Spatially variable recruitment response to fire severity in golden-top wattle (Acacia mariae, family: Fabaceae), a thicket-forming shrub of semi-arid forests

Boyd R. Wright A B C * , Damien D. Andrew

A B C * , Damien D. Andrew  A , Michael Hewins A , Claire Hewitt A D and Roderick J. Fensham E F

A , Michael Hewins A , Claire Hewitt A D and Roderick J. Fensham E F

A

B

C

D

E

F

Abstract

Investigations into the life history strategies of organisms in ecosystems prone to fires are essential for effective fire impact management. In Australia, fire severity is expected to increase under anthropogenic climate change (ACC), therefore understanding plant responses to this fire regime element is essential for developing conservation-focused burning practices.

Assess the recruitment response of golden-top wattle (Acacia mariae) to varying fire severities (high, low and unburnt) in the semi-arid Pilliga forest in Northern Inland New South Wales. Investigate seedbank dynamics and germination biology to inform post-fire recruitment patterning.

Longitudinal seedbank studies were performed to understand seedbank dynamics and the associated influence on post-fire regeneration. A laboratory trial was conducted to assess the effects of heat shock and incubation temperature on seed germination. Field surveys were conducted at four sites to assess fire severity impacts and evaluate spatial variability in post-fire recruitment after the 2018 Gibbican Rd wildfire.

Recruitment varied among sites but was highest in shrubs burned by high-severity fire (5.8 seedlings/shrub), followed by low-severity fire (0.8 seedlings/shrub) and unburnt shrubs (0.1 seedlings/shrub). Over 5 years, seedbank densities fluctuated markedly, peaking in 2021 following a major seeding event but declined rapidly thereafter. Germination was optimised when seeds underwent heat shock at temperatures between 100 and 140°C and incubated at warm temperatures.

Acacia mariae germination is promoted by heat stimulation, explaining why high intensity burns with higher soil temperatures enhance recruitment. Differences in seedbank densities at the time of fire may account for varied recruitment across landscapes. Overall, A. mariae regenerates well after high-severity fires but poorly after low-severity fires, indicating that the species may be resilient to increased fire severity under ACC but struggle under current widespread low-severity prescribed management burning regimes.

Keywords: Acacia, burn severity, climate change, fire regime, granivore, recruitment, seedbank, semi-arid.

Introduction

Wildfires play a pivotal role in shaping the dynamics of ecosystems worldwide, with many Australian forested and woodland landscapes particularly prone to large-scale, intermittent fire events (Bradstock 2010; Bowman et al. 2021a; Fensham et al. 2024). Despite the long evolutionary history of fire in Australia, the current rise in global temperatures and shifts in atmospheric conditions under anthropogenic climate change (ACC) are fundamentally reshaping the environmental context in which fires occur (Bowman et al. 2020; Pausas and Leverkus 2023; Di Giuseppe et al. 2024). Given these changing conditions, the resilience of many Australian plant species is speculated to be challenged, with biodiversity risks from wildfires heightened by anticipated increases in fire frequency, fire intensity (the energy output of a fire, measured as heat released per unit area) and fire severity (the ecological impacts of a fire, including effects on vegetation and soil) (Keeley 2009; Bowman et al. 2020; Bousfield et al. 2023; Cunningham et al. 2024a, 2024b).

The genus Acacia, comprising c. 1084 species worldwide, dominates the Australian flora and is integral to the biodiversity and ecological functioning of many fire-prone environments. In common with other obligate-seeding (i.e. fire-killed) species, many Acacia species exhibit a range of adaptations to fire, including fire-stimulated germination, seed dormancy strategies and post-fire resprouting (Sabiiti and Wein 1987; Tozer 1998; Gordon et al. 2017; Cruz et al. 2021; Le Breton et al. 2023). Reflecting a resilience to burning, numerous studies have shown that recruitment of Acacia species responds positively to high severity burning, with high-intensity fires enhancing soil heating and leading to increased recruitment by stimulating germination from heat-primed seedbanks (Hodgkinson and Oxley 1990; Gibson et al. 2011; Ooi 2012; Gordon et al. 2017; Palmer et al. 2018). Additionally, for Acacia species with transient seedbanks due to high seed predation (e.g. A. aptaneura, A. melleodora), the timing of fires in relation to soil seedbank density fluctuations plays a crucial role in post-fire regeneration (Wright and Clarke 2018; Wright and Fensham 2017). High-severity fires following large-scale seeding events, when seed populations pulse, can trigger prolific recruitment from heat-activated seedbanks for these species.

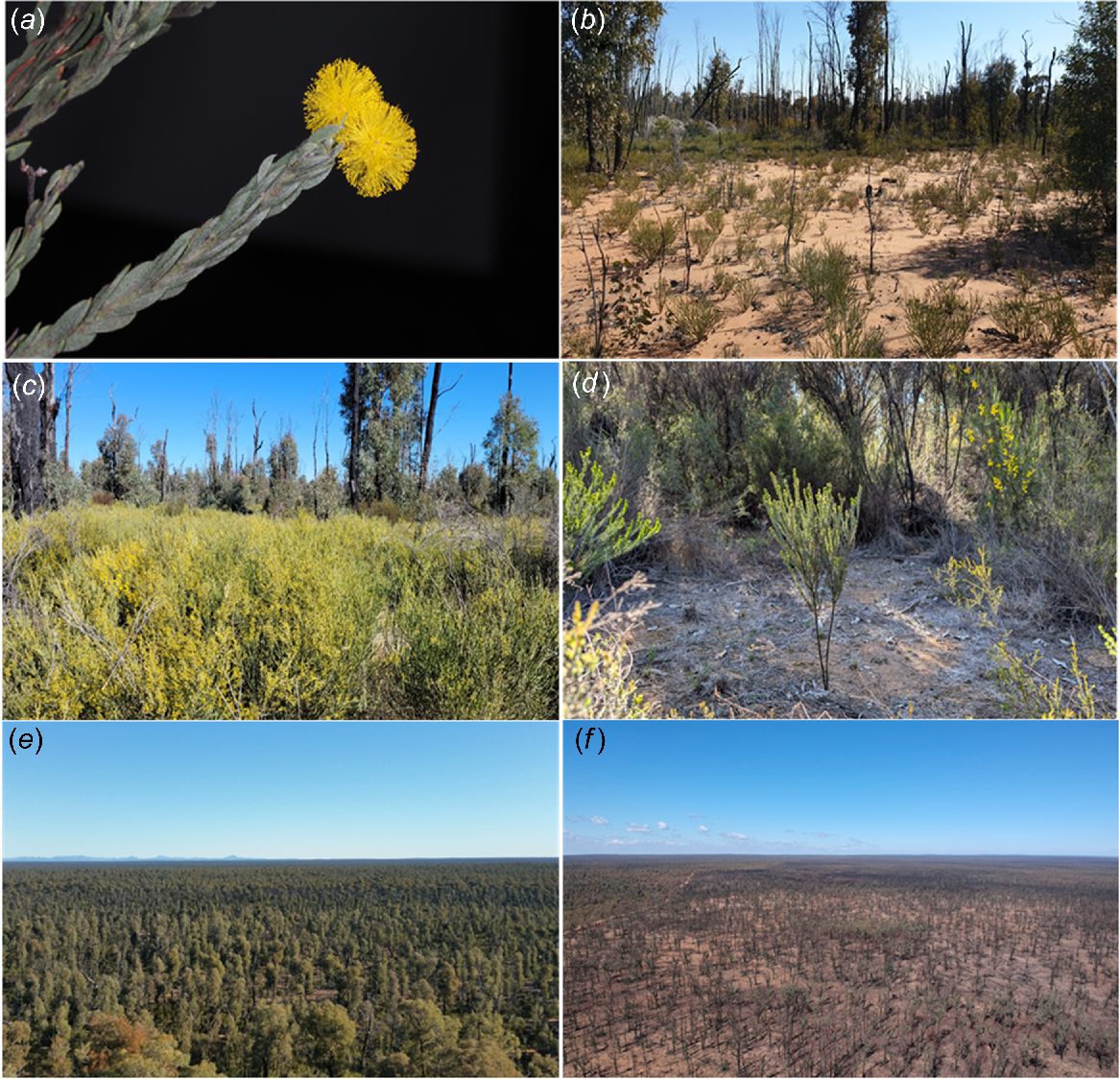

A widespread but poorly researched Acacia species in semi-arid western New South Wales (NSW) is Acacia mariae Pedley (family: Fabaceae, subfamily: Mimosoideae; syn. A. tindaleae Pedley), commonly referred to as golden-top wattle (Fig. 1a–d). This Acacia species is an obligate-seeder and thicket-forming, and in our previous experiments in which we used a plant ignitability unit, results showed that the plant matter has fire-retardant properties, such as lower burn temperatures and slower ignition than coexisting plants (Supplementary Appendix Fig. S1). This reduced flammability appears to be crucial for preventing fire from penetrating the central areas of thickets during high-intensity fires, allowing shrubs in the interior to either remain unburnt or experience lower burn severities, thereby aiding the persistence of stands post-fire.

(a) golden-top wattle(Acacia mariae) inflorescence/vegetation. (b) Dense post-fire A. mariae regeneration after 2018 high-severity wildfire at Rocky Rd site. (c) Unburnt A. mariae thicket in recently burnt eucalypt forest. (d) Rare A. mariae seedling among unburnt A. mariae shrubs. (e) Unburnt eucalypt forest, central Pilliga. (f) Burnt forest after high-severity Gibbican Rd wildfire in 2018 (photos T. Shaldoom, D. D. Andrew and B. R. Wright).

Despite the low flammability of A. mariae vegetation that seems to prevent fire incursion, our field observations suggest that the species uses a bet-hedging strategy, also demonstrating strong seedling regeneration after fire. Although no ecological studies have focused on this species, we propose that fire likely promotes A. mariae recruitment by raising soil temperatures and breaking the physical seed dormancy common to many hard-seeded Acacia species. Our preliminary field observations also indicate significant spatial and temporal variability in A. mariae seedbanks. Therefore, as with other arid Acacia species, the timing of fire relative to seedbank fluctuations may play a crucial role in shaping recruitment responses within shrub populations.

Our study aimed to quantify the proposed relationship between fire severity and recruitment in A. mariae, and to test whether this relationship is spatially consistent. In addition, to test the prediction that recruitment patterning is driven by seedbank transience and/or heat-stimulated germination, longitudinal seedbank studies and a germination trial were carried out. The following experiments were conducted for this study: (1) a quantitative field survey across four shrub populations to monitor A. mariae recruitment after high and low severity burning and no fire; (2) a germination trial to determine the effects of heat shocking and incubation temperature on seed germination; and (3) seedbank studies at three sites to examine changes in seedbank densities at different spatial locations and soil depths over time.

Methods

Study area

The Pilliga forest spans more than half a million hectares and is located in the Northern Inland region of NSW. Mean annual precipitation varies across the forest, averaging 750 mm at Coonabarabran in the forest’s south (Australian Government Bureau of Meteorology 2024a) and 626 mm in Baradine in the central region (Australian Government Bureau of Meteorology 2024b). The forest’s soils originate primarily from non-marine Jurassic Pilliga sandstone, with widespread outcrops of this geological formation, along with associated skeletal soils, common in the southern regions of the forest (Arditto 1982; Dodson and Wright 1989). Dendritic streams drain from these outcrops in northward and westward directions, and this has led to the development of extensive areas of sediment-rich outwash soils in the northern and western sectors of the forest.

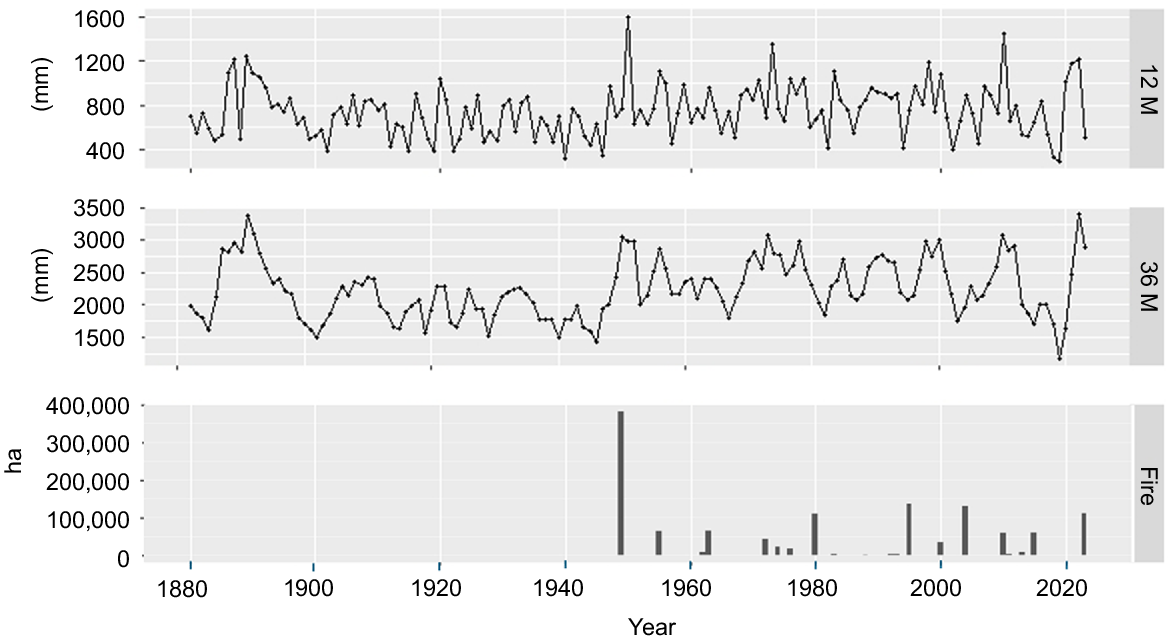

The forest is usually divided into two main areas for management purposes: a western zone, comprising numerous river valleys and extensive areas of productive white cypress pine (Callitris glaucophylla) woodland; and an eastern zone, characterised by eucalypt-dominated ridgetop forests and woodlands interspersed with creekline woodlands. Our preliminary field observations indicate that the vegetation of the ridgetop forests is usually dominated by eucalypts such as Corymbia trachyphloia, Eucalyptus crebra and E. rossii. The creekline woodlands in both the east and west are dominated by E. blakelyi, E. melliodora, E. crebra and Angophora floribunda. Vegetation throughout the forest is characterised by a dense shrub layer, dominated by genera such as Acacia, Allocasuarina, Daviesia, Dodonaea, Eremophila and Phebalium. Grasses are typically sparse in the Pilliga, though the high rainfall in 2021–2022 that followed the 2018–2020 drought (Fig. 2) triggered the growth of a lush grassy understorey layer. This layer largely comprised grasses of the genera Aristida, Eragrostis and Enteropogon.

Cumulative 12-month (12 M – top panel) and 36-month (36 M – middle panel) antecedent rainfall, and total annual area burnt in the Pilliga forest (Fire – bottom panel). Rainfall data are from 1880 to the present and were recorded at the Coonabarabran Showground weather station on the southern edge of the Pilliga forest. Fire records span the duration of recorded fire events and run from 1949 to 2024. No data are available for pre-1949 fire occurrence.

Fire regimes

Eucalypt-dominated systems in the Pilliga forest are prone to high-severity wildfires, driven by continuous fuel loads that extend from sparse grassy understoreys (<1 m) through dense shrub layers (1–5 m) to low tree canopies (<30 m) with oil-rich foliage (Norris et al. 1991; Cohn et al. 2011; Murphy et al. 2021). These systems feature a high diversity of obligate-seeding Acacia species, most of which germinate densely after intense fires, mature rapidly and have short lifespans (<15 years). Large-scale (sometimes >300,000 ha), high-severity wildfires are an intrinsic component of the forest’s fire regime, and the incidence of these wildfires is closely associated with precipitation and fuel/soil moisture availability (Brookhouse et al. 1999). As in other semi-arid regions, fires often occur after successive high-rainfall seasons that promote plant growth and the accumulation of groundcover and shrub-layer fuels (Fig. 2) (Brookhouse et al. 1999). Additionally, wildfires can also occur following drought periods, presumably because such conditions increase fuel dryness and heighten vegetation flammability (Fig. 2). Wildfires are mostly started by lightning during electrical storms that occur between the months of November and February.

There are no quantitative data on Aboriginal fire management before European colonisation of the region. However, studies from other arid systems and the 2019–2020 Black Summer fires in eastern Australia suggest that large-scale, high-severity fires are a natural part of woodland and forest ecosystems during extreme climatic conditions and that management/patch burn fires have low influence in preventing these (Sakaguchi et al. 2013; Bowman et al. 2021a, 2021b; Wright et al. 2021). Therefore, large wildfires likely occurred before European arrival during periods of climatic extremes, despite any active fire management by Aboriginal peoples in the Pilliga. Climate-linked fires also almost certainly existed over much longer evolutionary timescales in the prehuman era.

Study species

Acacia mariae is an erect or spreading shrub that grows to 2 m in height and is native to central NSW. The bark is smooth and grey, and the small (0.4–1.3 cm long) phyllodes are covered in fine silvery-grey appressed hairs (Fig. 1a). The geographic distribution encompasses the western slopes and plains of NSW, and the species grows on well-drained, sandy soils in Eucalyptus–Callitris woodland, forest and mallee communities. Throughout the range, A. mariae often forms dense thickets (Fig. 1c) but can also occur as isolated individuals. Flowering occurs during winter months, while pod maturation and subsequent seed dispersal take place from mid to late spring (October–November). Field observations suggest that interannual reproductive output is highly variable and flower abortion rates are high (BRW, DA unpubl. data – Appendix Fig. 2). The species is closely related to A. conferta A.Cunn. ex Benth. that is widespread in a similar rainfall zone in NSW and Queensland, also thicket-forming and likely ecologically equivalent (Maslin 2001).

Recruitment study

The impacts of fire severity on A. mariae seedling recruitment were assessed in July 2021 at the following four sites: Gibbican Rd, Timmellallie Creek, No. 1 Break Rd and Rocky Creek Rd. At each site, fire severity during the 2018 wildfires had been patchy. This site-level variability in fire severity facilitated systematic stratification of shrubs into three distinct fire severity categories: high severity burnt, low severity burnt and unburnt. High severity burnt shrubs were classified based on burnt twigs/branches having a ‘mean minimum burnt tip diameter’ (MMBD) exceeding 3 mm (Moreno and Oechal 1991). In contrast, shrubs in the low severity burn class exhibited vegetation that had undergone scorching but displayed twig/branch MMBDs measuring less than 1 mm. Unburnt shrubs were classified as having remained unburnt during the wildfires.

At each site, 20 shrubs from each of the three burn severity categories were systematically tagged and numbered using the stratified random sampling methodology of Harding (2012). Subsequently, a random number generator was used to select 10 shrubs for each burn severity category. A circular quadrat with a 1 m radius with the base of the shrub as the centroid was used to quantify the number of seedlings directly beneath shrub canopies for each shurb. Exclusion criteria for the shrubs included ensuring that the radii of any two sampling quadrats did not overlap and that sampled shrubs were not directly adjacent to mature trees. This was done to reduce the potential competition between established trees and seedlings which could affect the likelihood of seedling establishment.

Seedbank study

Acacia mariae seedbank dynamics were monitored over a period of 60 months from four reproductively mature shrubs at the Rocky Creek Rd site of the recruitment study. The sampling timeframe encompassed a widespread seed production event that occurred in the spring of 2020. Selection of the four shrubs for sampling was based on reproductive maturity at the time of assessment and the absence of any fire damage during the 2018 summer wildfire event. Seedbank sampling was also carried out at the Timmellallie Creek and Number 1 Break Rd sites of the recruitment study. However, resource constraints meant that only three rounds of sampling occurred at these two sites over a period of 20 months between January 2021 and August 2022.

At each sampling site, the seedbanks of four shrubs were sampled. At each of these shrubs, two randomly selected 20 × 20 cm square by 6 cm deep columns of soil were excavated from beneath the shrub canopy. Following the trenching of column sides, the surface litter layer and the deeper 5 × 1 cm layers were removed from the column using a paint scraper and steel ruler. Seed populations in these various layers were assessed in the field by passing the soil/litter materials through 1.6 mm sieves and enumerating the seeds. Post-extraction, seed viability was evaluated by splitting the seeds and inspecting for intact white embryo tissue. When large numbers of seeds were encountered in the samples, viability testing was conducted on a representative sample of 20 seeds. The overall percentage viability for these larger samples was subsequently calculated by multiplying the total seed count by the estimated percentage viability of the representative sample. To prevent resampling the same location during successive sampling rounds, 15 cm long steel camping pegs were inserted into the ground whenever a soil column was extracted.

Germination study

A germination trial was conducted in 2021 in a laboratory at the University of New England, Armidale. Seeds for the trial were sourced from five randomly chosen A. mariae shrubs located at the Number 1 Break Rd and Timmellallie sites of the ‘recruitment study’. Seed samples were stored in paper bags for 3 months after collection at room temperature. The experimental design of the trial used a two-factor orthogonal design, with the primary objective being to test the impact of heat shock and incubation temperature on seed germination. Heat shock effects were assessed by comparing the germination of untreated (control) seeds with the germination of seeds that were heat shocked for 5 min at temperatures of 60, 80, 100, 120 and 140°C. The effects of incubation temperature on seed germination were examined by comparing germination of seeds incubated in darkness at 25°C (intended to represent a mean summertime soil temperature at 2 cm depth), with seeds incubated at 10°C (intended to approximate a mean wintertime soil temperature at the same depth).

Five replicates of 20 seeds were used for each combination of the heat shock and incubation temperature treatments, resulting in a total of 100 seeds tested for each of the 12 treatment combinations. After the heat shock treatment, the seeds were arranged on Whatman No. 1 germination pads (Advantec, Dublin, California, USA) that had been placed on moisture-retaining sponges positioned within 100 mm petri dishes. The dishes were sterilised in boiling water, and sponges were placed in these and moistened with water sourced from the Armidale town water supply. The dishes were randomly distributed in the 10 and 25°C incubators. The incubation period spanned 21 days, and the trays were checked daily and kept moist for the duration of the trial. A final count of germination was conducted at the termination of the incubation period, with germination being defined as the emergence of the radicle from the testa. Tetrazolium testing of the unviable seeds was not conducted at the closure of the study and we acknowledge this as a limitation of the study.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using R statistical software (R Core Team 2023). Prior to each analysis, the datasets underwent exploration following the protocols outlined by Zuur et al. (2010). To model the relationship between A. mariae seedling recruitment and fire severity, a negative binomial (NB) generalised linear model (GLM) was employed using the R base package with fire severity as a fixed factor with three levels: ‘high-severity’, ‘low-severity’ and ‘unburnt’. In this analysis, the inclusion of site as an additional fixed factor facilitated the assessment of variation in the relationship between recruitment and fire severity across sites. Following model fitting, a post hoc comparison with a Bonferroni correction was conducted using the ‘emmeans’ package (Lenth 2016) to assess recruitment differences among the three fire severity categories and among the four sites. Model validation, including graphical model validation procedures, and overdispersion and zero inflation testing, was performed to ensure compliance with the underlying assumptions of the model.

The temporal dynamics and soil depth distribution of the Rocky Creek Rd seedbank dataset were examined using an NB generalised linear mixed model (GLMM) in the ‘lme4’ package (Bates et al. 2015). ‘Soil depth’ and ‘sampling time’ were incorporated as fixed effects and initial modelling tested for an interaction between these terms. ‘Shrub’ was modelled as a random factor to address temporal dependencies stemming from the repeated sampling of soils from the same shrubs over time. Upon establishing non-significance, the DEPTH × TIME interaction term was removed, and the model was re-run to assess the main effects of soil depth and sampling time. As with the recruitment analysis, graphical validation procedures were employed to verify the NB GLMM’s underlying assumptions.

Intersite variability in soil seed populations through time and across soil depths was also assessed for the Timmellallie Creek and Number 1 Break Rd sites using an NB GLMM. In this model, ‘Site’, ‘Soil depth’ and ‘Sampling time’ were incorporated in the model as fixed effects and modelling tested for an interaction between these terms. As with the other analyses, graphical validation procedures were employed to test the underlying assumptions of the model.

The interactive effects of heat shock temperature and incubation temperature on A. mariae seed germination were modelled using a GLM with a binomial distribution. A likelihood ratio test was applied to test the significance of the interaction between these two variables. After model fitting, graphical validation procedures were carried out to assess the underlying assumptions of the model (i.e. fitted values were plotted against residuals etc.).

Results

Recruitment study

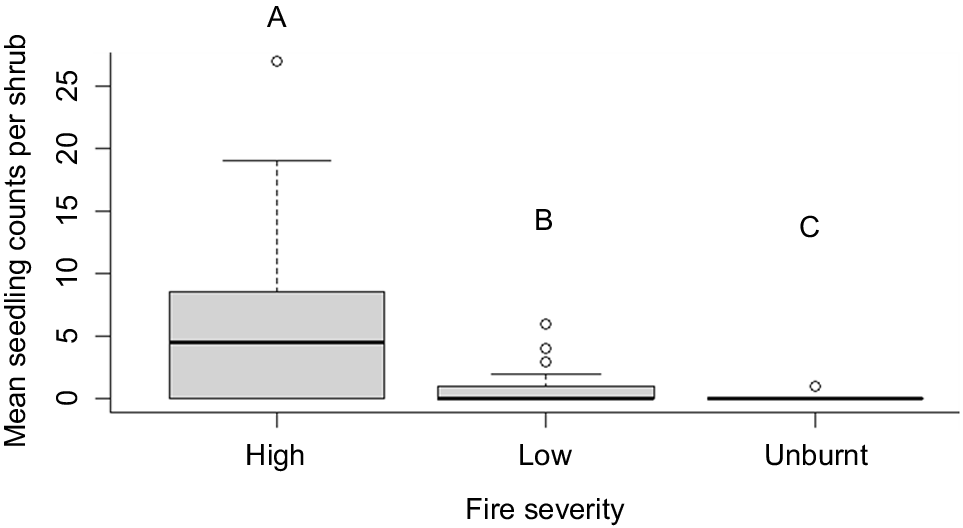

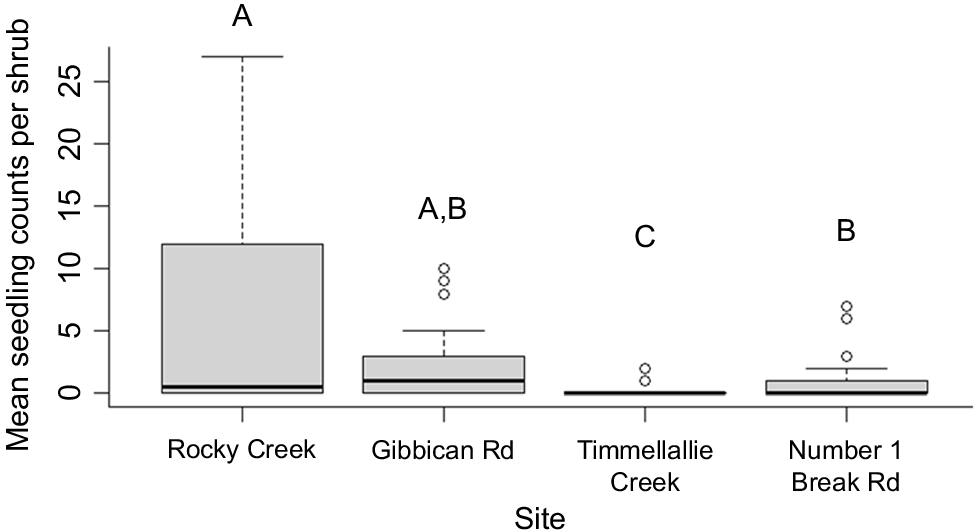

There was a strong association between seedling recruitment and fire severity (deviance = 230.26, d.f. = 2, Pr(>Chi) < 0.0001), with post-hoc testing revealing significantly higher seedling counts at shrubs burnt at high severity than those burnt at low severity and that were unburnt (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 3). The model also demonstrated strong variation in seedling densities between sites (deviance = 151.68, d.f. = 3, Pr(>Chi) = <0.0001), with significantly more recruitment at Rocky Creek compared to the Timmellallie Creek and Number 1 Break Rd sites, and significantly less recruitment at the Timmellallie Creek site than all other sites (Fig. 4).

Boxplot showing median seedling counts (and interquartile ranges) under A. mariae shrubs across four sites in the Pilliga forest, stratified according to whether plants had experienced high- or low-severity fire or remained unburnt during the January 2018 Gibbican Rd wildfire. Boxes denoted by different lettering indicate significant differences between fire severities under post-hoc testing (P < 0.05).

Boxplot showing median seedling counts (and inter-quartile ranges) beneath A. mariae shrubs observed across four sites in the Pilliga forest (results are pooled across fire severities). Boxes denoted with different lettering indicate significant differences between sites under post-hoc testing (P < 0.05).

Seedbank study

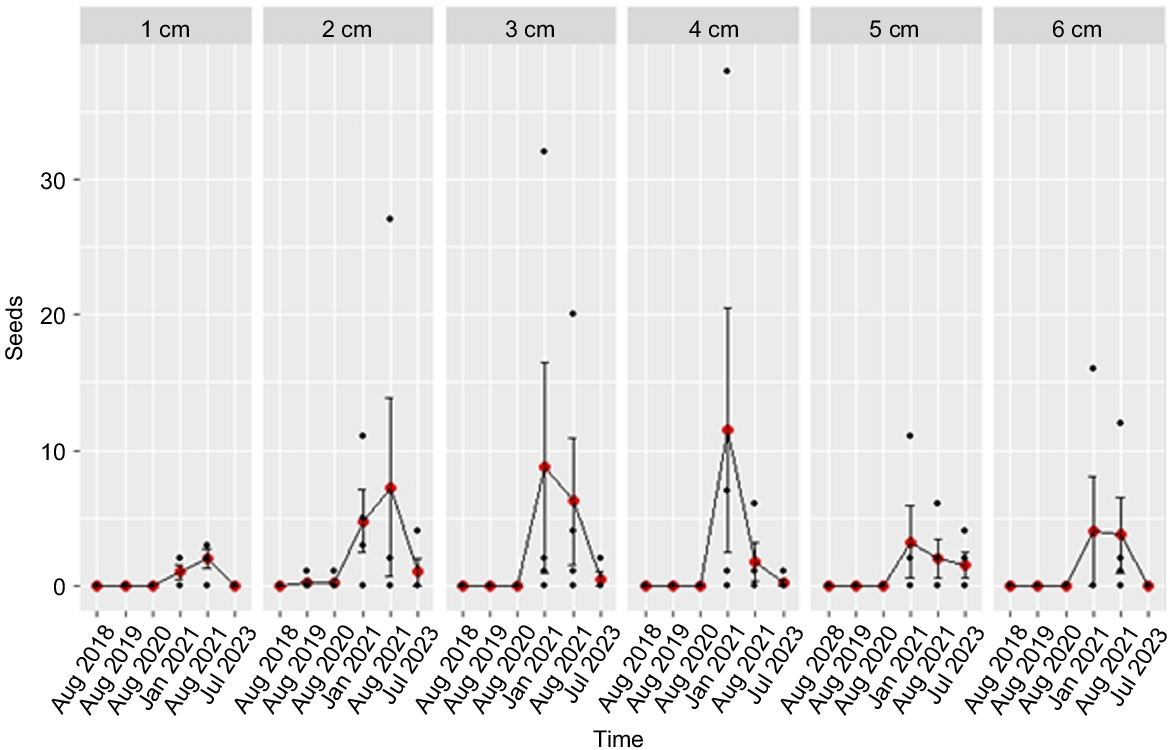

Seed numbers exhibited no significant variation across the different soil depths over 60 months at Rocky Creek Rd (Likelihood Ratio Test (LRT) statistic = 4.046, Pr(Chi) = n.s.). Nonetheless, the NB GLMM analysis demonstrated a significant time effect (LRT statistic = 68.97, Pr(Chi) < 0.0001), with mean seed densities low across all soil depths during the 2018, 2019 and 2020 sampling rounds (0 (s.e. = ± 0), 1 (s.e. = ± 1) and 1 seeds/m2 (s.e. = ± 1) respectively) (see Fig. 5) but with a significant increase in seed densities during the January 2021 sampling round (138.54 seeds/m2 (s.e. = ± 51.36)) (Fig. 5). In the mid-2021 and 2023 sampling rounds, seed numbers experienced a rapid decline from the January 2021 densities, with mean seed numbers across all soil depths of 95.8 (s.e. = ± 34.4) and 13.5 (s.e. = ± 6.2) seeds/m2 in August 2021 and July 2023, respectively (Fig. 5).

Viable A. mariae seed counts/sampling unit (0.4) m2 (including raw data (black dots), mean values (red dots) and standard errors of means (bars)) at Rocky Creek site in the Pilliga forest. Seedbanks were sampled at six time periods between 2018 and 2023, with sampling stratified across six soil depths.

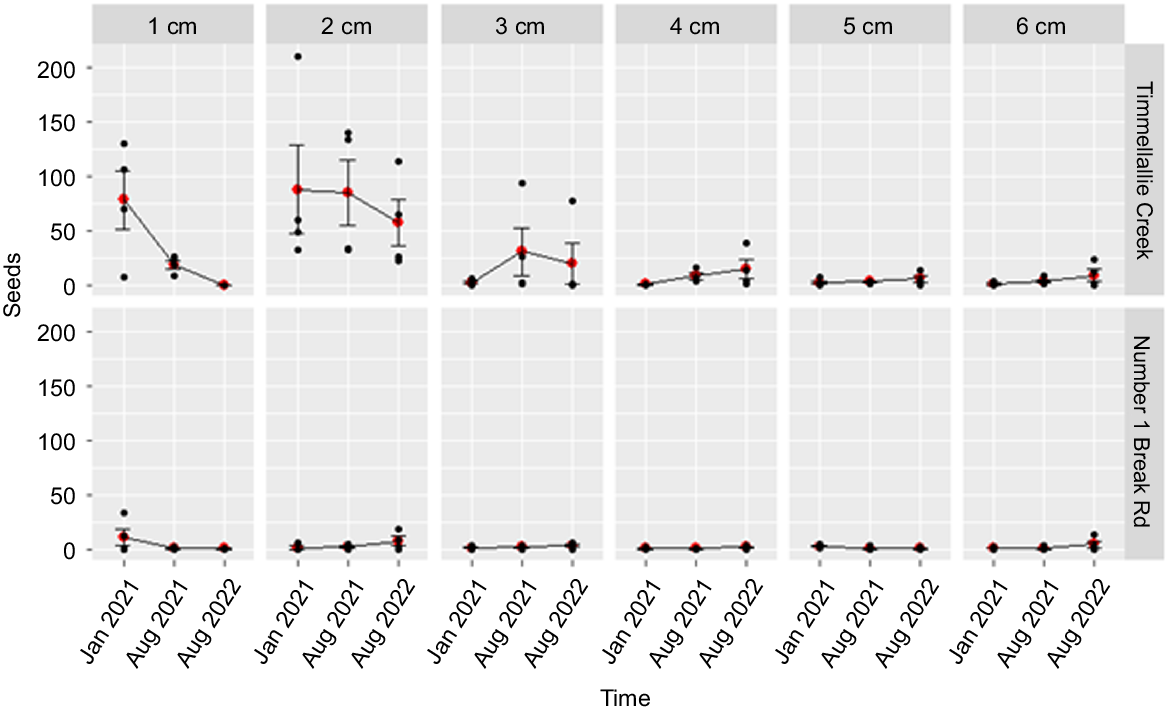

The analysis of the 18-month seedbank data from the Timmellallie and Number 1 Break Rd sites detected a significant three-way interaction between site, soil depth and sampling time. This indicated that the relationship between seed densities at different soil depths and sampling times differed between sites (Fig. 6). Post-hoc testing indicated that, like the Rocky Creek dataset, seed numbers at the Timmellallie Creek site declined through time from the initial January 2020 sampling time. In contrast, seed numbers were low at all soil depths and sample times for the Number 1 Break Rd site and post-hoc testing indicated no significant differences through time at this site.

Viable A. mariae seed counts/sampling unit (0.4) m2 (including raw data (black dots), mean values (red dots) and standard errors of means (bars)) at Timmellallie and Number 1 Break Rd sites in the Pilliga forest, sampled between January 2021 and August 2022. Sampling was stratified across six soil depths.

Germination study

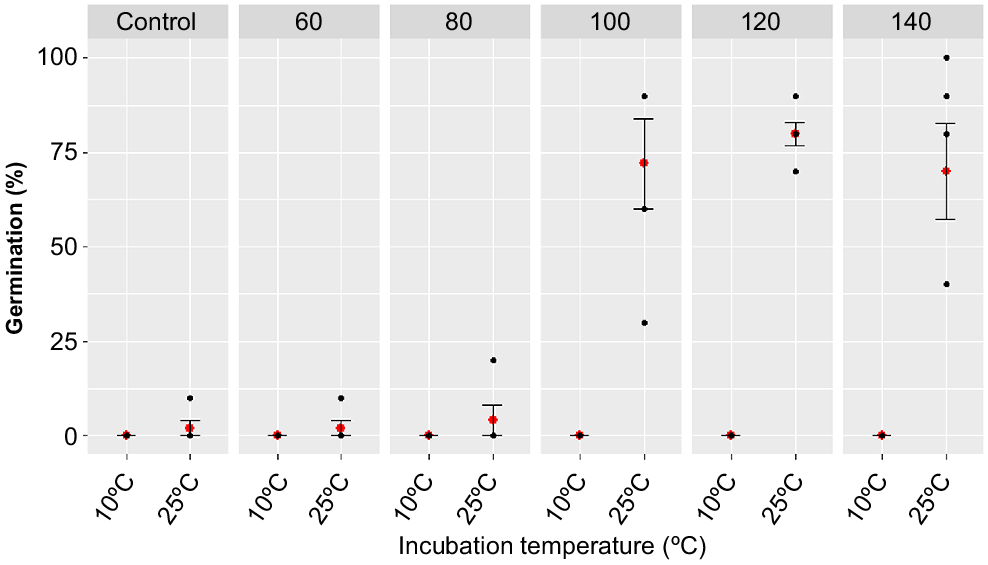

There was a significant interaction between heat shock temperature and incubation temperature on the proportion of germinated A. mariae seeds (deviance = 84.226, d.f. = 5, Pr(>Chi) = 0.00302) (Fig. 7). This indicated that the relationship between germination and ‘heat shock’ varied between the two different incubation temperatures. This effect is illustrated in Fig. 7, which shows that in the 10°C incubation cabinet not a single seed germinated, regardless of heat shock temperatures. In contrast, in the 25°C cabinet, a strong positive relationship existed between heat shock temperature and the proportion of seeds that germinated. In the 25°C cabinet, minimal (<5%) germination occurred for the control, 60 and 80°C heat shock temperatures. However, a strong increase in germination occurred for the 100 (mean = 72%, s.e. = ± 1.2), 120 (mean = 80%, s.e. = ± 0.3) and 140°C (mean = 70%, s.e. = ± 1.3) heat shock temperatures (Fig. 7).

Percentage germination of A. mariae seeds treated under different combinations of incubation temperature (10 and 25°C) and heat shock temperature (control, 60, 80, 100, 120 and 140°C). Five replicates (20 seeds per replicate) were tested for each combination of heat shock and incubation temperature treatments. No artificial lighting was supplied during incubation (i.e. the seed trays were incubated in darkness). Red dots in the figure are mean number of seeds that germinated, bars are standard errors of means and black dots are raw data points.

Discussion

Our quantitative field experiment supported the hypothesis that a positive relationship exists between increasing fire severity and Acacia mariae recruitment. However, the strength of this relationship was also found to have varied across shrub populations. Observations of strong recruitment after high severity burning are consistent with earlier studies by Gordon et al. (2017), who observed positive recruitment responses in twelve of sixteen Acacia species after the high-severity ‘Wambelong’ wildfire of 2013 in Warrumbungle National Park, slightly south of the Pilliga. In a separate study within the same park, Palmer et al. (2018) documented a nearly four-fold increase in the mean density of live woody Acacia stems under high compared to low severity-burnt shrubs. Similar positive associations between fire severity and seedling regeneration have been reported by Knox and Clarke (2012) in the New England Tableland Bioregion, Le Breton et al. (2023) in wet sclerophyll forests of south-eastern Australia, and Wright et al. (2016) and Wright and Fensham (2018) in arid central Australia.

The generally positive effect of high-severity fires on A. mariae recruitment likely relates to physical dormancy in hard-coated seeds, with elevated soil temperatures during ‘hot’ fires priming the seeds for germination via heat stimulation (Baskin and Baskin 2004; Ooi et al. 2014). Most hard-seeded Acacia species require heat to break dormancy, as strophioles (lenses) on the seeds must be ruptured by heat to allow water imbibition to initiate germination (Letnic et al. 2000; Pound et al. 2015; Gordon et al. 2017; Burrows et al. 2018). Our hypothesis that A. mariae seeds possess physical dormancy and require heat shock for germination was supported by the germination experiment that demonstrated that seeds exposed to heat shocks between 100 and 140°C germinated well when incubated at 25°C. In contrast, seeds subjected to the same heat shock but incubated at 10°C did not germinate, indicating that lower incubation temperatures are unsuitable for growth. These findings suggest that A. mariae recruitment is most likely to succeed following intense summer fires that should provide optimal soil temperatures for heat-shocking seeds and would be followed by warm post-fire soil conditions that would be conducive to the germination of heat-primed seeds.

In addition to promoting greater soil heating, high-severity fires may trigger increased recruitment because these are more likely to fully consume litter layers on the forest floor than low-severity fires. Heavy litter layers can impose mechanical impedance to seedling emergence, and this has been demonstrated in some Allocasuarina species (Crowley 1986). Allelopathic chemicals in A. mariae litter may also possibly inhibit seed germination in unburnt areas and studies have shown that high soil temperatures during high-intensity fires can neutralise such chemical barriers to germination (Calviño-Cancela et al. 2018). However, further research is needed to test this hypothesis for A. mariae.

Although there was a generally positive effect of high fire severity on A. mariae recruitment, the effect was spatially variable, with shrubs at the Timmellallie Creek site experiencing minimal recruitment after the 2018 wildfire, irrespective of fire severity. This spatial variability in recruitment could relate to several factors, including between-site differences in post-fire rainfall, variable seedbank densities at the time of fire, and/or post-fire herbivory on seedlings. Limited studies have quantified the relationship between post-fire rainfall and plant recruitment, with notable exceptions including the works of Erickson et al. (2023) on arid Australian spinifex grasses, Wright et al. (2019) on the Gibson desert shrub Aluta maisonneuvei, and various studies on Mediterranean shrubs (Parra and Moreno 2018; Chamorro and Moreno 2019). Nevertheless, considering the intrinsic small-scale patchiness of rainfall in Australia, intersite variations in post-fire rainfall volume may conceivably have contributed to intersite differences in the recruitment of A. mariae seedlings.

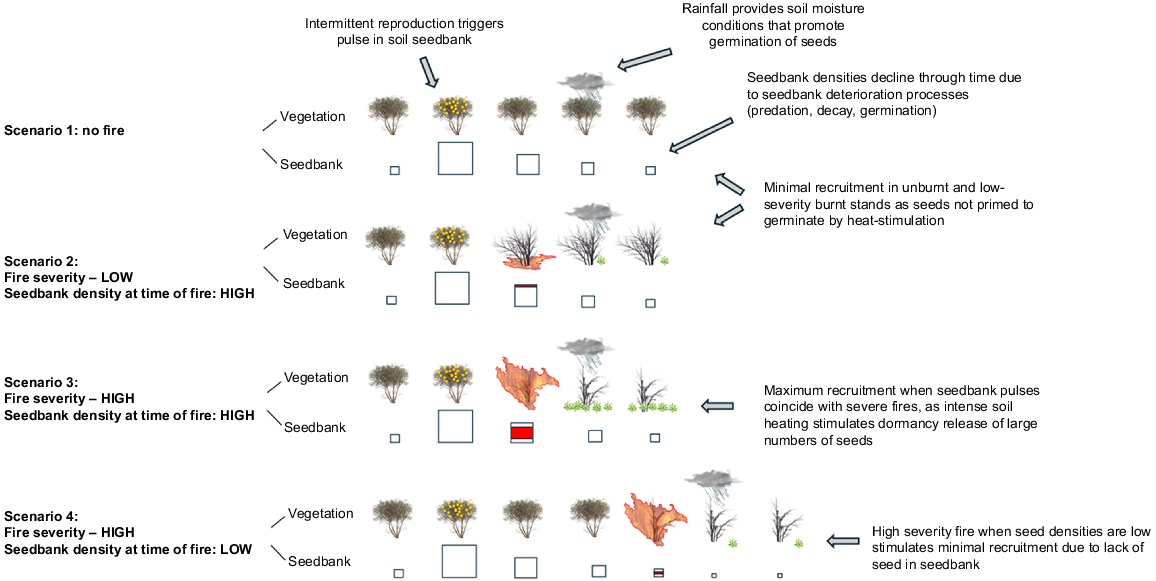

Our seedbank studies supported the possibility that variations in seedbank density at the time of fire could also have affected the recruitment responses of A. mariae shrubs. The observed surge and subsequent decline in A. mariae soil seed populations of shrubs at the Rocky Creek and Timmellallie Creek sites following the high seed production year of 2020 indicate that the seedbanks of A. mariae are transient rather than persistent, and that an association likely exists between sporadic seed fall events and seedbank dynamics. In light of this finding, the shrub populations at sites that had higher levels of recruitment in our quantitative field survey may have had more recent and/or higher volume seed production events prior to fire than sites that had minimal recruitment. Similar associations between intermittent seed input events, seedbank pulses and enhanced post-fire seedling recruitment have been documented in the arid Australian shrubs, Acacia aptaneura (Wright and Zuur 2014; Wright and Fensham 2017) and Acacia melleodora (Wright and Clarke 2018), and experimentally tested in the arid zone masting grass, Triodia pungens (Wright and Fensham 2018). Fig. 8 illustrates this proposed relationship in A. mariae, with optimal recruitment from the heat-activated seedbank expected when intense fires with high soil heating occur during periods of elevated seedbank density (Fig. 8 – scenario 3).

Proposed dynamics of post-fire recruitment of Acacia mariae under four scenarios involving differing fire severities (unburnt, low-severity, high-severity) and differing seedbank densities at time of fire (high, low). Upper illustrations for each of the four scenarios (shrubs’ line) depict seedling recruitment response to differing burn/seedbank scenarios (more seedlings ( ) corresponds to more recruitment). Lower illustrations (boxes’ line) depict changes in seedbank densities over time, with box size indicating relative seedbank density. After seed production events, seedbank densities are expected to decrease over time due to processes such as predation, decay and germination. Red shading within the seedbank boxes indicates the proportion of the seedbank that has been cued to germinate by soil heating during fire.

) corresponds to more recruitment). Lower illustrations (boxes’ line) depict changes in seedbank densities over time, with box size indicating relative seedbank density. After seed production events, seedbank densities are expected to decrease over time due to processes such as predation, decay and germination. Red shading within the seedbank boxes indicates the proportion of the seedbank that has been cued to germinate by soil heating during fire.

Further research is needed to formally evaluate the proposed regeneration model in Fig. 8. Specifically, studies should experimentally test the relationship between seedbank density at the time of fire and post-fire recruitment. Similar studies have been undertaken on the arid-zone masting grass Triodia pungens, in which reproductive output was manipulated by clipping inflorescences before burning and applying watering treatments post-fire (Wright and Fensham 2017). A comparable approach could be used for A. mariae as its small size would make the species amenable for controlled manipulation of reproductive output.

Several factors could explain A. mariae seedbank transience, including high levels of seed predation, rapid seed deterioration, pathogen attack and/or germination of seeds from the soil seedbank. Several Australian studies have shown that while ants are significant dispersers of Acacia seeds, few consume the embryo, with most instead attracted to the lipid-rich eliasomes on Acacia seeds (Hughes and Westoby 1990; Ireland and Andrew 1995). Predation of the seedbank by vertebrate fauna seems a more likely explanation for A. mariae seedbank transience, with species such as the Pilliga mouse (Pseudomys pilligaensis), cockatoos (Cacatua spp.) and some marsupials all known to consume the entirety of Acacia seeds (Jefferys and Fox 2001; Irlbeck and Hume 2003; Tokushima and Jarman 2010). Senescence (death from old age) or lethal pathogen attack on A. mariae seeds would be unlikely to have occurred quickly enough to explain the rapid decline in seedbank densities that we observed. Most Acacia seeds are remarkably resilient and can survive for decades under optimal storage conditions (Leino and Edqvist 2010).

Conclusion

Fire-dependent obligate-seeder Acacia species are key components of many fire-prone Australian landscapes, yet research on the intricate fire ecology and life history of these species remains limited. Fire management in reserves dominated by these fast-growing species typically focuses on low-intensity, cool-season burns aimed at decreasing fuel loads and minimising ecological damage (Etchells et al. 2020; Landesmann et al. 2021; New South Wales National Parks and Wildlife Service 2023). Our research suggests that such fuel reduction burns may hinder the regeneration of A. mariae, as such burns could be sufficiently intense to kill shrubs but of insufficient intensity to generate the heat required to stimulate recruitment from heat-cued seedbanks. Acacia mariae may instead be well-adapted to the current ‘natural’ regime of intermittent high-severity fires during summer. The species employs a bet-hedging strategy, forming fire-retardant thickets that reduce fire severity during extreme fire conditions and also shows strong seedling recruitment after high-severity fires. Although long-term fire exclusion beyond the lifespan of individual trees could result in population decline, the species still demonstrates low-level recruitment in the absence of fire and is likely to persist under various burning (or non-burning) scenarios.

While A. mariae seems likely to be resilient to the high-severity fires expected under ACC, the question remains of whether thickets could be at risk if fire frequency increases significantly. This study did not investigate the ideal fire return interval for A. mariae but this would likely depend on the time required for plants to reach reproductive maturity and the persistence of seeds in the soil seedbank. We observed A. mariae plants that recruited after the 2018 wildfires to be flowering and fruiting by 2023, indicating a primary juvenile period of less than 5 years (BRW, DDA pers. obs. 2023). Given the semi-arid conditions of the Pilliga, characterised by moderate to low rainfall and slow fuel accumulation, it seems unlikely fire frequencies could drop below 5 years, even with climate change. Overall, A. mariae’s rapid growth to reproductive maturity, ability to withstand both high- and low-severity fires, and tendency to form fire-retardant thickets suggest that the populations can likely tolerate a wide range of fire frequencies and intensities, and may be resilient to expected changes to fire regimes under ACC.

Data availability

The data that support this study will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgements

Appreciation is extended to the Aboriginal traditional owners of the lands on which we conducted our site surveys. We thank Michael Murphy, Adam Fawcett, Rita Enke and Bernadette Lai for advice on site selection and assistance in facilitating research within the NSW Parks estate. Past students of the University of New England unit, ‘Ecology of Australian Vegetation’ (ECOL311/511), are thanked for assisting with sampling of seedbank and reproductive data during field trips to the Pilliga between 2018 and 2023. Warm appreciation is extended to Kelsey Elliott and Bob Wright for providing comments on the draft manuscript. Open access publishing was facilitated by the University of New England, as part of the Wiley – University of New England agreement, via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

References

Arditto PA (1982) Deposition and diagenesis of the Jurassic Pilliga sandstone in the southeastern Surat Basin, New South Wales. Journal of the Geological Society of Australia 29(1–2), 191-203.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Baskin JM, Baskin CC (2004) A classification system for seed dormancy. Seed Science Research 14(1), 1-16.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker BM, Walker S (2015) Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software 67(1), 1-48.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Bousfield CG, Lindenmayer DB, Edwards DP (2023) Substantial and increasing global losses of timber-producing forest due to wildfires. Nature Geoscience 16(12), 1145-1150.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Bowman DMJS, Kolden CA, Abatzoglou JT, Johnston FH, van der Werf GR, Flannigan M (2020) Vegetation fires in the Anthropocene. Nature Reviews Earth & Environment 1, 500-515.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Bowman D, Williamson GJ, Price OF, Ndalila MN, Bradstock RA (2021a) Australian forests, megafires and the risk of dwindling carbon stocks. Plant, Cell & Environment 44, 347-355.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Bowman DMJS, Williamson GJ, Gibson RK, Bradstock RA, Keenan RJ (2021b) The severity and extent of the Australia 2019–20 Eucalyptus forest fires are not the legacy of forest management. Nature Ecology & Evolution 5, 1003-1010.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Bradstock RA (2010) A biogeographic model of fire regimes in Australia: current and future implications. Global Ecology and Biogeography 19(2), 145-158.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Burrows GE, Alden R, Robinson WA (2018) The lens in focus – lens structure in seeds of 51 Australian Acacia species and its implications for imbibition and germination. Australian Journal of Botany 66(5), 398-413.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Calviño-Cancela M, Lorenzo P, González L (2018) Fire increases Eucalyptus globulus seedling recruitment in forested habitats: effects of litter, shade and burnt soil on seedling emergence and survival. Forest Ecology and Management 409, 826-834.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Chamorro D, Moreno JM (2019) Effects of water stress and smoke on germination of Mediterranean shrubs with hard or soft coat seeds. Plant Ecology 220, 511-521.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Cohn JS, Lunt ID, Ross KA, Bradstock RA (2011) How do slow-growing, fire-sensitive conifers survive in flammable eucalypt woodlands? Journal of Vegetation Science 22(3), 425-435.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Cruz O, Riveiro SF, Arán D, Bernal J, Casal M, Reyes O (2021) Germinative behaviour of Acacia dealbata Link, Ailanthus altissima (Mill.) Swingle and Robinia pseudoacacia L. in relation to fire and exploration of the regenerative niche of native species for the control of invaders. Global Ecology and Conservation 31, e01811.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Cunningham CX, Williamson GJ, Bowman DMJS (2024a) Increasing frequency and intensity of the most extreme wildfires on Earth. Nature Ecology & Evolution 8, 1420-1425.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Cunningham CX, Williamson GJ, Nolan RH, Teckentrup L, Boer MM, Bowman DMJS (2024b) Pyrogeography in flux: reorganization of Australian fire regimes in a hotter world. Global Change Biology 30(1), e17130.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Di Giuseppe F, Vitolo C, Barnard C, Libertá G, Maciel P, San-Miguel-Ayanz J, Villaume S, Wetterhall F (2024) Global seasonal prediction of fire danger. Scientific Data 11(1), 128.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Dodson JR, Wright RVS (1989) Humid to arid to subhumid vegetation shift on Pilliga sandstone, Ulungra Springs, New South Wales. Quaternary Research 32(2), 182-192.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Erickson TE, Dwyer JM, Dalziell EL, James JJ, Munoz-Rojas M, Merritt DJ (2023) Unpacking the recruitment potential of seeds in reconstructed soils and varying rainfall patterns. Australian Journal of Botany 71, 353-370.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Etchells H, O’Donnell AJ, McCaw WL, Grierson PF (2020) Fire severity impacts on tree mortality and post-fire recruitment in tall eucalypt forests of southwest Australia. Forest Ecology and Management 459, 117850.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Fensham RJ, Laffineur B, Browning O (2024) Fuel dynamics and rarity of fire weather reinforce coexistence of rainforest and wet sclerophyll forest. Forest Ecology and Management 553(10), 121598.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Gibson MR, Richardson DM, Marchante E, Marchante H, Rodger JG, Stone GN, Byrne M, Fuentes-Ramírez A, George N, Harris C, Johnson SD, Roux JJL, Miller JT, Murphy DJ, Pauw A, Prescott MN, Wandrag EM, Wilson JRU (2011) Reproductive biology of Australian acacias: important mediator of invasiveness? Diversity and Distributions 17(5), 911-933.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Gordon CE, Price OF, Tasker EM, Denham AJ (2017) Acacia shrubs respond positively to high severity wildfire: implications for conservation and fuel hazard management. Science of The Total Environment 575, 858-868.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Hodgkinson KC, Oxley RE (1990) Influence of fire and edaphic factors on germination of the arid zone shrubs Acacia aneura, Cassia nemophila and Dodonaea viscosa. Australian Journal of Botany 38(3), 269-279.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hughes L, Westoby M (1990) Removal rates of seeds adapted for dispersal by ants. Ecology 71(1), 138-148.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ireland C, Andrew MH (1995) Ants remove virtually all western myall (Acacia papyrocarpa Benth.) seeds at Middleback, South Australia. Australian Journal of Ecology 20(4), 565-570.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Irlbeck NA, Hume ID (2003) The role of Acacia in the diets of Australian marsupials ? A review. Australian Mammalogy 25(2), 121-134.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Jefferys EA, Fox BJ (2001) The diet of the Pilliga mouse, Pseudomys pilligaensis (Rodentia: Muridae) from the Pilliga Scrub, Northern New South Wales. Proceedings of The Linnean Society of New South Wales 123, 89-99.

| Google Scholar |

Keeley JE (2009) Fire intensity, fire severity and burn severity: a brief review and suggested usage. International Journal of Wildland Fire 18(1), 116-126.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Knox KJE, Clarke PJ (2012) Fire severity, feedback effects and resilience to alternative community states in forest assemblages. Forest Ecology and Management 265, 47-54.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Landesmann JB, Tiribelli F, Paritsis J, Veblen TT, Kitzberger T (2021) Increased fire severity triggers positive feedbacks of greater vegetation flammability and favors plant community-type conversions. Journal of Vegetation Science 32(1), e12936.

| Google Scholar |

Le Breton T, Schweickle L, Dunne C, Lyons M, Ooi M (2023) Fire frequency and severity mediate recruitment response of a threatened shrub following severe megafire. Fire Ecology 19, 67.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Leino MW, Edqvist J (2010) Germination of 151-year old Acacia spp. seeds. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution 57, 741-746.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Lenth RV (2016) Least-squares means: the R package lsmeans. Journal of Statistical Software 69, 1-33.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Letnic M, Dickman CR, McNaught G (2000) Bet-hedging and germination in the Australian arid zone shrub Acacia ligulata. Austral Ecology 25(4), 368-374.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Moreno JM, Oechal WC (1991) Fire intensity and herbivory effects on postfire resprouting of Adenostoma fasciculatum in southern California chaparral. Oecologia 85, 429-433.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Murphy MJ, Jones HA, Koen T (2021) A seven-year study of the response of woodland birds to a large-scale wildfire and the role of proximity to unburnt habitat. Austral Ecology 46(7), 1138-1155.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Norris EH, Mitchell PB, Hart DM (1991) Vegetation changes in the Pilliga forests: a preliminary evaluation of the evidence. Vegetatio 91, 209-218.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ooi MKJ (2012) Seed bank persistence and climate change. Seed Science Research 22(S1), S53-S60.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ooi MKJ, Denham AJ, Santana VM, Auld TD (2014) Temperature thresholds of physically dormant seeds and plant functional response to fire: variation among species and relative impact of climate change. Ecology and Evolution 4(5), 656-671.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Palmer HD, Denham AJ, Ooi MKJ (2018) Fire severity drives variation in post-fire recruitment and residual seed bank size of Acacia species. Plant Ecology 219, 527-537.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Parra A, Moreno JM (2018) Drought differentially affects the post-fire dynamics of seeders and resprouters in a Mediterranean shrubland. Science of The Total Environment 626, 1219-1229.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Pausas JG, Leverkus AB (2023) Disturbance ecology in human societies. People and Nature 5(4), 1082-1093.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Pound LM, Ainsley PJ, Facelli JM (2015) Dormancy-breaking and germination requirements for seeds of Acacia papyrocarpa, Acacia oswaldii and Senna artemisioides ssp. × coriacea, three Australian arid-zone Fabaceae species. Australian Journal of Botany 62(7), 546-557.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Sabiiti EN, Wein RW (1987) Fire and Acacia seeds: a hypothesis of colonization success. The Journal of Ecology 75(4), 937-946.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Sakaguchi S, Bowman DMJS, Prior LD, Crisp MD, Linde CC, Tsumura Y, Isagi Y (2013) Climate, not Aboriginal landscape burning, controlled the historical demography and distribution of fire-sensitive conifer populations across Australia. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 280(1773), 20132182.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Tokushima H, Jarman PJ (2010) Ecology of the rare but irruptive Pilliga mouse, Pseudomys pilligaensis. III. Dietary ecology. Australian Journal of Zoology 58(2), 85-93.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Tozer MG (1998) Distribution of the soil seedbank and influence of fire on seedling emergence in Acacia saligna growing on the central coast of New South Wales. Australian Journal of Botany 46(6), 743-755.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Wright BR, Clarke PJ (2018) Germination biologies and seedbank dynamics of Acacia shrubs in the Western Desert: implications for fire season impacts on recruitment. Australian Journal of Botany 66(3), 278-285.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Wright BR, Fensham RJ (2017) Fire after a mast year triggers mass recruitment of slender mulga (Acacia aptaneura), a desert shrub with heat-stimulated germination. American Journal of Botany 104(10), 1474-1483.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Wright BR, Fensham RJ (2018) Fire timing in relation to masting: an important determinant of post-fire recruitment success for the obligate-seeding arid zone soft spinifex (Triodia pungens). Annals of Botany 121(1), 119-128.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Wright BR, Zuur AF (2014) Seedbank dynamics after masting in mulga (Acacia aptaneura): implications for post-fire regeneration. Journal of Arid Environments 107, 10-17.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Wright BR, Latz PK, Zuur AF (2016) Fire severity mediates seedling recruitment patterns in slender mulga (Acacia aptaneura), a fire-sensitive Australian desert shrub with heat-stimulated germination. Plant Ecology 217, 789-800.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Wright BR, Albrecht DE, Silcock JL, Hunter J, Fensham RJ (2019) Mechanisms behind persistence of a fire-sensitive alternative stable state system in the Gibson Desert, Western Australia. Oecologia 191, 165-175.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Wright BR, Laffineur B, Royé D, Armstrong G, Fensham RJ (2021) Rainfall-Linked megafires as innate fire regime elements in arid Australian Spinifex (Triodia spp.) grasslands. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 9, 666241.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Zuur AF, Leno EN, Elphick CS (2010) A protocol for data exploration to avoid common statistical problems. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 1(1), 3-14.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |