A new vegetation classification for Western Australia’s Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve and its significance for fire management

A. J. M. Hopkins A , A. A. E. Williams B , J. M. Harvey C and Stephen D. Hopper D *

D *

A

B

C

D

Abstract

Vegetation mapping is subject to a diversity of approaches and lack of coordination, leading to low repeatability and predictive power in the species-rich flora of the Southwest Australian Floristic Region. Yet it has potential as a tool of use in fire management.

This project, extending over five decades, aimed to develop an authoritative vegetation classification and map plant fire responses at Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve.

Using Muir’s classification approach, field surveys were conducted with aerial photography in hand. Thirty-three vegetation units were identified, described, mapped, and photographed. Defining attributes and taxa were identified for each unit.

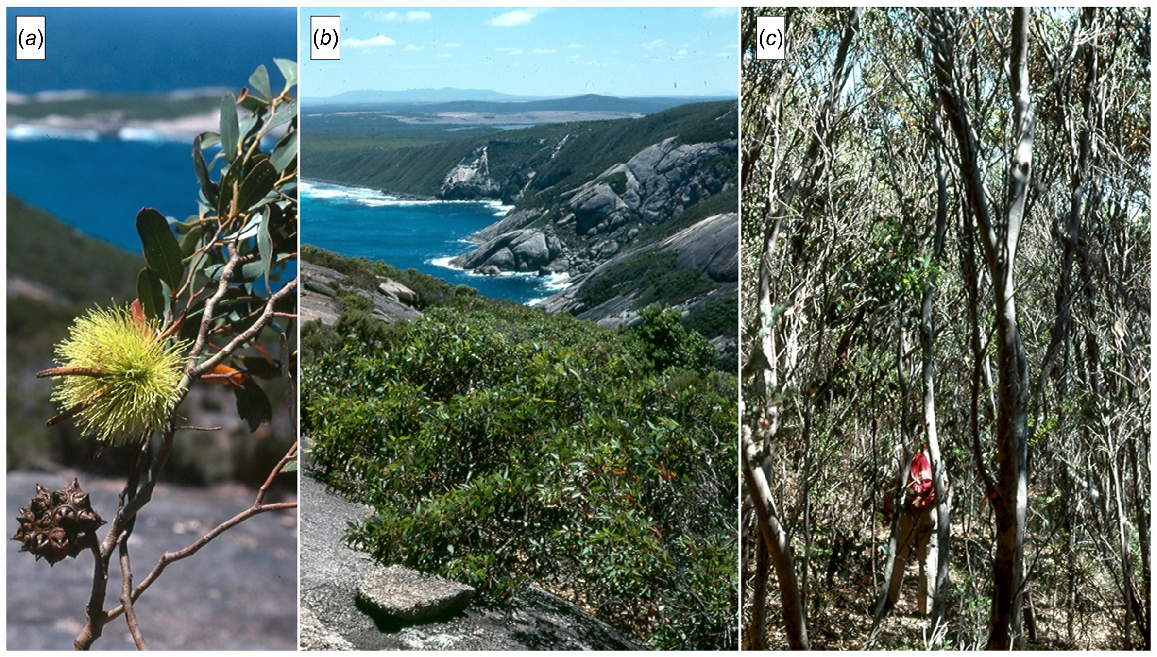

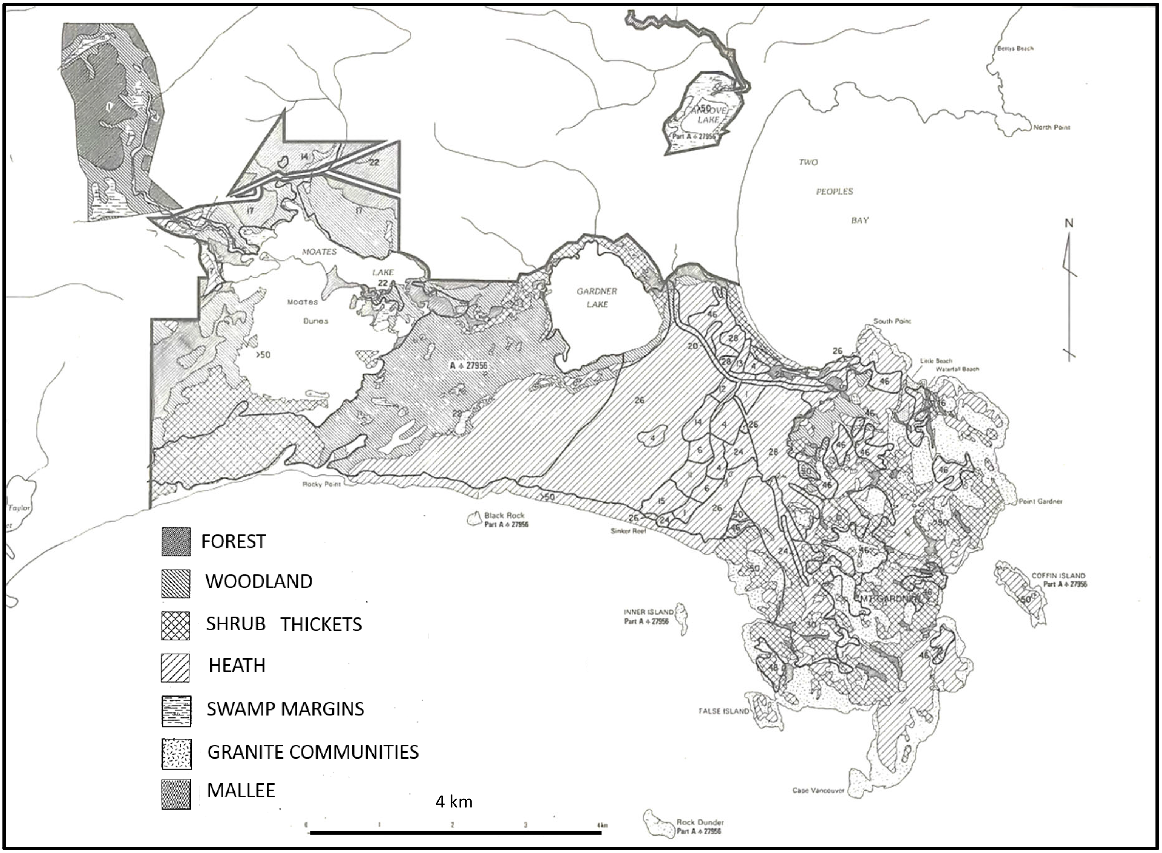

Map, descriptions, and photographs detail forest, woodlands, mallee, scrub thickets, heath, wetlands, and granite communities on the Reserve. The forest, woodland, and shrublands were adequately classified and mapped. However, granite complex and mallee were least satisfactory, oversimplifying a rich diversity of vegetation types and habitats.

The Reserve may be divided for management into the central third of heath, shrublands, and low woodlands largely across the isthmus, the dunes and wetlands of the west with a greater diversity of vegetation types, and the eastern granite inselberg attaining 408 m with the most diverse vegetation types. The latter inselberg needs continued protection from fire and other disturbances. Greatest change in vegetation is seen in lowland landscapes where fire activity has also been pronounced.

Vegetation mapping has been a valuable aid for managers and fire planning, and for active comanagement with appropriate Aboriginal families.

Keywords: fire management, granite outcrop flora, inselberg, Noongar, OCBIL, vegetation mapping, wetlands, YODFEL.

Introduction

This paper is part of a series focused on Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve on Western Australia’s south coast (Chatfield and Saunders 2024; Hopkins et al. 2024; Hopper et al. 2024; Knapp et al. 2024; Wyatt et al. 2024; R. Hart, G. Freebury, S. Barrett, unpubl. data). The biodiversity of the Reserve is significant, being located close to King George Sound, the State’s earliest settlement, between the high rainfall southern forests and semiarid mallee and kwongkan (for this spelling see Hopper 2014) floras. An unusually long history of botanical documentation (Hopper et al. 2024) has facilitated the Reserve’s value for investigation of different vegetation mapping procedures.

Although having a history dating back more than a century, vegetation mapping remains a challenging scientific discipline (Keith 2017; Luxton et al. 2021a). It has moved from intuitive descriptive accounts based on structure (trees, shrubs, herbs, etc.) and canopy cover, to floristic plot-based multivariate analyses and remote sensing applications (Schut et al. 2010; Luxton et al. 2021b). Irrespective of the scale attempted, from global to microcommunities on rock outcrops, vegetation mapping has been subject to a diversity of approaches and a lack of coordination, leading to low repeatability and predictive power. This situation makes the search for correlations and causation difficult (Keith and Tozer 2017), and the problem is acute in Global Biodiversity Hotspots such as the Southwest Australian Floristic Region (Hopper and Gioia 2004; Gioia and Hopper 2017). Vegetation mapping has uses in conservation, environmental impact assessment, potential land use planning, sustainable agricultural development, and revegetation/restoration of cleared lands (Beard et al. 2013). Despite these challenges, the utility of vegetation maps as summaries of biodiversity pattern is evident in the continuing pursuit of better methods (Luxton et al. 2021a) and in the use of schemes such as the Interim Biodiversity Regionalisation for Australia (IBRA7 2024).

Here, we present an association-level vegetation map of a sizeable nature reserve on the south coast of Western Australia. Granite outcrop vegetation is exceptional in its fine scale divergence associated with microtopography, soil depth, and aspects such as shading. For example, over distances of just a few metres, one can move from bare rock with cryptogamic crusts and rock pools (gnamma), onto moss fields, herbfields, dwarf shrublands to shrublands, woodlands and forests (Nikulinsky and Hopper 1999; Porembski and Bathlott 2000). Such fine scale patterns cannot be presented at the usual scale of vegetation maps, so authors often revert to obscurely defined concepts such as ‘granite complex’ (Diels 1906; Beard et al. 2013). Our general vegetation map adopts this approach. Moreover, such a vegetation map has the potential to materially benefit management of fire and the conservation of significant threatened species of animals and plants, except for those communities found on granite complexes.

History of vegetation mapping in the Southwest Australian Floristic Region

Vegetation mapping has been undertaken in Western Australia since the pioneering work of Ludwig Diels (1906). The research of Diels was thorough and perceptive, based on extensive collections, photographs, and field notes. For his Southwest Botanical Province, an elegant summary of recognised vegetation types was given (Table 1).

| 1. Littoral formations | |

| a. Mangrove | |

| b. Mudflat formation | |

| c. Open formation of sandy beaches | |

| d. Littoral wood formations | |

| (i) Northern zone | |

| (ii) Tuart zone | |

| (iii) Southern zone | |

| 2. Woodland formations | |

| a. Eucalyptus forests | |

| (i) Jarrah forest | |

| (ii) Karri forest | |

| (iii) Wandoo forest | |

| (iv) Transitions to the woodlands of the Eremaea | |

| b. Mixed woodlands of the coastal plain | |

| 3. Shrubland formations | |

| a. Sclerophyll scrub | |

| b. Sand heaths | |

| 4. Swamp formations | |

| a. Alluvial formation | |

| b. Formation of granite rocks |

Diels classified vegetation by first separating coastal from inland formations, and then subdividing inland formations into those dominated by trees, shrubs, or swampy vegetation. Further subdivision was made in the case of woodland formations into those dominated by eucalypts or other genera, and for shrublands, those forming scrubs versus sand heaths. Swamps were divided between alluvial formations versus those found on granite outcrops. Diels also recognised that one could not escape transitional situations, especially that between the south-west woodland communities and those of the drier inland Eremaean region.

This relatively simple scheme enabled Diels to subdivide the Southwest Botanical Province into several Districts with characteristic flora (endemics, etc.). In many ways, subsequent workers merely elaborated on Diels’ scheme, albeit monumentally by Beard who succeeded single-handedly in mapping the vegetation of all of Western Australia often down to the scale of 1:250,000 and at a level below the lowest used by Diels (Gardner 1942; Beard et al. 2013). Beard’s work was taken up as part of the national IBRA7 scheme (Interim Biogeographic Regionalisation of Australia), and is now entrenched in government databases such as the Western Australian Herbarium’s (1998–2024) Florabase, despite being half a century old in design and older in concept.

