Sheep producers report docking tails shorter than recommended, knowledge–practice gap, and inconsistent length descriptions: an Australian survey

Madeleine E. Woodruff A * , Carolina A. Munoz

A * , Carolina A. Munoz  B , Grahame J. Coleman

B , Grahame J. Coleman  A , Rebecca E. Doyle

A , Rebecca E. Doyle  C and Stuart R. Barber

C and Stuart R. Barber  B

B

A

B

C

Abstract

In Australia, it is a common practice to dock sheep tails, to reduce breech soiling and flystrike. According to research, for docking to provide the optimal benefit, tails should be left at a length that covers the vulva in ewes and to an equivalent length in males. Docking tails shorter than recommended increases the risk of perineal cancers, arthritis and prolapse. Research indicates that some producers dock tails shorter than recommended, up to 57% in surveys and up to 86% in on-farm data.

This study aimed to ascertain the current tail docking length, practices, knowledge and attitudes of Australian sheep producers.

A national survey was conducted using online, hardcopy and computer-assisted telephone interview (CATI) modes of delivery (n = 547).

Fifty-seven percent (205/360) of online and hardcopy survey participants chose short tail images to represent their practice, where the vulva was exposed. Although 88% (135/154) of CATI participants described their sheep tail lengths to be covering the vulva, participants equated the length to leaving two tail joints (40%, 54/134) and/or 50 mm (29%, 39/134), both of which have been previously found to be too short to cover the vulva. There was a high awareness of the recommended length (75.7%, 408/539) and 60% (234/390) of participants described it accurately. Significant associations were identified between choosing the short tail image and (1) describing the recommended length to be shorter than it is (P < 0.01), (2) being a producer in South Australia (P < 0.05), and (3) practicing mulesing (P < 0.01). Tail docking is important for producers to reduce flystrike, but docking at their chosen length held more importance than following the recommendation. Participants tended to agree that shearers preferred short tails. Docking tails with a hot knife or rubber rings were the most common methods used.

These results indicated that short tail docking remains a sheep-welfare issue for Australian sheep, and that a knowledge–practice gap exists for some producers.

Future research in the space of tail length could address the identified knowledge–practice gap, attitudes, and individual barriers to benefit sheep welfare and the industry.

Keywords: animal husbandry, attitudes, best-practice, farmers, guidelines, knowledge, lamb marking, sheep management, welfare.

Introduction

Most sheep breeds in the Australian commercial meat and wool industry naturally have long tails; however, it is common for their tails to be partially removed or docked at a young age (Howard and Beattie 2018; Sloane 2018; Sheep Producers Australia 2022). This practice is primarily performed to reduce the risk of cutaneous myasis or flystrike (Webb Ware et al. 2000; Shephard et al. 2022), a disease caused when blowflies lay larvae on sheep and developing maggots attack the sheep causing subsequent infection, significant pain, and death, if not treated quickly. Flystrike is a costly and multi-factor animal welfare issue (Shephard et al. 2022), and because of the extensive nature of sheep production in Australia, prevention methods including tail docking are heavily relied on (Woodruff et al. 2020). Surveys have indicated that tails are most commonly docked using a hot knife (gas-heated), the second-most common method is elastrator bands or rings, whereas a sharp knife or shears are used less commonly (Howard and Beattie 2018; Sloane 2018; Sloane and Walker 2022). One survey found that the hot knife was used more by Merino wool and meat–wool producers, whereas rubber rings were used more by meat-focused enterprises (Howard and Beattie 2018). The use of pain relief specifically for the tail docking procedure has not been common historically and is not mandatory for lambs less than 6 months old (Animal Health Australia 2016). Few surveys have captured pain relief use related to tail docking, one captured willingness to adopt pain relief for tail docking (Howard and Beattie 2018), where 39% of producers expressed they would use pain relief for tail docking were it available. However, a recent survey indicated that the use of pain relief may be becoming more common, with 60% of Merino producers utilising pain relief at tail docking (Colvin 2022). There are various pain relief options available, including Numnuts® (https://numnuts.au/), a rubber ring applicator with built-in injection of local anaesthetic lignocaine, which is available and in use for tail docking and castration. The topical anaesthetic Trisolfen® is most commonly used for the mulesing procedure (surgical removal of wool-bearing skin on the breech and tail), alongside tail docking by using the hot knife; there are also oral and injectable analgesics (Meloxicam) available but they are less commonly used (Colvin et al. 2022; Sloane and Walker 2022). Excluding Trisolfen®, these pain relief options have been registered for use by commercial producers only over the past 10 years.

On the basis of the considerable body of research into flystrike prevention and how tail docking length factors into incidence and risk of poor health outcomes, there is a recommended minimum length to optimise sheep welfare. It is recommended to dock tails to ensure an ewe’s vulva is covered (Animal Health Australia 2016), which is approximately equal to leaving three joints of the tail intact. Scientific research demonstrates that this length not only reduces the risk of flystrike (Gill and Graham 1939; Riches 1941, 1942; Graham et al. 1947), but when compared with shorter tail lengths, also decreases the risk of cancers (Swan et al. 1984), prolapses (Windels 1990; Thomas et al. 2003), and arthritis (Lloyd et al. 2016), and improves the rate of healing (Johnstone 1944). This length was also somewhat of a compromise because several of the early studies found that tails consisting of four joints, approximately 100 mm in length, incurred the lowest flystrike incidence (Riches 1941, 1942) and this length recommendation was published in at least one newspaper in 1943 (McGarry 1943). However, it was noted that producers disapproved of a longer docked tail because of beliefs that it would increase dag formation, or faecal and urine soiling, and beliefs regarding mating interference (Riches 1942; Graham et al. 1947). It was also found that shearing and crutching inefficiency increased with this longer length of tail (Graham et al. 1947; Scobie et al. 1999; Fisher and Gregory 2007). Within and among these studies, multiple tail length descriptions were used. These included tail lengths described in relation to the vulva and its commissures (Gill and Graham 1939; Riches 1941; Johnstone 1944), joints (Riches 1941, 1942), length (Riches 1941, 1942; Johnstone 1944), amount of bare area underneath the tail (Johnstone 1944), and caudal fold attachment (Swan et al. 1984), without clear consistency among the measures.

Research into sheep tail length has identified a consistent, and in some cases high, level of sheep tails being docked shorter than recommended in Australia and in other countries known for sheep production. Industry surveys over the past two decades have demonstrated that between 22% and 55% of Australian producers report docking at shorter than the recommended length (Reeve and Walkden-Brown 2014a, 2014b; Howard and Beattie 2018; Sloane 2018; Colvin 2022). Studies measuring tails of lamb carcasses at an abattoir (Lloyd et al. 2016) and adult ewes on farm (Munoz et al. 2019) found that 22% of tails assessed had less than three coccygeal joints (Lloyd et al. 2016) and 86% of ewes had tails too short to cover the vulva (Munoz et al. 2019). A follow-up study involving the same participants from Munoz et al. (2019) used in-depth interviews and found that 57% of producers described their tail docking length to be shorter than recommended (Woodruff et al. 2020). Short tail docking length has also been found to be common in New Zealand and Chile, with 59% (Kerslake et al. 2015) and 56% (Larrondo et al. 2018) of producers reporting the practice in surveys. The reasons behind docking at a short length included high importance placed on flystrike and/or faecal soiling prevention (Kerslake et al. 2015; Larrondo et al. 2018; Woodruff et al. 2020), shearer approval (Woodruff et al. 2020, 2021) and reducing shearing/crutching time and cost (Kerslake et al. 2015), tradition (Kerslake et al. 2015) and beliefs of improved mating (Larrondo et al. 2018). Knowledge of the recommended length was positively associated with Australian producers reporting their length to be appropriate (Woodruff et al. 2020). Shearers are crucial labourers for sheep producers and sheep factors can affect their efficiency, which directly affects their own income, and therefore willingness to accept work on properties where sheep are more difficult or inefficient to shear. To avoid losing regular shearers, some producers have been influenced to dock tails short (Woodruff et al. 2021). This persistence of short tail docking compromises the welfare and health of sheep and incurs financial cost for producers (Doyle 2018); however, competing priorities, attitudes and lack of awareness appear to be contributing to the continuation of short tail docking.

The varied way in which tail length has been historically described and measured has continued in research and industry publications. Although the optimal tail docking length was recognised through scientific research conducted from the 1930s, and can be found across industry publications (Munro and Evans 2009; Suter 2016; Australian Wool Innovation 2023) and husbandry guides (Meat and Livestock Australia 2013; Lloyd and Playford 2022), there have been some conflicting literature/publications that may have led to or perpetuated misinterpretations and practices. These include publications from the development of the mulesing procedure, which prescribed tails to be docked at the ‘top of the vulva’ (Beveridge 1935; Gill and Graham 1939), and subsequent research recommended a shorter-docked tail for radically mulesed sheep (Watts et al. 1979). More recently, a best-practice Australian Wool Innovation (AWI) manual stated that the recommended docking length for mulesed wethers and rams is to cover the anus, which would approximately equal two or fewer joints being left intact (Australian Wool Innovation 2020). Similarly, even though the recommended length is reflected in the Australian Animal Welfare Guideline to leave a tail long enough to cover the vulva in ewes and equivalent length in males, the Standard requires just one joint of the tail to remain after docking (Animal Health Australia 2016). The discrepancy extends to state-level Codes of Practice, where most reflect the guideline; however, Queensland and South Australia Codes of Practice retain only the one-joint requirement (Johnston et al. 2023).

Unsurprisingly, the way tail length has been described by researchers and producers in industry and welfare research also varies. For example, industry surveys using just one description of docking length, such as the number of tail joints (Howard and Beattie 2018; Colvin et al. 2022), length in relation to the vulva (Reeve and Walkden-Brown 2014a, 2014b), or number of tail joints and having the tip of the vulva as a separate independent category (Sloane 2018). In-depth interview data found mismatches between multiple length descriptions provided by producers, where two joints and 50 mm were said to be long enough to cover the vulva by 40% of the participants (Woodruff et al. 2020). The animal-welfare indicator (AWIN) protocol developed and used for on-farm welfare assessment similarly uses just one binary description of sheep tail length (AWIN 2015). Recent research sought to assess the relationships between the common length descriptions used by measuring sheep tails by using multiple methods and found that tails that covered the vulva were longer than 50 mm, on average, by using a ruling device, and contained more than two palpable joints (Woodruff et al. 2023).

Given the persistence of short tail docking in Australia and the potential welfare implications, this study aimed to capture Australian sheep producers’ tail docking length, tail docking practices, knowledge and attitudes towards the recommended length, and to investigate any relationships or associations among farmer factors, current practice, knowledge and attitudes.

Materials and methods

A national survey on flystrike management and husbandry practices was conducted as part of an industry-funded research project on mulesing (Munoz et al. 2022). Collaboration was facilitated by the PhD candidate’s supervisors and the Animal Welfare Science Centre and resulted in the inclusion of specific questions on tail docking practice and length to be used for this study.

Although primarily focused on reaching sheep-meat producers, the survey included various production systems. Eligible participants were Australian adult producers who owned or managed a sheep flock. The aim was to reach/distribute the survey to 20% of the Australian sheep-producer population, approximately 19,687 producers (Meat and Livestock Australia 2023a), to capture a representative sample. From which, it was expected to capture a response rate of approximately 4–18% (157–709/19,687) on the basis of previous relevant research (Coleman et al. 2022; Colvin et al. 2022). The wide variation in response rate appears to be a function of sampling methodology. The survey was distributed in 2021 by using multiple modes, including through the research team’s established connections, industry networks and social media. A market research company (Australian Community Media) was engaged to further disseminate the survey via online links, mailed links and hardcopies, and by conducting computer-assisted telephone interviews (CATI), to achieve a sample size of 300.

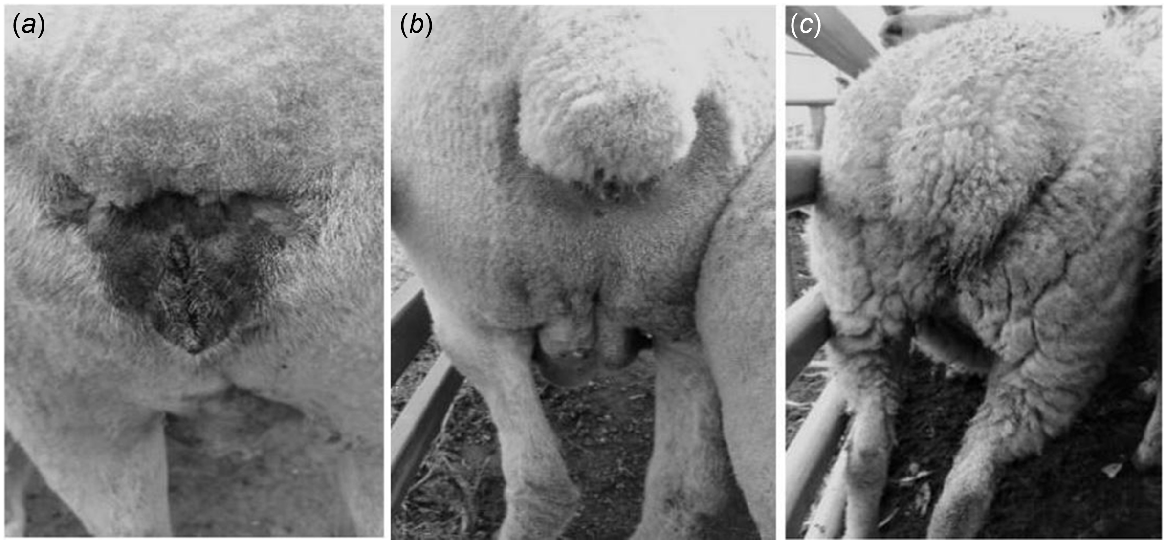

There were 44 survey questions, capturing demographic information (Table 1), current practice (Tables 2, 3), knowledge (Table 2) and attitudes (Table 4). The online/hardcopy surveys required 30–40 min to complete, depending on the level of details provided by the survey participants in the open-ended questions, and the CATI took approximately 25 min. Participants were required to indicate their own tail docking practice by selecting the method used to dock tails, who docked tails and by selecting one of three photographs that best represented their tail docking length (Fig. 1). Each photograph of sheep breeches had different length tails; Image A depicted a tail that is ‘butt-tailed’ where the tail has been docked as short as possible and the vulva and anus are exposed; Image B showed a tail extending halfway down the vulva orifice and the lower commissure of the vulva is visible; and Image C contained a tail completely covering the vulva. The images of tails were chosen as they were photographs taken by the research team as part of a previous project (Munoz et al. 2019), therefore indicative of real on-farm Australian practice. They were in greyscale because of the wide dissemination of the survey in hard copies and to reduce bias of discolouration of perineal skin in Image A. The attitudinal questions captured responses on a Likert scale (1–5) regarding their level of agreement, approval or importance. All questions were asked all participants; however, as an image could not be selected via phone, the CATI participants instead described their tail docking length in three ways, namely, in relation to the vulva, in number of joints and in estimated length measurement (Table 2). These results were analysed separately from the image-based tail length questions. The tail docking questions were developed on the basis of literature and a previous smaller-scale survey ran by the research team (Woodruff et al. 2020), in an attempt to accurately capture current practice, knowledge and attitudes. There was one question in the survey regarding use of pain relief; however, it was specific to the mulesing procedure and, therefore, it is unknown how many participants use pain relief for tail docking because people who did not mules would not have answered this question.

| Question description | Response scale | Label for analyses | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Postcodes condensed into States/Territories | Nominal | State | |

| Gender | 1 = Male 2 = Female 3 = Other/prefer not to say | Gender | |

| What is your age? | 1 = 18–24 2 = 25–34 3 = 35–44 4 = 45–54 5 = 55–64 6 = 65 and over | Age | |

| How long have you farmed sheep? (Years) | Number | Farming experience (years) | |

| What is your highest level of education? | 1 = No formal schooling 2 = Primary school 3 = Secondary school 4 = Technical or further educational institution (including TAFE college) 5 = University or other higher educational institution 6 = Other educational institution, please specify: 7 = Don’t wish to answer | Education level | |

| What is your main farming enterprise? – Selected choice | 1 = Meat-focused enterprise 2 = Meat–wool-focused enterprise 3 = Wool-focused enterprise 4 = Mixed production, please specify: | Main enterprise | |

| Using a scale from 1 (very low) to five (very high), how would you rate the risk of flystrike in your area? | Sliding scale: 1 (very low) to five (very high) | Flystrike risk | |

| Rainfall (annual mm) | Numeric | Rainfall |

| Question description | Response scale | Label for analyses | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Please indicate which image best depicts the length at which you (or your contractor) dock your lambs’ tails. | Image A, B or C | Tail length image | |

| What length do you or your contractor dock lambs’ tails? (Descriptive response, e.g. just covering the vulva, above the vulva etc.)A | Text | Tail length – vulva (CATI) | |

| What is that approximately in inches/mm?A | Numeric | Tail length – inches (CATI) | |

| How many tail joints are left?A | Number | Tail length – joints (CATI) | |

| Is there a recommended tail length? | 1 = Yes 2 = No 3 = Not aware | Recommended length awareness | |

| What is the recommended tail docking length? | Text | Recommended length description | |

| What tail docking method do you (or your contractor) use? | 1 = Rubber rings 2 = Hot knife 3 = Other, please specify: | Method | |

| Who usually docks tails on your farm? | 1 = Myself 2 = A helper (farm staff/family member) 3 = A contractor 4 = Other please specify | Operator |

| Question description | Response scale | Label for analyses | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Do you (or your contractor) currently mules lambs on your farm? | 1 = Yes 2 = Sometimes 3 = No, I have never mulesed my stock 4 = No, but I have in past. Please give details on when: | Mulesed status | |

| If you have no longer mulesed stock, have you changed tail length to compensate? (e.g. make them longer, or shorter?) | 1 = Yes 2 = No 3 = I’m not sure | Tail length change (ceased mulesing) | |

| How? (e.g. increased or decreased the length at which tails were docked) | Text | Tail length change description (ceased mulesing) | |

| Please indicate which image best depicts the length at which you (or your contractor) PREVIOUSLY docked your lambs’ tails while you were still mulesing | Image A, B or C | Tail length change image (ceased mulesing) |

| Question description | Response scale | Label for analyses | |

|---|---|---|---|

| How important is it to dock tails at the recommended length? | 1 = Very unimportant 2 = Unimportant 3 = Neither important nor unimportant 4 = Important 5 = Very important | Importance (recommended length) | |

| For each management practice below, please rate its importance in your operation in relation to flystrike prevention. – Tail docking | As above | Tail docking importance for flystrike | |

| How important is it to dock tails at the length you choose (as specified above)? | As above | Importance of tail docking at chosen length | |

| To what extent do you approve or disapprove of the following procedures/practices carried out on sheep? – Tail docking | 1 = Strongly disapprove 2 = Disapprove 3 = Undecided 4 = Approve 5 = Strongly approve | Approval of tail docking | |

| For each statement below, please select the option on the scale that most closely represents your level of disagreement or agreement with each statement Shearers prefer short docked tails | 1 = Strongly disagree 2 = Disagree 3 = Neither agree nor disagree 4 = Agree 5 = Strongly agree | Shearers prefer short tails | |

| Tails the same length as the vulva make crutching difficult | As above | Tails the same length as the vulva make crutching difficult | |

| Tails the same length as the vulva make shearing difficult | As above | Tails the same length as the vulva make shearing difficult |

The images of tail lengths in the online and hardcopy surveys that producers could choose from to best represent the tail length of their sheep. (a) a tail that is ‘butt-tailed’ where the tail has been docked as short as possible and the vulva and anus are exposed; (b) a tail extending halfway down the vulva orifice and the lower commissure of the vulva is visible, and (c) a tail completely covering the vulva.

The dependent variables investigated were knowledge of the recommended length, tail length image chosen and accuracy of the description of the recommended length. Where appropriate, and to facilitate analysis, some data and categories were collapsed where the frequency of certain responses was low. The tail length image question was analysed using only Image B and C responses because of the low frequency of Image A selection. Recommended length awareness responses of ‘Not aware’ were combined into ‘No’. Qualitative data were coded into categories by using content analysis. Recommended length descriptions were coded into seven categories, but only two, ‘Accurate’ and ‘Too short’, were used for analyses because of low frequencies in other categories. For example, participants’ descriptions of the recommended length such as ‘covering the vulva’ and/or ‘3 joints of the tail’ were categorised as providing descriptions that were ‘Accurate’. However, participants who described the recommended length as being ‘2 joints’ and/or ‘2 inches’, for example, were categorised as providing descriptions that were ‘Too short’. Postcodes were used to create the variable ‘State’, using the first number of the postcode. Two categories of mulesing status were used for analyses, ‘Yes’ and ‘No’, for which participants who had never or did not currently mules were collapsed into one category.

Statistical Packages for the Social Sciences (IBM Corp. Released 2020. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 27.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp) was used for data analyses. Chi-squared and Fishers exact tests (FET) were used to investigate associations with categorical demographic variables and current practices. Where relevant, overall chi-squared results were followed by Bonferroni-corrected pairwise comparisons within groups. t-tests were used to assess significant differences relating to independent numeric variables. One-sample t-tests were used to assess significant differences between the attitudinal responses on a 5-point Likert-scale questions and the neutral value of 3; Cohen’s d (d) was used to measure effect size (Cohen 1988). It is suggested that values are loosely interpreted as small (d = 0.2), medium (d = 0.5), and large (d = 0.8) (Lakens 2013). Paired t-tests were used to compare participants’ attitudinal Likert-scale responses.

Principal-component analysis (PCA) using a varimax rotation was used to determine which questions were assessing a common attitude and could therefore be condensed into a composite variable. Loadings greater than 0.33 ensured inclusion in the composite variable (Tabachnick and Fidell 2007). Cronbach’s alpha was used to assess the reliability of the attitudinal questions’ scale. Reliability was conferred where alpha was greater than 0.7 (DeVellis 2003).

Results

Response rate

Over 6000 producers were contacted directly to complete the survey; however, the additional reach of social media and similar public-forum distribution methods cannot be quantified. Of the 610 surveys returned, there were 547 usable responses; therefore, an approximate response rate of 9.1% can be calculated (547/6000). Of the different modes of survey completion, 30% (165/547) completed the survey via CATI, and the remaining participants completed the survey via hardcopies or online. Regarding the CATI method, 962 people were contacted, of which 804 fit the criteria for inclusion and there was a usable response rate of 20.5% (165/804). The response rate for participants contacted by mail was 8% (242/3000) (Munoz et al. 2022). However, not all participants responded to all questions; so, as a result, percentages are in relation to the number of completed responses per question.

Demographic results

Demographic results are summarised in Table 5. Participants were most commonly from New South Wales (28.7%, 157/547), Victoria (28%, 153/547) and South Australia 19.9%, 109/547); there were fewer participants from Western Australia (14.3%, 78/547), Tasmania (4.8%, 26/547) and Queensland (4.2%, 23/547) and just one participant from the smallest territory, being Australian Capital Territory. The two most common age groups of participants were aged 55–64 years old (31.6%, 173/537) and 65 years and over (30.6%, 166/537). Twenty-one percent (114/537) of participants were aged 45–54 years of age, and 10.4% (57/537) were between 35 and 44 years of age. Only 5% (75/537) of participants were aged between 18 and 34. Of the three options provided, majority of participants identified as male (88.1%, 472/536), 11.4% (61/536) identified as female and 0.6% selected ‘Other/Prefer not to say’ (3/536). Most of the participants had either university (34.9%, 186/533), secondary school (30.4%, 162/533), or technical institution-level education (28.9%, 154/533).

| Question | Response option/category | n | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | NSW | 157 | 28.7 | |

| Vic | 153 | 28.0 | ||

| SA | 109 | 19.9 | ||

| WA | 78 | 14.3 | ||

| Tas | 26 | 4.8 | ||

| Qld | 23 | 4.2 | ||

| ACT | 1 | 0.2 | ||

| Complete responses | 547 | |||

| Gender | Male | 472 | 88.1 | |

| Female | 61 | 11.4 | ||

| Other/prefer not to say | 3 | 0.6 | ||

| Complete responses | 536 | |||

| Blank | 11 | |||

| Age | 55–64 | 173 | 32.2 | |

| 65 and over | 166 | 30.9 | ||

| 45–54 | 114 | 21.2 | ||

| 35–44 | 57 | 10.6 | ||

| 25–34 | 25 | 4.7 | ||

| 18–24 | 2 | 0.4 | ||

| Complete responses | 537 | |||

| Blank | 10 | |||

| Education | University or other higher educational institution | 186 | 34.9 | |

| Secondary school | 162 | 30.4 | ||

| Technical or further educational institution (including TAFE college) | 154 | 28.9 | ||

| Other educational institution, please specify: | 13 | 2.4 | ||

| Don’t wish to answer | 11 | 2.1 | ||

| Primary school | 7 | 1.3 | ||

| No formal schooling | 0 | 34.9 | ||

| Complete responses | 533 | |||

| Blank | 14 |

Enterprise details

Participants largely ran meat–wool-focused enterprises (44.5%, 236/544), followed by mixed production enterprises (27%, 145/544), meat-focused enterprises (14.7%, 80/544) and wool-focused enterprises (13.8%, 75/544) (Table 6). The average number of years participants had farmed sheep was 40 years, ranging from 2 to 180 years. Responses greater than 70 years were excluded from analyses because these were not expected to be personal years of experience, and, in some cases, may have been indicative of generational experience (Table 7). On average, flock size was 3445 sheep (Tables 6 and 7). Responses of 80,000 sheep or greater were expected to be errors in data entry and were excluded from analyses (4/547). The perceived flystrike risk tended towards medium–high, with 70.9% of participants indicating levels between 3 and 5. Just 6.6% of participants indicated a very low, level 1, flystrike risk (Table 6). The average annual rainfall was 546 mm (Table 7); for analysis, responses less than 100 mm were excluded (4/536) (see http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/maps/rainfall/?variable=rainfall&map=totals&period=12month®ion=nat&year=2021&month=06&day=30). Over half of the respondents indicated that they mulesed their sheep (53%, 289/545); 44.2% (241/545) did not currently mules their sheep, which consisted of those who had never mulesed their sheep (23.3%, 127/241) and those who had in the past, but had since ceased (20.9%, 114/241) (Table 8). Mulesing was practiced significantly (P < 0.05) more by participants with meat–wool enterprises (66.8%, 157/235) than by those with meat-focused enterprises (10.4%, n = 8/77).

| Question | Response option/category | n | n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main enterprise | Meat–wool enterprise | 242 | 44.5 | |||

| Mixed production | 147 | 27.0 | ||||

| Meat-focused enterprise | 80 | 14.7 | ||||

| Wool-focused enterprise | 75 | 13.8 | ||||

| Complete responses | 544 | |||||

| Blank | 3 | |||||

| Perceived flystrike risk | 1 (very low) | 36 | 7.2 | |||

| 2 | 75 | 15.0 | ||||

| 3 | 126 | 25.3 | ||||

| 4 | 144 | 28.9 | ||||

| 5 (very high) | 118 | 23.6 | ||||

| Complete responses | 499 | |||||

| Blank | 48 | |||||

| Flock-size category | <1000 | 121 | 22.4 | |||

| 1000–2300 | 145 | 26.9 | ||||

| 2300–4650 | 139 | 25.7 | ||||

| >4650 | 131 | 24.3 | ||||

| >80,000 | 4 | 0.7 | ||||

| Complete responses | 540 | |||||

| Blank | 7 | |||||

Summary table of flock-size, rainfall and years of farming experience including the mean, minimum and maximum values.

| Item | n | n (%) | Mean | Maximum | Minimum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flock size | 543 A | 100.0 | 3444.7 | 37,200 | 0 | |

| Rainfall (annual mm) | 532 | 100.0 | 546.6 | 1500 | 150 | |

| Farming experience (years) | 547 | 100.0 | 39.6 | 180.0 | 2.0 |

| Question | Response options | n | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mulesed status | Yes | 289 | 53 | |

| No, I have never mulesed my stock | 127 | 23.3 | ||

| No, but I have in the past | 114 | 20.9 | ||

| Sometimes | 15 | 2.8 | ||

| Complete responses | 545 | |||

| Blank | 2 | |||

| Tail length change (ceased mulesing) | No | 160 | 29.30 | |

| Yes | 30 | 5.50 | ||

| I’m not sure | 12 | 2.20 | ||

| Complete responses | 202 | |||

| Blank | 345 | 63.1 | ||

| Tail length change description (ceased mulesing) | Longer | 21 | 70 | |

| Shorter | 5 | 17 | ||

| Unclear | 4 | 13 | ||

| Complete responses | 30 |

Tail length and docking method

Participants’ tail docking practices are summarised in Table 9. To answer the research question on Australian sheep producers’ current tail docking length, it was most common for participants to select Image B to best represent their tail docking length (57%, 205/360), followed by Image C (39%, 142/360), with 11 participants selecting Image A. As summarised in Table 10, CATI participants most commonly described their tail docking length to be covering the vulva (88%, 135/154), which was equated to 49.8 mm in length, on average, and most commonly equated to two tail joints (40%, 54/134), followed by three joints (29%, 39/134). There was a small proportion who stated they docked tails above the vulva (6.5%, 10/154), which was equated to 36.5 mm in length, on average, and between zero and three joints.

| Question | Response option | n | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tail length image | B | 205 | 56.9 | |

| C | 142 | 39.4 | ||

| A | 11 | 3.1 | ||

| A, B | 1 | 0.3 | ||

| B, C | 1 | 0.3 | ||

| Complete responses | 360 | |||

| Blank | 22 | |||

| Method | Hot knife | 333 | 61.8 | |

| Rubber rings | 165 | 30.6 | ||

| Other | 24 | 4.5 | ||

| Rubber rings, hot knife | 15 | 2.8 | ||

| Rubber rings, hot knife and other. | 2 | 0.4 | ||

| Complete responses | 539 | |||

| Blank | 8 | |||

| Operator | Myself | 277 | 51.5 | |

| A contractor | 115 | 21.4 | ||

| A helper (farm staff/family member) | 111 | 20.6 | ||

| Myself, helper | 23 | 4.3 | ||

| Myself, contractor | 9 | 1.7 | ||

| Myself, helper, contractor | 3 | 0.6 | ||

| Complete responses | 538 | |||

| Blank | 9 |

| Vulva comparison | Length (mm) | Number of joints (n) A | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean | 0–1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Unsure | N/A | Blank | ||

| Cover vulva | 135 | 49.8 | 3 | 57 | 39 | 11 | 1 | 20 | 3 | 1 | |

| Above vulva | 10 | 36.5 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Longer | 1 | 97.5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| N/A | 3 | 50.0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | |

| Uncategorisable | 2 | 34.5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Unsure | 3 | 50.0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Blank | 11 | 46.8 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

The results indicated that a high proportion of participants used the hot knife to dock tails (61.8%, 333/539), 30.6% (165/539) used rubber rings and 4.5% (24/539) indicated that they used another method not listed, for example, a knife (n = 16/24), Numnuts® (3/24), or shears (2/24); for two participants, the question was not applicable, and one was unsure. Details on tail stripping are not discussed in this study; however, there were some participants who specified using the TePari® rolling hot iron or similar (3/333), to remove wool bearing skin from the end and/or sides of the tail, which were combined into the hot knife category. The hot knife method was used by most meat–wool enterprises (68.4%, 160/219), mixed-production enterprises (68.5%, 98/143) and wool-focused enterprises (68.5%, 50/73), whereas rubber rings were more commonly used by meat-focused enterprises (67.9%, 53/78). The difference in tail docking method used was significant (P < 0.05) between meat–wool-focused enterprises and meat-focused enterprises. Half of the participants docked tails themselves (51.5%, 277/538), 20.6% (111/538) had a helper such as a staff or family member to dock tails, 21.4% (115/538) had contractors that docked tails, 6.6% (35/538) indicated a combination of some or all options (Table 9). Both non-mulesing and mulesing participants were more likely to dock tails themselves. Participants who did not dock tails themselves were more likely to have a contractor to dock tails if they mulesed, whereas non-mulesing participants were more likely to have a helper to dock tails if they did not dock themselves (P < 0.05) (Table 11).

Knowledge

To answer the research questions relating to Australian sheep producers’ knowledge of the recommended length, 75.7% (408/539) said there was a recommended length, 24.3% (131/539) said there was not a recommended length (35/131) or they were not aware of it (96/131) (Table 12). Overall, 60% (234/390) accurately described the recommended length, 25% (99/390) provided descriptions shorter than it should be, whereas 7% (28/390) described it inaccurately, that is, they provided conflicting descriptions of short lengths they stated were long enough to cover the vulva, for example, ‘covering the vulva, 2 joints’. Equally, 2.2% (n = 12) were unsure or provided uncategorisable descriptions. Five participants described the recommended length to be longer than what it is (Table 12).

| Question | Response option | n | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recommended length awareness | Yes | 408 | 75.7 | |

| No | 131 | 24.3 | ||

| Complete responses | 539 | |||

| Blank | 8 | |||

| Recommended length description | Accurate | 234 | 60.0 | |

| Too short | 99 | 25.5 | ||

| Inaccurate | 28 | 7.2 | ||

| Longer | 5 | 1.3 | ||

| Uncategorisable | 12 | 3.1 | ||

| Unsure | 12 | 3.1 | ||

| Complete responses | 390 | |||

| Blank | 157 |

Relationships

The following results answer the research questions around relationships between farmer factors and current tail docking practice and knowledge of the recommended length. Overall, participants who described the recommended length to be shorter than what it is were more likely to select the Image B than Image C to represent their own tail docking length (P < 0.01) (Table 13). There was a statistically significant (P < 0.01) association between Australian state and tail length image chosen. South Australian participants were more likely to choose the short tail in Image B over Image C (P < 0.05). Similarly, state and knowledge of the recommended length were associated (P < 0.05), where participants in Victoria and South Australia were more likely to know there was a recommended length (P < 0.05) than those in other states. Participants who selected Image C had 43.8 mm higher annual rainfall, on average, than did participants who chose Image B (P < 0.05). Participants who currently mulesed were significantly (P < 0.01) more likely to choose the short tail in Image B than were participants who did not currently mules (those who had never mulesed or had in the past) (Table 14). Of the participants who had mulesed in the past, 26.3% (30/202) reported changing their tail docking length after ceasing mulesing. The majority stated that they increased their tail docking length (70%, 21/30), 16.7% (5/30) said they changed to dock shorter, and the direction of change was unclear in the remaining responses (4/30) (Table 8).

| Item | Option chosen | Recommended length awareness | Recommended length description | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | Accurate | Too short | |||

| Tail length image | Image B (short) | 36 | 165 | 82 | 54 | |

| Image C (recommended) | 14 | 127 | 95 | 12 | ||

| Total | 50 | 292 | 177 | 66 | ||

| Mulesed status | Yes | 64 | 220 | 118 | 53 | |

| No, I have never mulesed my stock | 45 | 81 | 43 | 25 | ||

| No, but I have in the past | 19 | 94 | 67 | 17 | ||

| Sometimes | 3 | 12 | 5 | 4 | ||

| Total | 131 | 407 | 233 | 99 | ||

Attitudes

The following results answer the research question on Australian sheep producers’ attitudes towards tail docking and the recommended length. As summarised in Table 15, tail docking was significantly approved of as a practice (P < 0.01; d = 2.21) and important for the prevention of flystrike (P < 0.01; d = 1.12). It was important to participants to dock tails at their chosen length as either depicted by the image or as described (CATI participants) (P < 0.01; d = 0.88) and to dock tails at the recommended length (P < 0.01; d = 0.7). However, docking at participants’ chosen length was more important than docking at the recommended length (P < 0.01). The three questions regarding approval of tail docking, importance for flystrike prevention and importance to dock at chosen length were condensed into a composite variable by using PCA labelled ‘tail docking attitudes’.

| Statement | n | Mean | Minimum | Maximum | s.d. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Approval of tail docking | 535 | 4.57 | 1 | 5 | 0.71 | |

| Tail docking importance for flystrike | 536 | 4.32 | 1 | 5 | 1.18 | |

| Importance of tail docking at chosen length | 535 | 4.09 | 1 | 5 | 1.23 | |

| Importance (recommended length) | 440 | 3.94 | 1 | 5 | 1.34 | |

| Shearers prefer short tails | 530 | 3.69 | 1 | 5 | 1.00 | |

| Tails the same length as the vulva make shearing difficult | 526 | 2.73 | 1 | 5 | 1.05 | |

| Tails the same length as the vulva make crutching difficult | 529 | 2.76 | 1 | 5 | 1.06 | |

| Shearing attitudes | 532 | 2.74 | 1 | 5 | 1.03 | |

| Tail docking attitudes | 546 | 4.13 | 1 | 5 | 0.98 |

Regarding the influence of and impact on shearers, participants tended to agree that shearers prefer short tails, on average (P < 0.01; d = 0.69). Participants tended to disagree that tails of the same length as the vulva made shearing (P < 0.01; d = −0.23) and crutching (P < 0.01; d = −0.26) difficult. The two questions regarding tails of the same length as the vulva increasing the difficulty of shearing and crutching were condensed into a composite variable by using PCA labelled ‘Shearing attitudes’. The composite variables were used to assess relationships between the attitudes and tail length image choice, awareness and knowledge of the recommended length, where just one of which was significant. There was a significant difference between the shearing attitudes and participant awareness of the recommended tail docking length. Those who were not aware of the recommended length had higher agreement with the shearing-attitudes statements by 0.22, on average (P < 0.05).

Discussion

The results of this study indicated that there remains a substantial proportion of producers who dock sheep tails shorter than the recommended length, despite moderate awareness of and positive attitudes towards the recommendation that tails should be long enough to cover the vulva. Given the results of previous surveys and industry reports on the sheep industry in Australia, this study achieved similar representation of participants regarding proportions from sheep-producing states/territories (Howard and Beattie 2018; Meat and Livestock Australia 2023a), age (Reeve and Walkden-Brown 2014b; Howard and Beattie 2018), gender (Howard and Beattie 2018), rainfall (Reeve and Walkden-Brown 2014b; Howard and Beattie 2018) and flock size (Reeve and Walkden-Brown 2014b; Howard and Beattie 2018).

With 57% of participants choosing Image B to represent their tail docking length, and most CATI participants equating tails covering the vulva to 50 mm in length and to contain two joints, short tail docking is likely to be an ongoing welfare issue for the Australian sheep industry. These results align with those of husbandry-practice surveys over the past 8 years where 44–57% of producers have indicated short tail docking practice, and docking tails to two joints was commonly reported by 36–55% of producers (Howard and Beattie 2018; Sloane 2018; Woodruff et al. 2020; Colvin 2022). Colvin et al. (2022) also found that South Australian producers were more likely to dock tails short. The longitudinal (Reeve and Walkden-Brown 2014a) and cross-sectional (Reeve and Walkden-Brown 2014b) surveys demonstrated a lower prevalence of short tail docking, but that there was an 11.5% increase in short tail docking over an 8-year period (Reeve and Walkden-Brown 2014b). Similar to the CATI results, Reeve and Walkden-Brown (2014a, 2014b) and Woodruff et al. (2020) also found that a high proportion of participants, between 61% and 67%, indicated that their tail docking length covered the vulva. However, Woodruff et al. (2020) found that more than half of the claims were accompanied by descriptions of docked tail length that are not likely to cover the vulva, as found in this study. The level of short tail docking reported in this study also supports animal-based Australian research into tail length and sheep welfare. The results from this survey fit with the results from several studies that included tail length assessments of sheep on farm (Munoz et al. 2019; Woodruff et al. 2023) and at an abattoir (Lloyd et al. 2016) that found that between 22% and 86% of sheep assessed had tails that either did not cover the vulva (Munoz et al. 2019; Woodruff et al. 2023) or had less than three coccygeal joints remaining (Lloyd et al. 2016). This study adds to the body of sheep tail length research conducted over the past 20 years that has highlighted the persistence of self-reported and directly observed tails docked at less than the sheep-welfare recommendation.

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first Australian large-scale study to assess awareness and understanding of the recommended tail docking length. The current results indicated a misalignment between knowledge and practice, with most participants knowing there is a recommended length (74.6%) and accurately describing the recommendation (60%), yet just 39% chose the only image in which the vulva was not exposed (Image C) to represent the tail docking length at their farm. It is significant that over 20% of participants were unaware of the recommended length and that a further 25% of participants described the recommended length to be shorter than it is, despite the longstanding tail docking length recommendation. Participants who used short tail lengths to describe the recommended docking length were also more likely to select the short-tail image to represent their practice, indicating that these participants do not have the knowledge of the recommended length to then be able to implement it in practice. This reflects what has previously been found, namely that knowledge of the recommended length is an important factor in producers reporting to dock tails long enough to cover the vulva (Woodruff et al. 2020). It is well documented in psychological and behavioural research and literature that even though knowledge is an important antecedent of behaviour, simply having the required knowledge does not always translate into individuals’ behaviour (Glanville et al. 2020; Sommerville et al. 2021). This has been demonstrated in behaviour-change research in the human health field such as the case of health practitioner hand-hygiene practices, where educational campaigns have not been effective in increasing adherence to hand-hygiene protocols (Wilson et al. 2011). In their review into behaviour-change research related to animal care and welfare, Glanville et al. (2020) described increased knowledge as an interim outcome of behavioural interventions, which may be required to achieve change and may highlight why change occurs; however, it is not always succeeded by so-called primary, secondary or tertiary outcomes, which are measured behavioural changes and subsequent impact(s). Such examples by Glanville et al. (2020) included intervention strategies that demonstrated that an increase in knowledge of pig pen design (Chilundo et al. 2020) and children’s safe interactions with dogs (Schwebel et al. 2012) were not always followed by changes in behaviour. Having knowledge is just one piece of psychological capability required to perform or change behaviour (Michie et al. 2011). There are various other individual psychological, physical, environmental, and systemic factors and interactions that contribute towards behaviour and behaviour change (Michie et al. 2014). For those participants who knew the recommended length and who could accurately describe it but still chose the short tail in Image B (57% and 46% respectively), there may be other factors at play. These results highlighted a need for further knowledge exchange, education, and communication to clarify the recommended length, and could be one of the factors included in future practice-change research. No relationships were found between formal education level and knowledge of the recommended tail length or current practice; perhaps looking at the level of engagement in industry training and with peer network groups would be more relevant and useful. Some previous research has reported successful behaviour-change approaches utilising existing sheep industry extension networks to address ewe management in Australia (Trompf et al. 2011) and postal, small group, or one-on-one sessions addressing sheep lameness in the UK (Grant et al. 2018). Similar formats could be emulated for the issue of short tail docking, including educational content, involving experts and peers, using various behaviour-change techniques, and taking individual circumstances and variation into account.

When considering factors contributing to the persistence of short tail docking, the inconsistency in tail docking length practice and the recommended length as described by producers, research and industry publications should not be overlooked. An interesting result of this study was that CATI participants described tails of 50 mm and two joints to also cover the vulva. This same misconception that these lengths are sufficient to cover the ewe’s vulva was also found by Woodruff et al. (2020). However, the most recent study measuring Australian sheep tails demonstrated in a small sample of Merino ewes that tails of these lengths are too short to reliably cover the vulva (Woodruff et al. 2023). Despite the recommended length being promoted and distributed by industry for eight decades, the presence of conflicting information can still be found in an industry-published lamb-marking guide in 2020 (Australian Wool Innovation 2020). Given that sheep farming in Australia has a largely family-run business structure (Reeve 2001) and a lot of learning is passed down through generations, as found by Kerslake et al. (2015) regarding husbandry practices in New Zealand, the historical and continuing misinformation could have had lasting impacts on what knowledge and from which sources were absorbed, shared and carried down family farming lines.

Relying on self-reported practice does have inherent challenges that may lead to limitations in the interpretation of results. Tail length is difficult to describe and a measure, as discussed by Woodruff et al. (2023) in a study attempting to find comparisons between the different description and measurement methods. Despite the challenges associated with describing tail length, it was important to capture CATI participants’ current tail docking length. Using multiple methods of description was expected to be the best way to assess CATI participants’ current practice and enable comparison against the recommendation (Animal Health Australia 2016) and recent research (Woodruff et al. 2023). The use of photographic images that had been previously used in tail length research (Woodruff et al. 2020) aimed to avoid variation in participant descriptions among the online and hardcopy participants. However, it is possible that the few images were not representative of all participants’ sheep, and therefore factors not related to tail length potentially influenced choice of image, such as wool length, body condition or mulesed status. These images were presented in greyscale, which may have affected the ability of participants to identify the vulva and whether the tail depicted covered it. Furthermore, it is likely that the tail in Image C contained four joints of the tail, and producers may not have chosen this image because it may have been seen as ‘too long’. However, it is interesting that if this is the case, the question becomes as follows: when given the choice, why do producers choose a tail that is ‘too short’ over a tail that is ‘too long’? And does this translate into practice? Because the images do not indicate which joint the tails are docked to, they were selected to elicit participants’ practice in relation to vulva coverage. To account for these potential limitations in future research, it would be best to include multiple images of various tail lengths and sheep, and include participant written descriptions to allow for cross-referencing of self-reported tail docking length. It would be ideal to conduct on-farm tail length assessments of sheep by using reliable measurement methods to better understand the current state of tail docking length in Australia.

Tail docking remains an important husbandry practice for producers for flystrike risk reduction, as found by previous studies (Kerslake et al. 2015; Larrondo et al. 2018; Woodruff et al. 2020). Regardless of their awareness and accuracy of description of the recommended length, participants indicated that it was important to dock tails at the recommended length. However, it was seen by participants to be more important to dock at their chosen length than at the recommended length. This may indicate that participants feel justified in their current and chosen practice over following the minimum recommendation. Future research could address the issue of how to change these farmer attitudes around the recommended tail docking length, to encourage implementation of the minimum length.

Although producers tended to agree that shearers prefer short tails, they tended to disagree that tails of the same length as the vulva would affect shearing or crutching ease. Past findings have similarly indicated that producers commonly perceive shearers to prefer short tails (Woodruff et al. 2020). It was also found here that producers who docked tails short, reported that shearers’ approval of tail length was more important to them than it was to dock tails at the recommended length (Woodruff et al. 2020). The current research findings differ from previous findings where producers agreed that shearing and crutching sheep was easier the shorter the tails were (Woodruff et al. 2020, 2021). The mean responses to the questions in this study were nearing neutrality on the Likert scale, which may represent the lack of feedback producers have received from shearers or crutchers, and/or little first-hand experiences regarding the impact of tail length on shearing and crutching ease or difficulty, which may have resulted in producers not having strong opinions in either direction. Alternatively, the significant minority of participants who were unaware of the recommended length and how to describe it could further indicate that participants perceive tails that are actually shorter than the length of the vulva to be covering the vulva. Therefore, these lengths are not perceived to make shearing or crutching more difficult. However, there is a possibility that ‘short’ in the relevant question could have been interpreted as docked rather than undocked. Given previous research findings indicating some level of influence of perceived shearer preferences over tail docking length, and particularly short tail docking (Woodruff et al. 2020), producers’ perceptions of tail lengths that shearers prefer may be more relevant than their perception of the impact of tail length on shearing or crutching difficulty. Although studies have also found relationships between short tail docking and the influence of shearer preferences (Woodruff et al. 2020), shearing difficulty (Woodruff et al. 2020, 2021), and cost (Kerslake et al. 2015), further research is required to establish how influential shearers are in short tail docking practice.

Overall, it was most common for participants to use a hot knife to dock their sheep tails, rings were second-most common, and a small proportion of producers used other methods such as a sharp knife or shears. This order follows previous industry-survey findings (Howard and Beattie 2018; Sloane 2018; Sloane and Walker 2022). However, tail docking method was dependent on enterprise focus. Rubber rings were more likely to be used by participants with meat-focused enterprises and the hot knife was more likely to be used among meat–wool-focused enterprises. This trend, also found by Howard and Beattie (2018), is likely to be due to mulesing being more common among wool-producing enterprises with Merinos. The tail is removed as part of the mulesing process. However, tails removed with rubber rings remain intact until sloughing of the tail after days or weeks (Sutherland and Tucker 2011), and therefore this is not a suitable method when coupled with the mulesing procedure. Mulesing status was also related to who docked sheep tails when producers were not performing docking themselves. Who docks the tails is an important factor in tail length research and provides information as to who should be included in practice-change research. From these results, producers themselves are mostly responsible for tail docking and therefore tail length of their sheep. For mulesing participants, contractors were the second-most common tail docking operators. Again, this is understood to be due to the mulesing procedure and hiring of a contracting team, which often includes a tail docking team member or is completed by the mulesing contractor themselves. Therefore, individual enterprise focus, priorities and practices such as mulesing all will influence the way in which and by who sheep tails are docked and must be considered to ensure appropriate and effective outreach, extension or engagement to increase docking tails at the recommended length.

From the results of this study and previous research, the number of sheep at risk of compromised welfare as a result of short-docked tails could be in the tens of millions at present (Karanja 2021; Meat and Livestock Australia 2023b). Tail docking remains an important practice to producers as a method of flystrike prevention; therefore, research to investigate, encourage, support, and maintain docking tails at the recommended length retains relevance and importance for sheep welfare and the industry. For practice-change research, industry extension and outreach, the multiple and varying factors contributing to short tail docking length need to be integrated and accounted for. The finding that approximately a quarter of participants did not know and/or could not accurately describe the recommended length elicits concern that the established optimal length has not reached or been adopted by a significant proportion of producers, yet there is hope that awareness could be raised. In this case, although we acknowledge that knowledge is not the only factor in achieving a higher-welfare tail docking length, it is an important finding to inform future research and industry-wide change.

The multiple ways in which tail length was described by participants and the frequency of contradictory descriptions reflect previous research into the inconsistency and variation of how tail docking length and the recommended length are described by producers and industry publications. Although having multiple tail length descriptors is useful for both practice and research, it is important that the joint, length and other such descriptions are accurately representative of a tail that covers the vulva of ewes and to an equivalent length in males. These results further demonstrated that knowing that it is recommended to cover the vulva, what that looks like in practice and having accurate alternative measurements or descriptors may be key elements in being able to achieve it and should be considered for future research.

Although the recommended tail length was not perceived to affect shearing or crutching, the attitude that shearers prefer shorter tails may be indicative of an ongoing level of influence and impact on tail docking practice. The existence and level of this potential barrier to docking tails at the recommended length will vary among individual producers and regions, and, as such, would need to be considered in the development of any extension strategy. Furthermore, depending on enterprise focus and mulesing status, who should be involved in extension and education should be considered and tailored, such as the involvement of contractors for mulesing enterprises and lamb-marking helpers and/or family members for non-mulesing enterprises.

Conclusions

Given that more than half of the participants indicated that they docked tails shorter than recommended, either by image choice or contradicting length descriptions, the longstanding issue of short tail docking remains a welfare concern for the Australian sheep industry. A proportion of participants was unaware of and/or unable to accurately describe the recommended length and a level of incorrect short-length descriptions that were said to be long enough to cover the vulva. Tail docking remains a relied-on practice for reducing the risk of flystrike, therefore ensuring that producers are supported to dock tails at the optimal length for sheep welfare is relevant and important. The results of this study highlighted that there is still research required in this space to better understand why some producers are docking tails shorter than recommended, to ensure successful extension for improved tail docking length and sheep welfare.

Declaration of funding

This work was supported by a Meat and Livestock Australia Postgraduate Scholarship/Study Award B.STU.2001 (North Sydney, NSW, Australia) and an Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) Scholarship. This work was the result of collaboration with another project funded by Meat and Livestock Australia (B.AWW.0006). The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the paper; or in the decision to publish the results.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the land on which this research took place and pay respect to the Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung, Bunurong people, and Traditional Owners of all country where participants reside and to Elders (past and present) and their families. Special thanks go to colleagues from The University of Melbourne for supporting collaboration and including relevant questions into the survey from an MLA-funded project (B.AWW.0006).

References

Animal Health Australia (2016) Australian animal welfare standards and guidelines for sheep. Available at http://www.animalwelfarestandards.net.au/sheep/ [Accessed 16 May 2018]

Australian Wool Innovation (2020) Plan, prepare and conduct best welfare practice lamb marking procedures. Available at https://www.wool.com/globalassets/wool/sheep/research-publications/welfare/improved-breech-flystrike-management/plan-prepare-conduct-best-practice-lamb-marking-training-guide.pdf [Accessed 21 November 2023]

Australian Wool Innovation (2023) Tail length matters! Beyond the Bale 15–17. Available at https://www.wool.com/news-events/beyond-the-bale/issue-94-march-2023/ [Accessed 14 July 2023]

AWIN (2015) AWIN welfare assessment protocol for sheep. Available at https://doi.org/10.13130/AWIN_SHEEP_2015 [Accessed 21 November 2023]

Beveridge WIB (1935) The Mules operation: prevention of blowfly strike by surgical measures. The Australian Veterinary Journal 11, 97-104.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Chilundo AG, Mukaratirwa S, Pondja A, Afonso S, Alfredo Z, Chato E, Johansen MV (2020) Smallholder pig farming education improved community knowledge and pig management in Angónia district, Mozambique. Tropical Animal Health and Production 52, 1447-1457.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Coleman GJ, Hemsworth PH, Hemsworth LM, Munoz CA, Rice M (2022) Differences in public and producer attitudes toward animal welfare in the red meat industries. Frontiers in Psychology 13, 875221.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Colvin AF, Reeve I, Kahn LP, Thompson LJ, Horton BJ, Walkden-Brown SW (2022) Australian surveys on incidence and control of blowfly strike in sheep between 2003 and 2019 reveal increased use of breeding for resistance, treatment with preventative chemicals and pain relief around mulesing. Veterinary Parasitology: Regional Studies and Reports 31, 100725.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Doyle R (2018) Assessing and addressing on-farm sheep welfare. Meat and Livestock Australia, Melbourne. Available at https://www.mla.com.au/research-and-development/search-rd-reports/final-report-details/Assessing-and-Addressing-On-Farm-Sheep-Welfare/3712

Fisher MW, Gregory NG (2007) Reconciling the differences between the length at which lambs’ tails are commonly docked and animal welfare recommendations. Proceedings of New Zealand Society of Animal Production 67, 32-38 Available at http://creativecommons.org.nz/licences/licences-explained/.

| Google Scholar |

Gill DA, Graham NHP (1939) Studies on fly strike in Merino sheep. No. 2. Miscellaneous observations at ‘Dungalear’ on the influence of conformation of the tail and vulva in relation to ‘crutch’ strike. Journal of the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research 12, 71-82 Available at https://www.cabdirect.org/cabdirect/abstract/19391000688.

| Google Scholar |

Glanville C, Abraham C, Coleman G (2020) Human behaviour change interventions in animal care and interactive settings: a review and framework for design and evaluation. Animals 10, 2333.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Graham NPH, Johnstone IL, Riches JH (1947) Studies on fly strike in Merino sheep. No. 7. The effect of tail-length on susceptibility to fly strike in ewes. Australian Veterinary Journal 23, 31-37.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Grant C, Kaler J, Ferguson E, O’Kane H, Green LE (2018) A comparison of the efficacy of three intervention trial types: postal, group, and one-to-one facilitation, prior management and the impact of message framing and repeat messages on the flock prevalence of lameness in sheep. Preventive Veterinary Medicine 149, 82-91.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Howard K, Beattie L (2018) A national producer survey of sheep husbandry practices. Sydney, Australia. Available at https://www.mla.com.au/research-and-development/search-rd-reports/final-report-details/A-national-producer-survey-of-sheep-and-cattle-husbandry-practices/3709 [Accessed 26 March 2019]

Johnston CH, Richardson VL, Whittaker AL (2023) How well does Australian animal welfare policy reflect scientific evidence: a case study approach based on lamb marking. Animals 13, 1358.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Johnstone IL (1944) The tailing of lambs: the relative importance of normal station procedures. The Australian Veterinary Journal 20, 286-291.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Karanja F (2021) Victorian sheep industry fast facts. Available at https://agriculture.vic.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/698783/Sheep_Fast-Facts_June-2021_Final.pdf [Accessed 18 January 2024]

Kerslake JI, Byrne TJ, Behrent MJ, Maclennan G, Martin-Collado D (2015) The reasons farmers choose to dock lamb tails to certain lengths, or leave them intact. Proceedings of the New Zealand Society of Animal Production 75, 210-214.

| Google Scholar |

Lakens D (2013) Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: a practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Frontiers in Psychology 4, 863.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Larrondo C, Bustamante H, Gallo C (2018) Sheep farmers’ perception of welfare and pain associated with routine husbandry practices in Chile. Animals 8, 225.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Lloyd J, Playford M (2022) A producer’s guide to sheep husbandry practices. p. 45. (Meat and Livestock Australia) Available at https://publications.mla.com.au/login/eaccess?elink=9BC9B12C77F7FDF998604CE [Accessed 11 October 2022]

Lloyd J, Kessell A, Barchia I, Schröder J, Rutley D (2016) Docked tail length is a risk factor for bacterial arthritis in lambs. Small Ruminant Research 144, 17-22.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

McGarry WL (1943) Breech & Tail ‘Strike’ in sheep: prevention & control. pp. 4–10. (Northern Times Carnarvon: WA, Australia). Available at http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article75135530

Meat and Livestock Australia (2023a) State of the industry report: the Australian red meat and livestock industry. (Meat and Livestock Australia: Sydney, NSW, Australia) Available at mla.com.au/soti [Accessed 5 March 2024]

Meat and Livestock Australia (2023b) Sheep projections. pp. 1–7. Meat and Livestock Australia. Available at https://www.mla.com.au/sheepprojections [Accessed 18 January 2024]

Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R (2011) The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change. Implementation Science 6, 42.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Michie S, West R, Campbell R, Brown J, Gainforth H (2014) ‘ABC of behaviour change theories.’ (Silverback Publishing) Available at https://books.google.ie/books/about/ABC_of_Behaviour_Change_Theories.html?id=WQ7SoAEACAAJ&redir_esc=y

Munoz CA, Campbell AJD, Hemsworth PH, Doyle RE (2019) Evaluating the welfare of extensively managed sheep. PLoS ONE 14, e0218603.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Munoz C, Glanville E, Linn B, Kirk B, Tyrell L, Bowles V, Fisher A (2022) Phasing out of mulesing: cost, benefits and opportunities. (Meat and Livestock Australia: Sydney, NSW, Australia). Available at https://www.mla.com.au/research-and-development/reports/2022/Phasing-out-of-mulesing-cost-benefits-and-opportunities/

Munro T, Evans I (2009) Tail length in lambs: the long and short of it. Farming Ahead 211, 88-89.

| Google Scholar |

Reeve I (2001) Australian farmers’ attitudes on rural environmental issues: 1991–2000. (Institute for Rural Futures) Available at https://www.une.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0018/18054/2001-farmer-attitudes.pdf

Reeve I, Walkden-Brown S (2014a) Benchmarking Australian sheep parasite control (WP499) – Longitudinal survey report. Meat and Livestock Australia, Sydney, NSW, Australia. Available at https://www.mla.com.au/research-and-development/search-rd-reports/final-report-details/Animal-Health-and-Biosecurity/Benchmarking-Australian-sheep-parasite-control-WP499-Longitudinal-survey-report/1064

Reeve I, Walkden-Brown S (2014b) Benchmarking Australian sheep parasite control. Cross-sectional survey report. Meat and Livestock Australia. Available at https://www.mla.com.au/contentassets/3703e251ee0849ff84bba2457ff1667e/b.ahe.0069_cross_final_report.pdf

Riches JH (1941) The relation of tail length to the incidence of blowfly strike of the breech of Merino sheep. Journal of the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research, Australia 14, 88-93 Available at https://scholar-google-com.ezp.lib.unimelb.edu.au/scholar?as_q=%22The+Relation+of+Tail+Length+to+the+Incidence+of+Blowfly+Strike+of+the+Breech+of+Merino+Sheep.%22&ie=utf8&oe=utf8.

| Google Scholar |

Riches JH (1942) Further observations on the relation of tail length to the incidence of blowfly strike of the breech of Merino sheep. Journal of the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research, Australia 15, 3-9 Available at https://scholar-google-com.ezp.lib.unimelb.edu.au/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=+Further+observations+on+the+relation+of+tail+length+to+the+incidence+of+blowfly+strike+of+the+breech+of+Merino+sheep+&btnG=.

| Google Scholar |

Schwebel DC, Morrongiello BA, Davis AL, Stewart J, Bell M (2012) The blue dog: evaluation of an interactive software program to teach young children how to interact safely with dogs. Journal of Pediatric Psychology 37, 272-281.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Scobie DR, Bray AR, O’Connell D (1999) A breeding goal to improve the welfare of sheep. Animal Welfare 8, 391-406.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Sheep Producers Australia (2022) Sheep sustainability framework: on-farm insights from the national producer survey. Available at https://www.sheepsustainabilityframework.com.au/globalassets/sheep-sustainability/media/ssf-on-farm-insights-report-web-25oct2022.pdf [Accessed 26 September 2023]

Shephard R, Webb-Ware J, Blomfield B, Niethe G (2022) Priority list of endemic diseases for the red meat industry: 2022 update. (Meat and Livestock Australia) Available at https://www.mla.com.au/research-and-development/reports/2022/priority-list-of-endemic-diseases-for-the-red-meat-industry--2022-update/#:~:text=The updated priority list of,priority diseases reduced to 22

Sloane B (2018) Merino husbandry practices. In ‘Proceedings of the Australian Wool Innovation National Wool Research and Development Technical Update on Breech Flystrike Prevention’. (Australian Wool Innovation) Available at https://www.wool.com/globalassets/start/on-farm-research-and-development/sheep-health-welfare-and-productivity/sheep-health/breech-flystrike/r-and-d-update/2018-summary-bpeachey.pdf

Sommerville R, White J, Rogers S, Ventura B, Hogstad Fjoeran E, Liszewski M, Dwyer C, Bacon H, Coombs T, Langford F, Shields S, Motupalli P, Aworh-Ajumobi M, Singh V, Khanna S, Brown AF, Williams S, Skippen L (2021) ‘Changing human behaviour to enhance animal welfare.’ (CABI International) doi:10.1079/9781789247237.0000

Suter R (2016) Tail length – getting it right is important. Agricultural Victoria. Available at http://agriculture.vic.gov.au/agriculture/livestock/sheep/sheep-notes-newsletters/sheep-notes-autumn-2016/tail-length-getting-it-right-is-important [Accessed 25 May 2018]

Sutherland MA, Tucker CB (2011) The long and short of it: a review of tail docking in farm animals. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 135, 179-191.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Swan RA, Chapman HM, Hawkins CD, Howell JMC, Spalding VT (1984) The epidemiology of squamous cell carcinoma of the perineal region of sheep: abattoir and flock studies. Australian Veterinary Journal 61, 146-151.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Thomas DL, Waldron DF, Lowe GD, Morrical DG, Meyer HH, High RA, Berger YM, Clevenger DD, Fogle GE, Gottfredson RG, Loerch SC, Mcclure KE, Willingham TD, Zartman DL, Zelinsky RD (2003) Length of docked tail and the incidence of rectal prolapse in lambs. Journal of Animal Science 81, 2725-2732.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Trompf JP, Gordon DJ, Behrendt R, Curnow M, Kildey LC, Thompson AN (2011) Participation in Lifetime Ewe Management results in changes in stocking rate, ewe management and reproductive performance on commercial farms. Animal Production Science 51, 866-872.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Watts JE, Murray MD, Graham NPH (1979) The blowfly strike problem of sheep in New South Wales. Australian Veterinary Journal 55, 325-334.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Webb Ware JK, Vizard AL, Lean GR (2000) Effects of tail amputation and treatment with an albendazole controlled-release capsule on the health and productivity of prime lambs. Australian Veterinary Journal 78, 838-842.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Wilson S, Jacob CJ, Powell D (2011) Behavior-change interventions to improve hand-hygiene practice: a review of alternatives to education. Critical Public Health 21, 119-127.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Woodruff ME, Doyle R, Coleman G, Hemsworth L, Munoz C (2020) Knowledge and attitudes are important factors in farmers’ choice of lamb tail docking length. Veterinary Record 186, 319.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Woodruff M, Barber S, Munoz C, Coleman GJ, Doyle R (2021) Shear influence: the relationship between short tail docking in sheep and ease of shearing. In ‘Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on the Assessment of Animal Welfare at the Farm and Group Level: Cork, Ireland’. (Eds L Boyle, K Driscoll). (Wageningen Academic Publishers: Cork, Ireland)

Woodruff M, Munoz C, Coleman G, Doyle R, Barber S (2023) Measuring sheep tails: a preliminary study using length (Mm), vulva cover assessment, and number of tail joints. Animals 13, 963.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |