The aquatic plant communities of the Pilbara region of Western Australia: a region of arid zone wetland diversity

Michael N. Lyons A * , David A. Mickle A B and Michelle T. Casanova C D E

A * , David A. Mickle A B and Michelle T. Casanova C D E

A

B

C

D

E

Abstract

Decision making in conservation depends on robust biodiversity data. Well-designed systematic and rigorous surveys provide consistent and taxonomically broad datasets needed for conservation planning. This is important in areas such as the Pilbara of Western Australia with extensive mining and pastoralism. The collection of biodiversity data for aquatic plants represents a major contribution to assist in conservation planning and management of the region’s wetlands and rivers.

We documented the diversity and major patterns in the aquatic flora of Pilbara wetlands and rivers, to provide data to inform conservation planning and manage impacts of major land uses such as mining and pastoralism.

We undertook a systematic quadrat-based survey of the aquatic flora of 98 Pilbara wetlands and rivers. The full range of wetland types was sampled. Composition of charophytes and vascular aquatic plant communities were analysed against wetland permanence and water body type.

A diverse aquatic flora with several novel taxa was discovered. Charophytes were a major component of the aquatic flora. Floristic composition was strongly related to wetland type and water permanence with permanent sites showing higher richness. Less permanent sites captured a distinct component of the Pilbara aquatic flora.

The aquatic flora of the Pilbara represents a significant component of the region’s biodiversity. Patterning was concordant with previous studies of the riparian plant communities and aquatic invertebrates of the region providing synergies in reserve system design and management efforts.

High quality spatial biodiversity data particularly for poorly surveyed regions or biotic groups can provide major insights critical for effective conservation planning and management.

Keywords: aquatic plants, arid zone, biodiversity survey, charophytes, claypans, conservation planning, Pilbara, river pools, Western Australia, wetlands.

Introduction

Decision making in conservation is a knowledge-dependent process. Decisions associated with sustainable economic development, conservation estate design, land management, and management of threatened species and ecosystems are most effective when informed by adequate data describing spatial and temporal patterns in biodiversity, its ecological dependencies, and responses to threatening processes (Margules et al. 2002; Buxton et al. 2021; Hoffmann 2022).

Well-designed systematic and rigourous surveys of biodiversity provide internally consistent and taxonomically broad datasets for conservation planning at regional scales, that can then be contributed to larger data repositories at national (Belbin et al. 2021) and international (The Global Biodiversity Information Facility 2024) scales, expanding access to more comprehensive datasets on species diversity and distribution for conservation planning (Reichman et al. 2011). This is especially important in areas of competing land uses and where there are broadscale threats to biodiversity requiring informed management.

The Pilbara Region of north-western Western Australia constitutes one such area, with globally significant mineral resources and a recent history of extensive pastoralism (Booth et al. 2021). What little was known of the region’s biodiversity suggested a rich and endemic biota, but with a rapidly expanding resources sector it was also understood that knowledge of the region’s biodiversity was inadequate for regional conservation planning and environmental impact assessment (McKenzie et al. 2009). To inform impact assessment and landscape scale conservation planning, a comprehensive biological survey of the region was undertaken between 2003 and 2006 (McKenzie et al. 2009). This survey aimed to provide systematic survey data on the distribution of the terrestrial and aquatic biota across the region and use these data to identify gradients in community composition, the environmental factors related to these gradients, and to assess the adequacy of the existing reserve system (Gibson et al. 2015).

The Pilbara is an arid region with an abundance of aquatic habitats, many associated with discharge from numerous and extensive groundwater aquifers and with significant topographic variation. Wetlands in arid and semi-arid regions, with rainfall <500 mm per year, are frequently data deficient due to their remoteness from population centres, perceptions that they are not as threatened as wetlands in more populated temperate regions and because many such wetlands have water only temporarily. Australia is a continent dominated by semi-arid and arid landscapes, which support a wide diversity and very high number of wetlands, ranging from permanent springs and river pools, ephemeral rock holes and claypans to vast episodically filled salt lakes in palaeodrainages (Roshier and Rumbachs 2004; Duguid et al. 2005).

Wetlands are amongst the most threatened ecosystems globally (Dudgeon et al. 2006, Davidson and Finlayson 2018) partly due to their position in the landscape, which means they accumulate impacts from the broader catchments, and also because of their immense value for other human uses. Semi-arid and arid wetlands and their flora communities may be particularly sensitive to disturbance (Parra et al. 2021; Khelifa et al. 2022) due to climate-change effects in already dry regions (Scholes 2020), factors such as sedimentation from pastoral grazing in areas of of easily erodible catchment soils (Reid et al. 2017) and competition for limited and unreliable water (Jenkins et al. 2005).

Whilst many studies of the biotas of Australian arid zone wetlands have been undertaken at catchment to regional scales for a variety of biotic groups (e.g. Fensham et al. 2004; Kingsford et al. 2010; Casanova 2015; Timms 2022), regional scale studies of aquatic flora in Australia’s arid zones, which would assist in broad conservation planning and environmental impact assessment, are limited (Duguid et al. 2005; Hunter and Lechner 2018; Rossini et al. 2018) or of limited taxonomic scope (e.g. Costelloe et al. 2005).

This paper aims to document the diversity and major patterns in the aquatic flora of Pilbara wetlands and rivers. The current study complements previous analyses of the riparian plant communities and aquatic invertebrate fauna from the survey (Pinder et al. 2010; Lyons 2015). Importantly, the current study includes charophytes in addition to vascular plants; a group that has not been included in regional scale surveys in Western Australia previously.

Study area

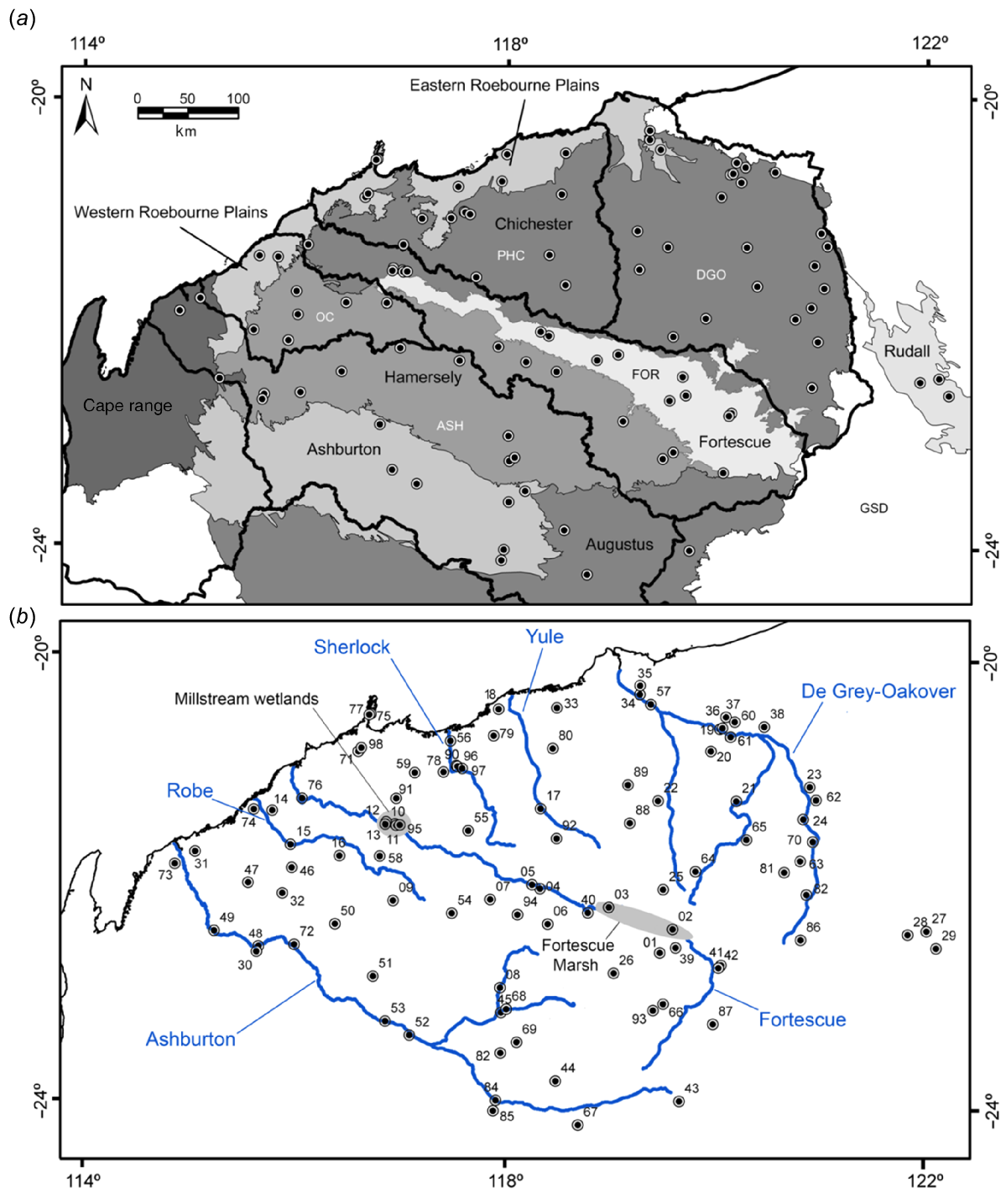

The Pilbara region, as defined in this study represents an area of approximately 180,000 km2, bounded to the south by the Ashburton River and to the east by the De Grey-Oakover River system. A small number of wetlands were also sampled in the Karlamilyi National Park to the east of the main study area (Fig. 1). The study area includes the entire Pilbara biogeographic region (Thackway and Cresswell 1994) and small areas of the adjoining Gascoyne and Little Sandy Desert regions.

Maps of the Pilbara study area showing the 98 wetland sites sampled. (a) The Pilbara biogregion and its four sub-regions (shaded grey with full names) (IBRA6.1): (1) Roebourne Plains (eastern and western); (2) Chichester; (3) Fortescue; and (4) Hamersley. Drainage basin boundaries are outlined in black and labelled with abbreviated names: ASH, Ashburton; OC, Onslow Coast; FOR, Fortescue; PHC, Port Hedland Coast; DGO, De Grey-Oakover; GSD, Great Sandy Desert. (b) Main rivers (blue lines) and two major wetlands (grey shaded) of the Pilbara region (taken from Lyons 2015). The sampled wetland sites are numbered as described by Lyons (2015).

The Pilbara region includes two bioclimatic zones: semi-desert tropical in western coastal areas and desert in the central and eastern area (Beard 1990). Rainfall in the region averages 290 mm, dominated by summer precipitation associated with tropical low-pressure systems and is spatially and inter-annually highly variable. Major cold fronts from the south produce winter rainfall concentrated along the coast and central ranges but rarely extending to the east of the region. At least one cyclone traverses the region in a normal summer and others pass close by along the coast. They supply half of the average annual rainfall.

The Pilbara region is characterised by extensive rocky landscapes including the dominant Hamersley and Chichester Ranges. Major aquifer systems are associated with these landscapes, discharging to form springs and supporting permanent pools in rivers, gorges, and creeks. The Western Coastal Plain and central and upper Fortescue River Valley lowlands support an array of claypans, clay flats and turbid creeks.

Mining and pastoral industries dominate the region’s land use. Given the regions extensive aquifer systems, mining typically requires pit dewatering and associated discharge, with associated risks to springs and river pools from dewatering, and disturbance to hydroperiods where discharges occur within rivers and creeks (Eckersley et al. 2024). Grazing pressure and soil disturbance from trampling is a known risk to riparian zone condition (Lyons 2015). Water quality is also impacted from cattle that increase nutrient levels, degrade riparian vegetation and increase turbidity. Wetlands are particularly vulnerable in dry seasons where cattle congregate at a more restricted set of natural water sources.

Materials and methods

Site selection

The primary sampling stratification employed in study was the a priori designation of several wetland types based on hydrological and morphological attributes. These included springs, river pools and creeks (both naturally turbid and clear), claypans, salt marshes, gorge pools, and rock holes. A total of 98 wetlands were selected to include the diversity of wetland types present within each of the five major drainage basins within the Pilbara (Fig. 1). A detailed description of the site selection process is provided by Lyons (2015).

Sampling

Within each of the selected wetlands, sampling was undertaken within a defined reach herein referred to as a site. Sites were sampled over a 3-year period from 2003 to 2006, each being sampled on two occasions corresponding to early dry season (April/May) and August/September, but not necessarily in the same year. A small number of sites were sampled in summer following early wet season cyclonic fill events. Ephemeral wetlands did not always fill in both seasons with 11 such sites sampled only once. On each sampling occasion sites were sampled using two 50-m × 2-m transects placed to include the dominant aquatic habitats of each site. At some sites, typically ephemeral and seasonally inundated wetlands, the flora present included non-macrophytes (e.g. inundation tolerant emergent perennials). These were included in the species lists. Most wetlands showed significant depth variation such that transects were placed to capture the shallow margin and deeper central channel or basin, and typically ran parallel to the wetland axis for channelised sites. For sites such as rock pools and small claypans where the total wetland area was less than 200 m2 the entire wetland was sampled. Each transect was searched with all taxa collected. At deeper sites (ca. 1–2 m) mask and snorkel was used to sample transects. Specimen plant material was pressed and for delicate vascular material and all algal taxa duplicate material was preserved in 70% ethanol. Sediment seed-bank collections were made by bulking six 50-mm diameter × ~100-mm deep sediment cores from six scattered locations from drying banks and shallow edges at each site. This material was air dried, and subsequently rehydrated following the methods outlined by Casanova (2015). Cultured material was used to facilitate the identification of Charophytes where field collected specimens were sexually immature. Water and sediment samples were collected and analysed following the methods outlined by Pinder et al. (2010). Sites were allocated one of four hydroperiod/permanence classes (1 = ephemeral; 2 = seasonal episodic; 3 = near permanent; 4 = permanent) following the scheme developed by Pinder et al. (2010).

Non-charophyte identifications were undertaken by comparison to collections held at the Western Australian Herbarium. Several groups, particularly Najas were difficult to consistently identify using available taxonomic treatments (e.g. Triest 1988). Closely related taxa that could not be resolved across the entire data set were amalgamated for the purposes of multivariate analyses (e.g. Marsilea) (Table 1). The conservation status and current distribution of taxa were obtained from relevant floras and online resources (AVH 2024; Western Australian Herbarium 2024).

| Taxon | Conservation code | Distribution/status | Class | Functional group | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characeae | |||||

| Chara ?aridicola Casanova & Karol | Northern Australia semi-arid to tropics NT and SA | S | S | ||

| Chara benthamii A. Braun | Tropics | S | S | ||

| Chara braunii S. G. Gmel. | Cosmopolitan | S | S | ||

| Chara behriana (A. Braun) F. Muell. ex Casanova & Karol | Cosmopolitan | S | S | ||

| Chara globularis Thuill. | Cosmopolitan | S | S | ||

| Chara lucida (A. Braun) Casanova & Karol | Tropical Australia and New Guinea | S | S | ||

| Chara muelleri (A. Braun) A. Braun | Widespread in temporary wetlands | S | S | ||

| Chara porteri Casanova | Northern Australia semi-arid to tropics | S | S | ||

| Chara protocharioides Casanova & Karol | WA | S | S | ||

| Chara setosa Kl. ex Willd. | Rare, scattered tropics | S | S | ||

| Chara sp. nov. (aff. fibrosa 1) | Putative new taxon | S | S | ||

| Chara sp. nov. (aff. fibrosa 2) | Putative new taxon | S | S | ||

| Chara sp. nov (aff. globularis) (M. N. Lyons & D. A. Mickle 3218) | Putative new taxon | S | S | ||

| Chara wightii (A. Braun) Casanova | Tropics | S | S | ||

| Chara vulgaris var. gymnophylla (A. Braun) Nym. | First record from northern Australia | S | S | ||

| Chara zeylanica Klein ex Willd | Widespread tropics | S | S | ||

| Genus et sp. nov. (M. N. Lyons and D. A. Mickle 3080) | New taxon only known from Weelarana Salt Lake | S | S | ||

| Lamprothamnium macropogon (A. Braun) Ophel | Widespread | S | S | ||

| Lamprothamnium stipitatum Casanova | Known from Weelarana Salt Lake, Pilbara and single record NT | S | S | ||

| Nitella congesta (R.Br.) A. Braun | Scattered Australian records | S | S | ||

| Nitella gelatinifera var. microcephala (A. Braun) J.C. van Raam | WA | S | S | ||

| Nitella heterophylla (A. Braun) A. Braun | Arid and semi-arid northern Australia | S | S | ||

| Nitella hyalina (DC.) Ag. | Cosmopolitan | S | S | ||

| Nitella micklei Casnaova | Northern arid zone Australia | S | S | ||

| Nitella sp. 1. aff orientalis (M. N. Lyons and D. A. Mickle 3057) | Putative new taxon | S | S | ||

| Nitella sp. 2. aff orientalis T. F. Allen (M. N. Lyons and D. A. Mickle 3054) | Putative new taxon | S | S | ||

| Nitella sp. nov. ‘papillate’ (N. Gibson & D. A. Mickle 4541) | Putative new taxon | S | S | ||

| Nitella sp. aff. cristata (M. T. Casanova PBS63) | Putative new taxon | S | S | ||

| Nitella sp. nov. ‘verrucate’ (M. T. Casanova PBS7) | Putative new taxon | S | S | ||

| Nitella ungula A.Garcia | Eastern Australia | S | S | ||

| Nitella ungula/heterophylla | S | S | |||

| Amaranthaceae | |||||

| Alternanthera angustifolia R.Br. | Tropical arid | T | Tda | ||

| Aponogetonaceae | |||||

| Aponogeton queenslandicus | Sub-tropical and eastern Australia, Pilbara outlier | A | ARf | ||

| Arecaceae | |||||

| Livistona alfredii F. Muell. | P4 | Pilbara, outlier at Cape Range WA | T | Tdr | |

| Asteraceae | |||||

| Pluchea rubelliflora (F. Muell.) B. L. Rob. | Widespread arid to tropical Australia | T | Tda | ||

| Campanulaceae | |||||

| Lobelia quadrangularis R.Br. | Tropics Pilbara outlier | A | ATl | ||

| Chenopodiaceae | |||||

| Tecticornia pergranulata subsp. pergranulata (J.M.Black) K. A. Sheph. & Paul G. Wilson | Southern Australia | A | ATe | ||

| Tecticornia verrucosa Paul G. Wilson | Kimberley south SW WA, SA, and NT | A | ATe | ||

| Convolvulaceae | |||||

| Cressa australis R.Br. | Scattered tropical arid and SE Australia | T | Tda | ||

| Ipomoea aquatica Forssk. | SE Asia and tropical Australia, Pilbara outlier | A | ATl | ||

| Cyperaceae | |||||

| Cladium procerum S. T. Blake | P2 | Eastern and SE near coastal, Pilbara major outlier | T | Tda | |

| Cyperus bulbosus Vahl | Australia wide non temperate inland | T | Tda | ||

| Cyperus difformis L. | Australia wide non temperate inland | T | Tda | ||

| Cyperus iria L. | Non temperate Australia | T | Tda | ||

| Cyperus vaginatus R.Br. | Australia widespread | A | ATe | ||

| Eleocharis geniculata (L.) Roem. & Schult. | Tropical subtropical and central Australia | A | ATe | ||

| Eleocharis pallens S. T. Blake | Eastern Australia Pilbara/Gascoyne WA outliers | A | ATe | ||

| Eleocharis papillosa Latz | Tropical and central Australia few records | A | ATe | ||

| Eleocharis ?sphacelata R.Br. | Eastern and tropical north Australia Pilbara outlier | A | ATe | ||

| Fimbristylis cephalophora F. Muell. | Tropical Australia Pilbara outlier | A | ATe | ||

| Fimbristylis ferruginea Vahl | Northern and eastern Australia scattered inland | A | ATe | ||

| Fimbristylis sieberiana Kunth | P3 | Northern Australia scattered inland | A | ATe | |

| Schoenoplectus dissachanthus (S. T. Blake) J. Raynal | All mainland states (summer rainfall) | A | ATe | ||

| Schoenus falcatus R.Br. | Northern and central Australia | T | Tda | ||

| Schoenoplectus laevis (S. T. Blake) J. Raynal | Northern Australia | A | ATe | ||

| Schoenoplectus subulatus (Vahl) Lye | Northern and central Australia, Murray Darling and east coast | A | ATe | ||

| Elatinaceae | |||||

| Bergia perennis (F. Muell.) Benth. | Arid and subtropical Australia | T | Tda | ||

| Bergia perennis subsp. obtusifolia G. J. Leach | Widespread western arid zone of Australia | T | Tda | ||

| Eriocaulaceae | |||||

| Eriocaulon cinereum R.Br. | Asia, Africa tropical Australia Pilbara outliers | A | ATl | ||

| Fabaceae | |||||

| Aeschynomene indica L. | Tropical and arid zone | T | Tda | ||

| Frankeniaceae | |||||

| Frankenia ambita s.l. Ostenf. | Pilbara and southern Kimberley coastal scattered inland | T | Tdr | ||

| Goodeniaceae | |||||

| Goodenia lamprosperma F. Muell. | Northern Australia | A | ATe | ||

| Haloragaceae | |||||

| Myriophyllum decussatum Orchard | Northern range limit in survey area | A | ARp | ||

| Myriophyllum verrucosum Lindl. | Widespread Australia | A | ARp | ||

| Hydrocharitaceae | |||||

| Najas graminea Delile | Cosmopolitan | S | S | ||

| Najas marina L. | Cosmopolitan | S | S | ||

| Najas pseudograminea W. Koch | SE Asia, Australia | S | S | ||

| Najas tenuifolia R.Br. | Northern Australia | S | S | ||

| Vallisneria annua S. W. L. Jacobs & K. A. Frank | Tropical Australia | S | S | ||

| Vallisneria nana R.Br. | Northern Australia isolated southern records | S | S | ||

| Vallisneria sp. Weelarrana (M. N. Lyons & S. D. Lyons 3050) | Weelarrana Salt Lake | S | S | ||

| Lentibulariaceae | |||||

| Utricularia gibba R.Br. | Cosmopolitian | A | ARp | ||

| Lythraceae | |||||

| Ammannia baccifera L. | Northern Australia | T | Tda | ||

| Ammannia multiflora Roxb. | Tropical arid and SE Australia | T | Tda | ||

| Rotala diandra (F. Muell.) Koehne | Northern Australia | A | ARp | ||

| Rotala mexicana Cham. & Schltdl. | Cosmopolitan warm regions | A | ARp | ||

| Marsileaceae | |||||

| Marsilea exarata A. Braun | Australia sub tropics and arid zone | A | ARp | ||

| Marsilea hirsuta R.Br. | Widespread Australia | A | ARp | ||

| Menyanthaceae | |||||

| Nymphoides indica (L.) Kuntze | Pilbara outlier, tropics and subtropical east coast | A | ARf | ||

| Myrtaceae | |||||

| Eucalyptus camaldulensis var. obtusa Blakely | Western third of Australia not SW | A | ATe | ||

| Eucalyptus victrix L. A. S. Johnson & K. D. Hill | Sub-tropical arid WA and NT | A | ATe | ||

| Melaleuca argentea W. Fitzg. | Tropics | A | ATe | ||

| Melaleuca bracteata F. Muell. | Pilbara disjunct east coast arid zone and tropics of Australia | A | ATe | ||

| Melaleuca glomerata F. Muell. | Central Australia and arid/semi-arid WA | A | ATe | ||

| Melaleuca linophylla F. Muell. | Pilbara near endemic | A | ATe | ||

| Phrymaceae | |||||

| Thyridia sp. northern saline floodplains (A. Markey & S. Dillon FM 10730) | Western arid and semi-arid parts of WA | A | ARp | ||

| Peplidium aithocheilum W. R. Barker | Central Australia Arid and semi-arid WA | T | Tda | ||

| Peplidium muelleri s.l. Benth. | Central Australia and WA arid zone | A | ARf | ||

| Peplidium sp. E Evol. Fl. Fauna Arid Aust. (A.S. Weston 12768) | Pilbara and adjacent bioregions | T | Tda | ||

| Plantaginaceae | |||||

| Stemodia viscosa Roxb. | Northern WA and NT | T | Tda | ||

| Plumbaginaceae | |||||

| Muellerolimon salicorniaceum (F. Muell.) Lincz. | West coastal and inland saline systems WA | A | ATe | ||

| Poaceae | |||||

| Chloris pectinata Benth. | Subtropical arid | T | Tda | ||

| Eragrostis elongata (Willd.) J. Jacq. | Australia widespread | T | Tda | ||

| Eragrostis leptocarpa Benth. | Arid zone and isolated records tropics | T | Tda | ||

| Eragrostis tenellula (Kunth) Steud. | Northern Australia non temperate | A | ATe | ||

| Eriachne benthamii s.l. Hartley | Arid zone and scattered in tropics | A | ATe | ||

| Eulalia aurea (Bory) Kunth | Northern Australia | T | Tda | ||

| Leptochloa fusca subsp. fusca (L.) Kunth. | Widespread Australia | A | ATe | ||

| Leptochloa fusca subsp. muelleri (Benth.) N. Snow | Arid zone Australia | A | ATe | ||

| Phragmites karka (Retz.) Steud. | Tropical and central Australia | A | ATe | ||

| Pseudoraphis spinescens (R.Br.) Vickery | Northern and eastern Australia Pilbara outlier | A | ATe | ||

| Sporobolus australasicus Domin | Northern and central Australia | A | ATe | ||

| Sporobolus ramigerus (F. Muell.) P. M. Peterson, Romasch & R. L. Barrett | Arid semi-arid southern Australia | A | ATe | ||

| Polygonaceae | |||||

| Persicaria attenuata x glabra | Isolated records Kimberley and Pilbara | A | Ate | ||

| Potamogetonaceae | |||||

| Althenia hearnii T. Macfarlane & D. D. Sokoloff | Southern WA Pilbara outlier | S | S | ||

| Stuckenia pectinatas (L.) Börner | Cosmopolitan | S | S | ||

| Potamogeton crispus L. | Cosmopolitan | S | S | ||

| Potamogeton tepperi A. Benn. | Northern Australia | S | S | ||

| Pteridaceae | |||||

| *Ceratopteris thalictroides (L.) Brongn. | Tropical cosmopolitan | A | ARp | ||

| Ruppiacea | |||||

| Ruppia polycarpa R. Mason | Widespread in western and southern Australia | S | S | ||

| Typhaceae | |||||

| Typha domingensis Pers. | All Australian states tropical and warm world | A | ATe | ||

Conservation codes refer to the priority species codes of the Western Australian Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions. Functional groups and classes follow those of Brock and Casanova (1997). Class: S, submerged; A, amphibious; T, terrestrial. Functional group: S, submerged; ARf, amphibious fluctuation responder – floating/stranded; ARp, amphibious fluctuation responder – morphologically plastic; ATe, amphibious fluctuation tolerators – emergent; Tda, terrestrial – damp places; Tdr, terrestrial – dry places. Quoted collection numbers refer to voucher specimens lodged at PERTH.

Charophyte identifications were undertaken following the approach outlined in Casanova (2005, 2009) and coincided in time with an extensive examination of herbarium collections including type material. This work (Casanova 2005, 2009, 2013) provided an overview of the current state of the taxonomy of Australian Chara, Lamprothamnium, and Nitella. Subsequently, taxonomic treatments have been completed (Casanova and Porter 2013; Casanova and Karol 2023a, 2023b). Representative vouchers are lodged at PERTH. Identified taxa were classified according to the functional type scheme developed by Brock and Casanova (1997).

Data analysis

Presence absence data was compiled for samples (seasonal data), and for sites by combining seasonal samples. Herein, these two data sets are referred to as samples and sites. Compilation of the sample data provided the opportunity to analyse substrate and water chemistry data that was collected at each seasonal visit (see Pinder et al. 2010). Resemblance matrices were generated for samples and sites using the Bray-Curtis similarity measure in Primer 7 (Clarke and Gorley 2015). The influence of singleton species (species with a single sample or site occurrence) was assessed by comparing resemblance matrices including and excluding singletons utilising Primer’s RELATE routine (999 permutations). For both samples and sites, singletons vs full matrices were highly correlated (rho = 0.99, P < 0.001). While normal practice would remove singletons, they were retained in subsequent analyses given their exclusion would remove several species from already species poor samples and sites from the data set. In generating the sample and site resemblance matrices a dummy variable (value 1) was added following the rationale outlined in Clarke et al. (2006). In this instance, several shallow and often turbid ephemeral wetlands were naturally depauperate rather than the product of under sampling or disturbance.

Site analysis

Analysis of sites was completed in Primer (Clarke and Gorley 2015). A site by species resemblance matrix was generated using the Bray Curtis similarity measure. UPGMA (unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean) cluster analysis was performed using the flexible beta routine (beta = −0.1). Significant clusters were identified using the SIMPROV routine (significance 5%). The SIMPER routine was undertaken to identify species providing discrimination between the identified clusters. Analysis of similarity (ANOSIM) routines were used to examine the significance of relationships between the floristic composition of sites with wetland type, and permanence. For interpretation categorical variables were overlain on non-metric multidimensional scaling (nMDS, 50 starts) ordinations (Clarke and Gorley 2015). Two-dimensional ordinations were used where they showed similar stress to 3D plots.

Sample analysis

The BEST/BIOENV procedure in PRIMER was used to explore the relationship between site compositional similarity and environmental attributes. This module uses Spearman’s rank–order correlation to match distances in a site’s association matrix to Euclidean distances among each of its environmental attributes. Continuous variables used in the analysis included chemical and textural attributes of the soil collected by Pinder et al. (2010). For pairs of variables that were highly intercorrelated (P > 0.9), a single variable was retained. Highly skewed variables were log-transformed, and the resulting variable matrix normalised.

Results

Flora

A total of 111 taxa were recorded during the survey (Table 1) including charophytes (31 taxa), ferns/fern allies (2 taxa),and flowering plants (78 taxa). Several closely related taxa could not be identified consistently across all samples (due to sterile material or poor available taxonomy) and were amalgamated for the analyses of site/sample data. After the Characeae (28% of taxa), Cyperaceae, Poaceae, and Hydrocharitaceae were the dominant families. A single naturalised aquatic species, Ceratopteris thalictroides was recorded from the Millstream delta (PSW011).

Species richness

Ten out of a total of 97 sites did not have any taxa recorded from within the water body. Where wetland species were recorded, sample richness ranged from 1 to 14, with a mean of 5.6 ± 0.25. Site richness (combining sites sampled in two seasons) ranged from 1 to 23, and averaged 9.9. Species occurring in at a single site (singletons) represented 32% of the flora with those occurring at only two sites (doubletons) being 16% of the recorded taxa. Species richness increased with water body permanence and correspondingly with a priori wetland type.

Site classification

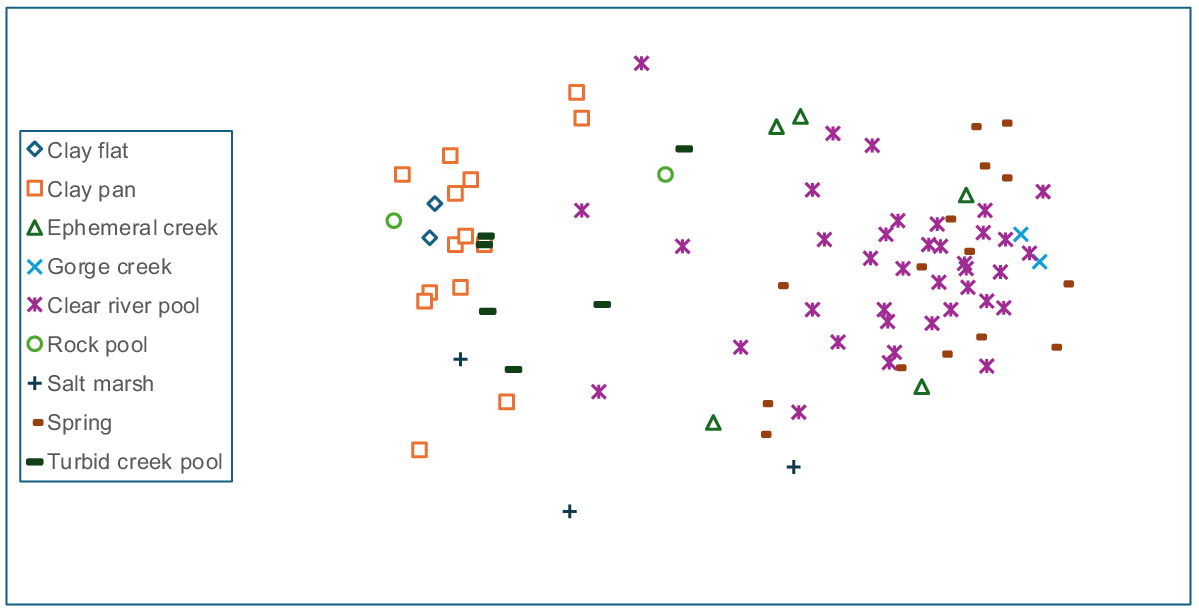

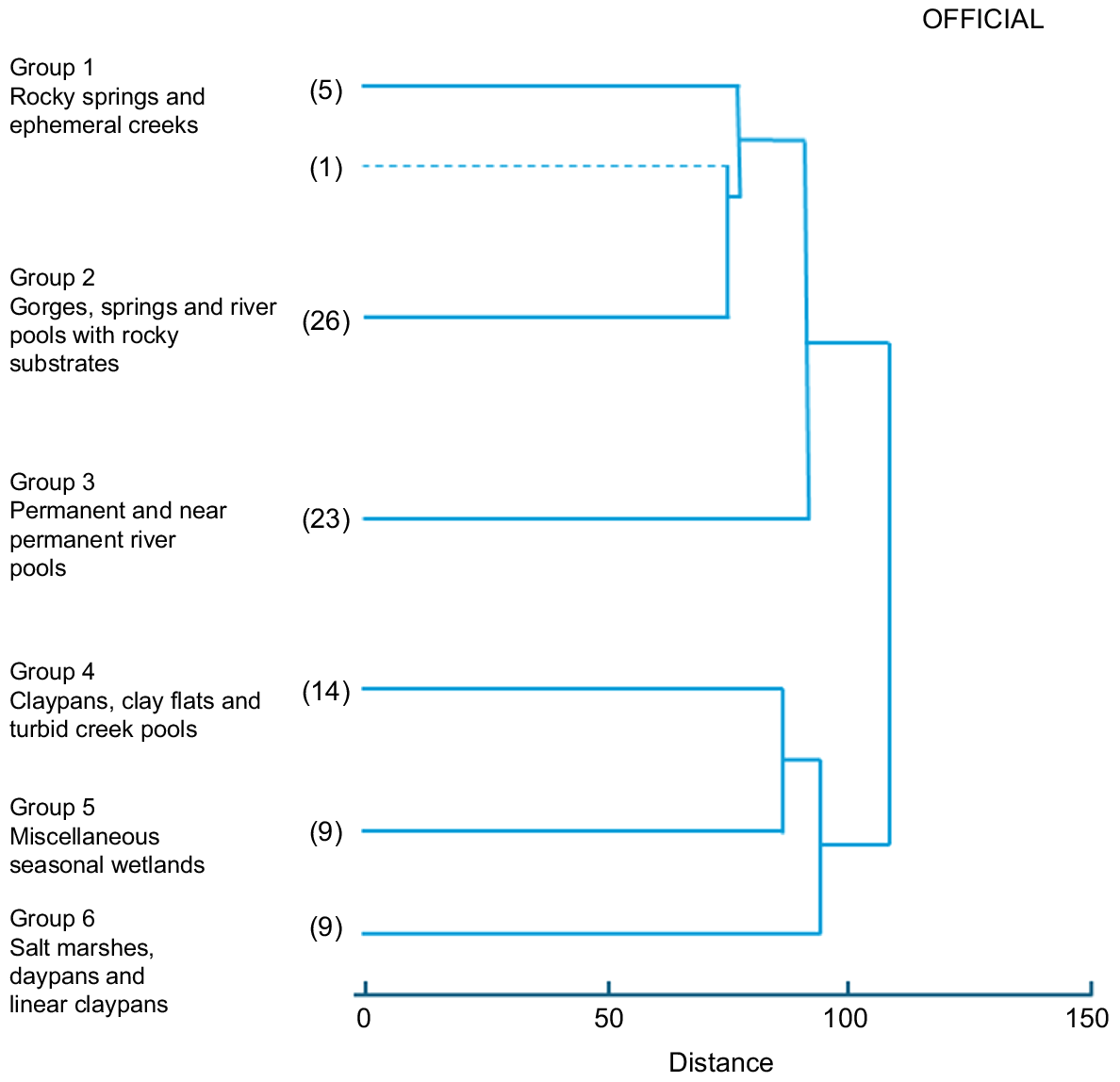

Six site groups were recognised from the cluster analysis with a single site forming an artifactual ‘group’. The classification revealed a primary division between mostly riverine (river pools, gorge creeks, springs, ephemeral creeks), and non-riverine wetlands (claypans, marshes, and turbid creek pools) (Fig. 2). The frequency of occurrence of the a priori wetland types for each of the floristic groups is in Table 2.

Dendrogram showing classification of 87 survey sites (UPGMA) at the six-group level. Dotted line denotes an artifactual site.

| Floristic group | Clay flat | Claypan | Ephemeral creek | Gorge creek | Clear river pool | Rock pool | Salt marsh | Spring | Turbid creek pool | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Rocky springs and ephemeral creeks | 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 2. Gorges, springs and river pools with rocky substrates | 2 | 16 | 8 | |||||||

| 3. Permanent and near permanent river pools | 1 | 18 | 4 | |||||||

| 4. Claypans, clay flats and turbid creek pools | 2 | 9 | 1 | 2 | ||||||

| 5. Miscellaneous seasonal wetlands | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 6. Salt marshes, claypans and linear claypans | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 |

Small shallow pools in rocky shallow springs and a single ephemeral creek, characterised by emergent taxa such as Eleocharis geniculata, Lobelia arnhemiaca, Typha domingensis, Eleocharis geniculata, Schoenus dissacanthus, and Fimbristylis sieberiana, with the near absence of submerged aquatics. Average species richness was 10 species per site with an average permanence score of 3.2.

This group included many sites with submerged aquatics distinguishing the group from Group 1. Significant taxa from the SIMPER analysis included Schoenus subulatus, Typha domingensis, Najas marina, Potomogeton tepperi, Chara zeylanica, and Cyperus vaginatus. The group includes a discrete cluster of six springs and spring fed gorge creeks including Palm Spring at Millstream, Fortescue Falls, and Hamersley Gorge. Average species richness was seven taxa per site with an average permanence score of 3.7.

A large group of 23 river pools with Schoenus subulatus, Chara wightii, Najas marina, Nitella hyalina, and Nitella congesta as significant taxa from the SIMPER analysis. The low abundance of wetland fringing taxa including Typha domingensis and Cyperus vaginatus distinguishes the group from Group 3 above (average group dissimilarity 67.05). Average species richness was 11 species per site with an average permanence score of 3.2.

A group of ephemeral and seasonal wetlands with Eriachne benthamii s.l. and Marsilea spp. as distinguishing taxa. The group includes a variety of claypan types that typically fill seasonally (average permanence class 2.1). The sites were often turbid with low average species richness (2.6 taxa per site).

A heterogeneous group of seasonal wetlands (average permanence score 2.1) that included pools in seasonal creeks, shallow river pools and non-turbid claypans/flats. Average site similarity for the group was low (23.66). Najas graminea s.l., Chara porteri, and Marsilea spp. were significant taxa defining the group. The group includes a distinctive group of non-turbid claypans in the east of the study area with almost complete beds of Marsilea with Chara porteri as the dominant aquatic. Average species richness was 7.9 taxa per site.

A very heterogeneous group of wetlands with low average group similarity (16.53). Significant species were Nitella heterophylla and Nitella micklei. Average species richness was 5.6 taxa per site. The group includes two sites sampling the flooded margins of Fortescue Marsh.

Community composition and categorical variables

Anosim analysis of both site and sample ordinations for wetland type (Figs 3 and 4) showed significant differences between several wetland types (samples: global R = 0.503, P < 0.001; sites: global R = 0.55, P < 0.001). For both seasonal and site data, clear river pools, springs, and to a lesser extent ephemeral creeks were separated from claypans, rock pools, turbid pools, and salt marshes. Claypans were the most compositionally heterogeneous group albeit species poor. For both sites and samples, pairwise anosim results between wetland types provided little support (low r-values) for compositional differences between turbid pools and claypans, river pools and springs, and ephemeral creeks and springs.

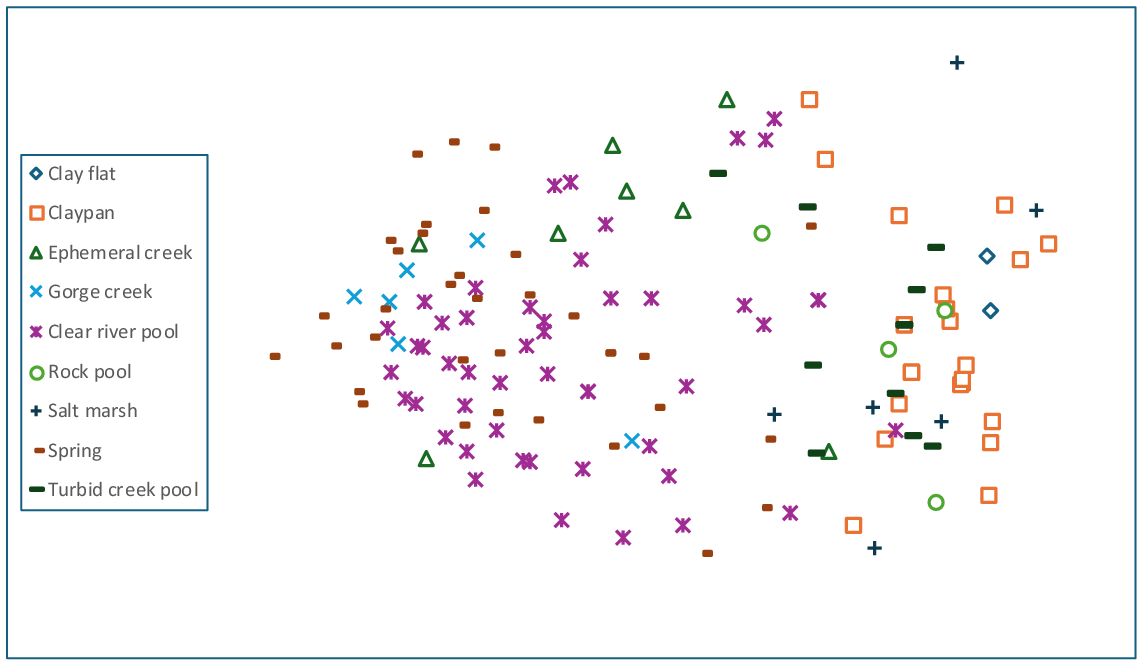

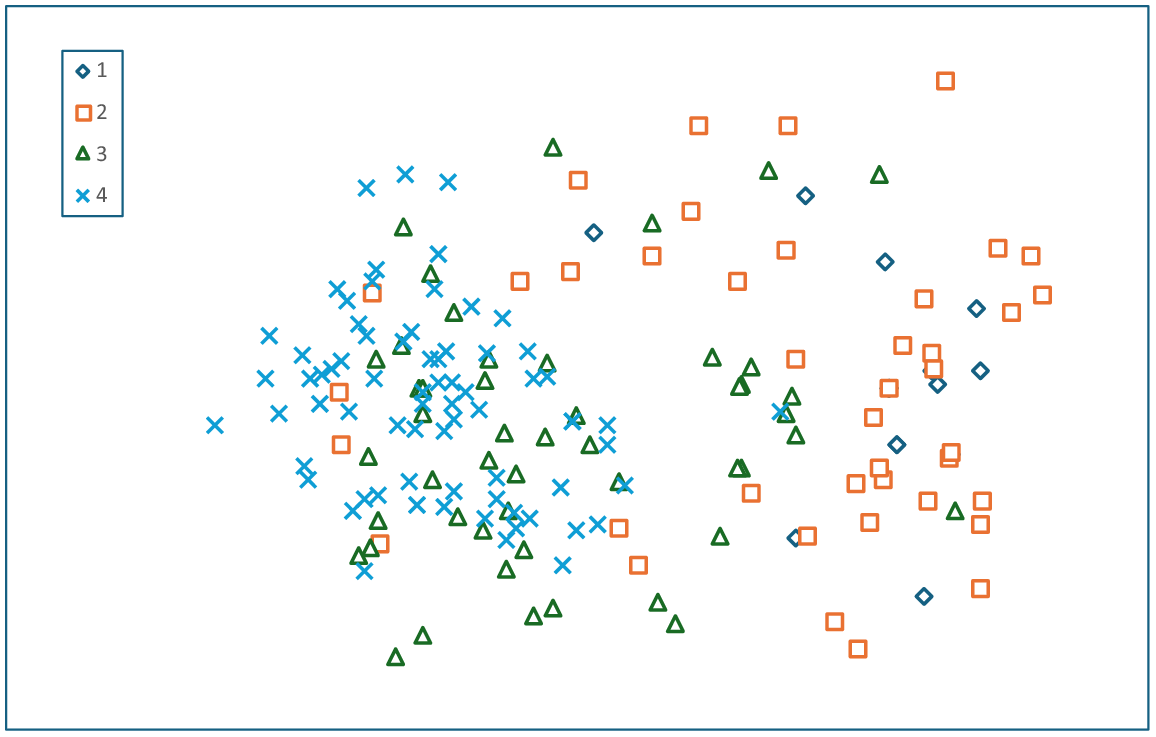

Anosim analysis and interpretation of nMDS ordination plots revealed differences in community composition with assigned hydroperiod/permanence classes for both site and sample resemblance matrices (Figs 5 and 6) (site: r = 0.368; sample: r = 0.384, P < 0.001). Pairwise tests for both site and sample data showed very similar results, with differences largely driven by significant differences (P < 0.001) between near permanent/permanent classes, compared to ephemeral/seasonal classes. Anosim results revealed no significant compositional difference between ephemeral and seasonal classes (r-values < 0.05, P > 0.2), although near-permanent and permanent classes showed significant yet weak compositional separation (r-values < 0.17, P < 0.001). Since hydroperiod class was strongly aligned with wetland types (e.g. claypans were all ephemeral or seasonal), and river pools and springs were largely near-permanent or permanent, hydroperiod class and composition was examined within the major groups identified from the anosim analysis of wetland types (see above). For riverine sites and samples (excluding turbid creek pools), compositional differences were relatively weak but significant between seasonal and permanent classes (site: pairwise r = 0.407; sample: pairwise r = 0.588, P < 0.001). Combined analysis of claypans, turbid pools and salt marshes showed no compositional relationship with hydroperiod classes.

Within wetland types, anosim tests of autumn vs spring samples revealed little compositional separation with season. Of the wetland types, only river pools showed significantly different richness in spring (7.0 ± 2.8) vs autumn (5.4 ± 2.6) (P<0.05).

Comparison of the resemblance matrices (using the RELATE routine in Primer) for autumn vs spring samples (for sites visited in both seasons) showed a significant rank correlation (Spearman) between the seasons (rho = 0.595, P < 0.001) suggesting that sites are relatively compositionally stable between seasons.

Sample data and environmental variables

A combination of five variables, Dep Inv (an estimate of water depth), Total Alkalinity, %meq mg, %meq K, and Gravel provided the highest correlation with the sample similarity matrix based on the BEST routine (Sperman’s rho = 0.436). The inclusion of water depth (Dep Inv) reflects the major compositional separation of deeper riverine wetlands from shallow less permanent wetlands such as claypans as seen in the site analysis. Water chemistry variables were more difficult to interpret. Total alkalinity, %meqMG, and %meq K possibly reflect the contribution of weathering products in ground waters and within major drainage catchments to water column chemistry within river pools and springs vs the small catchment and incipient rainfall filling of shallow and less permanent wetlands. Gravel was also included but did not increase the value of Spearman’s rho.

Discussion

Our survey was one of the few to have systematically documented aquatic plants across an entire region, especially when combined with a study of the region’s riparian flora (Lyons 2015). We recorded 111 aquatic and amphibious taxa in the current study with charophytes representing a third of species documented. The flora includes taxa with extensive Australian tropical and arid-zone distributions (e.g. Vallisneria annua, Najas tenuifolia, Chara zeylanica) and taxa with very broad Australian distributions (e.g. Myriophyllum verrucosum, Najas marina, Nitella hyalina). These distributions largely exclude the sandy deserts that occur to the north and east of the study area, in which suitable aquatic habitats are rare or absent. The Pilbara also represents a large yet disjunct part of the distributions of numerous taxa (e.g. Najas spp.). Other taxa recorded represent major range disjunctions from the Kimberley, and elsewhere in northern Australia (e.g. Pseudoraphis spinescens, Ipomoea aquatica, Eriocaulon cinereum). Myriophyllum decussatum represents one of the few taxa with a south-western semi-arid distribution, with collections made during the survey representing a major northerly range extension. The record of Sporobolus ramigerus (syn. Eragrostis australasica) at Mulga Downs Outcamp claypan (PSW040) is one of three known occurrences in the Pilbara bioregion. The record of Aponogeton queenslandicus from PSW036 (Munreemya Billabong) represents a new record for Western Australia with the closest populations occurring along the gulf coast of the Northern Territory and isolated records from south-east Queensland with its core distribution in wetlands along the coastal ranges of Queensland. Other vascular taxa are of taxonomic interest. Thyridea sp. northern saline floodplains (A. Markey & S. Dillon FM 10730) is a recently recognised putatively novel entity recorded from the margins of the Fortescue Marsh. The species flowers as the wetland dries following a submerged phase. An additional putatively novel taxon, Vallisneria sp. Weelarrana (M. N. Lyons & S. D. Lyons 3050) was collected opportunistically from Weelarrana Lake following a cyclonic rainfall event and is listed as a conservation priority species. Collections of Potamogeton × salicifolius (Potamogeton lucens × P. perfoliatus) from Gregory Gorge and Millstream represent the only occurrence outside Eurasia. With only one of the parent taxa present in Australia and neither in Western Australia the origin and alien status of these populations are unknown (Kaplan et al. 2019).

Within the Characeae several taxa collected during the survey are putatively new to science. Notably, Genus et sp. nov. (M. N. Lyons and D. A. Mickle 3080), recorded exclusively from Weelaranna Salt Lake (PSW043), has attributes significantly different from all previously described Characeae (Casanova 2013). This was confirmed by DNA analysis (K. Karol, pers. comm.). Formal description awaits the collection of additional material from this episodic wetland. Similarly, Chara sp. nov. (aff. globularis) (M. N. Lyons & D. A. Mickle 3218) and Nitella sp. nov. ‘verrucate’ (M. T. Casanova PBS7) are significantly different from other members of their respective genera.

Although all formal taxonomic descriptions have not been completed it also evident that the Pilbara includes a segregate charophyte flora. Collections from the current study have also provided material for the description of novel charophytes including Nitella mickleii currently endemic to the Pilbara (Casanova and Porter 2013; Casanova and Karol 2023a, 2023b). This highlights the value of systematic surveys in poorly sampled regions to make major contributions to biodiversity knowledge and provide valuable material for taxonomic studies, particularly for poorly collected groups, including the discovery of novel taxa. Notably only a single non-native aquatic plant (Ceratopteris thalictroides) was recorded from Pilbara wetlands adjacent to a major pastoral settlement. Elsewhere in north-west Australia, this taxon is considered as native (see Keighery 2013). The lack of weedy aquatics is unsurprising as many occurrences elsewhere in Australia are human-mediated, the product of accidental introductions from discarded ornamental material, an event that is unlikely in the sparsely populated Pilbara. However, the potential for the introduction of wetland associated (amphibious) weedy grasses and sedges remains real in the light of increasing movements of fodder (potentially contaminated) produced under irrigation (Sudmeyer et al. 2016; Galloway et al. 2022).

Comparable systematic surveys of wetland aquatic plants are limited in Australia, particularly at the regional scale. This is particularly true of arid zone wetlands. Earlier studies have included surveys of submerged macrophytes in salt lakes within the south-west of Western Australia, with Ruppia, Althenia and Lamprothamnium taxa systematically surveyed in relation to wetland salinity (Brock and Lane 1983). Vascular macrophytes were also included in an extensive wetland survey of the same region (Lyons et al. 2004). Wetland aquatic and amphibious plants were also included in the survey of the southern Carnarvon Basin of Western Australia, in a study that focused primarily on riparian vegetation (Gibson et al. 2000). In contrast to the Pilbara, the Carnarvon Basin is a relatively subdued landscape dominated by seasonal and ephemeral wetlands with few rocky uplands supporting permanent pools and springs, and with only six submerged aquatics recorded (Gibson et al. 2000), noting they did not record charophytes. In Australia, the most comparable wetland survey to the current study was undertaken in arid central Australia (c. southern half of the NT) in an area with a comparable diversity of wetland types to the Pilbara (Duguid et al. 2005).

Duguid et al. (2005) did not document the charophyte flora to species level in their study of 324 sites. They list 39 other taxa as being aquatic and semi-aquatic and provide details of other groups of taxa associated with wetlands. The classification of the aquatic/semi-aquatic status of taxa differed slightly between the studies. For example, we have included inundation tolerant shrubs and trees in the amphibious class, which does not directly equate to the semi-aquatic grouping of Duguid et al. (2005). In aligning our data with the scheme of Duguid et al. (2005) we recorded 38 aquatic and semi-aquatic taxa, suggesting the Pilbara is of comparable diversity to the flora of the southern Northern Territory. Notably the southern Northern Territory is significantly richer for Nymphaea (five taxa), a genus with tropical affinities.

Wetland type and associated hydrological regime were the primary drivers of compositional patterns of aquatic plant communities in the Pilbara. Permanent and seasonal sites (gorge pools and many spring feed river pools) showed the highest species richness, and such sites are likely to act as refugia as many occur as isolated pools along river channels during the dry season. Many river pools are likely to be groundwater dependent and maintain water during the dry season as isolated waterbodies along the length of major river channels. The importance of water permanence as refugia has been highlighted elsewhere in arid Australia (Brim Box et al. 2008). These sites may become increasingly important given predictions for significant temperature increases for the Pilbara region under climate change with rainfall likely to remain largely unchanged to 2090 (Sudmeyer 2016).

Claypans and other shallow ephemeral and intermittent wetlands were generally species poor and compositionally distinct from other Pilbara wetlands. At regional scales they are a compositionally heterogeneous group with occurrences concentrated on the western coastal plain and Fortescue valley. More detailed sampling within the upper Fortescue Valley revealed finer scale patterning in claypan composition with large interconnected systems capturing a greater diversity of plant and invertebrate communities (Pinder et al. 2017). Unique plant assemblages were also recorded from a cluster of claypans at the upper reaches of the Fortescue valley at Jigalong Creek flood plain and downstream of the Fortescue Marsh (Pinder et al. 2017). Except for the reservation of Fortescue Marsh itself, floodplain wetlands such as claypans are very poorly reserved across the Pilbara, with most reserves focussed on upland areas (Gibson et al. 2015). This and subsequent studies (Pinder et al. 2017) suggest broad compositional differences between claypans of the coastal plain, central Fortescue valley and eastern wetlands associated with the Jigalong Creek flood plain. This provides a broad framework to address reservation inadequacies for claypan wetlands across the region.

For all wetland types the compositional patterns in aquatic plants reported here are concordant with broad patterns in other aquatic biota sampled across the Pilbara by Lyons (2015) and Pinder et al. (2010). At broad scales this is unsurprising given the major drivers of community composition (water permanence and seasonality, substrate and wetland morphology) are common across groups. For aquatic plants floristic composition in part reflects the major functional plant types at an individual wetland which is driven by a similar suite of factors determining wetland type (Moor et al. 2017). Importantly, this concordance across groups provides a framework for conservation planning with synergies available to maximise the capture of wetland and river biodiversity across multiple biotic groups.

Mining and pastoral activities impact on wetland and river conservation values across the Pilbara, with direct impacts from alterations to hydrology associated with mine dewatering and its discharge and disturbance associated with the grazing of herbivores. These land uses are entrenched across the region and limit the capacity to establish new reserves managed primarily for conservation. An emerging threat to Pilbara rivers and springs is the introduction of redclaw crayfish, Cherax quadricarinatus (von Martens, 1868) (Pinder et al. 2019). A native of Queensland and the Northern Territory, it was first detected in Harding Dam, a drinking water reservoir 23 km south-east of Roebourne. Subsequently it has become widespread across the region. These populations are likely the result of illegal translocations to provide for recreational fishing. The introduction of other decapods has been shown to have significant impacts on macrophyte biomass with subsequent cascading effects on invertebrate communities (Harper et al. 2002; Lodge et al. 2005). This represents a major threat to the rich aquatic plant communities of Pilbara river pools.

Declaration of funding

The project as a component of the Pilbara Biological Survey was funded by the then Western Australian Department of Environment and Conservation, with contributions from the Western Australian Museum, the Commonwealth Government through its National Heritage Trust (NHT2), Straits Resources (Whim Creek Operation), and Rio Tinto Iron Ore (Dampier Salt Operation). In-kind support was provided by Rio Tinto Iron Ore, BHP Billiton Iron Ore, and Kitchener Mining’s Bamboo Creek operation.

Acknowledgements

Field work was assisted by Simon Lyons, Neil Gibson, Natalia Huang, and Judy Dunlop. Numerous pastoralists and Indigenous communities provided access to their leases and lands and assistance in locating and accessing sites. Terry MacFarlane and Greg Keighery provided much appreciated taxonomic assistance. Adrian Pinder provided valuable comments on earlier drafts of the manuscript.

References

AVH (2024) The Australasian virtual herbarium. Council of Heads of Australasian Herbaria. Available at https://avh.chah.org.au [accessed 5 February 2024]

Belbin L, Wallis E, Hobern D, Zerger A (2021) The atlas of living Australia: history, current state and future directions. Biodiversity Data Journal 9, e65023.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Brim Box JB, Duguid A, Read RE, Kimber RG, Knapton A, Davis J, Bowland AE (2008) Central Australian waterbodies: the importance of permanence in a desert landscape. Journal of Arid Environments 72(8), 1395-1413.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Brock MA, Lane JAK (1983) The aquatic macrophyte flora of saline wetlands in Western Australia in relation to salinity and permanence. Hydrobiologia 105, 63-76.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Buxton RT, Bennett JR, Reid AJ, Shulman C, Cooke SJ, Francis CM, Nyboer EA, Pritchard G, Binley AD, Avery-Gomm S, Ban NC, Beazley KF, Bennett E, Blight LK, Bortolotti LE, Camfield AF, Gadallah F, Jacob AL, Naujokaitis-Lewis I, Raudsepp-Hearne C, Roche DG, Soulard F, Stralberg D, Sadler KD, Solarik KA, Ziter CD, Brandt J, McKindsey CW, Greenwood DA, Boxall PC, Ngolah CF, Chan KMA, Lapen D, Poser S, Girard J, DiBacco C, Hayne S, Orihel D, Lewis D, Littlechild D, Marshall SJ, McDermott L, Whitlow R, Browne D, Sunday J, Smith PA (2021) Key information needs to move from knowledge to action for biodiversity conservation in Canada. Biological Conservation 256, 108983.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Casanova MT (2005) An overview of Chara L. in Australia (Characeae, Charophyta). Australian Systematic Botany 18(1), 25-39.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Casanova MT (2009) An overview of Nitella (Characeae, Charophyceae) in Australia. Australian Systematic Botany 22, 193-218.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Casanova MT (2013) Lamprothamnium in Australia (Characeae, Charophyceae). Australian Systematic Botany 26(4), 268-290.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Casanova MT (2015) Historical water-plant occurrence and environmental change in two contrasting catchments. Marine and Freshwater Research 67(2), 210-223.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Casanova MT, Karol KG (2023a) Charophytes of Australia’s Northern Territory – I. Tribe Chareae. Australian Systematic Botany 36(1), 38-79.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Casanova MT, Karol KG (2023b) Charophytes of Australia’s Northern Territory – II. Tribe Nitelleae. Australian Systematic Botany 36(4), 322-353.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Casanova MT, Porter JL (2013) Two new species of Nitella (Characeae, Charophyceae) from arid-zone claypan wetlands in Australia. Muelleria: An Australian Journal of Botany 31, 53-59.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Clarke KR, Somerfield PJ, Chapman MG (2006) On resemblance measures for ecological studies, including taxonomic dissimilarities and a zero-adjusted Bray–Curtis coefficient for denuded assemblages. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 330(1), 55-80.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Costelloe JF, Powling J, Reid JRW, Shiel RJ, Hudson P (2005) Algal diversity and assemblages in arid zone rivers of the Lake Eyre Basin, Australia. River Research and Applicactions 21(2–3), 337-349.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Davidson NC, Finlayson CM (2018) Extent, regional distribution and changes in area of different classes of wetland. Marine and Freshwater Research 69(10), 1525-1533.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Dudgeon D, Arthington AH, Gessner MO, Kawabata Z-I, Knowler DJ, Lévêque C, Naiman RJ, Prieur-Richard A-H, Soto D, Stiassny MLJ, Sullivan CA (2006) Freshwater biodiversity: importance, threats, status and conservation challenges. Biological Reviews 81(2), 163-182.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Duguid A, Barnetson J, Clifford B, Pavey C, Albrecht D, Risler J, McNellie M (2005) Wetlands in the Arid Northern Territory, vol 1, a report to the Australian government department of the environment and heritage on the inventory and significance of wetlands in the Arid NT. Northern Territory Government Department of Natural Resources, Environment and the Arts, Alice Springs.

Eckersley J, O’Donnell AJ, Pettit NE, Grierson PF (2024) Developing plant functional groups to identify changes in functional composition and diversity in a dryland river experiencing artificially sustained flows. Science of The Total Environment 934, 173198.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Fensham RJ, Fairfax RJ, Sharpe PR (2004) Spring wetlands in seasonally arid Queensland: floristics, environmental relations, classification and conservation values. Australian Journal of Botany 52(5), 583-595.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Gibson N, Keighery GJ, Lyons MN (2000) The flora and vegetation of the seasonal and perennial wetlands of the southern Carnarvon Basin, Western Australia. Records of the Western Australian Museum, Supplement 60, 175-199.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Gibson LA, Williams KJ, Pinder AM, Harwood TD, McKenzie NL, Ferrier S, Lyons MN, Burbidge AH, Manion G (2015) Compositional patterns in terrestrial fauna and wetland flora and fauna across the Pilbara biogeographic region of Western Australia and the representativeness of its conservation reserve system. Records of the Western Australian Museum, Supplement 78, 515-545.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Harper DM, Smart AC, Coley S, Schmitz S, De Beauregard A-CG, North R, Adams C, Obade P, Kamau M (2002) Distribution and abundance of the Louisiana red swamp crayfish Procambarus clarkii Girard at Lake Naivasha, Kenya between 1987 and 1999. Hydrobiologia 488, 143-151.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hoffmann S (2022) Challenges and opportunities of area-based conservation in reaching biodiversity and sustainability goals. Biodiversity and Conservation 31, 325-352.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hunter JT, Lechner AM (2018) A multiscale, hierarchical, ecoregional and floristic classification of arid and semi-arid ephemeral wetlands in New South Wales, Australia. Marine and Freshwater Research 69(3), 418-431.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Jenkins KM, Boulton AJ, Ryder DS (2005) A common parched future? Research and management of Australian Arid-zone Floodplain Wetlands. Hydrobiologia 552, 57-73.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Kaplan Z, Fehrer J, Jobson RW (2019) Discovery of the Northern Hemisphere hybrid Potamogeton ×salicifolius in the Pilbara region of Western Australia. Telopea 22, 141-151.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Keighery G (2013) Weedy native plants in Western Australia: an annotated checklist. Conservation Science Western Australia 8(3), 259-275.

| Google Scholar |

Khelifa R, Mahdjoub H, Samways MJ (2022) Combined climatic and anthropogenic stress threaten resilience of important wetland sites in an arid region. Science of The Total Environment 806, 150806.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Kingsford RT, Roshier DA, Porter JL (2010) Australian waterbirds – time and space travellers in dynamic desert landscapes. Marine and Freshwater Research 61(8), 875-884.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Lodge DM, Rosenthal SK, Mavuti KM, Muohi W, Ochieng P, Stevens SS, Mungai BN, Mkoji GM (2005) Louisiana crayfish (Procambarus clarkii) (Crustacea: Cambaridae) in Kenyan ponds: non-target effects of a potential biological control agent for schistosomiasis. African Journal of Aquatic Science 30(2), 119-124.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Lyons MN (2015) The riparian flora and plant communities of the Pilbara region of Western Australia. Records of the Western Australian Museum, Supplement 78, 485–513. 10.18195/issn.0313-122x.78(2).2015.485-513

Lyons MN, Gibson N, Keighery GJ, Lyons SD (2004) Wetland flora and vegetation of the Western Australian wheatbelt. Records of the Western Australian Museum, Supplement 67, 39-89.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Margules CR, Pressey RL, Williams PH (2002) Representing biodiversity: data and procedures for identifying priority areas for conservation. Journal of Biosciences 27, 309-326.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

McKenzie NL, van Leeuwen S, Pinder AM (2009) Introduction to the Pilbara Biodiversity Survey, 2002–2007. Records of the Western Australian Museum, Supplement 78, 3-89.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Moor H, Rydin H, Hylander K, Nilsson MB, Lindborg R, Norberg J (2017) Towards a trait-based ecology of wetland vegetation. Journal of Ecology 105(6), 1623-1635.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Parra G, Guerrero F, Armengol J, Brendonck L, Brucet S, Finlayson CM, Gomes-Barbosa L, Grillas P, Jeppesen E, Ortega F, Vega R, Zohary T (2021) The future of temporary wetlands in drylands under global change. Inland Waters 11(4), 445-456.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Pinder AM, Halse SA, Shiel RJ, McRae JM (2010) An arid zone awash with diversity: patterns in the distribution of aquatic invertebrates in the Pilbara region of Western Australia. Records of the Western Australian Museum, Supplement 78, 205-246.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Pinder A, Lyons M, Collins M, Lewis L, Quinlan K, Shiel R, Coppen R, Thompson F (2017) Wetland biodiversity patterning along the middle to upper fortescue valley (Pilbara: Western Australia) to inform conservation planning. Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions, Kensington Western Australia.

Pinder A, Harman A, Bird C, Quinlan K, Angel F, Cowan M, Lewis L, Thillainath E (2019) Spread of the non-native redclaw crayfish Cherax quadricarinatus (von Martens, 1868) into natural waters of the Pilbara region of Western Australia, with observations on potential adverse ecological effects. BioInvasions Records 8(4), 882-897.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Reichman O, Jones MB, Schildhauer MP (2011) Challenges and opportunities of open data in ecology. Science 331(6018), 703-705.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Reid MA, Thoms MC, Chilcott S, Fitzsimmons K (2017) Sedimentation in dryland river waterholes: a threat to aquatic refugia? Marine and Freshwater Research 68(4), 668-685.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Roshier DA, Rumbachs RM (2004) Broad-scale mapping of temporary wetlands in arid Australia. Journal of Arid Environments 56(2), 249-263.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Rossini RA, Fensham RJ, Stewart-Koster B, Gotch T, Kennard MJ (2018) Biogeographical patterns of endemic diversity and its conservation in Australia’s artesian desert springs. Diversity and Distributions 24(9), 1199-1216.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Scholes RJ (2020) The future of semi-arid regions: a weak fabric unravels. Climate 8(3), 43.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

The Global Biodiversity Information Facility (2024) What is GBIF? Available at https://www.gbif.org/what-is-gbif

Timms BV (2022) Aquatic invertebrate community structure and phenology of the intermittent treed swamps of the semi-arid Paroo Lowlands in Australia. Wetlands Ecology and Management 30, 771-784.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Triest L (1988) A revision of the genus Najas L (Najadaceae) in the old world. Mémoires de la Classe des Sciences naturelles et médicales, (N.S.) ARSOM 22, 1-172.

| Google Scholar |

Western Australian Herbarium (2024) Florabase. Available at https://florabase.dbca.wa.gov.au [accessed 5 February 2024]