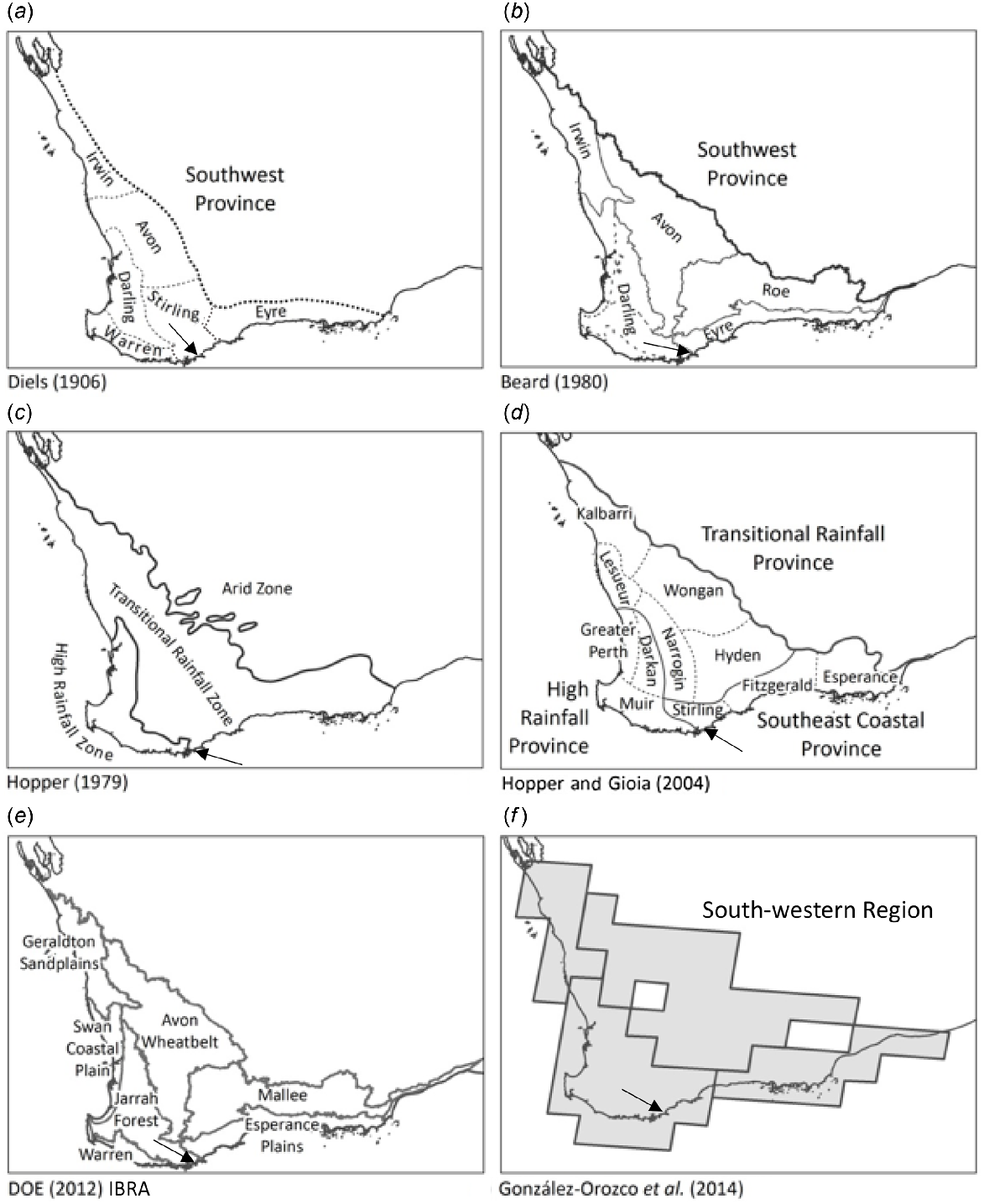

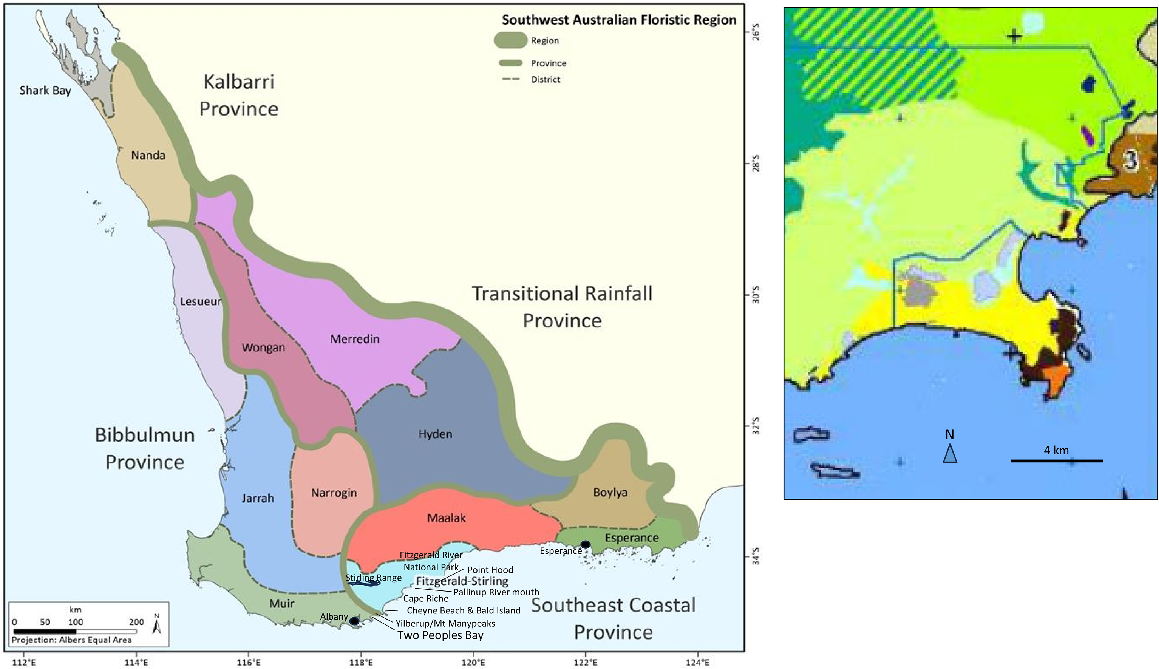

Quantitative floristic mapping using grids of latitude and longitude began in the 1950s with work on the Proteaceae by Speck (1958). What was then known about this approach subsequently was summarised by Hopper (1979) and Lamont et al. (1984). Computer analyses of floristic data led to the formulation of a new hierarchy of Floristic Districts, Provinces, and Regions (Hopper and Gioia 2004; Gioia and Hopper 2017; Figs 1, 2). Significant differences were found between the floristic phytogeography generated and Beard’s (1979, 1981; Beard et al. 2013) vegetation maps. Moreover, quantitative plot-based floristic studies analysed with multivariate statistics have become routine among vegetation mappers (e.g. Sandiford and Barrett 2010). The challenge, as always, has been reaching agreement on the scale at which studies are undertaken, and on the definitions and data used to derive vegetation maps.

Historical bioregionalisations of the Southwest Australian Floristic Region excluding Gioia and Hopper’s (2017). Two Peoples Bay (arrows) is near the border separating south coast subdivisions in all but (a) and (f). The bioregionalisation schemes are: (a) Diels’ Southwest Botanical Province and Districts (Diels 1906); (b) biogeographic regions within Southwest Botanical Province, from Beard (1980); (c) Hopper’s (1979) rainfall zones; (d) Provinces and districts from Hopper and Gioia’s (2004) Southwest Australian Floristic Region; (e) south-west bioregions from Interim Biogeographic Regionalisation of Australia (Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water 2012; IBRA does not implement a hierarchical aggregation – displayed bioregions approximate Beard’s concept of the Southwest Botanical Province); (f) phytogeographical regions based on 6043 species of Australian hornworts, liverworts, mosses, ferns, orchids, Acacia, eucalypts, Melaleuca and Asteraceae (González-Orozco et al. 2014). Modified from Gioia and Hopper (2017).

Left map: Gioia and Hopper’s (2017) floristic provinces and districts within the Southwest Australian Floristic Region, with some place names mentioned in the text. Right: Beard’s (1979) first vegetation map of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve and surrounds: yellow – shrublands (Acacia scrub heath); dark grey – sand dunes; black – low forest (Melaleuca); orange – shrublands (mixed heath); pale green – low forest (jarrah, Allocasuarina fraseriana); pale blue – sedgeland (reed swamps); dark brown – tallerack mallee heath; blue lines – IBRA boundaries (note that Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve is excluded from the high rainfall Warren IBRA Region to the west); modified from Sandiford and Barrett (2010).

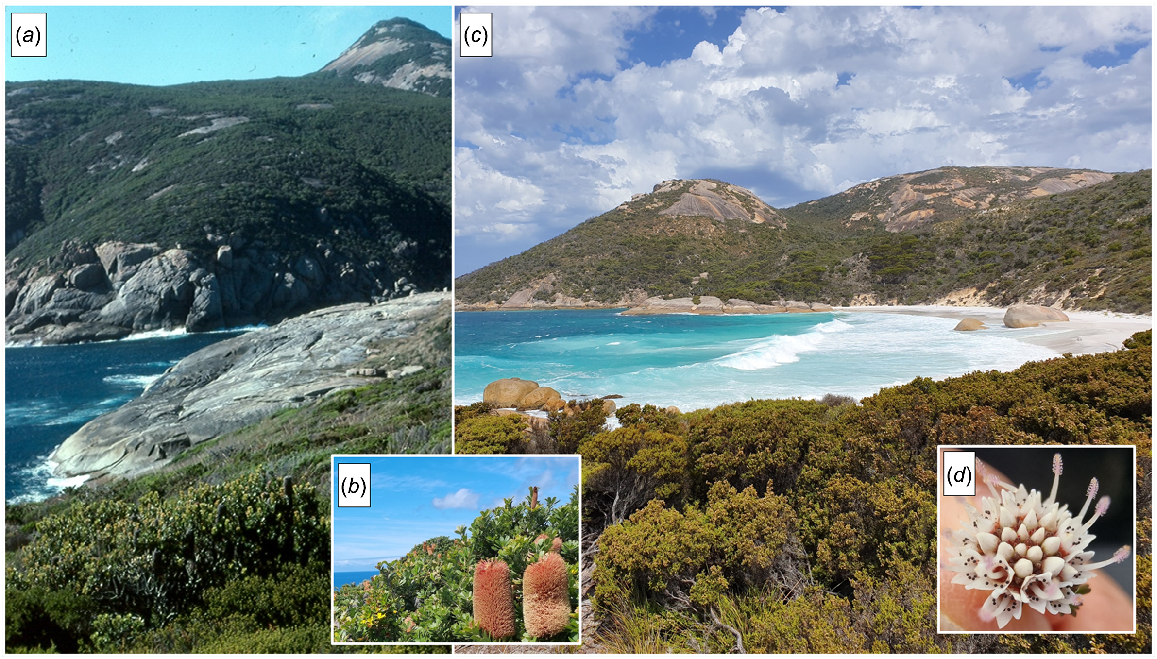

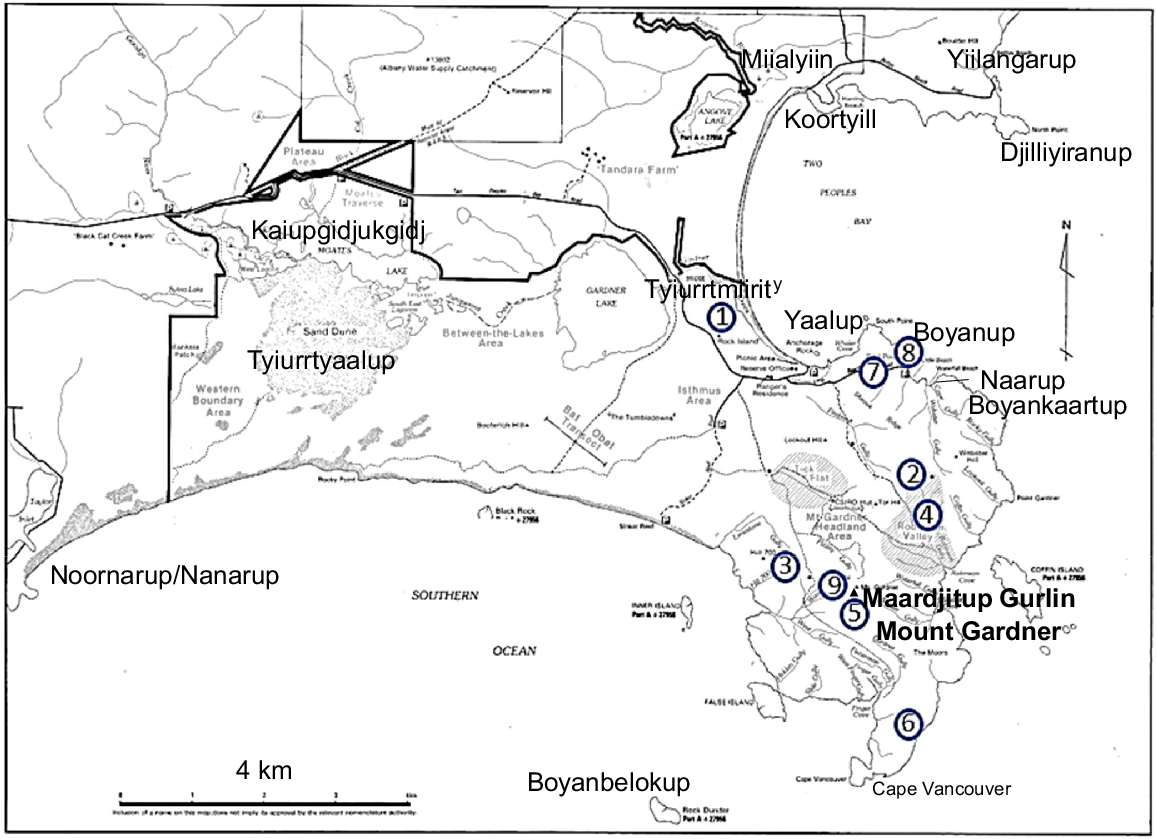

In Western Australia, Muir (1977) developed a classification of vegetation based on life form and percentage canopy cover that has stood the test of time over its predecessors such as that of Diels (1906) in Table 1. In particular, it recognises mallee vegetation (Yates et al. 2017) as distinct from trees or single-stemmed woody shrubs (Table 2). It also distinguishes herbaceous species from recognisable life forms such as mat plants (e.g. Borya on granite outcrops), hummock grasses, bunch grasses, and sedges, and recognises ferns and liverworts/mosses as forming distinguishable communities (often on granite outcrops). This paper applies this system to the vegetation in Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve on the south coast near Albany (Fig. 3). Created in 1967 primarily to conserve the then recently rediscovered Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird (Atrichornis clamosus) (Danks 1997), Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve occupies 4774.7 ha, and is dominated by the granite inselberg Maardjitup Gurlin (Merningar Noongar name of Mt Gardner), attaining 408 m at the end of the eastern peninsula (Fig. 3). An isthmus to the west gives way to lowlands of dunes and wetlands, with a low lateritic plateau in the north west (Smith 1987). The Reserve receives approximately 800 mm of rainfall each year.

| Life form/height class | Canopy cover | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dense d | Mid-dense c | Sparse i | Very sparse r | |||

| 70–100% | 30–70% | 10–30% | 2–10% | |||

| T | Trees >30 m | Dense Tall Forest | Tall Forest | Tall Woodland | Open Tall Woodland | |

| M | Trees 15–30 m | Dense Forest | Forest | Woodland | Open Woodland | |

| LA | Trees 5–15 m | Dense Low Forest A | Low Forest A | Low Woodland A | Open Low Woodland A | |

| LB | Trees <5 m | Dense Low Forest B | Low Forest B | Low Woodland B | Open Low Woodland B | |

| KT | Mallee tree form | Dense Tree Mallee | Tree Mallee | Open Tree Mallee | Very Open Tree Mallee | |

| KS | Mallee shrub form | Dense Shrub Mallee | Shrub Mallee | Open Shrub Mallee | Very Open Shrub Mallee | |

| S | Shrubs >2 m | Dense Thicket | Thicket | Scrub | Open Scrub | |

| SA | Shrubs 1.5–2.0 m | Dense Heath A | Heath A | Low Scrub A | Open Low Scrub A | |

| SB | Shrubs 1.0-1.5 m | Dense Heath B | Heath B | Low Scrub B | Open Low Scrub B | |

| SC | Shrubs 0.5–1.0 m | Dense Low Heath C | Low Heath C | Dwarf Scrub C | Open Dwarf Scrub C | |

| SD | Shrubs 0.0–0.5 m | Dense Low Heath D | Low Heath D | Dwarf Scrub D | Open Dwarf Scrub D | |

| P | Mat plants | Dense Mat Plants | Mat Plants | Open Mat Plants | Very Open Mat Plants | |

| H | Hummock grass | Dense Hummock Grass | Mid-Dense Hummock Grass | Hummock Grass | Open Hummock Grass | |

| GT | Bunch grass >0.5 m | Dense Tall Grass | Tall Grass | Open Tall Grass | Very Open Tall Grass | |

| GL | Bunch grass <0.5 m | Dense Low Grass | Low Grass | Open Low Grass | Very Open Low Grass | |

| J | Herbaceous spp. | Dense Herbs | Herbs | Open Herbs | Very Open Herbs | |

| VT | Sedges >0.5 m | Dense Tall Sedges | Tall Sedges | Open Tall Sedges | Very Open Tall Sedges | |

| VL | Sedges <0.5 m | Dense Low Sedges | Low Sedges | Open Low Sedges | Very Open Low Sedges | |

| X | Ferns | Dense Fems | Fems | Open Ferns | Very Open Ferns | |

| X | Mosses, liverwort | Dense Mosses | Mosses | Open Mosses | Very Open Mosses | |

Map of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve showing place names. Larger names are from the Merningar Noongar Knapp family (Knapp et al. 2024). Blue encircled numbers are granite outcrops surveyed by Hopper et al. (2024). Base map provided by CSIRO.

Two Peoples Bay was first named by Merningar Bardok Noongar people, alluding to people descended from those who held stingray wiernyert/Dreaming based at Yilberup/Mt Manypeaks, and their adjacent south-western neighbours who hold shark wiernyert/Dreaming focused on Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner, the centre-point of today’s Reserve (Knapp et al. 2024). The French/English name Baie des Deux-Nations/Two Peoples Bay was proposed by the French sailor Jacques Ransonnet who in February 1803 was dispatched by Midshipman Charles Baudin to survey the three bays of King George Sound, as well as the coast as far east as Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner. Noticing a building when anchored near the opening of the bay, Ransonnet met Captain Isaac Pendleton, commander of the sealing brig Union out of New York, who cordially greeted the French sailors. To commemorate the subsequent friendly meeting of Pendleton with Baudin in King George Sound, Ransonnet proposed the name Baie des Deux-Nations for Two Peoples Bay (Chatfield and Saunders 2024), having no idea that the Noongars had long before settled on a similar interpretation and name.

The Reserve straddles the transition from high rainfall southern forest to semiarid mallee and kwongkan floras (Pate and Beard 1984; Christensen 1992; Lambers 2014; Yates et al. 2017). The Reserve is floristically rich, with 853 taxa now recorded (Hopper et al. 2024). Moreover, the majority of these species are at the easterly end of their geographic range, suggesting that the Reserve is best placed on the eastern border of the high rainfall forest vegetation rather than in the adjacent semiarid districts or provinces.

Vegetation studies of the Albany region

With respect to the Albany region, Diels (1906) drew a line placing the Torndirrup Peninsula in the Warren Botanical District (approximately the Muir District in Fig. 2), and the town of Albany eastwards to the lower Pallinup River in the Stirling Botanical District (very approximately the Fitzgerald–Stirling District in Fig. 2). Thus, the vegetation of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve was aligned by Beard (1979) with the semiarid kwongkan shrublands, mallee and low forest, and woodlands of the Stirling Range and environs rather than with the taller southern forests of higher rainfall country to the west (Fig. 2).

Diels’ work was followed up by Gardner and Bennetts (1956) who moved the intersection with the south coast of the Warren/Stirling Districts eastwards to Cheyne Beach. Thereafter Beard (1979, 1981) drew up a comprehensive series of vegetation maps for the whole of Western Australia (Beard et al. 2013) mapping vegetation associations, a level below that presented by Diels (Table 1). Beard’s maps shifted the boundary between southern forests and semiarid country to Yiilangarup/Betties Beach compared with Diels’ concept. Beard (1979) distinguished the low forest of jarrah (Eucalyptus marginata)/marri (Corymbia calophylla) on the north-west plateau of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve from dwarf forms of low woodland adjacent on the Reserve and also found on Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner.

The question of the appropriate vegetation descriptors for Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve was not addressed in the Albany Regional Vegetation Survey (Sandiford and Barrett 2010), due to perceived inaccuracies of the available maps and insufficient time to correct them (S. Barrett, pers. comm.). However, lands on three sides of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve were included. This year-long survey by two botanists was based on 785 floristic relevés (not quadrats) across 124,415 ha of vegetated land outside national parks and nature reserves in an area 30 km east and west of Albany and 20 km north. Sandiford and Barrett (2010) recognised 67 native vegetation units through multivariate statistical analysis. Roughly equivalent to the current flora list of 853 taxa for Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve (Hopper et al. 2024), ‘over 800’ species were also recorded (Sandiford and Barrett 2010), but notably annuals and geophytes such as orchids were excluded from the final analyses of vegetation units. Orchids constitute the largest family on Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve, with 101 taxa so far recorded (Hopper et al. 2024).

A surprising result emerged from a comparison with Beard’s (1979) earlier vegetation map covering the same region covered by the Albany Regional Vegetation Survey. It was found that only one of Beard’s vegetation associations (Karri Forest) equated directly with an Albany Regional Vegetation Survey unit. The rest of the mapping had no equivalents. For example, Beard (1979) mapped major drainage lines and swamp areas as either Reed Swamps or Paperbark Forest. Sandiford and Barrett (2010) divided the same landforms and vegetation communities into Callistachys spp. Thicket, Pericalymma spongiocaule Low Heath, Evandra aristata sedgeland, Homalospermum firmum/Callistemon glaucus Peat Thicket, Melaleuca preissiana/Melaleuca cuticularis Open Woodland, and Taxandria juniperina Closed Forest. Such discordance makes it difficult to compare and contrast the results of the two studies. Clearly, scale and detail generated through sampling are key issues underpinning this discordance.

Apart from noting that their study area embraced the intersection of ‘three IBRA biogeographic regions – the Warren, Jarrah Forest and Esperance Plains Regions’ Sandiford and Barrett (2010) did not address precisely where the boundaries should lie. This is more than a purely academic question, as different management regimes are applied by many landowners depending upon how they perceive the vegetation under their control. Hence one objective of our study was to ascertain whether a finer scale classification of the vegetation of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve might further clarify best phytogeographical placement of the Reserve.

Consequently, this paper provides a detailed description, illustrations, and a detailed map of vegetation of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve. The level of detail in the present work reflects two general features of vegetation mapping:

that vegetation mapping is an iterative process. This map is more detailed than any previous map, but as knowledge increases then further improvements and refinements can be expected; and,

that the scale and level of detail selected is appropriate to the purpose for which this map is to be used. This paper is oriented towards management, particularly in relation to fire. Thus, an attempt has been made to determine vegetation boundaries of relevance to fire behaviour as well as of ecological significance. It is important to know, for example, whether a fire is approaching low forest, heathland, or swamp vegetation. Each situation would require a different management solution to maintain control and minimise damage to threatened assets.

Previous work

The vegetation and flora of the Albany – Stirling Range – Cape Riche triangle have received considerable attention since about 1800. The many collectors and naturalists invariably provided some description of the landforms and vegetation types they observed on their travels, but it was not until Diels (1906) that the vegetation was formally classified. In particular, Diels described a number of shrub formations of which Sklerophyll Gebüsche (sclerophyllous bush) was the one he considered to make the greatest contribution to the floristic richness of south-western Australia (Diels 1906). Diels specifically described the sclerophyllous bush vegetation around King George Sound (Albany) and on the Stirling Range and suggested that it would continue eastwards along the coast as far as Esperance.

The extent and importance of shrublands in the Albany area and variety of other vegetation types there was confirmed in 1979 when J. S. Beard published his 1:250,000 vegetation map (Albany–Mt Barker sheet) (Beard 1979). He showed four principal vegetation types on Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve:

Heath of mixed composition at the end of the peninsula between Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner and Cape Vancouver (Fig. 3);

Agonis flexuosa scrub heath over the areas west of the granitic outcrops and south of Kaiupgidjukgidj/Moates Lake and Tyiurrtmiirity/Gardner Lake;

Eucalyptus marginata (jarrah), E. staeri, Allocasuarina fraseriana low forest to the north of Kaiupgidjukgidj/Moates Lake; and

Reeds (sedges, Restionaceae, and heath shrubs) north of Tyiurrtmiirity/Gardner Lake and around Miialyiin/Angove Lake.

Beard used the eastern limit of the tree form of jarrah to define the boundary between the Darling Botanical District and the Eyre Botanical District (Fig. 1b). He thus included the forested area north of Kaiupgidjukgidj/Moates Lake in the East Kalgan Vegetation System, a part of the first of these two phytogeographic districts. The remainder of the Reserve was described as part of the Bremer Vegetation System of the Eyre Botanical District, a system that includes the granitic uplands and coastal dune complexes to the east as far as Point Hood.

Some of Beard’s maps show a Manypeaks Vegetation System, but this was incorporated into the Bremer System at a late stage of drafting (J. S. Beard, pers. comm.). He commented (Beard 1981, p. 192) that gradual transitions from woodland to open sandplain were usual, ‘and the mapped boundary is therefore an arbitrary line’. This was evident when he advocated placing in the Bremer System of the Eyre District ‘granite bosses and sandhills stretching from Nanarup (Fig. 3) eastwards to Point Hood. The granite masses of Mt Gardner, Mt Manypeaks and Bald Island are included, together with others further east, and the dune complexes between them’ (Beard 1981; p. 214). Hence an ‘arbitrary’ boundary of considerable significance divided Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve in two where the jarrah low forest on massive laterite in the north-west of the reserve gave way to open woodlands, heath, and swamp forests of the isthmus and beyond up onto the Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner granite inselberg.

A more detailed description of the vegetation of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve was first provided by Hopper (1981), who recognised eight generalised physiographic units and described the vegetation associated with them:

The granitic headland (Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner) with areas of overlying sand limestone supporting dense low heaths, dense thickets, and with eucalypt and Melaleuca dense low forests in gullies and on the margins of the granite;

The dunes, limestone cliffs, and ridges of the isthmus with dense low heath with scattered emergents of Agonis flexuosa, Banksia attenuata, B. littoralis;

thickets of B. sessilis and scattered mallees with Adenanthos sericeus thickets on coastal dunes;

The wetlands fringed by sedgelands with a backing of low woodland and forests of Taxandria juniperina, Banksia littoralis, Melaleuca croxfordiae, M. cuticularis, M. preissiana, and M. raphiophylla;

The area between Kaiupgidjukgidj/Moates and Tyiurrtmiirity/Gardner Lakes, and southwards to the coast, is a complex of dunes and swales. The dunes are well-vegetated with Agonis flexuosa, Adenanthos sericeus thickets and the swales are composed of swamp, sedgelands, and low forests and low woodlands of Banksia littoralis;

The coastal dunes and swales in the south-western corner of the Reserve with a gradation of vegetation from heaths and thickets near the coast to Agonis flexuosa, Banksia praemorsa woodlands further inland (including a small Banksia-rich sandpatch);

The lateritic and sandy-lateritic hills in the north and north-west supporting low forests and open woodlands of Eucalyptus marginata, E. staeri, Corymbia calophylla, and Allocasuarina fraseriana; and

The offshore islands with dense low heathland.

In this present work we have subdivided the first six of these categories further to assist fire management while at the same time maintaining reference to close links between landform (and soils) and vegetation. We agree with Hopper (1981) that there is no value in further subdivision of the north-west low forest on laterite, nor in the dense low heath on offshore islands.

Readers with an interest in other large areas of natural vegetation within the Albany–Stirling Range–Cape Riche triangle are referred to the work of: Storr (1965), a vegetation map and description of Bald Island south of Cheyne Beach; Enright (1978), a study of vegetation of Torndirrup National Park, south of Albany; Beard (1979), a 1:250,000 vegetation map, and an unpublished vegetation map of the Stirling Range; Newbey (1979), vegetation maps and descriptions of the coastal area from Cape Riche east to the Fitzgerald River National Park; and lastly the Albany Regional Vegetation Survey of Sandiford and Barrett (2010).

Disturbance histories of landscapes and predicted biological differences

As investigated elsewhere (Hopper et al. 2024), Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve is divided into two types of landscapes (Hopper 2009, 2023):

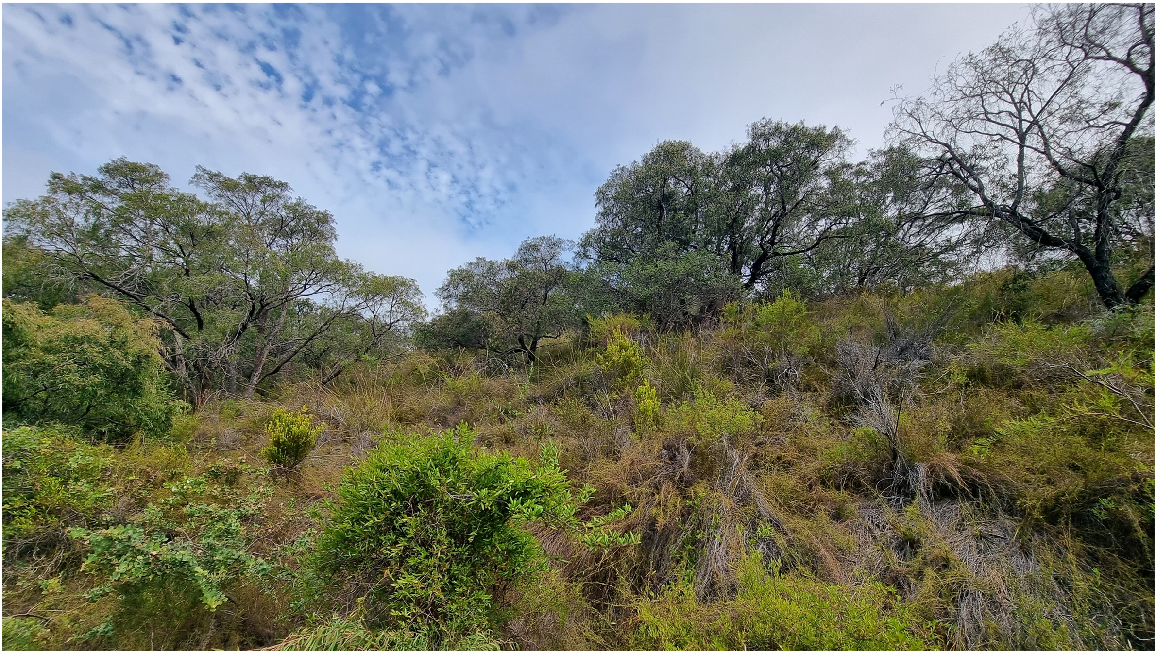

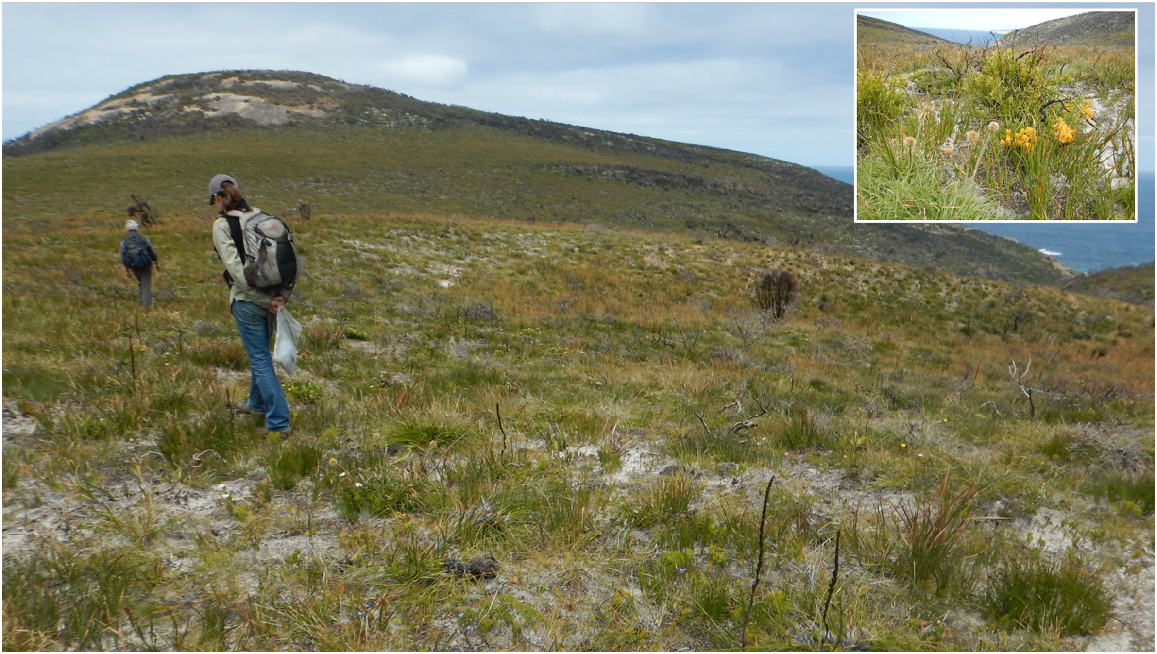

(1) old, climatically buffered infertile landscapes (OCBILs, i.e. mainly the Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner granite inselberg); and (2) young often-disturbed fertile landscapes (YODFELs, i.e. coastlines, isthmus, wetlands, dunes; Hopper 2009, 2023). The disturbance regime on OCBILs is muted and buffered, before and since human occupation (Knapp et al. 2024), whereas YODFELs are regularly disturbed by natural hydrological, erosional and storm damage, as well as human disturbance and occasional local destruction of Agonis flexuosa stems by cockatoos (Fig. 4). Vegetation is likely to be more dynamic on the young lowlands than on the old inselberg granites and associated soils. Fire may occur on both young and old landscapes, but it is predicted to have been more frequent and intense on younger landscapes. We looked for evidence of vegetation change on the Reserve from these perspectives.

Methods used in preparing the vegetation map

The vegetation map was prepared through stereo interpretation of aerial photographs using the methods generally outlined by Küchler (1967). The following images were used:

Coastline: Kalbarri-Israelite Bay Project E51 (Public Works Department); 1:16,000 Black and White. Flown 11 December 1965 (incomplete coverage of the Nature Reserve).

Noisy scrub-bird: Project K63 (Department of Fisheries and Wildlife) CALM; 1:16,000 Black and White and Infrared. Flown 28 May 1970 (incomplete coverage).

Mt Barker 1:250,000 Project M26 (Lands and Surveys Department) Department of Land Administration; 1:40,000 Black and White. Flown 7 February 1973.

Two Peoples Bay Wildlife Sanctuary: Project N74 (Department of Fisheries and Wildlife) CALM; 1:40,000 Black and White. Flown 15 February 1973.

Bunbury to Israelite Bay: Job 770049 Department of Marine and Harbours 1:25,000 Colour. Flown 15 July 1977 (incomplete coverage).

Albany and Environs, W.A.: 035-049 Water Authority of Western Australia 1:40,000 Colour. Flown 17 April 1981.

Features identified by photo-interpretation were confirmed by ground survey. Much of the field work was performed in December 1981–January 1982, and in January and March 2024. However, a considerable proportion of ground verification was based on previous field experience within the Reserve by many of the contributors to this special issue of Pacific Conservation Biology. We gratefully acknowledge this assistance. Moreover, the surveys of granite outcrop flora by Hopper et al. (2024) contributed materially to a better understanding of granite complex vegetation.

Vegetation was classified according to Muir’s (1977) scheme, developed for biological surveys of the Western Australian wheatbelt (Table 2). In this respect we diverge from Beard’s more simplified system (Beard et al. 2013) to capture the richness evident, especially on the Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner granite inselberg.

The accuracy of the vegetation maps reflects, in large part, the skill of Mr Alan Miller who revised the original maps using a photogrammetric plotter. The colour positives were supplied by the Australian Survey Office.

Vegetation change over time

Some important changes in vegetation of parts of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve became evident during the vegetation mapping project and subsequently. The time-series of aerial photographs spanned 16 years. In addition, photographs of a number of identifiable sites around the Reserve were available for comparison with present-day situations. Some early reports and verbal impressions were also supplied by people with long associations with the area.

The principal change in vegetation reflected continuing growth and development by increase in height and cover. For example, in the dune and swale complex south-west of Tyiurrtmiirity/Gardner Lake, an area that was burnt in 1970, and a YODFEL, the swale vegetation expanded outwards and up the dune slopes in the ensuing 12 fire-free years. In the isthmus area dominated by heath, also a YODFEL, the emergents Agonis flexuosa and Banksia sessilis have become more prominent in recent years, now forming a low woodland in many places. Perhaps at a slower pace, the onslaught of dieback disease Phytophthora cinnamomi and cankers on susceptible species is changing vegetation structure in the reverse direction from woodlands to heathlands (R. Hart, G. Freebury, S. Barrett, unpubl. data). At a local scale on younger landscapes, Agonis flexuosa stems 20–40 mm in diameter are often damaged or destroyed by Carnaby’s Cockatoo (Zanda latirostris) in search of wood-boring beetle larvae during winter–spring (Fig. 4).

It is likely that some of these changes resulted from the policy of fire exclusion and containment practised since the Reserve was created. This policy was considered important for protection of the Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird (Danks 1997). As indicated elsewhere in this special issue of Pacific Conservation Biology, the policy has probably contributed to the increase in bird numbers in recent years. However, the more general implications have yet to be assessed. In our mapping we have accurately delineated boundaries as they were in the 1981 photography so that future workers may address questions of change with reliable reference points. We also plotted fire age as at 1992 across the whole Reserve to provide a baseline for future studies (Fig. 5 taken from Orr et al. 1993).

Vegetation map of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve. Numbers and solid lines represent the number of years since fire as at 1992. From Orr et al. (1993).

Lastly, weed invasion is particularly prominent in communities that experience frequent disturbance, whether YODFELs or OCBILs. There are 54 weed species known from the Reserve, 27 collected from the Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner OCBIL inselberg (Hopper et al. 2024). Proportionally, the inselberg granites occupy approximately one third of the Reserve, so having half the weed species on the upland granites highlights the potential for weed invasion. However, the plant communities atop Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner thus far have remained resilient to extensive weed invasion. Typically, weeds occur as isolated individuals in open communities such as moss mats or in postfire communities. The extensive November 2015 fire led to only three new additions to the Reserve’s known flora; Orobanche minor, Trifolium campestre, and Vulpia myuros. This attests to the resilience to weed invasion that protection from frequent fire on the inselberg has achieved.

Perhaps the best example of relatively recent weed invasion is along the rocky strandline adjacent Sinker Reef, where the introduced herbaceous Euphorbia paralias now forms a continuous monospecific band adjacent the limestone rock coast. This species was first introduced to Western Australia in the Albany area in 1927 (Dodd and Keighery 2010). Now one century later it has come to dominate coastal niches experiencing high salt spray.

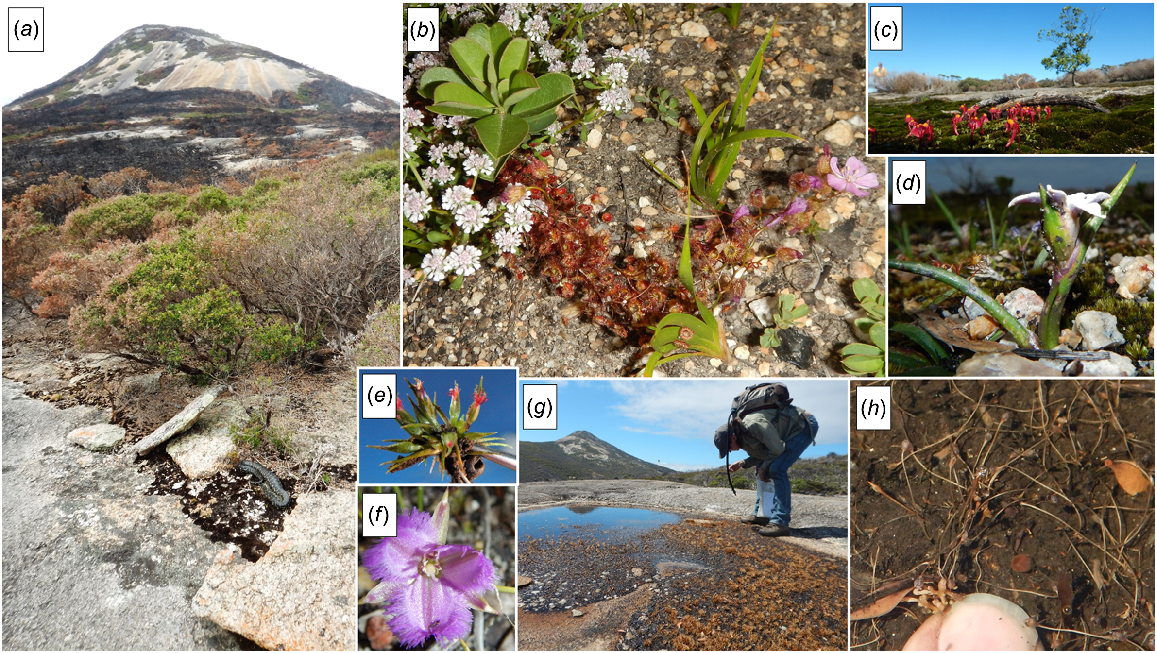

Of greatest concern are the few freshwater gnamma/rock pools on Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner. At Little Beach, for example, just above the major area on coastal granite experiencing regular salt spray, the introduced Cotula coronopifolia dominates a small pool excluding all native aquatics. On Cape Vancouver, the introduced Crassula natans is present in pan gnamma/shallow rock pools, though not yet dominant, allowing native aquatics such as Stylidium inundatum, Centrolepis glabra, and Trithuria austinensis a continuing foothold in these very rare shallow pools.

The vegetation

The following descriptions of plant associations are to be read in conjunction with the vegetation map (Fig. 5). It should be noted that each unit mapped at the 1:25,000 scale will incorporate a degree of physiognomic and floristic variability, so both the boundaries and descriptions represent generalisations. Further, important floristic boundaries are often not coincident with physiognomic boundaries; these latter boundaries generally reflect limits of distribution of a few large species rather than limits of floristic assemblages. It is anticipated that, as the Reserve becomes better known, precise and detailed vegetation maps will be developed from a rich floristic mapping base.

Thirty-three vegetation associations have been recognised for Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve (Table 3). These include a number that appear to be closely related floristically. Together they comprise approximately 15 formations but, because of the variability from place to place within each association, no attempt has been made to develop this hierarchy.

| Tree-dominated communities | |

| T1. Taxandria juniperina Forest/Dense Forest | |

| T2. Taxandria juniperina Low Forest/Scrub/Thicket | |

| T3. Taxandria juniperina Dense Low Forest | |

| T4. Banksia littoralis Low Woodland A/Open Low Forest | |

| T5. Agonis flexuosa Low Forest A/Low Woodland | |

| T6. Jarrah/Allocasuarina Low Forest A | |

| T7. Mixed Low Forest A | |

| T8. Jarrah/Marri/Bullich Low Forest A | |

| T9. Allocasuarina fraserina Low Forest A/Low Woodland | |

| T10. Gully Mixed Dense Low Forest | |

| T11. South-west Peppermint Low Forest A over Scrub | |

| T12. Mixed Low Forest A on Limestone | |

| T13. Melaleuca Low Forest A/Dense Low Forest A | |

| T14. Eucalyptus staeri Low Woodland B | |

| T15. Eucalyptus staeri/Allocasuarina fraseriana Open Low Woodland | |

| T16. Banksia Open Low Woodland | |

| M. Mallee-dominated Communities | |

| M1. Mixed Mallee Shrublands | |

| S. Shrub-dominated Communities | |

| S1. Mt Gardner Thicket | |

| S2. Gully Thicket | |

| S3. Sand Dune Thicket/Scrub | |

| S4. Coastal Dune Scrub | |

| S5. Chorilaena Thicket/Scrub | |

| S6. Swamp Margin Thicket | |

| S7. Isthmus Mixed Dense Low Heath | |

| S8. Headland Mixed Dense Low Heath | |

| S9. Moors Low Heath | |

| S10. Limestone Cliff Heath | |

| S11. Island Heath | |

| S12. Granite Rock Complex | |

| S13. Wet Heath | |

| V. Sedge-dominated Communities | |

| V1. Evandra Dense Tall Sedge Swamp | |

| V2. Lepidosperma Dense Tall Sedge Swamp | |

| V3. Machaerina/Juncus Tall Sedge Swamp |

The distribution of the major units is shown on Fig. 5. Terminology follows Muir (1977). Initial codes indicate trees (T), mallee-dominated communities (M), shrub-dominated communities (S) and sedge-dominated communities (V). Jarrah, Eucalyptus marginata; Marri, Corymbia calophylla; Bullich, Eucalyptus megacarpa; Peppermint, Agonis flexuosa.

About one third of the reserve is occupied by what were heath and shrub thickets in 1992, largely located on the isthmus (Fig. 5). In contrast a much more intricate and diverse complex of vegetation occupied the western wetlands and surrounds (a further third of the area), as well as the eastern granite inselberg of Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner (the last third). Both of these concentrations of complex vegetation mosaics are broken up by substantial areas of free water and dunes (west), or outcrops of bare granite rock (eastern inselberg).

Discussion

Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve may be partitioned into the Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner granite inselberg, an OCBIL or old landscape (Hopper 2009, 2023), occupying a third of the reserve, and the remaining lowlands of isthmus, dunes and swales and wetlands, YODFELs or young landscapes. We found (Fig. 5) that the largest vegetation type in the 1980s was heath or scrub heath on the isthmus. The two trees now overtopping the shrublands, Agonis flexuosa and Banksia sessilis, are each well known for continuous seed gemination between fires and rapid growth (Crosti et al. 2007; Archibald et al. 2010).

The complex of vegetation types associated with wetlands and dunes to the west of the Reserve (Fig. 5) likewise is dominated by species that are fast growing and continuously germinating. Indeed, gidj Taxandria juniperina is a good example. Heavily traded by Aboriginal peoples for thousands of years for making spears (Knapp et al. 2024), gidj today has been allowed to mature around the lakes to form dense tall forests up to 17 m tall. Yet it grows in less favourable sites as a much smaller tree, often producing stems of the right size for making spears just 5–10 years after fire. These are in low forest, scrub or thicket, probably of the life cycle stage most valuable to Noongars as spears for trade. This is a species that rarely is static in its structural attributes if managed well.

By way of contrast, the rich diversity of vegetation types on the slopes and tops of Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner reflects the diversity of substrate on the inselberg. Here species richness is accentuated (Hopper et al. 2024), and plants are generally slow growing with sporadic seedling recruitment to cope with demanding environmental conditions associated with shallow infertile soils near granite outcrops. One well-studied example is the granite banksia (B. verticillata) (Yates et al. 2021). Down to two known live individuals on the Reserve by the early 1980s, this species is likely extinct on the Reserve now due to canker and dieback disease. The species recruits well after fire, but occasional seedlings also appear between fires. The withered carcasses of long-dead individuals were encountered often in the 1980s.

The reduction of the diversity of microhabitats and plant communities on Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner to the solitary ‘Granite Rock communities’ vegetation type belies a richness that repays closer examination (Hopper et al. 2024). Indeed, the rarest habitats of all on the Reserve, such as the seasonal gnamma (rock pools), are scarce indeed but a few were located on Cape Vancouver. Although most of the annuals of these pools are common and widespread, one discovered in a single pool is rare; Trithuria austinensis. Equally, moss mats may be extensive on the granite outcrops and they support a range of annuals and geophytes, some of which are rare e.g. Thysanotus isantherus.

That the large plants on Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner are long-lived and slow growing is evident with the rare lignotuberous hybrid Eucalyptus marginata × megacarpa. Just one solitary individual 12 m across is known on the Reserve. In contrast, several hundred plants of E. conferruminata × cornuta are found on the western slopes, and several E. × missilis (E. angulosa × cornuta) occur low in the landscape adjacent to the isthmus heath and Agonis woodland vegetation.

These observations reinforce the need to minimise disturbance on the Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner old landscapes associated with granite outcrops. There may be a case for some granite species such as Hakea elliptica receiving localised disturbance to reverse apparent senescence (S. Barrett, pers. comm.), although this approach needs careful experiment prior to full implementation. In contrast, a more liberal hand in management may be focused on the younger lowland landscapes, as has happened with the creation of the mown isthmus firebreak maintained for decades now. The ocean’s edge and the ever-moving Tyiurrtyaalup dunes are other places of almost daily change for plant life. It is no coincidence that the rarest birds and mammals on the Reserve are concentrated on Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner. So too, with the rarest plants and habitats (Hopper et al. 2024).

Vegetation mapping, phytogeography and fire management

Apart from helping determine where best to slash firebreaks on the Reserve, the vegetation mapping (Fig. 5) shows immediately where the greatest diversity of vegetation types and therefore species are concentrated. In terms of deliberate fire exclusion, it is strongly recommended that the Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner inselberg continue to receive high priority. That it will burn was evident in November 2015 when a dry lightning storm caused ignitions at many places along the south coast. However, patches that did burn atop the inselberg had enjoyed up to 80 years without fire (Fig. 5), due to the natural firebreak provided by granite outcrops, for other lightning strikes had been contained to small areas over this long largely fire-free interval.

Management of fire among the lowland younger landscapes of dune and wetlands deserves careful planning and delivery. Keeping fires small scale and cool is recommended, although this may be difficult for some kwongkan heathlands. Regular patch-burning may serve conservation outcomes well, and also may attract Noongar interest as we move into the era of comanagement.

Vegetation types from which fire should be excluded as much as possible include the granite complex, and gully formations that have obligate seeders in their dense low forest canopy. Also, the dwarf heath on steep limestone slopes may not take too kindly to regular burning.

A critical learning from this study is the demonstration that vegetation types as well as the flora of the reserve (Hopper et al. 2024) point towards west coast high rainfall affinities, not east and north into the semiarid mallee and shrublands as originally proposed by Diels (1906). It is clear from vegetation mapping (Fig. 5) that the Reserve’s wetlands and granite outcrop communities have more to do with plant communities from the west. Hence the placement of the Reserve in the Bibbulmun Botanical Province (Fig. 2) seems apposite. Yet prescribed burning in the southern forests is being applied aerially at a scale and tempo that may not be appropriate, especially given that wetlands are drying up with global warming, and their vegetation is much more fire-prone than it was just two decades ago (Bradshaw et al. 2018). In this light, Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve is a beacon where managers are willing to take risks to give priority for biodiversity conservation rather than succumb to the political pressure to burn solely for protection of human life and property.

Future research

The next phase in vegetation mapping for the reserve needs to be floristic and quadrat-based. That way we can more precisely define affinities of closely related vegetation types, and better learn when to use fire and when not. Sandiford and Barrett (2010) found that the use of floristic relevés (not quadrats) sufficed to enable a quantitative look at vegetation types, so this approach may suffice for a floristic survey of the Reserve and enable direct comparison with the Sandiford and Barrett’s (2010) work elsewhere in the Albany region.

Joint management approaches with Noongar families who have appropriate cultural authority and long attachment to the area is beckoning and will soon be upon us. This will call upon new skills in both cultures (Knapp et al. 2024). An ever-improving understanding of plant communities and their responses to disturbance regimes will be essential information in the evolution of management. Many will look towards Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve for hope and inspiration that we can manage well under rapidly changing environmental circumstances. Over thousands of years Noongar people did precisely that. We have much to learn from them, their oral history, traditions, and practical science. Above all respectful, rational reverence (Laudine 1991) seems to be an important guiding principle that future conservation managers should emulate.

Conclusion

With the development of an authoritative vegetation map (Fig. 5), the importance of fire management and understanding how fire influences vegetation composition and management actions over time has been better elucidated for Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve. In particular, we are now clear on which plant communities should be protected from fire and which may be burnt with little conservation consequence. As with fauna studies, having the biological and environmental detail of many of the plant species can help with management of the Reserve’s rare and threatened species. The significance of the large granite inselberg at one end of the Reserve forms a dominant physical feature and influences the distribution of the different plant communities mapped. Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner should continue to be protected from fire and other disturbances. We are now also better informed about phytogeographical relations across the Reserve and its surrounding vegetation types.

Vegetation communities on Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve

In the following account, each community (Table 3) is prefixed with a letter signifying as follows: T (tree-dominated communities), M (mallee-dominated communities), S (shrub-dominated communities), and V (sedge-dominated communities). Following a number, dominant species are cited and then Muir’s (1977) vegetation terminology and code are given (Table 2).

Tree-dominated communities

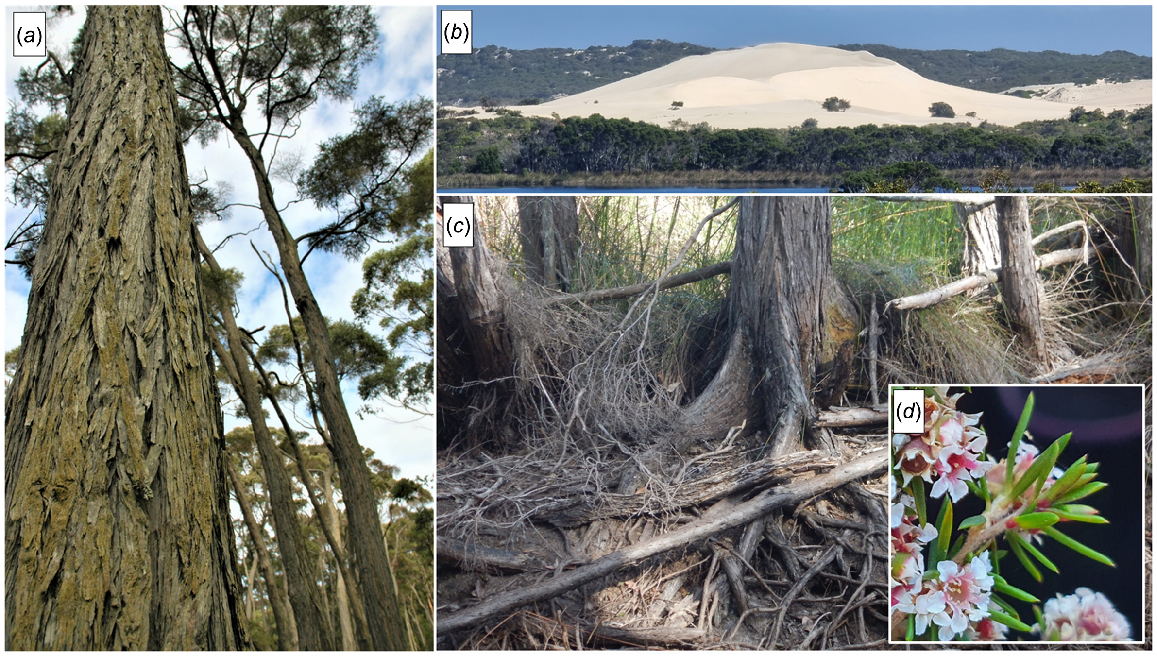

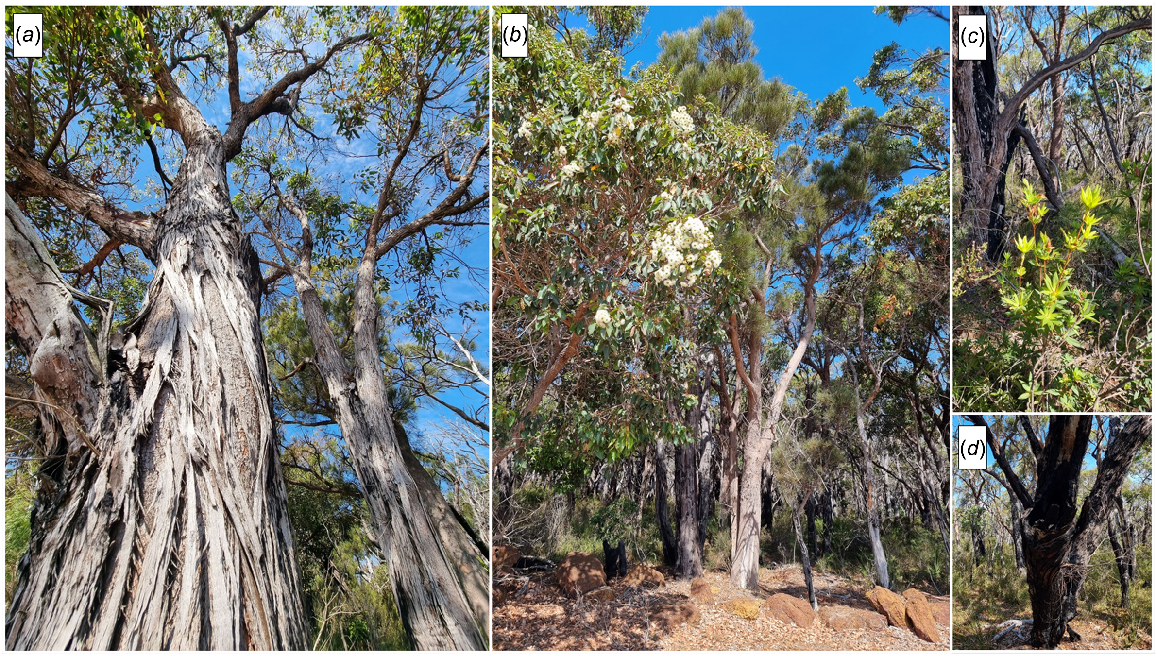

Small patches of this forest type exist on the edges of both Kaiupgidjukgidj/Moates and Tyiurrtmiirity/Gardner Lakes and in low-lying areas with sandy soils between the lakes. Taxandria juniperina may achieve heights of 17 m. In some cases, this upper stratum has collapsed and in other cases the stand has been burnt and there is prolific regeneration from seed. A dense to mid-dense understorey of sedges and shrubs such as Chorilaena anceps, C. rudis, Logania vaginalis, Homalospermum firmum, and Myoporum oppositifolium may be present (Fig. 6).

T1. Taxandria juniperina Forest/Dense Forest (Mc/Md of Muir 1977): (a) bark and straight trunks; (b) flanking Kaiupgidjukgidj/Moates Lake north of Tyiurrtyaalup/Moates dunes; (c) when mature gidj/T. juniperina has prominent buttresses supporting the trunk; and (d) flowers and leaves (May 2021). Photos S. D. Hopper.

Areas of lower Taxandria vegetation, between 3 and 8 m in height, can be found around the lakes. At the western end of Kaiupgidjukgidj/Moates Lake, dense sedges to 0.75 m tall of Machaerina juncea form an understorey. Around the southern margins of Tyiurrtmiirity/Gardner Lake, Taxandria may be associated with Banksia littoralis (Fig. 7).

T2. Taxandria juniperina Low Forest/Scrub/Thicket (Muir LA/S): (a) on Two Peoples Bay Road just south of the bridge over Gardner Creek; (b), (d) adjacent Two Peoples Bay Road on Tandara plateau; (c) at the western end of Kaiupgidjukgidj/Moates Lake with Machaerina juncea understorey. Photos S. D. Hopper April 2017 (a), January 2024 (b, d), March 2024 (c).

At the south-eastern end of Two Peoples Bay, immediately behind a small gently sloping beach, is a small area of Taxandria forest to 10 m tall with a mid-stratum (2–4 m tall) of Callistachys sp. south-coast variant and a lower stratum of tall sedges (to 2 m tall) including Lepidosperma gladiatum, L. effusum, and Ficinia nodosus.

This association, dominated by B. littoralis, is developed in the swales of the dune system, between the lakes and towards the coast. These swales are probably not seasonally waterlogged to the same extent as those that support Taxandria juniperina. This association has an understorey of shrubs (Acacia littorea) and sedges (Lepidosperma gladiatum). Some of the swales contain small areas of more open vegetation (Associations S5 and V3) in their centres (Fig. 8).

T4. Banksia littoralis Low Woodland A/Open Low Forest (Muir LAc-r) at the southern end of the main Two Peoples Bay Beach. (a) Banksia littoralis is growing with Agonis flexuosa and Callistachys sp. South Coast. Inset (b) shows inflorescences, fruits and leaves of B. littoralis. Photos S. D. Hopper January 2023 (a); April 2022 (b).

The dunes between the lakes support 5–8 m tall Agonis flexuosa with a very sparse shrub storey, which includes such species as Acacia littorea, Banksia sessilis, Adenanthos sericeus, and Hibbertia cuneiformis. Desmocladus flexuosa is usually present as a sparse ground cover (Fig. 9).

T5. Agonis flexuosa Low Forest A/Low Woodland A (Muir LAc-D) close to the southern termination of Two Peoples Bay Road on a significant dune system. Shrubs in the foreground include Billardiera heterophylla, Hakea ruscifolia, and Leucopogon altissima, and the sedge is Desmocladus flexuosus. Photo S. D. Hopper January 2024.

The lateritic soils in the northern section of the Reserve are heavily vegetated with jarrah and Allocasuarina fraseriana forest, 10–15 m tall. Occasional trees of marri (Corymbia calophylla) and Banksia grandis are also present. The dense to mid-dense shrub storey to 2 m tall contains species such as Xanthorrhoea preissii, Bossiaea linophylla, Agonis theiformis, Beaufortia decussata, Acacia leioderma, and Leucopogon verticillatus (Fig. 10).

T6. Jarrah/Allocasuarina Low Forest A (Muir LA/Lbi), north of Two Peoples Bay Road on the north-west boundary: (a) jarrah Eucalyptus marginata trees; (b) marri Corymbia calophylla in white flower, and Allocasuarina fraseriana, with large stones of laterite conglomerate; (c) Leucopogon verticillata; and (d) burnt out jarrah. Photos S. D. Hopper January 2024.

The area near the Reserve office and including the present picnic ground is dominated by trees 10–15 m tall of Agonis flexuosa, Eucalyptus megacarpa (bullich), and E. cornuta (moin). Except for the grassed picnic area, this forest has a dense understorey 2–4 m tall dominated by Bossiaea linophylla, Acacia cyclops, Chorilaena anceps, and Acacia littorea (Fig. 11). Towards the eastern part of this stand, the low forest is composed almost entirely of Agonis flexuosa (Fig. 12). A similar forest type occurs along the margins of the Angove River. The Angove River stands were badly burnt in the early 1980s and most were coppicing. Those stands include low trees of Melaleuca cuticularis and understorey shrubs and include Pultenaea reticulata, Boronia crenulata, B. gracilipes, and Hypocalymma cordifolium.

T7. Mixed Low Forest A (Muir LAc) of bullich Eucalyptus megacarpa, moin E. cornuta, and wonnil, wandil Agonis flexuosa, with large sedges of Lepidosperma effusum on the Two Peoples Bay Heritage Walk near the Visitor Centre adjacent the coast. Insets are: (a) dark rough basal bark of E. cornuta alongside smooth barked E. megacarpa; (b) fruits of E. megacarpa; and (c) fruits of E. cornuta. Photos S. D. Hopper January 2024.

A small stand of this forest type occurs on sands overlying a podzol material on granite at the headwaters of Firebreak Gully. Trees 7–10 m tall of Eucalyptus marginata, Corymbia calophylla, E. megacarpa, with occasional Allocasuarina fraseriana occur over a mixed dense shrub stratum in which Xanthorrhoea preissii, Pteridium esculentum (bracken), Hibbertia furfuracea, Acacia leioderma, Taxandria parviceps, and Boronia spathulata are common. This unit grades into Allocasuarina Low Forest (T9) downslope along the gully (Fig. 13).

This forest type is found downslope from the previous type and below the granite outcrops on either side of Firebreak Gully. Allocasuarina fraseriana attains a height of 6–10 m and occasional Eucalyptus marginata, E. megacarpa, and Agonis flexuosa also contribute to the tree canopy. The mid-dense shrub stratum (Muir Heath A/B) is dominated by Melaleuca thymoides, Bossiaea linophylla, and Adenanthos cuneatus. The sedge Cyathochaeta sp. and Anarthria scabra are also important components of the understorey (Fig. 14).

Some of well-watered gullies of the Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner area have a dense forest vegetation 4–8 m tall in which Eucalyptus cornuta, E. conferruminata, Corymbia calophylla, Hakea elliptica, and Gastrolobium sp. are important species (Figs 15, 16).

T10. Gully Mixed Dense Low Forest (Muir LA/LB d) occupies a series of steep gullies running down to the Southern Ocean from Hill 700 and north-westwards. Moin Eucalyptus cornuta is the lighter green canopy in the foreground emergent from a dense thicket of Hakea drupacea and Taxandria marginata. Borongorup/Porongurups are on the horizon, and Tyiurrtyaalup/Moates Dunes are top left. Squatting in the foreground is the late Ranger Graeme Folley. Photos S. D. Hopper February 1981.

This association is confined to areas of consolidated sands in the south-western part of the Reserve, to the west of the sand dune. The upper canopy consists of Agonis flexuosa 5–8 m tall with occasional Banksia littoralis. There is a prominent shrub component that includes Acacia littorea and Bossiaea linophylla at most sites, whereas tall shrubs (2–4 m tall) Adenanthos sericeus, Allocasuarina lehmanniana, and Banksia sessilis are less widespread. This association is floristically similar to that found to the east of the dune on the sand ridges (T5). Towards the south coast it becomes lower in height and grades into coastal dune scrub/thicket (S4). Adjacent to the track into the large and mobile sand dune there is an area of this association that may have been burnt more recently than the remainder; it is both lower and more open, but otherwise floristically similar to T11. It is labelled T11/S4 to indicate its scrub/open scrub classification (Fig. 17).

This association is of limited areal extent in the Reserve, being confined to two small areas in the south-west. Along the western boundary, the shallow aeolian sands overlie a pavement of limestone with some iron enrichment; this limestone improves the water retention properties of the soil. The association comprises scattered mature paperbarks (Melaleuca cuticularis) to 10 m tall mixed with Banksia seminuda. Eucalyptus staeri, and Agonis flexuosa 6–9 m tall. A mid-storey thicket (to 4 m tall) includes Hakea elliptica, Banksia sessilis, Allocasuarina lehmanniana, and Agonis flexuosa. Sparse low shrubs (including Leucopogon obovatus) and sedges are present (Fig. 18).

The area adjacent to where Tyiurrtmiirity/Gardner Creek flows from Gardner Lake supports a forest 6–10 m in height dominated by Melaleuca croxfordiae, M. cuticularis, M. raphiophylla, and M. preissiana with some Agonis flexuosa. The sparse shrub storey includes Hibbertia furfuracea 1–2 m tall and low sedges are present. The margins of Tyiurrtmiirity/Gardner Creek are fringed by a narrow band of Melaleuca cuticularis 3–5 m tall with dense sedges to 2 m tall. M. preissiana (trees to 4 m) also occurs in a swamp south of Goodga River in the western boundary area (Fig. 19).

T13. Melaleuca Low Forest A/Dense Low Forest A (Muir LAd/c). Melaleuca croxfordiae forms dense entangled forest on the alluvial flats associated with Gardner Creek where Two Peoples Bay Road bridges the creek. It forms similar dense low forests down the steep granitic gullies of Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner, and on other granite inselbergs to the west. Photos S. D. Hopper January 2024.

The sandy slopes away from lateritic uplands in the areas to the north of Kaiupgidjukgidj/Moates Lake are vegetated with sparse trees of Eucalyptus staeri, Allocasuarina fraseriana, Banksia attenuata, and B. coccinea to 10 m in height. A mid-dense heath containing species such as Beaufortia anisandra, Melaleuca striata, Adenanthos cuneatus, Calytrix asperula, and Dasypogon bromeliifolius underlies the trees (Fig. 20).

T14. Eucalyptus staeri Low Woodland B (Muir LBi) on sandy slopes away from laterite north of Two Peoples Bay Road in the north-west sector of the Reserve, looking south-east to Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner on the horizon. The orange-flowered plant in the foreground is Nuytsia floribunda. Photo S. D. Hopper January 2024.

Towards the western boundary of the Reserve there is a series of dunes where the tree stratum is exceedingly sparse and the vegetation might be better described as a low heath with emergent Banksia coccinea. Important components of the shrub stratum include Beaufortia anisandra, Melaleuca thymoides, Taxandria sp., Adenanthos cuneatus, Jacksonia spinosa, Dasypogon bromeliifolius, and Xanthosia rotundifolia. Much of this vegetation type has been affected by Phytophthora cinnamomi and has, as a result, become more open and changed in floristic composition. Banksia coccinea, Leucopogon flavescens, and Jacksonia spinosa are nearly eliminated (Fig. 21).

T15. Eucalyptus staeri/Allocasuarina fraseriana Open Low Woodland (Muir LBr) on the west boundary of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve. A low woodland almost converted to low kwongkan heath by dieback disease. Just a few scattered korran Banksia coccinea remain emergent from the kwongkan as reminders of the once great floristic displays that are now gone. Foreground plant with dark purple red flowers is Beaufortia anisandra. (a) Banksia coccinea in full bloom October 2005; (b) new growth on B. coccinea January 2021, for how much longer? and (c) Beaufortia anisandra flowers and fruit. Photos S. D. Hopper, main one January 2024.

Aerial photographs reveal a conspicuous, sandy, almost bare, patch along the western track. It is not clear whether this is an old sand blowout or a revegetating infilled swamp. It is characterised by a wealth of Banksia. The upper stratum is composed mainly of Taxandria juniperina, Banksia attenuata, B. coccinea, B. grandis, B. littoralis, B. quercifolia, B. occidentalis, Agonis flexuosa, and Adenanthos sericeus. The understorey is sparse but includes Bossiaea linophylla, Styphelia discolor, Isopogon formosus, and Latrobea sp. The lowest stratum includes Conostylis setigera, sedges, and the Albany Pitcher Plant, Cephalotus follicularis.

Mallee-dominated communities

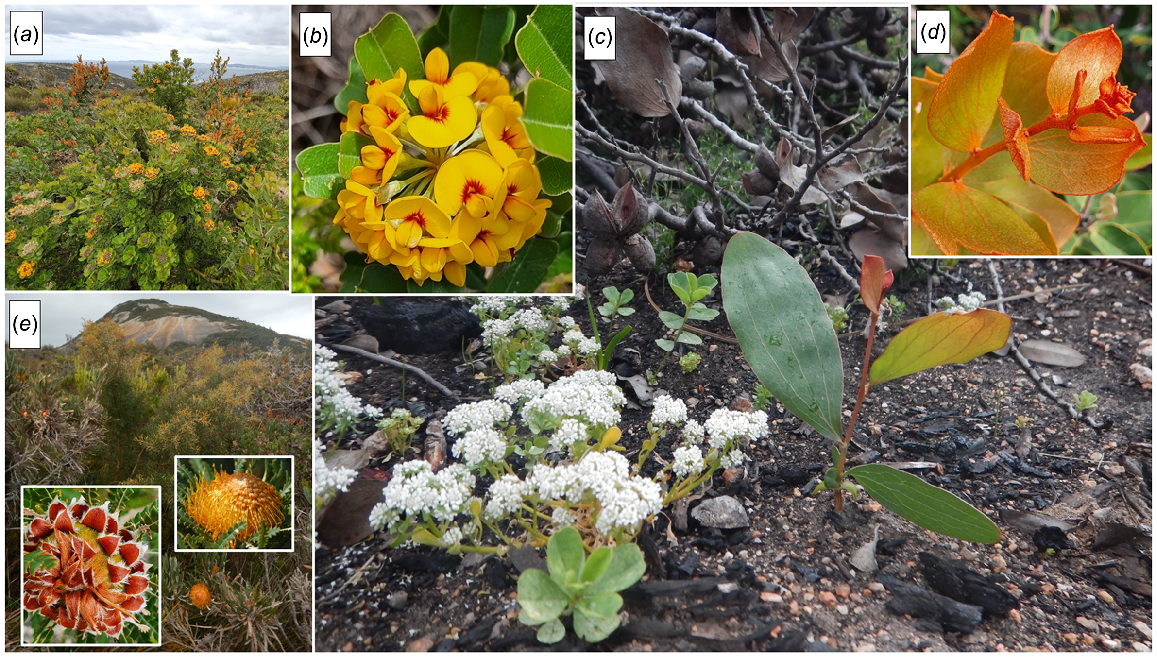

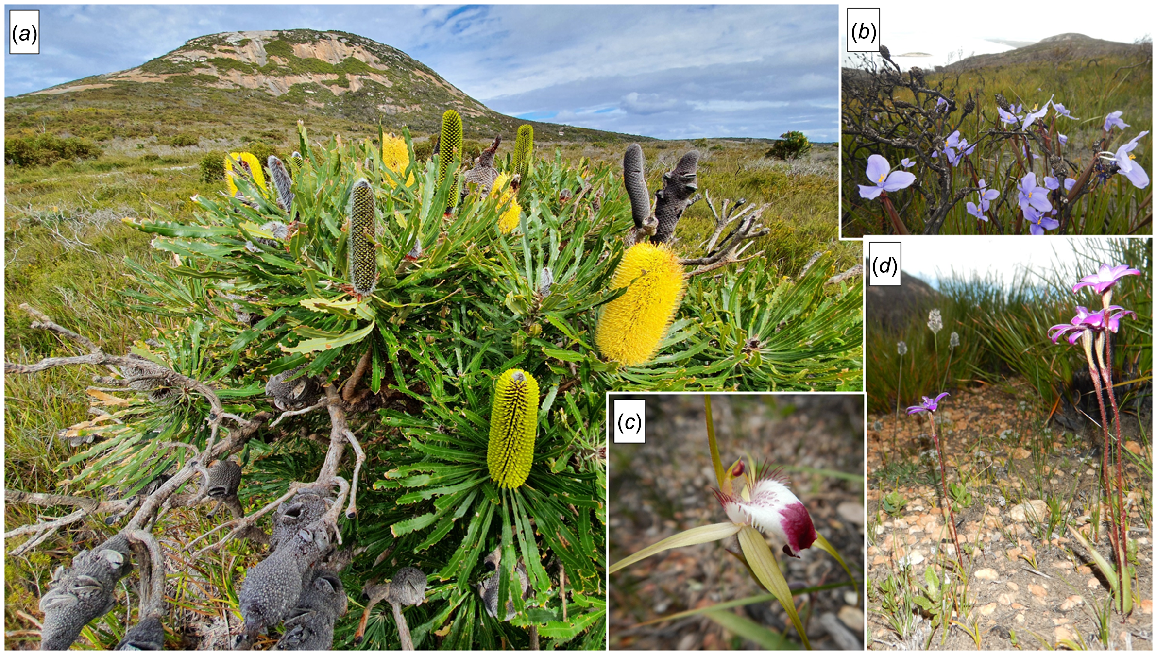

Patches of mallee vegetation are spread throughout the Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner headland, where they are often indistinguishable on aerial photography from the Mt Gardner Thicket (S1). Species include Eucalyptus angulosa, E. cornuta, and E. goniantha, as well as rare hybrids E. × missilis and E. marginata × megacarpa. In addition, small clumps of mallee occur in areas such as that on Tick Flat. Eucalyptus angulosa exhibits exceptional variation in form and habitat occupied, from a diminutive shrub less than half a metre high on beach foredunes or the Moors north of Cape Vancouver, to robust tree mallees 6–7 m tall above Little Beach (Figs 22, 23).

M1. Mixed Mallee Shrublands (Muir KS). Quarar Eucalyptus angulosa perhaps demonstrates the greatest structural and habitat diversity within a species of mallee on the Reserve: (a) sandy soils are preferred – these plants were on the foredunes at Little Beach January 2017; (b) robust mature mallee 7 m tall at Little Beach December 2022; (c) one year-old seedling December 2016 Vancouver Peninsula; (d) 30 cm resprouts in December 2016 adjacent the Moor north of Cape Vancouver; and (e) tree-mallee formation dominant on slopes at Little Beach October 2005. Photos S. D. Hopper.

M1. Mixed Mallee Shrublands (Muir KS). One of the rarest and oldest plants on Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve is this single mallee 12 m across of hybrid origin – Eucalyptus marginata × megacarpa. Here it is flowering with one of its parents (jarrah, E. marginata) in the background on the upper western slopes of Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner. Photo S. D. Hopper December 2020.

Shrub-dominated communities

Fringing the exposed granitic outcrops of the Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner headland is a dense to mid-dense thicket 2–4 m in height dominated by such species as Hakea elliptica, H. trifurcata, Allocasuarina trichodon, Gastrolobium sp., Banksia formosa, Taxandria marginata, and T. parviceps. In some areas, Xanthorrhoea preissii is conspicuous (Fig. 24).

S1. Mt Gardner Thicket (Muir Sd/c). Long unburnt shrublands on Mt Gardner form impenetrable thickets more than 2 m tall. Especially prominent in these thickets are Gastrolobium bilobum (a, b, c), Hakea elliptica (c, d) and Banksia formosa (e). All three species are obligate seeders, killed as adults by fire and germinating prolifically to replace the population. An unusual player in such dramatic events is the white-flowered Eremosyne pectinata (c). This species, the only representative in its endemic south-west Australian family Eremosynaceae, rapidly develops a seed bank the first year after fire and waits until the next year for the adult plants to return. Photos S. D. Hopper – (c) October 2016; the rest in November 2020.

Many of the gullies on Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner that do not support forest have a thicket vegetation to 3 m tall that may be dominated by Gastrolobium bilobum and G. sp. with some Calllistachys sp. South Coast and Chorilaena quercifolia sp. Melaleuca croxfordiae may be present. Stunted mallees of Eucalyptus marginata and Corymbia calophylla are also present. The gully at the eastern end of the limestone cliff heath has Adenanthos cygnorum and Banksia sessilis with Agonis flexuosa tickets further up the gully.

The steep dunes fronting Two Peoples Bay and dissected by Tyiurrtmiirity/Gardner Creek have a thicket of Agonis flexuosa (up to 5 m tall) and Adenanthos sericeus (up to 3 m) interspersed with shrubs to 2 m of Spyridium globulosum, Hibbertia cuneiformis, Acacia littorea, A. cyclops, A. cochlearis, Scaevola crassifolia, and Olearia axillaris. A sparse ground cover of Desmocladus flexuosus is often present. Plants of Spinifex hirsutus, Euphorbia paralias, and Cakile maritima are prominent on the seaward margins of dunes (Fig. 25).

S3. Sand Dune Thicket/Scrub (Muir Sc/i). The steep dunes fronting Two Peoples Bay and dissected by Tyiurrtmiirity/Gardner Creek have a thicket of Agonis flexuosa (up to 5 m tall) and Adenanthos sericeus (up to 3 m) interspersed with shrubs to 2 m. Pink flower in the foreground is the South African weed Senecio elegans. Photos S. D. Hopper October 2005.

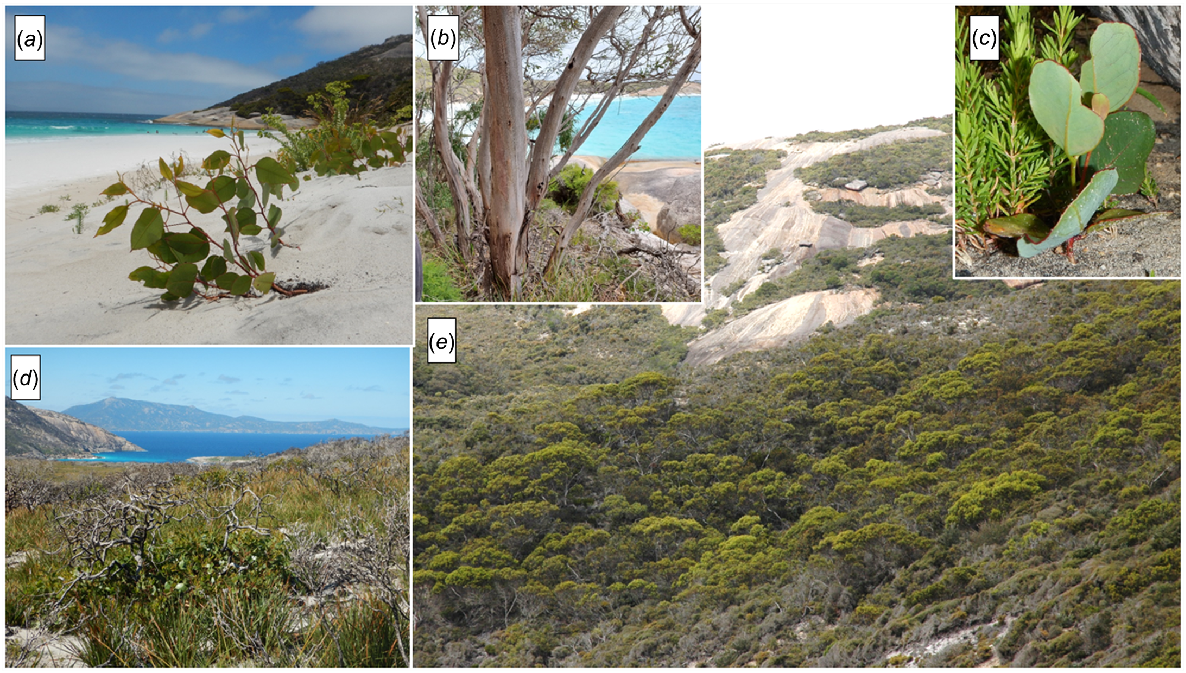

The recent dunes west of Rocky Point have a scrub vegetation that intergrades with the peppermint forest (T11) further inland. Banksia praemorsa forms a sparse to very sparse upper stratum up to 6 m tall. Banksia sessilis (to 3 m) and shrubs (to 2 m) of Acacia littorea, Spyridium globulosum, and Adenanthos sericeus form much of the understorey. This association is also found behind Little Beach where aeolian limestone and calcareous sands occur (Fig. 26).

The large swale, centred about 300 m west-north-west of the Reserve office, consists of a mid-dense thicket of Chorilaena anceps of approximately 3 m in height with the sword sedge (Lepidosperma gladiatum) over dense Scaevola crassifolia, Acacia littorea, and sedges. Trees of Banksia littoralis 4–5 m tall are scattered throughout the swale. In some of the swales between the dune and Tyiurrtmiirity/Gardner Lake there is a similar association with Chorilaena anceps, C. rude, Logania vaginalis, Allocasuarina lehmanniana, Hakea varia, Spyridium globulosum, and stunted Agonis flexuosa. A dense ground cover of Desmocladus may be associated with those shrub associations.

On the northern margins of Tyiurrtmiirity/Gardner Lake there is a broad band of thicket vegetation that includes dense stands of Homalospermum firmum to 2.5 m tall. Associated species include Astartea pulchella, Kunzea ericifolia, and Jacksonia spinosa. This association may have Callistachys sp. South Coast stands. The peaty soils often support populations of Cephalotus follicularis (Fig. 27). The western edges of Miialyiiny/Angove Lake are steeper than the edges of Gardner Lake; there the fringing thicket is narrow and it intergrades with Eucalyptus staeri/Allocasuarina fraseriana woodland (T15).

S6. Swamp Margin Thicket (Muir Sc). Cephalotus follicularis favours this habitat, flowering prolifically after fire (right). It usually hugs the lignotuberous bases of Homalospermum firmum (middle), which are embedded in Empodisma peatland. Photos taken in February 2014 south of Two Peoples Bay Road and north of Kaiupgidjukgidj/Moates Lagoon after the 2012/13 fire. Photos S. D. Hopper.

The area of consolidated, well drained, calcareous sand dunes between Tyiurrtmiirity/Gardner Lake and the granitic outcrops of Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner consists mainly of a dense low heath (shrubs to 1 m). Shrubs include Acacia cochlearis, Melaleuca thymoides, Jacksonia horrida, Allocasuarina humilis, Adenanthos cuneatus, Leucopogon obovatus, and other epacrids. The tussock sedge Cyathochaeta avenacea is prominent. Scattered emergent tall shrubs of Agonis flexuosa and some mallee Eucalyptus angulosa occur in clumps. Banksia littoralis and B. attenuata trees may be present. Stands of emergent B. sessilis are generally associated with outcrops of coastal limestone (Fig. 28).

The sandy soils associated with granitic outcrops of the Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner headland are generally noncalcareous and, as a result, Banksia sessilis is uncommon. The heath vegetation is otherwise floristically similar to that on the isthmus. Prominent species include Melaleuca thymoides, M. striata, Leucopogon spp., Cyathachaeta avenacea, Anarthria scabra, and Dasypogon bromeliifolius. Emergents include Allocasuarina fraseriana, Nuytsia floribunda, Agonis flexuosa, and some mallee (Fig. 29).

S8. Headland Mixed Dense Low Heath (SCd) is common on Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner and rich in species including Banksia attenuata (a). After fire, in October 2016, many species were conspicuous in flower including Patersonia occidentalis (b), the threatened local endemic Caladenia granitora (c), and the common widespread Elythranthera brunonis (d). Photos S. D. Hopper.

In the area referred to as The Moors, near Cape Vancouver, limestone overlies the granite and soils are calcareous and skeletal. The vegetation on this exposed site is severely wind-pruned and open. Shrubs are generally less than 0.5 m in height, including the most prostrate form of Nuytsia floribunda known (Fig. 30).

S9. Moors Low Heath (SC/D c) north of Cape Vancouver a year after fire. Vertical black inflorescences of Haemodorum spicatum are evident in the foreground. Inset shows Dasypogon bromeliifolius with drumstick inflorescences 50 cm tall and dwarf yellow-flowering Nuytsia floribunda. Scale provided by Megan Dilly and Dr Anne Cochrane. Photo S. D. Hopper December 2016.

The steep limestone cliffs above Sinker Reef support a heath that is characterised by the presence of Banksia praemorsa, Adenanthos spp., and Olearia axillaris to 1.5 m tall. Shrubs include Acacia littorea, Scaevola crassifolia, Melaleuca pentagona var. subulifolia, Pimelea ferruginea, Spyridium globulosum, and Leucopogon parviflorus (Fig. 31).

S10. Limestone Cliff Heath (SB c/d) is very distinctive in the otherwise acidic soils found on Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve. Here near the termination of the Sinker Reef track, Dr Robert Wyatt (University of Athens, Georgia, USA) provides scale, and Black Rock lies offshore. Photo S. D. Hopper May 1984.

The islands off the coast that are included within the Reserve have a species-poor heath vegetation that is confined to limited areas where some soil has developed. Vegetation on Coffin Island consists of a dense shrub layer of Rhagodia baccata (1 m tall and to 2 m tall in depressions) with scattered clumps of Anthocercis viscosa. This is fringed by Carpobrotus virescens, Poa poiformis, and Lomandra rigida (Fig. 32).

S11. Island Heath (Muir SDc). Strenuous conditions of big storms, salt spray and shallow soils deliver a depauperate, often diminutive flora on islands on the Reserve. Here Coffin Island is seen from north-west (top right) and the south at Cape Vancouver (top left); False Island with Nornarup/Nanarup behind is closer from the same vantage point. Photos S. D. Hopper December 2016.

Exposed sheets and boulders of granite on the Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner headland support varied vegetation in pockets of shallow soil (Figs 33, 34). Prominent species include Taxandria marginata, Anthocercis viscosa, Verticordia plumosa, and Andersonia sprengelioides. Borya nitida, mosses, and orchids are also important. There is a conspicuous rock supporting this complex beside the main road and just east of the bridge over Gardner Creek (Rock Island). For a comprehensive discussion of the granite outcrop flora on the Reserve see Hopper et al. (2024).

S12. The Granite Rock Complex (Muir SDi/Pi/Xi) has a plethora of distinct plant communities in close proximity, depending upon soil depth and available moisture. Here brown moss mats afford some protection for annual herbs and geophytes. Borya nitida takes over when some soil is present, leading to dwarf shrubs such as the pink-flowered Pimelea rosea and the aptly named tapeworm plant Platysace compressa. Taller plants favour deeper soils. Photo S. D. Hopper December 2020, 5 years after fire.

S12. Granite Rock Complex (Muir SDi/Pi/Xi). Threatened habitats on granite complexes in Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve: (a) granite offers some refuge from fire as seen here for a carpet snake in this pocket of Taxandria marginata escaping the November 2015 wildfire on Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner; (b) white-flowered annual Poranthera florosa, geophyte Drosera drummondii, and seedlings of Gastrolobium bilobum and Lepidosperma one year after the fire; (c) easily burnt mossmats are home for geophytes Utricularia menziesii; (d) Tribonanthes violacea; and (f) Thysanotus isantherus. Arguably the rarest habitats on the Reserve are (g) shallow gnamma/rock pools (Megan Dilly for scale)), home to very rare annuals including (e) Centrolepis glabra and (h) Trithuria austinensis. Photos S. D. Hopper. November 2015 (a) and Spring 2016 (the rest).

To the north and west of Kaiupgidjukgidj/Moates Lake there are numerous patches of variable low heath to 1 m tall in areas that may be seasonally waterlogged. Some sites contain emergent Callistemon glaucus to 2 m tall. The low shrub stratum comprises such species as Actinodium cunninghamii, Andersonia simplex, Sphenotoma gracile, and Banksia nutans (Fig. 35).

Sedge-dominated communities

The low-lying swampy areas to the north and west of Kaiupgidjukgidj/Moates Lake and along Goodga River are densely vegetated with Evandra aristata to 1 m tall. The shrub species Leucopogon distans and Melaleuca thymoides are conspicuous. Areas of Xyris lanata, Leptocarpus scariosus, and Hypolaena exsulca are in this unit (Fig. 36).

The swamp around the picnic ground is dominated by Lepidosperma. effusum to 3 m tall. In some areas Typha domingensis has invaded. The swamp margins may contain Gahnia spp., Lepidosperma sp., and Ficinia nodosus (Fig. 37).

V2. Lepidosperma Dense Tall Sedge Swamp (Muir VTd) is found at the south end of Two Peoples Bay, sometimes flanked by Callistachys sp. South Coast. The distinctive elevated midrib of the 2–3 m culms of Lepidosperma effusum differentiate the species along with its large size from gerbain L. gladiatum. Photos S. D. Hopper January 2024.

Extensive areas of Machaerina articulata with some Juncus kraussii occur at Miialyiin/Angove Lake and also fringe Tyiurrtmiirity/Gardner and Kaiupgidjukgidj/Moates Lakes. In some areas these sedge swamps intergrade with fringing Leptocarpus scariosus and Hypolaena exsulca sedges. A similar association can be found in seasonally waterlogged swale areas between the dune and Tyiurrtmiirity/Gardner Lake. Machaerina juncea and Ammothryon grandiflorum are prominent in these swamps (Figs 38, 39).

V3. Machaerina/Juncus Tall Sedge Swamp (Muir VTc/i) are found flanking Kaiupgidjukgidj/Moates Lake. Wardaruk Machaerina articulata was used by Noongars as a snorkel to facilitate hunting waterfowl. Photo S. D. Hopper February 2014.

V3. Machaerina/Juncus Tall Sedge Swamp (Muir VTc/i) here seen looking west along the southern shoreline of Tyiurrtmiirity/Gardner Lake with Machaerina juncea in the foreground (left), and looking south-east from the western end of Kaiupgidjukgidj/Moates Lake across Wardaruk (Machaerina articulata) exposed by very low water levels during summer drought. Photos S. D. Hopper March 2024.

Lastly, unclassified communities of some significance on the Reserve are the simple gatherings of a few species able to tolerate very high levels of disturbance on inland sand dunes at Tyiurrtyaalup south of Kaiupgidjukgidj/Moates Lake, and herbfields flanking Sinker Reef on the south coast where massive limestone outcrops on the strand (Fig. 40).

Simple communities on the harshest of substrates in Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve include Ficinia nodosa/Agonis flexuosa sedgelands and shrublands regularly engulfed by the massive Tyiurrtyaalup dune system adjacent Kaiupgidjukgidj/Moates Lake (left) and the weed Euphorbia paralias adjacent Sinker Reef on massive coastal limestone, looking east to Cape Vancouver (right). Photos S. D. Hopper March 2024.

Conflicts of interest

Living authors declare no conflicts of interest. Deceased authors had no conflicts of interest at the time of original submission of the predecessor to this paper.

Declaration of funding

This research would not have been possible without the invaluable assistance of salaries and operating budgets paid for by the Western Australian Government (Departments of Fisheries and Wildlife, Conservation and Land Management, Kings Park and Botanic Garden, Botanic Gardens and Parks Authority), The Royal Botanic Gardens Kew, and The University of Western Australia.

Acknowledgements

Author AJM Hopkins was a contributor to the original version of this paper, which was written for a special bulletin of CALMScience on the natural history of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve. The paper was subject to peer review, revised, and accepted for publication in 1991. The special bulletin was never published. In resurrecting the papers collected for the special bulletin, in order to publish them over 30 years later in the special issue of Pacific Conservation Biology, author AJM Hopkins was deceased and JM Harvey became gravely ill after first submission of the present manuscript for review by referees. Accordingly, SDH and AAEW updated the paper and edited it for final publication. Authors AJM Hopkins and JM Harvey would have met criteria for authorship if alive/contactable, so they are included as authors on this version. Sadly Judith Harvey passed away 2 weeks prior to the authors receiving proofs of the paper. We are grateful to the Hopkins family for their agreement and encouragement to proceed with preparing this paper to honour the memory of their late husband/father. Hopefully the deceased lead co-author would have been pleased with the published outcome. This paper and associated vegetation classification was originally written by the first three co-authors, with the fourth co-author updating the literature cited, the nomenclature used, reconstructing the text to highlight scientific issues concerning vegetation mapping, adding sections on weed invasion and cockatoo damage, and contributing the photographs and maps, as earlier figures were not recovered despite a thorough search. We thank the late Graeme Smith and Les Moore for providing their unpublished observations on the vegetation and for their constructive and detailed comments on the map and descriptions. Dr Neil Gibson and Barry Muir also made valuable contributions with their constructive criticisms of an earlier draft of the text, as did Dr Sarah Barrett more recently. Nomenclatural updates have relied extensively on the Western Australian Herbarium’s Florabase, summarised in Hopper et al. (2024). We are grateful for the Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions’ permission to access Florabase, and for scientific flora collecting licences. The last three co-authors are grateful to Dr Denis Saunders AM for enlightened editorship, and to Dr Judy West AO and an anonymous reviewer for helpful suggestions to improve the updated manuscript. Also, students in the 2019 course of University of Western Australia’s unit Saving Endangered Species and Dr Barbara Cook are thanked for measuring cockatoo impacts on Agonis flexuosa.

References

Archibald RD, Bradshaw J, Bowen BJ, Close DC, McCaw L, Drake PL, Hardy GESJ (2010) Understorey thinning and burning trials are needed in conservation reserves: the case of Tuart (Eucalyptus gomphocephala D.C.). Ecological Management and Restoration 11, 108-112.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Beard JS (1980) A new phytogeographic map of Western Australia. Western Australian Herbarium Research Notes 3, 37-58.

| Google Scholar |

Beard JS (2001) A historic vegetation map of Australia. Austral Ecology 26, 441-443.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |