Comparing shotshell characteristics to optimize aerial removal of wild pigs (Sus scrofa)

Michael J. Lavelle A * , Nathan P. Snow A , Bryan Kluever B , Bruce R. Leland C , Seth M. Cook D , Justin W. Fischer A and Kurt C. VerCauteren A

A * , Nathan P. Snow A , Bryan Kluever B , Bruce R. Leland C , Seth M. Cook D , Justin W. Fischer A and Kurt C. VerCauteren A

A

B

C

D

Abstract

As invasive wild pigs (Sus scrofa) expand throughout North America, wildlife managers are increasingly tasked with implementing strategies for alleviating their damage to anthropogenic and natural resources.

Aerial operations, such as shooting from helicopters, are now commonly used strategies for controlling wild pig populations in the USA. Aerial operators are interested in identifying more effective strategies and tools, such as choke tubes and ammunition that produce the best animal welfare outcomes and reduce the number of shots required, while determining maximum effective shot distances. A strategic approach to evaluating shotshell and firearm options used in aerial operations can help aerial operators understand performance and adjust their techniques accordingly to maximize lethality at various distances.

We evaluated pellet patterns and ballistics from various shotshells and developed a strategy for evaluating lethality and predicting performance in the field at increasing distances.

We found distance to target and shotshell type had the strongest effects on predicting lethality, with probability of a vital impact declining as distances increased and number of pellets per shotshell decreased. We also found that penetration decreased as distances to the target increased; however, heavier pellets were less affected.

Limiting shot distances and shotshell selection are important factors in optimizing aerial operations. Specifically, we recommend 00 buckshot shotshells with ≥12 pellets in situations where shot distances are ≤46 m. None of the shotshells we tested performed well at longer distances (i.e. <0.50 probability of lethal hit and lower penetration).

This research has described a perfunctory strategy for comparative evaluation of firearm and shotshell options to optimize aerial operations for wild pigs. Utilizing such a strategy can enhance the abilities of an aerial operator and establish limitations to improve efficiencies and animal welfare outcomes.

Keywords: aerial, helicopter, removal, shotgun, shotshell, Sus scrofa, wild pig, wildlife damage management.

Introduction

Over the past decade, wild pigs (Sus scrofa) continue to increase in both number and extent across much of their native and non-native range (Snow et al. 2017; Lewis et al. 2019; Hegel et al. 2022; Markov et al. 2022; Bergqvist et al. 2024). Wild pigs disrupt agricultural and natural systems, while also posing risk of disease transmission to humans as well as domestic and native animals (Bevins et al. 2014; Snow et al. 2017; Treichler et al. 2023). With escalating wild pig numbers and range expansion, there is a need for optimized management tools. Whereas both lethal and non-lethal management strategies are needed, lethal removals minimize relocating the damage or issue elsewhere (Davis et al. 2018). As compared with other management strategies, lethal removal of wild pigs using shotguns and rifles from helicopters is an efficient and cost-effective strategy that should be considered, especially in areas experiencing significant damage, with suitable vegetation characteristics, and high densities of wild pigs (Parkes et al. 2010; Davis et al. 2018; Hampton et al. 2022; Hamnett et al. 2024; Snow et al. 2024). Aerial shooting has been used in the control of at least 33 species worldwide, and extensively in Australia and New Zealand, to control a variety of feral species (Hampton et al. 2022; Bradshaw et al. 2023; Hamnett et al. 2024). Since the late 1970s, Australians have utilized helicopters in the removal of wild pigs (Saunders and Bryant 1988). Researchers in Australia developed a multi-step comparative evaluation for establishing standard operating procedures to improve animal welfare outcomes and efficiencies for aerial shooting operations (Hampton et al. 2021, 2022).

Animal welfare is an important concern when animals are lethally removed for the purpose of wildlife damage management (Littin et al. 2004; Caudell 2013; DeNicola et al. 2019). A primary goal when selecting an appropriate firearm and ammunition combination for lethal control is maximizing lethality, given the conditions expected and minimizing the time to death and potential suffering (Leary et al. 2020; Bradshaw et al. 2023; Cox et al. 2023). The American Veterinary Medical Association accepts euthanasia techniques that result in immediate insensibility or loss of consciousness followed by cardiac or respiratory arrest, including the use of firearms (Leary et al. 2013, 2020). Time to death is directly correlated with the extent of damage to vital organs (Caudell 2013; Bradshaw et al. 2023). Instantaneous or immediate incapacitation can be achieved with wounds penetrating the central nervous system; however, rapid incapacitation can be expected with bullet impacts to the heart or major blood vessels and may be most practical with free-ranging wild animals (Maiden 2009; Caudell et al. 2012; Leary et al. 2020; Bradshaw et al. 2023). To achieve rapid incapacitation, accurate shot placement, adequate penetration, and significant tissue damage to vital organs within the target zone are essential (MacPherson 1994; Caudell 2013; DeNicola et al. 2019; Bradshaw et al. 2023; Cox et al. 2023).

Shotguns, which fire multiple projectiles called shot or pellets, are commonly used during aerial operations to remove wild pigs in the USA. Common shot sizes appropriate for medium-sized animals such as wild pigs vary from No. 4 shot (3.3 mm in diameter) to No. 00 buckshot (9.1 mm in diameter) and are spherical in shape. Shotgun shells (‘shotshells’ hereafter) loaded with No. 00 buckshot typically contain from 8 to 15 pellets arranged in various configurations, whereas smaller pellets are loaded by weight, with a common Federal (Federal Cartridge CO., Anoka, MN, USA) 70-mm, No. 4 shotshell containing 35.4 g, or 169 lead pellets. Pellets were historically made of 100% lead, but now consist of lead, steel, bismuth, tungsten, or a blend of elements designed to retain maximum energy downrange (Taylor 2002) and to be less toxic in the environment (De Francisco et al. 2003). The material density of pellets contributes to the ability to penetrate vital organs, but also effects its likelihood of ricochet, leading to safety concerns, especially important when aircraft are involved (Öğünç et al. 2020; Zohdi 2021).

Shoguns utilize a choke or choke tube (i.e. the last several centimeters of the shotgun muzzle) to constrict the pellets as they exit the muzzle and affect the distribution of pellets downrange (Arslan et al. 2011). The pattern of these pellets downrange is determined by many factors, including number and size of shot, distance to target, level of constriction produced by the choke tube, and shotshell composition (Arslan et al. 2011). Shooting large paper targets at various ranges to test different shotgun components and ammunition can help characterize the pattern of pellets and enable an aerial operator to predict downrange performance. The study of shotgun patterns is complex and extensive, oftentimes incorporating statistical models, as pellet dispersion and pattern characteristics are frequently used in investigations of shotgun-related crimes (Mattoo and Nabar 1969; Bhattacharyya and Sengupta 1989; Nag and Sinha 1992).

Although the evaluation of shotgun pellet patterns can be a ‘very complicated many-body problem with dynamical forces, constraints and boundary conditions not fully known’ p. 106 (Nag and Sinha 1992), what is occurring with pellets at the center of the pattern including dispersal and retained energy related to penetration, are the details of greatest concern when conducting aerial operations. Beyond the complex characteristics of shotgun pellet patterns associated with predictable factors such as number and weight of pellets and effects of choke tubes, human factors also contribute to the downrange outcome (Hampton et al. 2021). Although accuracy and precision of a particular firearm–ammunition combination is predictable and can be tested, once the characteristics of the firearm and individual abilities of the aerial operator are factored in, downrange performance can be affected (Hampton et al. 2021). The level of recoil associated with firing a particular shotshell from a shotgun, especially when repeatedly firing a firearm simultaneously over a short period of time has shown to have significant effects on shooting performance (Morelli et al. 2014).

The primary objective of this evaluation was to explore these details and develop a simplistic strategy for predicting lethality of several shotshells currently used in aerial operations for wild pigs by United States Department of Agriculture, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Services, Wildlife Services (USDA APHIS WS). To accomplish our objective, we developed an evaluation strategy that could guide wildlife managers through the selection of choke tubes and shotshells to optimize lethality in wild pigs during aerial operations. We defined lethality on wild pigs as a combination of two factors: first, delivery of at least one pellet into vital organs including the brain, heart, and lungs, and second, maximizing pellet penetration to damage vital organs. Capture and handling procedures were approved by the USDA APHIS WS National Wildlife Research Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (QA-3094).

Materials and methods

We conducted all shooting for data collection at a private shooting range at 1560-m elevation in Weld County, CO, USA. Shooting lanes were enclosed by 3-m-high berms on three sides, thus were protected from the wind, although we shot only when sustained winds were ≤32 km/h (Kestrel 3000 Weather Meter, Boothwyn, PA, USA). All shooters had annual firearms safety and proficiency training required by USDA APHIS WS. We used a shotgun model commonly employed in aerial operations, a 3.3-kg semi-automatic, left-handed 12-gauge shotgun, (Benelli M2; Urbino, Italy) with 66.0-cm-long barrel and outfitted with red-dot sight (Burris SpeedBead; Greeley, CO, USA). We characterized patterns and penetration of pellets delivered downrange at the three distinct distances of 27.4, 45.7, and 64.0 m, representing near, middle, and far distances typically encountered during aerial operations. We evaluated five specific shotshells including two from Federal, two from International Cartridge Corporation (ICC Ammo, Reynoldsville, PA, USA) loaded with 00 buckshot, and one shotshell from APEX (Apex Ammunition™, Columbus, MS, USA) loaded with T-shot (Table 1). We used six different choke tubes with internal bore opening diameters ranging in size from 17.65 to 18.21 mm measured with a digital caliper (01407A, Neiko Tools, Veneto, Italy), although not all choke tubes were tested with every shotshell. We shot from a sturdy firearm rest (LeadSled® 3; American Outdoor Brands, Columbia, MO, USA) atop a permanent concrete bench. To characterize specific patterns, we used paper targets (Fig. 1); made from 1.52 × 1.52-m paper (Uline, Kraft paper, Pleasant Prairie, WI, USA), with an aimpoint at the center. After shooting each target once, we recorded the date, distance of the shot, and shotshell and choke tube used. Following each shot, we photographed the target with digital camera, replaced the paper target, and proceeded until a minimum of three targets were collected for each shotshell and choke tube option at each distance.

| Shotshell | Number of pellets | Size of pellets | Pellet material | Muzzle velocity (mean ± s.d.; m/s)A | Recoil energy (Nm)B | Cost per shell (US$)C | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fed12 | 12 | 00 buckshot | Copper-plated lead | 412.8 ± 65.2 | 62.2 | 2.10 | |

| Fed9 | 9 | 00 buckshot | Tungsten–iron composite | 403.8 ± 63.9 | 28.9 | 2.23 | |

| ICC12 | 12 | 00 buckshot | Metal composite | 422.2 ± 28.0 | 50.3 | 8.19 | |

| ICC8 | 8 | 00 buckshot | Metal composite | 457.0 ± 16.0 | 24.9 | 2.50 | |

| Apex37 | 37 | T shot | Tungsten | 277.7 ± 10.1 | 37.5 | 8.50 |

Shotshell specifics, including the number, size, pellet material, velocity, recoil energy, and cost, are given. Candidate shotshells were included in an evaluation conducted at a shooting range in Colorado, USA, in 2020–2023, examining shotshells commonly used in aerial operations for removal of wild pigs (Sus scrofa).

Shotgun patterning targets. Targets made of 1.52-m × 1.52-m paper with a centrally located aimpoint used in an evaluation conducted at a shooting range in Colorado, USA, in 2020–2023, comparing shotshells commonly used in aerial operations for removal of wild pigs (Sus scrofa). Photograph by Michael Lavelle.

Manual pattern evaluation

We developed a technique for manually evaluating each target. All targets were taken to a large desktop where basic measuring tools including tape measure and drafting triangle were used to delineate pattern characteristics. To calculate the pattern area, we oriented the target as secured when initially shot and enclosed the group of pellet holes in the smallest possible rectangle with the sides aligned parallel with the sides of the target (Fig. 2a). Additionally, height always represented the vertical axis and top/bottom represented the width, or horizontal axis, of the pattern respectively. We recorded the dimensions and calculated the area of the rectangle. We also located the geometric center of the pattern by drawing diagonal lines connecting opposing corners and marking the intersection.

Characterizing and evaluating lethality of shotshell patterns. Images of a pellet pattern on a paper target from a 12-gauge shotshell loaded with ICC 00 buckshot shot at 27.4 m in an evaluation of shotshells commonly used in aerial operations for removal of wild pigs (Sus scrofa) conducted at a shooting range in Colorado, USA, in 2020–2023. (a) Identifying the geometric center and measuring the pattern (height and width) of the pellet holes. (b) Customized plexiglass template overlaid on the target with the ‘x’ or alignment point of the template positioned directly over the geometric center of the pellet pattern. Pellets were characterized as vital, when ≥1 pellet landed in the vital zone of head and chest, non-vital, when landing within the outline of the pig, but outside of vital organs of head and chest, and complete misses, when none fell within the outline of the pig. Photograph by Michael Lavelle.

We created a customized plexiglass wild pig template to classify the status of each pellet hitting each target to establish a measure of lethality for each shot (Fig. 2b). Specifically, we drew an outline of the dorsal aspect of a typical 34-kg wild pig including its vital zone (i.e. brain and chest cavity) and overlaid this template directly onto each target. To avoid complications of evaluating multiple vital zones and widely ranging variability in sizes of targeted wild pigs, we defined the midpoint between the brain and chest cavity as the alignment point for consistent placement of the template on all patterns. This focal point was selected only for comparative evaluation, realizing that specific agencies and organizations may have requirements and protocols that specify actual aimpoints for shooters to target during aerial operations (Sharp 2012). We overlaid the alignment point of the template and the geometric center of the pattern with the wild pig outline oriented lengthwise from top to bottom. We assumed that the point of aim of the shooter and point of impact of the shotgun were aligned, as should be the case for aerial operators (i.e. operators have patterned their shotguns so that point of aim is the center of their pattern). We classified and quantified the number of pellets within the outlined vital zone as ‘vital hits’. Those that fell outside the vital zone, but within the outline of the wild pig were classified as ‘non-vital’ hits, and ‘misses’ were those outside of the outline of the pig. Our goal of this manual pattern evaluation was to mimic a real-world situation with shooting wild pigs from above to determine which shotshell–choke tube combination would have the greatest probability of placing at least one pellet in the vital zone at the three distances mentioned above.

Penetration evaluation

We also developed a layered target design that would enable us to establish a relative level of penetration for comparing among shotshells and at increasing distances within shotshell types. We constructed targets of 12 layers of 41-cm by 41-cm square, 3.2-mm-thick medium-density fiberboard (MDF) paneling secured together with wood screws at all four corners. We fired consecutive shots into each target at our three distances until ≥12 pellets landed on the target. Then, we disassembled the targets and recorded the number of pellets that terminated at each layer. Occasionally, a pellet passed through all layers of a target, therefore we recorded one layer beyond the last layer penetrated.

Ballistics evaluation

To further the understanding of the relative level of penetration demonstrated by layered targets, we calculated the energy of pellets at both the muzzle and downrange when fired from shotshells at our three distances by using shotshell ballistics software (KPY Shotshell Ballistics, KPY Enterprises, Placerville, CA, USA). Within the software, the user enters a series of inputs specific to the shotshell load, distances, and environmental conditions and the software calculates a variety of energy-related outputs. Using the ballistics software, we also calculated recoil energy (Nm) associated with firing each shotshell on the basis of load details of each shotshell and weight of the shotgun.

Statistical analysis

We initially examined all choke tube diameter and shotshell combinations used to find any that had a lower probability of a vital hit from our wild pig template above, with the goal of excluding those combinations from further analysis. Specifically, for each shotshell type, we used a binomial generalized linear model in Program R (ver. 4.2.0; R Core Team 2021) to examine the model: probability of vital hit = distance + choke tube diameter. We examined the parameter estimates and 95% confidence intervals for a lack of overlap of zero, to indicate biologically and statistically significant findings. Some shotshell manufacturers recommended specific choke tube sizes; thus, we did not test all combinations. For the three shotshells that we examined multiple choke tube diameters, we evaluated how the inside diameter influenced the density of pellets on the target. We calculated the density by dividing by the number of pellets by the area of the pattern (i.e. maximum width × maximum length). We used linear models to examine how choke tube diameter influenced the densities of pellets by using the model: pellet density ~ choke tube diameter, for each shotshell tested.

We examined how shotshell type, distance, and choke tube influenced the probability of a hit in the vital zone with wild pig template. Specifically, we conducted a model selection procedure by using similar binomial generalized linear models as mentioned above and ranked the models by using Akaike information criterion (AIC; Burnham and Anderson 2002) with the MuMIn package in Program R (Barton and Barton 2015). We examined all combinations of the global model: vital hit = shotshell + distance + choke tube. We considered any competing top models that were ≤2.0 ΔAIC from the top-ranked model. We examined the parameter estimates and 95% CIs of the top-ranked models as well as the relative importance of each covariate.

We also evaluated how shotshell type, distance, and choke tube influenced the probability of non-vital hits, and complete misses by using the same analysis technique as mentioned above. Specifically, we considered a non-vital hit as any shot that resulted in zero pellets in the vital zone, and one or more pellets in the non-vital zone. Similarly, a miss was considered as any pattern with zero hits in the vital or non-vital zone. This was a conservative estimation of non-vital hits and misses, considering that in real-world situations there may be the opportunity for follow-up shots.

To compare depth of pellet penetration, we examined how many layers of MDF were penetrated by one or more pellets for each shotshell from the three distances. We compared depth of penetration by using a Poisson generalized linear model (count of layers penetrated = shotshell + distance) as described above.

Results

Overall, we collected data from 238 paper targets, with an average of 6.63 (range = 3–20, s.d. = 3.13) targets per shotshell–distance–choke tube combination. An overall average proportion of pellets delivered downrange and landing on the target and included in analyses was 0.94 (range = 0.79–1.00, s.d. = 0.07). The average proportion of pellets landing on the target dropped from 0.99 (range = 0.96–1.00, s.d. = 0.02) at 24.7 m, to 0.96 (range = 0.91–0.97, s.d. = 0.03) at 45.7 m, to 0.86 (range = 0.79–0.95, s.d. = 0.07) at 64.0 m.

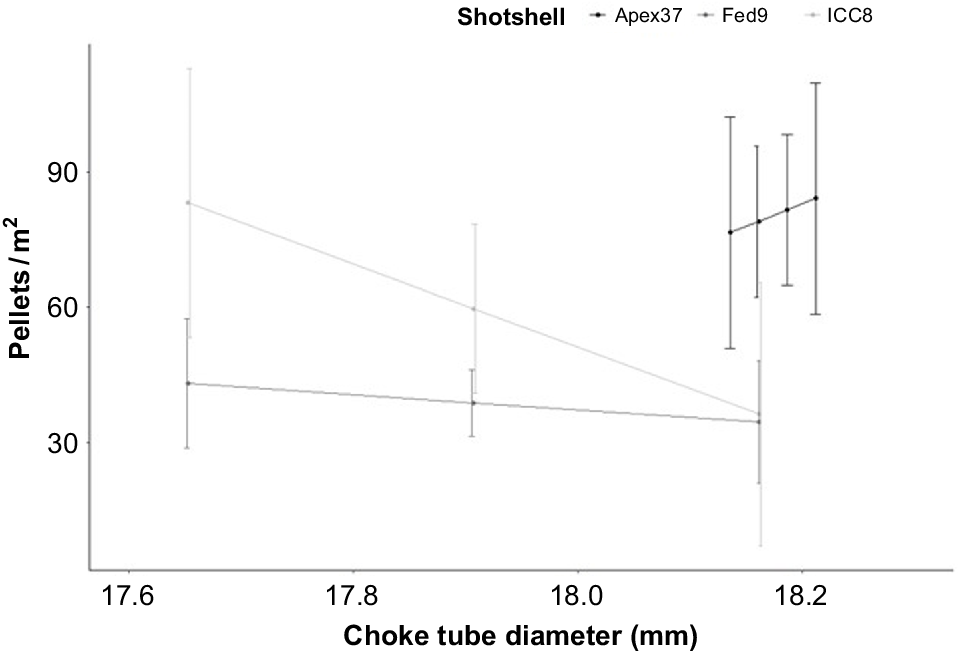

We found no differences in the density of pellets within a pattern with various choke tube diameters for Apex37 (β = 2530, 95% CI = −11,161–16,222) or Fed9 (β = 432, 95% CI = −1619–755; Fig. 3). The density of pellets decreased with an increasing diameter of choke tubes for ICC8 (β = −2343, 95% CI = −4360 – −56). Model predictions indicated an approximate 50% decrease in density for each approximately 0.5-mm increase in choke diameter for ICC8.

Pellet density by choke tube. Predicted pellet density (and 95% CIs) by choke tube diameters (17.5–18.3 mm) tested for three types of shotshells commonly used in aerial operations for removal of wild pigs (Sus scrofa), including Apex with 37 T-shot pellets and Federal and ICC with nine and eight 00 buckshot pellets respectively. We did not include Federal and ICC 12 00 buckshot in this figure because we evaluated them only with a single choke tube size.

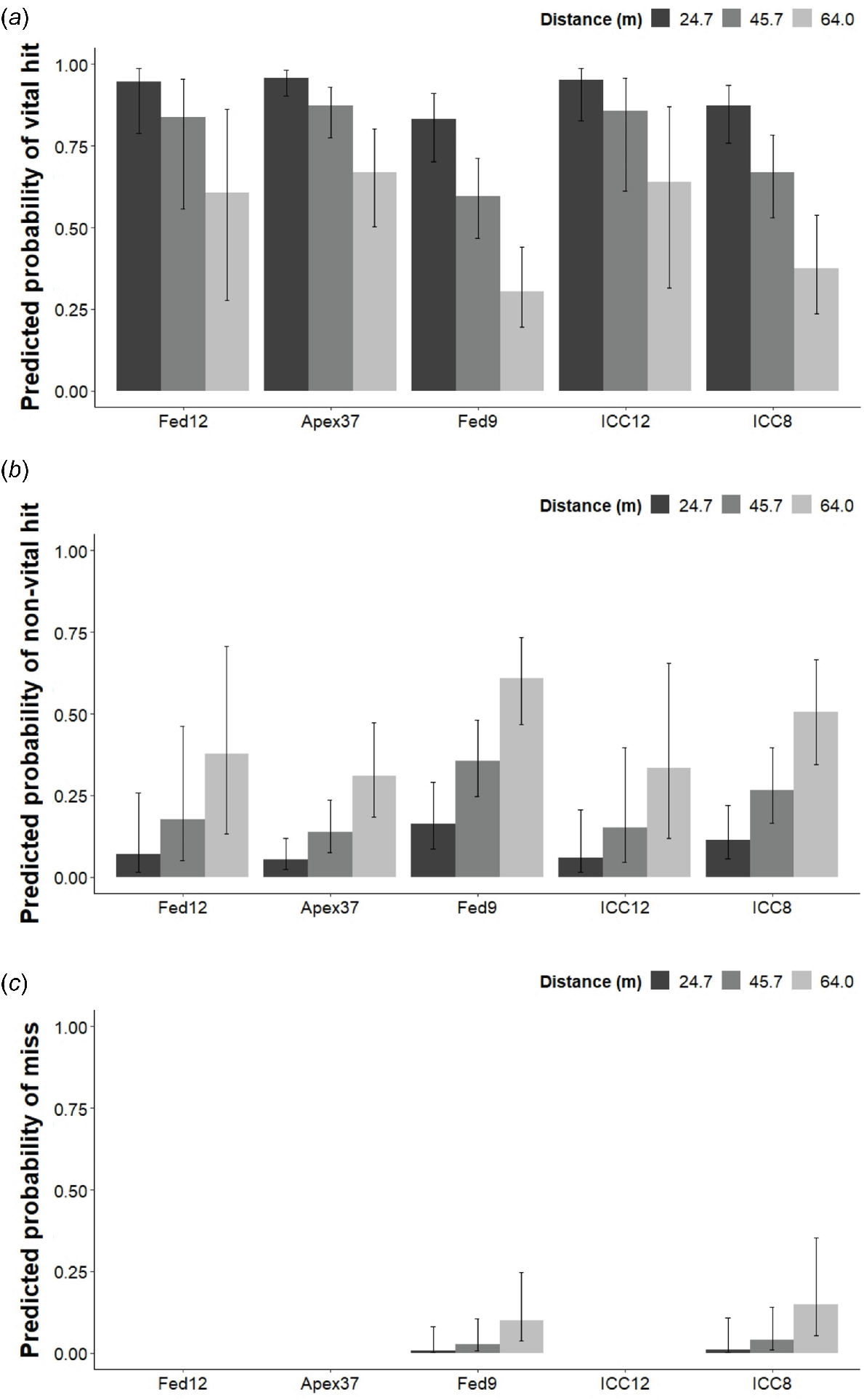

All shotshells performed well with a high mean probability of a vital hit (>0.75) at the closest 24.7-m distance and those with ≥12 pellets performed well (>0.75) at 45.7 m (Fig. 4a). The model selection procedure for evaluating the probability of a vital hit indicated there were two competing top models (Table 2). The relative importance of the variables suggested that distance to the target (1.00) and shotshell type (0.98) was greatly important for determining the probability of a vital hit. Choke tube diameter (0.30) was less important. Parameter estimates indicated that the probability of a vital hit declined significantly with a greater distance (Table 3). Model predictions indicated that the probability of a vital hit declined an average of 10% for each additional 10 m of distance. Shotshell type and choke tube diameter did not significantly influence the probability of a vital hit.

Probability of a vital hit. (a) The predicted probability of a hit in the vital zone (vital organs of head and chest) of wild pigs (Sus scrofa) with five different shotshells (Federal and ICC 00 buckshot and Apex T-shot) used for aerial removals at increasing distances (24.7, 45.7, and 64.0 m). (b) Predicted probability of a non-vital hit (within the body, but outside of vital organs of head and chest) on wild pigs (Sus scrofa) with five different shotshells (Federal and ICC 00 buckshot and Apex T-shot) used for aerial removals at increasing distances (24.7, 45.7, and 64.0 m). (c) The predicted probability of a completely missed shot on wild pigs (Sus scrofa) with five different shotshells used for aerial removals (Federal and ICC 00 buckshot and Apex T-shot) at increasing distances (24.7, 45.7, and 64.0 m). Error bars are the 95% prediction intervals. Hits were characterized by using a customized plexiglass template overlaid directly on paper targets shot once by candidate shotshells in an evaluation conducted at a shooting range in Colorado, USA, in 2020–2023.

| Model | Number of parameters | AICc | ΔAICc | Model weight | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probability of vital hit = | |||||

| Distance + Shotshell | 6 | 251.8 | 0.0 | 0.69 | |

| Distance + Shotshell + Choke diameter | 7 | 253.6 | 1.7 | 0.30 | |

| Distance + Choke diameter | 3 | 260.9 | 9.0 | 0.01 | |

| Distance | 2 | 261.2 | 9.4 | 0.01 | |

| Shotshell | 5 | 288.3 | 36.4 | 0.00 | |

| Shotshell + Choke diameter | 6 | 289.8 | 38.0 | 0.00 | |

| Choke diameter | 2 | 298.5 | 46.6 | 0.00 | |

| Probability of non-vital hit = | |||||

| Distance + Shotshell | 6 | 254.6 | 0.0 | 0.53 | |

| Distance + Shotshell + Choke diameter | 7 | 256.6 | 2.1 | 0.19 | |

| Distance + Choke diameter | 3 | 257.2 | 2.6 | 0.14 | |

| Distance | 2 | 257.2 | 2.6 | 0.14 | |

| Shotshell | 5 | 280.6 | 26.0 | 0.00 | |

| Shotshell + Choke diameter | 6 | 282.6 | 28.0 | 0.00 | |

| Choke diameter | 2 | 285.0 | 30.5 | 0.00 | |

| Probability of miss = | |||||

| Distance + Shotshell | 6 | 66.5 | 0.0 | 0.38 | |

| Distance | 2 | 67.2 | 0.8 | 0.26 | |

| Distance + Shotshell + Choke diameter | 7 | 67.9 | 1.4 | 0.19 | |

| Distance + Choke diameter | 3 | 69.2 | 2.7 | 0.10 | |

| Shotshell | 5 | 71.0 | 4.5 | 0.04 | |

| Shotshell + Choke diameter | 6 | 72.3 | 5.8 | 0.02 | |

| Choke diameter | 2 | 74.0 | 7.5 | 0.01 | |

Results from all combinations of models evaluating the effect of distance (24.7, 45.7, and 64.0 m), shotshell type (Federal 9 and 12 00 buckshot, and ICC 8 and 12 00 buckshot, and Apex T-shot), and choke tube diameter (17.5–18.3 mm) on the probability of a vital hit, a non-vital hit, or a miss. Hits were characterized by using a custom plexiglass template overlaid directly on a paper target shot with a candidate shotshell in an evaluation conducted at a shooting range in Colorado, USA in 2020–2023. Hits were characterized as vital, when ≥1 pellet landed in the vital zone of head and chest, non-vital, when landing within the outline of the pig, but outside of vital organs of head and chest, and complete misses, when none fell within the outline of the pig.

| Covariate | Probability of a vital hit | Probability of a non-vital hit | Probability of a miss | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95% CI | 95% CI | 95% CI | ||||||||

| β | − | + | β | − | + | β | − | + | ||

| Distance | −0.06 | −0.08 | −0.04 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.16 | |

| Apex37 | 0.27 | −1.41 | 1.75 | −0.30 | −1.76 | 1.37 | −0.18 | −20,101.29 | 454.89 | |

| Fed9 | −1.27 | −2.90 | 0.14 | 0.95 | −0.44 | 2.57 | 17.65 | −412.54 | NAb | |

| ICC12 | 0.13 | −1.84 | 2.11 | −0.18 | −2.13 | 1.76 | 0.45 | −267.00 | 267.90 | |

| ICC8 | −0.95 | −2.61 | 0.50 | 0.53 | −0.90 | 2.18 | 18.11 | −412.08 | NAb | |

| Choke tube diameter | −17.60 | −71.69 | 35.72 | NAA | NAA | NAA | 46.76 | −57.29 | 160.68 | |

Estimated model parameters with 95% CIs from top models for evaluating the influences of distance (24.7, 45.7, and 64.0 m), shotshell type (Federal and ICC 00 buckshot and Apex T-shot), and choke tube diameter (17.5–18.3 mm) on the probability of a vital hit, a non-vital hit, and a miss on wild pigs (Sus scrofa) in an evaluation conducted at a shooting range in Colorado, USA, in 2020–2023. Hits were characterized by using a custom plexiglass template overlaid directly on a paper target shot with a candidate shotshell in an evaluation conducted in Colorado, USA, in 2020–2023. Pellets were characterized as vital, when ≥1 pellet landed in the vital zone of head and chest, non-vital, when landing within the outline of the pig, but outside of vital organs of head and chest, and complete misses, when none fell within the outline of the pig. These confidence intervals could not be calculated because of limited sample sizes in misses for these shotshells.

The model selection procedure for evaluating the probability of a non-vital hit indicated one top model, including distance and shotshell (Table 2). The relative importance suggested that distance was highly important (1.00), followed by shotshell (0.72), and choke tube diameter (0.33). The probability of a non-vital hit increased significantly with an increasing distance (Fig. 4b, Table 3). Model predictions indicated that the probability of a non-vital hit increased 8% for each additional 10-m of distance. Shotshell type did not significantly influence the probability of a non-vital hit.

The model selection procedure for evaluating the probability of a complete miss indicated three competing top models (Table 2). The relative importance suggested that distance was most important (0.93), followed by shotshell (0.62), and choke tube diameter (0.32). Complete misses did not occur for Fed12, ICC12, and Apex37; therefore, model results for these shotshell types could not be generated. However, we found that the probability of a miss increased significantly with an increasing distance. Model predictions indicated that the probability of a miss for Fed9 and ICC8 increased 3% for each additional 10 m of distance (Fig. 4c). Choke tube diameter did not influence the probability of a miss.

The overall average depth of penetration ranged from 3.5 to 9.5 layers of MDF (Fig. 5). We found that the ICC8 and ICC12 shotshells with the highest measured pellet velocities of 457.05 m/s and 422.22 m/s respectively (Table 1) had the greatest depth of penetration at 24.7-m and 45.7-m distances. The Fed9 (β = 0.11; 95% CI = 0.02–0.22), ICC12 (β = 0.42; 95% CI = 0.31–0.53), and ICC8 shotshells (β = 0.27; 95% CI = 0.16–0.37) all had deeper penetration than did Fed12. Apex37 had a similar penetration to that of the Fed12 (β = −0.08; 95% CI = −0.19–0.03). For all shotshells, penetration declined substantially with greater distances (β = −0.02; 95% CI = −0.021 to −0.017). Penetration from the Apex37 shotshell was least affected by distance, whereas Fed12 was most affected.

Comparative penetration by shotshell. Average layers of medium-density fiberboard penetrated per shot fired from five shotshells (Federal and ICC 00 buckshot and Apex T-shot) at three distances (24.7, 45.7, and 64.0 m) in an evaluation conducted at a shooting range in Colorado, USA, in 2020–2023, examining shotshells commonly used in aerial operations for removal of wild pigs (Sus scrofa). Error bars are the 95% prediction intervals.

The shotshells we evaluated varied widely in their calculated levels of recoil from 24.9 to 62.2 Nm. The ICC8 shotshell, firing the fewest number of pellets (8) had the lowest calculated recoil at 24.9 Nm (Table 1). Conversely, the Fed12 shotshell with the second-heaviest overall load of shot had 2.5× greater calculated recoil (>62 Nm) than did the lowest ICC8. Costs associated with the shotshells we used, or those very similar, ranged from US$2.10 to US$8.50 per shotshell (Table 1).

Discussion

Overall, our results emphasize the importance of distance to the target when shooting a shotgun, and especially when considering the number of pellets. As shot distances increase, dispersion of the pellets and gaps among pellets also increase (Bhattacharyya and Sengupta 1989; Nag and Sinha 1992). When extending the shot distance from 45.7 to 64.0 m, the probability of both vital and non-vital hits approached 0.50 for shotshells with ≤12 pellets, suggesting shots taken beyond 45.7 m should be avoided. In situations where environmental conditions such as topography and canopy height reduce the potential for closer shots (e.g. w/n 45.7 m), the use of rifles could be considered to extend the lethal range.

Our model results indicated that shotshell type was the second-most influential variable in the predicted probability of complete misses, and the number of pellets was the primary difference among shotshells. In general, a shotgun typically delivers an array of pellets downrange, numbering 8–37 in our case, unlike a rifle projecting a single bullet. The location of where that array of pellets hits the target is dependent on the gun and the shooter, although the arrangement of pellets will vary. Although we based our evaluation on placing at least one pellet in the vital zone, maximizing the number of pellets landing in the vital zone is the desired goal. As the distance to the target increases, the increased dispersion of pellets results in a decreased density of pellets per pattern area and increases the potential for complete misses. Shotshells delivering ≥12 pellets always had ≥1 pellet hitting within the outline of the pig (i.e. vital and non-vital hits combined), whereas shotshells delivering fewer pellets (i.e. <12) had an increased probability of hitting only outside the outline (i.e. misses), especially beyond the 24.7-m distance. This suggests that within reason (i.e. while maintaining sufficient energy to remain lethal), selecting shotshells with higher numbers of pellets will improve the probability of a vital hit, and thus more efficient wild pig removals. Seasonality needs to be factored into firearm and ammunition selection, because the prominent size class of target animals will vary, such as after farrowing when there will be a higher proportion of piglets on the landscape. With increases in smaller targets on the landscape, the use of a shotgun firing shotshells with higher numbers of smaller shot, such as the Apex t-shot shotshells we evaluated, may be most suitable.

As the probability of a vital hit decreases with an increased distance, the probability of non-vital hits increases, resulting in increased potential for adverse animal welfare outcomes. Although vital hits are the overall goal during lethal removals, non-vital hits may momentarily immobilize a wild pig and increase the potential for vital follow-up shots over complete misses. However, the need for follow-up shots increases the time in hazardous low-level flight, as well as increasing the cost of ammunition; thus, making every attempt to insure that the first shot is a vital hit is needed. Complete misses increase the costs of aerial operations and increase risks associated with pellet ricochet and affect overall safety. Missed shots also have the potential to disperse wild pigs, which can increase risks of spreading disease in a disease outbreak situation and should be minimized. Complete misses also have the potential to educate wild pigs on risks associated with the sights and sounds of helicopters and aerial operations, with the possibility of developing survival strategies that reduce their potential for removal via aerial operations (Campbell et al. 2010).

Our penetration evaluation with layered targets provided a measure of level of penetration useful for relative comparisons among shotshells at varying distances to the target (Fig. 5). Ballistic gel is commonly used to demonstrate the effects of bullets on human tissues, although we sought to simply evaluate the comparative level of penetration among shotshells (Filipchuk and Gurov 2015). Although 00 buckshot pellets had greater penetration than did the Apex37 T shot at 24.7 m, we found that penetration declined as distance increased; however, penetration by the Apex37 pellets was least affected by increased distance. At 64.0 m, penetration by ICC8 exceeded all others and penetration by Apex37 was comparable to that by ICC12, Fed9, and Fed12. All shotshells in our evaluation had pellets penetrating at least three layers of MDF board at 64.0 m; however, translating that directly to lethality in wild pigs is not possible without additional testing. Further, as penetration declines with distance, impacts that would likely have been vital impacts at 24.7 m, may result in non-vital impacts owing to decreased penetration at longer distances, emphasizing the importance of limiting shots to distances shown to achieve lethal impacts.

A wide array of choke tubes is commercially available, all with the goal of manipulating the pattern size downrange by limiting dispersal of pellets to align with goals of specific shooting scenarios (Arslan et al. 2011). The density of pellets is typically directly affected by the internal diameter of the choke and distance of the shot, thus also the ability to hit a target (Arslan et al. 2011). As the density of pellets decreases, so does the probability of hitting a small target area, such as the vital zone on an average wild pig; however, our results demonstrated that the diameter of the choke tube had a minimal effect on the probability of a vital hit compared with other variables (Table 3). Selecting a choke tube with too much constriction (smaller opening diameter) can minimize the spread of pellets at closer ranges, thus decreasing the margin of error in aiming effectively (Arslan et al. 2011). Conversely, a choke with too little constriction can result in widely spaced pellets, especially at longer distances; thus, the spread of pellets can be so great that gaps among pellets minimize the potential for hitting a target (Arslan et al. 2011).

During aerial operations in areas with high densities of wild pigs, it is common for aerial operators to fire thousands of shotgun rounds in a day, which can be mentally and physically demanding, particularly because of repetitive intense impacts of recoil. The weight of the firearm, weight of pellets in a shotshell, and the amount of powder used to propel the shot, directly affect the amount of recoil. Newton’s third law of physics states that for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction, and it applies directly to shooting a firearm (Hall 2008). This opposite reaction is experienced when shooting a firearm and is termed recoil and is broken down into both physical recoil and perceived recoil (Morelli et al. 2014). Physical recoil can be measured or calculated and consists of the following two components; first, the acceleration of the load of pellets within the barrel; and second, the acceleration of gases also within the barrel resulting from the combustion of the powder in the shotshell (Hall 2008). Conversely, the perceived recoil is a subjective measure of impact intensity felt and reacted to by a shooter (Morelli et al. 2014). Previous studies have demonstrated that even moderate levels of recoil (>33.9 Nm) can affect accuracy, hamper the ability to fire multiple rounds, and even cause bruising (Harper et al. 1996). Calculated levels of recoil varied considerably among our shotshells, and some greatly exceeded recoil deemed tolerable in previous studies (Harper et al. 1996; Morelli et al. 2014). The felt recoil or recoil energy associated with firing a 12-ga shotgun can be substantial, ranging from 24.9 to 62.2 Nm with the shotshells we evaluated. This recoil may be tolerable to a degree; yet, an aerial operator may develop a ‘flinch’, or movement of the firearm in anticipation of recoil, which will invariably affect the accuracy of subsequent shots (Harper et al. 1996; Taylor 2002; Morelli et al. 2014). Military study subjects in a research evaluation averaged a maximum tolerable number of 17.3 shots with a recoil of 33.9 Nm and 6.7 shots under greater recoil (58.3 Nm) (Harper et al. 1996), being considerably fewer than we calculated for our Fed12 shotshell with a calculated recoil of 62.2 NM. Although all shotshells in this evaluation were capable of repeatedly delivering vital hits, consistent accuracy is dependent on the individual aerial operator and their ability to tolerate the associated recoil. We recommend assessing individual-based tolerance to recoil to establish a balance between shotshell selection to maximize the number of deeply penetrating pellets required to achieve lethal impacts, and maintaining a sustainable and effective level of operation. Fortunately, the tolerable level of recoil is subjective, and can be mitigated with specialized recoil pads that can be installed on firearms and shooting apparel.

While maximizing lethality is an important goal in improving aerial operations, it must be undertaken concurrently with attempts to improve animal welfare outcomes (Hampton et al. 2022). As such, Australian researchers devised a team-based approach adding a thermal-viewer-equipped observer to the routine shooter and pilot team (Cox et al. 2023). Another Australian research group further increased efficiency and animal welfare outcomes by utilizing two shooters simultaneously, one with shotgun and another with rifle, along with a thermal-viewer-equipped observer and the pilot (Bradshaw et al. 2023). Incorporating an observer with thermal-imaging optics improved initial animal detection and also facilitated follow-up actions on animals not immediately incapacitated (Bradshaw et al. 2023; Cox et al. 2023).

To establish limitations, it is important to consider and evaluate the extremes, such as maximum effective shot distance. These limitations can then be used to develop improved strategies to advance safety, efficiency, and animal welfare outcomes. Aerial shooting is a management strategy used for a variety of mammalian species that has been commonplace in Australia for decades. Standard operating procedures (SOPs) detail established protocols that guide field operations on the species being targeted (i.e. Sharp and Saunders 2004; Sharp 2012). Government Agencies, and private and commercial operators are required to follow established requirements. Established Australian SOPs designate that only chest (heart-lung), or head (brain) shots be taken on target animals to ensure that instant insensibility is achieved. At a minimum, a follow-up shot to the heart–lung zone is required. Shotguns are used for small to medium sized animals to a maximum distance of 20 m, although the use of 0.308 caliber semi-automatic rifles is more common and limited to a maximum distance of 70 m (Sharp 2012). Target and shot placement guidelines specify distinct locations where a single bullet is intended to affect the target animal, including the heart and brain.

In the USA, shotguns are commonly used with the goal to center the array of pellets so that the likelihood of hitting the brain and heart is maximized. Thus, for our evaluation, we centered the wild pig template between the brain and chest cavity. Only at reduced distances and with greater choke tube constrictions (i.e. 30 m with full choke) will the array of pellets be focused near the geometric center of the pattern or the distinct aimpoint. There are numerous options for optics that allow an operator to align the point of aim with the point of impact of a shotgun to improve consistent shot placement. Although we used a red-dot sight, other options such as holographic sights and traditional scopes are available and should be considered depending on situation-specific needs and personal preference. We selected a red-dot sight to provide a quick-to-identify, adjustable illuminated aimpoint with minimal obstruction of the sight window.

Our evaluation was an initial step towards exploring effects of various choke tubes, shotshells, and distances to identify limitations and establish more effective strategies to produce the best animal welfare outcomes and maximize efficiency to maintain safe aerial operations. Our evaluation was limited to predicting the level of lethality, and did not evaluate pattern characteristics or levels of pellet penetration on live animals shot from moving aircraft. True vital and non-vital hits on wild pigs are dependent on many variables such as specific tissues affected, distance to target, and angle of impact. We recommend further evaluation using live wild pigs with manipulation of shotshell characteristics such as propellent load, pellet number, size, and material, as well as shot placement, shot distance, and size of wild pigs.

Conclusions

Aerial operations for removing invasive species such as deer and wild pigs are effective (Bradshaw et al. 2023; Snow et al. 2024) and strategies such as we presented herein can optimize effectiveness and efficiency. Fortunately, the two most influential variables on effectiveness we identified, distance to the target and shotshell selection, are also within the control of an aerial operator. As such, an aerial operator should hone their abilities in estimating distance to the target to limit their shot distances within their pre-determined effective range by routinely using a range finder. Additionally, shotshell selection should be made with the goal of delivering the maximum number of deeply penetrating pellets downrange to cause adequate tissue damage to ensure rapid incapacitation of the animals being targeted. By understanding limitations such as effective distance of firearms and shotshells, aerial operations can be an efficient tool contributing to effective control of wild pig populations, while maintaining high animal welfare outcomes.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this publication are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent any official USDA or US Government determination or policy. Mention of companies or commercial products does not imply recommendation or endorsement by USDA over others not mentioned. USDA neither guarantees nor warrants the standard of any product mentioned. Product names are mentioned solely to report factually on available data and to provide specific information.

Data availability

The data that support this study will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Declaration of funding

This research was supported by the intramural research program of the US Department of Agriculture, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, Wildlife Services, National Wildlife Research Center and the APHIS National Feral Swine Damage Management Program.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the USDA-APHIS-WS-NWRC for logistical and financial support. Mention of commercial products or companies does not represent an endorsement by the US Government. We thank P. Hall, J. C. Griffin, J. Larson, T. McLeary, and N. Rhoades for providing input on methods for improving our evaluation. We also thank K. Kohen, J. Halseth, A. Messer, M. Glow, and N. Marbury for helping collect and collate data throughout the study.

References

Arslan MM, Kar H, Üner B, Çetin G (2011) Firing distance estimates with pellet dispersion from shotgun with various chokes: an experimental, comparative study. Journal of Forensic Science 56, 988-992.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Barton K, Barton MK (2015) Package ‘mumin’. Version 1(18), 439.

| Google Scholar |

Bergqvist G, Kindberg J, Elmhagen B (2024) From virtually extinct to superabundant in 35 years: establishment, population growth and shifts in management focus of the Swedish wild boar (Sus scrofa) population. BMC Zoology 9, 14.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Bevins SN, Pedersen K, Lutman MW, Gidlewski T, Deliberto TJ (2014) Consequences associated with the recent range expansion of nonnative feral swine. BioScience 64, 291-299.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Bhattacharyya C, Sengupta PK (1989) Shotgun pellet dispersion in a Maxwellian model. Forensic Science International 41, 205-217.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Bradshaw CJA, Doube A, Scanlon A, Page B, Tarran M, Fielder K, Andrews L, Bourne S, Stevens M, Schulz P, Kloeden T, Drewer S, Matthews R, Findlay C, White W, Leehane C, Conibear B, Doube J, Rowley T (2023) Aerial culling invasive alien deer with shotguns improves efficiency and welfare outcomes. NeoBiota 83, 109-129.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Campbell TA, Long DB, Leland BR (2010) Feral swine behavior relative to aerial gunning in Southern Texas. The Journal of Wildlife Management 74, 337-341.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Caudell JN (2013) Review of wound ballistic research and its applicability to wildlife management. Wildlife Society Bulletin 37, 824-831.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Caudell JN, Stopak SR, Wolf PC (2012) Lead-free, high-powered rifle bullets and their applicability in wildlife management. Human-Wildlife Interactions 6, 12.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Cox TE, Paine D, O’Dwyer-Hall E, Matthews R, Blumson T, Florance B, Fielder K, Tarran M, Korcz M, Wiebkin A, Hamnett PW, Bradshaw CJA, Page B (2023) Thermal aerial culling for the control of vertebrate pest populations. Scientific Reports 13, 10063.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Davis AJ, Leland B, Bodenchuk M, VerCauteren KC, Pepin KM (2018) Costs and effectiveness of damage management of an overabundant species (Sus scrofa) using aerial gunning. Wildlife Research 45, 696-705.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

De Francisco N, Ruiz Troya JD, Agüera EI (2003) Lead and lead toxicity in domestic and free living birds. Avian Pathology 32, 3-13.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

DeNicola AJ, Miller DS, DeNicola VL, Meyer RE, Gambino JM (2019) Assessment of humaneness using gunshot targeting the brain and cervical spine for cervid depopulation under field conditions. PLoS ONE 14, e0213200.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Filipchuk OV, Gurov OM (2015) Peculiarities of applying ballistic gel as a simulator of human biological tissues. Theory and Practice of Forensic Science and Criminalistics 15, 367-373.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hall MJ (2008) Measuring felt recoil of sporting arms. International Journal of Impact Engineering 35, 540-548.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hamnett PW, Saltré F, Page B, Tarran M, Korcz M, Fielder K, Andrews L, Bradshaw CJA (2024) Stochastic population models to identify optimal and cost-effective harvest strategies for feral pig eradication. Ecosphere 15, e70082.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hampton JO, Arnemo JM, Barnsley R, Cattet M, Daoust P-Y, DeNicola AJ, Eccles G, Fletcher D, Hinds LA, Hunt R, Portas T, Stokke S, Warburton B, Wimpenny C (2021) Animal welfare testing for shooting and darting free-ranging wildlife: a review and recommendations. Wildlife Research 48, 577-589.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hampton JO, Bengsen AJ, Pople A, Brennan M, Leeson M, Forsyth DM (2022) Animal welfare outcomes of helicopter-based shooting of deer in Australia. Wildlife Research 49, 264-273.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hegel CGZ, Faria GMM, Ribeiro B, Salvador CH, Rosa C, Pedrosa F, Batista G, Sales LP, Wallau M, Fornel R, Aguiar LMS (2022) Invasion and spatial distribution of wild pigs (Sus scrofa L.) in Brazil. Biological Invasions 24, 3681-3692.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Lewis JS, Corn JL, Mayer JJ, Jordan TR, Farnsworth ML, Burdett CL, VerCauteren KC, Sweeney SJ, Miller RS (2019) Historical, current, and potential population size estimates of invasive wild pigs (Sus scrofa) in the United States. Biological Invasions 21, 2373-2384.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Littin KE, Mellor DJ, Warburton B, Eason CT (2004) Animal welfare and ethical issues relevant to the humane control of vertebrate pests. New Zealand Veterinary Journal 52, 1-10.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Maiden N (2009) Historical overview of wound ballistics research. Forensic Science, Medicine, and Pathology 5, 85-89.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Markov N, Economov A, Hjeljord O, Rolandsen CM, Bergqvist G, Danilov P, Dolinin V, Kambalin V, Kondratov A, Krasnoshapka N, Kunnasranta M, Mamontov V, Panchenko D, Senchik A (2022) The wild boar Sus scrofa in northern Eurasia: a review of range expansion history, current distribution, factors affecting the northern distributional limit, and management strategies. Mammal Review 52, 519-537.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Mattoo BN, Nabar BS (1969) Evaluation of effective shot dispersion in buckshot patterns. Journal of Forensic Sciences 14, 263-269.

| Google Scholar | PubMed |

Morelli F, Neugebauer JM, LaFiandra ME, Burcham P, Gordon CT (2014) Recoil measurement, mitigation techniques, and effects on small arms weapon design and marksmanship performance. IEEE Transactions on Human-Machine Systems 44, 422-428.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Nag NK, Sinha P (1992) An investigation into pellet dispersion ballistics. Forensic Science International 55, 105-130.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Öğünç Gİ, Özer MT, Uzar Aİ, Eryılmaz M, Mercan M (2020) The analysis and shooting reconstruction of the ricocheted shotgun pellet wounds. Turkish Journal of Trauma and Emergency Surgery/Ulusal Travma ve Acil Cerrahi Dergisi 26, 911-919.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Parkes JP, Ramsey DSL, Macdonald N, Walker K, McKnight S, Cohen BS, Morrison SA (2010) Rapid eradication of feral pigs (Sus scrofa) from Santa Cruz Island, California. Biological Conservation 143, 634-641.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

R Core Team (2021) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. Available at https://www.R-project.org/

Saunders G, Bryant H (1988) The evaluation of a feral pig eradication program during a simulated exotic disease outbreak. Wildlife Research 15, 73-81.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Sharp T (2012) NATSOP-PIG002 national standard operating procedure: aerial shooting of feral pigs. PestSmart website. Available at https://pestsmart.org.au/toolkit-resource/aerial-shooting-of-feral-pigs/ [accessed 7 January 2025]

Snow NP, Jarzyna MA, VerCauteren KC (2017) Interpreting and predicting the spread of invasive wild pigs. Journal of Applied Ecology 54, 2022-2032.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Snow NP, Smith B, Lavelle MJ, Glow MP, Chalkowski K, Leland BR, Sherburne S, Fischer JW, Kohen KJ, Cook SM, Smith H, VerCauteren KC, Miller RS, Pepin KM (2024) Comparing efficiencies of population control methods for responding to introductions of transboundary animal diseases in wild pigs. Preventive Veterinary Medicine 233, 106347.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Treichler JW, VerCauteren KC, Taylor CR, Beasley JC (2023) Changes in wild pig (Sus scrofa) relative abundance, crop damage, and environmental impacts in response to control efforts. Pest Management Science 79, 4765-4773.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Zohdi TI (2021) DEM modeling and simulation of post-impact shotgun pellet ricochet for safety analysis. Mathematics and Mechanics of Solids 26, 1108-1119.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |