‘A sense of self, empowerment and purposefulness’: professional diversification and wellbeing in Australian general practitioners

Jill Benson A B * , Shaun Prentice A C , Penny Need B , Michelle Pitot B and Taryn Elliott B

A C , Penny Need B , Michelle Pitot B and Taryn Elliott B

A

B

C

Abstract

Burnout and workforce shortages comprise a vicious cycle in medicine, particularly for Australian general practitioners (GPs). Professional diversification, whereby individuals work multiple roles across their week, may help address this problem, but this strategy is under-studied.

We surveyed 1157 Australian GPs using qualitative and quantitative questions examining professional diversification, values, autonomy, and wellbeing. Quantitative data were analysed using inferential statistics, whilst qualitative data were analysed using inductive thematic analysis. We triangulated the data by using the qualitative findings to inform further quantitative testing.

Approximately 40% of the sample had diversified. Although diversifying was not significantly associated with wellbeing, the qualitative data indicated that diversification supported GPs’ wellbeing by enhancing career sustainability, accomplished through various pathways (e.g. value fulfilment, autonomy, variety). Subsequent quantitative analyses provided evidence that these pathways mediated the relationship between diversification and wellbeing. To diversify, GPs needed particular personal qualities, external supports, flexibility, and serendipity. Barriers to diversifying mirrored these factors, spanning individual (e.g. skillset) and situational levels (e.g. autonomy, location).

Diversification can support GPs’ wellbeing if it meets their needs. Organisations should focus on publicising opportunities and accommodating requests to diversify.

Keywords: diversify, general practice, professional roles, values, wellbeing, workforce.

Introduction

Medicine, particularly primary care, faces a ‘burnout epidemic’, with 73% of GPs saying they were burnt out in the recent Health of the Nation report (Rotenstein et al. 2018; Prentice et al. 2020; Royal Australian College of General Practitioners 2022). Amongst the deleterious outcomes is an increased intention to resign, which is alarming given severe general practice workforce shortages (Murray et al. 2016; Hamidi et al. 2018; O’Connor et al. 2019; Deloitte Access Economics 2022; Özkan 2022). Research also highlights that increased workload is associated with greater burnout, creating a vicious cycle between workforce shortages and burnout (Alarcon 2011; Zhou et al. 2020). These findings demonstrate the urgent need for burnout prevention and management interventions that do not simultaneously exacerbate workforce shortages.

Theoretically, professional diversification (defined as undertaking multiple professional roles) may meet this requirement. In a landmark finding, Shanafelt et al. (2009) found that doctors who spent 1 day a week engaging in tasks within their role that they found to be most meaningful had a reduced risk of burnout (see also Ko et al. 2020). We hypothesised that this finding may be extended to professional diversification. This would be consistent with previous suggestions that professional diversification can support medical career sustainability (Stevenson et al. 2011; Eyre et al. 2014; Bentley et al. 2022). This has led to calls for ‘portfolio careers’ to be formalised and supported for established GPs and also in training programs (Eyre et al. 2014; BMJ Careers 2022).

In practice, a recent Australian study identified a third of their sample of early career GPs were engaging in diversification (Bentley et al. 2022). Similarly, part-time practice is becoming increasingly common amongst GPs (Australian Government, Department of Health and Aged Care 2020), potentially to facilitate diversification. Despite these observed trends and the theoretical benefits of diversification for burnout prevention and career sustainability, there is little research on this topic. Indeed, we only know of two studies examining such diversification in GPs (Dwan et al. 2014; Bentley et al. 2022). Notably, these studies took a workforce perspective rather than considering the implications for burnout and career sustainability.

To address this gap, we undertook this exploratory study. Given our interests in both burnout and career sustainability, we took a broader perspective of exploring the relationship between professional diversification and wellbeing. We viewed wellbeing and burnout as each being multifaceted constructs lying on a continuum of the degree of one’s value fulfilment (Penwell-Waines et al. 2018; Prentice et al. 2023a). In this study, we specifically sought to quantitatively and qualitatively explore whether professional diversification and wellbeing were related, consider mechanisms underpinning this relationship, and highlight the facilitators and barriers to professional diversification.

Methods

Procedures

This manuscript reports on a broader study, with further details provided elsewhere (Prentice et al. 2023b). We surveyed Australian GPs between February and March 2022 measuring their professional autonomy, wellbeing, values, and value fulfilment using pre-existing instruments (Lundgren et al. 2012; Salvatore et al. 2018; Gates et al. 2019; Harris 2021) (see Appendix 1 in Supplementary material). We selected the Burnout–Thriving Index (Gates et al. 2019) to measure burnout and wellbeing, as it aligned with our conceptualisation of these constructs as sitting upon a single continuum. The Burnout–Thriving Index has been validated against the Maslach Burnout Inventory (Maslach et al. 2016; Gates et al. 2019), however, it allows individuals to use their own definition for each of the descriptive anchors, which we believed provided greater validity owing to the absence of instruments developed in line with the theoretical model of burnout and wellbeing we selected for this study. Additionally, we explored participants’ degree of professional diversification (i.e. how many professional roles they held). For each role, participants needed to report on how meaningful they found that role, which values that role fulfilled, their preferred and actual weekly time allocation for that role, and the type of region where they undertook that role (i.e. urban, outer metro, rural, remote, overseas). These questions were supplemented with five optional open-ended questions examining how diversification enhances GPs’ wellbeing, as well as facilitators and barriers to diversifying.

A steering committee of experts, GPs, and other stakeholders helped develop and implement this research and reviewed the data interpretation.

Analysis

We conducted this research within a postpositivist paradigm. Three researchers (JB, SP, and PN) had actively diversified careers, providing them lived experience. They did not bracket their experiences during analysis, but enhanced their reflexivity by meeting regularly to discuss their coding decisions. Although literature informed the quantitative hypotheses, the absence of literature considering the benefits and mechanisms of diversification meant that data was approached de novo to inductively generate models explaining the phenomena of interest.

Only one data collection method was used and hence the study was not a mixed methods design (Johnson et al. 2007). However, we used a mixed methods analytic approach to interface the quantitative and qualitative data, separately analysing the quantitative and qualitative data followed by triangulation.

Quantitative data analysis explored how burnout and professional meaningfulness each related to three variables:

The proportion of time GPs spent on their most meaningful role,

The discrepancy between GPs’ actual and preferred time allocation between their roles,

The extent of diversification (i.e. their number of different roles).

To investigate relationships with proportion of time and time allocation discrepancy, we used Pearson’s correlation coefficients. To evaluate the optimal time investment, we calculated odds ratios using 5% increments of time spent on one’s most meaningful role with burnout prevalence (using the Burnout–Thriving Index’s cut-off; Gates et al. 2019). We explored the association between burnout and extent of professional diversification using ANOVAs. We chose ANOVAs instead of t-tests to be sensitive to effects amongst those with more than two roles, rather than dichotomising the diversification variable. We collapsed those with more than five roles into a single category to facilitate analysis. For ANOVAs, we tested homogeneity using Levene’s test, using Welch corrections where needed.

Simultaneously, we undertook qualitative analysis. We imported the dataset into NVivo V20 for Windows (QSR International), creating folders corresponding to the five open-ended questions (i.e. how diversification supports wellbeing, facilitators to diversifying, barriers to diversifying, the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on diversifying, and the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on wellbeing). We used these folders to structure our analysis by coding content pertaining to a question to its corresponding folder. PN, MP, and SP each coded the same 50 responses inductively using template analysis (Brooks et al. 2015). Coding entailed selecting portions of data and storing these within codes. Once each coder had analysed these responses, they met and fused their structures into a master that the three analysts applied to the remainder of the dataset. A pool of all responses was available, from which an analyst would select a package of 50 that they would analyse and archive from the shared pool. In this way, the responses were divided amongst the three analysts. Once all responses had been analysed, the three coders and JB met to share and fuse their coding structures to create a final master structure. Since the coding structure evolved over time, we wanted to ensure the robustness of the coding structure and comprehensiveness of the coding process. Therefore, JB applied the master structure to all responses; once completed, JB’s coding was merged with the coding of the other three analysts to produce the final qualitative dataset. We assessed inter-rater reliability by comparing JB and SP’s coding on a randomly selected set of 50 responses that SP had not previously coded. Inter-rater agreement was assessed using Cohen’s Kappa, with final agreement ranging between k = 0.898 and 0.988.

Given the quantitative and qualitative data were exploring similar questions, we triangulated the two types of data by quantitatively evaluating the qualitative findings. To accomplish this, JB and SP reviewed the qualitative themes and identified those of theoretical significance within the thematic structure. For themes selected as theoretically important, we generated binary variables indicating whether a participant’s responses included that theme. In doing so, we acknowledged that the absence of a theme from a response would not negate the applicability of that theme for that participant. Whilst this necessarily meant any quantified findings would be highly tentative, we sought to somewhat compensate for this by requiring a theme to have a sizeable number of responses (> 50) for it to be eligible for quantification. Once themes were selected, SP used NVivo to generate a matrix identifying which of the themes were raised by each participant, thereby quantifying the qualitative responses. He then amalgamated this matrix with the broader quantitative dataset. We then met as a team to identify hypotheses emerging from the qualitative data that we wanted to quantitatively assess.

Results

Participant characteristics

The survey was responded to by 1820 GPs (4.74% of all Australian GPs). After removing partially completed surveys, 1157 responses remained. Participant characteristics are reported in Table 1. A Welch’s t-test indicated no gender difference in the degree of professional diversification (t(865.0) = 1.426, P = 0.154).

| Characteristic | % of total sample (N) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 62.40% (722) | |

| Male | 35.09% (406) | |

| Other/prefer not to say | 1.30% (15) | |

| Age | ||

| 20–29 | 7.43% (86) | |

| 30–39 | 32.67% (378) | |

| 40–49 | 25.24% (292) | |

| 50–59 | 16.16% (187) | |

| 60–69 | 12.36% (143) | |

| 70+ | 4.75% (55) | |

| Years of GP experience | ||

| 0–5 | 33.62% (389) | |

| 6–10 | 18.58% (215) | |

| 11–15 | 10.63% (123) | |

| 16–20 | 7.87% (91) | |

| 21–25 | 6.83% (79) | |

| 26+ | 21.35% (247) | |

| Involvement in GP education | ||

| Not involved | 46.50% (538) | |

| Medical educator | 9.68% (112) | |

| Supervisor | 23.42% (271) | |

| Registrar | 17.89% (207) | |

| Number of roles | ||

| 1 | 35.44% (410) | |

| 2 | 24.63% (285) | |

| 3 | 19.53% (226) | |

| 4 | 9.59% (111) | |

| 5 | 5.96% (69) | |

| 6+ | 4.84% (56) | |

Note: Providing demographic details was not mandatory, so percentages do not sum to 100%.

How diversification affects wellbeing

Amongst the 747 (64.56%) GPs who had diversified (i.e. held more than one role) there were positive correlations between the proportion of one’s working week spent in one’s most meaningful role and both wellbeing (r = 0.161, P < 0.001, N = 746) and professional meaningfulness (r = 0.386, P < 0.001, N = 745). Spending less than 15% of one’s working week in one’s most meaningful role doubled (OR = 2.216) one’s risk of burnout (95%CI: 1.22–4.024, P = 0.007, N = 740). Spending additional time in one’s most meaningful role yielded no further benefits. The larger the discrepancy between diversified GPs’ actual and desired allocation of their working week across their roles (N = 1157), the greater their burnout (r = −0.211, P < 0.001) and lower their professional satisfaction (r = −0.211, P < 0.001).

We analysed 913 responses to the question ‘When reflecting on your level of professional diversity, what aspects of it do you think enhance your wellbeing?’, described below (themes are in italics; see Table 2).

| Theme | Number of responses (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Diversification harms GPs’ wellbeing | 5 (0.5%) | |

| Variety | 800 (87.6%) | |

| Relational diversity | 392 (42.9%) | |

| Autonomy with flexibility | 89 (9.8%) | |

| Workload feasibility | 17 (1.9%) | |

| Working in an area of interest | 35 (3.8%) | |

| Fulfilling values | 205 (22.5%) | |

| Growth | 207 (22.7%) | |

| Enriching professional relationships | 123 (13.5%) | |

| Complementing roles | 56 (6.1%) | |

| Enhanced clinician quality | 37 (4.1%) | |

| Total responses | 913 (100%) |

Few participants suggested that professional diversification harms GPs’ wellbeing. They cited having less clinical time and lower output, a risk of deskilling, and experiencing greater administrative and learning loads. For some in rural areas, diversity was ‘…driven by adversity’. Conversely, the overwhelming majority described how diversifying supported their wellbeing, believing that professional diversity made GPs’ careers more sustainable in multiple ways.

