The client and family experience of attending a nurse-led clinic for chronic wounds

Anusuya Dhar A * , Judith Needham A , Michelle Gibb B and Elisabeth Coyne A

A * , Judith Needham A , Michelle Gibb B and Elisabeth Coyne A

A

B

Abstract

The quality of life for individuals with chronic wounds is diminished due to poor health-related outcomes and the financial burden of wound care. The literature has shown nurse-led wound care to have a positive impact on wound healing and psychosocial wellbeing. However, there is minimal research investigating the lived experience of attending a nurse-led clinic for chronic wounds. The purpose of this study was to explore the client and family experience of attending a nurse-led clinic for chronic wounds.

Qualitative descriptive study. Semi-structured telephone interviews were transcribed verbatim and thematic analysis was undertaken.

Twelve clients and two family members participated, and the average length of interviews was 20 min. Three main themes emerged: (1) expecting and managing pain; (2) receiving expert advice and reflecting on previous care; and (3) managing the cost of care. There was an emphasis on the impact of chronic wounds on pain and the ability to complete the activities of daily living. Expert advice, client satisfaction and physical accessibility were highlighted as benefits of the clinic. Cost and minimal client education were identified as challenges of the clinic.

The findings demonstrated that chronic wounds have a significant impact on the client and family attending the nurse-led clinic. Comprehensive pain assessment, improved social support, better client education and cost-effective care is required to optimise the experience for people attending the nurse-led clinic.

Keywords: chronic wounds, community nursing, experience, family, nurse-led, primary health care, qualitative research, wound care.

Introduction

Nurse-led models of care are reshaping conventional health care by filling the gap in areas where there is an increased demand for services and workforce shortages. The benefits of nurse-led care include reduced waiting times, more cost-effective care, advanced nursing practice and offloading workload pressure on medical-led services (Allan 2018). However, there is minimal research available on the lived experience of attending a nurse-led model of care for chronic wounds, and whether current practice reflects the literature.

Chronic wounds have a significant impact on the health and wellbeing of an individual and their family (Wellborn and Moceri 2014). There are approximately 400 000 people in Australia living with chronic wounds, and it is estimated to cost the government 2% of national health care expenditure (Graves and Zheng 2014). The financial burden is also placed on the individual and their family, because there are minimal reimbursements for the cost of wound care. In Australia, the lack of reimbursement for wound care consumables may be seen as a disincentive for health care providers to provide evidence-based care (Kapp and Santamaria 2017). The literature has identified that individuals with chronic wounds spend approximately 10% of their disposable monthly income on wound care (Kapp and Santamaria 2017). Pain makes it increasingly difficult to complete day-to-day activities, and heightens the risk of developing anxiety and depression (Wellborn and Moceri 2014). The result of a combination of financial stressors and declining health leads to a poor quality of life in people with chronic wounds (Kapp and Santamaria 2017; Walker et al. 2023).

Living with a chronic wound is a difficult experience to face, and having a strong support network is fundamental towards being able to cope. The majority of people with chronic wounds are older adults, because they are more susceptible to age-related changes that have a negative impact on wound healing (Woo 2012). Older adults are at a greater risk of loneliness and social isolation, causing them to be more likely to develop negative health outcomes (Coyle and Dugan 2012). In the community, the majority of wound care is performed by nurses (Edwards et al. 2009). Leg ulcers are one of the most common chronic wounds, and approximately 80–90% of leg ulcers in Australia are treated by general practitioners and practice nurses (Norman et al. 2016). The literature has also demonstrated that nurse-led interventions have a positive impact on wellbeing and fill the gap of social support (Edwards et al. 2009; Van Hecke et al. 2011; Clark 2012; Upton et al. 2015).

Nurse-led care is guided by evidence-based practice to provide advanced nursing care that is innovative, easily accessible and cost-effective (Allan 2018). Within the community, nurse-led clinics are beneficial, because they provide continuity of care, reduced waiting times, high levels of client satisfaction and social support (Allan 2018). The positive outcomes of nurse-led clinics in wound care have been demonstrated in the literature; however, there is minimal research available on the lived experience of attending a nurse-led clinic for chronic wounds (Dhar et al. 2020). Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the experience of the client and family attending a community-based nurse-led clinic for people with chronic wounds.

Methods

This study used a descriptive qualitative design to evaluate the client and family experience of attending a community-based nurse-led clinic for chronic wounds.

Sample and setting

The study setting was a community-based nurse-led clinic for chronic wounds, developed as part of a pilot project in collaboration with a non-government organisation in South-East Queensland, Australia. The clinic was located in a suburban area where the non-government organisation already have a pre-existing building servicing clients receiving community health care. Referrals to the nurse-led clinic are either from the client themselves, general practitioner, hospital or internally within the non-government organisation. A convenience sample of clients’ and their family members, who attended the nurse-led clinic, volunteered to participate in the study after being invited via mail, telephone or in-person during their clinic appointment. This included past and current attendees of the clinic. Inclusion criteria for the study were participants who were past or current clients and family members, and attended the nurse-led clinic at least once. Exclusion criteria for the study were participants who were unable to speak the English language, were currently hospitalised and were known to have a cognitive impairment influencing their capacity to provide consent. Family members were recruited based on invitations passed on by the client.

Study procedures

Data collection was completed from February to June 2019. Semi-structured telephone interviews were completed at a time suitable for the participant. Phone interviews were audio-recorded and professionally transcribed verbatim. Member checking was completed, and participants were provided the opportunity to review their transcripts for validity. Three participants responded and made nil changes to their response. Demographic data were collected, including age, sex, race/ethnicity, living status and employment status. An open-ended interview guide was developed following a review of the literature, and expert opinion from clinicians and researchers (see Table 1; Dieperink et al. 2018). The family members completed their interviews separately to the client with the same interview guide. The interviewer was a registered nurse with experience in wound care (AD), and was not involved with the participants care in the nurse-led clinic.

| 1. How long have you been attending the wound clinic? | |

| 2. Why did you come to the wound clinic? | |

| 3. What were your expectations when you came to the clinic? | |

| 4. What has been your experience of attending the wound clinic? | |

| 5. What benefits do you see with attending the wound clinic? | |

| 6. What challenges do you see with attending the wound clinic? | |

| 7. What suggestions do you have for ways to improve the wound clinic? | |

| 8. Is there anything that you would like to add about your experiences of attending the wound clinic? |

Semi-structured interviews were undertaken to establish common themes, trends and patterns in the data. A multiphase thematic analysis was undertaken based on Braun and Clarke (2006). The transcripts were read and re-read by all members of the research team to generate a sense of the data.

Using an inductive approach, general themes were created based on text excerpts compiled and grouped into written tables in Microsoft Word, answering the questions outlined in the interview guide. Two researchers (AD, EC) collated recurring themes across the data set and came to a consensus during in-person meetings, and the final themes were presented and approved by all authors.

Ethics

Study procedures were reviewed and approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee from Griffith University, reference number 2018/922, and Anglicare Southern Queensland reference number EC01746. The principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki regarding human experimentation have been met. Participants were informed about the study through an information sheet and provided written consent in the nurse-led clinic. Verbal consent was obtained for past attendees of the nurse-led clinic during the phone interview.

Results

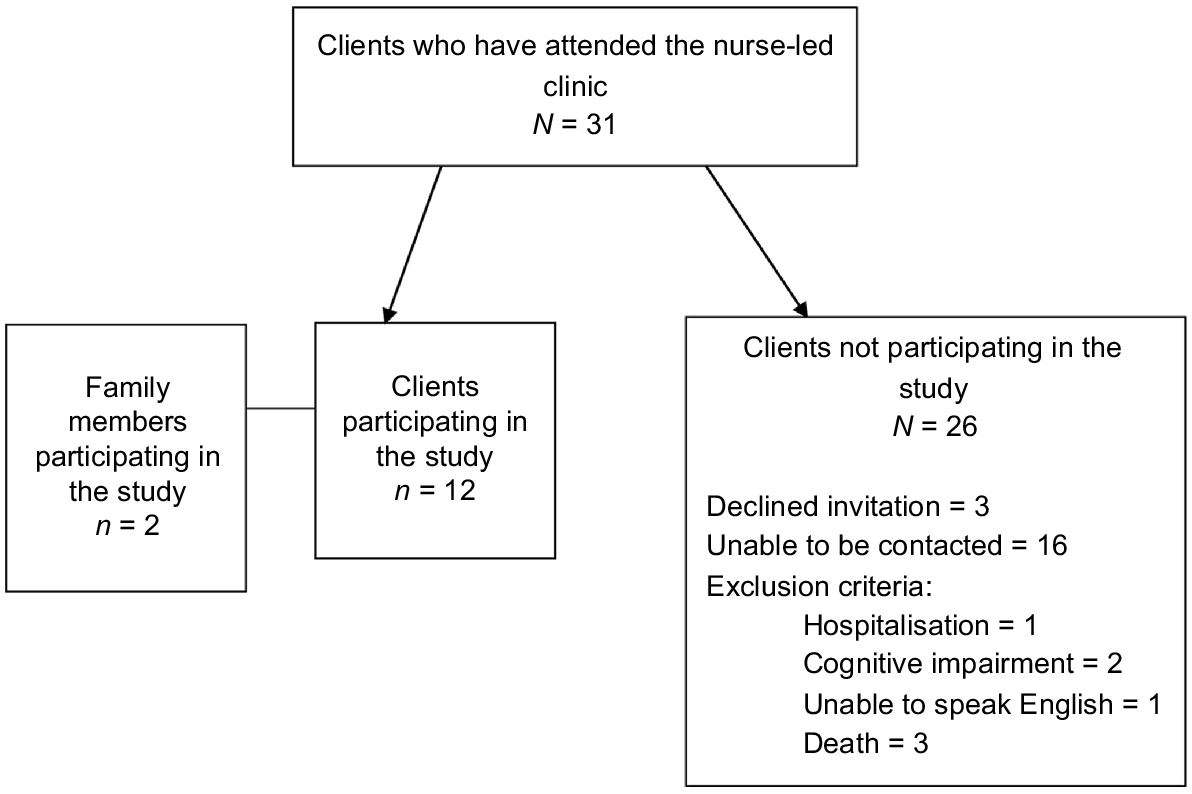

A total of 14 participants completed the interviews; 12 clients and two family members and participants’ ages ranged from 41 to 98 years (M = 66, s.d. = 15.72; See Table 2 for demographic data; see Fig. 1 for participant recruitment). The interviews were approximately 20 min in length. One family member was the client’s spouse, and the other family member was a parent.

| Variables | N | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male | 8 | 57 | |

| Female | 6 | 43 | |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 13 | 93 | |

| Pacific Islander | 1 | 7 | |

| Living status | |||

| Living with others | 8 | 58 | |

| Living alone | 6 | 43 | |

| Employment status | |||

| Unemployed | 1 | 7 | |

| Retired | 13 | 93 | |

One-third of clients (n = 5) attended the clinic on less than three occasions and continued their wound care in the home after receiving an initial consultation. Some clients (n = 4) attended on a regular schedule over a period of 3–6 months. One client was referred by the hospital, and four clients were referred internally within the community nursing agency. The remaining clients (n = 7) were referred by their general practitioner.

Themes

Thematic analysis identified three major themes: (1) expecting and managing pain, (2) receiving expert advice and reflecting on previous care, and (3) managing the cost of care.

This theme related to the participants discussing their experience of pain associated with chronic wounds and how the clinic had an influence on this experience. The two sub-themes were experiencing pain in the clinic and the influence of pain on daily life.

Experiencing pain in the clinic

… they knew how painful my leg was, because they could barely touch it when they cleaned it all up, it’s – oh, yeah, that was awfully painful. [C4]

Look, I’ve had 48 hours [in-reference to the amount of time the wound dressing has been on], I can’t sleep properly, I keep waking up and I’m in dreadful pain. [C6]

… how long is this pain going to last, because it was still hurting and he said, “It all depends on the person.” Well, after 48 hours at home, that’s when I rang up and I said, ‘I can’t take it any longer’. [C6]

… when I have the dreadful silver dressing on … I could have screamed with the pain. [C5]

… the wrapping compression bandage is too tight, I get pain. [C2]

Wound-related pain was mentioned in every interview, and the clients anticipated pain from their wound and during the appointment. However, the participants acknowledged that the nurses took their level of pain into consideration during their appointment. One family member expressed a greater desire for the clinic to be able to provide effective pain management.

Some clients responded negatively to the treatment provided based on the pain it had created.

Influence of pain on daily life

… it’s hard … I’ve got to put paper bags on both legs … it’s just so slippery on the floor. [C9]

Pain has a significant influence on the participant’s daily life, and is at the forefront of their mind. The participants reported an increased difficulty in completing their activities of daily living due to their level of pain and the type of wound dressing they were provided. Some participants were home bound, because they were unable to fit into their shoes, and one participant completed their grocery shopping online, because they were no longer able to walk. Showering was a difficult task for participants to complete.

This theme related to the participants describing the care they received in the nurse-led clinic. The two sub-themes were reflecting on previous experiences of wound care and satisfaction with the expert advice received from the nurse-led clinic.

Previous experience of wound care

… the other doctors, he couldn’t do nothing … now it’s getting better. [C6]

I spend so much time … in the hospital and last time my doctor said, ‘I don’t know what to do’. [C5]

Participants expressed their motivation for attending the clinic was to receive expert advice, because they were aware that a specialist wound nurse would be present There was a sense of frustration from most participants regarding their previous health care provider not being able to care for their wound.

Receiving expert advice from the specialist wound nurse

they’ve brought down the size of the legs … the wounds themselves have been drying up … they are getting better. [C3]

… before I used to limp a bit, now I can walk very, very well. [C6]

… but, um, it was worth definitely going down there, because we’re now into the, um, into the, ah, compressed stockings. [F1]

They’re great … she’s interested in my welfare. [C11]

However, after attending the nurse-led clinic, the participants were satisfied with the level of care they received. The majority of participants experienced wound healing, and noticed an improvement in their quality of life by attending the nurse-led clinic.

From a family perspective, they were able to recognise the benefit of attending the nurse-led clinic after observing their wound progressing into a simpler method of wound care.

On the contrary, one participant reported not experiencing wound healing and moved onto another service.

In the clinic, the participants reported a high level of satisfaction when interacting with the nurses. The staff were described as ‘polite’ and ‘friendly’, and there was no negative experience mentioned. From the family member’s perspective, they were able to recognise that the nurses were including them in their care, and were able to provide them with ongoing support via telephone or home visits.

This theme related to discussing the costs associated with wound care. The two sub-themes were managing the cost of wound dressing products and the need for more education before investing in a wound dressing regime.

Managing the cost of wound dressing products

We have to bring all our stuff in … [C10]

I mean, it’s cost me $679 for dressings and I can’t get that replaced. And that’s what I’m very cranky about. [C4]

… well it cost me $250 for them, okay, but they didn’t work and they hurt. [C5]

There were mixed opinions regarding the cost of attending the nurse-led clinic;, however, there was a general consensus that wound care was usually expensive, regardless of where they received care. Participants were aware that they were expected to pay for their wound care products; therefore, some participants were innovative and would bring their own supplies to the clinic sourced from a supplier or the internet.

Some participants found the clinic to provide affordable wound care products in comparison with previous wound care services they have attended. However, one participant expressed frustration they had invested a significant amount into their treatment, but did not achieve ideal outcomes from the client’s perspective.

Greater need for education on wound dressing products

… maybe more explanation in what they were ordering … [C2]

They’re prescribing something … I wasn’t over fond of. [C2]

They get in and fix them up and, ah, you go home again. [C8]

From there, some participants reflected on how they wanted to be more informed regarding their care.

This was highlighted when participants advised they regretted purchases they had made on wound care products that caused pain, and did not achieve a positive outcome or the wound product was not the adequate size.

The majority of participants would accept the care they received not fully comprehending the decision-making leading towards that direction of care.

Discussion

The demographic data in this study found that the majority of people were older adults and retired, reinforcing the common demographic of people with chronic wounds (Gould et al. 2015). Older adults experience longer wound healing times due to increased comorbidities and age-related changes that make them more susceptible to chronic inflammation and infection (Woo and Sibbald 2008; Gould et al. 2015). Wound pain was mentioned in every interview completed for this study, demonstrating the significant impact that pain has on daily life. The client and family explained that the nurses in the clinic acknowledged and considered their pain during wound care. This supported Frescos (2018) work, which found that nurses working within a range of areas (e.g. hospitals, community health, aged care facilities) were more likely to conduct a pain assessment in comparison with other health practitioners. However, pain was not always adequately managed within the nurse-led clinic, and the family had a greater desire for nurses to be able to provide better pain management. Woo and Sibbald (2009) found that pain impaired wound healing, and suggested using a framework where a comprehensive pain assessment guide is conducted prior to determining a wound care plan.

Chronic wounds have a negative influence on the ability of people to complete their basic activities of daily living (Wellborn and Moceri 2014). In this study, the two family members had a major role in being able to provide this level of support by assisting their family member with showering, transportation and managing health care needs. Due to the small sample size of family members in this study, it cannot be concluded that family always has a major role in supporting people with chronic wounds. For those with minimal social support, receiving practical support becomes increasingly difficult (Kouris et al. 2016). The nurse-led clinic was able to provide practical support through community transport and in-home care. To provide holistic care, the psychosocial wellbeing of the person with the wound has to be taken into consideration. In the study by Edwards et al. (2009) with 67 participants, they found improved quality of life, self-esteem, morale and wound healing within a group of people who received care in a nurse-led clinic that promoted peer support and socialisation, where a group of people with chronic wounds were able to communicate with each other in a communal setting. There is minimal research available on specifically improving the mental health and psychological wellbeing of people living with chronic wounds, and future research is warranted to improve health outcomes.

In this study, the majority of participants attended the nurse-led clinic because they were wanting to receive expert advice from a specialist wound nurse. Adderley and Thompson (2016) found nurses specialising in wound care had more post-graduate qualifications, and were more likely to make accurate judgements regarding the diagnoses and treatment of venous leg ulceration in comparison with general community nurses. This finding was based on the reasoning that community nurses had less exposure to complex wound care, as specialist wound nurses were the primary clinicians. However, the majority of care provided by a community nurse encompasses chronic wounds, and is one of the most common procedures in general practice (Innes-Walker et al. 2019). Interestingly, only 66% of community nurses attending a series of study days identified having no specialised training in wound care (Mahoney 2019). Participants in this study have experienced negative encounters regarding their wound care from previous health care professionals. Therefore, specialised training is required to prepare the workforce for increasingly complex wounds in the future within the ageing population (Pacella 2017).

The nurse-led clinic in this study was able to provide expert advice based on the comments provided from participants. The analysis revealed that the nurse’s knowledge and expertise in wound management influenced the client’s trust in the nurse. Multiple studies investigating nurse-led wound care have reported high levels of satisfaction with care provided by nurses, and the results of this study reinforce the current research (Edwards et al. 2009; Woo and Sibbald 2009; Van Hecke et al. 2011; Clark 2012; Wellborn and Moceri 2014; Upton et al. 2015). This highlights the important role nurses have in providing safe, quality care, and positions the nursing discipline at the forefront of wound management (Pacella 2017).

Current research highlights that nurse-led clinics in the community provide an accessible service, and this was reinforced based on the participants’ feedback (Randall et al. 2017). The World Health Organization (2020) outlines three categories to describe accessibility in health care, including: physical accessibility, economic accessibility and information accessibility. The nurse-led clinic provided community transport, simple referral processes and a safe environment for its participants; however, economic accessibility was not easily achieved based on the participants comments.

Chronic wounds cost the Australian healthcare system A$3 billion annually; however, the majority of cost is placed on the individual (Pacella 2017). Kapp and Santamaria (2017) found people with chronic wounds in the community spent approximately A$2475 on wound dressing products since the beginning of their wound. The participants in the current study reported that wound care products were expensive and often not suitable once purchased, adding extra costs to their personal health budget. The government fails to provide adequate funding to reimburse health care providers for the cost of wound care. Therefore, there is less incentive to provide this service. There are <200 people who receive subsidised wound care dressings from the federal government (Medical Technology Association of Australia 2020). This demonstrates a large disparity in the allocation of funding, because there are up to 400 000 people living with chronic wounds in Australia (Graves and Zheng 2014).

Nurse-led clinics have been shown to reduce costs in the hospital sector by providing an outpatient service for wound care; however, the individual is still left to bear the cost (Bergersen et al. 2016). This study was able to provide a real-world perspective on the client and family experience of managing the cost of wound care. The majority of studies investigating the outcome of wound care provide their services at no cost as part of the investigation. Therefore, it is not known whether this model of care would be sustainable without knowing whether the individual could afford the service (Shelton and Reimer 2018). Therefore, it is imperative for policy makers and government sectors to increase funding allocated to wound care to facilitate the provision of evidence-based care and better health outcomes (Pacella 2017).

To provide an accessible service, information accessibility ensures health care consumers are able to make informed decisions regarding their care at a level that is understandable to them (World Health Organization 2020). Some participants in this study expressed a greater desire to know more about their treatment. Through tailored education, nurses can provide individuals and families with the knowledge and skills required to self-manage their chronic illness, and make the most effective use of the healthcare system (Harris et al. 2008). Nurses can also encourage individuals to work collaboratively with their peers and general practitioners’ to build a stronger support network (Harris et al. 2008). Margolis et al. (2015) found providing education in the first month of wound care can significantly improve wound-related outcomes. Therefore, it is important for nurses to consider health literacy and provide education to empower people to make the best possible decisions regarding their own care.

Strength and limitations

The small sample size of family members reduced the generalisability of the results of how family members perceive nurse-led clinics; however, the findings were supported by the literature. Telephone interviews allowed participants to separate themselves from the clinic environment and share their experiences in a safe environment – their own home. The participants were at different stages in their wound care and attendance at the nurse-led clinic; therefore, their experience could have been different based on these factors.

Conclusion

This study explored the client and family experience of attending the nurse-led clinic, and the findings demonstrated a strong emphasis on the impact of chronic wounds on daily life, and the benefits and challenges of attending the nurse-led clinic. Through the participants’ stories, it was highlighted that comprehensive pain assessments, improved social support, better client education and cost-effective care is required to optimise the experience for people attending the nurse-led clinic.

Data availability

The data that support this study will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Declaration of funding

This study received funding from the Metro South Hospital and Health Service (MSHHS) and Brisbane South Primary Health Network (BSPHN) Living Healthier Lives Community Grant.

Acknowledgements

This paper received institutional support and was a partial requirement for the fulfilment of the Master of Acute Care Nursing (Dissertation) program from Griffith University, Australia.

References

Adderley UJ, Thompson C (2016) A comparison of the management of venous leg ulceration by specialist and generalist community nurses: a judgement analysis. International Journal of Nursing Studies 53, 134-143.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Allan C (2018) The efficacy of nurse-led clinic. Annals of Oncology 29, viii683.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Bergersen TK, Storheim E, Gundersen S, Kleven L, Johnson M, Sandvik L, Kvaerner KJ, Ørjasæter N-O (2016) Improved clinical efficacy with wound support network between hospital and home care service. Advances in Skin & Wound Care 29, 511-517.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3, 77-101.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Clark M (2012) Patient satisfaction with a social model of lower leg care provision. Wounds UK 8, 20-26.

| Google Scholar |

Coyle CE, Dugan E (2012) Social isolation, loneliness and health among older adults. Journal of Aging and Health 24, 1346-1363.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Dhar A, Needham J, Gibb M, Coyne E (2020) The outcomes and experience of people receiving community-based nurse-led wound care: a systematic review. Journal of Clinical Nursing 29, 2820-2833.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Dieperink KB, Coyne E, Creedy DK, Østergaard B (2018) Family functioning and perceived support from nurses during cancer treatment among Danish and Australian patients and their families. Journal of Clinical Nursing 27, e154-e161.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Edwards H, Courtney M, Finlayson K, Shuter P, Lindsay E (2009) A randomised controlled trial of a community nursing intervention: improved quality of life and healing for clients with chronic leg ulcers. Journal of Clinical Nursing 18, 1541-1549.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Frescos N (2018) Assessment of pain in chronic wounds: a survey of Australian health care practitioners. International Wound Journal 15, 943-949.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Gould L, Abadir P, Brem H, Carter M, Conner-Kerr T, Davidson J, DiPietro L, Falanga V, Fife C, Gardner S, Grice E, Harmon J, Hazzard WR, High KP, Houghton P, Jacobson N, Kirsner RS, Kovacs EJ, Margolis D, McFarland Horne F, Reed MJ, Sullivan DH, Thom S, Tomic-Canic M, Walston J, Whitney JA, Williams J, Zieman S, Schmader K (2015) Chronic wound repair and healing in older adults: current status and future research. Wound Repair and Regeneration 23, 1-13.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Graves N, Zheng H (2014) Modelling the direct health care costs of chronic wounds in Australia. Wound Practice & Research: Journal of the Australian Wound Management Association 22, 20-33.

| Google Scholar |

Harris MF, Williams AM, Dennis SM, Zwar NA, Powell Davies G (2008) Chronic disease self-management: implementation with and within Australian general practice. Medical Journal of Australia 189, S17-S20.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Innes-Walker K, Parker CN, Finlayson KJ, Brooks M, Young L, Morley N, Maresco-Pennisi D, Edwards HE (2019) Improving patient outcomes by coaching primary health general practitioners and practice nurses in evidence based wound management at on-site wound clinics. Collegian 26, 62-68.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Kapp S, Santamaria N (2017) The financial and quality-of-life cost to patients living with a chronic wound in the community. International Wound Journal 14, 1108-1119.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Kouris A, Christodoulou C, Efstathiou V, Tsatovidou R, Torlidi-Kordera E, Zouridaki E, Kontochristopoulos G (2016) Comparative study of quality of life and psychosocial characteristics in patients with psoriasis and leg ulcers. Wound Repair and Regeneration 24, 443-446.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Mahoney K (2017) More wounds, less time to treat them: 1717 nurses discuss the challenges in wound care in a series of study days. British Journal of Community Nursing 22, S33-S38.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Margolis DJ, Hampton M, Hoffstad O, Scot Malay D, Thom S (2015) Health literacy and diabetic foot ulcer healing: health literacy and diabetic foot ulcer. Wound Repair and Regeneration 23, 299-301.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Medical Technology Association of Australia (2020) Evidence for funding of the treatment and management of chronic wounds in Australia. Available at https://www.mtaa.org.au/sites/default/files/uploaded-content/website-content/Chronic%20Woundsv5.pdf [Verified 16 February 2022]

Norman RE, Gibb M, Dyer A, Prentice J, Yelland S, Cheng Q, Lazzarini PA, Carville K, Innes-Walker K, Finlayson K, Edwards H, Burn E, Graves N (2016) Improved wound management at lower cost: a sensible goal for Australia. International Wound Journal 13, 303-316.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Pacella R (2017) Chronic wounds in Australia. Available at https://eprints.qut.edu.au/118020/ [Verified 16 February 2022]

Randall S, Crawford T, Currie J, River J, Betihavas V (2017) Impact of community based nurse-led clinics on patient outcomes, patient satisfaction, patient access and cost effectiveness: a systematic review. International Journal of Nursing Studies 73, 24-33.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Shelton A, Reimer N (2018) Telehealth wound applications: barriers, solutions, and future use by nurse practitioners. Online Journal of Nursing Informatics 22,.

| Google Scholar |

Upton D, Upton P, Alexander R (2015) Contribution of the Leg Club model of care to the well-being of people living with chronic wounds. Journal of Wound Care 24, 397-405.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Van Hecke A, Grypdonck M, Beele H, Vanderwee K, Defloor T (2011) Adherence to leg ulcer lifestyle advice: qualitative and quantitative outcomes associated with a nurse-led intervention. Journal of Clinical Nursing 20, 429-443.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Walker RM, Rattray M, Lockwood I, Chaboyer W, Lin F, Roberts S, Perry J, Birgan S, Nieuwenhoven P, Garrahy E, Probert R, Gillespie BM (2023) Surgical wound care preferences and priorities from the perspectives of patients: a qualitative analysis. Journal of Wound Care 32, S19-S27.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Wellborn J, Moceri JT (2014) The lived experiences of persons with chronic venous insufficiency and lower extremity ulcers. Journal of Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nursing 41, 122-126.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Woo KY (2012) Exploring the effects of pain and stress on wound healing. Advances in Skin & Wound Care 25, 38-44.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Woo KY, Sibbald RG (2008) Chronic wound pain: a conceptual model. Advances in Skin & Wound Care 21, 189-190.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Woo KY, Sibbald RG (2009) The improvement of wound-associated pain and healing trajectory with a comprehensive foot and leg ulcer care model. Journal of Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nursing 36, 184-191.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

World Health Organization (2020) Accessibility. Available at https://www.who.int/gender-equity-rights/understanding/accessibility-definition/en/ [Verified 16 February 2022]