Recognising diversity in wetlands and farming systems to support sustainable agriculture and conserve wetlands

Anne A. van Dam A , Hugh Robertson B , Roland Prieler

A , Hugh Robertson B , Roland Prieler  A , Asmita Dubey A and C. Max Finlayson

A , Asmita Dubey A and C. Max Finlayson  A C D *

A C D *

A

B

C

D

Abstract

Agriculture is a main driver of decline in wetlands, but in addressing its impact the diversity in agricultural systems and their catchment interactions must be recognised.

In this paper, we review the impacts of food production systems on wetlands to seek a better understanding of agriculture–wetland interactions and identify options for increasing sustainability.

Eight farming-system types were defined on the basis of natural resource use and farming intensity, and their impact on different wetland types was assessed through their direct drivers of change. Indirect drivers (such as decision-making in food systems, markets and governance) were also summarised.

Findings showed that most inland wetlands are influenced by farming directly, through changes in water and nutrient supply and use of pesticides, or indirectly through catchment water, sediment and nutrient pathways. Coastal wetlands are mostly influenced indirectly.

More sustainable food production can be achieved through continued protection of wetlands, improving efficiency in agricultural resource use generally, but also through more integration within production systems (e.g. crop–livestock–fish integration) or with wetlands (integrated wetland–agriculture).

More support for small-scale producers will be needed to ensure a transformation towards balancing the provisioning, regulating and cultural ecosystem services of wetland agroecosystems within catchments.

Keywords: catchment management, farming systems, food systems, livelihoods, Ramsar Convention, sustainable agriculture, wetland ecosystem services, wise use of wetlands.

Introduction

Wetlands provide a wide range of ecosystem services, from food production, regulation of water quality, and flood protection to climate-change mitigation and habitat for many animal and plant species (Finlayson et al. 2005; Russi et al. 2013; Gardner and Finlayson 2018). They also support human livelihoods and sustainable development (Ramsar Convention 2018). Despite their importance for humankind, the global area of natural wetlands has been declining from before 1700, with a peak in loss rates in the mid-20th Century (Fluet-Chouinard et al. 2023). Since 1700, where data are available, ~21% of the world’s wetlands have been lost, with those remaining under pressure from drainage, pollution, invasive species, unsustainable use, disrupted flow regimes and climate change (Fluet-Chouinard et al. 2023).

Since c. 1950, the world population more than tripled from ~2.5 billion to almost 8 billion in 2022, and is projected to grow further and then stabilise between 8.9 billion and 12.4 billion by the end of the 21st Century (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs 2022). Global food production (crops, livestock, fish) has largely been able to keep up with population increase through intensification of production by more than doubling the area equipped for irrigation, increasing the proportion of irrigated land from ~10 to the current 25%, increasing the use of fertilisers and pesticides, genetic improvement of crops, livestock and fish, and other improvements in farming technology (Pellegrini and Fernández 2018). However, this increased production has resulted in multiple impacts on the environment in the form of loss of forests, wetlands and natural grassland, decline and loss of species populations, increased sedimentation, acidification and eutrophication, and greenhouse-gas (GHG) emissions (Foley et al. 2005; Clark and Tilman 2017).

Awareness of the link between wetland decline and agricultural development is increasing, and agricultural development is consistently identified as one of the main drivers (Zedler 2003; Wood and van Halsema 2008; Verhoeven and Setter 2010; Asselen et al. 2013; Robertson et al. 2022). The conversion of wetlands to agriculture in the 20th Century was concentrated in a number of regional hotspots (particularly Europe, United States, Central Asia, India, China, Japan and South-east Asia) as a result of population growth and economic development (Fluet-Chouinard et al. 2023). In some of these regions, growing awareness of the importance of wetlands during the past 30–50 years, including for climate-change adaptation and mitigation, has now led to protection and conservation policies (e.g. the Clean Water Act in the USA; or the EU Water Framework Directive in Europe) and to ecological restoration efforts and the promotion of nature-based solutions (Gann et al. 2019; Seddon et al. 2020). In large parts of Africa and southern Asia, continued population growth can be expected until the next century (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs 2022), which is likely to be accompanied by increasing pressure on aquatic resources, including wetlands (Falkenmark et al. 2007). Research and implementation of ecological restoration show wide regional variation (e.g. Ballari et al. 2020; Jiang et al. 2023). For countries that still have many intact wetlands, wise use of wetlands, allowing for sustainable economic and agricultural development while protecting and conserving the ecological character of wetlands (Finlayson et al. 2011), appears a more sustainable approach than first losing wetlands and their ecosystem services to economic development and then investing in restoration to salvage them (which is what happened in many high-income countries; Simaika et al. 2021; Fluet-Chouinard et al. 2023).

The impacts of agriculture occur on two levels (Wood and van Halsema 2008). The most visible impacts are direct, by draining wetlands and converting wetland vegetation to crops. For example, 11–15% of peatlands are estimated to have been drained globally, largely for cropping, plantations or livestock (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations 2020a). But wetlands can also be affected indirectly, when agricultural activities upstream of wetlands (e.g. water abstraction for irrigation, or fertiliser and pesticide applications) alter the flows of water, nutrients and species to wetlands. With both types of impact, the ecological and hydrological functions of wetlands in landscapes are affected, with consequences for water, sediment and nutrient cycles and water quality, habitats and biodiversity, and for ecosystem services and human health and well-being (Finlayson et al. 2005; Wood and van Halsema 2008; Horwitz and Finlayson 2011; Ramsar Convention 2011; Gardner and Finlayson 2018).

Not all agriculture–wetland interactions are negative, and wetlands under certain conditions can also support agriculture, for example, with their soil moisture (Roberts 1988) or as a source of irrigation water (Rijsberman and De Silva 2006; Everard and Wood 2018). Many wetlands are part of fertile floodplains in open wooded landscapes with good water availability and favourable conditions for crop or livestock production. Other wetlands are less suitable for agriculture, such as those with peat soils that are mostly acidic and non-fertile, or with vegetation that would be directly affected by agricultural use. With appropriate engineering (including drainage of flooded soils and flood regulation), conditions for wetland agriculture can be optimised for agricultural productivity, although often at the expense of other wetland ecosystem services and biodiversity (Falkenmark et al. 2007).

The Ramsar Convention on Wetlands has developed studies and guidance on wetlands and agriculture to support Contracting Parties in reducing the negative effects of food production on wetlands. However, it was difficult to achieve effective policy responses, partly because of the multitude of drivers in agriculture–wetland interactions, but also because farms and farmers are part of wider food systems (Finlayson et al. 2024). Because there are many wetland and agricultural system types, with many, and sometimes complex, connections, general knowledge of the impacts of agriculture on wetlands is not sufficient for effective protection and sustainable management of wetlands. Interactions should be understood not only at the local wetland scale but also at the wider catchment scale and in terms of the social–economic and institutional context of wetlands. Therefore, recognising the diversity in production systems and their interactions with both the landscape (including wetlands) and the socio-economic and institutional context is important if more effective policy responses for sustainable agriculture and wetlands are to be achieved. This is related to where agricultural systems are located (altitude, latitude) vis-á-vis wetland types, and to the resource use (e.g. land, water, fertilisers, pesticides) and emissions (water discharge, solid wastes, or gaseous exchanges with the atmosphere) of different production systems. Besides farm-system types, the way in which farms are operated is also important. Whereas some systems are inherently more efficient in resource use, differences in farming practices can also lead to different impacts on wetlands. The need to analyse wetland–agriculture interactions, and the importance of placing wetland management planning in the context of the river basin or catchment has been recognised for some time (Wood and van Halsema 2008; Ramsar Convention 2010a; Finlayson et al. 2024).

The overall objective of this paper, therefore, is to review the interactions of different food production systems and wetland types, and to explore the impact of a transition to more sustainable food production on wetland ecosystems. We do this specifically by (1) summarising the different wetland types, their areas and functions in the landscape, (2) defining the world’s predominant food production systems and characterising their resource use, (3) analysing the direct drivers of change in wetlands created by these production systems, and their interactions with different types of wetlands, both at local and at catchment scale, (4) reviewing the indirect drivers for wetlands in the context of food production and food systems, and (5) suggesting pathways for a transition to more sustainable agriculture–wetland interactions. A more differentiated analysis is required for both wetland and agriculture audiences in support of their efforts to reduce the environmental impacts of food production and slow down the trend of wetland loss and degradation.

Methods

We address these objectives through a narrative literature review to introduce the complexity of agriculture in wetlands through illustrative descriptions of the interactions between agricultural systems and wetland types emerging from the cross-tabulation described below. This provides an overview of the interactions rather than an analytical assessment of the extent of the research or its quality. The latter was not addressed in this investigation and would require a systematic review with predefined criteria that could be derived from the illustrative descriptions provided here. The cross-tabulation was developed from an existing summary of wetland types and a categorisation of farm systems, as described below.

For the summary of wetland types and their functions (Objective 1), recent scientific reviews were consulted, particularly papers considering agriculture in wetlands from the encyclopaedic-like Wetland Book and chapters therein (Finlayson et al. 2018a, 2018b), the first Global Wetland Outlook (Gardner and Finlayson 2018), and background papers reviewed for Ramsar Convention Briefing Note Number 13 on wetlands and agriculture (Robertson et al. 2022). For wetland types, we used the Ramsar classification, which defines 42 types of wetland in the following three broad categories: inland wetlands (20 types), coastal-marine wetlands (12 types) and human-made wetlands (10 types) (Ramsar Convention 2010b).

The categorisation of farm systems (Objective 2) made use of existing classifications (Tivy 1990; Dixon et al. 2001; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations 2011a, 2016, 2018a, 2018b; Harrington and Tow 2011; Mateo-Sagasta et al. 2018; Lewandowski 2018), which used different attributes to characterise farming systems, including water availability, climate, altitude, farm size, production intensity, dominant livelihood source, and location (e.g. forest-based, coastal). This led to categorisations for developing countries (Dixon et al. 2001) and for rainfed systems worldwide (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations 2011a; Harrington and Tow 2011). Our current categorisation allows for a global analysis of interactions of farming with different types of wetlands. The main cross-cutting criteria were as follows: (i) product category: crop, livestock or fish; (ii) resource use and intensity, especially in terms of water and nutrients, because this determines to a large extent the direct interactions between agriculture and wetlands; and (iii) landscape factors, related to climate zones and geographical location (latitude, altitude).

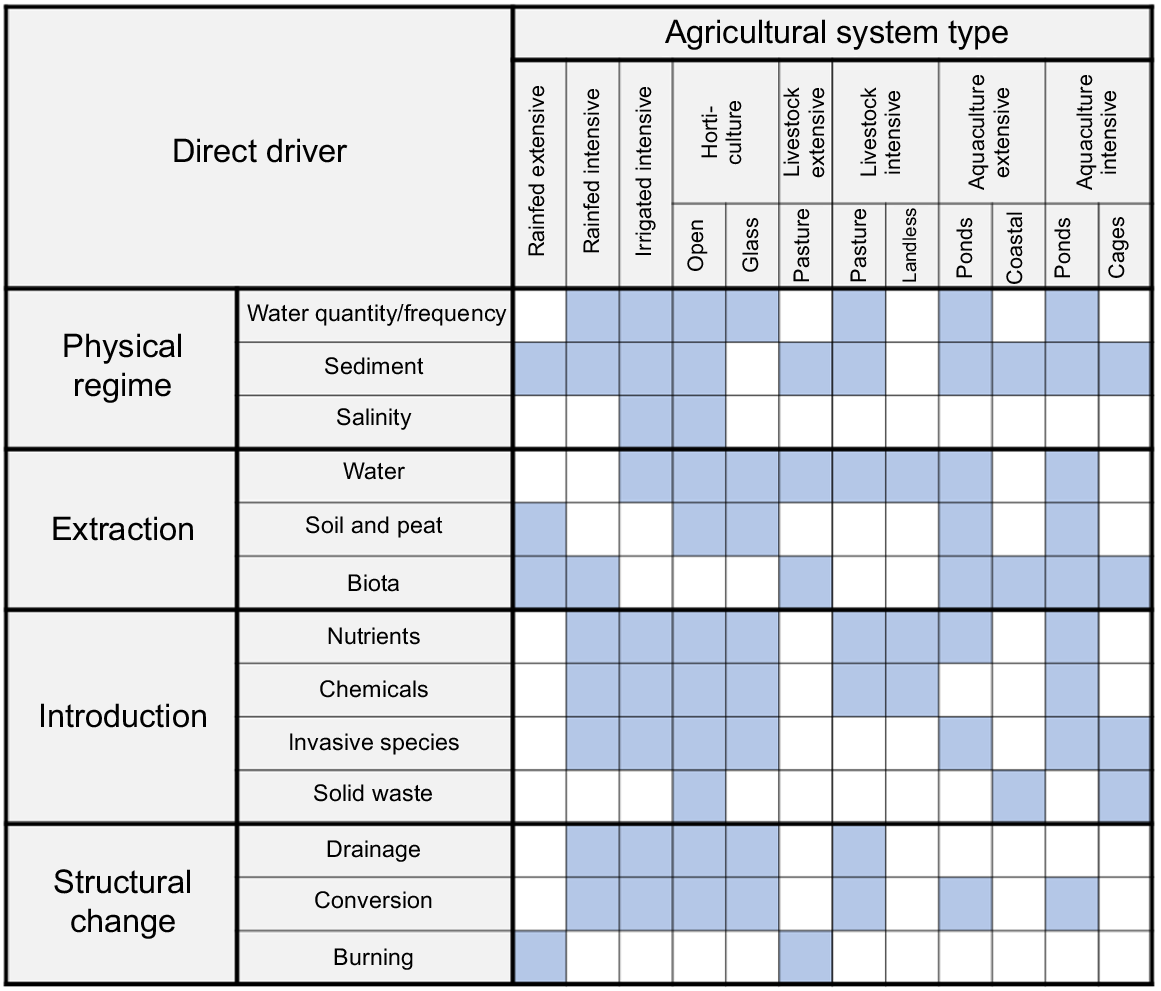

For analysing the direct drivers of change originating from food production (Objective 3), we focused on the negative change in wetlands resulting from agricultural land-use change and activities. Direct drivers are natural or human-induced causes of biophysical changes at local to regional scales (Asselen et al. 2013). The Global Wetland Outlook defined the following four types of direct drivers of change: (i) structural-change drivers, that alter wetlands and their immediate environment through permanent changes to the geomorphology, hydrology or vegetation (e.g. drainage, conversion, burning or removal of wetland vegetation); (ii) physical regime drivers: factors the conditions and pattern of variation of which are altered by humans, related to changes in inflow quantity and frequency, sediment load, salinity and temperature; (iii) extraction drivers, which change wetlands by partial or complete removal of ecosystem components, such as water, species, and soil or peat; (iv) introduction drivers: addition of nutrients (fertilisers), chemicals (pesticides), invasive species, or solid waste; or atmospheric deposition (Gardner and Finlayson 2018; van Dam et al. 2023). Agriculture causes change to wetlands in all of these four categories. The impacts of different agricultural systems on wetland types and water and nutrient flows were reported in relation to these driver categories, with examples of specific wetland and agricultural systems around the world.

For a better understanding of the indirect drivers related to food production (Objective 4), we look at wetlands and agricultural systems in the context of food systems. Indirect drivers are the broader, more diffuse mechanisms and processes that influence the direct agricultural drivers of wetland change (Alcamo et al. 2003; Gardner and Finlayson 2018). They are related to the demographic, socio-economic, institutional and cultural processes that influence the decision-making of all actors. Food systems comprise not only agricultural production but all activities from food production to food consumption (including processing, packaging, distribution and retailing), as well as the outcomes in terms of food security, environmental security and social welfare (Ericksen 2008; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations 2018c). The various public and private actors in food systems, and their role in decision-making on both the production and demand sides of food production, were considered in relation to wetlands. Also, the role of governance and institutions, and the policy instruments that are used to influence decision-making were considered at scales ranging from the farm to national governments and international bodies.

To explore pathways to more sustainability (Objective 5), we use the results from the first four objectives to discuss the implications for wetlands of the principles for sustainable agriculture presented by the FAO (Soto et al. 2008; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations 2018c). This allowed us to identify potential synergies or tensions between a transition to more sustainable agriculture, and the need to reverse the on-going degradation and destruction of wetlands.

Wetland area, types and importance at global and landscape levels

The most recent estimates show that the total area of wetlands in the world is between 15.2 × 106 and 16.2 × 106 km2, or some 10% of the global land surface (Davidson and Finlayson 2018, 2019). Inland wetlands, coastal-marine wetlands, and human-made wetlands make up ~80, 10, and 10% of the world’s wetlands respectively (Davidson and Finlayson 2018, 2019). The most recent area estimate for marine and coastal wetlands is 1.42 × 106 km2, whereas inland wetlands occupy 11.79 × 106–12.79 × 106 km2 (Davidson and Finlayson 2018, 2019). Within inland wetlands, marshes and swamps on alluvial soils (river floodplains), and natural lakes together form ~50% of the area. Peatlands form over 33% of inland wetlands (Davidson and Finlayson 2018). Data on the extent of human-made wetlands (e.g. reservoirs, ponds, rice paddies, constructed wetlands) are incomplete, the global area for which data exist is 1.80 × 106 km2 (Davidson and Finlayson 2018). When discussing the interactions between agriculture and wetlands, human-made wetlands have a special position because some of them, such as rice fields and aquaculture ponds, are wetlands and agricultural systems at the same time. Some loss and degradation of natural wetlands is caused by conversion to agricultural or aquacultural use, and represents a gain in human-made wetlands (Davidson 2014).

A distinguishing feature of wetlands is their water source, namely, rain, surface water, or groundwater. Isolated wetlands are fed by rainwater or groundwater and are not connected to a stream, river or coastal system. Floodplain wetlands are fed by surface flows and floods, in addition to rainfall and possible groundwater input (Bullock and Acreman 2003; Acreman and Holden 2013), whereas coastal wetlands are influenced by estuarine and marine hydrosystems. Wetlands modify the flows of water and nutrients and the movement and productivity of plants and animals in the landscape. The nature and extent of this modification are determined by the type of wetland and its location in the catchment. The processes underlying these roles are jointly referred to as the functions of wetlands, and are the biophysical basis for their ecosystem services (Finlayson et al. 2005; Díaz et al. 2015; Gardner and Finlayson 2018). Wetland functions can be classified into hydrological, biogeochemical, and ecological functions (Maltby 2009; de Groot et al. 2010).

The hydrological functions include floodwater detention, groundwater recharge and discharge, and sediment retention. The flow of sediment and nutrients is determined to a large extent by hydrological pathways in catchments or coastal environments. Rainfall can run off the surface or infiltrate into the soil, where water can move vertically from the earth surface to the base rock, and laterally from hillslopes to streams and rivers. The extent to which wetlands slow down or store water, recharge or discharge aquifers, or retain or export sediment depends on their location in the catchment, the geomorphology and topography of the landscape, and the seasonal variations in rainfall. Floodplain wetlands generally reduce or delay floods, but headwater wetlands can either decrease or increase flood peaks. Wetlands evaporate more water than forests, grasslands and arable lands, and as a result wetlands often reduce flow to downstream rivers in dry periods (Bullock and Acreman 2003; Burt and Pinay 2005; Lohse et al. 2009; Acreman and Holden 2013; Guo et al. 2018; Hu and Li 2018).

The biogeochemical functions include nutrient retention and export, carbon retention, trace element storage and export, and organic carbon concentration control through processes such as sedimentation of particulate matter, uptake and storage of nutrients in vegetation, and microbial processes. Nutrients can enter the wetland system through surface or subsurface inflow or through aerial deposition, and leave by streamflow or release to the atmosphere. Nutrients can also be stored in vegetation biomass or by adsorption to soil particles. Surface flows carry sediment, nutrients adsorbed to sediment particles, and dissolved nutrients. Detachment and transport of soil and sediment particles are caused by water erosion (the physical force of surface runoff) but can also be caused by wind or ice and by human activities such as soil tillage (Montgomery 2007; Labrière et al. 2015). Subsurface flows transport dissolved compounds, including nutrients, metals, and dissolved organic compounds. As water passes through wetlands, residence time often increases and biological processes increasingly influence the composition of the water (Burt and Pinay 2005; Lohse et al. 2009; Pärn et al. 2012). These processes are controlled by the oxygen content of the sediment and by vegetation processes, and are influenced by the degree of water-logging, the hydraulic retention time, and hydraulic loading.

Large amounts of carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus are stored in wetland vegetation and soils, particularly in wetlands with organic soils, where flooded conditions prevent rapid aerobic decomposition of organic matter. Stored nutrients can be released when conditions change, for example, when accumulated sediment is flushed out of the system by peak flows, or when wetlands are drained and soil organic matter starts decomposing. Peat wetlands, mangroves, saltmarshes and seagrass beds store the largest part of the world’s soil carbon (in coastal wetlands, now often referred to as ‘blue carbon’), and anthropogenic disturbance (e.g. from agriculture) and climate change contribute to accelerated release of this carbon to the atmosphere (McClain et al. 2003; Fisher and Acreman 2004; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations 2014; Johnson et al. 2018; Were et al. 2019). Dissolved organic C and N, and the inorganic forms of nitrogen (NO3, NO2, NH4) can all be transported in surface and subsurface flows, and ~25% of N inputs into catchments are exported by streams, regardless of catchment size and land use (Howarth et al. 1996; Vitousek et al. 1997; Galloway et al. 2004; Durand et al. 2011). Denitrification is another important natural N export pathway from catchments, and floodplain wetlands with available NO3 and anaerobic, flooded conditions are an important location for denitrification (Piña-Ochoa and Álvarez-Cobelas 2006; van Cleemput et al. 2007).

The ecological functions of wetlands include ecosystem maintenance, providing habitat to a wide range of species, and foodweb support (Maltby 2009; De Groot et al. 2010; Gardner and Finlayson 2018). Wetlands are among the most biologically productive ecosystems, and wetland plants and animals are important for the cycling and storage of nutrients. Streams and wetlands provide connectivity in catchments, which is of crucial importance for the dispersal of species and the natural maintenance of network populations (United States Environmental Protection Agency 2015; Boudell 2018; Cosentino and Schooley 2018). Many plant seeds are transported by wind or by animals such as birds and fish. Dispersal by water is important for plant propagules, fish and macroinvertebrates, but less important for aquatic plant seeds (mostly produced out of water) and freshwater insects (usually emerge from the water and fly to other streams). In coastal and marine environments, aquatic habitats are more continuous and it is mostly the larval stages that disperse. Wetlands are also important for migratory birds, amphibians and reptiles and their movement between reproduction habitats and non-breeding habitats where they forage and become adults (Begon et al. 1996; Horn et al. 2011; Rittenhouse and Peterman 2018).

Classification of agricultural production systems and farms

Food production can be realised by cultivating crops or animals, or by capturing them from wild populations. Most current definitions of agriculture and ‘agrifeed systems’ include forestry and capture fisheries, both inland and marine (Campanhola and Pandey 2019); however, here we focus on the interactions of crop, livestock and fish cultivation with wetlands and exclude terrestrial forestry and capture fisheries from the current analysis, while recognising the importance of conducting a similar analysis for these sectors (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations 2020b; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and United Nations Environmental Programme 2020). Agricultural production is then defined as any form of fish or livestock rearing, cultivation of crops or a combination of these for the production of food, feed or fibre (Lewandowski 2018). It is realised in a wide variety of cultivation and husbandry systems, and is an important component of food security policies (although food security is a much broader concept, which, besides food production, also encompasses the physical and economic access to food and its nutritional quality; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations 1996). Agriculture also includes the production of biomass for energetic or material use (Lewandowski 2018). The occurrence of agricultural systems across the globe depends on the biophysical characteristics of different earth regions (climate and landscape), as well as cultural, socio-economic and other factors. The diversity of agro-ecological environments is shaped by rainfall patterns, water availability and soil quality, topography, and temperature. Agricultural systems evolved in the environment in which they are practised, and are continuously developing (Tow et al. 2011).

The global categorisation we developed is based mostly on product category (crop, livestock or fish), and on resource use and intensity. The criterium of landscape factors was considered in a number of the system types. The eight farming-system categories are (Table 1) as follows: crop systems, both rainfed and irrigated, on a scale from extensive to intensive (including horticulture); livestock systems; and aquaculture systems, all from extensive to intensive (see more detailed description in the sections ‘Description of the eight farming system types, and of integrated systems’ and ‘Diagrams showing the hydrological pathways in a catchment and the impacts of different food production systems on water and nutrient flows’ of the Supplementary material).

| Agricultural system | Water use | Fertiliser use | Nutrient efficiency | Chemical use | Potential erosion | Agricultural diversity | Impact on biodiversity | Position in landscape | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a) Extensive rainfed | Low, mainly for livestock | Low–medium, also organic | Medium–high in good practice | Low–medium | Low–medium | Medium–high | Low–medium | Close to high productive and arid areas | |

| b) Intensive rainfed | Low–medium, processing of harvest, livestock | Medium–high | Medium–high, depends on practice | High | High | Low | High | Mainly temperate, lowlands | |

| c) Intensive irrigated | High, irrigation and processing of harvest | High | Often high | High | High | Low | High | Arid areas, basins, lowlands | |

| d) Horticulture | High | High | High | High | Low–medium | Low–medium | Medium | Areas with good water access, high productive regions | |

| e) Extensive livestock | Low | Low indirect (fodder) | High (because of low input) | Low or indirect | Low–medium | Usually high | Low | Arid areas, mountain regions, only pastures feasible | |

| f) Intensive livestock | High (also through feed or fodder) | High indirect (feed or fodder) | Low–high, depends on practice | High indirect (fodder) | High–low, indoor | Low | High | Lowlands with good water availability | |

| g) Extensive aquaculture | Low | Low | Medium–high | Low | Low | Low | Low–medium | Areas with good freshwater access; coastal areas | |

| h) Intensive aquaculture | Low–high (depends on system) | High, also indirect (feed) | Low–high, depends on practice or system | Medium | Low | Low | High | Areas with good freshwater access and terrain for ponds; coastal areas |

Water use refers to ‘blue’ water use (water sourced from e.g. rivers, lakes, wetlands or groundwater); does not refer to ‘green water’, which comes from rainfall and soil moisture.

Besides farming systems, it is important to also consider the farms themselves because they represent the lowest scale-level at which decisions related to crops, livestock, resource use (land, water, inputs, labour) and farming practices are made, directly influencing the possible impacts of farming on wetlands. A farm or agricultural holding is the ‘economic unit of agricultural production under single management comprising all livestock kept and all land used wholly or partly for agricultural production purposes’ (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations 1999, section 3.1.1 The holding). The management can be exercised by an individual or household, or by a clan or tribe, or by a corporation, cooperative or government agency. Within the same agroecological environment, the production and impacts of different farms can vary according to a combination of the objectives, knowledge and norms (the farming style) of individual farmers (van der Ploeg 2012). Farms can be dedicated to one type of farming system, or can incorporate combinations of different systems. The total number of farms in the world was estimated to be ~600 million; smallholder farms of <2 ha in size comprise more than 80% of these, but cover only 12% of the world’s farmland (Lowder et al. 2016). These ~500 million small farms support the livelihoods of almost 2 billion people and produce some 80% of the food in Sub-Sarahan Africa and parts of Asia (International Fund for Agricultural Development 2021). The largest 1% of farms operate more than 70% of the world’s farmland, and more than half of the world’s farmland is operated by farms that are 100 ha or larger. However, there are strong regional differences; most farms (70–80%) in eastern and southern Asia, the Pacific, and Sub-Saharan Africa are small and cover 30–40% of the farmland, whereas in high-income countries small farms cover less than 10% of the farmland (Lowder et al. 2016; Anseeuw and Baldinelli 2020). On ~90% of the farms, labour is provided predominantly by members of one family. The other 10% of the farms, operating ~25% of all the farmland globally, are held by corporations or other organisations (e.g. cooperatives, government or religious organisations; Lowder et al. 2016). In most low-income countries, farm size is decreasing, with increasing numbers of smallholders, indigenous peoples, rural women, youth and landless rural communities depending on increasingly fragmented land; in high-income countries farm land is consolidated into larger farms (Anseeuw and Baldinelli 2020). This land inequality is the result of a combination of rural population size, available farm land, economic development, and the power relations and institutions that govern land access and ownership. Because of trends in population and economic development, the total number of farms in all world regions is expected to decline during the 21st Century (Mehrabi 2023).

Direct drivers of wetland modification originating from agriculture

Structural-change drivers

The most common agricultural system types that lead to structural conversion of wetlands are rainfed agriculture, irrigated systems and horticulture. For cropping, structural conversion consists mainly of drainage, either subsurface drainage using pipes or surface drainage by ditches and canals, and removal of the original wetland vegetation to plant crops. Subsurface drainage has often been part of agricultural development, for example, in North America (Zedler 2003). Drainage reduces the water table and soil moisture, aerates the soil and makes it more suitable for cultivation. Subsurface drainage generally increases the total water flow from fields, but reduces surface runoff of sediment, phosphorus and adsorbed materials on sloping terrains. Nitrate is very soluble and is transported well in drainage flows, much better than are compounds with higher sorption capacity (e.g. phosphate, ammonium, organic nitrogen). The latter are retained better on clay or organic soils than on sandy or loamy soils. Cracked soils or road drains can cause completely different effects through preferential flow paths (Gramlich et al. 2018). The effects on aquatic ecosystems of agricultural drainage are direct loss or alteration of habitats (loss of connectivity, fragmentation, structure and function of wetland vegetation), effects on water quality, and effects on the hydrology (Blann et al. 2009).

Drainage and vegetation removal can be seasonal and, if they do not interfere permanently with the hydrology of the wetlands, may allow wetlands to flood again and vegetation to recover during parts of the year (Behn et al. 2024). This is common in African floodplains where traditional seasonal flood-recession farming depends strongly on rainfall, for example, in Cameroon (Akei and Babila 2022) or in Ghana (Sidibé et al. 2016). Near Lake Victoria, East Africa, papyrus wetlands are converted to farming during dry conditions and re-flood during the rainy season (Kipkemboi et al. 2007; Beuel et al. 2016; Ondiek et al. 2020). Wetlands that are drained and converted to intensive rainfed farms are lost permanently, for example, in the upper Namatala wetland in Uganda, where years of wetland farming have broken the lateral connectivity between river and floodplain (Namaalwa et al. 2013, 2020); and in other parts of Africa where large-scale commercial farms have appropriated wetlands (Kronenburg García et al. 2022). Extensive areas of New Zealand have also been lost as a result of permanent conversion (Robertson et al. 2019). Irrigation systems are often located in permanently converted floodplains, for example, in Asia for lowland rice cultivation in floodplains (Gopal 2013). Many small-scale cereal and vegetable farms in Africa and Asia are located in or near rural or urban wetlands (e.g. Haq et al. 2004; Rebelo et al. 2010; Sakané et al. 2013; Hettiarachchi et al. 2015). In northern Europe and North America, peat extraction for use as a growth medium in horticulture leads to permanent conversion of wetlands (Clarke and Rieley 2010). More permanent structural change is caused by filling in or conversion of isolated wetlands in upland plains (e.g. wheat or maize farming in the prairie pothole region of the USA and Canada) or conversion of floodplain or delta wetlands (e.g. cereal and potato farming in western Europe). In the five upper Midwest states of the USA, 42–89% of wetlands were lost during the past two and a half centuries (Zedler 2003).

In principle, extensive livestock systems do not cause conversion of wetlands; however, with increasing stocking densities, drainage and removal of vegetation can occur. Burning of vegetation is used widely by pastoralists to improve the quality of forage for livestock or wildlife, leading to loss of volatile substances to the atmosphere, deposition of ash (which can alter soil pH), exposure of the soil to solar radiation, and increased availability of nutrients (Kotze 2013). Under more intensive management, the original vegetation may be replaced by forage grasses and fertilisation may be applied. In the Zoige wetland on the Tibetan Plateau, the traditional communal watering places did not interfere with the hydrology of the basin; land reform led to privatisation of the land, fencing and draining of the wetlands, and digging of wells, which caused a drop in the water table (Yan and Wu 2005). High livestock densities can also lead to trampling and soil compaction, which increases runoff and the potential for erosion, and reduces infiltration resulting in a lower groundwater table and negative effects on vegetation. Stock density also increases the intensity of grazing, which affects the structure and composition of the vegetation and, ultimately, can reduce vegetation cover (United States Department of Agriculture and Natural Resources Conservation Service 2003). Intensively managed pasture involves seeding of forage grass and legumes, which means replacement of the original vegetation. Where water logging occurs, drainage is applied. In the Netherlands, where large areas of drained peatlands are used for intensive dairy farming, subsidence caused by low water tables and peat oxidation occur. Landless livestock systems do not create structural change in wetlands, unless they are constructed on converted wetlands, but indirectly can contribute to structural change if converted wetlands are used for the production of feed ingredients such as soybeans and cereals (Barona et al. 2010; Nepstad et al. 2014).

Construction of aquaculture ponds in natural wetlands leads to habitat modification and loss. Generally, surface water is diverted from streams or rivers by gravity and water can also be pumped from wells. Ponds can be constructed in valley bottoms, by damming of headwater streams, in floodplain areas close to streams and rivers, or in deltas and coastal plains. For marine fish and shrimp, ponds are also constructed in mangroves or in reclaimed mudflats in tidal zones. Pond construction in mangroves led to loss of mangroves in South-east Asia and northern South America in the 1990s. Approximately half of the mangrove area in the Philippines was converted to ponds between 1951 and 1988 (Primavera 2006). In Indonesia, Brazil, India, Bangladesh, China, Thailand, Vietnam and Ecuador 51.9% of the mangrove forest area was lost between 1970 (pre-shrimp) and 2004, and commercial aquaculture accounted for 28% of total mangrove loss (Hamilton 2013). Sometimes agricultural land is converted to shrimp ponds (Ilman et al. 2016; Jayanthi et al. 2018). The impact of pond construction on wetlands depends strongly on the scale of development. One or a few small ponds integrated with a farm will not create a big impact, but large-scale development or construction of hundreds of ponds in a floodplain strongly influences the hydrological and ecological functioning of the landscape.

The physical structure of coastal culture systems (fish pens or cages, poles, lines, rafts, anchor blocks) can degrade nearshore seagrass beds and sediment communities. Floating cages or pen systems for the culture of predominantly finfish (although other species can also be grown in cages) can be located in surface water of sufficient depth, depending on the size of the structure. Small-scale cage operations with a few cubic metres of cage volume can be located in a small lake, river, or in the coastal zone, whereas large-scale cage farms operate cage systems that are up to 30 m wide and 10 m deep and can cover large surface areas in lakes, reservoirs, or large rivers, coastal bays, lagoons, and subtidal areas. Cage farms can also be located in the open sea or ocean, but are then technically (when in waters of >6 m deep, because of the Ramsar definition) not in a wetland. Coastal mollusc (mostly bivalves) and aquatic plant (mostly seaweed) aquaculture are practised in shallow coastal water, including coastal lagoons and intertidal and subtidal zones of estuaries. Molluscs can be grown on the bottom, in sheltered beds where the densities can be managed, or on ropes spiraled around poles or suspended from rafts or from floating long lines (Simenstad and Fresh 1995; McKindsey et al. 2011). Seaweeds are grown tied to lines that can be suspended from poles or from floating lines (Zhang L et al. 2022). Coastal aquaculture influences the ecosystem by changing material flows (e.g. by taking up nutrients and converting them into biomass and waste products; or when the structures are colonised by species other than the cultured species) and through disturbances from the culture activities such as seeding, maintenance, or harvesting (Dumbauld et al. 2009; Spillias et al. 2023). Unregulated development of cage aquaculture, mollusc farms or seaweed farms can block the acces to other coastal resources (e.g. for coastal fishing communities) or create navigational hazards. In some places, structural materials are obtained by harvesting from natural wetlands (e.g. from mangroves; Primavera 2006).

Physical regime drivers

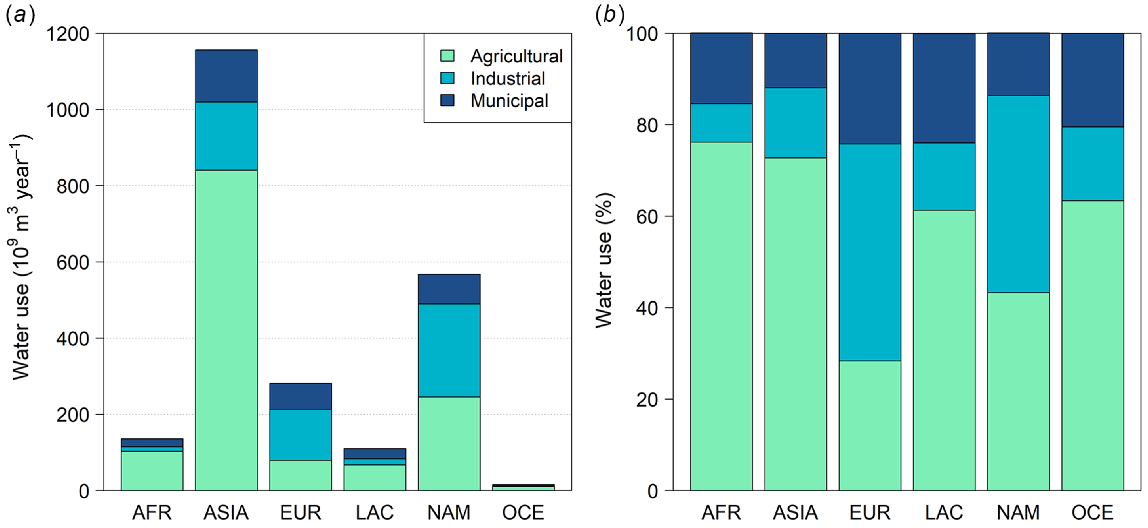

Physical regime changes for wetlands through diversion of water and sediment flows are particularly observed in areas with rainfed and irrigated systems (including horticulture). The connectivity and heterogeneity of wetlands are determined to a large extent by water flows, hydroperiod and water level and are seriously affected by fragmentation of the river and stream network (Fuller et al. 2015; Larkin 2018; Rasmussen et al. 2018; Middleton 2018; Rittenhouse and Peterman 2018). Regulation and construction of dams and reservoirs, interbasin diversion and water abstraction has affected 71% of the larger rivers in North America, Europe and the post-Soviet states (Nilsson et al. 2005; Lehner et al. 2011; Palmer et al. 2008; Hanna et al. 2018), with profound impacts on the ecological character of streams, rivers, floodplains, lakes, isolated wetlands and coastal ecosystems. Agriculture represents ~70% of global freshwater use and agriculture withdrawals continue to increase. Agricultural use ranges from 28 to 76% of total water withdrawals in different regions (Fig. 1). Livestock production accounts for ~8% of global human water use, mostly through the consumption of feed crops for intensive systems (Schlink et al. 2010). In large areas of Asia, northern Africa, Australia and the Americas, agriculture intensification drives high water stress with consequences for people and wetlands (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations 2019).

Agricultural, industrial and municipal use by world region for 2013–2018, (a) as total use and (b) as a percentage of total use. Data source: AQUASTAT (see https://www.fao.org/aquastat/en/databases/maindatabase, accessed 3 March 2021). AFR, Africa; EUR, Europe; LAC, Latin America and Caribbean; NAM, Northern America; OCE, Oceania.

Changes in water flows and levels affect soil and biota directly. River regulation leads to a reduction in transition zones between aquatic and terrestrial zones, loss of surface water connectivity, and reduction of hydrological connectivity between river and floodplain to groundwater pathways, which affects isolated wetlands. Headwaters are affected most by the construction of dams, whereas lowland zones are damaged more by floodplain reclamation, channelisation and construction of barriers for navigation. This influences migration of aquatic organisms, both for species preferring flowing water and stillwater (Buijse et al. 2005; Opperman et al. 2009; Tockner et al. 2010). Changes in soil moisture and inundation patterns drive changes in vegetation composition, sometimes providing opportunity for invasive species with far-reaching consequences for other plant and animal groups in the trophic network (Middleton and Kleinebecker 2012). Fish, macroinvertebrates, and amphibians are vulnerable to changes in flow (Maddock et al. 2013; Allen et al. 2020). Fish habitats for feeding and reproduction are degraded, and fish migration (e.g. upstream for spawning, and downstream for eggs and larvae) is obstructed (Pusey and Arthington 2003; Dugan et al. 2010), which also leads to significant impacts on fisheries production both in inland and coastal and estuarine systems (Gillson 2011). Changes in water flow also change the supply of mineral and organic sediment to wetlands (Galbraith et al. 2005). Changes in freshwater supply cause changes in tidal ranges and velocities in coastal wetlands, affecting erosion and saltwater migration that determine species composition and succession (Teal 2018; Tiner 2018), including the spawning area of diadromous fish species. Groundwater pumping in coastal areas can lead to land subsidence and an increased risk of flooding and saline intrusion, for example, in the Mekong Delta in Vietnam, where subsidence amounts to 1–2 cm annually (Minderhoud et al. 2017). With climate change, changes in freshwater and sediment supply are often combined with changes in sea level, for example, in mangroves, where both landward and seaward extension can be the result (Asbridge et al. 2016).

In many crop systems, land preparation and farm practices lead to an increase in water and tillage erosion. Erosion is also possible from open-field horticulture, but is less from greenhouses, especially when crops are grown on trays and in artificial substrates. Sediment is supplied to wetlands through wind or water erosion, including natural bank erosion in streams and rivers. Erosion reaches peak values during periods of high rainfall and discharge or during intensive agricultural activity such as land preparation or harvesting (Labrière et al. 2015), as demonstrated in wetlands converted to rice cultivation in Uganda (Namaalwa et al. 2020) and Rwanda (Uwimana et al. 2018a, 2018b). In the Amazon region in Brazil, conversion of forest to pasture and soy farming can have indirect effects on wetlands through increases in erosion (Barona et al. 2010; Nepstad et al. 2014). In rangelands, erosion can stay undetected initially as it starts slowly, but then advances exponentially as the combination of soil compaction, reduced vegetation, increased runoff, exposure of the soil, enhanced decomposition of soil organic matter and the loss of fine soil particles all reinforce each other. After reaching a critical point, soil erosion cannot be reversed by reducing stocking densities but only by active restoration (United States Department of Agriculture and Natural Resources Conservation Service 2003).

Erosion affects both inland and coastal wetlands. In streams and rivers, floodplains, lakes and forested wetlands, erosion upstream leads to water quality degradation and eutrophication (Allan 2004; Finlayson et al. 2005), but also to siltation in reservoirs (Schleiss et al. 2016). Excessive addition of sediment changes lake character through modification of lake shore habitats, infilling or increased turbidity. In Lake Tana, Ethiopia, the delta of the Gumara River expanded by 5 ha annually between 1984 and 2014 as a result of agriculture and settlements in the Gumara catchment, leading to increasing sediment concentrations in the river (Abate et al. 2017). Sensitive coastal wetlands such as seagrass beds and coral reefs are also affected by erosion (Fabricius 2005; Wenger et al. 2015). Shallow marine waters, seagrass beds and kelp forests can be substantially degraded by excessive sediment from storm-event erosion (Rabalais et al. 2010; United Nations Environment Programme 2014).

Salinisation is caused by the accumulation of soluble salts. Agricultural drainage water can have elevated salt concentrations as it flushes out minerals from soils. Intensive water abstraction for irrigation can cause elevated water table of saline or brackish groundwater, and, in combination with high evaporation rates, lead to salinisation of inland wetlands in arid and semi-arid regions (Gell and Reid 2014; Herbert et al. 2015). Similarly, surface or groundwater abstractions for irrigation in coastal wetlands can lead to intrusion of salt surface or groundwater (European Environment Agency 2009; Herbert et al. 2015; White and Kaplan 2017). Salinity changes can alter the ecological character of wetlands by changing the composition of microbial communities and their biogeochemical processes, and by influencing the solubility of gases and redox potential of soils and the osmotic regulation of organisms. This affects phosphorus adsorption, denitrification and other ecological functions. Prolonged salinisation can lead to replacement of freshwater by salt-tolerant or brackish communities (Herbert et al. 2015; Zhou et al. 2017) and contamination of water supplies used for agriculture or human consumption.

Dam construction for aquaculture ponds in natural catchments, especially when it replaces valley bottom or floodplain wetlands, has multiple impacts on the surface and subsurface flows of water, with implications for the functioning of streams, water and sediment retention, particulate organic matter production (e.g. from phytoplankton), water chemistry, and migration of aquatic species. Although these are generally seen as negative, in agricultural catchments dams and fishponds can serve as traps of sediment and suspended matter, and have a positive effect on nutrient retention (Four et al. 2017; Uwimana et al. 2018b). The physical structures of coastal aquaculture can modify current regimes, which affects a number of ecosystem processes, including reduced exchange rates and increased sedimentation (Dumbauld et al. 2009).

Introduction drivers

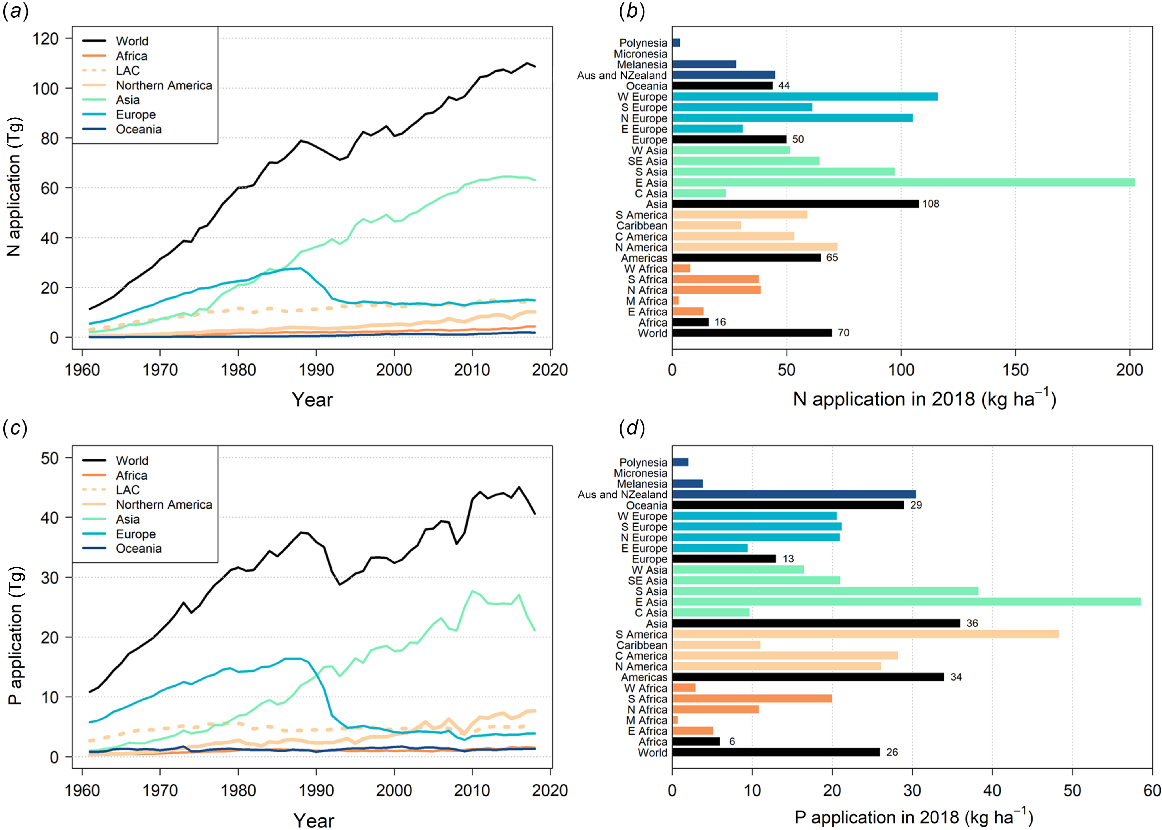

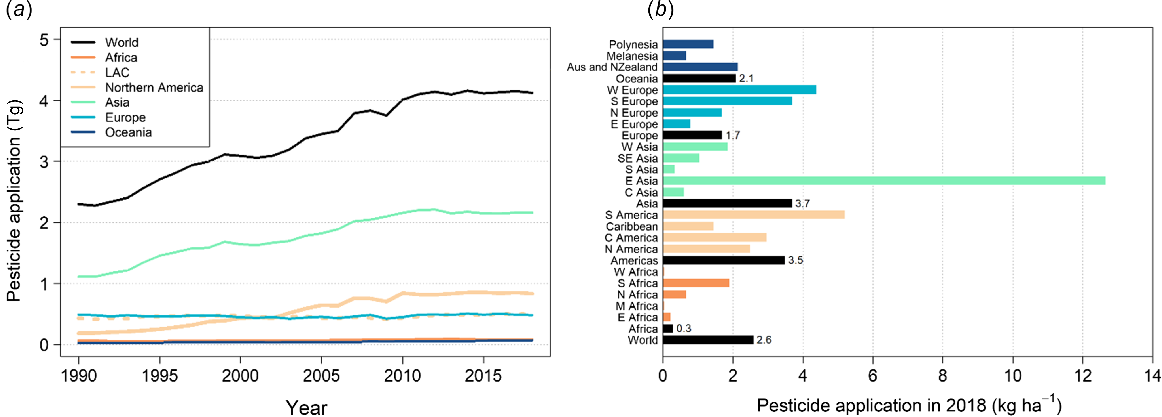

Globally, the application of nitrogen and phosphorus fertilisers and pesticides have increased since the 1960, but there are strong regional differences both in terms of total use and in application rates per hectare (Fig. 2, 3). These applications, together with fossil fuel burning, have led to enormous losses (of up to 200 Tg year−1) of reactive nitrogen (Galloway et al. 2021). In total, 80% of the N used for food production ends up in the environment before consumption, contributing strongly to biodiversity loss (United Nations Environment Programme 2019). In the European Union, 80% of all reactive nitrogen emissions to the environment are from agriculture (Westhoek et al. 2015). Although some farming systems, particularly extensive farms and small-scale subsistence systems have no or only low levels of chemical inputs (fertilisers, pesticides), other forms of more intensive agriculture with higher input levels result in more leaching of nutrients and chemicals and contamination of surface- and groundwater. Horticultural systems and especially greenhouses are often associated with releases of nutrient-enriched waters and leaching of pesticides, but much depends on the way these systems are operated (Bergstrand 2010). Open systems discard the nutrient solutions used, but increasingly closed recirculating systems are used that collect and recycle the nutrient solution to the crops (although groundwater contamination remains a risk if systems are not completely closed).

(a) Total nitrogen (N) application by world region between 1990 and 2018; (b) total N application rate (kg ha−1) by world regions and subregions in 2018; (c) total phosphorus (P) application by world region between 1990 and 2018; and (d) total P application rate (kg ha−1) by world regions and subregions in 2018. Data source: FAOSTAT (see http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data, accessed 21 February 2021).

(a) Total pesticide application (insecticides, herbicides and fungicides) by world region between 1990 and 2018; (b) total pesticide application rate (kg ha−1) by world regions and subregions in 2018. Data source: FAOSTAT (see http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data, accessed 21 February 2021).

In extensive livestock systems, manure is returned to the landscape; however, because this is produced from fodder growing in the same system, it does not represent a nutrient import on a catchment scale. Locally, the concentration of livestock at watering places can create accumulation of nutrients and organic matter, leading to water-quality problems and eutrophication (Malan et al. 2018) and the risk of microbial contamination (Khaleel et al. 1980; Bicudo and Goyal 2003; Garzio-Hadzick et al. 2010). Intensive pasture requires fertilisation to produce enough forage. Manure and fertiliser applications lead to nutrient surpluses in intensive dairy farms. In Australia and New Zealand, median annual losses of N were 27 kg ha−1 (range 3–153) and of P 1.6 kg ha−1 (range 0.3–69), depending on landscape conditions and management (McDowell et al. 2017). Generally, intensification of livestock systems and the de-coupling of livestock and crop systems lead to increasing loads of nutrient on the environment, including nitrate leaching to groundwater (Menzi et al. 2010; Sahoo et al. 2016). Intensive landless systems (pigs, poultry, cattle) are independent of landscape or climate features, and depend more on the vicinity of input and consumer markets, and the availability of transporting and processing infrastructure. For pigs and poultry, they are often indoor systems. Feedlots or feed yards are intensive operations in which animals (often beef cattle) are kept in enclosures in high densities and fed high-protein diets consisting of forage, grains, minerals and supplements. Manure produced in feedlot systems is often recycled to the fields used to produce the feed, sometimes mixed with bedding material (straw, or other products). Because of concentrated manure production, intensive livestock systems can cause eutrophication problems in surface water, including contributing to eutrophication of coastal wetlands. Leaching of nutrients (especially nitrate) to groundwater is widely reported (Sahoo et al. 2016).

Semi-intensive and intensive aquaculture ponds need nutrient inputs in the form of manure, fertilisers or feed, but a large part of the non-assimilated nutrients accumulate in the pond sediments (Hargreaves 1998) and are released at the end of the culture period. Intensive tank systems do not have natural sediments and release all of their nutrient wastes with the discharge water if no wastewater treatment is applied. Fish cages discharge waste feed, metabolites of the fish (mainly ammonium) and fish faeces into the water of the bay or lake. Nutrients and organic loading can become problematic when the carrying capacity of the ecosystem is exceeded or when cages are not properly sited. In Bolinao Bay in the Philippines, algal blooms and fish kills were observed as a result of the high density of milkfish aquaculture cages (1170 units) that far exceeded the planned number (544 units; Geček and Legović 2010). Expansion of cage culture is also observed in lakes in Africa, for example, Lake Volta in Ghana (Asmah et al. 2014).

In coastal aquaculture, biodeposition from cultured molluscs and other organisms on the structures increases the organic loading, and therefore influences the oxygen concentrations, pH, and redox potential of the sediment. It can also affect benthic respiration and nutrient fluxes, and benthic infaunal communities. Because of the limited use of external inputs, seaweed and mollusc culture in coastal systems hardly increase the nutrient concentrations of the water. Mollusc culture can reduce nutrient concentrations even to the point where phytoplankton productivity is reduced, sometimes to levels that affect other parts of the ecosystem (McKindsey et al. 2011).

Catchment studies have demonstrated the impact of agricultural land use on the export of nutrients from catchments. In the Gjern River basin in Denmark, 76 and 51% of the N and P export respectively, were from agricultural areas in the basin. After restoration of riparian zones and a lake, N and P retention increased because of permanent N removal through increased denitrification and increased P removal through sedimentation in the floodplains (Kronvang et al. 1999). Dissolved nutrients, especially nitrate, can infiltrate and leach to the groundwater. P binds more strongly to sediment particles and is more likely to be transported in surface runoff. Nutrient export is also related strongly to discharge. Drainage of prairie pothole wetlands in Canada and the USA led to increased loads of nutrients and organic matter to downstream areas (Brunet and Westbrook 2012). Nitrate export in the catchment of Chesapeake Bay (USA) was related strongly to the baseflow, whereas organic N export was more related to surface runoff and P export was related to the concentration of suspended solids (Jordan et al. 1997). The results of nutrient export and increases in nutrient concentrations in lakes and coastal areas are well known, including excessive growth of phytoplankton and macrophytes, loss of oxygen, dead zones, fish kills, loss of biodiversity, loss of aquatic plant beds and coral reefs (Turner and Rabalais 1991; Carpenter et al. 1998; Goolsby et al. 2000; Rabalais et al. 2002; Magner et al. 2004).

Fertiliser and manure use also lead to nitrogen (N) emissions to the atmosphere, which return to the surface of the earth, including wetlands, through deposition as nitrous oxides or ammonia (Hristov et al. 2011). Atmospheric ammonia concentrations are significantly elevated over the world’s major agricultural areas, particularly in North America, western Europe, southern Asia and eastern Asia (Warner et al. 2017). Wet atmospheric N deposition in China was significantly correlated with chemical-fertiliser use (Zhu et al. 2016). N lost through ammonia volatilisation from synthetic fertilisers and animal manure can be as high as 18 and 26% respectively (Bouwman et al. 2002). Application of effluents and slurries from intensive livestock systems, and composting of manure also lead to ammonia volatilisation (Saggar et al. 2004). The effects of N deposition on wetlands can include a direct toxicity effect, accumulation of N in the ecosystem, longer-term effects of reduced forms, acidification of soil, and increased susceptibility to changes in environmental conditions or diseases (Bobbink et al. 2010). In upland catchments, high N deposition often leads to leaching of nitrate to surface waters. High loads can exceed the natural absorption capacity of Sphagnum mosses, resulting in leaching through the moss layer and increased availability of N to vascular plants (Fritz et al. 2012). Decomposition of organic matter increases with N inputs by reducing the natural N limitation on microbial decomposition processes (Bragazza et al. 2006; Song et al. 2013). High deposition in lakes in Europe and the USA shifted phytoplankton growth from N to P limitation (Bergström and Jansson 2006; Elser et al. 2009; Crowley et al. 2012) and led to elevated denitrification and N2O emissions (McCrackin and Elser 2010). N deposition in coastal waters leads to harmful algal blooms, for example in the South Yellow Sea and East China Sea (Liu et al. 2011).

Pesticide loads from agricultural land have an impact on aquatic systems and have increased substantially since the 1960s, particularly in Asia (Fig. 3). However, the actual impact on wetlands depends on many factors such as the chemical used and its persistence, sorption to soil particles, topography and climate conditions, and distance to the wetland. In catchments of the Great Barrier Reef (GBR) in Australia, the use of pesticides for sugarcane and cereals is common. In the GBR water, insecticides are rarely detected but herbicides were present (Thorburn et al. 2013). In wetlands and floodplains of the Mississippi river (USA), a range of pesticide residues were detected (e.g. Cooper et al. 2003; Evelsizer and Skopec 2018; Callicott and Hooper-Bùi 2019). Horticulture is responsible for a disproportionate share of the global pesticide consumption. The production of fruits and vegetables accounts for 26–28% of total pesticide use. In the USA, fruit and vegetable production uses 2% of the agricultural land, but 14% of total pesticide consumption (Weinberger and Lumpkin 2007). In the Netherlands, pesticide use on cropland generally was ~7 kg ha−1 in 2008, but much higher in the culture of ornamental plants (up to ~100 kg ha−1; CBS Statline 2014). In Thailand, the largest amounts of pesticides were applied in intensive vegetable culture, with up to 43 kg of active ingredient per hectare (Schreinemachers et al. 2012). In a horticultural area near Shenzhen City in China, pesticide application rates (mostly organophosphate insecticides) were 300 kg ha−1 (Zhang X-N et al. 2015). Surface water in catchments with horticultural land use often contains pesticides and degradation products of pesticides (e.g. Jansen and Harmsen 2011; Wightwick et al. 2012). Often, concentrations do not exceed water-quality standards, but persistent pesticides (e.g. HCH (hexachlorocyclohexane) and DDT) that were banned years ago are also found (Zhang et al. 2015).

In intensive livestock systems and aquaculture, the use of veterinary pharmaceuticals is common. Antibiotics, antiparasitic drugs and steroidal hormones are the most widely used. Introduction to the environment happens mostly through the treatment of farm animals and fish, inappropriate disposal of used containers or unused medicine, and in the production process, and leads to intoxication or mortality, or to development of resistance to antibiotics or disturbance of hormonal functions (endocrine disruptors). Excessive use of antibiotics in aquaculture has led to antibiotic resistance in bacteria from fish and shrimp ponds. Detection of pesticides and antibiotics in consumer products has occasionally led to public health concerns (Primavera 2006). Generally, more knowledge on the environmental impact of veterinary pharmaceuticals is needed, especially on the combined effects of several compounds (Bártíková et al. 2016). Some substances may affect the microbial composition of soils, inhibit soil bacterial growth, reduce the hyphal length in active moulds, or affect sulfate reduction in soils and inhibit the decomposition of organic matter (Boxall et al. 2003).

Fish escapes from aquaculture systems to the environment happen, but are a bigger risk in cage than in pond aquaculture. Genetic introgression of farmed fish in wild populations and effects of parasites and viral diseases on wild populations are hazards related to cage farming. Research on salmon farming in Norway and on sea bass and sea bream farming in the Mediterranean showed that the risk of nutrient and organic loading was low, but the impacts of introgression in wild populations and parasites and diseases needed more research (Arechavala-Lopez et al. 2013; Taranger et al. 2015). Although seaweed farming generally does not introduce nutrients into the system, it has introduced non-native species but its role in the spread of invasive seaweed species is not clear (Eggertsen and Halling 2021; Spillias et al. 2023). Mollusc culture can also be a source of introduction of exotic species (McKindsey et al. 2007).

Extraction drivers

Extraction of vegetation, fish or other biota from wetlands is common in extensive farming systems where farm households are often engaged in diverse livelihoods activities. Vegetation can be used as fodder to feed animals, but also for a wide range of other purposes, including mulching, construction, household utensils, handicrafts, furniture and others (Wood et al. 2013; Biggs et al. 2015). Supplemental irrigation with water from wetlands is applied to rainfed crops to improve yields when rainfall does not provide sufficient moisture, and can improve crop yield and water productivity. With increasing drought episodes in recent years, supplemental irrigation with groundwater or surface water may have impacts on downstream wetlands (Nangia and Oweis 2016).

The extraction of peat for use as a growth medium, mostly as potting soil for container culture or as an amendment for lawn and garden soils, represents a direct impact of horticulture on peat wetlands. Most popular is the incompletely decomposed peat of Sphagnum sp. (white peat), but other types such as sedge peat (Blievernicht et al. 2011; Apodaca 2013) are also used. Peat is uniquely suitable for this because of its ability to retain water, air and plant nutrients, its low pH and the option to mix it with special-purpose growth media (Amha et al. 2010). The main regions for horticultural peat extraction are northern Europe (~80% of global production) and North America (Canada and USA, with ~5% of production). On a global scale, ~2000 km2 of peatlands are used for extracting horticultural peat (Clarke and Rieley 2010). The effects of peat extraction include damage to wildlife habitats, destruction of the hydrological properties of the bogs, a reduction of the carbon storage function, and the release of the carbon contained in the peat (Alexander et al. 2008; Kern et al. 2017; Leifeld et al. 2019). The demand for peat substrates in horticulture is still increasing. Efforts to reduce its use include less destructive extraction methods, the search for alternative materials, the designation of peat wetlands as protected areas, and raising awareness among actors about the values of intact peat wetlands (Waddington et al. 2009; Verhagen et al. 2013). Non-decomposed Sphagnum farmed on re-wetted degraded peat bogs (Gaudig et al. 2014) or on artificial floating mats (Blievernicht et al. 2011) may be a promising alternative.

Wetland vegetation is used widely as natural fodder in extensive pastoral farming. Many different types of wetland can occur in rangelands, including isolated depressional wetlands, permafrost peat wetlands and alpine wetlands in cold-climate zones, streams and rivers and their riparian zones, or sand rivers with mainly subsurface flow. Ecosystem services of rangeland wetlands can include capturing surface runoff, storing water, groundwater recharge and discharge, sediment retention and improvement of water quality of runoff to streams and rivers, denitrification, and serving as habitat and nursery for plants and animals, production of hay and native plant seeds, livestock production, hunting and fishing, bird watching, and recreation (e.g. canoeing or kayaking; Carter Johnson 2019). Some of the rangeland areas are among the most species-rich areas of the world (Alkemade et al. 2013). Many small-scale dairy farms are located in upland areas where they can affect headwater wetlands. Where livestock herding intensifies, the natural rangeland vegetation may be removed and replaced by managed pasture, and water may be extracted from surface or groundwater for drinking water or for pasture irrigation in dry periods. Generally, intensive pasture systems for feeding dairy cattle are in areas that are less suitable for other crops. In the temperate regions of the world, these are often river or coastal floodplains with a high water table. However, there are also many small-scale dairy farms in upland areas. In many places, wetlands support livelihoods related to livestock, for example, in the Sudd wetlands of South Sudan, where most of the wetland communities combine livestock with other livelihood activities such as small-scale farming, fishing and hunting (Ojok 1996; Rebelo et al. 2012).

For aquaculture species for which hatchery reproduction methods are not available, juveniles for stocking ponds, cages or shellfish farms must be obtained from wild catch. For example, in Bangladesh there is a seasonal fishery for eggs of the Indian major carps in Halda River, which are then traded to pond operators for growout (Alam et al. 2013). For the cultivation of eel species (Anguilla sp.), glass eels are caught and traded internationally. Because of the decline in stocks, trade in the European eel (Anguilla anguilla) is now prohibited under CITES (Kaifu et al. 2019). For most freshwater species, and increasingly for marine species, hatchery techniques for artificial reproduction are available.

Wetland types and functions affected by agricultural systems

By juxtaposing the different wetland types and agricultural systems, the impacts of agriculture on wetlands can be unpacked. A differentiated analysis results from looking at the impact on wetlands of the direct drivers of change originating from the various agricultural systems (Fig. 4). All types of farming create some impact on wetlands, but intensive farming systems (intensive crop and livestock systems, including horticulture) have, unsurprisingly, the strongest and broadest impact through their water and soil management, and the application of nutrients (fertiliser), chemicals (pesticides) and sometimes invasive species. For extensive systems, impacts on soil, vegetation and other biota are important but fertiliser and pesticide applications are generally lower. Most inland wetland types are affected by agriculture, either directly (by wetland conversion) or indirectly through modification of water, sediment, and nutrient flows of catchments. Coastal wetlands are affected by nutrients, sediments and pollution carried by rivers and runoff, by groundwater pumping (which can lead to subsidence and salinisation) and by structural changes and introductions from coastal aquaculture.

Indirect agricultural drivers of wetland modification

Within food systems, agricultural products are components of value chains that comprise the steps through which a product goes from production, processing, delivery to consumers, and disposal of waste products (Kindervater et al. 2018). The development from traditional to modern food systems usually comes with replacement of small, diverse farms by larger monoculture farms, with short local supply chains becoming longer (sometimes global), and with change from societies with under-nutrition to the prevalence of dietary diseases and obesity (Ericksen 2008). Since 1970, the global food system has shown a growth in agricultural productivity through technological innovation, globalisation of markets and trade, and increasing awareness of the environmental implications of food production (Brooks and Place 2019). Besides farmers, a range of other actors in the value chains and food systems play a role in determining what and how farms produce food and other products (Table 2). Farmers, agribusiness companies, and financial institutions are active primarily with the production of agricultural products and the necessary inputs. Consumers, and food-processing and retail companies determine the demand for food and the product markets. Finally, governments and non-governmental organisations play a moderating role in the governance of food systems.

| Actor | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| Farmers and producers | More than 80% of farms globally is 2 ha or smaller, but occupy only 12% of farmed land. More than half of global farmland is with farms of >100 ha. | |

| Agribusiness companies | Produce agricultural chemicals, fertilisers, seeds and farm machinery. Dominated by three multinational megacompanies who control 70% of the industry. | |

| Financial institutions | Commercial banks, private and institutional investors, international and agricultural development banks, insurance companies, cooperatives, credit unions. | |

| Consumers | Depending on income, buying from local (super) markets, restaurants. Sometimes organise to advocate for food safety or other issues. | |

| Food processing and retail companies | Limited number of multinational food and beverage corporations responsible for processing and retailing food. Two-thirds of global food trade consists of processed products. | |

| Knowledge and research institutions | Universities and national and international (agricultural) research institutes. | |

| National governments | Organized in policy sectors (agriculture, energy, environment etc.). Uses policy and economic instruments to implement policies. | |

| Multilateral–international agencies and NGOs | Includes e.g. UN organisations (e.g. Food and Agricultural Organization), environmental agreements (including Ramsar Convention), international cooperation and development community, but also international trade agreements such as World Trade Organization. |

On the production side, the indirect drivers are related to the decision-making of farmers about the choice of crops or livestock, the farming system and technologies applied and the use of resources and inputs, and include economic and social factors, socio-cultural beliefs and norms, and the institutional environment. The decisions of farmers and farming households are strongly related to how they perceive the natural environment (including climate) and the available resources, the economic risk involved and the institutional support they can expect, but also to the perception of their own role as farmers and how they adapt to change (McGuire et al. 2013; Singh et al. 2016; Emerton and Snyder 2018). In low- and middle-income countries, many small-scale farmers produce at subsistence level or for local markets. With increasing production for markets, farmers can invest in intensification of production through more inputs (e.g. fertilisers, pest control), better genetic material (e.g. improved seeds) and technology (irrigation, mechanisation). To achieve this, sufficient natural resources (land with good soil quality and sufficient water) and an enabling environment (e.g. credit, extension services) are also needed.

Other important actors for food production are the agri-business companies that provide agricultural inputs (chemicals, fertilisers, seeds) and farm machinery to farmers. In recent years, several global-level mergers have resulted in consolidation, with three trans-national megacompanies now controlling some 70% of the agrochemical industry and over 60% of commercial seeds. These companies also dominate the research, spending the equivalent of 75% of all private sector research in this sector (Fuglie et al. 2011). This raises concerns about the lack of competition, companies claiming patents and ownership of gene traits and germplasm, and research defending existing positions in chemical-intensive agriculture and genetic engineering, rather than exploring innovations that are better for consumers and the environment (Howard 2009). The large agrobusiness companies also spend millions on lobbying programs, for example, with law makers in the USA and in Europe (Elsheikh and Ayazi 2018). The large countries with developing agricultural sectors such as Brazil, India and China have been the growth markets for agribusiness companies in recent years (Phillips 2020).

Land ownership and tenure are strong determinants of the enabling environment for food production. Tenure types range from formal statutory forms, where the state owns the land, to cooperative or customary land tenure where land is owned by local or indigenous communities who manage the land according to their customs and traditions. Changes from traditional land tenure, in which wetlands are often managed as common pool resources, to private ownership, can lead to unsustainable use (Adger and Luttrell 2000). Furthermore, many small farm households do not have secure tenure, which influences the decision-making about sustainable farm practices and land management (United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification 2017). In some parts of the world, local communities that managed the (wet)lands under a communal or customary arrangement are displaced by powerful outsiders who are allowed to buy land (‘land grabbing’; see e.g. Kronenburg García et al. 2022). Other elements of the enabling environment include extension support for farmers, and credit facilities or subsidies that allow farmers to obtain loans for investing in good-quality inputs and farm mechanisation (Teng and Oliveros 2016; Thierfelder et al. 2018; Terlau et al. 2019). Natural resource management and wetland ecosystem services are often gendered, with men and women having unequal access to land and ecosystems, not benefitting equally from them, or suffering different impacts when ecosystem services are lost, or experiencing different outcomes when interventions based on ecosystem services are developed and implemented (Radel and Coppock 2013; Fortnam et al. 2019).

On the demand side, consumers determine the demand for food items and the products derived from these. However, consumer demand is influenced strongly by the food processing and retail industries. The global food and beverage industry is worth more than 10% of the world’s GDP, and is also dominated by a small number of large transnational corporations. Similarly, the retail industry is dominated by three to five companies that control more than half (often 75% or more) of the market (Burch et al. 2013). These large and powerful companies influence markets and price levels, consumption patterns (e.g. through advertising of processed foods) and production standards and methods. Increasingly, they impose private production standards, which can have negative effects on small producers who struggle to comply (Richards et al. 2013). Because of liberalisation in foreign direct investment, supermarkets have also increased their market share in low- and middle-income countries, resulting at times in competition with traditional retailers and exclusion of small local suppliers (Reardon and Hopkins 2006; Swinnen and Vandeplas 2010). Demand is also determined by dietary patterns, which have changed during the 20th Century as a result of economic development and urbanisation, from largely home or artesanal food preparation using unprocessed ingredients to a situation with two-thirds of the food trade consisting of processed products (Moubarac et al. 2014; Brooks and Place 2019). Convenience foods gradually displace long-established traditional foods and dietary patterns that were presumably more healthy; this happens increasingly also in low- and middle-income countries, where the growing urban population and rising incomes lead to an increase in consumption of animal products and refined carbohydrates (Monteiro and Cannon 2012; Stuckler et al. 2012; Monteiro et al. 2013; Tilman and Clark 2014).

The formal governance of food systems is the remit of national governments who have traditionally dealt with food security and safety, economic development and environmental policy. Governments can influence the decision-making of actors in the following three ways: by using economic instruments to intervene in markets; by setting rules (laws and regulation); and by influencing the awareness and attitude of actors (e.g. using education and communication, or by stimulating stakeholder participation) (ten Brink and Russi 2018; ten Brink et al. 2018). In most government systems food and environment are confined to separate policies and implementing agencies. National agricultural policies aim at food security, and government interventions often focus on protecting consumers by correcting failures of the market that lead to unwanted price fluctuations or food shortages (Peterson 2009). Market failures are also targeted by environmental policies, where the lack of monetary valuation of, for example, wetland benefits leads to disregarding these benefits in decision-making.