Plant diversity on the edge: floristics, phytogeography, fire responses, and plant conservation of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve in the context of OCBIL theory

Stephen D. Hopper A * , J. M. Harvey B , A. J. M. Hopkins C , L. A. Moore D and G. T. Smith E

A * , J. M. Harvey B , A. J. M. Hopkins C , L. A. Moore D and G. T. Smith E

A

B Formerly of

C Deceased. Formerly of

D Uncontactable. Formerly of

E Deceased. Formerly of

Abstract

There have been few long-term studies of the flora, phenology, and ecology of specific reserves in the species-rich flora of the Southwest Australian Floristic Region.

This project, extending over five decades, aimed to develop an authoritative flora list and acquire data on phenology, threatened species, endemism, old and young landscapes, phytogeography, old lineages, and fire responses at Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve.

The study used botanical collection on repeat surveys, herbarium studies, granite outcrop surveys and comparative phytogeographic analyses from maps on the Western Australian Herbarium’s Florabase.

Floristic survey recovered 853 taxa, 26% of those known in the Albany local government area. Possibly as many as 950–1000 taxa will be found in the future. The herbarium collections are the second largest of any conservation reserve in the Albany area. Flowering was most evident in spring and least in autumn. Three declared rare species and 20 conservation priority species were identified, as were short-range endemics, old clades, and natural hybrids.

The flora is dominated by species predominantly from wetter forest regions. Consequently, Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve is correctly placed within the Bibbulmun Botanical Province. Several hypotheses of OCBIL theory (which addresses old, climatically-buffered, infertile landscapes) were supported, with increased local endemism, ancient clades, and reduced rates of natural hybridisation identified for the granite inselberg OCBIL Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner.

Long term studies are invaluable for plant inventory. Continuing the minimal use of prescribed burning is advocated from plant data, in support of approaches to help conserve threatened animals.

Keywords: ancient lineages, flowering phenology, granite outcrop flora, herbarium studies, natural hybridisation, OCBIL, phytogeography, YODFEL.

Introduction

The Southwest Australian Floristic Region (SWAFR sensuHopper and Gioia 2004; Gioia and Hopper 2017; Fig. 1) continues to be a source of novel botanical discovery of global significance. It has experienced close to a doubling of the estimated species present over the past 50 years, from 3600 (Marchant 1973) to 6870, requiring significant review of its floristic phytogeography (Gioia and Hopper 2017). This growth in taxonomic recognition is due to a combination of much improved collections, changes towards biological species concepts, and new incisive scientific techniques, especially DNA sequencing and molecular phylogenetic studies.

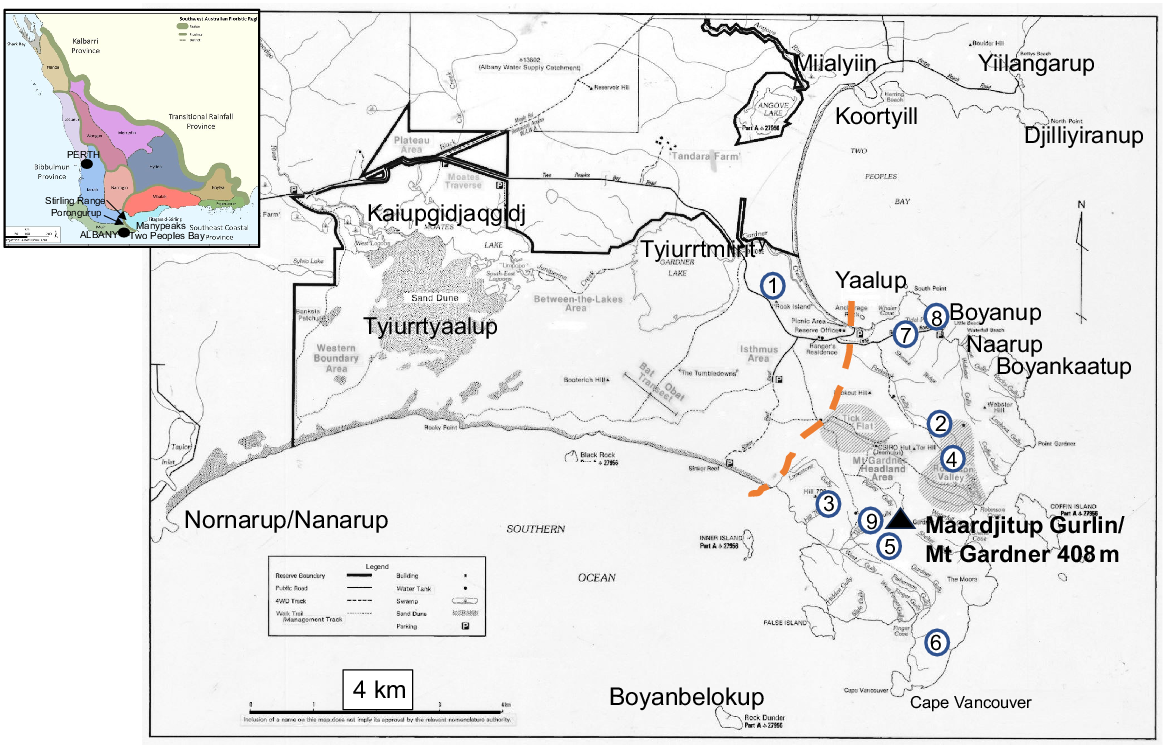

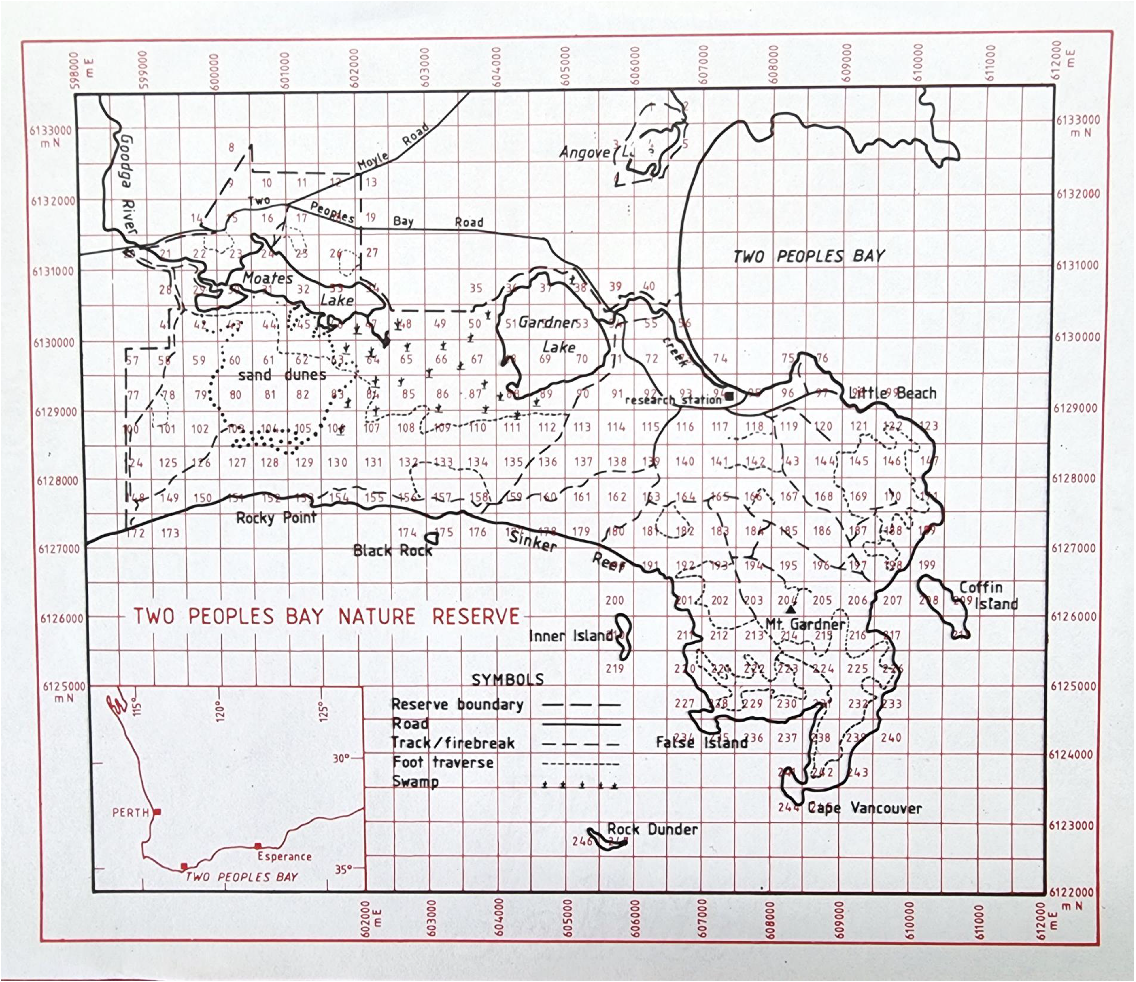

Map of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve showing place names used in the text, Table S1 and Table S2 available as Supplementary material. Blue encircled numbers are granite outcrops surveyed by the first co-author (Table S2). Merningar Noongar names are from Knapp et al. (2024), and are given first in the text as a mark of respect and to recognise their historical priority. Orange dashed line demarcates the division between the OCBIL (old, climatically-buffered, infertile landscape) granite inselberg of Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner to the east and the western YODFEL (young, often-disturbed, fertile landscape) lowlands. Base map provided by CSIRO. Inset shows floristic provinces and districts within the Southwest Australian Floristic Region (from Gioia and Hopper (2017)), and additional place names used in the text.

As a consequence, the conservation challenge has risen considerably, with spectacular growth in lists of threatened and poorly known species of concern (Hopper et al. 1990; Coates and Atkins 2001). Additionally, surprising patterns in ecological, evolutionary, and detailed conservation biology studies have called for the development of novel theory and new scientific approaches to better understand the complex evolution and phytogeography of such a species-rich flora on the relatively subdued landscapes of the SWAFR (Hopper 2009; Lambers et al. 2011; Hopper et al. 2021a).

In many ways, the historical exploration of this impressive flora continues at pace. Spectacular systematic discoveries and output in the 1800s by early pioneers such as Robert Brown, Ferdinand von Mueller, and George Bentham continue to be matched by significant contributions today, albeit at a reduced rate of descriptions of new species by modern workers (Hopper 2003, 2004; Wege et al. 2015). Several contemporary taxonomists nevertheless have described more than 100 new species over their careers (reviewed in Hopper (2004)).

Ongoing discovery and inventory of plant life in a global biodiversity hotspot such as the SWAFR thus remains unfinished (Hopper and Gioia 2004; Gioia and Hopper 2017). Even for the well-studied bushland of Kings Park, a large inner-city park in the heart of the Perth, Western Australia’s capital city, with three books written about its plant life, the documented number of species rose from 408 in 1988 (Bennett and Dundas 1988) to 593 some 28 years later (Barrett and Tay 2016). Such a dramatic change, due to better inventory and new introduced weeds, has rarely been documented given the relative paucity of long-term botanical studies completed on specific areas within the SWAFR.

Such intensive place-based work remains important for the continuing conservation and use of native plants. Plants without names are consigned to a fate of benign or wilful neglect. A precise inventory of organisms on reserves is the first step in ensuring informed stewardship of the biota. Once species are named and identified on reserves, relative abundances can be determined, vulnerabilities to extinction estimated, and corrective actions undertaken to minimise extinction. A comprehensive inventory also enables celebration of the rich diversity of life on Earth, and ongoing discovery of biological attributes, interactions, and processes.

There are constraints on the number of botanically informed people able to discriminate species and record their occurrence in the wild in places with low human populations such as in the SWAFR (Corlett 2016). Consequently, choices have to be made about which areas of native vegetation have priority for biological survey, and which organisms are best suited for the efficient testing of hypotheses under consideration. Vascular plants are a natural first choice because of the now advanced state of their classification (The Angiosperm Phylogeny Group 2016) and the relative ease of survey of the majority of species in most areas. Moreover, rooted plants do not move, enabling repeat visits for verification of an individual’s identity by independent workers if specimen locations are recorded precisely. As will be evident in this study, every plant name is a working hypothesis, and can be falsified if a relocatable plant has attributes that do not match the type specimen and/or protologue in the original description.

Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve (Fig. 1) is of considerable historic, as well as present-day botanical, interest. Because of the fine anchorages nearby in King George Sound and Princess Royal Harbour, as well as its proximity to Albany, the oldest European settlement in Western Australia, Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve has long been accessible to scientists. Consequently, several botanical collections have been made since the time of the first exploration by Europeans (Chatfield and Saunders 2024). By the mid-1980s, the number of vascular plants on the Reserve was estimated to be 617 by A. J. M. Hopkins (cited as a personal communication by Smith (1987)).

Created in 1967 primarily to conserve the then recently rediscovered noisy scrub-bird (Atrichornis clamosus) (Danks 1997), Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve occupies 4774.7 ha on the south coast of Western Australia, east of Albany. Physiographically, it is dominated by the granite inselberg Maardjitup Gurlin (Noongar name for Mt Gardner), attaining 408 m in height at the end of the eastern peninsula (Fig. 1). An isthmus to the west gives way to lowlands of dunes and wetlands, with a low lateritic plateau in the north west (Smith 1987). Much of the western south coast is flanked by limestone rocks and platform reefs (Sinker Reef). Four islands are included in the Reserve (Fig. 1), which receives approximately 800 mm of rainfall each year.

Studies on the noisy scrub-bird have given cursory structural accounts of the preferred habitat of the scrub-birds, ranking from best to least used as low eucalypt forest, Agonis (now Taxandria) forest, tall thicket, low thicket, and heath. (Smith 1996). Ten years later, the Noisy Scrub-bird Recovery Plan (Danks et al. 1996) proposed that preferred habitat was scrub/thicket, whereas low forest and then heath were progressively less preferred by singing males.

Nesting material is better described from a floristic viewpoint:

The nest is globular, approximately 18 cm in diameter, with a small side entrance. It is usually sited about 20 cm above the ground in a dense clump of sedge or, less commonly, in a dense shrub or pile of debris. The long leaves of pliable sedges such as Anarthria scabra and Lepidosperma spp. are used for the construction of the core with the leaves of Agonis flexuosa, Eucalyptus spp. and Dryandra (now Banksia) formosa, twigs and strips of paperbark often being used for the outer layers of the nest. The lower half of the nest interior is lined with a papier mâché-like substance made from decayed wood. (Danks et al. 1996, p. 19)

The benefits for caring for other animals and plants, some threatened, was also recognised at this earlier time by ornithologists focused on conserving noisy scrub-birds. More detail on plants in Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve arose out of a study comparing island floras with those of adjacent mainland sites (Abbott 1980), and in a study of honey possum (Tarsipes rostratus) distribution and food plants on the Reserve (Hopper 1981). Similarly, the rediscovery of Gilbert’s potoroo (Potorous gilbertii) in the Reserve in 1994 led to the generation of a short species list from the potoroo’s preferred habitat of heath and scrub between two gullies on Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner (Sinclair et al. 1996).

Phytogeographically, Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve sits on the boundary long recognised between the high rainfall forested regions of the southern SWAFR and the adjacent woodlands and kwongkan (our preferred spelling following Hopper 2014) shrublands to the east and north-east (Beard 1980, 1981; Gioia and Hopper 2017; Knapp et al. 2024). Detailed studies of the flora of the Reserve are likely to reflect this mixture or suggest changes in present boundaries recognised. Because the Reserve includes a coastal promontory terminated by a granitic inselberg (Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner) that experiences a cool, wet, maritime climate, we hypothesise that the flora is likely to be richer in species from higher rainfall country to the west rather than in taxa found in the semiarid east and north east.

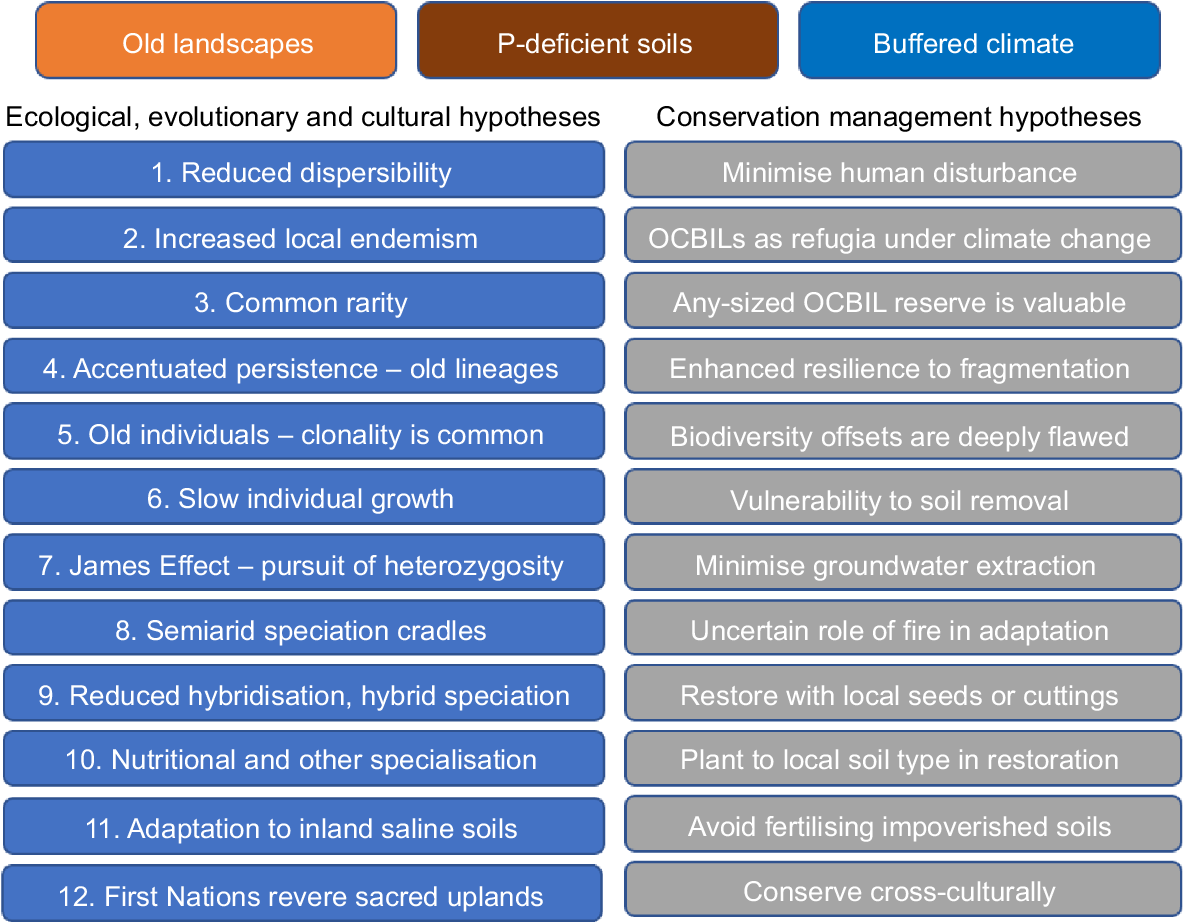

Here, apart from testing key phytogeographic concepts regarding the transition from relatively high rainfall forests to semiarid woodlands and kwongkan, we also aimed to test OCBIL hypotheses (Hopper 2009, 2018, 2023; Hopper et al. 2016, 2021a; Silveira et al. 2021). OCBILs (an abbreviation for old, climatically-buffered, infertile landscapes) are identified by a combination of three attributes: old, persistent upland landscapes due to very slow denudation rates over millions of years, subdued disturbance regimes, most typically climatic buffering due to persistent proximity to oceans for 10s of millions of years; and geological quiescence and the absence of recent major events, such as glaciation, marine inundation, vulcanism, dust storms, and major bioturbation affecting soil rejuvenation. OCBILS are also infertile, especially with soils low in phosphorus, due to prolonged weathering over millions of years (Lambers et al. 2011).

OCBIL landscapes are especially common in the SWAFR, but they occur in at least half of the world’s Global Biodiversity Hotspots (Myers et al. 2000; Mittermeier et al. 2011), especially those of the Southern Hemisphere where 18 of the 22 hotspots identified with OCBILs occur (Hopper et al. 2016). Typically, OCBILs in the SWAFR constitute subdued uplands, either as granite outcrops and inselbergs, lateritic mesas, quartzitic low mountains, or elevated sandplains. The special attributes of OCBILs call for a reconsideration of major hypotheses in conservation biology and evolutionary biology (Hopper 2009). This is because most practitioners in these disciplines live in the Northern Hemisphere and work on recent postglacial landscapes, which are relatively young, often-disturbed and fertile (YODFELs; Hopper 2009). Much of this literature accordingly is focused on natural selection operating on YODFELs. New thinking and hypothesis testing are needed for the dramatically different communities and ecosystems found on OCBILs.

The latest account of OCBIL theory (Hopper 2023) lists 12 biocultural hypotheses and 12 conservation management hypotheses, each of which can be falsified through rigorous testing (Fig. 2). Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve can be divided essentially into the classic OCBIL granite inselberg of Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner terminating on the peninsula, and the YODFEL lowlands of dunes and wetlands to the west (Fig. 1). We predict that the granite inselberg plant communities deserve special focus because they are (1) likely to be richest in local endemics and threatened plants, (2) may have more persistent old lineages, and (3) may display more reduced rates of natural hybridisation than the adjacent younger more fertile dunes, limestones, and lakes of the western lowlands.

The 12 predictive ecological, evolutionary, and cultural hypotheses and 12 conservation management hypotheses, which combined provide a testable foundation for OCBIL theory (Hopper 2023). For detailed elaboration see Hopper et al. (2021a). P, phosphorus.

Minimising disturbance, particularly applying fire, has been a guiding management principle on the Reserve to help conserve threatened birds and mammals. This land management approach was effective but for small, lightning-initiated burns atop the eastern granite inselberg when in November 2015 a large fire consumed more than 90% of the OCBIL vegetation. Although difficult to control, the large fire presented an opportunity to examine the vegetation’s fire responses (i.e. resprouting v/s obligate seeding; Bell 2001; Lawes and Clarke 2011). The objective was to search for early postfire plant opportunists and to consider phenological data for future planning and possible restricted use of fire. Such opportunities are of value given the continuing uncertainty of prescribed burning as a conservation strategy (Bradshaw et al. 2018) and the need for rigorous data from a range of fire regimes to test competing hypotheses.

Consequently, a special focus on documenting the granite outcrop vascular plant communities in Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve was undertaken over the past five decades as opportunity allowed. There has been a 40-year hiatus in the preparation of this paper, between work conducted by the last four co-authors and that recently completed by the first co-author. We were able to test the hypothesis that the floristic inventory of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve has materially increased over this 40-year period. We also share advances on the floristics, phenology, phytogeography, fire responses, and conservation of this inspiring landscape.

In summary, we tested hypotheses that:

As elsewhere in the SWAFR, floristic inventory of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve has significantly increased the flora list over the past 40 years;

Threatened plant species and short-range endemics (Harvey 2002) are concentrated on the granite OCBILs of Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner;

The Reserve’s coastal position means that the flora is richer in species from wetter country to the west than from semiarid country to the east and north-east;

The phytogeographic boundary separating the Bibbulmun Botanic Province and the Southeast Coastal Botanic Province (Gioia and Hopper 2017) is best placed through Boulder Hill and Yeelbarup (Noongar name for Mt Manypeaks)/north-eastwards of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve rather than within the Reserve;

Species representing older lineages are concentrated on the granite upland OCBILs of Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner;

Flora on these granite outcrop OCBILs display reduced rates of natural hybridisation compared with that in the adjacent flora of younger more fertile dunes and wetlands; and

Greater vulnerability of plants to frequent fires is evident on the elevated granite outcrop OCBILs than in the adjacent flora of younger, more fertile dunes and wetlands.

History of European botanical collections

We do not address Noongar knowledge of the flora of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve because a start has been made in an accompanying paper (Knapp et al. 2024). The natural resources of the south-western part of the Australian continent attracted the interest of sea-borne European explorers from the 1600s onwards (Chatfield and Saunders 2024). These men primarily sought safe anchorages, freshwater, and food. Few could afford the luxury of detailed investigations of the coastline but those who did invariably made plant collections. The first such detailed survey of the Two Peoples Bay area was made between 20 and 27 February 1803 by Midshipman Ransonnet under orders from Captain Baudin (in the Geographe). Ransonnet went by long boat from King George Sound into Two Peoples Bay, and climbed Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner, explored the inlets to the east, and by boat travelled up a small creek into the waterbody now called Tyiurrtmiirity/Gardner Lake. He ‘…could make out another lake [Kaiupgidjukgidj/Moates Lagoon] which joined this one (and) wanted to follow it but it was impossible to combat the obstacle made by the thick shrubs settled on the sand dunes’. (Ransonnet 1803).

During the same few days another party, including the geographer Faure, was exploring the coast from Oyster Harbour to the west of Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner (Baudin 1974). It is probable that they both made collections from the Reserve area, as all Baudin’s expeditions were instructed to collect plants when on land. However, specimens collected from Two Peoples Bay may be few in number as King George Sound was extensively surveyed during the time of Baudin’s visit and duplicates may not have been kept.

The entire collection made on the 1803 voyage of the Geographe from Sydney to the Bonaparte Archipelago, via the South Australian gulfs, Ceduna, King George Sound, Geographe Bay, and Shark Bay (Marchant 1982), is lodged at either the Museum National d’Histoire Naturelle at the Jardin de Plante or the Museum d’Histoire Naturelle, Le Havre. It would appear that, after the Geographe returned to France, the plants were sorted and classified according to the pre-Linnaean System that was then in use. Subsequently they received little attention (Hopper 2004; L. R. Marchant, pers. comm., 1982).

More recorded collections on the Reserve did not appear until a quarter of a century after the Baudin expedition sailed on from King George Sound. In June 1831 the colonial surgeon at Albany, Alexander Collie, accompanied a band of sealers on a visit to Coffin Island. He then crossed to the mainland and climbed to the summit of Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner where he made some general observations on the soils and vegetation across much of the Reserve. It is not known whether Collie collected any plants during this visit, but he did add some: he planted almond seeds in a patch of brown loam near the top of Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner. He had previously planted almond, castor bean and other species, and one of the sealers planted flower seeds on Coffin Island (Collie 1833). No evidence of any of these plantings has been seen during the thorough recent surveys.

Spending the first 2 weeks of January 1834 in King George Sound and surrounds, perhaps as far east as Two Peoples Bay, the Austrian botanist Baron Karl von Huegel was botanically enthusiastic and astute:

Who has ever come to King George Sound … without rejoicing in the Banksia coccinea, Hovea celsiana [probably elliptica] and Cephalotus follicularis. But it is not only these more spectacular plants that make this region exceedingly interesting from a botanical viewpoint … a host of other beautiful and remarkable but less striking species are indigenous here .… The vegetation round Albany and in the whole area which I explored, within a diameter of about 40 miles at most, is very diverse and interesting. Due to the different type of rock, granite and closely related rock types, the vegetation is completely different from that round Swan River. (Clark 1994: 78, 94–95)

The German botanist, Johann August Ludwig Priess, made numerous collections as he travelled on foot from Torbay to Cape Riche late in 1840. Although he is thought to have travelled north of the Reserve area (N.G. Marchant pers. comm. 1981) his collections included six specimens labelled Two Peoples Bay 23, 24 November 1840 (Lehmann and Preiss 1844–47). The species collected were identified as Jacksonia spinosa, Isopogon longifolius, Leucopogon corynocarpus, Pimelia sylvestris, Microcorys selaginiodes (?), and Scaevola revoluta. Only the first three species have been collected on the Reserve subsequently (Table S1). S. revoluta has only been collected in the north of Western Australia and no record of the species of Microcorys can be found. However, Microcorys barbata is reasonably common on the Reserve.

In 1860 Kew Gardens’ Deputy Director Joseph Dalton Hooker published the first thorough review of the phytogeography of the Australian continent. He, too, followed up on Huegel’s insight concerning differences between the Albany and Perth floras. Hooker noted the sometimes exceptional short-range endemism and was perplexed by the ‘rapid succession of forms … though separated by only 200 miles of tolerably level land’. This latter enigma was ultimately related to the persistence of old landscapes since the Permian, enabling prolonged evolution and microspeciation (Hopper 2009, 2023, see below):

The local character of the south-western Australian plants is another singular feature that must not be overlooked … So singularly circumscribed are its species in area, that many are found in one spot alone, and of some Natural Orders, the species of the Swan River differ very much from those of King George’s Sound .… there are far more King George’s Sound species absent from the Swan River, though separated by only 200 miles of tolerably level land, than there are Tasmanian plants absent from Victoria, which are as many miles apart, and separated by an oceanic strait .… I am quite at a loss to offer any plausible reason for this rapid succession of forms in area. (Hooker 1860: liv).

Soon to follow was Kew botanist George Bentham’s (1863–1878) monumental Flora Australiensis in seven volumes, in which many taxa occurring in Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve were treated, and some described for the first time (author citations in Table S1). Thereafter an ebb and flow of taxonomic interest in the SWAFR flora is evident, but no increase in Hooker’s (1860) estimate of 3600 species for the region occurred for more than 100 years (Marchant 1973). The mistaken view prevailed that a large majority of taxa had been described in the 1800s, entrenching perceptions of a well-documented ‘Cinderella flora’ until the past half century (Hopper 2003, 2004).

Following the re-gazetting of the Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve in June 1967, the public interest in the area, especially in the noisy scrub-bird, provided impetus for detailed studies of the biota. Early studies focused on the rare birds found on the Reserve and plant collections were made mainly to identify species important in the habitats of these birds. This work was carried out by the staff from the CSIRO Division of Wildlife Research. Later research, dealing more specifically with the flora and vegetation of the Reserve, was conducted by the staff from CSIRO, the Department of Fisheries and Wildlife (now Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions [DBCA]), The University of Western Australia, and various herbaria (see below).

Materials and methods

Flora list and phenology

Florabase (Western Australian Herbarium 1998–2024) has been integral to compiling the final flora list, enabling checks on correct names, authorship, collectors, phenology, geographical distribution, identifications, and individual specimen labels. Currently with 821,870 specimens of Western Australian plants and fungi databased in Florabase, the first co-author worked comprehensively through the 2547 specimens that gave the location ‘Two Peoples Bay’ (n = 2428); or ‘Two People Bay’ (n = 119). Other searches based on place names enabled comparison of collecting activity at Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve with that conducted nearby.

In the compilation of the flora list, plant collections or lists of plant collections made by the following people at locations shown in Hopkins et al. (2024a) and in Fig. 1 and Table S1 herein have been examined mainly at the Western Australian Herbarium (PERTH): L. A. Moore and G. T. Smith (1974–1982, CSIRO plant study transects, Locations 1, 2, 3 and 6); M. C. Ellis, L. A. Moore, F. N. Robinson, and G. T. Smith (1969–1982, noisy scrub-bird study areas, locations 4 and 5); R. E. S. Sokolowski (1976, Location 7); I. Abbott (1980, Locations 7, 8 and 9); N. Smith and Kolichis (1980, Coffin Island); E. M. Gude (1990, wetlands in Locations 2, 3, 4, and 13). Collections in the more general Regions 10–12 were made by A. J. M. Hopkins (1975–1987), L. A. Moore and G. T. Smith (1974–1982), A. A. Burbidge (1970–1971), R. E. S. Sokolowski (1971–1978), G. Folley (1978–1982), and S. D. Hopper (1973–2021). Other collections for which no specific locality data were given have been incorporated without annotation. These collections result from visits to the Reserve by N. T. Burbidge from the Herbarium Australiense (1973), J. Powell from the National Herbarium in Sydney (1980), and A. S. George (1964, 1967 and 1971), N. G. Marchant (1971) and S. Paust (1971) from the Western Australian Herbarium. Many other collectors have been active over the past four decades, too numerous to list (but see Florabase at Western Australian Herbarium 1998–2024). Of note have been general collections of G. J. Keighery (1972–2019), the Miialyiin/Angove Lake and other collections of E. M. Sandiford, D. A. Rathbone, and E. J. Hickman (2008, 2013, 2017), the sedge and other collections of K. L. Wilson, R. L. Barrett, and S. Barrett (2008, 2013), general collections of E. J. Croxford (1980–2009) and J. A. Cochrane (1994–2017) and granite collections by M. Dilly (past 5 years).

To test the comprehensiveness of the herbarium record, two approaches were adopted. First, noted orchidologist Andrew Brown compiled a full list of orchids on the Reserve, that he has seen and recorded in field notebooks over several decades. Orchids are perhaps the best studied of all families in the field, with abundant published material to assist identification (e.g. see Brown 2022 for the latest books). Brown is one of the most capable field students of Western Australian orchids, so any additions to the herbarium list for Orchidaceae are likely to be in his notebooks. In addition, Garry Brockman, an emerging taxonomist of Western Australian orchids, also provided a list of orchids seen on the Reserve over several decades, from his field notebooks. Second, special collection techniques were used by S. D. Hopper and colleagues to document granite flora, including the random stratified walk method, compilation of fieldbook herbaria, as well as examination of pertinent literature. These techniques are detailed elsewhere (Hopper et al. 2021b).

The large number of collectors and collections of Two Peoples Bay material has posed taxonomic problems in the compilation of a flora for the Reserve. Many of the identifications are not supported by voucher specimens and some specimens are in distant herbaria. However, there is now a substantial, though incomplete, collection located at the Western Australian Herbarium (PERTH). Field herbaria are also located at PERTH and at the Two Peoples Bay Research Station, as well as in the comprehensive field notebooks of S. D. Hopper. As far as possible, specimens incorporated in these herbaria are consistently named in Table S1 by the first and second co-authors to match those used in Florabase as of March 2024.

Plants recorded on granite OCBILs are highlighted on the master list (Table S1). In Table S2, these same species are categorised according to life history (terrestrial/aquatic; perennial/annual; herbaceous; graminoid/geophyte; ferns–fern allies; vine) and fire response (resprouter/seeder) based on the literature and herbarium records (see Hopper et al. 2021b) and actual fire responses recorded on the Reserve the first year following the 2015 wildfire. The occurrence of species in special habitats on the Reserve’s granite outcrops was noted as on moss mats, herbfields, dwarf shrubs and Borya, larger shrubs and thickets/low forest flanking the granite (Nikulinsky and Hopper 2008; Hopper et al. 2021b).

In the 1990s, Table S1 was organised systematically by family based on an outdated morphological classification of vascular plants. However, the significant recent advances in molecular phylogenetics have enabled the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group to rearrange families according to their genetic relationships through four published iterations (The Angiosperm Phylogeny Group 2016). The Western Australian Herbarium has reorganised its collection predominantly in line with Angiosperm Phylogeny Group IV. However, certain families not recognised in Angiosperm Phylogeny Group IV such as Centrolepidaceae are recognised at PERTH. This rendered difficult the replication of family arrangements between that used in the 1990s and that in Florabase today. Consequently, Table S1 aims to compromise by arranging families alphabetically within major phylogenetic groups of ferns and fern allies, gymnosperms, early branching dicots, monocots and core eudicots. This system recognises all families used by the Western Australian Herbarium in Florabase. In Table S2, genera on granite outcrops are arranged alphabetically for ease of use, with aliens marked by an asterisk (*) and listed first ahead of native vascular plants.

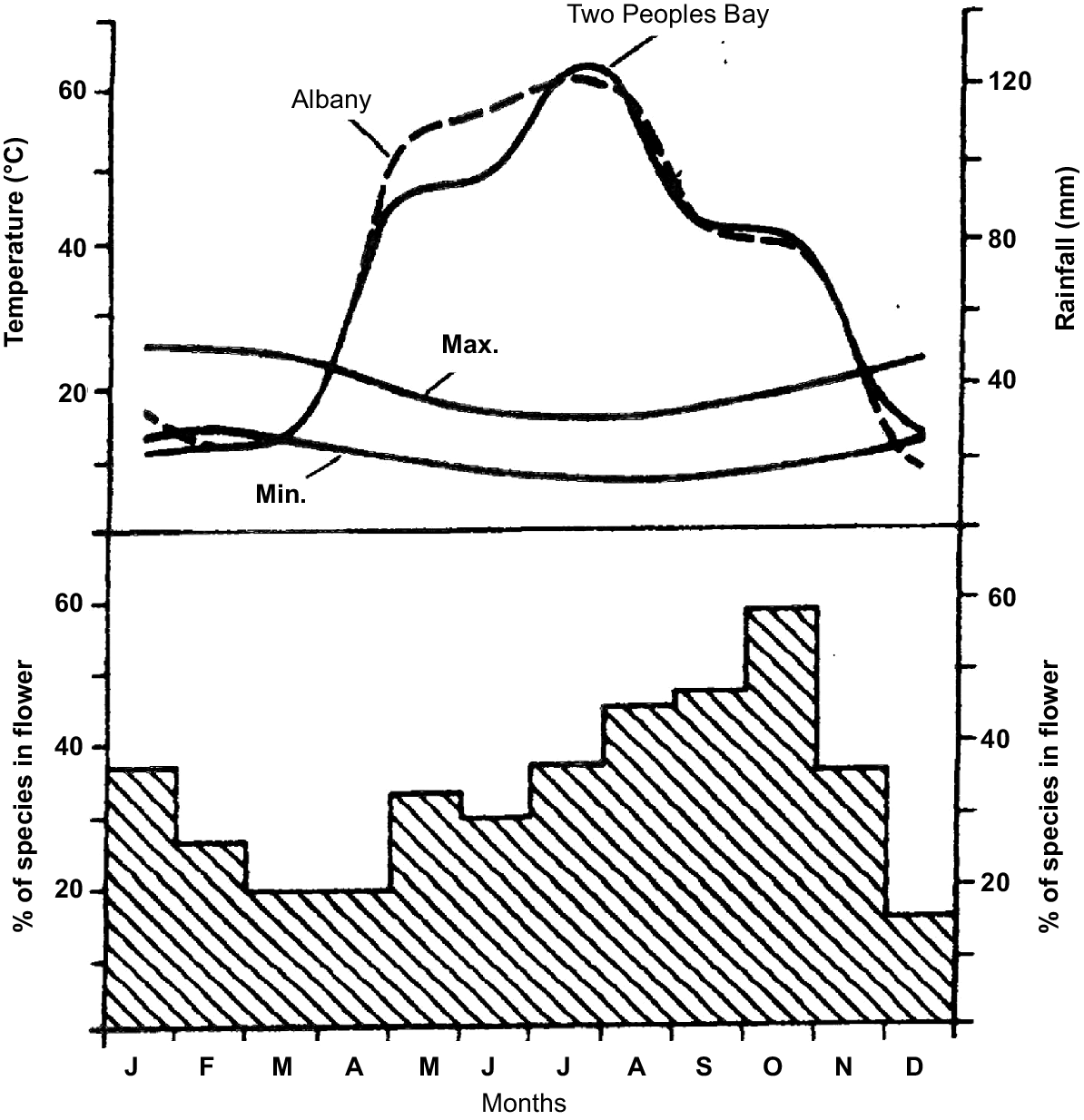

Phenological data were obtained for 425 taxa (Table S1). The observations were not systematic so we have assumed continuous flowering through any month where no traverse was made but for which both preceding and subsequent months have positive records. Observations of flowering and fruiting were recorded for four plant transects (Table S1, Locations 1, 2, 3 and 6) over the period 1975–1982 (Fig. 3). Transects were visited at the following times: 1975; May (Locations 1 and 3), June (2), July (1, 2, 3 and 6), September (1, 2, 3 and 6) and October (1, 2, 3 and 6), 1976; January (1), February (1 and 2), March (1 and 6), April (1), May (1, 2 and 6), June (6), 1982; January (1, 2, 3 and 6).

Threatened species and short-range endemics are concentrated on OCBILs

Conservation status was determined by comparing the flora list (Table S1) against that published online as DBCA’s threatened and priority flora list for 2023 (https://www.dbca.wa.gov.au/wildlife-and-ecosystems/plants/list-threatened-and-priority-flora, accessed December 2023).

Short-range endemism was determined using Florabase maps for taxon names in Table S1. Harvey’s (2002) definition of short-range endemic taxa, i.e. species with a geographic range of less than 10,000 km2, was used. The conservation codes used by DBCA and its predecessors for threatened and priority flora were developed by Hopper et al. (1990). Although the terms critically endangered, endangered, vulnerable, and presumed extinct now have wide international currency, the four priority codes for indeterminate poorly known conservation taxa used herein are defined in the endnotes for Table S1. A simple numerical comparison was undertaken of the number of threatened species and short-range endemics on the Reserve between those on the YODFEL lowlands and those on the OCBIL inselberg (Fig. 1).

The Reserve’s flora is richer in species from wetter country to the west than from semiarid country to the east and north-east

Geographic ranges of taxa listed in Table S1 were subjectively categorised by the first coauthor in relation to Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve into mostly western, mostly eastern or centred (neither western nor eastern dominated) according to current Florabase maps. Only a small number of taxa were equivocal according to this simple classification. In addition, Florabase maps were checked carefully to identify which species reached their most eastern or western geographical limits on the Reserve. In the context of the above hypothesis, it was predicted that western species reaching their most eastern point in the Reserve would be more common than eastern species reaching their most western limit.

Floristic and vegetation-based phytogeographic boundaries

In the most up to date floristic analysis of the SWAFR, Gioia and Hopper (2017) placed the boundary between the Bibbulmun and Southeast Coastal Botanical Provinces on Yilbarup/Mt Manypeaks/Waychinocup National Park, commencing approximately 10 km north-east of Miialyiin/Angove Lake. This boundary was evaluated by examining Florabase maps of taxa listed in Table S1 as well as specimens collected by Grant Wardell-Johnson (Curtin University), Tony Annels (DBCA), Libby Sandiford (private botanical consultant), and other specimens from the south-west end of Boulder Hill overlooking Two Peoples Bay itself. If the boundary needed shifting south-west from Boulder Hill to Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve, the strongest disjunctions in the ranges of taxa should be evident in the latter Reserve. In contrast, the present boundary should remain if there are many disjunctions of taxa at their boundary limits on Boulder Hill.

Significant subdivision of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve based on vegetation mapping was suggested by Beard (1979, 1981). He placed the forested area in the north-west of the Reserve within the Menzies subdistrict of the Darling Botanical District, whereas the lakes and coastal shrublands on and around Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner were included within the Bremer Vegetation System of the Eyre Botanical District dominated by shrublands and mallee. We sought to examine this proposal by obtaining detailed information on the individual plant height of widespread shrubs, mallees, and trees of banksias and eucalypts on the Reserve. Plant height of trees, mallees, and shrubs is a key attribute in determining vegetation types in the system of Muir (1977), which has been adopted in vegetation mapping for the Reserve (A. J. M. Hopkins, A. A. E. Williams, J. M. Harvey, et al., unpubl. data). For example, low forest or woodland has trees less than 5 m tall; shrubs greater than 2 m tall form thickets or scrub, whereas those below 2 m form heath or low scrub. Consequently, to assist in familiarisation with plant communities and potential phytogeographic boundaries within the Reserve, a map of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve was divided into 500 m2 grids (Fig. 4) using Australian Map Grid Coordinates (Geocentric Datum of Australia 2020). The grid system was then redrawn on 1:25,000 air photos to ensure accurate field location. A 500 m2 grid was chosen because it was small enough to allow for discrimination between major landforms and vegetation types, yet still large enough to enable all grid cells (247 in total) to be inspected at least once within a 3-week sampling period in the summer of 1980/81. Grids were visited using four-wheel drive vehicle, canoe (Kaiupgidjukgidj/Moates Lake, Fig. 1), or on foot. The few grids that were not reached were inspected with binoculars from no more than 500 m beyond the problematic grid boundaries.

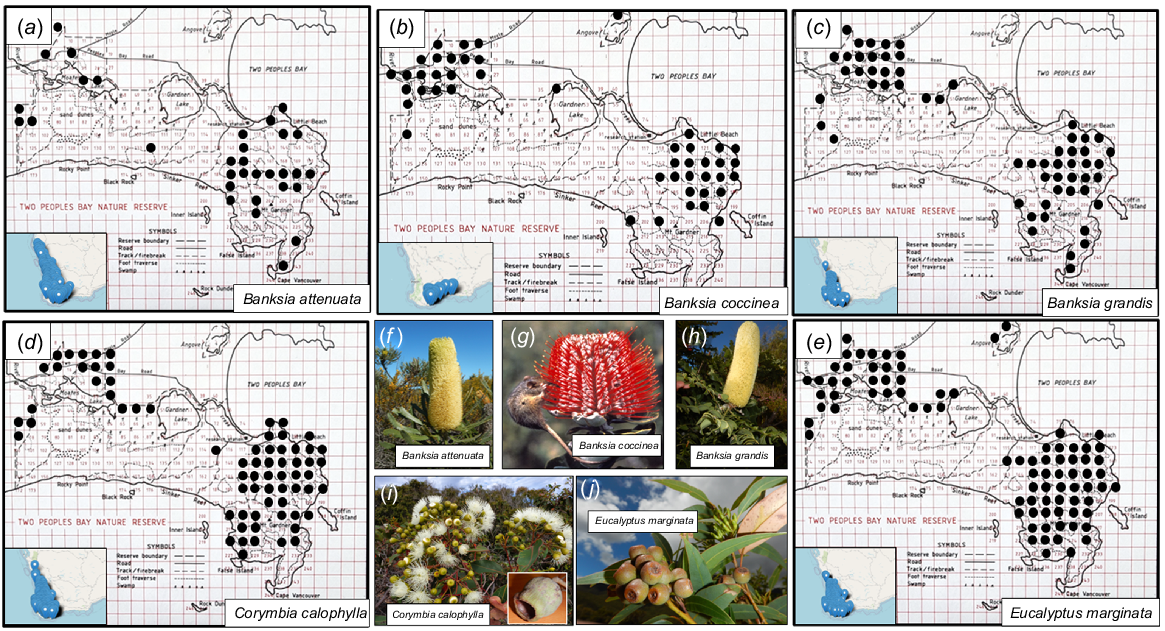

Map of two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve showing 500 m2 grid used to map height of common eucalypts and banksias. Roads, firebreaks, and foot traverses walked are indicated.

A combination of ease of access, visibility through vegetation, and habitat diversity influenced the completeness of the survey of each grid. In general, grids in the rugged eastern Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner inselberg or headland area could be examined only where tracks had been made through patches of dense vegetation for noisy scrub-bird census work. Consequently, only a small proportion of these grids was surveyed. Grids on the isthmus were easy to survey, whereas those in the western part of the Reserve were of variable difficulty.

Notes on vegetation and dominant species were made for each grid, as was average height for eucalypts and banksias. The latter heights were measured with a tape to 3 m or by estimation of two recorders if taller, to ascertain if clear structural changes in long unburnt vegetation occurred as an additional aid in determining phytogeographical boundaries.

Accentuated persistence of old lineages on OCBILs

Relative age of lineages was based on published molecular phylogenetic studies (e.g. Hopper and Gioia 2004; The Angiosperm Phylogeny Group 2016; for Myrtales Berger et al. 2016; Maurin et al. 2021). Early branching clades at the levels of order, families, subfamilies, tribes, and genera were identified from the flora list for the Reserve. In some cases, with well resolved species-level phylogenies, early branching species were similarly recognised (e.g. Rivadavia et al. 2012 for Drosera; Zuntini et al. 2021 for Commelinales). As such, treatments are piecemeal at present across vascular plants. Thus, representative examples were selected for discussion rather than detailed statistical analysis undertaken. With this approach, the occurrences of old lineages were compared between the eastern granite inselberg OCBILs and the western lowland YODFELs on the Reserve (Fig. 1).

Reduced hybridisation/hybrid speciation is seen on OCBILs

Modern plant surveys by the first co-author have had a special focus on detecting hybrids (Hopper 2018; Hopper et al. 2021b). In some cases, DNA sequence studies were conducted affirming hybrid status and the patterns of interbreeding (e.g. Walker et al. 2018; Robins et al. 2021). In other cases, standard morphological, ecological, and reproductive field tests to identify hybrids and backcrosses were applied (e.g. Hopper et al. 1978). The grid-based survey of the entire Reserve in 1980/81, described above, afforded an opportunity to document relative abundances and habitats occupied by eucalypts across the Reserve, and to discover rare hybrids that otherwise may have been overlooked. The 2015 wildfire on Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner greatly improved access on its slopes, enabling further discovery of hybrids on a survey in 2000. The occurrence of hybrids and hybrid swarms was then compared between the eastern granite inselberg OCBILs and the western lowland YODFELs on the Reserve (Fig. 1).

Greater vulnerability to frequent fires is evident on the elevated granite outcrop OCBILs of Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner rather than on lowland YODFELs

Vulnerability was inferred from a basic fire response division between resprouters vs obligate seeders (Bell 2001). Resprouters may regenerate from epicormic buds, or buds held below ground level on lignotubers; or by geophytic bulbs, corms, and rhizomes. Resprouters may also regenerate through seed germination. Obligate seeders can only recover from fire by seed germination, and thus are more vulnerable to short inter-fire intervals. At the community level, the ratio of resprouters vs seeders is a simple measure of this vulnerability. The fire responses of granite outcrop plants in 80-year-old unburnt vegetation on the Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner OCBIL inselberg was recorded systematically in October 2016 following the extensive wildfire of November 2015.The proportion of obligate seeders on the OCBIL was then compared with that for the adjacent YODFEL lowlands (Fig. 1) as reported by A. J. M. Hopkins, G. T. Smith, J. Harvey, et al. (unpubl. data) and with other YODFEL communities across the SWAFR as reported by Burrows et al. (1987) and Bell (2001).

Results

Flora list and phenology

As of 6 January 2024, Florabase records (Western Australian Herbarium (1998–2024) revealed that 2547 specimens at PERTH had been amassed with the location given either as ‘Two Peoples Bay’ or ‘Two People Bay’ (2428 and 119 specimens, respectively). This is the largest herbarium collection for an area in the Albany local government region with the exception of ‘Porongurup’ (2322) + ‘Porongurups’ (769). Other nearby place names centred on conservation reserves had smaller numbers of specimens, e.g. Manypeaks’ (1256), ‘King George Sound’ (1085), ‘Kalgan’ (1003), ‘Torndirrup’ (918), ‘Cheyne Beach’ (893), ‘Torbay’ (457), ‘Mount/Mt Clarence’ (422), ‘Boulder Hill’ (324), ‘Emu Point’ (306), and ‘Bald Island’ (235).

As a consequence of this collecting effort, a total of 622 vascular plant taxa had been recorded as occurring on Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve by the early 1990s. Updating to the present increased this figure to 853 vascular taxa (Table S1). Of this total, 521 taxa (61.1%) belong to 10 major families (Table 1), with Orchidaceae (101), Fabaceae (81 taxa), Proteaceae (65), and Myrtaceae (64) the richest. The most diverse genera are Stylidium (23), Thelymitra (21), Banksia (20), Schoenus (18), Hakea (17), and Caladenia (16). Orchidaceae increased from 72 to 101 taxa with the addition of field notebook records from two expert observers. The field herbaria and notes of the first co-author relating to granite outcrop flora increased the total list by 63 taxa (8%).

| Families/# of taxa | Genera/# of taxa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orchidaceae | 101 | Stylidium | 23 | |

| Fabaceae | 81 | Thelymitra | 21 | |

| Proteaceae | 65 | Banksia | 20 | |

| Myrtaceae | 64 | Schoenus | 18 | |

| Cyperaceae | 59 | Hakea | 17 | |

| Ericaceae | 45 | Caladenia | 16 | |

| Asteraceae | 37 | Acacia | 15 | |

| Poaceae | 29 | Leucopogon | 14 | |

| Stylidiaceae | 27 | Eucalyptus | 13 | |

| Restionaceae | 23 | Drosera | 13 | |

The 54 introduced alien taxa, 6.9% of the total of 853 found on the Reserve, are denoted in Table S1 by asterisks. Name changes (and other reasons) across the 853 affected 311 (36.5%) of the recorded taxa. Of these 311 taxa, 143 (16.8% of the total) are new additions to the Western Australian Herbarium collection since the early 1990s, 108 (12.7%) are name changes for the same taxon due to revisionary studies, and 43 (5.0%) are indeterminate, again due to taxonomic revisions. A few plants were labelled as alien weeds (six, 0.7%) when they are now considered natives, and the opposite applied to three others (0.4%).

Results for phenology are expressed as a proportion of total observed flora (Fig. 3). Seasonal peak flowering on the Reserve occurs in October, followed by a steady decline to a minimum in March and April; thereafter the proportion of species flowering increases again. The low level of records in December results from no transect collections in that month.

Threatened taxa and short-range endemics are concentrated on OCBILs

Table 2 lists 23 species of special conservation interest extracted from priority lists compiled by the Department of Conservation and Land Management in June 1990. This group includes species regarded as short-range endemics. Of the 23, 11 (48%) were found on the OCBILs of Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner, 8 (35%) were found on lowland YODFEL swamps and dune systems, and 4 (17%) were found on both landscapes.

| Declared rare flora (Threatened) | Conservation code | On OCBILs in TPBNR? | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Banksia verticillata | Critically Endangered | Yes | |

| Caladenia granitora | Endangered | Yes | |

| Andersonia pinaster | Vulnerable | No | |

| Priority 1 | |||

| Prasophyllum paulinae D.L.Jones & M.A.Clem. | P1 | No | |

| Austrostipa everettiana A.R.Williams | P1 | No | |

| Priority 2 | |||

| Chamelaucium orarium N.G.Marchant | P2 | Yes | |

| Diuris heberlei D.L.Jones | P2 | No | |

| Gyrostemon thesioides (Hook.f.) A.S.George | P2 | Yes | |

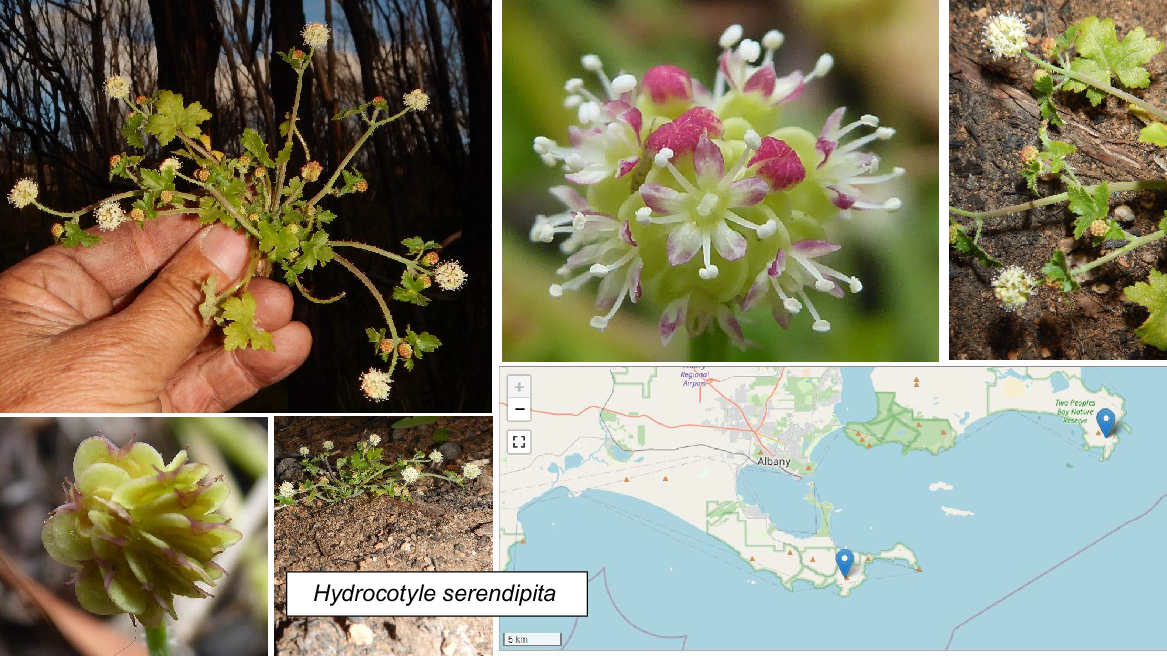

| Hydrocotyle serendipita A.J.Perkins | P2 | Yes | |

| Schoenus sp. Grassy (E. Gude & J. Harvey 250) | P2 | On and off | |

| Thelymitra porphyrosticta F.Muell. | P2 | ||

| Tricostularia sp. Two Peoples Bay (G. Wardell-Johnson GWJ 114) | P2 | Yes | |

| Priority 3 | |||

| Andersonia setifolia Benth. | P3 | On and off | |

| Leucopogon altissimus Hislop | P3 | Yes | |

| Juncus meianthus K.L.Wilson | P3 | Yes | |

| Priority 4 | |||

| Adenanthos x cunninghamii Meisn. | P4 | No | |

| Eucalyptus x missilis Brooker & Hopper | P4 | No | |

| Microtis pulchella R.Br. | P4 | No | |

| Sphenotoma sp. Stirling Range (P.G. Wilson 4235) | P4 | On and off | |

| Stylidium gloeophyllum Wege | P4 | No | |

| Thomasia solanacea (Sims) J.Gay | P4 | Yes | |

| Thysanotus isantherus R.Br. | P4 | Yes | |

| Trithuria australis (Diels) D.D.Sokoloff, Remizowa, T.Macfarlane & Rudall | P4 | Yes | |

See text and Table S1 for description of priority codes.

TPBNR, Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve.

Three species of vascular plants occurring on the Reserve are gazetted as rare flora under Section 23 of the Wildlife Conservation Act 1950–1984: Banksia verticillata, Caladenia granitora, and Andersonia pinaster (Government Gazette 6 October 2023). Melaleuca baxteri was declared as rare on 14 November 1980, but was deleted from the list in a subsequent notice (12 March 1982) because the type specimen was equated with Agonis spathulata and the species at Two Peoples Bay was subsequently described as Melaleuca croxfordiae to honour Albany’s then foremost volunteer plant collector (Craven and Lepschi 1999; Hopper 2004). M. croxfordiae was previously thought to be restricted to Gardner Creek but was found to be common in the gullies around Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner. Today it is well known as a granite endemic west into the southern forests.

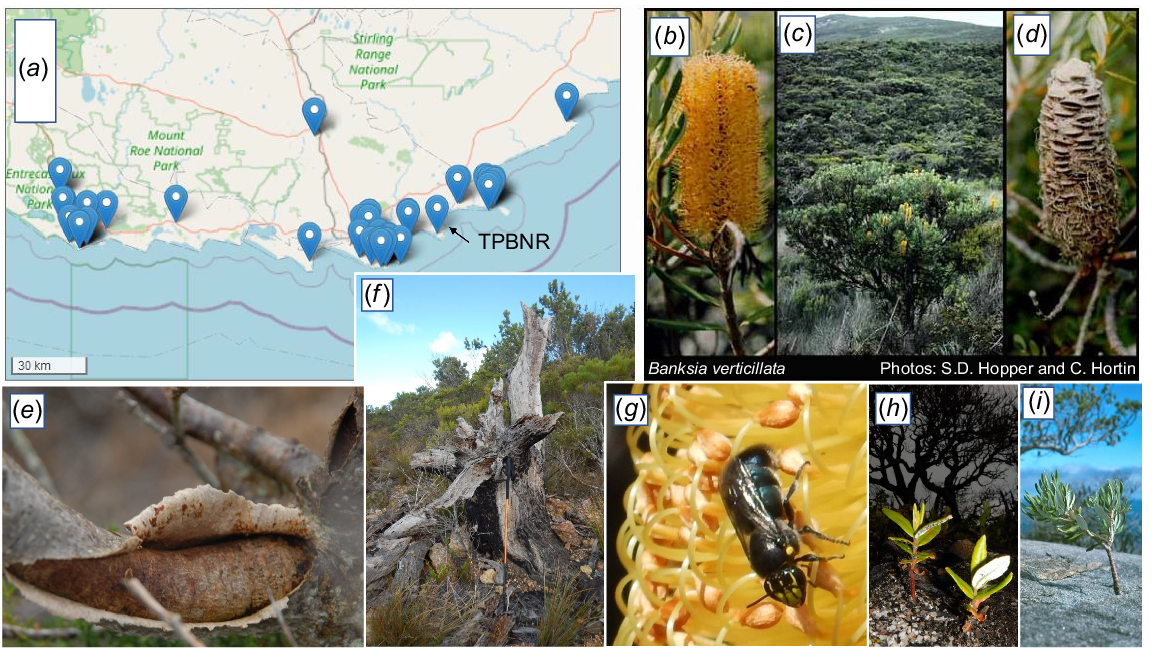

B. verticillata (Fig. 5), now critically endangered, was first located on the Reserve in 1981, evident only as isolated dead trunks with decaying fruits at their bases on the north-eastern slopes of Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner. During recent surveys, however, two specimens of B. verticillata were eventually located. The first was a small tree 2.5 m tall at the edge of a small exposure of granite at the base of Robinson Gully where it forms a steep-sided gully (Rocky Gully) approximately 200 m inland from the sea (Fig. 5c). Associated plants in the dense heath of this site included Eucalyptus megacarpa and Taxandria marginata. The second individual occurred higher up on a ridge. It was sterile and only 1 m tall, presumably because it grew in a dry narrow cleft on a massive sheet of outcropping granite.

The critically endangered Banksia verticillata: (a) Florabase map (the dot inland is of a cultivated plant); (b) inflorescence; (c) 2 m tall plant at the base of Robinsons Gully, Two People Bay Nature Reserve in 1981; (d) fruiting cone; (e) canker wound; (f) old dead tree with walking stick for scale; (g) Banksia bee Hylaeus alcyoneus on inflorescence; (h) two seedlings beneath dead burnt adult a year after fire; (i) 5–10 year-old seedling in crack on granite. All photos by S. D. Hopper except (d) by C. Hortin. Images (e–i) taken in Torndirrup National Park.

The conservation of threatened species is never simple, even where they occur on conservation reserves, as is evident with the most threatened species at Two Peoples Bay, i.e. B. verticillata (Fig. 5; Yates et al. 2021). B. verticillata is progressively declining across its 170 km geographical range (Fig. 5a). Of 36 known populations, all but one occur within 2 km of the coast on granite outcrops and inselbergs surrounded by forest in the west and kwongkan shrublands in the east. Seven populations have already gone extinct, and significant decline has occurred in most surviving populations (Yates et al. 2021). The species recruits predominantly after fire, with first flowering occurring around the tenth year and taking 26 years on average to reach full reproductive maturity.

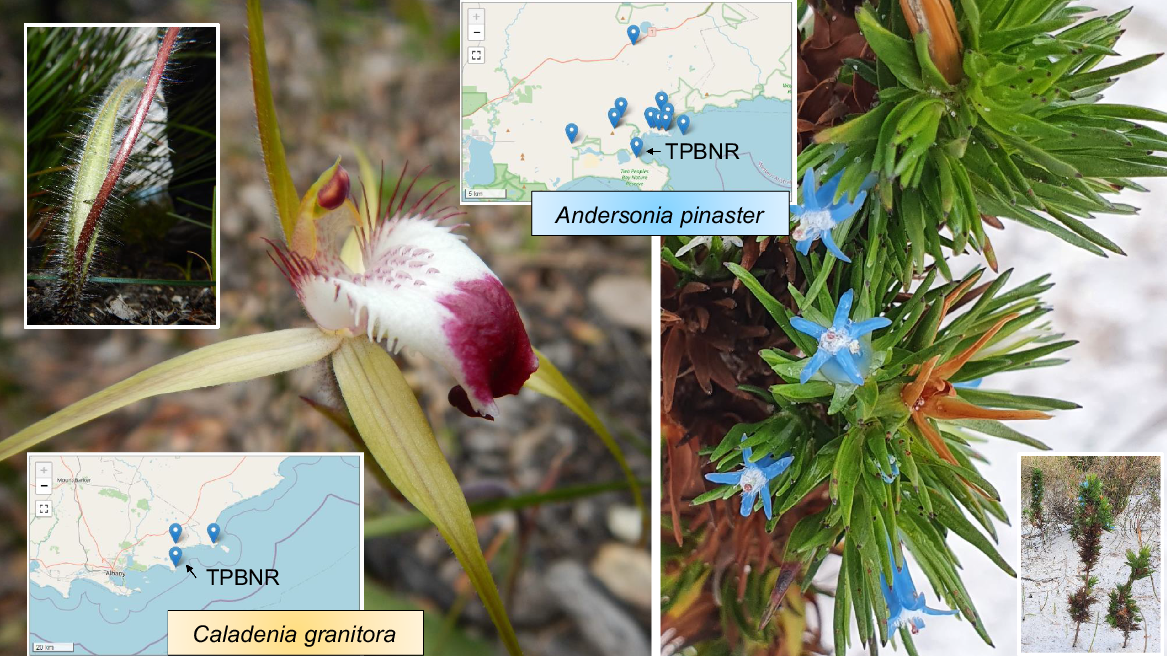

Of the other two threatened species on Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve, C. granitora (Fig. 6a) is known from three closely adjacent series of granite outcrops on Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner (discovered there by the first co-author on 11 December 1988), the western slopes of Yeelbarup/Mt Manypeaks (Holotype SDH 17 October 1987) and hills near Cheyne Beach adjacent to Mermaid Beach and Bald Island (Gary Brockman on 9 October 1999, Florabase record). C. granitora is thus a short-range endemic. Populations comprise widely scattered single individuals or small clusters of a few plants at each location. Estimates across the three populations are no more than 150 individuals in total (Department of Parks and Wildlife 2016). Seed has been collected for long-term storage at Kings Park and Botanic Garden. In one population, 25% of plants produced fruits, so pollinators are still active (Department of Parks and Wildlife 2016). C. granitora likely has a specific thynnine wasp pollinator and fungal symbionts but its life history requires rigorous scientific investigation to ensure its conservation in the wild and ex situ.

The endangered Caladenia granitora and vulnerable Andersonia pinaster. Maps from Florabase. Photos S. D. Hopper. TPBNR, Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve.

A. pinaster (Fig. 6) is susceptible to dieback disease (Phytophthora cinnamomi). It was discovered and first collected by Keighery on 7 August 1986 (Holotype, Florabase) at Herring Bay south-west of Boulder Hill. On the Reserve it is known from the Angove Lake enclave near Tandara Hill. The species is an obligate seeder so care with fire regimes is needed. Much more research on A. pinaster is recommended to ensure its conservation (Lemson 2007).

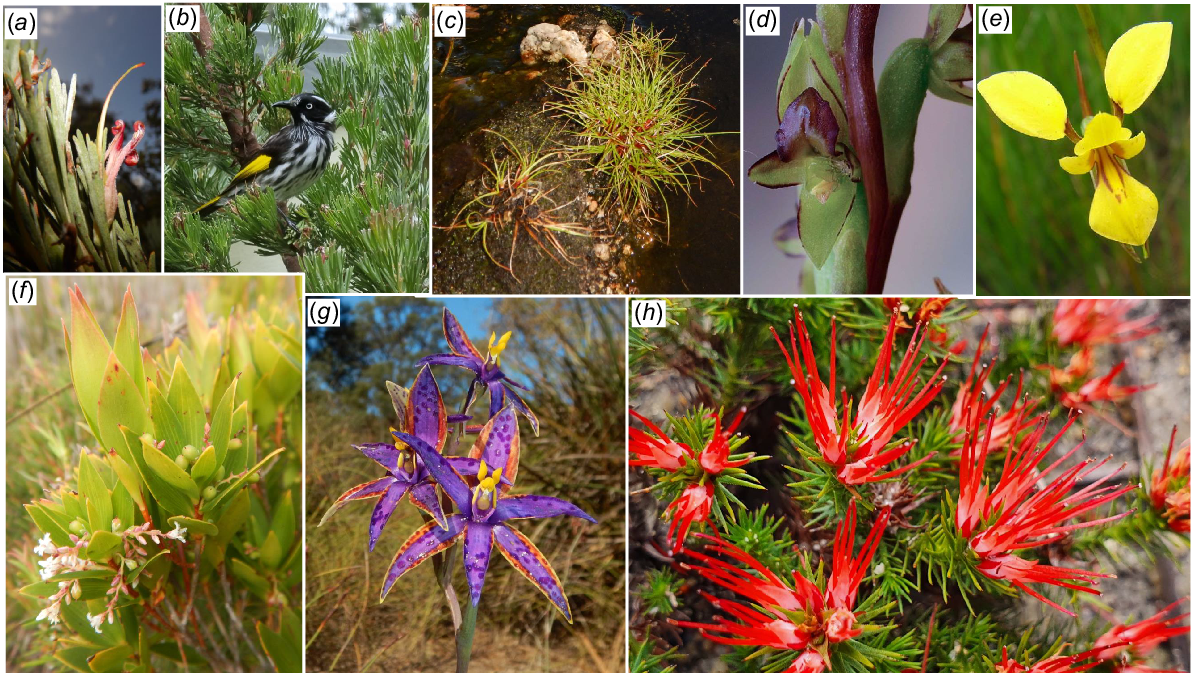

In terms of short-range endemics and challenging conservation issues, species on the priority flora list (Table 2; Figs 7, 8, 9) deserve as much attention as the three officially declared threatened species. Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve’s only true endemic, the P2 shrub Chamelaucium orarium (Fig. 8) is confined to the slopes of Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner. It is reasonably common, but is an obligate seeder so adequate protection from fire is called for. Rarest of all is the remarkable herb Hydrocotyle serendipita (P2), known from two very small populations occupying less than a tenth of a hectare in total; one on the Reserve and the other in Torndirrup National Park south of Albany, where the species was only recently discovered (Fig. 9). On the Reserve it is confined to a single steep gully running south off Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner. In both locations H. serendipita appeared just 1 year following intense wildfires in November 2015, and has since disappeared as adult plants thereafter. Communities in which the species occurred were long unburnt, a pattern strongly indicative of a long-lived seed bank. All 23 taxa (Table 2) deserve careful investigation to ensure the best management for their conservation.

Conservation priority taxa from the Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve area. Photos S. D. Hopper unless otherwise stated: (a), (b) Adenanthos x cunninghamii (P4) and New Holland Honeyeater (Phylidonyris novaehollandiae); (c) Juncus meianthus (P3); (d) Prasophyllum paulinae (P1) photo Garry Brockman; (e) Diuris heberlei (P2) photo Ross and Margaret Fox; (f) Leucopogon altissimus (P3); (g) Thelymitra porphyrosticta (P2); (h) Andersonia setifolia (P3).

The Reserve’s flora is richer in species from wetter country to the west than semiarid country to the east and north-east

Of a total of 800 taxa that could be scored (excluding mainly indeterminate species in Table S1), 437 (54.6%) had a predominantly western distribution in relation to Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve, 276 (34.5%) were centred on the Reserve and found predominantly either side, and only 87 (11%) had a predominantly eastern distribution. Hence phytogeographical affinities of the Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve flora are clearly with the western high rainfall country.

A strong affinity with wetter western country also was evident in that a total of 56 taxa were found to reach their easternmost limit in the Reserve, whereas only six reached their westernmost limit (Table 3).

| Eastern range limit in TPBNR | Kennedia glabrata | |

| Actinotis omnifertilis | Lepidosperma effusum | |

| Adenanthos x cunninghamii | Lepidosperma tetraquetrum | |

| *Allium triquetrum | Leptomeria ellytes | |

| Allocasuarina fraseriana | Meionectes brownii | |

| Anigozanthos preissii | Pimelea drummondii | |

| Anogramma leptophylla | Pithocarpa cordata | |

| Aphelia cyperoides | Podocarpus drouynianus | |

| Banksia seminuda subsp. seminuda | Prasophyllum paulinae | |

| *Bellardia trixago | Pterostylis microphylla | |

| Billardiera fraseri | Scaevola filifolia | |

| Burchardia congesta | Senecio hispidus | |

| Caladenia brownii | Sphaerolobium hygrophilum | |

| Caladenia plicata | Stirlingia latifolia | |

| Commersonia corylifolia | Stylidium glaucum | |

| Conospermum capitatum | Stylidium inundatum | |

| Diuris emarginata | Stylidium violaceum | |

| Diuris heberlei | Taxandria juniperina | |

| Drosera stolonifera | Taxandria parviceps | |

| Empodisma gracillimum | Thelymitra concinna | |

| Gompholobium capitatum | Thelymitra fasciculata | |

| Goodenia eatoniana | Thysanotus isantherus | |

| Grevillea depauperata | Trachymene coerulea | |

| Hakea amplexicaulis | Trymalium ledifolium | |

| Hakea linearis | ||

| Hardenbergia comptoniana | ||

| Hemigenia podalyrina | Western range limit in TPBNR | |

| Hibbertia pulchra var. acutibracta | Eucalyptus acies | |

| Hibbertia grossularifolia | Hibbertia verrucosa | |

| Homalosciadium homalocarpum | Lasiopetalum indutum | |

| Hydrocotyle serendipita | Leptomeria lehmanii | |

| Hypocalymma scarisoum | Schoenus sp. Cape Riche (G.J.K. 9922) | |

| Hypolaena pubescens | Xanthorrhoea platyphylla |

TPBNR, Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve.

Floristic and vegetation-based phytogeographic boundaries

From the results of (3) above, phytogeographical affinities of the Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve flora are clearly with the western high rainfall country. Even though Boulder Hill was separated from the Reserve by just 4 km of the beach of Two Peoples Bay, many species from the east or north or north-west did not extend onto the Reserve. Examples of taxa whose most westerly populations were at Boulder Hill included Tricostularia sp. Two Peoples Bay, Xanthorrhoea platyphylla, Cheilanthes sp., Corymbia ficifolia, Corymbia calophylla x ficifolia, Lambertia uniflora, Lepidosperma sp. Manypeaks large, Morelotia octandra, Tricostularia exsul, and Stylidium rhynchocarpum.

As to be expected, other species known on the Reserve, including Phlebocarya ciliata, Evandra aristata, Petrophile diversifolia, Stylidium plantagineum, S. spathulatum, S. squamotuberoum, and Acacia robiniae, extended north-east only as far as Boulder Hill. Thus, the floristic phytogeographical barrier is permeable and not absolute.

The grid-based survey of plant height of Eucalyptus and Corymbia spp. and Banksia spp. across the Reserve (Fig. 10) demonstrated consistent dwarfing on the granite inselberg of Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner (Table 4). Hence a structural distinction could be made within the Reserve following this phytogeographic boundary between woodlands and kwongkan of the west vs dwarf woodlands, thickets, and montane kwongkan of the eastern granite inselberg (Fig. 1). However, dense low forests and woodlands on steep gullies and at the base of granite sheetrocks on Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner complicated this distinction (A. J. M. Hopkins, A. A. E. Williams, J. M. Harvey, et al., unpubl. data).

Photographs and mapped locations of the five Two peoples Bay Nature Reserve species measured for maximum height per grid cell (see Fig. 4). Distribution maps: (a) Banksia attenuata, (b) B. coccinea, (c) B. grandis, (d) Corymbia calophylla, (e) Eucalyptus marginata. Plant photographs: (f) Banksia attenuata, (g) B. coccinea with honey possum Tarsipes rostratus, (h) B. grandis, (i) Corymbia calophylla, (j) Eucalyptus marginata. Inset maps with blue dots showing whole species range from Florabase. Photos S. D. Hopper.

| Species | Population | Mean ± s.e. Plant height (m) | Range Plant height (m) | No. of 500 m2 grids sampled | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Banksia | |||||

| attenuata | East inselberg | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 1.0–4 | 37 | |

| Rest of reserve | 3.0 ± 03 | 0.5–6 | 36 | ||

| coccinea | East inselberg | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 1–3 | 29 | |

| Rest of reserve | 3.5 ± 0.3 | 1–6 | 22 | ||

| grandis | East inselberg | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 0.5–2.5 | 33 | |

| Rest of reserve | 3.5 ± 0.2 | 1–5 | 29 | ||

| Eucalypts | |||||

| C. calophylla | East inselberg | 3.1 + 0.3 | 1–8 | 46 | |

| Rest of reserve | 10.7 ± 0.8 | 2.5–18 | 20 | ||

| E. marginata | East inselberg | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 1–5 | 50 | |

| Rest of reserve | 7.2 ± 0.5 | 1–13 | 36 | ||

The structural division we documented reflects the phytogeographic description of Beard (1979) in part. Beard placed the forested area in the north-west of the Reserve within the Menzies subdistrict of the Darling Botanical District, whereas the lakes and coastal shrublands on and around Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner were included within the Bremer Vegetation System of the Eyre Botanical District. However, his maps ambiguously placed the entire Reserve in the higher rainfall districts to the west.

Accentuated persistence of old lineages on OCBILs

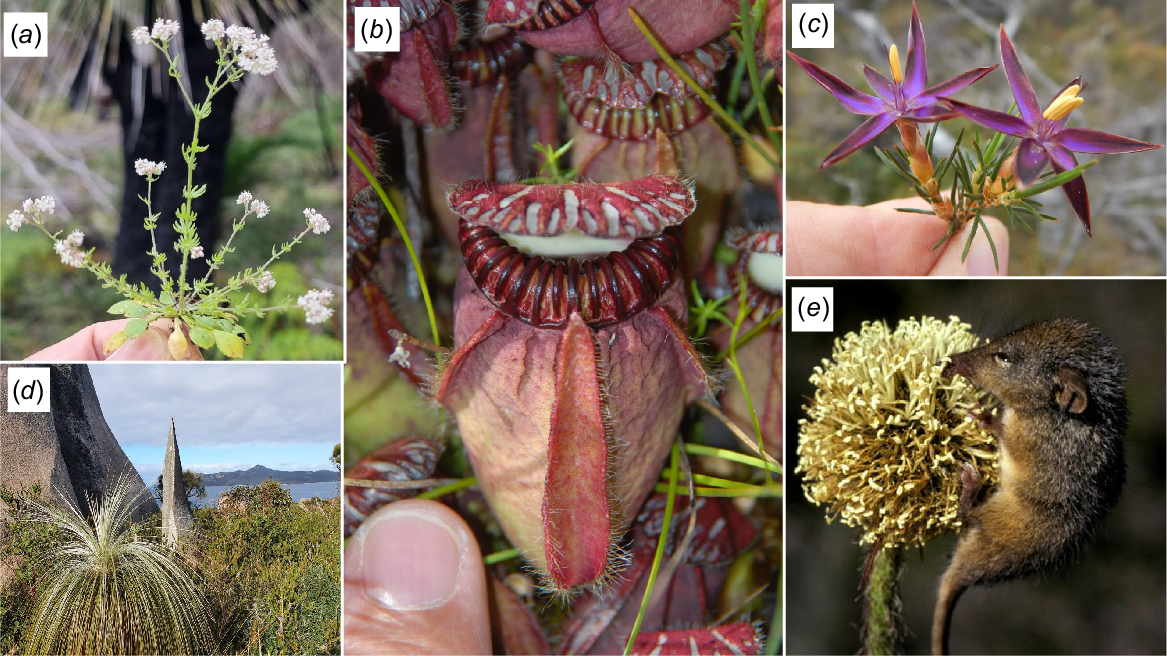

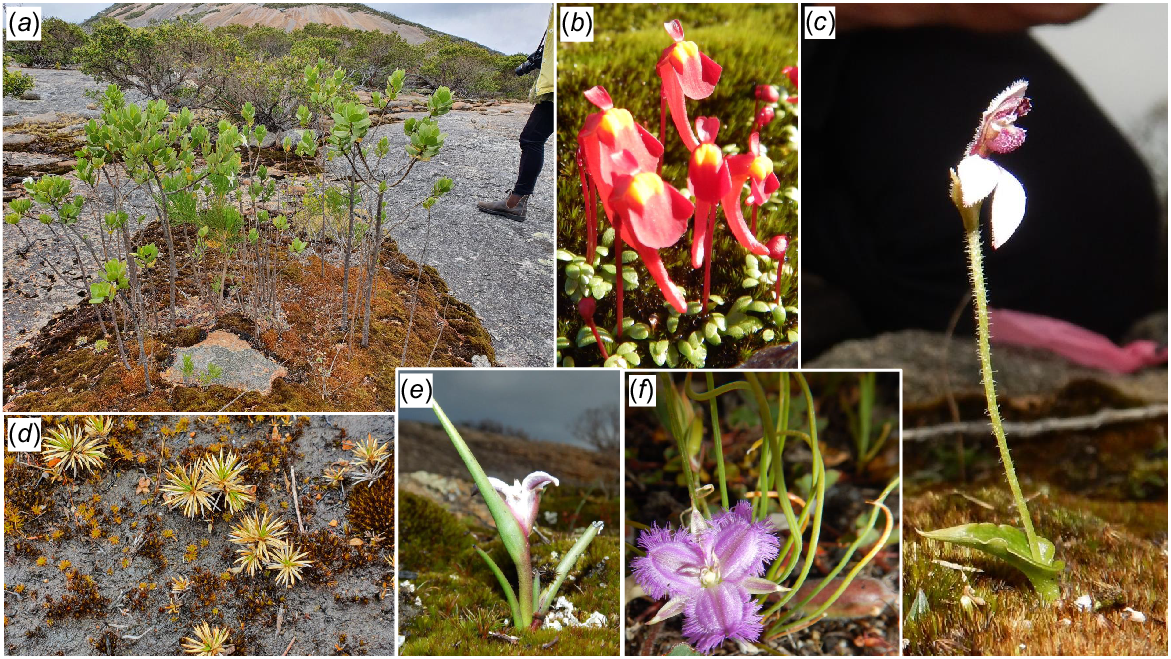

Representatives of the oldest flowering plant lineages on Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve include the order Dasypogonales (notably Dasypogon, Calectasia, and Kingia), Cephalotaceae, and Eremosynaceae (Fig. 11). Dasypogonales is, save for a single Victorian species of Calectasia, an endemic order of just four small genera confined to the SWAFR. Dasypogonales are sister either to the palms (Arecales) or to the Commelinales (containing kangaroo paws and their relatives; Givnish et al. 1999).

The oldest flowering plant lineages recorded on Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve. (a) Eremosynaceae Eremosyne pectinata; (b) Cephalotaceae Cephalotus follicularis; (c) Dasypogonales Calectasia demarzii; (d) Dasypogonales Kingia australis; (e) Dasypogonales Dasypogon bromeliifolius with Honey Possum (Tarsipes rostratus). Photos S. D. Hopper.

A species of particular interest occurring at Two Peoples Bay is the Albany Pitcher Plant, C. follicularis (Fig. 11b; Cross et al. 2019; Lymbery et al. 2016). Cephalotus is endemic to the SWAFR, where it occurs between Busselton and Yilberup/Mt Manypeaks. On the Reserve, Cephalotus can be found in the peaty swamps around Tyiurrtmiirity/Gardner Lake and Kaiupgidjukgidj/Moates Lake. It is in a monotypic family, Cephalotaceae, which is ‘nested in a mostly woody and tropical clade’ (Pillon et al. 2021), sister to the tropical South American family Brunelliaceae and the Southern Hemisphere family Elaeocarpaceae. This relationship is ancient, with the estimated date of separation of the Cephalotaceae from the other two families being more than 90 million years ago (Pillon et al. 2021).

Eremosynaceae is a second monotypic family endemic to the SWAFR found in the Reserve. DNA sequencing has revealed that Eremosyne pectinata (Fig. 11a) is sister to the South American shrub family Tribelaceae and then to the woody family Escalloniaceae of predominantly South American distribution. These three families separated approximately 85 million years ago (Wikstrom et al. 2015) in the Upper Cretaceous. Eremosyne has extremely long-lived seed (Hopper pers. observ.). It appears as adult plants the first year after disturbance, such as fire, and then persists as seeds only in the soil bank. During the first spring following the extensive November 2015 wildfire at the Reserve, Eremosyne flowered in abundance on the summit of Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner, carpeting the ground white while in flower. It has not been seen since.

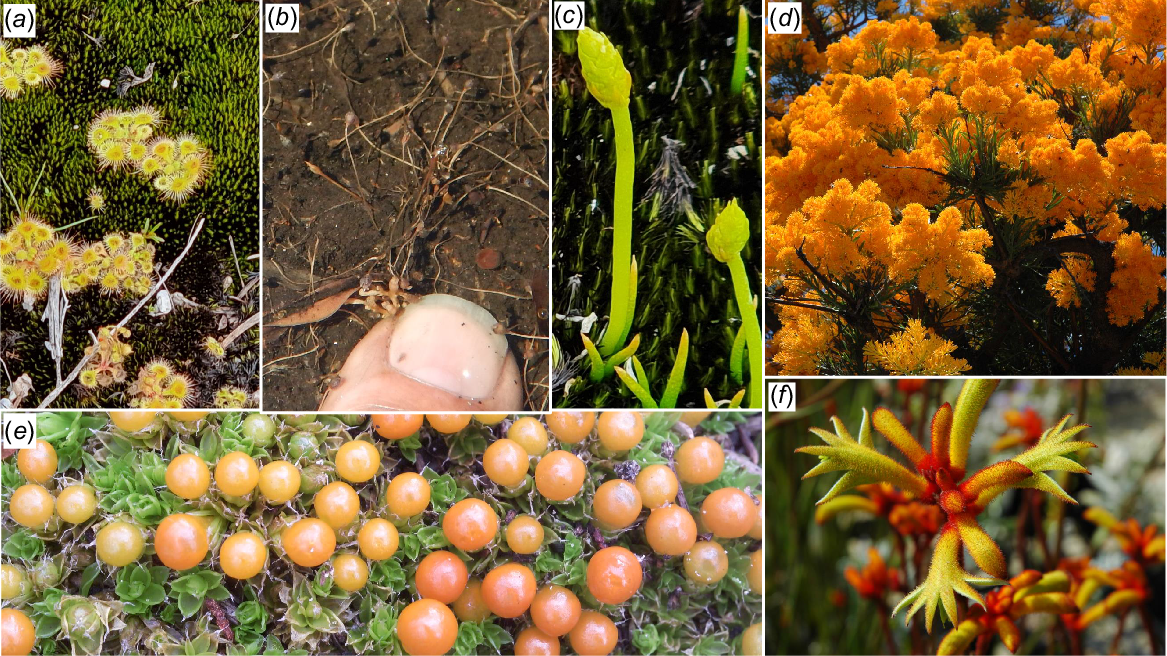

Several other plants on the Reserve occupy early branching positions in molecular phylogenies. Mosses (Fig. 12 a, e) exemplify this pattern as does the lycophyte Phylloglossum drummondii (Fig. 12c). The Reserve is the type locality of the large-leaved moss Pleurophascum occidentale (Fig. 12e) whose nearest relative occurs in the wet bogs of south-west Tasmania (Wyatt and Stoneburner 1989). Among unusual flowering plants, the tiny aquatic Trithuria austinensis (Fig. 12b) is now known as an early diverging dicot that was previously mistaken as a monocot. T. austinensis occurs in a few gnammas (rock pools) above Cape Vancouver (Fig. 1).

Other ancient lineages found at Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve. (a) Drosera glanduligera; (b) Trithuria austinensis; (c) Phylloglossum drummondii; (d) Nuytsia floribunda; (e) Pleurophascum occidentale; and (f) Anigozanthos preissii. Photos by S. D. Hopper except (e) Richie Robinson.

The distinctive arborescent mistletoe, Nuytsia floribunda (Fig. 12d), is sister to all other members of the Loranthaceae (Vidal-Russell and Nickrent 2008). This species has attracted considerable attention for generations of scientists of both European and Aboriginal descent (Hopper 2010; Lullfitz et al. 2023). Nuytsia has more than two cotyledons, woody fruits and is hemiparasitic on a diverse range of hosts. In the Haemodoraceae (Zuntini et al. 2021), one of two subfamilies (Conostylidoideae) has representatives on the Reserve in the genera Anigozanthos (kangaroo paw; Fig. 12f), Conostylis, Phlebocarya, and Tribonanthes. Of these, Tribonanthes is confined to moss mats and gnammas on the OCBIL granites of Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner. The other three genera occupy both uplands and lower country. Lastly Drosera glanduligera (Fig. 12a) is sister to all other members of the genus worldwide (Rivadavia et al. 2012). It is an annual plant however, whereas all other species are perennials. Its sticky leaf hairs move remarkably fast when touched by an insect. In general, the majority of old lineages reviewed above are found predominantly on the OCBILs of the Reserve, with some occupying the lowland YODFELs of dunes and wetlands.

Reduced hybridisation/hybrid speciation is seen on OCBILs

Natural hybrids were rarely encountered on the Reserve. Five were detected: three eucalypt species; one Adenanthos; and one Caladenia orchid. Of these, the Adenanthos (x cunninghamiiFig. 7a, b), derived through hybridising of Adenanthos cuneatus and Adenanthos sericeus, was confined to the lowland YODFEL dunes of the peninsula and Kaiupgidjukgidj/Moates Lake areas. It was swarming, forming complex populations involving backcrossing with the parental taxa (Walker et al. 2018).

The rare Caladenia × ericksoniae occurred at the foot of the granite inselberg as a solitary plant. On the Reserve, likely parents are Caladenia cairnsiana and Caladenia fuscolutescens.

The three eucalypt hybrids displayed variable population structure. The most complex, involving extensive backcrossing, was seen near Hill 700 on granite outcrops. It involved hybridisation between Eucalyptus cornuta and Eucalyptus conferruminata. E. cornuta was found in 32 of the 500 m2 grids (13% of 247 grids in total) across the Reserve, all on the Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner headland. It usually formed dense low forests or dense thickets at the edge of massive granite outcrops, but also occurred as a scattered tree in open low woodlands on the sandy lower slopes to the north of Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner. Occasionally, it occurred in low forests as a codominant with E. megacarpa around the research station and picnic ground on Two Peoples Bay proper. Other associates included C. calophylla, A. flexuosa, Eucalyptus marginata, Banksia attenuata, and M. croxfordiae.

The second parental taxon, E. conferruminata, occupied 33 grids in the eastern and southern sectors of the Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner headland. It occurred in dense shrub mallee, dense heath, or dense low forest predominantly at the edges of massive granite on coastal slopes. E. megacarpa, Eucalyptus angulosa, and C. calophylla were frequent associates. Hybrids between E. conferruminata and E. cornuta were observed at several locations on Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner.

The second eucalypt hybrid was Eucalyptus × missilis. This was the second rarest eucalypt located in just two grids (1%). Its affinities were not clear at the time of the survey in the early 1980s, but it now appears to be a stabilised hybrid of E. angulosa and E. cornuta located between West Cape Howe and Cape Arid National Park in disjunct small populations (Brooker and Hopper 2002). In the Reserve, E. angulosa occurred in disjunct populations on the eastern and southern coastlines of the Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner headland in 28 (11%) of grids. It also extended a short distance westwards towards Sinker Reef along the south side of the isthmus, with an outlier south of Tyiurrtmiirity/Gardner Lake. Usually E. angulosa was a scattered emergent from kwongkan, but occasionally it clumped to form dense shrub mallee vegetation favouring sands over limestone or granite rock edges, in varied landscape positions including on ridges, gradual slopes, and swales. It was associated frequently with E. conferruminata, Banksia praemorsa, B. attenuata, Banksia sessilis, and A. flexuosa.

The rare Eucalyptus × missilis occurred in a stand of open shrub mallee over dense low heath as a scattered emergent with E. angulosa, Eucalyptus goniantha, A. flexuosa, and B. attenuata. Sand or sand over limestone on a ridge north-west of Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner supported this vegetation.

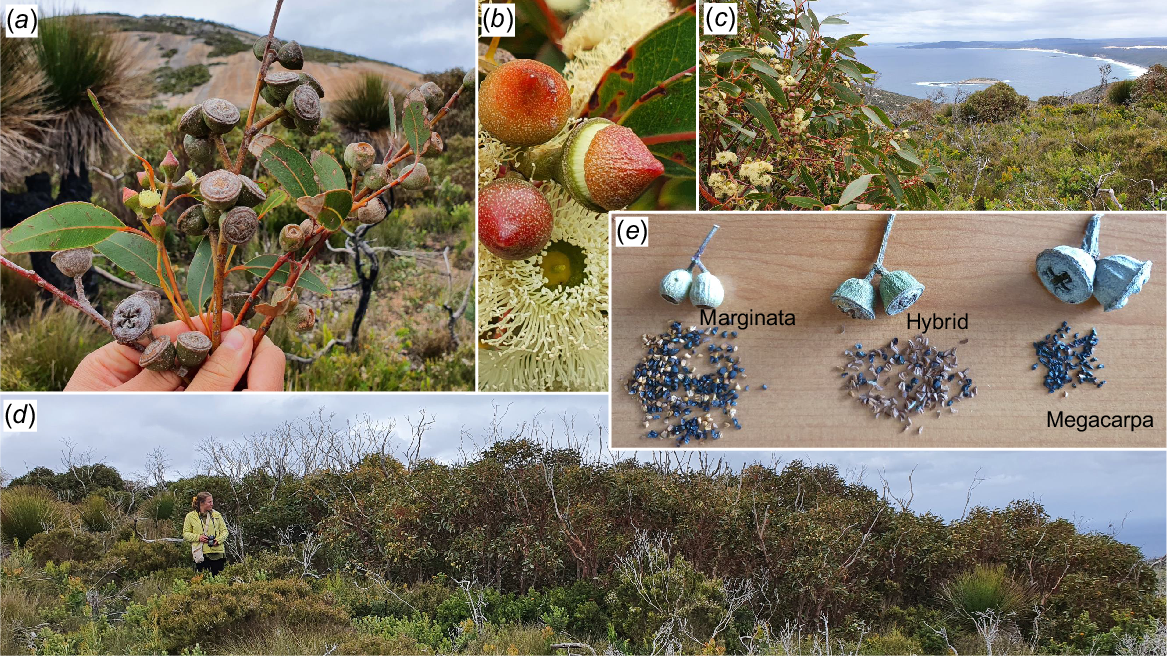

Lastly, a single large mallee of E. marginata × megacarpa was discovered on the upper western slopes of Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner in 2020. Its two parents were widespread on the inselberg (Fig. 10); and beyond in the case of E. marginata. E. marginata was the most widespread eucalypt recorded (85 grids, 34%). It was common on the Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner inselberg and north and west of Kaiupgidjukgidj/Moates Lake. The intervening areas were devoid of E. marginata, but narrow extensions down the western and northern boundaries occurred from the main north-western stands, and a few plants occupied the north-western margin of Miialyiin/Angove Lake.

The peninsula populations of E. marginata generally were stunted (Table 4). It occurred most frequently as scattered emergents from dense low heaths, thickets on sandy slopes, or at the edges of sheet granite. Common associates were C. calophylla, Banksia attenuata, B. grandis, B. coccinea, E. megacarpa, Hakea elliptica, and A. flexuosa. The taller north-western populations (Table 4) were co-dominant in low forests or open low woodlands with C. calophylla, B. grandis, B. attenuata, B. coccinea, Allocasuarina fraseriana, and Eucalyptus staeri. Sands or sands mixed with lateritic gravel on gradual slopes usually supported E. marginata.

E. megacarpa was widespread on the Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner headland but absent elsewhere except for small outlying populations bordering Miialyiin/Angove Lake and the Goodga River. E. megacarpa occupied 56 (23%) of the grids. Like E. marginata, C. calophylla, and some banksias, E. megacarpa occurred as stunted individuals in dense heaths and thickets on exposed slopes and the edges of sheet granite. E. marginata, E. conferruminata, C. calophylla, B. grandis, and B. attenuata were its associates in these situations. However, E. megacarpa also occurred in well-watered gullies, often forming dense, low forests in codominant associations with E. cornuta, C. calophylla, and M. croxfordiae. Occasionally, it was found with Banksia littoralis in dense low forests on the margins of lakes, rivers, or in coastal swamps.

E. marginata × megacarpa had been collected only four times previously, originally by H. Steedman in 1939 near the Albany Highway 48 km south-east of Perth (Pryor and Johnson 1962), and later close to the west coast of the SWAFR on the Leeuwin Naturaliste Ridge in 1975, 1982 and 1996 (Western Australian Herbarium 1998–2024). The discovery of this extremely rare hybrid in Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve was thus unexpected (Fig. 13), especially given the comprehensive grid-based survey of eucalypts undertaken of the entire Reserve in the summer of 1980/81, and many other extensive surveys undertaken subsequently by the first co--author and others. This hybrid was clearly the rarest of all plant taxa on the Reserve, rendered conspicuous by its flowering and emergence from surrounding vegetation when seen in 2000, 5 years after the November 2015 wildfire.

The rarest plant on Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve, a hybrid mallee 12 m across of the parentage Eucalyptus marginata × megacarpa. (a) Fruits and buds (only of the hybrid) of E. megacarpa, hybrid and E. marginata in situ with Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner in the background; (b) buds and flowers of the hybrid; (c) flowers and leaves of the hybrid in situ looking west at Inner Island and Nanarup Beach; (d) whole mallee recovering 5 years after the 2015 wildfire; and (e) single fruits and black seeds of the two parents and hybrid. Note the reduced seed set of the hybrid. Photos S. D. Hopper.

Greater vulnerability to frequent fires is evident on the elevated granite outcrop OCBILs of Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner rather than on lowland YODFELs

The seeder/resprouter ratio for 261 plants on granite outcrop OCBILs on the Reserve was found to be 159/103 taxa (61/39%). Phenology data for 425 species across the Reserve showed that March/April was the time of year with the fewest species in flower (20% of the total). A few species were found to flower predominantly or only in the first spring after fire, including E. pectinata (Fig. 11a), Gyrostemon sheathii, Poranthera florosa, Anigozanthos preissii (Fig. 12f), and H. serendipita (Fig. 9). Seedlings of many species were seen to be abundant mostly following fire or less often along disturbed edges of tracks. Seeder species were Gastrolobium bilobum, G. coriaceum, H. elliptica, Hakea drupacea, Anthocercis viscosa, Commersonia corniculata, C. corylifolia, C. parviflora, C. orarium, Verticordia plumosa, Dodonaea ceratocarpa, Sida hookeriana, Kennedia glabrata, Gyrostemon benthamii, Eutaxia myrtifolia, and Acacia myrtifolia. Resprouter species were Lepidosperma hopperi, L. angustatum and T. marginata. Flowering appeared more profuse after fire for some orchids (i.e. Caladenia granitora, Cyanicula gemmata, Elythranthera brunonis, and Prasophyllum spp.).

A community particularly vulnerable to fire and drought, and composed of diverse families, grew in the moss mats on granite outcrops (Fig. 14). There occasional shrub seedlings (e.g. A. viscosa, Fig. 14a) and several geophytes were found, including Eriochilus pulchellus, Eriochilus scaber (Fig. 14c), Philydrella pygmaea, Phylloglossum drummondii (Fig. 12c), Thysanotus isantherus (Fig. 14f), Tribonanthes violacea (Fig. 14e), and Utricularia menziesii (Fig. 14b). Additionally, the annual D. glanduligera (Fig. 12a) and seedlings of Borya nitida (Fig. 14d) were recorded on moss mats, the latter appearing 2 or 3 years following fire, rather than the first year after fire.

Inhabitants of mossmats, of diverse families, that are particularly vulnerable to hot fire and drought: (a) Anthocercis viscosa (Solanaceae) seedlings 5 years old; (b) Utricularia menziesii (Utriculariaceae); (c) Eriochilus scaber (Orchidaceae); (d) Borya nitida (Boryaceae) seedlings 3–4 years old; (e) Tribonanthes violacea (Haemodoraceae); (f) Thysanotus isantherus (Asparagaceae). Photos S. D. Hopper.

Some of these taxa have evolved resilience to drought through extraordinary abilities to recover from dehydration, specifically species of Borya (Porembski and Barthlott 2000), or through the development of microgeophytic seed-like corms or tubers. These structures are able to tolerate high temperatures, and are observed in Philydrella, Phylloglossum, and Utricularia, for example (Dixon et al. 1983; Płachno et al. 2020). One drought-resilient species, T. isantherus, is on the list of species of special conservation concern for the Reserve (Table 2).

Discussion

Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve has emerged in our study as a place remarkably rich in species, with 853 taxa recorded (Table S1). The Reserve sits on the wetter side of the south coastal boundary between the Bibbulmun and South East Coastal Botanical Provinces of the SWAFR (Gioia and Hopper 2017). Given the Reserve’s relatively small size, the species richness compares favourably with the much larger Fitzgerald River National Park (1748 taxa), Stirling Range National Park (1500), and Porongurup National Park (700, but see Abbott 1982), and with the similar sized Torndirrup National Park (490) south of Albany (DBCA website, accessed 6 January 2024). However, none of these larger reserves has been subject to the level of botanical scrutiny that has been conducted at Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve, and so we might expect significant increases in their recorded floras accordingly. It is interesting to note, however, that the 853 taxa on Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve represent 26.4% of the 3225 taxa known from Florabase within the Albany Local Government area (Western Australian Herbarium (1998–2024)).

Further evidence of the remarkable diversity of the Reserve is found when compared with the floristic list obtained in the Albany Regional Vegetation Survey (Sandiford and Barrett 2010). This year-long botanical survey was based on 785 floristic relevés (not quadrats) across 124,415 ha of vegetated land outside national parks and nature reserves in an area 30 km east of Albany, 30 km west, and 20 km north of Albany. Roughly equivalent to the current flora list of 853 taxa for Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve, ‘over 800’ species were recorded (Sandiford and Barrett 2010), but notably annuals and geophytes such as orchids were excluded from the final analyses of vegetation units. Our data show that these two groups represent significant numbers of taxa, especially on granite inselbergs, with the Orchidaceae the largest family on the Reserve when the efforts by experts over decades are incorporated into the inventory (see below). Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve may eventually have a flora list approaching 950–1000 species, an exceptional number given that the Reserve occupies only 4774.7 ha.

There are 23 taxa of conservation concern on the list (Table 2), including three species of Declared Rare Flora – B. verticillata, C. granitora, and A. pinaster. This new database and associated phenology information for 425 taxa enable exploration of several hypotheses in the context of OCBIL theory as follows.

Phenology

There is a clear reduction in the proportion of taxa flowering down to 20% in March–April over the course of a year (Fig. 3). The onset of rains in April appears to stimulate an increasing number of species to flower despite the falling temperatures.

The general shape of the phenology graph (Fig. 3) accords well with that for Tutanning Nature Reserve in the wheatbelt (Specht et al. 1981) although there is a higher overall level of flowering at Two Peoples Bay for all seasons except early spring. It is worth noting that many woody taxa in the Myrtaceae and Proteaceae (Agonis, Taxandria, Beaufortia, Eucalyptus, Melaleuca, Adenanthos, Banksia, and Hakea), that are important components of the vegetation, flower through late summer–autumn. Taxa in these genera are important nectar producers; thus, continuity of food resources for the many nectivorous birds, mammals (Hopper 1981), and insects is assured.

Overall, Mediterranean climates of the world have a clear lull in flowering in autumn, with peak flowering occurring in spring (Bell and Stephens 1984). However, the autumn lull declines to 0% in Chile and just a few per cent in California, Israel, South Australia, Jandakot south of Perth, and Kenwick in Perth’s eastern suburbs (Bell and Stephens 1984). The 20% lull at the Reserve is quite generous in comparison, enabling survival of honey possums, which consume their own body weight in nectar and pollen every day of the year (Hopper 1981; Bradshaw and Bradshaw 2012).

In perhaps one of the best phenological studies published (Petanidou et al. 1995), the flowering pattern found on the Reserve (Fig. 3) was replicated, with maximal flowering in spring and minimal in autumn. In Greek heathlands (phrygana), 80% of the insect-pollinated flora flowers during the spring months, with commencement of flowering correlated with declining temperature and not rainfall (Petanidou et al. 1995). More recently, Barrett and Ladd (2021) investigated flowering phenology in coastal kwongkan near Lancelin, north of Perth, finding that the most marked differences in phenology were associated with age since fire rather than substrate.

In terms of global warming and climate change, accumulated evidence suggests that drought stress in Eucalyptus wandoo can cause little to no flowering and reduced reproductive output at Dryandra Woodland and Wandoo Conservation Park in the SWAFR (Moore et al. 2016). Such effects are compounded by the impact of fire on flowering in C. calophylla in the same forests inland from Perth. Crown scorch severely inhibits flowering, which recovers at the rate of 15%/year following hot burns (Dixon et al. 2023). No such impact was recorded when only understory burnt under cooler conditions (Dixon et al. 2023). It is clear that caution in the use of prescribed burning is needed at Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve in light of these emerging trends in phenological literature.

Threatened taxa and short-range endemics are concentrated on OCBILs