Effect of early gut microbiota intervention using pre-designed poultry microbiota substitute on broiler health and performance

Advait Kayal A * , Sung J. Yu A , Thi Thu Hao Van B , Yadav S. Bajagai

A * , Sung J. Yu A , Thi Thu Hao Van B , Yadav S. Bajagai  A and Dragana Stanley

A and Dragana Stanley  A

A

A

B

Abstract

The designer gut microbiota in broiler chickens is a novel concept involving post-hatch inoculation of chicks with beneficial or commensal non-pathogenic bacteria as an inoculum. This process aims to control gut colonisation by administering desirable microbiota to prevent access to harmful and pathogenic bacteria via competitive exclusion.

This study aimed to assess the impact of one such intervention on broiler gut microbiota, microbial diversity and growth performance.

The intervention involved spraying the newly hatched chicks with a commercially available mix of non-pathogenic bacterial species isolated from chicken intestine.

Bodyweight gain was significantly higher in the treated group, and performance measures showed improvement. Beta diversity analysis showed a significant difference in the gut microbiota between the control and treatment groups.

The study demonstrated the effects and potential benefits of early intervention to influence gut microbial composition and improve the uniformity across the flock and enhance broiler health and performance.

This study has highlighted the complexity of microbiota dynamics and the need for further research to fully understand the implications of designer gut microbiota in poultry production.

Keywords: alpha diversity, Aviguard, chicken, controlled colonisation, designer microbiota, gut colonisation, intestinal microbiota, microbiota.

Introduction

The poultry industry, a vital agricultural sector in any country, plays a significant role in the Australian economy, with over 800 commercial farms contributing to food production and meat processing (Poultry Hub Australia 2023). The research and development efforts relating to chicken industry focus on enhancing productivity and bird welfare, as well as increasing the yield of poultry products (Poultry Hub Australia 2023). The current developments are also concentrating on developing farming practices and promoting the usage of innovative technologies to increase the sustainability and efficiency of the industry.

However, the industry faces challenges such as disease outbreaks, affecting animal welfare and production efficiency (Food and Agriculture Organization – The AVIS Consortium 2020). Necrotic enteritis-, spotty liver- and leaky gut-related mortality is a major concern for the chicken industry (De Meyer et al. 2019; Hussein et al. 2020). These are often addressed using antibiotics (Hafez and Attia 2020). Overcrowding at the farms increases stress levels, increasing the susceptibility of the birds to these infections (Gomes et al. 2014). Promoting free-range and open-range production systems while employing other sustainable farming practices, such as reducing antibiotics usage, is essential to improve the living conditions for the birds and enhance bird welfare.

Healthy gut microbiota in chickens significantly contributes to overall health and well-being. The gut microbiota is a diverse community of microorganisms colonising the gastrointestinal tract that alters the chemical environment and morphology (Stanley et al. 2014), and assists in the breakdown and absorption of nutrients, including complex carbohydrates and fibres (Pan and Yu 2014). Microbial communities can influence feed efficiency and contribute to the development of the immune system (Stanley et al. 2014) and assist by acting as a protective barrier and preventing colonisation by pathogens via competitive exclusion (La Ragione and Woodward 2003).

Unnatural industrial hatching practices separating the newly hatched chicks from the mother hens can lead to significantly variable gut microbiota despite using the same food and providing the birds with the same environment. Maternal influence provides exposure to maternal faecal matter, which can help colonise the gut by native maternal chicken microbiota (Stanley et al. 2013). Faecal microbiota transplant has been shown to have a positive effect on the gut strength, morphology and short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) profile (Metzler-Zebeli et al. 2019). Exposure of newly hatched chicks to desired Lactobacillus strains at a very high level can also result in vigorous gut colonisation and cause a reduction in richness and diversity by affecting the maturation of gut microbiota (Wilkinson et al. 2020). One study has reported rapid colonisation and maturation of microbiota in four commercial flocks of layer chickens from day 1 to 70 weeks of age (Joat et al. 2023), whereas others (Baldwin et al. 2018; Wilkinson et al. 2020) have reported a small window for permanent microbiota modulation.

In this study, we exposed the newly hatched birds to a predesigned commercial microbial inoculum, developed as a predefined mix of common commensal bacteria from healthy and well-performing birds, by spraying the inoculum on newly hatched chicks similarly to standard vaccine spray delivery. After spraying with the microbiota inoculum product, we studied differences in performance and cloacal swab microbial community between treated and untreated birds.

Materials and methods

Animal trial

This poultry trial was performed as approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Central Queensland University under Approval number 0000023123. The trial was performed in the facilities available at the Central Queensland Innovation and Research Precinct (CQIRP), Central Queensland University, Rockhampton, Australia. The experiment involved hatching 320 Ross broiler chickens and randomly allocating them into 32 pens (10 birds per pen). The pens were randomised and assigned into two groups (160 birds each), control and treatment (Aviguard).

The Aviguard product (Aviguard®, Lallemand Animal Nutrition, Canada) was diluted in autoclaved water according to the recommended dosage and mixed with a blue-coloured food dye before spraying. The control birds (CTR) were sprayed with the autoclaved water and dye mix. The sprayed birds were placed in a box to encourage them to preen the liquid from each other.

The conditions, such as temperature and light within the shed, were maintained according to the Aviagen (2018) guidelines. Commercially available diet (Laucke Mills, Greenock, SA, Australia) and water were provided ad libitum. The bodyweights of individual birds and the average feed intake per pen were recorded once every week. On Day 28, cloacal swabs were collected from all the birds. The swabs were frozen and stored at −80°C till further processing for 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing.

DNA extraction, sequencing and bioinformatics

The isolation of genomic DNA from the samples followed the lysis protocol established by Yu and Morrison (2004), and subsequent purification was performed using a DNA mini spin column (Enzy-max LLC, CAT# EZC101, Kentucky, USA). NanoDrop One UV-Vis spectrophotometer (ThermoFisher Scientific, MA, USA) was used to assess the quantity and quality of the extracted DNA.

Specifically designed dual-indexed primers attached with spacers, barcodes and the Illumina sequencing linkers were used for the amplification of the V3–V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene (Fadrosh et al. 2014). The forward primer used was Pro341F (5′-CCTACGGGNBGCASCAG-3′), whereas the reverse primer was Pro805R (5′-GACTACNVGGGTATCTAATCC-3′). The amplified 16S DNA was purified using the AMPure XP kits and sequenced using the Illumina MiSeq platform, employing a 2 × 300 bp paired-end configuration. Raw DNA sequences were demultiplexed using Cutadapt (Martin 2011), and analysed using Quantitative Insights into Microbial Ecology 2 (QIIME 2) (Bolyen et al. 2019). Reads with a minimum Phred score of 20 across the length of 200 nt were selected for further downstream analysis. DADA2 was used for the filtering, denoising and removing chimeras (Callahan et al. 2016). SILVA ver. 138.1 database (Quast et al. 2013; Pfeiffer et al. 2014) was used to assign the taxa. The amplicon sequence variant (ASVs) data were clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) at 98% similarity level.

Statistical analyses

Bodyweight and feed-intake data were analysed with ANOVA using GraphPad Prism 9, assuming individual birds as observational units and pens as experimental units. Feed conversion ratio (FCR) was calculated from average bodyweight and average feed intake per pen. Phyloseq (ver. 1.42.0; https://joey711.github.io/phyloseq/; McMurdie and Holmes 2013), Microeco (ver. 1.10.0; https://chiliubio.github.io/microeco/; Liu et al. 2021), and SIAMCAT (ver. 4.0.3; https://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/SIAMCAT.html; Wirbel et al. 2021) R packages were used for downstream analysis and the visualisation of the microbiota data. The marker genera in the treatment and control groups were predicted using the machine-learning tool SIAMCAT. The relative abundance data were log-standardised, and the machine-learning models were cross-validated with SIAMCAT default evaluation function to calculate cross-validation error in the form of a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and area under the ROC curve value. The Phyloseq package was used to calculate the alpha diversity indicators. The alpha diversity significance was calculated with the Mann–Whitney test by using GraphPad Prism 9. Beta diversity was visualised using PCoA of UniFrac distance matrices and compared with PERMANOVA by using the Microeco package (ver. 1.10.0; https://chiliubio.github.io/microeco/) in R.

Sequence accession number

The raw sequence data are available from NCBI SRA database with accession number PRJNA1068794 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/1068794).

Results

Animal health and performance

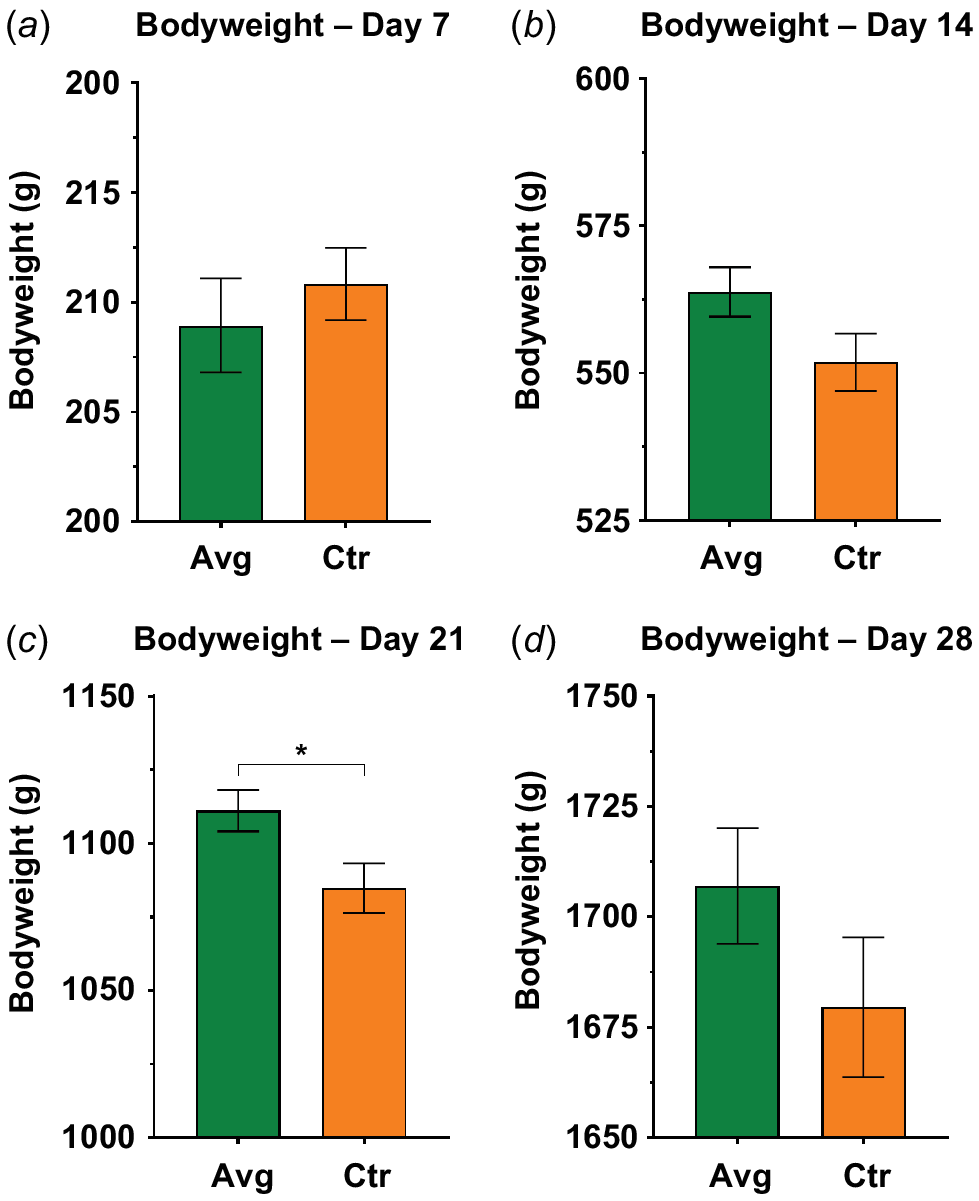

The average bodyweight of the birds in the aviguard (AVG) group was significantly higher than in control (CTR) (2.39%, CTR = 1085 g, AVG = 1111 g, P = 0.0173) on Day 21 (Fig. 1). On Day 28, 1.6% increase in bodyweight in AVG group was recorded, but this was not statistically significant (CTR = 1680 g, AVG = 1707 g). The FCR for the AVG group did not show any significant change compared with the control group (Supplementary Fig. S1) but was numerically lower than that for the control group by 0.015 and 0.006 points on Day 21 and Day 28 respectively. The coefficient of variation (%) showed that from Week 2 to Week 4, the Aviguard birds were more similar in bodyweight than were those in the control group (Table 1).

Bodyweight data for Aviguard and control groups collected through the trial. (a) shows bodyweight data for day 7. (b), (c) and (d) show bodyweight data for day 14, day 21 and day 28 respectively. *P = 0. 0173.

| Week | Control | Aviguard | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Week 1 | 9.878 | 12.96 | |

| Week 2 | 11.07 | 9.151 | |

| Week 3 | 9.602 | 7.801 | |

| Week 4 | 11.68 | 9.483 |

The core microbiota analysis of the cloacal swab samples showed a high prevalence of Escherichia–Shigella in the overall flock (Fig. S2). The other genera that were abundant in the flock included Enterococcus, Corynebacterium, Paenibacillus, Olsenella, Acinetobacter, Lactobacillus, Romboutsia, Bifidobacterium, Clostridia UCG-014 and Collinsella (Fig. S2).

Alpha and beta diversity modulation

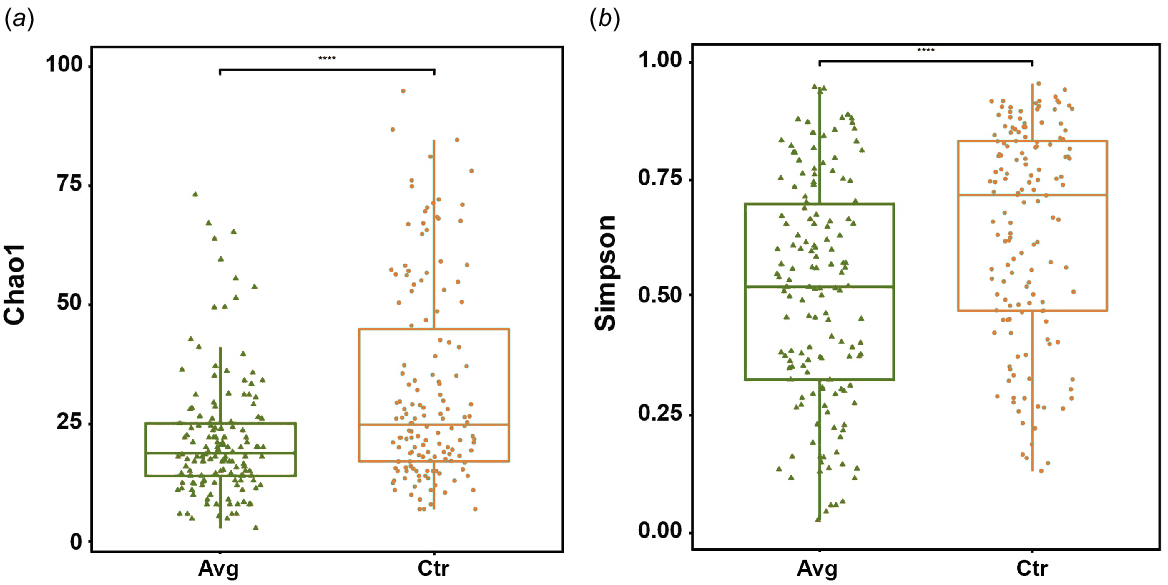

There was a significant (P < 0.001) reduction in cloacal swab microbiota richness and diversity in the Aviguard-treated group (Fig. 2a, b).

Alpha diversity plots showing the richness and diversity using (a) the Chao1 matrix and (b) the Simpson entropy matrix.

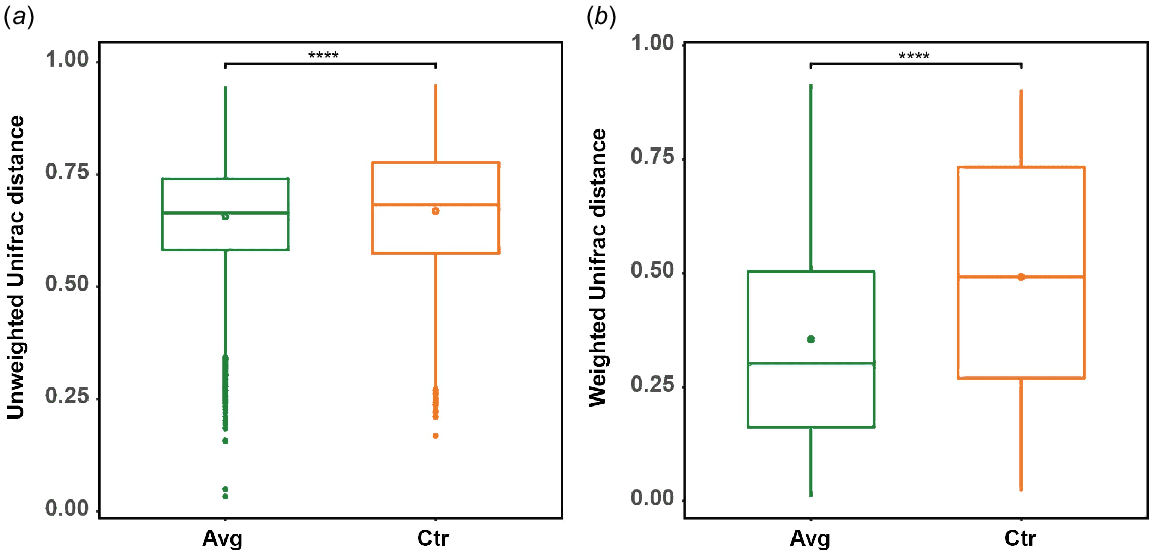

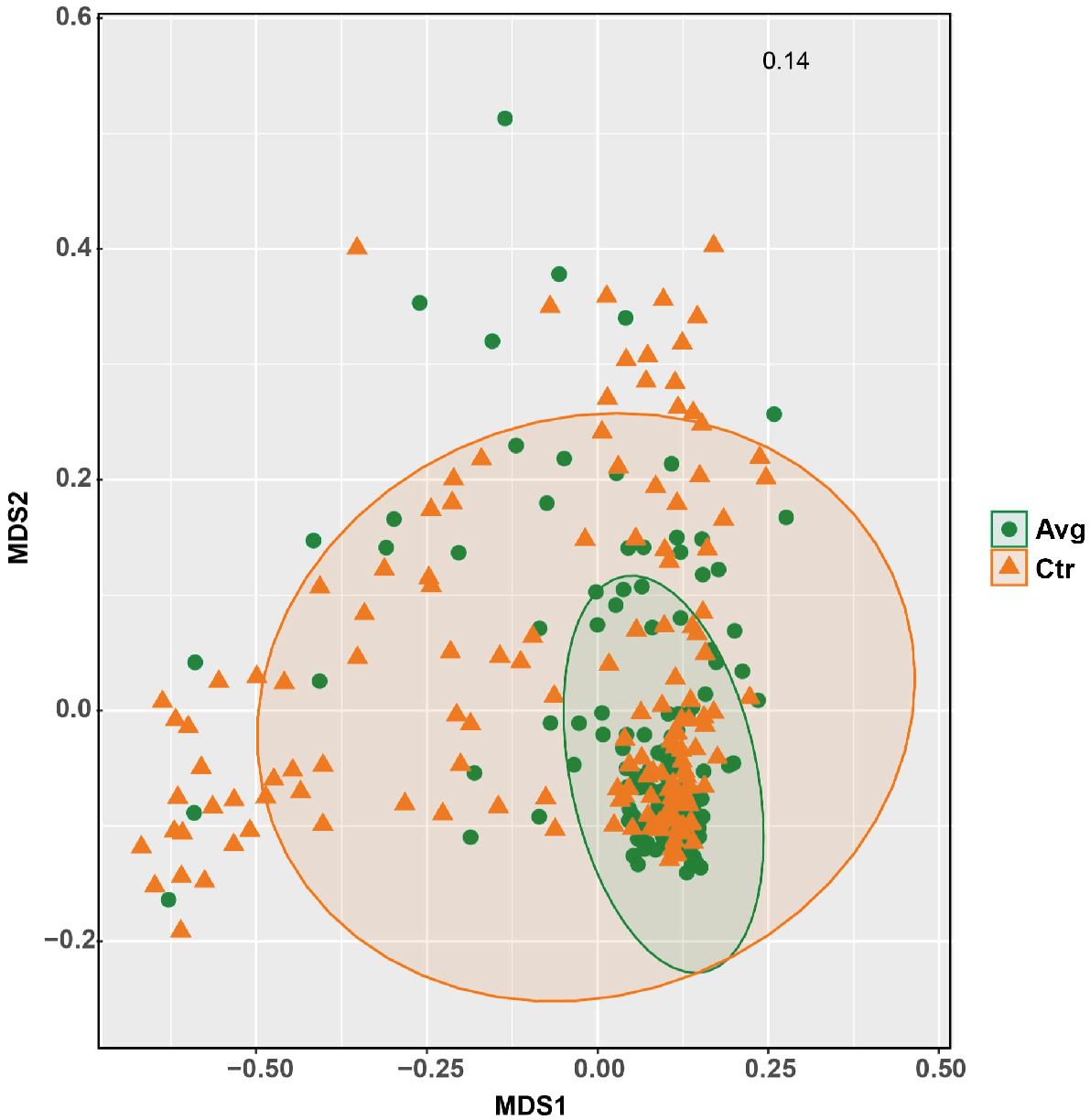

Permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) showed that there was a significant (P < 0.001) difference between the microbiota observed in the control birds as compared to the treated birds by using both weighted and unweighted UniFrac distances. There was a significantly lower sample-to-sample distance between AVG-treated samples than between CTR samples by using unweighted (Fig. 3a) and weighted (Fig. 3b) UniFrac. However, the differences between CTR and AVG groups were more prominent when using weighted Unifrac distance; thus, abundance played a higher role than the taxonomy membership. The increased uniformity of AVG samples can also be observed using NMDS plot (Fig. 4).

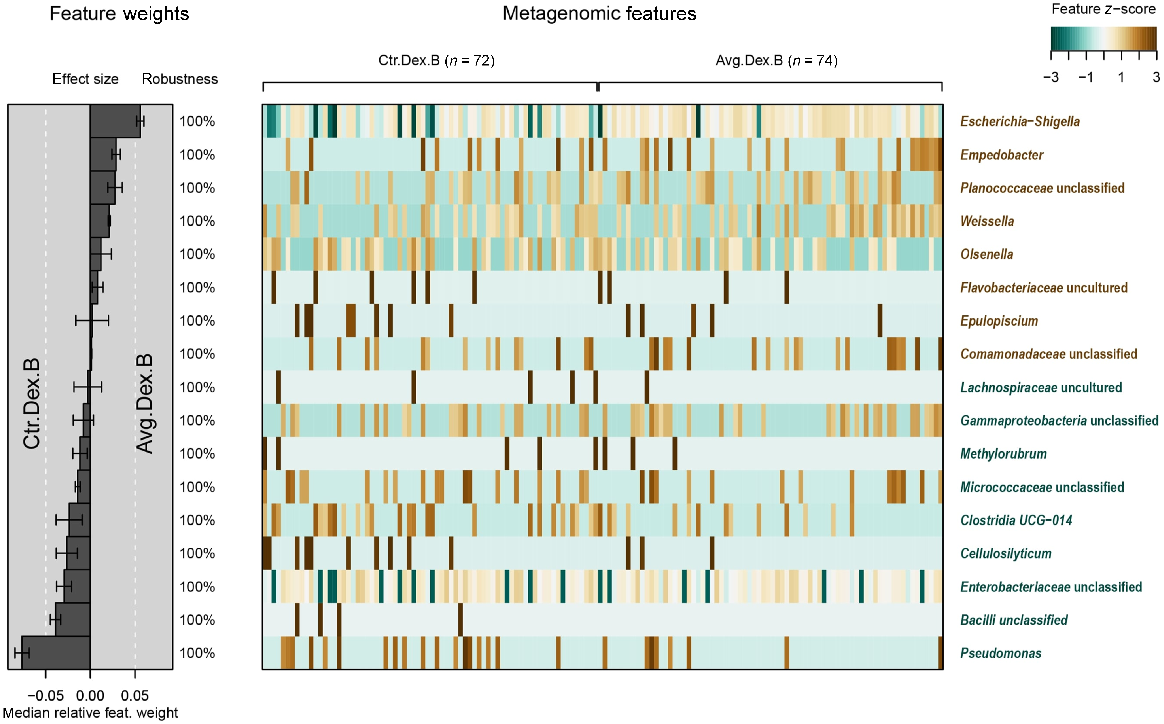

Differences in microbiota

Taxonomic level differences were evaluated using Statistical Inference of Associations between Microbial Communities And host phenoTypes (SIAMCAT), a robust statistical modelling and biomarker extraction tool (Fig. 5). A machine-learning model was constructed from the genus-level data, and the LASSO regression model was trained after normalisation and cross-validation. The model interpretation plot in Fig. 5 shows the top selected genera for the control and AVG group with model weights and their robustness and a heatmap with feature z-score.

Discussion

The colonisation of the chicken intestine, like in other animals, starts immediately after hatch or birth. Ignoring very minimal microbial load in ovo, the chick is immediately exposed to a heavy microbial load post-hatch. It has been reported that the first few days of life determine intestinal membership, because the species that arrive into the gut first shape the gut environment to suit their own needs and show competitive behaviour, preventing colonisation of other species. The dynamics of this process is not yet fully understood because of the complexity and variation of microbial communities at a species and even at the strain level. Interestingly, these first few days of a chick’s life shape bird health, behaviour and productivity.

Considering that poultry production practices entirely remove maternal influence on the chick, including access to maternal microbiota, early post-hatch intervention opens a window of opportunity to shape bird microbiota towards increasing proportion of beneficial and non-pathogenic commensal membership. Aviguard is, to our knowledge, the only product on the poultry market that replaces maternal microbiota to chicks, offering very diverse yet non-pathogenic species originating from the guts of healthy chickens.

In this study, we report improved weight and FCR in birds treated with AVG, indicating the benefits of colonisation control. Control birds showed higher weight only during the first week, after which AVG birds were consistently heavier, significantly at the end of Week 3. FCR did not show any noticeable difference in the first 2 weeks, but it has shown marginal improvement at the end of Weeks 3 and 4. Considering comparable mortality, this improvement in performance and bird weight, which became apparent after Week 2, is encouraging and could play a significant role in large commercial production systems. Several studies reported significant improvements in performance in animal trial facilities (Dame-Korevaar et al. 2020) and commercial production systems with an immense number of birds (Kayal et al. 2022).

Aviguard significantly affected the alpha diversity in the cloacal microbial community. Glendinning et al. (2022) showed that cecal microbiota transplant can increase the alpha diversity in the treated birds. However, this study collected samples from Day 1 to Day 7, whereas our study included sample collection on Day 28. One study has shown that Aviguard increased alpha diversity in broilers (Dame-Korevaar et al. 2020).

Whereas most other studies reported AVG-induced increases in diversity, our trial shows a reduction in cloacal swab samples. We can argue that the reduced diversity observed in the cloacal swabs is not necessarily observed or comparable with other gut sections. Previous studies have shown that diversity can increase in one section while reducing in another, demonstrating the complexity of gut microbiota dynamics (Kayal et al. 2022; Joat et al. 2023). A comprehensive study by Bajagai et al. (2024, p. 13) concluded, ‘The microbial richness and diversity tended to decrease with age in the upper gut, remained constant in the small intestine, and increased with age in the lower gut’.

It is likely that early administration of diverse microbial inoculum restricted the colonisation by the environmental bacteria through competitive exclusion, helping create a balanced and beneficial designer gut microbiota. Colonisation could prove challenging to reproduce in different poultry sheds having distinct pathogenic and environmental microbiota. At-hatch administration of a diverse microbial inoculum could be particularly helpful in sheds with higher pathogen levels.

While it is a commonly held notion that increased richness and diversity can benefit the host, this concept is being challenged as a common misconception in microbiota studies (Shade 2017). According to Shade (2017), diversity does not provide an accurate picture of the health of the microbial community while ignoring the stability and productivity of a community with lower diversity. Others have argued that diversity should be considered as just one of many factors, among stability, structure and function of the community (Johnson and Burnet 2016). An increase in the richness and diversity, if occurring as a result of gut colonisation by opportunistic pathogens, may lead to infections and inflammation of the gut.

Diverse microbial inoculum could be used to secure the colonisation and maturation of the gut, assuring a more homogenous development between sheds and flocks. Our data presented in Fig. 5 support this argument, showing that using either microbiota membership (unweighted UniFrac) or microbiota abundance data, the application of AVG at-hatch reduced the distance (difference) between microbial communities in treated birds, thus increasing the uniformity. This trend of AVG-reduced bird-to-bird variation is confirmed in the weight data presented in Table 1. More uniform flocks are preferred in the poultry industry, particularly processing facilities where the outlier birds often get discarded.

The sequencing also showed a high presence of Escherichia in the flock, including both control and AVG groups, and this was significantly higher in the AVG group. The high relative abundance of Escherichia–Shigella detected in the birds at 4 weeks (Day 28) did not result in unusual mortality during the trial or any mortality in Week 4. Despite a higher abundance of Escherichia–Shigella genera in the treatment group, the AVG group showed better performance across all of the parameters measured, than did the control. AVG is a product containing non-pathogenic strains typically present in poultry gut, and it is highly probable that the species representing Escherichia–Shigella genera in this study were non-pathogenic. A large-scale study, observing regularly collected data from hatch to over 70 weeks in layers showed high temporal variation in microbiota, where dominant genera were shifting on a weekly basis (Joat et al. 2023), and another study confirmed this trend across all gut sections in layer chickens during the period from Day 0 to 70 weeks (Bajagai et al. 2024).

Conclusions

The present study focused on the differences in microbiota maturation owing to Aviguard intervention by using cloacal swabs. Because of the continual movement of the intestinal content via peristalsis, cloacal swabs sample microbiota representing a mix of the communities inhabiting all upstream gut sections, and, together with caecum, are consistently the most diverse sampled intestinal origin (Joat et al. 2023). However, as opposed to caecum, cloacal swabs represent the best sampling origin for identifying a range of pathogens present in upstream gut sections (Joat et al. 2023). Thus, we used high-powered swab sequencing (n = 320) to pinpoint commercially relevant species alterations emerging from predesigned microbiota seeding intervention. Investigating changes in all gut sections would be beneficial in identifying modifications in the hotspots of pathogenesis for each commercially significant pathogen. Finally, to understand 16S amplicon-based microbiota data, we must understand the limitations and benefits of the methodology. Although 16S-based microbial community data provide reliable insights into microbial community structure, it cannot reliably resolve and identify taxa at the species level. This methodology detects a majority of the microbial community that responds to primers selected in the study. Thus, this methodology can be considered as an estimation of the major part of intestinal microbiota and does not distinguish the taxa at the species level. So, to better understand the effects of any treatment aiming to improve intestinal microbiota, a large number of trials under a range of diets and environmental conditions are needed to identify reproducible trends and benefits.

Data availability

The raw sequence data is available from NCBI SRA database with accession number PRJNA1068794 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/1068794).

Conflicts of interest

Lallemand Inc. provided a scholarship for A.K. The authors declare no other conflicts of interest.

Declaration of funding

Lallemand Inc. provided a scholarship for A.K. The project was co-funded by Central Queensland University.

Author contributions

D. S.: conceptualization, methodology, software, formal analysis, review, editing and funding acquisition. A. K.: data curation, investigation, formal analysis, original draft preparation, review and editing. Y. S. B.: methodology, visualization, software, formal analysis, review and editing. T. T. H. V.: review and editing. S. Y.: reviewing and editing. All authors approved the final version of the paper.

Acknowledgements

The data were analysed using the Marie Curie High-Performance Computing System at Central Queensland University. We wish to acknowledge and appreciate the help Jason Bell provided in all aspects of High-Performance Computing.

References

Aviagen (2018) Ross 308 – Broiler management Handbook. Available at https://aviagen.com/eu/brands/ross/products/ross-308 [accessed 28 September 2024]

Bajagai YS, Van TTH, Joat N, et al. (2024) Layer chicken microbiota: a comprehensive analysis of spatial and temporal dynamics across all major gut sections. Journal of Animal Science and Biotechnology 15(1), 20.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Baldwin S, Hughes RJ, Hao Van TT, et al. (2018) At-hatch administration of probiotic to chickens can introduce beneficial changes in gut microbiota. PLoS ONE 13(3), e0194825.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Bolyen E, Rideout JR, Dillon MR, et al. (2019) Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nature Biotechnology 37(8), 852-857.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Callahan BJ, McMurdie PJ, Rosen MJ, et al. (2016) DADA2: high-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nature Methods 13(7), 581-583.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Dame-Korevaar A, Kers JG, van der Goot J, et al. (2020) Competitive exclusion prevents colonisation and compartmentalisation reduces transmission of ESBL-producing Escherichia coli in broilers. Frontiers in Microbiology 11, 566619.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

De Meyer F, Eeckhaut V, Ducatelle R, et al. (2019) Host intestinal biomarker identification in a gut leakage model in broilers. Veterinary Research 50(1), 46.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Fadrosh DW, Ma B, Gajer P, et al. (2014) An improved dual-indexing approach for multiplexed 16S rRNA gene sequencing on the Illumina MiSeq platform. Microbiome 2(1), 6.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Food and Agriculture Organization – The AVIS Consortium (2020) Poultry diseases – Bacterial infections. Available at http://www.fao.org/ag/AGAinfo/programmes/en/empres/GEMP/avis/poult-over/tools/0-tabl-bacterial-infections.html [accessed 22 March 2021]

Glendinning L, Chintoan-Uta C, Stevens MP, et al. (2022) Effect of cecal microbiota transplantation between different broiler breeds on the chick flora in the first week of life. Poultry Science 101(2), 101624.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Gomes AVS, Quinteiro-Filho WM, Ribeiro A, et al. (2014) Overcrowding stress decreases macrophage activity and increases Salmonella Enteritidis invasion in broiler chickens. Avian Pathology 43(1), 82-90.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Hafez HM, Attia YA (2020) Challenges to the poultry industry: current perspectives and strategic future after the COVID-19 outbreak. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 7, 516.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hussein EOS, Ahmed SH, Abudabos AM, et al. (2020) Effect of antibiotic, phytobiotic and probiotic supplementation on growth, blood indices and intestine health in broiler chicks challenged with Clostridium perfringens. Animals 10(3), 507.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Joat N, Bajagai YS, Van TTH, et al. (2023) The temporal fluctuations and development of faecal microbiota in commercial layer flocks. Animal Nutrition 15, 197-209.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Johnson KV-A, Burnet PWJ (2016) Microbiome: should we diversify from diversity? Gut Microbes 7(6), 455-458.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Kayal A, Stanley D, Radovanovic A, et al. (2022) Controlled intestinal microbiota colonisation in broilers under the industrial production system. Animals 12(23), 3296.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

La Ragione RM, Woodward MJ (2003) Competitive exclusion by Bacillus subtilis spores of Salmonella enterica serotype Enteritidis and Clostridium perfringens in young chickens. Veterinary Microbiology 94(3), 245-256.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Liu C, Cui Y, Li X, et al. (2021) microeco: an R package for data mining in microbial community ecology. FEMS Microbiology Ecology 97(2), fiaa255.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Martin M (2011) Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet.journal 17(1), 10-12.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

McMurdie PJ, Holmes S (2013) phyloseq: an R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS ONE 8(4), e61217.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Metzler-Zebeli BU, Siegerstetter S-C, Magowan E, et al. (2019) Fecal microbiota transplant from highly feed efficient donors affects cecal physiology and microbiota in low- and high-feed efficient chickens. Frontiers in Microbiology 10, 1576.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Pan D, Yu Z (2014) Intestinal microbiome of poultry and its interaction with host and diet. Gut Microbes 5(1), 108-119.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Pfeiffer S, Pastar M, Mitter B, et al. (2014) Improved group-specific primers based on the full SILVA 16S rRNA gene reference database. Environmental Microbiology 16(8), 2389-2407.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Poultry Hub Australia (2023) Meat Chicken (Broiler) Industry. Available at https://www.poultryhub.org/production/meat-chicken-broiler-industry [accessed 10 June 2023]

Quast C, Pruesse E, Yilmaz P, et al. (2013) The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Research 41(D1), D590-D596.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Shade A (2017) Diversity is the question, not the answer. The ISME Journal 11(1), 1-6.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Stanley D, Geier MS, Hughes RJ, et al. (2013) Highly variable microbiota development in the chicken gastrointestinal tract. PLoS ONE 8(12), e84290.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Stanley D, Hughes RJ, Moore RJ (2014) Microbiota of the chicken gastrointestinal tract: influence on health, productivity and disease. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 98(10), 4301-4310.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Wilkinson N, Hughes RJ, Bajagai YS, et al. (2020) Reduced environmental bacterial load during early development and gut colonisation has detrimental health consequences in Japanese quail. Heliyon 6(1), e03213.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Wirbel J, Zych K, Essex M, et al. (2021) Microbiome meta-analysis and cross-disease comparison enabled by the SIAMCAT machine learning toolbox. Genome Biology 22(1), 93.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Yu Z, Morrison M (2004) Improved extraction of PCR-quality community DNA from digesta and fecal samples. BioTechniques 36(5), 808-812.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |