How to undertake research with refugees: lessons learned from a qualitative health research programme in Southern New Zealand

Molly George A * , Lauralie Richard B , Chrystal Jaye B , Sarah Derrett B , Emma Wyeth C and Tim Stokes BA

B

C

Abstract

Refugee health is an issue of global importance. Refugees have high and complex mental, physical and social needs and poor health outcomes. There is a clear need for more research prioritising refugees’ perspectives of health care in their settlement countries; however, a number of methodological and ethical challenges can make this process difficult.

This methodological paper is an analysis of our recent experience conducting qualitative research with former refugees in Southern New Zealand. We utilized our research team’s discussions, reflections and fieldnotes and the relevant literature to identify the key processes of our successful engagement with former refugees.

Successful engagement with former refugees in qualitative health research entails: establishing relationships, recognising interpreters as cultural brokers, having a responsive suite of methods and finding meaningful ways to communicate.

This paper offers suggestions and guidance on conducting qualitative health research with former refugees.

Keywords: healthcare perspectives, methodological challenges, New Zealand, qualitative health research, refugees, research with refugees.

Introduction

Refugee health is an issue of global importance with significant implications for health systems and the health outcomes of refugees. Refugees often face significant and complex mental, physical and social health challenges (Hadgkiss and Renzaho 2014) and are often more likely to have increased morbidity, poor health outcomes and a reduced life expectancy compared to host country populations (Williams and Thompson 2011; Hadgkiss and Renzaho 2014; Chen et al. 2015; WHO 2022). Coming from countries in situations of long-term war or conflict, refugees have often experienced severe trauma which is commonly associated with cumulative vulnerability including deprivation, unhealthy environmental conditions and disrupted access to health care (Williams and Thompson 2011; Smith and Daynes 2016). They then face considerable barriers in accessing healthcare services and navigating through health systems in their host countries (Cheng et al. 2015; Mangrio and Sjögren Forss 2017), frequently experiencing gaps in access, poor coordination and service fragmentation (Joshi et al. 2013; Suphanchaimat et al. 2015; Phillips et al. 2017). The fit between health services and the needs of refugees is known to be challenging, and models of care for refugees remain poorly understood and researched (Joshi et al. 2013). Ultimately refugees can experience a decline in health status after arrival, even in resource-rich nations (Gabriel et al. 2017).

Clearly there is a pressing need to consider refugees’ experiences of health care to enhance the quality of care delivered, improve access and improve refugee health outcomes. However, engaging refugees in health research is known to be practically and methodologically challenging (Gabriel et al. 2017) and evidence on how to foster culturally appropriate research practice in this context remains scant. Much of the research about refugee health care focuses on health provider perspectives (Richard et al. 2019; Kennedy et al. 2021). A comparatively smaller body of research prioritises refugees’ perspectives (including other projects within Aotearoa New Zealand (Cassim et al. 2022; Coppens 2024) and others which have co-designed services and programmes (Power et al. 2022; McKeon et al. 2024)). This article adds to this smaller body of research prioritising former refugees’ perspectives and its novel contribution is the focus on reporting key lessons learned about the process of conducting such research.

This paper reports on our experience conducting several qualitative research projects over 4 years with former refugees in Southern New Zealand. Its aim is to reflect upon the methodological particularities of qualitative research with former refugees and to identify key processes of successful engagement – with the hope of guiding others who wish to undertake more research in this area of significant importance.

Methods

The primary study within which this methodological paper is nested, aimed to explore former refugees’ engagement with, access to and navigation through New Zealand’s healthcare system across two resettlement sites in Southern New Zealand. This qualitative exploratory research relied on a community-engaged approach. Service providers helped us develop research and interview questions and facilitated contacting former refugee communities with invitations to participate. The first author (MG) conducted 20 open-ended interviews with 31 former refugees in their homes. Participants came from four countries (Syria, Afghanistan, Colombia and Iran) and spoke three languages (Arabic, Farsi and Spanish). Interviews were always supported by an interpreter and lasted ~2 h. All interviews but one were audio-recorded and MG also recorded fieldnotes in spoken and written form after each interview. The interviews and fieldnotes were transcribed prior to thematic analysis (Miles et al. 2013). All research team members reviewed and discussed the transcripts; MG coded them with ATLAS.ti software. We brought early, anonymised findings back to our community partners (service providers working with refugees) and to two of the participating households for verification and feedback.

For the purposes of this methodological paper, we utilised our research team’s discussions of the process of community engagement that preceded fieldwork and the fieldwork experience itself. The fieldworker is a social anthropologist and practiced the continuous reflexivity that is good practice in her discipline by considering her own world view and assumptions and how aspects of her identity impacted upon the fieldwork and analysis. She took copious fieldnotes after each interview. The research team met regularly to review and discuss the process, the fieldnotes, the interview transcripts and the relevant literature. They reflected upon the specific particularities encountered in conducting this research. In this paper, we provide illustrative vignettes to elucidate some of these particularities and to offer guidance about conducting qualitative health research with former refugees. All names are pseudonyms, countries of origin are not listed to maintain anonymity and other identifying characteristics have been changed.

Results

We found that successfully engaging with former refugees in qualitative health research entails the following processes: establishing relationships, recognizing interpreters as cultural brokers, having available a responsive ‘suite’ of methods and finding meaningful ways to communicate. As shown through our vignettes, these categories are not discreet but inherently interwoven.

Establishing relationships

Establishing relationships with community partners working directly with former refugees is essential. And it takes time. The Principal Investigator for this project, LR, spent years fostering connections with those who work directly with former refugees in New Zealand’s southern districts – for example, those working in government, health care (both clinical and non-clinical), non-profits (such as Red Cross and English Language Partners), community members and more. Over time and reflecting increasing trust, these community partners shared knowledge about refugees and support processes as well as insights about how research could be useful. These community partners also shared their networks and resources with our research team. Without our community partners’ expertise and resources, successful and meaningful research with refugees would not have been possible. For example, our community partners helped us recruit refugee participants (providing names and contacts and ‘vouching’ for us) and helped us formulate our interview questions (suggesting that we add questions about women’s health and nutrition, for instance). They also gave us deceptively simple advice that turned out to be critical – ‘tips and tricks’ only known to those working closely within refugee communities. The following is an excerpt from fieldnotes prior to beginning fieldwork:

Only through our community partners did we learn that we should NOT use a Colombian interpreter when working with Colombian refugees. Similarly, we heard, it is best to use an Iranian interpreter who is not intimately involved in the Afghan community, rather than an Afghan interpreter when working with Afghan refugees. We might have assumed the opposite – that using interpreters from the same nationality or community would create emotional safety. (MG, fieldnotes)

Furthermore, community partners gifted us specific recommendations for the limited number of interpreters known to possess both technical skill and the right amount of social difference/distance; those who were highly trusted by former refugees themselves. MG met and got to know these recommended interpreters prior to starting interviews. The importance of taking time to build these relationships cannot be overstated. Had we unknowingly used the ‘wrong’ interpreters, our data collection would have been severely limited and, worse, could have created an unsafe, stressful and upsetting environment for our participants.

Building rapport with participants: interpreters as cultural brokers (researcher as ‘odd one out’)

From the beginning of the first interview with former refugees, the interpreters played a crucial role in MG’s attempts to build rapport with participants. The following is an excerpt from MG’s fieldnotes following the first interview. This interviewee was Abdul, a middle-aged man who had been in New Zealand for about a year.

I entered Abdul’s home with Zahra (our interpreter). It was a sunny afternoon and I brought a small plate of food to share with his family. After some introductions and explaining the research project, I asked if I could record the conversation, noting it was not essential. Abdul said it was OK, however, Zahra then spoke extensively directly to Abdul, while I waited in ignorance. I noted a change in Abdul’s demeanour. Zahra then turned to me and simply said, ‘Ok, go ahead now.’ In that moment, I took her guidance without question. Only in the car, after the interview, did I ask what had happened. Zahra explained that she saw a look on Abdul’s face that she recognized: although he said he was OK with being recorded, he was not OK with it and would likely severely edit what he said. In that moment, Zahra decided to tell Abdul that she had been working in and around research for a number of years in New Zealand and that she felt Abdul could trust the process. I would have taken Abdul’s initial consent to being recorded as valid and would not have questioned it further. Zahra, being more familiar with Abdul’s culture and past experiences, knew more explanation and reassurance was needed. This likely vastly improved the quality of the interview as well as Abdul’s comfort.

Showing the importance of the relationship between interpreter and participant, MG noted that personal relationships seemed to form between interpreter and participant during some interviews. They, after all, are the ones who shared a language, some cultural background and often a shared story of migration. Again, an excerpt from MG’s fieldnotes:

During interviews, I often feel like the ‘odd one out.’ It’s the interpreter and the participant that have some shared understandings, experiences and language. For example, participants almost always offer food from their homelands during our meetings in their homes. Today, on being offered some Persian flatbread in Samira’s home, Zahra exclaimed in pure joy! They talked about where to buy ingredients locally and shared a heartfelt chat about missing certain foods. Eventually we got back to my research questions – which seemed so dry compared to the animated conversation the interpreter and participant were having.

On one other occasion, the interpreter and a participant enjoyed meeting each other so much that they exchanged personal numbers at the end of the interview. The power of the interpreter–participant relationship was further illustrated when a couple, Gabriela and Andre, described how disruptive it was to have inconsistent interpreters at counselling appointments. Andre was ‘extremely uncomfortable’ with inconsistent interpreters, but persevered. On the other hand, Gabriela explained that at her first counselling session she ‘asked the counsellor if the same interpreter would be present at each appointment. The counsellor replied this could not be guaranteed…’ Gabriela then walked out. Research interviews are of course different from counselling sessions but sometimes deeply personal topics are discussed and the relationship between all three – researcher, interpreter and participant – must be respected and maintained.

The interpreter’s role of cultural bridging went beyond the context of the interviews because MG often offered to help a participant with a small problem or query, which typically required some follow-up communication – necessarily involving the interpreter. On one occasion, MG texted a participant, Hassan, after getting some further information about a medical bill he did not understand. Zahra, the interpreter, translated the text into Farsi and separately told MG that she had also ‘culture-fied’ it. Zahra knew that something in MG’s message would have been lost – or worse, could have been offensive – if just literally translated. Zahra embodied an essential bridge between MG’s intended message and Hassan’s cultural context.

This is not to say that rapport is 100% reliant on interpreters as cultural brokers. In spite of not sharing a language or culture with the participants, MG also found she could build rapport and relate on the basis of some common ground. For example, MG is an immigrant, originally from the United States. There was some shared knowledge between MG and participants about complexities of resident visas, using technology to stay in close touch with relatives far away or sharing a laugh about how early everything closes in NZ compared to so many places overseas. MG is also a mother and realised the sharing pictures of one’s children is nearly a universal experience with no translation needed. In this sense, it is important to note that we found, and believe, that being willing to share some of yourself during interviews is not only essential to building rapport but is often the ethically appropriate thing to do when asking others to share deeply of themselves.

Responsive methods

We found we needed to be prepared with a flexible ‘suite’ of methods before beginning fieldwork in order to safeguard the cultural and emotional safety of former refugee participants when sharing information, gaining consent and deciding whether or not to record. For a fieldworker, this means being comfortable with ‘thinking on one’s feet’ in each interview, rather than having a set plan. For example, as mentioned above, some refugees found recording an interview to be confrontational or unacceptable; others found recording acceptable. Several former refugees in our study, particularly women, did not read or write in their own language, let alone in English. Having well-translated information sheets and consent forms is just the beginning; MG also asked each participant if he/she would like the information and consent read aloud to them. Gaining signatures on consent forms is also a sensitive matter for those who may have good reasons not to trust paperwork or bureaucracy or for those unable to read. Below is an excerpt from MG’s field notes:

Thanks to Zahra’s ‘lesson’ after the first interview with Abdul about how some participants might distrust being recorded and might really edit or alter what they say [described above], I was more informed and prepared for this at today’s interview. When I asked Hassan if I could record the interview, he replied, succinctly, ‘No.’ His wife added, ‘We have been told too many lies.’ I was ready for this, quickly agreed to not record, and asked if I could take notes instead. Hassan and his wife were also reluctant to sign anything so I readily accepted verbal consent.

A safe and comfortable meeting environment was also important. Participants were able to choose the meeting time and place. All chose their own homes, which might give an added sense of control over their experience. (However, for others, this might be too intimate and allowing another location of their choosing would be important.) When interviewing in participants’ homes, family life continued. MG was ready to pause for the interruption of a neighbour stopping by, and to integrate that neighbour into the conversation for a few minutes. MG happily accepted participants’ phones ringing, spouses joining interviews or children coming home from school. Rather than a weakness, this atmosphere proved to be a strength, ensuring the comfort of participants, and also led to sharing of some additional information. The following excerpt from MG’s fieldnotes shows a particularly poignant moment that occurred after the recorder was turned off and the participant’s children arrived home from school:

Each child kissed their mum’s face and her hands. I commented that the children and their warmth toward her was beautiful. Amina then spoke quietly, describing a history of domestic violence. She explained that her children knew of the sacrifices and hard times their mother had been through and were very dedicated to her. Their warmth and devotion to each other was palpable. Amina encouraged me to foster this love and devotion with my own kids. Though we had spoken for over an hour about health and well-being, this history of abuse had not been mentioned. Only when the children came home from school and broke the ice of a more formal-feeling interview, was this intimate aspect of her well-being revealed.

Another example of impromptu flexibility during the interview usually happened when we broached the topic of ‘women’s health’. MG would begin first by asking if it was OK to ask about women’s health. If the answer was no, she moved on. If the answer was yes, often (but not always) any men in the room would excuse themselves. A fieldworker cannot be glued to a particular interview protocol but must be responsive to the participants.

Find meaningful ways of communicating

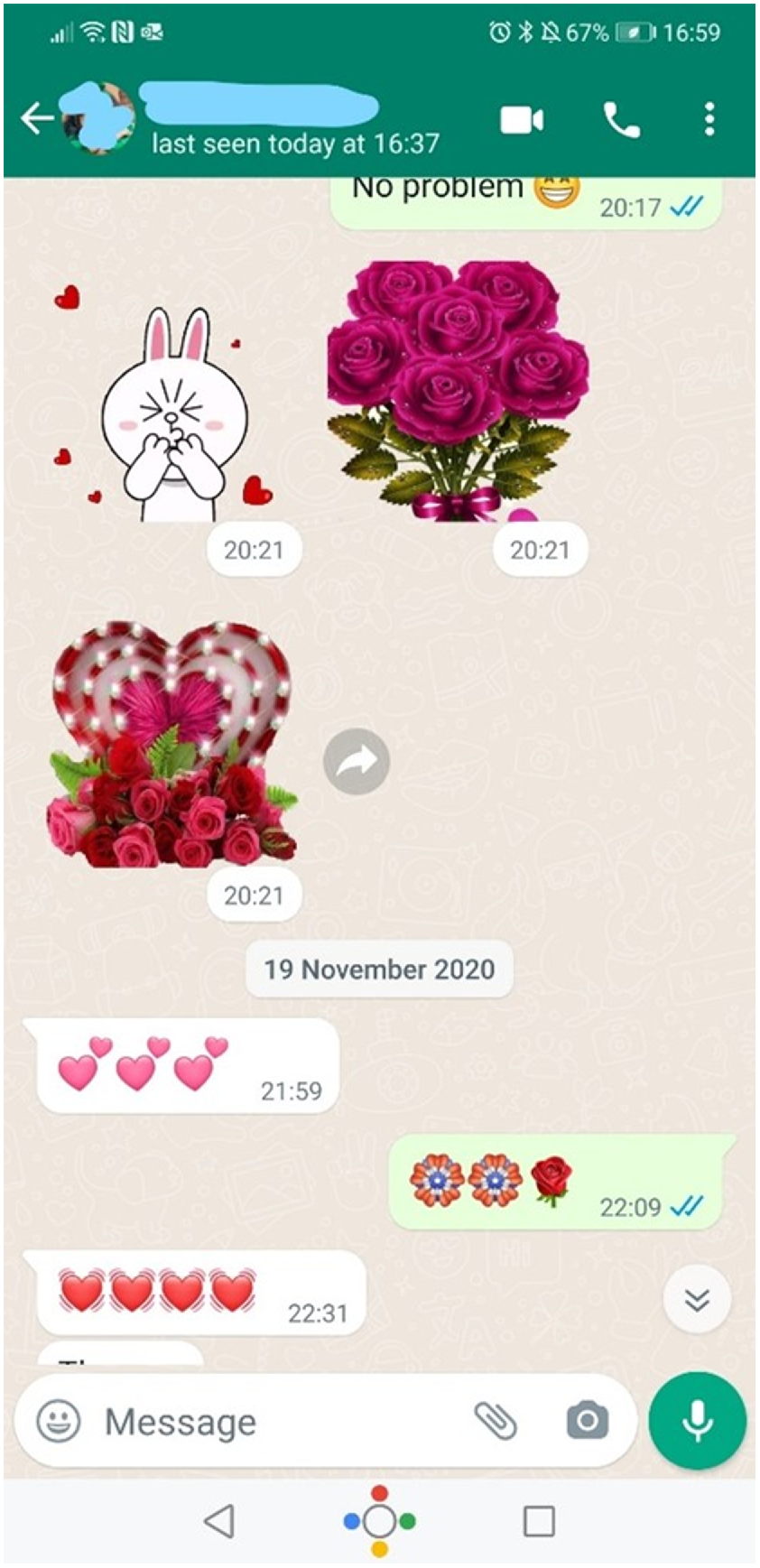

We found it was important to be able and willing to communicate in a variety of ways – in person, by phone, via WhatsApp and by other social media – adjusting to whatever means of communication the participant used and effectively creating a ‘customised communications’ approach with each participant. For example, often living on tight budgets, some former refugees did not have credit on their mobile phones but used a WiFi connection and WhatsApp to communicate by text, voice messages or video.

All interviews included heavy reliance upon an interpreter. But outside of the formal interview, language needs varied. For those who spoke some limited English, but did not read, MG could voice-record or text simple messages. But for more complex messages and to allow participants to communicate in their own language, the process was this: MG would text the interpreter what she would like to say to the participant. The interpreter would translate this into either a text message or, for the illiterate participants, a voice message. The participant could then respond – in written or voice messages, in their language. The interpreter would translate to English for MG.

This may sound laborious at best, or even a barrier to communication and research participation at worst. But with a bit of trial and error and persistence, it worked. If the interpreter and participant were comfortable with their contact information being known to each other, a group chat would be established which made it more streamlined. Furthermore, as MG found out, warm, direct communication was possible with participants even without a common language or literacy – through emojis. Fig. 1 provides a screenshot of MG’s phone of exchanges with a participant who did not read or write in her own language or in English.

Screenshot of messages with a participant who does not read or write in her own language or in English. (When actual information needed to be conveyed an interpreter facilitated.).

The success of our careful approach became evident at the end of this research project when we approached several participants to be part of our next project. All but one agreed. As former refugees can be ‘hard-to-reach’ participants, this sort of successful engagement is a crucial step in mitigating the health inequities they face.

Discussion

The health inequities of and complexities for refugees and former refugees makes health research with this population imperative. Yet research with refugees can involve ‘some of the most difficult ethical and methodological challenges in the field of human research’ and the principles that should guide the researcher are less clear (Sieber 2009). There are ethical complexities associated with marginalised populations – such as past and present trauma and the inability to exercise a degree political/social/economic agency without being at the mercy of others (Mackenzie et al. 2007). Institutional ethics committees are often more specialized towards quantitative biomedical research and may have less understanding of the subtleties and complexities inherent in qualitative social science research (Mackenzie et al. 2007). However, the importance of ethical research – to address the needs and inequities of any marginalised population – is obvious, and so the discussion must continue. We offer here our experience and, upon deep analysis and reflection, our ‘lessons learned.’ The careful, unrushed steps we took and would recommend when conducting health research with refugees are: establishing relationships (this takes time), recognising interpreters as cultural brokers, having a flexible ‘suite’ of approaches for quick customisation and finding meaningful ways of communicating.

Our research team members established relationships with many in the greater refugee community over a period of months and years before beginning this research – service providers, volunteers, health professionals and more. Sometimes these community members are referred to as ‘gatekeepers’ of the refugee population who hold important background knowledge and information, helping the researcher grow necessary understanding and skills needed to work with marginalised populations (Mackenzie et al. 2007; Sieber 2009; Kabranian-Melkonian 2015). In our experience, a particularly important step was locating and forming connections with trusted interpreters. All of this is done before any fieldwork takes place. Building these relationships can be extremely time-consuming and tricky for some researchers to balance with funding and institutional requirements, however, we found this approach was imperative.

Interestingly, while these community members could help build bridges into the refugee community, when meeting with refugees it was also sometimes necessary to differentiate ourselves from these ‘gatekeepers’. In some cases, for example, a former refugee might have had mixed experiences and therefore mixed feelings about an organisation, so identifying ourselves as independent researchers (who would keep confidentiality) was then important. At other times, former refugees would think or hope that we researchers had power or connections that could help them, and explaining our role and limitations was also an important part of the consent process (see also: Mackenzie’s et al. (2007) discussion of honest declaration of researcher’s role and limited power).

Interpreters are active in the production of research – they may bring a complex mix of power based on ethnicity, class, race and gender (Temple and Edwards 2002; Jacobsen and Landau 2003; Mackenzie et al. 2007). When MG first contacted potential participants (typically by phone) the interpreter who helped with that phone call was typically the one who would be attending the interview as well. We were therefore able to tell the potential participant, in advance, who the interpreter would be. In small communities, like the ones where we were working, this was an important aspect of trust, confidentiality and emotional safety of the participants. Sometimes the interpreter was already known to the participant (who could then consent to participate, or not, knowing who the interpreter would be). Where the interpreter was not known, MG and the interpreter gave some identifying characteristics of the interpreter – for example, letting the Colombian participants know that the interpreter was NOT Colombian. Other researchers found, like we did, that using the ‘wrong’ interpreter could come in many forms – including in many cases using one from THE SAME community as the refugee (Jacobsen and Landau 2003; Kabranian-Melkonian 2015). Gabriel et al. (2017) wrote about how the right choice of interpreters is tricky because sometimes ‘outsider’ interpreters were met with some suspicion, but more often ‘insider’ interpreters – from the same community as the participant – caused the most hesitation due to confidentiality concerns or political backgrounds. Having the appropriate interpreter is paramount and is the kind of nuanced knowledge that can only come to relationship building before fieldwork begins.

Gabriel et al. (2017) found that having a time and place of familiarity, convenience plus childcare arrangements, made refugee participants much more likely to participate in research. MG always allowed the interviewee to choose a time and place of convenience for an interview and all participants chose their own homes. This had the added benefit, then, of the participant not having to find transportation or childcare. Allowing family life to continue is more than a matter of convenience and comfort for the participant, as important as these might be. MG has extensive experience conducting qualitative interviews in participants’ homes and has come to advocate for this as appropriate and respectful practice where appropriate. Embracing interruptions, family members or friends coming and going, sharing food or meeting the family pets, means it can be difficult to quantify numbers or demographic details of participants. We argue for embracing this ambiguity as lived reality; the significant strength of this approach lies in the detailed, personal accounts that emerge – and are witnessed – by ‘being there’ in someone’s home and ongoing life (George et al. 2021). This seemingly incidental ‘being there’ is an indispensable technique in achieving an ethical, flexible, humanistic approach as well as gaining nuanced data (Monaghan and Just 2000; Madden 2010).

However, it means that the fieldworker must be flexible, compassionate, mature and humble, ready to think on her feet rather than relying on a rigid protocol. The fieldworker must also continuously report back to the broader team about the unique set of circumstances of each interview and choices made. This respectful approach extends to following the lead of participants in matters such as being recorded or signing consent forms. Several researchers have found ‘signing a form’ to be particularly tricky for refugee populations – many of whom may be illiterate or concerned about signing forms, even feeling it is dangerous to do so (Kabranian-Melkonian 2015). This can be tricky for ethics approval processes which may prefer a more blanket, standardised approach (Mackenzie et al. 2007). Ensuring the safety of all participants, especially when dealing with vulnerable populations with complex lives, however, requires a methodological approach and a fieldworker capable of customised responsiveness to each participant.

The theme of flexibility and adaptability extends to communication outside the official interview – before and/or after it. People communicate in a variety of ways for a variety of reasons, and especially when the researcher and participant do not speak the same language, a variety of methods might be needed. We found no literature specifically discussing the use of emojis and stickers with former refugees, but in our case, we found this was not just a matter of enabling communication in a perfunctory sense, but also about making connections and finding shared meaning.

This study has limitations. This paper discusses a number of strategies that we found to be successful in engaging former refugees in qualitative health research, but we note that much more would be required to constitute a co-design approach (Moll et al. 2020; Power et al. 2022; McKeon et al. 2024). Furthermore, it is a small, qualitative study with 20 former refugee families in two of New Zealand’s smaller resettlement cities. Their experiences, and the experience of doing research with them, may differ for those in larger locales with more diversity and resources (though with potentially different challenges.) It is also a broad-level look at the experience of conducting research with former refugees who are not a homogenous group but our sample size and scope does not allow for differentiation by participant ethnicities, ages, genders, etc. Our discussion above also assumes the researcher does not share the same language and cultural background as the participants. It also was conducted with former refugees who have officially been resettled, rather than those still in transition.

Conclusion

More research that prioritises the voices of former refugees themselves is needed – doing so requires time and great care. Our hope is that our analysis of our own experience enables other qualitative health researchers to engage ethically and successfully with former refugees so that, together, we can contribute to the mitigation of inequities and improve health outcomes.

Data availability

The data that support this study cannot be publicly shared due to ethical or privacy reasons and may be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author if appropriate.

Declaration of funding

This research received funding from the University of Otago Research Grant (UORG), 2019 and 2020.

Acknowledgements

We thank our participants, our interpreters and our community partners. We acknowledge the knowledge, ideas and methods from the work of others that we have called upon and utilised here to strengthen our methodological reflections.

References

Cassim S, Ali M, Kidd J, Keenan R, Begum F, Jamil D, Abdul Hamid N, Lawrenson R (2022) The experiences of refugee Muslim women in the Aotearoa New Zealand healthcare system. Kōtuitui 17, 75-89.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Chen YY, Li AT, Fung KP, Wong JP (2015) Improving access to mental health services for racialized immigrants, refugees, and non-status people living with HIV/AIDS. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 26, 505-518.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Cheng IH, Drillich A, Schattner P (2015) Refugee experiences of general practice in countries of resettlement: a literature review. British Journal of General Practice 65, e171-e176.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Gabriel P, Kaczorowski J, Berry N (2017) Recruitment of refugees for health research: a qualitative study to add refugees’ perspectives. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 14, 125.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

George M, Richards R, Watson B, Lucas A, Fitzgerald R, Taylor R, Galland B (2021) Pacific families navigating responsiveness and children’s sleep in Aotearoa New Zealand. Sleep Medicine: X 3, 100039.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Hadgkiss EJ, Renzaho AMN (2014) The physical health status, service utilisation and barriers to accessing care for asylum seekers residing in the community: a systematic review of the literature. Australian Health Review 38, 142-159.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Jacobsen K, Landau LB (2003) The dual imperative in refugee research: some methodological and ethical considerations in social science research on forced migration. Disasters 27, 185-206.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Joshi C, Russell G, Cheng IH, Kay M, Pottie K, Alston M, Smith M, Chan B, Vasi S, Lo W, Wahidi SS, Harris MF (2013) A narrative synthesis of the impact of primary health care delivery models for refugees in resettlement countries on access, quality and coordination. International Journal for Equity in Health 12, 88.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Kabranian-Melkonian S (2015) Ethical concerns with refugee research. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment 25, 714-722.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Kennedy J, Kim H, Moran S, Mckinlay E (2021) Qualitative experiences of primary health care and social care professionals with refugee-like migrants and former quota refugees in New Zealand. Australian Journal of Primary Health 27(5), 391-396.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Mackenzie C, Mcdowell C, Pittaway E (2007) Beyond ‘Do No Harm’: the challenge of constructing ethical relationships in refugee research. Journal of Refugee Studies 20, 299-319.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Mangrio E, Sjögren Forss K (2017) Refugees’ experiences of healthcare in the host country: a scoping review. BMC Health Services Research 17, 814.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

McKeon G, Curtis J, Rostami R, Sroba M, Farello A, Morell R, Steel Z, Harris M, Silove D, Parmenter B, Matthews E, Jamaluddin J, Rosenbaum S (2024) Co-designing a physical activity service for refugees and asylum seekers using an experience-based co-design framework. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 26, 674-688.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Moll S, Wyndham-West M, Mulvale G, Park S, Buettgen A, Phoenix M, Fleisig R, Bruce E (2020) Are you really doing ‘codesign’? Critical reflections when working with vulnerable populations. BMJ Open 10, e038339.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Phillips C, Hall S, Elmitt N, Bookallil M, Douglas K (2017) People-centred integration in a refugee primary care service: a complex adaptive systems perspective. Journal of Integrated Care 25, 26-38.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Power R, Ussher JM, Hawkey A, Missiakos O, Perz J, Ogunsiji O, Zonjic N, Kwok C, Mcbride K, Monteiro M (2022) Co-designed, culturally tailored cervical screening education with migrant and refugee women in Australia: a feasibility study. BMC Women’s Health 22, 353.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Richard L, Richardson G, Jaye C, Stokes T (2019) Providing care to refugees through mainstream general practice in the southern health region of New Zealand: a qualitative study of primary healthcare professionals’ perspectives. BMJ Open 9, e034323.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Sieber JE (2009) Refugee research: strangers in a strange land. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics 4, 1-2.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Smith J, Daynes L (2016) Borders and migration: an issue of global health importance. The Lancet Global Health 4, e85-e86.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Suphanchaimat R, Kantamaturapoj K, Putthasri W, Prakongsai P (2015) Challenges in the provision of healthcare services for migrants: a systematic review through providers’ lens. BMC Health Services Research 15, 390.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Temple B, Edwards R (2002) Interpreters/translators and cross-language research: reflexivity and border crossings. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 1, 1-12.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Williams ME, Thompson SC (2011) The use of community-based interventions in reducing morbidity from the psychological impact of conflict-related trauma among refugee populations: a systematic review of the literature. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 13, 780-794.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |