Characteristics and determinants of quality non-directive pregnancy options counselling: a scoping review

Kari Dee Vallury A B * , Amanda Asher A C , Olivia Sarri A C and Nicola Sheeran B

A B * , Amanda Asher A C , Olivia Sarri A C and Nicola Sheeran B

A

B

C

Abstract

Non-directive pregnancy options counselling (POC) is a core component of comprehensive reproductive health care for pregnant people wanting support in making a pregnancy outcome decision. Approximately one quarter of people with unintended pregnancies and people seeking abortion care seek POC. This study synthesises global evidence on access to and characteristics of quality non-directive POC. We searched five health databases in line with PRISMA guidelines. Primary research articles (published in English, 2011–2023) were included if they addressed provision, experiences, or characteristics of non-directive POC. Data were synthesised and organised thematically. Twelve of the 4021 unique citations identified were included in the review. Four themes were generated: (1) characteristics of quality non-directive POC; (2) provider-level determinants of care quality and provision; (3) patient level factors impacting the desire for and receipt of care; and (4) organisational setting and legal determinants of provision and quality of care. Abortion-related values and policies at the provider, organisational and legislative levels were the most common and salient determinants of POC access and quality. Quality POC includes non-directive, empathetic, compassionate discussions about all pregnancy options that convey non-judgement and respect. However, we identified provider, organisational setting, and legal level determinants that disproportionately impact access to POC for marginalised pregnant people. Research regarding POC access and quality outside of the USA is needed. Upskilling primary care and other health professionals in POC and embedding referral pathways to non-directive POC and abortion care will support Australia to achieve its commitment to universal access to reproductive health care by 2030.

Keywords: abortion, counselling, informed decision making, pregnancy, pregnancy options counselling, reproductive autonomy, reproductive health, review.

Introduction

Non-directive pregnancy options counselling (POC) is the recommended best practice counselling method for pregnant people wanting to discuss or receive support regarding making, enacting, or communicating a pregnancy outcome decision.1–6 It is characterised by the provision of short-term, safe, unbiased information, and discussions about all three pregnancy options including continuation of a pregnancy and parenting, continuation of pregnancy and adoption, alternative or kinship care, and abortion.7–11 Non-directive POC counsellors also provide patients with advocacy, referrals, and support they need to access appropriate health and social services.12 In particular, they often play a critical role in facilitating access to abortion care by supporting clients to navigate complex and variable abortion care pathways.13

Not all pregnancy decision-making support involves use of counselling techniques in facilitated counselling sessions. It can also involve conversations and provision of information about pregnancy options without use of counselling techniques. For the remainder of this article, the acronym ‘POC’ is used to reference formal counselling and other forms of non-directive pregnancy decision-making support, as these are commonly conflated in the extant literature. The term ‘pregnant people’ is used to refer to all pregnant people, including those who identify as women, trans, non-binary or gender expansive, in line with language use in similar research and by the World Health Organization.14–16

In Australia, non-directive POC is delivered by a combination of specialist trained pregnancy options counsellors working in family planning organisations, abortion services and non-government organisations, and health professionals working in primary care and hospital settings. A survey of women who had experienced unplanned pregnancy found approximately 25% wanted to speak with a counsellor before making a pregnancy outcome decision.17 Registered health professionals recorded 31,499 of Medicare funded instances of non-directive POC nationally in the 2022–2023 financial year, while a non-government organisation providing non-directive POC in Queensland reported supporting 15–20% of abortion seekers in the state each year.18,19 Globally, research has identified high levels of demand and unmet need for non-directive POC.1,16,20–23

As part of its National Women’s Health Strategy, the Australian Government has committed to achieving universal access to reproductive health care, which includes non-directive POC and care for all pregnancy options, by 2030.24 To achieve this, a comprehensive understanding of the accessibility and characteristics of POC that effectively supports realisation of preferred pregnancy outcomes is needed.2,16,25,26 To guide evidence-based best practice, the aims of this review are to synthesise evidence about: (1) the determinants of the provision and accessibility of non-directive POC; and (2) what constitutes quality non-directive POC.

Methods

Literature was systematically reviewed and reported in line with the Preferred Reporting Items for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR).27

Search strategy

Studies were identified through structured searching of PubMed, Embase, PsycInfo, Web of Science, and CINAHL databases. The search was developed and tested with support from an expert health research librarian resulting in the final search strategy (Table 1).

| Search in: | ‘Title’ and/or ‘abstract’ | |

|---|---|---|

| Connected with ‘OR’ | Unplanned OR unwanted OR uninten* OR unexpected OR mistimed OR ‘pro choice’ OR ‘pro-choice’ OR ‘all options’ OR ‘all-options’ OR options OR abortion OR termination OR ‘decision making’ OR ‘decision-making’ | |

| Connected with ‘AND’ | ‘pregnan*’ AND ‘counsel*’ | |

| Connected with ‘NOT’ | ‘Contracept*’ NOT ‘family planning’ | |

| Filters applied | English |

Study selection and quality assessment

Studies were included in the review if they reported: (1) primary research; (2) related to experiences accessing or providing non-directive POC or describing characteristics of non-directive POC; (3) where counselling was ‘pro-choice’/non-directive/inclusive of all pregnancy options; (4) published between 2011 and 2023 (an initial 2022 search for 10 years of research was updated in October 2023); and (5) written in English. Excluded from this review were studies pertaining to: directive POC, that is, pregnancy decision making support that is biased/not inclusive of all pregnancy options, and; genetic counselling or counselling in the contexts of prenatal screening or cancer in pregnancy.

The title and abstract of each citation were screened against the inclusion criteria by a single researcher. Full texts of selected articles were assessed by two authors with discrepancies resolved in consultation with the third author. Study quality and risk of bias of each included article was assessed by two authors independently using The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) ver. 2018.28 The MMAT assesses the likelihood that features of the study design or conduct of the study impacted findings and the methodological quality of each study, providing a sense of the certainty of the body of evidence.

Analysis

Data regarding study characteristics and outcomes were extracted from studies by three authors independently using a pre-developed table. Quantitative results were recorded as textual descriptions, allowing the synthesis and integrated analysis of qualitative and quantitative findings.29,30 Relevant results of each study were categorised under both pre-determined (aligning with the research questions) and derived thematic headings by two authors (AA and OS) independently. Authors KV, AA, and OS then worked together to assess and regroup findings, continually checking back with the original articles until distinct and coherent themes that addressed the research aims were developed.

Results

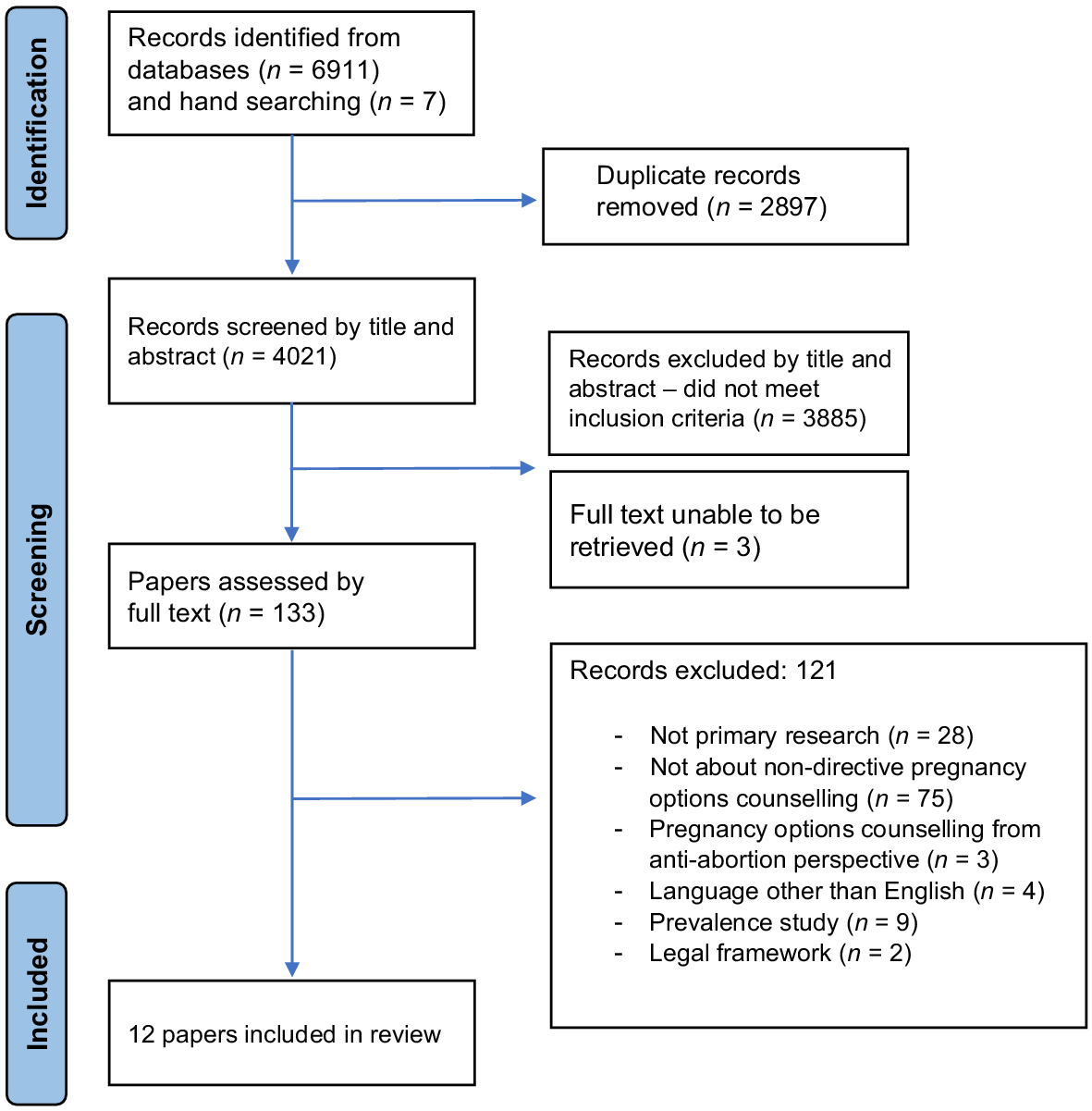

A total of 6911 citations were identified via the initial searches. Fig. 1 indicates the number of citations identified and excluded at each stage, and reasons for exclusion. The search strategy was designed for high sensitivity and, as such, low specificity (relevance) of the results of the initial searches was expected. Citations removed during abstract screening commonly focused on other forms of pregnancy care or counselling for purposes other than to support pregnancy decision making, such as contraceptive counselling. Twelve studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the review.

Quality and bias assessment

Eleven studies were assessed to have a low risk of bias and high methodological quality according to MMAT criteria and one28 was assessed to have moderate risk of bias: its conclusions appear to extend beyond what the primary data substantiate, due to its format that presents primary data within a critique of literature and law. All articles were retained for analysis, as recommended by the MMAT user guide. However, conclusions drawn in Oberman and Lehmann31 that did not originate from the primary data they collected were not included as findings in this review.

Study characteristics

Table 2 outlines the characteristics and key findings of the 12 included studies. Most studies (n = 7) used qualitative research methods and were conducted in the USA (n = 10), with one study each from Ireland and the Netherlands. Pregnant people (women and non-binary people) comprised the largest participant group (seven studies, n = 1702), followed by health practitioners providing some form of pregnancy options care (four studies, n = 1206) and administrative staff from family planning organisations (one study, n = 37). None of the studies described provision of counselling for couples.

| Author/Year | Location | Study design; method | Participants | Outcomes | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bell et al. 14 | USA (national) | Qualitative: SSIs | 50 female and non-binary individuals, aged 18–35 years who had experienced adolescent pregnancies | Positive and negative attributes of POC experiences. | Quality POC determined by: Positive attributes – communication, neutrality, discussing all options, holistic assessment of support needed, information provision and follow-up care. Negative attributes – judgemental communication, directive counselling, insufficient time and resources, confidentiality concerns. | |

| Berglas et al. 2 | Prenatal care facilities; Louisiana, Maryland, USA | (Primarily) quantitative; survey and brief structured interviews | 586 pregnant women | Determinants of accessibility: decision certainty, interest discussing options with prenatal care provider, priority populations. | People preferring abortion significantly more likely to want options counselling. 3% low decision certainty pre-counselling. 9% participants interested in POC. | |

| Chor et al. 32 | Hospital-based abortion clinics, USA | Qualitative; SSIs | 30 women who have had an abortion | Barriers to discussing pregnancy options with regular gynaecologic care provider. | Many women reluctant to discuss abortion preference with regular gynaecologic provider as wanted to (1) keep private, (2) avoid being dissuaded, (3) maintain ongoing relationship, (4) shield provider from involvement in decision. Reluctance due to anticipated judgement, believing abortion outside gynaecologic scope of practice, or believing abortion not in line with provider values, including at religious institutions. | |

| Coleman-Minahan 3 | Colorado, USA (state-wide) | Quantitative; survey | 419 advanced practice clinicians | Determinants of POC provision: providers’ values and types of POC provided. | 48% providers discussed all options. Provider religious and personal objection and lack of knowledge most common rationale for being unwilling to discuss abortion as an option. | |

| French et al. 33 | Prenatal and abortion clinics, Nebraska, USA | Qualitative; SSIs | 28 pregnant women | Preferences regarding discussing pregnancy options with health providers. | Agreement across settings that POC should be offered routinely, with respect to patient autonomy, avoid assumptions about women’s preferred outcomes, and include consideration of health and fertility intentions. Some women preferred no POC to maintain privacy, avoid discussing abortion, or high decision certainty. | |

| Goenee et al. 20 | GP clinics, Netherlands | Quantitative; registration form analysis | 667 pregnant women | Components of ‘unwanted pregnancy’ counselling provided by GPs. Impact of counselling on pregnancy decisions. | 84% of women decided pregnancy outcome before GP consult. 93% maintained initial decision after consult. Options other than women’s initial preferences discussed with 21% participants (41% undecided participants). Those who discussed options with GP were four times more likely to change mind than those who did not. | |

| Holt et al. 34 | USA (national) | Quantitative; survey | 789 primary care physicians | Determinants of POC provision, abortion dissuasion, and abortion referrals. | 26% provided routine options counselling for unintended pregnancy. 71% believed training in options counselling should be required. Christian physicians who attended religious services at least twice/month less likely to discuss all options. | |

| Mahanaimy et al. 15 | California, USA | Qualitative; SSIs | 25 people aged <25 years old with unintended pregnancies | Perceptions about interactions with providers and perceived quality of POC care. | Determinants of quality care include provision of comprehensive information and an empathic, non-judgemental provider. | |

| Nobel et al. 4 | Publicly funded FPOs, Ssouth USA | Quantitative; survey | 316 pregnant people | Options discussed. Patient satisfaction with POC. | Patients reported higher satisfaction when all pregnancy options were discussed during counselling. | |

| Oberman and Lehmann 31 | State where abortion criminalised, USA | Qualitative: SSIs | 25 doctors (not conscientious objectors) | Obligations regarding providing abortion information during POC in contexts of abortion criminalisation. | Doctors concerned about legality and consequences of having abortion conversations. Some restricted abortion information due to legal uncertainty. Others provided information as activism. | |

| Ryan et al. 35 | Public Crisis Pregnancy Counselling services, Ireland | Qualitative; SSIs | Seven counsellors | Experiences providing POC. Determinants of quality care. | Pro-choice values considered essential. Values clashes between counsellor and client impedes therapeutic relationship and does not allow space to discuss options without judgement or pressure. | |

| White et al. 36 | 37 FPOs, Texas, USA | Qualitative: SSIs | 37 administrators | Determinants POC provision: organisational protocols and practices regarding POC and abortion referrals. | Comprehensive POC more common among Title-X A vs state funded FPOs (restricted from providing abortion referrals): All Title X vs <50% state-funded services offered POC. Some state funded FPOs felt giving abortion information would jeopardise funding. |

SSI, semi-structured interviews; FPO, family planning organisation/clinic.

Themes

The four themes generated were: (1) characteristics of quality non-directive POC; (2) provider-level determinants of care quality and provision; (3) patient level factors impacting the desire for and receipt of care; and (4) organisational setting and legal determinants of provision and quality of care.

Quality non-directive POC was characterised as client-centred with verbal and non-verbal demonstrations of non-judgement and respect. Consumers’ experiences of non-judgemental language, validation, neutral or supportive attitudes, and provision of accurate and holistic information were found to be critical determinants of positive care experiences.2,4,14 Young people described non-verbal cues, such as professionals taking time to gauge their emotional states before communicating important information, and displays of empathy and compassion, as markers of respectful care.14

Non-judgemental care also included a discussion about all pregnancy options (abortion, adoption, parenting), irrespective of professionals’ personal assumptions/stereotypes about the preferences of pregnant people from different population groups. A counsellor in an Irish study described, ‘When you can park up your own personal beliefs, then in terms of ethics you’re being client centred…’ (p. 29).35 Universally offering discussions about all pregnancy options, irrespective of a person’s age or pregnancy intention, resulted in higher satisfaction with care.2,4,14,15,33

Key determinants of whether health professionals engaged in provision of quality non-directive POC were personal values related to pregnancy and abortion,3,14,15,32–35 religious affiliation,3,34 and knowledge and training.3,4

Both health professionals and pregnant women believed that health professionals had an obligation and responsibility to present all pregnancy options to pregnant people, irrespective of their personal values.33,34 Even so, the values of healthcare providers regarding pregnancy and abortion were found to directly impact the likelihood a pregnant person received non-directive, non-judgemental POC.3,14,15,32–35 For example, in a study of 419 advanced practice clinicians in the US, professionals’ personal objections to abortion were the most cited reason for not providing non-directive (abortion inclusive) POC.3 Similarly, qualitative studies in the USA found health professionals with religious affiliations were less likely to discuss all pregnancy options than those without.3,34 For example, Christian healthcare providers with higher levels of religiosity were found to be half as likely than providers with no religious affiliation to provide non-directive POC and four times more likely to engage in abortion dissuasion.34

Two studies identified that providers who had received training in POC or abortion counselling were more likely to offer non-directive POC than those without training.3,4 One study found that pregnant people were substantially more likely to report that they had discussed all pregnancy options (abortion, adoption, parenting) with their provider if the provider had been trained in POC (18%) compared with those who saw providers who had not received training (4%).4 A US study of nurse-midwives, women’s health nurse practitioners, and physicians’ assistants found only 48% counselled their patients about all three pregnancy options. A lack of knowledge was the primary reason they were unwilling (64%) or unable (79%) to discuss all options.3

Patient-level factors impacting desire for, confidence requesting, and receipt of non-directive POC included recent food insecurity, anticipated stigma, pregnancy intention/preferred outcome, decision certainty, race, and age. Berglas and colleagues found that pregnant people who experienced food insecurity in the year prior to pregnancy were significantly more likely to want and need non-directive POC,2 concluding that those experiencing immediate economic insecurities may have greater need for support. Health professionals reported that a lack of comprehensive POC was most likely to impact pregnant people facing informational and access barriers, including socio-economic disadvantage, lower educational attainment, and people living in rural and remote areas.2,31

Anticipating abortion stigma from a health professional, assuming abortion was not in scope for a particular health professional, and the presence of a partner or parent in health consultations reduced requests for and participation in POC.14,32

Pregnancy intention on first presentation to a health service influences a pregnant persons’ likelihood of receiving and desire for non-directive POC.2,4,20,32 Pregnant people with low decision certainty (a minority in all studies) were found to be significantly more likely to want POC than people who were more certain about their decisions.2,20,32,33 Pregnant women expressing a preference for abortion or adoption were also found to be more likely to want POC than people who had decided to continue a pregnancy.2

In the Netherlands, pregnant people who expressed an initial preference for abortion were less likely to have all pregnancy options discussed with them than those with an initial preference to continue a pregnancy, a large quantitative study found.20 In contrast, pregnant people at government-funded family planning services in a southern state of the USA were twice as likely to receive counselling around all pregnancy options if they had a preference for abortion versus pregnancy continuation.4 Primary care physicians in the US more commonly offered prenatal care information than POC to pregnant people who were undecided about their pregnancy outcome.34

There was some evidence to suggest that the race/ethnicity and age of the patient influenced access to non-directive POC. Black patients in the USA were less likely than others to receive the pregnancy options and abortion-related information, referrals and support they want,4 while young people reported a bias towards providers assuming they want abortion rather than prenatal care information.14

The legal context and organisational setting in which health care was delivered was found to influence patients’ comfortability seeking and professionals’ willingness to provide non-directive POC. Healthcare providers in both the USA and Ireland described being deterred from discussing abortion as an option when they perceived legal and financial risks associated with abortion restrictions, limiting provision of non-directive care (p. 5).31,35,36 Organisational policies that prevented abortion referrals were found to also prevent the provision of non-directive POC, while policies requiring or encouraging non-directive POC provision increased routine provision, irrespective of broader abortion-related restrictions.36

Religious affiliation of the organisation impacted patient willingness to discuss abortion. For example, pregnant people who perceived their values or preferences were likely to conflict with their provider’s religious values and who feared judgement by providers working in religiously affiliated hospitals/services reported hesitancy to discuss abortion and were less likely to receive non-directive POC.32,35 As one participant described, ‘it was a catholic hospital… so it was like… I’m not gonna talk to them about it [abortion]’ (p. 439).32

Discussion

This study reviewed the limited available literature to identify patient, provider, setting, and legal/policy determinants of the provision and accessibility of non-directive POC, and characteristics of best practice POC. Overall, non-directive POC was widely considered to be an essential reproductive health service that relevant health professionals should be/are professionally obligated to offer.5,26,31,33,34 However, access to non-directive POC was found to be highly variable and impacted by legal and policy contexts, provider and service-level values and religious affiliations, and a range of patient-level factors including food insecurity, stigma, preferred pregnancy outcome, decision certainty, race, and age.

Anti-abortion and religious values, policies and legislation emerged as key barriers to access to non-directive POC, operating at both systemic and interpersonal levels.21,31,35,36 Receiving care from health professionals holding abortion-supportive beliefs predicted the provision and receipt of non-directive POC, while seeking care from religious-identifying providers and services reduced the likelihood of requesting and receiving wanted non-directive POC.3,34,38,39 Similarly, anti-abortion values held by professionals and organisations impacted the quality of POC available to patients, believed to impede therapeutic relationships and reducing the likelihood of receiving non-judgemental and empathetic care and comprehensive information.15,35

In Australia, POC is commonly delivered in primary care and hospital settings. This review indicates that the accessibility of non-directive POC, and abortion referral pathways which POC often facilitates, is likely undermined by the prevalence of religious healthcare institutions and professionals with explicitly anti-abortion policies and beliefs.40,41 Research has found that health professionals in Australia contravene conscientious objection laws, including failing to provide accurate pregnancy options information and referrals, delaying access to abortion care, and leading to distress and negative health consequences.40 Ensuring access to non-directive POC is likely to play a vital role in enabling access to informed pregnancy decision making and equitable access to reproductive healthcare services in this context.42 In addition, a lack of training among health professionals in and knowledge about pregnancy options (including abortion) and non-directive POC limits its integration and provision in primary and other pregnancy care settings.3,9,43 Training health professionals in POC has been shown to increase its provision and accessibility.3,4

Our findings suggest that pregnant peoples’ desire for POC is linked to pregnancy intention, those preferring to choose abortion or adoption more likely to want POC than those choosing pregnancy continuation.2 It appears likely that pregnant people seek POC for decision affirmation because of abortion stigma. Abortion stigma is associated with low decision certainty due to a conflict between a pregnant persons’ preference and what is perceived to be socially, morally, and/or culturally acceptable.44–46 As such, POC providers hold immense power over the knowledge, stigmatisation (or normalisation), and access to services that patients need to identify and realise their reproductive preferences.47 Non-directive POC may be particularly critical enabler of reproductive choice in settings where, and among pregnant people for whom abortion stigma is particularly prevalent.

There is evidence to suggest that POC is used as a tool to undermine reproductive autonomy in some settings.5,26,48–50 Policies that mandate POC under the guise of ‘informed consent’, and religiously affiliated ‘Crisis Pregnancy Centres’ in and beyond the USA, use POC to spread misinformation and dissuade pregnant people from seeking abortion.14,51,52 A lack of provision of abortion information during POC (i.e. directive POC) is particularly likely to impact people who are afraid about or lack accurate knowledge about abortion, exacerbating the impacts of stigma and anti-abortion misinformation and reducing access to pregnancy choices.53 Evidence from this review suggests best practice involves universally offering, while not forcing, access to non-directive POC to ensure equitable access to all pregnancy options while avoiding paternalistic, anti-abortion mandates and assumptions.25,33

Non-directive POC and decision-making support is of highest quality and is most satisfactory to pregnant people when it is non-judgemental, includes information about all pregnancy options, is provided as early in pregnancy as possible, and universally offered (not mandated), irrespective of a pregnant person’s context or characteristics. When delivered in this way, it has the potential to support a reduction in reproductive health inequities and facilitate universal access to all pregnancy options, irrespective of the setting in which it is delivered.4 Alongside further integration of non-directive POC into primary and generalist health settings, specialist POC services play a critical role in upskilling professionals in non-directive POC. Further, commonly offering online and/or phone counselling, these services are particularly vital in enabling access to information and abortion care for pregnant people in rural and remote areas, where conscientious objection has been found to be particularly prevalent and services are limited.13

Implications for practice

Non-directive POC and decision-making support, whether delivered in a sexual and reproductive health specialist services or primary and tertiary healthcare settings, should be provided by pro-choice professionals trained in values clarification, pregnancy options, local pathways, wrap-around supports, conscientious objection obligations, and abortion stigma.

Health professionals providing non-directive POC can support consumers to identify safe (non-directive) services by promoting their pro-choice values, provision of non-directive POC, and support for or provision of abortion (referrals) clearly on their consumer-facing materials, including websites.

The characteristics and determinants of quality non-directive POC identified in this review provide a foundational evidence-base to inform the development of practice guidelines, training for healthcare providers, and future research.

Non-directive POC is most often offered and received by pregnant people accessing services without religious affiliations. Where religiously affiliated and/or anti-abortion health services receive public funding for pregnancy care, they should be required to demonstrate effective provision of or referral pathways to non-directive POC and abortion-related care. Services may consider explicitly recruiting professionals with pro-choice values and conducting audits of the proportion of conscientious objectors in a team to ensure patient rights and access to care for all pregnancy outcomes can be protected.

Limitations and future directions

Ten of the 12 included studies were undertaken in the USA where abortion care is increasingly restricted and more politicised, particularly since the recent Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organisation ruling,54 than in other ‘high-income’ countries.43,55 This lack of geographical diversity of data sources indicates a potential limitation to the generalisability of the findings of this review. Given our findings that quality POC involves discussing all pregnancy options including abortion, and that abortion-related attitudes, values and policies impact the likelihood this will occur, dominant discourses around abortion appear intertwined with POC quality and access. Research in a greater diversity of high-income country settings, where abortion access is being commonly improved and there is widespread public support for legal abortion,55 may identify alternate key determinants of POC access and quality. Australian research is needed to ensure local barriers and enablers are sufficiently understood and addressed.

Furthermore, there was limited mention in the included studies of the role POC plays in screening and safety planning in contexts of intimate partner violence and reproductive coercion and abuse. POC provides a central opportunity to screen for violence and coercion, and pregnant people experiencing reproductive coercion and abuse appear to be more likely than other pregnant people to desire POC to support decision making.9,56 Research is needed regarding: (1) local determinants of the accessibility and quality of non-directive POC; (2) the impacts of POC on reproductive health outcomes, equity and autonomy; and (3) the role of pregnancy options counsellors in identifying and responding to domestic and family violence, including reproductive coercion and abuse.

Finally, The English language limitation could have resulted in relevant studies being missed by the systematic search.

Conclusion

This review found that quality POC is characterised by non-directive, empathic, compassionate discussions about all pregnancy options (abortion, adoption and parenting), with verbal and non-verbal cues conveying non-judgement and respect. However, a range of patient, provider, organisational setting, and legal level determinants impact on a pregnant person’s ability to access non-directive POC, including anti-abortion values and policies. A lack of comprehensive pregnancy options information is likely to disproportionately impact the capacity of marginalised pregnant people to make and enact informed pregnancy outcomes decisions. Upskilling primary care and other health professionals to deliver non-directive POC, and embedding referral pathways to non-directive POC and abortion care throughout the health system, will be critical if Australia is to achieve its commitments to universal access to reproductive health care by 2030.

CRediT statement

Kari Vallury: Conceptualisation, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Formal analysis, Visualisation, Writing – review and editing. Amanda Asher and Olivia Sarri: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Visualisation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. Nicola Sheeran: Supervision, Writing – review and editing.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable as no new data were generated or analysed during this study.

Conflicts of interest

At the time of this research, KV was employed by an organisation providing non-directive pregnancy options counselling. The other authors have no conflicts to declare.

References

1 Australian Psychological Society. Pregnancy support counselling: medicare funded services; 2024. Available at https://psychology.org.au/psychology/medicare-rebates-psychological-services/medicare-rebates-pregnancy-services [accessed 27 August 2024]

2 Berglas NF, Williams V, Mark K, Roberts SCM. Should prenatal care providers offer pregnancy options counseling? BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018; 18(1): 384.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

3 Coleman-Minahan K. Pregnancy options counseling and abortion referral practices among Colorado nurse practitioners, nurse-midwives, and physician assistants. J Midwifery Womens Health 2021; 66(4): 470-477.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

4 Nobel K, Ahrens K, Handler A, Holt K. Patient-reported experience with discussion of all options during pregnancy options counseling in the US South. Contraception 2022; 106: 68-74.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

5 Rebić N, Gilbert K, Soon JA. “Now what?!” A practice tool for pharmacist-driven options counselling for unintended pregnancy. Can Pharm J 2021; 154(4): 248-255.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

6 Shaddeau A, Nimz A, Sheeder J, Tocce K. Effect of novel patient interaction on students’ performance of pregnancy options counseling. Med Educ Online 2015; 20: 29401.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

7 American Academy of Paediatrics, Committee on Adolescence. Options counseling for the pregnant adolescent patient. Pediatrics 2022; 150(3): e2022058781.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

8 Children by Choice. Confidential & non-judgemental support for all pregnancy options; 2022. Updated 2024. Available at https://www.childrenbychoice.org.au/ [accessed 27 August 2024]

9 Lupi C, Ward-Peterson M, Chang W. Advancing non-directive pregnancy options counseling skills: a pilot study on the use of blended learning with an online module and simulation. Contraception 2016; 94: 348-352.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

10 Mavuso JM-JJ, Macleod CI. Contradictions in womxn’s experiences of pre-abortion counselling in South Africa: implications for client-centred practice. Nurs Inq 2020; 27: e12330.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

11 The Women’s. Pregnancy options counselling. Date unknown. Available at https://www.thewomens.org.au/health-information/unplanned-pregnancy-information/pregnancy-options-counselling [accessed 27 August 2024]

12 Children by Choice. Counselling; 2024. Available at https://www.childrenbychoice.org.au/information-support/counselling/ [accessed 27 August 2024]

13 Vallury KD, Kelleher D, Mohd Soffi AS, Mogharbel C, Makleff S. Systemic delays to abortion access undermine the health and rights of abortion seekers across Australia. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2023; 63(4): 612-615.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

14 Bell LA, Tyler CP, Russell MR, Szoko N, Harrison EI, Kazmerski TM, et al. Preferences and experiences regarding pregnancy options counseling in adolescence and young adulthood: a qualitative study. J Adolesc Health 2023; 73(1): 164-171.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

15 Mahanaimy M, Gerdts C, Moseson H. What constitutes a good healthcare experience for unintended pregnancy? A qualitative study among young people in California. Cult Health Sex 2022; 24(3): 330-343.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

16 World Health Organization (WHO). Abortion care guideline; 2022. Available at https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240039483 [accessed 3 June 2024]

17 Michelson J. 33. What women want when faced with an unplanned pregnancy. Sex Health 2007; 4(4): 297.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

18 Australian Government. Medicare item reports. Services Australia - Statistics - Item Reports; 2024. Available at humanservices.gov.au [accessed 20 June 2024]

19 Children by Choice. Submission to the Universal access to reproductive healthcare senate enquiry. CbyC- Senate Inquiry; 2022. Available at https://www.childrenbychoice.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/CbyC-Senate-Inquiry-2022.pdf [accessed 27 August 2024]

20 Goenee MS, Donker GA, Picavet C, Wijsen C. Decision-making concerning unwanted pregnancy in general practice. Fam Pract 2014; 31(5): 564-570.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

21 Hasstedt K. Unbiased information on and referral for all pregnancy options are essential to informed consent in reproductive health care. 2018; Available at Vol. 21: Guttmacher Policy Review Available at https://www.guttmacher.org/gpr/2018/01/unbiased-information-and-referral-all-pregnancy-options-are-essential-informed-consent.

| Google Scholar |

22 Shelley JM, Kavanagh S, Graham M, Mayes C. Use of pregnancy counselling services in Australia 2007–2012. Aust N Z J Public Health 2015; 39: 77-81.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

23 Wallace ME, Evans MG, Theall K. The status of women’s reproductive rights and adverse birth outcomes. Womens Health Issues 2017; 27(2): 121-128.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

25 Bain LE. Mandatory pre-abortion counseling is a barrier to accessing safe abortion services. Pan Afr Med J 2020; 35: 80.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

26 Dobkin LM, Perrucci AC, Dehlendorf C. Pregnancy options counseling for adolescents: overcoming barriers to care and preserving preference. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care 2013; 43(4): 96-102.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

27 Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018; 169(7): 467-473.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

28 Hong QN, Fàbregues S, Bartlett G, Boardman F, Cargo M, Dagenais P, et al. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ Inf 2018; 34(4): 285-291.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

29 Aromataris E, Lockwood C, Porritt K, Pilla B, Jordan Z (Eds). JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI; 2024. Available at https://synthesismanual.jbi.global, https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-24-01

30 Schick-Makaroff K, MacDonald M, Plummer M, Burgess J, Neander W. What synthesis methodology should I use? a review and analysis of approaches to research synthesis. AIMS Public Health 2016; 3(1): 172-215.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

31 Oberman M, Lehmann LS. Doctors’ duty to provide abortion information. J Law Biosci 2023; 10(2): lsad024.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

32 Chor J, Tusken M, Lyman P, Gilliam M. Factors shaping women’s pre-abortion communication with their regular gynecologic care providers. Womens Health Issues 2016; 26(4): 437-441.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

33 French VA, Steinauer JE, Kimport K. What women want from their health care providers about pregnancy options counseling: a qualitative study. Womens Health Issues 2017; 27(6): 715-720.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

34 Holt K, Janiak E, McCormick MC, Lieberman E, Dehlendorf C, Kajeepeta S, et al. Pregnancy options counseling and abortion referrals among US primary care physicians: results from a national survey. Fam Med 2017; 49(7): 527-536 Available at https://www.stfm.org/FamilyMedicine/Vol49Issue7/Holt527.

| Google Scholar | PubMed |

35 Ryan M, Nolan A, Vallières F. Lifting the cloak of secrecy: experiences of providing crisis pregnancy counselling in a changing legislative context in Ireland. Couns Psychother Res 2022; 22: 22-31.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

36 White K, Adams K, Hopkins K. Counseling and referrals for women with unplanned pregnancies at publicly funded family planning organizations in Texas. Contraception 2019; 99(1): 48-51.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

37 Marcella JS.. The title X program: setting standards for contraceptive and health equity. Am J Publ Health 2022; 112(S5): S511-S514.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

38 Fiol V, Briozzo L, Labandera A, Recchi V, Piñeyro M. Improving care of women at risk of unsafe abortion: implementing a risk-reduction model at the Uruguayan-Brazilian border. Int J Gynecol Obstet 2012; 118: S21-S27.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

39 Mavuso JM-JJ, Macleod CI. ‘Bad choices’: unintended pregnancy and abortion in nurses’ and counsellors’ accounts of providing pre-abortion counselling. Health 2021; 25(5): 555-573.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

40 Keogh LA, Gillam L, Bismark M, McNamee K, Webster A, Bayly C, et al. Conscientious objection to abortion, the law and its implementation in Victoria, Australia: perspectives of abortion service providers. BMC Med Ethics 2019; 20: 11.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

41 Lu D, Davey M. ‘I was shocked’: Catholic-run public hospitals refuse to provide birth control and abortion. The Guardian; 2023. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2023/aug/22/do-australian-catholic-hospitals-perform-abortions-provide-contraception-reproductive-care [accessed 27 August 2024]

42 Foster DG, Jackson RA, Cosby K, Weitz TA, Darney PD, Drey EA. Predictors of delay in each step leading to an abortion. Contraception 2008; 77(4): 289-293.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

43 IPSOS. Global views on abortion in 2021; 2021. Available at https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/ct/news/documents/2021-09/Global-views-on-abortion-report-2021.pdf

44 Foster DG, Gould H, Taylor J, Weitz TA. Attitudes and decision making among women seeking abortions at one U.S. clinic. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2012; 44(2): 117-124.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

45 Makleff S, Wilkins R, Wachsmann H, Gupta D, Wachira M, Bunde W, et al. Exploring stigma and social norms in women’s abortion experiences and their expectations of care. Sex Reprod Health Matters 2019; 27(3): 1661753.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

46 Rowland BB, Rocca CH, Ralph LJ. Certainty and intention in pregnancy decision-making: an exploratory study. Contraception 2021; 103(2): 80-85.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

47 Makleff S, Belfrage M, Wickramasinghe S, Fisher J, Bateson D, Black KI. Typologies of interactions between abortion seekers and healthcare workers in Australia: a qualitative study exploring the impact of stigma on quality of care. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2023; 23(1): 646.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

48 Hornberger LL, Committee on adolescence. Diagnosis of pregnancy and providing options counseling for the adolescent patient. Pediatrics 2017; 140(3): e20172273.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

49 Moss DA. Counseling patients with unintended pregnancy. Am Fam Physician 2015; 91(8): 574-576 Available at https://www.aafp.org/dam/brand/aafp/pubs/afp/issues/2015/0415/p574.pdf.

| Google Scholar | PubMed |

50 Oswalt SB, Eastman-Mueller HP, Baldwin A. Counseling college students after a positive pregnancy test: trends in practice. J Am Coll Health 2021; 69(2): 227-231.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

51 Kimport K. Pregnant women’s experiences of crisis pregnancy centers: when abortion stigmatization succeeds and fails. Symb Interact 2019; 42(4): 618-639.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

52 Owens SN, Shorter JM. Pregnancy options counseling. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2022; 34(6): 386-390.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

53 Bury L, Aliaga Bruch S, Machicao Barbery X, Garcia Pimentel F. Hidden realities: what women do when they want to terminate an unwanted pregnancy in Bolivia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2012; 118(S1): S4-S9.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

54 Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization. Supreme court of the United States. p. 3; 2022. Available at supremecourt.gov, https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/21pdf/19-1392_6j37.pdf

55 Osborne D, Huang Y, Overall NC, Sutton RM, Petterson A, Douglas KM, et al. Abortion attitudes: an overview of demographic and ideological differences. Polit Psychol 2022; 43: 29-76.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

56 Birdsey G, Crankshaw TL, Mould S, Ramklass SS. Unmet counselling need amongst women accessing an induced abortion service in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Contraception 2016; 94(5): 473-477.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |