Implications of varroa mite establishment for Australian plants and their persistence

Tom Le Breton A * , Amy-Marie Gilpin B C , Chantelle Doyle A and Mark K.J. Ooi

A * , Amy-Marie Gilpin B C , Chantelle Doyle A and Mark K.J. Ooi  A

A

A

B

C

Abstract

The European honeybee (Apis mellifera) is a highly abundant introduced pollinator with widely established feral populations across a large proportion of Australia. Both managed and feral populations contribute significantly to the pollination of many native plant species but have also disrupted native plant-pollinator dynamics. Varroa mite (Varroa destructor), a parasite associated with the collapse of feral or unmanaged European honeybee populations globally, has recently become established in Australia and will inevitably spread across the country. If feral honeybee populations decline significantly, there may be a range of effects on Australian native plant species, including pollination dynamics and seed set. This would have potential implications for the risks faced by native species, particularly those already threatened. However, the exact effects of a decline in feral honeybees on native plants are uncertain as the role of honeybees in Australian ecosystems is poorly understood. We identify potential consequences of the spread of varroa mite and highlight the large knowledge gaps that currently limit our understanding of the subsequent impacts on the Australian flora.

Keywords: invasion ecology, plant conservation, plant ecology, pollination, pollination biology, Varroa destructor.

Introduction

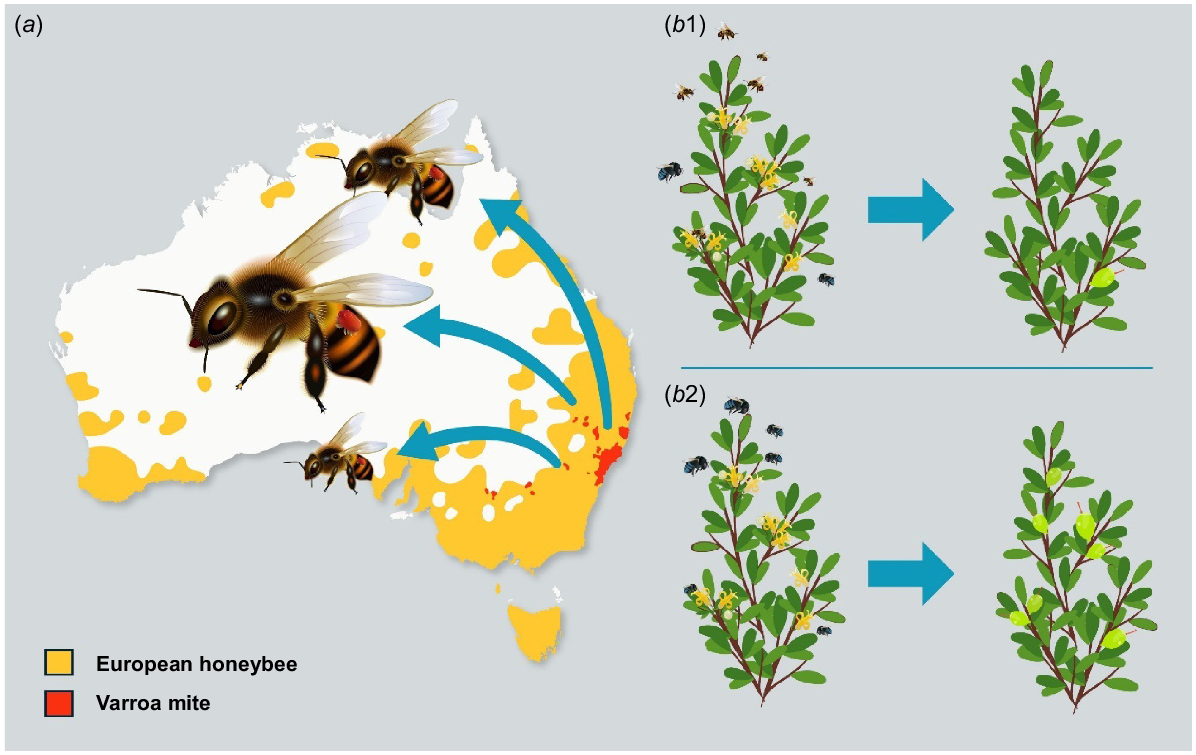

Until recently, Australia was the last significant honey producing country to be free of the varroa mite (Varroa destructor) (Iwasaki et al. 2015), a major parasite of European honeybee (Apis mellifera; hereafter, honeybee) colonies (Fig. 1a). The varroa mite has been found to cause colonies to collapse and has been linked to unmanaged feral honeybee declines globally (Martin 1998; Iwasaki et al. 2015). Several past incursions have been successfully eradicated from Australia (Outbreak, Australian Government 2023). However, in June 2022 varroa mite was detected in New South Wales (NSW) and, following an intensive emergency response to eradicate the parasite, the NSW Department of Primary Industries announced that the emergency response strategy was transitioning from eradication to management of the mite (NSW DPI 2023) on 19 September 2023. This transition reflects the limited likelihood of eradication (Iwasaki et al. 2015) and the current likely permanent establishment of the varroa mite in the Australian environment. The consequences of the varroa mite becoming established in Australia will be significant for the apicultural, horticultural and agricultural industries that rely on both managed and feral honeybees for honey production and pollination services (DAFF 2011). However, the impact of an associated decline in feral honeybee populations on native plant reproduction is uncertain, partly due to the lack of clarity about the role of honeybees in Australian ecosystems.

(a) The current indicative distribution of European honeybee (Apis mellifera) (yellow) and varroa mite (Varroa destructor) (red) in Australia, and the potential for spread via infected European honeybees. (b) Example of a potential benefit arising from the decline in European honeybees following the arrival of the varroa mite. (b1) Pre-varroa mite: Ineffective pollination of a native plant species by European honeybee due to competitive exclusion of more effective native pollinators. (b2) Post-varroa mite: Effective pollination of a native plant species due to a return to more natural pollination dynamics following the decline in European honeybees. Illustration by Juan Camilo.

The establishment of managed colonies of honeybees in Australia and subsequent spread of feral honeybee populations throughout the country has affected native plant-pollinator dynamics (Paton 1993; Prendergast et al. 2023). There are no accurate estimates of the total feral honeybee population in Australia, however studies in southern Australia have found that densities vary with habitat (Oldroyd et al. 1994, 1997; Paton 1996; Goodman and Hepworth 2004) and can range from 0.11 colonies/km2 (Paton, Jansen and Oliver, unpubl. data, from Paton (1996)) to 148 colonies/km2 (Oldroyd et al. 1997), the highest observed honeybee density in the world (Visick and Ratnieks 2023). Given that the honeybees can form colonies of up to 50,000 individuals (Goulson 2003), population size likely numbers in the hundreds of millions of individuals nationally. Consequently, feral honeybees are believed to account for a significant proportion of pollinator visitations to native flora due to the habit of polylectic foraging (Goulson 2003). On this basis, honeybees are assumed to likely be influencing pollination and competition with other flower visitors (Paton 2000; Cunningham et al. 2022). The arrival of varroa mites in new regions typically results in a loss of ~95% of feral honeybee populations within 3–4 years (DAFF 2011), followed by a moderate rebound up to 10 years later (Loper et al. 2006; Locke 2016). The same may be expected to occur in Australia.

The loss of such a large number of potential pollinators could have major implications, particularly for species predominantly visited by honeybees or plant species that are rare or threatened (Chapman et al. 2023). Honeybees are likely able to effectively pollinate some native plant species (England et al. 2001, Hermansen et al. 2014), particularly generalist flowers such as those that have open or easily accessible floral reproductive structures (Page et al. 2021). Honeybees are common visitors to a wide range of native species (Prendergast and Ollerton 2022; Table 1) and have been reported to be the numerically dominant floral visitor to some native plant species in particular vegetation communities (e.g. several heathland species Gilpin et al. 2019; Elliott et al. 2021). Honeybees have also been observed to be the dominant visitor and consequently near exclusive pollinator for individual populations of particular species (e.g. Banksia brownii, Day et al. 1997; Dillwynia juniperina (Gross 2001), Avicennia marina, Hermansen et al. 2014; and Zieria granulata, Lopresti et al. 2023a, 2023b). However, international research suggests that honeybees, alongside other exotic pollinators, are generally less effective pollinators than native pollinators (Debnam et al. 2021; Page et al. 2021) that may have co-evolved with the plants visited.

| Family | # of Genera | # of Species | % of species nationallyA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Myrtaceae | 36 | 127 | 5.2 | |

| Proteaceae | 16 | 85 | 7.4 | |

| Fabaceae | 21 | 84 | 3.1 | |

| Asteraceae | 23 | 57 | 4.9 | |

| Ericaceae | 11 | 32 | 5.4 | |

| Goodeniaceae | 5 | 29 | 6.4 | |

| Orchidaceae | 10 | 22 | 1.4 | |

| Other families (n = 66) | 169 | 281 | 2.9 | |

| All families | 291 | 717 | 3.2 |

The named families are the seven most commonly observed families across the studies reviewed while the remainder grouped into ‘Other families’ contain fewer than 20 species each. The inclusion of species in this list does not mean that these were visited or pollinated by European honeybees, only that the species were noted during studies in which pollinators, including European honeybees, were observed to be foraging on at least one species. This is a non-exhaustive list of observations of European honeybees foraging on native flora but represents a selection of 55 published studies that included observations of species level visitations. Further details on the list of species and studies are included in Supplementary Table S1, alongside the methods for selecting studies in Supplementary material 1.

In Australia, existing research reflects global trends. The impacts of honeybees on the pollination and seed production of native flora have been observed to range from beneficial to detrimental (Table 2), contrary to early assumptions that honeybees were primarily providing additional and beneficial pollination services (Paton 1993). However, while knowledge of the traits, life history and seed ecological characteristics for a large proportion of the Australian flora is rapidly increasing (Falster et al. 2021), our understanding of pollination systems and the effectiveness of honeybees as pollinators remains limited (Chapman et al. 2023; Table 1). For example, we have very little understanding of the ability of honeybees to effectively pollinate many of the native Australian species known to be visited, the potential subsequent impacts on plant mating systems (but see England et al. 2001), seed quality (but see Gilpin et al. 2017) or plant fitness. Additionally, estimates of the floral resources being removed from the system or the potential for pollen limitation occurring in these systems has not been established. This may be of particular concern for plant communities and species that are favoured by the apicultural industry (for honey production), such as heathland and yellow box (Eucalyptus melliodora) woodland (Table 1). The establishment and spread of the varroa mite provides a strong impetus for collation of the data we do have and, using these, to set research goals to identify the likely effects of declines driven by varroa mite in feral honeybees and where threats to native species and the associated ecosystems are most likely to occur.

| Reference | Floral study species | Study pollinators | Effect of European honeybee | Reproductive elements affected | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ayre et al. (2020) | Anigozanthos manglesii | Birds and European honeybees | Negative | Reduced fruit and seed set | |

| Celebrezze and Paton (2004) | Brachyloma ericoides | Birds and European honeybees | Negative | Inefficient pollination and pollen theft | |

| Day et al. (1997) | Banksia brownii | Birds, mammals and European honeybees | Negative | Inefficient pollination | |

| Gilpin et al. (2014) | Acacia ligulata | Native bees and European honeybees | Positive | Higher rate of visitation and pollen transport than in native bees | |

| Gilpin et al. (2017) | Banksia ericifolia | Birds, mammals and European honeybees | Neutral | Altered pattern of pollen transfer but no effect on seed set or quality | |

| Gross (2001) | Dillwynia juniperina | Native bees and European honeybees | Positive | Effective pollination | |

| Hermansen et al. (2014) | Avicennia marina | European honeybees | Positive | Dominant visitor and effective pollination | |

| Hingston et al. (2004) | Eucalyptus globulus subsp. globulus | Swift Parrot (Lathamus discolor), European Honeybee, exotic bumblebee (Bombus terrestris) | Negative | Inefficient pollinators, reduced seed set | |

| Lopresti et al. (2023a) | Zieria granulata | All native and non-native visitors | Positive | Effective pollination | |

| Ottewell et al. (2009) | Eucalyptus camaldulensis and E. leucoxylon | Insects and birds | Positive | Facilitate pollination of isolated trees | |

| Richardson et al. (2000) | Grevillea mucronulata and G. sphacelata | Honeyeaters and European honeybees | Negative | Reduced outcrossing and seed set | |

| Whelan et al. (2009) | Grevillea macleayana | Birds and European honeybees | Negative | Dominant visitor and inefficient pollination | |

| Wawrzyczek et al. (2024) | Banksia catoglypta | Non-flying mammals, birds and European honeybees | Positive | Effective pollination | |

| Wawrzyczek, Holmes and Hoebee (2023) | Grevillea bedggoodiana | Non-flying mammals, birds and European honeybees | Positive | Replacement of effective pollination services by declining vertebrate pollinators |

These studies were selected as representative examples of the breadth of effects that have been documented, and the distribution of positive and negative effects.

Potential impacts of honeybee decline

One of the challenges faced by Australian plant ecologists and conservationists as varroa mites continue to spread will be identifying which species have been beneficially or detrimentally impacted by the decline in honeybees and identifying which actions, if any, are required to address the impacts accordingly. The literature on honeybee effects on native plants in Australia is relatively sparse. A selection of 55 studies (Table 1) that included observations of floral visitations on across 717 native plant species accounts for only 3.2% of the Australian flora. Additionally, these observations are dominated (~50% of species observed) by only four main families: Myrtaceae, Proteaceae Fabaceae and Asteraceae (Table 1). Consequently, there is considerable uncertainty as to how most of the Australian flora is impacted by honeybees and how species may respond to the potential honeybee decline as a result of varroa mite. While most species are unlikely to be impacted by the loss of honeybees, our limited understanding of the role as pollinators and interactions with most species means that any species could be and certainly many will be impacted.

Honeybees have been found to affect native flora through a range of mechanisms (Table 3). Notably, honeybees have been observed to disrupt plant pollinator dynamics through competition with both native insect (Gross and Mackay 1998) and vertebrate pollinators (Paton 1993), and influence plant-pollinator networks (Prendergast and Ollerton 2022). Altered plant pollinator dynamics can have positive effects, with honeybees benefitting some species through increased pollinator visitation (Gilpin et al. 2017) and greater connectivity between isolated individuals in fragmented landscapes (Ottewell et al. 2009), while a recent network analysis found that feral honeybees may play a particularly important role as pollinators, alongside native pollinators, throughout late winter in the Howell Shrublands endangered ecological community (Whitehead 2018). However, other plant species have been negatively impacted by honeybees, with reduced seed set (Whelan et al. 2009) and increased inbreeding resulting from the tendency of honeybees to primarily forage within an individual plant (England et al. 2001; Ayre et al. 2020). Additionally, honeybees may also transfer less pollen than native pollinators (Gross and Mackay 1998), engage in pollen theft (Jean 2005) and remove previously deposited pollen from stigmata (Gross and Mackay 1998). The impending decline in feral honeybees may mean that many of these interactions, beneficial and detrimental, will cease or be greatly diminished. The possible outcomes for native flora range from species that may benefit emerging in groups that are more effectively pollinated by native pollinators, to negative outcomes for species that currently benefit from the abundance or movement patterns of honeybees, with a large portion of plants most likely having an overall neutral response.

| Potential outcome | Functional group | Mechanism | Examples | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive A | Self-incompatible native plant species primarily visited by honeybees | Increased native pollinator visitation and increased outcrossing with neighbouring plants | Paton (1993) and Celebrezze (2002) | |

| Positive | Bird-pollinated species impacted by competitive exclusion and resource theft by European honeybees | Increased outcrossing via longer distance pollen transfer via coevolved vertebrate pollinators; potentially increased abundance of competing bird pollinators; larger quantities and diversity of pollen transferred by larger pollinators (birds) able to collect from more plants | Paton (2000), Celebrezze and Paton (2004), Whelan et al. (2009) and Ayre et al. (2020) | |

| Positive | Species with flowers in which the anther structure requires specialist pollinators | Increased abundance and visitation of native specialist pollinators | Houston and Ladd (2002) and Passarelli and Cocucci (2006) | |

| Positive | Species that are susceptible to pollen-raiding (i.e. the removal of previously deposited pollen from stigmata) | Reduced pollen theft, increased pollination | Gross and Mackay (1998) | |

| Positive | Species competing with or threatened by weeds facilitated by honeybees | Loss of a key weed pollinator resulting in lower fecundity and slowed spread | Goulson and Derwent (2004), Gross et al. (2010) and Simpson et al. (2005) | |

| Positive | Threatened species that are ineffectively pollinated due to competitive exclusion by honeybees | Return to more natural pollination dynamics | Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts (DEWHA) (2008) | |

| Negative A | Generalist pollinated species that are frequented and effectively pollinated by European honeybees | Decline in pollination if native pollinator numbers take time to rebound | Gilpin et al. (2017) | |

| Negative | Species with fragmented populations in fragmented landscapes, such as paddock trees in agricultural land | Reduction in the connectivity provided by European honeybee pollination | Ottewell et al. (2009) and Eakin-Busher et al. 2020 | |

| Negative | Winter flowering species that benefit from European honeybee pollination | Reduced winter pollination by native pollinators that are less active in cold conditions | Whitehead (2018) |

The outcomes of each mechanism are considered potential outcomes because there will likely be complex interactions between pollinators and specific plants, and uncertainty about response lag time. These potential impacts are theoretical only and the recent varroa mite invasion provides an opportunity to explore unprecedented or opposing effects to those theorised here. Functional group classification provides a framework for species or community specific investigation.

The effects of varroa mite establishment on native flora will also depend on how native insect pollinator populations respond to the decline in feral honeybees. There is growing global evidence of a range of negative associations between honeybees and native bee species (Iwasaki and Hogendoorn 2022), particularly generalists (Henry and Rodet 2018), including reduced species richness (Prendergast et al. 2023), reduced fecundity (Paini and Roberts 2005) and plant avoidance by native bees when feral honeybees are present (Gross 2001). The collapse of feral honeybee populations due to varroa mite may therefore signal a reversal of fortunes for many native pollinator species. This in turn may have direct benefits for plant species and moderate some of the more detrimental impacts that honeybees have had. For example, plant species that have come to depend on the honeybee for effective pollination may have native pollinators that could fill the shortfall in pollination services.

Native insect pollinators are facing a range of threats including land clearing and pesticide use (Dorey et al. 2021; Marsh et al. 2022; Woinarski et al. 2024). However, while declines have been observed globally (Potts et al. 2010; Wagner 2020) and are generally assumed to be occurring in Australia (e.g. Batley and Hogendoorn 2009), these have not been well documented (Pyke et al. 2023; Woinarski et al. 2024). This reflects both known gaps in our understanding of insect extinction risk (Marsh et al. 2022; Woinarski et al. 2024) and the lack of appropriate baseline data for past pollinator communities. Consequently, native insect pollinator populations seem likely to have experienced declines. However, predicting how much need or capacity might exist for native pollinators to increase in richness and abundance, and fill the gap that will be left by feral honeybees is difficult to predict due to the uncertainty. While the increased abundance of floral resources freed up by the loss of honeybees may accelerate the recovery of native pollinators, the overall capacity to recover is unknown. There will likely be a lag of several years during which feral honeybee populations collapse and native pollinators, such as bees, flies and wasps, increase.

Assuming that the loss of feral honeybees does create a shortfall in pollination services, pollination and seed set may be depressed in some native plant species during this recovery period. This could lead to an initial decline in reproductive output, and a short-term demographic plateau or dip. While most species will be able to tolerate a short-term decline in reproduction, species that are already threatened or persisting in fragmented populations may require intervention to facilitate continued seed production (e.g. Banksia brownii, Day et al. 1997). Species with short life cycles and short-lived seed banks, such as many annuals, may also experience sharp initial declines if reproductive output and subsequent recruitment is negatively impacted by the loss of feral honeybees. An additional layer of risk may emerge for imperilled plant species for which native pollinators have been lost and the pollinating role entirely replaced by honeybees (e.g. Dick 2001; Eakin-Busher et al. 2020). Alternatively, there may be risk to those that rely on services from feral honeybees that are unlikely to be replaced by native pollinators, for example, species with fragmented populations in modified and degraded landscapes.

The effects of declines in feral honeybees on native plant species are likely to have ramifications for broader vegetation communities and ecosystems at large. The extent of these effects is also unknown and may be more difficult to predict but is worth consideration, particularly where feral honeybees are the dominant pollinators of remnant ecosystem fragments. One positive outcome in this category may be the effect on weed species. Honeybees facilitate the spread of several invasive weed species including broom (Cytisus scoparius, Simpson et al. 2005), Phyla canescens (Gross et al. 2010) and lantana (Lantana camara, Goulson & Derwent 2004). The loss of a key weed pollinator could provide a competitive advantage for native species and may slow the spread of some weed species. Finally, the distribution of effects on native flora and ecosystems may depend on the relative abundance of feral hives managed honeybees. In regions with a high density of feral colonies, the effect may be more pronounced, whereas the loss of feral honeybees may be offset by the continued presence of managed hives in agricultural and honey-production regions.

Research gaps and priorities

The establishment of the varroa mite in New Zealand prompted a series of recommendations for the Australian context (Iwasaki et al. 2015). Among these were calls for increased research into pollinator interactions and pollination services pre-and post-varroa mite, ideally undertaken as long-term studies to account for annual and seasonal variation. A better understanding of pre-varroa mite plant-pollinator interactions will allow for clearer comparisons in the aftermath, as pollinator communities potentially become less dominated by honeybees. The window for measuring the effect of honeybees on the reproduction of native plant species is rapidly closing due to the establishment of varroa mite. During this time, monitoring pollination systems and success in native flora, particularly for threatened species to detect potential declines before these become difficult to reverse, will be critical. Monitoring of both common and rare species can be prioritised using existing knowledge, to compile a list of species with traits that may make these more sensitive to the loss of the introduced pollinator. These data could be integrated to fill gaps within existing open databases such as AusTraits (https://austraits.org/) (Falster et al. 2021).

The numerous threats currently facing the Australian flora, including climate change, land clearing, altered fire regimes and introduced species and pathogens (Ward et al. 2021) will likely interact with the loss of feral honeybees. For example, continued land clearing may increase the number of species at risk of fragmentation and there may be subsequent genetic isolation of populations that might previously have remained connected via feral honeybee pollination. Another prevalent threat in Australia is altered fire regimes, and both high frequency fires (Carbone et al. 2019) and high severity fires (Dorey et al. 2021) have been observed to have a negative impact on pollinator populations. If the short-term loss of feral honeybees limits seed production, post-fire recovery of native plant species with generalist pollination strategies may be impaired due to reduced pre-fire seed production. A similar reduction may occur in post-fire pollination of post-fire flowering species, such as the iconic grass trees (Xanthorrhea sp.) and pink flannel flowers (Actinotus forsythii). Pollination by bee species, particularly social species, typically increases following fires while remaining stable or decreasing for most other major groups of pollinators (Carbone et al. 2024). This suggests that honeybees disproportionately contribute to post-fire pollination and decline may lead to shortfalls in post-fire pollination, again depending on the ability of native bees to recover. Climate change-driven increases in other disturbances, such as flooding and drought, may similarly impact both pollinators and plants, and interact with the loss of feral honeybees via similar mechanisms to fire.

Conclusion

The establishment of the varroa mite is causing many native Australian plant species to face an unprecedented decline in what has become a numerically dominant flower visitor, the invasive honeybee. The expected decline in honeybees due to varroa mite will provide both opportunities and challenges for which Australian plant conservationists and ecologists need to prepare. However, accurately predicting how native flora will be affected is difficult due to the limited research attention given to pollination and the effects of the honeybee. The little knowledge available can, however, provide a starting point from which to identify potentially sensitive species and focus research efforts. The establishment of the varroa mite provides a rare opportunity for both research and conservation (Iwasaki et al. 2015) in that the immediate consequences of the invasion are foreseeable, and efforts to limit the spread of the mite will allow time for the assembly of research programs and requisite conservation measures in currently varroa mite-free regions. In particular, this shift in dominant pollinators may provide a novel window into plant-pollinator dynamics of the past, and an opportunity for experiments to clarify the role of honeybees, and compare baseline surveys of seed set and population genetics during the pre-varroa mite era against the largely honeybee-free periods to come.

Conflicts of interest

Mark Ooi is an Editor of Australian Journal of Botany. To mitigate this potential conflict of interest, this Editor had no editor-level access to this manuscript during peer review. The author(s) have no further conflicts of interest to declare.

References

Ayre BM, Roberts DG, Phillips RD, Hopper SD, Krauss SL (2020) Effectiveness of native nectar-feeding birds and the introduced Apis mellifera as pollinators of the kangaroo paw, Anigozanthos manglesii (Haemodoraceae). Australian Journal of Botany 68(1), 14-25.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Batley M, Hogendoorn K (2009) Diversity and conservation status of native Australian bees. Apidologie 40(3), 347-354.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Carbone LM, Tavella J, Pausas JG, Aguilar R (2019) A global synthesis of fire effects on pollinators. Global Ecology and Biogeography 28(10), 1487-1498.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Carbone LM, Tavella J, Marquez V, Ashworth L, Pausas JG, Aguilar R (2024) Fire effects on pollination and plant reproduction: a quantitative review. Annals of Botany 135(1–2), 43-56.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Celebrezze T, Paton DC (2004) Do introduced honeybees (Apis mellifera, Hymenoptera) provide full pollination service to bird-adapted Australian plants with small flowers? An experimental study of Brachyloma ericoides (Epacridaceae). Austral Ecology 29(2), 129-136.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Chapman NC, Colin T, Cook J, da Silva CRB, Gloag R, Hogendoorn K, Howard SR, Remnant EJ, Roberts JMK, Tierney SM, Wilson RS, Mikheyev AS (2023) The final frontier: ecological and evolutionary dynamics of a global parasite invasion. Biology Letters 19(5), 20220589.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Cunningham SA, Crane MJ, Evans MJ, Hingee KL, Lindenmayer DB (2022) Density of invasive western honey bee (Apis mellifera) colonies in fragmented woodlands indicates potential for large impacts on native species. Scientific Reports 12(1), 3603.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

DAFF (2011) A honey bee industry and pollination continuity strategy should Varroa become established in Australia. Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry, Canberra. Avaliable at https://www.agriculture.gov.au/sites/default/files/sitecollectiondocuments/animal-plant/pests-diseases/bees/honeybee-report.pdf

Day DA, Collins BG, Rees RG (1997) Reproductive biology of the rare and endangered Banksia brownii Baxter ex R. Br. (Proteaceae). Australian Journal of Ecology 22(3), 307-315.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Debnam S, Saez A, Aizen MA, Callaway RM (2021) Exotic insect pollinators and native pollination systems. Plant Ecology 222(9), 1075-1088.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts (DEWHA) (2008) Approved Conservation Advice for Persoonia glaucescens (Mittagong Geebung). (Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts, Canberra). Available at http://www.environment.gov.au/biodiversity/threatened/species/pubs/12770-conservation-advice.pdf

Dick CW (2001) Genetic rescue of remnant tropical trees by an alien pollinator. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences 268(1483), 2391-2396.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Dorey JB, Rebola CM, Davies OK, Prendergast KS, Parslow BA, Hogendoorn K, Leijs R, Hearn LR, Leitch EJ, O’Reilly RL, Marsh J, Woinarski JCZ, Caddy-Retalic S (2021) Continental risk assessment for understudied taxa post-catastrophic wildfire indicates severe impacts on the Australian bee fauna. Global Change Biology 27(24), 6551-6567.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Eakin-Busher EL, Ladd PG, Fontaine JB, Standish RJ (2020) Mating strategies dictate the importance of insect visits to native plants in urban fragments. Australian Journal of Botany 68(1), 26-36.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Elliott B, Wilson R, Shapcott A, Keller A, Newis R, Cannizzaro C, Burwell C, Smith T, Leonhardt SD, Kämper W, Wallace HM (2021) Pollen diets and niche overlap of honey bees and native bees in protected areas. Basic and Applied Ecology 50, 169-180.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

England PR, Beynon F, Ayre DJ, Whelan RJ (2001) A molecular genetic assessment of mating-system variation in a naturally bird-pollinated shrub: contributions from birds and introduced honeybees. Conservation Biology 15(6), 1645-1655.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Falster D, Gallagher R, Wenk EH, Wright IJ, Indiarto D, Andrew SC, Baxter C, Lawson J, Allen S, Fuchs A, Monro A, et al. (2021) AusTraits, a curated plant trait database for the Australian flora. Scientific Data 8(1), 254.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Gilpin A-M, Ayre DJ, Denham AJ (2014) Can the pollination biology and floral ontogeny of the threatened Acacia carneorum explain its lack of reproductive success? Ecological Research 29, 225-235.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Gilpin A-M, Collette JC, Denham AJ, Ooi MKJ, Ayre DJ (2017) Do introduced honeybees affect seed set and seed quality in a plant adapted for bird pollination? Journal of Plant Ecology 10(4), 721-729.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Gilpin A-M, Denham AJ, Ayre DJ (2019) Are there magnet plants in Australian ecosystems: pollinator visits to neighbouring plants are not affected by proximity to mass flowering plants. Basic and Applied Ecology 35, 34-44.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Goodman RD, Hepworth G (2004) Densities of feral honey bee Apis mellifera colonies in Victoria. Victorian Naturalist 121(5), 210-214.

| Google Scholar |

Goulson D (2003) Effects of introduced bees on native ecosystems. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 34(1), 1-26.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Goulson D, Derwent LC (2004) Synergistic interactions between an exotic honeybee and an exotic weed: pollination of Lantana camara in Australia. Weed Research 44(3), 195-202.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Gross CL (2001) The effect of introduced honeybees on native bee visitation and fruit-set in Dillwynia juniperina (Fabaceae) in a fragmented ecosystem. Biological Conservation 102(1), 89-95.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Gross CL, Mackay D (1998) Honeybees reduce fitness in the pioneer shrub Melastoma affine (Melastomataceae). Biological Conservation 86(2), 169-178.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Gross CL, Gorrell L, Macdonald MJ, Fatemi M (2010) Honeybees facilitate the invasion of Phyla canescens (Verbenaceae) in Australia–no bees, no seed!. Weed Research 50(4), 364-372.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Henry M, Rodet G (2018) Controlling the impact of the managed honeybee on wild bees in protected areas. Scientific Reports 8(1), 9308.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hermansen TD, Britton DR, Ayre DJ, Minchinton TE (2014) Identifying the real pollinators? Exotic honeybees are the dominant flower visitors and only effective pollinators of Avicennia marina in Australian temperate mangroves. Estuaries and Coasts 37, 621-635.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hingston AB, Potts BM, McQuillan PB (2004) The swift parrot Lathamus discolor (Psittacidae), social bees (Apidae), and native insects as pollinators of Eucalyptus globulus ssp. globulus (Myrtaceae). Australian Journal of Botany 52, 371-379.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Houston TF, Ladd PG (2002) Buzz pollination in the Epacridaceae. Australian Journal of Botany 50, 83-91.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Iwasaki JM, Hogendoorn K (2022) Mounting evidence that managed and introduced bees have negative impacts on wild bees: an updated review. Current Research in Insect Science 2, 100043.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Iwasaki JM, Barratt BIP, Lord JM, Mercer AR, Dickinson KJM (2015) The New Zealand experience of varroa invasion highlights research opportunities for Australia. Ambio 44, 694-704.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Jean RP (2005) Quantifying a rare event: pollen theft by honey bees from bumble bees and other bees (Apoidea: Apidae, Megachilidae) foraging at flowers. Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society 78(2), 172-175.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Locke B (2016) Natural Varroa mite-surviving Apis mellifera honeybee populations. Apidologie 47, 467-482.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Loper GM, Sammataro D, Finley J, Cole J (2006) Feral honey bees in southern Arizona 10 years after Varroa infestation. American Bee Journal 146(6), 521-524.

| Google Scholar |

Lopresti LC, Sommerville KD, Gilpin A-M, Minchinton TE (2023a) Floral biology, pollination vectors and breeding system of Zieria granulata (Rutaceae), an endangered shrub endemic to eastern Australia. Australian Journal of Botany 71(5), 252-268.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Lopresti LC, Sommerville KD, Gilpin A-M, Minchinton T (2023b) Reproductive biology of rainforest Rutaceae: floral biology, breeding systems and pollination vectors of Acronychia oblongifolia and Sarcomelicope simplicifolia subsp. simplicifolia. Cunninghamia 23, 11-26.

| Google Scholar |

Marsh JR, Bal P, Fraser H, Umbers K, Latty T, Greenville A, Rumpff L, Woinarski JCZ (2022) Accounting for the neglected: invertebrate species and the 2019–2020 Australian megafires. Global Ecology and Biogeography 31(10), 2120-2130.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Martin S (1998) A population model for the ectoparasitic mite Varroa jacobsoni in honey bee (Apis mellifera) colonies. Ecological Modelling 109, 267-281.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

NSW DPI (2023) Varroa mite emergency response. Department of Primary Industries, Parramatta. Available at https://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/emergencies/biosecurity/current-situation/varroa-mite-emergency-response

Oldroyd BP, Lawler SH, Crozier RH (1994) Do feral honey bees (Apis mellifera) and regent parrots (Polytelis anthopeplus) compete for nest sites? Australian Journal of Ecology 19(4), 444-450.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Oldroyd BP, Thexton EG, Lawler SH, Crozier RH (1997) Population demography of Australian feral bees (Apis mellifera). Oecologia 111, 381-387.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Ottewell KM, Donnellan SC, Lowe AJ, Paton DC (2009) Predicting reproductive success of insect-versus bird-pollinated scattered trees in agricultural landscapes. Biological Conservation 142(4), 888-898.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Outbreak, Australian Government (2023) Varroa mite (Varroa destructor). Available at https://www.outbreak.gov.au/current-outbreaks/varroa-mite

Page ML, Nicholson CC, Brennan RM, Britzman AT, Greer J, Hemberger J, Kahl H, Müller U, Peng Y, Rosenberger NM, Stuligross C, Wang L, Yang LH, Williams NM (2021) A meta-analysis of single visit pollination effectiveness comparing honeybees and other floral visitors. American Journal of Botany 108(11), 2196-2207.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Paini DR, Roberts JD (2005) Commercial honey bees (Apis mellifera) reduce the fecundity of an Australian native bee (Hylaeus alcyoneus). Biological Conservation 123(1), 103-112.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Passarelli L, Cocucci A (2006) Dynamics of pollen release in relation to anther-wall structure among species of Solanum (Solanaceae). Australian Journal of Botany 54(8), 765-771.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Paton DC (1993) Honeybees in the Australian environment. BioScience 43(2), 95-103.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Paton DC (2000) Disruption of bird-plant pollination systems in southern Australia. Conservation Biology 14(5), 1232-1234.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Potts SG, Biesmeijer JC, Kremen C, Neumann P, Schweiger O, Kunin WE (2010) Global pollinator declines: trends, impacts and drivers. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 25(6), 345-353.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Prendergast KS, Ollerton J (2022) Impacts of the introduced European honeybee on Australian bee-flower network properties in urban bushland remnants and residential gardens. Austral Ecology 47(1), 35-53.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Prendergast KS, Dixon KW, Bateman PW (2023) The evidence for and against competition between the European honeybee and Australian native bees. Pacific Conservation Biology 29(2), 89-109.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Pyke GH, Prendergast KS, Ren Z-X (2023) Pollination crisis Down-Under: has Australasia dodged the bullet? Ecology and Evolution 13(11), e10639.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Richardson MBG, Ayre DJ, Whelan RJ (2000) Pollinator behaviour, mate choice and the realised mating systems of Grevillea mucronulata and Grevillea sphacelata. Australian Journal of Botany 48(3), 357-366.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Simpson SR, Gross CL, Silberbauer LX (2005) Broom and honeybees in Australia: an alien liaison. Plant Biology 7(5), 541-548.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Visick OD, Ratnieks FL (2023) Density of wild honey bee, Apis mellifera, colonies worldwide. Ecology and Evolution 13(10), e10609.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Wagner DL (2020) Insect declines in the Anthropocene. Annual Review of Entomology 65(1), 457-480.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ward M, Carwardine J, Yong CJ, Watson JEM, Silcock J, Taylor GS, Lintermans M, Gillespie GR, Garnett ST, Woinarski J, Tingley R, et al. (2021) A national-scale dataset for threats impacting Australia’s imperiled flora and fauna. Ecology and Evolution 11(17), 11749-11761.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Wawrzyczek S, Holmes GD, Hoebee SE (2023) Reproductive biology and population structure of the endangered shrub Grevillea bedggoodiana (Proteaceae). Conservation Genetics 24(1), 7-23.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Wawrzyczek SK, Davis RA, Krauss SL, Hoebee SE, Ashton LM, Phillips RD (2024) Pollination by birds, non-flying mammals, and European honeybees in a heathland shrub, Banksia catoglypta (Proteaceae). Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 206, 257-273.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Whelan RJ, Ayre DJ, Beynon FM (2009) The birds and the bees: pollinator behaviour and variation in the mating system of the rare shrub Grevillea macleayana. Annals of Botany 103(9), 1395-1401.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Woinarski JCZ, Braby MF, Gibb H, Harvey MS, Legge SM, Marsh JR, Moir ML, New TR, Rix MG, Murphy BP (2024) This is the way the world ends; not with a bang but a whimper: estimating the number and ongoing rate of extinctions of Australian non-marine invertebrates. Cambridge Prisms: Extinction 2, e23.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |