Introduction of the UroShield® in district nursing: a case study

Emma Rose Watson A *A

Abstract

This case study reviews a Quality Improvement (QI) project where the UroShield® device was introduced to patients with an indwelling urinary catheter (IUC) within a District Nursing Service (DNS) in New Zealand. Patients with IUCs often require more frequent interventions to maintain patency; however, best-practice guidelines state to avoid disruption to the sterile closed system as much as possible. The primary aim for the QI project was to improve patients’ quality of life (QoL) via reducing frequency of catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs); reducing blockages and leakage; and improving overall comfort of the catheter, resulting in less catheter-related interventions. Secondary aims were to reduce costs to the service and organisation due to the use of less consumables; reduction in acute and planned nursing home visits for catheter management; reduction in the use of antibiotic therapy and risk of antibiotic-resistant colonisation; and removal of the financial burden of frequent General Practitioner (GP) appointments and prescription fees. The case study reviewed a small cohort of five patients who commenced UroShield® with analysis from 5 months pre- and post- UroShield® showing positive primary and secondary outcomes. There was an improvement in CAUTI and reduced prevalence of blockages, less nursing time required which positively impacted on the workload of the service, which in turn, led to cost savings for the organisation. The key recommendation arising from the QI project within the DNS, is that UroShield® be adopted as an option for appropriate IUC patients. A further randomised controlled trial is needed to examine the specific impact on QoL for patients within the cohort.

Keywords: biofilm management, blockage of IUC, CAUTI, complications of IUC, district nursing catheter management, long-term urinary catheter, UroShield, UTI prevention.

Introduction

This case study documents the introduction of the UroShield® to a small group of patients receiving care for management of their long-term indwelling urinary catheter (IUC) (urethral and suprapubic) within a District Nursing Service (DNS). This case study summarises the impact UroShield® may have on problematic long-term urinary catheters, and evaluates any ongoing benefits for patients, the DNS, and the entire organisation.

Health New Zealand MidCentral’s DNS provides comprehensive specialist community nursing across the entire region; approximately 8912 km2, with a population of 188,830.1 The service is available 7 days a week, 08:00–23:00 hours, with registered nurses and enrolled nurses providing home-based or clinic-based care. The main District Nurse (DN) hub is in Palmerston North, with six outlying centres across the region.

Management of long-term IUCs makes up 34–37% of the workload for the MidCentral DNS. Each patient with an IUC has an individualised plan of care around the management regime for their catheters – this ranges from weekly to twelve weekly changes, with routine bladder irrigations introduced as deemed appropriate by the visiting DN. A study amongst community nursing services in the United Kingdom (UK) discovered that 20% of unscheduled visits were catheter-related; 72% of which were blocked or leaking IUCs.2 Each intervention requires DN time (including travel), consumables, sterile equipment, and ongoing supply deliveries. Any after-hours call outs add to the day-to-day cost to the service, with potential trips to the Emergency Department (ED) and admission to hospital for urosepsis all adding to the burden to the organisation. Extra callouts for catheter-related complications cause frustration for the patients; such as having to wait for the nurse, or cancel plans, as well as an added pressure on nurses with already high workloads.3

It is estimated that 30–50% of long-term catheter patients suffer from blockages, making it one of the most common complications affecting quality of life (QoL).4–6 In 2023, MidCentral DNS introduced UroShield® as a quality improvement (QI) project, to reduce the burden of complications and unscheduled care for patients and the service/organisation. UroShield® clips onto the IUC and produces surface acoustic waves which prevents microbial attachment within the catheter lumen. This case study will examine the incidence of catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI) and blockage while UroShield® is in situ and determine any potential enhancement to QoL for patients. The case study will also assess any reduction to the burden on the DNS and organisation as a whole; including reduction of workload and urgent callouts, reduced resource use and prevention of CAUTIs requiring primary health care input or hospital assessment/admission.

Background

In New Zealand (NZ) currently, there is no national reporting for CAUTI or other complications of IUC, and no tracking of long-term IUC use. NZ is one of the few developed countries in the world without a comprehensive national healthcare-associated infection (HAI) surveillance system. In the United Kingdom (UK) and some states in the United States of America (USA) it is mandated by law.7 In 2021, the first national Point of Prevalence Survey (PPS) for all HAI was conducted, which determined urinary tract infections (UTIs) made up 19% of HAIs detected in the 24-h period of the survey. Forty-nine percent of these had an IUC within the 7 days prior.8 There is no data available around financial cost of CAUTI within NZ. From this PPS, the NZ Health Quality and Safety Commission have set the goal to reduce all HAIs from medical devices, including commitment to develop a programme around IUC management.8

IUCs are one of the most frequently used invasive clinical devices globally3 with significant costs associated.4 It is estimated that every case of CAUTI in the USA costs approximately US$600, equating to a total of US$131 million cost burden annually.9 Modelling from the National Health Service (NHS) in the UK estimates an annual CAUTI rate of 52,085 nationally, costing UK£27.7 million.10 CAUTI have one of the highest prevalence of HAI worldwide, with the risk increasing the longer the IUC remains in place.11,12 A lack of robust evidence has led to conflicting recommendations in international guidelines, with no clear consensus on managing long-term IUCs or preventing complications.13–15 Until the recent publication of new evidence-based guidelines from the European Association of Urological Nurses (EAUN),16 there were no specific best practice recommendations for the day-to-day management of IUCs. The UK National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines were the only catheter management guidelines available, although they focused on infection prevention. These guidelines determine that avoiding interruption to the closed drainage system is the most effective CAUTI prevention method.17 ‘Breaking the seal’ is a term coined to describe disruption of the sterile closed-drainage system, which unavoidably increases the risk of bacterial invasion.18

Within hours of an IUC being inserted, microorganisms begin to attach to the catheter’s surface and build a protective matrix known as biofilm.3,19,20 Biofilm creates a microcolony of bacteria within the catheter which is shielded from the body’s innate immune response and is resistant to the force of urine flow to dislodge it.18,21,22 The most frequent bacteria isolated in urine from IUCs is Proteus mirabilis – a urease producing bacteria that leads to raised pH of the urine which in turns causes crystallisations to develop and adhere to the surface of the catheter.3,19 As the crystallisations build up, blockages occur which further increases CAUTI risk if improperly managed and can cause life-threatening situations amongst certain patient populations.23 Autonomic dysreflexia is a life-threatening episode of sudden hypertension, experienced by people with spinal injuries above the T6 level. It is the result of noxious stimuli below the level of the injury, with around 85% being related to infection, bladder distention or blocked IUCs.24,25 Untreated CAUTIs can lead to urosepsis, which has a high mortality rate of around 10%.9

The European Association of Urology (EAU) recommends antibiotic therapy as the first line treatment for any CAUTI that are symptomatic.26 Misdiagnosis of asymptomatic CAUTI from the detection of normal bacteriuria within IUCs, has led to an overuse of antibiotics and an increasing prevalence of antibiotic resistant pathogens.27,28 Antibiotic resistance has become a global concern associated with prolonged hospital stays, higher mortality and increased financial burden.28,29 A study found that 23% of hospital-acquired sepsis cases, were due to UTIs; mostly from patients with IUCs.30 The most effective method of reducing antibiotic resistant pathogens, is removing the need for antibiotic use.28

Eradication of established biofilm is complex, and various attempts to overcome it have been developed.20,21 Table 1 provides a summary of existing CAUTI prevention methods.

| Products currently available | Summary of literature found | References | Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coated catheters – antimicrobials, polymers, antibiotics | Developed to prevent adhesion and colonisation. Variable effectiveness. Silver proving the most effective, but not statistically significant. | 9,22,31,32 | ||

| Pre-connect system – BARD | All-in-one pre-connected catheter and drainage bag to minimise bacterial entry to the catheter lumen after insertion. 30 day ‘sit time’ which avoids disruption of the sterile closed system. No action on biofilm formation. No benefit if insertion technique is poor – UTIs still occurred. | 33,34 |

| |

| Pre-packed bladder instillation solutions | Chlorhexidine – antiseptic solution for prevention of bacterial growth Mandelic acid – for prevention of urease-production

Suby-G and Solution R – citric acid – for dissolving encrustations that cause blockage. | 9,15,18,35,36 |

|

UroShield® in district nursing

The UroShield® is proven to have good efficacy from multiple international clinical trials,21,31,37,38 with NICE developing a guidance document for its use.39 The Surface Acoustic Waves (SAW) produced by UroShield® prevent biofilm formation within the catheter lumen, preventing bacterial attachment. In turn, this reduces incidence of CAUTI and blockage, relieving many of the associated complications.21,31,38 It is an external device that clips around the catheter after insertion, making it fully non-invasive, without need to disrupt the sterile closed system as per best practice recommendations. UroShield® has not been adopted for routine IUC care within NZ, as far as the author is aware.

In 2023, a quality improvement (QI) project was conducted within MidCentral DNS, to introduce UroShield® within usual practice. UroShield® is not intended to be used on all patients with IUCs, only those experiencing frequent complications. For a patient to be appropriate for UroShield®, DNS decided on the following requirements: patients to be experiencing UTIs and/or blockages bimonthly; evidence of excess debris; and a regular regime of bladder irrigations in between catheter changes. For patient safety, patients must be cognitively aware and able to understand the instructions around management of UroShield®, be independent or have appropriate caregiver availability and not be a falls risk.

Five patients involved in this project were used for this case study, with written consent obtained for examination of clinical interventions before and after use of the device.

Results/Analysis

Patient outcomes

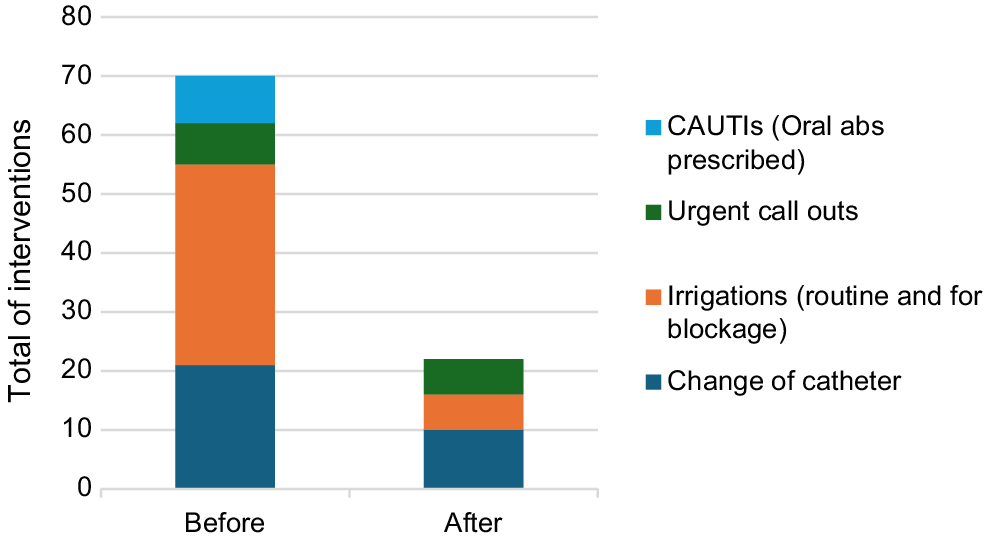

Fig. 1 shows incidence of UTI and blockage and any resulting interventions in the periods before and after use of UroShield®. The clinical findings show significant improvement in the number of interventions required for all five patients, with only one UTI amongst the group.

There were two catheter related hospital admissions in the pre-UroShield® period, resulting in a total of 5 days total in hospital; there were none during the 5 months of use.

Nursing/service outcomes

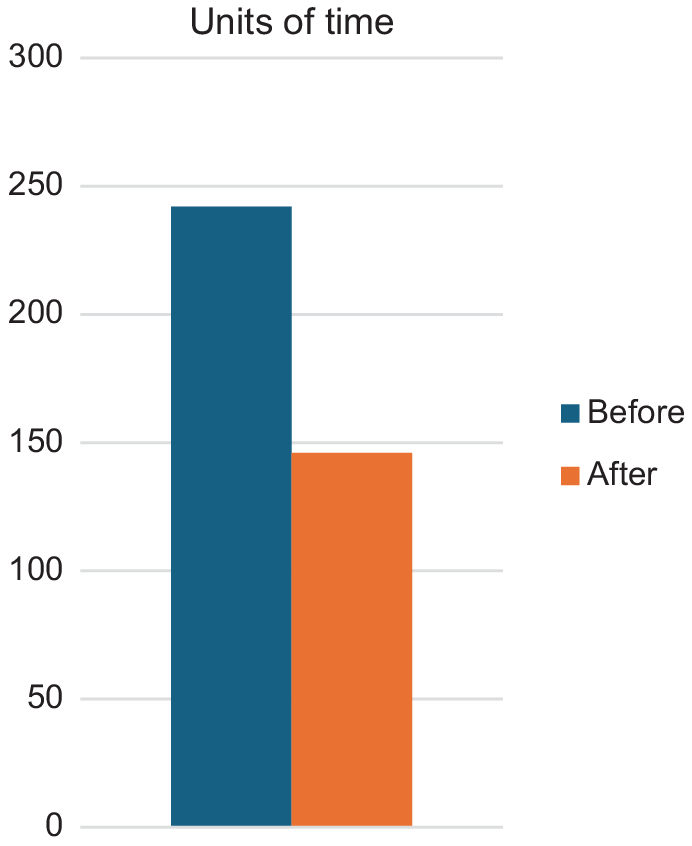

District nursing time is logged using units which is coded against various interventions, according to the care provided/contracts. Each unit equates to 10 min of time; in the before device period 2420 min of nurse time was spent in total for all five patients. After use of UroShield®, 1390 min was needed, which included the extra time and two nurse visits for education/support when first commencing use of the device. Fig. 2 shows the comparison data for each patient.

Twenty-five feedback forms were sent out amongst the nursing team, with requests in newsletters and in-person reminders to complete them; only one was returned which was from a nurse who had not had any input to any of the patients’ care which prevented analysis of nursing thoughts on UroShield®.

Organisational outcomes

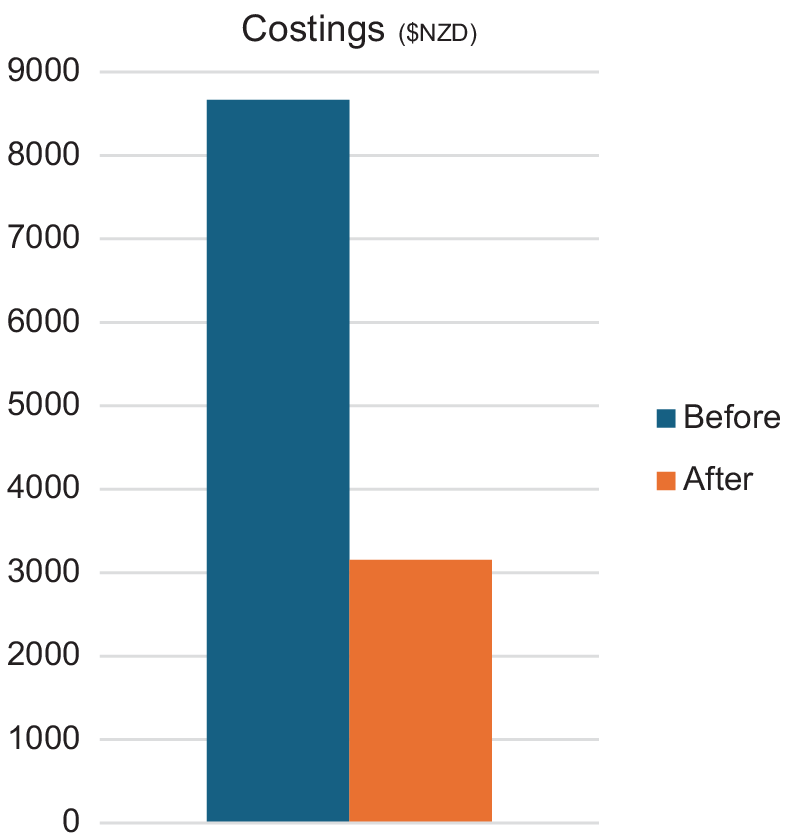

In the 5 months pre-UroShield®, total costs were NZ$8666.68, reducing to NZ$3160.82 over the 5 months post implementation, as per Fig. 3. These improvements included visits with no need for clinical interventions, as they were for extra education/support for patients and/or caregivers in the early stages of usage. It is worth noting that the initial expense of purchasing UroShield® has not been included in the analysis, as they are not single person use so are a long-standing asset to the service/organisation overall. Each UroShield® comes with one actuator clip and costs NZ$874.50 (+GST 15%), with further individual actuators costing NZ$83.73 (+GST 15%); these are changed every 6 weeks, or with each IUC change.

There were no hospital admissions in the time UroShield® was in use.

Discussion

Improved clinical outcomes

The use of UroShield® showed improvement in patient outcomes from the clinical interventions and complication rates. There was an 86% reduction in UTI incidence; 70% reduction in catheter blockages; 82.8% less bladder irrigations performed and 52.3% less catheter changes.

During data analysis, it was found one patient had had two changes of catheter due to blockage. There is minimal documentation around other troubleshooting options, when in both instances the patient had not had a bowel motion for seven days. Catheter blockage is often caused by simple factors such as tight clothing, kinked tubing, poor positioning, poor diet, and fluid intake which leads to constipation.4 Another patient had a change of catheter after a caregiver reported an infection and commencement of oral antibiotics; the antibiotics were for a chest infection, not a urine infection, but this was not ascertained until after it had been changed. One incidence of a bladder washout occurred, despite documentation stating there was no blockage, and urine was clear of debris, with rationale given as ‘patient insisted’. Literature shows that education within community healthcare teams is variable, resulting in task-orientated care where nurses follow care plans set by colleagues with an absence of clinical judgement.40–42

One patient was overdue Botox administration at urology for bladder spasm management, meaning he had ongoing leakage from his suprapubic catheter (SPC) site. He stopped the device after 2 months due to altered cognitive state and entering a worsened state of depression from reduced DN interaction. Loneliness amongst the elderly population is becoming more prevalent and has negative connotations for overall wellbeing, with psychological and physiological symptoms developing.43

Improved service outcomes

In comparing the before and after data, there was a 40.9% reduction in the units of time spent with patients and 14.2% fewer urgent call outs.

It was discovered that several visits in the months before UroShield® usage were documented, but no units of time on the electronic system. This affects the overall comparison of the time saved and would likely have been higher. It is worth noting that different nurses have differing skill sets and experience as a DN which means there is no set amount of time each intervention should take; for example, a nurse with several years’ experience may take 20 min to do a bladder irrigation versus a newer nurse needing 40 min.

Much work is needed in terms of long-term catheter management plans and supporting nurses to challenge existing plans of care. Education around troubleshooting and use of clinical judgment instead of simply following the care plan needs to focus on the DNS unique position of autonomy within the community.18 Ongoing empowerment of staff to achieve optimum outcomes for their patients, rather than focussing on the financial gains will allow a more collaborative approach to care plans, and ensure personalised care is provided.44,45

Organisation outcomes

The final cost analysis has shown a significant reduction in resource expenditure due to a combination of less interventions, and less urgent call outs. The UroShield® proved to have a 63.5% reduction in resource cost over the 5 months of the project. Hospital admissions for catheter-related problems pre-use totalled five inpatient days, in comparison to just 2 h in ED during use, which was unrelated to biofilm formation, but trauma to the insertion site. Use of primary care providers’ time and resources, was also reduced through less need for GP visits for prescriptions.

Despite long-term catheter patients having access to specialist nursing care in the community, there are increasingly more and more ED presentations due to catheter-related complications. A study performed in an NHS Trust in England showed that half of patients who attended the ED with catheter-related problems arrived in daytime hours due to a lack of timely response within the community.46 This demand–capacity gap is not new for DNS and is recognised across the globe.47 This case study shows the potential for reducing this further within the organisation, through reducing workload and increasing access to DN care for others.

Incidental findings

There were several incidental findings from initial review of the five patients. Documentation around description of usual urine output or visual appearance is lacking. Task focused care is frequently evident for urgent call outs, with patients often phoning in with a blockage or leakage and the immediate action is to perform an irrigation without investigation into why the blockage occurred. Care plans often lack clinical indications or rationale other than patient prefers the current regime or ‘the doctor said’ resulting in potential over visiting and wasted resources.

Accurate documentation is a core requirement of the Nursing Council of New Zealand (NCNZ) which protects patients’ outcomes and ensures high quality care.48 Documentation of all catheter care helps anticipate care needs and identify new patterns indicating change of condition, allowing for accurate care planning.4 Many of these findings could be tackled through the roll-out phase if UroShield® is adopted, to improve care and produce a gold standard protocol within the service.

Limitations

There were several limitations to this project. The cohort of patients was from one small urban area within the DNS; none of them lived rurally. Spinal injury patients were not included in the clinical audit/patient selection due to strict protocols set by the spinal unit post initial injury; these patients are potentially the most likely to benefit from the device and lead to the biggest cost saving long-term; the specialists at spinal units will need to be consulted in the roll-out to these patients. Feedback from nurses was minimal; completion of the paper-based questionnaire may have impacted this, as it was another thing to-do within their busy day.

Conclusion

This case study documents the implementation of UroShield® on five patients with regular catheter-related complications within the DNS, with the aims of improving incidence of clinical interventions, and potential for improved QoL for patients. Moreover, the project aimed to improve DN workloads and reduce resource expenditure across the organisation.

Improvement to patient QoL is likely, simply from less reliance on the DNS for the cohort of patients examined. A formal ethics approved randomised controlled trial (RCT) is needed to examine the full effectiveness of UroShield® on QoL amongst this population.

The number of DN visits, and time spent with each patient was greatly reduced, which has the potential to have a vast impact on nurse workload service wide, particularly if implemented amongst the spinal injury patients within the service. A need for more support and education of nurses around best-practice for catheter management was discovered, as there were inconsistencies found around the current regime and clinical need. Lack of nurse feedback provided inadequate insight into how things could have been done better from their perspective.

The reduction in clinical interventions and nurse time, resulted in a significant cost saving for the organisation, with complete avoidance of any catheter-related hospital admissions. The initial expense of purchasing UroShield® is outweighed by the fact that they are reusable for multiple patients and can be utilised by others if not suitable once commenced.

The success of this QI project led to UroShield® being incorporated into regular long-term catheter management plans within the DNS. This could potentially inspire uptake of UroShield® further across NZ, improving QoL for IUC patients nationwide.

Data availability

The data that support this study will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

1 MidCentral District Health Board. Annual report for year ended 30 June 2021. Pūrongo ā-tau. Palmerston North, NZ: MidCentral District Health Board; 2021. Available at https://www.tewhatuora.govt.nz/publications/midcentral-dhb-annual-report-2020-2021 [cited 24 February 2025]

2 Mackay WG, MacIntosh T, Kydd A, Fleming A, O’Kane C, Shepherd A, et al. Living with an indwelling urethral catheter in a community setting: exploring triggers for unscheduled community nurse “out-of-hours” visits. J Clin Nurs 2018; 27(3–4): 866-75.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

3 Holroyd S. Blocked urinary catheters: what can nurses do to improve management? Br J Community Nurs 2019; 24(9): 444-7.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

4 Jordan DA. The role of the district nurse in managing blocked urinary catheters. Br J Community Nurs 2022; 27(7): 350-6.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

5 Dean J, Ostaszkiewicz J. Current evidence about catheter maintenance solutions for managment of catheter blockage in long-term urinary catheterisation. Aust N Z Cont J 25(3): 74-80.

| Google Scholar |

6 Gibney LE. Blocked urinary catheters: can they be better managed? Br J Nurs 2016; 25(15): 828-33.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

7 Lydeamore MJ, Mitchell BG, Bucknall T, Cheng AC, Russo PL, Stewardson AJ. Burden of five healthcare associated infections in Australia. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2022; 11(1): 69.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

8 Grae N, Singh A, Jowitt D, Flynn A, Mountier E, Clendon G, et al. Prevalence of healthcare-associated infections in public hospitals in New Zealand, 2021. J Hosp Infect 2023; 131: 164-72.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

9 Musco S, Giammò A, Savoca F, Gemma L, Geretto P, Soligo M, et al. How to prevent catheter-associated urinary tract infections: a reappraisal of vico’s theory – is history repeating itself? J Clin Med 2022; 11(12): 3415.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

10 Smith DRM, Pouwels KB, Hopkins S, Naylor NR, Smieszek T, Robotham JV. Epidemiology and health-economic burden of urinary-catheter-associated infection in English NHS hospitals: a probabilistic modelling study. J Hosp Infect 2019; 103(1): 44-54.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

11 Hernandez M, King A, Stewart L. Catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI) prevention and nurses’ checklist documentation of their indwelling catheter management practices. Nurs Prax Aotearoa N Z 2019; 35(1): 29-42.

| Google Scholar |

12 Menegueti MG, Ciol MA, Bellissimo-Rodrigues F, Auxiliadora-Martins M, Gaspar GG, Canini SRMdS, et al. Long-term prevention of catheter-associated urinary tract infections among critically ill patients through the implementation of an educational program and a daily checklist for maintenance of indwelling urinary catheters: a quasi-experimental study. Medicine 2019; 98(8): e14417.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

13 Newman DK, Rovner ES, Wein AJ. Indwelling (transurethral and suprapubic) catheters. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2018. Available at http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-319-14821-2 [cited 18 October 2024]

14 Shepherd A, Newman DK, Bradway C, Jost S, Waddell D, Mackay WG, et al. Impact of practice on quality of life of those living with an indwelling urinary catheter – an international evaluation. Urol Nurs 2023; 43(4): 162.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

15 Shepherd AJ, Mackay WG, Hagen S. Washout policies in long-term indwelling urinary catheterisation in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017; (3) (3) CD004012.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

17 National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Healthcare-associated infections: prevention and control in primary and community care; 2012. Available at www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg139

18 Gethffe KA. Bladder instillations and bladder washouts in the management of catheterized patients. J Adv Nurs 1996; 23(3): 548-54.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

19 Marcone Marchitti C, Boarin M, Villa G. Encrustations of the urinary catheter and prevention strategies: an observational study. Int J Urol Nurs 2015; 9(3): 138-42.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

20 Rajaramon S, Shanmugam K, Dandela R, Solomon AP. Emerging evidence-based innovative approaches to control catheter-associated urinary tract infection: a review. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2023; 13: 1134433.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

21 Loike JD, Plitt A, Kothari K, Zumeris J, Budhu S, Kavalus K, et al. Surface acoustic waves enhance neutrophil killing of bacteria. PLoS ONE 2013; 8(8): e68334.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

22 Navarro S, Sherman E, Colmer-Hamood JA, Nelius T, Myntti M, Hamood AN. Urinary catheters coated with a novel biofilm preventative agent inhibit biofilm development by diverse bacterial uropathogens. Antibiotics 2022; 11(11): 1514.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

23 Abdel-fattah M, Johnson D, Constable L, Thomas R, Cotton S, Tripathee S, et al. Randomised controlled trial comparing the clinical and cost-effectiveness of various washout policies versus no washout policy in preventing catheter associated complications in adults living with long-term catheters: study protocol for the CATHETER II study. Trials 2022; 23(1): 630.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

24 Davis M. When guidelines conflict: patient safety, quality of life, and CAUTI reduction in patients with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord Ser Cases 2019; 5(1): 56.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

25 Balik V, Šulla I. Autonomic dysreflexia following spinal cord injury. Asian J Neurosurg 2022; 17(02): 165-72.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

26 European Association of Urology. EAU guidelines on urological infections. Arnhem, Netherlands: EUA Guidelines Office; 2023. Available at https://uroweb.org/guidelines

27 Köves B, Magyar A, Tenke P. Spectrum and antibiotic resistance of catheter-associated urinary tract infections. GMS Infect Dis 2017; 5: Doc06.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

28 Van Meel TD, De Wachter S, Wyndaele JJ. The effect of intravesical oxybutynin on the ice water test and on electrical perception thresholds in patients with neurogenic detrusor overactivity. Neurourol Urodyn 2010; 29(3): 391-4.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

29 D’Incau S, Atkinson A, Leitner L, Kronenberg A, Kessler TM, Marschall J. Bacterial species and antimicrobial resistance differ between catheter and non–catheter-associated urinary tract infections: data from a national surveillance network. Antimicrob Steward Healthc Epidemiol 2023; 3(1): e55.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

30 Richards MJ, Edwards JR, Culver DH, Gaynes RP, National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System. Nosocomial infections in combined medical-surgical intensive care units in the United States. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2000; 21(8): 510-5.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

31 Hazan Z, Zumeris J, Jacob H, Raskin H, Kratysh G, Vishnia M, et al. Effective prevention of microbial biofilm formation on medical devices by low-energy surface acoustic waves. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2006; 50(12): 4144-52.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

32 Wang L, Zhang S, Keatch R, Corner G, Nabi G, Murdoch S, et al. In-vitro antibacterial and anti-encrustation performance of silver-polytetrafluoroethylene nanocomposite coated urinary catheters. J Hosp Infect 2019; 103(1): 55-63.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

33 Wille JC, Van Oud Alblas AB, Thewessen EAPM. Nosocomial catheter-associated bacteriuria: a clinical trial comparing two closed urinary drainage systems. J Hosp Infect 1993; 25(3): 191-8.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

34 Madeo M, Barr B, Owen E. A study to determine whether the use of a preconnect urinary catheter system reduces the incidence of nosocomial urinary tract infections. J Infect Prev 2009; 10(2): 76-80.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

35 Pomfret I, Bayait F, Mackenzie R, Wells M, Winder A. Using bladder instillations to manage indwelling catheters. Br J Nurs 2004; 13(5): 261-7.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

36 Mayes J, Bliss J, Griffiths P. Preventing blockage of long-term indwelling catheters in adults: are citric acid solutions effective? Br J Community Nurs 2003; 8(4): 172-5.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

37 Da Silva K, Ibbotson A, O’Neill M. The effectiveness of Uroshield in reducing urinary tract infections and patients’ pain complaints: retrospective data analysis from clinical practice. Med Surg Urol 2021; 10: 254.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

38 Markowitz S, Rosenblum J, Goldstein M, Gadagkar HP, Litman L. The effect of surface acoustic waves on bacterial load and preventing Catheter- associated Urinary Tract Infections (CAUTI) in long term indwelling catheters. Med Surg Urol 2018; 07(04): 210.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

39 National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Uroshield for preventing cathter-associated urinary tract infections; 2022. Available at https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/mtg69

40 Gesmudno M. Enhancing nurse’s knowledge on catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI) prevention. Kai Tiaki Nurs Res 7(1): 32-40.

| Google Scholar |

41 Harrison JM, Dick AW, Madigan EA, Furuya EY, Chastain AM, Shang J. Urinary catheter policies in home healthcare agencies and hospital transfers due to urinary tract infection. Am J Infect Control 2022; 50(7): 743-8.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

42 Nibbelink CW, Brewer BB. Decision-making in nursing practice: an integrative literature review. J Clin Nurs 2018; 27(5–6): 917-28.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

43 Carrasco PM, Crespo DP, Rubio CM, Montenegro-Peña M. Loneliness in the elderly: association with health variables, pain, and cognitive performance. a population-based study. Clínica Salud 2022; 33(2): 51-8.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

44 Hughes Spence S, Khurshid Z, Flynn M, Fitzsimons J, De Brún A. A narrative inquiry into healthcare staff resilience and the sustainability of quality improvement implementation efforts during Covid-19. BMC Health Serv Res 2023; 23(1): 195.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

45 McKendry M, Green H. Improving the personalisation of care in a district nursing team: a service improvement project. Br J Community Nurs 2018; 23(11): 552-8.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

46 Tay LJ, Lyons H, Karrouze I, Taylor C, Khan AA, Thompson PM. Impact of the lack of community urinary catheter care services on the Emergency Department. BJU Int 2016; 118(2): 327-34.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

48 New Zealand Nurses Organisation. NZNO practice guidelines: documentation; 2012. Available at https://www.nzno.org.nz/Portals/0/publications/Guideline%20-%20Documentation,%202021.pdf