Australians’ perceptions of species diversity of, and threats to, the Great Barrier Reef

Jarrah Taylor A , Carla Litchfield A and Brianna Le Busque B C *

B C *

A

B

C

Abstract

The Great Barrier Reef (GBR) is under threat from multiple anthropogenic activities such as tourism and climate change. Understanding participants’ knowledge about the GBR can encourage conservation of the GBR.

This study investigated what participants, whom were all Australian, know about the GBR, the species that reside there and the threats to the GBR ecosystem.

Participants (n = 113), recruited by social media, completed a short online survey that included four open-ended items exploring various aspects of GBR knowledge.

Results indicated that participants identified a range of threats to GBR, that fell into broad categories of environmental and social impacts. Results also showed that the most common broad taxa identified were fish, coral and reptiles, and that clown fish were the most common specific GBR species identified.

In conclusion, this study has provided evidence of limited knowledge of species that live in the GBR, and basic broad knowledge of threats to the GBR.

This study has contributed new insights regarding knowledge of GBR and recognition of animals that live in the GBR to show where public awareness campaigns should be focused and highlighted avenues for future research.

Keywords: conservation, Great Barrier Reef, knowledge, marine species, ocean literacy, perceptions, public awareness, threats.

Introduction

The Great Barrier Reef (GBR), located in Queensland Australia, is the largest coral reef system in the world covering 344,400 km2. The GBR is a World Heritage Area, so as to protect it for future generations, and is considered one of the seven natural wonders of the world (see the UNESCO World Heritage List at https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/). The GBR supports over 6000 species of corals, fish (including many shark and ray species), molluscs, sea snakes, birds, sea turtles and marine mammals (Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority 2022).

The GBR is important to Australia environmentally, economically, culturally and scientifically (for a comprehensive overview, see Carr and Mendelsohn 2003; Stoeckl et al. 2011). In 2015–2016, the GBR contributed A$6.4 billion and over 64,000 jobs (direct and indirect) into the Australian economy (O’Mahoney et al. 2017 ) through tourism activities. Even during the COVID-19 pandemic, in 2021, more than 1 million tourists visited the GBR (Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority 2022). Because many tourists visit the GBR to experience the ecosystem, Ceccarelli and Ayling (Ceccarelli and Ayling 2010) found that declines in coral and fish biodiversity on the GBR could reduce visitor numbers by as much as 80% which would correspond to a loss of A$103 million in tourism revenue alone.

Most threats to the GBR are anthropogenic rather than naturogenic (e.g. outbreaks of coral-eating crown-of-thorns starfish; Green et al. 1999; Pratchett et al. 2017), and include climate change, coastal development, agricultural and runoff pollution, unsustainable fishing practices, and unsustainable tourism practices (e.g. Starck 2005; Pearson et al. 2021; Walpole and Hadwen 2022). Given the multifaceted importance of the GBR, and the various anthropogenic threats facing the health and prosperity of this World Heritage site, it is important to understand people’s knowledge and perceptions of these reefs (Gooch et al. 2017; Manfredo et al. 2021).

Research published in a technical report from over 20 years ago found that approximately half of the sample (n = 1003), in a randomised telephone survey, living in either Melbourne, Sydney, Brisbane, Canberra or adjacent the GBR, stated that they believed the most serious threats to the GBR were pollution and rubbish, general human impact, tourism, and crown-of-thorns starfish (Green et al. 1999). An Australian government report, which measured attitudes and awareness of the GBR found that northern Queensland residents stated that water pollution was the biggest threat to the GBR, whereas residents from Brisbane, Melbourne and Sydney reported climate change and coral bleaching as the biggest threat (Young and Temperton 2008). Updated research in this space is required, because these earlier studies provide a snapshot in time that is more than a decade old.

Understanding and increasing the public’s knowledge is an important aspect of conservation research and initiatives, especially given that many conservation programs rely on the Information Deficit Model, where information transfers from scientists to lay audiences so as to address gaps in knowledge (e.g. Suldovsky 2017). Indeed, improving ocean literacy as a way of engaging communities in conservation and pro-environmental behaviour is receiving attention as scientists and policy-makers struggle with maintaining healthy oceans (Paredes-Coral et al. 2021; Cavas et al. 2023). Even though, alone, adequate knowledge about an issue is not sufficient to change human behaviour (McKenzie-Mohr 2000), it is necessary in facilitating engagement in conservation issues. It is therefore important to understand what Australians know about the GBR, the species that reside there, and about the threats to the GBR ecosystem. Specifically, this research investigates the following:

Methods

Procedure and participants

This research received human ethics approval from the University of South Australia (#204744). A short 10-min Qualtrics survey was distributed by social media (Facebook and Instagram) through a general snowball methodology. Participants were able to enter a draw to win a gift card. The survey was open from July to August in 2022. The participants were Australian citizens (n = 113), with the sample comprising of 69.9% women. Participants were between 18 years and 84 years of age (M = 34.8, s.d. = 16.5), and resided in South Australia (55.7%), Queensland (17.7%), New South Wales (14.2%) and Victoria (6.19%). Approximately half of all participants lived 11–50 km away from the nearest ocean (49.5%).

Measures

The survey consisted of general demographic questions asking participants for age, gender and location data. Four open-ended questions were used to elicit responses related to each research question:

Data analysis

The open-ended data responses regarding where the GBR is located, which species live on the GBR, and why the GBR is important to Australia were categorised using content analysis principles (Krippendorff 2004). Given that participants provided a range of responses regarding the species that live on the GBR, using terms that were not species, such as specific taxa (e.g. dolphin), broad taxon categories (e.g. marine mammals), and both scientific and general names, results for a variety of categories are presented. This includes presenting the broad taxon categories that were evident in more than 5% of responses, listing more specific taxon class categories that were evident in 5% of responses, and the most common species listed. When reporting these results, percentages will add up to more than 100%, owing to multiple responses by individual participants. For reasons why the GBR is important to Australia, responses fit clearly into broader ‘environmental importance’ and ‘socio-cultural importance’ categories and are therefore presented in this way. The open-ended data collected regarding the current threats facing the GBR were coded into themes on the basis of thematic analysis principles (Braun and Clarke 2006).

Results

Where do participants think the GBR is located?

Most of the participants (86.72%) correctly identified that the Great Barrier Reef is in the state of Queensland. Of these, many participants were more specific in their responses, stating that the Great Barrier Reef is in north-eastern Queensland (19%) or northern Queensland (7%), with a smaller number of participants providing very specific locations such as Port Douglas (n = 1), Townsville (n = 3), Airlie Beach (n = 3) or Cairns (n = 3). A few participants (4.42%) stated that they did not know the location, with ~2% of participants incorrectly listing the location as Northern Territory (0.88%) or Port Noarlunga, South Australia (0.88%).

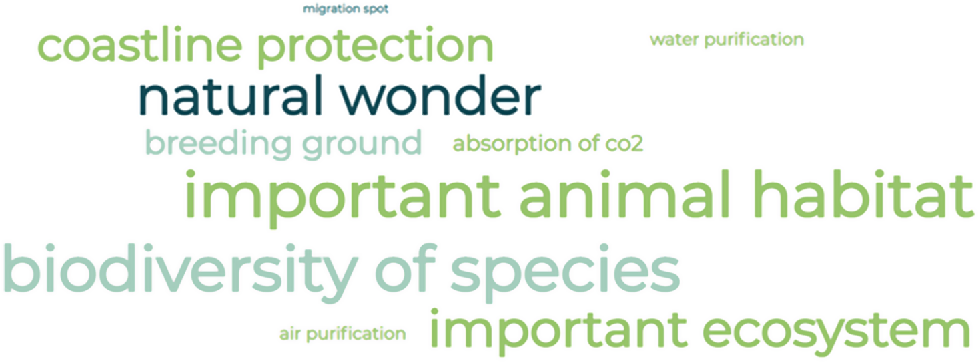

Why do participants believe the GBR is important to Australia?

The most common environmental importance factors identified by participants (Fig. 1) include that the GBR is an important habitat for a range of species (48%), that it is a natural wonder associated with Australia (27%) and that is in an important ecosystem (24%). The socio-cultural factors that make the GBR important to Australia stated by the participants (Fig. 2) are that the GBR is a well-known tourist attraction (44%), it brings in money for the Australian economy (9%) and that it is an area for scientific research opportunities (4%).

What species do participants think live in the GBR?

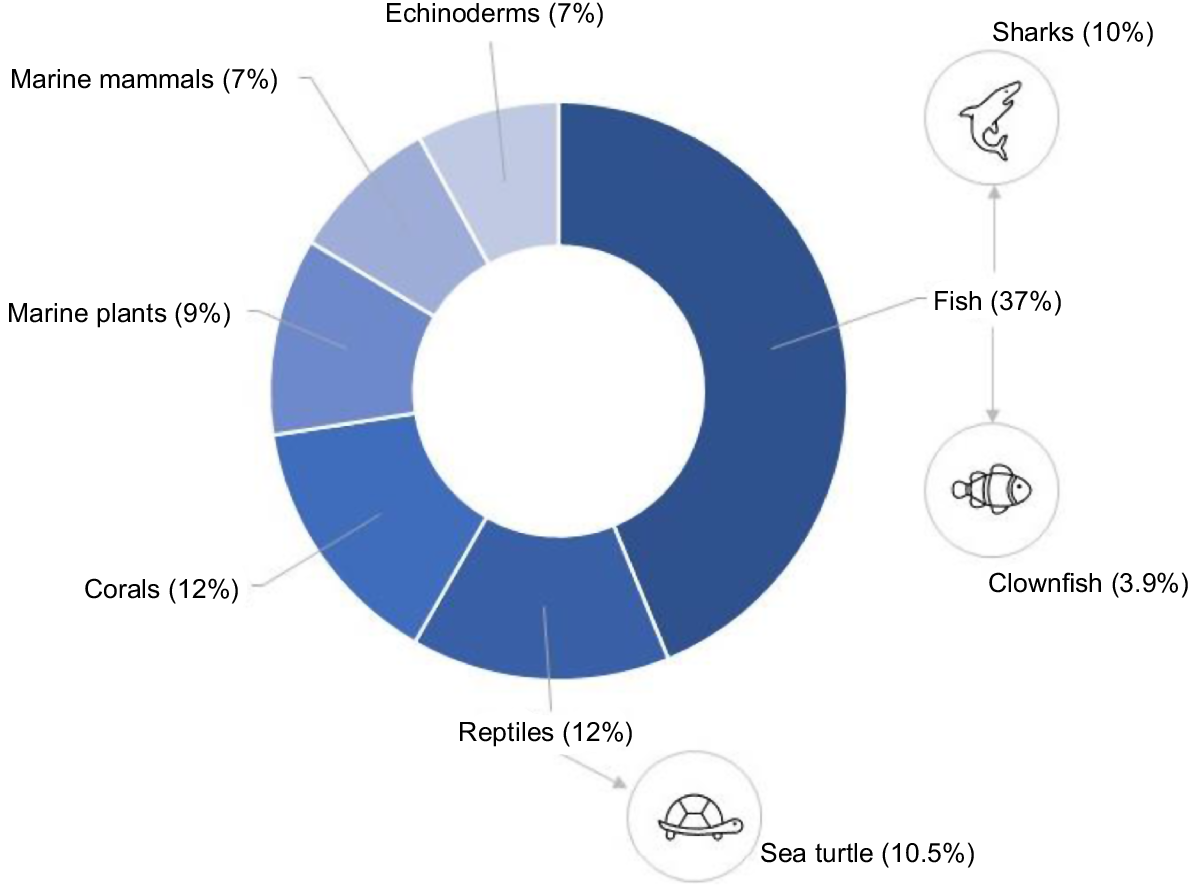

As already mentioned, participants rarely provided nomenclature for marine fauna or flora at the species level. The most frequent broad taxon categories listed were fish (37%), reptiles (12%) and corals (12%). Sea turtles and sharks were the only more specific class taxon categories present in 10% of responses or more, and clownfish was the most frequently reported species (3.9%; see Fig. 3).

What threats do participants think the GBR is facing?

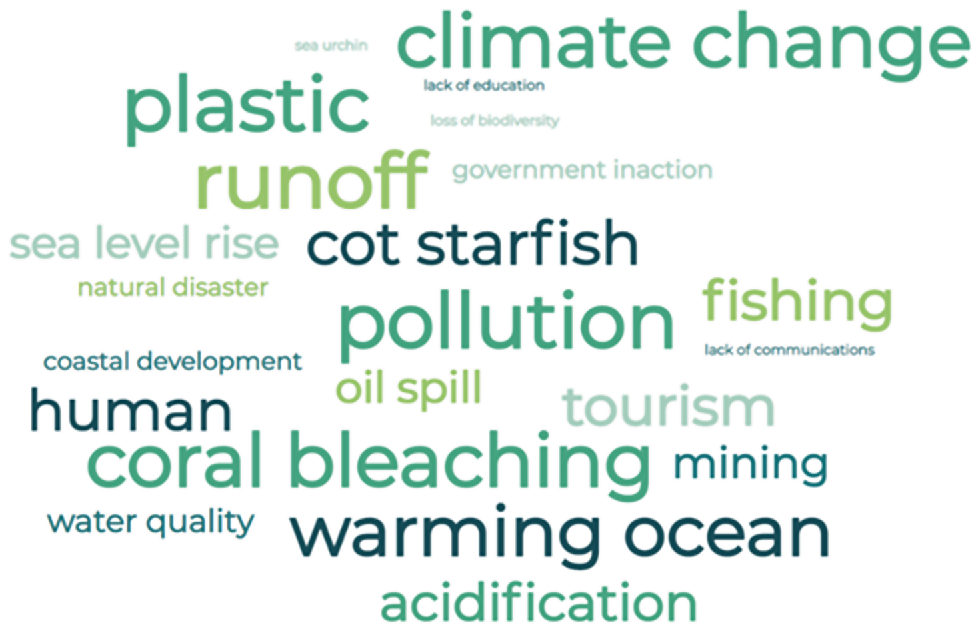

Runoff, pollution and plastics (36%), coral bleaching (34%), climate change (33%) and warming oceans (24%) were all commonly mentioned threats to the GBR. Of 18 threats reported by participants, only 3 were naturogenic threats (crown-of-thorns starfish, natural disasters and sea urchins), whereas the remaining threats were all anthropogenic in nature (see Fig. 4).

Discussion

This research used qualitative data to explore knowledge of the GBR, which is an ecosystem that is particularly important to Australia and is facing various threats. Most participants correctly identified that the GBR is located in the Australian state of Queensland, and listed various environmental and socio-cultural reasons for why the GBR is important to Australia. This recognition of ecosystem importance underscores the holistic understanding required for addressing complex challenges, such as climate change. Recognition of the interconnectedness between socio-cultural and environmental factors allows for development of comprehensive strategies that protect the environmental health of the GBR while also promoting the well-being of the communities that depend on it.

It is not surprising that although participants in our study listed numerous types of marine life for the GBR, among the most frequent responses were fish and coral. Images of both coral and fishes have long been used in tourism campaigns for the GBR and also in ‘Save the Reef’ campaigns, dating back to the 1970s (Foxwell-Norton and Konkes 2022). This reliance on coral and fishes in campaigns may explain our finding, because the consistent use of images are powerful in shaping perceptions (Coghlan et al. 2017). In terms of ocean literacy, specifically taxonomic classification, the participants in our study rarely listed flora or fauna at the species level, but instead provided broad or common names, which suggests that participants did not know, or were unsure of, the definition of ‘species’. It is important to note that we were not expecting participants to provide the scientific name for the species, but instead were wanting to see whether participants would identify flora and fauna at a more niche species level (e.g. reef shark, instead of shark). The most common specific species identified was clownfish, which was the seventh-most common response. This may have been a popular response owing to media portrayals in Finding Nemo, which was based on the GBR. The popularity of Finding Nemo is consistent with how digital media, and popular culture, can raise the public profile of charismatic species, which can lead to conservation support (Clark and May 2002). In this sense, clownfish are a flagship species for the GBR, which is the use of a ‘cute’ species to draw attention to an ecosystem (Smith and Sutton 2008). It is also interesting to note that three of the ‘Great 8’ GBR species (Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority 2022) were commonly listed, namely, clownfish, sharks and sea turtles, whereas manta rays, giant clams, whales and Māori wrasse species were infrequently listed by participants and there were no mentions of potato cod. The ‘Great 8’ is a tourism initiative, akin to the ‘Big 5’ in Africa (Caro and Riggio 2014), where eight common species on the GBR are promoted to reflect ‘the diversity and beauty of the World Heritage Listed Marine Park’ (Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority 2022); however, from our results it is clear that many of these species selected are not well known. Further, only three species that are classified by the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List of Threatened Species as Endangered or Critically Endangered were identified, namely, the green turtle (Chelonia mydas, Endangered; Seminoff 2023), staghorn coral (Acropora cervicornis, Critically Endangered; Crabbe et al. 2022) and the great hammerhead shark (Sphyrna mokarran, Critically Endangered; Rigby et al. 2019). Fewer than 1% of responses included birds (sea birds and seagulls), when the GBR supports breeding populations of 20 seabird species (Congdon 2019; Woodworth et al. 2021). This finding highlights the need for more education of endangered and critically endangered species living in the GBR, which are under threat from human activities.

It is important to note that this study utilised a convenience sample recruited by social media advertisements. However, attempts were made to increase the generalisability of the sample by using a snowballing approach and posting the advertisements on various types of social media accounts and pages. The purpose of this research was to broadly explore people’s knowledge of the GBR, which is why open-ended questions were used to collect qualitative data. This kind of text-based data provide new insights into peoples’ knowledge, because no prompts were provided. This is linked to memory retrieval, and whether the measure is based on recognition or recall of information. For example, if a list of species was provided to participants, for them to select which ones they are aware of, this would measure recognition, which is easier. Open-ended questions without prompts, require recall of knowledge of species or recognition of animals, which is harder. However, the combination of using open-ended items and having a smaller sample, affects the generalisability of our results and our ability to conduct comparison analyses to look at differences between demographics (Neuendorf 2018), because this typically requires larger samples and quantitative data. Importantly, on the basis of our qualitative findings, Likert scales could be developed to explore participants’ knowledge of threats to GBR, importance of GBR and species in the GBR. This will allow future research to explore knowledge of the GBR in a broader sample where demographic comparisons can be tested.

Conclusions

This study was able to extend the knowledge base from Green et al. (1999) and Young and Temperton (2008) with current data from Australians in 2022 and contribute new findings. As a snapshot of Australian ocean literacy specific to the GBR, this study has provided preliminary evidence of limited knowledge of species that live in the GBR, and basic broad knowledge of threats to the GBR. Although unable to mention specific species that lived in the GBR, participants recognised the importance of the GBR as an ecosystem. Surprisingly, ~6% of the participants did not know where the GBR was located. These findings help identify existing knowledge gaps in public awareness or literacy related to the GBR and marine biodiversity. Understanding Australians knowledge of the GBR and which species are well known allows resources to be assigned to specific areas to increase public awareness including targeted education and outreach programs. Future studies should seek to survey a larger number of participants that are more representative of the Australian population as a whole.

Data availability

The data that support this study will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3(2), 77-101.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Caro T, Riggio J (2014) Conservation and behavior of Africa’s ‘Big Five’. Current Zoology 60(4), 486-499.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Carr L, Mendelsohn R (2003) Valuing coral reefs: a travel cost analysis of the Great Barrier Reef. AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment 32(5), 353-357.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Cavas B, Acik S, Koc S, Kolac M (2023) Research trends and content analysis of ocean literacy studies between 2017 and 2021. Frontiers in Marine Science 10, 1200181.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ceccarelli D, Ayling T (2010) Role, importance and vulnerability of top predators on the Great Barrier Reef: a review. Research publication number 105. (Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority: Townsville, Qld, Australia) Available at https://hdl.handle.net/11017/189

Clark JA, May RM (2002) Taxonomic bias in conservation research. Science 297(5579), 191-192.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Coghlan A, McLennan CL, Moyle B (2017) Contested images, place meaning and potential tourists’ responses to an iconic nature-based attraction ‘at risk’: the case of the Great Barrier Reef. Tourism Recreation Research 42(3), 299-315.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Crabbe J, Rodríguez-Martínez R, Villamizar E, Goergen L, Croquer A, Banaszak A (2022) Staghorn coral Acropora cervicornis. In ‘The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2022’. e.T133381A165860142. (International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources) Available at https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/133381/165860142

Foxwell-Norton K, Konkes C (2022) Is the Great Barrier Reef dead? Satire, death and environmental communication. Media International Australia 184(1), 106-121.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Gooch M, Curnock M, Dale A, Gibson J, Hill R, Marshall N, Molloy F, Vella K (2017) Assessment and promotion of the Great Barrier Reef’s human dimensions through collaboration. Coastal Management 45(6), 519-537.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (2022) GREAT 8. (Australian Government) Available at https://www2.gbrmpa.gov.au/learn/animals/great-8

Green D, Moscardo G, Greenwood T, Pearce P, Arthur M, Clark A, Woods B (1999) Understanding public perceptions of the Great Barrier Reef and its management. CRC reef research centre technical report number 29. (CRC Reef Research Centre: Townsville, Qld, Australia) Available at https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=9df05aff679ec7253fa16f76366d2b41e091a9c3

McKenzie-Mohr D (2000) Fostering sustainable behavior through community-based social marketing. American Psychologist 55(5), 531.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

O’Mahoney J, Simes R, Redhill D, Heaton K, Atkinson C, Hayward E, Nguyen M (2017) At what price? The economic, social and icon value of the Great Barrier Reef. (Deloitte Access Economics) Available at https://elibrary.gbrmpa.gov.au/jspui/bitstream/11017/3205/1/deloitte-au-economics-great-barrier-reef-230617.pdf

Paredes-Coral E, Mokos M, Vanreusel A, Deprez T (2021) Mapping global research on ocean literacy: implications for science, policy, and the blue economy. Frontiers in Marine Science 8, 648492.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Pearson RG, Connolly NM, Davis AM, Brodie JE (2021) Fresh waters and estuaries of the Great Barrier Reef catchment: effects and management of anthropogenic disturbance on biodiversity, ecology and connectivity. Marine Pollution Bulletin 166, 112194.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Pratchett MS, Caballes CF, Wilmes JC, Matthews S, Mellin C, Sweatman HPA, Nadler LE, Brodie J, Thompson CA, Hoey J, Bos AR, Byrne M, Messmer V, Fortunato SAV, Chen CCM, Buck ACE, Babcock RC, Uthicke S (2017) Thirty years of research on crown-of-thorns starfish (1986–2016): scientific advances and emerging opportunities. Diversity 9(4), 41.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Rigby CL, Barreto R, Carlson J, Fernando D, Fordham S, Francis MP, Herman K, Jabado RW, Liu KM, Marshall A, Pacoureau N, Romanov E, Sherley RB, Winker H (2019) Great hammerhead Sphyrna mokarran. In ‘The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2019’. e.T39386A2920499. (International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources) Available at https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/39386/2920499

Seminoff JA (2023) Green turtle Chelonia mydas (amended version of 2004 assessment). In ‘The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2023’. e.T4615A247654386. (International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources) Available at https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/4615/247654386

Smith AM, Sutton SG (2008) The role of a flagship species in the formation of conservation intentions. Human Dimensions of Wildlife 13(2), 127-140.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Starck W (2005) ‘Threats’ to the Great Barrier Reef. Backgrounder 17, 1.

| Google Scholar |

Stoeckl N, Hicks CC, Mills M, Fabricius K, Esparon M, Kroon F, Kaur K, Costanza R (2011) The economic value of ecosystem services in the Great Barrier Reef: our state of knowledge. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1219(1), 113-133.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Suldovsky B (2017) ‘The information deficit model and climate change communication.’ (Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Climate Science) 10.1093/acrefore/9780190228620.013.301

Walpole LC, Hadwen WL (2022) Extreme events, loss, and grief – an evaluation of the evolving management of climate change threats on the Great Barrier Reef. Ecology and Society 27(1), 37.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Woodworth BK, Fuller RA, Hemson G, McDougall A, Congdon BC, Low M (2021) Trends in seabird breeding populations across the Great Barrier Reef. Conservation Biology 35(3), 846-858.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Young J, Temperton J (2008) Measuring community attitudes and awareness towards the Great Barrier Reef 2007. Research publication number 90. (Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority: Townsville, Qld, Australia) Available at https://hdl.handle.net/11017/421