Variety was valued, including different content, financial setups, organisations, environments, relationships, and working styles. Many desired such variety as respite from mainstream general practice, described as ‘onerous’, ‘relentless’, ‘undervalued’, ‘disrespected’, ‘isolating’, ‘time-pressured’, ‘draining’, ‘disheartening’, ‘soul destroying’, and ‘overwhelming’. GPs were ‘emotionally’ and ‘administratively burdened’, ‘worried about making a mistake or having a complaint’, and faced ‘huge expectations’. Variety meant being ‘less drained by back-to-back patients and the intensity of the time pressure racing the clock all day’, affording them time to ‘debrief with other GP colleagues’ and to engage with their family, friends, and outside interests.

Mentally switching between roles meant GPs were more ‘mentally stimulated’, able to be ‘creative, intuitive and curious’ in one role and ‘compassionate, kind, focused and orderly’ in another. Different workplaces with different people, sub-specialties, structures, styles, and environments supported their sense of autonomy, engagement, ‘refreshment’, and enjoyment, generating a ‘key to longevity’. Working with different management styles and a supportive workplace where there is ‘good management that cares about their employees’ or a ‘flat hierarchical structure’ was a bonus.

Different working styles could make ‘the working week more interesting’, such as ‘some small business for controlling my work structure and time, some salaried for financial security, some specialised for satisfaction of expertise, some teamwork for company and humour’. Hospital work, research, and teaching enabled GPs to work with teams, contrasting with the ‘isolation of mainstream general practice’. A ‘different cognitive load’ across roles could assist: ‘a wide range of tasks and flexibility allows me to work in a more mindful way.’

Autonomy with flexibility was the essence of success, including working hours, leave, use of telehealth vs face-to-face, workplace conditions, organisational structures, and locum opportunities, choosing roles with more financial security, job security, or safety. The ability to choose to balance work and non-work was important, with diversification offering ‘time to think and reflect without pressure to perform or work too hard’.

Some commented that diversifying made their workload more feasible, providing an opportunity ‘to recover from more demanding roles’; ‘being able to limit the time spent on [these roles] makes them sustainable’. Diversifying also allowed GPs to work in an area they found interesting, engaged and challenged by the ‘richness’ of the diversity, both at a personal and a professional level.

Fulfilling values was an essential feature for many, doing ‘richer work and not routine rushed and boring work’. This included the satisfaction of ‘giving back’ through mentoring, transferring skills, and sharing knowledge and experience with students and registrars, which could ‘refresh [their] optimism’ about ‘reproducing [themselves] in the next generation’. It was about having a ‘wider scope of impact’, ‘assisting a great number of people’, often underpinned by an ethical duty to assist people who ‘may not otherwise have access to great medical care’.

Value fulfilment also brought personal benefits, helping some to ‘[feel] like I belong to something greater’. Commonly, diversification supported their sense of accomplishment, from ‘knowing I did a good, compassionate and caring job’ to ‘being creative and finding new solutions’, and supported a sense of enjoyment and ‘satisfaction’ gained from diverse roles, producing ‘engagement’, ‘enthusiasm’, ‘joy’, ‘motivation’, ‘inspiration’, and ‘energy’. One reflected, ‘I have never been bored and have been extraordinarily privileged to have had the career I have had’.

A common value was security, especially adequate income. For example, some chose not to teach because it was not ‘financially viable’. Others chose locum work, as it guaranteed ‘a good salary where and when I want’. Diversification could bring ‘less bureaucracy’ and ‘less paperwork’, meaning ‘less of my own unpaid time at the end of the day’ and ‘I feel less burned out when I am financially rewarded for my efforts’.

Another theme was relational diversity, which was a catalyst for growth by exposing GPs to larger professional networks, generating friendships, debriefing opportunities, and support. Working with a wide patient range broadened a GPs’ exposure to different life experiences, cultures, languages, ages, sexualities, stages of life, and socioeconomic backgrounds. This contributed to personal and professional growth: ‘increased diversity encourages me to see things from different points of view, to be more curious and learn to be more respectful’, teaching ‘resilience and tolerance’. Greater self-awareness was facilitated by ‘time to think and reflect’ and ‘debrief with colleagues’, and encouraged GPs to leave ‘my comfort zone’ and to ‘put up your hand and have a go’. Many commented that diversity facilitated ‘intellectual stimulation’ and neuroplasticity by using a ‘different part of my brain’, cultivating curiosity and openness, and ‘a more well-rounded sense of my professional self’. For some, diversification ‘helped me better see the bigger picture of where general practice sits in the health system’ and ‘increases tolerance towards institutional and staff shortcomings’. This could build GPs’ capacity to manage ‘challenging’ and ‘stressful’ situations and workplace relationships.

Professional diversity also enriched their professional relationships, assisting with the balance between ‘building and learning from others’ and ‘being able to be autonomous’, and enabling ‘working with people who challenge my thinking but share my core values’. Working in a supportive environment ‘where each member of the team thinks about everyone’s wellbeing, safety and professional growth’ meant the GP could ‘authentically express myself without fear of judgement or negative repercussions for my career’.

A bonus was when roles complemented each other, when ‘one place teaches me things I apply to another place’. Some believed that working across different roles enhanced their quality as a clinician: ‘Non-clinical time … helps me think about clinical problems differently and helps recharge for clinical days. Clinical days help me stay relevant, practice what I teach, be genuine, be accountable to others less fortunate, and ward off existential crises as I do believe I may have an impact at some level’.

Despite this qualitative data, an ANOVA uncovered no relationship between diversifying and GPs’ wellbeing levels (F(6, 29.101) = 0.849, P = 0.543). Although diversification was associated with professional meaningfulness (F(5, 238.461) = 10.110, P < 0.001), this produced a small effect (η2 = 0.039). Post-hoc tests identified that having more than two roles was not associated with significant incremental benefits (all P ≥ 0.09).

To reconcile the contradicting qualitative and quantitative findings, we hypothesised that diversification itself may not relate to burnout or wellbeing, but that the qualitative themes mediated the relationship between diversification and wellbeing. To test this, we explored the relationships between diversification and both value fulfillment and professional autonomy, variables that were captured in both the qualitative and quantitative data. Mann–Whitney U tests revealed that GPs who had diversified showed significantly higher autonomy (W = 172 766, P < 0.001) and value fulfillment (W = 167 233, P = 0.009). We also observed that burnout was significantly associated with both lower value fulfillment and professional autonomy (Prentice et al. 2023b). This supported the notion of a mediated relationship between diversification and wellbeing.

Facilitators to diversification

When asked about factors that facilitated diversification, GPs’ responses coalesced beneath five core themes (see Table 3). As a static factor, the theme that general practice is inherently diverse, including rural generalism, procedural, nursing homes, different subspecialties, gender diversity, socio-economic status, multicultural, Aboriginal health, or leadership roles, was conceptualised as the foundational factor, upon which sat the other four somewhat more dynamic themes.

| Theme | Number of responses (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| General practice is inherently diverse | 74 (8.1%) | |

| External supports | 322 (35.3%) | |

| Personal qualities | 572 (62.7%) | |

| Flexibility | 324 (37.5%) | |

| Serendipity | 242 (26.5%) | |

| (Total responses) | 912 (100%) |

The second theme was external supports that support, or encourage, GPs to pursue diversification. A key support was organisations, including workplaces that encouraged autonomy and permitted GPs to work part-time, and larger organisations, such as universities and primary health networks, that ‘encourage GP participation’. GP registrars found the requirement to work across settings ‘… allows adaptability to different work scenarios’.

The other external support was relationships, including supportive partners, work colleagues, parents, or peers, who could reduce outside responsibilities, build financial security, and provide advice and debriefing. Networks increased exposure to, and involvement with, different people, organisations, and settings, raising awareness of opportunities. Individuals could repay this by supporting others, satisfying a ‘desire to encourage future generations and be a part of that process’.

Another theme was one’s personal qualities, including demographics, such as being female, multilingual, or ‘older and less gullible’. Certain personality traits were important, such as self-confidence, negotiating skills, love of learning, or ‘adventurous spirit’. Curiosity about other fields coupled with courage, adventurousness, ‘slightly risk-taking’, passion, a love for novelty, creativity, and being outgoing were features of GPs who diversified. These were essential when opportunities needed to be created and strategically pursued.

A commitment to continuous personal and professional growth drove qualities such as persistence, versatility, and ‘continually seeking new challenges and opportunities’. The ‘determination and courage’ to see ‘barriers as a challenge to be overcome’ came from a commitment to ‘recognise what I enjoy and gradually increase my time doing more of that and less other work’. This drew upon ‘the length and breadth of previous clinical and life experience … [which] has shaped my interest and willingness to cover a range of professional roles, and has also helped decide which ones are less important to me’.

External supports and personal qualities interacted through a fourth theme: having sufficient flexibility to accept opportunities as they presented. Central was autonomy to make decisions about one’s work life, often coupled with financial flexibility. This was multi-factorial, including organisational factors (e.g. stable salary), personal circumstances (e.g. dual incomes), and life decisions (e.g. satisfaction with a lower income). Another facilitator was time, for instance life-stage, such as semi-retirement or a life-choice including decisions about business ownership, and whether to work part-time.

The final theme was serendipity. Different opportunities developed from different locations, demographics, ethnicities, financial backgrounds, nearby health or academic facilities, and unexpected outcomes of life circumstances, for example ‘having to move around with my spouse has forced me to move practices’. Workplace features could enable diversification, for example teaching registrars or medical students, a lack of specialist or tertiary support enabled subspecialty opportunities, and ‘the shortage of GPs has allowed me to negotiate a mix of urban and rural work’.

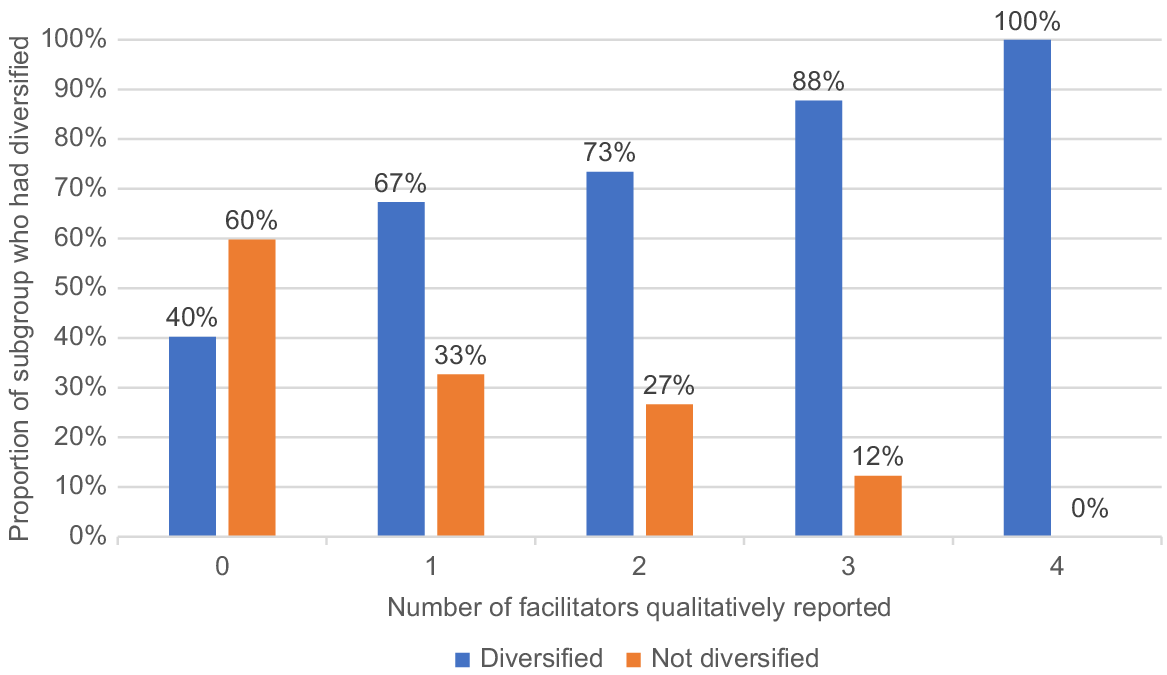

The data suggested each of these facilitators (personal qualities, external supports, flexibility, and serendipity) needed to work in tandem to support diversification. We quantitatively tested this hypothesis, examining whether there were differences in the number of these themes reported by participants who had and had not diversified. A chi-square test demonstrated a significant association between the number of facilitators raised and likelihood of diversifying (χ2(4) = 60.005, P < 0.001). Indeed, all 18 participants who raised all four facilitators had also diversified (see Fig. 1).

Association between the number of facilitator themes raised in qualitative questions and professional diversification in a sample of Australian GPs (N = 872).

For many, COVID introduced new prospects for diversification such as vaccination and respiratory clinics, psychological therapy, online teaching, locuming, and public health. More online courses ‘opened up access to courses … with minimal disruption from travel and expense.’ Telehealth helped overcome distance and location, and working from home increased family time. Additionally, ‘[finding] time again in my day’ from not commuting and service declines increased some participants’ capacity to diversify and engage in self-care.

For many, COVID was a ‘circuit-breaker’ that prompted a realisation that ‘I would be much happier diversifying and pursuing my specific interests.’ COVID helped them ‘assess what is truly important and …[acquire] the courage to take on a university degree in a completely different area of practice’, ‘to rethink my priorities and enhance my work/life balance’, and ‘to re-evaluate and re-design my working conditions’.

Barriers to diversification

When exploring the barriers to diversifying, participants described both current impediments and anticipated barriers to diversification (see Table 4).

| Theme | Number of responses (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Current impediments | ||

| Individual characteristics | 300 (32.0%) | |

| Age | 14 (1.5%) | |

| Ill health | 17 (1.8%) | |

| Lack of desire | 42 (4.5%) | |

| Personality | 83 (8.8%) | |

| Skillset and experience | 160 (17.0%) | |

| Situational characteristics | ||

| Micro | 651 (69.3%) | |

| Macro | 400 (42.6%) | |

| Anticipated barriers | ||

| External perceptions | 42 (4.5%) | |

| Greater workload | 76 (8.1%) | |

| Loss | 142 (15.1%) | |

| Policies | 22 (2.3%) | |

| Risk | 12 (1.3%) | |

| Unpredictability of future work | 10 (1.1%) | |

| (Total responses) | 939 (100%) | |

The factors inhibiting participants’ current desire or efforts to diversify fell within two overarching categories: individual and situational. Some highlighted individual characteristics such as age, ill health, lack of desire to diversify, and the effort required. Personality factors such as being introverted, apprehensive, indecisive, risk averse, or unassertive impeded GPs from diversifying. Commonly GPs discussed lacking confidence to pursue opportunities, using such phrases as ‘imposter syndrome’, ‘fear of the unknown’, ‘lack of courage’, ‘self-doubt’, and ‘fear of failure’. A further factor was a sense of duty to others. Some did not want to increase colleagues’ workload, while others felt a duty to their patients. This was exacerbated by workforce shortages, reducing service provision, and continuity of care.

The other individual barrier was the need for additional skillsets and experience. Developing these required financial and time investments, organisational skills, exams, and support structures. Whereas the generalist nature of general practice supported diversification for some, others felt it meant they lacked diverse skillsets or that the high workload impeded opportunities to build skills or gain sufficient experience for another role. This was also difficult for registrars who have ‘limited exposure to other roles during training’.

We classified situational impediments as ‘micro’ (the immediate environment e.g. family, workplace) or ‘macro’ (structural or organisational factors e.g. government policy). At the micro level, the key barriers were personal commitments and current stage of life, spanning caring, parenting, marriage, low social supports, and financial imperatives. The ‘number of ‘balls in the air’ in my life’ correlated negatively with the energy to diversify. These commitments fed into the broader context of an individual’s life, including ‘poor management with unrealistic expectations, late nights and sleep deprivation, listening to repetitive sad histories, having a family you want to spend time with, a partner where there is a disparity of parental duties and housework tasks, friends that are also burnt out by life/work demands, menopause, teenagers, only 24 h in a day’.

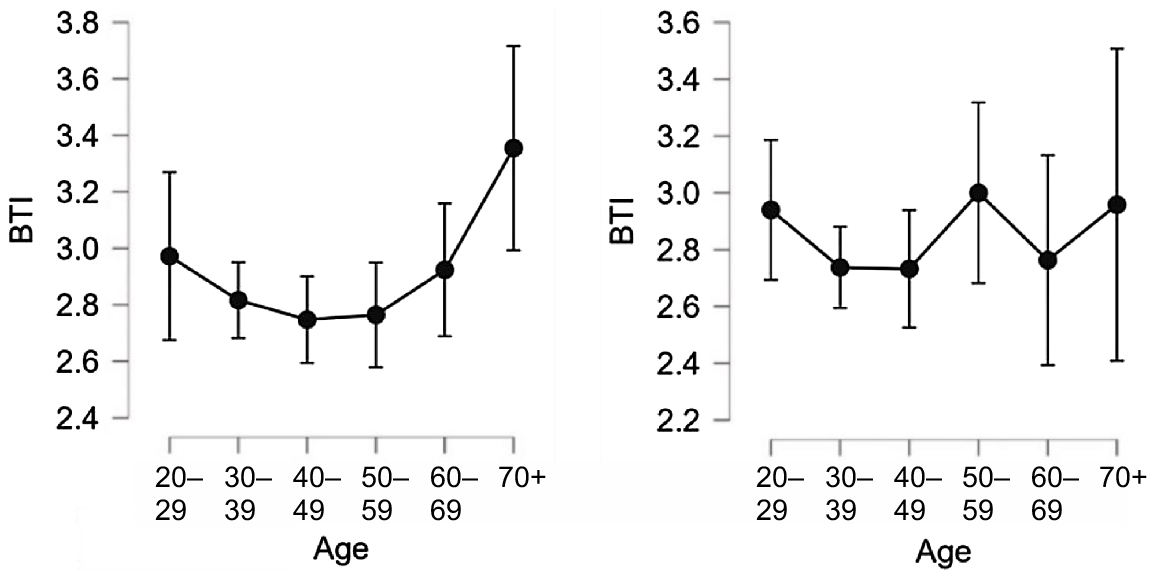

We quantitatively examined the apparent role of life stage in determining the effect of diversification on wellbeing. We explored the relationship between burnout and age amongst those who did and did not diversify using ANOVAs, predicting that the diversified group would show a more pronounced U-shaped association (i.e. lower wellbeing in middle age categories) than the non-diversified group. In those who had not diversified, the ANOVA yielded non-significant results (F(5, 110.136) = 0.873, P = 0.502). For those who had diversified, a Kruskal–Wallis test also produced a non-significant effect (χ2(5) = 10.543, P = 0.061). Although the trends were somewhat consistent with the hypothesis (i.e. a U-shape pattern amongst the diversified subsample, but a much flatter scatter in the non-diversified sample; see Fig. 2), we stress that these results were non-significant.

The relationship between age bracket and burnout/wellbeing (BTI) in those who had (left) and had not diversified (right). Note: BTI refers to Burnout–Thriving Index, a measure of burnout and wellbeing (higher scores indicate greater wellbeing).

Workplace restrictions, including from micro-managing or financial targets, hampered participants’ ability to diversify. Some reported internal pressures in workplaces with ‘obstructive management’, ‘feeling isolated’, ‘lack of communication’, and ‘patient and personal expectations’. One commented that organisational setup meant ‘I continue to pay my share of practice expenses whether I am there or not.’

Feeling ‘time poor’ and ‘overcommitted’ in their workplaces prevented many from adding more roles, particularly with the threat of ‘feeling I am not doing any one job well enough’. Patient demands for timely appointments added to the ‘guilt’ of considering diversifying: ‘I cannot influence my booking due to the demands of the local community – meaning I end up doing more of what I do not quite enjoy’.

A lack of diversity in their mainstream work worsened this scenario, particularly if the GP developed a reputation in one area. This could mean they became ‘flooded with patients with these problems [leading]… to deskilling in the other areas’.

Although relationships could support diversification, they could also impede it. Many complained of insufficient networks to find opportunities, particularly if they were new to their location or sub-specialty. Others could be unsupportive of diversification due to ‘peer group ignorance’, ‘lack of vision’, ‘competitive work environment’, and ‘ridicule’, with one commenting that ‘people tell me I have given up by working outside of mainstream general practice’.

At the macro level, participants perceived attitudinal barriers, such as discrimination against gender, being part-time, or cultural background. The lack of government respect for general practice and the narrow socio-cultural norms of the role of a GP impeded the ability of some to ‘move off the treadmill’.

Bureaucratic and policy impediments included lack of government support, hospital accreditation, work visas, CPD requirements, Medicare rebates, and restrictive rurally bonded schemes. A ‘public and government that doesn’t understand GP [general practice]’ and the ‘inertia in governments, hierarchical behaviours that are wielding power and privilege without benefit to the community and often at great cost to the community’ were common themes.

Funding was another barrier. Many diverse roles reportedly attracted no government or organisational funding. Bulk-billing was a barrier to diversifying with vulnerable populations, as they tended to be more complex, needing more time and paperwork. Medicare requirements meant that ‘I end up seeing less patients per day and for longer consultations with challenging issues including a lot of non-billable work and that compromises my wellbeing, work-life balance and satisfaction with work’.

A common impediment was the perceived or actual lack of opportunities to diversify either because they were not ‘in the know or known to others’, or that ‘opportunities to diversify can be rather scarce unless you already have existing skills’. Most were ‘unaware who to turn to for career support and advice’. Similarly, there were no clear pathways to enter fields such as ‘academic medicine’.

The gradual restriction of general practice ‘often make[s] it difficult for GPs to maintain roles and skills that can be really important when things change [, the] specialist leaves or is on leave, covid comes along etc’. This has left a need for diversity, but without a trained workforce, especially in rural areas.

Many registrars thought that ‘the rigidity of the GP training program made it very difficult to diversify roles within training requirements’, either because they were ‘required to work in a certain area’ and were ‘studying for exams’, or the training did not include more diverse areas such as ‘leadership and management development’.

Location was important for many. Rural participants said there was a ‘lack of research capacity’, ‘too little time to diversify’, and that ‘most roles are urban based in leadership and management’ with expectations of travel for meetings, work, or training. Conversely, others complained of the lack of opportunities in urban areas.

The dominant theme within this category concerned costs they foresaw, arising from the need for training and upskilling, non-clinical hours, administration, planning, and networking. Many roles outside mainstream general practice reportedly ‘don’t offer equivalent financial rewards’ and hence ‘pursuing interests and passion has a financial toll’. For those who chose to volunteer, the financial costs were even greater.

Many feared losing patients if they decreased their mainstream work, or that their job would be more difficult. Some feared they would lose core skills and that they ‘could never go back to ‘true GP’ work’ or even a deeper fear of ‘letting go of my identity as a GP’. This was tied to the perceptions of others that a ‘proper GP’ works full-time in mainstream general practice.

Balancing the time required for different roles could make it difficult ‘to fit all the demands of all organisations’ as ‘many part-time roles for doctors expect more output than the time they allocate’. Some feared even less flexibility, as they would be an ‘employee’ with certain times for leave and more after-hours work.

Another fear was of greater workload on top of an already ‘overwhelming demand of General Practice’. This necessitated keeping abreast of more knowledge, ‘exhaustion and lack of time due to high load of study and paperwork’. Likewise, participants feared the greater administrative and bureaucratic load, which, when ‘… associated with fractional roles [,] becomes disproportionate’.

Some anticipated unacceptable risks such as ‘threat of litigation and high cost of medical defence’ for sub-specialties such as obstetrics and anaesthetics. Another risk was the unpredictability of future work in the diverse role and the closing of rural hospitals to GPs.

Although the COVID pandemic facilitated diversification for some, it also introduced or exacerbated many barriers. Some sub-specialties suffered, such as travel medicine, group work, surgical assisting, procedural work, or cosmetic medicine. The stress of COVID meant that GPs were doing ‘crisis management rather than [taking a] strategic approach to [their] career’ and ‘constant demands requiring reactions, decisions and leadership all with emotional burden’. ‘Less [opportunities] to meet new groups of doctors to discuss possible new ventures’, locuming, or travel for work impeded diversification and fuelled isolation.

Participants were ‘unable to teach face to face’, or forced to simultaneously manage their families at home and adapt to telehealth. Learning activities were limited or cancelled.

The risk of contracting or spreading COVID decreased the incentive to diversify for those who wanted to minimise exposure to people and ‘different sites’. Telehealth was described as a mixed blessing, but mostly led to ‘less diversity of practice’.

These barriers also sat within a context of increased clinical and administrative workload from COVID: ‘Covid19 has taken a big toll on the ability to diversify professional roles due to the immense need for clinical work and the changes imposed on other potential roles causing changes in education, supervision, meeting, collegiality’. GPs were ‘inundated with complex and mental health patients’ as patients ‘sav[ed] medical symptoms until they are multiple and often have worsened mental health.’

The pandemic largely undermined participants’ wellbeing – ‘personal relationships have suffered, and the unrelenting stress and pressure related to the pandemic’. Of the sample, 73.8% reported that their wellbeing was at least ‘slightly’ worse. Family illness or death, lack of exercise, disrupted sleep, and inability to socialise added to the discomfort of wearing PPE, clinical uncertainty, overwork, no holidays, and general fatigue. Dealing with aggressive patients, an unsupportive government, antivaxxers, and mask exemptions exacerbated the stress. Not seeing people face-to-face reduced work satisfaction, limited socialisation, reduced connection with patients and team, stopped access to in-person training and networking, reduced peer debriefing, increased difficulty establishing rapport with patients, restricted connections with new colleagues, and reduced quality time with family: ‘The face-to-face conversations and human connection are what makes it rewarding’.

Discussion

We explored professional diversification in relation to wellbeing amongst Australian GPs. Participants described diversification as supporting their wellbeing by supporting career sustainability. Diversification offered GPs professional variety, autonomy, and opportunities for growth and to work in areas of interest, enriching their professional relationships, enhancing their value fulfilment and workload feasibility, and enabling roles to complement one another. Although wellbeing was not statistically associated with diversifying, a positive relationship between the two was found, as diversification was associated with higher autonomy and value fulfilment, and both of these were associated with higher wellbeing (Prentice et al. 2023b). This evidence extends previous findings that implicate work-task meaningfulness in wellbeing (Shanafelt et al. 2009; Ko et al. 2020), and supports the notion that diversification can enhance career sustainability (Stevenson et al. 2011; Dwan et al. 2014; Eyre et al. 2014). More broadly, these findings are consistent with Maslach’s concept of ‘person–job fit’, a burnout prevention mechanism (Maslach et al. 2001).

However, these are nuanced findings, suggesting that diversification will not necessarily support GPs’ wellbeing. Rather, diversification appeared to be a vehicle for building GPs’ career sustainability that relies upon these mechanisms as ‘roads’. Those considering diversification as a wellbeing strategy need to articulate what ‘good’ diversification would look like for them, focusing on which mechanisms will support their wellbeing, how these mechanisms will be harnessed, and what professional roles will fulfil this.

This study mirrored a landmark finding that, amongst those who diversified, spending at least one-and-a-half days a fortnight in their most meaningful role halved their likelihood of burnout (Shanafelt et al. 2009). This suggests that diversification as a burnout inoculation strategy requires a relatively small time investment. Practically, this means that diversification could meet the criteria we established earlier for a burnout prevention strategy that does not exacerbate workforce shortages.

Deciding to diversify and defining what this looks like requires also exploring facilitators and barriers. The generalist nature of general practice makes GPs ideal candidates for a variety of roles. The qualitative data indicated the need for coordination between personal qualities, external supports, flexibility, and serendipity. This hypothesis was supported by quantitative analyses. Participants also discussed diversification barriers, both current individual and situational, and anticipated barriers. Many barriers mirrored facilitators, highlighting that efforts to promote diversification should focus on building enablers, which may simultaneously dismantle barriers.

These findings offer guidance for facilitating diversification. Certain individual factors (e.g. personal responsibilities) may contraindicate diversification. Conversely, most facilitators and barriers are amenable to organisational or systemic intervention, for example raising awareness of diversification opportunities, and developing more formalised pathways and communication regarding roles. Organisational accommodation of diversification during general practice training is important. Particularly given that burnout prevention appears feasible within one day a week, we contend that organisational support for diversification need not be threatening, and may in fact support workforce productivity and sustainability.

Limitations

Given the project focused upon professional diversification, it likely attracted those who had diversified or were interested in doing so. In light of the low response rate, this may have skewed the sample to those in favour of diversification. Since three of the researchers had diversified careers, there was the potential for bias in the interpretation of the results, though this should be offset against the volume of responses. Recruitment was confined to GPs, and it is unclear how applicable these findings are to other disciplines, hence we encourage further research in other specialties. Another limitation concerns the quantification of qualitative responses, which we undertook to facilitate triangulation between the data. This process yielded useful insights, but we acknowledge these findings as highly tentative and more research is required to more formally test them. Although providing demographic details was not mandatory and so prevented us from fully analysing the data, 1128 participants (97.5%) nonetheless provided these data and we maintain that affording participants the choice of whether to provide these details was important to maintain anonymity of responses. Finally, although gathering qualitative data via a survey collected a large amount of data, it also meant that responses sometimes lacked depth. The anonymity of responses also prevented us from further exploring or clarifying content. We therefore would welcome further research using interviews or focus groups to explore these ideas in greater depth.

Conclusion

In the context of a burnout epidemic and workforce crisis, there is an urgent need for solutions. This study indicates that professional diversification has the capacity to support the sustainability of GPs’ careers and thereby enhance their wellbeing without jeopardising workforce. The findings also highlight that diversification is only likely to be effective if GPs are deliberate in tailoring the strategy to suit their needs and context. We encourage organisations to support diversification, especially through publicising opportunities and accommodating requests to diversify.

Data availability

Due to the confidential nature of the data collected and potential risk of identifying participants, data are not publicly available.

Conflicts of interest

All authors began their employment with the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners after the project’s completion. The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners was not involved in the analysis of data.

Declaration of funding

This project was funded through the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners’ Harry Nespolon Foundation Grant.

References

Alarcon GM (2011) A meta-analysis of burnout with job demands, resources, and attitudes. Journal of Vocational Behavior 79, 549-562.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Australian Government, Department of Health and Aged Care (2020) Health Workforce Data. GP Medicare billing data – what does it say about current health workforce policy?. Available at https://hwd.health.gov.au/resources/data/gp-statistics-calendar-year-2020-commentary.pdf [Accessed 21 August 2023]

Bentley M, FitzGerald K, Fielding A, Moad D, Tapley A, Davey A, Holliday E, Ball J, Kirby C, Turnock A, Spike N, van Driel M, Magin P (2022) Provision of other medical work by Australian early-career general practitioners: a cross-sectional study. Journal of Primary Health Care 14, 333-337.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

BMJ Careers (2022) A day in the life of a portfolio GP. Available at https://www.bmj.com/careers/article/a-day-in-the-life-of-a-portfolio-gp [Accessed 21 August 2023]

Brooks J, McCluskey S, Turley E, King N (2015) The utility of template analysis in qualitative psychology research. Qualitative Research in Psychology 12, 202-222.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Dwan KM, Douglas KA, Forrest LE (2014) Are “part-time” general practitioners workforce idlers or committed professionals? BMC Family Practice 15, 154.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Eyre HA, Mitchell RD, Milford W, Vaswani N, Moylan S (2014) Portfolio careers for medical graduates: implications for postgraduate training and workforce planning. Australian Health Review 38, 246-251.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Gates R, Musick D, Greenawald M, Carter K, Bogue R, Penwell-Waines L (2019) Evaluating the Burnout-Thriving Index in a multidisciplinary cohort at a large academic medical center. Southern Medical Journal 112, 199-204.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Hamidi MS, Bohman B, Sandborg C, Smith-Coggins R, de Vries P, Albert MS, Murphy ML, Welle D, Trockel MT (2018) Estimating institutional physician turnover attributable to self-reported burnout and associated financial burden: a case study. BMC Health Services Research 18, 851.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Harris R (2021) Forty common values: a checklist. Available at https://drive.google.com/file/d/1xfWe8pCkDWeJ7rNcIFIukOMarra-HAZ8/view?fbclid=IwAR0BK511eOzEPdYWmZ5pevz1S6Z_62eEpZ4eC9x8s690RFEQx6r23bttQrQ [Accessed 9 May 2021]

Johnson RB, Onwuegbuzie AJ, Turner LA (2007) Toward a definition of mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research 1, 112-133.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ko SS, Guck A, Williamson M, Buck K, Young R, Residency Research Network of Texas Investigators (2020) Family medicine faculty time allocation and burnout: a residency research network of Texas study. Journal of Graduate Medical Education 12, 620-623.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Lundgren T, Luoma JB, Dahl JA, Strosahl K, Melin L (2012) The Bull’s-Eye Values Survey: a psychometric evaluation. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice 19, 518-526.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP (2001) Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology 52, 397-422.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Murray M, Murray L, Donnelly M (2016) Systematic review of interventions to improve the psychological well-being of general practitioners. BMC Family Practice 17, 36.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

O’Connor AB, Halvorsen AJ, Cmar JM, Finn KM, Fletcher KE, Kearns L, McDonald FS, Swenson SL, Wahi-Gururaj S, West CP, Willett LL (2019) Internal medicine residency program director burnout and program director turnover: results of a national survey. The American Journal of Medicine 132, 252-261.

| Google Scholar | PubMed |

Penwell-Waines L, Greenawald M, Musick D (2018) A professional well-being continuum: broadening the burnout conversation. Southern Medical Journal 111, 634-635.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Prentice S, Dorstyn D, Benson J, Elliott T (2020) Burnout levels and patterns in postgraduate medical trainees – a systematic review and meta-analysis. Academic Medicine 95, 1444-1454.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Prentice S, Elliott T, Dorstyn D, Benson J (2023a) Burnout, wellbeing and how they relate: a qualitative study in general practice trainees. Medical Education 57, 243-255.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Prentice S, Benson J, Need P, Pitot M, Elliott T (2023b) Personal value fulfillment predicts burnout and wellbeing amongst Australian General Practitioners. Journal of Workplace Behavioral Health 30, 1-17.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Rotenstein LS, Torre M, Ramos MA, Rosales RC, Guille C, Sen S, Mata DA (2018) Prevalence of burnout among physicians: a systematic review. JAMA 320, 1131-1150.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (2022) General practice: health of the nation 2022. Available at https://www.racgp.org.au/general-practice-health-of-the-nation-2022 [Accessed 31 July 2023]

Salvatore D, Numerato D, Fattore G (2018) Physicians’ professional autonomy and their organizational identification with their hospital. BMC Health Services Research 18, 775.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Shanafelt TD, West CP, Sloan JA, Novotny PJ, Poland GA, Menaker R, Rummans TA, Dyrbye LN (2009) Career fit and burnout among academic faculty. Archives of Internal Medicine 169, 990-995.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Stevenson AD, Phillips CB, Anderson KJ (2011) Resilience among doctors who work in challenging areas: a qualitative study. British Journal of General Practice 61, e404-e410.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Zhou AY, Panagioti M, Esmail A, Agius R, Van Tongeren M, Bower P (2020) Factors associated with burnout and stress in trainee physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Network Open 3, e2013761.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Özkan AH (2022) The effect of burnout and its dimensions on turnover intention among nurses: a meta-analytic review. Journal of Nursing Management 30, 660-669.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |