Sustaining sexual health programs: practical considerations and lessons from the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief

Joseph D. Tucker A B * , Suzanne Day B , Ucheoma C. Nwaozuru C , Chisom Obiezu-Umeh D , Oliver Ezechi E , Kelechi Chima B , Chibeka Mukuka F , Juliet Iwelunmor G , Rachel Sturke H and Susan Vorkoper H

A B * , Suzanne Day B , Ucheoma C. Nwaozuru C , Chisom Obiezu-Umeh D , Oliver Ezechi E , Kelechi Chima B , Chibeka Mukuka F , Juliet Iwelunmor G , Rachel Sturke H and Susan Vorkoper H

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

Abstract

Enhancing the sustainability of sexual health programs is important, but there are few practical tools to facilitate this process. Drawing on a sustainability conceptual framework, this Editorial proposes four ideas to increase the sustainability of sexual health programs – early planning, equitable community engagement, return on investment, and partnerships to address social determinants. Early planning during the design of a sexual health program is important for sustainability because it provides an opportunity for the team to build factors relevant to sustainability into the program itself. Equitable community engagement can expand multi-sectoral partnerships for institutionalisation, identify allies for implementation, and strengthen relationships between beneficiaries and researchers. From a financial perspective, considering the return on investment could increase the likelihood of sustainability. Finally, partnerships to address social determinants can help to identify organisations with a similar vision. Existing sustainability frameworks can be used to measure each of these key elements. Several approaches can be used to enhance the sustainability of sexual health programs. The President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief provides potential lessons for increasing the sustainability of sexual health programs in diverse global settings.

Keywords: community engagement, financing, implementation science, measurement, partnerships, PEPFAR, sustainability, sustainment.

PEPFAR, the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, is the world’s largest sexual health program.1 Since the program was launched in 2003, PEPFAR has provided US$90 billion in support for comprehensive HIV services in over 50 countries. PEPFAR has previously experienced authorisation lapses, underlining the importance of sustainability in sexual health programs. What can we do to sustain sexual health programs over time? Moore et al. defined sustainability as some part of an implementation strategy or program enduring for a period of time, along with a continued benefit to the patient and health system.2 This Editorial builds on this by considering the drivers of sustainability of sexual health programs, introducing barriers to some of these drivers, and highlighting lessons from PEPFAR. We focus on PEPFAR because it has endured over two decades and may provide some illustrations of key factors to consider in planning for sustainability.

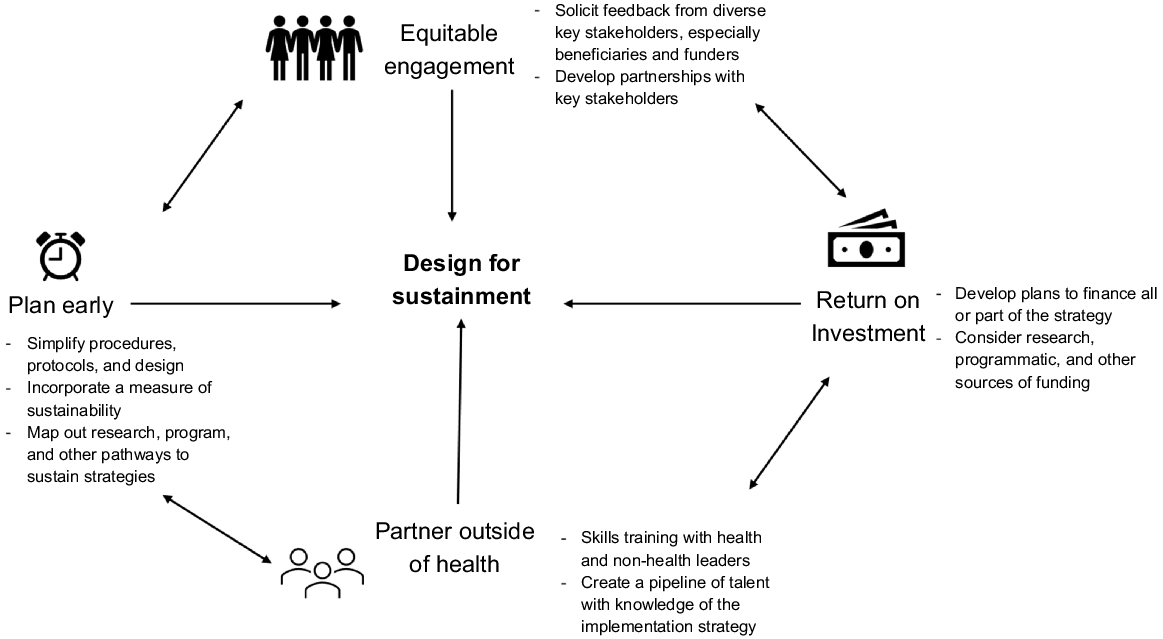

Understanding the sustainability of sexual health programs is important for several reasons.3 First, stopping programs known to be effective in the face of persistent public health needs can lead to a resurgence in disease. Second, substantial initial costs (financial, social, and human personnel) are often associated with launching new sexual health programs that make stopping interventions inefficient. Third, the closure of effective sexual health programs could dampen community interest in the topic. These issues are also relevant to re-launched programs because of the loss in momentum. Building on a working group organised by the Adolescent HIV Prevention and Treatment Implementation Science Alliance (AHISA), this commentary leverages data and examples from PEPFAR. This commentary proposes four distinct but interconnected ideas that researchers can use to increase the sustainability of sexual health programs (Fig. 1).

Overview of ideas to increase the likelihood of sustaining implementation strategies. Return on Investment.

Early planning during the design of a sexual health program is important for sustainability because it provides an opportunity for the team to build factors relevant to sustainability into the strategy itself from the onset. A systematic review of sustainability studies found that early planning during the design and adoption phases increased the likelihood of sustainability.4 Early planning for sustainability requires an operational definition of sustainability, metrics, and strategies that can be institutionalised or otherwise embedded in community practice.3 Potential barriers to early planning include uncertainty about the effectiveness of the strategy, lack of understanding related to implementation, and limited stakeholder interest in early-stage ideas. Sustainability requires consideration of which strategies are intended as a temporary service and which should be continued over a longer time. Implementation research can provide preliminary data on effectiveness and implementation. From PEPFAR’s inception in 2003, the program was designed with a clear strategic vision on the global HIV epidemic.5 This paved the way for sustaining the program over the past two decades.

Equitable community engagement is a second critical factor for ensuring the sustainability of sexual health programs. We define equitable community engagement as cultivating a diverse network of communities of who are interested in the health topic and may be affected by the health outcome. Equitable community engagement can expand public partnerships for institutionalisation, identify allies for implementation, and strengthen relationships between beneficiaries and researchers. Several studies have suggested that locally relevant community engagement enhances sustainability.6–8 Meaningful, enduring community engagement increases local ownership and collective self-efficacy.9 This sense of community ownership may facilitate adaptations in response to community needs. Potential barriers to equitable community engagement include lack of funding to ensure robust community participation, low research literacy among some community members, and entrenched inequities. At the same time, there are innovative methods for community engagement (e.g. co-creation, crowdsourcing)10,11 that require fewer resources and do not require extensive community literacy. PEPFAR invests in community-based organisations, trains local health workers, and supports youth programs.5 Several tools exist for measuring community engagement in the context of sustainability (Table 1).

| Program sustainability assessment tool12 | Integrated sustainability framework13 | Dynamic sustainability framework14 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early planning | Five items on strategic planning | Not an area of focus | Not an area of focus | |

| Equitable community engagement | Five items on partnerships with community | Community ownership in outer context | Part of organisational culture | |

| Partnership outside of health | Seven items on stakeholder relationships | Partnerships in process considerations | Part of practitioner team | |

| Return on investment | Six items on funding stability | Part of inner context considerations | Part of practice setting and ecological setting |

Considering the return on investment is another important dimension of sustainability. Return on investment measures the profitability of a program. Few sexual health programs generate revenue. Research studies evaluating sexual health programs often depend entirely on monetary support from a research grant for continuation. Sexual health researchers may not be interested in or know how to develop ways to finance a sexual health program. There may be limited data to prioritise funding decisions or limited political will to allocate more funds. Deepening relationships with the public sector, identifying alternative sources of revenue, cross-subsidisation, and innovative financing (i.e. giving a gift of free services and asking for donations to support subsequent people;15 crowdfunding16) could help to increase the likelihood of sustainability.17 Several social entrepreneurship programs have been used to increase the sustainability of sexual health programs.18 Potential barriers to considering the return on investment include lack of understanding financial aspects of an implementation strategy. Mapping promising existing funding mechanisms may be a helpful starting point for researchers and an opportunity to understand potential local solutions (e.g. microfinancing, leveraging community assets). PEPFAR’s clear demonstration of return on investment has been important in sustaining the program over time.5 Financing for sustainability can be measured in several ways (Table 1).

Building partnerships outside of health is also important for sustainability.19 Health strategies are often dependent on the social, educational, and economic capacity for continued implementation. Creation of a shared goal between potential partners may be one opportunity for enhancing sustainability by clarifying the mutually beneficial outcomes of a program. In addition, intentionally planning and building a platform for continued communication between partners may be helpful, with a focus on mutual accountability and transparency. For example, PEPFAR has developed partnerships with a diverse range of communities, including governments, private sector companies, faith-based organisations, and civil society groups.20 Potential barriers to partnerships outside of health are implementation silos in many jurisdictions, health goals that do not recognise the social determinants of health, and health-focused financing structures. These barriers can be reduced by using a social innovation approach21 that decreases silos, uses sustainable development goals, and considers the social impact of health interventions.

Examining how PEPFAR and other sexual health programs have been sustained during periods of uncertainty may also be useful. For example, during COVID-19, many sexual health programs were temporarily stopped. However, early planning in PEPFAR-supported countries ensured that programs were sustained during this period. HIV self-testing, multi-month dispensing of ART, and enhanced patient tracking were used to sustain essential HIV services.22 More recently, political threats related to reproductive health services stalled the reauthorisation of PEPFAR.23 In response, the creation of a Bureau of Global Health Security and Diplomacy by the Biden administration further reinforced PEPFAR’s role in global health security, integrating it more deeply in US foreign policy and consolidating efforts for sustainability.23

Sustainability needs to be considered in the local context and may be particularly important in resource-limited settings where there are fewer means to support new strategies and less existing infrastructure.24 This underscores the importance of considering sustainability in sexual health programs. More formal consideration of sustainability within implementation research can help to increase the likelihood of sustainability.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable as no new data were generated or analysed during this study.

Conflicts of interest

Joseph Tucker is a co-Editor-in-Chief of Sexual Health. To mitigate this potential conflict of interest they had no editor-level access to this manuscript during peer review. All other authors declare that they have no other potential conflicts of interest. This manuscript does not represent the views of the United States government, the US NIH, or the Fogarty International Center.

Author contributions

JT, RS, and SV developed the initial idea for the manuscript. SD, UN, CO, KC, RS, and SV led small group discussions on this topic. JT developed the figure and table. JT wrote the first draft of the manuscript. CM contributed to the section on early planning. JI and OE provided LMIC examples and citations. All authors (JT, SD, UN, CO, OE, JI, KC, CM, RC, SV) contributed to the writing of the manuscript. All authors (JT, SD, UN, CO, OE, JI, KC, CM, RC, SV) read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the AHISA group for the helpful discussions on sustainability at the joint PATC3H/AHISA meeting in Lusaka, Zambia in April 2023. Special thanks to Kenny Kuti, Mogomotsi Matshaba, Chelsea Mazonde, and Sarah Owino for leading discussions on sustainability. Thanks to Nalini Anand and Audrey Pettifor for helpful comments on a previous version of this manuscript.

References

1 Fauci AS, Eisinger RW. PEPFAR – 15 years and counting the lives saved. N Engl J Med 2018; 378(4): 314-316.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

2 Moore JE, Mascarenhas A, Bain J, Straus SE. Developing a comprehensive definition of sustainability. Implement Sci 2017; 12(1): 110.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

3 Shediac-Rizkallah MC, Bone LR. Planning for the sustainability of community-based health programs: conceptual frameworks and future directions for research, practice and policy. Health Educ Res 1998; 13(1): 87-108.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

4 Asada Y, Lin S, Siegel L, Kong A. Facilitators and barriers to implementation and sustainability of nutrition and physical activity interventions in early childcare settings: a systematic review. Prev Sci 2023; 24(1): 64-83.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

5 Nkengasong J, Zaidi I, Katz IT. PEPFAR at 20-Looking Back and Looking Ahead. JAMA 2023; 330(3): 219-220.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

7 Flynn BS. Measuring community leaders’ perceived ownership of health education programs: initial tests of reliability and validity. Health Educ Res 1995; 10(1): 27-36.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

8 Rifkin SB. Lessons from community participation in health programmes: a review of the post Alma-Ata experience. Int Health 2009; 1(1): 31-36.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

9 Tahlil KM, Rachal L, Gbajabiamila T, Nwaozuru U, Obiezu-Umeh C, Hlatshwako T, et al. Assessing Engagement of Adolescents and Young Adults (AYA) in HIV research: a multi-method analysis of a crowdsourcing open call and typology of AYA engagement in Sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS Behav 2023; 27: 116-127.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

11 Wang C, Han L, Stein G, Day S, Bien-Gund C, Mathews A, et al. Crowdsourcing in health and medical research: a systematic review. Infect Dis Poverty 2020; 9(1): 8.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

12 Luke DA, Calhoun A, Robichaux CB, Elliott MB, Moreland-Russell S. The program sustainability assessment tool: a new instrument for public health programs. Prev Chronic Dis 2014; 11: 130184.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

13 Shelton RC, Cooper BR, Stirman SW. The sustainability of evidence-based interventions and practices in public health and health care. Annu Rev Public Health 2018; 39(1): 55-76.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

14 Chambers DA, Glasgow RE, Stange KC. The dynamic sustainability framework: addressing the paradox of sustainment amid ongoing change. Implement Sci 2013; 8(1): 117.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

15 Tang W, Wu D, Yang F, Wang C, Gong W, Gray K, et al. How kindness can be contagious in healthcare. Nat Med 2021; 27(7): 1142-1144.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

16 Kpokiri E, Sri-Pathmanathan C, Navaid S, Shrestha P, Jackson D, Labarda M, et al. Public engagement and crowdfunding for health research: a global qualitative evidence synthesis on crowdfunding and a TDR pilot. Available at https://osf.io/rq8h6

17 Haws J, Bakamjian L, Williams T, Lassner KJ. Impact of sustainability policies on sterilization services in Latin America. Stud Fam Plann 1992; 23(2): 85-96.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

18 Srinivas ML, Ritchwood TD, Zhang TP, Li J, Tucker JD.. Social innovation in sexual health: a scoping review towards ending the HIV epidemic. Sex Health 2021; 18(1): 5-12.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

19 Kuruvilla S, Hinton R, Boerma T, Bunney R, Casamitjana N, Cortez R, et al. Business not as usual: how multisectoral collaboration can promote transformative change for health and sustainable development. BMJ 2018; 363: k4771.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

20 Strasser S, Stauber C, Shrivastava R, Riley P, O’Quin K. Collective insights of public-private partnership impacts and sustainability: a qualitative analysis. PLoS ONE 2021; 16(7): e0254495.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

21 Halpaap BM, Tucker JD, Mathanga D, Juban N, Awor P, Saravia NG, et al. Social innovation in global health: sparking location action. Lancet Glob Health 2020; 8(5): e633-e634.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

22 Golin R, Godfrey C, Firth J, Lee L, Minior T, Phelps BR, et al. PEPFAR’s response to the convergence of the HIV and COVID-19 pandemics in Sub-Saharan Africa. J Int AIDS Soc 2020; 23(8): e25587.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

23 Ratevosian J. PEPFAR HIV program gets yearlong lifeline: what’s next? 2024. Available at https://www.thinkglobalhealth.org/article/pepfar-hiv-program-gets-yearlong-lifeline-whats-next

24 Iwelunmor J, Tucker JD, Ezechi O, Nwaozuru U, Obiezu-Umeh C, Gbaja-Biamila T, et al. Sustaining HIV research in resource-limited settings using PLAN (people, learning, adapting, nurturing): evidence from the 4 youth by youth project in Nigeria. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2023; 20(2): 111-120.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |