Providing sexual health care for international students in Australia: a qualitative study of a general practice team approach

Sanjyot Vagholkar A B * , Janani Mahadeva A B , Yang Xiang C D , Jiadai Li E and Melissa Kang

A B * , Janani Mahadeva A B , Yang Xiang C D , Jiadai Li E and Melissa Kang  F

F

A

B

C

D

E

F

Abstract

Provision of culturally responsive sexual health care for international students is important, given the large numbers of international students in Australia and known lower levels of health literacy among this cohort. Team-based care in general practice has the potential to provide this care.

A qualitative study that developed and evaluated a team-based model of care for female, Mandarin-speaking, international students in a university-based general practice. The model involved patients attending a consultation with a Mandarin-speaking nurse with advanced skills in sexual health who provided education and preventive health advice, followed by a consultation with a GP. Evaluation of the model explored patient and healthcare worker experiences using a survey and a focus group of patients, and interviews with healthcare workers. Data were analysed using a general inductive approach.

The consultation model was evaluated with 12 patients and seven GPs. Five patients participated in a focus group following the consultation. Survey results showed high levels of patient satisfaction with the model. This was confirmed via the focus group findings. Healthcare workers found the model useful for providing sexual health care for this cohort of patients and were satisfied with the team approach to patient care.

A team-based approach to providing sexual health care for international students was satisfactory to patients, GPs and the practice nurse. The challenge is providing this type of model in Australian general practice under the current funding model.

Keywords: general practice, general practitioners, international students, Mandarin speakers, models of service delivery, practice nurse, reproductive health, sexual health, team-based care.

Introduction

International students have returned to Australia in large numbers following the restrictions of the COVID-19 pandemic, with 768,113 at October 2023.1 The largest proportion, ~22%, are from China.1 Living away from family and the societal expectations in their home country, many of these students have the opportunity to explore personal and sexual relationships with a new freedom. Students from countries such as China, which have a more conservative culture than Western countries in regard to intimate relationships, often have lower levels of sexual and reproductive health literacy.2–4 They may also find navigating the Australian healthcare system challenging, including limitations on care covered by health insurance providers.2–5 This can result in poorer health outcomes for students in regard to sexually transmitted infections, access to contraception and management of unplanned pregnancies.4,6,7

Various studies have highlighted the need for better sexual health education and access to appropriate services for this group of students.4,6,7 Part of the challenge is related to the language barriers that can arise, and providing care in their first language, which is Mandarin for most Chinese students, has the potential to address this.8 Previous Australian research highlighted the need for mainstream primary care to be the predominant provider of sexual health care.9 There is, therefore, a need to explore better ways of delivering care to this more vulnerable population of patients.

Team-based care in the primary care setting is increasingly seen as pivotal to providing optimal care for patients, and current reforms in primary health care in Australia are focusing on multidisciplinary care.10 Practice nurses (PN) are a vital part of delivering general practice services, and many of them have advanced skills in different areas, including sexual health care. Developing models of care that can utilise these skills may be a way to address the sexual health care needs of international students. This study aimed to develop and evaluate a team-based model of care in general practice that could provide sexual health services to international students in their native language of Mandarin.

Methods

This qualitative study was reported according to the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research guidelines (see Supplementary material Table S1).

Theoretical framework

The study involved the development and evaluation of a model of care for sexual and reproductive healthcare services for female, Mandarin-speaking, international university students. A qualitative methodology was chosen to understand the experiences of patients and healthcare workers (HCW) involved. The study had an inductive research approach.

An inductive approach is commonly identified with a constructivist paradigm. Although this study utilised an inductive approach, its theoretical framework was aligned with a pragmatic approach and multiple methods (patient evaluation survey and focus group (FG), and HCW interviews) were utilised to collect data.11,12 The survey data were collected for descriptive purposes. There was no quantitative data analysis.

Consultation model

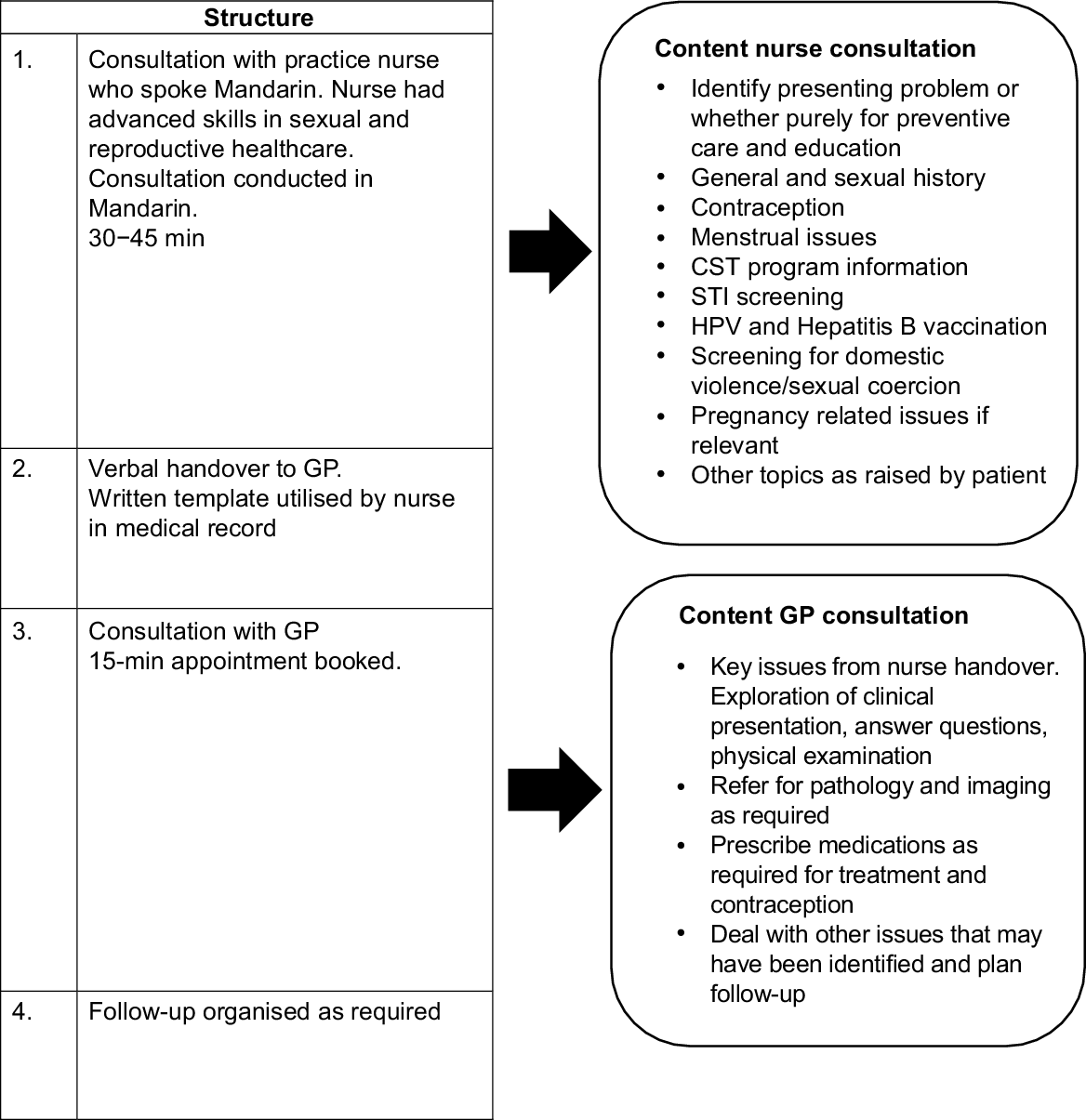

The team developed a consultation model (Fig. 1) based on a literature review, interviews with clinicians at Australian university health services and the researchers’ clinical experience. Interviews with HCWs at other university-based health services provided insights about current models of care they utilised and their views on team-based care.13 Prior to the study, MQ Health GP clinic had already been using the PN with advanced skills to work with students, and provide sexual and reproductive health care, and this provided useful information about what could work for both patients and HCWs in the clinic. All three sources of information, therefore, fed into the final model.

Consultation model. GP, general practitioner; CST, cervical screening test; STI, sexually transmitted infection; HPV, human papilloma virus.

The key feature of the model was the utilisation of a team-based approach to providing care. Patients were seen by a Mandarin-speaking PN originally from China, who had advanced skills in sexual and reproductive health care, followed by a consultation with the general practitioner (GP). Tasks to be completed were clearly distributed between the GP and the PN.

Recruitment

The study was conducted at MQ Health General Practice. This is a community and university general practice clinic that services students at Macquarie University in Sydney, Australia.

Inclusion criteria were women, aged ≥18 years, university students or recent graduates (≤2 years), first language Mandarin, and had basic comprehension of spoken and written English. Patients were recruited via multiple means: posters in the MQ Health General Practice clinic (English and Chinese), SMS messaging via practice software (English), electronic communication via the university international student services network (English) and via social media on WeChat (Chinese). Patients who expressed an interest were contacted by the Project Officer (PO), who spoke Mandarin, and provided with further information. Patients who chose to participate may have had a sexual health symptom they sought advice about, or may have purely been interested in preventive care and education. Written informed consent was obtained from participants. Participants were billed in the usual manner for the GP consultation, with a rebate from their insurer and a gap payment (A$20) charged by the clinic for a 15-min consultation. There was no charge for the PN consultation in the study.

The study planned to implement the intervention with 30 patients; however, the time period coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic, when many international students returned to their home country, and their return was delayed by travel restrictions in Australia. This impacted recruitment numbers.

GPs were recruited from staff working at MQ Health General Practice. All GPs (13) working at the practice were informed of the study at a regular practice meeting. Subsequently, GPs (7) whose work sessions coincided with the PN in the study and were likely to have appointment availability were given more detailed information about the study at a lunchtime meeting, with an opportunity to ask questions. All of these GPs agreed to participate. Written informed consent was obtained from those who agreed to participate, and a demographic questionnaire was completed. The PN who provided the consultations had been working at MQ Health General Practice since 2018, and was funded as an employee of the clinic to provide the full range of services provided by the clinic PNs.

Data collection

Following the consultation, patients were emailed a survey to complete. Patients who completed the consultation and survey were invited to participate in a FG. HCWs were interviewed following completion of the consultations. Patients and HCWs who participated received a A$50 e-shopping voucher (communicated in recruitment material).

The patient survey (see Supplementary material file S1) was in English, and collected demographics, reason for seeking a consultation, satisfaction with various aspects of the consultation (assessed by a Likert scale), willingness to pay for a consultation, and likelihood of using such a service in future and recommending it to others.

The FG was conducted online, and audio recorded via Zoom software. The participants were in Sydney, Australia, and the facilitator was based in China (PO returned to China during course of study). It was conducted in Mandarin. A script had been developed by the researchers for the FG that was translated to Mandarin by the PO. The FG explored the participants’ experiences with the consultation, their satisfaction and suggestions for improvement. The recording was transcribed and translated to English by the PO.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted by two of the researchers (SV, JM) with the participating HCWs. The interviews were audio recorded. The interview explored the HCW’s experience with conducting the consultations, satisfaction with the model, suggestions for improvement, and ideas about how to implement and fund this type of model in general practice. The interview recordings were transcribed by a professional transcription service.

Data analysis

Data were stored and analysed using NVIVO software. Analysis was conducted using a general inductive approach, which is a useful method for analysis of evaluation data.14 It involves detailed readings of the raw data, coding into categories, and then interpretation to derive concepts and themes. Coding was conducted on a line by line basis. The HCW interviews were coded by two researchers (SV, JM). A selection of the interviews were coded by both researchers, and a coding framework was developed from discussion of this initial coding and resolution of discrepancies. The coding framework was then used by both researchers to code an equal share of the interviews. The FG was coded, and a framework developed by one researcher (SV). The categories derived from coding were discussed among the researchers (SV, JM, YX, MK) to allow interpretation of the data. Key themes are presented in the results.

The research team (SV, JM, YX, MK) were all primary care clinicians. Three of the team (SV, JM, YX) worked at the clinic where the study was conducted. They were not involved in patient recruitment or data collection from patients. The GP investigators (SV, JM) were not involved in intervention delivery. The PN investigator (YX) delivered the nurse component of the intervention. Two investigators (SV, JM) recruited and interviewed HCWs. They were, therefore, interacting with work colleagues, which potentially raises the risk of bias. No undue pressure was placed on GPs to participate, and interviews were conducted as per ethics requirements to maintain confidentiality. It was impossible to completely eliminate the impact of the pre-existing workplace relationships. There was also some benefit to having researchers who had a deep understanding of the clinic setting in which the study was conducted.

Results

Patient recruitment

The study ran from September 2021 to May 2022. Nineteen students expressed an interest to participate, 12 consented and completed the consultation and survey. Demographic data of the participants is provided in Table 1. Ten participants who had completed the consultation and survey by April 2022 were invited to participate in a FG. Five participants took part in the FG (100 min duration) in April 2022.

Healthcare worker recruitment

Seven GPs and one PN from MQ Health General Practice consented to participate and provided consultations. Their demographics are presented in Table 2.

Patient survey

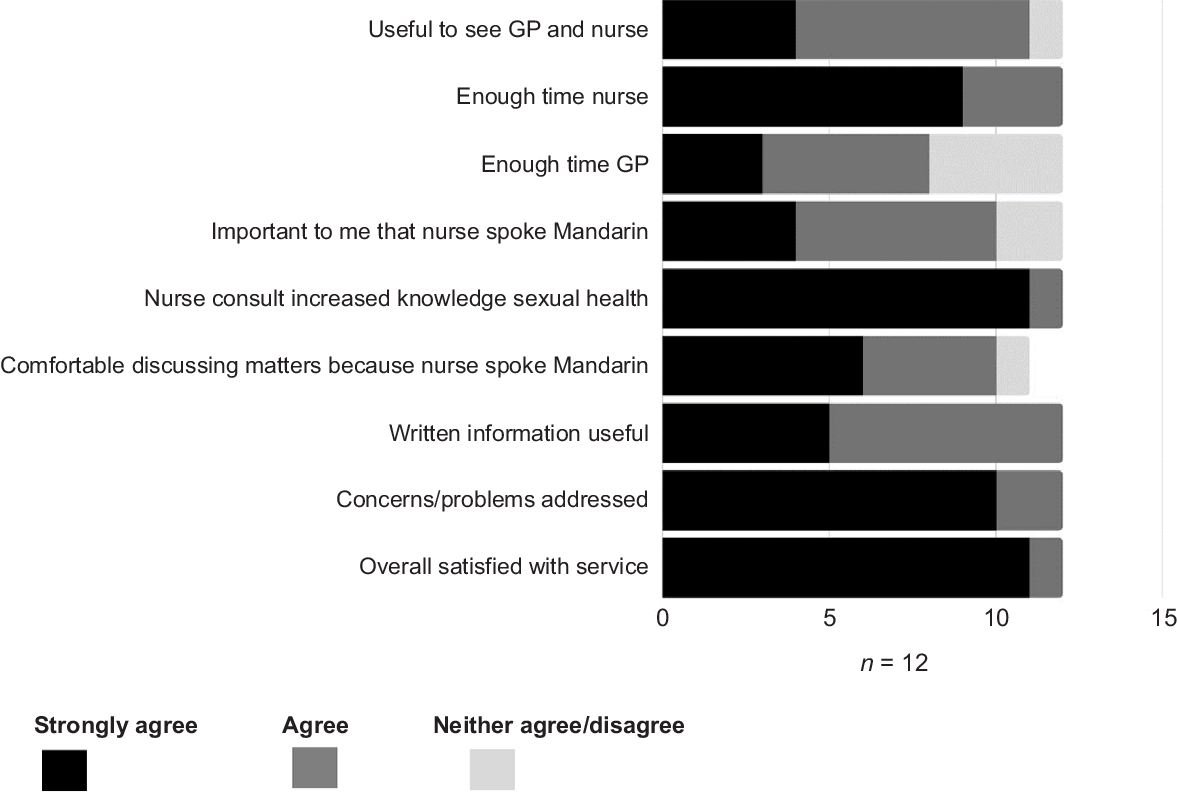

Reasons for participation included 7 out of 12 seeking preventive care advice, 3 out of 12 interested in HPV vaccination, 1 out of 12 with symptoms and 1 out of 12 who wished to contribute to research. There were high levels of satisfaction with the model, in particular, the PN component. The results are presented in Fig. 2. In response to whether they would use the service again, the majority (8/12) said ‘yes’, and overwhelmingly, they would recommend the service to a friend (11/12). There were mixed responses to whether they would be willing to pay for the nurse component of the consultation, with a small number saying ‘yes’ (5/12), and the rest either unsure (4/12) or unwilling to pay (3/12).

Patient focus group findings

The key themes that emerged from the FG are summarised in Table 3.

| Themes | ||

|---|---|---|

| Patient focus group | Healthcare worker interviews | |

| 1. Language and culture are intertwined in delivery of care | 1. Sexual health knowledge enhanced for Mandarin-speaking students | |

| 2. Sexual health knowledge varied | 2. Workflow efficiencies and organisation | |

| 3. Team-based service delivery works for patients | 3. Team-based care allows practitioners to work to their strengths | |

| 4. Willingness to pay uncertain | 4. Financial models uncertain | |

Language and culture are intertwined in delivery of care

Patients clearly found being able to speak in their native language helpful in understanding issues related to sexual health, and also in feeling more at ease to ask questions and clarify medical terminology that could be harder for them in English. It, thus, allowed them to prepare for the time with the GP. Depending on the issue and their level of competence in English, they could use both Mandarin and English fluidly in the consultation with the nurse.

... my English is good, but talking in Mandarin is like an insurance for me, as it’s a pretty complicated topic. (FG 05)

In contrast, one patient did not find communicating in Mandarin necessarily helpful, as they felt discussing sexual health issues in a non-native language was preferable.

I had opposite experience, as when I’m using non-mother language, I feel less embarrassed and have less emotional barriers to talk about those problems. (FG 04)

It was not always the fact that the PN spoke Mandarin, which was the primary value in the service. The common cultural background was also a reason why they appreciated the PN. Patients felt comfortable knowing their belief system was understood.

She also understands our culture and our concerns. (FG 03)

Sexual health knowledge varied

Patients had varying levels of knowledge when it came to sexual health, and their perception of their level of knowledge was not always accurate.

But sometimes, you think you know those things, but actually, you don’t. (FG 03)

It was highlighted that sexual health education was often lacking in their home country, and this potentially had negative consequences.

But recently my friend accidently got pregnant, and needed abortion, and then we realised we know nothing. (FG 05)

The consultation with the PN provided a valuable source of information about topics such as sexually transmitted infections and contraception, rather than relying on friends, the Internet or male partners. One participant mentioned that because the male partner was often more dominant in the relationship, they could influence, for example, choice of contraceptive.

The consultation was perceived as a professional source of information. They also indicated that there was a need for this type of preventive care education for male partners who may not always have knowledge in this area.

And then the first people they want to talk to might be their boyfriends. So what do they (males) know (smile)? So most of my male students who had lot of girlfriends or experiences, they also go to the Internet. (FG 04)

Team-based service delivery works for patients

The patients found their needs were met by the PN consultation, and it provided an opportunity to ask questions with less time pressure compared with GP consultations. They found value in seeing the nurse and the GP. In general, they felt seeing the PN first was the more useful way to structure the consultation.

Sometimes with GP, there’s not enough time to solve all my questions or I missed some problems, or sometimes even I was prepared before seeing the GP, there will still be new questions or the parts that I missed. But I can get all the answers I want from (PN). (FG 03)

The patients identified the utility for doctors of having a team-based approach to care.

... just thinking for doctors, this is an effective method, like an assistant solving some basic problem and pass on the difficult problem to the doctor. (FG 05)

There was a high level of satisfaction with the consultation, particularly the component provided by the nurse, whereas it was more variable for the GP consultation. Sometimes they felt all their needs were met by the PN and there was possibly no need to see the GP.

I give 100/100 to the consultation with (PN), I have no problem with that. (FG 04)

Willingness to pay uncertain

Patients expressed a mix of thoughts about whether they would be prepared to pay for the PN consultation. Some were willing to pay some additional fee, ranging from A$10 to A$20 for the nurse component, whereas others were not so sure. The nature of their problem and what they were seeking appeared to influence whether they would be willing to pay for the nurse.

... if it’s necessary, then I will definitely pay. But if my problem is not that complicated, then I might just go to the GP directly. (FG 01)

They also alluded to the fact that attaching a cost to the service could influence how the service was perceived, and the value of the time associated with it.

If it’s not a paid service, people might be aware of that, they will save the time, as they think it’s a volunteering work, you (PN) really wants me well, I shouldn’t take too much of your time. (FG 04)

Healthcare worker interviews

The HCW interviews lasted from 15 to 28 min (mean 22 min). The key themes elicited from the HCW interviews are summarised in Table 3.

Sexual health knowledge enhanced for Mandarin-speaking students

The GPs found that the nurse consultation provided useful preventive care information for the students, and filled knowledge gaps about sexual and reproductive healthcare.

I think she used the word amazing, and she found it so helpful, and she really appreciated that time that she had with the nurse. (GP 03)

This then meant they could engage the patients in discussions, knowing they had a good understanding of concepts. It allowed for time to answer more complex questions, address opportunistic issues and, in some instances, identified issues that the patient may have been reluctant to raise with the GP directly.

when they have a good understanding ... of preventative activities already, patients ask sort of more detailed questions straight off the bat, (GP 02)

I think she’s often got to what’s really worrying the patient more than what I might have. (GP 05)

Both the GPs and PN felt the consultation in Mandarin was useful, as patients may not be familiar with English terminology, and had time to ask questions with someone they felt comfortable with.

I think the benefit of that is because we’re speaking the same language. I can use more subtle way – more appropriate words. (PN 01)

One of the male GPs who spoke Mandarin still found it useful to have the PN consult, as discussions around sexual health were sensitive, and the gender difference could make it harder for him. It was also mentioned that it was often the cultural alignment, more than language, that helped the communication process.

I don’t think language is actually the main barrier for this type of consultation ... culture is the actual barrier. (PN 01)

Workflow efficiencies and organisation

The PN consultation provided the GPs with time efficiency in their appointments, as they did not have to cover preventive care education. The PN consult highlighted the key issues, and allowed for quick prioritisation of the GP consultation.

I was able to collect my thoughts and have an idea of what we need to talk about, what investigations to order, what to prescribe prior to the consultation, which would expediate the process. (GP 01)

The benefit is we’re actually saving the doctor’s time and the doctor doesn’t have to do the whole consult with the patient. (PN 01)

Generally, the order of seeing the PN followed by the GP was felt to be best; however, there were instances where further involvement of the PN after the GP consult or at a follow-up appointment was identified as being useful. The timing of the PN consultation was generally felt to be adequate at ~30 min, followed by a standard 15-min GP appointment.

Team-based care allows practitioners to work to their strengths

The GPs became more aware of the skills of the PN as a consequence of taking part in this study. Their understanding of her qualifications enabled them to have trust in the work she did with patients. The PN also felt that the GPs needed to have trust in her if this model was to be effective.

Because if the trust is not there, then I don’t know if the model would work as well. (PN 01)

The team-based approach allowed the PN to utilise her advanced skills in this area, and the GPs were able to concentrate on their tasks.

I was not the lead person, the lead person is actually the nurse. I was more part of the team, really. (GP 01)

Generally, the HCWs appeared comfortable about what they saw as their role: the nurse providing education and exploring patient concerns; the GP assessing symptoms, managing more challenging presentations, answering questions that were outside the scope of the PN, and providing referrals for investigations and prescriptions. Some GPs were very comfortable delegating tasks to the PN, whereas one GP seemed more reticent.

This is just my personal practice style, I always double check what my colleague would be doing if we were working as a team for the patient, but maybe I’m duplicating my work, but that’s just the way I practice. (GP 07)

The GPs were satisfied with the communication between themselves and the PN, finding it was the verbal rather than written communication that was most important.

Financial models uncertain

The HCWs were not certain about how best to operate this model in the current financial structure of general practice. Some felt patients would be prepared to pay some money for the nurse consultation, but it would not be a lot.

I guess what I felt the patients got out of it was really quite worthwhile, and I think they would be willing to pay. It would just be working out how to price that in a reasonable sense, and how it’s marketed. (GP 04)

I think that the nurse’s consult can be charged. So I think A$30 for half an hour sounds like a reasonable amount to charge. (PN 01)

The difficulty of providing team-based care in a largely fee for service structure was seen as an impediment to allowing HCWs to work to the top of their scope of practice, in this case allowing a PN to provide advanced sexual health services.

It’s good to use our nurses more and more, and they’ve got great skills. The problem is, they’re not paid, isn’t it. (GP 05)

For international students, the prospect of insurance companies funding this was raised, as well as dedicated funding by universities. Another possible source suggested was local health district funding.

Discussion

This study developed and evaluated a model of care to improve sexual and reproductive health care for female, Chinese, international students in a university based-general practice. We found a high degree of satisfaction among patients and HCWs with the team-based model of care for sexual health care. The students found the consultation with the nurse provided them with reliable information, an opportunity to ask questions and improved their health knowledge. They could see the value of the PN, and the team approach was acceptable to them. The participating GPs also reported satisfaction with the model of care, both for their patients and for their work practice.

Previous research has highlighted the need for culturally and linguistically responsive care for international students in the provision of sexual health care.4,6,7 This model supported the value of doing this. Patients appreciated being able to discuss their concerns in Mandarin if they needed to, and the GPs felt they were not missing important patient concerns, as the nurse was able to elicit these if language was a barrier. The findings also confirmed the importance of cultural alignment – the nurse understood the cultural norms of the patients, particularly in relation to sexual health. Parker et al.7 found international students perceived GP services as medical and not holistic. Introducing the preventive care component with the culturally aligned PN may address this, and is a step towards providing culturally safe care for this patient population.

The literature shows international students face challenges accessing health care, and may experience poorer health outcomes, such as unplanned pregnancies.2–7 This negatively impacts their ability to complete their studies, as well as adding to the burden on the healthcare system. Investment in their wellbeing by provision of appropriate healthcare, including sexual and reproductive health care, stands to benefit both the students and the Australian community.

For the GPs, a team-based model where patient education and health promotion was provided by the PN provided time efficiencies in consulting. Patients were already primed following the PN consult, and the GPs felt more confident about the health knowledge of the patients. They were able to deal with the aspects that required more clinical oversight and practicalities, such as prescribing and referral. Team-based care, with clear task delineation, has the potential to improve workflow and capacity to see patients, and there is longstanding advocacy for its adoption in general practice.15

The literature has highlighted that trust among team members and effective communication are essential for good team-based care.16 The HCWs in this study also highlighted these issues when discussing their experiences of working within this study model. They had confidence in the PN due to greater understanding of her skill set, and this allowed them to work as a team. For practices to deliver successful team-based care, there needs to be some groundwork in developing this trust and understanding between HCWs.16 The fact that the PN and the GPs in this study had already been working together for a few years likely assisted the delivery of this consultation model.

In the current climate of primary care reform in Australia, there is an emphasis on shifting to multidisciplinary care and allowing HCWs to work to the top of their scope of practice.10,17 The challenge is providing a team-based model of care within the current Australian funding model. At present, there are limited services delivered by a PN that receive Medicare (Australian system of government-funded health insurance) or private health insurer funding (utilised by international students). These relate predominantly to chronic disease management. The study found some patients may be willing to pay for the PN component of care in this model. Alternative sources of funding, via health districts or private health insurers, are possibilities, but these sources often come with limitations to their scope. The funding constraints, therefore, limit widespread adoption of team-based models of care for sexual health in mainstream general practice.

The flow-on effect is the inability of practices to utilise the advanced skills of PNs, and allow them to work to the top of their scope of practice in areas such as sexual health care.18 The most recent Commonwealth budget introduced an injection of funding for multidisciplinary care, but it is still unclear as to whether this will have any significant impact on the capacity of general practices to implement team-based care.19

This study was limited by its small patient cohort due to its timing during the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as its implementation with a particular subset of patients in a university-based clinic. There is a need to test this type of model with a larger patient sample, including men; however, the findings from this small study are promising. The needs of the female, Mandarin-speaking, international student population are equally relevant to other international students, and patients from culturally and linguistically diverse populations. The findings, therefore, are relevant to mainstream general practice in an increasingly multicultural Australian population.

The study collected data from multiple sources: patient survey, FG and HCW interviews. There was concordance between the patient survey and FG findings, and the HCW interviews also demonstrated that the GPs felt the patients were provided with a valuable clinical service. This triangulation of findings was a strength of the study.

Conclusion

This study has shown that GPs and PNs have the potential to deliver effective team-based care for sexual health services. Furthermore, it implemented a model that addressed the needs of a particular patient cohort who have increased needs in this area, Mandarin-speaking international students. Mainstream general practice has the ability to provide this care, what is required is structural funding changes to enable this to be embedded in practice.

Data availability

The data that support this study are available in the article. Further data will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by a RACGP Foundation/BOQ Specialist Research Grant 2020 (BOQ2020-04).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the GPs and patients who participated in this study, in particular, their willingness to be involved during the COVID-19 pandemic period. We also acknowledge Shanna O’Connor, Faculty of Medicine, Health and Human Sciences, Macquarie University, who provided administrative assistance.

References

1 Australian Government, Department of Education. International student numbers by country, by state and territory. 2023. Available at https://www.education.gov.au/international-education-data-and-research/international-student-numbers-country-state-and-territory [accessed 26 January 2024]

2 Lim MSY, Hocking JS, Sanci L, Temple-Smith M. A systematic review of international students’ sexual health knowledge, behaviours, and attitudes. Sex Health 2023; 19(1): 1-16.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

3 Engstrom T, Waller M, Mullens AB, Durham J, Debattista J, Wenham K, et al. STI and HIV knowledge and testing: a comparison of domestic Australian-born, domestic overseas-born and international university students in Australia. Sex Health 2021; 18: 346-348.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

4 Burchard A, Laurence C, Stocks N. Female international students and sexual health: a qualitative study into knowledge, beliefs and attitudes. Aust Fam Physician 2011; 40(10): 817-820.

| Google Scholar |

5 Poljski C, Quiazon R, Tran C. Ensuring rights: improving access to sexual and reproductive health services for female international students in Australia. J Int Stud 2014; 4(2): 150-163.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

7 Parker A, Harris P, Haire B. International students’ views on sexual health: a qualitative study at an Australian university. Sex Health 2020; 17: 231-238.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

8 Mundie A, Lazarou M, Mullens AB, Gu Z, Dean JA. Sexual and reproductive health knowledge, attitudes and behaviours of Chinese international students studying abroad (in Australia, the UK and the US): a scoping review. Sex Health 2021; 18: 294-302.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

9 Kularadhan V, Fairley CK, Chen M, Bilardi J, Fortune R, Chow EPF, et al. Optimising the delivery of sexual health services in Australia: a qualitative study. Sex Health 2022; 19(4): 376-385.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

10 Australian Government. Strengthening Medicare taskforce report. Australian Government; 2022. Available at https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-02/strengthening-medicare-taskforce-report_0.pdf [accessed 26 January 2024]

11 Morgan DL. Paradigms lost and pragmatism regained: methodological implications of combining qualitative and quantitative methods. J Mix Methods Res 2007; 1(1): 48-76.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

12 Kaushik V, Walsh CA. Pragmatism as a research paradigm and its implications for social work research. Soc Sci 2019; 8: 255.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

13 Mahadeva J, Vagholkar S, Xiang E, Kang M. Healthcare provider views on the provision of sexual and reproductive healthcare for international students. In ‘AAAPC Annual Conference 12-13 August 2021’. Aust J Prim Health 2021; 27(4): iii-lviii. doi:10.1071/PYv27n4abs. pubmed id:34353433

14 Thomas DR. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am J Eval 2006; 27(2): 237-246.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

15 Naccarella L, Greenstock LN, Brooks PM. A framework to support team-based models of primary care within the Australian health care system. Med J Aust 2013; 199(5): S22-S25.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

16 Babiker A, Husseini ME, Al Nemn A, Al Frayh A, Al Juryyan N, Faki MO, et al. Health care professional development: working as a team to improve patient care. Sudan J Paediatr 2014; 14(2): 9-16.

| Google Scholar |

17 Department of Health & Aged Care. Unleashing the potential of our health workforce. scope of practice review. Issues Paper 1. 2024. Available at https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/2024-01/unleashing-the-potential-of-our-health-workforce-scope-of-practice-review-issues-paper-1.pdf [accessed 26 January 2024]

18 Abbot P, Dadich A, Hosseinzadeh H, Kang M, Hu W, Bourne C, et al. Practice nurses and sexual health care: enhancing team care within general practice. Aust Fam Physician 2013; 42(10): 729-732.

| Google Scholar |

19 RACGP. Overview of the federal budget 2023–24 (health). 2023. Available at https://www.racgp.org.au/FSDEDEV/media/documents/RACGP-2023-24-Budget-Overview-Health.pdf [accessed 26 January 2024]