Mpox (monkeypox) knowledge, concern, willingness to change behaviour, and seek vaccination: results of a national cross-sectional survey

James MacGibbon A * , Vincent J. Cornelisse

A * , Vincent J. Cornelisse  B C , Anthony K. J. Smith

B C , Anthony K. J. Smith  A , Timothy R. Broady A , Mohamed A. Hammoud B , Benjamin R. Bavinton B , Dash Heath-Paynter D , Matthew Vaughan E , Edwina J. Wright F G H and Martin Holt

A , Timothy R. Broady A , Mohamed A. Hammoud B , Benjamin R. Bavinton B , Dash Heath-Paynter D , Matthew Vaughan E , Edwina J. Wright F G H and Martin Holt  A

A

A Centre for Social Research in Health, UNSW Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia.

B Kirby Institute, UNSW Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia.

C NSW Health, Sydney, NSW, Australia.

D Health Equity Matters, Sydney, NSW, Australia.

E ACON, Sydney, NSW, Australia.

F Department of Infectious Diseases, Alfred Hospital and Central Clinical School, Monash University, Melbourne, Vic., Australia.

G Burnet Institute, Melbourne, Vic., Australia.

H The Peter Doherty Institute of Infection and Immunity, Melbourne, Vic., Australia.

Abstract

In mid-2022, a global mpox (formerly ‘monkeypox’) outbreak affecting predominantly gay and bisexual men emerged in non-endemic countries. Australia had never previously recorded mpox cases and there was no prior research on knowledge or attitudes to mpox among gay and bisexual men across Australia.

We conducted a national, online cross-sectional survey between August 2022 and September 2022. Participants were recruited through community organisation promotions, online advertising, and direct email invitations. Eligible participants were gay, bisexual or queer; identified as male (cisgender or transgender) or non-binary; aged 16 years or older; and lived in Australia. The main outcome measures were: knowledge and concern about mpox; recognition of mpox symptoms and transmission routes; vaccination history; acceptability of behavioural changes to reduce mpox risk, and willingness to be vaccinated.

Of 2287 participants, most participants were male (2189/2287; 95.7%) and gay (1894/2287; 82.8%). Nearly all had heard about mpox (2255/2287; 98.6%), and the majority were concerned about acquiring it (1461/2287; 64.4%). Most of the 2268 participants not previously diagnosed with mpox correctly identified skin lesions (2087; 92%), rash (1977; 87.2%), and fever (1647; 72.6%) as potential symptoms, and prolonged and brief skin-to-skin contact as potential ways to acquire mpox (2124, 93.7%; and 1860, 82%, respectively). The most acceptable behavioural changes were reducing or avoiding attendance at sex parties (1494; 65.9%) and sex-on-premises venues (1503; 66.4%), and having fewer sexual partners (1466; 64.6%). Most unvaccinated and undiagnosed participants were willing to be vaccinated (1457/1733; 84.1%).

People at risk of mpox should be supported to adopt acceptable risk reduction strategies during outbreaks and to seek vaccination.

Keywords: attitudes, Australia, gay and bisexual men, men who have sex with men, monkeypox, mpox, sexual behaviour, sexual practice, sexually transmissible infection, vaccination, vaccine.

Introduction

Mpox (formerly ‘monkeypox’) is a viral zoonotic disease first identified in humans in 1970 and is endemic in central and west African countries.1 In May 2022, health authorities identified an emerging mpox outbreak in non-endemic countries, in which >95% cases were recorded among gay and bisexual and other men who have sex with men (GBMSM).1,2 In July 2022, the World Health Organization declared mpox a public health emergency of international concern.2 Australia made mpox a nationally notifiable disease in June 2022 and declared the mpox outbreak a Communicable Disease Incident of National Significance (CDINS) in July 2022.3 In late November 2022, the CDINS declaration was withdrawn.3

Mpox spreads primarily through direct contact with infected skin and bodily fluids, and by large respiratory droplets.4 Despite initial concerns of fomite transmission via contaminated surfaces, to date no such transmission has been confirmed during the current outbreak.4,5 Mpox infection is self-limited, with most mpox symptoms typically resolving within 2–4 weeks.6–8 Clinical care, including hospitalisation may be required to manage secondary bacterial infections, ocular and gastrointestinal involvement and severe pain.6,7 A systematic review found that 14% of mpox cases have resulted in hospitalisation, but only 6% of cases in the 2022 outbreak required hospitalisation.9 Mpox is rarely fatal.6,7 The 2022 mpox outbreak resulted in more than 85 000 mpox cases being recorded in 103 non-endemic countries, with more than 140 fatalities.10 Globally, the number of incident infections in the 2022 outbreak peaked in August at around 1000 cases daily, and declined after that.11 Australia recorded its first mpox cases in May 2022, and 145 cases by July 2023, approximately two-thirds of which were acquired overseas.10

Vaccinia vaccines, developed to protect against smallpox, offer protection against mpox.12,13 In August 2022, the Australian Government acquired a limited supply of third-generation, non-replicating Modified Vaccinia Ankara (MVA) vaccine, and from August 2022 the vaccines were targeted to people at highest risk of exposure to mpox virus or severe mpox illness.14,15 As was observed during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, particularly before widespread vaccine availability,16,17 we anticipated that GBMSM would likely follow public health advice, promoted via community organisations, and adapt their behaviour to reduce their risk of acquiring mpox virus until they are vaccinated; for example by reducing the number of untraceable sexual partners and attendance at sex-on-premises venues and sex parties. Based on experience with COVID-19, we anticipate most GBMSM will be willing to be vaccinated against mpox.18,19

Since this study was originally conceived, other research has begun to examine mpox knowledge and vaccine intention among gay and bisexual men. A Dutch study conducted in July 2022 found that participants had difficulty correctly identifying images of mpox from other skin conditions, and 70% of the 394 participants were willing to be vaccinated against mpox.20 High vaccine acceptance (82%) was observed in a large survey of 32 902 GBMSM across Europe conducted between 30 July 2022 and 12 August 2022.21 The highest levels of vaccine acceptance were observed in northern, Mediterranean and western Europe (84–87%), and the lowest levels were in central, eastern, and south-east Europe (66–67%).21 In the same study, vaccine willingness was related to perceived mpox severity, concern about acquiring mpox, and having been diagnosed with a sexually transmissible infection (STI) in the past 12 months, among other factors. In the United Kingdom, 1932 participants (90% of whom were GBMSM) were surveyed in June–July 2022.22 Most of the participants (86%) were willing to be vaccinated. Bisexual and heterosexual-identifying participants, people who struggled to afford their basic needs, and participants who identified as being from a non-White heritage group were less willing to be vaccinated, among other factors.22 Within Australia, 563 gay and bisexual men and transgender women from the state of Victoria were surveyed in August–October 2022, with recruitment mainly occurring in clinics. This study found high levels of recognition of mpox transmission routes and symptoms, that 37% of the sample had been vaccinated against mpox, and 68% of the unvaccinated participants were willing to be vaccinated.23

To identify education and health promotion needs for people at risk of mpox across Australia, and help guide the national vaccination program, we examined what GBMSM and non-binary people knew about mpox virus and what behavioural changes they would be prepared to undertake in response to the outbreak. We anticipated that greater concern about mpox would be associated with a greater willingness to modify behaviour and to seek vaccination.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

A national Australian, cross-sectional survey was conducted between 24 August 2022 and 12 September 2022 using Qualtrics software (Provo, UT, USA). The survey was promoted through community partner organisations and paid advertisements on Facebook and Grindr, supplemented by email invitations to consenting participants of previous studies. Potential participants were directed to the study website, containing participant information and the survey link. Participants provided consent before starting the survey. Eligible participants identified as gay, bisexual or queer (GBQ); identified as male (cisgender or transgender) or non-binary; were aged 16 years or older; and lived in Australia. Non-binary participants self-selected to take part in the survey; that is, they were not excluded based on gender presumed at birth or recent sexual history as long as they identified as GBQ; we believed that non-binary people who identified as GBQ were part of the target population affected by mpox and that was sufficient reason to participate. The study was approved by the ethics committee of UNSW Sydney (HC220484) and the community organisation ACON (2022/14).

Measures

We collected data on demographics, physical health, recent sexual practices, HIV status, HIV treatment or pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), STI testing and history, vaccination history against smallpox or mpox, knowledge and concern about mpox, acceptability of behavioural changes in response to mpox, and willingness to be vaccinated. Adaptive routeing was used to exclude irrelevant items, and response options in long lists were randomised to reduce order bias. Participants who had been diagnosed with mpox were shown questions about their experience of mpox (not discussed in this article). The main outcome measures are detailed in Appendix 1 (see Supplementary materials).

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were computed for all variables. Pearson’s chi-squared tests identified significant associations between independent and dependent variables, and logistic regression was used to identify independent associations for key dependent variables (i.e. behavioural change measures and vaccine willingness). Multivariable analyses used block entry of variables that were significant at the bivariable level. Statistical assumptions were assessed, including model diagnostics for logistic regression, none of which were violated. Variables in the regression models had no missing observations. We report unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05 (two-tailed). Analyses were conducted using Stata ver. 16.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Human ethics approval

The questionnaire and methodology for this study were approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of UNSW Sydney (HC220484) and endorsed by the community organisation ACON (2022/14). Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study prior to their participation in the questionnaire.

Results

The survey was completed by 2287 of 3232 eligible people who commenced it (70.8% completion rate). The median age of the 2287 participants was 40 years (IQR = 31–51), 1894 (82.8%) identified as gay, 2189 (95.7%) were male, 1701 (74.4%) were Australian born, 1550 (67.8%) were university educated, 1647 (72.0%) reported full-time employment, and 1877 (82.1%) lived in the capital city of their state/territory. Most participants lived in New South Wales (860; 37.6%) or Victoria (760; 33.2%). In total, 1944 (85%) were HIV-negative, 179 (7.8%) were HIV-positive, and 164 (7.2%) were untested or did not know their status. Within the prior 12 months, more than two thirds of the sample had been tested for HIV (1634; 71.5%) or other STIs (1616; 70.7%). In total, 1241 (54.3%) participants had ever used PrEP and 914 (40%) were taking PrEP at the time of the survey. Further details of participant characteristics are shown at Appendix 2, Table S1 (see Supplementary materials).

Previous vaccination against smallpox or mpox

Nearly one quarter of participants had ever received a smallpox or mpox vaccine (541/2287; 23.7%). Most had received MVA vaccine (325/541; 60.1% of vaccinated participants or 14.2% of the total sample), a small proportion had received replication-competent second generation vaccinia vaccine (ACAM2000) (28/541; 5.2%), and more than one third did not know which vaccine they had received (188/541; 34.8%). Most were vaccinated after May 2022 (347/541; 64.1%), and had received the vaccine before potential exposure to mpox (283/347; 81.6%). Fifteen participants were vaccinated after potential exposure (15/347; 4.3%), and the remainder reported they received the vaccine for ‘another reason’; that is, unrelated to potential exposure to mpox (49/357; 14.1%). Of participants vaccinated with MVA, most had received only one dose (320/325; 98.5%) and most received it in Australia (295/325; 90.8%). Further details of previous vaccination are shown in Appendix 2, Table S2.

Potential mpox risk factors

Of the 2287 participants, 706 (30.9%) had travelled overseas in the previous 6 months, and 1075 (47%) planned to travel in the next 6 months. In the 6 months preceding the survey, 599 (26.2%) participants had more than 10 male sexual partners, 1277 (55.8%) reported casual sex with male partners without condoms, 1248 (54.6%) reported anonymous sex, 804 (35.2%) reported group sex, and 731 (32%) had visited a sex-on-premises venue. Compared with unvaccinated participants, participants vaccinated since May 2022 were more likely to report recent and future overseas travel, and other potential mpox risk factors (see Appendix 2, Table S3 for comparisons).

Mpox knowledge and concern

Of the 2268 participants who had not been diagnosed with mpox, 32 (1.4%) had never heard of mpox before the survey, 1065 (47%) knew a ‘small amount’, 695 (30.7%) a ‘fair amount’, 356 (15.7%) ‘quite a bit’ and 120 (5.3%) ‘a lot’. The most common ways to learn about mpox were the media (1904/2255; 84.4%), conversations with friends or family (729/2255; 32.3%), and information provided by community organisations (660/2255; 29.3%). Among the 2268 undiagnosed participants, 323 (14.2%) knew someone who had been diagnosed with mpox, 1461 (64.4%) were concerned or very concerned about acquiring mpox, and 465 (20.5%) believed it likely or very likely they would acquire mpox. Vaccinated participants were more likely to report mpox knowledge and concern compared to unvaccinated participants, but there was no difference in perceived likelihood of acquiring mpox (see Appendix 2, Table S4 for all comparisons).

Recognition of mpox symptoms and transmission routes

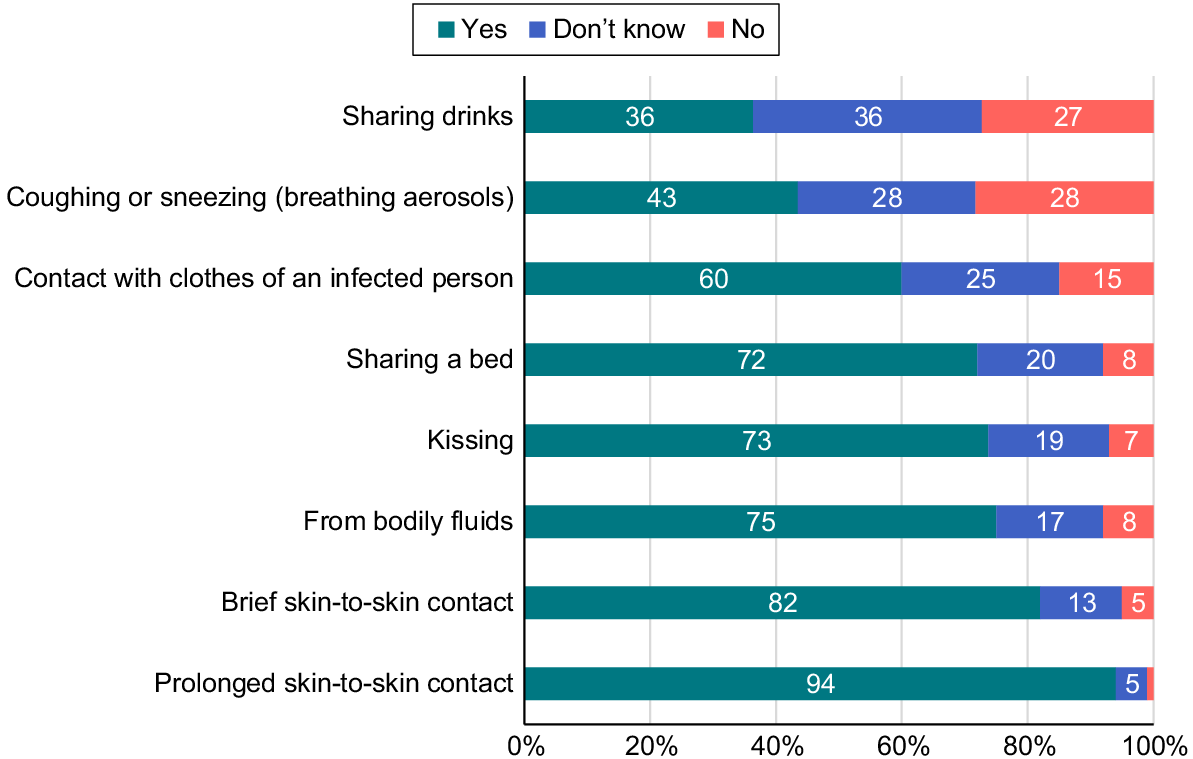

The 2268 undiagnosed participants were asked to identify potential mpox symptoms and transmission routes. The most commonly identified symptoms were skin lesions (2087; 92%), skin rash (1977; 87.2%), and fever (1647; 72.6%). Fig. 1 shows other symptoms and uncertainty about potential symptoms (ranging from 5% to 43% for ‘don’t know’ responses).

Mpox symptom identification by 2268 participants who had not been diagnosed with mpox. All potential mpox symptoms were presented in random order. Three ‘decoy’ symptoms were included in the survey but are not reported here, e.g. ‘loss of taste or smell’.

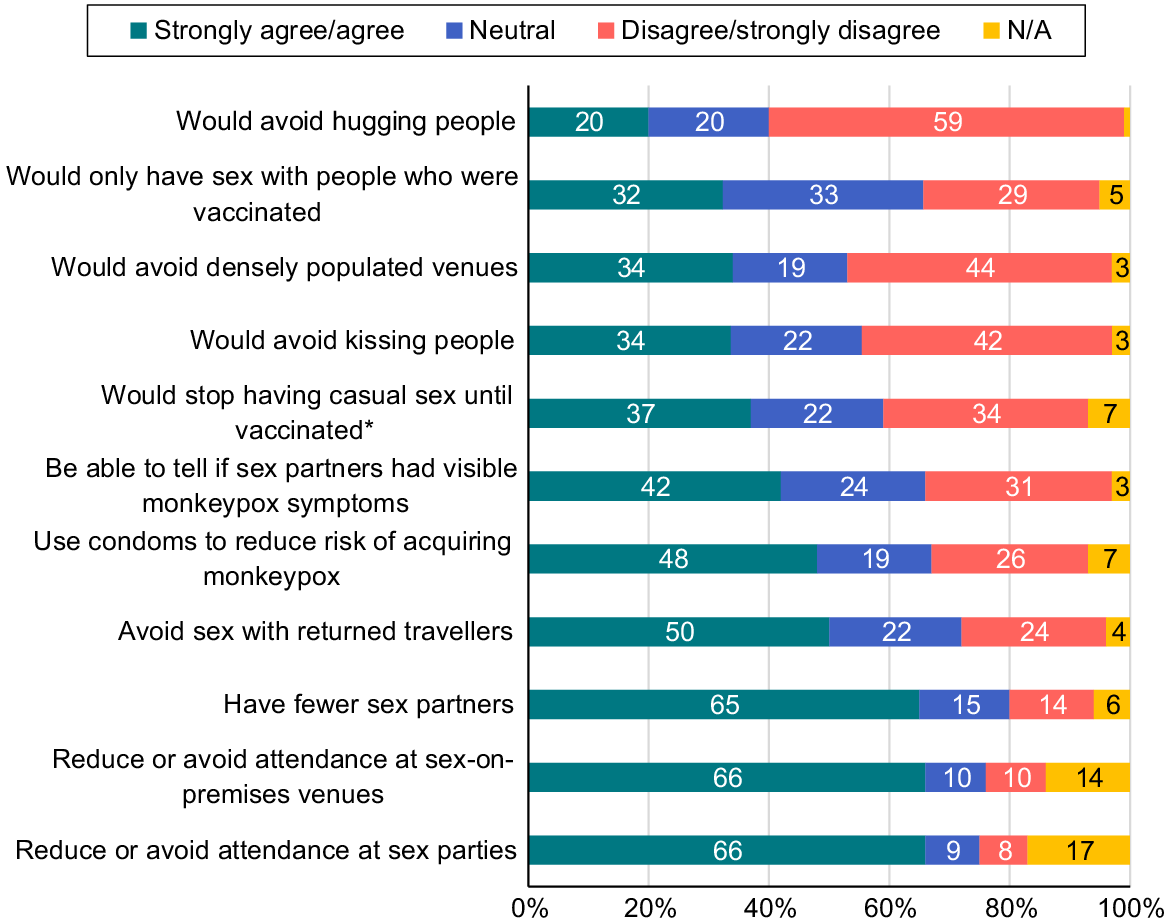

Most participants identified prolonged skin-to-skin contact (2124; 93.7%), brief skin-to-skin contact (1860; 82%) and contact with bodily fluids (1692; 74.6%) as potential ways to acquire mpox. Fig. 2 shows knowledge of transmission routes and uncertainty about them (ranging from 5% to 36%). Participants with more than 10 male sexual partners in the previous 6 months were more likely to recognise potential mpox symptoms (and some transmission routes) compared to those with fewer partners (see Appendix 2, Table S5 for all comparisons).

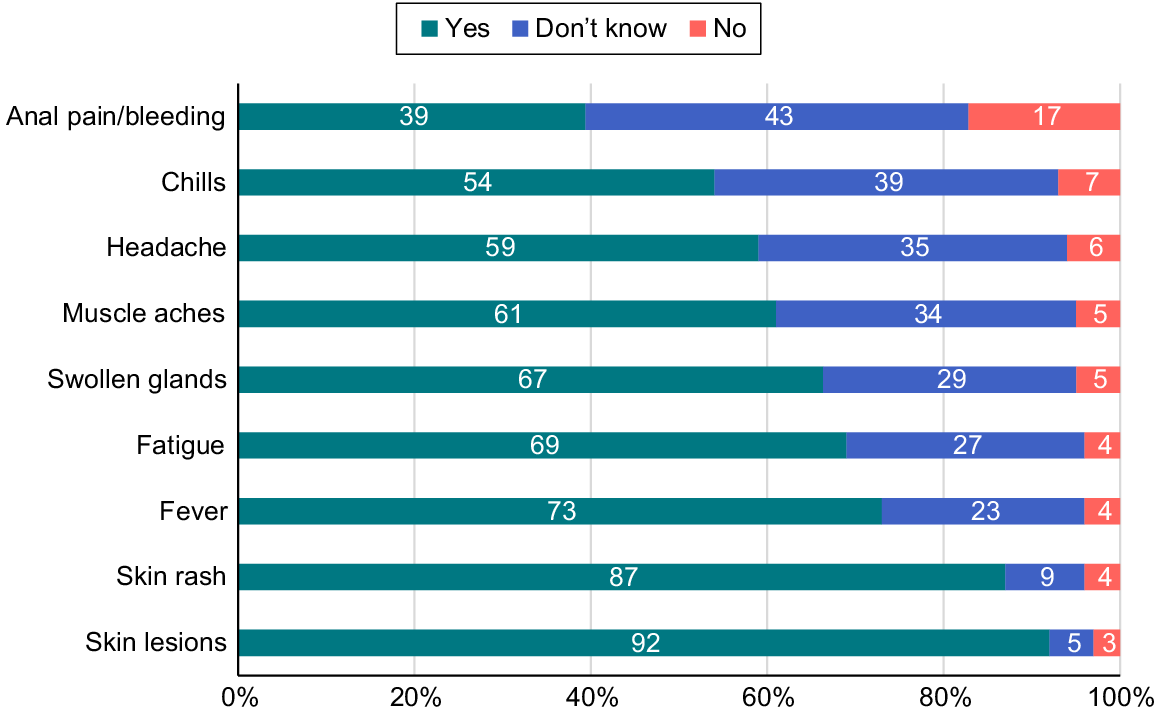

Acceptability of behavioural changes in response to mpox

Fig. 3 shows the acceptability of different behavioural changes among the 2268 undiagnosed participants. The most acceptable strategies were reducing or avoiding attendance at sex parties (1494; 65.9%) and sex-on-premises venues (1503; 66.4%), and having fewer sexual partners (1466; 64.6%). Multivariable analyses showed that concern about mpox and vaccination since May 2022 were independently associated with greater acceptability of these three strategies (see Appendix 2, Table S6 for multivariable results). The least acceptable strategies were not hugging people (445; 19.6%), avoiding densely populated venues (760; 33.5%), and not kissing people (771; 34%). Most participants were willing to avoid contact with people if diagnosed with mpox (2110/2268; 93%), but fewer participants were confident they could avoid physical contact with people (1660/2268; 73.2%), work from home (1588/2268; 70%), or not share communal living spaces such as a bathroom, kitchen or bedroom (1222/1268; 53.9%). More than half of participants were comfortable with contact tracers disclosing a potential mpox diagnosis to casual sex partners (1377/2268; 60.7%; see Appendix 2, Table S7 for further details).

Willingness to be vaccinated against mpox

Among the 1733 participants who were unvaccinated and had not been diagnosed with mpox, 1457 were willing to be vaccinated (84.1%). Most were willing to receive the vaccine immediately as a precautionary measure (1337/1733; 77.2%); a smaller proportion indicated they would be vaccinated later if more mpox cases were reported in Australia (268/1733; 15.5%). Among the 1486 participants who had at least one male casual sex partner in the previous 6 months, vaccine acceptability was similar to the broader group (1275/1486, 85.8% vs 1457/1733, 84.1%). Multivariable analysis showed bisexual participants and those who were unconcerned about mpox were less willing to be vaccinated and participants with greater numbers of recent sexual partners were more willing (see Appendix 2, Table S8 for multivariable results).

Discussion

This was the first national study of knowledge and attitudes to mpox among GBMSM in Australia. Most participants accurately identified common clinical symptoms (skin lesions and/or rash) and transmission routes (skin-to-skin contact), similar to findings from the state of Victoria.23 Early recognition of symptoms is an important component of public health responses to an infectious disease outbreak.

Nearly one quarter of participants reported a history of smallpox or mpox vaccination. As Australia never had universal smallpox vaccination24,25 and estimates suggest only 10% of contemporary Australians have been vaccinated against smallpox,26 it is likely that some participants mistakenly believed they had been vaccinated.27 It is unknown whether mistaken beliefs about historical vaccination may deter people from seeking vaccination against mpox, but it may be important for public education campaigns to highlight the limited coverage and protection offered by historical smallpox vaccination.7

As we anticipated, almost two thirds of participants were willing to modify their sexual practices to reduce their risk of acquiring mpox (e.g. avoiding sex parties, sex-on-premises venues or having fewer sex partners). However, changes to social practices, such as avoiding hugging or kissing, or avoiding popular venues, were rated as less acceptable. It is possible that changes to social behaviour were perceived as less acceptable after COVID-19 restrictions in Australia (‘pandemic fatigue’)28 and because GBMSM correctly surmised that prolonged skin-to-skin contact represented a greater transmission risk. Previous research has found that GBMSM are unwilling to avoid kissing to reduce the risk of gonorrhoea.29 However, COVID-19 research showed that GBMSM modified their sexual practices to reduce transmission risk, particularly in the absence of vaccine protection,17,19 gradually increasing levels of sexual activity after they were vaccinated.30 It is difficult for people to sustain behaviour that has a personal or social cost over time,31 so public health messages should consider what behaviour change may be achievable and acceptable for GBMSM during mpox outbreaks, in order for messaging to be effective. Ongoing surveillance of sexual behaviour, vaccine uptake, and behaviour change in response to mpox would be useful.

Lastly, we found a very high willingness to receive mpox vaccination, which was higher than that observed in one state-based survey in Australia,23 but similar to levels observed in European studies.21,22 Few factors distinguished between participants who were willing to be vaccinated or not, although bisexual participants and people who were less concerned about mpox were less willing, and people with more sexual partners were more willing. In general, this aligns with community-oriented messaging about mpox vaccination, which encouraged more sexually active people to come forward first, when local health authorities prioritised vaccines for those deemed to be at greatest risk of mpox. Our results are consistent with findings from a UK study that found bisexual participants were less willing to accept an mpox vaccine.22 Our results are also consistent with findings from a European study that found mpox concern was strongly associated with vaccine acceptance.21 If mpox vaccination continues to be encouraged among sexually active GBMSM, our results suggest that targeted messaging for bisexual men may be warranted, explaining why vaccination is beneficial, and how vaccination may be accessed safely and discreetly. Such messaging may be particularly important to increase mpox vaccination rates to reduce the risk of future outbreaks, given mpox may circulate globally at low levels for the foreseeable future.

Limitations

We acknowledge the limitations of the analysis, which included the study’s non-random and convenience-based sample. As there are limited national data on GBMSM and non-binary people, the representativeness of our sample is unknown. However, the cross-sectional sample comprised a large proportion of people who were at potential risk of acquiring mpox (i.e. participants who reported potential risk behaviours, recent travel and future travel plans). Further, 19 (14.7%) of the 129 people (as of 12 September 2022) who had been diagnosed with mpox in Australia responded to the survey.11 Participants from New South Wales and Victoria, where most mpox cases were reported, were overrepresented in the sample compared to participants from other Australian states and territories.3 Our findings may therefore reflect the experiences of people with greater interest in mpox or those at risk of acquiring mpox in Australia.

Conclusion

Despite the rapid global emergence of mpox in 2022, Australia avoided a large-scale local mpox outbreak.10 This likely reflects temporary behaviour changes made by GBMSM to reduce risk, vigilance about symptoms, and the uptake of vaccination once it became available. Preventing future outbreaks can be achieved through widespread mpox vaccination of at-risk people, and targeted education and awareness raising among GBMSM to explain the importance of temporary modifications of sexual practices during outbreaks, particularly if they are unvaccinated. Modelling from the US, for example, suggests that vaccination coverage needs to be 50% or greater among GBMSM to prevent or limit future mpox outbreaks,32 and our study and Australian research suggests that coverage was well below that level in 2022.23 Our survey found high levels of willingness to receive mpox vaccination, but some groups, namely bisexual men and GBMSM with lower numbers of sexual partners, may benefit from encouragement and support to get vaccinated. Our survey indicates that GBMSM are willing to modify some sexual practices to reduce their risk of mpox, but we caution that such behaviour modification may not be sustainable in the longer term, and hence risk reduction messaging must be carefully timed to achieve maximal impact during periods where there is a risk of transmission. Together, our findings suggest many GBMSM seek to protect their own and others’ sexual health, but some groups may need additional support to access health information, vaccination, and health services. While case numbers are currently low, Australia should seize the opportunity to increase vaccination coverage to reduce the chance of future outbreaks.

Data availability

A deidentified dataset may be available from the authors upon reasonable request, subject to ethical oversight being obtained by bona fide researchers. Syntax for the database coding and analysis may be available upon request.

Conflicts of interest

Benjamin Bavinton, Vincent Cornelisse, Martin Holt and Anthony KJ Smith are Associate Editors of Sexual Health. To mitigate this potential conflict of interest they were blinded from the review process.

Declaration of funding

The Centre for Social Research in Health and Kirby Institute receive funding from the Australian Government Department of Health and from state/territory health departments (e.g. NSW Ministry of Health). The funding sources did not have any involvement in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, or in the writing of this manuscript and decision to submit for publication. No pharmaceutical funding was received for this study.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study design, analysis and interpretation of findings. James MacGibbon, Timothy R Broady and Martin Holt oversaw data collection. James MacGibbon drafted the manuscript and conducted the quantitative analyses, supported by Vincent Cornelisse and Martin Holt. All authors reviewed and commented on drafts of the manuscript and agreed with the final version.

Acknowledgements

An earlier version of this article was published as an unrefereed preprint on MedRxiv (https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.12.01.22282999). In-kind creative services for the study recruitment materials and website were provided by Oskar Westerdal and Vincent Rommelaere. We are grateful to Professor Andrew Grulich and Timmy Lockwood who provided advice on the survey instrument.

References

1 Endo A, Murayama H, Abbott S, Ratnayake R, Pearson CAB, Edmunds WJ, et al. Heavy-tailed sexual contact networks and monkeypox epidemiology in the global outbreak. Science 2022; 378(6615): 90-4.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

2 Thornhill JP, Barkati S, Walmsley S, Rockstroh J, Antinori A, Harrison LB, et al. Monkeypox virus infection in humans across 16 countries — April–June 2022. N Engl J Med 2022; 387(8): 679-91.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

3 Australian Government: Department of Health and Aged Care. Mpox (monkeypox) health alert 2023. Available at https://www.health.gov.au/diseases/monkeypox-mpox

4 Kumar N, Acharya A, Gendelman HE, Byrareddy SN. The 2022 outbreak and the pathobiology of the monkeypox virus. J Autoimmun 2022; 131: 102855 PMID:.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

5 US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Science brief: detection and transmission of monkeypox virus 2022. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/about/science-behind-transmission.html

6 Girometti N, Byrne R, Bracchi M, Heskin J, McOwan A, Tittle V, et al. Demographic and clinical characteristics of confirmed human monkeypox virus cases in individuals attending a sexual health centre in London, UK: an observational analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2022; 22(9): 1321-8 PMID:.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

7 MacIntyre CR, Grulich AE. Is Australia ready for monkeypox? Med J Aust 2022; 217(4): 193-4 PMID:.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

8 World Health Organization. Mpox (monkeypox). World Health Organization; 2023. Available at https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/monkeypox

9 DeWitt ME, Polk C, Williamson J, Shetty AK, Passaretti CL, McNeil CJ, et al. Global monkeypox case hospitalisation rates: a rapid systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine 2022; 54: 101710 PMID:.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

10 US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2022 Monkeypox outbreak global map. 2023. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/response/2022/world-map.html [accessed 6 July 2022]

11 Mathieu E, Spooner F, Dattani S, Ritchie H, Roser M. Monkeypox. OurWorldInData.org; 2022. Available at https://ourworldindata.org/monkeypox

12 Hammarlund E, Lewis MW, Carter SV, Amanna I, Hansen SG, Strelow LI, et al. Multiple diagnostic techniques identify previously vaccinated individuals with protective immunity against monkeypox. Nat Med 2005; 11(9): 1005-11 PMID:.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

13 Rizk JG, Lippi G, Henry BM, Forthal DN, Rizk Y. Prevention and treatment of monkeypox. Drugs 2022; 82(9): 957-63 PMID:.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

15 Chow EPF, Chen MY, Bradshaw CS, Towns JM, Fairley CK. Accessing first doses of mpox vaccine made available in Victoria, Australia. Lancet Reg Health West Pac 2023; 31: 100712.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

16 Murphy D, Ellard J, Maher L, Saxton P, Holt M, Haire B, et al. How to have sex in a pandemic: the development of strategies to prevent COVID-19 transmission in sexual encounters among gay and bisexual men in Australia. Cult Health Sex 2022; 1-16.

| Google Scholar |

17 Hammoud MA, Maher L, Holt M, Degenhardt L, Jin F, Murphy D, et al. Physical distancing due to COVID-19 disrupts sexual behaviors among gay and bisexual men in Australia: implications for trends in HIV and other sexually transmissible infections. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2020; 85(3): 309-15 PMID:.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

18 Holt M, MacGibbon J, Bavinton B, Broady T, Clackett S, Ellard J, et al. COVID-19 vaccination uptake and hesitancy in a national sample of Australian gay and bisexual men. AIDS Behav 2022; 26(8): 2531-8 PMID:.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

19 Prestage G, Storer D, Jin F, Haire B, Maher L, Philpot S, et al. COVID-19 vaccine uptake and its impacts in a cohort of gay and bisexual men in Australia. AIDS Behav 2022; 26(8): 2692-702 PMID:.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

20 Wang H, d’Abreu de Paulo KJI, Gültzow T, Zimmermann HML, Jonas KJ. Monkeypox self-diagnosis abilities, determinants of vaccination and self-isolation intention after diagnosis among MSM, the Netherlands, July 2022. Euro Surveill 2022; 27(33): 2200603.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

21 Reyes-Urueña J, D’Ambrosio A, Croci R, Bluemel B, Cenciarelli O, Pharris A, et al. High monkeypox vaccine acceptance among male users of smartphone-based online gay-dating apps in Europe, 30 July to 12 August 2022. Euro Surveill 2022; 27(42): 2200757.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

22 Paparini S, Whitacre R, Smuk M, Thornhill J, Mwendera C, Strachan S, et al. Public understanding and awareness of and response to monkeypox virus outbreak: a cross-sectional survey of the most affected communities in the United Kingdom during the 2022 public health emergency. HIV Med 2023; 24(5): 544-57 PMID:.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

23 Chow EPF, Samra RS, Bradshaw CS, Chen MY, Williamson DA, Towns JM, et al. Mpox knowledge, vaccination and intention to reduce sexual risk practices among men who have sex with men and transgender people in response to the 2022 mpox outbreak: a cross-sectional study in Victoria, Australia. Sexual Health 2023;

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

25 Costantino V, Trent MJ, Sullivan JS, Kunasekaran MP, Gray R, MacIntyre R. Serological immunity to smallpox in New South Wales, Australia. Viruses 2020; 12(5): 554.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

26 MacIntyre CR, Costantino V, Chen X, Segelov E, Chughtai AA, Kelleher A, et al. Influence of population immunosuppression and past vaccination on smallpox reemergence. Emerg Infect Dis 2018; 24(4): 646-53 PMID:.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

27 Durrheim DN, Muller R, Saunders V, Speare R, Lowe JB. Australian public and smallpox. Emerg Infect Dis 2005; 11(11): 1748-50 PMID:.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

28 World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe. Pandemic fatigue: reinvigorating the public to prevent COVID-19: policy framework for supporting pandemic prevention and management: revised version November 2020. 2020. Available at https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/337574

29 Chow EPF, Walker S, Phillips T, Fairley CK. Willingness to change behaviours to reduce the risk of pharyngeal gonorrhoea transmission and acquisition in men who have sex with men: a cross-sectional survey. Sex Transm Infect 2017; 93(7): 499-502 PMID:.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

30 Holt M, Chan C, Broady TR, Mao L, MacGibbon J, Rule J, et al. Adjusting behavioural surveillance and assessing disparities in the impact of COVID-19 on gay and bisexual men’s HIV-related behaviour in Australia. AIDS Behav 2023; 27: 518-34.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

31 Kelly MP, Barker M. Why is changing health-related behaviour so difficult? Public Health 2016; 136: 109-16 PMID:.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

32 Pollock ED, Clay PA, Keen A, Currie DW, Carter RJ, Quilter LAS, et al. Potential for recurrent Mpox outbreaks among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men – United States, 2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2023; 72(21): 568-73.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |