Chlamydia and gonorrhoea testing and positivity within an urban Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Community Controlled Health Service 2016–2021

Condy Canuto A * , Jon Willis B , Joseph Debattista C , Judith A. Dean

A * , Jon Willis B , Joseph Debattista C , Judith A. Dean  D and James Ward D

D and James Ward D

A

B

C

D

Abstract

This study describes chlamydia and gonorrhoea testing, positivity, treatment, and retesting among individuals aged ≥15 years attending an urban Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Service during the period 2016–2021.

Utilising routinely collected clinical data from the ATLAS program (a national sentinel surveillance network), a retrospective time series analysis was performed. The study assessed testing rates, positivity, treatment efficacy, retesting and trends over time within an urban Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Service.

Testing rates for chlamydia and gonorrhoea varied between 10 and 30% over the study period, and were higher among clients aged 15–29 years and among females. Positivity rates for both infections varied by age, with clients aged 15–24 years having higher positivity than older clients. Gonorrhoea positivity rates decreased after 2016. Treatment and retesting practices also showed sex disparities, with men having a slightly higher treatment rate within 7 days, whereas females had significantly higher retesting rates within 2–4 months, indicating differences in follow-up care between sexes.

The study emphasises the need for clinical and public health interventions within urban Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations to further reduce chlamydia and gonorrhoea. Prioritising improved access to testing, timely treatment and consistent retesting can significantly contribute to lowering STI prevalence and enhancing sexual health outcomes in these communities.

Keywords: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Service, epidemiology, Indigenous health, sexual health, sexually transmissible infections, STI screening, urban.

Introduction

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are the most frequently reported notifiable condition in Australia, with the number of reported cases continuing to rise.1 Over the past decade between 2013 and 2022, Australia has witnessed an upsurge in STI rates, including a 12% increase in chlamydia infections and a doubling of gonorrhoea cases since 2013.2 Cases of infectious syphilis in Australia more than tripled from 7.6 per 100,000 in 2013 to 24.3 per 100,000 in 2022. Congenital syphilis cases also rose significantly, with 83 cases reported between 2013 and 2022, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples experiencing rates 14 times higher than non-Indigenous people in 2022.2,3 These trends have sparked considerable public health concern, especially as the COVID-19 pandemic has led to reduced rates of STI testing.4–6

The asymptomatic nature of chlamydia and gonorrhoea infections can result in undiagnosed or inadequately treated infections.7 This can increase the complications of sequelae, such as pelvic inflammatory disease, ectopic pregnancy, greater vulnerability to HIV and infertility.8 Australian clinical guidelines recommend STI testing for asymptomatic people who request it, are at increased risk, have known exposure or recent history of STIs, or belong to priority subpopulations.9 Targeted screening can help reduce STI prevalence while also reducing negative sequelae and improving the cost-effectiveness of screening.10 Providing timely treatment and retesting for STIs among clients are also recommended within clinical guidelines, and deemed important components of STI control.11

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples face disproportionately high rates of STIs compared with non-Indigenous Australians.12,13 In 2022, the notification rate for chlamydia among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples was 814.1 per 100,000, more than twice the rate among non-Indigenous people, which was 374.9 per 100,000. Similarly, the notification rate for gonorrhoea was 547.1 per 100,000 among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, which is more than five times higher than the rate for non-Indigenous people at 108.3 per 100,000. This disparity is particularly notable among young individuals aged 15–24 years, where notification rates for both chlamydia and gonorrhoea are highest.2,14 The increased prevalence of STIs within Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples highlights the need for targeted public health interventions, and the importance of understanding the unique cultural, social and economic factors contributing to these disparities.

The management of chlamydia and gonorrhoea, and other STIs has been a focus in remote Aboriginal communities, where diagnosis rates are approximately five to 30 times higher than non-Indigenous populations.15 Until recently, most sexual health research targeting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples has predominantly focused on those living in remote and rural communities.16,17 In these areas, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are more susceptible to acquiring STIs, compared with their non-Indigenous counterparts of the same age, not only due to high community prevalences, but also because of several barriers.18–20 These include clinicians prioritising other urgent health concerns,21 high turnover of clinical staff,22 unfamiliarity with STI protocols,21 unwelcoming clinical settings for discussing sensitive topics and challenges related to clinician gender.21 Additionally, lower health literacy about STIs in remote communities affects engagement with health services.23 However, it is important to note that the majority of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples (84.7%) reside in non-remote areas of Australia, including 41% in major cities and the remainder in regional areas.24 To date, there have been limited investigations of chlamydia and gonorrhoea in urban Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.25

In Australia, the majority of STI testing and diagnosis is conducted in primary healthcare clinics.10 Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services (ACCHS) are recognised as ideal primary healthcare services for leading interventions aimed at preventing and controlling STIs among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples due to their culturally tailored, community-focused healthcare approach.26,27 As the predominant primary healthcare provider for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia, these services are community-governed and led,28 and therefore, the most responsive to local issues. They are preferred by communities for their consultative care model that is supported by primary healthcare professionals within the ACCHS.29

Testing rates within ACCHSs have been previously reported as higher than those occurring in mainstream general practice clinics, regardless of whether the patients were Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples or not.30 This significant difference highlights the importance of ACCHSs in providing more accessible and comprehensive testing services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients. Additionally, the inclusion of STI testing in routine health care within the ACCHS is achieved through the Medicare Benefits Schedule item number 715. This approach is seen as an optimal strategy to ensure the consistent and comprehensive provision of STI testing within ACCHS settings.31

Gaining insight into the epidemiology of chlamydia and gonorrhoea within urban settings is crucial for guiding testing protocols, and broader clinical policy and guidelines. Therefore, the aim of this study was to describe the testing, positivity, retesting and treatment patterns for chlamydia and gonorrhoea among clients aged ≥15 years who attended an urban ACCHS during the period 2016–2021.

Methods

This study was a retrospective time series analysis of clinical data obtained from electronic medical records from an urban ACCHS. Located in Brisbane, South East Queensland, Australia, the participating ACCHS has been in operation for >50 years, and is a well-established healthcare provider for urban Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in this region. This study utilised data routinely collected during clinical consultations involving patients aged ≥15 years from 1 January 2016 to 31 December 2021. These data were extracted from MMeX, the electronic medical records system within the ACCHS, via the ATLAS network,29 a national sentinel surveillance network that the ACCHS is a contributing site, using the GRHANITE program (Health and Biomedical Informatics Centre, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Vic., Australia).32 The extraction process involved de-identifying clients’ demographic information including sex, age at the time of consultation, Indigenous status and consultation date. Additionally, detailed records regarding chlamydia and gonorrhoea testing, including test results, treatment dates, and retesting data for clients who tested positive for chlamydia and gonorrhoea, were systematically retrieved.

In this study, chlamydia and gonorrhoea testing rates were reported together because of the widespread adoption of a duplex test in Australian laboratories in 2012.33 This duplex test combines both chlamydia and gonorrhoea testing, and when one of the tests is requested, both tests are automatically conducted at the laboratory. Data were extracted only for medical consultations occurring with doctors, nurses or Aboriginal health practitioners to provide a more precise denominator. Consultations with allied health professionals, mental health workers and dental consultations were excluded, because STI testing does not normally occur within these consultations.

Statistical analysis

Both regular and visiting clients of the service were included in the analysis. Testing rates were calculated as any client aged ≥15 years with two major categories, those aged 15–29 years and those aged ≥30 years. This approach allowed us to identify key differences in STI testing and positivity rates within each age group. The younger age group is the most at risk of STI acquisition,34 and is highlighted as a priority population in policy and guidelines.2 The age categorisation used in this study reflects the national STI testing recommendations by age, so they can be used as a measure of how well the ACCHS is performing against these guidelines. STI testing was calculated as the proportion of all clients in each age group and by sex who had a chlamydia and gonorrhoea test at any point during each calendar year. Test positivity was calculated as the proportion of all tests with a positive chlamydia and or gonorrhoea result each year. Treatment within 7 days was calculated as the proportion of all clients with either a positive chlamydia or gonorrhoea result who were prescribed recommended treatment after the pathology result was recorded in the electronic medical records. As timely treatment is a key strategy in STI control, 7 days was chosen as an arbitrary number enabling sufficient time to recall people for appointments to administer treatment within an urban context. Retesting was calculated for all clients who had a positive chlamydia or gonorrhoea result at their first test. A second test was recorded anywhere between 8 and 16 weeks after the initial positive result. Repeat positivity was calculated as positivity on the follow-up test for all positive clients conducted in the period 2–4 months post first positive result. Time series analysis was conducted to assess trends in testing, positivity, treatment and retesting. Chi-squared tests for trends were conducted to analyse changes in testing rates for chlamydia and gonorrhoea over the study period (2016–2021), with statistical significance defined as a P-value of <0.05. These tests were applied separately for each age group (15–29 years and ≥30 years) and by sex to evaluate whether there were statistically significant linear trends in the proportions of individuals tested over time. Finally, and for the purpose of this paper, we constructed a chlamydia testing and care cascade for the ACCHS to be used in STI control measures and quality improvement initiatives within the ACCHS. All data were analysed using SPSS 28 statistical software (IBM® SPSS Statistics) and Microsoft Excel.

Results

A total of 18,965 clients (aged ≥15 years) attended the ACCHS during the study period (2016–2021). The median age was 32 years, and the mean age was 35 years. Of these clients, 56% (n = 10,594) were female and 44% (n = 8,341) were male. In terms of Indigenous status, the majority (70%, n = 13,088) identified as Aboriginal, 5.8% (n = 1,107) identified as both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, and 5.6% (n = 1,053) identified as Torres Strait Islander.

Testing rates

Testing rates for chlamydia and gonorrhoea between 2016 and 2021 were notably higher for individuals aged 15–29 years (25%) compared with those aged ≥30 years (17%; P < 0.001). Table 1 shows the proportion of clients tested for chlamydia and gonorrhoea by sex and age group for the 15–29 years and ≥30 years cohort. There was a gradual decline in testing over the study period following an earlier peak in 2018. This decline occurred across both age groups; however, the 15–29-year-olds were consistently tested at a higher rate than those aged ≥30 years.

| Male | Female | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 15–29 years | ≥30 years | 15–29 years | ≥30 years | 15–29 years | ≥30 years | |

| 2016 | 21% (174/833) | 14% (221/1544) | 33% (410/1253) | 20% (409/2026) | 28% (584/2086) | 18% (630/3570) | |

| 2017 | 22% (224/1010) | 15% (281/1837) | 29% (457/1565) | 17% (400/2358) | 26% (681/2575) | 16% (681/4195) | |

| 2018 | 30% (291/977) | 22% (418/1925) | 30% (492/1614) | 21% (528/2528) | 30% (783/2591) | 21% (946/4453) | |

| 2019 | 23% (258/1137) | 20% (412/2096) | 28% (499/1755) | 19% (516/2715) | 26% (757/2892) | 19% (928/4811) | |

| 2020 | 19% (215/1129) | 18% (417/2307) | 27% (493/1847) | 16% (486/2952) | 24% (708/2976) | 17% (903/5259) | |

| 2021 | 12% (141/1179) | 9% (231/2465) | 19% (373/1930) | 11% (333/3117) | 17% (514/3109) | 10% (564/5582) | |

Analysis of chlamydia testing rates from 2016 to 2021 for males and females across different age groups (15–29 years and ≥30 years) showed no statistically significant trend over time. A Chi-squared test for trend was performed to detect any significant linear trends in testing rates for both age groups. For the 15–29 years age group, the test did not indicate a significant trend (Chi-squared = 4.46, P = 0.486). Similarly, for the ≥30 years age group, there was no significant trend detected (Chi-squared = 4.22, P = 0.518).

For those aged 15–29 years, the overall testing rate for chlamydia and gonorrhoea was higher for females (27%) compared with males (21%; P = 0.0001) over the study period. For those aged >30 years, such a pattern was not observed, with testing rates for chlamydia and gonorrhoea similar across both sexes and at a lower lever compared with the younger cohort (Table 1).

Chlamydia positivity rates

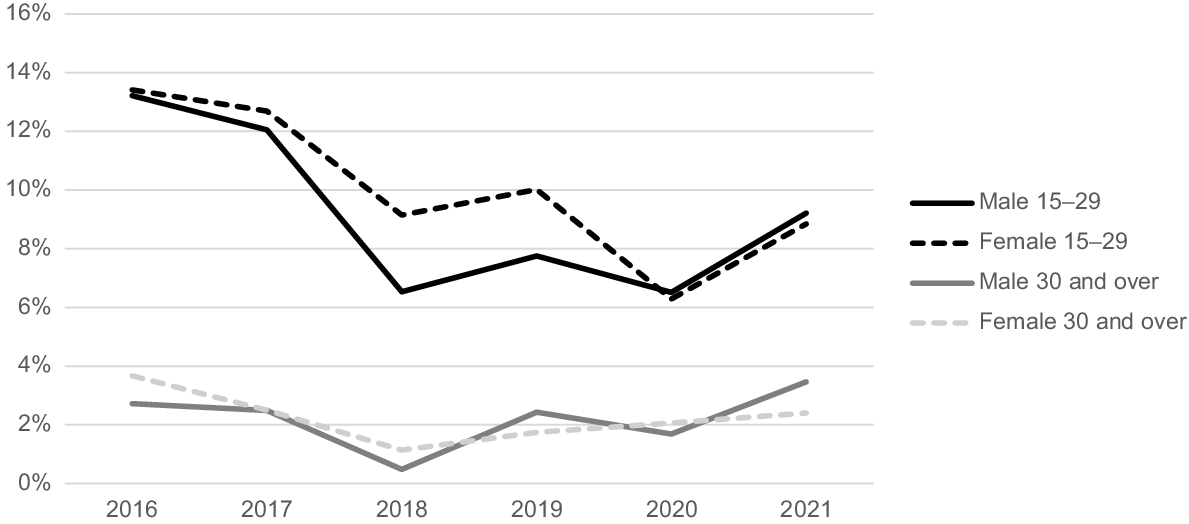

Fig. 1 presents chlamydia positivity rates at an urban ACCHS from 2016 to 2021. Males and females aged 15–29 years had similar chlamydia positivity rates, ranging from 9 to 13% throughout the study period. In contrast, those aged ≥30 years had lower positivity rates, ranging from 2 to 4%.

Gonorrhoea positivity rates

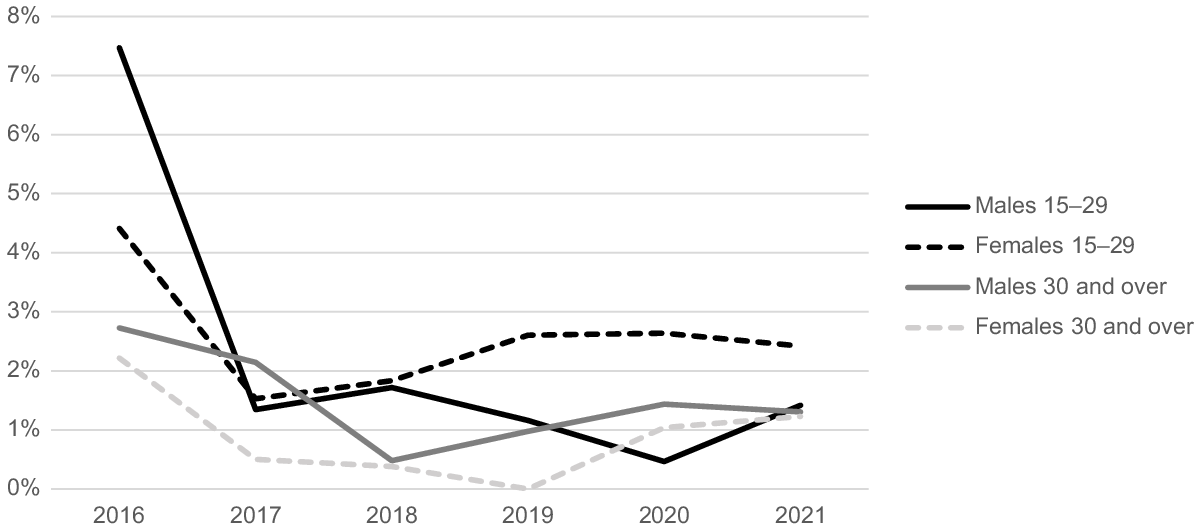

The gonorrhoea positivity rates show distinct trends for different age groups in males and females. For males, the highest diagnosis rate of gonorrhoea was recorded in 2016 for both age groups, 15–29 years and ≥30 years. In this year, the positivity rate was 7% for the younger age group and 3% for the older group (Fig. 2). In 2017, there was a decrease in these rates to 1% for the 15–29 years age group and 2% for those aged ≥30 years. These rates remained stable through to 2021. For females, the highest gonorrhoea positivity rate was in 2016 at 4% for the 15–29 years age group and 2% for the ≥30 years age group. From 2017 onwards, the positivity rate for the 15–29 years age group remained between 2 and 3%.

Chlamydia diagnosis and care cascade

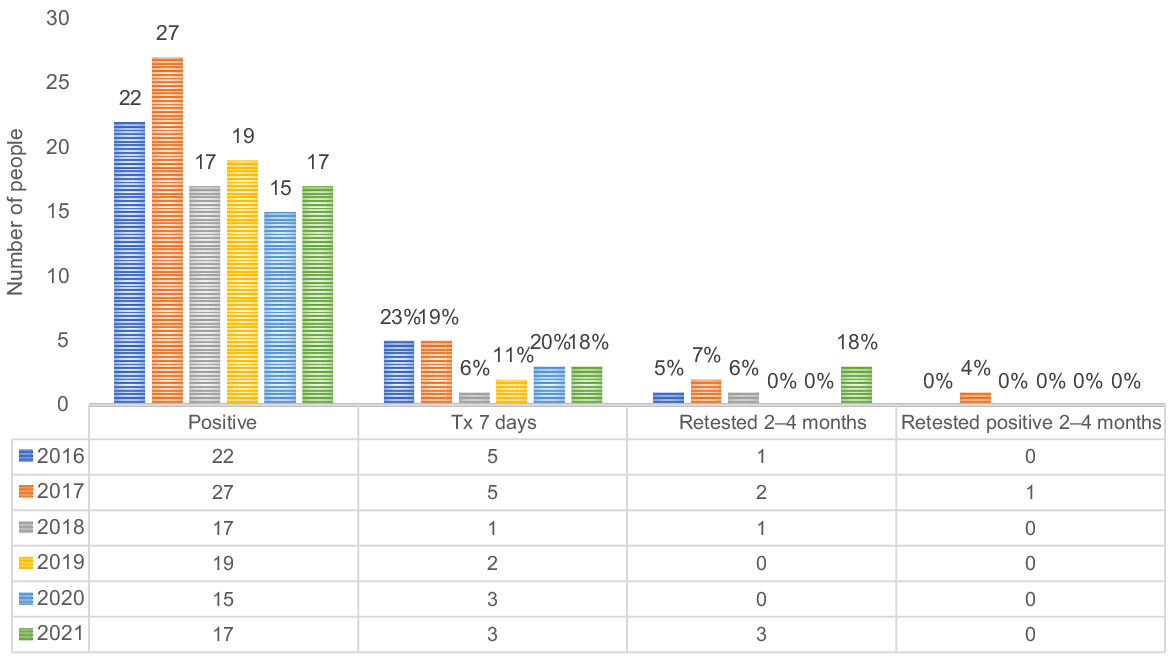

Fig. 3 shows the chlamydia diagnosis and care cascade for females aged 15–29 years from 2016 to 2021. The proportion of females treated for chlamydia within 7 days increased from 6% in 2016 to 17% in 2017, indicating an improvement in timely treatment. However, the practice of retesting within 2–4 months after a positive diagnosis remained low, fluctuating between 2 and 6% throughout the study period.

The chlamydia diagnosis and care cascade for females aged 15–29 years, urban Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Service 2016–2021.

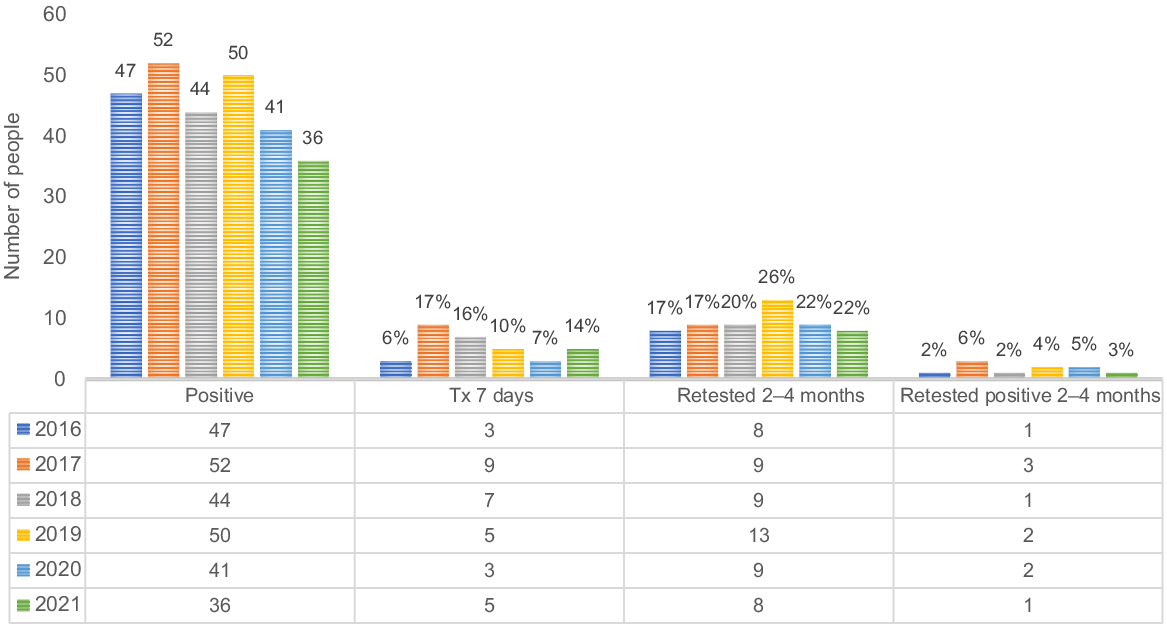

Fig. 4 shows the chlamydia diagnosis and care cascade for males aged 15–29 years from 2016 to 2021. The proportion of males treated within 7 days of a positive chlamydia diagnosis varied around the study period, ranging from a peak of 22% in 2016 to a low of 6% in 2018. Retesting within 2–4 months after a positive diagnosis peaked at 18% in 2021, with no retesting in 2019 and 2020. Throughout the study period, the percentage of males who retested positive within 2–4 months remained very low, with most years recording 0%, except for 2017, which had a rate of 4%.

Treatment rates within 7 days

Over the study period from 2016 to 2021, the average treatment rate within 7 days for males was 16%, compared with 12% for females.

Retested in 2–4 months

Both males and females showed variability in retesting rates over the study period. Nevertheless, females consistently had higher retesting rates within 2–4 months after an initial positive diagnosis compared with males throughout the 6-year period. The overall difference in chlamydia retesting rates between males (6%) and females (21%) was statistically significant (P = 0.00055), indicating systematic disparities in follow-up testing practices between the sexes.

Retested positive in 2–4 months

Over the study period between 2016 and 2021, overall results suggest that females (4%) in the 15–29 years age group are more likely to retest positive for chlamydia in the 2–4-month window after an initial positive test compared with males (1%) in the same age group. However, given that the numbers are very low, it would be difficult to draw any significant conclusion from the data.

Discussion

This research is one of the few studies to explore STI testing and positivity rates within an urban ACCHS. Testing among those aged 15–29 years was suboptimal when compared with the national clinical guideline’s recommendation for annual testing for all young people in this age range.35 With approximately 20–30% tested annually and throughout the study period, these results compare favourably with other ACCHS, as indicated in other studies that found similar STI testing rates.36 However, this still highlights the need to expand opportunities for STI testing to ensure compliance with the ‘Australian Sexually Transmitted Infection (STI) Management Guidelines for Use in Primary Care’.9

Notably, low treatment rates within 7 days for chlamydia and gonorrhoea were observed in this study. Similar challenges have been identified in previous research, where urban clinics showed a mean time-to-treatment of 8 days.37 Delays in urban areas were primarily due to the time taken for result reporting and initiating treatment.37 Timely treatment of STIs is important for controlling the spread and improving health outcomes among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia. Studies have shown that point-of-care diagnostic tests, conducted at the time of patient visits, can improve the treatment and management of STIs.38 The ATLAS project has established a sentinel surveillance network that collects detailed data on STI testing, treatment and management across ACCHS, contributing significantly to improved clinical care and guidelines.29 Moreover, the Young Deadly Free project has been successful in increasing the uptake of STI testing and treatment through culturally appropriate peer education, addressing the high rates of STIs in remote Aboriginal communities.39 The utilisation of point-of-care testing, as demonstrated in the TTANGO trial,40,41 could significantly reduce the time to treatment, particularly in urban settings similar to our study environment. This approach could provide a targeted intervention to address the specific delays observed. Therefore, the availability of rapid diagnostic tests could allow for quicker decision-making and appropriate treatment, improving patient outcomes.

Furthermore, the implementation of clinician education, patient advice and SMS/text reminders has been demonstrated effective in improving retesting rates, which could be adapted to enhance treatment uptake as well.42 These findings suggest that adopting a more systematic approach to treatment and follow up, leveraging modern testing technologies, and enhancing communication strategies could ameliorate the low treatment rates observed in our study.

The findings from the chlamydia diagnosis and care cascade for young adults aged 15–29 years over the period of 2016–2021 provided insights into the clinical management of STIs. The data, while illustrating disparities between the sexes in treatment and retesting rates, also offers a basis for constructive discussion on enhancing STI management practices. It is worth noting that over the study period, males were treated earlier, with higher average treatment rates within 7 days compared with females, although further exploration is needed to better understand this difference within this study setting. The higher average treatment rates within 7 days for males compared with females could reflect an aspect of the ACCHS ability to engage young men in STI treatment, considering the common narrative around the difficulties in engaging men in health-seeking behaviours.43

Nevertheless, although more men than women were treated within 7 days, more women were retested then men. It is important to note that STI morbidity is higher in women, highlighting the need for improved treatment strategies to prevent these conditions.44 These strategies can include better diagnostics, treatment and prevention approaches to reduce the morbidity associated with STIs in women.44 Telehealth consultations are also an effective approach for delivering STI care, improving access to services and optimising treatment delivery.45 However, this does not overshadow the fact that overall treatment rates could be improved for both sexes.

The significantly higher retesting rates among females compared with males could indicate a greater awareness and concern that females have about the risks of STIs.46 It may also reflect the higher rate of GP attendance by females and, therefore, more opportunities for retesting. However, the disparity also highlights the need for innovative approaches to encourage young men to participate in follow-up care, as well as just getting them ito test in the first place, as suggested earlier.47

The variability in retesting rates and the low percentage of individuals retesting positive for chlamydia within the 2–4-month window post-initial diagnosis suggest a mixed outcome. On one hand, the low retest positivity could be seen as an indicator of successful treatment and possibly effective initial health interventions. On the other hand, the low retesting rates, especially among males, might reflect underlying issues, such as loss to care, which can be attributed to a multitude of factors, including failures in communication, difficulties with transportation and obstacles in making appointments. In addressing these challenges, it is crucial to adopt a strengths-based approach that builds on the existing successful strategies, such as Aboriginal Health Worker-led initiatives,48 point-of-care testing49 and nurse-led interventions,50 while also tackling the barriers that lead to loss to care and poor follow up.

The study’s key strength was its use of a comprehensive, 6-year dataset covering the entire population, allowing for a detailed representation of the population trends within urban ACCHS. The results from this study can provide a baseline for future studies on urban Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples populations to compare against.

Although our study provides valuable insights, several limitations were identified. Challenges arose due to our inability to determine whether participants were locals or visitors, and may have skewed our understanding of repeat testing frequencies. We also faced limitations in assessing the exact timing of tests and the reasons behind each test, whether for symptoms or routine screening. Despite these challenges, the study highlights the complexities of healthcare research and the importance of considering various influencing factors.

In moving forward, a range of strategies aimed at boosting STI testing rates within ACCHSs includes providing financial incentives to physicians, implementing health promotion programs that specifically target young individuals to enhance patient demand for testing and ensuring the availability of high-quality data to monitor clinic performance.14 Efficient collection and analysis of testing data that can be returned to clinicians for review and benchmarking against commonly agreed standards creates a quality feedback loop that increases awareness and motivation for testing. Additionally, the implementation of a quality improvement program has seen a threefold increase in chlamydia and gonorrhoea testing rates among young individuals.14 Specialised training of staff to assess and recognise behavioural and social risks, and comfortably engage in conversations around STI testing will also be critical strategies to improve testing rates.51 Further structural changes in clinics, such as waiting areas and toilet facilities within easy and discrete access of clinic rooms, may facilitate easier testing for clients.52 As females were consistently tested more than males throughout the study period, as others have demonstrated,20,53 a priority on programs and initiatives focused on increasing testing rates among males in this age group should also be considered. In addition to the already established program of free annual health checks offered to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples at an ACCHS,54 increasing opportunistic testing when a young person presents at an ACCHS or other healthcare service would be beneficial.55 Integrating electronic prompts and automated pathology test sets have been shown to significantly increase STI testing rates, demonstrating a successful model that could be implemented more broadly.56 These recommendations are aligned with the updated Australian STI management guidelines, which underscore the integration of STI testing into routine health checks and opportunistic testing.9

Conclusion

The high prevalence of STIs among young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples highlights the urgent need for comprehensive sexual health literacy, and effective strategies for STI prevention and control. Successful public health initiatives address both the biological and behavioural determinants of STIs, incorporating clinical management of infections, addressing biological cofactors affecting susceptibility and implementing health promotion initiatives to modify behaviours that facilitate transmission.57–59 This requires a coordinated approach involving various interventions, such as opportunistic and population screening, individual testing and treatment, contact tracing, recall testing, community education, health promotion, and individual and partner counselling, engaging individuals, their sexual networks, their community and society as a whole.

Data availability

The data that support this study were obtained from the ALTAS Project by permission/licence. Data will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author with permission from both the ACCHS involved and the ALTAS Project.

References

1 Thng CCM. A review of sexually transmitted infections in Australia – considerations in 2018. Acad Forensic Pathol 2018; 8(4): 938-946.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

3 Borg SA, Tenneti N, Lee A, Drewett GP, Ivan M, Giles ML. The reemergence of syphilis among females of reproductive age and congenital syphilis in Victoria, Australia, 2010 to 2020: A Public Health Priority. Sex Transm Dis 2023; 50(8): 479-484.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

4 Thng C, Hughes I, Poulton G, O’Sullivan M. 18 months on: an interrupted time series analysis investigating the effect of COVID-19 on chlamydia and gonorrhoea testing and test positivity at the Gold Coast, Australia. Sex Health 2022; 19(2): 127-131.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

5 Chow EPF, Hocking JS, Ong JJ, Phillips TR, Fairley CK. Sexually transmitted infection diagnoses and access to a sexual health service before and after the national lockdown for COVID-19 in Melbourne, Australia. Open Forum Infect Dis 2020; 8(1): ofaa536.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

6 Dalmau M, Ware R, Field E, Sanguineti E, Si D, Lambert S. Effect of COVID-19 pandemic restrictions on chlamydia and gonorrhoea notifications and testing in Queensland, Australia: an interrupted time series analysis. Sex Transm Infect 2023; 99(7): 447-454.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

7 Silver BJ, Knox J, Smith KS, Ward JS, Boyle J, Guy RJ, et al. Frequent occurrence of undiagnosed pelvic inflammatory disease in remote communities of central Australia. Med J Aust 2012; 197(11–12): 647-651.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

8 Dombrowski JC. Chlamydia and gonorrhea. Ann Intern Med 2021; 174(10): ITC145-ITC160.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

9 Ong JJ, Bourne C, Dean JA, Ryder N, Cornelisse VJ, Murray S, et al. Australian sexually transmitted infection (STI) management guidelines for use in primary care 2022 update. Sex Health 2023; 20(1): 1-8.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

10 Chen MY, Donovan B. Genital chlamydia trachomatis infection in Australia: epidemiology and clinical implications. Sex Health 2004; 1(4): 189-196.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

11 Østergaard L, Andersen B, Møller JK, Olesen F. Home sampling versus conventional swab sampling for screening of chlamydia trachomatis in women: a cluster-randomized 1-year follow-up study. Clin Infect Dis 2000; 31(4): 951-957.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

12 Bell S, Ward J, Aggleton P, Murray W, Silver B, Lockyer A, et al. Young Aboriginal people’s sexual health risk reduction strategies: a qualitative study in remote Australia. Sex Health 2020; 17(4): 303-310.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

13 Ubrihien A, Gwynne K, Lewis DA. Barriers and enablers for young Aboriginal people in accessing public sexual health services: a mixed method systematic review. Int J STD AIDS 2022; 33(6): 559-569.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

14 Graham S, Guy RJ, Wand HC, Kaldor JM, Donovan B, Knox J, et al. A sexual health quality improvement program (SHIMMER) triples chlamydia and gonorrhoea testing rates among young people attending Aboriginal primary health care services in Australia. BMC Infect Dis 2015; 15: 370.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

15 Silver BJ, Guy RJ, Wand H, Ward J, Rumbold AR, Fairley CK, et al. Incidence of curable sexually transmissible infections among adolescents and young adults in remote Australian Aboriginal communities: analysis of longitudinal clinical service data. Sex Transm Infect 2015; 91(2): 135-141.

| Google Scholar |

16 Fagan P, McDonell P. Knowledge, attitudes and behaviours in relation to safe sex, sexually transmitted infections (STI) and HIV/AIDS among remote living north Queensland youth. Aust N Z J Publ Health 2010; 34: S52-S56.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

17 Kildea S, Bowden FJ. Reproductive health, infertility and sexually transmitted infections in Indigenous women in a remote community in the Northern Territory. Aust N Z J Publ Health 2000; 24(4): 382-386.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

19 Lafferty L, Smith K, Causer L, Andrewartha K, Whiley D, Badman SG, et al. Scaling up sexually transmissible infections point-of-care testing in remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities: healthcare workers’ perceptions of the barriers and facilitators. Implement Sci Commun 2021; 2(1): 127.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

20 Nattabi B, Matthews V, Bailie J, Rumbold A, Scrimgeour D, Schierhout G, et al. Wide variation in sexually transmitted infection testing and counselling at Aboriginal primary health care centres in Australia: analysis of longitudinal continuous quality improvement data. BMC Infect Dis 2017; 17(1): 148.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

21 Hengel B, Guy R, Garton L, Ward J, Rumbold A, Taylor-Thomson D, et al. Barriers and facilitators of sexually transmissible infection testing in remote Australian Aboriginal communities: results from the sexually transmitted infections in remote communities, improved and enhanced primary health care (STRIVE) study. Sex Health 2014; 12(1): 4-12.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

22 Russell DJ, Zhao Y, Guthridge S, Ramjan M, Jones MP, Humphreys JS, et al. Patterns of resident health workforce turnover and retention in remote communities of the Northern Territory of Australia, 2013–2015. Hum Resour Health 2017; 15(1): 52.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

23 Keleher H, Hagger V. Health literacy in primary health care. Aust J Primary Health 2007; 13(2): 24-30.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

24 Australian Bureau of Statistics. Census of population and housing – counts of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. ABS; 2021. Available at https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-peoples/census-population-and-housing-counts-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-australians/2021

25 Harrod ME, Couzos S, Ward J, Saunders M, Donovan B, Hammond B, et al. Gonorrhoea testing and positivity in non-remote Aboriginal community controlled health services. Sex Health 2017; 14(4): 320-324.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

26 Durey A. Reducing racism in Aboriginal health care in Australia: where does cultural education fit? Aust N Z J Publ Health 2010; 34: S87-S92.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

27 Panaretto KS, Wenitong M, Button S, Ring IT. Aboriginal community controlled health services: leading the way in primary care. Med J Aust 2014; 200(11): 649-652.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

28 Pearson O, Schwartzkopff K, Dawson A, Hagger C, Karagi A, Davy C, et al. Aboriginal community controlled health organisations address health equity through action on the social determinants of health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia. BMC Publ Health 2020; 20(1): 1859.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

29 Bradley C, Hengel B, Crawford K, Elliott S, Donovan B, Mak DB, et al. Establishment of a sentinel surveillance network for sexually transmissible infections and blood borne viruses in Aboriginal primary care services across Australia: the ATLAS project. BMC Health Serv Res 2020; 20(1): 769.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

30 Ward J, Goller J, Ali H, Bowring A, Couzos S, Saunders M, et al. Chlamydia among Australian Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people attending sexual health services, general practices and Aboriginal community controlled health services. BMC Health Serv Res 2014; 14(1): 285.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

31 McCormack H, Guy R, Bourne C, Newman CE. Integrating testing for sexually transmissible infections into routine primary care for Aboriginal young people: a strengths-based qualitative analysis. Aust N Z J Publ Health 2022; 46(3): 370-376.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

32 Boyle D, Kong F. A systematic mechanism for the collection and interpretation of display format pathology test results from Australian primary care records. Electron J Health Informat 2011; 6(2): 18.

| Google Scholar |

33 Donovan B, Dimech W, Ali H, Guy R, Hellard M. Increased testing for Neisseria gonorrhoeae with duplex nucleic acid amplification tests in Australia: implications for surveillance. Sex Health 2015; 12(1): 48-50.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

34 Ward J, Wand H, Bryant J, Delaney-Thiele D, Worth H, Pitts M, et al. Prevalence and correlates of a diagnosis of sexually transmitted infection among young Aboriginal and Torres Strait islander people: a national survey. Sex Transm Dis 2016; 43(3): 177-84.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

36 Ward J, Bradley C, Donovan B, Hengel B, Elliott SR. A new national STI and BBV surveillance system for aboriginal community-controlled health services. Int J Popul Data Sci 2020; 5(5): Available at https://ijpds.org/article/view/1481.

| Google Scholar |

37 Foster R, Ali H, Crowley M, Dyer R, Grant K, Lenton J, et al. Does living outside of a major city impact on the timeliness of chlamydia treatment? A multicenter cross-sectional analysis. Sex Transm Dis 2016; 43(8): 506-512.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

38 Ward J, Guy R, Huang R-L, Knox J, Couzos S, Scrimgeour D, et al. Rapid point-of-care tests for HIV and sexually transmissible infection control in remote Australia: can they improve Aboriginal people’s and Torres Strait Islanders’ health? Sex Health 2012; 9(2): 109-112.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

39 D’Costa B, Lobo R, Thomas J, Ward JS. Evaluation of the young deadly free peer education training program: early results, methodological challenges, and learnings for future evaluations. Front Publ Health 2019; 7: 74.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

41 Guy RJ, Natoli L, Ward J, Causer L, Hengel B, Whiley D, et al. A randomised trial of point-of-care tests for chlamydia and gonorrhoea infections in remote Aboriginal communities: test, treat and go- the “TTANGO” trial protocol. BMC Infect Dis 2013; 13(1): 1-9.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

42 Rose SB, Garrett SM, Hutchings D, Lund K, Kennedy J, Pullon SRH. Clinician education, advice and SMS/text reminders improve test of reinfection rates following diagnosis of Chlamydia trachomatis or Neisseria gonorrhoeae: before and after study in primary care. BMJ Sex Reprod Health 2020; 46(1): 32-37.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

43 Canuto K, Brown A, Wittert G, Harfield S. Understanding the utilization of primary health care services by Indigenous men: a systematic review. BMC Publ Health 2018; 18(1): 1198.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

44 Unemo M, Bradshaw CS, Hocking JS, de Vries HJC, Francis SC, Mabey D, et al. Sexually transmitted infections: challenges ahead. Lancet Infect Dis 2017; 17(8): e235-e279.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

45 Pearson WS, Chan PA, Habel MA, Haderxhanaj LT, Hogben M, Aral SO. A description of telehealth use among sexually transmitted infection providers in the United States, 2021. Sex Transm Dis 2023; 50(8): 518-522.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

46 Andrea T, Stanzia M, Marvellous M, Albert M, Enock M. STIs and unplanned pregnancies risk perceptions among female students in tertiary institutions in Zimbabwe. Int J HIV AIDS Prev Educ Behav Sci 2021; 7(2): 66-74.

| Google Scholar |

48 Ward J, Guy RJ, Rumbold AR, McGregor S, Wand H, McManus H, et al. Strategies to improve control of sexually transmissible infections in remote Australian Aboriginal communities: a stepped-wedge, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet Glob Health 2019; 7(11): e1553-e1563.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

49 Causer L, Watchirs-Smith L, Saha A, Wand H, Smith K, Badman S, et al. P171 From trial to program: TTANGO2 scale-up and implementation sustains STI point-of-care testing in regional and remote Australian Aboriginal health services. Sex Transm Infect 2021; 97(Suppl 1): A102-A103.

| Google Scholar |

50 Rose SB, Garrett SM, Hutchings D, Lund K, Kennedy J, Pullon SRH. Addressing gaps in the management of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae in primary care: lessons learned in a pilot intervention study. Sex Transm Dis 2019; 46(7): 480-486.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

51 Lanier Y, Castellanos T, Barrow RY, Jordan WC, Caine V, Sutton MY. Brief sexual histories and routine HIV/STD testing by medical providers. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2014; 28(3): 113-120.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

52 Read PJ, Martin L, McNulty A. Would you self-collect swabs in a unisex toilet? Sex Health 2012; 9(4): 395-396.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

53 Hengel B, Ward J, Wand H, Rumbold A, Kaldor J, Guy R. P5.007 annual Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoea testing in an endemic setting: the role of client and health centre characteristics. Sex Transm Infect 2013; 89(Suppl 1): A336-A337.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

54 Spurling GKP, Hayman NE, Cooney AL. Adult health checks for Indigenous Australians: the first year’s experience from the Inala Indigenous Health Service. Med J Aust 2009; 190(10): 562-564.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

55 Pimenta JM, Catchpole M, Rogers PA, Perkins E, Jackson N, Carlisle C, et al. Opportunistic screening for genital chlamydial infection. I: acceptability of urine testing in primary and secondary healthcare settings. Sex Transm Infect 2003; 79(1): 16-21.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

56 McCormack H, Wand H, Newman CE, Bourne C, Kennedy C, Guy R. Exploring whether the electronic optimization of routine health assessments can increase testing for sexually transmitted infections and provider acceptability at an Aboriginal community controlled health service: mixed methods evaluation. JMIR Med Inform 2023; 11: e51387.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

57 Pavlin NL, Gunn JM, Parker R, Fairley CK, Hocking J. Implementing chlamydia screening: what do women think? a systematic review of the literature. BMC Publ Health 2006; 6: 221.

| Google Scholar |

58 Panaretto KS, Lee HM, Mitchell MR, Larkins SL, Manessis V, Buettner PG, et al. Prevalence of sexually transmitted infections in pregnant urban Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women in northern Australia. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2006; 46(3): 217-224.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

59 Miller GC, McDermott R, McCulloch B, Fairley C, Muller R. Predictors of the prevalence of bacterial STI among young disadvantaged indigenous people in north Queensland, Australia. Sex Transm Infect 2003; 79(4): 332-335.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |