national/massey-distances-itself-aids-comments [accessed 19 March 2023].

21 Kingsbury B. The Dark Island leprosy in New Zealand and the Quail Island colony. 2019. Available at www.canterbury.ac.nz/alumni/our-alumni/alumni-authors/books/the-dark-island-leprosy-in-new-zealand-and-the-quail-island-colony.html#:~:text=From%201906%20to%201925%20Quail,a%20leprosy%20sufferer%20in%20Christchurch [accessed 19 March 2023].

22 New Zealand History. Rua Kēnana. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. 2022. Available at https://nzhistory.govt.nz/people/rua-kenana [accessed 19 March 2023].

23 Danieli Y. The treatment and prevention of long-term effects and intergenerational transmission of victimization: a lesson from Holocaust survivors and their children. In: Figley CR, editor. Trauma and its wake, Vol. 1. Brunner/Mazel; 1985. pp. 295–313. Available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/232461359_Families_of_survivors_of_the_Nazi_Holocaust_Some_short-_and_longterm_effects [accessed 19 March 2023].

24 Penehira M, Green A, Smith LT, Aspin C. Māori and indigenous views on R & R: resistance and resilience. MAI J 2014; 3: Available at www.journal.mai.ac.nz/content/m%C4%81ori-and-indigenous-views-r-r-resistance-and-resilience [accessed 19 March 2023].

| Google Scholar |

25 Keegan T. Rediscovering traditional Māori navigation. Science 1995; Available at Available at www.sciencelearn.org.nz/resources/597-rediscovering-traditional-maori-navigation [accessed 18 March 2023].

| Google Scholar |

26 Furley T. Man sentenced after knowingly infecting partner with HIV. 2017. Available at www.rnz.co.nz/news/national/331698/man-sentenced-after-knowingly-infecting-partner-with-hiv [accessed 19 March 2023].

27 New Zealand Family Violence Clearinghouse. Ethnic and community specific data. New Zealand Family Violence; 2021. Available at nzfvc.org.nz/family-violence-statistics/ethnic-specific-data [accessed 19 March 2023].

28 Durie M. Māori Health Models – Te Whare Tapa Whā. Ministry of Health; 2017. Available at www.health.govt.nz/our-work/populations/maori-health/maori-health-models/maori-health-models-te-whare-tapa-wha [accessed 19 March 2023].

29 Durie M. Mason Durie. 2019. Available at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mason_Durie [accessed 19 March 2023].

30 McIntosh J, Marques B, Mwipiko R. Therapeutic landscapes and indigenous culture: Māori health models in Aotearoa/New Zealand. In: Spee JC, McMurray A, McMillan M, editors. Clan and tribal perspectives on social, economic and environmental sustainability. Emerald Publishing Limited; 2021. pp. 143–58. doi:10.1108/978-1-78973-365-520211016 [accessed 19 March 2023].

31 Bryder L, Dow DA. Introduction: Maori health history, past, present and future. Health and History 2001; 3(1): 3-12 Available at http://www.jstor.org/stable/40111390 [accessed 19 March 2023].

| Google Scholar |

32 Kingi TKR. The treaty of Waitangi and Māori health. Te Pumanawa Hauora School of Maori studies, Massey University, Wellington NZ; 2006. Available at www.masseyuniversity.co.nz/massey/fms/Te%20Mata%20O%20Te%20Tau/Publications%20-%20Te%20Kani/T%20Kingi%20Treaty_of_Waitangi_Maori_Health1.pdf [accessed 19 March 2023].

33 Webb J. Te Whanau Kotahi Ora, centre for traditional Maori healing. National Library of New Zealand; 1999. Available at &natlib.govt.nz/records/23138737?search%5Bi%5D%5Bname_authority_id%5D=-173041&search%5Bpath%5D=items [accessed 19 March 2023].

34 King F. Dr Hetty Rodenburg. Broadbent and May; 2011. Available at www.broadbentandmay.co.nz/dr-hetty-rodenburg-grief-counsellor [accessed 19 March 2023].

35 Mikaere A, University of Auckland, International Research Institute for MaH¯ori Indigenous Education. The balance destroyed: the consequences for MaH¯ori women of the colonisation of Tikanga MaH¯ori/Ani Mikaere. Mana Wahine Monograph Series; Monograph 1. Auckland: Published jointly by the International Research Institute for MaH¯ori and Indigenous Education and A. Mikaere; 2003.

36 New Zealand Education. Study in New Zealand. Learn about MāOri culture. Naumai NZ. 2003. Available at naumainz.studyinnewzealand.govt.nz/goals/learn-about-maori-culture#:~:text=Marae%20are%20symbols%20of%20tribal,tribal%20celebrations%20and%20educational%20workshops [accessed 19 March 2023].