Community-based COVID-19 vaccination services improve user satisfaction: findings from a large household survey in Bali Province, Indonesia

I. Made Dwi Ariawan A , Anak Agung Sagung Sawitri A , Putu Cintya Denny Yuliyatni A , Desak Nyoman Widyanthini A and I. Nyoman Sutarsa A B *A

B

Abstract

Understanding community preferences for vaccination services is crucial for improving coverage and satisfaction. There are three main approaches for COVID-19 vaccination in Indonesia: health facility-based, community-based, and outreach approaches. This study aims to assess how the vaccination approaches impact user satisfaction levels.

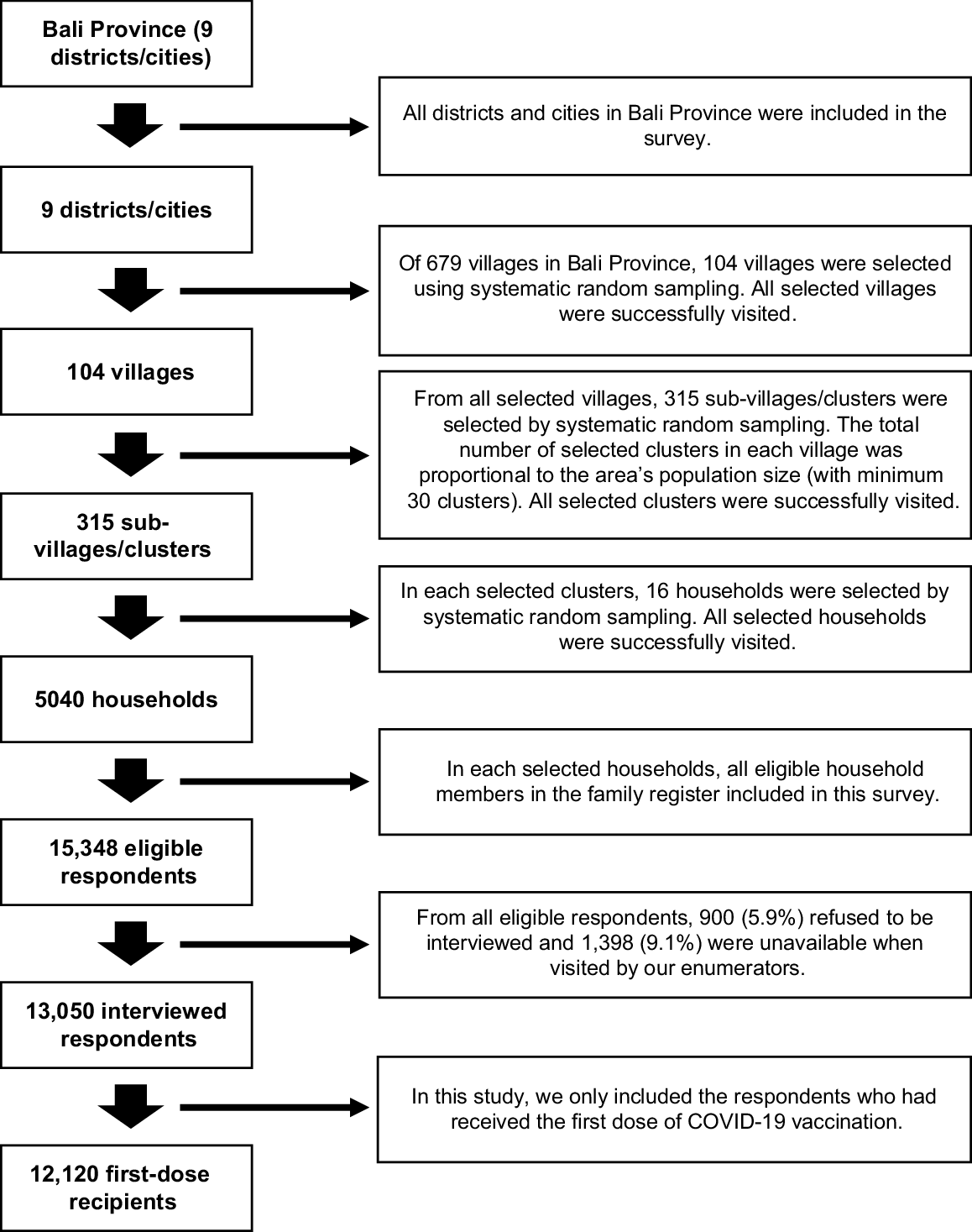

This study was part of a large household survey involving 12,120 respondents across nine districts in Bali Province. The study population comprised all residents aged ≥12 years who had received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccination. Samples were selected through three stages of systematic random sampling. Data were collected through interviews using structured questionnaires, which included socio-demographic characteristics, vaccination services, and satisfaction levels. Analysis was performed using Chi Square test and logistic regression, with the entire process incorporating weighting factors.

A total of 12,120 respondents reported receiving their first dose of COVID-19 vaccination. The satisfaction level among vaccine recipients (partial, complete, and booster doses) was high (84.31%). Satisfaction within each SERVQUAL dimension was highest in tangibles (96.10%), followed by responsiveness (93.25%), empathy (92.48%), assurance (92.35%), and reliability (92.32%). There was no significant difference in the overall SERVQUAL score between the health facility and community-based approaches. However, the latter slightly improved user satisfaction across three dimensions: tangibles (adjusted odds ratio, AOR = 1.52, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.21–1.90), reliability (AOR = 1.67, 95%CI = 1.42–1.96), and assurance (AOR = 1.26, 95%CI = 1.07–1.48).

During the pandemic, both health facility and community-based approaches resulted in a high satisfaction level. It is recommended that the government prioritise and optimise community-based programs and health facility-based delivery in future vaccination initiatives, especially during public health emergencies.

Keywords: community-based, COVID-19 vaccination, household survey, Indonesia, satisfaction, service delivery, service quality, SERVQUAL.

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is evolving, with many experts predicting a gradual transition from pandemic to endemic states (Biancolella et al. 2022; Are et al. 2023). Without effective treatment regimens and with the emergence of new variants and waning immunity (DeRoo et al. 2020; Are et al. 2023; Qassim et al. 2023), vaccination will remain the primary line of defence against the virus. Previous studies have shown that vaccination is effective in reducing mortality, severity, new infections, and hospitalisation rates (Yang et al. 2023). Maintaining a high level of population immunity against the virus is crucial for protecting the population and ensuring the functionality of health systems (Rodrigues and Plotkin 2020).

The Government of Indonesia (GoI) initiated the COVID-19 vaccination roll-out in January 2021, targeting 40.2 million elderly individuals, healthcare workers, and public servants in phase 1 (January–April 2021), followed by the general population eligible for vaccination in phase 2 (April 2021–March 2022). Despite initial global shortages, the GoI successfully implemented the COVID-19 vaccination program with approximately 75% of eligible individuals having received complete vaccination, and with close to 40% having received their first booster shot (Indonesia Ministry of Health 2024). Currently, the program is moving into the second booster for eligible individuals.

In February 2021, the GoI launched the Free COVID-19 Corridor Initiative (FCC) in three major tourist destinations within Bali Province (i.e. Ubud, Nusa Dua, and Sanur). The government pledged to reopen Bali Province for international travellers once vaccination coverage reached 70% overall for Bali Province and 100% for the three FCC areas. Consequently, a mass vaccination program was implemented in Bali Province to achieve these targets starting from February 2021 (Muhtarom 2021). The COVID-19 vaccination roll-out in Bali Province stands out as one of the most successful programs across Indonesia, with a coverage rate of 97.7% for complete vaccination (Indonesia COVID-19 Countermeasures Task Force 2022).

During these periods, the government implemented three service delivery mechanisms for vaccination: (1) the healthcare facility-based approach involved administering vaccination services at primary care settings, clinics, hospitals, private practices, and health offices at airports and harbours; (2) the community-based approach entailed providing vaccination services at designated posts in villages, community halls, shopping centres or other commercial areas, non-health workplaces, schools, and other public spaces; and (3) the home visit vaccination approach, or door to door outreach program aimed to reach individuals who could not access vaccination sites easily (Indonesia Ministry of Health 2021). Each of these strategies carries its own set of advantages and disadvantages, contributing to variations in satisfaction levels among vaccine recipients. Individuals obtaining vaccinations from healthcare facilities have expressed concerns about travel and waiting times. Those utilising community vaccination posts have reported issues with insufficient information regarding eligibility criteria. Many have recounted being turned away due to chronic illnesses and being instructed to return with a referral letter from a specialist (Sawitri et al. 2022).

A previous study has reported positive correlations between the satisfaction level among vaccine recipients and overall vaccination uptake (Kunno et al. 2022). User satisfaction serves as a crucial proxy for measuring service quality. User satisfaction is correlated with several important outcomes, such as patient loyalty to health service providers, which subsequently affects patient compliance with health recommendations and reduces the incidence of malpractice litigation (Naidu 2009; Xesfingi and Vozikis 2016). Measuring satisfaction levels can be accomplished through various methods. One approach is utilising the SERVQUAL (Service Quality) concept, which assesses satisfaction across five dimensions: tangible, reliability, responsiveness, assurance, and empathy (Parasuraman et al. 1985, 1988).

Despite the ongoing importance of COVID-19 vaccination, there is a notable scarcity of studies examining the satisfaction levels of vaccine recipients. Available research is confined to healthcare facilities (Piraux et al. 2022), characterised by small sample sizes (Ati et al 2022; Wijayanti et al. 2023) and reliance on online surveys rather than comprehensive household surveys (Shahzad et al. 2022; Wijayanti et al. 2023). A singular study conducted in Saudi Arabia delved into the types of vaccination services and user satisfaction levels, revealing wide variations across different vaccination services (Shahzad et al. 2022). Comparable investigations into user satisfaction based on vaccination services in Indonesia have yet to be undertaken.

This study reports findings from a large-scale household survey that explores satisfaction levels among vaccine users in Indonesia, categorised by types of vaccination services. We aim to capture community preferences for vaccination services, particularly in emergency settings. Our study provides crucial input for enhancing the overall quality of vaccination services in Indonesia. The insights gained from this study extend beyond the scope of the COVID-19 pandemic, offering valuable guidance for policy making in the provision of healthcare services during other emergency scenarios, such as natural disasters or conflicts.

Methods

Study design, settings, and sampling

The current study was part of the COVID-19 vaccination coverage survey. In 2022, we conducted a large-scale household survey to investigate COVID-19 vaccination coverage across nine districts in Bali Province, Indonesia. In this survey, we also collected data regarding user satisfaction. We followed the World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) Vaccination Coverage Cluster Survey reference manual (WHO 2018). One of the objectives of the survey was to assess satisfaction levels among vaccine recipients and to investigate factors influencing community satisfaction levels.

The study population comprised all residents aged ≥12 years in these nine districts who had received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccination. This study captured the participants’ overall satisfaction with the COVID-19 vaccination, regardless of their vaccination status (partial, complete, or booster). The inclusion criteria for the study were: (1) individuals who had resided in the selected cluster for at least 3 months; (2) those who had received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccination; (3) individuals aged ≥12 years old; and (4) those willing to be interviewed, demonstrated by signing an informed consent form. Exclusions were made for individuals who were seriously ill, had mental health disorders, or had trouble communicating.

We calculated the sample size using the Excel software provided by the WHO (WHO 2018) with the following parameters: the estimated immunisation coverage (99%); number of strata (nine districts); Delta (5%); Alpha (5%); target number of respondents per cluster (15); ICC for immunisation (0.16); average number to visit to find one eligible subject (1); and response rate (98%). Based on the calculation, we should visit 315 clusters, 16 households per cluster, resulting in 5040 households to be visited. Samples were selected using multi-stage systematic random sampling techniques (detailed in Fig. 1). Initially, 15% of all villages in each district were randomly chosen. In the second stage, a minimum of 30 clusters (i.e. sub-village level) were randomly selected from all available clusters across the chosen villages. The total number of selected clusters in each district was adjusted based on the area’s population size. Finally, 16 households were randomly selected from the lists of household heads in each cluster. A total of 12,120 recipients of COVID-19 vaccination (partial or one dose, complete or two doses, and booster or three doses) were involved in the current study.

Study instrument

Data were gathered through a structured questionnaire that delved into socio-demographic characteristics, vaccination locations, and user satisfaction (see Sawitri et al. (2022) for the full questionnaires or survey instruments). The vaccination locations served as a proxy to classify the vaccination strategies. For instance, the health facility-based approach encompassed individuals vaccinated at primary healthcare facilities, clinics, or hospitals. The community-based approach pertained to those vaccinated at public spaces, schools, government agencies, workplaces, and places of worship. The home visit or outreach approach applied to individuals receiving vaccination at their residence (see Supplementary File S2 for further description of these approaches). Sixteen statements were used to gauge user satisfaction levels, adapted from Parasuraman’s SERVQUAL approach (Parasuraman et al. 1988) and the findings of a COVID-19 vaccine service evaluation in Surabaya City (Fadhilah et al. 2021). These statements were modified to suit the context of COVID-19 vaccination services in both health facilities and communities. They encompassed four statements on tangibility (visible and physical aspects of vaccination services), four on reliability, three on responsiveness, three on assurance, and two on empathy. Respondents rated these statements on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Satisfaction levels were categorised as either satisfied or unsatisfied, with the satisfied category defined for those scoring ≥ (number of statements x 4) across all dimensions and within each SERVQUAL dimension.

Data collection procedure

Household surveys were carried out from March to July 2022. Trained enumerators, totalling 45, conducted structured interviews under the supervision of five survey coordinators. Enumerators engaged respondents in interviews, initially recording responses on paper-based questionnaires while in the field, before subsequently inputting the data into the KoboToolbox application (The Kobo Organization 2022). Enumerators double-checked for data completeness. In cases of unclear or missing data, enumerators reached out to respondents using the contact information provided in the questionnaire. Survey coordinators reviewed incoming data and verified respondents’ vaccination statuses. One data manager was responsible for managing data within the KoboToolbox ensuring completeness, accuracy, and regular backups.

Data analysis

The data stored on the KoboToolbox server were initially exported into Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Office Professional Plus 2016) format and was then transferred to Stata ver. 14 (Stata/IC 14.2 for Windows) for further analysis. Descriptive analysis was performed to describe socio-demographic characteristics of respondents and research variables. Results from this descriptive analysis were presented in the form of a single distribution table. A difference of proportions test was conducted using Chi Square to see a difference of satisfaction based on some variables. To see the correlation of independent variables to satisfaction level, the simple logistic regression was implemented to overall and each SERVQUAL dimension. All independent variables with a significance level below 0.250 were included in the multiple logistic regression to evaluate relationships of vaccination approaches and socio-demographic characteristics on user satisfaction levels. A multiple logistic regression analysis was not conducted for the responsiveness dimension because no variables were found to have significant effects on satisfaction in this dimension.

Due to the complex sampling designs (see Fig. 1), the selected samples may not represent the population, arising from issues such as unequal probabilities of selection, non-coverage of the population, and non-response. All analyses in this study were conducted using weighting factors. These weighting factors were implemented to mitigate any potential biases arising from the unequal probabilities of sample selection. The weighting factors were based on the probabilities of selection at each stage and were calculated based on the number of units for each stage of the sampling selection (i.e. villages, sub-villages, head of households, and eligible respondents) (see Supplementary File S1). Decisions were made by researchers in consultation with the WHO Indonesia guided by the United Nations Household Survey Manual (United Nations 2005).

Ethics approval

The Survey of COVID-19 Vaccination Coverage in Bali Province 2022 obtained ethical clearance (No. 537/UN14.2.2.VII.14/LT/2022) from the Ethics Commission of the Faculty of Medicine, Udayana University/RSUP Sanglah, dated 16 March 2022. Additionally, survey permission was granted by the Bali Provincial Government (No. B.30.070/719.E/IZIN-C/DPMPTSP), dated 9 March 2022 and a letter of recommendation was issued by the Bali Province COVID-19 Countermeasures Task Force (No. 540/SatgasCovid19/III/2022), dated 28 March 2022. Permission to utilise the survey data for this publication has been obtained from the World Health Organization Indonesia Country Office, the funder of the Survey of COVID-19 Vaccination Coverage in Bali Province 2022.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics

Table 1 presents a descriptive analysis of socio-demographic of respondents and the proportion difference of satisfaction levels based on socio-demographic characteristics and vaccination locations. The majority of the recipients were adults (42.03%), with a median age of 43 years (interquartile range, IQR = 26). The study identified that 16.35% of respondents belonged to the elderly population, which is considered a vulnerable group and a priority for vaccination. The gender distribution among respondents was nearly equal, with males accounting for 50.8% and females 49.2%. The majority of respondents had completed senior high school (34.88%) and worked in occupations such as farming or labour (25.35%). Geographically, over half of the respondents resided in urban villages (52.72%). Approximately half of the respondents received their COVID-19 vaccine in public spaces (46.23%), including venues such as village halls, open fields, malls, multipurpose buildings, and other public areas.

| Characteristic (N = 12,120) | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) A | Satisfied n (%) A | Unsatisfied n (%) A | P-value (Chi2) A | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group (years old) | ||||||

| Mean (s.d.)/median (IQR) | 42.45 (16.89)/43 (26) | |||||

| Adolescent (12–18) | 1306 | 10.52 | 1113 (85.49) | 193 (14.51) | <0.001 | |

| Adult (19–44) | 5071 | 42.03 | 4259 (85.40) | 812 (14.60) | ||

| Pre-elderly (45–59) | 3725 | 31.10 | 3086 (82.70) | 639 (17.30) | ||

| Elderly (≥60) | 2018 | 16.35 | 1683 (83.80) | 335 (16.20) | ||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 6181 | 50.80 | 5176 (84.45) | 1005 (15.55) | <0.001 | |

| Female | 5939 | 49.20 | 4965 (84.16) | 974 (15.84) | ||

| Education | ||||||

| Uneducated | 809 | 6.80 | 5198 (84.31) | 967 (15.69) | 0.914 | |

| Primary school | 3335 | 28.35 | ||||

| Junior high school | 2021 | 16.71 | ||||

| Senior high school | 4330 | 34.88 | 4943 (84.31) | 1012 (15.69) | ||

| Academy/university | 1625 | 13.26 | ||||

| Occupation | ||||||

| Farmer/labourer | 3140 | 25.35 | 2655 (85.36) | 485 (14.64) | <0.001 | |

| Unemployed | 2850 | 23.65 | 2353 (82.42) | 497 (17.58) | ||

| Entrepreneur | 2554 | 22.17 | 2107 (83.20) | 447 (16.80) | ||

| Private sector | 1577 | 12.82 | 1311 (85.18) | 266 (14.82) | ||

| Student | 948 | 7.61 | 811 (86.38) | 137 (13.62) | ||

| Civil servant | 453 | 3.70 | 381 (83.62) | 72 (16.38) | ||

| Housewife | 405 | 3.22 | 361 (89.32) | 44 (10.68) | ||

| Others | 193 | 1.48 | 162 (85.67) | 31 (14.33) | ||

| Location of village | ||||||

| Urban | 6605 | 52.72 | 5435 (83.24) | 1170 (16.76) | <0.001 | |

| Rural | 5515 | 47.28 | 4706 (85.50) | 809 (14.50) | ||

| District/city | ||||||

| Denpasar | 1735 | 11.33 | 1191 (70.50) | 544 (29.50) | <0.001 | |

| Badung | 1464 | 11.24 | 1168 (80.97) | 296 (19.03) | ||

| Tabanan | 1206 | 12.13 | 990 (82.25) | 216 (17.75) | ||

| Gianyar | 1557 | 12.78 | 1417 (90.74) | 140 (9.26) | ||

| Klungkung | 1246 | 5.76 | 1086 (79.11) | 160 (20.89) | ||

| Bangli | 1142 | 6.47 | 1005 (89.37) | 137 (10.63) | ||

| Karangasem | 1065 | 13.27 | 925 (88.89) | 140 (11.11) | ||

| Buleleng | 1561 | 18.94 | 1357 (86.04) | 204 (13.96) | ||

| Jembrana | 1144 | 8.08 | 1002 (89.32) | 142 (10.68) | ||

| Vaccination location | ||||||

| Primary health care B | 3960 | 32.00 | 3.266 (83.74) | 694 (16.26) | <0.001 | |

| Hospital B | 729 | 5.94 | 577 (80.87) | 152 (19.13) | ||

| Public space C | 5639 | 46.23 | 4.806 (85.17) | 833 (14.83) | ||

| School C | 1280 | 11.76 | 1.110 (87.09) | 170 (12.91) | ||

| Government agency C | 328 | 2.63 | 223 (69.01) | 105 (30.99) | ||

| Workplace C | 101 | 0.80 | 89 (89.42) | 12 (10.58) | ||

| Worship place C | 53 | 0.42 | 45 (88.92) | 8 (11.08) | ||

| Home C | 30 | 0.20 | 25 (86.19) | 5 (13.81) | ||

User satisfaction regarding COVID-19 vaccination services

Satisfaction levels based on socio-demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1. Satisfaction appears to be higher among adolescents, males, housewives, and rural residents. Satisfaction levels based on different vaccination locations are presented in Table 2. The overall satisfaction rate was 84.31%, with small variation (<3%) across the three vaccination approaches. However, it is crucial to note that the number of respondents reached through the home visit approach was very limited, comprising only 30 respondents. Satisfaction levels against the 16 statements across five SERVQUAL dimensions are presented in Table 3. Multiple areas that require further improvement included: implementation of protocols for maintaining seat distance, supervision and management of adverse events following immunisation (AEFI), providing a sense of comfort during vaccination, and a lack of attention from officers during service.

| Variable | General (N = 12,120) | Health facility-based (N = 4689) | Community-based (N = 7401) | Home visit (N = 30) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (n) | Percent (%) A | 95% CI A | Number (n) | Percent (%) A | 95% CI A | Number (n) | Percent (%) A | 95% CI A | Number (n) | Percent (%) A | 95% CI A | ||||||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | ||||||||||

| Total five SERVQUAL dimensions | |||||||||||||||||

| Satisfied | 10,141 | 84.31 | 83.49 | 85.09 | 3843 | 83.29 | 81.95 | 84.54 | 6273 | 84.93 | 83.88 | 85.92 | 25 | 86.19 | 66.80 | 95.08 | |

| Unsatisfied | 1979 | 15.69 | 14.91 | 16.51 | 846 | 16.71 | 15.46 | 18.05 | 1128 | 15.07 | 14.08 | 16.12 | 5 | 13.81 | 4.92 | 33.20 | |

| Tangible | |||||||||||||||||

| Satisfied | 11,616 | 96.10 | 95.66 | 96.49 | 4465 | 95.00 | 94.15 | 95.72 | 7125 | 96.78 | 96.28 | 97.22 | 26 | 92.18 | 79.86 | 97.23 | |

| Unsatisfied | 504 | 3.90 | 3.51 | 4.34 | 224 | 5.00 | 4.28 | 5.85 | 276 | 3.22 | 2.78 | 3.72 | 4 | 7.82 | 2.77 | 20.14 | |

| Reliability | |||||||||||||||||

| Satisfied | 11,102 | 92.32 | 91.73 | 92.88 | 4178 | 89.84 | 88.74 | 90.84 | 6896 | 93.85 | 93.16 | 94.47 | 28 | 92.74 | 70.01 | 98.59 | |

| Unsatisfied | 1018 | 7.68 | 7.13 | 8.27 | 511 | 10.16 | 9.16 | 11.26 | 505 | 6.15 | 5.53 | 6.84 | 2 | 7.26 | 1.41 | 29.99 | |

| Responsiveness | |||||||||||||||||

| Satisfied | 11,330 | 93.25 | 92.64 | 93.81 | 4367 | 93.43 | 92.47 | 94.27 | 6937 | 93.14 | 92.32 | 93.88 | 26 | 92.14 | 78.74 | 97.38 | |

| Unsatisfied | 790 | 6.75 | 6.19 | 7.37 | 322 | 6.57 | 5.73 | 7.53 | 464 | 6.86 | 6.12 | 7.68 | 4 | 7.86 | 2.62 | 21.26 | |

| Assurance | |||||||||||||||||

| Satisfied | 11,097 | 92.35 | 91.77 | 92.90 | 4220 | 91.11 | 90.11 | 92.03 | 6848 | 93.10 | 92.38 | 93.76 | 29 | 96.36 | 78.09 | 99.49 | |

| Unsatisfied | 1023 | 7.65 | 7.10 | 8.23 | 469 | 8.89 | 7.97 | 9.89 | 553 | 6.90 | 6.24 | 7.62 | 1 | 3.64 | 0.51 | 21.91 | |

| Empathy | |||||||||||||||||

| Satisfied | 11,091 | 92.48 | 91.92 | 93.01 | 4272 | 92.49 | 91.57 | 93.32 | 6790 | 92.47 | 91.73 | 93.14 | 29 | 96.36 | 78.09 | 99.49 | |

| Unsatisfied | 1029 | 7.52 | 6.99 | 8.08 | 417 | 7.51 | 6.68 | 8.43 | 611 | 7.53 | 6.86 | 8.27 | 1 | 3.64 | 0.51 | 21.91 | |

| Questionnaire Statement (N = 12,120) | Satisfied | Unsatisfied | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) A | n (%) A | ||

| Tangible | |||

| 1. The waiting room is clean and comfortable | 11,939 (98.49) | 181 (1.51) | |

| 2. Implementation of protocols for maintaining distance between seats | 11,836 (97.79) | 284 (2.21) | |

| 3. Provision of functional hand washing facilities or hand sanitiser | 11,977 (99.05) | 143 (0.95) | |

| 4. The officers wearing complete personal protective equipment (PPE) | 11,976 (98.82) | 144 (1.18) | |

| Reliability | |||

| 1. The officers in service are competent (from preparation until injection) | 12,028 (99.30) | 92 (0.70) | |

| 2. The officers serve quickly and efficiently (waiting time is not too long) | 11,861 (97.89) | 259 (2.11) | |

| 3. The officers provide the same service to everyone | 11,939 (98.62) | 181 (1.38) | |

| 4. The officers give different treatment to me compared to others | 10,990 (91.81) | 1.130 (8.19) | |

| Responsiveness | |||

| 1. The officers provide explanation about service that easily understood | 11,939 (98.63) | 181 (1.37) | |

| 2. The officers give opportunity to ask and respond quickly | 11,889 (98.23) | 231 (1.77) | |

| 3. The officers supervise and handle AEFI according to procedures | 11,584 (95.04) | 536 (4.96) | |

| Assurance | |||

| 1. The officers provide a sense of security during service | 11,893 (98.23) | 227 (1.77) | |

| 2. The officers provide a sense of comfort during service | 11,364 (94.47) | 756 (5.53) | |

| 3. The officers provide proof of vaccination (paper-based, SMS, or in-apps) | 11,459 (95.15) | 661 (4.85) | |

| Empathy | |||

| 1. The officers give full attention during service | 11,236 (93.66) | 884 (6.34) | |

| 2. The officers serve in a friendly and courteous manner | 11,901 (98.39) | 219 (1.61) | |

Effects of socio-demographic characteristics and vaccination approaches on user satisfaction

The multiple logistic regression analysis of the overall score across all five dimensions showed that no variables were found to significantly influence satisfaction (P-value > 0.05) (see Table 4). There was also no significant difference of satisfaction level and overall SERVQUAL score between health facility and community-based approaches. During the pandemic, both approaches resulted in high satisfaction rates among vaccine recipients. However, upon closer examination of each SERVQUAL dimension, respondents who received vaccinations through a community-based approach reported slightly higher satisfaction compared to those who received vaccinations through a health facility-based approach.

| Variable | Total five dimensions | Tangible | Reliability | Assurance | Empathy | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOR | P-value | 95% CI | AOR | P-value | 95% CI | AOR | P-value | 95% CI | AOR | P-value | 95% CI | AOR | P-value | 95% CI | |||||||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | ||||||||||||

| Implementation strategy | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Health facility-based | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | – | – | – | – | |

| Community-based | 1.11 | 0.115 | 0.98 | 1.25 | 1.52 | <0.001 | 1.21 | 1.90 | 1.67 | <0.001 | 1.42 | 1.96 | 1.26 | 0.006 | 1.07 | 1.48 | – | – | – | – | |

| Home visit | 1.25 | 0.710 | 0.38 | 4.11 | 0.57 | 0.317 | 0.19 | 1.72 | 1.50 | 0.651 | 0.26 | 8.76 | 2.69 | 0.332 | 0.36 | 20.01 | – | – | – | – | |

| Age group (years) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Adolescent (12–18) | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |

| Adult (19–44) | 0.94 | 0.671 | 0.72 | 1.23 | 0.72 | 0.148 | 0.46 | 1.12 | 1.01 | 0.977 | 0.70 | 1.45 | 0.86 | 0.454 | 0.59 | 1.27 | 0.75 | 0.100 | 0.54 | 1.06 | |

| Pre-elderly (45–59) | 0.76 | 0.057 | 0.57 | 1.01 | 0.66 | 0.071 | 0.43 | 1.04 | 0.85 | 0.406 | 0.58 | 1.24 | 0.62 | 0.020 | 0.42 | 0.93 | 0.66 | 0.023 | 0.46 | 0.94 | |

| Elderly (≥60) | 0.83 | 0.223 | 0.62 | 1.12 | 0.76 | 0.268 | 0.46 | 1.24 | 0.81 | 0.309 | 0.55 | 1.21 | 0.65 | 0.036 | 0.44 | 0.97 | 0.62 | 0.010 | 0.43 | 0.89 | |

| Education | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Low education | – | – | – | – | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref | Ref. | Ref. | |

| High education | – | – | – | – | 0.76 | 0.032 | 0.59 | 0.98 | 1.01 | 0.929 | 0.83 | 1.23 | 0.91 | 0.382 | 0.74 | 1.12 | 0.88 | 0.218 | 0.73 | 1.08 | |

| Occupation | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Civil servant | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | – | – | – | – | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |

| Farmer/labourer | 1.11 | 0.541 | 0.79 | 1.57 | – | – | – | – | 1.35 | 0.147 | 0.90 | 2.04 | 1.29 | 0.261 | 0.83 | 2.00 | 1.40 | 0.109 | 0.93 | 2.11 | |

| Unemployed | 0.85 | 0.368 | 0.60 | 1.21 | – | – | – | – | 1.11 | 0.605 | 0.75 | 1.64 | 0.79 | 0.285 | 0.52 | 1.21 | 1.03 | 0.892 | 0.70 | 1.52 | |

| Entrepreneur | 0.94 | 0.706 | 0.66 | 1.32 | – | – | – | – | 1.20 | 0.348 | 0.82 | 1.77 | 1.10 | 0.656 | 0.73 | 1.66 | 1.09 | 0.646 | 0.75 | 1.60 | |

| Private sector | 1.05 | 0.789 | 0.73 | 1.51 | – | – | – | – | 0.88 | 0.517 | 0.60 | 1.29 | 0.87 | 0.510 | 0.57 | 1.32 | 1.35 | 0.139 | 0.91 | 1.99 | |

| Student | 1.01 | 0.971 | 0.65 | 1.57 | – | – | – | – | 1.28 | 0.399 | 0.72 | 2.29 | 0.91 | 0.752 | 0.51 | 1.62 | 1.10 | 0.710 | 0.67 | 1.80 | |

| Housewife | 1.55 | 0.093 | 0.96 | 2.51 | – | – | – | – | 1.73 | 0.072 | 0.95 | 3.15 | 3.31 | 0.004 | 1.48 | 7.39 | 5.24 | <0.001 | 2.44 | 11.25 | |

| Others | 1.19 | 0.959 | 0.69 | 2.06 | – | – | – | – | 2.09 | 0.056 | 0.98 | 4.45 | 2.25 | 0.032 | 1.07 | 4.74 | 1.30 | 0.471 | 0.63 | 2.68 | |

All values shown are the weighted value.

Age appears to influence satisfaction levels in the assurance and empathy dimensions, with older respondents (pre-elderly and elderly) exhibiting lower satisfaction compared to those in the adolescent group within these dimensions. The statistical values support this observation: for assurance, the pre-elderly (adjusted odds ratio, AOR = 0.62, P-value = 0.020, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.42–0.93) and elderly (AOR = 0.65, P-value = 0.036, 95%CI = 0.44–0.97) age groups showed lower satisfaction, while in the empathy dimension, both the pre-elderly (AOR = 0.66, P-value = 0.023, 95%CI = 0.46–0.94) and elderly (AOR = 0.62, P-value = 0.010, 95%CI = 0.43–0.89) groups demonstrated decreased satisfaction.

Regarding education, its impact on satisfaction was observed solely in the tangible dimension. Respondents with higher levels of education were found to be 0.76 times less satisfied with vaccination services compared to those with lower levels of education (P-value = 0.032, 95%CI = 0.59–0.98).

Occupation also plays a role in influencing satisfaction levels, particularly in the assurance and empathy dimensions. Housewives and individuals with other occupations tended to express higher satisfaction compared to civil servants. Specifically, housewives (AOR = 3.31, P-value = 0.004, 95%CI = 1.48–7.39) and those with other occupations (AOR = 2.25, P-value = 0.032, 95%CI = 1.07–4.74) were more satisfied in the assurance dimension. Similarly, in the empathy dimension, housewives exhibited significantly higher satisfaction levels, being 5.24 times more satisfied with vaccination services than civil servants (P-value = <0.001, 95%CI = 2.44–11.25).

Discussion

Our study aimed to evaluate the overall satisfaction of individuals who received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccination, along with any associations to socio-demographic characteristics and vaccination services. We surveyed 12,120 respondents, ensuring comparability with the population of Bali Province in terms of gender and age distributions (Bali Province Central Bureau of Statistics 2021). Our findings indicate a high level of satisfaction among vaccine recipients in Bali Province (84.31%), with only small variation (<3%) across home visit, community-based, and health facility-based approaches. These insights illuminate community preferences and expectations regarding vaccination service delivery, especially during public health emergencies. By identifying which domains contribute most significantly to community perceptions and satisfaction, we can prioritise strategies to increase service utilisation, particularly in the context of emergency situations.

The assessment of COVID-19 vaccination service satisfaction in Indonesia is scarce and lacks conclusive results, hampering comparative analyses. A previous study in a rural village in Bali Province reported remarkably high user satisfaction (99.4%) (Ati et al. 2022). However, another nationwide online survey revealed significantly lower satisfaction rates (50.1%) (Wijayanti et al. 2023). Both studies suffered from small sample sizes and failed to differentiate between vaccination services or locations. Our study addresses these shortcomings by collecting satisfaction data from a large household survey, utilising extensive randomly selected samples, and considering satisfaction levels across vaccination approaches.

When comparing the health-facility and community-based approaches, our findings indicate there is no significant difference of the overall SERVQUAL score and satisfaction levels between the two approaches. During the pandemic, both health facility and community-based approaches resulted in high satisfaction levels. Various contextual factors contribute to the high satisfaction rate observed in our study. During emergencies like pandemics, individuals may adjust their health seeking behaviours and lower their expectations, and the vaccine is viewed as a protective measure (Zhang et al. 2023) and simply having access to vaccines can promote satisfaction. Bali Province has historically maintained high basic vaccination coverage (Indonesia Central Bureau of Statistics 2021; Indonesia Ministry of Health 2023), reflecting community trust in the health system and active participation in the immunisation program. However, amidst mass vaccination efforts and a global pandemic, many respondents were uncertain about what to expect.

Our analysis revealed that user satisfaction is influenced by age groups, education levels, and occupations. These findings align with prior research investigating the relationship between user satisfaction and socio-demographic factors such as age and gender (Lestari et al. 2022), marital status (Wijayanti et al. 2023), occupation, education, knowledge, access to health information, and access to health services (Lailasari 2022).

The availability of standardised operational procedures (SOP) (Indonesia Ministry of Health 2021) and health protocols (Indonesia Ministry of Health 2020) also contributes to enhanced satisfaction, particularly in terms of tangible aspects. However, lower satisfaction scores in reliability and assurance dimensions suggest that communities have high expectations in these areas, particularly in uncertain contexts. The heavy workload during mass vaccination services can lead to burnout among health workers, potentially affecting service quality. Inadequate training for volunteers involved in mass vaccinations could also contribute to low satisfaction in these two dimensions (Stodolska et al. 2023).

While our study found that the home visit approach garnered the highest satisfaction score, the number of individuals vaccinated through this strategy remains limited. This is due to the high cost and labour intensity associated with home visits, making it potentially impractical during emergencies when the availability of healthcare workers is strained. Our research reaffirms that satisfaction scores for the community-based approach slightly surpass those for health facility-based approaches especially in tangible, reliability, and assurance dimensions, underscoring the community’s preference for accessing vaccination closer to their residential areas. This preference holds promise during public health emergencies, as a community-based approach can reach a larger number of individuals compared to health facility or outreach approaches. Health facilities are not designed for mass vaccination programs, lacking sufficient staff and space for large-scale vaccination. Moreover, crowding situations increase the risk of mixing vulnerable, healthy, and high-risk individuals.

Other studies have highlighted the influence of vaccination locations on user satisfaction. A study in Saudi Arabia (Shahzad et al. 2022), with a sizeable sample, reported higher satisfaction scores among participants vaccinated at ‘premium centres’ (95.6%), followed by vaccination centres (91.1%), hospitals (91%), and primary health centres (89.4%). However, this study did not specifically compare satisfaction rates between health facility, community, and outreach approaches. Another study conducted in France to gauge the satisfaction level of COVID-19 vaccine recipients served by community pharmacists found exceedingly high satisfaction levels, reaching 4.92 out of a maximum of 5 points (Piraux et al. 2022). These findings underscore the significant influence of vaccination locations and community-based approach on the satisfaction levels of vaccine recipients.

Our study found a slightly higher satisfaction rate in tangible, reliability, and assurance dimensions among individuals receiving vaccinations through a community-based approach compared to a health facility-based approach which can be attributed to several factors. Community focus, the active involvement of community members, and multisectoral collaboration are crucial elements of this approach (Nilsen 2006). During emergencies, using familiar facilities located closer to individuals, coupled with health information disseminated by community leaders, can enhance participation. Providing vaccination services in familiar community settings such as community halls can also increase user satisfaction. The involvement of community leaders, police, army, and traditional security officers (pecalang) in monitoring vaccination implementation can further enhance users’ sense of security, contributing to higher satisfaction levels.

Bali Province comprises traditional and administrative village structures. The traditional sub-villages (locally called banjar adat) are associated with religious rituals and ceremonies, while administrative sub-villages (locally called banjar dinas) handle population registration matters and public services. Involving these social elements in the COVID-19 vaccination program enhances community participation user satisfaction. Similar results were observed in case studies across four countries supported by UNICEF, where community-driven initiatives like C-RCCE (Community-led Risk Communication and Community Engagement), community rapid assessments, 3iS outreach (Intensification of Integrated Immunisation), and HCD (Human-Centred Design) increased acceptance and uptake of COVID-19 vaccination and routine immunisation (Hopkins et al. 2023). This highlights the effectiveness of community collaboration in improving immunisation program coverage.

Based on our findings, it is evident that both health facility and community-based approaches lead to high satisfaction levels. In similar future scenarios, such as new pandemics, public health emergencies, or natural disaster settings, government efforts should focus on strengthening services through these approaches, addressing any remaining satisfaction dimensions while maintaining the already successful aspects.

Study limitations

In this study, satisfaction data were obtained from all participants regardless of their vaccination status (partial/first dose, complete/two-doses, and booster/three-doses). We recognise that the satisfaction and experiences of first-time vaccine recipients could be different from second-time or booster recipients. The main limitation of this study is that we do not separate the satisfaction levels between these three groups. This approach may influence the satisfaction perceptions of individuals who have had more than one dose, potentially altering their views on the initial vaccination service received. The study solely evaluated performance indicators of service providers, overlooking the expectations of vaccine recipients regarding these aspects. To enhance the accuracy of satisfaction measurements, future research should incorporate assessment of service recipients’ expectations concerning various service dimensions.

There is a significant disparity in respondent numbers among different vaccination strategies. For instance, there were 4689 respondents vaccinated through health facility-based, 7401 through community-based, and only 30 through outreach or door to door approaches. This disparity leads to a wide confidence interval in the analysis results for the outreach or door to door approach, necessitating caution when drawing conclusions in this category.

Declaration of funding

The study was a part the Survey of COVID-19 Vaccination Coverage in Bali Province 2022, funded by the World Health Organization Indonesia Country Office with PO Number 202818814-1. The authors declare that the funder had no involvement in the analysis and writing of this manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their sincere gratitude to the World Health Organization Indonesia Country Office for granting permission to publish the data from the COVID-19 Vaccination Coverage Survey. Additionally, huge thanks are extended to all members of the survey team, the Bali Provincial Health Office, all District/City Health Offices in Bali Province, selected community health centres, schools, village heads, and head of Banjar Dinas (sub-village) for their invaluable assistance in implementing and facilitating the survey activities.

References

Are EB, Song Y, Stockdale JE, Tupper P, Colijn C (2023) COVID-19 endgame: from pandemic to endemic? Vaccination, reopening and evolution in low- and high-vaccinated populations. Journal of Theoretical Biology 559, 111368.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ati NWJ, Suyasa IGPD, Mastryagung GAD (2022) Level of community satisfaction with COVID-19 vaccine services in Belantih Village, Kintamani District. Jurnal Medika Usada 5(2), 34-41 Available at https://ejournal.stikesadvaitamedika.ac.id/index.php/MedikaUsada/article/view/134.

| Google Scholar |

Bali Province Central Bureau of Statistics (2021) Official statistics news: results of the 2020 population census for Bali Province. Available at https://bali.bps.go.id/pressrelease/2021/01/21/717592/hasil-sensus-penduduk-2020-provinsi-bali.html

Biancolella M, Colona VL, Mehrian-Shai R, Watt JL, Luzzatto L, Novelli G, Reichardt JKV (2022) COVID-19 2022 update: transition of the pandemic to the endemic phase. Human Genomics 16, 19.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

DeRoo SS, Pudalov NJ, Fu LY (2020) Planning for a COVID-19 vaccination program. JAMA 323(24), 2458-2459.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Fadhilah MU, Fauziyah U, Cahyani AA, Arif L (2021) Evaluation of COVID-19 vaccination services (case study of Mojo Public Health Center, Surabaya City). Journal Publicuho 4(2), 536-552.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hopkins KL, Underwood T, Iddrisu I, Woldemeskel H, Bon HB, Brouwers S, Almedia SD, Fol N, Malhotra A, Prasad S, Bharadwaj S, Bhatnagar A, Knobler S, Lihemo G (2023) Community-based approaches to increase COVID-19 vaccine uptake and demand: lessons learned from four UNICEF-supported interventions. Vaccines 11, 1180.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Indonesia Central Bureau of Statistics (2021) Health statistic profile 2021. Available at https://www.bps.go.id/id/publication/2021/12/22/0f207323902633342a1f6b01/profil-statistik-kesehatan-2021.html

Indonesia COVID-19 Countermeasures Task Force (2022) COVID-19 situation by province: Bali. Available at https://covid19.go.id/situasi/

Indonesia Ministry of Health (2020) Decree of the Minister of Health of the Republic of Indonesia Number HK0107/MENKES/382/2020 concerning Health Protocols for Communities in Public Places and Facilities in the Framework of Prevention and Control of Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Available at http://hukor.kemkes.go.id/uploads/produk_hukum/KMK_No__HK_01_07-MENKES-382-2020_ttg_Protokol_Kesehatan_Bagi_Masyarakat_di_Tempat_dan_Fasilitas_Umum_Dalam_Rangka_Pencegahan_COVID-19.pdf

Indonesia Ministry of Health (2021) Decree of the Minister of Health of the Republic of Indonesia Number HK0107/MENKES/4638/2021 concerning Technical Instructions for Implementing Vaccination in the Context of Overcoming the Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic. Available at https://farmalkes.kemkes.go.id/?wpdmpro=kmk-no-hk-01-07-menkes-4638-2021-ttg-juknis-pelaksanaan-vaksinasi-dalam-rangka-penanggulangan-pandemi-covid-19

Indonesia Ministry of Health (2023) Indonesia health profile 2022. Available at https://p2p.kemkes.go.id/profil-kesehatan-2022/

Indonesia Ministry of Health (2024) National COVID-19 vaccination. Available at https://vaksin.kemkes.go.id/#/vaccines

Kunno J, Supawattanabodee B, Sumanasrethakul C, Kaewchandee C, Wanichnopparat W, Prasittichok K (2022) The relationship between attitudes and satisfaction concerning the COVID-19 vaccine and vaccine boosters in Urban Bangkok, Thailand: a cross-sectional study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19(9), 5086.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Lailasari A (2022) Analysis of satisfaction with services providing COVID-19 vaccination to the community at the Swasti Saba Public Health Center, Lubuklinggau City in 2022. Master thesis, STIKES Bina Husada Palembang. STIKES Bina Husada Repository. Available at http://rama.binahusada.ac.id:81/id/eprint/860/1/Ayu%20Lailasari.pdf

Lestari DA, Priyatno AD, Harokan A (2022) Analysis of Satisfaction COVID-19 vaccination services in the community in Jakabaring Palembang City OPI Health Center in 2022. Health Care: Jurnal Kesehatan 11(2), 246-257.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Muhtarom I (2021) Covid-19 vaccination reaches 70 percent, Is Bali ready to welcome tourists? Tempo. Available at https://travel.tempo.co/read/1476050/vaksinasi-covid-19-capai-70-persen-bali-siap-sambut-wisatawan/

Naidu A (2009) Factors affecting patient satisfaction and healthcare quality. International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance 22(4), 366-381.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Nilsen P (2006) The theory of community based health and safety programs: a critical examination. Injury Prevention 12, 140-145.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Parasuraman AP, Zeithaml VA, Berry LL (1985) A conceptual model of service quality and its implications for future research. Journal of Marketing 49(4), 41-50.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Parasuraman AP, Zeithaml VA, Berry LL (1988) SERVQUAL: a multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality. Journal of Retailing 64(1), 12-40.

| Google Scholar |

Piraux A, Cavillon M, Ramond-Roquin A, Faure S (2022) Assessment of satisfaction with pharmacist-administered COVID-19 vaccinations in France: PharmaCoVax. Vaccines 10(3), 440.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Qassim SH, Chemaitelly H, Ayoub HH, Coyle P, Tang P, Yassine HM, Al Thani AA, Al-Khatib HA, Hasan MR, Al-Kanaani Z, Al-Kuwari E, Jeremijenko A, Kaleeckal AH, Latif AN, Shaik RM, Abdul-Rahim HF, Nasrallah GK, Al-Kuwari MG, Butt AA, Al-Romaihi HE, Al-Thani MH, Al-Khal A, Bertollini R, Abu-Raddad LJ (2023) Population immunity of natural infection, primary-series vaccination, and booster vaccination in Qatar during the COVID-19 pandemic: an observational study. eClinicalMedicine 62, 102102.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Rodrigues CMC, Plotkin SA (2020) Impact of vaccines; health, economic and social perspectives. Frontiers in Microbiology 11, 1526.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Sawitri AAS, Yuliyatni PCD, Ariawan IMD, Sutarsa IN, Widyanthini DN, Dewi AAIS, Cempaka PPAR, Pradnyadewi AAAD, Karya IKJD, Pramandani NLMS, Janadewi IGA, Dewi KRA (2022) Survey of COVID-19 vaccination coverage in Bali Province. Available at https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/searo/indonesia/non-who-publications/2022-bali-coverage-survey-covid-19-vaccination.pdf?sfvrsn=b269fbde_6&download=true

Shahzad MW, Al-Shabaan A, Mattar A, Salameh B, Alturaiki EM, AlQarni WA, AlHarbi KA, Alhumaidany TM (2022) Public satisfaction with COVID-19 vaccination program in Saudi Arabia. Patient Experience Journal 9(3), 154-163.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Stodolska A, Wojcik G, Baranska I, Kijowska V, Szczerbinska K (2023) Prevalence of burnout among healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic and associated factors – a scoping review. International Journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health 36(1), 21-58.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

The Kobo Organization (2022) The KoboToolbox software. Available at https://www.kobotoolbox.org/about-us/software/

United Nations (2005) ‘Designing household survey samples: practical guidelines. Studies in Methods Series F No 98.’ (Department of Economics and Social Affairs, Statistic Division: New York) Available at https://unstats.un.org/unsd/demographic/sources/surveys/handbook23june05.pdf

Wijayanti SPM, Rejeki DSS, Rizqi YNK, Octaviana D, Nurlaela S (2023) Assessing the user satisfaction on COVID-19 vaccination service in Indonesia. Journal of Public Health Research 12(2), 1-10.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

WHO (2018) World Health Organization vaccination coverage cluster surveys: reference manual. Geneva, Switzerland. Available at http://apps.who.int/bookorders

Xesfingi S, Vozikis A (2016) Patient satisfaction with the healthcare system: assessing the impact of socio-economic and healthcare provision factors. BMC Health Services Research 16, 94.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Yang Z-R, Jiang Y-W, Li F-X, Liu D, Lin T-F, Zhao Z-Y, Wei C, Jin Q-Y, Li X-M, Jia Y-X, Zhu F-C, Yang Z-Y, Sha F, Feng Z-J, Tang J-L (2023) Efficacy of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines and the dose–response relationship with three major antibodies: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. The Lancet Microbe 4(4), e236-e246.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Zhang J-J, Dong X, Liu G-H, Gao Y-D (2023) Risk and protective factors for COVID-19 morbidity, severity, and mortality. Clinical Reviews in Allergy & Immunology 64, 90-107.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |