Community-engaged strategies to improve sexual health services for adults aged 45 and above in the United Kingdom: a qualitative data analysis

Michel Nunez A § , Yoshiko Sakuma B § , Hayley Conyers

B § , Hayley Conyers  B , Suzanne Day C , Fern Terris-Prestholt D , Jason J. Ong

B , Suzanne Day C , Fern Terris-Prestholt D , Jason J. Ong  E F , Stephen W. Pan G , Tom Shakespeare H , Joseph D. Tucker

E F , Stephen W. Pan G , Tom Shakespeare H , Joseph D. Tucker  B C , Eneyi E. Kpokiri

B C , Eneyi E. Kpokiri  B and Dan Wu

B and Dan Wu  B I *

B I *

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

I

Abstract

Sexual health is an essential component of health and well-being across the life course. However, sexual health research often focuses on young adults and excludes those aged 45 years and older. We organized a national crowdsourcing open call and co-creation events to identify recommendations to improve sexual health service provision for middle-aged and older adults in the United Kingdom (UK).

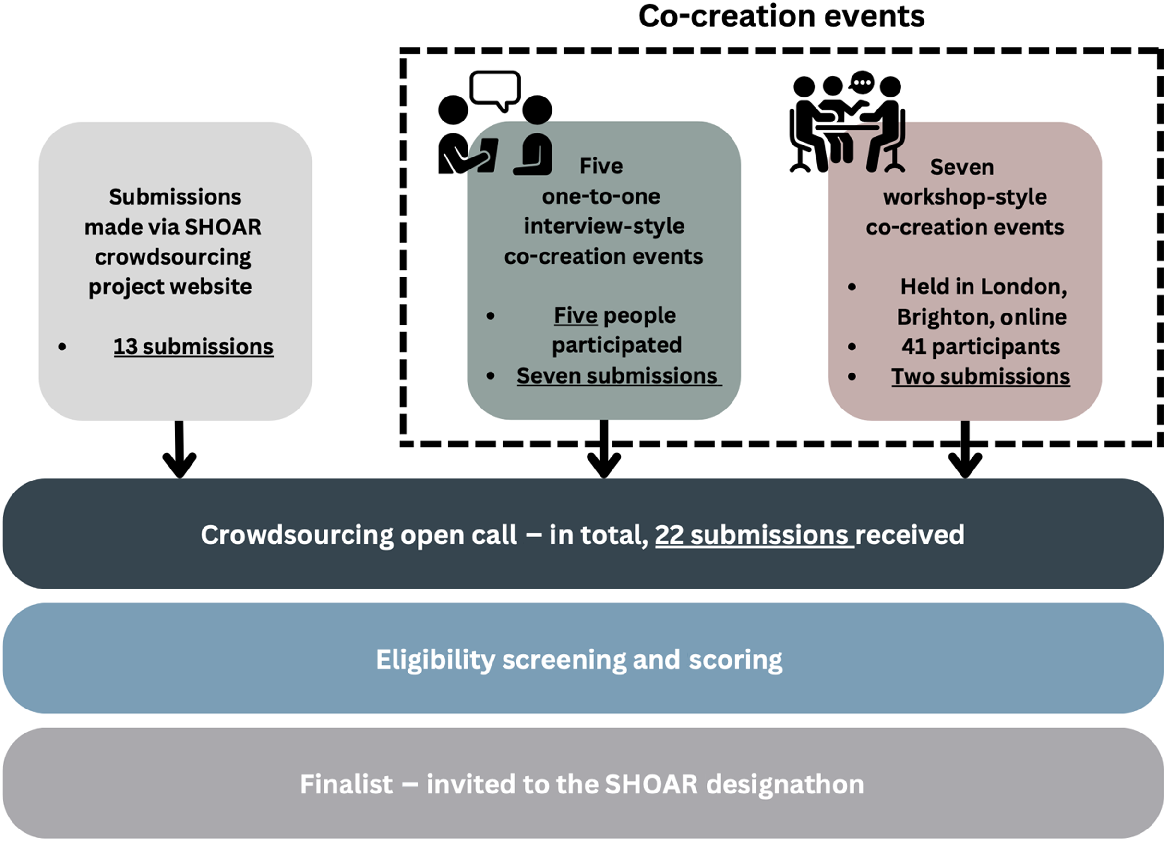

We conducted a crowdsourcing open call and seven co-creation events consisting of workshop-style meetings and one-to-one in-depth interviews. Open call submissions and qualitative data from the co-creation events were analyzed using a thematic approach. A social-ecological framework was used to code deductively, but new codes were allowed to emerge. Thematic categories were organized to describe factors influencing the accessibility and inclusivity of sexual health services for middle-aged and older adults.

We received 22 submissions in total; of those, 35% of participants reported a disability, 40% of individuals were aged 45–65 years, and 6% of submissions came from individuals that identified as gay/lesbian. Five key themes highlighted that improving sexual health services for adults aged 45 years and over requires a multi-leveled approach: increase sexual health education, enhance patient and provider relationships, utilize community-led sexual health promotion efforts and delivery of reliable sexual health information, improve inclusive sexual health services, and break down sexual health taboos against adults aged 45+ years.

Our data suggest that middle-aged and older adults can co-create compelling strategies to enhance sexual health services for middle-aged and older adults in the UK. Further implementation research is needed to pilot these strategies.

Keywords: barriers, co-creation, crowdsourcing, facilitators, middle-aged and older adults, qualitative, sexual health, United Kingdom.

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines sexual health as ‘a state of physical, emotional, mental and social well-being in relation to sexuality; it is not merely the absence of disease, dysfunction or infirmity’.1 Despite the fact that sexual health has to be protected and achieved throughout the life course, societal stereotypes persist that middle-aged and older people are not sexually active and do not have have sexual health needs and desires.2,3 These stereotypes seep into the healthcare system through negative provider interactions with middle-aged and older people, resulting in delays in both accessing and receiving care, and avoidance of sexual healthcare among this population.2

Even though a significant proportion of middle-aged and older adults are still sexually active, as highlighted by the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing, their sexual health needs remain inadequately addressed.3,4 This gap in healthcare is particularly concerning given that the proportion of new HIV diagnoses in the UK among individuals aged 50 years and over has increased from 9% to 16% over the past decade.5 Existing barriers to seeking sexual health care reported among this population have included being afraid that any sexual health difficulties will be dismissed as simply part of normal aging, health provider neglect of this topic, and chronic health conditions.6,7 Furthermore, the intersectionality between aging and disabilities makes the sexual health needs and accessibility of services for middle-aged and older people with disability even more complex, extending beyond the difficulties experienced by non-disabled middle-aged and older people.3 Evidence suggests that individuals with disabilities are as sexually active as their non-disabled counterparts,8 and they face a higher risk of sexual abuse and sexually transmitted infections.9,10

In England, adults aged 45 years and older are predicted to increase by 3.87 million between 2022 and 2042;11 and approximately 15.0 million people in the UK have a disability,12 with almost half of them aged 45 years and over. It is imperative to analyze sexual health service provision to ensure that it is accessible and inclusive for middle-aged and older people, including those with disability. To overcome these challenges, sexual health research incorporating the actual voices of the marginalized community is needed. Crowdsourcing and co-creation could enhance the engagement of middle-aged and older adults and people with disability in sexual health research and programs. A crowdsourcing open call involves inviting a large group to contribute ideas to solve all or part of a problem and then sharing the solutions, and co-creation events involve iterative, bidirectional collaboration between researchers and community members to generate new knowledge.13,14 While these methods have shown their effectiveness globally,13,15,16 they have not been implemented in the UK context of sexual health for middle-aged and older adults. This study aims to first apply crowdsourcing and co-creation methods to improve sexual health services for middle-aged and older adults in the UK. Therefore, a sexual health–focused crowdsourcing open call and co-creation events in the UK were organized to identify potential ideas and solutions for developing more accessible and inclusive sexual health services for middle-aged and older adults in the UK. This qualitative analysis aimed to identify innovative strategies from the national crowdsourcing open call and co-creation activities. The cut-off age in this study was 45 years and above, because this is the age at which sexual health issues such as erectile dysfunction and menopause become more common. Key findings from the study might help inform more accessible and inclusive sexual health services for all.

Methods

Study design

The Sexual Health in Older Adults Research (SHOAR) team at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) organized a crowdsourcing open call in January 2023 in the UK according to the WHO/Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases practical guide.17 The aim of this open call was to gather community-driven ideas and suggestions to improve the accessibility and inclusivity of sexual health services available for adults aged 45 and older.

For individuals who were interested in the open call but reported difficulties participating, the research team organized parallel co-creation events to alleviate participation barriers. These activities were organized with the aim of clarifying the objectives of the crowdsourcing open call and promoting participation, as many hesitated to submit ideas due to uncertainty about the concept of ‘crowdsourcing’ and doubts about the value of their contributions. An overview of the activities that were conducted in the study is presented in Fig. 1.

Crowdsourcing open call

The national and online crowdsourcing open call was held between 13 March 2023 and 31 May 2023. A dedicated crowdsourcing open call website was established to provide detailed project descriptions and submission portals, which included a text-to-read function (Supplementary material file S1). Participants were invited to contribute ideas on the theme: ‘Ways to Improve Sexual Health Services for Individuals Aged 45 and Over in the UK’. To accommodate the diverse needs and preferences of this age group, multiple submission channels were offered, including WhatsApp, an online submission form, email, phone calls, and postal mail. Submissions were limited to 500 words, or 2 min for phone calls.

Co-creation activities

As complementary events to the crowdsourcing open call, we organized various co-creation activities both in person and online. These included seven workshop-style sessions, conducted face-to-face and online, and five online one-to-one in-depth interviews, depending on the participants’ preferences. All activities were led by the study’s primary investigator (EK) and research assistant (HC). The design of the co-creation workshop session plans was led by two undergraduate students studying user design at the Royal College of Art. We gave participants hypothetical scenarios to discuss (Supplementary material file S2). Session plan design and discussion topics were determined iteratively, incorporating feedback from the wider research team and community representatives. The SHOAR project team and its research partner, the Independent Living Alternatives (ILA), coordinated and organized each session. Each co-creation session was documented by the facilitators through meeting minutes or audio recordings.

The submissions to the open call (including online submissions to the open call webpage and submissions made via co-creation events) were screened by the research team for eligibility (Table 1), and all eligible submissions were sent to the judging team. Each eligible submission was assessed by at least two independent reviewers using a judging rubric (1–10 score) based on the potential for impact, feasibility, and implementability.15 All the scores were averaged and ranked. People who submitted top-ranked submissions were recognized publicly, and finalists received prizes. Finalists were also invited to participate in a participatory designathon in London in March 2024 to refine ideas for future piloting.

Participants recruitment

The recruitment process was twofold. Initially, we established a steering committee comprising professionals with diverse public health backgrounds to guide the project.18 Subsequently, we implemented a multi-channel approach to promote the open call. This included online platforms such as Eventbrite, social media networks (Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram), and email listservs. To ensure broader reach, we also engaged in in-person recruitment through community organizations. Notably, we partnered with the ILA, an organization dedicated to serving adults with disabilities. This collaboration enhanced our ability to reach our target demographic and ensured a more inclusive participant pool.

Data analysis

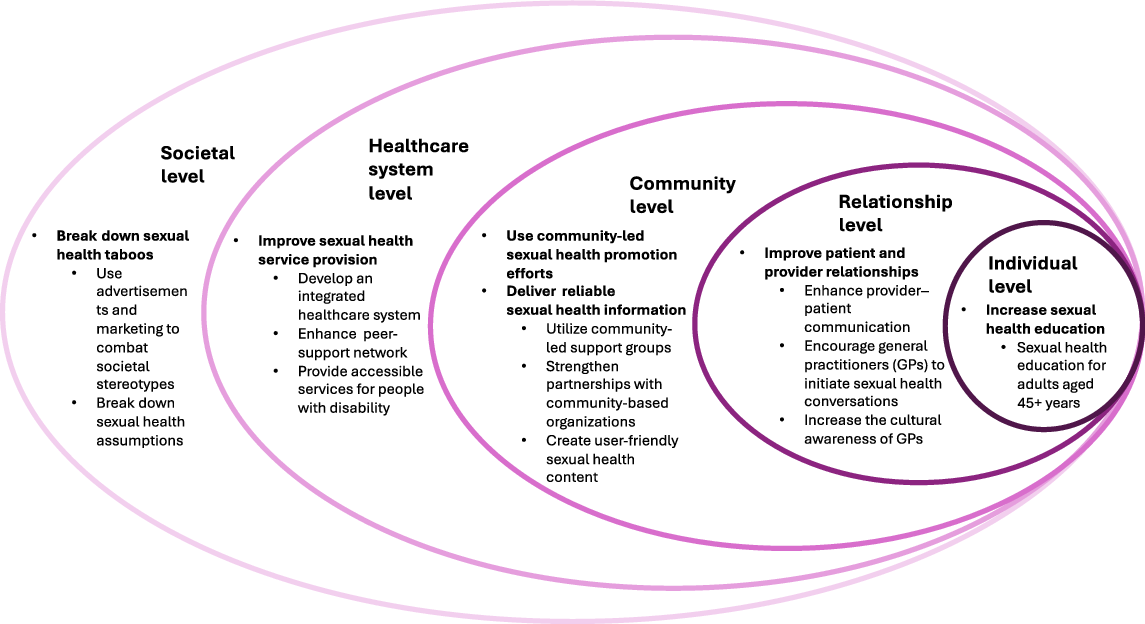

A qualitative thematic analysis approach was used to analyze the data collected from the crowdsourcing open call and the co-creation events. Thematic analysis was performed by following Durand and Chantler’s recommendations.19 We adapted a social-ecological framework20 to guide the development of codes and structure the findings.21 As a result of a large number of the solutions provided by participants targeting enhancements directly at the healthcare system level, we added the healthcare system. The model aids in conceptualizing how factors at each level ultimately influence the accessibility and inclusivity of sexual health service provision for middle-aged and older adults in the UK.

An MSc student (MN) and HC prepared the data by making copies of the original written submissions to facilitate highlighting and marking up. Subsequently, MN organized submissions in an Excel spreadsheet, allocating a tab for each community-engagement method: crowdsourcing open calls and co-creation events. Familiarization with the data involved reviewing each submission along with co-creation events summaries. Initial coding was done by ML through handwritten notes to gain further insight into participants’ narratives. A combination of inductive and deductive coding was employed. All coded data/themes were reviewed by HC and EK, an experienced qualitative researcher.

Patient and public involvement

The development of the study was informed by findings from literature reviews and several iterations of participatory activities.2 Healthcare professionals and adults aged 45 years and older, including people with disability and sexual minorities, played an integral role in the study design, recruitment, interpretation, and dissemination of findings to make sure to use inclusive language and make the contents accessible for all. The dissemination will be tailored to diverse needs, encompassing formats such as videos with transcriptions, podcasts, Wikipedia pages with text-to-read functions, conference presentations, and published papers.

Results

In total, we received 22 submissions, including 13 submitted through crowdsourcing open calls and 9 from the co-creation events. Participant characteristics are shown in Table 1. Of those, eight (35%) of participants reported a disability, 40% of individuals were between the ages of 45 years and 65 years, and one (6%) individual identified as gay/lesbian (Table 2).

| Demographic characteristics | Frequency (n = 22) | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| 45–54 | 4 | 18 | |

| 55–64 | 5 | 22 | |

| 74+ | 1 | 6 | |

| Not recorded | 12 | 52 | |

| Ethnicity | |||

| White/Caucasian | 6 | 27 | |

| Asian/Asian British | 1 | 6 | |

| Mixed multiple ethnic groups | 1 | 6 | |

| Not recorded | 14 | 60 | |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 6 | 27 | |

| Male | 4 | 18 | |

| Not recorded | 12 | 52 | |

| Reported disability | |||

| Yes | 8 | 35 | |

| No | 1 | 6 | |

| Not recorded | 13 | 56 | |

| Relationship status | |||

| Single | 2 | 10 | |

| Married | 2 | 10 | |

| Divorced | 2 | 10 | |

| Prefer not to say | 4 | 18 | |

| Not recorded | 12 | 52 | |

| Sexuality | |||

| Heterosexual | 6 | 27 | |

| Gay/lesbian | 1 | 6 | |

| Prefer not to say | 3 | 14 | |

| Not recorded | 12 | 52 |

Our thematic analysis revealed five key thematic strategies organized using an adapted social-ecological model for improving the sexual health of middle-aged and older adults (Fig. 2). These included needs to (1) increase sexual health education targeting this population; (2) enhance provider and patient relationships; (3) utilize community-led sexual health promotion efforts and delivery of reliable sexual health information; (4) improve inclusive sexual health services; and (5) break down sexual health taboos against adults aged 45+ years.

Adapted social-ecological model – influencing factors of sexual health service provision: ideas for inclusive and accessible sexual health services for UK adults aged 45+ years.12

Relationship level: improve patient and provider relationships

Many participants suggested incorporating conversation guides, such as question prompts, to facilitate communication between the provider and patient as a way to enhance sexual health services for middle-aged and older adults. Another suggestion, to reduce discomfort when discussing sexual health, was using a code word to trigger an alert when booking an appointment with a receptionist, who would notify the general practitioner (GP) to ask the patient about sexual health.

‘Because patients might not feel comfortable saying what’s wrong and some GPs won’t support appointments until they have more info: code word or phrase like ‘ask for Angela’ to be used with reception.’ [Open call contest, submission #22]

Some participants noted that GPs should ask middle-aged and older adults about intimacy. GP awareness of sexual health needs and desires for participants meant that providers could ask questions regarding personal life events, such as the death of a spouse, which affects the sexual health of patients:

‘My wife died. And was too unwell to have sex for about a year before she died … I do miss sex. Guidance for people like me on how, safely, to access commercial sex would be useful.’ [Open call contest, submission #1]

To create a positive relationship with providers, participants highlighted the importance of GPs’ cultural awareness.

‘Need for HCPs [healthcare professionals] to receive appropriate training and knowledge around SH [sexual health] information for older adults, particularly within diverse communities, to be able to provide culturally competent services and connections to care and support.’ [Open call contest, submission #5]

Community level: use community-led sexual health promotion efforts and delivery of reliable sexual health information

Participants saw community-led support groups as an important aspect of sexual health for adults aged 45 years and older because they offer an open space in which to discuss different sexual health topics:

‘GPs and specialists refer to the groups … The groups will … take place in closed community spaces, such as a community center. The facilitator should be 45+ and have good sexual health knowledge … to quality control the information and suggestions shared by the participants.’ [Open call contest, submission #8]

A lack of knowledge about where to find reliable and up-to-date sexual health information was a sentiment shared among some participants. They felt the National Health Service (NHS) should keep their online sources up to date by partnering with community advisory boards, such as charities, to accomplish this in the face of limited resources. Also, by leveraging day center partnerships, accessibility barriers to information could be broken down:

‘Offering pop-up services to people using day centers whether people with learning disabilities or older peopl… These are groups of people who do not traditionally use sexual health services and often are unaware of what is available.’ [Open call contest, submission #9]

Developing informative and user-friendly content through partnerships with middle-aged and older adults was a key suggestion. User-friendly content is content that is provided in different languages, contains inclusive images, has clear messaging about service availability, is in video format (to cater to those with visual impairments, those with limited internet access, and those who experience difficulties comprehending written materials), and is visually engaging.

‘Ask a group of ‘experts by experience’ who are 45+ years old to create educational leaflets, posters, and videos relevant to the group (i.e. with images of disabled people to encourage take up of sexual health services).’ [Open call contest, submission #4]

Healthcare system level: improve sexual health service provision

Participants advocated for an integrated healthcare system that centralizes multiple sexual health services and information. This comprehensive approach would facilitate one-stop access to health services, enable seamless information exchange among healthcare providers, and streamline patient referrals.

‘Regular ‘Annual Reviews’ … could be combined with other regular screening, scheduled appointments – which include standardized sexual health questions/prompts, followed by ‘one-stop shop’. Network of joined-up care with a trusted healthcare provider at the center (often GP) with consistent information sharing and clear referral pathways. ‘Health hubs’ mentioned in the Women’s Health Strategy (England only) as a possibility of piloting this approach.’ [Open call contest, submission #5]

Another participant mentioned the utilization of the HIV care model as a guide. Lastly, offering sexual health services to patients as an ‘opt-out’ service was suggested to prevent the middle-aged and older adult demographic from being excluded.

Many participants suggested peer-based approaches (e.g. support networks, peer navigators, patient advocates) to enhance sexual health services for middle-aged and older adults.

‘Peer navigators to form clear links from moment of diagnosis to more holistic support, facilitating signposting on to other support services as organised by healthcare providers via an ‘opt-out’ system. Option of online support could be helpful.’ [Open call contest, submission #5]

Providing accessible medical equipment and including middle-aged and older adults in the design process was seen as critical in the sexual health–seeking journey for those with mobility difficulties or physical impairment.

‘Disabled people must be included in the design and implementation of healthcare machinery, particularly for sexual health screening (e.g. mammograms, cervical screenings). Manufacturers should be required to consult with disability experts and advocates during the design and construction of devices used in a healthcare setting.’ [Open Call Contest, Submission #19]

Societal level: break down sexual health taboos

Some participants mentioned leveraging marketing and advertisements to dismantle taboos associated with the sexual health of middle-aged and older adults. Participants advocated new strategies to shift current marketing into more ‘fun and light marketing’. They suggested creatively including ‘edgy/taboo’ subjects, such as middle-aged and older adults being sexually active, to challenge societal stereotypes.

‘We need sexual health campaigns that include older people, condom brands need to use older people, lube brands ignore the over 45+, as do the vast majority of sex toy retailers’ [Open call contest, submission #12]

Discussion

This qualitative analysis identified strategies to improve the accessibility and inclusivity of sexual health services for middle-aged and older adults in the UK. Key findings highlighted that improving sexual health services needed to be addressed at different levels. This included improving provider and patient relationships, using community-led sexual health promotion efforts and delivery of reliable sexual health information, improving inclusive sexual health services, and breaking down sexual health taboos against them. This study expands the literature by using a crowdsourcing open call and co-creation methods for middle-aged and older adults focused on sexual health, including voices of people with disability.

At the relationship level, to improve the patient and provider relationship, participants urged providers to be more culturally aware, have a warmer attitude, and leverage strategic windows of opportunity to prompt sexual health discussions. Existing literature supports the idea of strategically placing tailored brochures for older adults in waiting and exam rooms.22 Increasing provider training at the healthcare system level is also imperative since the topic of sexual health among middle-aged and older adults is not always perceived as ‘legitimate’ by GPs, and they may lack training in discussing sexuality with older individuals.23 One of the great examples of supporting health professionals with sexual health communication with middle-aged and older adults is the Sexual Health In the over ForTy-fives (SHIFT) project, led by Tyndall et al.,24 which aims to support and understand sexual health needs by providing online training and virtual learning resources for health and social care professionals. There is an obvious need for wider awareness and increased utilization of this kind of valuable resource among healthcare providers to improve sexual healthcare for this population. On the community front, community-led support groups, partnerships with charities, and incorporation of middle-aged and older adults in the creation of sexual health messaging would fill sexual health service provision gaps by leveraging community-level resources.13 The benefits highlighted by the current literature on community peer navigators, having them use social media to disseminate sexual health information and raise awareness among community organizations about the challenges that marginalized groups face when accessing sexual health services, could translate to the sexual health of middle-aged and older adults and have a positive impact for this population.21 However, further research is needed on the benefits of community-based and community-led support groups, specifically tailored for adults aged 45 years and older.

In the context of the healthcare system, participants expressed a need for urgency in developing accessible medical equipment for routine procedures to reduce the burden of poor health, and ensure healthcare services accommodate individuals of diverse abilities. To promote accessible and inclusive sexual health services for middle-aged and older adults in the UK, incorporating the seven principles of universal design25 and including people with disability through the design phases should be key in future considerations. One-stop integrated care was also recommended to streamline appointments, facilitate information sharing among providers, and provide holistic patient-centered care. This aligns with the WHO’s strategy to promote ‘people-centered and integrated health services’. This approach aims to shift existing health service delivery, funding, and coordination to better meet the healthcare needs of all individuals,26 including the community of adults aged 45 years and above in the UK. All these strategies are essential for bringing about societal-level changes that prevent healthcare providers and societies from allowing their preconceived assumptions to affect the delivery of sexual health services.

While this study successfully engaged older adults aged 45 years and above on how to tailor sexual health services, there are some limitations worth noting. First, our sample included only one participant from sexual minorities. While this study provides valuable insights, it is important to note that the unique perspectives and experiences of LGBTQ+ individuals regarding sexual health may not be fully captured. Future research should consider targeted strategies to address the specific needs and challenges faced by sexual minorities in sexual healthcare. Second, we encountered a significant number of unrecorded responses in our demographic data collection. This missing information creates gaps in our understanding of the sample’s characteristics. It may limit our ability to identify how different demographic factors influence sexual health perspectives and needs across various population subgroups. Third, while the open call and co-creation activities were mostly promoted and organized in England, this study did not collect granular-level geographical information on participants. Future studies will need to address this limitation, as there is likely geographical heterogeneity in access to and provision of sexual health services. Despite these limitations, the qualitative, in-depth data gathered did provide insightful narratives of potential solutions that could aid in making positive changes to sexual health service provision in the UK.

Conclusion

The findings of this study provided insight into solutions for improving the accessibility and inclusivity of sexual health services for middle-aged and older adults in the UK, as gathered through community engagement efforts. The study highlights the urgent need for improvements across various levels of sexual health delivery to better accommodate the needs of this population.

Conflicts of interest

Joseph D. Tucker (co-Editor-in-Chief), Jason J. Ong (co-Editor-in-Chief), and Dan Wu (Associate Editor) are Editors of Sexual Health. To mitigate this potential conflict of interest they had no editor-level access to this manuscript during peer review. The authors have no further conflicts of interest to declare.

Declaration of funding

This work received funding from the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) grant number: ES/T014547/1.

References

1 World Health Organization. Sexual health. World Health Organization; 2024. Available at https://www.who.int/teams/sexual-and-reproductive-health-and-research-(srh)/areas-of-work/sexual-health [accesseded 12 October 2024]

2 Taylor A, Gosney MA. Sexuality in older age: essential considerations for healthcare professionals. Age Ageing 2011; 40(5): 538-43.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

3 Khan J, Greaves E, Tanton C, et al. Sexual behaviours and sexual health among middle-aged and older adults in Britain. Sex Transm Infect 2023; 99: 173-9.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

4 Stowell M, Hall A, Warwick S, Richmond C, Eastaugh CH, Hanratty B, McDermott J, Craig D, Spiers GF. Promoting sexual health in older adults: findings from two rapid reviews. Maturitas 2023; 177: 107795.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

6 Lee DM, Nazroo J, O’Connor DB, Blake M, Pendleton N. Sexual health and well-being among older men and women in England: findings from the English longitudinal study of ageing. Arch Sex Behav 2016; 45(1): 133-44.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

7 Tanton C, Geary RS, Clifton S, et al. Sexual health clinic attendance and non-attendance in Britain: findings from the third National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal-3). Sex Transm Infect 2018; 94(4): 268-76.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

8 Holdsworth E, Trifonova V, Tanton C, Kuper H, Datta J, Macdowall W, et al. Sexual behaviours and sexual health outcomes among young adults with limiting disabilities: findings from third British National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal-3). BMJ Open 2018; 8(7): e019219.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

9 Mailhot Amborski A, Bussières EL, Vaillancourt-Morel MP, Joyal CC. Sexual violence against persons with disabilities: a meta-analysis. Trauma Violence Abuse 2022; 23(4): 1330-43.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

10 Brennand EA, Martino AS. Disability is associated with sexually transmitted infection: severity and female sex are important risk factors. Can J Hum Sex 2021; 31: 91-102.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

11 Local Government Association. Breaking point: securing the future of sexual health services; 2022. Available at https://www.local.gov.uk/publications/breaking-point-securing-future-sexual-health-services [accessed 10 July 2024]

12 National Statistic. Family Resources Survey: financial year 2021 to 2022; 2023. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/family-resources-survey-financial-year-2021-to-2022. [accessed 20 April 2024]

13 Tucker JD, Day S, Tang W, et al. Crowdsourcing in medical research: concepts and applications. PeerJ 2019; 7: e6762.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

14 Greenhalgh T, Jackson C, Shaw S, Janamian T. Achieving research impact through co-creation in community-based health services: literature review and case study. The Milbank Quarterly 2016; 94(2): 392-429.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

15 Finley N, Swartz TH, Cao K, et al. How to make your research jump off the page: co-creation to broaden public engagement in medical research. PLoS Med 2020; 17(9): e1003246.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

16 Tang W, Wei C, Cao B, Wu D, Li KT, Lu H, et al. Crowdsourcing to expand HIV testing among men who have sex with men in China: a closed cohort stepped wedge cluster randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med 2018; 15(8): e1002645.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

17 World Health Organization. Crowdsourcing in health and health research: A Practical Guide; 2018. Available at https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/273039/TDR-STRA-18.4-eng.pdf

18 London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. Sexual health among older adults in China and the United Kingdom: a multi-disciplinary study; 2023. Available at https://gtr.ukri.org/projects?ref=ES%2FT014547%2F1#/tabOverview [accessed 23 August 2023]

20 Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. The social-ecological model: a framework for prevention; 2015. Available at https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/communityengagement/pce_models.html

21 Robles Arvizu JA, Mann-Jackson L, Alonzo J, et al. Experiences of peer navigators implementing a bilingual multilevel intervention to address sexually transmitted infection and HIV disparities and social determinants of health. Health Expect 2023; 26(2): 728-39.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

22 National Institute on Aging. Talking with your older patients; 2023. Available at https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/talking-your-older-patients [accessed 14 August 2023]

23 Hinchliff S, Carvalheira AA, Štulhofer A, et al. Seeking help for sexual difficulties: findings from a study with older adults in four European countries. Eur J Ageing 2020; 17(2): 185-95.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

24 SHIFT Project. Professional resources; 2020. Available at https://shift-sexual-health.eu/professionals/

25 National Disability Authority. The 7 principles. Centre for Excellence in Universal Design; 2020. Available at https://universaldesign.ie/what-is-universal-design/the-7-principles/ [accessed 31 August 2023]