Trauma-informed management of patients with prior sexual trauma in pelvic health physiotherapy clinical practice

Janine Stirling A B * , Zoe Wallace C D , Angela James D E , Rita Shackel F and James Elliott A GA

B

C

D

E

F

G

Abstract

Pelvic health (PH) physiotherapists treat a range of pelvic floor conditions, with more than 20% of those seeking treatment having a prior history of sexual assault or childhood sexual abuse. This Discussion Paper incorporates an integrated case study of a patient who was sexually assaulted as a teenager and went on to develop Genito-Pelvic Pain Penetration Disorder (GPPPD). The authors collectively share multidisciplinary insights in physiotherapy, psychology, psychotherapy, nursing, law and trauma research to advocate for a tailored evidence-based approach to treating patients with sexual trauma. A trauma-informed perspective creating safety, screening and consent will be offered. Graded exposure techniques to facilitate an adaptive and flexible patient response to cues of safety vs threat will be introduced. Empathic responding, being attentive and attuned to a patient’s trauma triggers could translate to improved patient outcomes. Inadvertently, these same qualities may place PH physiotherapists at risk for vicarious trauma. Harmonising this delicate intersection where clinicians are required to flexibly pivot between containing hyper/hypo arousal for the patient with empathic, attuned responding to ensure a safe treatment milieu, is a specific focus. We invite further collaboration from this review article, serving as a catalyst for developing rigorous clinical practice guidelines for PH physiotherapists to be confident and competent when managing patients presenting with history of sexual trauma.

Keywords: childhood sexual abuse, deep brain reorienting, dyspareunia, Genito-pelvic pain penetration disorder, pelvic health physiotherapy, pelvic pain, post-traumatic stress disorder, rape, sexual assault, sexual trauma, somatic experiencing, tonic immobility, trauma-informed care, vaginismus, vicarious trauma.

Introduction

The term ‘sexual assault’ incorporates a wide range of unwanted sexual experiences. These can occur during adulthood or childhood and may include rape, sexual assault with a weapon or object, coercion, intimidation, and attempts to force sexualised activity that may or may not include penetration.1 Often the longer-term impacts of such experiences are complex, affecting sense of self, ability to regulate emotion, a morphed sense of wellbeing or diminishing functional capacity if dissociation is a feature.2–4 More than a third of women who endure sexual trauma go on to experience post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD),5–7 with fluctuations in mood, arousal, intrusions, and avoidance of trauma related reminders.8 Intimate relations, gynaecological surgery, and childbirth can trigger subliminal reminders; especially if there is a sensed loss of control, diminished agency or when body boundaries are challenged.9–12

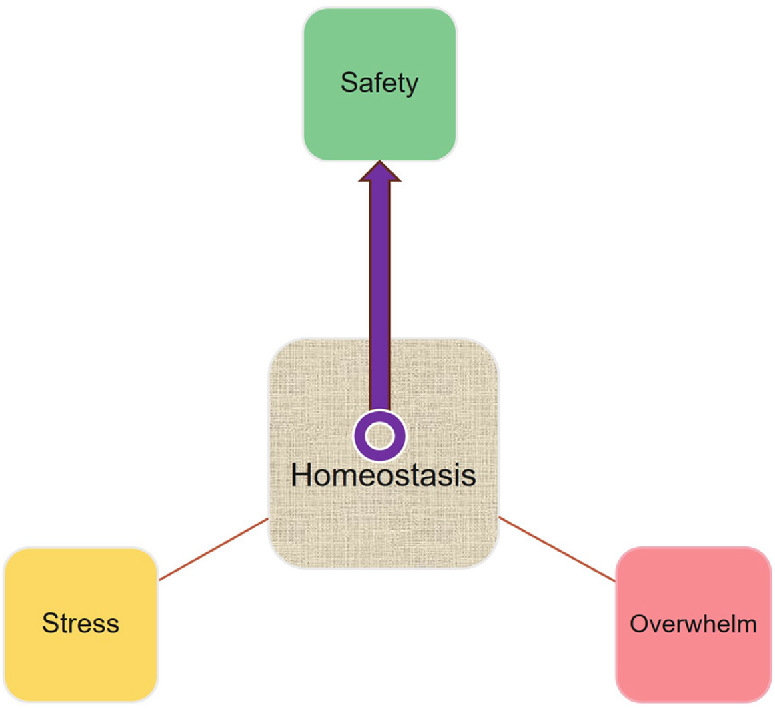

Neurobiological and physiological changes following a highly stressful and possibly life-threatening event such as sexual assault, can drive and maintain symptoms of pain, anxiety, PTSD and mood dysregulation. The focus in treatment is on shifting from ‘stress’ or ‘overwhelm’ (represented in Fig. 1),13,14 to ‘safety’, to establish homeostasis. ‘Basically, when humans feel safe, their nervous systems support the homeostatic functions of health, growth, and restoration, while they simultaneously become accessible to others without feeling or expressing threat and vulnerability’ (p. 1).14

This discussion, based on experiences from interviews, clinical experiences and literature, aims to bridge the gap between what is known in the literature in terms of clinical conditions associated with prior sexual trauma and the survival response activated during sexual assault; and what is less well known, which is how to identify, assess, and support patients with this history when they present for pelvic health (PH) physiotherapy. A person-centred, trauma-informed approach is used throughout, to cultivate safety and to promote sociality. Sociality is the natural inclination humans have, to connect and engage socially with one another, it is adversely impacted by threat and fear and is restored under conditions of safety.13,14 A collaborative, two-way communication style is thus encouraged, to build safety and trustworthiness and to empower the patient. Offering choice and involving them actively, wherever possible, within a dignified non-discriminatory treatment environment.15–17

Methodology

In March 2024, author JS jointly interviewed authors AJ and ZW, two PH physiotherapists with over three decades of combined PH work experience. The 1-h unstructured interview, focused on exploring knowledge they had acquired in relation to treating patients in clinical practice with prior sexual trauma (from adult sexual assault or childhood sexual abuse). The interview was audio recorded, and the recording was transcribed verbatim. A central theme emerged for investigation: how to work safely in clinical practice with individuals who have endured sexual trauma. This informed the literature search.

The case example that follows is included to bring the narrative to life; it is not based on a specific patient; rather, it represents the integration of numerous patient presentations to PH physiotherapy, based on the authors’ professional experience. The patient in the case example presents with Genito-Pelvic Pain Penetration Disorder (GPPPD), and in some instances this condition may be related to prior sexual trauma. However, any presenting condition could be substituted for GPPPD as the intention of this article is to outline the complexity and impact of sexual trauma. To inform clinical practice in a way that supports patient and PH physiotherapist safety, through enhanced awareness and understanding.

Case example

Kelly is 31 years old and lives with her husband Jack; they have been married for 14 months. She is referred to PH physiotherapy by her general practitioner (GP) who outlines that Kelly would like to conceive a baby, yet painful attempts at intercourse (dyspareunia) due to painful, tight and non-relaxing pelvic floor muscles (vaginismus), prohibit their shared aspiration to start a family.

Her GP has diagnosed GPPPD, following unsuccessful attempts at speculum examination. At 17, Kelly’s first sexual experience was one of rape. Now during opportunities to have sex, Kelly describes pain, fear, active avoidance of vaginal penetration and on some occasions sensory intrusions of the sexual assault.

In PH physiotherapy, Kelly identifies goals of becoming comfortable with intimacy with Jack, use of tampons, and tolerating speculum examination without distress.

The downstream impact of sexual assault

Pelvic pain, emotional distress, hyperarousal, fear, avoidance and sensory intrusions comprise Kelly’s post rape experience. In the literature, many health conditions across the lifespan have been linked to prior experiences of sexual assault. These include PTSD, depression, anxiety, sleep and eating disorders, fibromyalgia, sexual dysfunction, chronic pain, pelvic pain, gastrointestinal dysfunction and suicide ideation with attempts.18–22

In a study that investigated faecal incontinence and constipation in participants with and without prior sexual trauma, symptoms were considered more severe and quality of life was scored lower in those with sexual trauma, compared to those without, despite both groups having similarly abnormal anorectal pathology.23 Episiotomies and hysterectomies were also more common in the sexual trauma cohort.23 Although many factors could underpin these findings, one to note is altered pain processing due to central sensitisation.23,24 Central sensitisation is a mechanism whereby pain is amplified, possibly due to somatosensory neuroplasticity driving increased excitability and/or decreased inhibition after the initial peripheral injury, nerve injury or inflammation has resolved. Exaggerated experiences of pain may then exist in the absence of injury, mediated by hypersensitivity within the central nervous system.23,25,26 Negative sensory-emotional experiences, with psychological, social and biological elements can then produce chronic pain, in the absence of recent tissue damage or injury.27

While adaptive responses to threat and pain are protective, allostatic load (see Appendix 1) and sensitivity towards innocuous stimuli in the absence of genuine threat, are restrictive and maladaptive from a biopsychosocial perspective.13

Active and passive survival responses

To better understand these sequelae and how they develop, a deeper understanding of what happens at the time of sexual assault is required, as sexual assault commonly activates an atypical survival response.

Typically, when an individual feels safe, the autonomic nervous system mediates involuntary ‘rest and digest’ functions. Survival-based responses are activated in response to danger or life-threat.13 Fight or flight active responses are evoked with danger if the threat is deemed escapable and/or able to be controlled.13,28,29 Then, sympathetic nervous system activation generates energy through catecholamine release, redirecting glucose from digestive functions towards perfusion of vital organs by increasing heart rate, blood pressure and breath rate to support confrontation with, or escape from, the threat.28,29 If, however, environmental life-threat is detected through sensory, deep joint/muscle and visceral pain, haemorrhage, or repeated engagements culminating in social defeat, then passive, dorsal vagal parasympathetic nervous system activation occurs.13,28,29 The result is diminished metabolic requirements and enhanced pain tolerance (from release of endogenous opioids). Characterised by a drop-in heart rate, blood pressure, and respiratory rate, these physiological mechanisms are designed to conserve energy.13,28,29

Tonic immobility

Van der Kolk,30 emphasises that processing and effective integration of memories requires ability to act on the environment.30 In essence, a profound and involuntary inability to act is where things go awry in sexual assault. Extreme fear together with sensed or actual inability to escape, initiate a reflexive survival response known as tonic immobility.31,32 This phenomenon, sometimes referred to as rape paralysis, is common during both adult sexual assault and childhood sexual abuse.22,31–34 A study that screened women for tonic immobility during rape, within a month of the assault, found 70% had experienced significant tonic immobility.22

Tonic immobility is a passive autonomic response to extreme life threat; it involves sympathetic activation initially followed by profound co-activation and dominance by the parasympathetic nervous system when escape is determined by sensory, visceral, spatial and proprioceptive inputs to be impossible.28,29 Some rape survivors describe having the urge to run away during tonic immobility, yet they are rendered immobile, ‘trapped internally’.6

Tonic immobility induced by a traumatic event is linked to more profound PTSD symptom scores, and lower pharmacological treatment success.29 Survivors report that they continue to feel vulnerable to immobility in the years that follow, especially during sexual contact or when consenting to intercourse.6 The inability to ‘act’ on the environment leaves a residue of dissociated, fragmented, implicit reminders.3,30,35 Retrieval of these reminders can occur during contextually similar situations or in somatic states reminiscent of the original trauma.3,30 This could include a situation such as a pelvic examination with a PH physiotherapist or speculum examination with a doctor. Even routine clinical procedures in hospital that involve insertion of a urinary catheter or treating incontinence-induced dermatitis, could evoke strong subliminal reminders for patients with prior sexual trauma. Responses during such procedures may elicit fear, anger, muscle tension, tremor, immobility, speechless terror, or a feeling of being sick, etc. This necessitates a well-considered strategy, to identify, assess, and support patients like Kelly, as central nervous system function is altered neurobiologically and physiologically by trauma.2,3,29

Central nervous system considerations

Neural circuits in the brain are comprised of populations of interconnected neurons that form networks; one such network is the salience network, that has projections to the periaqueductal grey (PAG).3 The salience, central executive and default mode networks of the brain are disrupted in those with PTSD.2,3 The salience network mediates functional connectivity between these networks and intense unexpected emotional or sensory stimuli will activate the salience network preferentially which mounts PAG driven defensive responses without accessing higher order brain processes to contextualise the source or type of threat.3

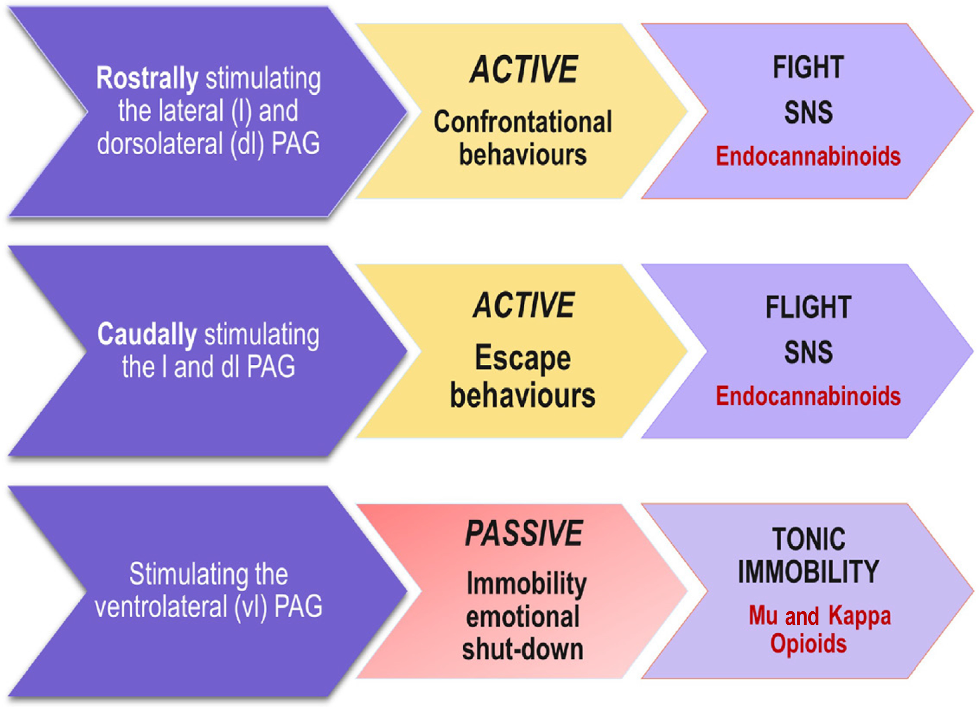

The PAG, located in the midbrain, is involved in reproductive functions and autonomic responses to support survival.36 Functionally, the PAG mediates pain, fear, active and passive responses to threat, anxiety, and respiratory and cardiac fluctuations in accordance with the region stimulated.36 For example, studies have shown that if the lateral, dorsal lateral part of the PAG is stimulated by excitatory amino acids then active fight/flight responses to threat occur, and endocannabinoids are released. If the ventral lateral (vl) part of the PAG is stimulated, then passive immobility in the context of threat unfolds.13,28,29 The reason survivors report spacey numbness with diminished pain sensation during rape where tonic immobility is experienced, is because endogenous opioids are released when the vlPAG is stimulated.29 Visceral pain, profound somatic pain and repetitive superficial pain can actuate the vlPAG.36

However if an individual feels safe, i.e. not stressed or under threat, then top-down processes involving the medial prefrontal cortex in the brain can inhibit the types of defensive bottom-up responses displayed in Fig. 2.37

Biopsychosocial considerations

Kelly, and patients with sexual trauma, may find consenting to an internal pelvic examination (per vaginam) to assess pelvic floor muscles, particularly stressful. A vaginal examination may create stress related arousal, sufficient to retrieve trauma memories with sensations and behaviours reminiscent of the original traumatic event.38 An internal examination could be likened to a form of graded exposure for patients with a history of sexual assault.

Exposure therapy in the field of psychology has shown efficacy and is considered effective as a treatment modality in improving symptoms of PTSD.39 In Somatic Experiencing (an approach developed by Peter Levine for working with trauma in the body), the aim in therapy is to foster safety and body awareness. Care is taken through titration and pendulation to not overwhelm the body as a system, as this could result in re-enactments of past trauma.40

To address Kelly’s GPPPD, over the course of several sessions, three core areas pertaining to safety, building capacity and neuromodulation will be addressed.

Shifting Kelly’s experience of threat to an experience of safety.

In the amygdala and especially in the dorsal vagal complex (which co-ordinates the parasympathetic immobility response), there are an abundance of oxytocin receptors.13 Oxytocin can reduce sensitivity to acute pain.41 Social interactions, affiliations with others, emotional and sensory processing are influenced by oxytocin.42 Oxytocin is key for autonomic regulation, enabling ‘safe immobility’.13,14 Phylogenetically, oxytocin supports pair bonding, copulation, and breast feeding, to facilitate safe immobility during these activities.13 The abundance of oxytocin receptors in the dorsal vagal parasympathetic complex, can under non-threatening conditions, attenuate defensive responding to support social engagement.13 If trauma-informed PH physiotherapy can provide a safe treatment platform, then patients can work on, learn about, and develop mastery in previously avoided, threatening body sensations.6

The aim in PH physiotherapy is to build capacity within the sensory nervous system, to enable Kelly to ‘register, organise and modulate incoming sensory information’ (p. 1)3 in such a way that sensations can be processed and integrated free from overwhelm. This will provide Kelly with agency to ‘act’ or respond behaviourally to sensory cues in a manner aligned with her goals.3

PH physiotherapists are instrumental in facilitating neuromodulation which involves psychoeducation, co-regulation and helping patients develop explicit awareness of physiological responses and changes in breath rate and muscle tension during treatment.

The above three components introduce a biopsychosocial foundation to working with patients who have experienced prior sexual trauma. A practical psychotherapeutic approach to treating trauma follows; this is intended to scaffold knowledge and understanding, especially around the neuroscience underpinning trauma processing.

Deep brain reorienting

Frank Corrigan, a psychiatrist and researcher, developed a neuroscientific-based PTSD treatment method known as Deep Brain Reorienting (DBR).43 DBR engages three subliminal regions of the brain (the superior colliculus, locus coeruleus and the PAG); together these three regions mediate the traumatic sequence that occurred during the original event. Later when triggered the same sequence will remain.43 In a psychotherapeutic trauma therapy approach using DBR, the initial focus is orienting, helping an individual ground in their body by guiding them verbally through a process aimed at spatially orienting them to the surrounding environment.43 In DBR the therapist draws the client’s attention to the orienting tension, by asking them to notice tension or tightness in the muscles surrounding the eyes, forehead, and posterior neck.43 ‘This orienting tension is the point of focus at the start of processing as it facilitates embodiment and provides a necessary anchor against emotional overwhelm’ (p. 4).43

In PH physiotherapy, physiotherapists are inadvertently practising some aspects of DBR, without necessarily being aware of the DBR model and the psychotherapeutic evidence to support how and why this may be an effective way to work with trauma. For example, when initiating treatment with a patient such as Kelly presenting with GPPPD, light touch with a tissue to the medial thigh or abdomen is used in clinical practice to assess tolerance. This may be followed by a Cotton Swab Test (lubricated cotton, moistened with gel or water), to apply gentle pressure to quadrants 12, 12-3, 3-6 etc., to test for the presence of allodynia at the vestibule.44 This process of drawing the patients awareness and attention to the sensations in this region, will likely engage the superior colliculus,43 the subcortical midbrain structure that cued and oriented Kelly at the time of the sexual assault, to the initial threat. The superior colliculus accesses trauma reminders through the dense connections this structure has with higher cortical regions of the brain.43

The Locus Coeruleus (LC) has projections throughout the brain and spinal cord and contains neurons that make norepinephrine.45,46 The LC has ascending pathways (to the hypothalamus, amygdala, hippocampus and cortex to regulate attentional arousal and cognitive pain appraisal) and descending pathways (to the PAG and spinal cord).45 In DBR, the LC is thought to be involved in mediating the shock component of trauma.43 Muscle tension/tone is enhanced in association with the connections the LC has to these norepinephrine sensitive, ascending and descending pathways.43 In the process of providing PH physiotherapy to Kelly, who has experienced prior sexual trauma, the physiotherapist may notice while digitally palpating Kelly’s muscles, physiological changes in muscle tension/tone. When noradrenaline is synthesised, Kelly’s muscle tone may increase, her breath rate may speed up, and as the trauma processes during treatment, the muscle tension may dissipate, and her breath may slow down or regulate towards an even rate. Being with Kelly and her experience in an attuned, attentive, responsive and compassionate manner, provides the safety that differentiates this experience from the one of threat and disconnection that occurred at the time of the sexual assault.

In PH physiotherapy, even the subtlest of palpation to pelvic floor muscles will likely activate an orienting response within the superior colliculus. The physiotherapist can then cue Kelly’s awareness to this pelvic floor muscle response (which may include tension, spasm, fasciculation, numbness etc.), with slow progression to ensure that Kelly remains connected, enabling an embodied experience free of overwhelm.43 Excessive stimulation can trigger overwhelm and defensive responding.43 In DBR the aim is to keep the individual grounded in the orienting tension with awareness. If this occurs, the affective elements pertaining to breath, viscera, and raw emotion can process appropriately through the PAG.43

Trauma-informed care in PH physiotherapy

Sexual assault is a relational trauma, involving a perpetrator or multiple perpetrators. Relational safety within the treatment environment is thus very important. Women who have experienced tonic immobility during rape report a less profound but related feeling of immobility return when they feel angry, afraid, or when they sense dismissal or feel out of control.6 Creating a treatment milieu that is free of provider busyness, distraction, and over-control will enable providers to attend and attune to the patient’s healthcare needs. PH physiotherapists can use non-threatening body postures, relaxed warm facial expression, and gentle inflections in tone of voice to communicate safety.13 Fostering relational safety in this way is required for Kelly to feel safe in her body.

Attuning to a patient’s healthcare needs using a person-centred approach that is accepting, genuine/authentic and empathic, can bring about therapeutic change.47 In Table 1, practical trauma-informed care strategies are offered by the authors, based on clinical experience. Defining comfort for a patient, is as unique as their individual trauma experience. Enquiry and open dialogue is thus important; physiotherapists may ask how best they can support the patient in feeling comfortable.7,55 In Kelly’s case, she elected to bring in her own music, and requested the curtain remain open when she undressed (the physiotherapist turned away). Honouring and respecting boundaries pertaining to touch, positioning, undressing etc. attenuates distress, that fear and feeling out of control elicit.6,7

| Strategy | Practical experiences | Examples and principles | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Screening tools | Screen patients with clear intention and purpose. Screening can yield valuable information; discernment is required to select the ‘best fit’ for the patient. Weigh up risk vs benefit. Calling to mind specific traumatic events/reminders can be upsetting for sexual trauma patients, prepare them for possible discomfort when completing questionnaires. | Examples of standardised questionnaires that may be appropriate for Kelly:

| |

| Sensitive enquiry | Some sexual trauma survivors may never have shared information of the assault with anyone before, memory recall of the abuse may be limited, especially if dissociation was a feature. Sensitive responding, in a person-centred, non-judgemental way promotes a safe space for information exchange. | Example of an open-ended explorative question

| |

| Building capacity | Start working externally with the body if sexual trauma is identified. This will allow clinical assessment of the patient’s body awareness, boundaries, and capacity to navigate and cope with increasing arousal. | Use the five Principles of Trauma-informed Care (in bold)

| |

| Identify compliance | Stemming from low self-esteem which could impact a patient’s capacity to set boundaries. | If a patient hands over responsibility, ‘you do what you need to do, and I’ll be right’. A collaborative opportunity exists; in helping the patient tune into their body, they will become more aware of their nervous system and response to touch. This models healthy boundary awareness. Empowering patients to actively participate in body boundary formation fosters an internal sense of safety. | |

| Regulating the body’s reaction to trauma | This collaborative approach requires co-regulation initially, building towards patient self-efficacy. Teaching mindfulness techniques and skills to manage overwhelming sensations in the body. Providing education, being curious, fostering a sense of awe and wonder in the body’s natural capacity to protect and survive. |

|

Throughout treatment, Kelly will be exposed to titrated (to tolerance) amounts of touch, cueing her attention to notice with awareness internal sensations, and where her body is positioned. The PH physiotherapist supports Kelly in this process by observing with her and checking in as fluctuations are noticed. For example, if a sympathetic response is evoked during treatment and Kelly becomes tachypnoeic, or if parasympathetic dominance produces brief apnoea, then the physiotherapist can model safety using even tempo breathing (10–12 breaths/min), to invite co-regulation. This way of connecting with Kelly through the breath is not necessarily explicitly articulated, rather the physiotherapist may accentuate their breath to communicate safety non-verbally to Kelly. Depending on Kelly’s capacity to regulate in the moment, she may mirror the physiotherapists breathing, or she may not. There is no expected outcome, rather the point is to invite Kelly’s awareness to what is happening in her body, with her breath in that moment.

Other observable autonomic measures may include supporting Kelly in noticing changes in heartbeat (thudding in the chest) or temperature (facial, neck flushing), which is indicative of stress activation. This way of working invites curiosity in the body and its capacity to protect. Pendulation towards and away will dictate the line between safe versus threatening, enabling the physiotherapist to work in a range with Kelly where she can benefit from treatment, without fear intruding and causing overwhelm.

Breath work can also be used as a resource to calm the nervous system. Slow, deep, rhythmic, diaphragmatic breathing promotes self-efficacy in regulating arousal and managing pain.56 Diaphragmatic breathing benefits cardiopulmonary perfusion, stroke volume and vital organ circulation.57 Patient education coupled with exercise therapy is highly regarded in physiotherapy.58 Diaphragmatic breathing can be used as a form of exercise therapy to build rapport, rhythm, connection, and co-regulation with patients.

Screening for trauma

Screening patients for sexual trauma is important, especially considering that PH physiotherapy could involve offering patients the choice of undergoing an internal examination (per vaginam), which requires removal of underwear and lying down. The nature of these sorts of activities could cue sensory, interoceptive, proprioceptive and vestibular pathways. As highlighted earlier, the salience network, superior colliculus, locus coeruleus and PAG will drive defensive responding, where fear associated with unprocessed trauma resides. Screening provides knowledge of prior trauma; this can be used to adequately prepare the PH physiotherapist and the patient.

Several types of screening questionnaires are available, and those that may complement care provision for Kelly are listed in Table 1. Currently, research into screening reveals some physicians lack confidence to screen patients and cite this as a barrier, feeling ill-equipped to respond, despite awareness that screening may be beneficial in detecting abuse.59 In a gynaecology-oncology study screening was considered helpful to both providers and patients, reducing emotional distress during interventional procedures, if a need for trauma-informed care and counselling was identified early.60 A clear evidence gap in PH physiotherapy research exists to determine if physiotherapists are confident screening patients for sexual trauma and how this may impact patient treatment outcomes.

Consent

Gaining patient consent prior to proceeding with assessment and treatment, verbal, inferred or in writing, is arguably protective for both the PH physiotherapist and the patient. Consent prepares and informs patients of the procedure they are about to undergo. It ought to be current, specific, and voluntarily given with adequate time and capacity for patient understanding, consideration, and for outside consultation to be sought free of coercion. Disclosure of sufficient information is required to ensure consent is informed. At any stage the person providing consent can change their mind and withdraw their consent.61,62 Informed consent ought to include what any individual under reasonable circumstances would value knowing, such as risks, benefits, and alternative options to the proposed assessment or treatment.63 In PH physiotherapy, alternative options for consent may extend to allowing the patient to choose at each appointment the way the pelvic floor muscles and nervous system are assessed. For example, using transabdominal ultrasound to assess and provide biofeedback on pelvic floor muscle contraction, or observing with/without touch in the region of the perineum, or applying variable depth and pressure during internal assessment (per vaginam). Informed consent benefits patient autonomy by respecting the patient’s agency in deciding what is right or best for them. As insufficient time is identified as a potential impediment to achieving informed consent, planning to ensure adequate time is available is imperative.63

In Kelly’s case, a first session may involve a discussion about assessment and treatment options, with an opportunity for Kelly to ask questions and actively participate in the discussion. Explaining and demonstrating how an examination is performed, why it may provide valuable diagnostic information, and what the purpose of pelvic floor muscle relaxation is, in the context of addressing her presenting condition, are all pillars of informed consent. Muscle assessment, palpation and treatment techniques could elicit reminders of past trauma, as already mentioned; ensuring Kelly is aware and prepared for this is important. Offering Kelly control throughout: ‘if you need me to stop at any point, please let me know, hand up/push me away if you need, you are in charge’, this sort of approach reiterates the ability for consent to be withdrawn at any time, as consent is not intended to be ‘once off’ but rather iterative in nature.

Acquiescence during sexual assault is sometimes mistakenly considered implied consent, when in fact if tonic immobility is experienced, this involuntarily inhibits vocal and physical expression.10,22,34 Effort must be taken in PH physiotherapy to ensure that patients can stop treatment if threat activation prevents more traditional avenues of communication. Author clinical experience supports the following clinical strategies if immobility occurs during treatment; raise the head of the treatment bed to around 45°, orient the patient to the treatment environment, and provide a pen and paper to facilitate another option for connection when verbal communication is lost.

Even with every effort and attentive attunement by the physiotherapist, an immobility response may still occur in the early part of PH physiotherapy, mediated by subliminal reflexive responding. If this occurs, an opportunity exists for patient-provider collaboration to instil greater safety going forward by analysing what happened in the patient’s body from the perspective of what they sensed and felt. Overwhelm can be managed by titrating smaller amounts of exposure, using pendulation towards and away, in a manner that enables and builds tolerance.

Treatment goal for sexual trauma patients in PH physiotherapy

‘Access to sociality as a neuromodulator is influenced by both autonomic state and the flexibility or resilience that an individual’s autonomic state has in returning from a state of threat to a state that supports homeostasis’ (p. 4).14

This is the explicit goal when working with sexual trauma survivors – developing autonomic flexibility – so that appropriate and adaptive responses to incoming sensory information occurs.13 Encouraging Kelly to be curious in learning the language of her body. This can be achieved by supporting her in noticing, for example, tension in the muscles or fluctuations in her breath or heart rate. PH physiotherapists are uniquely placed to potentially orchestrate a shift from stressed or overwhelmed responding, to embodied choice and a felt sense of safety in the body. In providing a physically and socially safe space in physiotherapy for Kelly to ‘act’ on the environment, unprocessed sensory and motor traces of traumatic memory can be somatically experienced with successful action sequences that immobility previously denied.35,40 This process enables repressed trauma memories to be recovered into conscious awareness, where the memory then has context, is grounded in time, and can be consciously recalled.35

Safety for PH physiotherapists to mitigate vicarious trauma

If a healthcare practitioner has experienced prior sexual trauma themself, distressing reminders may resurface when treating patients with this history, and this could impact the practitioner’s wellbeing. Furthermore, in the field of mental health, a link exists between caseload of trauma patients, especially sexual trauma patients, and heightened risk of vicarious trauma for the treating practitioner.64–66 Vicarious trauma comes about from indirect exposure to other people’s trauma. Through repeatedly witnessing the emotional and psychological toll of trauma and in validating and responding empathically, practitioners themselves can be at risk of becoming traumatised. Some may even develop PTSD.64,65,67 Working relationally with raw emotion, memories, and details of trauma, can influence a practitioner’s sense of self, the way they view the world, their sleep, ability to concentrate and discern appropriate action, even interpersonal relationships outside of work can be impacted.65,68

This is undoubtedly a concern for PH physiotherapists who may treat numerous patients with sexual trauma daily, or in the course of a clinical work week. Sexual trauma in Australia impacts as many as 1 in 4 women and 1 in 12 men.69 Alarmingly, there are 28.6 rapes per one hundred thousand women, positioning Australia 11th in the world for reported cases of rape.70 Sexual trauma is thus prevalent and a framework to manage vicarious trauma as a potential workplace psychosocial hazard is required. See Table 2.

| Risk management strategies can be implemented at an individual and practice level | ||

|---|---|---|

| At an individual level | At a practice level | |

|

| |

| Hierarchy of controls73 | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1. Elimination | Involves removing the hazard completely.73 An example here might be that PH physiotherapists in private practice can sensitively refuse to treat patients with sexual trauma. Elimination is an opportunity to mitigate vicarious trauma at the outset. | |

| 2. Substitution | Identify an alternative and refer to a PH physiotherapist with specialist knowledge and training in sexual assault and trauma-informed care. | |

| 3. Engineering controls | This measure uses technology to address the hazard.73 It may involve making the environment more comfortable in terms of lighting, positioning of equipment, acoustics etc. | |

| 4. Administrative controls | Have policies in place, trauma-informed training, healthy boundaries with patients. In psychology-based professions supervision is a registration requirement that offers another perspective, an opportunity to debrief, reflect, and to review the impact on self of providing this type of trauma support to another. Creating a warm, accepting, growth driven professional environment can serve as an antidote to carrying work stress alone. | |

| 5. Work-practice controls | Longer predetermined appointment times may be required to adequately meet the biopsychosocial needs of sexual trauma patients. While ensuring that once a session time is established, it is adhered to where possible, ensuring patient expectations around time are maintained. This planned approach provides a boundary that is protective for both the clinician and the patient. | |

| 6. Personal protective equipment (PPE) | Healthy intrapersonal boundaries – balancing work demands with self-care activities. Screening employees for stress to ensure early detection to mitigate unrelenting exposure transitioning into chronic stress or even PTSD. PPE for sexual trauma work may include establishing explicit boundaries for patient support and contact, for example, channelling in the first instance out of session communication through reception and following up with patients at a convenient time. | |

Conclusion

Trauma-informed care uses person centred skills to work with and enable patients to develop sensory capacity and tolerance for new adaptive experiences, free of fear-based reflexive responses. By fostering an embodied sense of safety, PH physiotherapists can work collaboratively with patients to improve resilience, promote flexibility and to restore balance within the autonomic nervous system.

Evidence-based research to support PH physiotherapists in this emerging field is required. Although sexual trauma is not new, treatments for the adverse biopsychosocial sequelae are evolving, informed by advances in knowledge, skill and technology. This Discussion Paper extends an invitation to engage collaboratively with the authors and others in the field, to develop training programs to better meet the needs of PH physiotherapists who routinely treat patients with sexual trauma. There is urgent need for further research to establish competency frameworks, policies and procedures to support PH physiotherapists in this important work.

Data availability

The data that support this study will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of interest

JS received payment from Australian Physiotherapy Association for a lecture provided on Trauma-informed Care to WMPH physiotherapists. ZW is the NSW APA WMPH Vice Chair. AJ is the National APA WMPH Chair, and a member of the Clinical Advisory Committee Endo Australia and the Clinical Advisory Committee ABTA. JE receives renumeration from online educational programs unrelated to this manuscript and is the Board Director for NED SAMSN and an Advisory Board Member of Ho’ola Na Pua. The authors declare that they have no further conflicts of interest.

References

1 Freedman E. Clinical management of patients presenting following a sexual assault. Aust J Gen Pract 2020; 49(7): 406-411.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

2 Lanius RA, Terpou BA, McKinnon MC. The sense of self in the aftermath of trauma: lessons from the default mode network in posttraumatic stress disorder. Eur J Psychotraumatol 2020; 11(1): 1807703.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

3 Kearney BE, Lanius RA. The brain-body disconnect: a somatic sensory basis for trauma-related disorders. Front Neurosci 2022; 16: 1015749.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

4 Speckhard Pasque L. The lingering effects of sexual trauma. Mayo Clinic Press Article: Women’s Health website; 2023. Available at https://mcpress.mayoclinic.org/women-health/lingering-effects-of-sexual-trauma/ [cited 16 October 2024]

5 Dworkin ER. Risk for mental disorders associated with sexual assault: a meta-analysis. Trauma Violence Abuse 2020; 21(5): 1011-1028.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

6 Nöthling J, Abrahams N, Jewkes R, Mhlongo S, Lombard C, Hemmings SMJ, Seedat S. Risk and protective factors affecting the symptom trajectory of posttraumatic stress disorder post-rape. J Affect Disord 2022; 309: 151-164.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

7 Möller AT, Bäckström T, Söndergaard HP, Helström L. Identifying risk factors for PTSD in women seeking medical help after rape. PLoS ONE 2014; 9(10): e111136.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

8 American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5-TR. 5th edn. text revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2022. Available at https://psychiatryonline.org/doi/book/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787 [cited 20 February 2025]

9 Montgomery E, Pope C, Rogers J. The re-enactment of childhood sexual abuse in maternity care: a qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015; 15(1): 194.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

10 TeBockhorst SF, O’Halloran MS, Nyline BN. Tonic immobility among survivors of sexual assault. Psychol Trauma 2015; 7(2): 171-178.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

11 Troutman M, Chacko S, Petras L, Laufer MR. Informed care for the gynecologic day surgical patient with a history of sexual trauma. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2022; 35(1): 3-6.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

12 Crosby SS, Mashour GA, Grodin MA, Jiang Y, Osterman J. Emergence flashback in a patient with posttraumatic stress disorder. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2007; 29(2): 169-171.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

14 Porges SW. Polyvagal theory: a science of safety. Front Integr Neurosci 2022; 16: 871227.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

15 Better Health Channel. Patient-centred care explained. Victoria State Government: Department of Health; 2024. Available at https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/servicesandsupport/patient-centred-care-explained# [cited 16 October 2024]

16 Heywood S, Bunzli S, Dillon M, Bicchi N, Black S, Hemus P, Bogatek E, Setchell J.. Trauma-informed physiotherapy and the principles of safety, trustworthiness, choice, collaboration, and empowerment: a qualitative study. Physiother Theory Pract 2024; 41(1): 153-168.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

17 Kezelman C, Stavropoulos P. Talking about trauma: Guide to conversations, screening and treatment for primary health care providers. Blue Knot Foundation: National Centre of Excellence for Complex Trauma; 2018. Available at https://www.pc.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/241752/sub047-mental-health-attachment3.pdf

18 Chen LP, Murad MH, Paras ML, Colbenson KM, Sattler AL, Goranson EN, Elamin MB, Seime RJ, Shinozaki G, Prokop LJ, Zirakzadeh A. Sexual abuse and lifetime diagnosis of psychiatric disorders: systematic review and meta-analysis. Mayo Clin Proc 2010; 85(7): 618-629.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

19 Arditte Hall KA, Healy ET, Galovski TE. The sequelae of sexual assault. In: O’Donohue WT, Schewe PA, editors. Handbook of sexual assault and sexual assault prevention. Springer International Publishing; 2019. pp. 277–292. 10.1007/978-3-030-23645-8_16

20 Lalchandani P, Lisha N, Gibson C, Huang AJ. Early life sexual trauma and later life genitourinary dysfunction and functional disability in women. J Gen Intern Med 2020; 35(11): 3210-3217.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

21 Paras ML, Murad MH, Chen LP, Goranson EN, Sattler AL, Colbenson KM, Elamin MB, Seime RJ, Prokop LJ, Zirakzadeh A. Sexual abuse and lifetime diagnosis of somatic disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2009; 302(5): 550-561.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

22 Möller A, Sondergaard HP, Helstrom L. Tonic immobility during sexual assault – a common reaction predicting post-traumatic stress disorder and severe depression. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2017; 96(8): 932-938.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

23 Imhoff LR, Liwanag L, Varma M. Exacerbation of symptom severity of pelvic floor disorders in women who report a history of sexual abuse. Arch Surg 2012; 147(12): 1123-1129.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

24 Nanavaty N, Thompson CG, Meagher MW, McCord C, Mathur VA. Traumatic life experience and pain sensitization: meta-analysis of laboratory findings. Clin J Pain 2023; 39(1): 15-28.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

25 Levesque A, Riant T, Ploteau S, Rigaud J, Labat J-J, Convergences PP Network. Clinical criteria of central sensitization in chronic pelvic and perineal pain (Convergences PP Criteria): elaboration of a clinical evaluation tool based on formal expert consensus. Pain Med 2018; 19(10): 2009-2015.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

26 Woolf CJ. Pain amplification—A perspective on the how, why, when, and where of central sensitization. J Appl Biobehav Res 2018; 23(2): e12124.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

27 World Health Organization. ICD-11: International classification of diseases (11th revision). WHO; 2022. Available at https://icd.who.int/browse/2024-01/mms/en#1581976053 [cited 16 October 2024]

28 Keay KA, Bandler R. Parallel circuits mediating distinct emotional coping reactions to different types of stress. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2001; 25(7–8): 669-678.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

29 Terpou BA, Harricharan S, McKinnon MC, Frewen P, Jetly R, Lanius RA. The effects of trauma on brain and body: a unifying role for the midbrain periaqueductal gray. J Neurosci Res 2019; 97(9): 1110-1140.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

30 van der Kolk BA, van der Hart O. The intrusive past: the flexibility of memory and the engraving of trauma. American Imago 1991; 48(4): 425-454.

| Google Scholar |

31 Marx BP, Forsyth JP, Gallup GG, Fusé T, Lexington JM. Tonic immobility as an evolved predator defense: implications for sexual assault survivors. Clin Psychol 2008; 15(1): 74-90.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

32 Kalaf J, Coutinho ESF, Vilete LMP, Luz MP, Berger W, Mendlowicz M, Volchan E, Andreoli SB, Quintana MI, de Jesus Mari J, Figueira I. Sexual trauma is more strongly associated with tonic immobility than other types of trauma – a population based study. J Affect Disord 2017; 215: 71-76.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

33 Heidt JM, Marx BP, Forsyth JP. Tonic immobility and childhood sexual abuse: a preliminary report evaluating the sequela of rape-induced paralysis. Behav Res Ther 2005; 43(9): 1157-1171.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

34 Porges SW, Peper E. When not saying NO does not mean yes: psychophysiological factors involved in date rape. Biofeedback 2015; 43(1): 45-48.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

35 Kearney BE, Terpou BA, Densmore M, Shaw SB, Théberge J, Jetly R, McKinnon MC, Lanius RA. How the body remembers: examining the default mode and sensorimotor networks during moral injury autobiographical memory retrieval in PTSD. Neuroimage Clin 2023; 38: 103426.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

36 Zhang H, Zhu Z, Ma W-X, Kong L-X, Yuan P-C, Bu L-F, Han J, Huang Z-L, Wang Y-Q. The contribution of periaqueductal gray in the regulation of physiological and pathological behaviors. Front Neurosci 2024; 18: 1380171.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

37 Kim MC, Fricchione GL, Akeju O. Accidental awareness under general anaesthesia: incidence, risk factors, and psychological management. BJA Educ 2021; 21(4): 154-161.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

38 van der Kolk BA. The body keeps the score: memory and the evolving psychobiology of posttraumatic stress. Harv Rev Psychiatry 1994; 1(5): 253-265.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

39 Cusack K, Jonas DE, Forneris CA, Wines C, Sonis J, Middleton JC, Feltner C, Brownley KA, Olmsted KR, Greenblatt A, Weil A, Gaynes BN. Psychological treatments for adults with posttraumatic stress disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2016; 43: 128-141.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

40 Payne P, Levine P, Crane-Godreau MA. Somatic experiencing: using interoception and proprioception as core elements of trauma therapy. Front Psychol 2015; 6: 93.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

41 Rash JA, Aguirre-Camacho A, Campbell TS. Oxytocin and pain: a systematic review and synthesis of findings. Clin J Pain 2014; 30(5): 453-462.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

42 Ellingsen D-M, Wessberg J, Chelnokova O, Olausson H, Laeng B, Leknes S. In touch with your emotions: oxytocin and touch change social impressions while others’ facial expressions can alter touch. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2014; 39(1): 11-20.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

43 Kearney BE, Corrigan FM, Frewen PA, Nevill S, Harricharan S, Andrews K, Jetly R, McKinnon MC, Lanius RA. A randomized controlled trial of Deep Brain Reorienting: a neuroscientifically guided treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder. Eur J Psychotraumatol 2023; 14(2): 2240691.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

44 Frawley H, Shelly B, Morin M, Bernard S, Bø K, Digesu GA, Dickinson T, Goonewardene S, McClurg D, Rahnama’i MS, Schizas A, Slieker-Ten Hove M, Takahashi S, Voelkl Guevara J. An International Continence Society (ICS) report on the terminology for pelvic floor muscle assessment. Neurourol Urodynamics 2021; 40(5): 1217-1260.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

45 Morris LS, McCall JG, Charney DS, Murrough JW. The role of the locus coeruleus in the generation of pathological anxiety. Brain Neurosci Adv 2020; 4: 239821282093032.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

46 Benarroch EE. Locus coeruleus. Cell Tissue Res 2018; 373(1): 221-232.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

47 Rogers CR. The necessary and sufficient conditions of therapeutic personality change. J Consul Clin Psychol 1992; 60(6): 827-832.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

48 Aces aware: Screen. Treat. Heal. Adverse Childhood Experience Questionnaire for Adults. California Surgeon General’s Clinical Advisory Committee; 2022. Available at https://www.acesaware.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/ACE-Questionnaire-for-Adults-Identified-English-rev.7.26.22.pdf [cited 17 October 2024]

51 Depression, Anxiety, Stress Scales (DASS). Psychology Foundation of Australia; 2023. Available at https://dass.psy.unsw.edu.au [updated 10 October 2024, cited 17 Oct 2024]

52 Mayer TG, Neblett R, Cohen H, Howard KJ, Choi YH, Williams MJ, Perez Y, Gatchel RJ. The development and psychometric validation of the central sensitization inventory. Pain Pract 2012; 12(4): 276-285.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

53 Rosen CB, Brown C, Heiman J, Leiblum S, Meston C, Shabsigh R, Ferguson D, D’Agostino R, Jr. The female sexual function index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther 2000; 26(2): 191-208.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

54 DeRogatis L, Clayton A, Lewis-D’Agostino D, Wunderlich G, Fu Y. Validation of the female sexual distress scale-revised for assessing distress in women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder. J Sex Med 2008; 5(2): 357-364.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

55 Raja S, Hasnain M, Hoersch M, Gove-Yin S, Rajagopalan C. Trauma informed care in medicine: current knowledge and future research directions. Fam Community Health 2015; 38(3): 216-226.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

56 Crockett R. How belly breathing benefits your body, mind. Mayo Clinic Q&A: Tribune Content Agency LLC; 2024. Available at https://www.proquest.com/other-sources/how-belly-breathing-benefits-your-body-mind/docview/3031587684/se-2 [cited 17 October 2024]

57 Liu H, Wiedman CM, Lovelace-Chandler V, Gong S, Salem Y. Deep diaphragmatic breathing—anatomical and biomechanical consideration. J Holist Nurs 2024; 42(1): 90-103.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

58 Forbes R, Elkins MR. Patient education. J Physiother 2024; 70(2): 85-87.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

59 Weinreb L, Savageau JA, Candib LM, Reed GW, Fletcher KE, Lee Hargraves J. Screening for childhood trauma in adult primary care patients: a cross-sectional survey. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2010; 12(6): PCC.10m00950.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

60 Gordinier ME, Shields LBE, Davis MH, Cagata S, Lorenz DJ. Impact of screening for sexual trauma in a gynecologic oncology setting. Gynecol Obstet Invest 2021; 86(5): 438-444.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

61 Information and Privacy Commission New South Wales. Fact Sheet. Consent. Available at https://www.ipc.nsw.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-06/Fact_Sheet_Consent_June_2023.pdf [cited 16 October 2024]

62 Delany C, Frawley H. A process of informed consent for student learning through peer physical examination in pelvic floor physiotherapy practice. Physiotherapy 2012; 98(1): 33-39.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

63 Copnell G. Informed consent in physiotherapy practice: it is not what is said but how it is said. Physiotherapy 2018; 104(1): 67-71.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

64 Padmanabhanunni A, Gqomfa N. “The Ugliness of It Seeps into Me”: experiences of vicarious trauma among female psychologists treating survivors of sexual assault. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022; 19(7): 3925.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

65 Quitangon G. Vicarious trauma in clinicians: fostering resilience and preventing burnout. The Psychiatric Times 2019; 36(7): 18-19.

| Google Scholar |

67 Hallinan S, Shiyko MP, Volpe R, Molnar BE. Reliability and validity of the vicarious trauma organizational readiness guide (VT-ORG). Am J Community Psychol 2019; 64(3–4): 481-493.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

68 Isobel S, Thomas M. Vicarious trauma and nursing: an integrative review. Int J Ment Health Nurs 2022; 31(2): 247-259.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

69 Australian Bureau of Statistics. Sexual violence – victimisation. Canberra: ABS; 2021. Available at https://www.abs.gov.au/articles/sexual-violence-victimisation [cited 5 September 2024]

70 Data Pandas. Rape statistics by country. Available at https://www.datapandas.org/ranking/rape-statistics-by-country [cited 17 Ocotober 2024]

71 McGrath RL, Parnell T, Verdon S, Pope R. “We take on people’s emotions”: a qualitative study of physiotherapists’ experiences with patients experiencing psychological distress. Physiother Theory Pract 2024; 40(2): 304-326.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

72 Cromie JE, Robertson VJ, Best MO. Occupational health and safety in physiotherapy: guidelines for practice. Aust J Physiother 2001; 47(1): 43-51.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

73 de Castro AB. ‘Hierarchy of controls’: providing a framework for addressing workplace hazards. Am J Nurs 2003; 103(12): 104.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

74 Guidi J, Lucente M, Sonino N, Fava GA. Allostatic load and its impact on health: a systematic review. Psychother Psychosom 2021; 90(1): 11-27.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

75 Higginbotham JA, Markovic T, Massaly N, Moron JA. Endogenous opioid systems alterations in pain and opioid use disorder. Front Syst Neurosci 2022; 16: 1014768.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

76 Pal MM. Glutamate: the master neurotransmitter and its implications in chronic stress and mood disorders. Front Hum Neurosci 2021; 15: 722323.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

77 Goodall E. Interoception and mental wellbeing in autistic people. National Autistic Society; 2022. Available at https://www.autism.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/professional-practice/interoception-wellbeing#:~:text=Interoception%20is%20an%20internal%20sensory,pulling%20sensation%20in%20their%20abdomen [cited 4 January 2025]

78 Schimmelpfennig J, Topczewski J, Zajkowski W, Jankowiak-Siuda K. The role of the salience network in cognitive and affective deficits. Front Hum Neurosci 2023; 17: 1133367.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

79 Benarroch E. What are the functions of the superior colliculus and its involvement in neurologic disorders? Neurology 2023; 100(16): 784-790.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Appendix 1.Short list of definitions

| Definition | ||

|---|---|---|

| Allostatic load | Represents the cumulative toll of ongoing day-to-day stress and life occurrences. 74 Over time chronic stress can burden the body as a system and impact ability to respond adaptively and flexibly if life’s challenges exceed and overwhelm individual coping. 74 | |

| Dorsal vagal complex (DVC) | In humans the DVC is involved in digestion and taste, as well as hypoxic reactions. 13 ‘The DVC provides primary neural control of subdiaphragmatic visceral organs…Hypoxia or perceived loss of oxygen resources appears to be the main stimulus that triggers the DVC. Once triggered, severe bradycardia and apnoea are observed, often in the presence of defecation’ (p. 159, 160) 13 | |

| Endogenous opioids | Endogenous opioids provide the body with its own internal form of pain relief. In addition to providing analgesia, endogenous opioids regulate the autonomic nervous system. They are involved in immune response, functioning of the gastrointestinal system, and have a role in mood, motivation, learning, memory and reward processing. 75 | |

| Excitatory amino acids | Glutamate and aspartate are examples of excitatory amino acids. Glutamate is the brains most abundant excitatory neurotransmitter, with influence on mood, cognition and memory. 76 | |

| Interoception | Interoception relates to noticing and attending to the ‘felt’ visceral or physical sensations within the body. 40, 77 | |

| Salience network (SN) | The SN incorporates the anterior insula and the dorsolateral cingulate cortex. It operates like a switch, dynamically shifting focus between the inner ‘self’ world and the outer task-oriented environment, according to pertinent and competing stimuli in the internal and external environment. It plays a role in pain processing, motivation, reward and emotion. 78 | |

| Superior colliculus (SC) | The SC, located in the midbrain, is a sensorimotor hub of sorts with multiple inputs, outputs and internal circuits; designed to detect, localise and orient towards salient stimuli. 79 Visual and spatial input is received in the outer layer of the SC directly from the retina. Excitatory auditory stimuli and somatosensory inputs are received in the deep and middle layers of the SC. 79 The SC has multiple ascending projections (one such projection is to the amygdala), and descending projections (for example, to the reticular formation, a key regulator of arousal/consciousness). The SC also receives modulatory inputs from several brainstem regions including the locus coeruleus. This hub of interconnectivity supports the SC’s primary role of ‘orienting’, it uses perceptual decision making to organise visuospatial attention and motor responses. 79 | |

| Fasciculation | Individual muscle twitches at rest or following contraction of a muscle. 44 |