A grey nurse shark from the Northern Territory of Australia shares a mitochondrial haplotype only recorded from the western Australian population

Sara Krause A B and Adam Stow A *

A B and Adam Stow A *

A

B

Abstract

The critically endangered grey nurse shark (Carcharias taurus) is a widely distributed coastal to near coastal species. Overexploitation has resulted in severe global population declines, including in Australian waters, where two genetically distinct populations are known to exist in temperate to subtropical waters off the eastern and western coasts of the continent. However, occasional sightings of C. taurus have been reported in the Timor Sea and Northern Territory waters.

In this small-scale study, we aimed to evaluate whether a single C. taurus individual captured in waters off the Northern Territory of Australia belongs to the Critically Endangered eastern Australian population.

On the basis of previously identified mitochondrial haplotypes for this species, we aligned the mtDNA control regions of the Northern Territory individual with sequence data from eastern and western Australian samples.

The sequence alignment showed a haplotype unique to western Australia (Haplotype E).

The individual caught in Northern Territory waters is genetically compatible with the western Australian population.

These data suggest that C. taurus occurring off the Northern Territory do not represent an extension of the Critically Endangered eastern coast population and also highlighted the need for future research on the understudied grey nurse shark in tropical waters off northern Australia.

Keywords: Australia, Critically Endangered species, grey nurse shark, haplotype, mitochondrial DNA, Northern Territory, shark conservation, Timor Sea, western Australia.

Introduction

Grey nurse sharks (Carcharias taurus, Rafinesque, 1810) are widely distributed, mostly in subtropical to temperate waters along continental coastlines of the major ocean basins, including the Atlantic, Indian Ocean and Western Pacific (Compagno 1984). Described as a coastal and shelf-associated species, C. taurus is generally found at depths of 10–40 m around coral and rocky reefs from the surf zone to the outer continental shelf, with reported maximum depths of 230 m (Compagno 1984; Pollard et al. 1996; Otway et al. 2003; Otway et al. 2004; Otway and Ellis 2011).

Despite being widely distributed, C. taurus has experienced a global population decline of over 80% in the past three generations; therefore, the species was globally classified as Critically Endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) in 2020 (Rigby et al. 2021). They are particularly susceptible to anthropogenic pressures because of their preference for shallow coastal habitats, aggregatory behaviour, and slow life-history traits, including late maturity and a biennial reproductive cycle (Goldman et al. 2006; Bansemer and Bennett 2011; Rigby et al. 2021; Hoschke et al. 2023). Large population declines in Australian waters resulted in C. taurus being the first protected shark species worldwide in 1984 (Pollard et al. 1996; Reid et al. 2011).

Analysis of several genetic markers, including the mtDNA control region (CR), showed generally low genetic variability for C. taurus, with only a single shared mitochondrial haplotype identified for individuals from eastern Australia, and two variants for the western population (Stow et al. 2006; Ahonen et al. 2009). The two Australian populations are genetically divergent, implying negligible migration and gene flow between the east and the west (Stow et al. 2006). Migration within the populations is directed north–southward along the coastlines, following complex patterns depending on sex and maturity with distances travelled up to 1335 km (Bansemer and Bennett 2011; Jakobs and Braccini 2019). The known Australian populations extend from the South Australian border up to Exmouth in the west (Hoschke et al. 2023) and range from the southern border of New South Wales up to Yeppoon in Queensland in the east (Otway and Ellis 2011). However, a study confirmed the unexpected presence of grey nurse sharks in tropical reefs around Browse Island, located in the Timor Sea (Momigliano and Jaiteh 2015), and anecdotal sightings had been reported from the Arafura Sea (Pollard et al. 1996).

In addition, a single C. taurus individual was reported caught in trawling nets north-west of the Tiwi Islands in the Timor Sea of the Australian Northern Territory. The remote capture of this grey nurse shark outside of the known distribution of the western and eastern Australian populations raises the question of whether it is associated with an Australian population and, if so, which population. In this small-scale study, we aim to evaluate whether the individual in question belongs to the Critically Endangered eastern Australian population on the basis of the previously identified mitochondrial haplotypes for grey nurse sharks.

Materials and methods

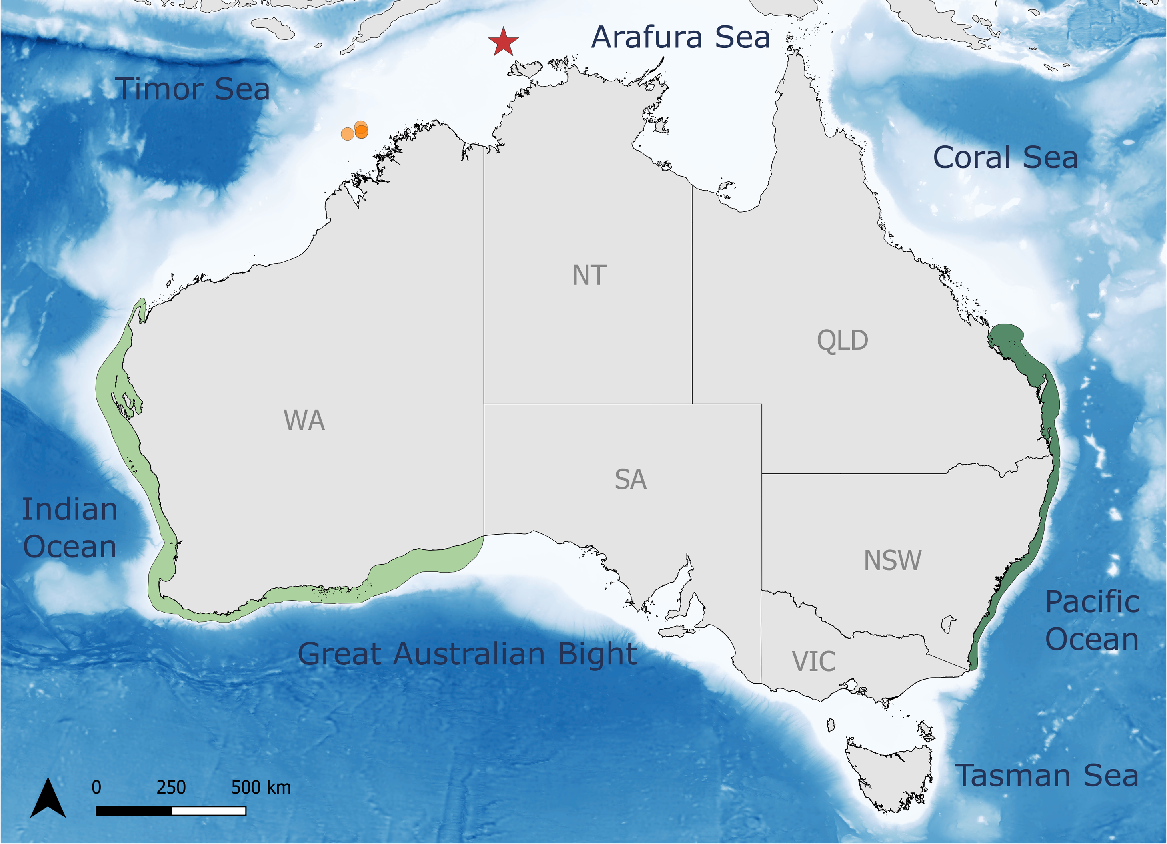

A fin clip was obtained from the single juvenile C. taurus individual (n = 1; NA) caught as accidental trawling bycatch during commercial fishing operations north-west of the Tiwi Islands (−10.4, 129.85), and a tissue sample was donated to the fisheries division at Department of Industry, Tourism and Trade, Northern Territory Government of Australia (Fig. 1). Therefore, in compliance with Macquarie University’s Animal Ethics Committee, no collecting permit was required for this sample and the principle of replacement follows the Australian Code for the Care and Use of Animals for Scientific Purposes, 8th edition (see Clauses 1.1 [v] and 1.18–1.20; National Health and Medical Research Council 2013). So as to compare mitochondrial haplotypes, previously sampled tissue from four individuals with confirmed population affiliations and known haplotypes from the Australian east (n = 2; EA25, EA33) and west (n = 2; WA3, WA5) were sequenced again for analysis. Collection and sequencing methods for these four samples have been published in (Stow et al. 2006) and (Ahonen et al. 2009). Genomic DNA was extracted from 3 mm3 of tissue for all samples (n = 5) by using the Isolate II Genomic DNA Kit (Meridian Bioscience Inc., Cincinnati, OH, USA). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was executed to amplify ~700 bp of the mitochondrial control region, applying forward (MtGNf) and reverse (MtGNr) primers designed by (Stow et al. 2006). Amplification was conducted in 40-μL reactions, containing 1× PCR Master Mix (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA), 0.5 mM of additional MgCl2, 1 μM of each primer and 6 μL of genomic DNA. In an Eppendorf Mastercycler X50s thermocycler, amplifications were performed, with initial denaturation for 3 min at 94°C, followed by 11 touch-down cycles of 94°C for 30 s, with annealing temperatures of 65, 64, 63, 62, 61, 60, 59, 58, 57, 56 and 55°C for 30 s. This was followed by an extension step of 72°C for 1 min, a further 35 cycles at 55°C annealing temperature, and a final 72°C from 5 min. PCR product purification and sequencing were conducted by Macrogen Inc. (Seoul, South Korea). The received sequences were examined for quality, aligned, and trimmed, retaining 608 sites to maintain comparability with Ahonen et al. (2009) by using SeqTrace (ver. 0.9.1, see https://github.com/stuckyb/seqtrace; Stucky 2012). Haplotypes were identified with MEGA (ver. 11.0.13, see https://www.megasoftware.net; Tamura et al. 2021).

Geographic distribution of the Australian grey nurse shark populations and capture sites in the Timor Sea. The eastern coast population (dark green) ranges from the southern border of New South Wales up to Yeppoon (Otway and Ellis 2011), and the western coast population (light green) extends from the South Australian border up to Exmouth (Hoschke et al. 2023). The capture location of the single C. taurus individual (n = 1; NA) encountered off the Northern Territory coast, north-west of Tiwi Island, is marked with a red star. Orange circles indicate the capture sites of the grey nurse sharks around Browse Island (Momigliano and Jaiteh 2015).

Results and discussion

Alignment of the sequenced mtDNA control region of the individual from the Northern Territory with sequence data from eastern and western Australian samples showed that this individual possesed a haplotype that is unique to western Australia (Haplotype E) (Table 1). Previous analysis resolved a single mtDNA haplotype (Haplotype C) from 65 individuals sampled from eastern Australia, and the western Australian Haplotype E was not identified in an additional 104 individuals sampled across four other populations, namely, South Africa, Japan, Brazil and Atlantic Northwest (Stow et al. 2006; Ahonen et al. 2009). The probability of any further haplotypes, including Haplotype E, being present within the Australian eastern coast population in addition to Haplotype C is unlikely (<5%) (Stow et al. 2006; Ahonen et al. 2009). Therefore, this grey nurse shark is unlikely to belong to the Australian eastern coast population and is genetically compatible with the western coast population.

| Sample (DNA ID) | Location | Nucleotide position | Haplotype | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 182 | 330 | 339 | ||||

| EA25 | Eastern Australia | A | A | G | Haplotype C | |

| EA33 | Eastern Australia | A | A | G | Haplotype C | |

| NA | Northern Australia | G | G | A | Haplotype E | |

| WA3 | Western Australia | G | G | A | Haplotype E | |

| WA5 | Western Australia | G | G | A | Haplotype E | |

Comparison of identified haplotypes for the C. taurus individual caught in Northern Territory waters (NA) with confirmed eastern (EA25, EA33) and western (WA3, WA5) coast population samples on the basis of mitochondrial control region sequencing. Polymorphic nucleotide positions are comparable to those of Ahonen et al. (2009), with variable positions displayed only for Haplotypes C and E. The data from the Northern Territory samples are highlighted in bold as the main focus of this study.

The western Australian population of grey nurse sharks is listed as Near Threatened by the IUCN, on the basis of previously available bycatch records and is estimated to be larger and more stable than the Critically Endangered eastern coast population (Pollard et al. 2003a, 2003b). Because C. taurus has been protected in Western Australian waters since 1999 and in all Commonwealth waters since 1997 (Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999), bycatch and illegal fishing present the most likely threats to this species in the Northern Territory waters. Although the national recovery plan for the grey nurse shark established in 2002 applies nationwide (Department of the Environment 2014), including targets for research and conservation measures, no specific conservation program for this species exists in the Northern Territory.

The grey nurse shark examined in this study, estimated to be a juvenile, was encountered on the broad northern shelf extension of the Australian continent. At the location of capture, the continental shelf reached a maximum depth of ~100 m, similar to the individuals caught off Browse Island with demersal longlines set at depths of 50–90 m (Momigliano and Jaiteh 2015). The estimated capture depths of C. taurus in the Timor Sea are within the species known maximum depth of 230 m (Otway and Ellis 2011). The documented subsurface temperatures at these low latitudes range from ~26 to 30°C within the sharks’ commonly occupied water depths of 10–40 m (Otway et al. 2003, 2004; Wirasantosa et al. 2011) and, therefore, exceed the species’ favoured temperatures of between 17 and 24°C (Otway and Ellis 2011; Hoschke et al. 2023). However, at depths of 100 m in the Timor Sea, lower water temperatures of ~22 to 24°C were recorded (Wirasantosa et al. 2011), falling within the upper range of the grey nurse sharks’ preferred temperatures. We therefore suggest that water temperature may explain the depths at which these sharks have been observed in tropical waters.

Conclusions

We have provided evidence that grey nurse sharks are found in the Timor Sea within the waters of the Northern Territory, and the individual sampled possesses a mitochondrial haplotype that has thus far been identified only in the western Australian population. The location of this sampled individual is consistent with records of grey nurse sharks being caught at low latitudes in tropical waters around Bali and the Timor Sea (White et al. 2006; Momigliano and Jaiteh 2015). Whether individuals from these tropical waters are transient, belong to unknown populations, or are an extension of the Australian western coast population remains unknown. Resolving the population status will contribute towards evaluating the risks facing this globally Critically Endangered species and the conservation measures currently in place in the Northern Territory of Australia.

Data availability

The mtDNA sequences supporting the findings of this study will be available in GenBank.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to Michael Usher, Senior Research Scientist at the Fisheries Division of the Northern Territory Government of Australia, for providing us with the Northern Territory grey nurse shark tissue sample. Sincere thanks are also extended to Rory McAuley (WA Fisheries) and Nicholas Otway (NSW Fisheries) for collecting samples from western Australia and eastern Australia respectively, and the NSW Department of Primary Industries.

References

Ahonen H, Harcourt RG, Stow AJ (2009) Nuclear and mitochondrial DNA reveals isolation of imperilled grey nurse shark populations (Carcharias taurus). Molecular Ecology 18, 4409-4421.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Bansemer CS, Bennett MB (2011) Sex- and maturity-based differences in movement and migration patterns of grey nurse shark, Carcharias taurus, along the eastern coast of Australia. Marine and Freshwater Research 62, 596-606.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Compagno LJV (1984) ‘FAO species catalogue. Vol. 4. Sharks of the world. An annotated and illustrated catalogue of shark species known to date. Part 1. Hexanchiformes to Lamniformes’, 1st edn. (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy) Available at https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/1b650fd0-3675-43cc-adcf-876cdc5a001f/content

Department of the Environment (2014) Recovery Plan for the Grey Nurse Shark (Carcharias taurus). (Commonwealth of Australia) Available at www.environment.gov.au/resource/recovery-plan-grey-nurse-shark-carcharias-taurus

Goldman KJ, Branstetter S, Musick JA (2006) A re-examination of the age and growth of sand tiger sharks, Carcharias taurus, in the western North Atlantic: the importance of ageing protocols and use of multiple back-calculation techniques. In ‘Special issue: age and growth of chondrichthyan fishes: new methods, techniques and analysis’. (Eds JK Carlson, KJ Goldman) pp. 241–252. (Springer: Dordrecht, Netherlands)

Hoschke AM, Whisson GJ, Haulsee D (2023) Population distribution, aggregation sites and seasonal occurrence of Australia’s western population of the grey nurse shark Carcharias taurus. Endangered Species Research 50, 107-123.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Jakobs S, Braccini M (2019) Acoustic and conventional tagging support the growth patterns of grey nurse sharks and reveal their large-scale displacements in the west coast of Australia. Marine Biology 166, 150.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Momigliano P, Jaiteh VF (2015) First records of the grey nurse shark Carcharias taurus (Lamniformes: Odontaspididae) from oceanic coral reefs in the Timor Sea. Marine Biodiversity Records 8, e56.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

National Health and Medical Research Council (2013) ‘Australian code for the care and use of animals for scientific purposes’, 8th edn. (NHMRC) Available at https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/attachments/Australian-code-for-the-care-and-use-of-animals.pdf

Otway NM, Ellis MT (2011) Pop-up archival satellite tagging of Carcharias taurus: movements and depth/temperature-related use of south-eastern Australian waters. Marine and Freshwater Research 62, 607-620.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Otway NM, Burke AL, Morrison NS, Parker PC (2003) Monitoring and identification of NSW Critical Habitat Sites for conservation of Grey Nurse Sharks. Final report to Environment Australia, project number 22499. NSW Fisheries final report series number 47. (NSW Fisheries) Available at https://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/545631/FFRS-47_Otway-et-al-2003.pdf

Otway NM, Bradshaw CJA, Harcourt RG (2004) Estimating the rate of quasi-extinction of the Australian grey nurse shark (Carcharias taurus) population using deterministic age- and stage-classified models. Biological Conservation 119, 341-350.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Pollard DA, Lincoln Smith MP, Smith AK (1996) The biology and conservation status of the grey nurse shark (Carcharias taurus Rafinesque 1810) in New South Wales, Australia. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems 6, 1-20.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Pollard D, Gordon I, Williams S, Flaherty A, McAuley R (2003a) Carcharias taurus East coast of Australia subpopulation. In ‘The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2003’. e.T44070A10854830. (International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources) Available at https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/44070/10854830

Pollard D, Gordon I, Williams S, Flaherty A, McAuley R (2003b) Carcharias taurus Western Australia subpopulation. In ‘The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2003’. e.T44071A10854958. (International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources) Available at https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/44071/10854958

Reid DD, Robbins WD, Peddemors VM (2011) Decadal trends in shark catches and effort from the New South Wales, Australia, Shark Meshing Program 1950–2010. Marine and Freshwater Research 62, 676-693.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Rigby CL, Carlson J, Derrick D, Dicken M, Pacoureau N, Simpfendorfer C (2021) Sand tiger shark Carcharias taurus. In ‘The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2021’. e.T3854A2876505. (International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources) Available at https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/3854/2876505

Stow A, Zenger K, Briscoe D, Gillings M, Peddemors V, Otway N, Harcourt R (2006) Isolation and genetic diversity of endangered grey nurse shark (Carcharias taurus) populations. Biology Letters 2, 308-311.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Stucky BJ (2012) SeqTrace: a graphical tool for rapidly processing DNA sequencing chromatograms. Journal of Biomolecular Techniques 23, 90-93.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Tamura K, Stecher G, Kumar S (2021) MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 11. Molecular Biology and Evolution 38, 3022-3027.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Wirasantosa S, Wagey T, Nurhakim S, Nugroho D (Eds) (2011) ATSEA cruise report, second edition. (ATSEA Program) Available at https://atsea-program.com/publication/atsea-cruise-report/